Abstract

While histologic assessment of nodes is a component of all colon cancer staging paradigms, approximately 30% of patients with histology-negative nodes (pN0) die of disseminated disease reflected by occult nodal metastases. Undetected metastases are particularly important when considering racial disparities in colon cancer, where black subjects with pN0 disease exhibit the greatest differences in outcomes, with >40% excess mortality. Recently, guanylyl cyclase C (GCC), a protein normally restricted to intestinal cells, but universally expressed by colorectal cancer cells, was validated for detecting occult metastases. Indeed, occult tumor burden across regional lymph nodes estimated by GCC quantitative reverse transcription PCR identifies pN0 patients with near zero risk, and those with >80% risk, of unfavorable outcomes. Disproportionately high occult tumor burden in black patients underlies racial disparities in stage-specific mortality. These studies position the platform encompassing quantification of occult tumor burden by GCC quantitative reverse transcription PCR for translation, as a detect–treat paradigm to reduce racial disparities in colon cancer mortality.

Keywords: biomarker, colorectal cancer, guanylyl cyclase C, molecular staging, occult tumor burden, prediction, prognosis, quantitative reverse transcription PCR, regional lymph node network, RT-qPCR, staging

While metastases continue to be the major cause of death from cancer, not all tumor cells found at secondary sites are clinically important. This conundrum is exemplified by considering staging patients with colon cancer. Here, the most important prognostic marker of survival and predictive marker of therapeutic response is metastatic tumor cells in regional lymph nodes [1–3]. While histologic assessment of nodes is a central component of all colorectal cancer staging paradigms, the prognostic and predictive significance of nodal metastases remains limited [1–5]. On one hand, approximately 30% of patients with pathology-negative nodes (pN0; stage I and II) die of metastatic disease, reflecting understaging and occult nodal metastases [1–3]. Understaging is particularly important when considering racial disparities in outcomes, and black subjects with pN0 colon cancer are most disadvantaged, with >40% excess mortality attributable to race [6–9]. On the other hand, the clinical significance of tumor cells in nodes remains uncertain, and approximately 50% of patients with visible nodal metastases (stage III) remain disease free [1–3]. Identification of nodal metastases and their prognostic and predictive significance remains one of the greatest challenges in colon cancer [1–5,10].

Recently, guanylyl cyclase C (GCC), a protein whose expression is normally restricted to intestinal cells, but universally expressed by colorectal cancer cells, was clinically validated for detection of prognostically important occult metastases by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR), in a prospective, multicenter, blinded clinical trial [11]. The current authors have used this analytical biomarker platform to create an original molecular staging paradigm that quantifies occult tumor burden across the regional lymph node network, defining clinical disease behavior and identifying pN0 patients with near-zero risk, and those with >80% risk, of unfavorable outcomes [12–14]. Indeed, disproportionate occult tumor burden in black subjects underlies racial disparities in stage-specific mortality [12].

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the fourth most common neoplasm, with approximately 140,000 new cases annually, and is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality, producing approximately 10% of cancer-related deaths, or approximately 50,000 patients annually, in the USA with a mortality rate of approximately 50% [1,3,15]. The impact of this disease can be appreciated in the context of the communities at risk, which in the USA include >100 million people of >50 years of age. Mortality reflects metastases: approximately 20% of patients with colon cancer have unresectable disease at presentation, while >30% develop metastases during their disease. Surgery continues to have the greatest impact on survival [1–3]. However, while ‘curative’ surgery removes all detectable tumor and is most successful in early-stage disease, occult metastases result in relapse [1–3]. Recurrence rates (RRs) range from approximately 10% for disease confined to mucosa (stage I) to >60% for tumors metastatic to more than four nodes (stage III) [1–3].

Colorectal cancer staging

Metastatic tumor cells in nodes are prognostic markers of risk

In colon cancer, the most important prognostic marker of risk is metastatic tumor cells in nodes [1–3]. However, detection of nodal metastases is imprecise and their clinical significance uncertain. With respect to detection, while histopathology remains the gold standard, staging imprecision by conventional microscopy reflects substantial methodological limitations in clinical application [1–5,11]. This technique is relatively insensitive, and the lower limit for detection by microscopy is approximately one cancer cell in 200 lymphocytes [16]. It is also not unusual to examine only one thin section from each node, omitting from review >99.99% of each specimen, resulting in a sampling error. These limitations are most evident when the frequency of postresection disease recurrence is considered. Stage I and II (pN0) lesions, limited to the bowel wall with no histological evidence of extraintestinal spread, should be amenable to complete surgical excision. However, RRs as high as 15% in stage I and 30% in stage II have been reported [1–3,17]. With respect to their clinical significance, while all stage III patients harbor nodal metastases, only approximately 50% develop disease recurrence. In other words, approximately half of patients who harbor visible nodal metastases remain free of recurrences. To date, no molecular markers have emerged that define the clinical significance of nodal metastases, or provide actionable information that improves patient management. Accurate identification of nodal metastases and their clinical significance represents one significant gap in knowledge in the prognostic management of colon cancer [10].

