Abstract

Using a macromonomer, first, third and fifth generation triazine dendrimers can be prepared using a divergent approach. The nine step process to the fifth generation target relies on an iterative two-reactions-per-generation strategy to yield the desired material in ~48% overall yield. This target displays 96 surface groups. NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry show exceptionally narrow polydispersity is achieved using this strategy.

Despite the wealth of chemistries adopted for their preparation, medium and large generation dendrimers are relatively rare although the situation is improving as emerging routes are increasingly efficient.1–3 Generation 2 and 3 materials are more commonplace. Low generation dendrimers are prepared more readily and often are amenable to characterization using the techniques routinely applied to small molecules: NMR and mass spectrometry. At larger generations, the molecular weights of the dendrimers often exceed the resolution of mass spectrometers. Additionally, defects in structure cannot be resolved by NMR due to limits in confidence set by signal-to-noise ratios.

The routes to dendrimers, in the extreme, rely on convergent, divergent, or combined convergent/divergent approaches. These routes have their own advantages and disadvangtes. Divergent methods have successfully been used to synthesize high generation dendrimers, notably PAMAM, up to generation 10.1 Historically, the products of these syntheses have been difficult to define. Here, each generation requires the successful reaction of increasingly large numbers of peripheral groups. Intuition suggests that the limits of unique monodispersity are defined by the limits of the analytical methods employed. Still, the route has been successfully employed by many including recent examples of phosphorous containing dendrimers from Caminade and Majoral,2 and the thiolene dendrimers from Hawker.3 Recently, we described a divergent route to generation five triazine dendrimers, that relied on a three-steps-per-generation iterative cycle.4 Both poor reaction yields and the onset of impurities arose at generations 4 and 5 due in part to solubility issues.

Alternatively, the convergent method pioneered in 1990 by Hawker and Fréchet offers advantage over the divergent approach in that fewer reactions—often the coupling of two dendrons—are required during each reaction.5 However, this approach is often limited to lower generation dendrimers because steric hinderance increases with each increasing generation, notably when two or more dendrons are attached to a core in the final step. Still, the convergent approach has been accepted as a useful method for synthesizing polyamides,6 polyesters,7 poly(ether ketones),8 carbohydrates,9 and triazines.10

Our recent success with large-scale, divergent routes to low-generation triazine dendrimers11 led us to examine the use of a so-called macromonomer to acccess larger structures. In addition, the method reported installs these two generation using a two-step-per-cycle strategy.

Macromonomers see their origins in the double-stage convergent method described first in 1991.12 These building blocks allow the synthesis of higher generation dendrimers in fewer steps and with narrower dispersity. Dendrimers based on a number of monomer units, including phenylacetylene,13 polyesters,14 polyamides,15 and oligo(thienylethynylene)s,16 have been synthesized using this method. However, despite the advantages of this synthetic route, the method is used much less often than the standard divergent or convergent strategies.

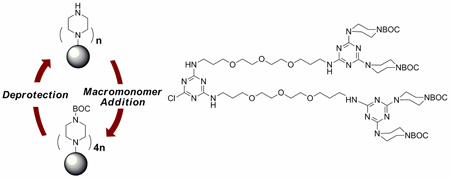

Design. The design criteria for adopting this approach included pairing monochlorotriazine macromonomers with reactive, constrained secondary amines presented on the dendrimer. Monochlorotriazines are stable and have significant shelf-lives faciliating larger scale production without fear of hydroylsis. Constrained secondary amines are sufficiently reactive to engage in nucleophilic aromatic substitution with the monochlorotriazine monomers.17

The macromonomer, 2, includes two diamines. BOCpiperazine, an inexpensive, commercially available building block, is placed on the periphery. Upon deprotection, it provides the desired nucleophilicity derived from a constrained secondary amine. The flexible diamine was incorporated into the macromonomer based on our experience. Solubility is compromised by either rigidly linking triazines or by providing multiple hydrogen-bond donating groups.18 The diamines chosen successfully weigh flexibility against adding such groups: The products described herein have very high solubility.

