Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

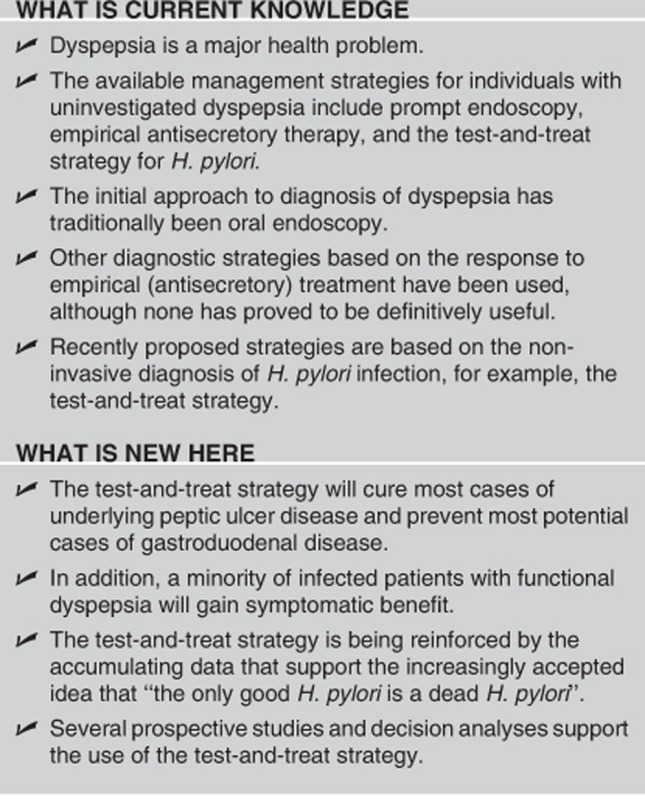

Deciding on whether the Helicobacter pylori test-and-treat strategy is an appropriate diagnostic–therapeutic approach for patients with dyspepsia invites a series of questions. The aim present article addresses the test-and-treat strategy and attempts to provide practical conclusions for the clinician who diagnoses and treats patients with dyspepsia.

METHODS:

Bibliographical searches were performed in MEDLINE using the keywords Helicobacter pylori, test-and-treat, and dyspepsia. We focused mainly on data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, meta-analyses, cost-effectiveness analyses, and decision analyses.

RESULTS:

Several prospective studies and decision analyses support the use of the test-and-treat strategy, although we must be cautious when extrapolating the results from one geographical area to another. Many factors determine whether this strategy is appropriate in each particular area. The test-and-treat strategy will cure most cases of underlying peptic ulcer disease, prevent most potential cases of gastroduodenal disease, and yield symptomatic benefit in a minority of patients with functional dyspepsia. Future studies should be able to stratify dyspeptic patients according to their likelihood of improving after treatment of infection by H. pylori.

CONCLUSIONS:

The test-and-treat strategy will cure most cases of underlying peptic ulcer disease and prevent most potential cases of gastroduodenal disease. In addition, a minority of infected patients with functional dyspepsia will gain symptomatic benefit. Several prospective studies and decision analyses support the use of the test-and-treat strategy. The test-and-treat strategy is being reinforced by the accumulating data that support the increasingly accepted idea that “the only good H. pylori is a dead H. pylori”.

INTRODUCTION

Although many definitions of dyspepsia have been proposed, perhaps the most widely accepted is that of “persistent or recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen”. Dyspepsia is a major health problem, whose prevalence reaches >10% among adult populations.1, 2, 3 Approximately 20 to 30% of people in the community each year report chronic or recurrent dyspeptic symptoms,4, 5 and consultations for dyspepsia account for up to 40% of referrals among gastroenterology outpatients.6 Furthermore, the already high costs of diagnosis and treatment of dyspepsia have been increasing.7

Based on prospective studies of subjects who report dyspeptic symptoms for the first time, incidence is approximately 1% per year.5, 8 Most patients with unexplained dyspeptic symptoms continue to be symptomatic in the long term despite periods of remission.9 Approximately one in two subjects seeks health care for dyspeptic symptoms at some time in their life.10

The initial approach to diagnosis of dyspepsia has traditionally been oral endoscopy; however, generalized use of this approach does not seem to be a realistic option. Consequently, other diagnostic strategies based on the response to empirical treatment have been used, although none has proved to be definitively useful. In empirical therapy-based strategies, endoscopy is used only in cases of lack of response to antisecretory or promotility agents. However, this policy has been reported to achieve only modest savings and has been considered to be inappropriate: the initial saving achieved by avoiding endoscopy is lost, as the likelihood of eventual endoscopy increases during follow-up.11

Recently proposed strategies are based on the non-invasive diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. The most outstanding is the so-called “test-and-treat” strategy.12 As its name indicates, this strategy is based on the investigation of the presence of H. pylori and its subsequent eradication when detected. Symptomatic treatment, on the other hand, could be given to non-infected patients. The test-and-scope strategy13, 14—performing a test to detect H. pylori in all patients and endoscopy only in those who are shown to be infected—has been considered less useful and is therefore not applied in clinical practice.13, 14

Deciding on whether the test-and-treat strategy is an appropriate diagnostic-therapeutic approach invites a series of questions: is there enough scientific evidence to recommend its use? Is this approach universally valid, or does its efficiency depend on factors that change from one geographic area to another? Is this strategy affected by non-financial considerations? The present article addresses the test-and-treat strategy and attempts to provide practical conclusions for the clinician who diagnoses and treats patients with dyspepsia. Thus, the aspects of the test-and-treat strategy to be reviewed are as follows: (i) age threshold at which test-and-treat could be applied; (ii) cost and availability of endoscopy; (iii) prevalence of H. pylori infection in the study population; (iv) type of diagnostic methods used to detect H. pylori infection; (v) proportion of H. pylori-positive patients who have or who are going to develop peptic ulcer and the proportion of ulcers attributable to H. pylori; (vi) role of H. pylori in the development of gastric cancer; (vii) role of H. pylori in functional dyspepsia; (viii) efficacy, cost, and adverse effects of H. pylori eradication therapy; (ix) risk of missing serious diseases; (x) use of endoscopy or an empirical proton pump inhibitor (PPI) after failure of the test-and-treat strategy; (xi) patient satisfaction; (xii) follow-up time; and (xiii) setting of testing (primary care vs. secondary care).

SEARCH STRATEGY

Bibliographical searches were performed in MEDLINE up to July 2012 using the following keywords (all fields): (“Helicobacter pylori” OR “H. pylori”) AND (“test-and-treat” OR “test and treat” OR dyspepsia). Articles published in any language were included. Reference lists from the trials selected in the electronic search were hand-searched to identify further relevant trials. Abstracts of the articles selected in each of the multiple searches were reviewed, and those meeting the inclusion criteria (i.e., addressing the H. pylori test-and-treat strategy in dyspeptic patients) were selected. References from reviews on management of dyspepsia were also examined to identify articles meeting the inclusion criteria. In the case of duplicate reports or studies reporting results from the same study population, only the most recent published results were used. We focused mainly on data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), systematic reviews, meta-analyses, cost-effectiveness analyses, and decision analyses published in the literature.

RATIONALE OF THE TEST-AND-TREAT STRATEGY

Even after performing several diagnostic tests, biochemical or organic disturbances explaining dyspeptic symptoms cannot be found in most cases. Such patients can be classified as having functional or non-ulcer dyspepsia.15 However, because patients with dyspepsia may have serious underlying diseases, the initial evaluation has traditionally included endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The main advantage of endoscopy is its high diagnostic accuracy. A normal endoscopy result reassures both the patient who consults owing to fear of having a serious disease and the physician.

However, endoscopy has several disadvantages: it is uncomfortable, expensive, and not free of risk. In addition, as endoscopy centers have been meeting increasing demands,16 the technique frequently involves prolonged waiting times. Furthermore, a large proportion of endoscopy findings are normal and thus do not contribute to management. In summary, although a strategy including endoscopic evaluation of the upper gastrointestinal tract in all patients with dyspepsia is obviously a theoretical option, it is not realistic in clinical practice.

