Abstract

The maintenance of metabolic homeostasis requires the well-orchestrated network of several pathways of glucose, lipid and amino acid metabolism. Mitochondria integrate these pathways and serve not only as the prime site of cellular energy harvesting but also as the producer of many key metabolic intermediates. The sirtuins are a family of NAD+-dependent enzymes, which have a crucial role in the cellular adaptation to metabolic stress. The mitochondrial sirtuins SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5 together with the nuclear SIRT1 regulate several aspects of mitochondrial physiology by controlling posttranslational modifications of mitochondrial protein and transcription of mitochondrial genes. Here we discuss current knowledge how mitochondrial sirtuins and SIRT1 govern mitochondrial processes involved in different metabolic pathways.

Keywords: Deacetylase, Energy homeostasis, Metabolism, Mitochondria, Sirtuins

1.Introduction

Mitochondria are organelles composed of a matrix enclosed by a double (inner and outer) membrane (1). Major cellular functions, such as nutrient oxidation, nitrogen metabolism, and especially ATP production, take place in the mitochondria. ATP production occurs in a process referred to as oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), which involves electron transport through a chain of protein complexes (I-IV), located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. These complexes carry electrons from electron donors (e.g. NADH) to electron acceptors (e.g. oxygen), generating a chemiosmotic gradient between the mitochondrial intermembrane space and matrix. The energy stored in this gradient is then used by ATP synthase to produce ATP (1). One well-known side effect of the OXPHOS process is the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that can generate oxidative damage in biological macromolecules (1). However, to neutralize the harmful effects of ROS, cells have several antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidases (1). The sirtuin silent information regulator 2 (Sir2), the founding member of the sirtuin protein family, was identified in 1984 (2). Sir2 was subsequently characterized as important in yeast replicative aging (3) and shown to posses NAD+-dependent histone deacetylase activity (4), suggesting it could play a role as an energy sensor. A family of conserved Sir2-related proteins was subsequently identified. Given their involvement in basic cellular processes and their potential contribution to the pathogenesis of several diseases (5), the sirtuins became a widely studied protein family.

In mammals the sirtuin family consists of seven proteins (SIRT1-SIRT7), which show different functions, structure, and localization. SIRT1 is mostly localized in the nucleus but, under specific physiological conditions, it shuttles to the cytosol (6). Similar to SIRT1, also SIRT6 (7) and SIRT7 (8) are localized in the nucleus. On the contrary, SIRT2 is mainly present in the cytosol and shuttles into the nucleus during G2/M cell cycle transition (9). Finally, SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5, are mitochondrial proteins (10).

The main enzymatic activity catalyzed by the sirtuins is NAD+-dependent deacetylation, as known for the progenitor Sir2 (4,11). Along with histones also many transcription factors and enzymes were identified as targets for deacetylation by the sirtuins. Remarkably, mammalian sirtuins show additional interesting enzymatic activities. SIRT4 has an important ADP-ribosyltransferase activity (12), while SIRT6 can both deacetylate and ADP-ribosylate proteins (13,14). Moreover, SIRT5 was recently shown to demalonylate and desuccinylate proteins (15,16), in particular the urea cycle enzyme carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 (CPS1) (16). The (patho-)physiological context in which the seven mammalian sirtuins exert their functions, as well as their biochemical characteristics, are extensively discussed in the literature (17,18) and will not be addressed in this review; here we will focus on the emerging roles of the mitochondrial sirtuins, and their involvement in metabolism. Moreover, SIRT1 will be discussed as an important enzyme that indirectly affects mitochondrial physiology.

Sirtuins are regulated at different levels. Their subcellular localization, but also transcriptional regulation, post-translational modifications, and substrate availability, all impact on sirtuin activity. Moreover, nutrients and other molecules could affect directly or indirectly sirtuin activity. As sirtuins are NAD+-dependent enzymes, the availability of NAD+ is perhaps one of the most important mechanisms to regulate their activity. Changes in NAD+ levels occur as the result of modification in both its synthesis or consumption (19). Increase in NAD+ amounts during metabolic stress, as prolonged fasting or caloric restriction (CR) (20-22), is well documented and tightly connected with sirtuin activation (4,19). Furthermore, the depletion and or inhibition of poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) 1 (23) or cADP-ribose synthase 38 (24), two NAD+ consuming enzymes, increase SIRT1 action.

Analysis of the SIRT1 promoter region identified several transcription factors involved in up- or down-regulation of SIRT1 expression. FOXO1 (25), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) α/β (26,27), and cAMP response element-binding (28) induce SIRT1 transcription, while PPARγ (29), hypermethylated in cancer 1 (30), PARP2 (31), and carbohydrate response element-binding protein (28) repress SIRT1 transcription. Of note, SIRT1 is also under the negative control of miRNAs, like miR34a (32) and miR199a (33). Furthermore, the SIRT1 protein contains several phosphorylation sites that are targeted by several kinases (34,35), which may tag the SIRT1 protein so that it only exerts activity towards specific targets (36,37). The beneficial effects driven by the SIRT1 activation - discussed below- led the development of small molecules modulators of SIRT1. Of note, resveratrol, a natural plant polyphenol, was shown to increase SIRT1 activity (38), most likely indirectly (22,39,40), inducing lifespan in a range of species ranging from yeast (38) to high-fat diet fed mice (41). The beneficial effect of SIRT1 activation by resveratrol on lifespan, may involve enhanced mitochondrial function and metabolic control documented both in mice (42) and humans (43). Subsequently, several powerful synthetic SIRT1 agonists have been identified (e.g. SRT1720 (44)), which, analogously to resveratrol, improve mitochondrial function and metabolic diseases (45). The precise mechanism of action of these compounds is still under debate; in fact, it may well be that part of their action is mediated by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation (21,22,46), as resveratrol was shown to inhibit ATP synthesis by directly inhibiting ATP synthase in the mitochondrial respiratory chain (47), leading to an energy stress with subsequent activation of AMPK. However, at least in β-cells, resveratrol-mediated SIRT1 activation and AMPK activation seem to regulate glucose response in the opposite direction, pointing to the existence of alternative molecular targets (48).

