Abstract

Although ectopic lymphoid tissue formation is associated with many autoimmune diseases, it is unclear whether it serves a functional role in autoimmune responses. Tetramethylpentadecane (TMPD) causes chronic peritoneal inflammation and lupus-like disease with autoantibody production and ectopic lymphoid tissue (lipogranuloma) formation. A novel transplantation model was used to show that transplanted lipogranulomas retain their lymphoid structure over a prolonged period in the absence of chronic peritoneal inflammation. Recipients of transplanted lipogranulomas produced anti-U1A autoantibodies derived exclusively from the donor, despite nearly complete repopulation of the transplanted lipogranulomas by host lymphocytes. The presence of ectopic lymphoid tissue alone was insufficient, as an anti-U1A response was not generated by the host in the absence of ongoing peritoneal inflammation. Donor-derived anti-U1A autoantibodies were produced for up to two months by plasma cells/plasmablasts recruited to the ectopic lymphoid tissue by CXCR4. Although CD4+ T cells were not required for autoantibody production from the transplanted lipogranulomas, de novo generation of anti-U1A plasma cells/plasmablasts was reduced following T cell depletion. Significantly, a population of memory B cells was identified in the bone marrow and spleen that did not produce anti-U1A autoantibodies unless stimulated by LPS to undergo terminal differentiation. We conclude that TMPD promotes the T cell-dependent development of class-switched, autoreactive memory B cells and plasma cells/plasmablasts. The latter home to ectopic lymphoid tissue and continue to produce autoantibodies after transplantation and in the absence of peritoneal inflammation. However, peritoneal inflammation appears necessary to generate autoreactive B cells de novo.

Introduction

Lymphoid neogenesis, the formation of ectopic (tertiary) lymphoid tissue in response to chronic inflammation (1), is associated with autoantibody production in Sjogren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, myasthenia gravis, and other diseases (2–4). Although many features of secondary lymphoid tissue development are recapitulated (5), it is unclear whether ectopic lymphoid tissue participates directly in generating autoreactive B cells, indirectly as a reservoir for antibody-secreting cells, or both.

Approximately 3 months after intraperitoneal exposure of non-lupus prone mice to the hydrocarbon oil 2, 6, 10, 14 tetramethylpentadecane (TMPD, pristane), “lipogranulomas” (ectopic lymphoid tissue) form and the mice develop high levels of IgG lupus-associated autoantibodies (e.g. anti-Sm/RNP and DNA) and nephritis (6, 7). The production of these class-switched autoantibodies requires T cells (8). In contrast, mice treated i.p. with mineral oil (a mixture of hydrocarbons) develop ectopic lymphoid tissue but not lupus. The inflammatory response to TMPD (but not mineral oil) is maintained chronically by a vicious cycle of type I interferon (IFN-I) production stimulating the expression of CCL2 and other IFN-I inducible chemokines, which recruit additional IFN-I producing cells into the lipogranulomas (9). T and B lymphocytes and dendritic cells are recruited to the inflamed peritoneum by the chemokines CCL19, CCL21, and CXCL13, and the ectopic lymphoid tissue develops distinct T cell/dendritic cell and B cell zones (10). B cells in the ectopic lymphoid tissue exhibit some features of the germinal center response, including proliferation, class switch recombination, and expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (8). After primary immunization with the exogenous antigen NP-KLH, antigen-specific B and T lymphocytes home to TMPD-induced ectopic lymphoid tissue and proliferate. In addition, class-switched, NP-specific immunoglobulin is produced by cells residing in the lipogranulomas (11). Similarly, IgG anti-RNP (U1A) autoantibody-secreting cells are highly enriched in TMPD-induced ectopic lymphoid tissue compared to spleen (8). However, the origin of these cells and their relationship to the persistent anti-U1A autoantibody levels in the serum are unknown.

Long-term serological memory can be maintained by long-lived plasma cells, normally found in the bone marrow (BM), which may continue to secrete antibodies for many years (12). Alternatively, serological memory may be maintained by T cell-dependent activation and differentiation of memory B cells into antibody-producing plasmablasts (PB) and plasma cells (PC) (13–15) and possibly by toll-like receptor (TLR) mediated polyclonal activation of memory B cells (16, 17). The objective of this study was to develop a model to examine how autoantibody responses to the Sm/RNP autoantigen (anti-U1A autoantibodies) are maintained and to define the role of chronic inflammation and ectopic lymphoid tissue in autoantibody production. We found that ongoing peritoneal inflammation was required to generate new anti-U1A B cells. PC/PB producing anti-U1A autoantibodies accumulated in the ectopic lymphoid tissue induced by TMPD, but the lipogranulomas were nearly devoid of anti-U1A memory B cells. Transplantation of lipogranulomas into the non-inflamed peritoneum of another mouse did not abolish autoantibody production, but anti-U1A autoantibodies were exclusively of donor origin. Unexpectedly, the bone marrow of mice treated 3–4 months earlier with TMPD proved to be a major reservoir of anti-U1A memory B cells but contained very few anti-U1A PC/PB.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Six-week-old female C57BL/6, BALB/c/J, CB.17, and T cell transgenic C.Cg-Tg (DO11.10)10Dlo/J (DO11.10) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in barrier cages. At 2 months of age, C57BL/6, BALB/c/J, CB.17, and DO11.10 mice received 0.5 ml i.p. of TMPD (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or mineral oil (Harris Teeter, Matthews, NC) or left untreated. Three months later, lipogranulomas were harvested for transplantation. These studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Lipogranuloma transplantation