Metastatic tumor cells in nodes are predictive markers of therapeutic benefit

Beyond prognosis, nodal metastases determine which patients receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Regimens based on a framework of 5-fluorouracil, which more recently include irinotecan or oxaliplatin, improve 5-year survival from approximately 40% (untreated) to approximately 50% (treated) [2,18]. Limited therapeutic benefit in stage III patients may reflect their heterogeneity, in which some, but not all, patients have clinically aggressive metastases. One limitation to managing these patients is the inability to identify nodal metastases that are clinically significant, resulting in the administration of toxic therapies to patients who derive no benefit and may be harmed (see below). The situation is even more complex with pN0 patients, where the utility of therapy remains uncertain, with marginal survival benefits in stage II patients in some, but not all, clinical trials [18,19]. This uncertainty of treatment benefit is reflected in the evolution of treatment guidelines, in which adjuvant therapy has become discretionary in pN0 patients with clinicopathologic features of poor prognostic risk [18,19]. Here, heterogeneous responses to therapy in pN0 patients may, in part, reflect heterogeneity of occult nodal metastases and their clinical significance in this patient population [5,11,20]. Thus, there is an unmet clinical need for molecular techniques that detect occult tumor cells and define their prognostic and predictive significance to better identify colon cancer patients who could benefit from therapy. Here, again, accurate detection of nodal metastases and characterization of their clinical significance represents one gap in the knowledge of therapeutic management of colon cancer patients [10].

Racial disparities in colon cancer

Despite decreasing mortality from colon cancer, reflective of advances in screening and therapy, there is a widening racial gap in incidence and survival [9,21,22]. There is approximately a 20% greater incidence of, and approximately a 40% higher mortality from colon cancer in black, compared with white, patients [7,9,21,22]. Disparities in outcomes reflect advanced stage at diagnosis, socioeconomic differences and differences in therapeutic management [6–9,23–25]. Beyond these factors that influence overall outcomes, there are racial disparities in stage-specific outcomes [6,8,9,26]. Paradoxically, the greatest disparities in outcomes occur in early-stage disease, with approximately 40% excess mortality in black subjects with pN0 colon cancer. These stage-specific disparities do not appear to principally reflect socioeconomic status, access to medical care or culturally specific customs [6,8,9,26]. Rather, they could reflect a contribution of a higher incidence and quantity of undetected (occult) metastases in nodes [8,9], representing a significant gap in knowledge concerning mechanisms underlying racial disparities in cancer outcomes. Molecular diagnostics, with their ability to quantify and characterize small numbers of metastatic tumor cells, may represent a unique technological opportunity to close that gap, reducing racial disparities in colon cancer mortality [5,11,20,27–29].

Opportunities in enabling technology

While histology is the gold standard for staging, reflecting the established prognostic relationship between tumor cells in lymph nodes and outcomes [1,3–5,20], this approach underestimates metastases. Up to 70% of tumor-containing lymph nodes harbor metastases that are <0.5 cm that often escape detection by histology [1,3–5,15,20]. This understaging reflects limitations in volumes of tissue sampled in thin (~10 μm) sections and sensitivity, where histology detects only one tumor cell in 200 normal cells [16]. The importance of these limitations can best be appreciated by considering clinically significant categories of lymph node colonization by tumor cells, including metastases >0.2 cm (prognostically significant), micrometastases from 0.02–0.2 cm (indeterminate prognostic significance) and isolated tumor cells <0.02 cm (low prognostic significance) [1,3]. Beyond this 2D histologic view, emerging molecular methods provide extremely sensitive techniques for detecting and characterizing small numbers of tumor cells at metastatic sites. Indeed, enabling technologies, including RT-qPCR, may provide the most sensitive and specific detection of metastases [4,5]. Molecular staging offers technological advantages that overcome historic limitations, with the ability to sample the entire specimen and detect one tumor cell in approximately 107 normal cells [4,5]. While early clinical results with reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) have been heterogeneous, reflecting inadequate population size, absence of clinical follow-up and variable techniques, meta-analyses support the prognostic value of occult metastases in histology-negative nodes detected by RT-PCR in colorectal cancer [4,5].

GCC as a molecular marker for colorectal cancer

GCC is an intestinal tumor-suppressing receptor

GCC, one of a family of proteins synthesizing cyclic GMP, is selectively expressed by intestinal epithelial cells [11,30,31]. GCC is the receptor for the paracrine hormones guanylin and uroguanylin, whose interaction with the extracellular domain activates the cytoplasmic catalytic domain, inducing cyclic GMP accumulation. GCC signaling regulates homeostasis coordinating proliferation, DNA repair, metabolic programming and epithelial–mesenchymal interactions organizing the epithelial crypt–surface axis [32]. In this context, guanylin and uroguanylin are gene products universally lost at an early stage in colorectal cancer, in both animals and humans [33–36]. GCC silencing in mice increases tumorigenesis, reflecting dysregulation of the cell cycle and DNA repair [37–39]. These observations suggest a pathophysiological hypothesis in which GCC is a lineage-dependent tumor-suppressing receptor, coordinating epithelial homeostasis, whose silencing through hormone loss contributes to tumorigenesis [32].

