Abstract

Vitamin E (α-tocopherol) is the major lipid soluble antioxidant in most animal species. By controlling the secretion of vitamin E from the liver, the α-tocopherol transfer protein (αTTP) regulates whole-body distribution and levels of this vital nutrient. However, the mechanism(s) that regulate the expression of this protein are poorly understood. Here we report that transcription of the TTPA gene in immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) is induced by oxidative stress and by hypoxia, by agonists of the nuclear receptors PPARα and RXR, and by increased cAMP levels. The data show further that induction of TTPA transcription by oxidative stress is mediated by an already-present transcription factor, and does not require de novo protein synthesis. Silencing of the cAMP response element binding (CREB) transcription factor attenuated transcriptional responses of the TTPA gene to added peroxide, suggesting that CREB mediates responses of this gene to oxidative stress. Using a 1.9 Kb proximal segment of the human TTPA promoter together with site-directed mutagenesis approach, we found that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that are commonly found in healthy humans dramatically affect promoter activity. These observations suggest that oxidative stress and individual genetic makeup contribute to vitamin E homeostasis in humans. These findings may explain the variable responses to vitamin E supplementation observed in human clinical trials.

Keywords: tocopherol, oxidative stress, single nucleotide polymorphism

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin E is a collective name for a family of neutral plant lipids (tocols), of which α-tocopherol is selectively retained in the vertebrates and hence is considered the most biologically active form. α-tocopherol’s characteristic hydrophobicity, localization in cell membranes and efficacy in scavenging lipid radicals contributed to its common definition as an important lipid-soluble antioxidant in humans (1–4). Accordingly, vitamin E status is thought to influence risk for diseases with an oxidative stress component, including Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), Downs syndrome (DS), cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and ataxia (5-13). Possible antioxidant-independent actions of vitamin E have also been raised (see (14,15) for discussions).

The extreme hydrophobicity of α-tocopherol poses a major thermodynamic barrier to its distribution and transport through the aqueous milieu of the cytosol and circulation. In the liver, α-tocopherol is bound to alpha tocopherol transfer protein (αTTP) that catalyzes its transport between intracellular membranes and facilitates incorporation of the vitamin into lipoproteins for delivery of the vitamin to other tissues (16,17). Consequently, αTTP regulates whole-body levels and distribution of α-tocopherol. The critical function of αTTP in regulating vitamin E homeostasis is underscored by observations that heritable mutations in the TTPA gene result in ataxia with vitamin E deficiency (AVED; OMIM #277460), characterized by progressive spinocerebellar ataxia and low serum α-tocopherol levels (18,19). Similarly, αTTP-null mice present low vitamin E levels, ataxic phenotype and increased levels of oxidative stress markers in the plasma, brain, heart, lung and placenta (20–23). Importantly, the linear correlation between plasma concentrations of α-tocopherol and αTTP dosage in the Ttpa+/+, Ttpa+/− and Ttpa−/− mice (24) indicate that αTTP determines systemic vitamin E levels. In support of such relationship we recently demonstrated that the anti-proliferative effect of α-tocopherol in prostate cancer cells is linearly correlated to cellular αTTP expression levels (25).

αTTP displays a distinctly narrow tissue expression profile. It is highly expressed in the liver and to a lesser extent in the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex of the brain, kidney, and lung (21,26). αTTP is also expressed in human placental trophoblasts and in murine uterus (24,27–29), where it may regulate delivery of α-tocopherol to the developing embryo. Despite the well-documented role of αTTP as an indispensable protein in maintaining normal α-tocopherol levels, the mechanism(s) that control the tissue-specific expression of the protein remain incompletely understood.

The majority of studies that address the regulation of αTTP levels focused on the relationship between the protein and its ligand, α-tocopherol. It has been reported that dietary vitamin E deficiency lowered αTTP protein levels in the rat, suggesting that α-tocopherol stabilizes the protein (30). Indeed, we recently found that α-tocopherol protects αTTP from ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation (31). While in some in vivo studies vitamin E status did not affect αTTP protein levels (32–34), other reports indicated that dietary vitamin E depletion (35) or repletion (33) markedly influenced mRNA levels. Dietary conjugated linoleic acid was recently shown to increase expression of hepatic αTTP (34,36). Other studies examined whether oxidative stress modulates αTTP expression. Thus, it was reported that hyperoxia decreased αTTP expression in rat liver (37), that smoke-induced oxidative stress did not affect hepatic αTTP protein levels in the mouse (32), and that in the zebrafish and in cultured human trophoblast, pro-oxidants increased αTTP expression (38,39). In summary, available information does not provide us with a thorough and consistent understanding regarding the mechanisms that regulate αTTP levels.

In the studies described here, we began to uncover the mechanisms that regulate transcription of the TTPA gene. Specifically, we report our findings regarding the transcriptional responses of the TTPA gene to oxidative stress, vitamin E, cAMP, and modulators of two nuclear receptors. Furthermore, we report on the functional outcomes of single nucleotide polymorphism in the TTPA promoter that are commonly found in healthy humans.

METHODS

Cell lines

Since expression of aTTP in primary hepatocytes dramatically decreases following isolation (REF), we employed immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) that endogenously express the protein (31) as a model system. IHH (generous gift from R. Ray, St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% calf serum (Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT) as described in (40).

CREB knock-down

Lentiviral shRNA constructs targeted against human CREB (TRCN0000007308, or a control shRNA) in the pLKO vector were transfected into HEK293T cells using Lipofectamine-Plus (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Culture media from 100-mm dishes were harvested 24 and 48 hours post-transfection, pooled, and virus particles pelleted by centrifugation at 100,000 × g for 1.5 hours. The resuspended lentivirus was transduced with polybrene (4 μg/ml) into IHH cells. Twenty-four hours after infection, the cells were infected with another lentivirus dose and treated with 200 μM of hydrogen peroxide for 3 hours, and lysed 24 hours later. Knock-down efficiency was evaluated by immunoblotting using a rabbit anti-human anti-CREB antibody (generous gift of Dr. Ed Greenfield; CWRU, Cleveland, OH).

Cell treatments and RNA harvest

To identify chemical modulators of TTPA transcription, IHH cells were treated for 3 hours with 1 μM of GW0742 (PPARδ agonist), WY14643 (PPARα agonist), TNFα, Troglitazone (PPARγ agonist), 9-cis retinoic acid, all-trans retinoic acid or 0.5 mM 3-isobutyl-l-methylxanthine (IBMX; phosphodiesterase inhibitor), 24 hours with 200 μM deferoxamine (DFX; a hypoxic mimetic; (41)); 3 hours with 200 μM hydrogen peroxide; 16 hours with 1 μM dexamethasone or 100 μM d-α-tocopherol (Acros Organics, NJ), or 30 minutes with 2.5 μM or 10 μM Bay 11-7085 (NF-κB inhibitor). Appropriate solvent was used as vehicle control. RNA was harvested with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and reverse transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Taqman expression assays for Fam-labeled TTPA (Hs00609398_m1), MT1A (Hs00831826_s1) and 18s (Hs99999901_s1) were used in combination with Fast Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in a 96 well format on a StepOnePlus real time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). The data were analyzed according to the Livak method for comparative real-time PCR (42).