As a consequence of the aforementioned problems, particularly limited resources and the large number of normal findings, several diagnostic policies have been proposed for selecting patients with symptoms of dyspepsia who are expected to benefit most from the procedure, thus reducing the number of endoscopies. To avoid the theoretical risk of delaying the diagnosis of a malignant neoplasm, these strategies have been recommended only in “young” patients (see later for the definition of this variable), with no “alarm” symptoms (such as unexplained weight loss, progressive dysphagia, recurrent vomiting, anemia, bleeding, or an abdominal mass); otherwise, endoscopy should be performed.

RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIALS

The test-and-treat strategy has been compared with prompt endoscopy and with empirical therapy. In this section, these two relevant comparisons will be evaluated individually.

(1) Test-and-treat vs. prompt endoscopy

The test-and-treat strategy has been compared with prompt endoscopy in eight RCTs (Table 1),17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 which differ in important ways: in three trials17, 19, 20 patients were recruited and randomized at the endoscopy unit after their general practitioner had referred them for investigation; in five trials18, 21, 22, 23, 24 patients were randomized in primary care. It is noteworthy that the studies by Jones et al.18 and Duggan et al.24 used near-patient serology, which has very poor accuracy for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection; this important drawback markedly reduces the reliability of results.25 Furthermore, Arents et al.21 used the serology result from a venous blood sample to diagnose H. pylori infection; although more reliable than office serology, this test is far less accurate than the 13C-urea breath test, which was the diagnostic test in the remaining studies. Three studies recruited only individuals <45 years of age,17, 18, 23 two studies set the age cutoff at 55 years,20, 21 and no age limit was applied in the remaining three studies.19, 22, 24 Most studies randomized participants to H. pylori testing or endoscopy, but Heaney et al.17 randomized only H. pylori-positive patients to either treatment or prompt endoscopy.

Table 1. Randomized controlled trials comparing test-and-treat strategy vs. prompt endoscopy.

| Author | Year of publication | Country | Number of patientsa | Age limit (years) | Setting | H. pylori diagnostic methods | H. pylori infection prevalencea | H. pylori eradication treatmenta | H. pylori eradication ratea | Follow-up time (months) | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heaney et al.17 | 1999 | UK | 52 | <45 | Secondary care | UBT | 100% | PPI+C+N | 78% | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life |

| Jones et al.18 | 1999 | UK | 141 | <45 | Primary care | Office-based serology | 41% | Unknownb | Unknown | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Costs/use of medical resources |

| Lassen et al.19c | 2000 | Denmark | 250 | No age limitd | Primary and secondary care | UBT | 26% | PPI+A+N | 87% | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

| McColl et al.20 | 2002 | UK | 356 | <55 | Secondary care | UBT | 48% | PPI+C+A | 84% | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

| Arents et al.21 | 2003 | The Netherlands | 141 | <55 | Primary care | Serology | 38% | PPI+A+C/N | 87 | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

| Hu et al.22 | 2006 | China | 78 | No age limitd | Primary care | UBT | 53% | PPI+C+A | Unknowne | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

| Mahadeva et al.23 | 2008 | Malaysia | 222 | <45 | Primary care | UBT | 35% | PPI+C+A | Unknownf | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Patient satisfaction Medication consumption Costs/use of medical resources |

| Duggan et al.24 | 2009 | UK | 198 | No age limitd | Primary care | Near-patient serology | 23% | PPI+C+N | Unknown | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

Abbreviation: UBT, 13C-urea breath test.

H. pylori eradication treatment: A, amoxicillin; C, clarithromycin; N, nitroimidazole; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

In the test-and-treat group.

No specific regimen was determined, but PPI-based triple therapy was recommended.

The long-term results of this study have been published.26

Age threshold at 70 years.

Eradication rate was found to be 88% locally.

Eradication rate was found to be 91% locally.

None of the studies demonstrated that prompt endoscopy enabled symptoms to be cured. One small study reported significantly lower symptom scores in subjects randomized to test-and-treat at 12 months.17 Seven of the above-mentioned trials reported cost data and all demonstrated a significant reduction in the total number of endoscopies with a test-and-treat strategy,18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 with two studies reporting that test-and-treat was the most cost-effective management strategy.22, 24 Follow-up in all these studies was limited to 12 months, so it is uncertain whether the observed cost reductions generated using the test-and-treat strategy instead of prompt endoscopy is sustained in the long term. Interestingly, Lassen et al.26 evaluated subjects 6 years after enrollment. The rates of endoscopy and the need for acid suppression therapy in those managed with a test-and-treat strategy remained as low as that observed at 12 months. The prevalence of dyspeptic symptoms was similar in both arms (test-and-treat and endoscopy). See “Follow-up time” section (below) for more detailed information of this long-term follow-up study.

(2) Test-and-treat vs. empirical antisecretory therapy

Four RCTs have compared the test-and-treat strategy with empirical acid suppression therapy in primary care (Table 2).24, 27, 28, 29 One of these studies27 was performed entirely in secondary care. The patients were followed-up intensively every 2 months, and all those who were still symptomatic at 4 weeks or who experienced recurrence of symptoms at any point during follow-up were offered endoscopy. Around 90% of the PPI-treated group and 60% of the test-and-treat group underwent endoscopy owing to recurrence of symptoms: this difference was very statistically significant in favor of the test-and-treat strategy. As mentioned above, the study by Duggan et al.24 used near-patient serology, which has poor accuracy for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection.25 This may have led to a considerable underestimation of the efficacy of test-and-treat for dyspepsia, as infected individuals could have been incorrectly labeled as being H. pylori-negative and treated with 4 weeks of PPI (rather than eradication therapy), and uninfected patients might have received eradication therapy.30

Table 2. Randomized controlled trials comparing test-and-treat strategy with empirical antisecretory therapy.

| Author | Year of publication | Country | Number of patientsa | Age limit (years) | Setting | H. pylori diagnostic methods | H. pylori infection prevalencea | H. pylori eradication treatmenta | H. pylori eradication ratea | Follow-up time (months) | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manes et al.27 | 2003 | Italy | 110 | <45 | Secondary care | UBT | 61% | PPI+C+N | 94% | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Costs/use of medical resources |

| Jarbol et al.28 | 2006 | Denmark | 250 | No age limit | Primary care | UBT | 24% | PPI+C+A | Unknown | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

| Delaney et al.29 | 2008 | UK | 343 | No age limitb | Primary care | UBT | 29% | PPI+C+N | 78% | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

| Duggan et al.24 | 2009 | UK | 198 | No age limit | Primary care | Near-patient serology test | 23% | PPI+C+N | Unknown | 12 | Dyspeptic symptoms Quality of life Patient satisfaction Costs/use of medical resources |

Abbreviation: UBT, 13C-urea breath test.

H. pylori eradication treatment: A, amoxicillin; C, clarithromycin; N, nitroimidazole; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

In the test-and-treat group.

Age threshold at 65 years.

Only Manes et al.27 demonstrated a clear benefit of either test-and-treat or empirical PPI strategies, possibly because theirs was the only study performed in an area of high prevalence of H. pylori. Costs were very similar in both arms in one of these studies.29 Of the remaining trials, one did not perform a cost analysis, one concluded that empirical acid suppression therapy was probably not cost-effective,31 and one showed that empirical PPI therapy only became cost-effective when willingness to pay per patient cured was very low (<€215).24

Although RCTs generally have the highest quality design, they may have limitations. Thus, wide variability in trial design and outcomes has been reported. The shortcomings of the aforementioned RCTs include lack of agreement on the definition of dyspepsia, use of ineffective H. pylori diagnostic tests or eradication regimens, inadequate sample size, differences in setting (primary vs. secondary care), differences in the upper age limit for inclusion (from <45 to <55 years, or even without age limit), or insufficient length of follow-up. With respect to this last variable, for example, a test-and-treat strategy may not be expected to be superior to the empirical antisecretory therapy in the short term. However, it is conceivable that an H. pylori eradication strategy provides a sustained benefit for many patients, whereas the benefit of antisecretory treatment is expected to fade after the end of the treatment. This sustained benefit could be demonstrated only after long-term follow-up.

