Abstract

Alzheimer disease (AD) has traditionally been thought to involve the misfolding and aggregation of two different factors that contribute in parallel to pathogenesis: amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides, which represent proteolytic fragments of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein, and tau, which normally functions as a neuronally enriched, microtubule-associated protein that predominantly accumulates in axons. Recent evidence has challenged this model, however, by revealing numerous functional interactions between Aβ and tau in the context of pathogenic mechanisms for AD. Moreover, the propagation of toxic, misfolded Aβ and tau bears a striking resemblance to the propagation of toxic, misfolded forms of the canonical prion protein, PrP, and misfolded Aβ has been shown to induce tau misfolding in vitro through direct, intermolecular interaction. In this review we discuss evidence for the prion-like properties of both Aβ and tau individually, as well as the intriguing possibility that misfolded Aβ acts as a template for tau misfolding in vivo.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, amyloid plaque, amyloid-β, neurodegeneration, neurofibrillary tangle, prion, tau

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a slowly progressing neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the misfolding, aggregation and gain of toxicity of amyloid-β (Aβ) and tau in the brain.1,2 Aggregated Aβ, in the form of densely packed fibrils, accumulates extracellularly in structures known as amyloid plaques. The tau aggregates also correspond to tightly packed filaments, but in contrast to plaques, they accumulate intracellularly in diseased neurons, where they are known as neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). The term paired helical filament, or PHF, is often used to describe the individual tau filaments found in NFTs.

Aβ comprises a family of ~40 amino acid long peptide cleavage products of the transmembrane amyloid precursor protein and has no known essential function in normal physiology, but has long been regarded as a primary cause of AD.3,4 The original focus on large, fibrillar Aβ aggregates as possible causative agents for the memory and cognitive decline associated with AD has gradually shifted over the past decade to the realization that smaller, soluble Aβ oligomers are more relevant culprits. Compared with fibrillar Aβ, soluble Aβ oligomers correlate better with neurotoxicity in vivo and are far more toxic than Aβ fibrils to cultured neurons.5–12

Tau was discovered nearly 40 years ago as a microtubule-associated protein (MAP) that stimulates tubulin polymerization,13 but it was not until a decade later that its presence in NFTs was first described.14-16 Surprisingly, beyond its generic MAP function as a stimulator of microtubule (MT) assembly, the only known specific function of tau is that it impedes the movement of kinesin MT motor proteins and their attached cargoes along MTs.17-20 Historically, tau has received much less attention than Aβ in the AD field, despite the fact that a spectrum of neurodegenerative disorders known collectively as non-Alzheimer tauopathies are invariably characterized by PHF accumulation in the brain and can be caused by any of dozens of tau mutations.21 PHF tau is abnormally phosphorylated at dozens of sites,22 some of which appear in vivo in both human AD cases and transgenic mice before the tau assembles into filaments.23

About three decades after Prusiner first described prion driven infection in Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease24 and speculated that a similar infectious process may apply to AD,25 a recent wave of evidence has demonstrated striking biochemical and cell biological similarities between AD and classical prion diseases. In contrast to PrP-based disorders, such as mad cow disease, scrapie and kuru, AD does not appear to be communicable between individuals, but a growing body of data indicate that misfolded, toxic oligomers of Aβ and tau spread through the brain from neuron to nearby neuron much much like misfolded PrP.25-32 For both Aβ8,33 and tau,34-38 moreover, misfolded forms of the peptide or protein can be taken up by neurons containing otherwise normal Aβ or tau, which as a result then misfold, become toxic and spread to other neurons.

In addition to in vivo histopathology evidence,33,35,36,38 several groups recently demonstrated biochemical mechanisms for prion-like propagation of Aβ and tau9,39-42, and of additional proteins whose misfolding into β-sheet-rich structures underlies other well-known neurodegenerative diseases26-28,30,32. Most intriguing in this regard is evidence for Aβ-tau interactions, both physically43,44 and in cell signaling5,9,11,39,45-52. AD can thus be regarded as a disease that requires prion-like behavior of two distinct proteins.