Generation and measurements of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

IHH cells were pre-treated with 100 μM d-α-tocopherol (in ethanol), or 1 mM N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) for 16 hours. Oxidative stress was induced by challenging the cells with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 3 hours. 10 μg/ml dichloro-fluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA, Invitrogen) was added in HBSS without phenol red during the final hour of H2O2 treatment and DCF fluorescence was read on a plate reader (excitation = 485 nm; emission = 535 nm). Raw fluorescence was normalized to DNA content as determined by bisbenzamide assay (43). Bisbenzamide fluorescence was measured with a plate reader (excitation = 365 nm; emission = 460 nm).

Western blotting

Endogenous αTTP expression was determined in lysates prepared from liver, heart, cerebellum, prefrontal cortex, kidney, and intestine of 8 days old C57Bl/6 mice using a rat polyclonal 12D7 antibody (generous gift of H. Arai, University of Tokyo). Expression of αTTP in IHH cells was determined using the CW201P antibody generated in rabbits against the purified recombinant human αTTP.

Molecular biology

A 1904 bp fragment of human genomic DNA immediately 5′ of the ATG translational start site of TTPA (NC_000008.10 chromosome 8, 8q12.3; range 63998612-64000612) was amplified from genomic human DNA, shuttled through the pDRIVE vector (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and ligated into the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) where it drives expression of the luciferase reporter gene. Potential regulatory cis-acting elements in this promoter sequence were annotated by identifying putative liver-specific transcription factor binding sites that are conserved in human, mouse, zebrafish, chicken, and chimpanzee using the web-based algorithms MatInspector (44) and MultAlin (45). Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that commonly occur in the TTPA promoter of healthy humans were identified in public databases (dbSNP), and introduced into the 1.9 Kb promoter construct by site directed mutagenesis. All final constructs were verified by sequencing.

Reporter assays

IHH cells were plated in triplicate 24-well plates and co-transfected with the luciferase reporter construct (pGL3B-TTPA), together with the β-galactosidase-expressing pCH110 (Pharmacia) using Lipofectamine Plus (Invitrogen). Promoter-less pGL3B was used as a measure of background luciferase activity. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with indicated concentrations of chemicals for twenty-four hours. Following lysis, luciferase activity was measured according to manufacturer instructions (Promega), and normalized to β-galactosidase activity to account for variations in transfection efficiency.

Results

Transcriptional regulation of the tocopherol transfer protein

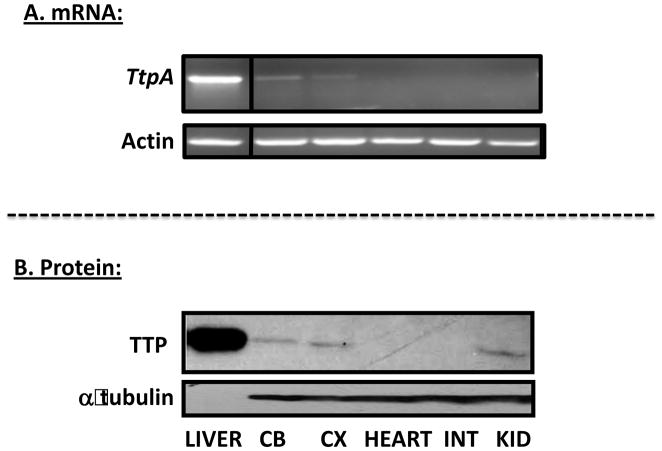

Examination of murine Ttpa gene expression in 8 days old C57Bl/6J mice revealed, in agreement with previous reports (21,46), that αTTP mRNA and protein levels are highest in the liver, significant in the cerebellum, cortex, and kidney, and absent from the intestine and heart (Figure 1). In all tissues, we observed close correspondence between the levels of the mRNA detected by RT-PCR, and those of the protein, revealed by immunoblotting. These data indicate that the Ttpa gene is differentially expressed at the transcriptional level in various tissues.

Figure 1. Tissue-specific expression of the tocopherol transfer protein.

RNA was harvested from indicated tissues of an 8 days old mouse, and used to determine mRNA levels of αTTP and actin using RT-PCR (top two panels) or for measuring αTTP and α-tubulin protein levels using immunoblotting (bottom two panels). Ten μg of liver protein and 200 μg of cerebellum (CB), cortex (CX), heart, intestine (INT) and kidney (KID) were loaded on the indicated lanes.

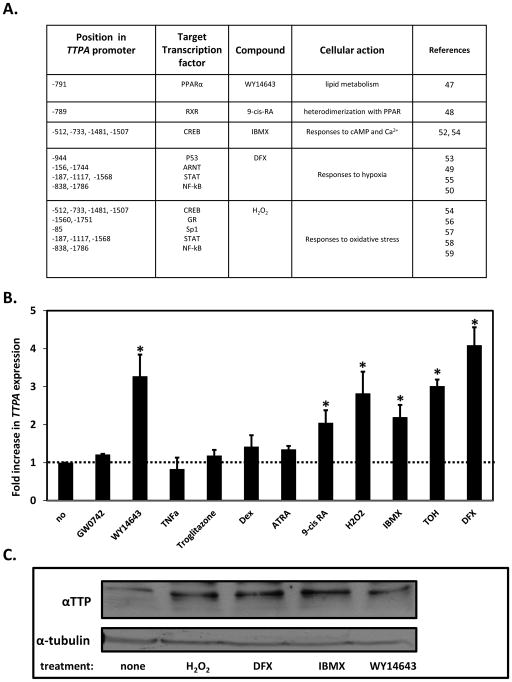

To begin to examine the mechanisms by which the expression of TTPA is regulated, a computational sequence algorithm (MatInspector; (44)) was employed to identify putative transcription factor binding sites in the proximal promoter region of the human TTPA gene. Figure 2A depicts the location of the putative response elements in the TTPA promoter, transcription factors known to associate with these elements, and ligands and compounds that are known to activate these factors (47–59). Immortalized human hepatocytes (IHH) cells were used to investigate the transcriptional responses of TTPA to these compounds using real-time RT-PCR to measure the expression level of the TTPA mRNA. As shown in Figure 2B, treatment of IHH cells with the RXR agonist 9-cis RA or with the synthetic PPARα-selective ligand WY14643 increased the level of TTPA mRNA by approximately 2- and 3-folds, respectively. These findings indicate that PPARα and RXR control TTPA expression, perhaps through their mutual heterodimerization (60). The phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX), which raises intracellular cAMP levels, also upregulated the expression levels of TTPA, suggesting that the cAMP response element-binding transcription factor CREB (61) regulates TTPA transcription.

Figure 2. Modulators of TTPA transcription.

A. Locations of putative transcription factors in the proximal human TTPA promoter were identified using sequence homology algorithms and are listed with their activator and physiological context. B. Real-time PCR results of TTPA expression. IHH cells were treated with 1 μM GW0742, 1 μM Wy14643, 1 μM TNFα, 1 μM Troglitazone, 1 μM ATRA (all trans retinoic acid) or 1 μM 9-cis RA (9-cis retinoic acid) for 4 hours; 200 μM H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) for 3 hours; 0.5 mM IBMX (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine) for 24 hours; 100 μM TOH (d-α-tocopherol) or 1 μM Dex (Dexamethasone) for 16 hours; or 200 μM DFX (desferrioxaminemesylate) for 24 hours prior to RNA isolation. Shown are averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance at p<0.05 compared to the untreated cells, determined by a Student’s T-test. C. αTTP protein expression. IHH cells were treated with 200 μM H2O2 for 3 hours or 0.5 mM IBMX, 1 μM Wy14643, 200 μM DFX for 24 hours prior to protein extraction and SDS-PAGE. Three hundred μg of lysate protein were immunoblotted against αTTP and tubulin.