META-ANALYSES

To evaluate the effectiveness of the test-and-treat strategy, a formal meta-analysis would not be appropriate given the variation in trial design and outcome measures.32 A qualitative and semiquantitative review seems to be more appropriate and can still provide useful information to guide the management of dyspepsia.32

Conflicting results and incomplete reporting in the aforementioned RCTs means that uncertainty remains over which of these management strategies is the most effective for curing symptoms, and which is the most cost-effective.33 This issue has been addressed by two individual patient data meta-analyses that have compared test-and-treat with prompt endoscopy,34 as well as test-and-treat with empirical antisecretory therapy.30 Access to full data sets enables the meta-analyses to be performed with the individual data of each patient rather than with pooled data, thus increasing the reliability of the results.

(1) Test-and-treat vs. prompt endoscopy

The individual patient data meta-analysis performed by Ford et al.34 (including almost 2,000 patients) identified five RCTs comparing prompt endoscopy with test-and-treat. Prompt endoscopy conferred a small but statistically significant benefit on symptoms: the relative risk of symptoms persisting at 12 months was 0.95 (95% confidence interval (CI), 0.92–0.99). In terms of cost-effectiveness, test-and-treat cost $389 less per patient. Using the net benefit approach, prompt endoscopy did not become cost effective at any realistic level of willingness to pay per patient free of symptoms at the end of follow-up.

This individual patient data meta-analysis clarified the issues left unresolved by the original Cochrane review.35 The principal difference between the trial-based meta-analysis and that based on individual patient data are that the former found no significant differences in symptom outcome between the two strategies, although significant heterogeneity was observed and the confidence intervals were wide. The individual data-based meta-analysis included cost data, and heterogeneity between trials was reduced, thus allowing the emergence of a small but significant difference in the effect.34

The first conclusion of this individual patient data meta-analysis was that prompt endoscopy confers a small benefit in terms of cure of dyspepsia. One explanation for this benefit may be the reassurance effect of normal endoscopy, an effect that has often been claimed but never proved and that—if it truly exists—seems to be quite short lived.34 In addition, the trials were unblinded, and the possibility that this might have led to a bias in favor of endoscopy cannot be excluded.34 Furthermore, prompt endoscopy was generally associated with testing for H. pylori and treatment if positive; therefore, some of the benefits of this strategy may in fact be due to eradication of the infection. Finally, it should be noted that large meta-analyses have the power to detect small differences in effect that, although statistically significant, may have little clinical relevance.34 Thus, the difference in effect was small (relative risk of 0.95), and the statistical significance was borderline (95% CI from 0.92 to 0.99).

The second conclusion of the meta-analysis was that the cost of prompt endoscopy as a first-line approach for the management of dyspepsia in patients without alarm symptoms is prohibitive in everyday clinical practice, with the result that a test-and-treat strategy should be preferred.34

(2) Test-and-treat vs. empirical antisecretory therapy

The second individual patient data meta-analysis performed by Ford et al.30 pooled data from three RCTs comparing test-and-treat with empirical acid suppression in >1,500 patients. No significant differences were found in symptoms at 12 months of follow-up. This meta-analysis, however, might be biased both by including the unreliable study by Duggan et al.24 and by excluding a well-performed RCT from Manes et al.27 because it was performed in secondary care. In addition, a detailed analysis raises additional concerns over the validity of the conclusions of the meta-analysis: the study by Delaney et al. was performed in an area of very low prevalence of H. pylori infection: only 100/265 patients were positive for H. pylori and the infection was finally cured in only 57/265. Finally, although the primary end point analysis in the study by Jarbol et al.28 was negative, the secondary end point analysis showed that patients who received eradication therapy had significantly fewer days with dyspeptic symptoms at 12 months, used less antisecretory therapy, and were more satisfied with their management. Therefore, although this particular meta-analysis concludes that for the initial management of dyspepsia, test-and-treat and empirical PPI therapy perform equally well in terms of symptom resolution, this conclusion may not be applicable everywhere. A more detailed analysis of data strongly suggests that the test-and-treat strategy overcomes empirical PPI therapy for control of symptoms and that the benefit increases as the prevalence of H. pylori increases in the dyspeptic population. Finally, the strategy assigned reduced subsequent dyspepsia-related costs among those randomized to test-and-treat compared with those allocated to empirical PPI therapy, although the difference was relatively small and did not achieve statistical significance. As commented on above, this saving could increase further with a longer duration of follow-up.30

PROSPECTIVE STUDIES (NOT RCTS)

Prospective studies, with different designs from those of RCTs, have also evaluated the test-and-treat strategy. Of note, very few studies have prospectively evaluated the test-and-treat strategy, and those that did generally included a limited number of patients. Thus, only a few large-scale studies in a real-life setting are available.

Moayyedi et al.36 compared the proportion of endoscopies carried out in patients aged <40 years during the 5 years before and 2 years after the introduction of a screening and treatment strategy at population level. The authors recorded a 37% reduction in open-access endoscopy performed following the introduction of the 13C-urea breath test service. Six months after attending the 13C-urea breath test service, a significant fall in dyspepsia score, general practice dyspepsia consultations, and H2 receptor antagonist prescription was observed, indicating that H. pylori screening and treatment strategy reduced endoscopy workload.

Joosen et al.37 identified health outcomes and the costs and savings generated using an H. pylori test-and-treat strategy in 184 patients taking chronic acid suppressants. Significant symptom relief and improvements both in health benefits and cost savings were observed in the intervention group (test-and-treat strategy).

Madisch et al.38 investigated the outcome of H. pylori eradication in staff members with uninvestigated chronic dyspepsia in a large factory in a prospective, open-label, controlled, workplace outcome study after 1 year of follow-up of dyspepsia, and quality of life. H. pylori status was assessed using the 13C-urea breath test in 267 individuals with dyspepsia. At 12 months, 42% of responders showed complete relief of epigastric pain compared with 9.2% in the reference untreated group. Furthermore, disease-related absence from work, visits to family physicians, and antacid consumption decreased significantly in responders compared with reference subjects.

Farkkila et al.39 performed a population-based study evaluating the effectiveness and safety of the test-and-treat strategy in real-life primary care settings. Dyspeptic patients (N=1,552) aged between 25 and 60 years with no alarm symptoms were recruited. After screening with a 13C-urea breath test, H. pylori-positive patients received eradication therapy, whereas H. pylori-negative patients were treated with omeprazole. The authors concluded that, when applied in real life, the test-and-treat strategy failed to reduce the number of endoscopies, but significantly reduced peptic ulcer disease and improved dyspeptic symptoms and quality of life.

Gisbert et al.40 prospectively evaluated the effectiveness of the test-and-treat strategy in a large group of dyspeptic patients in clinical practice. Of the initial 736 patients, 422 received eradication therapy and 314 symptomatic therapy. At 6 months, symptoms improved in 66% of patients (in 73% of patients receiving eradication therapy and in 54% of those receiving symptomatic therapy).

DECISION ANALYSIS AND ECONOMIC MODELS

The gold-standard evidence of effectiveness for a clinical practice guideline is the RCT, although these studies have a limited ability to explore potential management strategies for a chronic disease where these interact over time. Modeling can be used to fill this gap. Decision analysis is a quantitative method for estimating the financial costs and clinical outcomes of alternative management strategies under conditions of uncertainty.41 Decision analysis explicitly states alternative treatment choices, specifies the assumptions made in the analysis of the clinical problem, distinguishes between the probability of the occurrence of outcomes and the utilities associated with these outcomes, and provides quantitative estimates of each outcome. The most important factor in these models is the percentage of patients in the H. pylori test-and-treat group undergoing endoscopy during follow-up,32 which could be as low as 10% or as high as 40%, with 30% being the best estimate.32

Data on cost-effectiveness of the test-and-treat strategy for H. pylori in dyspepsia have been gathered in several recent analyses and were reviewed by Di Caro et al.42 We have updated these data (Table 3).32, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 In summary, most of the decision analysis and economic models confirm test-and-treat to be better than prompt endoscopy.32, 43, 46, 47, 49, 50, 52, 57, 60 The preference for the test-and-treat strategy over empirical antisecretory therapy is also suggested by most of the economic models (Table 3).43, 45, 47, 51, 52, 53, 55

Table 3. Cost-effectiveness studies evaluating the test-and-treat strategy.

