Abstract

Feedback regulatory circuits provided by regulatory T cells (Treg cells) and suppressive cytokines are an intrinsic part of the immune system, along with effector functions. Here we discuss some of the regulatory cytokines that have evolved to permit tolerance to components of self as well as the eradication of pathogens with minimal collateral damage to the host. Interleukin 2 (IL-2), IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) are well characterized, whereas IL-27, IL-35 and IL-37 represent newcomers to the spectrum of anti-inflammatory cytokines. We also emphasize how information accumulated through in vitro as well as in vivo studies of genetically engineered mice can help in the understanding and treatment of human diseases.

The immune system protects humans from myriad invaders in the form of parasites, viruses, bacteria, fungi, germinating pollen grains and so on. However, it is critical to distinguish between friend and foe to maintain homeostasis and prevent host damage. The microbes that live in symbiosis with humans and that, among their many roles, permit humans to digest food, produce vitamins, regulate the development of the immune system and prevent the growth of pathogenic microbes can be classified as ‘friends’1–5. Mammals have a sophisticated immune system that does the tricky job of rejecting the harmful non-self and tolerating microbial friends without reacting to its own constituents. This is a fine line to walk. Incapacitation of the immune system through genetic mutation and exposure to radiation or chemotherapy, among other factors, can lead to life-threatening infections. Lack of regulation, on the contrary, leads to inflammation and autoimmunity.

To accomplish the task noted above, the immune system relies on effector immune responses tailored to eradicate particular pathogens, as well as feedback regulatory circuits provided by regulatory T cells (Treg cells) and suppressive cytokines. The original observations that led to the identification of innate and adaptive immunity did not cover the concept of counter-regulation. It took half a century to show that the immune system can be actively and specifically silenced or made tolerant. Deciphering the mechanisms that lead to immune tolerance has been an arduous journey because of their diversity and complexity. This includes the deletion of autoreactive T cells in the thymus (the so-called ‘central tolerance’) and dominant mechanisms of peripheral tolerance in which suppressive or regulatory T cells, ‘instructed’ by tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs)6–8, prevent or limit the activation of autoreactive T cells.

The concept of regulatory or suppressor T cells is now firmly established9–11. Three main types of CD4+ Treg cells can be distinguished. Two express the transcription factor Foxp3, which can be induced naturally in the thymus (natural Treg cells) or in the periphery (inducible Treg cells). The third type, the Tr1 cells, do not express Foxp3 but secrete interleukin 10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) in response to antigenic stimulation12–14. Foxp3+ T cells have a critical role in the maintenance of self-tolerance, as demonstrated in patients with IPEX syndrome (‘immune dysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy, X-linked’). These patients, who have mutations in the gene encoding Foxp3, suffer from a combination of organ-specific autoimmune diseases15–17. The Foxp3+ T cell population is composed of subsets that can be distinguished on the basis of their expression of cell-surface markers18–20, and they control effector cells such as those of the helper T cell subsets TH1, TH2 and TH17 through the expression or activation of specific helper T cell–associated transcription factors. Expression of the chemokine receptors CCR6, CXCR3, CCR4 and CCR10 allows the separation of human Foxp3+ Treg cells into four independent cell populations21. Human blood Treg cells have also been divided into two subsets based on their expression of CD45RA (a marker of naive cells) and Foxp3. Thus, CD45RA+Foxp3lo cells include naive or resting Treg cells, whereas CD45RA−Foxp3hi cells include effector or activated Treg cells. CD45RA−Foxp3lo cells are not Treg cells22.

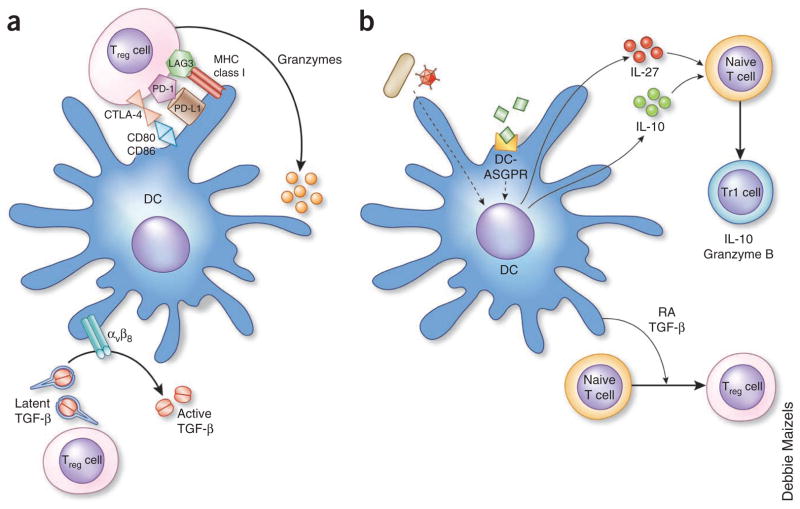

It took considerable effort to establish how Treg cells suppress immune responses. Several mechanisms have been identified that contribute to their suppressive functions (Fig. 1). These include both cell contact– and cell factor-dependent mechanisms, such as the production of IL-10; the production and surface expression of TGF-β; the production of IL-35; the release of cytolytic molecules such as granzyme and perforin; the consumption of IL-2 through high density of cell-surface CD25 (the α-chain of the IL-2 receptor), which ‘weans’ effector T cells from IL-2; and the degradation of ATP through ectonucleotidases; and expression of the inhibitory receptor CTLA-4, which outcompetes the costimulatory receptor CD28 on effector cells for access to the costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on antigen- presenting cells23–26. Many studies have reported alterations in the frequency and/or function of Treg cells in systemic autoimmune diseases27. We will not discuss the strategies that have been proposed for the adoptive transfer of Treg cells into transplant patients or patients suffering from autoimmunity28,29. Instead, this Review will describe some of the regulatory cytokines that are involved in the generation of immunotolerance and protection of the host during immune responses that are induced to eradicate invading pathogens. Much can also be learned from certain pathogens and from malignancies, as they exploit unique mechanisms of host tolerance to evade the immune attack. Clearly, rational understanding of these mechanisms will have a considerable effect on medicine, as it may lead to the development of targeted therapies that will complement the present approaches. These approaches include monoclonal antibodies that antagonize proinflammatory cytokines, chemical agents that block cytokine signaling pathways, deletion of specific cell populations or blockade of costimulation30.