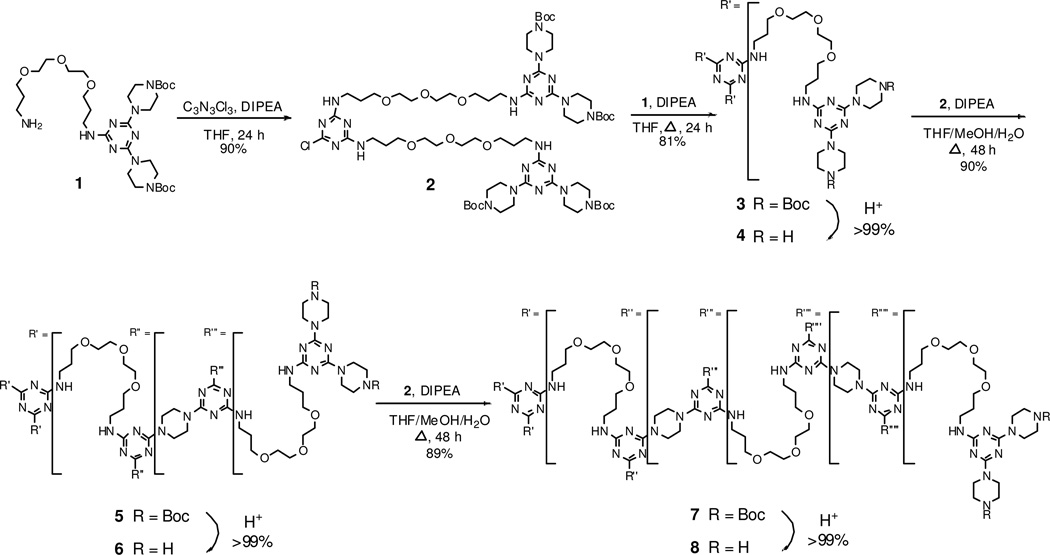

Synthesis. The synthetic route applied to make generation 1, 3 and 5 triazine dendrimers (4, 6, and 8, respectively) is shown in Scheme 1. The route starts with the preparation of amine 1 by reaction of cyanuric chloride with BOC-piperazine and ultimately, the flexible diamine. Executed in two steps, the reactions provide the desired product in 81% overall yield.

Scheme 1.

The synthesis of flexible triazine dendrimers relies on the secondary cyclic amines that generally show significantly higher reactivity compared to primary analogues, to function as nucleophiles in SNAr reactions.

Macromonomer 2 is accessed upon reaction of 1 with cyanuric chloride in 90% isolated yield. The generation 1 dendrimer, 3, shown in Scheme 1, is obtained by reacting 1 with 2. Following deprotection, larger generations are provided by iteration. Each deprotection step is executed quantitatively. Addtion of macromonomers to the deprotected dendrimers, 4 and 6, is processed with both high yield (~90%) and no detectable incomplete reaction in 48 hours. The excess/unreacted 2 is recovered from the purification step and reused.