For transplantation, TMPD-induced lipogranulomas were harvested from mice producing anti-U1A antibodies (confirmed by ELISA). Recipient mice underwent an upper midline laparotomy beginning at the mid-abdomen and terminating superiorly at the xiphoid process. The harvested donor lipogranulomas were then transplanted onto the lateral aspect of the peritoneal surface of the right and left costo-diaphramatic junctions using a 6-0 polypropylene monofilament suture. The midline laparotomy was re-approximated with interrupted subcutaneous monofilament sutures and the overlying skin secured with surgical wound clips. Mice received 1 ml of physiological saline for resuscitation at transplant completion. When indicated, mice also received lipogranuloma tissue subcutaneously or intraperitoneally without any suture to hold it in place. Sham procedures were carried out with a midline laparotomy and placement of a 6-0 polypropylene monofilament suture on the lateral aspect of the peritoneal surface of the right and left costo-diaphramatic junctions. Sham-transplanted mice also received normal saline at the termination of the procedure.

Flow cytometry

Cell suspensions from transplanted lipogranulomas or recipient spleens were analyzed using annexin V plus 7AAD staining (Apoptotic Cell Kit, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). T cells were analyzed with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, anti-B220, anti-CD11b, anti-CD25, anti-IgMa, and anti-IgMb antibodies (BD Biosciences), and anti-Foxp3 antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). DO11.10 T cells were identified using anti-DO11.10 (KJ1-26)-APC antibodies (Invitrogen, Caltag Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA). Data were acquired on a CyAn ADP flow cytometer (Dako, Fort Collins, Colorado) or an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FCS Express Version 3 (DeNovo Software, Thornhill, Ontario, Canada). At least 50,000 events per sample were acquired and analyzed using size gating and Sytox blue (Invitrogen) to exclude dead cells.

Anti-U1A (RNP) ELISA

The ELISA was carried out as described previously, using 6-His tagged recombinant U1A protein expressed in E. coli (5 μg/ml) as antigen (8). Serum samples were tested at a 1:250 dilution followed by incubation with alkaline phosphatase-labeledgoat anti-mouse IgG (1:1000 dilution) or biotinylated anti-IgG2aa, IgG2ab (= IgG2c), IgMa, or IgMb (BD Biosciences, 1 hr at 22°C), a 45 minute incubation with neutralite-avidin (Southern Biotechnology, Birmingham, AL), and development with p-nitrophenylphosphate substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). Optical density at 405 nm (OD405) was read using a VERSAmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA).

Detection of autoantibodies by immunoprecipitation

The presence of anti-Sm/RNP autoantibodies was confirmed by immunoprecipitation of [35S]-labeled cellular proteins and analyzed on a 12.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel as described (6).

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was precipitated with isopropanol and the pellet washed with cold 75% (v/v) ethanol and resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water. One μg of RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using Superscript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen). One μl of cDNA was added to the PCR mixture containing PCR buffer, 2.5 mmol/L MgCl2, 400 μmol/L dNTPs, 0.025 U of TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen), and 1 μmol/L each of forward and reverse primers in a 20-μl volume. Primers were as follows: CXCL21 forward 5′-ATG ATG ACT CTG AGC CTC C-3′ and reverse 5′-GAG CCC TTT CCT TTC TTT CC-3′; CXCL13 forward 5′-ATG AGG CTC AGC ACA GCA AC-3′ and reverse 5′-CCA TTT GGC ACG AGG ATT CAC-3′; 18S forward 5′-CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT-3′. Reactions were heated for 5 min at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension of 72°C for 10 min in a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (Biorad, Hercules, CA ). PCR primers were synthesized by Invitrogen.

Quantitative PCR

Gene expression was quantified by real-time PCR. One μl of cDNA was added to a mixture containing 3.75 mmol/L MgCl2,1.25 mmol/L dNTP mixture, 0.025 U of Amplitaq Gold, SYBR Greendye (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and optimized concentrations of specific forward and reverse primers in a final volume of 20 μl. CXCL12 primers were as follows: forward 5′-TGC TCT CTG CTT GCC TCC A-3′ and reverse 5′-GGT CCG TCA GGC TAC AGA GGT-3′. The 18S cDNA primers were as above. Amplification conditions were 95°C (10 min), followed by 45 cycles of 94°C(15 sec), 60°C (25 sec), 72°C (25 sec), and a final extension at 72°C for 8 minutes using a DNA Engine Opticon 2 continuous fluorescence detector (MJ Research). Transcripts were quantified using the comparative (2ΔΔCt) method.