Figure 1.

The dialog between Treg cells and DCs. (a) Treg cells can inhibit the priming of effector T cells by preventing DC maturation through cell surface signaling by CTLA-4, PD-1 or LAG3 or by killing DCs through the secretion of granzymeps. After being stimulated by DCs, T cells can secrete latent TGF-β, which is activated by αVβ8 expressed on the surface of DCs. The activated TGF-β can now signal DCs and other cell types. (b) DCs can induce the differentiation of Treg cells. DCs activated by microbes or by ligation of certain surface molecules such as DC asialoglycoprotein receptor (DC-ASGPR) secrete either IL-27 or IL-10, which induce T cells to produce IL-10 (Tr1 cell). A subset of DCs secrete retinoic acid (RA) and TGF-β, which induce the differentiation of T cells into Treg cells. MHC, major histocompatibility complex.

More specifically, here we will discuss six regulatory cytokines and classify them into two distinct groups on the basis of the extent of the present knowledge. For IL-2, IL-10 and TGF-β, the old triad of anti-inflammatory cytokines, we extract those salient features that distinguish them from each other. We also summarize the known key features of the newcomers IL-27, IL-35 and IL-37. We emphasize how information accumulated through in vitro as well as in vivo studies of genetically engineered mice can help in the understanding and treatment of human disease.

IL-2

IL-2 was discovered 30 years ago through its ability to induce the in vitro growth of activated T cells31. It might be predicted that IL-2 deficiency would lead to immunodeficiency. However, contrary to the expectations at the time, IL-2-deletion in mice does not result in grossly abnormal or impaired lymphocyte development. Instead, such mice die prematurely from invasion of nonlymphoid organs by activated T cells, associated with autoimmune anemia and inflammatory bowel disease32,33. The conundrum was resolved with the discovery of Treg cells that have high expression of CD25 and thereby consume IL-2 (ref. 34).

Patients with mutations in FOXP3 and at least one patient with a CD25 mutation developed severe autoimmune multiorgan involvement, which indicates the importance of IL-2 and Foxp3 for Treg cell function in humans16,17,35. Studies of mice of the nonobese diabetic strain have shown that susceptibility to diabetes is associated with lower expression of IL-2 (refs. 36–39). In fact, IL-2 is critical for the maintenance of Treg cells in the periphery, and neutralization of IL-2 results in autoimmunity40. Conversely, administration of a low dose of IL-2 to mice of the nonobese diabetic strain prevents the development of diabetes and can even induce remission of established disease41,42. IL-2 seems to prevent diabetes by inducing a repertoire of islet-reactive CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells that suppress low-avidity islet-reactive effector cells, which thus escape negative selection in the thymus43.

IL-2 also controls inflammation by inhibiting TH17 differentiation. It does so by interfering with IL-6-dependent signaling events44, including downregulation of expression of the IL-6 receptor and replacement of the transcription factor STAT3 with STAT5 on target DNA-binding sites in genes required for TH17 differentiation44,45. Indeed, Il2−/− mice have higher concentrations of IL-17 in the serum44. The differentiation of TH17 cells is facilitated by the specific expression of Aiolos, a member of the Ikaros family of transcription factors that directly silences the Il2 locus46. Actually, the consumption of IL-2 by Foxp3+ Treg cells facilitates the differentiation of TH17 cells in vitro and in vivo47,48. Thus, administration of IL-2 should be considered for inhibiting IL-17-dependent inflammatory processes.

IL-2 also affects the development of follicular helper T cells (TFH cells), a subset of T cells that control humoral immune responses49–52. TFH cells are characterized by the production of IL-21 and the expression of CXCR5, which allows the localization of these cells to developing germinal centers, where they help B cells undergo isotype switching and somatic mutations52. Human CXCR5+CD4+ T cells can be divided into three subsets according to chemokine-receptor expression. These subsets can be altered in systemic autoimmunity, such as dermatomyositis. Administration of IL-2 to mice infected with influenza virus results in a considerable decrease in the titers of influenza virus–specific immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1). This decrease is associated with a decrease in germinal-center formation and in the number of influenza virus–specific plasma cells. As discussed above for TH17 cells, the inhibitory effect of IL-2 on the development of TFH cells is indirect, as IL-2 interferes with commitment to the TFH lineage without affecting already differentiated TFH cells53–55.

Thus, by increasing the number of Treg cells and decreasing the number of TH17 and TFH cells, IL-2 can prevent the uncontrolled expansion of immune responses and limit overall inflammation. These findings have important therapeutic implications. Although high-dose IL-2 is an approved therapy for metastatic cancer, its clinical value has proven limited, possibly because of the population expansion of Treg cells rather than that of tumor-specific effector cytotoxic T lymphocytes56. In keeping with the regulatory properties of IL-2, two exciting early proof-of-concept studies have demonstrated that the administration of low-dose IL-2 can diminish inflammation and ameliorate disease in patients suffering from chronic graft-versus-host disease or hepatitis C virus–related vasculitis57,58.

IL-10

Initially described as a product of TH2 cells that inhibits the function of TH1 cells, IL-10 is now recognized to be produced by almost every type of cell of the immune system, including most lymphocyte populations and cells of the innate immune system, such as antigen-presenting cells (DCs and macrophages) and granulocytes59–61. IL-10 is the best-characterized member of a family that includes IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24 and IL-26 (ref. 62). At least four viruses ‘highjack’ the gene encoding IL-10 to evade the host immune response.

IL-10 limits the immune response during infection and thus prevents immune system–mediated damage to the host63. There are several layers of regulation of IL-10 expression64. Enhancement or silencing of transcription of the gene encoding IL-10 depends first on chromatin structure and then on accessibility to a set of transcription factors. The next level of regulation is provided by post-transcriptional mechanisms, which might explain why different cells ultimately produce different amounts of IL-10 and for different durations48,65.