In line with the reports that the only known high-affinity ligand of αTTP, α-tocopherol, affects TTPA levels [16, 18], treatment with vitamin E caused a marked increase in the level of TTPA mRNA (3-fold; Figure 2B). Additionally, the expression of TTPA mRNA increased in response to two potent inducers of oxidative stress, H2O2 (ca. 3-fold) and the hypoxia mimetic deferoxamine (DFX; 4-fold; Figure 2B). Expression levels of the αTTP protein also increased in response to these treatments, evidenced from immunoblotting the various lysates using anti-αTTP antibodies (Figure 2C).

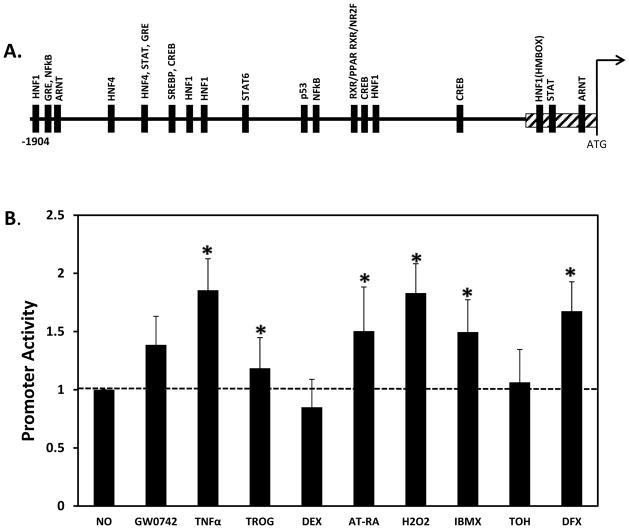

Transcriptional regulators of the proximal TTPA promoter

To address the molecular mechanisms by which the TTPA gene responds to the various inducers, we cloned the proximal human TTPA promoter (1.9 Kb upstream of the translation start site) into the pGL3-Basic vector, where it drives expression of the luciferase reporter gene (Figure 3A). IHH cells transfected with this construct were treated as in Figure 2, and promoter activity was determined as described in Methods (Figure 3B). Similar to our observations with the endogenous promoter (Figure 2B), H2O2, DFX and IBMX significantly stimulated the transcriptional activity of the isolated promoter. Interestingly, we found that inflammatory mediator TNFα also enhanced promoter activity. However, treatment with α-tocopherol, which activated transcription of endogenous TTPA mRNA, had no significant effect on transactivation of the cloned TTPA promoter. This observation suggests that a transcriptional element(s) mediating responsiveness to vitamin E reside outside the 1.9 Kb promoter region we cloned. Taken together, these results implicate the transcription factors CREB, NF-κB, Sp1, GR and STAT, as candidate mediators of the transcriptional response of the TTPA gene.

Figure 3. Transcriptional responses of the cloned TTPA promoter.

A. Locations of putative transcription factor binding sites in the proximal human TTPA promoter were identified using sequence homology algorithm (MatInspector; TransFac). Transcription factor binding sites are shown as solid boxes. A proximal GC-rich region is shown as a gray-hatched box. B. A luciferase reporter construct driven by the cloned human TTPA promoter (1904 bp) was co-transfected with β-galactosidase into IHH cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 200 μM H2O2 for 3 hours or 1 μM GW0742, 1 μM Wy14643, 1 μM TNFα, 1 μM Troglitazone, 1 μM ATRA (all trans retinoic acid) or 1 μM 9-cis RA (9-cis retinoic acid), 0.5 mM IBMX (3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine), 100 μM TOH (d-α-tocopherol), 1 μM Dex (Dexamethasone) or 200 μM DFX (desferrioxaminemesylate) for 24 hours prior to harvest. Shown are average values from three independent transfections, after normalization to the untreated condition. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of p<0.05 compared to the untreated -1904 construct, as determined from a Student’s T-test.

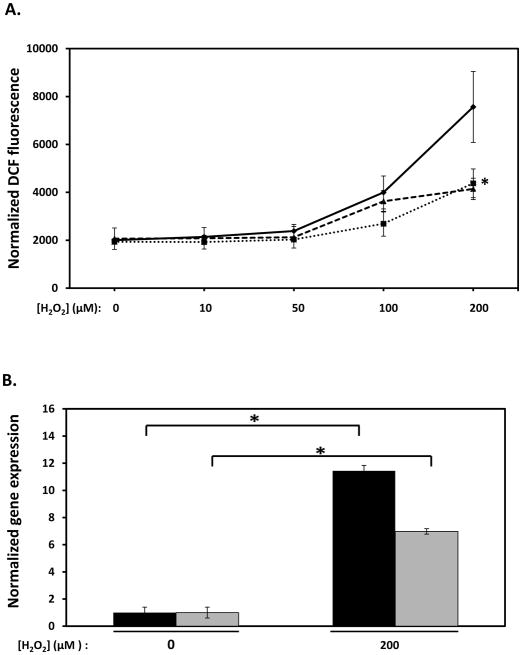

Oxidative stress directly stimulates transcription of the TTPA gene

Upregulation of TTPA expression by H2O2 (Figure 2B) may represent an important physiological feedback mechanism in which αTTP levels increase in response to oxidative stress, resulting in distribution of vitamin E to prevent further oxidative damage. We examined the effect of vitamin E on H2O2-induced oxidative stress using DCF-DA, a cell-permeable oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye widely used as an indicator of intracellular reactive oxygen species levels (62). As anticipated, treatment of IHH cells with hydrogen peroxide yielded a dose-responsive increase in dye fluorescence (Figure 4A). Pretreatment of the cells with vitamin E (100 μM α-tocopherol) or with the water-soluble antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (1 mM, (63)) markedly inhibited the H2O2-induced increase in DCF fluorescence (Figure 4A), confirming the established antioxidant action of these molecules. Finally, H2O2 treatment markedly increased expression of the oxidative stress-responsive gene metallothionein-1A (MT1A; (64)), concomitant with increased TTPA mRNA (Figure 4B). These data verify that treatment with H2O2 caused marked elevation of intracellular oxidative stress in IHH cells, and that the endogenous TTPA promoter is activated by this stimulus.

Figure 4. Transcriptional response of the αTTP gene to oxidative stress.

A. Measurement of hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress. The DCF-DA assay was used to measure intracellular reactive oxygen species as described in Methods. IHH cells were treated with 100 μM tocopherol (dotted line) or 1 mM N-acetyl cysteine (dashed line), or vehicle control (solid line) for 16 hours prior to challenge with 200 μM H2O2 for a 3 hours. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of p<0.05 versus vehicle-treated samples, determined by a Student’s T-test. B. mRNA levels of the MT1A (black bars) and TTPA (gray bars) genes was measured by real-time RT-PCR in cells treated as with 200 μM hydrogen peroxide (or with control vehicle) for 3 hours. Asterisks indicate statistical significance at p<0.05, determined from a Student’s T-test.