GCC is a marker for colorectal cancer

GCC has been detected in >1000 samples of normal intestine, but not in >1000 extragastrointestinal tissues (tissue specific) [11,30,31]. Of significance, GCC protein (n >200) and/or mRNA (n >900) were detected in nearly all primary and metastatic human colon and rectal tumors regardless of anatomical location or grade, but not in extragastrointestinal tumors (>200). Furthermore, GCC is overexpressed at the mRNA and protein levels by >80% of colon and rectal tumors compared with matched normal adjacent mucosa [40–42]. Stringency of restricted expression normally by intestinal cells and near universal overexpression by metastatic colorectal cancer cells underscores the utility of GCC as a marker for staging patients with colorectal cancer.

The clinical impact of GCC quantitative RT-PCR & occult tumor burden

GCC detects occult metastases with prognostic utility

The utility of qualitative GCC RT-qPCR as a categorical variable (yes/no) for detecting occult metastases in nodes that predict clinical outcomes in pN0 colorectal cancer patients [28,43], was explored in a prospective multicenter blinded clinical trial. This trial required de novo generation and analytical validation of a sensitive, robust and highly reproducible RT-qPCR platform for GCC applicable to thousands of specimens in a high-throughput fashion [41,44]. Moreover, it required novel statistical algorithms for accurate quantification of analyte concentrations that could prognostically stratify large cohorts of patients, providing variable numbers of lymph nodes for assessment [11,45]. Prospective enrollment of 257 patients with pN0 colorectal cancer at nine centers provided 2570 fresh lymph nodes for histology and GCC mRNA analysis. Patients were followed for a median of 24 months (range: 2–63) and main outcome measures were time to recurrence and disease-free survival [11]. Indeed, patients with lymph nodes that were positive for GCC had a greater risk of developing recurrence than those with lymph nodes that were negative for GCC (Table 1). Multivariate analyses revealed that GCC in lymph nodes was the dominant independent marker of prognosis, and patients with histology-negative nodes detected by RT-PCR exhibited an earlier time to recurrence (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] = 4.66 [95% CI: 1.11–19.57]; p = 0.035) and reduced disease-free survival (adjusted HR = 3.27 [95% CI: 1.15–9.29]; p = 0.026). This is the first prospective multicenter, blinded clinical trial providing level I evidence associating occult lymph node metastases detected by RT-PCR with clinical outcomes [11]. This study demonstrates the utility of GCC RT-qPCR to detect occult metastatic tumor cells that define disease behavior. Moreover, this approach is robust and has been independently validated across laboratories, operators and technology platforms [46–48].

Table 1.

Recurrence rates in histology-negative node colorectal cancer patients with and without occult metastases in regional lymph nodes.

| Metastasis status | Total patients (n) | Recurrences (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| No occult metastases | 32 | 2 (6.3) | 0.8–20.8 |

| Occult metastases | 225 | 47 (20.9)* | 15.8–26.8 |

p = 0.006.

Data taken from [11].

The quantity of metastatic tumor cells across the regional lymph node network (occult tumor burden) estimated by GCC RT-qPCR is a prognostic marker of risk in pN0 colorectal cancer

Although a high proportion of pN0 patients harbor occult metastases, as detected by GCC RT-qPCR, most pN0 patients will not recur [1–3]. Reconciliation of this apparent inconsistency relies on the recognition that the categorical (yes/no) presence of nodal metastases does not assure recurrence but rather indicates risk. Indeed, this inability to discriminate clinically important from unimportant nodal metastases represents one of the main gaps in colon cancer management. Uncertainty of the clinical significance of nodal metastases can best be appreciated by considering that only approximately 50% of stage III patients develop recurrent disease although all have visible nodal metastases [1–3].

