Abstract

Methamphetamine abuse and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection induce neuropathological changes in corticolimbic brain areas involved in reward and cognitive function. Little is known about the combined effects of methamphetamine and HIV infection on cognitive and reward processes. The HIV/gp120 protein induces neurodegeneration in mice, similar to HIV-induced pathology in humans. We investigated the effects of gp120 expression on associative learning, preference for methamphetamine and non-drug reinforcers, and sensitivity to the conditioned rewarding properties of methamphetamine in transgenic (tg) mice expressing HIV/gp120 protein (gp120-tg). gp120-tg mice learned the operant response for food at the same rate as non-tg mice. In the two-bottle choice procedure with restricted access to drugs, gp120-tg mice exhibited greater preference for methamphetamine and saccharin than non-tg mice, whereas preference for quinine was similar between genotypes. Under conditions of unrestricted access to methamphetamine, the mice exhibited a decreased preference for increasing methamphetamine concentrations. However, male gp120-tg mice showed a decreased preference for methamphetamine at lower concentrations than non-tg male mice. gp120-tg mice developed methamphetamine-induced conditioned place preference at lower methamphetamine doses compared with non-tg mice. No differences in methamphetamine pharmacokinetics were found between genotypes. These results indicate that gp120-tg mice exhibit no deficits in associative learning or reward/motivational function for a natural reinforcer. Interestingly, gp120 expression resulted in increased preference for methamphetamine and a highly palatable non-drug reinforcer (saccharin) and increased sensitivity to methamphetamine-induced conditioned reward. These data suggest that HIV-positive individuals may have increased sensitivity to methamphetamine, leading to high methamphetamine abuse potential in this population.

Keywords: Conditioned place preference, food-maintained responding, oral self-administration, pharmacokinetics, quinine, saccharin

INTRODUCTION

Methamphetamine use and dependence are common among people infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; Marquez et al., 2009). Methamphetamine use in HIV-infected individuals is notably problematic because it compromises treatment strategies (Ellis et al., 2003), increases cognitive abnormalities (Carey et al., 2006; Chana et al., 2006; Rippeth et al., 2004), and quickens disease progression (Carrico, 2011). High levels of continued methamphetamine abuse in HIV-infected humans may be attributable to the increased risk of contracting HIV in methamphetamine users (Shoptaw and Reback, 2006) or as a form of self-medication for HIV-related symptoms or antiretroviral treatments (Robinson and Rempel, 2006; Semple et al., 2002). Importantly, some patient populations show high levels of methamphetamine uptake after HIV infection (Robinson and Rempel, 2006), indicating the potential vulnerability of HIV-infected humans to develop methamphetamine dependence. However, the neurobiological mechanisms that underlie the enhanced susceptibility to drug dependence in HIV-infected humans are not well understood (Nath, 2010).

Corticolimbic reward circuits in the brain, particularly the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, are crucial for the initiation and maintenance of drug use (Berridge, 2007; Di Chiara, 2002; Nestler, 2005). Methamphetamine increases synaptic dopamine levels in mesolimbic brain regions by compromising dopamine transporter function (Sulzer et al., 2005). Even small methamphetamine “binges” can lead to long-lasting synaptic depression at corticostriatal terminals, which may contribute to the development of addiction (Bamford et al., 2008). HIV infection has been shown to preferentially target the basal ganglia, leading to decreased caudate/basal ganglia volume (Aylward et al., 1993; Kieburtz et al., 1996) and decreased dopamine levels (Kumar et al., 2009). Moreover, decreases in basal ganglia gray matter are apparent early in HIV disease progression (Neuen-Jacob et al., 1993). Caudate atrophy and volume decreases are associated with poor cognitive performance (Hestad et al., 1993; Kieburtz et al., 1996). HIV-infected patients with dementia also show decreased dopamine transporter expression in the caudate putamen compared with HIV-infected non-demented patients (Berger and Nath, 1997). Thus, the effects of HIV and methamphetamine on the dopamine system in the basal ganglia show significant overlap (Theodore et al., 2007), suggesting that basal ganglia dysfunction may be a common neural substrate for methamphetamine abuse and HIV.

HIV-induced neuropathology involves the indirect effects of HIV viral products, particularly the envelope glycoprotein gp120. The gp120 protein contributes to the dysfunction of the dopamine system associated with HIV infection (Agrawal et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2009; Purohit et al., 2011). In vitro, dopamine neurons are preferentially sensitive to gp120-induced apoptosis (Agrawal et al., 2010), and gp120 decreases dopamine transporter function and cell viability in cultured human dopamine neurons (Hu et al., 2009). Interestingly, the exposure of human neuronal cultures to gp120 and methamphetamine results in synergistic neuronal toxicity measured by neuronal cell death and mitochondrial membrane potential (Turchan et al., 2001). Although numerous interactions between methamphetamine and gp120/HIV infection, such as exacerbated frontostriatal neuronal damage, dopamine depletion, and oxidative stress, have been described (Silverstein et al., 2011), understanding the behavioral consequences of HIV and methamphetamine exposure in human patients is extremely difficult because of complicated symptom overlap (Nath, 2010). Thus, the development of animal models that express HIV-related proteins is essential to determine the role of methamphetamine in HIV-related neuropathology. For example, using a HIV-1 transgenic rat model that expresses multiple HIV viral proteins, Chang and colleagues have shown that HIV-related proteins can lead to an increased behavioral sensitivity to methamphetamine (Kass et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2009). However, animal models that express individual HIV-related proteins, such as gp120, allow for the controlled investigation of the role of HIV gp120 protein in brain reward function in response to methamphetamine exposure.

Transgenic (tg) mice that produce gp120 in the brain (gp120-tg) at levels similar to those found in HIV patients (Toneatto et al., 1999) show a broad range of behavioral, neuronal, and glial changes that resemble those found in the brains of HIV-infected individuals. For example, gp120-tg mice show widespread reactive astrocytosis (Toggas et al., 1994), an important part of the brain’s response to diverse injury (Eddleston and Mucke, 1993) and an important glial marker found in postmortem HIV-infected brains (Navia et al., 1986; Weis et al., 1993). Moreover, gp120 expression in mice results in the loss of large pyramidal neurons (Toggas et al., 1994), consistent with pyramidal neuron deficits found in HIV-infected humans (Achim et al., 2009; Masliah et al., 1992; Masliah et al., 1997). Deficits in hippocampal short- and long-term potentiation in gp120-tg mice may reflect the functional consequences of neuronal dysfunction (Krucker et al., 1998) and lead to certain behavioral deficits, such as impaired spatial memory retention observed in gp120-tg mice (D’Hooge et al., 1999). Neuronal abnormalities similar to those found in gp120-tg mice may also be involved in memory deficits observed in HIV-infected humans (Hinkin et al., 2002; Moore et al., 2011). Although gp120-tg mice show subtle alterations in methamphetamine-induced stereotyped behavior (Roberts et al., 2010), little is known about the behavioral consequences of gp120 expression on methamphetamine-induced behavior and specifically methamphetamine reward.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the rewarding properties of methamphetamine in mice that express the gp120 protein in the brain. Reward and motivation for a natural reinforcer were evaluated by assessing food-maintained responding using two different schedules of reinforcement. The fixed-ratio (FR) schedule of reinforcement with increasing difficulty (i.e., FR1, FR2, and FR5) assessed the reinforcing properties of food reward and allowed the assessment of the associative learning ability of the mice during operant task acquisition. Reinforcement efficacy and the motivation to respond for the food reward was assessed with a progressive-ratio (PR) schedule of reinforcement (O’Brien and Gardner, 2005). The two-bottle choice procedure with restricted and unrestricted access to drinking solutions was used to assess the primary reinforcing properties of methamphetamine. In addition, a highly palatable sweet saccharin solution and bitter-tasting quinine solution, with a taste similar to methamphetamine (Scibelli et al., 2011), were used to determine whether gp120-tg and non-tg mice exhibit differences in taste preference that influence the interpretation of genotype differences in the preference for the methamphetamine solution. The conditioned rewarding properties of methamphetamine were evaluated using the conditioned place preference (CPP) procedure. The CPP test measures “drug seeking” or the incentive motivation to receive a methamphetamine reward (Gardner, 2005; Tzschentke, 2007). Finally, to ensure that gp120 expression had no general effects on pharmacokinetics, methamphetamine and amphetamine levels were measured in plasma samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

