Abstract

Complementary and alternative medicine includes a number of exercise modalities, such as tai chi, qigong, yoga, and a variety of lesser-known movement therapies. A meta-analysis of the current literature was conducted estimating the effect size of the different modalities, study quality and bias, and adverse events. The level of research has been moderately weak to date, but most studies report a medium-to-high effect size in pain reduction. Given the lack of adverse events, there is little risk in recommending these modalities as a critical component in a multimodal treatment plan, which is often required for fibromyalgia management.

Keywords: fibromyalgia, exercise, complementary and alternative, efficacy, safety

Introduction

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a debilitating chronic pain condition affecting ~15 million persons in the USA and is one of the more severe disorders on the continuum of persistent pain.1–4 FM results in profound suffering, including widespread musculoskeletal pain and stiffness, fatigue, disturbed sleep, dyscognition, affective distress, and very poor quality of life.5,6 Among FM patients, 20%–50% work few or no days despite being in their peak wage-earning years.6,7 Disability payments are received by 26%–55% of FM patients compared with the national average of 2% of patients who receive disability payments from other causes.7–9 Furthermore, health care costs are three times higher among FM patients compared with matched controls.9

Diminished aerobic fitness in FM has been documented for almost three decades, and recent studies report that the average 40-year-old with FM has fitness findings expected for a healthy 70 to 80-year-old, and FM has now also been associated with increased mortality.2,3,11–14 Tailoring exercise to patients with FM requires an understanding of the relevant pathophysiology. FM is likely due in part to altered pain processing in the central and peripheral nervous system.15–17 Additional pathophysiologic factors include genetic predispositions, autonomic dysfunction, and emotional, physical, or environmental stressors.18 Neurohormonal and inflammatory dysfunctions are implicated in muscle microtrauma and ischemia, a potent pain generator during and after exercise.15,18–24 The majority of persons with FM have four or more comorbid pain or central sensitivity disorders, including irritable bowel/bladder, headaches, pelvic pain, regional musculoskeletal pain syndromes (such as low back pain), chronic fatigue, and restless leg syndromes, suggesting shared pain processing in these common comorbidities.25–27 Multiple symptoms and poor physical function are underpinned by physiologic abnormalities found in FM and other chronic pain conditions.

Drug therapies for FM offer some help, improving pain by ~30% and function by ~20%. Drug access and costs are challenging, however, as none are available in generic formulation. Further, they carry safety concerns and may produce side effects, such as nausea, edema, weight gain, or tachycardia.27–31 Unfortunately, no new FM drugs are in Phase III testing or under Food and Drug Administration (FDA) review, shifting the urgency to the development of novel, safe, effective nonpharmacological strategies, including exercise.32

Based on results of over 100 studies, exercise has been strongly recommended as an adjunct to drug therapy for FM.33–36 Of these studies, approximately 80% are aerobic or mixed-type (aerobic, strength, flexibility).37–44 New data have emerged since these key position statements were published. Namely, a meta-analysis of studies with low attrition concluded that immediately postintervention, high quality aerobic or mixed modality exercise reliably restored physical function or fitness (d = 0.65) and health-related quality of life (d = −0.40), while exerting no significant effects on sleep (d = 0.01). Effect sizes for pain were small (d = −0.31) and not sustained at follow up (d = 0.13).41 Similarly, 14 strength or stretching studies consistently demonstrated improvements in fatigue and physical function but inconsistently improved other FM symptoms.39,42 Studies included in the meta-analysis had a median attrition of 67% (range 27%–90%), suggesting that the interventions themselves were not acceptable. Some early programs dosed the intervention too high (exercise frequency, intensity, and timing) or required medication washout, leading to an attrition rate averaging approximately 40%. Others selected inappropriate exercise modalities, such as running, fast dancing, or high-intensity aerobics, resulting in 62%–67% attrition.45,46

In search of more comprehensive and continued symptom relief, FM patients have been increasingly adopting complementary and alternative exercise therapies, such as qigong, tai chi, yoga, and a variety of lesser-known movement therapies.47,48 Qigong and tai chi both have origins in the Chinese martial arts. They involve physical movement integrated with mental focus and deep breathing. They seek to cultivate and balance qi (chi), which is sometimes translated as “intrinsic life energy.” Yoga is “a union of mind and body” with origins in ancient Indian philosophy. In yoga, physical postures (“asanas”) are generally practiced in tandem with breathing techniques (“pranayama”) and meditation or relaxation.

Langhorst et al49 recently published a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on meditative movement in FM, concluding that these modalities were safe and effective for selected FM symptoms. The aim of this paper is to extend Langhorst’s work by providing a comprehensive review of a broader array of land-based complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) FM exercise studies, including early-stage research. For the purposes of this review, exercise is defined as planned, structured physical activity whose goal is to improve one or more of the major components of fitness – aerobic capacity, strength, flexibility, or balance. CAM is defined as “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered to be part of conventional medicine.”50

Material and methods

Literature search strategy

Electronic databases were screened during October 2012, including SciVerse Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PubMed/ Medline, Cochrane Library, and PsychInfo. The key medical subject heading (MeSH) terms for initial inclusion were “fibromyalgia” and “fibromyalgia syndrome” combined with “yoga,” “tai chi,” “pilates,” “taiji,” and “qigong.” To maximize the search results, no search limitations of language, year, or study design were implemented. Additional studies were identified through the bibliographies of selected studies and personal contact with researchers in the field.