T cell depletion

CD4 T cells were depleted as described (17,18). Briefly, either anti-CD4 antibody (GK1.5 hybridoma 500 μg) or rat anti-human IL-4(IgG2b isotype control, Schering Plough Biopharma, Palo Alto, CA) was injected i.p. Donor mice received GK1.5 or rat anti-human IL-4 antibody four days prior to transplantation. Depletion lasted up to 7 days and was confirmed by flow cytometry. Recipients received GK1.5 or rat anti-human IL-4 antibody at the time of transplantation and weekly thereafter. After 35 days splenocytes, lipogranulomas, BM, and blood were harvested and depletion of CD4 T cells was confirmed by flow cytometry.

ELISPOT assay for anti-RNP autoantibody secreting cells

The production of anti-U1A (a subset of anti-RNP) autoantibodies in the ectopic lymphoid tissue was examined by ELISPOT assay as previously described (8).

Immunohistochemistry

Femurs were obtained from BALB/c mice treated 6 weeks earlier with TMPD and from untreated controls. The bones were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 1 h, rinsed in water for 10 min, then decalcified in Rapid Cal Immuno Decal Solution (BBC Biochemicals) for 3 hours, and rinsed again in water for 15 min. Specimens were embedded in paraffin and 4-μm paraffin sections were cut, placed on plus slides, and dried for 2 h at 60° C. The slides were then placed in a Ventana Benchmark automated immunostainer and deparaffinized. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed with Ventana’s CC1 retrieval solution for 30 min at 95–100°C. Pre-diluted peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse κ-light chain antibodies (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson AZ) were applied to the tissue for 8 min at 37° C. The presence of cells with intracellular light chain was visualized using the Ultra View DAB detection kit (Ventana). Slides were counterstained with Ventana Hematoxylin.

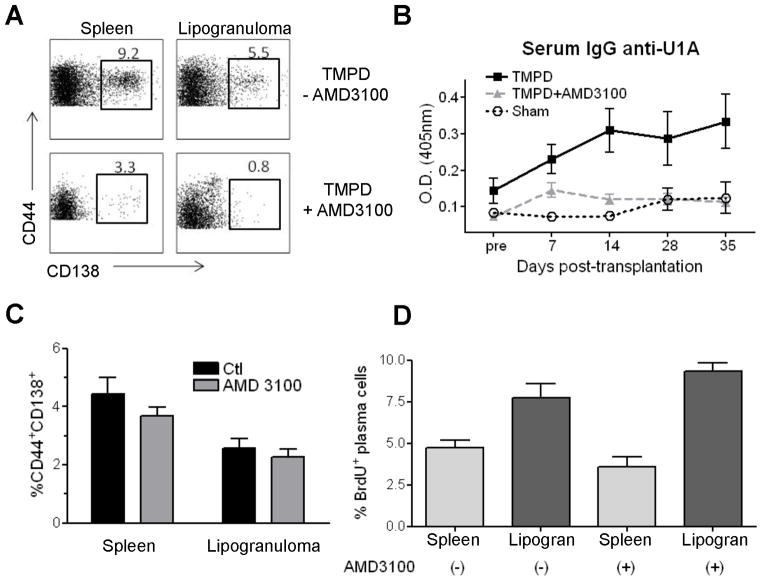

In vivo inhibition of CXCR4

CXCR4 inhibition was performed as previously described (18). Briefly, TMPD-treated anti-U1A+ mice received either 10 mg/kg i.p. of AMD3100 (Sigma Aldrich) in sterile PBS every 24 hours or PBS alone. Fifteen hours after the last AMD3100 treatment mice were sacrificed and lipogranulomas were excised and transplanted into untreated recipients as above. In some experiments, TMPD treated mice were injected daily with either AMD3100 or PBS for 3 d. The mice then received BrdU (0.2 mg in PBS i.p. twice daily for 2 days). Twelve hours after the final BrdU injection the mice were sacrificed and spleen and lipogranulomas were harvested. BrdU incorporation into IgM−CD138+ PC was detected by intracellular staining using an allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-BrdU antibody (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Results