Another hypothesis to explain the pleitropic effects of resveratrol suggests it inhibits cAMP-degrading phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), resulting in the cAMP-dependent activation of exchange proteins activated by cyclic AMP (Epac1) (40). The consequent Epac1-mediated increase of intracellular Ca2+ levels may then activate of CamKKβ-AMPK pathway (40), which ultimately will result in an increase in NAD+ levels and SIRT1 activation (21). Interestingly, also PDE4 inhibitors reproduce some of the metabolic benefits of resveratrol representing yet another putative way to activate SIRT1.

The regulation of the activity of the mitochondrial sirtuins is at present poorly understood. SIRT3 expression is induced in white adipose (WAT) and brown adipose tissues upon CR (49), while it is down-regulated in the liver of high-fat fed mice (50). SIRT3 activity changes also in the muscle after fasting (51) and chronic contraction (52). All these processes are associated with increase (20,53) or decrease (50) in NAD+ levels. From a transcriptional point of view, SIRT3 gene expression in brown adipocytes seems under the control of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α) -estrogen-related receptor α (ERRα) axis, and this effect is crucial for full brown adipocyte differentiation (54,55). SIRT4 expression is reported to be reduced during CR (12), while the impact of resveratrol on SIRT4 is still under debate (56). Finally, upon ethanol exposure, SIRT5 gene expression was shown to be decreased together with the NAD+ levels (57), probably explaining the protein hyperacetylation caused by alcohol exposure (58).

2. Metabolic homeostasis

The maintenance of metabolic homeostasis is critical for the survival of all species to sustain body structure and function. Metabolic homeostasis is achieved through complicated interactions between metabolic pathways that govern glucose, lipid and amino acid metabolism. Mitochondria are organelles, which integrate these metabolic pathways by serving a physical site for the production and recycling of metabolic intermediates.

2.1 Glucose metabolism

2.1.1. Overview

Glucose homeostasis is regulated through various complex processes including hepatic glucose output, glucose uptake, glucose utilization and storage. The main hormones regulating glucose homeostasis are insulin and glucagon, and the balance between these hormones determines glucose homeostasis. Insulin promotes glucose uptake in peripheral tissues (muscle and WAT), glycolysis and storage of glucose as glycogen in the fed state, while glucagon stimulates hepatic glucose production during fasting. Sirtuins influence many aspects of glucose homeostasis in several tissues such as muscle, WAT, liver and pancreas.

2.1.2 Gluconeogenesis

The body’s ability to synthesise glucose is vital in order to provide an uninterrupted supply of glucose to the brain and survive during starvation. Gluconeogenesis is a cytosolic process, in which glucose is formed from non-carbohydrate sources, such as amino acids, lactate, the glycerol portion of fats and tricarboxylic acid (59) cycle intermediates, during energy demand. This process, which occurs mainly in liver and kidney, shares some enzymes with glycolysis but it employs phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase and glucose-6-phosphatase to control the flow of metabolites towards glucose production. These three enzymes are stimulated by glucagon, epinephrine and glucocorticoids, whereas their activity is suppressed by insulin.

The role of mitochondrial sirtuins in the control of gluconeogenesis is not well established. SIRT3 is suggested to induce fasting-dependent hepatic glucose production from amino acids by deacetylating and activating the mitochondrial conversion of glutamate into the TCA cycle intermediate α-ketoglutarate, via the enzyme glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) (Fig. 1A) (60,61). As SIRT3−/− mice do not display changes in GDH activity (62), the mechanism requires further clarification. In contrast to SIRT3, SIRT4 inhibits GDH via ADP-ribosylation under basal dietary conditions (Fig. 1A-B) (12). Conversely, SIRT4 activity is suppressed during CR resulting in activation of GDH, which fuels the TCA cycle and possibly also gluconeogenesis (12). Therefore, mitochondrial sirtuins may function to support gluconeogenesis during energy limitation, but further research is required to understand the exact roles of mitochondrial sirtuins in gluconeogenesis.

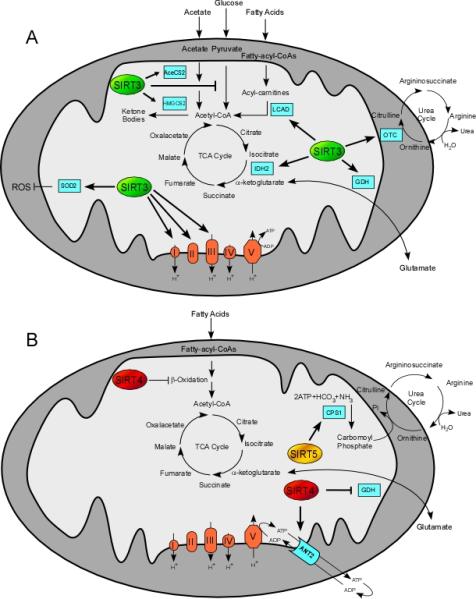

Figure 1. Summary of mitochondrial sirtuins’ role in mitochondrial pathways.

Mitochondrial sirtuins influence glucose, lipid and amino acid metabolism through affecting several aspects of mitochondrial physiology. Ovals indicate mitochondrial sirtuins SIRT3 (green), SIRT4 (red), and SIRT5 (yellow), whereas cyan rectangles represent the sirtuin targets. Overall, mitochondrial sirtuin functions highlight their importance in promoting metabolic adaptations during stress. For details see in the text.