In mice, IL-10 deficiency leads to colitis after colonization by particular microorganisms66,67, which suggests an important role for IL-10 in the control of intestinal homeostasis. This is further evident in humans, as mutation in the genes encoding either IL-10 gene or its two receptor components results in an autosomal recessive disease characterized by early-onset severe inflammatory bowel disease68,69.

IL-10 acts at various stages of the immune response in a coordinated way that efficiently restrains the inflammatory process. IL-10 affects many important functions of monocytes, macrophages and DCs, from phagocytosis to the production of cytokines to the expression of costimulators and the processing and presentation of antigens. IL-10 inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines by DCs, macrophages and monocytes. It also inhibits the expression of major histocompatibility complex and costimulatory molecules. In addition, it activates a protolerogenic pathway in DCs through the upregulation of the IL-1 receptor IL-1RA, TGF-β, the inhibitory immunoglobulin-like transcript receptors and major histocompatibility complex class III molecules such as HLA-G70. That in turn may contribute to the induction of IL-10, providing an autocrine loop for reinforcement of immunoregulation. In response to IL-10, DCs can induce the generation of IL-10 from many T cell subsets70, which further reinforces immunotolerance and/or immunoregulation.

The anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 are not mediated solely through effects on DCs and macrophages71. IL-10 also directly acts on proinflammatory TH17 cells and ‘TH1 plus TH17’ cells (positive for IL-17A and interferon-γ) cells, which have high expression of a functional IL-10 receptor72. IL-10 blocks the proliferation of TH17 cells in vivo, which holds promise for the treatment of established colitis72,73. IL-10 also has a direct effect on CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells in vivo by promoting their survival74 and contributes to the function of Foxp3+ Treg cells, as mice with Treg cell–specific ablation of IL-10 develop inflammatory bowel disease. However, such mice do not develop systemic autoimmunity, which suggests that IL-10 production by Foxp3+ Treg cells is necessary for the control of immune responses at environmental interfaces75. In humans, IL-10 has a potent effect on the growth and differentiation of B cells76,77. IL-10 is a switch factor for IgG1 and IgG3 and, in combination with TGF-β, for IgA1 and IgA2 (an isotype found in humans but not in mice), which are associated with mucosal protection. Overall, whereas IL-10 may function in the gut to restrain inflammatory and immune processes (and thus disease), IL-10 also functions to eradicate or control infection by mucosal pathogens and commensal bacteria.

A wide variety of diseases seem to be associated with overproduction of IL-10, including autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, cancers such as melanoma and infectious diseases such as leishmaniasis and possibly tuberculosis60. IL-10 has been administered to a large number of patients suffering from various diseases. Early phase I and II studies showed trends toward efficacy for systemically administered IL-10 in both psoriasis and Crohn’s disease, results that have not been confirmed in larger blinded studies60. It remains possible that the induction of IL-10 at the right site and at the right time, or its targeted delivery, might help control inflammatory pathologies. Targeting of a microbial antigen to the asialoglycoprotein receptor on the surface of human DCs through a fusion protein of antibody to DC asialoglycoprotein receptor and antigen elicits IL-10 production by DCs78. That in turn ‘instructs’ both naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to secrete IL-10 and develop IL-10-dependent immunosuppressive properties. However, antagonists to IL-10 might prove useful for the treatment of chronic infectious diseases and cancer60.

TGF-β

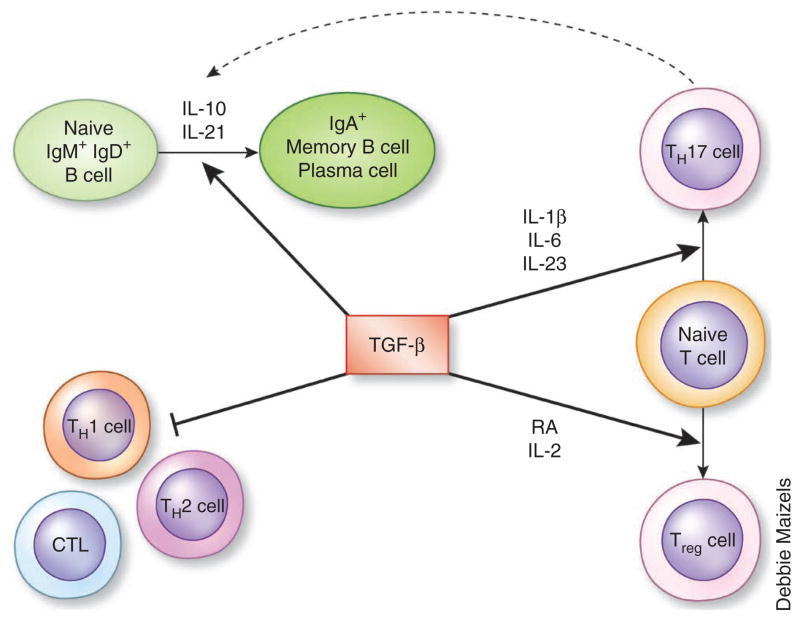

TGF-β belongs to a family of molecules with many roles in a variety of cell types. So far, more than 40 members of this family are known. These proteins have a dimeric structure and cluster in several subfamilies. The TGF-β subfamily includes six isoforms, three of which are expressed in mammals79–82. Of those, TGF-β1 is involved in embryogenesis and has the most prominent role in the immune system by controlling several aspects of inflammatory responses, T cell differentiation, B cell isotype switching and tolerance (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The dual roles of TGF-β in tolerance and immunity. TGF-β inhibits TH1 cells, TH2 cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL), whereas it induces, in combination with other cytokines, the differentiation of Treg cells and TH17 cells. TGF-β together with IL-10 or IL-21 induces CD40-activated B cells to switch into IgA+ B cells, possibly with the help of TH17 cells52.