The present study used male and female transgenic mice (gp120–tg) on a C57BL/6 × DBA genetic background that expressed the gp120 protein under the regulatory control of a modified murine glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP). The mice were generated as previously described (Toggas et al., 1994) and provided by the Neuroscience and Animal Models Core of the Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC; University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA). The mice were group-housed with 2–4 mice per cage or single-housed (e.g., for the two-bottle choice drinking procedure and food self-administration) in a humidity-and temperature-controlled animal facility on a 12 h/12 h reverse light/dark cycle (lights off at 7:00 AM) with ad libitum access to food and water unless otherwise specified in particular experiments (e.g., food-maintained responding). Behavioral testing was conducted during the dark phase of the light/dark cycle. Both male and female mice were tested. All of the experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and National Research Council’s Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of California San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Behavioral testing began when the mice were 3–4 months old. The first cohort of mice was tested for food-maintained responding under FR and PR schedules of reinforcement. Subsequently, this mouse cohort was tested in the methamphetamine-induced CPP procedure. All of the other mouse cohorts were initially tested for methamphetamine-induced CPP. After a minimum washout period of 1 week, the mice were separated into different experimental groups and subsequently tested for tastant (saccharine, quinine) preference, restricted methamphetamine preference, unrestricted methamphetamine preference, and methamphetamine pharmacokinetics.

Food self-administration

Single-housed naive mice were food-deprived and received 3 g of food chow daily with unlimited access to water. The self-administration of food (25 mg pellets; TestDiet, Richmond, IN, USA) was assessed in 12 operant conditioning chambers (Model ENV-307A; Med Associates, St. Albans, VT, USA), each housed in a sound-attenuated enclosure. The chambers (15.9× 14.0× 12.7 cm) featured two retractable levers separated by a food hopper along one wall and a metal rod grating floor. The mice were trained to press a lever to receive a food pellet under an FR schedule of reinforcement. East test session was terminated after 30 min elapsed or when 30 rewards were earned, whichever occurred first. Three FR schedules were used with increasing difficulty and timeout (TO) intervals (FR1 TO 1 s, FR2 TO 10 s, and FR5 TO 20 s). Responses on the active lever resulted in the presentation of a conditioned stimulus light and food pellet delivery. Responses on the inactive lever had no programmed sequences. The criteria for the progression to the next schedule included receiving > 27 rewards in three consecutive sessions. After the completion of training under the FR schedules of reinforcement, the mice were trained to respond for food under the PR schedule of reinforcement. Training consisted of one daily 3 h session or until the mouse did not receive a reward for 30 min. The lever presses required to earn a food reward escalated within a session according to the following series (Roberts and Bennett, 1993): 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 12, 15, 20, 32, 40, 50, 62, 77, 95, 118, 145, 219, 268, 328, 402, 492, 603, 737, etc. In the PR schedule, the number of responses to earn one food pellet is progressively increased, and the last completed ratio value is a measure of motivation, referred to as the breakpoint. The groups comprised 14 male and 13 female non-tg mice and 12 male and 17 female gp120-tg mice.

Conditioned place preference

To assess the conditioned rewarding properties of methamphetamine, the mice were tested in a CPP paradigm using a between-subjects experimental design. Testing was performed in three CPP chambers (San Diego Instruments, San Diego, CA, USA). Each chamber consisted of three compartments: two side compartments (left and right; 26.4 × 20.6 × 33.3 cm) and a center compartment (15.9 × 20.6 × 33.3 cm). The three compartments were differentiated by texture, illumination level, and flooring. The left compartment featured black and white striped walls, textured flooring, and 12 lux illumination. The right compartment had gray walls, smooth flooring, and 2 lux illumination. The center compartment had white walls, metal rod grid flooring, and 4 lux illumination. Testing consisted of three phases: pretest, conditioning, and test. In the pretest phase, the mice were allowed to explore all three compartments for 15 min. The time spent in each compartment was recorded. In the conditioning phase, one side compartment was assigned to methamphetamine, and the other compartment was assigned to saline. The conditioning sessions (i.e., a total of eight sessions over the course of 8 days) consisted of alternating intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections of saline and methamphetamine (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 mg/kg; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) with the mouse placed in either the left or right compartment for 40 min immediately after the injection. These sessions resulted in a total of four injections of saline in one compartment and four injections of methamphetamine in the other compartment. The place preference test occurred 24 h after the last methamphetamine or saline injection in a drug-free state. During the place preference test, the mice were allowed to explore all three compartments for 15 min. The time spent in each compartment was recorded. The CPP score was calculated as the time spent in the methamphetamine-paired compartment minus the time spent in the saline-paired compartment. The groups comprised 9–12 mice per genotype, sex, and dose. All of the 239 mice tested were naive, with the exception of 56 mice that were previously tested in the food self-administration procedure.

Two-bottle choice procedure with restricted access to drinking solutions

Methamphetamine consumption and preference with restricted access

Methamphetamine preference was assessed using a two-bottle choice paradigm with restricted access to methamphetamine solutions. The mice were individually housed in cages with two 150 ml drinking bottles and food. Both bottles were filled with tap water for 2 days to familiarize the mice to the new bottles. Subsequently, the mice were given the choice between water and a water-methamphetamine solution of increasing concentrations (10 mg/L methamphetamine on days 1–4, 20 mg/L methamphetamine on days 5–8, and 40 mg/L methamphetamine on days 9–12) for 18 h per day. The position of the methamphetamine-containing bottle was alternated every 2 days to prevent location biases. The volume consumed was measured each day, and the preference ratio (methamphetamine bottle [ml]/total from both bottles [ml]) and dose consumed (mg/kg/18 h) were calculated. The methamphetamine dose consumed on the second and fourth days was averaged to determine consumption under conditions that allowed the mice to learn the new location of the methamphetamine bottle. The body weight of the mice and consumption from each bottle were measured daily throughout the experiment. The groups comprised 12 male and 15 female non-tg mice and 11 male and 10 female gp120-tg mice. All of the mice used in this experiment were previously tested in the CPP procedure.

Tastant consumption and preference

A separate group of mice was assessed for tastant preference. The tastants were saccharin (sweet; 0.033% followed by 0.066%; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and quinine (bitter; 0.015 mM followed by 0.03 mM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Each tastant was available for a total of 8 days or 4 days per concentration. The mice were given access to the tastants for 24 h per day. During testing, all of the methodological parameters were identical to those used for methamphetamine consumption and preference. The groups comprised 11 male and 10 female non-tg mice and 10 male and 11 female gp120-tg mice. All of the mice used in this experiment were previously tested in the CPP procedure.