2.1.3 Glucose uptake and insulin signaling

The entry of glucose into the cell is mediated by a set of glucose transporters. Insulin reduces blood glucose levels by increasing the translocation of the insulin-sensitive glucose transporter (GLUT4) from intracellular storage sites to the plasma membrane through the activation of a pathway of insulin signalling molecules. The binding of insulin to its receptor results in the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate proteins (IRS) tyrosine residues. In contrast, serine phosphorylation of IRS proteins by kinases such as JNK blunts insulin signalling. The down-stream targets of IRS proteins are phosphatidylinositol 3–kinase/Akt/Akt substrate of 160 kDa pathway, which regulates GLUT4 translocation, and the Ras-mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK/ERK) pathway, which mediates the effect of insulin on cell growth and differentiation cooperatively with phosphatidylinositol 3–kinase and Akt.

Of the mitochondrial sirtuins, SIRT3 is known to influence insulin sensitivity as SIRT3−/− mice have impaired glucose clearance (63). The loss of SIRT3 increased oxidative stress, enhanced JNK activity, decreased tyrosine, but increased serine phosphorylation of IRS-1 and reduced activation of Akt and ERK in myoblasts (63). Interestingly, a functional single nucleotide polymorphism of SIRT3 has been shown to associate with metabolic disease in humans (50). The impact of overexpression or activation of SIRT3 on insulin signaling has, however, not been investigated. Therefore, SIRT3 may have a role in the regulation of insulin sensitivity but clearly more studies are needed to address this issue.

2.1.3. Glucose utilization

Glycolysis is the first step of glucose utilization in the fed state. It is a cytosolic process leading to the conversion of glucose to pyruvate. Three irreversible reactions catalyzed by hexokinase (or glucokinase), phosphofructokinase and pyruvate kinase are the major sites for the regulation of glycolysis and are under allosteric and hormonal (insulin and glucagon) control. During anaerobic conditions (e.g. in exercising muscle), pyruvate is converted to lactate in a reaction catalyzed by lactate dehydrogenase. In aerobic conditions, pyruvate is converted to acetyl-CoA by pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, the rate of which is the major indicator of glucose oxidation. Acetyl-CoA, generated via glycolysis or after the degradation of fatty acids (FFAs), is used in the mitochondrial OXPHOS to form ATP (see Introduction). However, not all energy liberated in the respiratory chain is coupled to ATP formation. Uncoupling proteins are mitochondrial inner membrane proteins that can dissipate the proton gradient before it can be used to provide the energy for OXPHOS.

SIRT3 plays, together with SIRT1, an important role in the control of glucose utilization. First, SIRT1 represses glycolysis by inducing PGC-1α, which turns down the transcription of glycolytic genes (64). Second, SIRT1 deacetylates and reduces the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor α (HIF1α) (65) that stimulates expression of several genes governing glycolysis (66) and indirectly inactivates pyruvate dehydrogenase (67). SIRT3 inhibits the ROS-mediated stabilization of HIF1α by activating the antioxidant enzyme manganese superoxide dismutase (68). Moreover, SIRT3 activates GDH and isocitrate dehydrogenase 2 (IDH2) boosting NADH production and consequently, the antioxidant enzyme glutathione reductase (Fig. 1A) (69,70). In addition, SIRT3 deacetylates and diminishes the activity of cyclophilin D, thereby, promoting the dissociation of hexokinase II from the mitochondrial membrane and slowing down the entry of glucose into glycolysis (71).

Sirtuins are also critically involved in the regulation of the OXPHOS machinery. SIRT1 stimulates OXPHOS by activating PGC-1α, which increases mitochondrial biogenesis and transcription of OXPHOS genes (reviewd in (72)). SIRT3 can physically interact with subunits of complex I (Ndufa9), (73) complex II (SDHA) (74,75), and complex III (Fig. 1A) (63). SIRT3 also regulates mitochondrial protein translation by deacetylating the mitochondrial ribosomal protein L10 (76). SIRT3 and SIRT5 also bind to ATP synthase (77) and cytochrome c (78), respectively, but the physiological relevance of these interactions is currently unclear.

Collectively, it appears that SIRT1 and SIRT3 support proper mitochondrial oxidation and ATP production under basal conditions. This notion is bolstered by the finding that SIRT3 −/− mice exhibit significant reduction in basal ATP levels in several tissues (79). As tumor cells have a high reliance on glycolysis, known as the Warburg effect, the development of a cancer treatment, which shifts metabolism from glycolysis to oxidative metabolism is of interest.

2.1.4 Insulin secretion

Glucose is transported into the pancreatic β-cell via the GLUT2 transporter, which after glycolysis and OXPHOS leads to the generation of ATP. The subsequent increase in ATP/ADP ratio increases intracellular free calcium, which subsequently triggers the release of insulin.

SIRT4 blunts amino-acid induced insulin secretion during normal glucose conditions by repressing the activity of GDH (Fig. 1B), as discussed in the section 2.1.2 (12,80). However, GDH is released from the SIRT4-mediated inhibition via an undefined mechanism during CR, thereby enhancing amino acid-induced insulin secretion (12,80). Accordingly, in SIRT4 deficient mice GDH activity is enhanced in islets, leading to the enhancement of glucose and amino acid-stimulated insulin secretion (12). Moreover, SIRT4 inhibits glucose-stimulated insulin secretion possibly by modifying cytoplasmic ATP concentrations as SIRT4 interacts with adenine nucleotide translocator 2, which facilitates the transfer of mitochondrially produced ATP into the cytosol and ADP into the mitochondrial matrix (Fig. 1B) (80). Finally, SIRT3 may activate GDH by promoting its deacetylation (Fig. 1A) (see section 2.2.1) (78), but there is no evidence currently supporting the role of SIRT3 in insulin secretion via the modification of GDH activity (12). Taken together, SIRT4 may modulate amino-acid induced insulin secretion according to the actual metabolic demands of the organism, whereas evidence for a role of SIRT3 in insulin secretion is currently lacking.