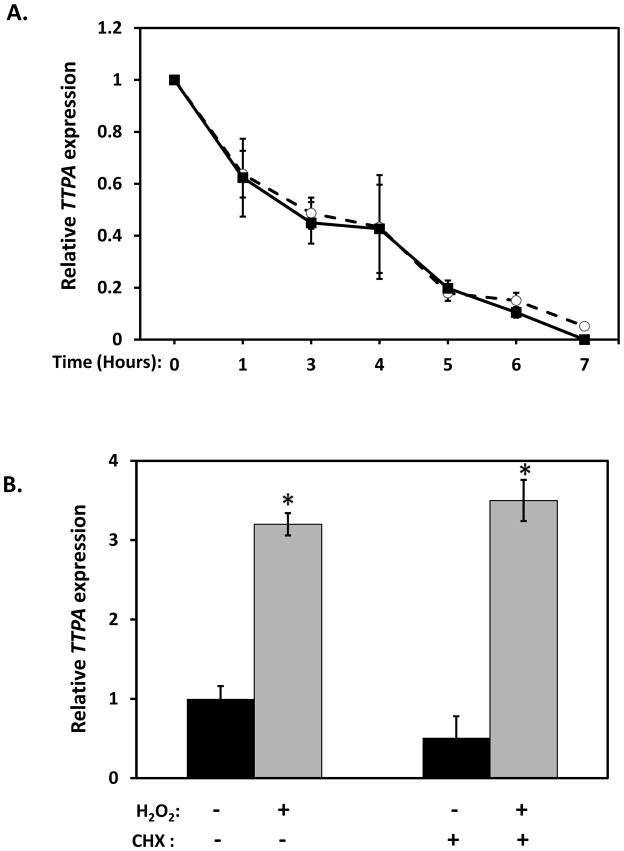

In principle, the H2O2-induced increase in TTPA mRNA could result from enhanced transcription of the gene, or from stabilization of the TTPA transcript. To distinguish between these possibilities, cells were treated with the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D and the rate of degradation of TTPA mRNA was examined in the presence or absence of H2O2 (Figure 5A). The data showed that the half-life of the TTPA mRNA (approximately 3 hours) is not affected by treatment with hydrogen peroxide. We therefore conclude that oxidative stress-induced increase in TTPA transcript results from upregulation of gene transcription.

Figure 5. Effect of oxidative stress on TTPA mRNA expression.

A. mRNA stability. Real-time RT-PCR was used to quantitate TTPA mRNA after treatment with 10 μg/ml actinomycin D for the indicated duration in the presence (open circles) or absence (solid squares) of 200 μM H2O2. B. Requirement for de novo protein synthesis. Real-time RT-PCR was used to measure TTPA mRNA levels following treatment with 200 μM H2O2 (or vehicle) for three hours. Where indicated, cells were pre-treated with the protein synthesis inhibitor cyclohexamide (100 μg/ml) for 15 minutes prior to H2O2 challenge. Shown are averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of p<0.05 versus untreated samples, determined from a Student’s T-test.

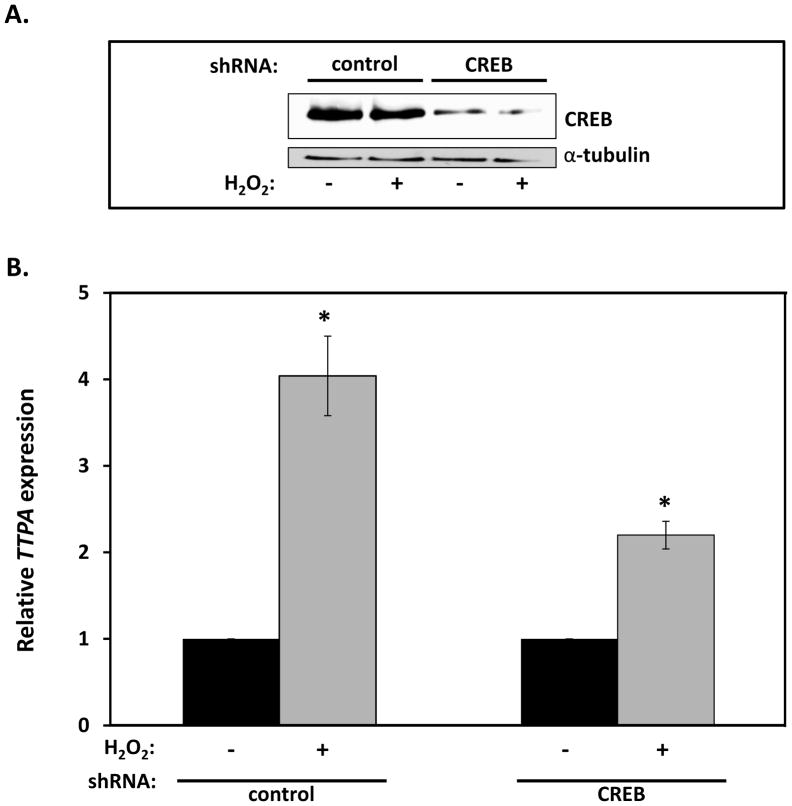

To examine whether the increase in TTPA mRNA reflects a direct nutrient-gene interaction or whether it is a secondary response that requires de novo protein synthesis, we examined the effect of the translational inhibitor cyclohexamide (65) on H2O2-stimulated transcription of TTPA. As shown in Figure 5B, pretreatment of IHH cells with cyclohexamide did not alter the transcriptional response of TTPA to hydrogen peroxide, indicating that TTPA expression is regulated by already-present transcription factor(s) which respond to oxidative stress. In light of two putative NF-κB binding sites in the TTPA promoter (Figure 3A), and the established oxidative stress-responsiveness of this transcription factor (66), we examined the possible involvement of NF-κB in the transcriptional response of TTPA to H2O2. Treatment of IHH cells with the NF-κB inhibitor Bay 11-7085 (67,68) did not abrogate the transcriptional response of TTPA expression to oxidative stress (data not shown), indicating that a transcription factor other than NF-κB mediates this response. To further interrogate the elements in the promoter region that may be responsible for the oxidative stress-induced TTPA transcriptional response we investigated involvement of the cAMP response element-binding (CREB) transcription factor, which is known to mediate oxidative stress responses in αTTP-expressing tissues (liver and the central nervous system (69,70)). Specifically, we examined CREB’s role using lentivirus-mediated delivery of CREB shRNA in IHH cells prior to measuring the effect of H2O2 on TTPA mRNA. The targeted knockdown approach attenuated the expression of CREB significantly as demonstrated by anti-CREB immunoblotting (>40% decrease; Figure 6A). Strikingly, shRNA-mediated knockdown of CREB significantly attenuated the transcriptional response of TTPA to oxidative stress (approximately 2-fold reduction; Figure 6B). These results show that CREB is a key mediator of the transcriptional response of the TTPA promoter to oxidative insults.

Figure 6. CREB mediates transcriptional response of the TTPA gene to oxidative stress.

A. IHH cells were transduced with lentiviruses harboring shRNA directed at CREB (or control shRNA) for 48 hours. Where indicated, transduced cells were treated with 200 μM H2O2 for 3 hours prior to lysis and immunobloting. Densitometric analysis revealed shRNA-mediated knockdown efficiency >40%. B. IHH cells were transduced with lentiviruses as in panel (A) and Real-time RT-PCR used to measure TTPA mRNA levels. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of p<0.05 compared to untreated samples, determined from a Student’s T-test.