| Author | Design | Strategies compared | Measured outcome | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barton et al.43 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat vs. empirical acid suppression vs. initial endoscopy | Cost effectiveness, QALYs, and costs | Endoscopy was dominated at all ages by other strategies. PPI therapy was the most cost-effective strategy in 30-year olds with a low prevalence of H. pylori. In 60-year olds, H. pylori test-and-treat was the most cost-effective option |

| Chey et al.44 | Decision analysis model | Antibody testing or testing to detect active H. pylori infection (active testing) | Appropriate and inappropriate treatment, cost per patient, incremental cost per unnecessary treatment avoided | Active testing led to a substantial reduction in unnecessary treatment for patients without active infection (antibody 23.7% active, 1.4% patients) at an incremental cost of $37 per patient |

| Chiba et al.45 | Corrected alpha percentile bootstrap method | Test-and-treat vs. PPI | Cost per patient (direct and indirect costs) | The annual saving per patient, calculated for each increment of change in global overall symptoms, was CDN$54 |

| Fendrick et al.46 | Decision analysis model | Two immediate endoscopy and three non-invasive diagnostic and treatment strategies | Cost per ulcer cured and cost per patient treated | The predicted costs per patient treated were as follows: (1) endoscopy and biopsy for H. pylori, $1,584; (2) endoscopy without biopsy, $1,375; (3) serology test for H. pylori, $894; (4) empirical antisecretory therapy, $952; and (5) empirical antisecretory and antibiotic therapy, $818 |

| Fendrick et al.47 | Decision analysis model | Immediate endoscopy vs. empirical treatment with antisecretory therapy and serology testing for H. pylori | Cost per ulcer cured over a 1-year study period | The most cost-effective strategy was the test-and-treat strategy with $4,481 cost per ulcer cured. The immediate endoscopy strategy resulted in a cost of $8,045 per ulcer cured |

| García-Altés et al.48 | Decision analysis model | Prompt endoscopy, score and scope, test and scope, test-and-treat, and empirical antisecretory treatment | Direct cost of each management strategy | Endoscopy was the most effective strategy for the management of dyspepsia. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios showed that score and scope was the most cost-effective alternative (€483 per asymptomatic patient), followed by prompt endoscopy (€1,396) |

| Gee et al.49 | Cost analysis in a breath test service | Test-and-treat vs. endoscopy | Cost of each management strategy | Referral to the breath test service costs £84.67 per dyspeptic patient; referral for endoscopy costs £98.35 per patient |

| Klok et al.50 | Economical evaluation of a randomized clinical trial | Test-and-treat vs. prompt endoscopy | Health-care costs and quality of life | The total costs per patient were €511, with 0.037 QALY gained per patient in the test-and-treat group, and €748, with 0.032 QALY gained per patient in the endoscopy group. The test-and-treat strategy yielded cost savings and QALYs gained |

| Labadaum et al.51 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat strategy vs. 1-month PPI | Health-care utilization (cost per patients treated) | The cost per patient treated differs little between the two non-invasive strategies analyzed ($545 for the test-and-treat strategy vs. $529 with PPI), while both achieve similar clinical outcomes. |

| Makris et al.52 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat vs. endoscopy vs. empirical antisecretory treatment vs. empirical eradication treatment | Costs, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness ratios | Endoscopy was not a cost-effective approach. Of the non-invasive test-and-treat strategies, using the breath test was the most effective and most costly strategy ($8,238 per additional patient cured) compared with laboratory serology. |

| Marshall et al.53 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat vs. empirical ranitidine | Direct medical costs and effectiveness in curing H. pylori-related ulcers | Breath test was more costly than either serology or ranitidine, but was the most effective strategy and required the fewest endoscopies. No strategy demonstrated dominance over another in the base case. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of serology vs. ranitidine was $118/cure |

| Mason et al.54 | Markov model from large randomized controlled trial data | Test-and-treat vs. placebo | Life years saved/population screening and intervention | Population test-and-treat would save more than £8,450,000 and 1,300 life-years per million people screened |

| Moayyedi et al.55 | Markov model from systematic review of randomized controlled trials | Test-and-treat vs. 1 month of antacids | No. of months of symptom remission | Test-and-treat favored vs. antacids |

| Moayyedi et al.32 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat vs. initial endoscopy | Costs effectiveness | H. pylori test-and-treat strategy is the most cost-effective method for managing dyspepsia, costing US $134 per patient per year compared with US $240 per patient per year for prompt endoscopy. The prompt endoscopy strategy only becomes cost effective in the unlikely scenario of endoscopy costing US$160, the non-invasive test costing US$80, and an H. pylori prevalence of <20% |

| Ofman et al.56 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat vs. initial endoscopy in patients who are seropositive for H. pylori | Costs per patient | Initial endoscopy costs an average of $1,276 per patient, whereas initial anti-H. pylori therapy costs $820 per patient; the average saving is $456 per patient treated. The financial effect of a 252% increase in the use of antibiotics for initial H. pylori therapy is more than offset by reducing the endoscopy workload by 53% |

| Silverstein et al.57 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat vs. endoscopy vs. empirical antisecretory treatment | Direct medical charges in the first year after the onset of dyspepsia | Medical care charges were $2,162.50 for initial endoscopy and $2,122.60 for empirical therapy, a difference of 1.8%. Empirical therapy has lower costs than initial endoscopy when H2-receptor antagonists are used to prevent recurrence of dyspepsia. Initial non-invasive testing for H. pylori has lower costs than initial endoscopy if patients with dyspepsia and H. pylori infection receive antimicrobial therapy without endoscopy |

| Sonnenberg et al.58, 59 | Decision analysis model | Serology testing vs. initial endoscopy | Cost–benefit relationship of serology testing for H. pylori | A response to eradication of H. pylori in 5–10% of all patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia would make screening and treatment for H. pylori a beneficial option, irrespective of any other potential benefits. If ulcer prevention were associated with a long-term benefit of $4,000 or more and if the ulcer prevalence rate exceeded 10% of all dyspeptic patients, serology testing for H. pylori would also pay off |

| Spiegel et al.60 | Decision analysis on a hypothetical cohort | Less invasive strategies (with either test-and-treat or PPI as first choice) vs. more invasive approaches | Proportion of symptom-free patients and QALY | Less invasive strategies (with either test-and-treat or PPI initial approach) preferred over more invasive strategies. Starting with test-and-treat had cost-effectiveness of $1,714/QALY and $2,007/symptom-free patient at 1 year |

| Vakil et al.61 | Decision analysis model | Test-and-treat vs. endoscopy vs. empirical H. pylori treatment | Costs | Costs were very similar for both endoscopy ($643) and serology ($646) in the USA. In Finland, endoscopy ($173) was less expensive than serology ($192). Empirical treatment of children with dyspepsia was not cost effective in either country. Sensitivity analysis showed that when prevalence of infection was >53%, empirical therapy was the optimal approach |

Abbreviations: PPI, proton pump inhibitor; QALY, quality adjusted life year.

Despite the usefulness of cost-effectiveness studies, decision analysis is based on numerous assumptions with regard to costs and benefits, and the probability of various medical states is extracted from the literature or estimated by expert opinion. All estimates reflect practice in a particular geographic area and cannot be extrapolated to other countries, and, therefore, decision analysis cannot and must not replace a good prospective design.62

Finally, two individual patient data meta-analyses compared test-and-treat with prompt endoscopy34 and test-and-treat with empirical antisecretory therapy.30 In the first meta-analysis, a small but statistically significant improvement in symptoms at 12 months was demonstrated for endoscopy (around 5% of patients),34 but the cost was around €172 more per patient treated than test-and-treat. A cost effectiveness analysis demonstrated that at a realistic willingness to pay per symptom-free patient at 12 months (€1,070), prompt endoscopy was not cost effective for the initial management of uninvestigated dyspepsia. In the second meta-analysis, no significant differences in symptoms or costs were demonstrated at 12 months of follow-up, although a trend was observed toward a net cost saving with test-and-treat; most of the saving was the result of a reduction in subsequent investigations.30

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES AND CONSENSUS CONFERENCE STATEMENTS

The 1994 NIH Consensus Panel Statement implicitly endorsed a strategy of documenting the presence of both ulcer and H. pylori infection before eradication therapy,63 thus requiring increased invasive diagnostic testing before treatment could be prescribed. Moreover, at the 1998 conference of the American Digestive Health Initiative, the panel concluded that, based on available data, testing for and treating H. pylori infection had not been adequately investigated in terms of effectiveness, symptom relief, patient satisfaction, and cost.64

More recently, the 2004 guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom also reflected this uncertainty, advocating the use of either test-and-treat or empirical acid suppression owing to a lack of available evidence demonstrating which is superior.65

Similarly, the 2005 guidelines of the American College of Gastroenterology66 concluded that, in patients aged 55 years or younger with no alarm features, the clinician can choose between one of two approximately equivalent management options: (i) test-and-treat for H. pylori using a validated non-invasive test followed by a trial of acid suppression if eradication is successful but symptoms do not resolve; or (ii) an empirical trial of acid suppression with a PPI for 4–8 weeks. The test-and-treat option was shown to be preferable in populations with a moderate-to-high prevalence of H. pylori infection (≥10%), whereas the empirical PPI strategy is preferable in populations with a low prevalence.

