Abstract

Signals that promote germ cell self-renewal by preventing premature meiotic entry are well understood. However, signals that control mitotic proliferation to promote meiotic differentiation have not been well characterized. In Caenorhabditis elegans, GLP-1 Notch signalling promotes the proliferative fate by preventing premature meiotic entry. The germline niche cell, which is the source of the ligand for GLP-1, spatially restricts GLP-1 signalling and thus enables the germ cells that have moved away from the niche to enter meiosis. Here, we show that the suppression of RAS/MAP kinase signalling in the mitotic and meiotic-entry regions is essential for the regulation of the mitosis-meiosis switch by niche signalling. We provide evidence that the conserved PUF family RNA-binding protein PUF-8 and the RAS GAP protein GAP-3 function redundantly to suppress the LET-60 RAS in the mitotic and meiotic entry regions. Germ cells missing both PUF-8 and GAP-3 proliferate in an uncontrolled fashion and fail to undergo meiotic development. MPK-1, the MAP kinase downstream of the LET-60 RAS, is prematurely activated in these cells; downregulation of MPK-1 activation eliminates tumours and restores differentiation. Our results further reveal that PUF-8 negatively regulates LET-60 expression at a post-transcriptional step. LET-60 is misexpressed in the puf-8(-) mutant germlines and PUF-8 physically interacts with the let-60 3′ UTR. Furthermore, PUF-8 suppresses let-60 3′ UTR-mediated expression in the germ cells that are transitioning from the mitotic to meiotic fate. These results reveal that PUF-8-mediated inhibition of the RAS/MAPK pathway is essential for mitotic-to-meiotic fate transition.

Keywords: PUF-8, GAP-3, RAS, MAPK, C. elegans, Germ cells, Mitosis-meiosis decision

INTRODUCTION

Maintenance of a balance between proliferation and meiotic development is crucial for the continuous generation of gametes. Although uncontrolled proliferation leads to germline tumours, entry of all germ cells into meiosis depletes the self-renewing germline stem cells (GSCs). In both invertebrates and vertebrates, signals from adjacent somatic cells - called the GSC niche - initiate GSC self-renewal programmes (Kimble, 2011; Lehmann, 2012). Studies on different model organisms indicate that the primary function of GSC niche signal is to prevent premature entry into meiosis/differentiation. For example, in the absence of GLP-1/Notch signalling from the niche, C. elegans GSCs prematurely enter meiosis and form sperm (Crittenden et al., 2002; Kadyk and Kimble, 1998; Lamont et al., 2004). Similarly, DPP signalling from the Drosophila GSC niche inhibit the transcription of the differentiation-promoting factor Bam (Song et al., 2004; Xie and Spradling, 1998). These observations underscore the importance of blocking premature differentiation in the maintenance of GSCs. However, the signals that directly promote proliferation, and whether the downregulation of such signals is crucial for meiotic entry, are still poorly understood.

In C. elegans, removal of MAP kinase pathway components lin-45 RAF, mek-2 MEK or MPK-1 ERK enhances the premature meiotic entry phenotype of the partial loss of glp-1 function (Lee et al., 2007b). Thus, MAP kinase signalling promotes the mitotic proliferative fate. However, null mutations in any of the above three genes do not affect the mitotic-to-meiotic fate switch. Furthermore, the phosphorylated MPK-1, the active form, is not detected in germ cells until the mid-pachytene stage (Lee et al., 2007b). Thus, the role of RAS/MAPK signalling in the germ cell fate decision, under wild-type conditions, is not known.

The C. elegans PUF protein PUF-8 promotes both proliferation and differentiation. In the mitotic region, it functions redundantly with another RNA-binding protein called MEX-3 to promote GSC proliferation (Ariz et al., 2009). Germ cells lacking both these proteins do not proliferate even when the meiotic-entry block is intact. By contrast, PUF-8 promotes meiotic progression in primary spermatocytes (Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003). In its absence, primary spermatocytes exit meiotic development and dedifferentiate. As one of our approaches to identify the downstream effectors of PUF-8, we performed a genetic screen and isolated a number of mutants that were sterile only in the absence of PUF-8. Significantly, these mutants group into two classes with opposite phenotypes - severely reduced number of germ cells in one class and germ cell tumour in the other. One of the latter category maps to gap-3, which encodes a C. elegans orthologue of the GTPase-activating protein (GAP) (Stetak et al., 2008). GAPs downregulate MAPK signalling by promoting the hydrolysis of GTP bound to RAS, an upstream activator of this signalling pathway. Our results reveal that PUF-8 suppresses expression of LET-60 RAS in the zone where germ cells switch from the proliferative mode to meiotic differentiation, and that the uncontrolled proliferation observed in the puf-8(-) gap-3(-) double mutant is due to LET-60-dependant ectopic activation of MPK-1 in this zone. Thus, these results identify PUF-8 as a crucial upstream regulator of MAPK signalling and highlight the importance of the negative regulation of this signalling in the mitosis-meiosis decision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. elegans strains

All worm strains were maintained at 20°C as described (Brenner, 1974), with the exception that all transgenic lines were kept at 25°C to avoid germline silencing of transgenes (Strome et al., 2001). Transgenes were introduced into different mutant backgrounds by standard genetic crosses. The strains used in this study are listed in supplementary material Table S2.

Mutagenesis

The design of the genetic screen used to isolate mutants that display synthetic phenotype with puf-8 is shown in supplementary material Fig. S1. Mutagenesis was carried out as described earlier using EMS (Brenner, 1974). Briefly, about 200 L4 larvae of IT60 strain (see supplementary material Table S2 for genotype) were incubated in 4 ml M9 medium containing 50 mM EMS for 6 hours at 20°C. The worms were washed, and allowed to recover on OP50 E. coli lawns for about 12 hours at 20°C. They were then transferred to fresh lawns and embryos (F1 generation) were collected. About 300 F1 adults were cloned and the F2 embryos were collected for 24 hours. F2 progeny were examined for sterility.

Transgenic worms

The transgene construct pSV39, which expresses the GFP::GAP-3 fusion protein, was made as follows: GAP-3 ORF was amplified in two parts using primers KS3575 and KS3576 on wild-type cDNA and primers KS3575 and KS3102 wild-type genomic DNA (see supplementary material Table S3 for primer sequences), and cloned in pSV2 using a standard TA-cloning procedure (Mainpal et al., 2011). These two fragments were then combined in one construct pSV37 through restriction digestion and ligation. The 3018 bp GAP-3 ORF containing the first intron was amplified using primers KS3575 and KS3576, and introduced between SpeI and NarI sites of pKS114 (Mainpal et al., 2011) to generate pSV39.

The transgene construct pAK9, which expresses PUF-8::9×HA::GFP was made as follows: KS3788 and KS3789 (see supplementary material Table S6 for primer sequences) were annealed, end-filled and the resulting fragment was cloned at the SpeI site in pPK44, a plasmid that expresses PUF-8::GFP fusion protein under the control of the puf-8 promoter, to generate pAK8. KS3791 and KS3792 were annealed, end-filled and cloned at the Cfr9I site of pAK8 to generate pAK10. KS3794 and KS3795 were annealed, end-filled and cloned at the PauI site of pAK10 to generate pAK9.

The GFP-3′ UTR transgene fusions were made as follows: respective 3′ UTR sequences were PCR-amplified from wild-type genomic DNA using the corresponding primers (see supplementary material Table S5 for primer sequences) and inserted at the Bsp120I site of pKS114 (Mainpal et al., 2011). Mutations in the let-60 3′ UTR sequences were introduced through PCR primers described in supplementary material Table S6.

Each transgene construct was generated in duplicate and were introduced into unc-119(-) strain by biolistic bombardment, as described earlier (Jadhav et al., 2008; Praitis et al., 2001). Results of transgene expression patterns presented here are representatives of at least eight independent lines; in each case, at least 20 worms per line were examined.