Aβ and Tau Spread Stereotypically Through the Brain

One line of evidence suggesting prion-like mechanisms in AD comes from histological studies showing that aggregated forms of both Aβ and tau spread through the brain by following typecast neuroanatomical patterns. Perceptions about the exact details of these patterns have evolved somewhat over the years, but plaques and tangles do not follow identical blueprints for dispersing through the brain. Plaques first appear in the basal temporal neocortex, then advance to the entorhinal and hippocampal regions before finally spreading throughout the neocortx53. This progression might be explained by the movement of Aβ through anterograde transport and synaptic exchange mechanisms from regions where Aβ aggregation is initiated into nearby areas receiving axonal input from contaminated regions. Consistent with this hypothesis is the recent demonstration that cultured neurons can accomplish direct cell-to-cell transfer of Aβ oligomers8. This intercellular transfer mechanism, in combination with ongoing production of new Aβ monomers and the fragmentation of fibrils and large oligomers into smaller but more numerous seeds that can initiate Aβ aggregation, could fuel the growth of more Aβ oligomers and fibrils.

In contrast to plaques, abnormal tau first appears in proximal axons within the locus coeruleus54, when it becomes immunoreactive with the AT8 monoclonal antibody, which detects tau phosphorylated at S202 and T20523. Evidently, tau at this stage has not yet assembled into PHFs, but instead is in a soluble, pre-NFT state. As AD progresses from pre-symptomatic to clinically detectable stages, the pattern of AT8-positive tau expands first to distal axonal and somatodendritic compartments within affected locus coeruleus neurons, and then sequentially to the entorhinal cortex (EC), dentate gyrus, CA1 region of the hippocampus and the neocortex. Superimposed on this spreading of abnormal tau is its gradual acquisition of additional phosphoepitopes that are diagnostic of diseased neurons, and its conversion into PHFs34. Interestingly, despite compelling evidence that Aβ is upstream of tau in AD pathogenesis5,9,11,39,45-52, abnormal, pre-NFT tau is usually detectable before plaques55,56. This may symbolize that soluble, oligomeric Aβ, rather than plaques, provoke tau pathology, and that the pattern of plaque spreading simply reflects net rates of insoluble Aβ accumulation within various regions of brain over time.

Two groups, using very similar approaches, recently published compelling experimental evidence that the spatiotemporal spread of tau in AD brain also involves transfer of tau from neuron to neuron along defined synaptic circuits36,38. Both groups targeted expression of a human tau transgene specifically in the EC of mice. In both cases, the transgene encoded tau with a P301L mutation that adopts an AD-like phosphorylation profile, forms PHFs and causes the non-Alzheimer tauopathy, FTDP-17, with full penetrance in humans57,58. As the mice aged, they showed progressive tau pathology that began in the EC and subsequently followed the same path of axonal circuitry into the hippocampus as seen in human AD. Notably, this occurred without any detectable expression of human tau mRNA or protein outside of the EC. In other words, the toxic, mutant human tau that was expressed exclusively in the EC caused the endogenous mouse tau to misfold and become toxic, and then spread along synaptic circuits to the hippocampus. Besides confirming that tau pathology spreads along pre-determined, interconnected, neuroanatomical tracks, these data imply a prion-like process whereby misfolded “bad” tau can provoke the toxic misfolding of “good” tau. One important issue that remains to be determined is the mode of neuron-to-neuron transmission of misfolded tau. For example, the available data do not discriminate among models in which toxic tau is transferred from diseased to healthy neurons at synapses, via cycles of exocytosis and endocytosis, via intercellular bridges or by some combination of these or other potential mechanisms that can be imagined.

Aβ as a Prion

While progression of Aβ aggregation in human AD brain has fueled speculation of prionlike mechanisms of misfolding, recent in vivo and in vitro data have provided direct evidence for prion activity of Aβ, and have suggested specific biochemical and biophysical mechanisms to explain Aβ pathology. The strongest in vivo evidence comes from a large body of work demonstrating that injection of misfolded Aβ from either biological or synthetic sources at specific loci in the brains of AD model mice accelerates the appearance of aggregated, transgenically expressed Aβ throughout the brain42,59-62. While these seed-induced Aβ deposits are initially observed in tissue directly surrounding sites of seeding, spreading eventually occurs along axonally connected regions and in separate locations, suggesting that both axonal transport and extracellular routes play a role in the spreading of Aβ throughout the brain.