Selection criteria

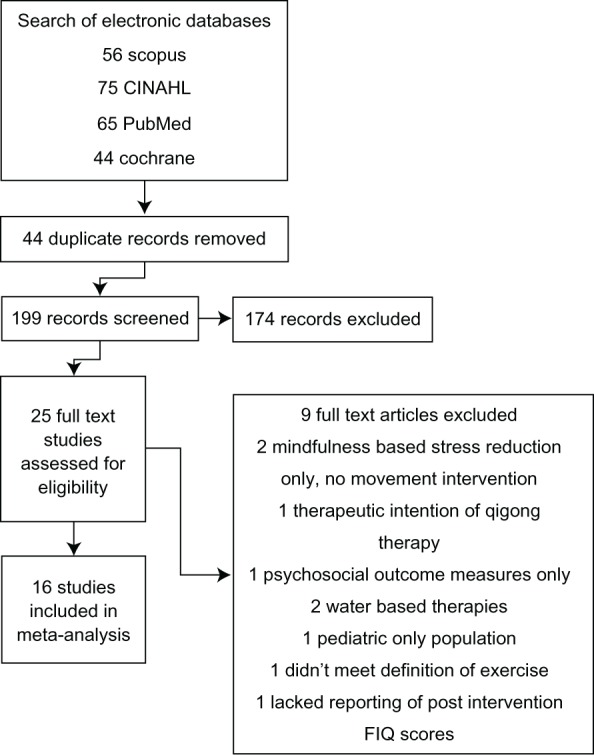

To determine their initial eligibility, all potential studies were retrieved in full text and reviewed for the inclusion criteria. All three authors independently screened all identified full-text articles, to determine whether the study met the inclusion criteria. To be included in this review, studies had to meet the following criteria: (1) enrollment of participants 21 years of age and older who met the standardized criteria for FM diagnosis, (2) study intervention met the definitions for CAM and land-based exercise, and (3) inclusion and reporting of pre- and post-Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) total score or numeric pain rating scale scores.51,52 This means that CAM studies with very low levels of exertion, such as studies of body awareness therapies, breathing studies, and mindfulness-based stress reduction (which generally offers very brief yoga in two out of eight sessions), were not included. Additionally, we excluded water-based CAM therapies, such as tai chi in water and yoga/breathing in water, as it is unclear whether the benefit derived from balneotherapeutic effects or physical movement and mindful techniques (Figure 1).53,54

Figure 1.

Search strategy results.

Abbreviations: CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; FIQ, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.

Data extraction

All review authors participated in data extraction. Data were extracted in the following content areas: study design, type of CAM exercise, sample size, subject characteristics (age and gender), treatment duration, frequency and dose, adherence to treatment, attrition rates, and outcome variables and results. Any discrepancies between authors were discussed and consensus obtained. When studies did not include enough information to calculate the effect size estimates on pain, the authors were contacted to request the data required for a complete statistical analysis. Most of these reported point estimates rather than effect sizes. All studies for which effect sizes could not be calculated, were excluded from this review.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was completed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis software, Version 2.2.064 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, USA). Standard formulas were used to calculate standardized mean differences and standard errors.55 Overall estimates of treatment effect used a random effects meta-analysis.56 Subgroup analyses were conducted with respect to treatment modality. A common among-study variance component across subgroups was not used when calculating the effect size of the individual modalities.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the selected studies was assessed using the Jadad score,57 assessing for randomization, blinding, and clear explanations for study dropouts. While Jadad scoring is intended for RCTs, the authors thought that it was a good, if simple, measure of methodological quality, allowing nonrandomized trials in this review the possibility of a score of 0 or 1 and RCTs a maximum score of 3. Normally the Jadad score has a range of 0 to 5, but as it is not possible to blind the interventionist to the treatment in CAM exercise, the maximum achievable score is 3. The average score for the studies in this review was 1.7 (range 1 to 3).

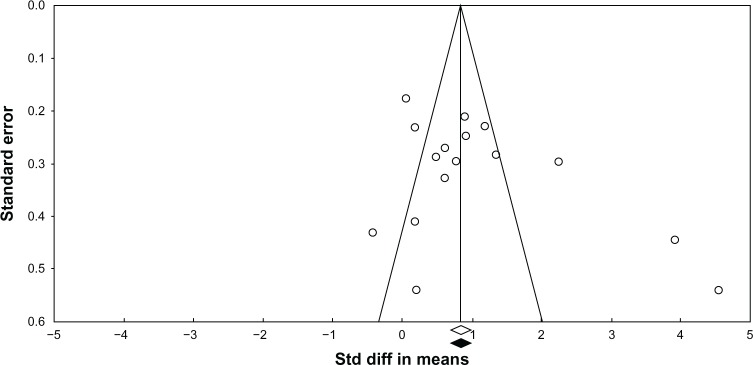

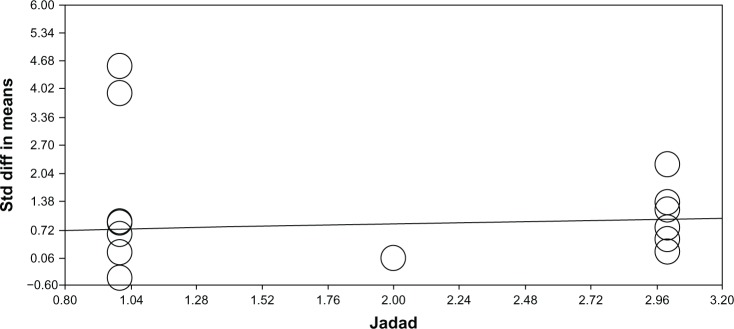

Sensitivity and validity analysis

A funnel plot was constructed of standard differences (Std diff) in means by standard errors, with two standard deviations displayed. A random distribution of studies indicated a low publication bias. A regression of the Jadad score on the Std diff in means was calculated. The slope is indicative of publication bias by quality of study. A slope of zero indicates that there was no bias.

Results

Study design

As the field has a relatively low number of reported RCTs, we included time-series trials. Due to this limitation, the relative study strength was moderately low. Time-series trials were adjusted for the relative overestimation of strength. However, one can see that the time series still represented some of the largest reported effects. Table 1 reports the details of each study.

Table 1.