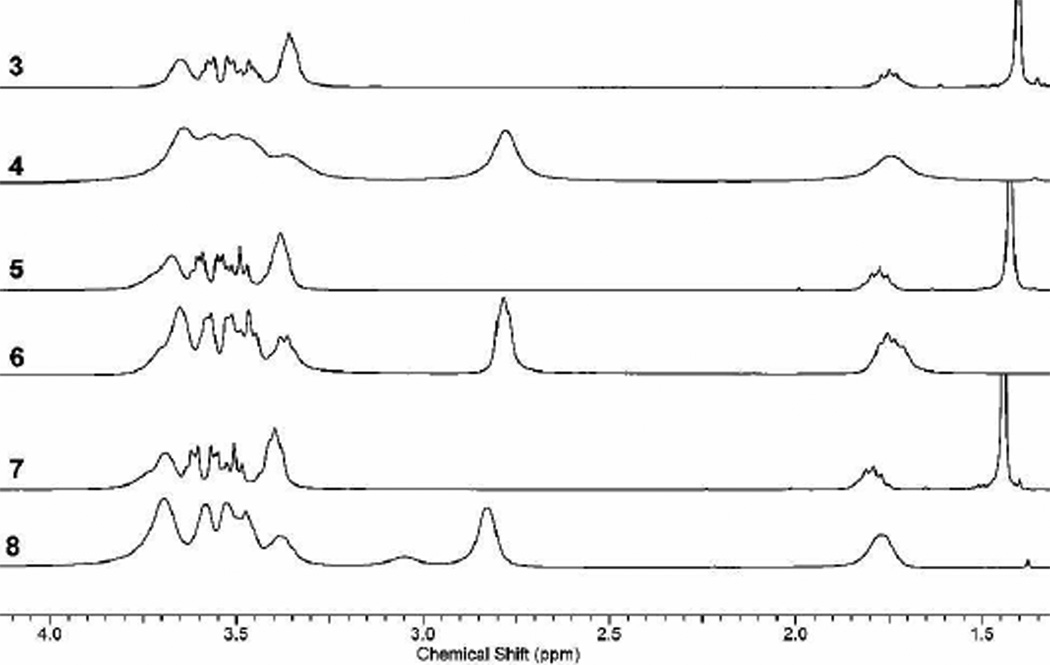

Characterization. Targets and intermediates are characterized using 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and mass spectrometry. 1H NMR spectra proves to be a useful method for characterizing especially the low generation intermediates. The 1H NMR spectra shown in Figure 1 reveal the iterative nature of the synthesis. Deprotection can be monitored using the tert-butyl peak at 1.4 ppm. The degree of substitution of the piperazine groups can be monitored with two peaks that report on the α-methylene protons. The peak at 2.8 ppm corresponds to free base (NCH2CH2NH), while the peak at 3.4 corresponds to Boc-piperazine (NCH2CH2NBoc).

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectrum of the first, third, and fifth generation protected and deprotected dendrimers (300 MHz, CDCl3).

The spectra suggest that the reactions described have proceeded to completion. This level of purity is similar to that seen by Majoral and Caminade for their phosphorus- containing dendrimers, although it should be noted that these structures reached generation 7 before detectable impurities could be observed by phosphorus NMR.2

However, composition impacts our ability to confidently interpret this data. For example, reaction of the six piperazine amines of the first generation dendrimer, 4, with six macromonomers yields 5 with a total of 30 substituted piperazine groups. If only five macromonomer additions occur, the product presents 26 fully substituted piperazine groups and a single free base that remains unreacted (and half-substituted!). This defect (corresponding to 2% H) is unlikely to be readily identified in the NMR spectrum. The situtation is exacerbated in the fifth generation target. If only 23 of the 24 macromonomers react, the 122 fully substituted piperazines appear to effectively obscure 1 half-substituted free-base. Accordingly, we rely on mass spectrometry to corroborate estimates of purity.