Transplanted lipogranulomas become re-vascularized and are functional

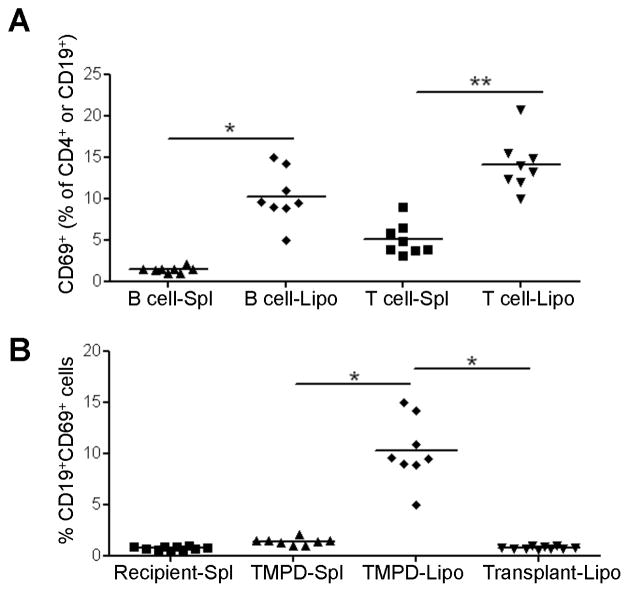

Antigen-specific B and T lymphocytes, including autoantibody-producing cells, home to TMPD-induced lipogranulomas (11). About 10–15% of the CD4+ T cells and CD19+ B cells residing in this ectopic lymphoid tissue exhibited an activated (CD69+) phenotype in contrast to the low percentage of activated lymphocytes in spleen cells from the same mice (Fig. 1A). Further characterization of the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the lipogranulomas revealed that the majority (80–90%) were CD44hiCD62Lneg memory cells (Fig. S1A). A high percentage of BM CD4+ T cells also exhibited a memory phenotype, as reported previously (19), whereas the phenotypes of splenic T cells were more diverse.

Figure 1. Effect of IFN-I on lymphocyte activation.

(A) Lipogranulomas (Lipo) and spleen (Spl) from TMPD-treated mice were harvested and the activated B cells (CD19+CD69+) and T cells (CD4+CD69+) as a % of total B or T cells were quantified by flow cytometry (* P = 0.01; ** P = 0.02, Mann-Whitney test). (B) Activated B cells (CD19+CD69+) from lipogranulomas pre- and post- transplant as well as spleen cells from TMPD-treated or recipient mice were analyzed by flow cytometry (* P = 0.01, Mann-Whitney test).

We next asked whether this ectopic lymphoid tissue can function outside the setting of chronic TMPD-induced peritoneal inflammation by transplanting lipogranulomas from TMPD-treated mice seropositive for anti-U1A autoantibodies into non-TMPD-treated (anti-U1A negative) recipients. After 35 days, the transplanted lipogranulomas had an appearance similar to that of pre-transplant ectopic lymphoid tissue when stained with hematoxylin & eosin (Fig. 2A). The transplanted tissue adhered tightly to the mesothelial surface of the peritoneum overlying the abdominal musculature and was vascularized, as determined by the distribution of intravenously injected Evans Blue dye (EBD) (Fig. 2B). Blue staining of the transplanted lipogranulomas confirmed that blood vessels in the transplanted ectopic lymphoid tissue (8) became connected to the host’s circulation. To verify that the cells in the transplanted lipogranulomas remained viable, a single cell suspension was stained with annexin V and 7AAD, markers of apoptosis and necrosis, respectively, and the total cell population was analyzed by flow cytometry (Fig. 2C). Approximately 50% of the total cells isolated from transplanted lipogranulomas were annexin V− 7AAD−, similar to the percentage of live cells found in pre-transplant lipogranulomas (57% annexin V− 7AAD−) and mineral oil-induced lipogranulomas (54% annexin V− 7AAD−). Thus, not only were the lipogranulomas re-vascularized after transplantation, but they also contained similar numbers of viable cells to those found in pre-transplant lipogranulomas.

Figure 2. Transplanted lipogranuloma become vascularized.

(A) Endogenous TMPD-induced or TMPD-induced and transplanted lipogranulomas were removed from BALB/c mice and 5 μm paraffin-embedded sections were stained with hematoxylin & eosin. (B) Mice transplanted with TMPD-induced lipogranulomas were injected i.v. with 0.5% Evans blue dye (EBD+, n = 5) or left un-injected (EBD−, n = 3). (C) Single cell suspensions from lipogranulomas pre-transplantation or 35 days post-transplantation (n = 6) were analyzed by flow cytometry (gated on all cells) for dead/dying cells using annexin-5 and 7-AAD staining. (D) Cellular composition of spleen and lipogranulomas was evaluated by gating on living cells (annexin-V and 7-AAD staining). Upper panel, percentages of B cells (B220+) and T cells (CD4+) in the transplanted lipogranulomas (day 35) compared to pre-transplanted lipogranulomas and spleen. Lower panel, percentages of monocytes (CD11b+, B220−) in spleen and lipogranulomas.

By flow cytometry, the cellular composition of transplanted lipogranulomas was similar to that of pre-transplant lipogranulomas and recipient spleen (Fig. 2D). At day 35, the transplanted lipogranulomas contained 28% CD4+ T cells and 46% B cells, vs. 24% and 51%, respectively in non-transplanted lipogranulomas (Fig. 2D). However, lymphocytes from the transplanted lipogranulomas did not express CD69 (Fig. 1B). Similarly, the percentages of CD11b+B220−cells (monocytes) in the transplanted and pre-transplant lipogranulomas were similar (11% and 10%, respectively), but greater than the percentage in the spleen (3.4%) (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that the composition of pre- and post- transplant ectopic lymphoid tissue is similar, although the transplanted lipogranulomas lack a population of activated (CD69+) lymphocytes.