Immunostaining and fluorescence microscopy

Dissection, fixation of gonads and immunostaining were performed as described earlier (Ariz et al., 2009), except that for detecting LET-60, dissected gonads were fixed in 2% formaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature, followed by methanol at -20°C for 5 minutes in a glass tube. We confirmed the specificity of this antibody by staining gonads depleted of LET-60 by RNAi (supplementary material Fig. S6). These gonads were not freeze-cracked. For detecting dpMPK-1, mouse monoclonal antibodies against dpMPK-1 (Sigma) was used at 1:500 dilution; for LET-60, goat polyclonal anti-LET-60 antibodies (Santa Cruz; catalogue number sc 9210) were used at 1:50 dilution. Anti-PH3 and anti-HIM-3 antibodies have been described previously (Ariz et al., 2009). Fluorescent images of immunostained gonads and transgenic worms expressing GFP reporters were examined using a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss Axioskop II mot plus) and images were acquired using a CCD camera (Axiocam HRm). All images presented are representative of at least 50 gonads per experiment; each immunostaining and DAPI-staining was repeated at least four times.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

Mobility shift experiments were carried out as described previously (Jadhav et al., 2008). Template DNA fragments for in vitro transcriptions were generated as follows: for fragment 1, fragment 2, fragment 3, fragment 4 and fragment 5 of let-60 3′ UTR RNA, respective sequences were PCR amplified from wild-type genomic DNA using the corresponding primers (see supplementary material Table S6 for primer sequences). These fragments were cloned into pSV2 using the standard TA cloning method (Mainpal et al., 2011). Each fragment was checked for orientation by using KS2808 and the fragment-specific reverse primer. From such positive clones, for each fragment, in vitro transcription template was made by PCR amplification using KS2808 and the fragment-specific reverse primer. The final plasmids thus generated were used to PCR-amplify the template for in vitro transcription using KS3432 and KS 3441 primers. Mutations in fragment 4 were introduced through PCR primers (see supplementary material Table S6 for primer sequences).

Co-immunoprecipitation and RT-PCR

All the steps for co-immunoprecipitation were carried out at 4°C. About 150,000 synchronized IT722 adult hermaphrodites (see supplementary material Table S2 for genotype) were homogenized using a dounce homogenizer in homogenization buffer [100 mM NaCl, 25 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 4 mM Na3VO4, 3 mM NaF, 0.1% IGEPAL C-30 (Sigma) supplemented with protease inhibitor (Sigma) and RNase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific)]. Homogenate was cleared by centrifuging at 14,000 g for 20 minutes. For immunoprecipitation, 100 μl of the homogenate was pre-cleared with Protein A beads (Genescript) and incubated for 3 hours with 1.5 μg of anti-HA antibody (Genescript). Again, Protein A beads were added and sample was incubated for 2 hours. Beads were collected by centrifugation and washed three times with homogenization buffer. For RT-PCR, RNA was isolated from the above beads, using TRI Reagent (Sigma), treated with DNase I for 30 minutes (Fermentas), extracted with phenol: chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol and dissolved in 20 μl of RNase-free water. Ten microlitres of this total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis, and used for PCR amplification using mRNA-specific primers. RNA-mediated interference was performed by a feeding method described previously (Timmons et al., 2001).

RESULTS

puf-8 genetically interacts with several genes to control both mitosis and meiosis

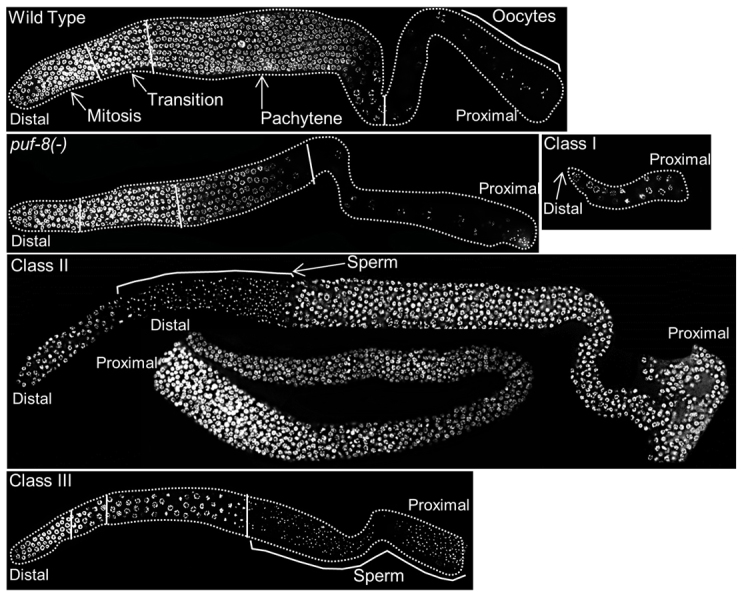

Even null alleles of puf-8 display a temperature-sensitive phenotype. At 20°C, all puf-8(-) worms are fertile, albeit they have a smaller germline and produce fewer progeny. However, at 25°C, 100% of the puf-8(-) worms are sterile (Ariz et al., 2009; Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003). C. elegans germ cell development is significantly accelerated at the higher temperature. Processes involving multiple redundant factors are probably more sensitive to loss of any one of these factors when the rate is accelerated. We reasoned the temperature sensitivity of puf-8(-) phenotype is probably due to such a phenomenon, and decided to identify other genes that function redundantly with puf-8. Indeed, puf-8 does function redundantly with mex-3 to promote mitotic proliferation of germ cells, and fbf-1 and lip-1 in sperm-oocyte switch (Ariz et al., 2009; Bachorik and Kimble, 2005; Morgan et al., 2010). To identify such additional genes, we carried out a genetic screen that was designed to isolate mutants that display sterile phenotype only in the puf-8(-/-) genetic background at 20°C. This screen yielded 71 alleles, of which 37 belong to 29 complementation groups. These could be grouped into three phenotypic classes (see supplementary material Fig. S1 for details of the genetic screen). Class I mutant gonads had very few germ cells; class II mutants produced excess amounts of mitotic germ cells; and germ cells in the class III mutant hermaphrodites failed to switch from spermatogenesis to oogenesis (Fig. 1). Each class contained multiple complementation groups: 16 in class I, three in class II and 10 in class III (supplementary material Table S1). Within class II, two types of germ cell tumour were observed - in two alleles, kp1 and kp65 (belonging to one complementation group), proliferation was in the distal part of the gonad where GSCs normally reside. In the other two class II complementation groups, the tumourous proliferation was in the proximal part of the gonad, more like the dedifferentiation observed in the puf-8(-) single mutant grown at 25°C. These results show that puf-8 genetically interacts with several genes to regulate proliferation as well as meiotic development, and suggest that PUF-8 plays a pivotal role in the mitosis-meiosis balance.

Fig. 1.