Effects of common promoter single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on transcription of TTPA gene

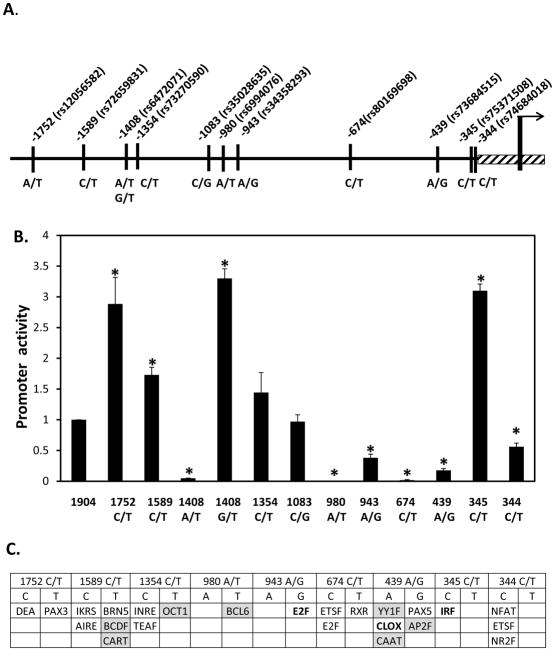

Examination of the NCBI database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp) revealed the presence of 37 SNPs in the 2 Kb region upstream of the TTPA’s initiating ATG codon. We focused on the 12 variants that have been validated by multiple independent studies and were found to occur in a significant fraction of healthy human populations (penetrance between 1 and 50%; Table 1). Using site-directed mutagenesis, we introduced these SNPs into the luciferase reporter construct that harbors the TTPA promoter, and measured their effects on promoter activity. We found that the various SNPs had profound impact on the transcriptional activity of the TTPA promoter (Figure 7B). Thus, the -1752C/T, -1408G/T, and -345C/T substitutions resulted in a ca. 3-fold increase in promoter activity compared to the ‘parental’ construct. In contrast, the -1408A/T, -980A/T, -943A/G, -674C/T, -439A/G and -344 C/T SNPs significantly repressed promoter activity. These alterations in transcriptional activities may reflect changes in the specific transcription factors that bind to the different TTPA promoter variants (Figure 7C). These results indicate that common SNPs in the TTPA promoter greatly affect the expression levels of αTTP, and thereby may critically alter circulating levels of vitamin E. In support of this notion, it has been previously reported that the -980A/T TTPA variant, which in our hands greatly suppressed promoter activity, is associated with reduced plasma vitamin E levels (71).

Table 1.

Characteristics of validated SNPs located in the TTPA promoter (proximal 1.9 KB).

| rs# | SNP location | Population | Study | Sample Count | Penetrance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % major allele | % minor allele | |||||

| rs73684515 | -439 A/G | Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 59 | A=10.2 | G=89.8 |

| rs80169698 | -674 C/T | Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 59 | C=94.9 | T=5.1 |

| rs34358293 | -944 A/G | Caucasian | SNP500Cancer | 30 | ||

| African/African American | SNP500Cancer | 24 | ||||

| Hispanic | SNP500Cancer | 23 | ||||

| Pacific Rim | SNP500Cancer | 24 | A=2.1 | G=97.9 | ||

| rs6994076 | -980 A/T | Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry | HapMap | 113 | A=52.2 | T=47.8 |

| Han Chinese in Beijing, China | HapMap | 45 | A=24.4 | T=75.6 | ||

| Japanese in Tokyo, Japan | HapMap | 86 | A=29.7 | T=70.3 | ||

| Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria, Sub-Saharan | HapMap | 113 | A=27.0 | T=73.0 | ||

| African ancestry in Southwest USA | HapMap | 49 | A=36.7 | T=63.3 | ||

| Caucasian | SNP500Cancer | 30 | A=50.0 | T=50.0 | ||

| African/African American | SNP500Cancer | 24 | A=29.2 | T=70.8 | ||

| Hispanic | SNP500Cancer | 23 | A=34.8 | T=65.2 | ||

| Pacific Rim | SNP500Cancer | 24 | A=26.1 | T=73.9 | ||

| rs73270590 | -1356 C/T | Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 59 | A=12.7 | T=87.3 |

| rs6472071 | -1409 A/G/T | Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 60 | A=44.2 | T=55.8 |

| Han Chinese in Beijing, China + Japanese in Tokyo, Japan | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 60 | A=40.0 | T=60.0 | ||

| Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | HapMap | 60 | A=47.5 | T=52.5 | ||

| rs35028635 | -1083 C/G | Yoruba in Ibadan, Nigeria | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 59 | C=11.9 | G=88.1 |

| Caucasian | SNP500Cancer | 30 | C=0 | G=100 | ||

| African/African American | SNP500Cancer | 24 | C=2.1 | G=97.9 | ||

| Hispanic | SNP500Cancer | 23 | C=0 | G=100 | ||

| Pacific Rim | SNP500Cancer | 24 | C=0 | G=100 | ||

| rs12056582 | -1752 C/T | Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 60 | C=95.8 | T=4.2 |

| Han Chinese in Beijing, China + Japanese in Tokyo, Japan | 1000Genomes pilot low-coverage panel | 60 | C=64.2 | T=35.8 | ||

Figure 7. Effect of common SNPs on the transcriptional activity of the TTPA promoter.

A. Schematic depiction of the 1.9 Kb proximal TTPA promoter, showing position and reference ID (rs#) of validated single nucleotide polymorphisms. B. Transcriptional activities of SNP-mutated TTPA promoter. SNPs were introduced into the wild-type (1904 bp) TTPA promoter in the luciferase reporter construct, and luciferase activities measured as described in Methods. A promoter-less pGL3B vector served as a background control. Shown are the averages and standard deviations of three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance of p<0.05, compared to the wild-type promoter construct, as determined by Student’s T-test. C. Transcription factor binding sites that may be altered by SNPs in the proximal TTPA promoter. Repressors are shown in shaded boxes and activators in bold typeface.

DISCUSSION

αTTP is the only known direct regulator of whole-body vitamin E status, yet the mechanisms that regulate its expression are by and large unknown. Our results reveal that expression of the TTPA gene is induced by WY14643 and 9-cis-retinoic acid, ligands that activate the nuclear receptors PPARα and RXR, respectively. Together with the identification of a putative PPAR response element in the TTPA promoter, these data suggest that TTPA transcription is regulated by PPARα-RXR heterodimers (72). The involvement of these heterodimers in specifically regulating TTPA expression and its physiological consequences remain to be clarified.

Of critical importance are our findings showing that oxidative stress enhances expression levels of the αTTP mRNA and protein in cells (Figures 2B and 5B), and increases the transcriptional activity of the isolated TTPA promoter (Figure 3B). Since oxidative stress did not influence the stability of the TTPA mRNA (Figure 5A) and since stimulation of TTPA transcription by peroxide did not require de novo protein synthesis (Figure 5B), we conclude that oxidative stress-induced enhancement of TTPA expression is mediated by an already-present oxidative stress-responsive transcription factor. The lack of inhibition by the NF-κB antagonist Bay 11-7085 suggests that the transcription factor responsible for this effect is not NF-κB. Possibly, other oxidative stress-responsive transcription factors such as SP1, STAT and GR, in addition to CREB (see below) mediate the transcriptional responses of TTPA to oxidative stress.