Summary of included trials

| Author | Study type/design | Intervention and dose | Sample size, age and adverse events | Post intervention follow up | Outcome measures and timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qigong studies | |||||

| Lynch, Sawynok, Hiew, and Marcon (2012)70 |

Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | Qigong Intervention = three 1/2 day workshop followed by weekly review/practice sessions over 8 weeks in addition 45–60 minutes of home practice per day Control = wait list control |

n= 100 Immediate intervention n = 53 Wait list control n = 47 Mean age = 52 years Immediate qigong completion rate = 83.01% at 2 months Wait-list qigong completion rate = 95.7% at 2 months Adverse events = 2/100 with one experiencing increased right shoulder pain and one experiencing plantar fasciitis |

4 and 6 month follow-up | Pain (numeric rating scale) Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) SF-36 health survey |

| Comments:*This is 1 of only 2 studies with 6-month follow-up; only study identified using chaoyi fanhaun qigong (CFQ). | |||||

| Liu, Zahner, Cornell, Le, Ratner, Wang, Pasnoor, Dimachkie and Barohn (2012)69 |

Single blinded | Qigong Intervention = home practice for 15–20 minutes twice daily and group exercise class for 45–60 minutes once daily for 6 weeks Control = home practice for 15–20 minutes twice daily and group exercise class for 45–60 minutes once weekly using “sham” qigong moves for 6 weeks |

n = 14 Intervention group n = 8 Mean age = 55.7 years Control group n = 6 Mean age = 57.5 years Total completion rate = 85.7% Intervention group completion rate = 75% Control group completion rate = 100% Adverse events = not addressed |

No follow up | Pre/post only Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ) Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) PSQI FIQ |

| Comments: 1 st study to test and report sham qigong arm. | |||||

| Haak and Scott (2008)66 | RCT Wait list control group |

Qigong 7-week qigong intervention consisting of 9 group sessions and approx. 11.5 hours total dose Home practice encouraged 2x/day |

n = 57 women Intervention n = 29 Wait list Control n = 28 Mean age = 53 years Total completion rate n = 53 (93%) Adverse events = not addressed |

4 month follow up | Pre/post/4 month follow up State Anxiety Inventory (STAI) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) World Health Organization Quality of Life BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) Daily self-recordings visual numerological scale (VNS) on pain, sleep, psychological health and distress |

| Comments: Use of he hua qigong style, only study done outside the United States. | |||||

| Mannerkorpi and Arndorw (2004)71 | RCT Pre/post test Control group usual standard of care |

Qigong 14 sessions over 3 month period, once weekly for 1.5 hours Home practice encouraged Data unclear regarding dose of home exercise performed |

n = 36 women Mean age = 45 years Adverse events = none reported |

No follow up | FIQ Body Awareness Rating Scale (BARS) Chair test hand grip Interviews |

| Comments: Differential attention between groups as standard care control didn’t meet in groups or receive attention from Primary Investigator (PI) other than at data collection points; significant change in body awareness and FIQ but not in measures of physical function; only qigong study with a negative outcome despite standard care group receiving no attention; 8 participants reported increased pain with qigong practice. | |||||

| Astin, Berman, Bauseil, Lee, Hochberg, and Forys (2003)59 |

RCT 2x4 |

Mindfulness meditation plus qigong 2.5 hour weekly sessions of mind-body intervention over 8 weeks 1.5 hr mindfulness meditation training and 1 hr qigong practice over 8 weeks Control group 2.5 hour educational sessions for 8 weeks |

n = 128 individuals Mean age = 47.7 years 8 week attrition = 39% (50) 16 week attrition = 48% (61) 24 week attrition = 49% (63) 25.8% never attended even one class (18.8% qigong; 32.8% control) Adverse events = not addressed |

4 and 6 month follow up | Baseline, 8,16, and 24 weeks Tender point count Total myalgic score Medical Outcome Study Short Form FIQ 6 minute walk test; BDI Medical care history Coping strategies questionnaire |

| Comments: 1 st study to report qigong intervention in fibromyalgia; largest study to date; 1 of 2 studies with 6 month follow up; equal attention paid to the sedentary control group; only study to use the ‘dance of the phoenix’ qigong style. | |||||

| Yoga studies | |||||

| Curtis, Osadchuk, and Katz (2012)67 | Time series design | Hatha yoga with mindfulness technique Twice weekly, 75 minute yoga classes per week over 8 weeks |

n = 22 Completion rate = 86.36% Mean age = 47.4 years Adverse events = not addressed |

No follow up | Pre/mid/post measures SF-MPQ Pain numeric rating scale Sum of Local Areas of Pain (SLAP) Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) Pain Disability Index (PDI) Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire (CPAQ) Salivary Cortisol measurement |

| Comments: Differs from the Carson study in that there was no didactic presentation prior to yoga practice; only study to measure Cortisol levels. | |||||

| Hennard (2011)67 | Single arm study No Control | Yoga of awareness 75 minute weekly sessions, once weekly over 8 weeks Home practice encouraged with posed illustration handouts |

n = 25 participants (24 women; 1 man) Mean age = 51 years Attrition rate 36% Adverse events = none reported |

No follow up | Pre/post measures FIQ |

| Comments: Smaller didactic proportion than the Carson study (15 vs 45 minutes); further evidence of efficacy of yoga of awareness piloted in the carson study. | |||||

| Carson, Carson, Jones, Mist and Bennett (2010)62 |

RCT Wait list replication |

Yoga with mindfulness 120 minute sessions, once weekly over 8 weeks Participants encouraged to practice at home 20—40 min/day 5–7x/week with DVD/CD |

n = 39 women Immediate intervention n = 21 Wait list control n= 18 Immediate intervention group completion rate = 88% 3 month follow up rate = 84% Wait list control group completion rate = 92.9% 3 month follow up completion rate = 64.3% Adverse events = not addressed |

3 months for immediate treatment group Post intervention for wait list group |

Pre/post/3 month follow up Revised FIQ (FIQR) Patient global impression of change Myalgic tender points Strength deficits (timed chair rise) Balance deficits (Sensory integration for balance test) CPAQ PCS Coping strategies (Vanderbilt multidimensional pain coping inventory) Daily diaries |

| Comments: 1st yoga study with group didactic discussion and presentation of mindfulness and yogic coping strategies; 2012 publication describes positive longer term follow up results. | |||||

| Tai Chi studies | |||||

| Romero-Zurita, Carbonell-Baeza, Aparicio, Ruiz, Tercedor and Delgado-Fernandez (2012)73 |

Single group No control |

8 form Yang style tai chi 60 minute tai chi sessions, 3 times weekly over 7 months |

n = 32 women Completion rate = 73% Adherence rate to intervention = 79.8% Adverse events = none reported |