The 2007 American College of Gastroenterology Guideline on the Management of Helicobacter pylori Infection stated that “the test-and-treat strategy for H. pylori infection is a proven management strategy for patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia who are under the age of 55 years and have no alarm features”.67

The use of the test-and-treat strategy was also advocated at the European Consensus Meeting held in Maastricht in 2005,68 although this recommendation was classified as “advisable” by most of the participants, but not unanimously, and the strength of supporting evidence was classed as “equivocal”. More recently, at the last Maastricht Consensus Conference held in 2010, it was stated that “a test-and-treat strategy is indicated for uninvestigated dyspepsia in populations where the H. pylori prevalence is high (>20%)”.69 On this occasion, the evidence level was classified as “A” (the highest) and the strength of the recommendation as “1a” (again, the highest).

AGE THRESHOLD AT WHICH TEST-AND-TREAT IS APPLIED

Although non-invasive H. pylori testing seems increasingly preferable to endoscopy when determining the management of younger patients presenting with dyspepsia, the possibility that this approach may result in missing potentially curable malignancy gives cause for concern, and the age at which endoscopy is advisable to exclude underlying upper gastrointestinal malignancy remains uncertain.70 In fact, as no randomized controlled data support or refute a specific age cutoff, this arbitrary assignment remains based on expert opinion. The age threshold at which available management guidelines recommend prompt endoscopy for uninvestigated dyspepsia varies from 45 to 55 years in Western Europe and North America (Tables 1 and 2). This is the age at which the incidence of upper gastrointestinal malignancy begins to increase significantly,71, 72 although in some Eastern European and Asian countries a lower threshold is used, owing to the higher prevalence of gastric cancer.73 Thus, the age cutoff point depends on local incidence of gastric cancer in different age groups.69

Initially, the American Gastroenterology Association, the American College of Gastroenterology, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, the British Society of Gastroenterology, and the European Society of Primary Care Gastroenterology recommended endoscopy for patients aged over 45 years.74, 75, 76, 77 More recently, a test-and-treat strategy with an age threshold set at 50 years has been validated in primary care.78, 79 Accordingly, some authors and the Canadian Dyspepsia Working Group have recommended setting the age threshold at 50 years.80, 81, 82, 83, 84

Gillen and McColl85 assessed whether concern over occult malignancy is valid in patients aged <55 years presenting with uncomplicated dyspepsia by reviewing the case notes of patients aged <55 years who had presented with esophageal or gastric cancer. Upper gastrointestinal malignancy was extremely rare in patients <55 years presenting with uncomplicated dyspepsia and, when found, was usually incurable. Consequently, this study suggests that concern about missing underlying curable malignancy is not a valid reason for recommending endoscopy in this population. Similar results have been obtained by other authors.20, 71, 86

The updated British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines suggested an age threshold of 55 years for endoscopy.87 Similarly, the Guidelines developed under the auspices of the American College of Gastroenterology66 recommended setting the cutoff point at 55 years, and the American College of Gastroenterology Guideline on the Management of Helicobacter pylori Infection stated that “the test-and-treat strategy for H. pylori infection is a proven management strategy for patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia who are under the age of 55 years and have no alarm features”.67

Finally, a recent study showed that the test-and-treat strategy turned out to be a safe method for managing uninvestigated dyspepsia in primary health care, even when applied in patients aged up to 60 years of age.39

Some observations suggest that age appears to be a poor predictor of underlying pathology.88 In this respect, age was not even considered in two relevant studies evaluating the test-and-treat strategy, while only the presence of alarm symptoms was taken into account.19, 45 It was noteworthy that none of the patients included in the test-and-treat strategy in these studies was diagnosed with cancer during follow-up.19, 45 Accordingly, the NICE in the United Kingdom issued a guideline recommending that all dyspeptic patients without alarm symptoms, irrespective of age, should be managed initially without endoscopy (but with PPI therapy for 1 month).87

In summary, although convincing data supporting a specific age cutoff for endoscopy are lacking, and therefore the decision remains somewhat arbitrary, setting the age threshold at 50 or even 55 years (rather than 45 years) seems reasonable in the USA and in most Western European countries, because cancer is rare in younger patients.89 However, the age at which endoscopy is required in patients with new-onset dyspepsia depends on geographic region and patient population.82

COST AND AVAILABILITY OF ENDOSCOPIC EXAMINATION

The cost of endoscopy ranges widely from one country to another, thus considerably affecting the cost–benefit relationship of the test-and-treat strategy. By using sensitivity analysis, decision analyses can vary assumptions about probabilities and utilities and determine their impact on outcomes. Thus, for example, Silverstein et al.57 evaluated initial endoscopy and testing for H. pylori in the management of dyspeptic patients. The analysis favored non-invasive strategies when the estimated cost of endoscopy was US$500; however, if endoscopy cost <$277, initial endoscopy was the least costly strategy. Fendrick et al.46 compared two invasive and three initially non-invasive strategies and concluded that an initial non-invasive strategy including H. pylori eradication therapy in infected patients was the most cost-effective approach; however, when the cost of endoscopy was <$500, the strategies were equally cost-effective. Furthermore, the cost of endoscopy is not uniform around the world; in the United States it was particularly high but is decreasing, and many models suggest that when the procedure costs <$500, early endoscopy may become a cost-effective alternative. When the cost is <$200, initial endoscopy becomes the intervention of choice in all of the models.84

Use of endoscopy is also affected by availability; thus, empirical treatment of H. pylori infection is probably preferable when access to prompt upper endoscopy is limited. For example, bearing in mind the limited health resources in the Asia-Pacific region, it would be prudent to adopt an H. pylori test-and-treat strategy as the initial management approach for young Southeast Asian patients.23 In addition, long waiting lists may decrease the diagnostic efficacy of endoscopy, thus favoring non-invasive strategies.

PREVALENCE OF H. PYLORI INFECTION IN PATIENTS WITH DYSPEPSIA

The prevalence of the infection changes the predictive value of the diagnostic method.90 When infection is frequent, the pretest probability of H. pylori infection increases; for example, in developing countries or in patients with H. pylori-related diseases such as duodenal ulcer, the predictive value of a negative diagnostic test markedly decreases and, consequently, the number of false-negative results increases. In other words, the higher the baseline prevalence of H. pylori, the less confident one should be about a negative test result.90 Furthermore, in populations in which H. pylori is highly prevalent, some infected patients with a gastroduodenal ulcer will not receive eradication therapy because of false-negative results. False-positive results in these settings are exceedingly rare, and a positive result does not need confirmation and mandates treatment. On the other hand, the lower the prevalence of H. pylori (for example, in developed countries), the lower the positive predictive value (i.e., more false-positive results); test-and-treat must be used cautiously in low-prevalence populations, as non-invasive tests become less accurate in this setting.91 The main problem in this case is that many uninfected patients will be inadequately treated with antibiotics.