The data show that TTPA expression was induced upon treatment with the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX, which elevates intra-cellular levels of cAMP (Figure 2B). Moreover, silencing CREB expression with a specific shRNA abrogated the transcriptional response of TTPA to oxidative stress (Figure 6B). These data demonstrate that CREB plays an important role in mediating the effects of oxidative stress onto the TTPA promoter. Further support to this conclusion is found by the presence of multiple CREB binding sites in the TTPA promoter (Figure 3A), and by published reports of the effect of vitamin E on the expression levels (73) or phosphorylation status (74) of CREB. Future studies will delineate the specific CREB binding site in the TTPA promoter that mediates this transcriptional response.

Do the transcriptional responses of the TTPA gene to oxidative stress represent a feedback regulatory mechanism, in which increased αTTP levels increase antioxidant bioavailability? Bella et al reported that hepatic αTTP levels in mice do not change upon exposure to oxidative stress in the form of environmental tobacco smoke (32). However, we note that αTTP is also expressed in the brain (26) and placenta (27), where it is thought to regulate localized vitamin E status. It is possible that oxidative-stress responses of the TTPA gene are more relevant in these tissues, where αTTP levels are significantly lower than in the liver.

A puzzling enigma in present-day vitamin E research is an apparent contradiction between the beneficial effects of α-tocopherol supplementation observed in laboratory animals, and the lack of consistent efficacy in controlled clinical trials. For example, vitamin E exhibits remarkable anti-proliferative effects in cell culture models of prostate cancer (25,75–78). Moreover, supplementation with α-tocopherol is highly effective in reducing prostate tumor load in rodent models of the disease (79–81). Nevertheless, clinical trials in human population proved inconsistent at best: both the Alpha Tocopherol Beta Carotene cancer prevention study (ATBC; (82)), and Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial (CARET; (83)) demonstrated protective effects for vitamin E against prostate cancer. On the other hand, the randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial SELECT showed that vitamin E supplementation increased prostate cancer risk (84). Our data show that commonly occurring SNPs have profound impact on the transcriptional activity of the TTPA promoter (Figure 7B). On the molecular level, these functional outcomes of the SNPs likely reflect alterations in transcription factor binding, such as the new putative binding site for the transcriptional inhibitor BCL6 that is generated by the -980 A/T polymorphism (Figure 7C). It is tempting to speculate that such polymorphic variations manifest in variable baseline vitamin E levels among individuals, and in heterogeneous response to supplementation. Indeed, Kelly and colleagues demonstrated that circulating vitamin E levels in healthy humans is a genetically determined trait that is subject to great inter-individual variations (85,86). Furthermore, one common promoter variant (rs6994076) was reported to associate with reduced plasma vitamin E levels in healthy humans (71). Determinations of TTPA genotype in samples from clinical intervention trials stand to provide conclusive testing of this hypothesis.

Highlights.