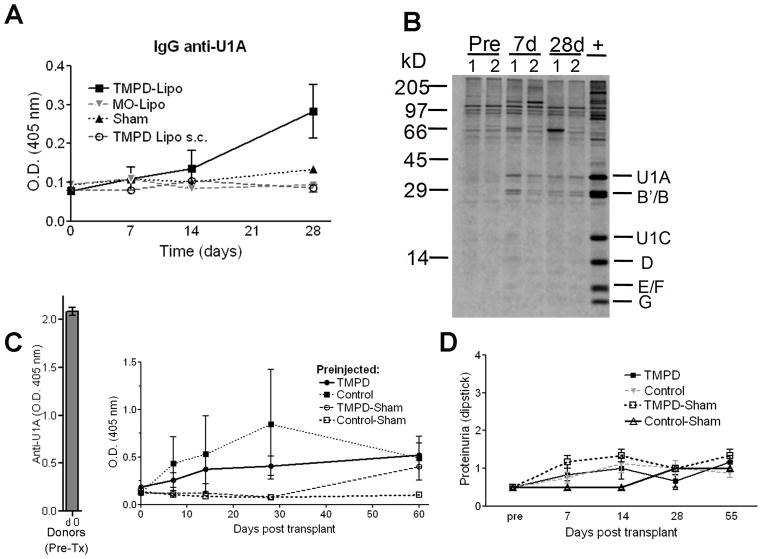

Production of anti-U1-A autoantibodies by transplanted lipogranulomas

Lipogranulomas contain autoantibody-secreting cells detectable using ELISPOT assays (8). To evaluate the functionality and ultimate fate of these cells following transplantation of lipogranulomas from anti-U1A positive TMPD-treated mice, serum levels of IgG anti-U1A autoantibodies were determined in the transplant recipients at 0, 7, 14, and 28 days. Serum anti-U1A activity was detectable by ELISA in mice receiving TMPD lipogranulomas starting at day 7–14 post-transplant and increased up to 28 days post-transplant (Fig. 3A). However, anti-U1A levels in sera from the transplant recipients were lower than those in the donor mice, probably reflecting the transplantation of only a small number of lipogranulomas (2 to 5 per recipient) and failure of the donor PC/PB to expand after transplantation (Fig. 3A). These autoantibodies also could be detected in sera of the recipients by immunoprecipitation (Fig. 3B). In contrast, mice transplanted with mineral oil (anti-U1A negative) lipogranulomas, mice transplanted subcutaneously with TMPD-induced lipogranulomas from anti-U1A+ mice, and sham operated mice did not develop detectable levels of anti-U1A by 28 days (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Serum levels of anti-U1A antibodies in recipient mice.

Serum samples were collected at 7, 14, 28, and 35 days from mice transplanted i.p. with U1A+ TMPD-induced lipogranulomas (TMPD-Lipo, n = 7) or U1A−mineral oil-induced lipogranulomas (MO-Lipo, n = 5), transplanted subcutaneously with U1A+ TMPD-induced lipogranulomas (TMPD-Lipo s.c., n = 4), or sham transplanted (Sham, n = 4). (A) Sera were tested for IgG anti-U1A antibodies by ELISA. (B) Anti-U1A antibodies in the sera of two mice transplanted i.p with U1A+ TMPD-induced lipogranulomas were detected by immunoprecipitation of [S35]-labeled cell extract using serum samples obtained pre-transplantation or 7 or 28 days afterward. Positions of the U1 small ribonucleoprotein proteins U1A, B′, B, U1C, D, E, F, and G are indicated on the right and molecular weight markers in kilodaltons (kD) are shown on the left. (+), positive anti-Sm/RNP control (TMPD-treated BALB/c mouse serum). (C) Mice were injected i.p. 2 weeks prior to surgery with TMPD (n = 7) or left untreated (Control, n = 7). The mice then either underwent transplantation with lipogranulomas from anti-U1A+ mice or underwent sham surgery without transplantation. Sera collected at days 0, 7, 14, 28, and 60 were tested for IgG anti-U1A antibodies by ELISA. (D) Urine was collected from the mice in (C) and tested for protein (Albustix) on days 0, 7, 14, 28, and 55 following surgery. Data are representative of two experiments.

To determine if autoantibody production by the transplanted ectopic lymphoid tissue was affected by chronic peritoneal inflammation, recipient mice were pre-treated with TMPD or mineral oil 2 weeks prior to transplantation with lipogranulomas from anti-U1A positive donors. In comparison with untreated controls, the strong inflammatory response induced 2 weeks after TMPD treatment, which is characterized by chronic IFN-I production (20), did not increase serum autoantibody levels in the recipient mice (Fig. 3C). Sham-transplanted mice also were pre-treated with TMPD to verify that pre-treatment with TMPD did not induce anti-U1A autoantibody production independently of the transplanted ectopic lymphoid tissue. These control mice did not produce anti-U1A autoantibodies. Anti-U1A antibodies remained detectable in the sera of mice transplanted with lipogranulomas from TMPD-treated donors up to 60 days afterward (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the TMPD pre-treated sham mice began to produce anti-U1A by day 60 post-transplant (80 days after TMPD pre-treatment), consistent with previous observations that TMPD treated mice develop an anti-Sm/RNP response at ~ 3 months post-treatment (6). Despite producing autoantibodies, the transplanted mice failed to develop proteinuria (Fig. 3D). These data suggested that the transplanted lipogranulomas contained PC/PB capable of maintaining serum anti-U1A autoantibody levels over an extended period.