Here, the uncertainty of the clinical significance of occult nodal metastases highlights the limitations of qualitative RT-PCR generally, and GCC RT-PCR specifically, for categorical (yes/no) identification of occult metastases, which is the absence of information regarding tumor burden [5]. The superior sensitivity of qualitative RT-PCR, with its optimum tissue sampling and capacity for single cell discrimination, identifies occult metastases below the threshold of prognostic risk [1,5,11,20], limiting the specificity of molecular staging. There is an emerging paradigm that goes beyond the categorical (yes/no) presence of tumor cells, to quantify occult metastatic tumor burden (how much) across the regional lymph node network to define tumor behavior and disease risk. This paradigm has its origins in, and builds upon, two established concepts in histopathology. Thus, there is a quantitative relationship between prognostic risk and number of nodes harboring tumor cells by histology, where stage III patients with more than four involved nodes exhibit a RR greater than those with less than three involved nodes [1–3]. There is also a quantitative relationship between the volume of cancer cells in individual nodes and prognostic risk, and metastases >0.2 cm are associated with increased disease recurrence while the relationship between individual tumor cells or nests <0.02 cm and risk remains undefined [1–3]. The emergence of RT-qPCR provides a unique opportunity to quantify occult tumor burden to assign prognostic risk and predict therapeutic benefit. Quantitative measures of GCC expression provide a molecular analog of morphological assessment of metastatic volumes in lymph nodes. This molecular quantification augments 2D morphology by quantifying metastases in a large volume of tissue, rather than a thin section, and across all lymph nodes to estimate occult tumor burden across the regional lymph node network.

In order to examine the quantitative relationship between occult nodal metastases, clinical tumor behavior and prognostic risk, the current authors designed analytic paradigms to explore the association of occult tumor burden, quantified by GCC RT-PCR, with outcomes in colorectal cancer patients [11,13]. Association of outcomes, including time to recurrence and disease-free survival, with prognostic markers including molecular tumor burden, was estimated by recursive partitioning, bootstrap and Cox models [13]. In this cohort, 176 (60%) patients exhibited low tumor burden, and all but four remained free of disease (RR = 2.3% [95% CI: 0.1–4.5%]). In addition, 90 (31%) patients exhibited intermediate tumor burden (MolInt) and 30 (33.3% [95% CI: 23.7–44.1%]) developed recurrent disease. Furthermore, 25 (9%) patients exhibited high tumor burden (MolHigh) and 17 (68.0% [95% CI: 46.5–85.1%]) developed recurrent disease (p < 0.001). Occult tumor burden was an independent marker of prognosis. MolInt and MolHigh patients exhibited a graded risk of earlier time to recurrence (MolInt, adjusted HR = 25.52 [95% CI: 11.08–143.18]; p < 0.001; MolHigh, HR = 65.38 [95% CI: 39.01–676.94]; p < 0.001) and reduced disease-free survival (MolInt, HR = 9.77 [95% CI: 6.26–87.26]; p < 0.001; MolHigh, HR = 22.97 [95% CI: 21.59–316.16]; p < 0.001). These observations provide a striking enhancement over the use of GCC as a categorical (yes/no) marker, where 88% of patients were GCC-positive exhibiting a recurrence risk of 20% [11]. They highlight the unique clinical opportunity to utilize occult tumor burden as a diagnostic marker to assign risk in patients with pN0 colorectal cancer. Identification of cohorts (MolHigh) of pN0 patients with a mortality risk equivalent to patients with disseminated metastases underscores the prognostic value of quantitative occult tumor burden analysis. Moreover, it is tempting to speculate that patients with the greatest occult tumor burden might benefit from therapy. Indeed, occult tumor burden as a marker that discriminates clinically important from unimportant metastases may represent a paradigm shift in staging [10].

Racial disparities in stage-specific outcomes reflect differences in occult tumor burden

Prospective evaluation of the utility of GCC to detect occult metastases in lymph nodes [11,13] provided an opportunity to explore the racial distribution of occult tumor burden and its association with prognostic risk in colorectal cancer [12]. Analysis of GCC expression in this cohort revealed a fourfold greater level of categorical occult metastases in individual nodes in 23 black subjects compared with 259 Caucasian subjects (p < 0.001; 95% CI: 3.3–6.7). Occult tumor burden across the regional lymph node network stratified the entire cohort into categories with low (60%; RR = 2.3% [95% CI: 0.1–4.5%]), intermediate (31%; RR = 33.3% [95% CI: 23.7–44.1%]) and high (9%; RR = 68.0% [95% CI: 46.5–85.1%]; p < 0.001) risk. Multivariate analysis revealed that race (p = 0.02), T stage (p = 0.02) and number of lymph nodes collected for histology (p = 0.003; see below) were independent prognostic markers. Black subjects, when compared with Caucasian subjects, were more likely to harbor levels of occult tumor burden associated with the highest risk (adjusted odds ratio = 5.08; [95% CI: 1.55–16.65]; p = 0.007). These analyses highlight the utility of occult tumor burden as a marker of tumor metastases that estimates prognostic risk contributing to racial disparities in stage-specific outcomes in colorectal cancer. Beyond prognostic risk, they suggest that if occult tumor burden predicts therapeutic benefit, it represents a detect–treat paradigm that could reduce racial disparities in mortality in colon cancer.