3 months post intervention | Pre/post/3 months post intervention Tender points Senior functional fitness test battery Handgrip strength Blind flamingo Chair stand test Chair sit and reach test Back scratch test 8 feet up and go test 6 minute walk test FIQ Short form health survey 36 HADS Vanderbilt Pain Management Inventory (VPMI) Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) General self-efficacy scale |

| Comments: Longest tai chi study to date. | |||||

| Jones, Sherman, Mist, Carson, Bennett and Li (2012)68 |

RCT 2 parallel arms: tai chi and educational control |

8 form Yang tai chi 90 min tai chi sessions, 2 times weekly for 12 weeks (simplification of an 8-form Yang style program) Educational session lasting 90 minutes, 2 times weekly |

n = 101 participants Mean age = 54 years Completion rate = 97% At least 20/24 classes attended by 72% of participants Adverse events = none reported |

No follow up | Pre/post measures FIQ FIQ Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for pain severity Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) PSQI Arthritis self-efficacy questionnaire Functional mobility 8-foot Timed Up and Go (TUG) Balance-maximum reach test Static balance-timed single leg stance (STORK) Upper extremity flexibility-external and internal rotation of the shoulders by a hand to scapula movement |

| Comments: Enrolled 1/3 more subjects; tested increase functional mobility; used 8 form versus 10 form yang style tai chi. | |||||

| Carbonnell-Baeza, Romero, Aparicio, Ortega, Tercedor, Delgado-Fernandez and Ruiz (2011)61 | Open label Patient own control |

8 form Yang style tai chi 60 minute sessions, 3 times weekly for 16 weeks Each session included: 15 min warm-up, 30 min of tai chi, 15 minutes of relaxation exercises |

27 contacted, 9 consented, 3 not included due to not meeting ACR diagnostic criteria n = 6 Mean age = 52.3 years Adherence = 79.5% Adverse events = none reported |

3 month post intervention follow-up | Tenderness-algometer score Functional capacity-Height/Weight/Body Mass Index (BMI) Lower body muscular strength-30 sec chair stand test Upper body strength-handgrip strength Lower body flexibility- chair sit and reach test Upper body flexibility- the back scratch test Static balance- blind flamingo test Motor agility/dynamic balance- 8 feet up and go test Aerobic endurance- 6 minute walk test FIQ Short-form health survey (QOL) HADS |

| Comments: A 4 month tai chi intervention improved lower body flexibility in men with fibromyalgia that persisted through a detraining period. | |||||

| Wang, Schmid, Rones, Kalish, Yinh, Goldenberg, Lee and McAlindon (2010)75 | Single blind RCT | 10 form Yang style tai chi 60 minute tai chi sessions twice weekly for 12 weeks Control: 60 minute wellness education and stretching program twice weekly for 12 weeks |

n = 66 Control n = 33 Intervention n = 33 Mean age = 50 years 85% women 12 week class completion rate = 92.4% 24 week follow up completion rate = 89.4% Intervention adherence = 77% Control group adherence = 70% Adverse events = none reported |

24 week follow up | Measures 0,12 and 24 weeks FIQ measurement FIQ Patient global assessment (PGA) Physical global assessment PSQI 6 min walk test BMI SF-36 Health Survey |

| Comments: Only study complementary alternative medicine (CAM) or exercise trial in fibromyalgia to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine to date. | |||||

| Taggart, Arslanian, Bae and Singh (2003)74 | Open label No Control | Yang style short form tai chi 1 hour tai chi classes twice weekly for 6 weeks | n = 37 Mean age = 56.2 (35 women and 2 men) 2 withdrew; 2 couldn’t do exercises; 1 had back surgery; 9 had incomplete data sheets Adverse events = not addressed |

None | FIQ SF-36 Health Survey Baseline only: Wellbeing health history questionnaire |

| Comments: Meta analysis is based on pain not total FIQ; 1st attempt at tai chi study in fibromyalgia. | |||||

| Other CAM exercise studies | |||||

| Altan, Korkmaz, Bingol and Gunay (2009)58 | RCT | Pilates 1 hour pilates program 3 times weekly for 12 weeks following basic principles of Pilates method and using resistance bands and 26 cm pilates ball Control group usual care = home exercise relaxation/stretching program 3 times weekly for 12 weeks |

n = 50 Mean age = 49.16 years Total completion rate = 98% Intervention completion rate = 100% Adverse events = none reported |

Week 24 follow up measurement | Baseline, 12 and 24 weeks Pain-visual analog scale FIQ Tender point count- using standard pressure algometer Algometric score Lower extremity endurance-chair test SF-36 Health Survey Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) |

| Comments: Only study to look at pilates; merits further investigation due to positive findings and pilates emphasis on core muscles that articulate with the spine potential decreasing spine pain in fibromyalgia. | |||||

| Maddali-Bongi, Di Felice, Del Rosso, Landi, Maresca, Giambalvo Dal Ben, and Matucci-Cerinic (2011)72 | Pilot open study No control group Pre/post test 100% completion |

Body movement and perception method following resseguier method Twice weekly 50 minute sessions for 8 weeks 4 groups of 10 people each |

n = 40 women Mean age = 51.7 years Completion rate = 100% Adverse events = none reported |

No follow up | Visual Analog Scale (VAS) Pain intensity Pain temporal characteristics Pain during work activities Pain during recreational activities Interference of pain in night time rest General conditions (fatigue, irritability, well-being) Movement quality (Stiffness, agility) Subjective availability to focus on perception Ability to perceive the whole body Perceived postural self-control Ability to relax mind and body |

| Comments: Outcome measure pain intensity versus FIQ total; least physically active of all trials reviewed; may be a niche for those unwilling to do vigorous exercise. | |||||

| Carbonell-Baeza, Aparicio, Martins-Pereira, Gatto-Cardia, Ortega, Huertas, Tercedor, Ruiz, and Douglas-Fernandez (2010)60 | Non-random clinical trial with wait list replication | Biodanza 120 minute weekly sessions divided into 2 phases: Verbal (education/sharing) 35–45 minutes Vivencia (living experience) moving and dancing 75–80 minutes |