Mutants synthetic sterile with puf-8(-) belong to three distinct classes. Dissected gonads, stained with the DNA-binding dye DAPI, are shown. Only the germline nuclei are visible. In this and subsequent figures, the distal mitotic region is oriented towards the left and the proximal region containing gametes to the right. Regions of the germline with germ cells at different stages of development are marked with solid white lines and labelled in the wild-type image. Class I mutants have very few germ cells. Class II mutants have tumourous germlines. This class has two subclasses. In one, the distal mitotic region is followed by a region with sperm, which is then followed by mitotically proliferating germ cells. In the second subclass, only mitotic germ cells were observed. Class III mutants fail to switch from spermatogenesis to oogenesis and make more sperm than do wild type.

puf-8 functions redundantly with gap-3 to suppress mitotic proliferation

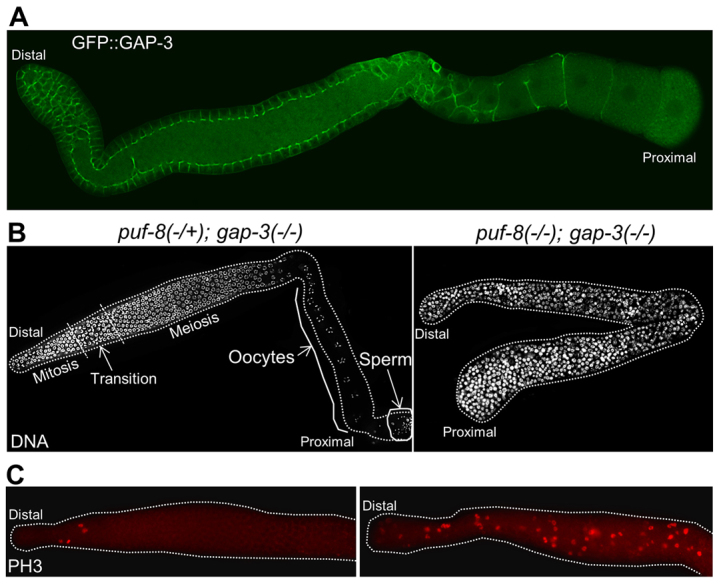

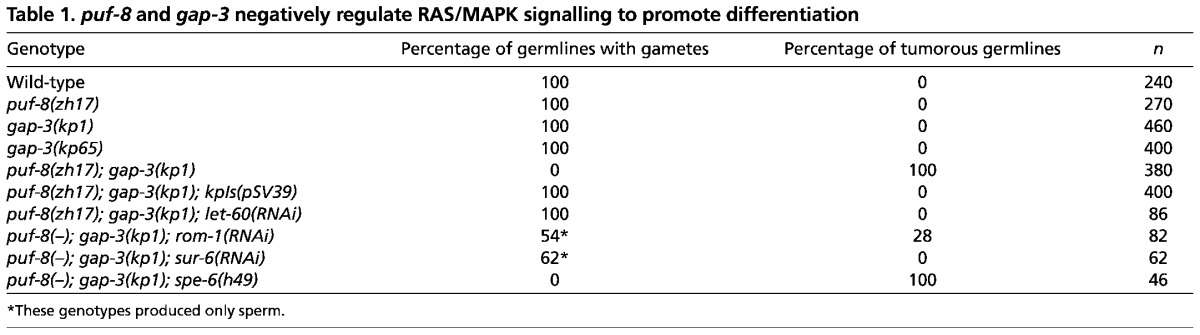

We determined the chromosomal position of kp1 and kp65 using standard three-factor genetic crosses, RNAi, DNA sequencing and transgene rescue. Three-factor crosses using visible and SNP markers placed these mutations within the map positions -12.5 and -11.0 on chromosome I. There were 35 open reading frames (ORF) within this region. RNAi screening of these ORFs identified gap-3, which encodes a RasGAP (Stetak et al., 2008), as a potential candidate for the complementation group represented by kp1 and kp65. Sequencing the gap-3 region of genomic DNA from kp1 and kp65 worms revealed point mutations within the GAP-3 coding sequence. In kp1, a C-to-T change converts the CAA codon for glutamine at amino acid position 516 into the TAA stop codon. In kp65, a T-to-G change converts the TTA codon for leucine at amino acid position 806 into the TGA stop codon. The shorter protein predicted for kp65 completely eliminates the 250 amino acid GAP domain and kp1 deletes the last 70 amino acids of this domain (supplementary material Fig. S2). To further confirm our mapping results, we tested whether a transgene carrying the GAP-3-coding region would rescue the kp1 allele. For this, we generated transgenic lines in which GFP::GAP-3 fusion was expressed in the germline using pie-1 promoter. This transgene is expressed in the germline, where GFP::GAP-3 preferentially localizes to the cell membrane of all germ cells except the oocyte that is about to ovulate (Fig. 2A). As shown in Table 1, this transgene was able to rescue the kp1 mutation, thus indicating kp1 is indeed an allele of gap-3. We conclude kp1 and kp65 are alleles of gap-3.

Fig. 2.

Adult puf-8(-/-); gap-3(-/-) germline contain only mitotic germ cells. (A) Distribution pattern of GAP-3::GFP fusion protein expressed in the germline using the upstream and downstream sequences of pie-1. The fusion protein localizes predominantly to the cell membrane of germ cells. (B) Dissected, DAPI-stained gonads. Although the puf-8(-/+); gap-3(-/-) heterozygous germline contains oocytes in the proximal region, the germline homozygous for both mutations does not have oocytes. The broken lines in the left image mark the boundaries among the indicated stages. Only mitotic cells were observed in the double mutant gonad shown on the right. (C) Dissected gonads immunostained for the mitosis marker phosphohistone H3 (PH3). Unlike the puf-8(-/+); gap-3(-/-) heterozygous germline, which contains PH3-positive cells only in the distal part, the double mutant has PH3-positive cells throughout the germline. In addition, the number of PH-3-positive cells in the distal region in the double mutant is significantly more than the single mutant.

Table 1.

puf-8 and gap-3 negatively regulate RAS/MAPK signalling to promote differentiation

As expected from the design of the genetic screen, neither gap-3(kp1) nor gap-3(kp65) single mutants displayed any observable defects. Both spermatogenesis and oogenesis were normal in these worms and they yielded viable fertile progeny at both 20°C and 25°C (Fig. 2B, Table 1). As reported earlier, the puf-8(-) single mutant was fertile at 20°C (Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003) (data not shown). By contrast, both puf-8(-); gap-3(kp1) and puf-8(-); gap-3(kp65) double mutants were 100% sterile at this temperature. Although a small percentage of the double mutants formed a few sperm, they did not produce any oocytes. Instead, mitotically proliferating cells were observed throughout the gonad in 100% of these worms, including the few in which a few sperm were observed (Fig. 2C). These observations show that puf-8 and gap-3 function in a redundant fashion to inhibit ectopic germ cell proliferation.

PUF-8 and GAP-3 function redundantly to control RAS/MAPK signalling in germ cells

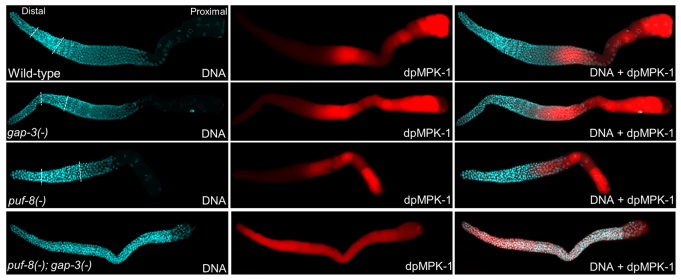

A tight control of RAS/MAPK signalling is crucial for normal levels of cell proliferation in different developmental contexts. Excessive signalling is responsible for several types of cancer in humans (Malumbres and Barbacid, 2003). RAS, the membrane-bound upstream activator of this signalling pathway, is a G protein and is active only in the GTP-bound form. Its intrinsic GTPase activity is stimulated by RAS GTPase-activating proteins (RasGAPs). Thus, RasGAPs act as negative regulators of RAS/MAPK pathway (Bernards, 2003). The C. elegans genome encodes three RasGAPs, namely GAP-1, GAP-2 and GAP-3 (Stetak et al., 2008). Each of these proteins controls the activity of the RAS protein LET-60 in different tissues. For example, GAP-3 has been shown to be the primary repressor of LET-60 in germ cells progressing through meiosis (Stetak et al., 2008). Therefore, we wanted to determine whether the RAS/MAPK signalling was altered in puf-8(-) gap-3(-) worms. For this, we immunostained dissected gonads with antibodies specific for the phosphorylated MPK-1 (dpMPK-1), which is the active form of the downstream kinase activated by RAS/MAPK signalling (Lee et al., 2007b). In the wild-type controls, dpMPK-1 expression could be observed in the mid-pachytene germ cells and oocytes, which is similar to the dpMPK-1 expression pattern reported earlier (Lee et al., 2007b). There were no noticeable variations in the levels or distribution pattern of dpMPK-1 in the puf-8(-) and gap-3(-) single mutants from the wild type. By contrast, in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant gonads, dpMPK-1 was present throughout the gonad in all germ cells, and the immunofluorescence intensity was particularly higher in the region where germ cells exit proliferation and begin meiotic development (Fig. 3). These results show that PUF-8 and GAP-3 act redundantly to suppress MPK-1 activation in germ cells.