Where local prevalence of H. pylori is known to exceed 10%92 or 20%,68 test-and-treat is recommended.33, 69 In contrast, PPI treatment was consistently less costly than test-and-treat when the prevalence of H. pylori was <10–20%.51 Therefore, in all settings, it seems important to consider the findings of epidemiologic studies evaluating the prevalence of H. pylori in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia. It has been suggested that in many parts of Europe and North America, the prevalence of H. pylori infection and of peptic ulcer disease is declining to a point that may soon make test-and-treat-based strategies irrelevant.93, 94, 95 Although this finding may be true, it is based mainly on theoretical analyses and needs support from real-life data. Multinational clinical trials performed in areas with different H. pylori prevalence rates, but comparing identical strategies using identical protocols, would provide important data.95

In summary, the test-and-treat option is preferable in populations of dyspeptic patients with a moderate-to-high prevalence of H. pylori infection (≥10–20%), whereas the empirical PPI strategy may be preferable in low-prevalence populations.33, 66, 69, 92

TYPE OF DIAGNOSTIC METHODS TO DETECT H. PYLORI INFECTION

The three non-invasive methods that can be used for the test-and-treat strategy are serology, the 13C-urea breath test, and the stool antigen test. Although some serology tests have been reported to have high sensitivity and specificity, blood tests may perform differently in different geographic locations, probably because of variation in strains, suggesting that only locally validated tests should be used.96, 97 In general, serology should be considered less accurate than 13C-urea breath test and monoclonal stool antigen tests.69, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102

On the other hand, rapid (“office”) serology tests using whole blood could facilitate application of the test-and-treat strategy in general practice. However, these tests have not yet been approved,68 as the sensitivities and specificities observed to date have generally been disappointing.25 Duggan et al.103 evaluated the performance of a near-patient test for H. pylori infection in primary care, and found that the sensitivity of the FlexSure test was <70% thus, about one-third of infections were not detected. In another study,24 the same authors validated the near-patient serology test previously used in their trial and reported 69% sensitivity and 98% specificity; again, this low sensitivity may mean that about one-third of H. pylori-infected dyspeptic patients would have gone undetected and many peptic ulcers would have been missed.

Given the diagnostic performance limitations of serology tests and the clinical and economic consequences of applying suboptimal blood tests for H. pylori, some authors have questioned the rationale of using them in general practice, suggesting that the 13C-urea breath test is a better option.104 A recent economic study suggests that the test-and-treat strategy using the 13C-urea breath test is more cost effective than test-and-treat using serology.105

Stool tests may also be valid as non-invasive tests.69 McNulty et al.106 explored the views of primary care about introducing the H. pylori test-and-treat strategy and found that staff preferred stool tests to breath tests, as they impacted less on practice budget and time. On the other hand, stool antigen testing may be somewhat less acceptable to patients.

During the last few years, new formats of the stool antigen test using monoclonal antibodies ensure constant antigen composition and, therefore, similar diagnostic reliability in the different kits of the same test. For this reason, monoclonal tests are far more reliable that tests based on polyclonal antibodies, where antibody composition could change from one kit to another. The two formats available are: (1) laboratory tests (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), and (2) rapid office tests using an immunochromatographic technique. A meta-analysis of 22 studies including 2,499 patients showed that laboratory stool antigen tests based on monoclonal antibodies are highly accurate in both initial and post-treatment diagnosis of H. pylori.98 In contrast, the rapid office tests were less accurate.107, 108 Therefore, when a stool antigen test has to be used, the recommendation is for an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay format with a monoclonal antibody as the reagent.69

A disadvantage of both the breath test and stool antigen test is that, in contrast with serology, patients must stop taking PPIs for at least 2 weeks before testing.14, 109 Furthermore, antibiotics must be stopped at least 4 weeks before.

In summary, as part of the test-and-treat strategy, the 13C-urea breath test remains the best approach to diagnosis of H. pylori infection, as it is highly accurate and easy to perform.99 Stool antigen testing may be somewhat less acceptable to patients in some cultures but is equally valid with high sensitivity and specificity provided a monoclonal antibody-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay is used.110

PROPORTION OF H. PYLORI-POSITIVE PATIENTS WHO HAVE OR WHO WILL DEVELOP PEPTIC ULCER, AND PROPORTION OF ULCERS ATTRIBUTABLE TO H. PYLORI

Patients with peptic ulcer disease represent the population that most clearly benefits from eradication of H. pylori, as eradication of the organism is associated with a high ulcer cure rate, a very low ulcer recurrence rate, a protective effect against complications of ulcer, and a reduction in costs.111, 112 Test-and-treat leads to resolution of symptoms in <50% of uninvestigated infected dyspepsia patients, the poor results being related to the relatively small percentage of patients with peptic ulcer disease and to the small benefit of eradication of H. pylori in patients with functional dyspepsia (see next section).113 According to sensitivity analyses, test-and-treat is favored in geographical areas where the prevalence of ulcer or H. pylori infection, which usually occur simultaneously, are high, whereas empirical antisecretory therapy is favored when prevalence rates are low.

Sonnenberg et al.58 analyzed the outcome of serology testing for H. pylori in dyspepsia using a decision analysis and found that the cost–benefit relationship of this approach was considerably influenced by the prevalence rate of peptic ulcer in H. pylori-positive patients; thus, if the prevalence of ulcer exceeded 10% of all dyspeptic patients, serology testing for H. pylori would be cost effective. Similarly, other authors have reported that when the prevalence of peptic ulcer is low (<12%), empirical antisecretory therapy would be the most cost-effective strategy.114 The proportion of H. pylori-positive individuals with an active ulcer at the time of endoscopy remains unclear, but published figures range from <5% to >30%.115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122 In patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia, the prevalence of peptic ulcer is around 20%, that is, about one-third of H. pylori-positive dyspeptic patients,123 again showing that the test-and-treat strategy remains cost effective in most settings. With regard to the number of H. pylori-positive asymptomatic individuals who will develop an ulcer, the infection has been described as a risk factor for the development of peptic ulcer.122, 124, 125 Thus, the estimated lifetime risk for the development of peptic ulcer in asymptomatic patients infected by H. pylori ranges from 10 to 20%.126

H. pylori infection rates in patients with peptic ulcer disease are still very high, although they may be lower than in previous estimations.127 A recent systematic review of studies published during the last 10 years including 16,080 patients calculated a mean prevalence of H. pylori infection of “only” 81% in duodenal ulcer disease; this figure was even lower (77%) when only the last 5 years were analyzed. In truly H. pylori-negative patients, the most common single cause of ulcer is, by far, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (patients taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are excluded from the test-ant-treat strategy, as endoscopy is generally recommended). Ulcers not associated with H. pylori, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or other obvious causes should, for the present, be viewed as idiopathic. However, true idiopathic duodenal ulcer disease is exceptional.127

ROLE OF H. PYLORI IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF GASTRIC CANCER

The risk of gastric adenocarcinoma attributable to H. pylori has been estimated to be between 35 and 60%128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134; in addition, H. pylori infection increases sixfold the risk of having this cancer.135 Several years ago, the WHO classified the relationship between H. pylori and gastric adenocarcinoma as category I, which implies that the microorganism is considered a proved carcinogenic factor.136 Further evidence linking gastric adenocarcinoma to H. pylori infection has accumulated since then. Specifically, recent studies have shown that strains with increased CagA activity are associated with a relevant high risk of gastric cancer.137, 138 Different harmful capabilities of the individual H. pylori strains may explain why only a proportion of infected patients develop malignancy.139, 140, 141, 142, 143 It is now widely accepted that early eradication of H. pylori (before mucosal preneoplastic changes such as gastric atrophy or, mainly, intestinal metaplasia develop) is effective in preventing gastric adenocarcinoma; in addition, screening and treatment of H. pylori infection is strongly recommended in high-risk populations.144

H. pylori is also considered the main causal factor of low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas of the stomach.145, 146 As is the case with gastric adenocarcinoma, only a reduced proportion of infected patients will develop mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma; therefore, it can be deduced that factors other than the organism have an important role in this disease.145, 146, 147, 148 Nevertheless, although H. pylori could be responsible for approximately two-thirds of gastric lymphomas,149 it is evident that H. pylori is—again—not sufficient for the development of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. However, it is probably the most relevant and the most easily avoidable risk factor (by eradication).