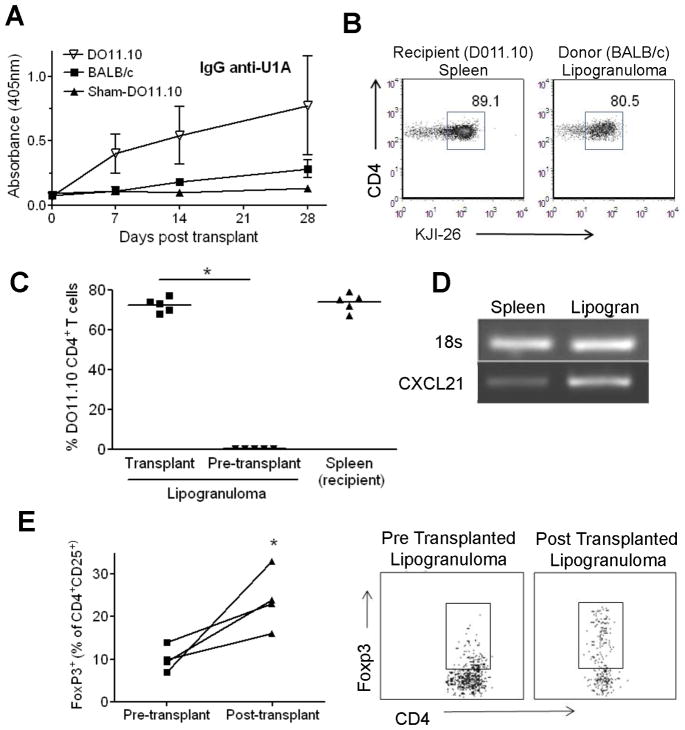

Recipient T cells enter the transplanted lipogranulomas

To examine the role of T cells in the production of autoantibodies in the recipients, we transplanted anti-U1A+ lipogranulomas from BALB/c mice into BALB/c CD4+ T cell transgenic DO11.10 mice. Unexpectedly, serum anti-U1A autoantibody levels were higher in DO11.10 recipients than in wild type controls (P = 0.02, Mann-Whitney; Fig. 4A). Using an antibody against the transgenic T cells (KJ1-26), we found that by 35 days after transplantation, donor lipogranulomas were repopulated with numerous recipient T cells (Fig. 4B, C). Approximately 75–80% of the CD4+ T cells in the transplanted lipogranulomas were of recipient (transgenic) origin, a percentage similar to that in the spleen. The transplanted lipogranulomas expressed mRNA for the T cell attractive chemokine CXCL21 (Fig. 4D), which may mediate the influx of recipient T cells into the transplant (21). These data suggest that naïve T cells may transit through the transplanted ectopic lymphoid tissue in a manner analogous to that in authentic secondary lymphoid tissue.

Figure 4. Recipient T cells repopulate transplanted lipogranulomas.

(A) D011.10 or BALB/c mice received U1A+ lipogranulomas from TMPD treated BALB/c mice (n = 6) or were sham operated (Sham-DO11.10). Sera were collected at days 0, 7, 14, 28, 35 following surgery and IgG anti-U1A antibodies were assessed by ELISA. (B) Lipogranulomas and spleen were harvested from DO11.10 mice 35 days after transplantation and the percentages of recipient transgenic (CD4+KJ1-26+) T cells were determined by flow cytometry (gated on lymphocytes and CD4+ cells). (C) BALB/c lipogranulomas were transplanted into DO11.10 recipients and transgenic T cells (KJ1-26+) as a percentage of total CD4+ T cells was compared in lipogranulomas 35 days after transplantation vs. pre-transplant lipogranulomas (* P = 0.007, Mann-Whitney test). (D) BALB/c lipogranulomas were transplanted into BALB/c recipients and cDNA from transplanted lipogranulomas (Lipogran) and recipient spleen was tested for CXCL21 expression by RT-PCR and compared with 18S rRNA expression (representative of four experiments). (E) T cells with a regulatory phenotype (CD4+CD25+FoxP3+) were analyzed from pre-transplant (BALB/c) lipogranulomas and from lipogranulomas 35 days post-transplantation into BALB/c recipients by staining for surface markers CD4 and CD25and the intracellular marker FoxP3 (flow cytometry, n = 4). The percentage of T cells with a regulatory phenotype increased post-transplantation (* P = 0.02, Mann-Whitney test).