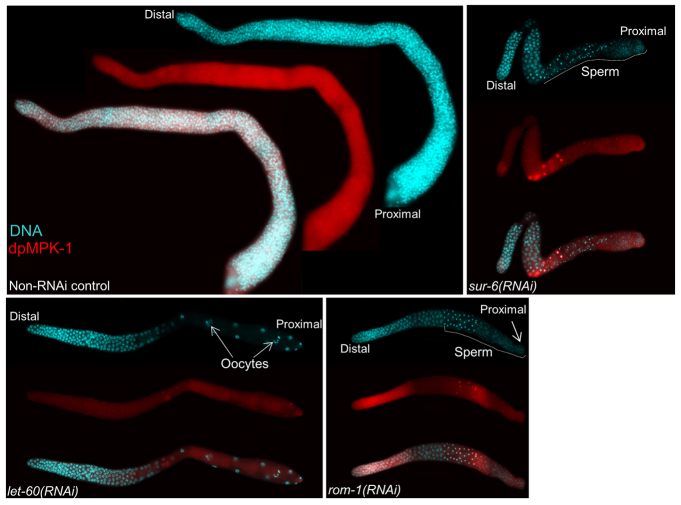

Fig. 3.

MPK-1 is ectopically activated in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant. Dissected adult gonads of the indicated genotypes stained with both DAPI (DNA) and anti-dpMPK-1 antibodies (dpMPK-1) to visualize the nuclear morphology and the active form of MPK-1, respectively. In the distal part of the germline, active MPK-1 level is significantly higher in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant than the wild-type (WT) and both single mutants. Broken lines mark the boundaries among mitotic, transition and meiotic regions. In the double mutant, only mitotic germ cells were present throughout the gonad.

PUF-8- and GAP-3-mediated suppression of RAS/MAPK signalling is essential for the control of mitotic proliferation

To test whether the increased RAS/MAPK signalling is the cause of a tumour phenotype, we downregulated several RAS/MAPK pathway components (supplementary material Table S4) (Sundaram, 2006) in puf-8(-); gap-3(-) worms by RNAi. Although depletion of any one of these components reduced the tumourous proliferation, the extent of this reduction was significantly higher when LET-60, ROM-1 or SUR-6 was depleted by RNAi. In addition to tumour reduction, majority of these three RNAi gonads produced sperm. Strikingly, let-60(RNAi) arrested the tumour phenotype completely, and restored fertility (Table 1). Furthermore, immunostaining with anti-dpMPK-1 antibodies revealed a significant reduction in the levels of dpMPK-1 in these RNAi gonads (Fig. 4). These results show that the uncontrolled mitotic proliferation of puf-8(-); gap-3(-) worms is due to premature activation of RAS/MAPK signalling. We conclude PUF-8 and GAP-3 negatively regulate RAS/MAPK signalling to control mitotic proliferation.

Fig. 4.

Depletion of MAP kinase pathway components suppress puf-8(-); gap-3(-) phenotype. Dissected gonads of puf-8(-); gap-3(-) young adults following the indicated RNAi treatments stained as described in Fig. 3. Although let-60(RNAi) reduces dpMPK-1 levels considerably throughout the germline, sur-6(RNAi) and rom-1(RNAi) does so in the early pachytene region. In all three cases, tumourous proliferation is abolished and gametes are seen in the proximal region - oocytes in let-60(RNAi) and sperm in sur-6(RNAi) and rom-1(RNAi). See text and Table 1 for additional information.

PUF-8 and GAP-3 are not essential for the onset of meiosis, but are essential for the maintenance of mitosis-meiosis transition in the adult

Mitotic proliferation in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant appeared to be uncontrolled as the gonads quickly filled up with mitotic germ cells and enlarged within 48 hours of L4-adult moult. Two types of germline tumours have been observed in C. elegans. The first type results from the failure of germ cells to switch from mitotic to meiotic fate. In this case, mitotically cycling GSCs present at the distal part of the gonad fail to enter meiosis and instead proliferate in an uncontrolled fashion (Berry et al., 1997; Hansen et al., 2004a). In the second type, the initial mitotic-to-meiotic cell fate switch is unaffected, but the germ cells exit meiosis and dedifferentiate into mitotically cycling cells (Francis et al., 1995a; Francis et al., 1995b; Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003). As an initial attempt to determine the type of tumour observed in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) worms, we blocked meiotic progression by generating the puf-8(-); gap-3(-); spe-6(-) triple mutant. SPE-6 is essential for meiotic progression and the spe-6(-) mutant germ cells arrest at late prophase I (Varkey et al., 1993). As shown in Table 1, tumorous proliferation was also observed in this triple mutant, which suggests that the mutant germ cells either fail to switch from mitotic to meiotic fate or dedifferentiate after entering into meiosis but prior to the stage requiring SPE-6 activity.

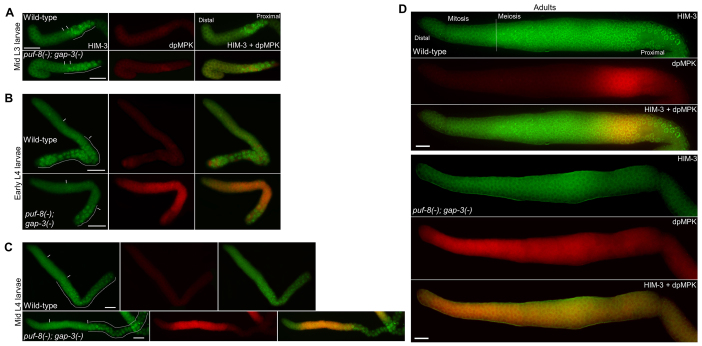

Known mutations that cause meiotic exit and dedifferentiation do not alter the temporal and spatial positions of meiotic onset during larval development (Francis et al., 1995a; Francis et al., 1995b; Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003). Therefore, we wanted to check whether the meiotic onset was normal in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant. To do this, we immunostained the gonads at different developmental time points with antibodies against the meiotic marker HIM-3 (Zetka et al., 1999). In addition, we co-immunostained the same gonads with the anti-dpMPK-1 antibodies to identify the exact time and location of dpMPK-1 activation. In the wild-type C. elegans, meiosis begins at early L3 larval stage in the proximal part of the gonad (Hansen et al., 2004a). At the mid-L3 stage, HIM-3-positive cells were present at the proximal part of the wild type as well as the double mutant gonads (Fig. 5A). These results indicate that inhibition of LET-60 activity by puf-8 and gap-3 is not required for the initiation of entry into meiosis at the normal time during development. At this stage, no dpMPK-1 could be detected in the wild-type or the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant. By contrast, at the early L4 stage, dpMPK-1 expression was readily observable in the double mutant in all germ cells with the exception of a few at the distal end and most of the HIM-3-positive cells at the proximal end (Fig. 5B). Similar expression patterns also persisted at the mid-L4 stage (Fig. 5C). At both these later stages, although the zones of dpMPK-1 and HIM-3 expression were mutually exclusive for the large part, they overlapped in a few cells at the boundary between the two zones (Fig. 5B,C). However, whereas elevated levels of dpMPK-1 were observed throughout the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) adult germlines, no HIM-3-positive cells were detected in them (Fig. 5D). These results reveal that the activation of MPK-1 in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) germline begins in cells at the proximal part of the distal proliferative zone, referred to as meiotic entry region or the transit-amplifying zone (Cinquin et al., 2010; Hansen et al., 2004a), and that these cells, once the level of dpMPK-1 increases beyond a threshold, fail to differentiate into HIM-3-positive meiotic cells. This is consistent with the earlier observation that the downstream effectors of the RAS/MAPK pathway promote the mitotic fate (Lee et al., 2007b).