Widespread population screening and eradication of H. pylori has the potential to reduce the incidence of gastric cancer (both adenocarcinoma and lymphoma), although further large-scale studies are warranted.150, 151 In addition to curing symptoms, test-and-treat strategies in young patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia are also likely to decrease the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma and aid the management of these important public health issues.150

ROLE OF H. PYLORI IN FUNCTIONAL DYSPEPSIA

Functional dyspepsia is defined according to the Rome III criteria as the presence of symptoms thought to originate in the gastroduodenal region, in the absence of any organic, systemic, or metabolic disease that is likely to explain the symptoms.15 This implies that H. pylori infection needs to be excluded (and/or treated) before a diagnosis of functional dyspepsia can be reached.152

The potential role of H. pylori in functional dyspepsia is very relevant, as most patients will be included in this symptomatic group.115, 116 No relationship has been established between H. pylori and functional dyspepsia153, 154, 155 for the following reasons: (i) a higher prevalence of the infection in functional dyspepsia patients has not been universally reported; (ii) a close correlation between H. pylori status and a particular symptomatic pattern has not been observed; (iii) the organism does not seem to induce changes in gastrointestinal motility; and, most importantly, (iv) although some studies have shown an improvement in symptoms after eradication of H. pylori,156 others have not.157

However, although H. pylori does not seem to be the cause of functional dyspepsia, most studies and several meta-analyses show that a small proportion of patients with functional dyspepsia experience a long-term improvement in their dyspeptic symptoms after cure of H. pylori infection. As the course of peptic ulcer disease alternates between flares and remission periods, and endoscopy between flares could be normal, it may well be that eradication of H. pylori benefits functional dyspepsia by curing the small proportion of patients with peptic ulcer disease who go undetected during the diagnostic work-up. To date, several meta-analyses and systematic reviews examining the effect of eradicating H. pylori on improvement in dyspeptic symptoms have been published.55, 157, 158, 159, 160 The number-needed-to-treat (to cure one dyspeptic patient with eradication therapy) has been calculated to be 13 [ref. 161]. Although this effect is modest, it is important to highlight that the benefits of eradicating H. pylori seem to persist at least 1 year after treatment; therefore, this approach is cost effective in patients with functional dyspepsia and H. pylori infection.55 Eradication is cost effective despite the low number of responders, because treatment alternatives are even poorer. In this sense, although the number-needed-to-treat for PPI therapy (the other effective treatment for functional dyspepsia) is better (about nine), these drugs are limited by their very transient effect, and symptoms tend to recur early after treatment.162

Sonnenberg et al.58 suggested that the benefit to patients with functional dyspepsia after eradication of H. pylori may be a key factor in support of test-and-treat. The authors analyzed the outcome of serology testing for H. pylori in dyspepsia using a decision tree and found that, if the response rate of functional dyspepsia to H. pylori eradication is >5–10% of all patients, the test-and-treat strategy becomes highly cost effective, even if we do not take into account any of the other potential benefits of the test-and-treat strategy.

EFFICACY, COST, AND ADVERSE EFFECTS OF H. PYLORI ERADICATION THERAPY

The efficacy, cost, and adverse effects of eradication therapy must be taken into account, as treatment will be administered to a considerable number of patients if the test-and-treat strategy is followed. To date, the most widely recommended treatment for the eradication of H. pylori in international guidelines is the so-called standard triple therapy, which combines two antibiotics (clarithromycin plus amoxicillin or metronidazole) with a PPI for 7–14 days. However, since the micro-organism was discovered, the eradication rate has fallen considerably with this regimen,163 thus increasing the need for alternative treatment strategies (e.g., bismuth-containing quadruple therapy164 and non-bismuth quadruple sequential and concomitant regimens).165, 166 The cost–benefit ratio of test-and-treat strategies should increase if eradication therapies reach close to 100% efficacy, costs decrease, and the safety profile improves.

Adverse effects associated with eradication regimens are not problematic in clinical practice, as tolerance of the above-mentioned therapies is rather good and severe side effects are extremely rare. Nevertheless, even if the incidence of adverse effects is very low, the prescription of eradication therapy for a large number of patients will be followed by a significant number of antibiotic-related adverse effects.167

Furthermore, the emergence of resistance by H. pylori will complicate the test-and-treat strategy.167 Resistance to metronidazole and to clarithromycin is already a relevant therapeutic problem,168, 169 and, more importantly, resistance rates (especially to clarithromycin) seem to be increasing in parallel with the progressive increase in antibiotic prescription.168, 169, 170 In this sense, some authors fear that test-and-treat strategies will widen the problem of community-acquired antibiotic resistance, even against micro-organisms other than H. pylori. However, the estimated level of inappropriate antibiotic prescription in primary care is extremely high (1.43 prescriptions per person per year). In this scenario, a test-and-treat strategy for uninvestigated dyspepsia patients—apart from being a correct indication for antibiotic therapy—will have a negligible impact on community antimicrobial resistance rates.32, 171

RISK OF MISSING SERIOUS DISEASES

Although delayed diagnosis of gastric cancer resulting from an empirical trial of therapy or the test-and-treat strategy for H. pylori has not been shown to adversely affect outcomes, concern remains.172, 173, 174 The risk will be minimized by restricting this strategy to young patients (see corresponding section for the recommended age threshold) without alarm symptoms.175 In this respect, upper gastrointestinal malignancy is extremely rare in patients <55 years presenting with uncomplicated dyspepsia; and when found, it is usually incurable.85 Furthermore, only a small proportion of young gastric cancer patients present without alarm symptoms and, as dyspepsia associated with gastric cancer is less responsive to empirical therapy, such patients would be investigated eventually, as their symptoms fail to respond.176 Finally, despite the delay in diagnosis, patients with gastric cancer and no alarm symptoms have a better outcome than those with alarm symptoms. Thus, the diagnostic delay in patients without alarm symptoms does not seem to affect survival.177

The test-and-treat strategy has been compared with prompt endoscopy in eight RCTs including 1,438 patients.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 Three upper gastrointestinal malignancies were detected at subsequent endoscopy in the test-and-treat arms of these trials, and three in the prompt endoscopy arms, with no significant diagnostic delay as a result of assignment to a test-and-treat strategy in any of these patients.33

Obviously, the presence of alarm symptoms should prompt investigation to rule out severe disease.178, 179 However, alarm symptoms appear to be a poor predictor of underlying pathology.88, 180 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis that evaluated the accuracy of alarm features in the diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal malignancy, demonstrated that the positive predictive value of these symptoms was disappointingly low. Therefore, more efficient ways of predicting which individuals with dyspepsia are likely to have gastroesophageal malignancy are required.72

Finally, management of dyspepsia might differ between countries.181, 182 The incidence of upper gastrointestinal malignancy is significantly higher overall in China than in Western countries.181 For example, Li et al.181 showed that if the H. pylori test-and-treat strategy were used in dyspeptic patients under the age of 45 years without alarm symptoms in the Shanghai region, then, based on the results of a recent study, 13 of the 162 gastric cancers found in a population of 14,101 patients undergoing endoscopy would be missed. The authors concluded that the test-and-treat strategy is not suitable for the management of patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia in Shanghai, and that for most dyspeptic patients living in this area, prompt endoscopy should be recommended as the first-line initial management option.181, 183

ENDOSCOPY OR EMPIRICAL PPI AFTER FAILURE OF TEST-AND-TREAT

The cost-effectiveness of test-and-treat may be further improved by treating non-responding symptoms (despite H. pylori eradication) with an empirical trial of PPI therapy, rather than by immediately referring patients for endoscopy.84 This strategy has been recommended by international guidelines.15, 66 A recent decision analysis model found that a strategy consisting of initial test-and-treat for H. pylori followed by empirical PPI therapy in non-responders and endoscopy only for patients with persistent dyspeptic symptoms may be more cost effective than test-and-treat or empirical antisecretory therapy alone.60 In summary, when treatment fails despite eradication of H. pylori, a trial with PPI therapy is a reasonable next step. However, head-to-head management trials will be needed to confirm these conclusions.