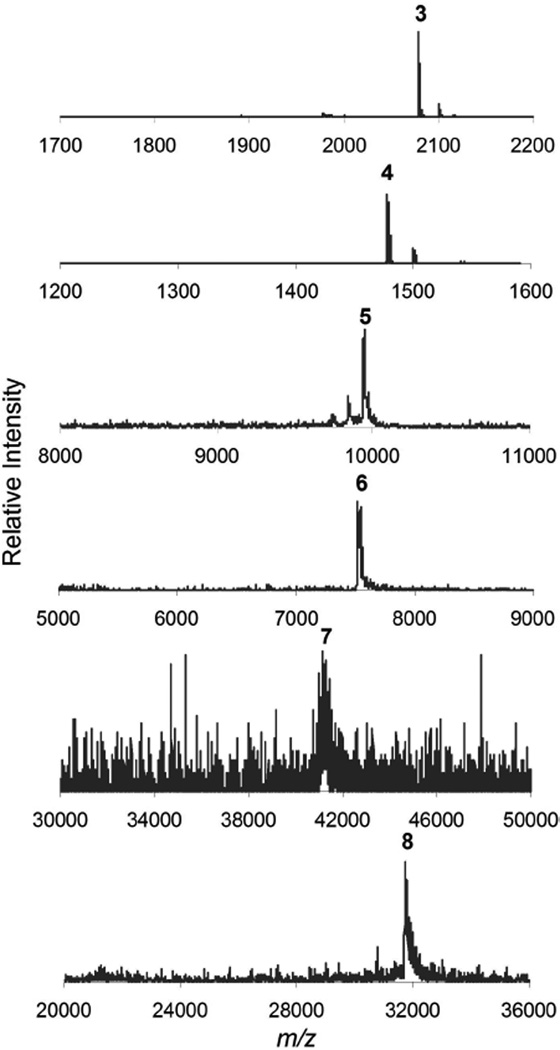

Mass spectrometry has been useful for corroborating both existence of the desired species and detection of the products of incomplete substitution. Data derived from mass spectrometry is compiled in Table 1 (spectra are provided in the Supporting Information). The spectra show single chemical entity products, with additional peaks in the spectrum corresponding primarily to loss of Boc groups during ionization (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Mass spectra data for flexible dendrimers.

| Compound | Calculated (M+) | Found (M+H+) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 667.4381 | 668.3845 |

| 2 | 1445.8386 | 1446.8088 |

| 3 | 2077.3000 | 2078.3853 |

| 4 | 1476.9855 | 1478.1023 |

| 5 | 9936.16 | 9945.30 |

| 6 | 7534.90 | 7520.91 |

| 7 | 41371.59 | 41258.42 |

| 8 | 31766.55 | 31764.04 |

Figure 2.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrograms of the first, third, and fifth generation dendrimers show m/z of the desired products.

As shown in Figure 2, the mass spectrum of the fifth generation dendrimer 7 shows that the reaction has gone to completion despite the poor signal-to-noise ratio that is common for large molecules in this mass range. The deprotected dendrimer 8 provides the better mass resolution due to free amine groups that is amenable to ionization.

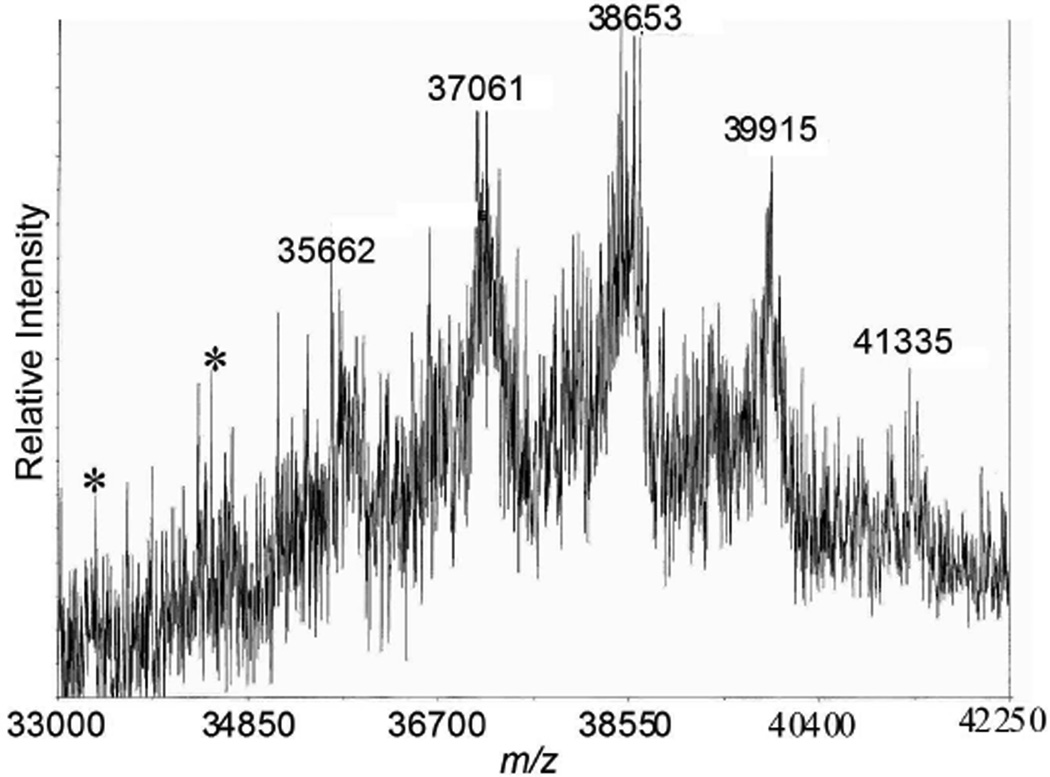

The ability of mass spectrometry to report on reaction progress increases our confidence. Figure 3 shows the reaction progress with clear evidence for intermediates lacking up to four macromonomer units. The molecular weight of the macromonomer (~1500 Da) allows for more definitive assignment of defects of structure than a smaller monomer might.