The pivotal role of TGF-β in immune tolerance was identified in TGF-β1-deficient mice, which develop an early and fatal multifocal inflammatory disease that is prevented by depletion of either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells83. Indeed, most tissues have high expression of the gene encoding TGF-β, and TGF-β seems to have a role in immune homeostasis84. That contrasts with other anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, whose expression is minimal in unstimulated tissues and seems to require triggering by commensal or pathogenic flora. Unlike the disease of IL-10-deficient mice, the inflammatory disease in TGF-β-deficient mice starts early in life, before major challenge with microbes. The systemic inflammation might actually be due to T cell autoreactivity, as demonstrated through genetic studies, most particularly of mice with T cell–specific deficiency in the TGF-β receptor TGF-βRII. Thus, TGF-β signaling is indispensable for limiting T cell responses to self in the periphery and thereby has a critical role in steady-state immunotolerance or homeostasis.

TGF-β is essential for the induction of Foxp3 in naive CD4+ T cells85,86 and does so in synergy with retinoic acid87–89. Notably, TGF-β and retinoic acid are produced by the CD103+ DCs of the small intestine, which are inducers of Treg cells. TGF-β further induces the differentiation of naive T cells into pathogenic TH17 cells90,91 while inhibiting the generation of TH1 and TH2 cells92. The gut shows enrichment for Foxp3+ Treg cells and TH17 cells, and the balance between these two populations is tightly controlled93. In this context, TGF-β is an important switch factor for IgA, the ‘mucosal’ isotype, and mice with genetically altered TGF-β signaling lack IgA94,95. In vitro studies of human cells have further confirmed the role of TGF-β in isotype switching to both IgA1 and IgA2, an activity enhanced by IL-10 and IL-21 (ref. 96).

TGF-β is initially produced as an inactive protein complex that undergoes a multistep maturation process. It is translated as a dimeric pre-pro-TGF-β, which is cleaved to yield the latent TGF-β (LTGF-β) complex composed of homodimeric LAP (latency-associated peptide) that wraps around homodimeric mature TGF-β97. Proteolytic cleavage allows the generation of three different forms of TGF-β: the small latent form (LTGF-β) composed of TGF-β bound to LAP; a large soluble latent form that consists of LTGF-β covalently linked to latent TGF-β-binding protein; and a membrane latent form composed of LTGF-β associated with the membrane protein GARP (LRRC32)98. All three forms require further proteolytic processing to free the active TGF-β component.

The activation of TGF-β proceeds through the degradation of LAP or its conformational alteration. Plasmin, matrix metalloproteinases and thrombospondin-1 participate in proteolytic activation of TGF-β. Integrins αVβ6 and αVβ8 activate TGF-β through different mechanisms after binding to the LAP Arg-Gly-Asp motif. The phenotype of mice with DC-specific αVβ8 deficiency is similar to that of mice with T cell–specific deletion of TGF-β99. Both naive T cells and Treg cells produce latent TGF-β after encountering antigen-loaded DCs. The αVβ8 on DCs then activates latent TGF-β, which results in the release of active soluble TGF-β into the microenvironment. Thus, targeting αVβ8 in DCs might prove useful for the modulation of TGF-β function. Indeed, parasites and bacteria100,101 have learned how to exploit the TGF-β signaling pathway to suppress immune responses by inducing Foxp3 in naive T cells. Studies of TGF-βRII-deficient T cells have suggested that TGF-β contributes to T cell tolerance by enhancing Treg cell function and inhibiting effector T cells. Thus, in the absence of TGF-β signaling in T cells, CD4+ Treg cells progressively disappear from the periphery102,103.

Alterations in specific components of the TGF-β signaling pathway may contribute to a broad range of pathologies, such as cardiovascular and developmental diseases, fibrosis and cancer. Antagonists to the TGF-β pathway are being developed for the treatment of bone diseases, fibrosis and cancer. Hopefully, these antagonists will prove to be safe enough for the targeted manipulation of the TGF-β signaling pathways in the context of autoimmunity and inflammation.

The new triad: IL-27, IL-35 and IL-37

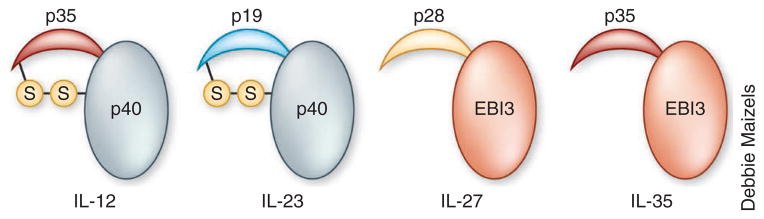

The IL-12 family includes four heterodimeric molecules, IL-12, IL-23, IL-27 and IL-35, which are composed of shared α-chains and β-chains (Fig. 3). Whereas IL-12 and IL-23 have proinflammatory properties, IL-27 and IL-35 have anti-inflammatory properties. IL-12 and IL-23 share the β-chain p40 (IL-12β), whereas IL-27 and IL-35 share the β-chain EBI3. IL-12 and IL-35 share the α-chain p35, whereas IL-23 and IL-27 have unique α-chains104. IL-12 and IL-23 are disulfide-linked heterodimers that are secreted efficiently, whereas IL-27 and IL-35 lack the disulfide linkage and are secreted in small amounts. Whereas IL-35 is produced mainly by Treg cells, the secretion of IL-12, IL-23 and IL-27 by myeloid cells such as macrophages and DCs is dependent on the set of IRF transcription factors that are activated after contact with specific pathogen–associated molecular patterns105.

Figure 3.

Members of the IL-12 family. IL-12 and IL-23 share the β-chain p40 (IL-12β), whereas IL-27 and IL-35 share the β-chain EBI3. IL-12 and IL-35 share the p35 α-chain, whereas IL-23 and IL-27 have unique α-chains. IL-12 and IL-23 are disulfide-linked heterodimers, whereas IL-27 and IL-35 lack the disulfide linkage.