Two-bottle choice procedure with unrestricted access to methamphetamine solution (oral methamphetamine self-administration)

Single-housed mice were given access to two drinking bottles (150 ml) and food. Both bottles were filled with water to acclimate the mice to drinking from two bottles. Water consumption from both bottles was assessed for 6 days. One of the bottles was then filled with a methamphetamine solution, and the methamphetamine concentrations were increased every 10 days. Three concentrations of methamphetamine were tested consecutively (5, 10, and 20 mg/L). The mice were given access to methamphetamine/water bottles for 24 h per day. The position of the water- and methamphetamine-containing bottles remained the same for the 10-day period of exposure to each methamphetamine concentration and was alternated between concentrations. The body weight of the mice and consumption from each bottle were measured daily throughout the experiment. Both the total amount of methamphetamine consumed (mg/kg/day) and preference for the methamphetamine solution vs. water were assessed. The groups comprised 10 male and 6 female non-tg mice and 10 male and 5 female gp120-tg mice. All of the mice used in this experiment were previously tested in the CPP procedure.

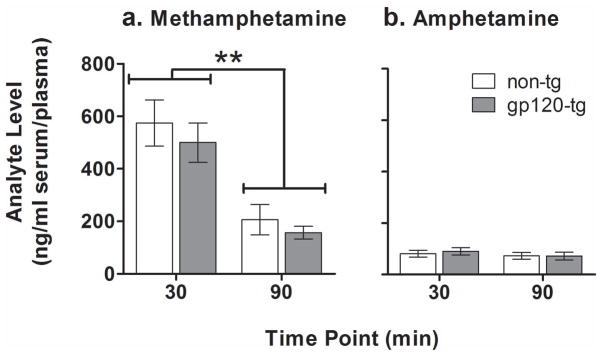

Methamphetamine pharmacokinetics

The levels of methamphetamine and its active metabolite amphetamine in plasma were measured in mice 30 and 90 min after an acute i.p injection of 4 mg/kg methamphetamine. The mice were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Sleepaway; Fort Dodge, NY, USA), and blood samples were collected by cardiac puncture. The blood samples were centrifuged at 13,000 rotations per minute for 15 min, and the plasma samples were analyzed for methamphetamine and amphetamine using high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (NMS Labs, Willow Grove, PA, USA). The groups comprised 2–3 mice per sex per genotype per time point. All of the mice used in this experiment were previously tested in the CPP procedure.

Statistical analyses

All of the analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics v.19 (Chicago, IL, USA). Methamphetamine/tastant preference/consumption and methamphetamine self-administration data were analyzed using a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with Sex and Genotype as the between-subjects factors and Concentration as the repeated measure. Food responding under the FR schedule of reinforcement was analyzed using mixed-design ANOVAs, with Sex and Genotype as the between-subjects factors and FR schedule as the repeated measure (three levels: FR1, FR2, and FR5). Data from the PR schedule of reinforcement were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, with Sex and Genotype as the between-subjects factors. The CPP data were analyzed using a three-way ANOVA, with Dose, Sex, and Genotype as the between-subject factors. Methamphetamine and amphetamine pharmacokinetics data were analyzed using a three-way ANOVA, with Time point, Sex, and Genotype as the between-subjects factors. When appropriate, post hoc comparisons were performed using Least Significant Difference (LSD) analyses. All of the results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Body weight

No obvious physical differences were observed between non-tg and gp120-tg mice. However, the body weights of gp120-tg mice were significantly less than the body weights of non-tg mice, with a significant main effect of Genotype (F1,153 = 24.3, p < 0.001) and a significant Sex× Genotype interaction (F1,153 = 7.7, p < 0.01) detected in the ANOVA. Male gp120-tg mice weighed less (~13%) than non-tg males (p < 0.001; data not shown). Similarly, female gp120-tg mice weighed less (~5%) than female non-tg mice, but this effect did not reach significance.

Food self-administration

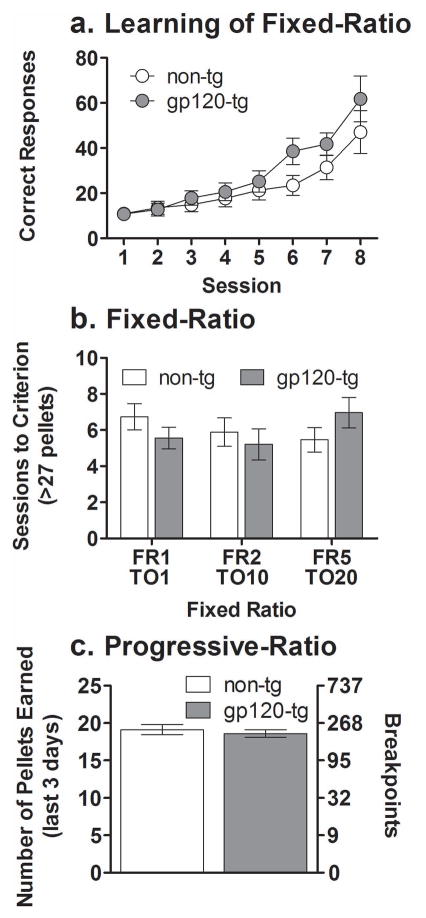

Mice of both genotypes learned to self-administer food under the FR1 TO 1 s schedule of reinforcement, reflected by an increased number of correct responses across the initial eight sessions (Fig. 1a; F7,364 = 34.1, p < 0.001). Furthermore, no significant effects of Genotype were found when the mice were tested under FR schedules with increasing difficulty (Fig. 1b). A significant main effect of Sex (F1,51 = 6.5, p < 0.01) was observed, with females tending to need more sessions to reach the criterion (i.e., > 27 rewards in three consecutive sessions) than male mice (data not shown). However, no interaction was observed between the factors Genotype and Sex. No significant main effects on either the number of pellets earned or breakpoint were found between non-tg and gp120-tg mice when tested under the PR schedule of reinforcement (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Learning curves for responding for food under a fixed-ratio 1 schedule of reinforcement (a). Food-maintained responding under a fixed-ratio schedule of reinforcement (b). Food-maintained responding under a progressive-ratio schedule of reinforcement (c) in non-tg (white circles/bars) and gp120-tg mice (gray circles/bars). The non-tg and gp120-tg mice showed the same rate of learning across sessions under the fixed-ratio 1 schedule of reinforcement. The total number of sessions required to reach criterion (> 27 pellets) was similar in non-tg and gp120-tg mice under all fixed-ratio schedules. The pellets earned over the last 3 days of progressive-ratio schedule testing and breakpoints were similar in non-tg and gp120-tg mice. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. FR, fixed-ratio schedule; TO, time-out interval.

Two-bottle choice preference

Methamphetamine preference and consumption with restricted access

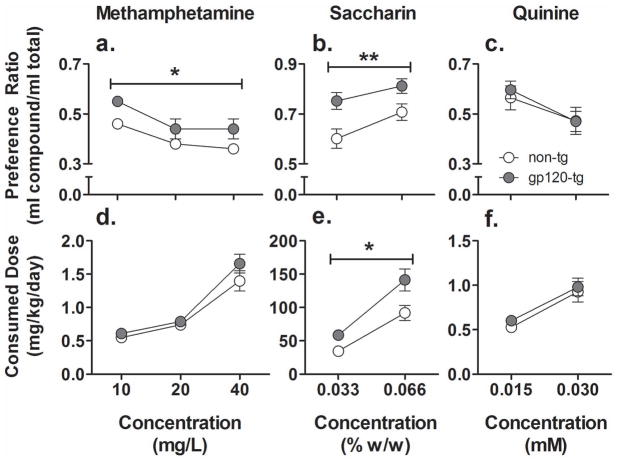

The preference index for methamphetamine decreased in all of the mice (Fig. 2a; F2,88 =11.1, p < 0.001) with increasing concentration. A significant main effect of Genotype on methamphetamine preference (F1,44 = 5.1, p < 0.05) was observed, with gp120-tg mice exhibiting a greater preference for methamphetamine compared with non-tg mice. The methamphetamine dose consumed (mg/kg/day) increased in both non-tg and gp120-tg mice with increasing methamphetamine concentrations (Fig. 2d; F2,88 = 86.4, p < 0.001). However, no effect of Genotype on methamphetamine dose consumed was found.