Figure 3.

Mass spectrum of 7 shows the desired product (m/z 41335) and features corresponding to targets missing 1–4 macromonomers. Additional clues of defects (targets missing 5 and 6 macromonomers) are indicated with a *.

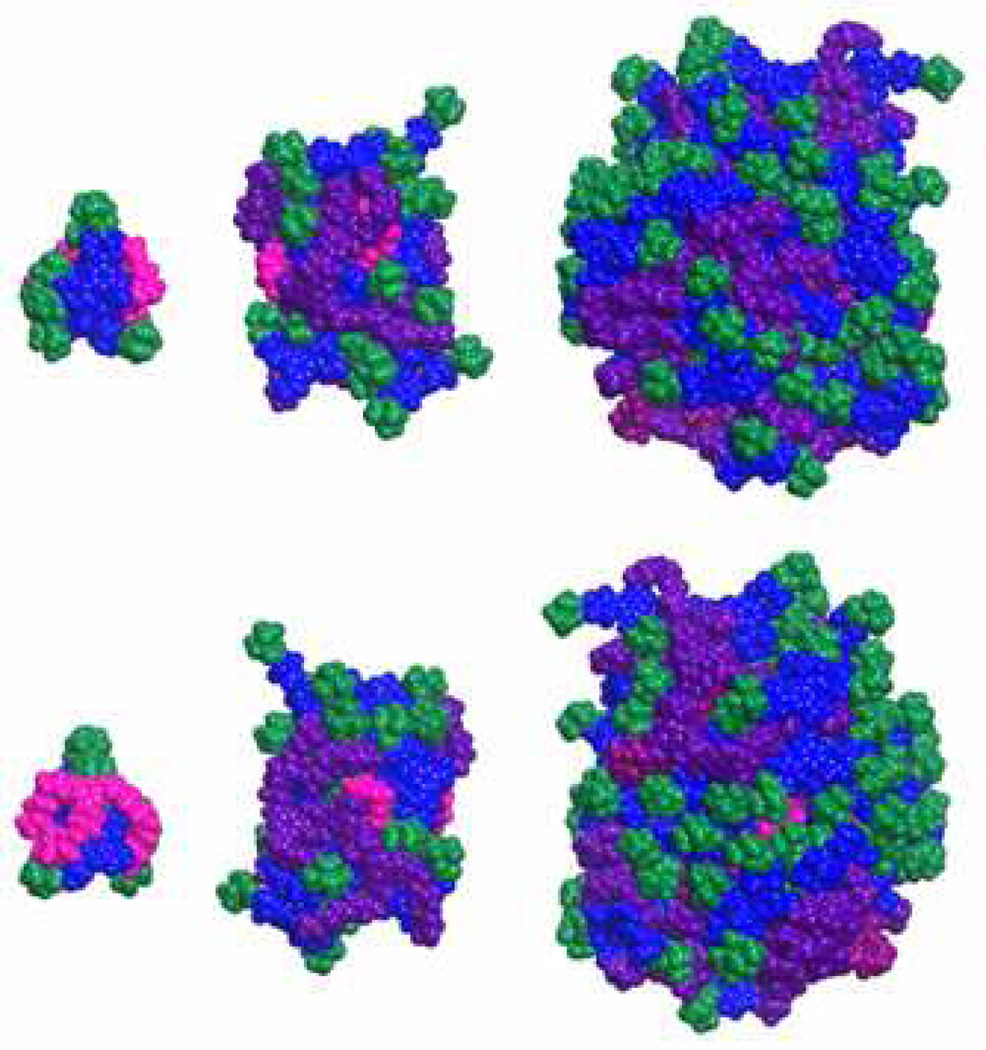

Gas phase simulations of these materials allow us to probe the onset of globular structure and to further our intuition on the density of surface groups. Figure 4 shows the front and back (180° rotation) projections of the protected dendrimers, 3, 5, and 7. As with the previous architectures, the simulations convey that globular structure is achieved at generation 3 as judged by the relative inaccessibility of the core (salmon). By generation 5, peripheral groups (green=BOC) appear to be relatively well dispersed across the periphery. The gas-phase radii of gyration of 3, 5, and 7 are 7.3, 13, and 21 nm, respectively.