Vitamin E is the major lipid-soluble antioxidant

αTTP is the only known regulator of vitamin E status

Oxidative stress and promoter SNPs regulate expression of the TTPA gene

Our findings may explain perplexing results regarding responses to vitamin E supplementation observed in clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH award DK067494 to DM, and by a pilot award from the Case Comprehensive Cancer Center Support Grant 5P30-CA043703 from the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Burton GW, Cheeseman KH, Doba T, Ingold KU, Slater TF. Vitamin E as an antioxidant in vitro and in vivo. Ciba Found Symp. 1983;101:4–18. doi: 10.1002/9780470720820.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burton GW, Joyce A, Ingold KU. First proof that vitamin E is major lipid-soluble, chain-breaking antioxidant in human blood plasma. Lancet. 1982;2:327. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)90293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burton GW, Traber MG. Vitamin E: antioxidant activity, biokinetics, and bioavailability. Annu Rev Nutr. 1990;10:357–382. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.10.070190.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingold KU, Webb AC, Witter D, Burton GW, Metcalfe TA, Muller DP. Vitamin E remains the major lipid-soluble, chain-breaking antioxidant in human plasma even in individuals suffering severe vitamin E deficiency. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1987;259:224–225. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Freeman LR, Keller JN. Oxidative stress and cerebral endothelial cells: Regulation of the blood-brain-barrier and antioxidant based interventions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Droge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baynes JW. Role of oxidative stress in development of complications in diabetes. Diabetes. 1991;40:405–412. doi: 10.2337/diab.40.4.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolff SP. Diabetes mellitus and free radicals. Free radicals, transition metals and oxidative stress in the aetiology of diabetes mellitus and complications. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:642–652. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alexander RW. Theodore Cooper Memorial Lecture. Hypertension and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Oxidative stress and the mediation of arterial inflammatory response: a new perspective. Hypertension. 1995;25:155–161. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halliwell B. Oxidants and the central nervous system: some fundamental questions. Is oxidant damage relevant to Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic injury or stroke? Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1989;126:23–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1989.tb01779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratico D, VMYL, Trojanowski JQ, Rokach J, Fitzgerald GA. Increased F2-isoprostanes in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for enhanced lipid peroxidation in vivo. FASEB J. 1998;12:1777–1783. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.15.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pratico D, Tangirala RK, Rader DJ, Rokach J, FitzGerald GA. Vitamin E suppresses isoprostane generation in vivo and reduces atherosclerosis in ApoE-deficient mice. Nat Med. 1998;4:1189–1192. doi: 10.1038/2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lovell MA, Ehmann WD, Mattson MP, Markesbery WR. Elevated 4-hydroxynonenal in ventricular fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:457–461. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(97)00108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traber MG, Atkinson J. Vitamin E, antioxidant and nothing more. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azzi A. Molecular mechanism of alpha-tocopherol action. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Traber MG, Arai H. Molecular mechanisms of vitamin E transport. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19:343–355. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manor D, Morley S. The alpha-tocopherol transfer protein. Vitam Horm. 2007;76:45–65. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(07)76003-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavalier L, Ouahchi K, Kayden HJ, Di Donato S, Reutenauer L, Mandel JL, Koenig M. Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency: heterogeneity of mutations and phenotypic variability in a large number of families. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:301–310. doi: 10.1086/301699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouahchi K, Arita M, Kayden H, Hentati F, Ben Hamida M, Sokol R, Arai H, Inoue K, Mandel JL, Koenig M. Ataxia with isolated vitamin E deficiency is caused by mutations in the alpha-tocopherol transfer protein. Nat Genet. 1995;9:141–145. doi: 10.1038/ng0295-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terasawa Y, Ladha Z, Leonard SW, Morrow JD, Newland D, Sanan D, Packer L, Traber MG, Farese RV., Jr Increased atherosclerosis in hyperlipidemic mice deficient in alpha - tocopherol transfer protein and vitamin E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13830–13834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240462697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokota T, Igarashi K, Uchihara T, Jishage K, Tomita H, Inaba A, Li Y, Arita M, Suzuki H, Mizusawa H, Arai H. Delayed-onset ataxia in mice lacking alpha-tocopherol transfer protein: model for neuronal degeneration caused by chronic oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15185–15190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261456098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshida Y, Itoh N, Hayakawa M, Piga R, Cynshi O, Jishage K, Niki E. Lipid peroxidation induced by carbon tetrachloride and its inhibition by antioxidant as evaluated by an oxidative stress marker, HODE. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;208:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaoka S, Kim HS, Ogihara T, Oue S, Takitani K, Yoshida Y, Tamai H. Severe Vitamin E deficiency exacerbates acute hyperoxic lung injury associated with increased oxidative stress and inflammation. Free Radic Res. 2008;42:602–612. doi: 10.1080/10715760802189864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jishage K, Arita M, Igarashi K, Iwata T, Watanabe M, Ogawa M, Ueda O, Kamada N, Inoue K, Arai H, Suzuki H. Alpha-tocopherol transfer protein is important for the normal development of placental labyrinthine trophoblasts in mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1669–1672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morley S, Thakur V, Danielpour D, Parker R, Arai H, Atkinson J, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Klein E, Manor D. Tocopherol transfer protein sensitizes prostate cancer cells to vitamin E. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:35578–35589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.169664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosomi A, Goto K, Kondo H, Iwatsubo T, Yokota T, Ogawa M, Arita M, Aoki J, Arai H, Inoue K. Localization of alpha-tocopherol transfer protein in rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1998;256:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00785-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaempf-Rotzoll DE, Horiguchi M, Hashiguchi K, Aoki J, Tamai H, Linderkamp O, Arai H. Human Placental Trophoblast Cells Express alpha-Tocopherol Transfer Protein. Placenta. 2003;24:439–444. doi: 10.1053/plac.2002.0966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller-Schmehl K, Beninde J, Finckh B, Florian S, Dudenhausen JW, Brigelius-Flohe R, Schuelke M. Localization of alpha-tocopherol transfer protein in trophoblast, fetal capillaries’ endothelium and amnion epithelium of human term placenta. Free Radic Res. 2004;38:413–420. doi: 10.1080/10715760310001659611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotzoll DE, Scherling R, Etzl R, Stepan H, Horn LC, Poschl JM. Immunohistochemical localization of alpha-tocopherol transfer protein and lipoperoxidation products in human first-trimester and term placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Shaw HM, Huang C. Liver alpha-tocopherol transfer protein and its mRNA are differentially altered by dietary vitamin E deficiency and protein insufficiency in rats. J Nutr. 1998;128:2348–2354. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.12.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thakur V, Morley S, Manor D. Hepatic alpha-tocopherol transfer protein: ligand-induced protection from proteasomal degradation. Biochemistry. 2010;49:9339–9344. doi: 10.1021/bi100960b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bella DL, Schock BC, Lim Y, Leonard SW, Berry C, Cross CE, Traber MG. Regulation of the alpha-tocopherol transfer protein in mice: lack of response to dietary vitamin E or oxidative stress. Lipids. 2006;41:105–112. doi: 10.1007/s11745-006-5077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim HS, Arai H, Arita M, Sato Y, Ogihara T, Inoue K, Mino M, Tamai H. Effect of alpha-tocopherol status on alpha-tocopherol transfer protein expression and its messenger RNA level in rat liver. Free Radic Res. 1998;28:87–92. doi: 10.3109/10715769809097879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chao PM, Chen WH, Liao CH, Shaw HM. Conjugated linoleic acid causes a marked increase in liver alpha-tocopherol and liver alpha-tocopherol transfer protein in C57BL/6 J mice. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 2010;80:65–73. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fechner H, Schlame M, Guthmann F, Stevens PA, Rustow B. alpha- and delta-tocopherol induce expression of hepatic alpha-tocopherol-transfer-protein mRNA. Biochem J. 1998;331 (Pt 2):577–581. doi: 10.1042/bj3310577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen WH, Li YJ, Wang MS, Kang ZC, Huang HL, Shaw HM. Elevation of tissue alpha-tocopherol levels by conjugated linoleic acid in C57BL/6J mice is not associated with changes in vitamin E absorption or alpha-carboxyethyl hydroxychroman production. Nutrition. 2012;28:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ban R, Takitani K, Kim HS, Murata T, Morinobu T, Ogihara T, Tamai H. alpha-Tocopherol transfer protein expression in rat liver exposed to hyperoxia. Free Radic Res. 2002;36:933–938. doi: 10.1080/107156021000006644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Usenko CY, Harper SL, Tanguay RL. Fullerene C60 exposure elicits an oxidative stress response in embryonic zebrafish. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;229:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2007.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Etzl RP, Vrekoussis T, Kuhn C, Schulze S, Poschl JM, Makrigiannakis A, Jeschke U, Rotzoll DE. Oxidative stress stimulates alpha-tocopherol transfer protein in human trophoblast tumor cells BeWo. J Perinat Med. 2012;40:373–378. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2011-0307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ray RB, Meyer K, Ray R. Hepatitis C virus core protein promotes immortalization of primary human hepatocytes. Virology. 2000;271:197–204. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rius J, Guma M, Schachtrup C, Akassoglou K, Zinkernagel AS, Nizet V, Johnson RS, Haddad GG, Karin M. NF-kappaB links innate immunity to the hypoxic response through transcriptional regulation of HIF-1alpha. Nature. 2008;453:807–811. doi: 10.1038/nature06905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cowell JK, Franks LM. A rapid method for accurate DNA measurements in single cells in situ using a simple microfluorimeter and Hoechst 33258 as a quantitative fluorochrome. J Histochem Cytochem. 