Figure 2.

Preference (a–c) and consumption (d–f) of methamphetamine (a, d), saccharin (b, e), and quinine (c, f) in non-tg (white circles) and gp120-tg (gray circles) mice. The gp120-tg mice showed greater preference for methamphetamine than non-tg mice. The gp120-tg mice also showed a greater preference for and consumed more saccharin than non-tg mice. No differences were found between genotypes in quinine preference and consumption. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Note: methamphetamine access was 18 h/day, and saccharin and quinine access was for 24 h/day. The y-axis ranges vary to best depict the results. Error bars at several data points are not visible due to small data variability. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significant main effect of Genotype in the ANOVA.

Tastant preference and consumption

Both non-tg and gp120-tg mice showed an increasing preference for saccharin with increasing concentrations (Fig. 2b; F1,38 = 17.6, p < 0.001). In addition, a significant main effect of Genotype (F1,38 = 8.0, p < 0.01) was found on saccharin preference, with gp120-tg mice exhibiting a greater preference for saccharin than non-tg mice. The total amount of saccharin consumed per day (mg/kg/day) also increased with increasing concentrations (Fig. 2e; F1,38 = 114.4, p < 0.001). A significant main effect of Genotype (F1,38 = 7.2, p < 0.01) was found, with gp120-tg mice showing greater saccharin consumption at both concentrations tested compared with non-tg mice. Overall, independent of genotype, female mice consumed significantly more saccharin than males (data not shown; F1,38 = 6.0, p < 0.05). However, no interactions were found between Sex and Concentration or Genotype on the amount of saccharin consumed.

The preference for quinine solution decreased with increasing quinine concentrations (Fig. 2c; F1,38 = 14.5, p < 0.001). Similar to methamphetamine and saccharin, the mice consumed increasing amounts of quinine per day (mg/kg/day) with increasing quinine concentrations (Fig. 2f; F1,38 = 37.1, p < 0.001). No significant differences were found between non-tg and gp120-tg mice either for quinine consumption or preference.

Unrestricted methamphetamine oral self-administration

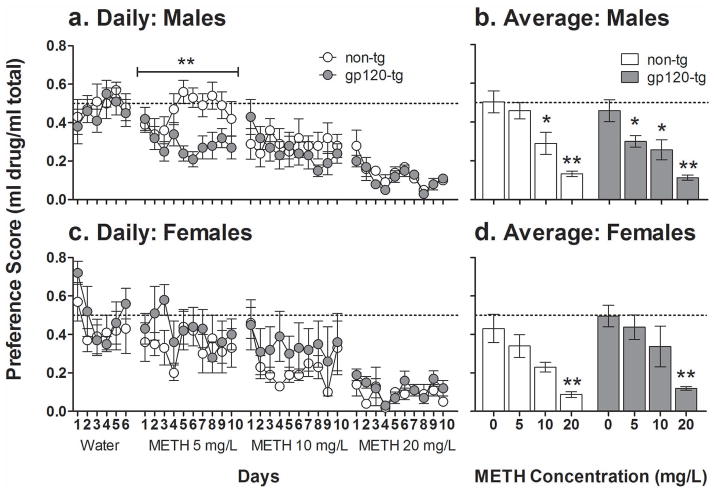

Unrestricted access to increasing methamphetamine concentrations for 10 days per concentration produced a dose-dependent aversion. The preference for methamphetamine significantly decreased with increasing methamphetamine concentrations in all of the mice (Fig. 3; F3,81 = 42.2, p < 0.001). A significant Sex× Genotype interaction (F1,27 = 4.9, p < 0.035) was observed, with male gp120-tg mice being more sensitive to methamphetamine-induced decreases in preference. Specifically, male gp120-tg mice exhibited a significantly decreased preference for methamphetamine at the low concentration of 5 mg/L (Fig. 3b; p < 0.05). No decreases in preference for this dose of methamphetamine were observed in female gp120-tg, female non-tg, or male non-tg mice.

Figure 3.

Methamphetamine (METH) preference (daily [a, c]; average [b, d]) with unrestricted oral access in male (a, b) and female (c, d) non-tg (white) and gp120-tg (gray) mice. All of the mice showed decreasing preference for methamphetamine with increasing doses. Male gp120-tg mice displayed a significantly decreased preference for methamphetamine at the lowest dose of methamphetamine tested (5 mg/L) than male non-tg mice. The data are expressed as meanSEM. The dotted line represents equal preference for drinking from both bottles. a. **p < 0.01, significant difference between non-tg and gp120-tg mice. b, d. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significantly decreased preference compared with water (0 mg/L methamphetamine).

The total methamphetamine dose consumed per day (mg/kg/day) depended on the methamphetamine concentration (F2,54 = 3.91, p < 0.05) and did not differ between non-tg mice (5 mg/L: 0.29 ± 0.03; 10 mg/L: 0.35 ± 0.04; 20 mg/L: 0.31 ± 0.04) and gp120-tg mice (5 mg/L: 0.27 ± 0.03; 10 mg/L: 0.39 ± 0.07; 20 mg/L: 0.31 ± 0.04). All of the mice consumed significantly more methamphetamine when given access to 10 mg/L compared with 5 mg/L (p < 0.05), with no other significant differences between methamphetamine concentrations. No main effects of Sex or Genotype were observed on the methamphetamine dose consumed per day.

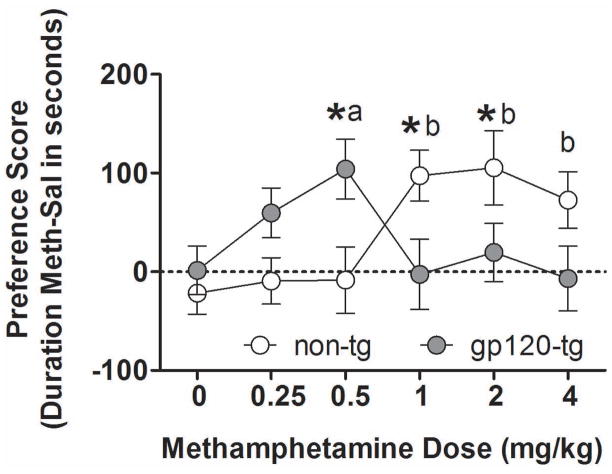

Conditioned place preference

Both non-tg and gp120-tg mice developed dose-dependent methamphetamine-induced CPP (Fig. 4). However, methamphetamine-induced CPP developed at different doses in non-tg and gp120-tg mice, reflected by a significant Dose × Genotype interaction (F5,215 = 4.8, p < 0.001). The non-tg mice exhibited methamphetamine-induced CPP at 1 mg/kg (p < 0.01), 2 mg/kg (p < 0.05), and 4 mg/kg (p < 0.05). In contrast, gp120-tg mice exhibited methamphetamine-induced CPP only at 0.5 mg/kg (p < 0.05). Although no interaction was found between the factors Sex and Genotype, a significant Dose × Sex interaction (F5,239 = 2.8, p < 0.05) was observed, with female mice showing a significantly decreased methamphetamine-induced CPP compared with males at the highest methamphetamine dose (4 mg/kg) used (data not shown; p < 0.01). No differences were observed between genotypes in the time spent in either compartment during the pretest phase.