Fig. 5.

Time-course analysis of MPK-1 activation and the onset of meiosis. (A-D) Gonads were extruded by dissecting worms at the indicated developmental stages and immunostained for the synaptonemal complex protein HIM-3 (green), which marks the meiotic cells, and dpMPK-1 (red), which is the active form of the MAP kinase MPK-1. In A-C, the broken lines indicate the area containing germ cells with HIM-3-positive chromatin. Vertical lines mark the approximate boundaries of the meiotic entry region. In D, the broken vertical line marks the boundary between the HIM-3-negative and HIM-3-positive cells in the wild type; no HIM-3-positive cells are seen in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) gonad. Synchronous L1 larvae were fed on OP50 bacterial lawns for 36 hours (mid L3), 42 hours (early L4), 48 hours (mid L4) and 66 hours (adults) at 20°C before immunostaining. Scale bars: 20 μm.

Another hallmark of the germ cell tumour resulting from dedifferentiation is that it is dependent on the germ cell sex (Francis et al., 1995a; Francis et al., 1995b; Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003). Contradictory to this, puf-8(-); gap-3(-) males, as well as puf-8(-); gap-3(-); fem-3(-) and puf-8(-); gap-3(-) fog-3(-) feminized hermaphrodites, displayed germline tumour phenotype (supplementary material Fig. S3). Taken together, the data presented in this section indicate that the overproliferation phenotype of puf-8(-); gap-3(-) results from the failure to maintain the proliferative to the meiotic fate switch in the adult germline.

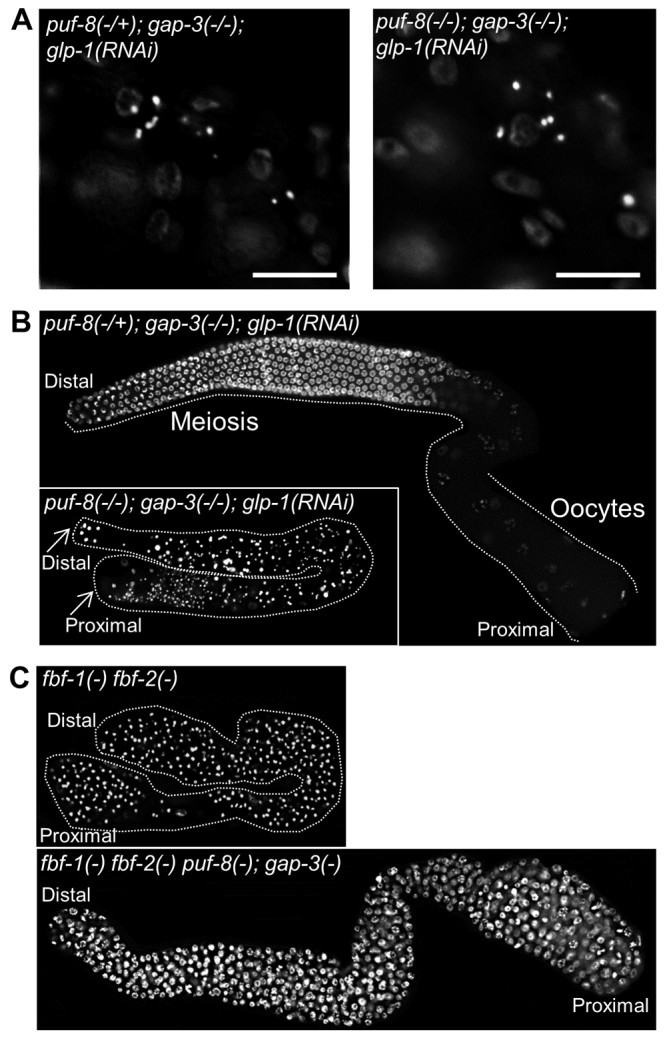

Germline tumour formation in puf-8(-); gap-3(-) depends on glp-1, but not on fbf, activity

GLP-1 signalling is essential for the mitotic fate of GSCs. In glp-1(-) worms, very few germ cells are made, and all these cells differentiate into sperm (Austin and Kimble, 1987). GLP-1 prevents premature entry into meiosis in part by promoting the expression of the PUF protein FBF, which suppresses the expression of the meiotic promoter GLD-1 (Crittenden et al., 2002). In addition, GLP-1 has been proposed to promote the expression of an unknown gene named gene X, which suppresses GLD-1 expression (Hansen et al., 2004b). To determine whether the overproliferation phenotype of puf-8(-); gap-3(-) germlines is dependent on glp-1 and/or fbf, we performed epistasis analysis among these genes using loss-of-function alleles as well as RNAi. Germ cell proliferation in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-); glp-1(RNAi) worms was reduced to the level observed in glp-1(-) single mutant worms, and the few cells present in the triple mutant differentiated into sperm (Fig. 6A). Similar results were obtained even when GLP-1 was depleted after ectopic MPK-1 activation (Fig. 6B). These results show that the tumorous proliferation observed in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) germline is dependent on GLP-1, and suggest that puf-8 and gap-3 function either as upstream negative regulators of glp-1, or in a parallel pathway. In addition, these results reveal PUF-8 and GAP-3 are not essential for meiosis when the block of meiotic entry by GLP-1 is removed. The PUF protein FBF is encoded by two nearly identical paralogues fbf-1 and fbf-2 (Zhang et al., 1997). Therefore, we generated the fbf-1(-) fbf-2(-) puf-8(-); gap-3(-) quadruple mutants to test whether the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) tumour phenotype required FBF. Surprisingly, as shown in Fig. 6C, germ cells in this quadruple mutant proliferated in an uncontrolled fashion, just as they did in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant worms, indicating that FBF is not required for the tumorous proliferation of the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) germ cells. Possibly, the ectopically activated MPK-1 blocks meiotic entry by promoting the expression and/or activity of gene X mentioned above, which is independent of FBF. Alternatively, the ectopic MPK-1 promotes proliferation directly; however, only when the block of meiotic entry is maintained either by FBF or gene X.

Fig. 6.

puf-8(-); gap-3(-) tumour phenotype is dependent on GLP-1, but not on FBF. (A) DAPI-stained worms of the indicated genotypes are shown. Only a part of the worm where the germline is present is seen here. Only a few sperm (bright white spots) are present in the germline. Fainter staining in the background is of somatic nuclei. (B,C) Dissected, DAPI-stained gonads of adult worms. GLP-1 was depleted either during early larval development, by allowing embryos to hatch and develop on glp-1 RNAi bacteria (A), or during L4 larval stage, by shifting larvae at late L3 to RNAi bacteria (B). In B, puf-8(-/+) heterozygous germ cells have entered oogenesis, whereas the puf-8(-/-) homozygotes (bottom) have differentiated as sperm, presumably owing to the lack of puf-8 and glp-1(-). In C, whereas fbf-1(-) fbf-2(-) gonads have only sperm, the fbf-1(-) fbf-2(-) puf-8(-); gap-3(-) gonads have only mitotic germ cells.