Analytic lymph node number optimizes the prognostic accuracy of occult tumor burden

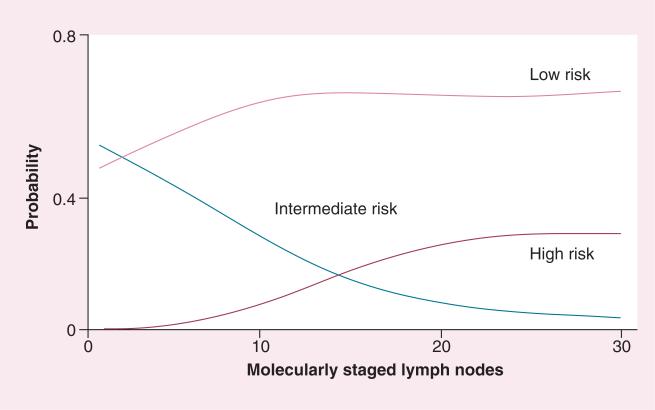

Surprisingly, there was an unanticipated relationship between the number of lymph nodes collected for histology and the molecular quantification of occult tumor burden stratifying risk in blacks and Caucasian subjects [12]. This relationship reflected the fact that the number of nodes collected for histology was directly related to the number provided for GCC RT-qPCR (p = 0.006) [14]. Not surprisingly, the prognostic accuracy of estimating occult tumor burden depends on the number of nodes analyzed by RT-qPCR (Figure 1) [14]. Patients providing more than five nodes exhibited occult tumor burdens that stratified >95% of pN0 patients into low- and intermediate-risk categories, with few patients in the highest risk category. By contrast, analysis of >12 nodes maximally resolved the lowest risk cohort, representing 68% of the pN0 cohort. Moreover, analysis of >23 nodes eliminated the intermediate-risk category, maximizing the resolution of patients with the greatest prognostic risk, representing approximately 28% of the pN0 cohort. These observations suggest that the prognostic accuracy of occult tumor burden quantification depends on the number of analytic lymph nodes. They suggest that the intermediate-risk category results from inaccuracies in estimating occult tumor burden, reflecting insufficient analytic nodes. Based on these observations, analysis of >12 nodes provides estimates of tumor burden that optimally define the clinical behavior of tumor metastases, resolving the pN0 population into patients with: low risk (~70%) with a near-zero likelihood of recurrence; and high risk (~30%) with a maximum likelihood (>70%) of recurrence [14]. It is tempting to speculate that this paradigm provides near-complete prognostic stratification, since approximately 70% of pN0 patients are cured by surgery, while approximately 30% develop recurrence [1–3].

Figure 1.

Probability of risk classification associated with number of lymph nodes analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR.

Reproduced with permission from [14].

Conclusion & future perspective

Paradigms for staging colorectal cancer depend on histological analyses of tumor and regional lymph nodes. However, this algorithm underestimates the magnitude of disease, and approximately 30% of node-negative patients develop tumor recurrence. Inadequacies in accepted histopathology paradigms, specifically tissue sampling and sensitivity, can be abrogated by applying molecular techniques. Molecular identification of occult nodal disease is a powerful independent indicator of prognostic risk of colorectal cancer recurrence. Prospective clinical studies suggest that molecular analyses of lymph nodes can estimate tumor burden that identifies patients at increased risk of developing recurrent disease. In turn, these at-risk patients may specifically benefit from receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. Indeed, future studies will explore the utility of GCC and quantitative occult tumor burden analysis to identify pN0 patients who will benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy. Moreover, future studies will explore the utility of GCC as a marker in preneoplasia, including adenomatous polyps, as well as in inflammatory bowel disease, both of which are associated with a high risk for developing metastatic colorectal cancer.

Genomic approaches are also emerging as approaches that extract clinically relevant information from tumors that improve staging paradigms to optimize clinical outcomes. Transcriptomic analyses, epigenetic profiling, mutations in oncogenes or tumor suppressors, and proteomic and metabolomic signatures in primary tumors can individualize assessments of prognostic risk, identify who should get treatment and predict which treatment will be maximally effective [49–53]. In that regard, it is important to consider that the clinical value of molecular analyses of tumors is only relevant in the context of whether they have metastasized. Thus, a tumor with a molecular profile suggesting a poor prognosis represents a lower risk if it is completely removed at surgery, before metastasizing. These considerations suggest that technologies profiling primary tumors might be most useful when applied to patients with occult nodal metastases, rather than to those free of disease. In this model, molecular staging provides an opportunity to prioritize expensive analyses of tumors to maximize cost-effective disease management [11]. It is anticipated that future clinical trials will examine the utility of analytical algorithms where histology node-negative patients are referred for molecular staging to identify occult lymph node metastases, followed by subsequent molecular profiling of tumors for patients at increased prognostic risk, to define treatments personalized to the biology of their individual cancer [54].