Building on this substantial body of in vivo data are several lines of in vitro biochemical and biophysical investigation that have provided direct evidence for specific mechanisms in the propagation of Aβ misfolding. Researchers throughout the AD field have long noted anecdotally that purified Aβ often seems to behave in unpredictable ways that suggest an aggregation mechanism capable of following multiple paths. These suspicions were recently confirmed when aliquots of monomeric Aβ from a single pool were aggregated separately, leading to formation of many structurally and immunologically distinct, aliquot-specific Aβ oligomers63. These experiments also demonstrated that exposing specific preformed Aβ oligomer species to monomeric Aβ promotes the aggregation of monomers into oligomeric species of the same size range and immunoreactivity. A straightforward interpretation of these data suggests a model in which the specific folding patterns of oligomers formed early in the aggregation process self-propagate by increasing the probability of similar folding patterns occurring in newly formed oligomers.

While numerous studies of Aβ have relied on the use of oligomers made from synthetic versions of the conventional peptides, Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, Aβ isolated from biological samples, especially from AD brain, typically show much stronger bioactivity across a wide range of assays47,64-66. This may be due, at least in part, to biologically produced Aβ comprising a rich variety of peptide species, including Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, that are distinguished from each other by their bioactivities and potency, N-terminal truncations, C-terminal truncations or extensions, and post-translational modifications of amino acids within the peptide backbone. Indeed, a recent study of the Aβ peptides present in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples revealed more than 20 molecularly distinct peptide species67. As described in the next paragraph, at least one naturally occurring variant of Aβ is both exceptionally toxic and prion-like. It is therefore possible that low abundance, highly potent, infectious forms of Aβ isolated from brain tissue or cell cultures can explain the enhanced potency of biologically produced, vs. synthetic Aβ.

We recently described a specific, prion-like mechanism of “intermolecular infectivity” involving Aβ3(pE)-429, which lacks the first two amino acids found in Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42, and whose initial residue is enzymatically modified from glutamate to pyroglutamylate (pE) by glutaminyl cyclase68. We found that Aβ3(pE)-42 can induce Aβ1-42 to form low-n oligomers that are ~10-fold more cytotoxic to neurons than otherwise comparable oligomers made from Aβ1-42, alone.

Formation of the cytotoxic oligomers typically involved co-incubation of synthetic Aβ3(pE)-42 with a 19-fold molar excess of synthetic Aβ1-42 for 24 h before dilution into primary neuron cultures. Remarkably, if the two peptides were incubated separately for 24 h and then were mixed together at a 1:19 molar ratio of Aβ3(pE)-42 relative to Aβ1-42, the mixtures had negligible cytotoxicity, like that associated with oligomers made from Aβ1-42 alone. Furthermore, cytotoxic mixed oligomers could be serially diluted into freshly dissolved Aβ1-42 monomers with only slight loss of cytotoxicity after each passage. Even after the Aβ3(pE)-42 concentration was serially passaged three times to drop its level from 5% to 0.000625% of the total Aβ present, the final product was nearly 2/3 as cytotoxic as the starting material containing 5% Aβ3(pE)-42. The cytotoxic oligomers, which appeared to be predominantly dimers and trimers, were immunologically distinct from comparably sized oligomers made exclusively from Aβ1–42. These data signify template mediated protein-misfolding by a process in which the original template, Aβ3(pE)-42, can transfer its distinct conformation and cytotoxic properties to Aβ1-42, which then can act as a template itself to induce further, prion-like propagation of toxic Aβ oligomers9.