IL-27

IL-27 is composed of p28 (IL-30) and EBI3 subunits106. It is produced mainly by macrophages and DCs. Initially, IL-27 was described as a TH1-promoting factor, but subsequent studies have demonstrated its anti-inflammatory roles. In particular, mice deficient in the receptor for IL-27 that are infected with Leishmania die from excessive immune responses107,108. IL-27 converts activated, inflammatory CD4+ T cells into IL-10-producing TH1 or Tr1 cells109,110. IL-27 upregulates expression of the transcription factor AhR in T cells. After activation, AhR acts in synergy with the transcription factor c-Maf and allows the activation of Il10 and Il21, which results in the generation of Tr1 cells111. IL-27 also prevents the development of TH2 cells and TH17 cells in various inflammatory settings110. Studies of human visceral leishmaniasis have concluded that IL-27 is associated with responses in which T cells produce effector cytokines and IL-10 (ref. 112). Such findings suggest that ‘turning on’ IL-27 may be considered as a treatment for inflammatory diseases. However, IL-27 also suppresses the production of IL-2, which might hamper the growth of Treg cells113, thereby resulting in the induction of colitis in mice114. Thus additional studies are needed to determine how the ability of IL-27 to induce IL-10 counteracts the ability of IL-27 to limit Treg cell populations. Manipulation of the AhR pathway might represent an alternative approach for altering IL-27 signaling for the treatment of inflammatory disorders.

When it acts alone, the IL-27 subunit p28 (IL-30) seems to act as a natural antagonist of signaling via the signal-transducing receptor gp130 (ref. 115). In this scenario, IL-30 blocks signaling mediated by IL-6, IL-11 and IL-27, including IL-6-dependent TH17 responses. Overexpression of IL-30 in mice causes defective thymus-dependent B cell responses due to an inability to form germinal centers. IL-30 can prevent hepatotoxicity mediated by IL-12, interferon-γ and concana-valin A116. Clearly, additional studies are needed for full understanding of the physiological and pathogenic roles of IL-30.

IL-35

IL-35 was identified as an additional anti-inflammatory and immuno-suppressive cytokine only 5 years ago117. Like IL-27, IL-35 is a member of the IL-12 family. IL-35 heterodimers are composed of EBI3 and the IL-12p35 subunit. There is still relatively limited knowledge of this molecule, and it has been provided mostly by studies of mice. IL-35 is not constitutively expressed in tissues84 and is produced mainly by Treg cells118. The gene encoding IL-35 is also transcribed by vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and monocytes after activation with proinflammatory cytokines and lipopolysaccharide84. IL-35 induces the transformation of CD4+ effector T cells into Treg cells that in turn express IL-35 but lack expression of Foxp3, TGF-β and IL-10 (iTreg35 cells)119. The iTreg35 cells generated in vitro can prevent and revert the development of autoimmunity in various mouse models. These include the systemic autoimmunity of Foxp3−/− mice, peptide-induced experimental autoimmune encephalitis and inflammatory bowel disease induced by CD45RB+CD4+ T cells in mice deficient in recombination-activating gene 1 (ref. 119). Conversely, in vitro–generated iTreg35 cells accelerate the development of B16 melanoma and prevent the generation of antitumor CD8+ T cell responses. T cells that secrete IL-35 and have suppressive functions can be induced in the intestines of mice infected with the intestinal parasite Trichuris muris and in the tumor beds of melanoma and colorectal adenocarcinoma.

Ectopic expression of IL-35 in pancreatic beta cells prevents auto-immune diabetes120, and IL-35 protects against collagen-induced arthritis121. In humans, iTreg35 cells can be induced by exposure to virus-infected DCs in vitro in a manner dependent on CD274 (the ligand for the immunoinhibitory receptor PD-1 (PD-L1)) and CD169 (sialoadhesin)122. A burst of information about IL-35 should arrive in the coming years, given its potent suppressive functions.

IL-37

The IL-1 family of cytokines encompasses 11 proteins that share a similar β-barrel structure. Some members of this family are well characterized. IL-1α (IL-1F1), IL-1β (IL-1F2) and IL-18 (IL-1F4) are very important in the initiation of the inflammatory reaction and in driving TH1 and TH17 inflammatory responses. In contrast, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA or IL-1F3) and the receptor antagonist that binds to the receptor IL-1Rrp2 (IL-36Ra or IL-1F5) diminish inflammation by blocking the binding of the agonist receptor ligands. The biological role of IL-37 (IL-1F7) is just starting to be elucidated123. It is transcribed as five different splice variants (IL-1F7a–IL-1F7e). IL-1F7b is the largest isoform, as it is encoded by five of the six exons spanning the gene encoding IL-37. Like IL-1 and IL-18, IL-37 is produced as a precursor that must be cleaved by caspase-1 to be activated124.

Studies of mouse models that express human IL-37 have concluded that this cytokine downregulates inflammation125. Mice with transgenic expression of human IL-37 are less susceptible than are wild-type mice to lipopolysaccharide-induced shock and to dextran sulfate–induced colitis126,127. The effect is IL-10 independent, as antibody blockade of the IL-10 receptor does not reverse IL-37-mediated protection. Bone marrow–transfer studies have indicated that IL-37 originates from hematopoietic cells. Transgenic mice have lower serum and tissue concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines and have less DC activation. Expression of IL-37 in macrophages or epithelial cells dampens the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, whereas human blood cells in which the gene encoding IL-37 has been silenced have higher expression of these cytokines. Transient expression of IL-37 in the liver of mice protects them from concanavalin A– induced hepatitis. IL-37 has thus emerged as a natural suppressor of innate inflammatory responses. These exciting early findings will undoubtedly fuel a greater interest in this unusual member of the IL-1 family.

The way forward

The past decade has witnessed the successful treatment of human autoimmune and inflammatory diseases through the targeting of inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-23) or costimulatory molecules (such as CTLA-4–Ig). Still, many of these diseases remain refractory to such approaches. Cytokine modulation to reinstate self-tolerance might need to be established in the early phases of disease, before irreversible tissue damage develops128.