1980;28:206–210. doi: 10.1177/28.3.6153398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quandt K, Frech K, Karas H, Wingender E, Werner T. MatInd and MatInspector: new fast and versatile tools for detection of consensus matches in nucleotide sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:4878–4884. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.23.4878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arita M, Sato Y, Miyata A, Tanabe T, Takahashi E, Kayden HJ, Arai H, Inoue K. Human alpha-tocopherol transfer protein: cDNA cloning, expression and chromosomal localization. Biochem J. 1995;306 (Pt 2):437–443. doi: 10.1042/bj3060437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dreyer C, Keller H, Mahfoudi A, Laudet V, Krey G, Wahli W. Positive regulation of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway by fatty acids through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) Biol Cell. 1993;77:67–76. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(05)80176-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mangelsdorf DJ, Evans RM. The RXR heterodimers and orphan receptors. Cell. 1995;83:841–850. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang GL, Jiang BH, Semenza GL. Effect of altered redox states on expression and DNA-binding activity of hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;212:550–556. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chandel NS, Trzyna WC, McClintock DS, Schumacker PT. Role of oxidants in NF-kappa B activation and TNF-alpha gene transcription induced by hypoxia and endotoxin. J Immunol. 2000;165:1013–1021. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vo N, Goodman RH. CREB-binding protein and p300 in transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13505–13508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Achison M, Hupp TR. Hypoxia attenuates the p53 response to cellular damage. Oncogene. 2003;22:3431–3440. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bedogni B, Pani G, Colavitti R, Riccio A, Borrello S, Murphy M, Smith R, Eboli ML, Galeotti T. Redox regulation of cAMP-responsive element-binding protein and induction of manganous superoxide dismutase in nerve growth factor-dependent cell survival. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16510–16519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Joung YH, Park JH, Park T, Lee CS, Kim OH, Ye SK, Yang UM, Lee KJ, Yang YM. Hypoxia activates signal transducers and activators of transcription 5 (STAT5) and increases its binding activity to the GAS element in mammary epithelial cells. Exp Mol Med. 2003;35:350–357. doi: 10.1038/emm.2003.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adcock IM, Ito K, Barnes PJ. Glucocorticoids: effects on gene transcription. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2004;1:247–254. doi: 10.1513/pats.200402-001MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ryu H, Lee J, Zaman K, Kubilis J, Ferrante RJ, Ross BD, Neve R, Ratan RR. Sp1 and Sp3 are oxidative stress-inducible, antideath transcription factors in cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3597–3606. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03597.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carballo M, Conde M, El Bekay R, Martin-Nieto J, Camacho MJ, Monteseirin J, Conde J, Bedoya FJ, Sobrino F. Oxidative stress triggers STAT3 tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation in human lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17580–17586. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schreck R, Rieber P, Baeuerle PA. Reactive oxygen intermediates as apparently widely used messengers in the activation of the NF-kappa B transcription factor and HIV-1. EMBO J. 1991;10:2247–2258. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rakhshandehroo M, Knoch B, Muller M, Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. PPAR Res. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/612089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lugnier C. Cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase (PDE) superfamily: a new target for the development of specific therapeutic agents. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;109:366–398. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang H, Joseph JA. Quantifying cellular oxidative stress by dichlorofluorescein assay using microplate reader. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;27:612–616. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen J, Wanming D, Zhang D, Liu Q, Kang J. Water-soluble antioxidants improve the antioxidant and anticancer activity of low concentrations of curcumin in human leukemia cells. Die Pharmazie. 2005;60:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dalton T, Palmiter RD, Andrews GK. Transcriptional induction of the mouse metallothionein-I gene in hydrogen peroxide-treated Hepa cells involves a composite major late transcription factor/antioxidant response element and metal response promoter elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5016–5023. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.23.5016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abou Elela S, Nazar RN. The ribosomal 5.8S RNA as a target site for p53 protein in cell differentiation and oncogenesis. Cancer Lett. 1997;117:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jones JC, Gonzalez LM, Larson MM, Freeman LE, Werre SR. Feasibility and accuracy of ultrasound-guided sacroiliac joint injection in dogs. Veterinary radiology & ultrasound: the official journal of the American College of Veterinary Radiology and the International Veterinary Radiology Association. 2012;53:446–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8261.2011.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pierce JW, Schoenleber R, Jesmok G, Best J, Moore SA, Collins T, Gerritsen ME. Novel inhibitors of cytokine-induced IkappaBalpha phosphorylation and endothelial cell adhesion molecule expression show anti-inflammatory effects in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21096–21103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.34.21096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koedel U, Bayerlein I, Paul R, Sporer B, Pfister HW. Pharmacologic interference with NF-kappaB activation attenuates central nervous system complications in experimental Pneumococcal meningitis. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1437–1445. doi: 10.1086/315877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee B, Cao R, Choi YS, Cho HY, Rhee AD, Hah CK, Hoyt KR, Obrietan K. The CREB/CRE transcriptional pathway: protection against oxidative stress-mediated neuronal cell death. J Neurochem. 2009;108:1251–1265. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kumashiro N, Tamura Y, Uchida T, Ogihara T, Fujitani Y, Hirose T, Mochizuki H, Kawamori R, Watada H. Impact of oxidative stress and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha in hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2008;57:2083–2091. doi: 10.2337/db08-0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wright ME, Peters U, Gunter MJ, Moore SC, Lawson KA, Yeager M, Weinstein SJ, Snyder K, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Association of variants in two vitamin e transport genes with circulating vitamin e concentrations and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1429–1438. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kliewer SA, Umesono K, Noonan DJ, Heyman RA, Evans RM. Convergence of 9-cis retinoic acid and peroxisome proliferator signalling pathways through heterodimer formation of their receptors. Nature. 1992;358:771–774. doi: 10.1038/358771a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aiguo W, Zhe Y, Gomez-Pinilla F. Vitamin E protects against oxidative damage and learning disability after mild traumatic brain injury in rats. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2010;24:290–298. doi: 10.1177/1545968309348318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hernandez-Pinto AM, Puebla-Jimenez L, Arilla-Ferreiro E. alpha-Tocopherol decreases the somatostatin receptor-effector system and increases the cyclic AMP/cyclic AMP response element binding protein pathway in the rat dentate gyrus. Neuroscience. 2009;162:106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thompson IM, Basler J, Hensley D, von Merveldt D, Jenkins CA, Higgins B, Leach R, Troyer D, Pollock B. Prostate cancer prevention: what do we know now and when will we know more? Clin Prostate Cancer. 2003;1:215–220. doi: 10.3816/cgc.2003.n.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sigounas G, Anagnostou A, Steiner M. dl-alpha-tocopherol induces apoptosis in erythroleukemia, prostate, and breast cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 1997;28:30–35. doi: 10.1080/01635589709514549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gunawardena K, Murray DK, Meikle AW. Vitamin E and other antioxidants inhibit human prostate cancer cells through apoptosis. Prostate. 2000;44:287–295. doi: 10.1002/1097-0045(20000901)44:4<287::aid-pros5>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gunawardena K, Campbell LD, Meikle AW. Combination therapy with vitamins C plus E inhibits survivin and human prostate cancer cell growth. Prostate. 2004;59:319–327. doi: 10.1002/pros.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Venkateswaran V, Fleshner NE, Klotz LH. Synergistic effect of vitamin E and selenium in human prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2004;7:54–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Venkateswaran V, Klotz LH, Ramani M, Sugar LM, Jacob LE, Nam RK, Fleshner NE. A combination of micronutrients is beneficial in reducing the incidence of prostate cancer and increasing survival in the Lady transgenic model. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009;2:473–483. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Siler U, Barella L, Spitzer V, Schnorr J, Lein M, Goralczyk R, Wertz K. Lycopene and vitamin E interfere with autocrine/paracrine loops in the Dunning prostate cancer model. Faseb J. 2004;18:1019–1021. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1116fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weinstein SJ, Wright ME, Pietinen P, King I, Tan C, Taylor PR, Virtamo J, Albanes D. Serum alpha-tocopherol and gamma-tocopherol in relation to prostate cancer risk in a prospective study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:396–399. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Goodman GE, Schaffer S, Omenn GS, Chen C, King I. The association between lung and prostate cancer risk, and serum micronutrients: results and lessons learned from beta-carotene and retinol efficacy trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:518–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Klein EA, Thompson IM, Jr, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, Minasian LM, Ford LG, Parnes HL, Gaziano JM, Karp DD, Lieber MM, Walther PJ, Klotz L, Parsons JK, Chin JL, Darke AK, Lippman SM, Goodman GE, Meyskens FL, Jr, Baker LH. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) JAMA. 2011;306:1549–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kelly FJ, Lee R, Mudway IS. Inter- and intra-individual vitamin E uptake in healthy subjects is highly repeatable across a wide supplementation dose range. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1031:22–39. doi: 10.1196/annals.1331.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roxborough HE, Burton GW, Kelly FJ. Inter- and intra-individual variation in plasma and red blood cell vitamin E after supplementation. Free Radic Res. 2000;33:437–445. doi: 10.1080/10715760000300971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]