The in vivo relevance of these results was established by multiple lines of additional evidence. Most notably, putative dimers and trimers containing both conventional and pE-modified Aβ species were detected more commonly in brain cytosol collected post-mortem from AD patients than from normal age-matched controls, and transgenic mice that produced Aβ3(pE)-x experienced massive gliosis and neuron death in the hippocampus by three months of age. Strikingly, the Aβ3(pE)-x levels in these mice were just a few percent of what is commonly found in human AD brain, and neither gliosis nor neuron loss occurred in otherwise identical mice that lacked functional tau genes. The phenotype of the pE-Aβ-producing, tau knockout (KO) mice mimicked the response of primary neurons obtained from tau KO, but otherwise normal mice to cytotoxic oligomers of 5% Aβ3(pE)-42 plus 95% Aβ1–42. Unlike wild type (WT) neurons, the tau KO neurons were not killed by the mixed oligomers9. These collective in vitro and in vivo results emphasize the exceptional potency of pE-modified Aβ and the tau requirement for its cytotoxicity.

Tau as a Prion

Several lines of evidence have recently demonstrated the ability of filamentous tau polymers to propagate by a nucleated assembly mechanism. Monomeric tau is a soluble, natively unfolded protein69 that does not readily form filaments in vitro unless induced to misfold and polymerize by strongly anionic agents, such as arachidonic acid70, heparin71 or RNA72. Small oligomers, especially tau dimers, are intermediates in the filament assembly process44,73. Once filament polymerization has occurred, sonication can fracture the filaments into shorter, more numerous structures that can seed the assembly of additional tau monomers74. Tau filaments therefore have the ability to self-propagate.

Pre-aggregated tau, comprising filaments and apparent oligomers, is able to enter cultured cells and then cause the intracellular tau that they express to misfold and aggregate as well75,76. This general principle has also been demonstrated in vivo through experiments showing that intracerebral injection of aggregation-prone P301S mutant tau can induce the spreading of NFT formation throughout the cortex of mice expressing wild-type human tau, which does not form NFTs spontaneously35. Given the small amount of initially injected material in these experiments, the data indicate that WT human tau was able to adopt at least some critical properties of the aggregated, mutant human tau to continue propagation throughout the brain. The aforementioned studies of P301L tau being expressed exclusively in the EC of transgenic mice, but driving tau pathology into hippocampal structures36,38 constitute further evidence for prion-like behavior of misfolded tau.

The possibility that tau oligomers serve as agents for the spread of tau pathology must be seriously considered as well. Such oligomers have been detected immunologically in AD brain, most notably in neurons that had not yet accumulated NFTs73,77. Furthermore, intracerebral injection of tau oligomers, but neither monomeric nor fibrillar tau, has been shown to be neurotoxic, to cause synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction, and to impair memory78.

Are Tau Prions Seeded by Aβ Prions?