Greater understanding of the equilibrium between the various effector T cell and suppressor or regulatory T cell pathways will permit the design of more holistic therapeutic interventions. The delivery of cytokines with key roles in these regulatory pathways holds great potential. Given the complexity of these pathways, however, it might be naive to believe that their systemic administration will permit clinicians to control autoimmunity and inflammation. Targeted delivery of IL-2 or IL-10 (ref. 129) to inflammatory sites and targeted activation of latent TGF-β through the local induction of integrins in the relevant sites have already been proposed. Whether targeted induction of IL-27, IL-35 or IL-37 would result in therapeutic benefit remains to be further explored. Undoubtedly, understanding of the relevance of these pathways in specific disease pathogenesis remains a priority. Biomarkers will need to be identified for monitoring responses as well for focusing these approaches to the right disease and/or the right group of patients with individual diseases. Alternatively, for those diseases for which autoantigens have been identified, such as type I diabetes and multiple sclerosis, designing ‘vaccines’ that will specifically elicit tolerance to the autoantigens represents a clear path for development. Existing studies have shown that targeting antigens to DCs in the absence of costimulation can induce antigen-specific tolerance130–132. Certainly, better understanding of the anti- inflammatory cytokine network will bring a renewed approach to the treatment of inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Howes for reading and proofing the manuscript. Supported by the Medical Research Council, UK (U117565642 to A.O.G.) and the US National Institutes of Health (ARO50770-02 and AIO82715 to V.P.).