Figure 4.

Front and back sides of dendrimers 3, 5, and 7 with Boc groups (green), peripheral triazines (blue), outer generation (purple), inner generation (raspberry), and core (salmon) indicated by color.

The use of macromonomers in the synthesis of triazine dendrimers offers rapid access to odd generation targets. While divergent and convergent routes can afford low generation structures reliably, issues with solubility and the high number of reaction steps required previously limited the robustness of these methods beyond generation 3 materials. Here, the generation 5 dendrimers, 7 and 8, are synthesized in half the number of steps at 48% overall yield. Even generation materials can also be accessed. The targets show a monodisperse structure confirmed by MALDI-TOF MS even though the technique is often unsuccessful for these species in this mass range.19 This approach proves simple and reliable, and is predicted to successfully extrapolated to larger scale syntheses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We acknowledge support of the NIH (NIGMS R01 64560).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, and mass spectra are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For reviews see: Tomalia DA, Naylor AM, Goddard WA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1990;29:138–175. Tomalia DA, Fréchet JMJ. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2002;40:2719–2728.

- 2.(a) Launay N, Caminade AM, Lahana R, Majoral JP. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1994;33:1589–1592. [Google Scholar]; (b) Launay N, Caminade AM, Majoral JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:3282–3283. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Killops KL, Campos LM, Hawker CJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:5062–5064. doi: 10.1021/ja8006325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crampton H, Hollink E, Perez LM, Simanek EE. New J. Chem. 2007;31:1283–1290. doi: 10.1039/b617875h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Hawker CJ, Fréchet JMJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7638–7647. [Google Scholar]; (b) Grayson SM, Fréchet JMJ. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3819–3867. doi: 10.1021/cr990116h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uhrich KE, Fréchet JMJ. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1: Org. Bioorg. Chem. 1992;13:1623–1630. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawker CJ, Fréchet JMJ. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1: Org. Bioorg. Chem. 1992;19:2459–2469. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morikawa A, Kakimoto M, Imai Y. Macromolecules. 1993;26:6324–6329. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashton PR, Boyd SE, Brown CL, Jayaraman N, Stoddart JF. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1997;36:732–735. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Simanek EE. Org. Lett. 2000;2:843–845. doi: 10.1021/ol005585g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chouai A, Simanek EE. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:2357–2366. doi: 10.1021/jo702462t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wooley KL, Hawker CJ, Fréchet JMJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4252–4261. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu Z, Kahr M, Walker KL, Wilkins CL, Moore JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:4537–4550. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(94)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ihre H, Hult A, Fréchet JMJ, Gitsov I. Macromolecules. 1998;31:4061–4068. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishida Y, Jikei M, Kakimoto M. Macromolecules. 2000;33:3202–3211. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang JL, Yan J, Tang ZM, Xiao Q, Ma Y, Pei J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9952–9962. doi: 10.1021/ja803109r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Steffenson MB, Simanek EE. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2359–2361. doi: 10.1021/ol0347491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Moreno KX, Simanek EE. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:1152–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2007.12.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Zhang W, Gonzalez SO, Simanek EE. Macromolecules. 2002;35:9015–9021. [Google Scholar]; (b) Merkel OM, Mintzer MA, Sitterberg J, Bakowsky U, Simanek EE, Kissel T. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1799–1806. doi: 10.1021/bc900243r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Kim C, Kim H. J. Polym. Sci.: Part A. Polym Chem. 2001;40:326–333. [Google Scholar]; (b) Jayamurugan G, Jayaraman N. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:9582–9588. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.