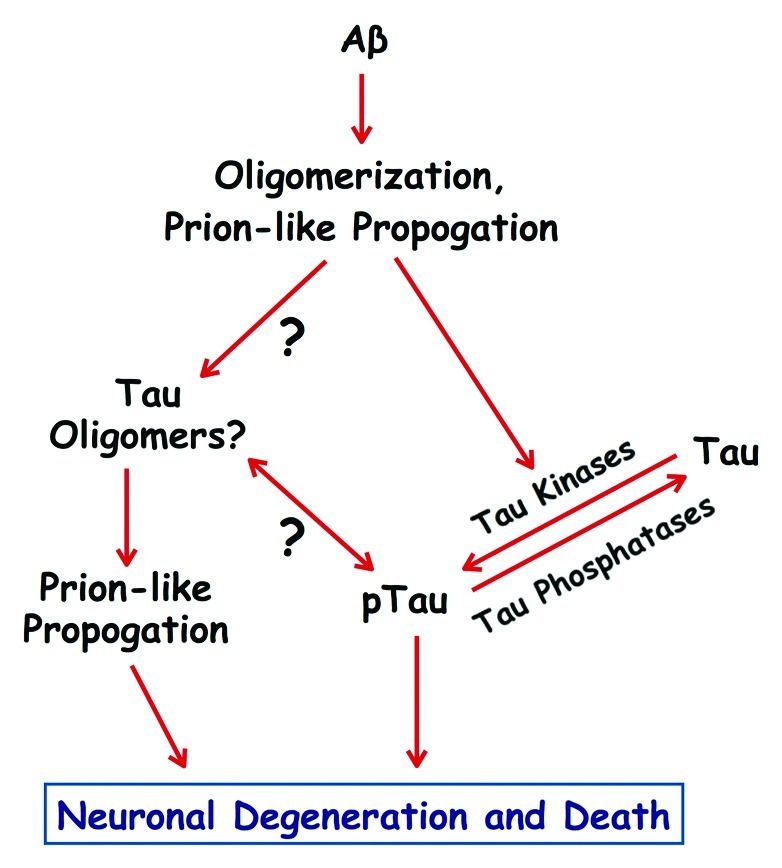

Several groups have described adverse Aβ effects that depend on tau, thereby placing Aβ upstream of tau in AD pathogenesis and establishing tau as an essential protein in development of the disease5,9,11,46,48-50,79,80. At least some of these Aβ-tau connections are indirect, such as Aβinduced activation of protein kinases, which then catalyze abnormal tau phosphorylation11,45,47,51,52. There is also evidence, though, for a direct pathogenic connection between Aβ and tau. In the absence of any other proteins or peptides, Aβ can bind to tau43 and tau monomers can be induced to oligomerize in vitro after exposure to low substoichiometric levels of Aβ oligomers44. These findings raise the obvious possibility that, in vivo, Aβ oligomers seed the initial formation of tau oligomers, which can then self-propagate in the absence of additional input from Aβ (Fig. 1). If such a phenomenon were to occur in vivo, it would represent a seminal step in AD pathogenesis. It might explain, moreover, why so many heroic efforts to target Aβ therapeutically in clinical trials have failed so far. This may be because all experimental patients in such trials must first have received a clinical diagnosis of AD, which can only be made long after tau pathology is already well underway and self-sustaining.

Figure 1.

Prion-like mechanisms in Alzheimer disease. Amyloid-β (Aβ) peptides can form toxic oligomers that are able to propogate by a prion-like mechanism of template-mediated protein misfolding. Aβ oligomers can activate tau kinases, which then catalyze pathogenic phosphorylation of tau (pTau), and may also serve as prion-like seeds that induce tau to oligomerize. Tau oligomers also self-propogate by a prion-like mechanism, and along with pathogenically phosphorylated tau, drive the degeneration and death of neurons involved in memory and cognition. The temporal and functional relationships between pathogenic phosphorylation and oligomerization of tau remain to be determined.

Acknowledgments

The authors recent work on AD has been supported by the Alzheimer Association (grant 4079 to G.S.B.), the Owens Family Foundation (G.S.B.), the Cure Alzheimer Fund (G.S.B.) and NIH/NIGMS training grant T32 GM008136, which funded part of the pre-doctoral training for J.M.N. and M.E.S.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- Aβ

amyloid-β

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- EC

entorhinal cortex

- KO

knockout

- MAP

microtubule-associated protein

- MT

microtubule

- pE

pyroglutamate or pyroglutamylated

- PHF

paired helical filament

- WT

wild type

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Current affiliation: Department of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine; Lerner Research Institute; Cleveland Clinic; Cleveland, OH USA