The increased levels of serum anti-U1A autoantibodies in OVA-specific TcR transgenic DO11.10 recipients raised the possibility that the recipient’s regulatory T cells might reduce anti-U1A autoantibody production, since CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells can down-regulate autoantibody production (22). Consistent with that possibility, numbers of these cells in the ectopic lymphoid tissue increased after transplanting wild type lipogranulomas into wild type recipients (Fig. 4E). The percentage of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells in the lipogranulomas, presumably of recipient origin (Fig. 4E), increased in 4 out of 4 mice over a period of 28 days (mean 11.1% pre-transplant vs. 21.4% post-transplant, P = 0.02, Mann Whitney). However, the presence of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ T cells was not associated with complete suppression of anti-U1A autoantibody production (Fig. 3A).

Autoantibodies are derived exclusively from donor B cells

We examined whether the recipient’s B lymphocytes also could enter the transplanted ectopic lymphoid tissue by transplanting anti-U1A+ lipogranulomas from allotype congenic CB.17 (Ighb) donors into BALB/c (Igha) recipients. We took advantage of the fact that anti-U1A autoantibodies induced by TMPD are predominantly IgG2a in BALB/c mice (23). Instead of IgG2aa, the CB.17 strain expresses IgG2ab (also termed IgG2c). Using an IgG2a allotype-specific anti-U1A ELISA, we found that all of the serum anti-U1A autoantibodies in BALB/c mice transplanted with CB.17 lipogranulomas were of donor (CB.17) origin (Fig. 5A). The level of serum IgG2aa (BALB/c origin) anti-U1A autoantibodies was no different from that of sham transplanted mice. In contrast, IgG2ab (CB.17 origin) anti-U1A autoantibody levels increased significantly following transplantation, indicating that the anti-U1A autoantibodies were produced exclusively by donor-derived PC/PB.

Figure 5. Anti-U1A antibodies are derived exclusively from donor lipogranulomas.

(A) U1A+ lipogranulomas from CB.17 (Ighb) donors were transplanted into BALB/c (Igha) recipients (n = 6). Sera were collected at days 0, 7, 14, 28, 35 and IgG2ab/IgG2c (TMPD-IgG2c) or IgG2aa (TMPD-IgG2a) anti-U1A antibodies were assessed by ELISA. IgG2ab anti-U1A antibodies also were measured in control, sham transplanted, mice (Sham-IgG2c). (B and C) Transplanted lipogranulomas or non-transplanted lipogranulomas from CB.17 mice were harvested at day 35 and the B cells (B220+) were stained for recipient (IgMa) or donor (IgMb) allotypes (flow cytometry). A representative plot shows the percentage of allotype-specific B cells in transplanted lipogranulomas pre-transplant and post-transplant into BALB/c recipients. Data are representative of two experiments (* P = 0.02, Mann-Whitney test). (D) cDNA from a BALB/c transplanted lipogranuloma (Lipogran) or spleen from a recipient mouse was tested for CXCL13 expression (RT-PCR) compared with 18S rRNA (representative of four experiments).

Since T cells populating the transplanted lipogranulomas were primarily of recipient origin, we next examined whether B cells populating the lipogranulomas post-transplant were of donor or recipient origin. The presence of donor and recipient surface IgM+ B cells in the transplanted lipogranulomas was examined 35 days post-transplant. Pre-transplantation, the lipogranulomas contained exclusively CB.17 (donor-derived, IgMb) B cells (Fig. 5B, top panels). In contrast, by day 35 post-transplantation, these cells were replaced by B cells of recipient origin (BALB/c, IgMa) (Fig. 5B, bottom panels). Post-transplantation, the lipogranulomas contained significantly more recipient (IgMa) than donor (IgMb) B cells (Fig. 5C, P = 0.002 Mann-Whitney). Similar to the expression of the T cell attractive chemokine CXCL21 (Fig. 4D), the B cell chemokine CXCL13 was expressed in the transplanted lipogranulomas (Fig. 5D). These data suggest that within 1 month of transplantation, donor B and T lymphocytes in the lipogranulomas were largely replaced by lymphocytes of recipient origin. Nevertheless, the serum anti-U1A autoantibody levels continued to increase over that time and the autoantibodies were exclusively of donor origin. At the same time, activated (CD69+) donor B cells within the ectopic lymphoid tissue were replaced by host lymphocytes exhibiting an unactivated (CD69−) phenotype (Fig. 1A, B). We next asked whether the recipients’ circulating anti-U1A autoantibodies were derived from pre-existing PC/PB or from the differentiation of donor memory B cells residing in the transplanted lipogranulomas.