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Honda K, Littman DR. The microbiome in infectious disease and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:759–795. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee YK, Mazmanian SK. Has the microbiota played a critical role in the evolution of the adaptive immune system? Science. 2010;330:1768–1773. doi: 10.1126/science.1195568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow J, Tang H, Mazmanian SK. Pathobionts of the gastrointestinal microbiota and inflammatory disease. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:473–480. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hill DA, et al. Commensal bacteria-derived signals regulate basophil hematopoiesis and allergic inflammation. Nat Med. 2012;18:538–546. doi: 10.1038/nm.2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinman RM, Hawiger D, Nussenzweig MC. Tolerogenic dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:685–711. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang Q, et al. Visualizing regulatory T cell control of autoimmune responses in nonobese diabetic mice. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:83–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Josefowicz SZ, Lu LF, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells: mechanisms of differentiation and function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:531–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakaguchi S, Miyara M, Costantino CM, Hafler DA. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:490–500. doi: 10.1038/nri2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bilate AM, Lafaille JJ. Induced CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in immune tolerance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:733–758. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allan SE, et al. CD4+ T-regulatory cells: toward therapy for human diseases. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:391–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pot C, Apetoh L, Kuchroo VK. Type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1) in autoimmunity. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roncarolo MG, et al. Interleukin-10-secreting type 1 regulatory T cells in rodents and humans. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:28–50. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng MH, Anderson MS. Monogenic autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:393–427. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett CL, et al. The immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome (IPEX) is caused by mutations of FOXP3. Nat Genet. 2001;27:20–21. doi: 10.1038/83713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wildin RS, et al. X-linked neonatal diabetes mellitus, enteropathy and endocrinopathy syndrome is the human equivalent of mouse scurfy. Nat Genet. 2001;27:18–20. doi: 10.1038/83707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito T, et al. Two functional subsets of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in human thymus and periphery. Immunity. 2008;28:870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zheng Y, et al. Genome-wide analysis of Foxp3 target genes in developing and mature regulatory T cells. Nature. 2007;445:936–940. doi: 10.1038/nature05563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell DJ, Koch MA. Phenotypical and functional specialization of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:119–130. doi: 10.1038/nri2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duhen T, Duhen R, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F, Campbell DJ. Functionally distinct subsets of human FOXP3+ Treg cells that phenotypically mirror effector Th cells. Blood. 2012;119:4430–4440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-392324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyara M, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vignali DA, Collison LW, Workman CJ. How regulatory T cells work. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:523–532. doi: 10.1038/nri2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shevach EM. Mechanisms of foxp3+ T regulatory cell-mediated suppression. Immunity. 2009;30:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi T, Wing JB, Sakaguchi S. Two modes of immune suppression by Foxp3+ regulatory T cells under inflammatory or non-inflammatory conditions. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:424–430. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qureshi OS, et al. Trans-endocytosis of CD80 and CD86: a molecular basis for the cell-extrinsic function of CTLA-4. Science. 2011;332:600–603. doi: 10.1126/science.1202947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miyara M, et al. Human FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in systemic autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2011;10:744–755. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hippen KL, Riley JL, June CH, Blazar BR. Clinical perspectives for regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyara M, Wing K, Sakaguchi S. Therapeutic approaches to allergy and autoimmunity based on FoxP3+ regulatory T-cell activation and expansion. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:749–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steinman L, Merrill JT, McInnes IB, Peakman M. Optimization of current and future therapy for autoimmune diseases. Nat Med. 2012;18:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nm.2625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malek TR, Castro I. Interleukin-2 receptor signaling: at the interface between tolerance and immunity. Immunity. 2010;33:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schorle H, Holtschke T, Hunig T, Schimpl A, Horak I. Development and function of T cells in mice rendered interleukin-2 deficient by gene targeting. Nature. 1991;352:621–624. doi: 10.1038/352621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kündig TM, et al. Immune responses in interleukin-2-deficient mice. Science. 1993;262:1059–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.8235625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Pillars article: immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 2011;186:3808–3821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caudy AA, Reddy ST, Chatila T, Atkinson JP, Verbsky JW. CD25 deficiency causes an immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked-like syndrome, and defective IL-10 expression from CD4 lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:482–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pociot F, et al. Genetics of type 1 diabetes: what’s next? Diabetes. 2010;59:1561–1571. doi: 10.2337/db10-0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hulme MA, Wasserfall CH, Atkinson MA, Brusko TM. Central role for interleukin-2 in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2012;61:14–22. doi: 10.2337/db11-1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tang Q, et al. Central role of defective interleukin-2 production in the triggering of islet autoimmune destruction. Immunity. 2008;28:687–697. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamanouchi J, et al. Interleukin-2 gene variation impairs regulatory T cell function and causes autoimmunity. Nat Genet. 2007;39:329–337. doi: 10.1038/ng1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3+CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon WL, Shapiro AM, Rajotte RV, Power R. Combination therapy with sirolimus and interleukin-2 prevents spontaneous and recurrent autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2002;51:638–645. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grinberg-Bleyer Y, et al. IL-2 reverses established type 1 diabetes in NOD mice by a local effect on pancreatic regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1871–1878. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liston A, Siggs OM, Goodnow CC. Tracing the action of IL-2 in tolerance to islet-specific antigen. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:338–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurence A, et al. Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity. 2007;26:371–381. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang XP, et al. Opposing regulation of the locus encoding IL-17 through direct, reciprocal actions of STAT3 and STAT5. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:247–254. doi: 10.1038/ni.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quintana FJ, et al. Aiolos promotes TH17 differentiation by directly silencing Il2 expression. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:770–777. doi: 10.1038/ni.2363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y, et al. Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promote T helper 17 cell development in vivo through regulation of interleukin-2. Immunity. 2011;34:409–421. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pandiyan P, et al. CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells promote Th17 cells in vitro and enhance host resistance in mouse Candida albicans Th17 cell infection model. Immunity. 2011;34:422–434. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crotty S. Follicular helper CD4 T cells (TFH) Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deenick EK, Ma CS, Brink R, Tangye SG. Regulation of T follicular helper cell formation and function by antigen presenting cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:111–118. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vinuesa CG, Cyster JG. How T cells earn the follicular rite of passage. Immunity. 2011;35:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morita R, et al. Human blood CXCR5+CD4+ T cells are counterparts of T follicular cells and contain specific subsets that differentially support antibody secretion. Immunity. 2011;34:108–121. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ballesteros-Tato A, et al. Interleukin-2 inhibits germinal center formation by limiting T follicular helper cell differentiation. Immunity. 2012;36:847–856. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Johnston RJ, Choi YS, Diamond JA, Yang JA, Crotty S. STAT5 is a potent negative regulator of TFH cell differentiation. J Exp Med. 2012;209:243–250. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Malek TR, Khan WN. IL-2: Fine-tuning the Germinal Center Reaction. Immunity. 2012;36:702–704. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahmadzadeh M, Rosenberg SA. IL-2 administration increases CD4+CD25hiFoxp3+ regulatory T cells in cancer patients. Blood. 2006;107:2409–2414. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koreth J, et al. Interleukin-2 and regulatory T cells in graft-versus-host disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2055–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saadoun D, et al. Regulatory T-cell responses to low-dose interleukin-2 in HCV-induced vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2067–2077. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.O’Garra A, Barrat FJ, Castro AG, Vicari A, Hawrylowicz C. Strategies for use of IL-10 or its antagonists in human disease. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:114–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sabat R, et al. Biology of interleukin-10. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:331–344. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Commins S, Steinke JW, Borish L. The extended IL-10 superfamily: IL-10, IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24, IL-26, IL-28, and IL-29. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:1108–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li MO, Flavell RA. Contextual regulation of inflammation: a duet by transforming growth factor-β and interleukin-10. Immunity. 2008;28:468–476. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Saraiva M, O’Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Murray PJ, Smale ST. Restraint of inflammatory signaling by interdependent strata of negative regulatory pathways. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:916–924. doi: 10.1038/ni.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Izcue A, Coombes JL, Powrie F. Regulatory lymphocytes and intestinal inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:313–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kühn R, Lohler J, Rennick D, Rajewsky K, Muller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993;75:263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Klein C, Shah N, Grimbacher B. IL-10 and IL-10 receptor defects in humans. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2011;1246:102–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Glocker EO, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2033–2045. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gregori S, et al. Differentiation of type 1 T regulatory cells (Tr1) by tolerogenic DC-10 requires the IL-10-dependent ILT4/HLA-G pathway. Blood. 