255 invited, 79 eligible, 7 did not meet inclusion criteria n = 71 Total completion rate = 83.1% Intervention completion rate = 72.97% Control completion rate = 94.12% Adverse events = none reported |

No follow-up | Pre and post assessment Tender points Body composition Physical fitness (functional senior fitness test battery) Lower body muscle strength (30 second chair stand test) Upper body muscle strength (handgrip strength) Lower body flexibility (chair sit and reach test) Upper body flexibility (back scratch test) Static balance (blind flamingo test) Aerobic endurance (6 min walk test) FIQ Short form health survey (health r/t QOL) HADS VPMI RSES General self-efficacy scale |

| Comments: Another example of didactic and movement component combined; unique dance style intervention; comprehensive outcome measures. | |||||

Abbreviations: BARS, Body Awareness Rating Scale; BDI, Beck Depression Inventory; BMI, Body Mass Index; BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; CAM, Complementary Alternative Medicine; CFQ, chaoyi fanhaun qigong; CPAQ, Chronic Pain Acceptance Questionnaire; FFMQ, Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire; FIQ, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire; FIQR, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire Revised; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MFI-20, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory; NHP, Nottingham Health Profile; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PDI, Pain Disability Index; PGA, Patient Global Assessment; PI, Primary Investigator; PSQI, Pittsburg Sleep Quality Index; QOL, Short form health survey; RCT, Randomized Controlled Trial; RSES, Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; SF-36, Short Form-36; SF-MPQ, Short Form McGill Pain Questionnaire; SLAP, Sum of Local Areas of Pain; STAI, State Anxiety Inventory; STORK, Static balance-timed single leg stance; TUG, Timed Up and Go; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; VNS, Visual Numerological Scale; VPMI, Vanderbilt Pain Management Inventory; WHO, World Health Organization; WHOQOL-BREF, WHO Quality of Life BREF.

Participants

A total of 832 FM patients participated in the reviewed studies, with 490 allocated to the CAM exercise interventions. The median of the sample size for the CAM exercise interventions was 23 (range 6–64). The median percentage of patients completing the study was 81%, and there was no significant difference in dropout among those studies that included a comparison arm.58–75 In all of the studies, the FM diagnosis was made in accordance with the American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria.52

Outcomes

In all studies, except for one by Curtis et al, the FIQ total score or FIQ Pain Score was used as the primary outcome. The Curtis et al study used the McGill Pain Questionnaire, and in this case, the total McGill Pain Questionnaire was analyzed.64 Most studies reported both pre- and posttreatment scores, with a number reporting longer-term follow ups. For the purpose of the current analysis, only pre- and post-effects were assessed. There were no significant differences among the baseline means and standard deviations across the studies.

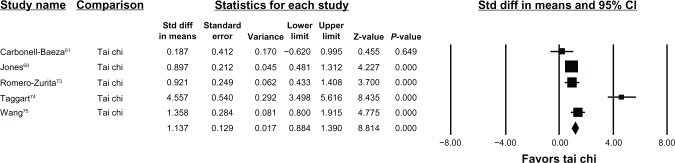

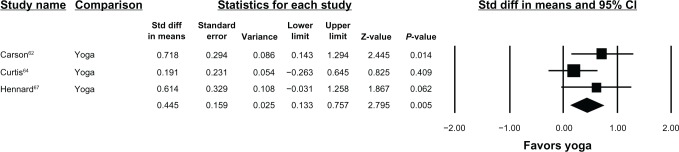

Meta-analyses

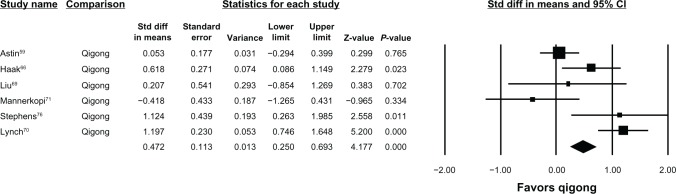

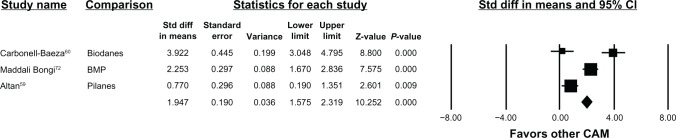

The standard difference in means (0.84), and standard errors (0.07) for CAM exercise, indicates a statistically significant (P = 0.00) and positive outcome. The individual forest plots for qigong, tai chi, yoga, and all others are reported in Figures 2–5 respectively. With the exception of two studies, all studies reported positive outcomes.71 Of those not reporting positive outcomes, Mannerkorpi and Arndorw71 found no difference between 14 weeks of qigong versus a sedentary “usual care” control in 36 FM patients. Likewise, Carbonell-Baeza et al61 concluded that a 4-month male tai chi study (n = 6) was negative for symptom improvement.

Figure 2.

Qigong forest plot.

Abbreviations: std diff, standard difference; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 5.

Other CAM forest plot.

Abbreviations: BMP, body movement and perception therapy; CAM, complementary and alternative medicine; std diff, standard difference; CI, confidence interval.

Sensitivity analyses

A funnel plot of the Std diff in means indicates that if the standard difference in means (0.84) is true, there is little evidence for reporting bias. The majority of studies fell within two standard deviations, with an equal number of studies falling outside this on either side of the plot (Figure 6). A regression of the Jadad scores on the standard difference of means indicates more variation reported in the lower scores and less in the higher scores, with a slight increase in the slope seen with higher scores (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

Funnel plot of standard error by standard difference in means.

Abbreviation: std diff, standard difference.

Figure 7.

Regression of Jadad score on standard difference in means (Jadad et al, 1996).57

Abbreviation: std diff, standard difference.

Validity analysis

There was a significant amount of heterogeneity in the studies presented in this analysis. This can be seen in the means and confidence intervals in the subplots. The distributions of the forest plots suggest that the results are randomly distributed, indicating that the results are mostly consistent within each type of exercise.

Discussion

The data presented support the likely safety of CAM exercise interventions, as 832 participants were enrolled in 16 studies and 81% completed the studies without differential attrition by study arm or exercise modality.58–75 Only one study reported negative side effects (increased shoulder pain and plantar fasciitis) in two study participants.70 All studies reported that there were no serious adverse events.