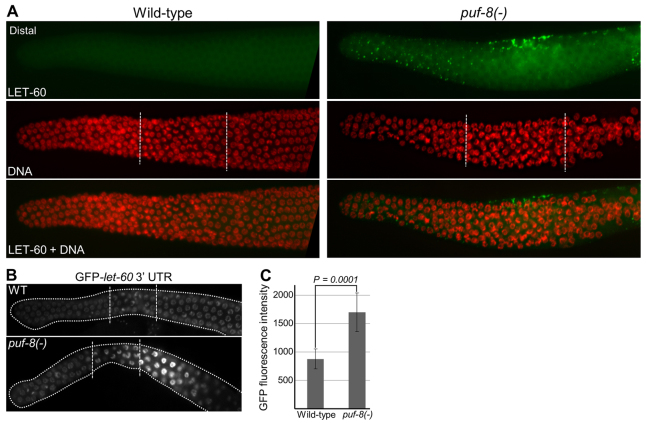

PUF-8 suppresses LET-60 expression in the proliferative and transition zones by direct 3′ UTR binding

Next, we wanted to investigate how PUF-8 and GAP-3 synergistically control the activation of MPK-1. As mentioned above, GAP-3 is a RasGAP; it negatively regulates the LET-60 RAS to promote pachytene exit (Stetak et al., 2008). As PUF-8 is a post-transcriptional regulator, we tested whether PUF-8 controlled the expression of LET-60. First, we checked the levels of LET-60 protein in the germlines by immunostaining. In the wild-type hermaphrodite germline, no LET-60 signal could be detected in the proliferative, transition and in the distal part of the pachytene regions (Fig. 7). In the distal-proximal sense, LET-60 first appeared on punctate structures around the mid-pachytene region and became stronger where pachytene nuclei begin to cellularize and form oocytes. The levels of LET-60 dramatically increased in the maturing oocytes (supplementary material Figs S4, S5). By contrast, punctate-like LET-60 signals were readily observed in the distal proliferative zone in the puf-8(-) germlines; its expression was more pronounced in the transition zone, where the punctate structures appeared to be localized on the cell membrane (Fig. 7). These results show that PUF-8 suppresses the expression of LET-60 in the proliferative and transition zones.

Fig. 7.

PUF-8 negatively regulates LET-60 expression in the germline. (A) Dissected gonads stained with anti-LET-60 antibodies and DAPI. Genotypes are indicated on the top. In the transition zone, although LET-60 signal is seen only in a few cells at the top in this focal plane, it was observed in a several cells within this zone in other focal planes. The dots revealed by immunostaining signal correspond to cell membrane at the intersection of adjacent cells. See also supplementary material Figs S5 and S6. (B) Dissected gonads of live worms revealing the expression pattern of GFP::H2B reporter fusion expressed under the control of pie-1 promoter and let-60 3′ UTR sequences. Only the distal germlines are shown. In the puf-8(-) genetic background, let-60 3′ UTR fusion shows significant upregulation in the transition and early pachytene region when compared with the wild type. In total, 20 worms each of 11 independent transgenic lines were examined, and representative images are shown here. broken lines in A and B mark the boundaries among the mitotic, transition and pachytene regions. (C) Comparison of the GFP fluorescence intensity (arbitrary units) per nucleus in the transition zone between the wild-type and puf-8(-) gonads. n=23 nuclei from five gonads; P=0.0001 (Student’s t-test).

PUF-8 has been shown to regulate its target mRNAs by binding to the 3′ UTR (Mainpal et al., 2011). Therefore, we tested whether PUF-8 can control let-60 3′ UTR-mediated expression in the germline. For this, we generated GFP::H2B-let-60 3′ UTR fusion transgene and expressed it in the germline using pie-1 promoter (D’Agostino et al., 2006). In the wild-type genetic background, the let-60 3′ UTR fusion expressed GFP::H2B weakly in the proliferative as well as transition zones. By contrast, depletion of PUF-8 enhanced the expression of GFP::H2B in the crescent-shaped nuclei of the transition zone, which further increased in the early pachytene cells (Fig. 7). These results suggest PUF-8 negatively regulates let-60 mRNA in the transition zone and early pachytene germ cells. The slight proximal shift between the LET-60 misexpression detected by immunostaining and the GFP::H2B-let-60 3′ UTR expression in the puf-8(-) germline is probably due to the delay in the accumulation of sufficient levels of GFP::H2B.

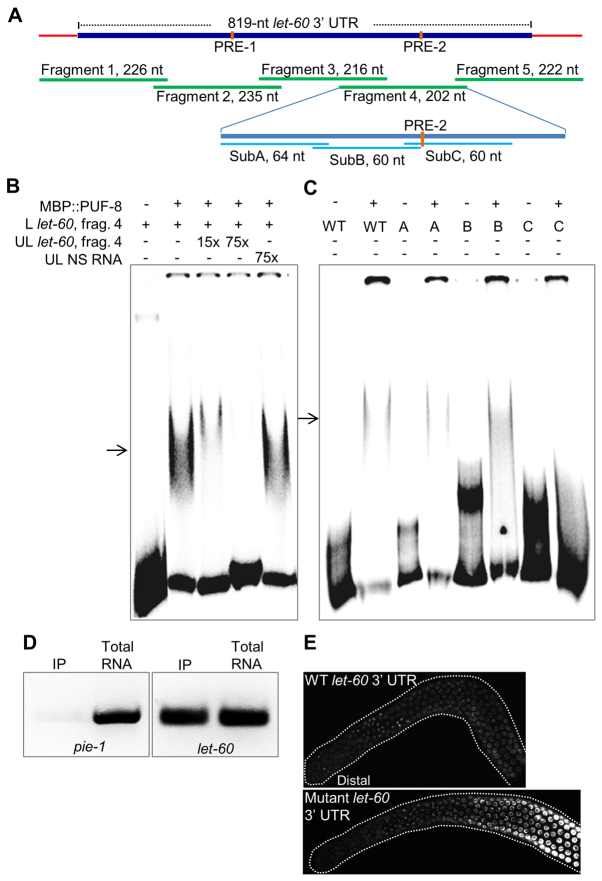

To determine whether PUF-8 mediated its effect on let-60 3′ UTR through direct RNA binding, we first tested its ability to interact with the let-60 3′ UTR in electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA). Earlier, a fusion protein containing the PUF domain (171-535 amino acids) of PUF-8 and the maltose-binding protein (MBP::PUF-8) has been used to demonstrate the interaction between PUF-8 and the 3′ UTR of one of its targets, pal-1 mRNA (Mainpal et al., 2011). Therefore, we used the same fusion protein in EMSAs with the let-60 3′ UTR RNA. As the let-60 3′ UTR is too long - 819 nucleotides - to be tested in EMSA, we divided it into five fragments and tested each of them individually. Of these five, MBP::PUF-8 retarded the mobility of fragment 4 in a sequence-specific manner (Fig. 8B and data not shown). We then substituted 60-nucleotide stretches of this 202-nucleotide fragment 4 with TG repeats to identify the specific sequence of RNA that is crucial for PUF-8 binding. As shown in Fig. 8C, substitution of SubC region completely abolished the mobility shift, indicating that this region is crucial for binding PUF-8.

Fig. 8.

PUF-8 interacts with let-60 3′ UTR. (A) Parts of let-60 3′UTR RNA tested in gel shift assays presented in B and C. Sequences of PRE-1 (UGUCAAAA) and PRE-2 (UGUCAAGU) match to the consensus PUF-8 recognition element (Opperman et al., 2005). SubA, SubB and SubC refer to regions substituted with TG repeats. (B) Electrophoretic mobility patterns of radiolabelled fragment 4 of let-60 3′ UTR RNA (L let-60, fragment 4) in the presence of indicated components. MBP::PUF-8, bacterially expressed fusion protein containing maltose-binding protein and the C-terminal (175-535 amino acids) PUF domain of PUF-8; UL, non-radiolabelled; NS, a non-specific RNA of about 200 nucleotides; 15× and 75×, 15 and 75 times molar excess when compared with the radiolabelled RNA, respectively. Arrow indicates the mobility-shifted band in both B and C. (C) Same assay as described in B except that the sequence of the radiolabelled RNA was substituted as indicated. Substitutions of the SubA, SubB and SubC regions are indicated as A, B and C, respectively. WT, no substitution. (D) Results of co-immunoprecipitation assay. PUF-8::9×HA::GFP fusion protein from transgenic worms was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies and the co-immunoprecipitation of the indicated RNAs was detected using RT-PCR. To determine the specificity of co-immunoprecipitation, pie-1 mRNA was amplified as a negative control and the levels of both pie-1 and let-60 RT-PCR products from the immunoprecipitated pellet (IP) were compared with the total RNA. (E) Dissected gonads of live worms revealing the expression pattern of GFP::H2B reporter fusion expressed under the control of pie-1 promoter and let-60 3′ UTR sequences; the bottom panel shows the expression pattern of the let-60 3′ UTR bearing SubC substitution. Images are representative of 20 worms from each of eight independent transgenic lines. The effect of cis mutation (SubC substitution) is not identical to that of the trans mutation (removal of PUF-8) presented in Fig. 7B, owing to other germline defects of puf-8(-) at 25°C (Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003).