2011;116:935–944. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Barrat FJ, et al. In vitro generation of interleukin 10-producing regulatory CD4+ T cells is induced by immunosuppressive drugs and inhibited by T helper type 1 (Th1)- and Th2-inducing cytokines. J Exp Med. 2002;195:603–616. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huber S, et al. Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3− and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34:554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chaudhry A, et al. Interleukin-10 signaling in regulatory T cells is required for suppression of Th17 cell-mediated inflammation. Immunity. 2011;34:566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murai M, et al. Interleukin 10 acts on regulatory T cells to maintain expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and suppressive function in mice with colitis. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/ni.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rousset F, et al. Interleukin 10 is a potent growth and differentiation factor for activated human B lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1890–1893. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Defrance T, et al. Interleukin 10 and transforming growth factor β cooperate to induce anti-CD40-activated naive human B cells to secrete immunoglobulin A. J Exp Med. 1992;175:671–682. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.3.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li D, et al. Targeting self- and foreign antigens to dendritic cells via DC-ASGPR generates IL-10-producing suppressive CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2012;209:109–121. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Li MO, Flavell RA. TGF-β: a master of all T cell trades. Cell. 2008;134:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tran DQ. TGF-β: the sword, the wand, and the shield of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4:29–37. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Konkel JE, Chen W. Balancing acts: the role of TGF-β in the mucosal immune system. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Regateiro FS, Howie D, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. TGF-β in transplantation tolerance. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shull MM, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-β1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992;359:693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li X, et al. IL-35 is a novel responsive anti-inflammatory cytokine–a new system of categorizing anti-inflammatory cytokines. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chen W, et al. Conversion of peripheral CD4+CD25- naive T cells to CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells by TGF-β induction of transcription factor Foxp3. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1875–1886. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Dardalhon V, et al. IL-4 inhibits TGF-β-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-β, generates IL-9+IL-10+Foxp3− effector T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/ni.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sun CM, et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1775–1785. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Coombes JL, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu Y, et al. A critical function for TGF-β signaling in the development of natural CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:632–640. doi: 10.1038/ni.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ghoreschi K, et al. Generation of pathogenic TH17 cells in the absence of TGF-beta signalling. Nature. 2010;467:967–971. doi: 10.1038/nature09447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gutcher I, et al. Autocrine transforming growth factor-β1 promotes in vivo Th17 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2011;34:396–408. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li MO, Wan YY, Flavell RA. T cell-produced transforming growth factor-beta1 controls T cell tolerance and regulates Th1- and Th17-cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;26:579–591. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cerutti A, Rescigno M. The biology of intestinal immunoglobulin A responses. Immunity. 2008;28:740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Litinskiy MB, et al. DCs induce CD40-independent immunoglobulin class switching through BLyS and APRIL. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:822–829. doi: 10.1038/ni829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dullaers M, et al. A T cell-dependent mechanism for the induction of human mucosal homing immunoglobulin A-secreting plasmablasts. Immunity. 2009;30:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Shi M, et al. Latent TGF-β structure and activation. Nature. 2011;474:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature10152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Tran DQ, et al. GARP (LRRC32) is essential for the surface expression of latent TGF-β on platelets and activated FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:13445–13450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901944106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Travis MA, et al. Loss of integrin αVβ8 on dendritic cells causes autoimmunity and colitis in mice. Nature. 2007;449:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature06110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Grainger JR, et al. Helminth secretions induce de novo T cell Foxp3 expression and regulatory function through the TGF-β pathway. J Exp Med. 2010;207:2331–2341. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Atarashi K, et al. Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science. 2011;331:337–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1198469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li MO, Sanjabi S, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-beta controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity. 2006;25:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Marie JC, Liggitt D, Rudensky AY. Cellular mechanisms of fatal early-onset autoimmunity in mice with the T cell-specific targeting of transforming growth factor-beta receptor. Immunity. 2006;25:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vignali DA, Kuchroo VK. IL-12 family cytokines: immunological playmakers. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:722–728. doi: 10.1038/ni.2366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Molle C, Goldman M, Goriely S. Critical role of the IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 complex in TLR-mediated IL-27p28 gene expression revealing a two-step activation process. J Immunol. 2010;184:1784–1792. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pflanz S, et al. IL-27, a heterodimeric cytokine composed of EBI3 and p28 protein, induces proliferation of naive CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2002;16:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Villarino A, et al. The IL-27R (WSX-1) is required to suppress T cell hyperactivity during infection. Immunity. 2003;19:645–655. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00300-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hamano S, et al. WSX-1 is required for resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi infection by regulation of proinflammatory cytokine production. Immunity. 2003;19:657–667. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00298-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pot C, Apetoh L, Kuchroo VK. Type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1) in autoimmunity. Semin Immunol. 2011;23:202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wojno ED, Hunter CA. New directions in the basic and translational biology of interleukin-27. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Apetoh L, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor interacts with c-Maf to promote the differentiation of type 1 regulatory T cells induced by IL-27. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:854–861. doi: 10.1038/ni.1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ansari NA, et al. IL-27 and IL-21 are associated with T cell IL-10 responses in human visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 2011;186:3977–3985. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wojno ED, et al. A role for IL-27 in limiting T regulatory cell populations. J Immunol. 2011;187:266–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1004182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cox JH, et al. IL-27 promotes T cell-dependent colitis through multiple mechanisms. J Exp Med. 2011;208:115–123. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stumhofer JS, et al. A role for IL-27p28 as an antagonist of gp130-mediated signaling. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1119–1126. doi: 10.1038/ni.1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dibra D, et al. Interleukin-30: a novel antiinflammatory cytokine candidate for prevention and treatment of inflammatory cytokine-induced liver injury. Hepatology. 2012;55:1204–1214. doi: 10.1002/hep.24814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Collison LW, et al. The inhibitory cytokine IL-35 contributes to regulatory T-cell function. Nature. 2007;450:566–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chaturvedi V, Collison LW, Guy CS, Workman CJ, Vignali DA. Cutting edge: Human regulatory T cells require IL-35 to mediate suppression and infectious tolerance. J Immunol. 2011;186:6661–6666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 119.Collison LW, et al. IL-35-mediated induction of a potent regulatory T cell population. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1093–1101. doi: 10.1038/ni.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bettini M, Castellaw AH, Lennon GP, Burton AR, Vignali DA. Prevention of autoimmune diabetes by ectopic pancreatic beta-cell expression of interleukin-35. Diabetes. 2012;61:1519–1526. doi: 10.2337/db11-0784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kochetkova I, Golden S, Holderness K, Callis G, Pascual DW. IL-35 stimulation of CD39+ regulatory T cells confers protection against collagen II-induced arthritis via the production of IL-10. J Immunol. 2010;184:7144–7153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Seyerl M, et al. Human rhinoviruses induce IL-35-producing Treg via induction of B7–H1 (CD274) and sialoadhesin (CD169) on DC. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:321–329. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Dunn E, Sims JE, Nicklin MJ, O’Neill LA. Annotating genes with potential roles in the immune system: six new members of the IL-1 family. Trends Immunol. 2001;22:533–536. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kumar S, et al. Interleukin-1F7B (IL-1H4/IL-1F7) is processed by caspase-1 and mature IL-1F7B binds to the IL-18 receptor but does not induce IFN-γ production. Cytokine. 2002;18:61–71. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2002.0873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Nold MF, et al. IL-37 is a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.McNamee EN, et al. Interleukin 37 expression protects mice from colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:16711–16716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111982108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Bulau AM, et al. In vivo expression of interleukin-37 reduces local and systemic inflammation in concanavalin A-induced hepatitis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:2480–2490. doi: 10.1100/2011/968479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Sakaguchi S, Powrie F, Ransohoff RM. Re-establishing immunological self-tolerance in autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2012;18:54–58. doi: 10.1038/nm.2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Schwager K, et al. The antibody-mediated targeted delivery of interleukin-10 inhibits endometriosis in a syngeneic mouse model. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2344–2352. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Hawiger D, et al. Dendritic cells induce peripheral T cell unresponsiveness under steady state conditions in vivo. J Exp Med. 2001;194:769–779. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Tarbell KV, et al. Dendritic cell-expanded, islet-specific CD4+CD25+CD62L+ regulatory T cells restore normoglycemia in diabetic NOD mice. J Exp Med. 2007;204:191–201. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Mukhopadhaya A, et al. Selective delivery of beta cell antigen to dendritic cells in vivo leads to deletion and tolerance of autoreactive CD8+ T cells in NOD mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6374–6379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802644105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]