Figure 4.

Methamphetamine-induced conditioned place preference in non-tg (white circles) and gp120-tg (gray circles) mice. Data from males and females were combined. The conditioned rewarding effects of methamphetamine were observed at lower doses in gp120-tg mice compared with non-tg mice, with a leftward shift of the dose-response curve. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, significant difference between non-tg and gp120-tg mice at a specific methamphetamine dose. ap < 0.05, significant effect of methamphetamine in gp120-tg mice compared with saline-treated gp120-tg mice. bp < 0.05, significant effect of methamphetamine in non-tg mice compared with saline-treated non-tg mice.

Methamphetamine pharmacokinetics

The plasma concentration of methamphetamine was similar in gp120-tg and non-tg mice (Fig. 5a). A significant main effect of Time point (F1,23 = 33.1, p < 0.001) was observed, with methamphetamine levels higher at the 30 min time point compared with the 90 min time point (p < 0.001). A significant main effect of Sex (F1,23 = 5.2, p < 0.05) was also found, with female mice showing a lower level of methamphetamine at 30 min compared with male mice (p < 0.01; data not shown). However, no Sex× Genotype interaction was observed. No significant main effects of Time point, Sex, or Genotype were found on the plasma levels of amphetamine, with no significant interactions among these factors (Fig. 5b).

Figure 5.

Pharmacokinetics of methamphetamine (a) and its metabolite amphetamine (b) after a 4 mg/kg dose of methamphetamine in non-tg (white bars) and gp120-tg (gray bars) mice. Levels of methamphetamine in plasma decreased over time, but no differences were found between non-tg and gp120-tg mice. The data are expressed as mean ± SEM. **p < 0.01, significant difference in methamphetamine plasma concentrations between two time points. The authors would like to thank Mr. Russell Kim for technical assistance and Mr. Michael

DISCUSSION

The present study investigated the central effects of the HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 on cognitive function and reward processes in response to methamphetamine and non-drug reinforcers. Gp120-tg mice showed a similar capacity to learn a FR schedule of reinforcement as non-tg control mice, indicating that basic associative learning was not impaired by gp120 expression. The reinforcing efficacy and motivation to receive a food reward in gp120-tg mice was also similar to non-tg mice, reflected by a similar number of sessions required to reach criterion on the FR and PR schedules. The gp120-tg mice exhibited an increased preference for methamphetamine when given restricted oral access. Unrestricted access to methamphetamine resulted in decreased methamphetamine preference, indicative of aversion, in all of the mice. However, male gp120-tg mice exhibited increased aversion at low methamphetamine concentrations, indicating higher sensitivity to methamphetamine-induced aversion compared with non-tg male mice. Although no difference in the preference for quinine was observed, the preference for the highly palatable sweet-tasting saccharin and amount of saccharin consumed (mg/kg/day) were greatly increased in gp120-tg mice compared with non-tg mice. These findings indicate that gp120-tg mice have increased sensitivity to highly palatable non-drug reinforcers, such as saccharin, but not regular food pellets. The gp120-tg mice were also more sensitive to the conditioned rewarding effects of methamphetamine in the CPP paradigm, indicating greater incentive motivation associated with methamphetamine reward. Similar blood levels of methamphetamine after acute administration confirmed that the higher sensitivity to methamphetamine in gp120-tg compared with non-tg mice was not attributable to alterations in methamphetamine pharmacokinetics. Altogether, these results indicate that gp120 expression in the brain alters the rewarding properties of both methamphetamine and sweet-tasting non-drug rewards.

The most striking finding of the present work was that gp120-tg mice were more sensitive to the conditioned rewarding properties of methamphetamine assessed in the CPP procedure. Methamphetamine-induced CPP was found in both gp120-tg and non-tg mice. Importantly, the dose required for the acquisition of CPP was lower in gp120-tg mice, reflected by a clear shift of the dose-response curve to the left in gp120-tg mice. In previous studies, C57BL/6 strains of mice have exhibited CPP at doses of 1 mg/kg methamphetamine or higher (Miyamoto et al., 2004; Nagai et al., 2005), consistent with the doses required in the present study to elicit methamphetamine-induced CPP in non-tg mice. Furthermore, although strain differences are inherent (Belzung and Barreau, 2000), an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve for methamphetamine-induced CPP is also expected (Achat-Mendes et al., 2005). Considering that the inverted U-shaped dose-response curve was observed in both gp120-tg and non-tg mice, the leftward shift of the dose-response curve in gp120-tg mice indicated greater sensitivity to the conditioned rewarding effects of methamphetamine in gp120-tg mice.

Genotype differences in associative learning can contribute to the development of CPP. However, the basic learning of a simple association (i.e., lever press for food reward) was not altered in gp120-tg mice, indicating that the genotype differences observed in methamphetamine-induced CPP were attributable to methamphetamine reward and not differences in learning between gp120-tg and non-tg mice. Furthermore, gp120-tg mice did not exhibit locomotor sensitivity to methamphetamine (Roberts et al., 2010), preventing potential motor confounds when assessing methamphetamine-induced CPP. The limited cognitive testing that has been performed in gp120-tg mice indicated that they had no deficits in acquisition in the Morris water maze task (D’Hooge et al., 1999). Specifically, in addition to normal escape latencies, gp120-tg mice showed similar improvements as non-tg controls learning the location of the platform across the blocks of trials. Nevertheless, a deficit in spatial memory retention was observed in 12-month-old mice but not in 3-month-old mice. Thus, gp120-tg mice appear to have unimpaired associative and spatial learning capabilities in simple cognitive tasks. These findings do not preclude the possibility that gp120 expression may cause impairments in more complex cognitive tasks, such as those that involve executive function.

Consistent with findings of the higher sensitivity of gp120-tg mice relative to non-tg mice to the conditioned rewarding effects of methamphetamine, the expression of gp120 protein resulted in increased preference for methamphetamine in mice that had restricted access to the drinking solutions. These alterations in the preference for methamphetamine were unlikely the result of altered taste because the preference for the tastant quinine, a tastant with a bitter taste similar to methamphetamine, was similar in both genotypes. The most striking difference between gp120-tg and non-tg mice was in their preference for the highly palatable reinforcer saccharin, with gp120-tg mice showing greater saccharin preference and consumption compared with non-tg mice. Saccharin is naturally rewarding to rodents due almost exclusively to its sweet taste (Stefurak and van der Kooy, 1992). Interestingly, saccharin consumption has been shown to be a predictor of the development of drug and alcohol dependence in rats (Gosnell et al., 1998; Perry et al., 2007). Consistent with this observation, our findings clearly show that gp120-tg mice exhibited an increased preference for both methamphetamine and saccharin and higher sensitivity to the conditioned rewarding effects of methamphetamine.