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/prion/article/22118

References

- 1.Qiang L, Yu W, Andreadis A, Luo M, Baas PW. Tau protects microtubules in the axon from severing by katanin. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3120–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5392-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–66. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selkoe DJ. The molecular pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 1991;6:487–98. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.King ME, Kan H-M, Baas PW, Erisir A, Glabe CG, Bloom GS. Tau-dependent microtubule disassembly initiated by prefibrillar β-amyloid. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:541–6. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200605187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lue LF, Kuo YM, Roher AE, Brachova L, Shen Y, Sue L, et al. Soluble amyloid beta peptide concentration as a predictor of synaptic change in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:853–62. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65184-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLean CA, Cherny RA, Fraser FW, Fuller SJ, Smith MJ, Beyreuther K, et al. Soluble pool of Abeta amyloid as a determinant of severity of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:860–6. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<860::AID-ANA8>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nath S, Agholme L, Kurudenkandy FR, Granseth B, Marcusson J, Hallbeck M. Spreading of neurodegenerative pathology via neuron-to-neuron transmission of β-amyloid. J Neurosci. 2012;32:8767–77. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0615-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nussbaum JM, Schilling S, Cynis H, Silva A, Swanson E, Wangsanut T, et al. Prion-like behaviour and tau-dependent cytotoxicity of pyroglutamylated amyloid-β. Nature. 2012;485:651–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Picone P, Carrotta R, Montana G, Nobile MR, San Biagio PL, Di Carlo M. Abeta oligomers and fibrillar aggregates induce different apoptotic pathways in LAN5 neuroblastoma cell cultures. Biophys J. 2009;96:4200–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seward M, Swanson E, Roberson ED, Bloom GS. Amyloid-β signals through tau to drive neuronal cell cycle re-entry in Alzheimer’s disease. 2012 doi: 10.1242/jcs.1125880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westerman MA, Cooper-Blacketer D, Mariash A, Kotilinek L, Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, et al. The relationship between Abeta and memory in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2002;22:1858–67. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-05-01858.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weingarten MD, Lockwood AH, Hwo S-Y, Kirschner MW. A protein factor essential for microtubule assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:1858–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.5.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, Quinlan M, Wisniewski HM, Binder LI. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:4913–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.13.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kondo J, Honda T, Mori H, Hamada Y, Miura R, Ogawara M, et al. The carboxyl third of tau is tightly bound to paired helical filaments. Neuron. 1988;1:827–34. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90130-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kosik KS, Orecchio LD, Binder L, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM-Y, Lee G. Epitopes that span the tau molecule are shared with paired helical filaments. Neuron. 1988;1:817–25. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixit R, Ross JL, Goldman YE, Holzbaur EL. Differential regulation of dynein and kinesin motor proteins by tau. Science. 2008;319:1086–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1152993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebneth A, Godemann R, Stamer K, Illenberger S, Trinczek B, Mandelkow E. Overexpression of tau protein inhibits kinesin-dependent trafficking of vesicles, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:777–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.3.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stamer K, Vogel R, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Tau blocks traffic of organelles, neurofilaments, and APP vesicles in neurons and enhances oxidative stress. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1051–63. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trinczek B, Ebneth A, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. Tau regulates the attachment/detachment but not the speed of motors in microtubule-dependent transport of single vesicles and organelles. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2355–67. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.14.2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–59. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanger DP, Anderton BH, Noble W. Tau phosphorylation: the therapeutic challenge for neurodegenerative disease. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Porzig R, Singer D, Hoffmann R. Epitope mapping of mAbs AT8 and Tau5 directed against hyperphosphorylated regions of the human tau protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;358:644–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prusiner SB. Novel proteinaceous infectious particles cause scrapie. Science. 1982;216:136–44. doi: 10.1126/science.6801762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prusiner SB. Some speculations about prions, amyloid, and Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:661–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198403083101021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frost B, Diamond MI. Prion-like mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:155–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn2786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goedert M, Clavaguera F, Tolnay M. The propagation of prion-like protein inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jucker M, Walker LC. Pathogenic protein seeding in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:532–40. doi: 10.1002/ana.22615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim J, Holtzman DM. Medicine. Prion-like behavior of amyloid-beta. Science. 2010;330:918–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1198314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SJ, Desplats P, Sigurdson C, Tsigelny I, Masliah E. Cell-to-cell transmission of nonprion protein aggregates. Nature Rev Neurol. 