While the technology forming the framework for RT-qPCR is evolving, it continues to remain the province of specialty laboratories, with only modest penetration into academic and community medical centers. In that context, the business of molecular diagnostics is burgeoning, already surpassing US$14 billion and growing 10% each year [55,56]. Similarly, the number of molecular diagnostics approved by the US FDA is expanding annually, from 72 in 2006 to 134 in 2009 [101]. Moreover, ‘home brew’ molecular tests developed in specialty laboratories exceeded 1400 in 2009 [102]. This availability suggests that molecular diagnostics, including molecular staging, will be increasingly integrated into the clinical management of patients. In the short term, specialty laboratories will provide the experience and validated analytic algorithms consistent with FDA guidelines and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reimbursement. Ultimately, these enabling technology platforms will support integration of molecular staging into disease management algorithms.

Executive summary.

Staging paradigms in colorectal cancer

- ■ Metastatic tumor cells in nodes are prognostic markers of risk:

- - Histopathological metastases in regional lymph nodes are the most important marker for staging colorectal cancer.

■ Limitations in current approaches, including limited sampling and sensitivity, result in significant understaging, with 30% of node-negative (pN0) patients developing distant metastases.

Molecular approaches improve staging accuracy

- ■ Opportunities of enabling technology:

- - Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR) overcomes the limitations of histology including sampling, interrogating the entire available specimen and sensitivity, detecting one cancer cell in one million normal cells.

Guanylyl cyclase C is a biomarker for staging colorectal cancer

- ■ Guanylyl cyclase C (GCC) is a marker for colorectal cancer:

- - GCC is selectively expressed in intestinal epithelial cells, universally overexpressed in colorectal cancer, but is not expressed by other tumors outside the GI tract.

Occult metastases in lymph nodes detected by GCC RT-qPCR are clinically significant

- ■ GCC detects occult metastases with prognostic utility:

- - A prospective blinded, multicenter clinical trial revealed that >80% of histology negative nodes (pN0) colorectal cancer patients have occult metastases in more than one lymph node as detected by GCC RT-qPCR.

- - Patients without occult metastases exhibited a low (6%) rate of recurrence while those with occult metastases had a high (21%) rate of recurrence.

Occult tumor burden across the regional lymph node network

- ■ The quantity of metastatic tumor cells across the regional lymph node network estimated by GCC RT-qPCR is a prognostic marker of risk in pN0 colorectal cancer:

- - The amount of occult tumor resident across the regional lymph node network improves the sensitivity and specificity of staging.

- - Quantification of occult tumor burden revealed that 60% of pN0 patients had low (~2%) risk of recurrence while 9% of pN0 patients exhibited high (70%) risk of recurrence.

- ■ Racial disparities in stage-specific outcomes reflect differences in occult tumor burden:

- - Differential occult tumor burden contributed to differences in clinical outcomes in African–American and Caucasian patients with pN0 colon cancer.

Future perspective

■ This approach may be applicable to risk stratification of stage III colon cancer patients and rectal cancer patients.

■ This approach could identify colorectal cancer patients who benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy.

■ This approach represents an opportunity to enhance the value of tumor molecular profiling to optimize colorectal cancer management.

Acknowledgments

SA Waldman is the Chair (uncompensated) of the Scientific Advisory Board of Targeted Diagnostics and Therapeutics, Inc., which provided research funding that, in part, supported this study and that has a license to commercialize inventions related to this work, and the Chair of the Data Safety and Monitoring Committee for the C-Cure Trial sponsored by Cardio3 (Belgium). This work was supported by funding from the NIH (CA75123, CA95026, CA112147, CA146033, CA170533), Targeted Diagnostic & Therapeutics, Inc., and the Pennsylvania Department of Health (SAP #4100059197, SAP #4100051723). The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. SA Waldman is the Samuel MV Hamilton Endowed Professor.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