When the mice were given unrestricted access to oral methamphetamine self-administration, all of the mice, independent of genotype, decreased methamphetamine preference, indicating an aversion to oral methamphetamine self-administration. Unrestricted access induced a significant aversion to methamphetamine at the same doses that led to small decreases in preference during restricted access to methamphetamine. The different behavioral outcomes obtained under the “restricted” and “unrestricted” paradigms of access to methamphetamine can be explained by differences in the experimental procedures (intermittent vs. continuous drug access, changed vs. unchanged positions of the two bottles per each concentration). Further, considering that in drinking procedures, the onset of drugs’ CNS effects are delayed, the taste of methamphetamine solution may play a differential role in these two procedures (e.g., a conditioned reinforcer vs. a discriminative stimulus) (Meisch, 2001). Interestingly, however, male gp120-tg mice showed increased sensitivity to methamphetamine-induced aversion, reflected by decreased methamphetamine preference at the lowest concentration used. Mice bred for high sensitivity to methamphetamine drank less methamphetamine than mice bred for low sensitivity to methamphetamine (Kamens et al., 2005). Literature findings, together with our results, suggest that methamphetamine sensitivity is better reflected by aversion than preference for methamphetamine drinking solutions. The fact that only male gp120-tg mice displayed high sensitivity to methamphetamine-induced aversion suggests that the effects of the gp120 protein on this measure may be greater in males than in females. Female mice, regardless of genotype, also showed less aversion to methamphetamine than male mice. The sex difference in aversion to methamphetamine in gp120-tg mice was only observed after prolonged unrestricted access to methamphetamine and may be the result of sex hormones, such as interactions between estrogen and gp120 expression with prolonged methamphetamine exposure. For example, studies in in vitro human neuronal cultures have shown that estrogen is neuroprotective and prevents some of the neurotoxicity caused by the combination of HIV proteins and methamphetamine (Turchan et al., 2001). Further investigations are required to elucidate possible sex differences in gp120-tg mice that are exposed to continuous methamphetamine.

An important caveat to the present study is that increased sensitivity to methamphetamine reward may be attributable to lower body weights and/or altered metabolism or pharmacokinetics in gp120-tg mice. However, considering that methamphetamine doses in all experiments were expressed as mg per kg, it is unlikely body weight differences can account for the results presented herein. Furthermore, the assessment of plasma methamphetamine and amphetamine concentrations after acute methamphetamine administration revealed no differences between non-tg and gp120-tg mice. The levels of plasma methamphetamine reported here (~600 ng/ml at 30 min and ~200 ng/ml at 90 min in gp120-tg and non-tg mice) are consistent with those observed in other studies that examined methamphetamine pharmacokinetics in mice. Specifically, plasma levels of methamphetamine were approximately 1000 ng/ml at 15 min (Zombeck et al., 2009) and 200 ng/ml at 120 min (Miyazaki et al., 2006) after methamphetamine administration at the same dose used in the present study. Thus, the expression of gp120 does not alter methamphetamine pharmacokinetics. Furthermore, behavioral studies showed subtle differences between gp120-tg and non-tg mice in methamphetamine-induced stereotyped behavior without a shift of the dose-response curve to the left (Roberts et al., 2010). Thus, the alterations in brain reward function in response to methamphetamine observed in gp120-tg mice in the present study are attributable to the specific neuropathology caused by gp120 expression, including potential alterations in dopaminergic transmission.

Drugs that are abused by humans, regardless of their direct neurotransmitter substrates, increase mesolimbic dopamine release in rodents (Di Chiara and Imperato, 1988). Reward is tightly associated with mesolimbic dopamine function (Ikemoto, 2007; Wise, 2004). For example, the nucleus accumbens is the primary region within the mesolimbic dopamine system responsible for inducing amphetamine-induced CPP in rodents (Carr and White, 1986; Hiroi and White, 1991). Methamphetamine-induced CPP has also been shown to be particularly dependent on astrocyte function in the nucleus accumbens (Narita et al., 2006), although methamphetamine acts directly on dopaminergic terminals to increase dopamine release (Fleckenstein et al., 2007). The reactive astrocytosis observed in gp120-tg mice (Toggas et al., 1994), indicative of diverse brain injury (Eddleston and Mucke, 1993), and vulnerability of DA neurons to gp120-induced neurotoxicity (Agrawal et al., 2010) may both contribute to a compromised mesolimbic dopamine reward system in gp120-tg mice. HIV-induced neuropathology in humans includes two key features that mirror those seen in gp120-tg mice i.e., the susceptibility of the basal ganglia to HIV-induced pathology (Aylward et al., 1993; Kieburtz et al., 1996; Kumar et al., 2009) and indications of widespread reactive astrocytosis (Navia et al., 1986; Weis et al., 1993). Moreover, the relationship between CPP/reward and mesolimbic dopamine function in rodents parallels the relationship observed in human subjects. Similar to rodents, amphetamine-induced CPP has been demonstrated in human subjects (Childs and de Wit, 2009). A subject’s preference for a drug-paired room was predicted by how much the subject “liked” the drug exposure, confirming that place preference is a measure of incentive motivation. Furthermore, functional imaging studies in humans have demonstrated strong associations between striatal activation and reward incentives (Delgado et al., 2000; Elliott et al., 2003). Specifically, striatal areas of the brain (particularly the ventral components; i.e., nucleus accumbens) are activated in response to a positive reward (e.g., money). Thus, HIV-induced neuropathology affects mesolimbic brain regions and astrocyte function, both of which are critical to reward function. However, whether reward function is altered by HIV infection in humans is currently unknown. The present study provides some of the first evidence that HIV-related pathology, such as that induced by the gp120 protein, increases the sensitivity to methamphetamine reward. Although HIV infection involves the interactions of multiple proteins/processes in addition to gp120, the present findings in mice that solely express the gp120 protein may suggest that people infected with HIV may also have increased sensitivity to methamphetamine reward, leading to persistent methamphetamine abuse and complicating treatment strategies in this population.

In conclusion, the present study found that mice that expressed the HIV envelope glycoprotein gp120 in the brain exhibited increased sensitivity to both the rewarding and aversive properties of methamphetamine. Whether similar sensitivity to methamphetamine is present in individuals with HIV is currently unknown, and further research on the complex symptom overlap and interactions between HIV infection and methamphetamine use in patients is required. These findings suggest that the gp120-tg mouse model may be particularly useful in promoting our understanding of the consequences of methamphetamine use and HIV infection on reward and cognitive function and leading to more targeted clinical investigations. Furthermore, the gp120-tg mouse model may be used as a platform to investigate the potential neurobiological mechanisms and treatment strategies for HIV and methamphetamine abuse.