The data also support some degree of efficacy of several of the CAM exercise interventions in improving overall FM symptoms and physical function. Taken as a whole, the data do not indicate that any one intervention type is consistently superior to another, though the strongest effects were for the exercise modalities with the largest number of trials: qigong (Std diff in means 0.47; P < 0.000) and tai chi (Std diff in means 1.14; P < 0.000). Further support for qigong comes from a trial excluded from this analysis. Stephens et al76 randomized 30 children (ages 8–18) with FM to aerobics or qigong. There was no difference between study arms, although qigong was intended to be the control group. The qigong group did demonstrate significant within-group changes, indicating that pediatric CAM exercise interventions may be a promising area of research. This is critical, as few interventions address pediatric FM even though its recognition as a valid diagnosis is increasing. This may indicate that mind–body exercises may be a feasible therapeutic option across a wider range of developmental states.76–80

Complete data were only available for three yoga trials (two were open labeled) but were positive (Std diff in means 0.45; P < 0.015).62,64,67 Additional support for the benefit of yoga is found in two studies that are not represented in the analyses due to missing data. da Silva et al65 randomized 40 women with FM into an individually delivered intervention of “relaxing” yoga with or without additional tui na (massage). Both groups experienced clinically and statistically significant reductions in FIQ total scores, but there was no difference between treatment arms. Another trial (n = 10) noted a 28% improvement in FIQ total scores following eight weeks of gentle Hatha yoga.81 Three other CAM-based exercise studies were positive, but the interventions have yet to be replicated (pilates, Biodanza, and Resseguier with body movement and perception).58,60,72 Pilates is a series of nonimpact strength, flexibility, and breathing exercises designed by Joseph Pilates to promote inner awareness and core stability. Biodanza, literally “life-dance,” is a program of exercise that seeks to optimize self-development and deepen self-awareness. It most often uses dance, music, singing, and other movements to promote positive feelings, emotional expression, and connection to others and to nature. Resseguier is based on selected soft, low-impact gymnastic movements integrated with postural self-control, body alignment, and relaxation.

The data are consistent with an earlier rigorous report on “mindful” meditative movement therapies that concluded that these therapies were safe and effective for reducing sleep disturbances, fatigue, and depression, and improving quality of life. In subanalyses, the authors found that only yoga also relieved pain.50 However, that meta-analysis was comprised of only RCTs (n = 7). The current data extend these findings by demonstrating efficacy in a combination of FM symptoms and physical function, in a larger number of studies (n = 16).

This meta-analysis shows that research in the area was at an early state (six open-labeled studies), although regressing by Jadad score showed that there was a nonsignificant difference by effect size. This may indicate that early-stage studies are not likely to overreport effect.

This study does have limitations, the greatest being that six of the studies were open labeled. Others may argue, however, that open-labeled trials are appropriate in early-phase research when safety, feasibility, and effect sizes are being determined.82 Further, because open-labeled studies were included, community-based exercise studios and instructors were tested, leading the field toward effectiveness rather than efficacy outcomes. The studies were generally small (average n = 51.5; range 6 to 128 participants), limiting their power and the ability to test multiple comparisons or to profile responders’ reliability.

Another limitation is that the studies were largely conducted in middle-aged women, in America and Europe. This is important, as many CAM exercise studies have been conducted in India and China, where many of these traditions are rooted (however, those studies were not available in English or from major database sources). Moreover, differential effects may be found in men, minorities, children and elders. Another limitation is that all the trials employed a single interventionist and did not rate treatment expectancy. It is possible, therefore, that a charismatic or caring instructor, rather than the intervention itself, may have been responsible for the beneficial outcome, although this is less likely in the trials that have been replicated (qigong, tai chi, and yoga). Future effectiveness studies could use multiple instructors.

A goal of future studies should include the standardization of exercise protocols, including scripting for mindfulness, posture sequences, and a range of modifications based on the patient’s physical ability. To date, studies have varied considerably in exercise dose and have not always provided adequate description of the intervention to allow replication. Publishing protocols in peer-reviewed journals would provide opportunities for a more detailed description of the actual intervention and for pictures of the less common poses or physical strategies. This is important because people with FM are likely to be in poor physical condition, have joint hypermobility, and poor balance, and may be at an increased risk for injury.42

Future studies should incorporate validated scales such as the revised FIQ (FIQ-R), Brief Pain Inventory, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, Medical Outcomes Study Sleep Scale, and Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire.83,84 Full reporting of data and statistical tests will allow for more seamless comparison in future trials. Some FM exercise studies now report the number needed to treat, based on Patients’ Global Impression of change (PGIC) scale, which allows for direct comparison with pharmaceutical trials.85 Similarly, work is underway to develop a responder index.86

In conclusion, the CAM-based exercise therapies reviewed are likely safe, and no serious adverse events were reported in any study. These exercise programs were somewhat efficacious for FM pain, with many studies reporting improvement in overall FM symptoms and physical function. However, the majority of studies had lower methodological quality. There is a need for large, rigorous trials with active parallel arms–such as traditional aerobic exercise compared with CAM-based exercise – to extend this body of evidence.

Figure 3.

Tai chi forest plot.

Abbreviations: std diff, standard difference; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Yoga forest plot.