Second, we investigated the importance of PUF-8-let-60 3′ UTR interaction in vivo using the GFP::H2B-let-60 3′ UTR transgene assay described above. Transgenic worms with the wild-type let-60 3′ UTR sequence showed a weak, uniform expression throughout the gonad (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8E). By contrast, the GFP::H2B expression was markedly elevated starting from the transition zone in worms carrying the transgene with SubC substitution (Fig. 8E). Thus, removal of PUF-8 or mutation of let-60 3′ UTR both affect let-60 3′ UTR-mediated expression in the germ cells of the transition zone. Third, we further validated the PUF-8-let-60 3′ UTR interaction using the co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) approach. There are no PUF-8-specific antibodies currently available; as the expression of PUF-8::GFP is very weak, anti-GFP antibodies have also not been successful, at least in our hands, for immunoprecipitation from worm extracts. Therefore, we generated a new transgene bearing nine repeats of the HA epitope tag fused to PUF-8::GFP. This transgene rescued puf-8(-) worms, indicating that the fusion protein is functional (data not shown). Western blotting revealed that the anti-HA antibodies could specifically immunoprecipitate the 9×HA::PUF-8::GFP from worm lysates (data not shown). Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on RNA templates extracted from the immunoprecipitated pellets using let-60-specific PCR primers showed that the let-60 mRNA specifically co-immunoprecipitated with the fusion protein (Fig. 8D). We conclude PUF-8 suppresses let-60 expression in the transition zone germ cells by binding to the let-60 3′ UTR.

DISCUSSION

Results presented here identify the PUF protein PUF-8 as a crucial upstream regulator of the MPK-1 MAP kinase and explain why MPK-1 is not activated during the early pachytene stage, although MPK-1 activity is crucial for the meiotic progression (Church et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2007b; Ohmachi et al., 2002). Our results clearly show that the premature MPK-1 activation promotes mitotic fate, and as a result, germ cells fail to enter meiosis. Importantly, our findings reveal that the post-transcriptional control of let-60 mRNA by PUF-8 and the protein-level of control of LET-60 RAS activity by the RasGAP GAP-3 constitute a redundant mechanism to maintain the MPK-1 activity at undetectable levels in the mitotic, meiotic-entry and the early pachytene regions. In C. elegans, the somatic distal tip cell regulates the mitosis-meiosis switch by spatially restricting GLP-1 signalling, which prevents premature meiotic entry (Kimble and Crittenden, 2007). In this context, the ectopic activation of a proliferation-promoting signal that is not spatially regulated will potentially interfere with the mitosis-meiosis transition. Results presented here show that PUF-8 and GAP-3 function redundantly to prevent one such proliferation-promoting signal - the ectopic activation of LET-60 RAS - from disrupting the regulation of the mitosis-meiosis switch mediated by the spatially restricted GLP-1 signalling.

Origin of the tumour-forming cells in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) mutant

At 25°C, puf-8(-) single mutant primary spermatocytes exit meiosis, dedifferentiate and form a tumour (Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003). Several observations indicate that the tumour phenotype of puf-8(-); gap-3(-) differs from this dedifferentiation-driven tumour of puf-8(-). First, although meiotic block caused by the removal of SPE-6 arrests the puf-8(-) tumour, it does not do so in the case of the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) tumour. Second, although the onset of meiosis occurs normally in the double mutant, cells positive for the meiotic marker HIM-3 are absent at the adult stage. By contrast, HIM-3-positive cells are continuously present in the puf-8(-) mutant. Third, the double mutant tumour is not dependent on the germ cell sex, whereas the puf-8(-) tumour is dependent on the male germ cell sex (Subramaniam and Seydoux, 2003). Fourth, upon depletion of GLP-1 at the L4 larval stage - a stage when the removal of PUF-8 and GAP-3 results in elevated levels of active MPK-1 - the double mutant germ cells are able to differentiate and form sperm, which is unlikely if the uncontrolled proliferation is due to dedifferentiation. These observations strongly support that the tumorous proliferation in the puf-8(-); gap-3(-) double mutant is caused by the failure to switch from proliferative to meiotic fate, rather than by the dedifferentiation of cells that have already entered into meiosis.

MAPK pathway and meiotic entry

Signal transduction through the RAS/MAPK pathway promotes cell proliferation in diverse organisms. Increased signalling through this pathway is responsible for tumour growth in a variety of cancers. However, its role in the mitotic self-renewal of germ cells is poorly understood. In C. elegans germline, RAS/MAPK signalling is essential for meiotic progression, oocyte maturation and ovulation, all of which underscore the crucial role that this signalling pathway plays in the various cellular events involved in differentiation (Arur et al., 2011; Church et al., 1995; Lee et al., 2007b; Ohmachi et al., 2002). Despite its essential role in meiotic progression, we do not think RAS/MAPK pathway promotes the early events of meiotic entry for the following reasons. First, even in null mpk-1 mutants, germ cells enter meiosis and arrest in pachytene (Church et al., 1995; Ohmachi et al., 2002). Rather, as mentioned in the Introduction, RAS/MAPK signalling promotes the proliferative fate (Lee et al., 2007b). Second, MPK-1 is not activated in germ cells just entering meiosis, and the downstream effectors of the RAS/MAPK pathway promote mitotic fate (Lee et al., 2007b). Third, our results show that, rather than promoting differentiation, an increase in the levels of dpMPK-1 in these cells actually promotes continued proliferation. Fourth, our epistasis analysis reveal that the tumour phenotype of puf-8(-) gap-3(-) is epistatic over fbf-1(-) fbf-2(-), clearly indicating that, instead of enhancing the premature meiotic-entry phenotype of fbf-1(-) fbf-2(-) (Crittenden et al., 2002), the elevated levels of active MPK-1 overcome the meiosis-promoting signals that are inappropriately activated in the absence of the FBFs and still supports proliferation.

Control of RAS/MAPK signalling by PUF proteins

PUF-8 is not the first PUF protein to be discovered as a regulator of the RAS/MAPK pathway. The FBF proteins have been shown to control the activity of MAPK phosphatase orthologue LIP-1, as well as MPK-1 itself, in sensitized backgrounds (Lee et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2007a). The net outcome of such a mutually opposite regulation, in terms of the levels of dpMPK-1 in the fbf-1(-) fbf-2(-) germ cells, is not known. Because of its negative effect on LIP-1 expression, FBF probably helps the maintenance of a basal level of MPK-1 activity in the distal mitotic zone. Existence of a basal level of RAS/MAPK signalling in the mitotic zone is consistent with the earlier observation that MPK-1 is essential for proliferation in a sensitized genetic background (Lee et al., 2007b). We propose PUF-8 diminishes this basal activity in the meiotic entry region and the transition zone to enable germ cells in this zone to exit the proliferative fate and enter meiosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the C. elegans Genetics Center for many strains used in this study.