Acknowledgments

Arends for outstanding editorial assistance. This work was supported by Translational Methamphetamine AIDS Research Center (TMARC) grant P50 DA26306 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication. All authors have nothing to disclose. The TMARC is affiliated with the University of California San Diego (UCSD) and Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute (SBMRI). It is comprised of the following individuals: Director – Igor Grant, M.D.; Co-Directors – Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., Cristian L. Achim, M.D., Ph.D., and Scott L. Letendre, M.D.; Center Manager – Steven Paul Woods, Psy.D.; Assistant Center Manager–Aaron M. Carr, B.A.; Clinical Assessment and Laboratory Core: Scott L. Letendre, M.D. (Core Director), Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D., and Rachel Schrier, Ph.D.; Neuropsychiatric Core: Robert K. Heaton, Ph.D. (Core Director), J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D., Mariana Cherner, Ph.D., and Thomas D. Marcotte, Ph.D.; Neuroimaging Core: Gregory Brown, Ph.D. (Core Director), Terry Jernigan, Ph.D., Anders Dale, Ph.D., Thomas Liu, Ph.D., Miriam Scadeng, Ph.D., Christine Fennema-Notestine, Ph.D., and Sarah L. Archibald, M.A.; Neurosciences and Animal Models Core: Cristian L. Achim, M.D., Ph.D. (Core Director), Eliezer Masliah, M.D., and Stuart Lipton, M.D., Ph.D.; Administrative Coordinating Core – Data Management and Information Systems Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, Ph.D. (Unit Leader), and Clint Cushman (Unit Manager); Administrative Coordinating Core – Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, Ph.D. (Unit Leader), Florin Vaida, Ph.D., Reena Deutsch, Ph.D., and Anya Umlauf, M.S.; Administrative Coordinating Core – Participant Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, M.D. (Unit Leader), and Rodney von Jaeger, M.P.H. (Unit Manager); Project 1: Arpi Minassian, Ph.D. (Project Director), William Perry, Ph.D., Mark Geyer, Ph.D., and Brook Henry, Ph.D.; Project 2: Amanda B. Grethe, Ph.D. (Project Director), Martin Paulus, M.D., and Ronald J. Ellis, M.D., Ph.D.; Project 3: Sheldon Morris, M.D., M.P.H. (Project Director), David M. Smith, M.D., M.A.S., and Igor Grant, M.D.; Project 4: Svetlana Semenova, Ph.D. (Project Director), Athina Markou, Ph.D., and James P. Kesby, Ph.D.; Project 5: Marcus Kaul, Ph.D. (Project Director). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests

The National Institutes of Health had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication. AM has received contract research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., F. Hoffman-La Roche, Pfizer, and Astra-Zeneca and honoraria/consulting fees from Abbott GmbH and Company, AstraZeneca, and Pfizer during the past 3 years. The remaining authors report no financial conflicts of interests.

Authors Contributions

SS and AM were responsible for the study concept and design. JPK, DTH, and SS contributed to the acquisition of the animal data. JPK and SS completed the data analysis and interpretation of findings. JPK drafted the manuscript. SS and AM provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All of the authors critically reviewed the content and approved the final version for publication.