■■ of considerable interest

- 1.Compton CC, Greene FL. The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2004;54(6):295–308. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.6.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham D, Atkin W, Lenz HJ, et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2010;375(9719):1030–1047. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Joint Committee on Cancer . In: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual (7th Edition) Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. Springer; NY, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4■.Iddings D, Ahmad A, Elashoff D, Bilchik A. The prognostic effect of micrometastases in previously staged lymph node negative (N0) colorectal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006;13(11):1386–1392. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9120-y. [Provides a meta-analyses of the utility of occult lymph node analyses to staging patients with colorectal cancer.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5■.Nicastri DG, Doucette JT, Godfrey TE, Hughes SJ. Is occult lymph node disease in colorectal cancer patients clinically significant? A review of the relevant literature. J. Mol. Diagn. 2007;9(5):563–571. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.070032. [Provides a meta-analyses of the utility of occult lymph node analyses to staging patients with colorectal cancer.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chien C, Morimoto LM, Tom J, Li Ci. Differences in colorectal carcinoma stage and survival by race and ethnicity. Cancer. 2005;104(3):629–639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le H, Ziogas A, Lipkin SM, Zell JA. Effects of socioeconomic status and treatment disparities in colorectal cancer survival. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(8):1950–1962. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marcella S, Miller JE. Racial differences in colorectal cancer mortality. The importance of stage and socioeconomic status. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2001;54(4):359–366. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00316-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soneji S, Iyer SS, Armstrong K, Asch DA. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality: 1960–2005. Am. J. Public Health. 2010;100(10):1912–1916. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grothey A. Does stage II colorectal cancer need to be redefined? Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(10):3053–3055. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11■■.Waldman SA, Hyslop T, Schulz S, et al. Association of GUCY2C expression in lymph nodes with time to recurrence and disease-free survival in pN0 colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2009;301(7):745–752. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.141. [Reports the first prospective multicenter, blinded clinical trial of the utility of a molecular marker to identify clinically significant occult lymph node metastases in histologically negative nodes (pN0) in colorectal cancer patients.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12■.Hyslop T, Weinberg DS, Schulz S, Barkun A, Waldman SA. Occult tumor burden contributes to racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer outcomes. Cancer. 2012;118(9):2532–2540. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26516. [Describes the contribution of occult tumor burden in regional lymph nodes to differences in clinical outcomes in pN0 African–American and Caucasian colorectal cancer patients.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13■■.Hyslop T, Weinberg Ds, Schulz S, Barkun A, Waldman SA. Occult tumor burden predicts disease recurrence in lymph node-negative colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(10):3293–3303. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3113. [Describes for the first time the analytical approach to quantifying occult tumor burden across the regional lymph node network in patients with pN0 colon cancer.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14■.Hyslop T, Weinberg DS, Schulz S, Barkun A, Waldman SA. Analytic lymph node number establishes staging accuracy by occult tumor burden in colorectal cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2012;106(1):24–30. doi: 10.1002/jso.23051. [Describes the importance of the number of lymph nodes analyzed to accurate quantification of occult tumor burden across the regional lymph node network for staging patients with pN0 colorectal cancer.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61(4):212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratto C, Sofo L, Ippoliti M, et al. Accurate lymph-node detection in colorectal specimens resected for cancer is of prognostic significance. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1999;42(2):143–154. doi: 10.1007/BF02237119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radel C, Martus P, Papadoupolos T, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor regression after preoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(34):8688–8696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyerhardt JA, Mayer RJ. Systemic therapy for colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352(5):476–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benson AB, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(16):3408–3419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iddings D, Bilchik A. The biologic significance of micrometastatic disease and sentinel lymph node technology on colorectal cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 2007;96(8):671–677. doi: 10.1002/jso.20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI. Colorectal cancer and race: understanding the differences in outcomes between African Americans and whites. Med. Clin. North Am. 2005;89(4):771–793. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polite BN, Dignam JJ, Olopade OI. Colorectal cancer model of health disparities: understanding mortality differences in minority populations. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24(14):2179–2187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Pinsky PF, et al. Race and colorectal cancer disparities: health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(8):538–546. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayberry RM, Coates RJ, Hill HA, et al. Determinants of black/white differences in colon cancer survival. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(22):1686–1693. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.22.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White A, Vernon SW, Franzini L, Du XL. Racial disparities in colorectal cancer survival: to what extent are racial disparities explained by differences in treatment, tumor characteristics, or hospital characteristics? Cancer. 2010;116(19):4622–4631. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Vw, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Wu XC, et al. Aggressiveness of colon carcinoma in blacks and whites. National cancer institute black/white cancer survival study group. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6(12):1087–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilchik AJ, Hoon DS, Saha S, et al. Prognostic impact of micrometastases in colon cancer: interim results of a prospective multicenter trial. Ann. Surg. 2007;246(4):568–575. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a9c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cagir B, Gelmann A, Park J, et al. Guanylyl cyclase C messenger RNA is a biomarker for recurrent stage II colorectal cancer. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999;131(11):805–812. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-11-199912070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29■.Liefers GJ, Cleton-Jansen AM, van de Velde CJ, et al. Micrometastases and survival in stage II colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;339(4):223–228. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390403. [One of the first demonstrations of the utility of reverse transcription PCR to identify occult micrometastases in lymph nodes from patients with pN0 colorectal cancer.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrithers SL, Barber MT, Biswas S, et al. Guanylyl cyclase C is a selective marker for metastatic colorectal tumors in human extraintestinal tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93(25):14827–14832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frick GS, Pitari GM, Weinberg DS, Hyslop T, Schulz S, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclase C: a molecular marker for staging and postoperative surveillance of patients with colorectal cancer. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2005;5(5):701–713. doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pitari GM, Li P, Lin JE, et al. The paracrine hormone hypothesis of colorectal cancer. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;82(4):441–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birkenkamp-Demtroder K, Lotte Christensen L, Harder Olesen S, et al. Gene expression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4352–4363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Notterman DA, Alon U, Sierk AJ, Levine AJ. Transcriptional gene expression profiles of colorectal adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and normal tissue examined by oligonucleotide arrays. Cancer Res. 2001;61(7):3124–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shailubhai K, Yu HH, Karunanandaa K, et al. Uroguanylin treatment suppresses polyp formation in the ApcMin/+ mouse and induces apoptosis in human colon adenocarcinoma cells via cyclic GMP. Cancer Res. 2000;60(18):5151–5157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinbrecher KA, Tuohy TM, Heppner Goss K, et al. Expression of guanylin is downregulated in mouse and human intestinal adenomas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;273(1):225–230. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li P, Lin JE, Chervoneva I, Schulz S, Waldman SA, Pitari GM. Homeostatic control of the crypt-villus axis by the bacterial enterotoxin receptor guanylyl cyclase C restricts the proliferating compartment in intestine. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171(6):1847–1858. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li P, Schulz S, Bombonati A, et al. Guanylyl cyclase C suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis by restricting proliferation and maintaining genomic integrity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(2):599–607. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin JE, Li P, Snook AE, et al. The hormone receptor GUCY2C suppresses intestinal tumor formation by inhibiting AKT signaling. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(1):241–254. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birbe R, Palazzo JP, Walters R, Weinberg D, Schulz S, Waldman SA. Guanylyl cyclase C is a marker of intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Hum. Pathol. 2005;36(2):170–179. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulz S, Hyslop T, Haaf J, et al. A validated quantitative assay to detect occult micrometastases by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction of guanylyl cyclase C in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4545–4552. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Witek ME, Nielsen K, Walters R, et al. The putative tumor suppressor Cdx2 is overexpressed by human colorectal adenocarcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11(24 Pt 1):8549–8556. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Waldman SA, Cagir B, Rakinic J, et al. Use of guanylyl cyclase C for detecting micrometastases in lymph nodes of patients with colon cancer. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1998;41(3):310–315. doi: 10.1007/BF02237484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chervoneva I, Hyslop T, Iglewicz B, et al. Statistical algorithm for assuring similar efficiency in standards and samples for absolute quantification by real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Anal. Biochem. 2006;348(2):198–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chervoneva I, Li Y, Iglewicz B, Waldman S, Hyslop T. Relative quantification based on logistic models for individual polymerase chain reactions. Stat. Med. 2007;26(30):5596–5611. doi: 10.1002/sim.3127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46■.Beaulieu M, Desaulniers M, Bertrand N, et al. Analytical performance of a qRT-PCR assay to detect guanylyl cyclase C in FFPE lymph nodes of patients with colon cancer. Diagn. Mol. Pathol. 2010;19(1):20–27. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3181ad5ac3. [Confirms the utility of guanyly cyclase C detection by quantitative reverse transcription PCR for identifying occult metastases in regional lymph nodes of patients with pN0 colorectal cancer.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47■.Haince JF, Houde M, Beaudry G, et al. Comparison of histopathology and RT-qPCR amplification of guanylyl cyclase C for detection of colon cancer metastases in lymph nodes. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010;63(6):530–537. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2009.072983. [Confirms the utility of guanyly cyclase C detection by quantitative reverse transcription PCR for identifying occult metastases in regional lymph nodes of patients with pN0 colorectal cancer.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48■.Sargent DJ, Resnick MB, Meyers MO, et al. Evaluation of guanylyl cyclase C lymph node status for colon cancer staging and prognosis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2011;18(12):3261–3270. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1731-2. [Confirms the utility of guanyly cyclase C detection by quantitative reverse transcription PCR for identifying occult metastases in regional lymph nodes of patients with pN0 colorectal cancer.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Croner RS, Peters A, Brueckl WM, et al. Microarray versus conventional prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104(2):395–404. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frigola J, Song J, Stirzaker C, Hinshelwood RA, Peinado MA, Clark SJ. Epigenetic remodeling in colorectal cancer results in coordinate gene suppression across an entire chromosome band. Nat. Genet. 2006;38(5):540–549. doi: 10.1038/ng1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, et al. Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N. Engl. J Med. 1994;331(4):213–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199407283310401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;351(27):2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang Y, Jatkoe T, Zhang Y, et al. Gene expression profiles and molecular markers to predict recurrence of Dukes’ B colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(9):1564–1571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Allegra CJ, Jessup JM, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(12):2091–2096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson C, Schulz S, Waldman S. Cancer biomarkers: where medicine, business, and public policy intersect. Biotechnol. Healthc. 2007 Feb;:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wilson C, Schulz S, Waldman SA. Biomarker development, commercialization, and regulation: individualization of medicine lost in translation. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;81(2):153–155. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Holland C. FDA-cleared/approved molecular diagnostic tests. 2010 www.amp.org/FDATable/FDATable.doc.

- 102.Sun F, Breuning W, Uhl S, Ballard R, Tipton K, Schoelles K. Quality, regulation and clinical utility of laboratory-developed tests. 2009 www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coverage/DeterminationProcess/downloads/id72TA.pdf. [PubMed]