2.2 Lipid metabolism

2.2.1 Overview

Lipid metabolism is a complex process involving lipid synthesis, uptake, storage and utilization. Lipid metabolism is controlled by many nutrients, intermediary metabolites and hormones. Several studies have also highlighted the role of sirtuins in the metabolism of different lipid types such as bile acids, cholesterol, and FFAs. As fatty acid synthesis and storage are mainly under the control of SIRT1 and they do not involve mitochondrial events, we focus here on lipid utilization through β-oxidation.

2.2.2 Lipid utilization

In response to energy demand such as during fasting and CR, FFAs are released from adipose tissue stores and transported to peripheral tissues, where they are taken up into cells via different fatty acid transporter proteins (81). After entering the cell, FFAs are converted to long chain acylcarnitines by carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 and transported across the inner mitochondrial membrane where they are converted to long chain acyl-CoAs that are used for β-oxidation, ultimately yielding acetyl-CoA, which then fuels OXPHOS. Hormones, nutrients, metabolic intermediates, and various signal transduction pathways can control FFA transport and β-oxidation.

Skeletal muscle utilizes FFAs as fuel during prolonged exercise. The switch to oxidative metabolism, i.e. the induction of mitochondrial biogenesis, fatty acid oxidation (FAO), and cellular respiration, is controlled by the opposing actions of corepressors, such as nuclear receptor co-repressor 1 (NCoR1) (82), and coactivators, such as PGC-1α (reviewed in (72,83)), which fine-tune the transcriptional activity of downstream targets controlling oxidative metabolism (84). A key event triggering oxidative metabolism is the activation of a cellular energy sensor, AMPK, by an increase in the AMP/ATP ratio during exercise or energy demand (85). Activated AMPK phosphorylates PGC-1α directly (86) and induces SIRT1 indirectly by elevating cellular NAD+ levels (21). Nonetheless, the activation of SIRT1 may be independent of AMPK in skeletal muscle during caloric restriction (87,88), although this is not always the case (89). Once SIRT1 is activated by NAD+, it deacetylates and locks PGC-1α in an active state (64), which together with diminished activity of NCoR1 (82) favors oxidative metabolism. Recent data have suggested that the nuclear abundance of the key PGC-1α acetyltransferase, GCN5 (general control of amino-acid synthesis 5) is also reduced in response to exercise, which also attenuates PGC-1α acetylation (90). However, further investigation is clearly needed to clarify the relationship between coactivators, such as GCN5 and PGC-1α, and corepressors, such as NCoR1, in the control of oxidative metabolism.

The mitochondrial sirtuins, SIRT3 and SIRT4, have been suggested to modulate FAO in skeletal muscle. The knock-down of SIRT4 enhances FAO rate and oxygen consumption in myotubes (Fig. 1B) (91). SIRT3-dependent deacetylation and activation of long-chain acyl CoA dehydrogenase (LCAD), the key enzyme involved in the oxidation of long-chain substrates, alters FAO in muscle (Fig. 1B) (92). Furthermore, SIRT3 may enhance fatty acid utilization in response to exercise and lack of nutrients through AMPK and PGC-1α, as phosphorylated AMPK and PGC-1α mRNA levels are significantly reduced in SIRT3−/− skeletal muscle (93). Moreover, SIRT3 and PGC-1α protein expression are increased in rat muscles in response to chronic exercise (52,94). Thus, concurrent changes of SIRT3 and PGC-1α expression in the muscle could indicate that SIRT3 may participate to the regulation of PGC-1α or vice versa, as PGC-1α regulates SIRT3 expression via ERRα in brown adipocytes (54); the mechanism(s) underlying these observations warrant future investigation.

FFAs are an important energy source in the liver during fasting, caloric restriction and high-fat feeding. Notably SIRT1 promotes mitochondrial FAO through activating PPARα and its coactivator PGC-1α (95), curbing the onset of diet-induced obesity (42,45). Accordingly, hepatic SIRT1−/− mice develop hepatic steatosis (95-97). Treatment with resveratrol or SIRT1 agonists ameliorates steatosis in diet-induced and genetically obese mouse models (98-101), and reduces liver lipid content in obese humans (43), thereby supporting the notion that SIRT1 activation enhances lipid utilization.

Of the mitochondrial sirtuins, SIRT3 is closely involved in the regulation of hepatic FAO as SIRT3 deacetylates and activates LCAD (Fig. 1A) (92). Like SIRT1−/− mice, SIRT3−/− mice are susceptible to hepatic steatosis (92). In contrast, SIRT4 seems to be a negative regulator of FAO since SIRT4 knock-down induces expression of genes involved in FAO and cellular respiration (Fig. 1B) (91). Collectively, these results argue that SIRT1 and SIRT3 activation and SIRT4 inhibition could stimulate fat oxidation and point to a potential role of these targets in the management of hepatic steatosis and steato-hepatitis.