PATIENT SATISFACTION

Patient satisfaction has not been incorporated into the analysis of the test-and-treat strategy, as it is a difficult concept to model. Many dyspeptic patients presenting for medical care have a fear of serious disease and malignancy.184 In addition, they are more anxious than non-presenters with similar complaints.185 A completely normal endoscopy could relieve some patients of their anxiety. Perhaps because of this, patients undergoing endoscopy were more satisfied with the investigation than patients randomized to the H. pylori test-and-treat strategy.32 Endoscopy is technically more complicated and expensive, and patients may therefore perceive endoscopy as being “better”, even if there is no improvement in quality of life or dyspepsia compared with simpler investigation strategies.32 As accurately noted by Moayyedi,32 this is analogous to consumers preferring an expensively packaged product to an identical but less well marketed item.

FOLLOW-UP TIME

The long-term effect of the test-and-treat strategy is unknown. In fact, RCTs and simulation models have compared strategies with a 1-year perspective, although the long-term consequences are unknown. In particular, concerns have arisen over the safety and possible high costs of ongoing long-term PPI therapy in patients receiving empirical PPIs.186 Furthermore, postponing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in the short term has not been shown to lead to cancellation of the test in the long term. Patients who initially respond to testing-guided management strategies with recurrence of symptoms might eventually undergo endoscopy, long after the initial follow-up period has ended.187

As follow-up in most studies comparing prompt endoscopy with test-and-treat was limited to 12 months, it is uncertain whether the observed economic benefit of preferring test-and-treat is sustained in the long term. Fortunately, some studies have performed follow-up longer than 12 months. For example, Slade et al.188 initially reported that endoscopy can be avoided after performing the test-and-treat strategy and that this approach reduces endoscopic workload by 74%. More recently, in a 2-year long-term follow-up study of 232 participants from their previous trial, the severity of dyspepsia symptoms was lower than the initial scores at recruitment.189 Thus, 66% of the original participants were able to avoid endoscopy.

Laheij et al.187 compared the long-term results of empirical treatment followed by the H. pylori test-and-treat strategy (treat-and-test group) with the results of prompt endoscopy followed by targeted medical treatment (endoscopy group). The authors provided long-term follow-up data from a previously published RCT. At least 6 years after randomization, no differences were observed in symptom prevalence and quality of life between the groups. Furthermore, patients initially managed with a test-and-treat strategy required fewer additional diagnostic procedures and less long-term PPI treatment than those initially randomized to endoscopy. Thus, test-and-treat did not lead to additional diagnostic testing or use of medication when compared with prompt endoscopy. In particular, 6 years after randomization, 60% of patients who would normally have been referred for diagnostic testing but were instead managed by the treat-and-test strategy had not undergone upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.187

The study including the largest follow-up up to date was performed by Lassen et al.26 A total of 500 patients presenting in primary care with dyspepsia were randomized to management by H. pylori testing plus eradication therapy (n=250) or endoscopy plus eradication of H. pylori only in patients with duodenal or gastric ulcers (n=250). Symptoms, quality of life, and patient satisfaction were recorded over a 3-month period a median of 6.7 years after randomization. The authors reported that the lower rates of endoscopy and fewer prescriptions for acid suppression therapy observed at 12 months in those managed with a test-and-treat strategy persisted. Rates of dyspepsia remained comparable between the two arms of the trial, but the test-and-treat patient arm required less PPI maintenance therapy.26

SETTING OF TESTING (HOSPITALS OR GENERAL PRACTICE)

In theory, a test-and-treat strategy is best used in primary care as patients initially present to their general practitioner with dyspepsia. In addition, as many patients referred to hospital expect to undergo endoscopy, it is difficult to convince them that the procedure is not necessary. However, some of the studies on H. pylori management strategies analyze patients in hospital centers. Although the exact reasons leading patients to be referred to hospital are poorly understood, it has been suggested that patients referred to hospital may not represent the dyspeptic population seen in primary care.190, 191, 192 If, for example, H. pylori infection or peptic ulcer disease was less common in subjects not referred, the cost-effectiveness of the test-and-treat strategy would be less favorable in primary care.190 Nevertheless, although patients should ideally be recruited from primary care, as the trial results will be applied to this population,32 no published data support that uninvestigated dyspepsia patients behave differently in specialized or primary care. In fact, referral might reflect more the health-care system structure than true differences in patients' characteristics.

On the other hand, some authors have observed that the results of a test-and-scope strategy based on age and H. pylori status obtained from RCTs performed better in a referral center than in non-referral hospitals.193 Mahadeva et al.194 showed that a test-and-treat policy did not reduce endoscopy workload in a district (non-referral) hospital, suggesting that results from centers with interest in H. pylori research cannot necessarily be extrapolated to the vast majority (non-referral centers or general practice).

Finally, most published results were obtained from RCTs, and the results in carefully selected clinical trials may not reflect results of practice in the real world. Unfortunately, reports of clinical series evaluating the test-and-treat strategy in clinical practice—in contrast to RCTs—are very scarce. One exception is the TETRA study, which was performed in the outpatient setting, following the clinical practice of gastroenterologists in Spain.40 This large prospective study showed that test-and-treat was effective and safe for management of dyspeptic patients in clinical practice.

IMPLEMENTATION OF GUIDELINES IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

The impact of practice guidelines on patient care ultimately depends on their implementation by clinicians.195 Authors who explored the introduction of test-and-treat from the perspective of primary care found that primary care health staff reported that the major barrier to the introduction of NICE test-and-treat guidance for patients with dyspepsia was the time taken to give patients information on testing, test results, and treatment and the impact on nurses' time.106

Numerous strategies have been used to promote integration of clinical research findings into clinical practice, with passive dissemination of information generally proving ineffective.196, 197 In contrast, educational outreach visits to clinicians and combinations of two or more interventions could increase the likelihood of affecting practice patterns.196 Some authors have demonstrated that the combination of an educational session led by gastroenterology subspecialists and the availability of office-based H. pylori testing can increase acceptance of the test-and-treat strategy by primary care providers.79 Thus, patients who received this test-and-treat intervention were less likely to receive repeated antisecretory medication prescriptions than controls receiving usual care (passive dissemination of a practice guideline).79

CONCLUSIONS

Dyspepsia is a very frequent and usually chronic condition, accounting for almost 5% of all primary care consultations.42 The available management strategies for individuals with uninvestigated dyspepsia include prompt endoscopy, empirical antisecretory therapy, and the test-and-treat strategy for H. pylori. Although each of the three management options of uninvestigated dyspepsia have advantages and disadvantages, it is widely accepted that endoscopy should be reserved for patients with symptom onset after 45–55 years of age, those who have alarm features, and those whose empirical antisecretory therapy or test-and-treat strategy fails.

The test-and-treat strategy will cure most cases of underlying peptic ulcer disease and prevent most potential cases of gastroduodenal disease. In addition, a minority of infected patients with functional dyspepsia will gain symptomatic benefit.15 Future studies should be able to identify the key epidemiological and patient-related features that would enable us to stratify dyspeptic patients according to their likelihood of improving after treatment of infection by H. pylori.42 In the meantime, the test-and-treat strategy is being reinforced by the accumulating data that support the increasingly accepted idea that “the only good Helicobacter pylori is a dead Helicobacter pylori”.198

Several prospective studies and decision analyses support the use of the test-and-treat strategy, although we must be cautious when extrapolating the results from one area to another. Many factors determine whether this strategy is appropriate in each particular geographic area.

As recently pointed out, over the past 20 years we have seen H. pylori infection transform the way in which we treat patients with dyspepsia; we are now facing the challenge of allowing it to transform the way in which we investigate dyspepsia, in particular the use of endoscopy.199

Study Highlights

Acknowledgments

CIBEREHD is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. This study was not funded by any Pharmaceutical Company.

Guarantor of the article: Javier P. Gisbert, MD, PhD.

Specific author contributions: J.P. Gisbert had the original idea, performed the search strategy for identification of studies, and wrote the manuscript. X. Calvet reviewed the manuscript and did relevant suggestions.

Financial support: None.

Potential competing interests: None.

References

- Jones R, Lydeard S. Prevalence of symptoms of dyspepsia in the community. BMJ. 1989;298:30–32. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6665.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RH, Lydeard SE, Hobbs FD, et al. Dyspepsia in England and Scotland. Gut. 1990;31:401–405. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.4.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, et al. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102 (4 Pt 1:1259–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]