References

- Achat-Mendes C, Ali SF, Itzhak Y. Differential effects of amphetamines-induced neurotoxicity on appetitive and aversive Pavlovian conditioning in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1128–1137. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achim CL, Adame A, Dumaop W, Everall IP, Masliah E. Increased accumulation of intraneuronal amyloid β in HIV-infected patients. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2009;4:190–199. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal L, Louboutin JP, Marusich E, Reyes BAS, Van Bockstaele EJ, Strayer DS. Dopaminergic neurotoxicity of HIV-1 gp120: reactive oxygen species as signaling intermediates. Brain Res. 2010;1306:116–130. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aylward EH, Henderer JD, McArthur JC, Brettschneider PD, Harris GJ, Barta PE, Pearlson GD. Reduced basal ganglia volume in HIV-1-associated dementia: results from quantitative neuroimaging. Neurology. 1993;43:2099–2104. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.10.2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford NS, Zhang H, Joyce JA, Scarlis CA, Hanan W, Wu NP, Andre VM, Cohen R, Cepeda C, Levine MS, Harleton E, Sulzer D. Repeated exposure to methamphetamine causes long-lasting presynaptic corticostriatal depression that is renormalized with drug readministration. Neuron. 2008;58:89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzung C, Barreau S. Differences in drug-induced place conditioning between BALB/c and C57Bl/6 mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;65:419–423. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(99)00212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger JR, Nath A. HIV dementia and the basal ganglia. Intervirology. 1997;40:122–131. doi: 10.1159/000150539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC. The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology. 2007;191:391–431. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey CL, Woods SP, Rippeth JD, Gonzalez R, Heaton RK, Grant I. Additive deleterious effects of methamphetamine dependence and immunosuppression on neuropsychological functioning in HIV infection. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr GD, White NM. Anatomical disassociation of amphetamine’s rewarding and aversive effects: an intracranial microinjection study. Psychopharmacology. 1986;89:340–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00174372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW. Substance use and HIV disease progression in the HAART era: implications for the primary prevention of HIV. Life Sci. 2011;88:940–947. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chana G, Everall IP, Crews L, Langford D, Adame A, Grant I, Cherner M, Lazzaretto D, Heaton R, Ellis R, Masliah E. Cognitive deficits and degeneration of interneurons in HIV+ methamphetamine users. Neurology. 2006;67:1486–1489. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240066.02404.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs E, de Wit H. Amphetamine-induced place preference in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Hooge R, Franck F, Mucke L, De Deyn PP. Age-related behavioural deficits in transgenic mice expressing the HIV-1 coat protein gp120. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:4398–4402. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MR, Nystrom LE, Fissell C, Noll DC, Fiez JA. Tracking the hemodynamic responses to reward and punishment in the striatum. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:3072–3077. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.6.3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G. From rats to humans and return: testing addiction hypotheses by combined PET imaging and self-reported measures of psychostimulant effects. Commentary on Volkow et al. “Role of dopamine in drug reinforcement and addiction in humans: results from imaging studies. Behav Pharmacol. 2002;13:371–377. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200209000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddleston M, Mucke L. Molecular profile of reactive astrocytes: implications for their role in neurological disease. Neuroscience. 1993;54:15–36. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90380-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Newman JL, Longe OA, Deakin JFW. Differential response patterns in the striatum and orbitofrontal cortex to financial reward in humans: a parametric functional magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosci. 2003;23:303–307. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-01-00303.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RJ, Childers ME, Cherner M, Lazzaretto D, Letendre S, Grant I. Increased human immunodeficiency virus loads in active methamphetamine users are explained by reduced effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1820–1826. doi: 10.1086/379894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleckenstein AE, Volz TJ, Riddle EL, Gibb JW, Hanson GR. New insights into the mechanism of action of amphetamines. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:681–698. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL. Endocannabinoid signaling system and brain reward: emphasis on dopamine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;81:263–284. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2005.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosnell BA, Krahn DD, Yracheta JM, Harasha BJ. The relationship between intravenous cocaine self-administration and avidity for saccharin. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(97)00579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hestad K, McArthur JH, Dal Pan GJ, Selnes OA, Nance-Sproson TE, Aylward E, Mathews VP, McArthur JC. Regional brain atrophy in HIV-1 infection: association with specific neuropsychological test performance. Acta Neurol Scand. 1993;88:112–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1993.tb04201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin CH, Hardy DJ, Mason KI, Catellon SA, Lam MN, Stefaniak M, Zolnikov B. Verbal and spatial working memory performance among HIV-infected adults. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8:532–538. doi: 10.1017/s1355617702814278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi N, White NM. The amphetamine conditioned place preference: differential involvement of dopamine receptor subtypes and 2 dopaminergic terminal areas. Brain Res. 1991;552:141–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90672-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu S, Sheng WS, Lokensgard JR, Peterson PK, Rock RB. Preferential sensitivity of human dopaminergic neurons to gp120-induced oxidative damage. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:401–410. doi: 10.3109/13550280903296346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S. Dopamine reward circuitry: two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens-olfactory tubercle complex. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56:27–78. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamens HM, Burkhart-Kasch S, McKinnon CS, Li N, Reed C, Phillips TJ. Sensitivity to psychostimulants in mice bred for high and low stimulation to methamphetamine. Genes Brain Behav. 2005;4:110–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2004.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass MD, Liu X, Vigorito M, Chang L, Chang SL. Methamphetamine-Induced Behavioral and Physiological Effects in Adolescent and Adult HIV-1 Transgenic Rats. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2010;5:566–573. doi: 10.1007/s11481-010-9221-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieburtz K, Ketonen L, Cox C, Grossman H, Holloway R, Booth H, Hickey C, Feigin A, Caine ED. Cognitive performance and regional brain volume in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:155–158. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1996.00550020059016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krucker T, Toggas SM, Mucke L, Siggins GR. Transgenic mice with cerebral expression of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 coat protein gp120 show divergent changes in short- and long-term potentiation in CA1 hippocampus. Neuroscience. 1998;83:691–700. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar AM, Fernandez JB, Singer EJ, Commins D, Waldrop-Valverde D, Ownby RL, Kumar M. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in the central nervous system leads to decreased dopamine in different regions of postmortem human brains. J Neurovirol. 2009;15:257–274. doi: 10.1080/13550280902973952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Chang L, Vigorito M, Kass M, Li H, Chang SL. Methamphetamine-Induced Behavioral Sensitization Is Enhanced in the HIV-1 Transgenic Rat. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2009;4:309–316. doi: 10.1007/s11481-009-9160-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez C, Mitchell SJ, Hare CB, John M, Klausner JD. Methamphetamine use, sexual activity, patient-provider communication, and medication adherence among HIV-infected patients in care, San Francisco 2004–2006. AIDS Care. 2009;21:575–582. doi: 10.1080/09540120802385579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Ge N, Achim CL, Hansen LA, Wiley CA. Selective neuronal vulnerability in HIV encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1992;51:585–593. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199211000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masliah E, Heaton RK, Marcotte TD, Ellis RJ, Wiley CA, Mallory M, Achim CL, McCutchan JA, Nelson JA, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Dendritic injury is a pathological substrate for human immunodeficiency virus-related cognitive disorders. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:963–972. doi: 10.1002/ana.410420618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisch RA. Oral drug self-administration: an overview of laboratory animal studies. Alcohol. 2001;24:117–128. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto Y, Yamada K, Nagai T, Mori H, Mishina M, Furukawa H, Noda Y, Nabeshima T. Behavioural adaptations to addictive drugs in mice lacking the NMDA receptor ε1 subunit. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:151–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki I, Asanuma M, Diaz-Corrales FJ, Fukuda M, Kitaichi K, Miyoshi K, Ogawa N. Methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity is regulated by quinone-formation-related molecules. FASEB J. 2006;20:571–573. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4996fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, Letendre SL, Morris S, Umlauf A, Deutsch R, Smith DM, Little S, Rooney A, Franklin DR, Gouaux B, LeBlanc S, Rosario D, Fennema-Notestine C, Heaton RK, Ellis RJ, Atkinson JH, Grant I. Neurocognitive functioning in acute or early HIV infection. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:50–57. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0009-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Noda Y, Ishikawa K, Miyamoto Y, Yoshimura M, Ito M, Takayanagi M, Takuma K, Yamada K, Nabeshima T. The role of tissue plasminogen activator in methamphetamine-related reward and sensitization. J Neurochem. 2005;92:660–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Miyatake M, Narita M, Shibasaki M, Shindo K, Nakamura A, Kuzumaki N, Nagumo Y, Suzuki T. Direct evidence of astrocytic modulation in the development of rewarding effects induced by drugs of abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2476–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nath A. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated neurocognitive disorder Pathophysiology in relation to drug addiction. In: Uhl GR, editor. Addiction Reviews. Vol. 2. Wiley; Hoboken: 2010. pp. 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navia BA, Cho ES, Petito CK, Price RW. The AIDS dementia complex: II. Neuropathology. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:525–535. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Is there a common molecular pathway for addiction? Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/nn1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuen-Jacob E, Arendt G, Wendtland B, Jacob B, Schneeweis M, Wechsler W. Frequency and topographical distribution of CD68-positive macrophages and HIV-1 core proteins in HIV-associated brain lesions. Clin Neuropathol. 1993;12:315–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Gardner EL. Critical assessment of how to study addiction and its treatment: human and non-human animal models. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;108:18–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry JL, Anderson MM, Nelson SE, Carroll ME. Acquisition of i.v. cocaine self-administration in adolescent and adult male rats selectively bred for high and low saccharin intake. Physiol Behav. 2007;91:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purohit V, Rapaka R, Shurtleff D. Drugs of abuse, dopamine, and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders/HIV-associated dementia. Mol Neurobiol. 2011;44:102–110. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8195-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rippeth JD, Heaton RK, Carey CL, Marcotte TD, Moore DJ, Gonzalez R, Wolfson T, Grant I. Methamphetamine dependence increases risk of neuropsychological impairment in HIV infected persons. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:1–14. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AJ, Maung R, Sejbuk NE, Ake C, Kaul M. Alteration of methamphetamine-induced stereotypic behaviour in transgenic mice expressing HIV-1 envelope protein gp120. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;186:222–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DCS, Bennett SAL. Heroin self-administration in rats under a progressive ratio schedule of reinforcement. Psychopharmacology. 1993;111:215–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02245526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson L, Rempel H. Methamphetamine use and HIV symptom self-management. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2006;17:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scibelli AC, McKinnon CS, Reed C, Burkhart-Kasch S, Li N, Baba H, Wheeler JM, Phillips TJ. Selective breeding for magnitude of methamphetamine-induced sensitization alters methamphetamine consumption. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:791–804. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. Motivations associated with methamphetamine use among HIV+ men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Reback CJ. Associations between methamphetamine use and HIV among men who have sex with men: a model for guiding public policy. J Urban Health. 2006;83:1151–1157. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9119-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein PS, Shah A, Gupte R, Liu X, Piepho RW, Kumar S, Kumar A. Methamphetamine toxicity and its implications during HIV-1 infection. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:401–415. doi: 10.1007/s13365-011-0043-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefurak TL, van der Kooy D. Saccharin rewarding, conditioned reinforcing, and memory-improving properties: mediation by isomorphic or independent processes. Behav Neurosci. 1992;106:125–139. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.106.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzer D, Sonders MS, Poulsen NW, Galli A. Mechanisms of neurotransmitter release by amphetamines: a review. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:406–433. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodore S, Cass WA, Nath A, Maragos WF. Progress in understanding basal ganglia, dysfunction as a common target for methamphetamine abuse and HIV-1 neurodegeneration. Curr HIV Res. 2007;5:301–313. doi: 10.2174/157016207780636515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toggas SM, Masliah E, Rockenstein EM, Rall GF, Abraham CR, Mucke L. Central nervous system damage produced by expression of the HIV-1 coat protein gp120 in transgenic mice. Nature. 1994;367:188–193. doi: 10.1038/367188a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toneatto S, Finco O, van der Putten H, Abrignani S, Annunziata P. Evidence of blood-brain barrier alteration and activation in HIV-1 gp120 transgenic mice. AIDS. 1999;13:2343–2348. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199912030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchan J, Anderson C, Hauser KF, Sun QM, Zhang JY, Liu Y, Wise PM, Kruman I, Maragos W, Mattson MP, Booze R, Nath A. Estrogen protects against the synergistic toxicity by HIV proteins, methamphetamine and cocaine. BMC Neurosci. 2001;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict Biol. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis S, Haug H, Budka H. Astroglial changes in the cerebral-cortex of AIDS brains: a morphometric and immunohistochemical investigation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1993;19:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zombeck JA, Gupta T, Rhodes JS. Evaluation of a pharmacokinetic hypothesis for reduced locomotor stimulation from methamphetamine and cocaine in adolescent versus adult male C57BL/6J mice. Psychopharmacology. 2009;201:589–599. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1327-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]