2.2.3 Ketogenesis

Ketogenesis supports energy supply to extrahepatic tissues under fasting conditions, when liver mitochondria are overwhelmed by FAO. Acetoacetate, β-hydroxybutyrate, and acetone, referred to as ketone bodies, are produced in mitochondria from acetyl-CoA that is either generated from acetate, through the enzymes Acetyl-CoA Synthase1 (AceCS1) and AceCS2 (102,103), or from FAO. Acetyl-CoA is further converted into 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA, by hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase (HMGCS2), which is finally converted into the above-mentioned ketone bodies. SIRT3 deacetylates and activates both mitochondrial enzymes AceCS2 (104) and HMGCS2 (105) increasing the rate of ketogenesis upon fasting (Fig. 1A). Thus, the role of SIRT3 as a regulator of ketone bodies highlights again its important role in the adaptive response to fasting.

2.3. Urea metabolism

The urea cycle is a metabolic pathway by which excess nitrogen is incorporated into urea. In mammals the urea cycle takes primarily place in the liver and much less in the kidney (106), that is the main urea excretory organ. Ammonia production, and consequently urea cycle activity, increases during conditions that boost amino acid breakdown, such as CR and fasting (107). Since the urea cycle consists of five reactions two of which occur in mitochondria (107), is noteworthy that the three mitochondrial sirtuins may affect directly or indirectly urea cycle.

SIRT4 for example inhibits, through ADP-ribosylation, the mitochondrial enzyme GDH (Fig. 1B) (12), which converts glutamate to α-ketoglutarate and ammonia, thus attenuating ammonia production. Therefore, SIRT4 inhibition under CR (12) might contribute to the increase of ammonia production.

Also SIRT5, localized in the mitochondrial matrix, seems also to be involved in the control of urea cycle. Indeed, SIRT5 was reported to deacetylate -although the exact residues deacetylated were not established- and activate CPS1 (62), the enzyme catalyzing the first step of the urea cycle (Fig. 1B) (107). Consistently, SIRT5−/− mice CPS1 activity is reduced compared to wild type mice under food starvation with a consequent accumulation of ammonia into the blood (62). Despite this report suggesting that SIRT5 may be a CPS1 deacetylase, SIRT5 was recently shown to primarily demalonylate and desuccinylate proteins, including CPS1 (16). Further studies are hence required to elucidate how SIRT5 affects two distinct post-translational modifications in a single protein. Finally, ornithine transcarbamoylase (OTC) is deacetylated and activated by SIRT3 (Fig. 1A) (108). OTC is the second enzyme involved in the mitochondrial steps of the urea cycle (107). Thus, in SIRT3−/− mice the absence of SIRT3 hampers the stimulation of OTC in response to caloric restriction, causing alteration in the urea cycle metabolites levels. These observations reinforce the idea that sirtuins promote metabolic adaptations during stress, and suggest that sirtuin modulators could be valuable agents to improve these stress-inflicted abnormalities.

Summary

The recent discoveries in the biology of mitochondria have shed light on the metabolic regulatory roles of the sirtuin family. To maintain proper metabolic homeostasis, sirtuins sense cellular NAD+ levels, which reflect the nutritional status of the cells, and translate this information to adapt the activity of mitochondrial processes via posttranslational modifications and transcriptional regulation. SIRT1 and SIRT3 function to stimulate proper energy production via FAO and SIRT3 also protects from oxidative stress and ammonia accumulation during nutrient deprivation. SIRT4 seems to play role in the regulation of gluconeogenesis, insulin secretion and fatty acid utilization during times of energy limitation, while SIRT5 detoxifies excess ammonia that can accumulate during fasting. However, we are only at the beginning of our understanding of the roles of the mitochondrial sirtuins, SIRT3, SIRT4 and SIRT5 in complex metabolic processes. In the coming years, further research should identify and verify novel sirtuin targets in vivo and in vitro. We need also to elucidate the regulation and tissue-specific functions of these mitochondrial sirtuins, as well as to understand the potential crosstalk and synchrony between the different sirtuins in different subcellular compartments. Ultimately, the understanding of mitochondrial sirtuin functions may open new possibilities, not only for treatment of cancer and metabolic diseases characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction, but also for disease prevention and health maintenance.

Research agenda.

Studies are needed to identify and validate more targets of mitochondrial sirtuins.

The regulation of the activity of the mitochondrial sirtuin activity requires clarification.

Tissue-specific functions of the mitochondrial sirtuins needs to be determined using somatic knock-out mice.

Loss-of function approaches, should be complemented by gain-of-function studies.

The synchronization of the action of mitochondrial and nuclear sirtuins needs attention.