Abbreviations: std diff, standard difference; CI, confidence interval.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jain AK, Carruthers BM, van de Sande MI, et al. Fibromyalgia syndrome: Canadian clinical working case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols – A consensus document. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2004;11(4):3–107. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macfarlane GJ, McBeth J, Silman AJ. Widespread body pain and mortality: prospective population based study. BMJ. 2001;323(7314):662–665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7314.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macfarlane GJ. Chronic widespread pain and fibromyalgia: Should reports of increased mortality influence management? Current Rheumatol Rep. 2005;7(5):339–341. doi: 10.1007/s11926-005-0017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White KP, Harth M. Classification, epidemiology, and natural history of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5(4):320–329. doi: 10.1007/s11916-001-0021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burckhardt CS, Bjelle A. Perceived control: A comparison of women with fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and systematic lupus erythematosus using a Swedish version of the rheumatology attitudes index. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25(5):300–306. doi: 10.3109/03009749609104062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ledingham J, Doherty S, Doherty M. Primary fibromyalgia syndrome – an outcome study. Br J Rheumatol. 1993;32(2):139–142. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/32.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolfe F, Anderson J, Harkness D, et al. Work and disability status of persons with fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(6):1171–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez JE, Ferraz MB, Sato EL, Atra E. Fibromyalgia versus rheumatoid arthritis: a longitudinal comparison of the quality of life. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(2):270–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berger A, Dukes E, Martin S, Edelsberg J, Oster G. Characteristics and healthcare costs of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Int J Clin Pract. 2007;61(9):1498–1508. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones J, Rutledge DN, Jones KD, Matallana L, Rooks DS. Self-assessed physical function levels of women with fibromyalgia: a national survey. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(5):406–412. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones KD, King LA, Mist SD, Bennett RM, Horak FB. Postural control deficits in people with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(4):R127. doi: 10.1186/ar3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA, Sjöström M, Ruiz JR, Delgado-Fernández M. Pain and functional capacity in female fibromyalgia patients. Pain Med. 2011;12(11):1667–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panton LB, Kingsley JD, Toole T, et al. A comparison of physical functional performance and strength in women with fibromyalgia, age- and weight- matched controls, and older women who are healthy. Phys Ther. 2006;86(11):1479–1488. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20050320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jensen KB, Kosek E, Petzke F, et al. Evidence of dysfunctional pain inhibition in Fibromyalgia refected in rACC during provoked pain. Pain. 2009;144(1–2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staud R, Nagel S, Robinson ME, Price DD. Enhanced central pain processing of fibromyalgia patients is maintained by muscle afferent input: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2009;145(1–2):96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson ME, Craggs JG, Price DD, Perlstein WM, Staud R. Gray matter volumes of pain-related brain areas are decreased in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2011;12(4):436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis CA. Sleep, pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;98:613–637. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52006-7.00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones KD, Deodhar P, Lorentzen A, Bennett RM, Deodhar AA. Growth hormone perturbations in fibromyalgia: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):357–379. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross RL, Jones KD, Bennett RM, Ward RL, Druker BJ, Wood LJ. Preliminary evidence of increased pain and elevated cytokines in fibromyalgia patients with defective growth hormone response to exercise. Open Immunol. 2010;3:9–18. doi: 10.2174/1874226201003010009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DA, Clauw DJ. Understanding fibromyalgia: lessons from the broader pain research community. J Pain. 2009;10(8):777–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Staud R. Peripheral pain mechanisms in chronic widespread pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elven A, Siösteen AK, Nilsson A, Kosek E. Decreased muscles blood flow in fibromyalgia patients during standardised muscle exercise: a contrast media enhanced colour Doppler study. Eur J Pain. 2006;10(2):137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ge HY, Arendt-Nielsen L, Madeleine P. Accelerated muscle fatigability of latent myofascial trigger points in humans. Pain Med. 2012;13(7):957–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srikuea R, Symons TB, Long DE, et al. Fibromyalgia is associated with altered skeletal muscle characteristics which may contribute to post-exertional fatigue in post-menopausal women. Arthritis Rheum. Nov 1, 2012. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Yunus MB. Fibromyalgia and overlapping disorders: the unifying concept of central sensitivity syndromes. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007;36(6):339–356. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aaron LA, Burke MM, Buchwald D. Overlapping conditions among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and temporomandibular disorder. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(2):221–227. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crofford LJ, Rowbotham MC, Mease PJ, et al. Pregabalin for the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(4):1264–1273. doi: 10.1002/art.20983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Häuser W, Petzke F, Sommer C. Comparative efficacy and harms of duloxetine, milnacipran, and pregabalin in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Pain. 2010;11(6):505–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mease PJ, Choy EH. Pharmacotherapy of fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35(2):359–372. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Gendreau RM, et al. The efficacy and safety of milnacipran for treatment of fibromyalgia. a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(2):398–409. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell IJ, Mease PJ, Smith TR, et al. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder: Results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. Pain. 2008;136(3):432–444. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staud R. Sodium oxybate for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12(11):1789–1798. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.589836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen S, Bliddal H, et al. EULAR EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67(4):536–541. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292(19):2388–2395. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Häuser W, Arnold B, Eich W, et al. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome – an interdisciplinary evidence-based guideline. Ger Med Sci. 2008;6 Doc 14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sim J, Adams N. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of nonpharmacological interventions for fibromyalgia. Clin J Pain. 2002;18(5):324–336. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, et al. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic fitness exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 1. Phys Ther. 2008;88(7):857–871. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, et al. Ottawa panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for strengthening exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 2. Phys Ther. 2008;88(7):873–886. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Busch A, Schachter CL, Peloso PM, Bombardier C. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(3):CD003786. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Häuser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, et al. Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(3):R79. doi: 10.1186/ar3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones KD, Liptan GL. Exercise interventions in fibromyalgia: clinical applications from the evidence. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35(2):373–391. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Busch AJ, Webber SC, Brachaniec M, et al. Exercise therapy for fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15(5):358–367. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0214-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Hootman JM, Jones DL. Exercise and global well-being in community-dwelling adults with fibromyalgia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cazzola M, Atzeni F, Pilaff F, Stisi S, Cassisi G, Sarzi-Puttini P. Which kind of exercise is best in fibromyalgia therapeutic programmes? A practical review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(6 Suppl 63):S117–S124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meyer BB, Lemley KJ. Utilizing exercise to affect the symptomology of fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(12):1691–1697. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nørregaard J, Lykkegaard JJ, Mehlsen J, Danneskiold-Samsøe B. Exercise training in treatment of fibromyalgia. J Musculoskelet Pain. 1997;5(1):71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mist SD, Jones KD, Carson JW. Yoga Internet Survey in Fibromyalgia: A K23 Subproject; National State of the Science Congress on Nursing Research; 2012 September 13–15; Washington DC, USA; [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wahner-Roedler DL, Elkin PL, Vincent A, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies by patients referred to a fibromyalgia treatment program at a tertiary care center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(11)62958-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ, Bernardy K, Häuser W. Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int. 2012;33(1):193–207. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.nccam.nih.gov [homepage on the Internet] What is complementary and alternative medicine? National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine; 2008[updated July 2011]. Available from: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam#definingcamAccessed October 30, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolfe C, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(2):160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire (FIQ): development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:728–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calandre EP, Rodriguez-Claro ML, Rico-Villademoros F, Vilchez JS, Hidalgo J, Delgado-Rodriguez A. Effects of pool-based exercise in fibromyalgia symptomatology and sleep quality: a prospective randomised comparison between stretching and Ai Chi. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(5 Suppl 56):S21–S28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ide MR, Laurindo LMM, Rodrigues-Junior AL, Tanaka C. Effect of aquatic-respiratory exercise-based program in patients with fibromyalgia. Int J Rheumat Dis. 2008;11(2):131–140. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Higgins JPT, Green S.Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.orgAccessed January 23, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized controlled trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Altan L, Korkmaz N, Bingol U, Gunay B. Effect of pilates training on people with fibromyalgia syndrome: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(12):1983–1988. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Astin JA, Berman BM, Bausell B, Lee WL, Hochberg M, Forys KL. The efficacy of mindfulness meditation plus Qigong movement therapy in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. J Rheumatol. 2003;30(10):2257–2262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA, Martins-Pereira CM, et al. Efficacy of Biodanza for treating women with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(11):1191–1200. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carbonell-Baeza A, Romero A, Aparicio VA, et al. Preliminary findings of a 4-month Tai Chi intervention on tenderness, functional capacity, symptomatology, and quality of life in men with fibromyalgia. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5(5):421–429. doi: 10.1177/1557988311400063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carson JW, Carson KM, Jones KD, Bennett RM, Wright CL, Mist SD. A pilot randomized controlled trial of the Yoga of Awareness program in the management of fibromyalgia. Pain. 2010;151(2):530–539. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen KW, Hassett AL, Hou F, Staller J, Lichtbroun AS. A pilot study of external qigong therapy for patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(9):851–856. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Curtis K, Osadchuk A, Katz J. An eight-week yoga intervention is associated with improvements in pain, psychological functioning and mindfulness, and changes in cortisol levels in women with fibromyalgia. J Pain Res. 2011;4:189–201. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S22761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.da Silva GD, Lorenzi-Filho G, Lage LV. Effects of yoga and the addition of Tui Na in patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(10):1107–1113. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haak T, Scott B. The effect of Qigong on fibromyalgia (FMS): a controlled randomized study. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30(8):625–633. doi: 10.1080/09638280701400540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hennard J. A protocol and pilot study for managing fibromyalgia with yoga and meditation. Int J Yoga Therapy. 2011;(21):109–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jones KD, Sherman CA, Mist SD, Carson JW, Bennett RM, Li F. A randomized controlled trial of 8-form Tai Chi improves symptoms and functional mobility in fibromyalgia patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31(8):1205–1214. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-1996-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu W, Zahner L, Cornell M, et al. Benefit of Qigong exercise in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Int J Neurosci. 2012;122(11):657–664. doi: 10.3109/00207454.2012.707713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lynch M, Sawynok J, Hiew C, Marcon D. A randomized controlled trial of qigong for fibromyalgia. Arthritis Res Ther. 2012;14(4):R178–R189. doi: 10.1186/ar3931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mannerkorpi K, Arndorw M. Efficacy and feasibility of a combination of body awareness therapy and qigong in patients with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36(6):279–281. doi: 10.1080/16501970410031912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maddali Bongi S, Di Felice C, Del Rosso A, et al. Efficacy of the “body movement and perception” method in the treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome: an open pilot study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29(6 Suppl 69):S12–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Romero-Zurita A, Carbonell-Baeza A, Aparicio VA, Ruiz JR, Tercedor P, Delgado-Fernández M. Effectiveness of a tai-chi training and detraining on functional capacity, symptomatology and psychological outcomes in women with fibromyalgia. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:614196. doi: 10.1155/2012/614196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Taggart HM, Arsianian CL, Bae S, Singh K. Effects of Tai Chi exercise on fibromyalgia symptoms and health-related quality of life. Orthop Nurs. 2003;22(5):353–360. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang C, Schmid CH, Rones R, et al. A randomized trial of tai chi for fibromyalgia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):743–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stephens S, Feldman BM, Bradley N, et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of an aerobic exercise program in children with fibromyalgia: Results of a randomized controlled pilot trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(10):1399–1406. doi: 10.1002/art.24115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Anthony KK, Schanberg LE. Juvenile primary fibromyalgia syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2001;3(2):165–171. doi: 10.1007/s11926-001-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Buskila D. Pediatric fibromyalgia. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35(2):253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gedalia A, García CO, Molina JF, Bradford NJ, Espinoza LR. Fibromyalgia syndrome: experience in a pediatric rheumatology clinic. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18(3):415–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Siegel DM, Janeway D, Baum J. Fibromyalgia syndrome in children and adolescents: clinical features at presentation and status at follow-up. Pediatrics. 1998;101(3 Pt 1):377–382. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.3.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rudrud L. Gentle Hatha yoga and reduction of fibromyalgia-related symptoms: a preliminary report. Int J Yoga Therap. 2012;(22):53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meinert CL. Clinical Trials: Design, Conduct, and Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Williams DA, Arnold LM. Measures of fibromyalgia: Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20), Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), Sleep Scale, and Multiple Ability Self-Report Questionnaire (MASQ) Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63(Suppl 11):S86–S97. doi: 10.1002/acr.20531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bennett RM, Friend R, Jones KD, Ward R, Han BK, Ross RL. The revised FM impact questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(4):R120. doi: 10.1186/ar2783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Williams DA, Kuper D, Segar M, Mohan N, Sheth M, Clauw DJ. Internet-enhanced management of fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2010;151(3):694–702. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mease PJ, Clauw DJ, Christensen R, et al. OMERACT Fibromyalgia Working Group Toward development of a fibromyalgia responder index and disease activity score: OMERACT module update. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(7):1487–1495. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]