Footnotes

Funding

We thank the Wellcome Trust and the Indian Council of Agricultural Research for financial support; the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, Government of India for a SRF to A.C.; and the Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur for graduate student scholarships to S.V. and G.A.K. Deposited in PMC for immediate release.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.088013/-/DC1

References

- Ahringer J., Kimble J. (1991). Control of the sperm-oocyte switch in Caenorhabditis elegans hermaphrodites by the fem-3 3’ untranslated region. Nature 349, 346–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariz M., Mainpal R., Subramaniam K. (2009). C. elegans RNA-binding proteins PUF-8 and MEX-3 function redundantly to promote germline stem cell mitosis. Dev. Biol. 326, 295–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arur S., Ohmachi M., Berkseth M., Nayak S., Hansen D., Zarkower D., Schedl T. (2011). MPK-1 ERK controls membrane organization in C. elegans oogenesis via a sex-determination module. Dev. Cell 20, 677–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin J., Kimble J. (1987). glp-1 is required in the germ line for regulation of the decision between mitosis and meiosis in C. elegans. Cell 51, 589–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachorik J. L., Kimble J. (2005). Redundant control of the Caenorhabditis elegans sperm/oocyte switch by PUF-8 and FBF-1, two distinct PUF RNA-binding proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 10893–10897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernards A. (2003). GAPs galore! A survey of putative Ras superfamily GTPase activating proteins in man and Drosophila. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1603, 47–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry L. W., Westlund B., Schedl T. (1997). Germ-line tumor formation caused by activation of glp-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans member of the Notch family of receptors. Development 124, 925–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S. (1974). The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 77, 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen P. J., Singal A., Kimble J., Ellis R. E. (2000). A novel member of the tob family of proteins controls sexual fate in Caenorhabditis elegans germ cells. Dev. Biol. 217, 77–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church D. L., Guan K. L., Lambie E. J. (1995). Three genes of the MAP kinase cascade, mek-2, mpk-1/sur-1 and let-60 ras, are required for meiotic cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 121, 2525–2535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinquin O., Crittenden S. L., Morgan D. E., Kimble J. (2010). Progression from a stem cell-like state to early differentiation in the C. elegans germ line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 2048–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden S. L., Bernstein D. S., Bachorik J. L., Thompson B. E., Gallegos M., Petcherski A. G., Moulder G., Barstead R., Wickens M., Kimble J. (2002). A conserved RNA-binding protein controls germline stem cells in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 417, 660–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino I., Merritt C., Chen P. L., Seydoux G., Subramaniam K. (2006). Translational repression restricts expression of the C. elegans Nanos homolog NOS-2 to the embryonic germline. Dev. Biol. 292, 244–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., Barton M. K., Kimble J., Schedl T. (1995a). gld-1, a tumor suppressor gene required for oocyte development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 139, 579–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis R., Maine E., Schedl T. (1995b). Analysis of the multiple roles of gld-1 in germline development: interactions with the sex determination cascade and the glp-1 signaling pathway. Genetics 139, 607–630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D., Hubbard E. J., Schedl T. (2004a). Multi-pathway control of the proliferation versus meiotic development decision in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. Dev. Biol. 268, 342–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen D., Wilson-Berry L., Dang T., Schedl T. (2004b). Control of the proliferation versus meiotic development decision in the C. elegans germline through regulation of GLD-1 protein accumulation. Development 131, 93–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav S., Rana M., Subramaniam K. (2008). Multiple maternal proteins coordinate to restrict the translation of C. elegans nanos-2 to primordial germ cells. Development 135, 1803–1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadyk L. C., Kimble J. (1998). Genetic regulation of entry into meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 125, 1803–1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble J. (2011). Molecular regulation of the mitosis/meiosis decision in multicellular organisms. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 3, a002683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble J., Crittenden S. L. (2007). Controls of germline stem cells, entry into meiosis, and the sperm/oocyte decision in Caenorhabditis elegans. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 405–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont L. B., Crittenden S. L., Bernstein D., Wickens M., Kimble J. (2004). FBF-1 and FBF-2 regulate the size of the mitotic region in the C. elegans germline. Dev. Cell 7, 697–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. H., Hook B., Lamont L. B., Wickens M., Kimble J. (2006). LIP-1 phosphatase controls the extent of germline proliferation in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO J. 25, 88–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. H., Hook B., Pan G., Kershner A. M., Merritt C., Seydoux G., Thomson J. A., Wickens M., Kimble J. (2007a). Conserved regulation of MAP kinase expression by PUF RNA-binding proteins. PLoS Genet. 3, e233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. H., Ohmachi M., Arur S., Nayak S., Francis R., Church D., Lambie E., Schedl T. (2007b). Multiple functions and dynamic activation of MPK-1 extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans germline development. Genetics 177, 2039–2062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann R. (2012). Germline stem cells: origin and destiny. Cell Stem Cell 10, 729–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainpal R., Priti A., Subramaniam K. (2011). PUF-8 suppresses the somatic transcription factor PAL-1 expression in C. elegans germline stem cells. Dev. Biol. 360, 195–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malumbres M., Barbacid M. (2003). RAS oncogenes: the first 30 years. Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C. T., Lee M. H., Kimble J. (2010). Chemical reprogramming of Caenorhabditis elegans germ cell fate. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 102–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohmachi M., Rocheleau C. E., Church D., Lambie E., Schedl T., Sundaram M. V. (2002). C. elegans ksr-1 and ksr-2 have both unique and redundant functions and are required for MPK-1 ERK phosphorylation. Curr. Biol. 12, 427–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opperman L., Hook B., DeFino M., Bernstein D. S., Wickens M. (2005). A single spacer nucleotide determines the specificities of two mRNA regulatory proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 945–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praitis V., Casey E., Collar D., Austin J. (2001). Creation of low-copy integrated transgenic lines in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 157, 1217–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racher H., Hansen D. (2012). PUF-8, a Pumilio homolog, inhibits the proliferative fate in the Caenorhabditis elegans germline. G3 (Bethesda) 2, 1197–1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X., Wong M. D., Kawase E., Xi R., Ding B. C., McCarthy J. J., Xie T. (2004). Bmp signals from niche cells directly repress transcription of a differentiation-promoting gene, bag of marbles, in germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development 131, 1353–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stetak A., Gutierrez P., Hajnal A. (2008). Tissue-specific functions of the Caenorhabditis elegans p120 Ras GTPase activating protein GAP-3. Dev. Biol. 323, 166–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S., Powers J., Dunn M., Reese K., Malone C. J., White J., Seydoux G., Saxton W. (2001). Spindle dynamics and the role of gamma-tubulin in early Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1751–1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam K., Seydoux G. (2003). Dedifferentiation of primary spermatocytes into germ cell tumors in C. elegans lacking the pumilio-like protein PUF-8. Curr. Biol. 13, 134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaram M. V. (2006). RTK/Ras/MAPK signaling. WormBook 11, 1–19 18050474 [Google Scholar]

- Timmons L., Court D. L., Fire A. (2001). Ingestion of bacterially expressed dsRNAs can produce specific and potent genetic interference in Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene 263, 103–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varkey J. P., Jansma P. L., Minniti A. N., Ward S. (1993). The Caenorhabditis elegans spe-6 gene is required for major sperm protein assembly and shows second site non-complementation with an unlinked deficiency. Genetics 133, 79–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T., Spradling A. C. (1998). decapentaplegic is essential for the maintenance and division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Cell 94, 251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetka M. C., Kawasaki I., Strome S., Müller F. (1999). Synapsis and chiasma formation in Caenorhabditis elegans require HIM-3, a meiotic chromosome core component that functions in chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 13, 2258–2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B., Gallegos M., Puoti A., Durkin E., Fields S., Kimble J., Wickens M. P. (1997). A conserved RNA-binding protein that regulates sexual fates in the C. elegans hermaphrodite germ line. Nature 390, 477–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.