Acknowledgements

We thank team members of the Auwerx lab for discussions. EP is funded by the Academy of Finland and GLS by the Italian Association for Cancer Research. JA is the Nestlé Chair in Energy Metabolism. The work in the Auwerx laboratory is supported by grants of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Faculty of Life Science, the EU Ideas program (ERC-2008-AdG-23118), the Velux Stiftung, the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A-124713 and 31003A-125487).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Wallace DC, Fan W, Procaccio V. Mitochondrial energetics and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:297–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shore D, Squire M, Nasmyth KA. Characterization of two genes required for the position-effect control of yeast mating-type genes. EMBO J. 1984;3:2817–2823. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaeberlein M, McVey M, Guarente L. The SIR2/3/4 complex and SIR2 alone promote longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by two different mechanisms. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2570–2580. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.19.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imai S, Armstrong CM, Kaeberlein M, Guarente L. Transcriptional silencing and longevity protein Sir2 is an NAD-dependent histone deacetylase. Nature. 2000;403:795–800. doi: 10.1038/35001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto H, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J. Sirtuin functions in health and disease. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1745–1755. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moynihan KA, Grimm AA, Plueger MM, Bernal-Mizrachi E, et al. Increased dosage of mammalian Sir2 in pancreatic beta cells enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice. Cell Metab. 2005;2:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostoslavsky R, Chua KF, Lombard DB, Pang WW, et al. Genomic instability and aging-like phenotype in the absence of mammalian SIRT6. Cell. 2006;124:315–329. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford E, Voit R, Liszt G, Magin C, et al. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT7 is an activator of RNA polymerase I transcription. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1075–1080. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaquero A, Scher MB, Lee DH, Sutton A, et al. SirT2 is a histone deacetylase with preference for histone H4 Lys 16 during mitosis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1256–1261. doi: 10.1101/gad.1412706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhong L, Mostoslavsky R. Fine tuning our cellular factories: sirtuins in mitochondrial biology. Cell Metab. 2011;13:621–626. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao K, Harshaw R, Chai X, Marmorstein R. Structural basis for nicotinamide cleavage and ADP-ribose transfer by NAD(+)-dependent Sir2 histone/protein deacetylases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8563–8568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401057101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haigis MC, Mostoslavsky R, Haigis KM, Fahie K, et al. SIRT4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic beta cells. Cell. 2006;126:941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liszt G, Ford E, Kurtev M, Guarente L. Mouse Sir2 homolog SIRT6 is a nuclear ADP-ribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21313–21320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michishita E, McCord RA, Berber E, Kioi M, et al. SIRT6 is a histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylase that modulates telomeric chromatin. Nature. 2008;452:492–496. doi: 10.1038/nature06736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng C, Lu Z, Xie Z, Cheng Z, et al. The first identification of lysine malonylation substrates and its regulatory enzyme. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:M111–012658. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du J, Zhou Y, Su X, Yu JJ, et al. Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science. 2011;334:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1207861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canto C, Auwerx J. Targeting sirtuin 1 to improve metabolism: all you need is NAD(+)? Pharmacol Rev. 2012;64:166–187. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nrm3293. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Houtkooper RH, Canto C, Wanders RJ, Auwerx J. The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr Rev. 2010;31:194–223. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nisoli E, Tonello C, Cardile A, Cozzi V, et al. Calorie restriction promotes mitochondrial biogenesis by inducing the expression of eNOS. Science. 2005;310:314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1117728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canto C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Feige JN, Lagouge M, et al. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature. 2009;458:1056–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature07813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canto C, Jiang LQ, Deshmukh AS, Mataki C, et al. Interdependence of AMPK and SIRT1 for Metabolic Adaptation to Fasting and Exercise in Skeletal Muscle. Cell Metab. 2010;11:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bai P, Canto C, Oudart H, Brunyanszki A, et al. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through SIRT1 activation. Cell Metab. 2011;13:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbosa MT, Soares SM, Novak CM, Sinclair D, et al. The enzyme CD38 (a NAD glycohydrolase, EC 3.2.2.5) is necessary for the development of diet-induced obesity. Faseb J. 2007;21:3629–3639. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8290com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemoto S, Fergusson MM, Finkel T. Nutrient availability regulates SIRT1 through a forkhead-dependent pathway. Science. 2004;306:2105–2108. doi: 10.1126/science.1101731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashida S, Arimoto A, Kuramoto Y, Kozako T, et al. Fasting promotes the expression of SIRT1, an NAD+ -dependent protein deacetylase, via activation of PPARalpha in mice. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;339:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0391-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okazaki M, Iwasaki Y, Nishiyama M, Taguchi T, et al. PPARbeta/delta regulates the human SIRT1 gene transcription via Sp1. Endocr J. 2010;57:403–413. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noriega LG, Feige JN, Canto C, Yamamoto H, et al. CREB and ChREBP oppositely regulate SIRT1 expression in response to energy availability. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han L, Zhou R, Niu J, McNutt MA, et al. SIRT1 is regulated by a PPAR{gamma}-SIRT1 negative feedback loop associated with senescence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7458–7471. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen WY, Wang DH, Yen RC, Luo J, et al. Tumor suppressor HIC1 directly regulates SIRT1 to modulate p53-dependent DNA-damage responses. Cell. 2005;123:437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bai P, Canto C, Brunyanszki A, Huber A, et al. PARP-2 regulates SIRT1 expression and whole-body energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2011;13:450–460. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J, Padhye A, Sharma A, Song G, et al. A pathway involving farnesoid X receptor and small heterodimer partner positively regulates hepatic sirtuin 1 levels via microRNA-34a inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12604–12611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.094524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rane S, He M, Sayed D, Vashistha H, et al. Downregulation of miR-199a derepresses hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and Sirtuin 1 and recapitulates hypoxia preconditioning in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2009;104:879–886. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.193102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sasaki T, Maier B, Koclega KD, Chruszcz M, et al. Phosphorylation regulates SIRT1 function. PLoS One. 2008;3:e4020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gerhart-Hines Z, Dominy JE, Jr., Blattler SM, Jedrychowski MP, et al. The cAMP/PKA pathway rapidly activates SIRT1 to promote fatty acid oxidation independently of changes in NAD(+) Mol Cell. 2011;44:851–863. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nasrin N, Kaushik VK, Fortier E, Wall D, et al. JNK1 phosphorylates SIRT1 and promotes its enzymatic activity. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guo X, Williams JG, Schug TT, Li X. DYRK1A and DYRK3 promote cell survival through phosphorylation and activation of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13223–13232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Um JH, Park SJ, Kang H, Yang S, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase-deficient mice are resistant to the metabolic effects of resveratrol. Diabetes. 2010;59:554–563. doi: 10.2337/db09-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park SJ, Ahmad F, Philp A, Baar K, et al. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell. 2012;148:421–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1alpha. Cell. 2006;127:1109–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Timmers S, Konings E, Bilet L, Houtkooper RH, et al. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 2011;14:612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milne JC, Lambert PD, Schenk S, Carney DP, et al. Small molecule activators of SIRT1 as therapeutics for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;450:712–716. doi: 10.1038/nature06261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feige JN, Lagouge M, Canto C, Strehle A, et al. Specific SIRT1 activation mimics low energy levels and protects against diet-induced metabolic disorders by enhancing fat oxidation. Cell Metab. 2008;8:347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pacholec M, Bleasdale JE, Chrunyk B, Cunningham D, et al. SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and resveratrol are not direct activators of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8340–8351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zheng J, Ramirez VD. Inhibition of mitochondrial proton F0F1-ATPase/ATP synthase by polyphenolic phytochemicals. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130:1115–1123. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vetterli L, Brun T, Giovannoni L, Bosco D, et al. Resveratrol potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in INS-1E beta-cells and human islets through a SIRT1-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:6049–6060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi T, Wang F, Stieren E, Tong Q. SIRT3, a mitochondrial sirtuin deacetylase, regulates mitochondrial function and thermogenesis in brown adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13560–13567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Jing E, Grueter CA, et al. SIRT3 deficiency and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation accelerate the development of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell. 2011;44:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hallows WC, Lee S, Denu JM. Sirtuins deacetylate and activate mammalian acetyl-CoA synthetases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10230–10235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604392103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gurd BJ, Holloway GP, Yoshida Y, Bonen A. In mammalian muscle, SIRT3 is present in mitochondria and not in the nucleus; and SIRT3 is upregulated by chronic muscle contraction in an adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase-independent manner. Metabolism. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.09.016. (In Press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, Wall NR, et al. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;305:390–392. doi: 10.1126/science.1099196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giralt A, Hondares E, Villena JA, Ribas F, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha controls transcription of the Sirt3 gene, an essential component of the thermogenic brown adipocyte phenotype. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:16958–16966. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.202390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kong X, Wang R, Xue Y, Liu X, et al. Sirtuin 3, a new target of PGC-1alpha, plays an important role in the suppression of ROS and mitochondrial biogenesis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schirmer H, Pereira TC, Rico EP, Rosemberg DB, et al. Modulatory effect of resveratrol on SIRT1, SIRT3, SIRT4, PGC1alpha and NAMPT gene expression profiles in wild-type adult zebrafish liver. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;39:3281–3289. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1096-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lieber CS, Leo MA, Wang X, Decarli LM. Alcohol alters hepatic FoxO1, p53, and mitochondrial SIRT5 deacetylation function. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shepard BD, Tuma PL. Alcohol-induced protein hyperacetylation: mechanisms and consequences. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1219–1230. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gainsford T, Willson TA, Metcalf D, Handman E, et al. Leptin can induce proliferation, differentiation, and functional activation of hemopoietic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 1996;93:14564–14568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lombard DB, Alt FW, Cheng HL, Bunkenborg J, et al. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8807–8814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01636-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schlicker C, Gertz M, Papatheodorou P, Kachholz B, et al. Substrates and regulation mechanisms for the human mitochondrial sirtuins Sirt3 and Sirt5. J Mol Biol. 2008;382:790–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakagawa T, Lomb DJ, Haigis MC, Guarente L. SIRT5 Deacetylates carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 1 and regulates the urea cycle. Cell. 2009;137:560–570. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jing E, Emanuelli B, Hirschey MD, Boucher J, et al. Sirtuin-3 (Sirt3) regulates skeletal muscle metabolism and insulin signaling via altered mitochondrial oxidation and reactive oxygen species production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:14608–14613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111308108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, et al. Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1. Nature. 2005;434:113–118. doi: 10.1038/nature03354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lim JH, Lee YM, Chun YS, Chen J, et al. Sirtuin 1 modulates cellular responses to hypoxia by deacetylating hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Mol Cell. 2010;38:864–878. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hu CJ, Iyer S, Sataur A, Covello KL, et al. Differential regulation of the transcriptional activities of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1alpha) and HIF-2alpha in stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3514–3526. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.9.3514-3526.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qiu X, Brown K, Hirschey MD, Verdin E, et al. Calorie restriction reduces oxidative stress by SIRT3-mediated SOD2 activation. Cell Metab. 2010;12:662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Someya S, Yu W, Hallows WC, Xu J, et al. Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell. 2010;143:802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Finley LW, Carracedo A, Lee J, Souza A, et al. SIRT3 opposes reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism through HIF1alpha destabilization. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shulga N, Wilson-Smith R, Pastorino JG. Sirtuin-3 deacetylation of cyclophilin D induces dissociation of hexokinase II from the mitochondria. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:894–902. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 72.Fernandez-Marcos PJ, Auwerx J. Regulation of PGC-1alpha, a nodal regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93:884S–890. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.001917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ahn BH, Kim HS, Song S, Lee IH, et al. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14447–14452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803790105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Finley LW, Haas W, Desquiret-Dumas V, Wallace DC, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase is a direct target of sirtuin 3 deacetylase activity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cimen H, Han MJ, Yang Y, Tong Q, et al. Regulation of succinate dehydrogenase activity by SIRT3 in mammalian mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2010;49:304–311. doi: 10.1021/bi901627u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang Y, Cimen H, Han MJ, Shi T, et al. NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial protein synthesis by deacetylation of the ribosomal protein MRPL10. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:7417–7429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.053421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Law IK, Liu L, Xu A, Lam KS, et al. Identification and characterization of proteins interacting with SIRT1 and SIRT3: implications in the anti-aging and metabolic effects of sirtuins. Proteomics. 2009;9:2444–2456. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schlicker C, Gertz M, Papatheodorou P, Kachholz B, et al. Substrates and regulation mechanisms for the human mitochondrial sirtuins Sirt3 and Sirt5. Journal of molecular biology. 2008;382:790–801. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finkel T, Deng CX, Mostoslavsky R. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature. 2009;460:587–591. doi: 10.1038/nature08197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ahuja N, Schwer B, Carobbio S, Waltregny D, et al. Regulation of insulin secretion by SIRT4, a mitochondrial ADP-ribosyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33583–33592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Eaton S. Control of mitochondrial beta-oxidation flux. Prog Lipid Res. 2002;41:197–239. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yamamoto H, Williams EG, Mouchiroud L, Canto C, et al. NCoR1 is a conserved physiological modulator of muscle mass and oxidative function. Cell. 2011;147:827–839. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:728–735. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Coste A, Louet JF, Lagouge M, Lerin C, et al. The genetic ablation of SRC-3 protects against obesity and improves insulin sensitivity by reducing the acetylation of PGC-1{alpha} Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17187–17192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808207105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Canto C, Auwerx J. AMP-activated protein kinase and its downstream transcriptional pathways. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:3407–3423. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0454-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jager S, Handschin C, St-Pierre J, Spiegelman BM. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) action in skeletal muscle via direct phosphorylation of PGC-1alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12017–12022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705070104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gonzalez AA, Kumar R, Mulligan JD, Davis AJ, et al. Effects of aging on cardiac and skeletal muscle AMPK activity: basal activity, allosteric activation, and response to in vivo hypoxemia in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R1270–1275. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00409.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schenk S, McCurdy CE, Philp A, Chen MZ, et al. Sirt1 enhances skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity in mice during caloric restriction. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:4281–4288. doi: 10.1172/JCI58554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Palacios OM, Carmona JJ, Michan S, Chen KY, et al. Diet and exercise signals regulate SIRT3 and activate AMPK and PGC-1alpha in skeletal muscle. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:771–783. doi: 10.18632/aging.100075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Philp A, Chen A, Lan D, Meyer GA, et al. Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) Deacetylase Activity Is Not Required for Mitochondrial Biogenesis or Peroxisome Proliferator-activated Receptor-{gamma} Coactivator-1{alpha} (PGC-1{alpha}) Deacetylation following Endurance Exercise. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30561–30570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.261685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nasrin N, Wu X, Fortier E, Feng Y, et al. SIRT4 regulates fatty acid oxidation and mitochondrial gene expression in liver and muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31995–32002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.124164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hirschey MD, Shimazu T, Goetzman E, Jing E, et al. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature. 2010;464:121–125. doi: 10.1038/nature08778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Palacios OM, Carmona JJ, Michan S, Chen KY, et al. Diet and exercise signals regulate SIRT3 and activate AMPK and PGC-1alpha in skeletal muscle. Aging (Albany NY) 2009;1:771–783. doi: 10.18632/aging.100075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hokari F, Kawasaki E, Sakai A, Koshinaka K, et al. Muscle contractile activity regulates Sirt3 protein expression in rat skeletal muscles. Journal of applied physiology. 2010;109:332–340. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00335.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Purushotham A, Schug TT, Xu Q, Surapureddi S, et al. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of SIRT1 alters fatty acid metabolism and results in hepatic steatosis and inflammation. Cell Metab. 2009;9:327–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang RH, Li C, Deng CX. Liver steatosis and increased ChREBP expression in mice carrying a liver specific SIRT1 null mutation under a normal feeding condition. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:682–690. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xu F, Gao Z, Zhang J, Rivera CA, et al. Lack of SIRT1 (Mammalian Sirtuin 1) activity leads to liver steatosis in the SIRT1+/− mice: a role of lipid mobilization and inflammation. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2504–2514. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ajmo JM, Liang X, Rogers CQ, Pennock B, et al. Resveratrol alleviates alcoholic fatty liver in mice. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology. 2008;295:G833–842. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90358.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamazaki Y, Usui I, Kanatani Y, Matsuya Y, et al. Treatment with SRT1720, a SIRT1 Activator, Ameliorates Fatty Liver with Reduced Expression of Lipogenic Enzymes in MSG Mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90997.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Walker AK, Yang F, Jiang K, Ji JY, et al. Conserved role of SIRT1 orthologs in fasting-dependent inhibition of the lipid/cholesterol regulator SREBP. Genes Dev. 2010;24:1403–1417. doi: 10.1101/gad.1901210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ponugoti B, Kim DH, Xiao Z, Smith Z, et al. SIRT1 deacetylates and inhibits SREBP-1C activity in regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33959–33970. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.122978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ikeda Y, Yamamoto J, Okamura M, Fujino T, et al. Transcriptional regulation of the murine acetyl-CoA synthetase 1 gene through multiple clustered binding sites for sterol regulatory element-binding proteins and a single neighboring site for Sp1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:34259–34269. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103848200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fujino T, Kondo J, Ishikawa M, Morikawa K, et al. Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2, a mitochondrial matrix enzyme involved in the oxidation of acetate. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11420–11426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008782200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS, et al. Reversible lysine acetylation controls the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme acetyl-CoA synthetase 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:10224–10229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603968103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shimazu T, Hirschey MD, Hua L, Dittenhafer-Reed KE, et al. SIRT3 deacetylates mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase 2 and regulates ketone body production. Cell Metab. 2010;12:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mullins Von Dreele M, Banks RO. Urea synthesis in the canine kidney. Ren Physiol. 1985;8:73–79. doi: 10.1159/000173038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Watford M. The urea cycle: a two-compartment system. Essays Biochem. 1991;26:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hallows WC, Yu W, Smith BC, Devries MK, et al. Sirt3 promotes the urea cycle and fatty acid oxidation during dietary restriction. Mol Cell. 2011;41:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]