2010;6:702–6. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2010.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novak P, Prcina M, Kontsekova E. Tauons and prions: infamous cousins? J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;26:413–30. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prusiner SB. Cell biology. A unifying role for prions in neurodegenerative diseases. Science. 2012;336:1511–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1222951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harris JA, Devidze N, Verret L, Ho K, Halabisky B, Thwin MT, et al. Transsynaptic progression of amyloid-β-induced neuronal dysfunction within the entorhinal-hippocampal network. Neuron. 2010;68:428–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braak H, Del Tredici K. Alzheimer’s pathogenesis: is there neuron-to-neuron propagation? Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:589–95. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0825-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clavaguera F, Bolmont T, Crowther RA, Abramowski D, Frank S, Probst A, et al. Transmission and spreading of tauopathy in transgenic mouse brain. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:909–13. doi: 10.1038/ncb1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Calignon A, Polydoro M, Suárez-Calvet M, William C, Adamowicz DH, Kopeikina KJ, et al. Propagation of tau pathology in a model of early Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2012;73:685–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo JL, Lee VM. Seeding of normal Tau by pathological Tau conformers drives pathogenesis of Alzheimer-like tangles. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15317–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu L, Drouet V, Wu JW, Witter MP, Small SA, Clelland C, et al. Trans-synaptic spread of tau pathology in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hurtado DE, Molina-Porcel L, Iba M, Aboagye AK, Paul SM, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Abeta accelerates the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology and augments tau amyloidosis in an Alzheimer mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:1977–88. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller Y, Ma B, Nussinov R. Synergistic interactions between repeats in tau protein and Aβ amyloids may be responsible for accelerated aggregation via polymorphic states. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5172–81. doi: 10.1021/bi200400u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pauwels K, Williams TL, Morris KL, Jonckheere W, Vandersteen A, Kelly G, et al. Structural basis for increased toxicity of pathological aβ42:aβ40 ratios in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5650–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.264473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stöhr J, Watts JC, Mensinger ZL, Oehler A, Grillo SK, DeArmond SJ, et al. Purified and synthetic Alzheimer’s amyloid beta (Aβ) prions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:11025–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206555109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo JP, Arai T, Miklossy J, McGeer PL. Abeta and tau form soluble complexes that may promote self aggregation of both into the insoluble forms observed in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1953–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509386103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lasagna-Reeves CA, Castillo-Carranza DL, Guerrero-Muoz MJ, Jackson GR, Kayed R. Preparation and characterization of neurotoxic tau oligomers. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10039–41. doi: 10.1021/bi1016233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Busciglio J, Lorenzo A, Yeh J, Yankner BA. β-amyloid fibrils induce tau phosphorylation and loss of microtubule binding. Neuron. 1995;14:879–88. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90232-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Götz J, Chen F, van Dorpe J, Nitsch RM. Formation of neurofibrillary tangles in P301l tau transgenic mice induced by Abeta 42 fibrils. Science. 2001;293:1491–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin M, Shepardson N, Yang T, Chen G, Walsh D, Selkoe DJ. Soluble amyloid beta-protein dimers isolated from Alzheimer cortex directly induce Tau hyperphosphorylation and neuritic degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5819–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017033108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewis J, Dickson DW, Lin W-L, Chisholm L, Corral A, Jones G, et al. Enhanced neurofibrillary degeneration in transgenic mice expressing mutant tau and APP. Science. 2001;293:1487–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1058189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rapoport M, Dawson HN, Binder LI, Vitek MP, Ferreira A. Tau is essential to β -amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6364–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092136199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roberson ED, Scearce-Levie K, Palop JJ, Yan F, Cheng IH, Wu T, et al. Reducing endogenous tau ameliorates amyloid beta-induced deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Science. 2007;316:750–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1141736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seino Y, Kawarabayashi T, Wakasaya Y, Watanabe M, Takamura A, Yamamoto-Watanabe Y, et al. Amyloid β accelerates phosphorylation of tau and neurofibrillary tangle formation in an amyloid precursor protein and tau double-transgenic mouse model. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:3547–54. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zempel H, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Abeta oligomers cause localized Ca(2+) elevation, missorting of endogenous Tau into dendrites, Tau phosphorylation, and destruction of microtubules and spines. J Neurosci. 2010;30:11938–50. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2357-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Braak H, Del Tredici K. The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:171–81. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0789-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Braak H, Braak E. Frequency of stages of Alzheimer-related lesions in different age categories. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:351–7. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(97)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schönheit B, Zarski R, Ohm TG. Spatial and temporal relationships between plaques and tangles in Alzheimer-pathology. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25:697–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark LN, Poorkaj P, Wszolek Z, Geschwind DH, Nasreddine ZS, Miller B, et al. Pathogenic implications of mutations in the tau gene in pallido-ponto-nigral degeneration and related neurodegenerative disorders linked to chromosome 17. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13103–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, et al. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–5. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eisele YS, Obermüller U, Heilbronner G, Baumann F, Kaeser SA, Wolburg H, et al. Peripherally applied Abeta-containing inoculates induce cerebral beta-amyloidosis. Science. 2010;330:980–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1194516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kane MD, Lipinski WJ, Callahan MJ, Bian F, Durham RA, Schwarz RD, et al. Evidence for seeding of beta -amyloid by intracerebral infusion of Alzheimer brain extracts in beta -amyloid precursor protein-transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3606–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03606.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, et al. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science. 2006;313:1781–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walker LC, Callahan MJ, Bian F, Durham RA, Roher AE, Lipinski WJ. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidosis in betaAPP-transgenic mice. Peptides. 2002;23:1241–7. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(02)00059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kayed R, Canto I, Breydo L, Rasool S, Lukacsovich T, Wu J, et al. Conformation dependent monoclonal antibodies distinguish different replicating strains or conformers of prefibrillar Aβ oligomers. Mol Neurodegener. 2010;5:57. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Davis RC, Marsden IT, Maloney MT, Minamide LS, Podlisny M, Selkoe DJ, et al. Amyloid beta dimers/trimers potently induce cofilin-actin rods that are inhibited by maintaining cofilin-phosphorylation. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shankar GM, Bloodgood BL, Townsend M, Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ, Sabatini BL. Natural oligomers of the Alzheimer amyloid-beta protein induce reversible synapse loss by modulating an NMDA-type glutamate receptor-dependent signaling pathway. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2866–75. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4970-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, et al. Amyloid-beta protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–42. doi: 10.1038/nm1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Portelius E, Westman-Brinkmalm A, Zetterberg H, Blennow K. Determination of beta-amyloid peptide signatures in cerebrospinal fluid using immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:1010–6. doi: 10.1021/pr050475v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schilling S, Zeitschel U, Hoffmann T, Heiser U, Francke M, Kehlen A, et al. Glutaminyl cyclase inhibition attenuates pyroglutamate Abeta and Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology. Nat Med. 2008;14:1106–11. doi: 10.1038/nm.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeganathan S, von Bergen M, Mandelkow E-M, Mandelkow E. The natively unfolded character of tau and its aggregation to Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10526–39. doi: 10.1021/bi800783d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wilson DM, Binder LI. Free fatty acids stimulate the polymerization of tau and amyloid β peptides. In vitro evidence for a common effector of pathogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:2181–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goedert M, Jakes R, Spillantini MG, Hasegawa M, Smith MJ, Crowther RA. Assembly of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like filaments induced by sulphated glycosaminoglycans. Nature. 1996;383:550–3. doi: 10.1038/383550a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kampers T, Friedhoff P, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E. RNA stimulates aggregation of microtubule-associated protein tau into Alzheimer-like paired helical filaments. FEBS Lett. 1996;399:344–9. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patterson KR, Remmers C, Fu Y, Brooker S, Kanaan NM, Vana L, et al. Characterization of prefibrillar Tau oligomers in vitro and in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:23063–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.237974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Friedhoff P, von Bergen M, Mandelkow EM, Davies P, Mandelkow E. A nucleated assembly mechanism of Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15712–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frost B, Jacks RL, Diamond MI. Propagation of tau misfolding from the outside to the inside of a cell. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12845–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808759200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nonaka T, Watanabe ST, Iwatsubo T, Hasegawa M. Seeded aggregation and toxicity of alpha-synuclein and tau: cellular models of neurodegenerative diseases. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:34885–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.148460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lasagna-Reeves CA, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Sarmiento J, Troncoso J, Jackson GR, et al. Identification of oligomers at early stages of tau aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2012;26:1946–59. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-199851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lasagna-Reeves CA, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, Clos AL, Jackson GR, Kayed R. Tau oligomers impair memory and induce synaptic and mitochondrial dysfunction in wild-type mice. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:39. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ittner LM, Ke YD, Delerue F, Bi M, Gladbach A, van Eersel J, et al. Dendritic function of tau mediates amyloid-beta toxicity in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. Cell. 2010;142:387–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vossel KA, Zhang K, Brodbeck J, Daub AC, Sharma P, Finkbeiner S, et al. Tau reduction prevents Abeta-induced defects in axonal transport. Science. 2010;330:198. doi: 10.1126/science.1194653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]