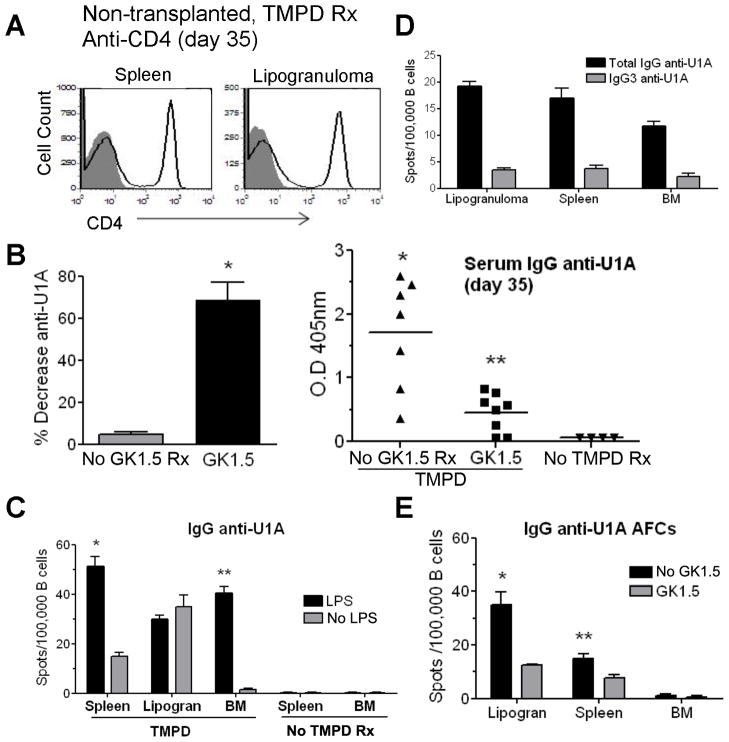

Effect of CD4+ T cell depletion on PC numbers and serum autoantibody levels

As the activation of memory B cells often requires cognate interaction with CD4+ T cells (15), CD4+ T cells were depleted in the donor and recipient mice using monoclonal antibody GK1.5. Anti-U1A+ donor mice were treated with either GK1.5 or a rat anti-human IL-4 antibody control for four days prior to surgery. In mice receiving GK1.5, nearly all CD4+ T cells were eliminated from the donor lipogranulomas compared to the control (Fig. 6A). Recipient mice were treated with GK1.5 or the irrelevant control antibody (rat anti-human IL-4) at the time of surgery and continued to receive weekly treatments up to 35 days post-surgery. CD4+ T cells remained depleted in the peripheral blood of the GK1.5-treated recipient mice throughout the 35-day duration of this experiment, whereas a control antibody had no effect (Fig. 6B). After 35 days, lipogranulomas and spleens were excised from mice that received GK1.5 or control antibody and the numbers of viable (CD4+, Sytox blue−) cells were determined by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 6C, CD4+ T cells were undetectable in the GK1.5 treated mice. The numbers of CD138+CD44+ PC/PB decreased substantially in the spleen and lipogranulomas of the GK1.5 treated mice (Fig. 6D, P = 0.016, Mann Whitney test, for both spleen and lipogranulomas). In contrast, depletion of CD4+ cells had little effect on the levels of serum IgG anti-U1A autoantibodies in transplanted mice at 35 days (Fig. 6E). As the half-life of IgG antibodies in an adult mouse is ~3 weeks (24), the unchanged autoantibody levels suggest that serum anti-U1A autoantibodies in transplanted mice were derived at least in part from a population of PC/PB that was maintained over a period of 5 weeks independently of cognate T-B interaction.

Figure 6. Serum anti-U1A antibodies in transplanted mice persist after T cell depletion.

(A) Depletion of T cells. U1A+ lipogranulomas were isolated from TMPD treated mice injected 4 days earlier with the CD4 T cell-depleting mAb GK1.5 (n = 5, right) or rat anti-human IL-4 antibody (Control n = 4, left). Flow cytometry of single cell suspensions of lipogranuloma cells from the donor mice using anti-B220 and anti-CD4 antibodies verified nearly complete depletion of CD4+ T cells in the GK1.5 treated mice. In contrast, treatment with an isotype control (rat anti-human IL-4 mAb) had no effect. (B) Recipient mice (which were transplanted with lipogranulomas from GK1.5-treated or rat anti-human IL-4 antibody anti-U1A+ donors) were treated at day 0 and every 7 days thereafter with either GK1.5 or control (rat anti-human IL-4) antibodies. CD4+ T cell depletion was monitored in peripheral blood every 7 days by flow cytometry. (C) Lipogranulomas and spleen were excised from recipient mice 35 days after transplantation and CD4 T cells were examined by flow cytometry. Shaded, GK1.5-treated recipients; open, control antibody-treated recipients. (D) Plasma cells (CD44+ CD138+) from recipient spleen and transplanted lipogranulomas were analyzed at day 35 by flow cytometry after treating both the donor and recipient with GK1.5 or control antibody (*P = 0.01, Mann-Whitney test). (E) Sera were collected from either GK1.5 or control antibody treated recipients at day 0, 7, 14, 28 and 35 post-transplantation. Serum IgG anti-U1A levels were assessed by ELISA (representative of two experiments).

Effect of CD4+ T cell depletion in non-transplanted mice

We next examined whether depleting CD4+ T cells had any effect on anti-Sm/RNP autoantibody production in non-transplanted TMPD-treated mice. Anti-Sm/RNP and anti-U1A autoantibodies cannot be induced by TMPD in nude mice or T cell receptor deficient mice (8, 25). However, the role of T cells in maintaining autoantibody production once it has been established has not been examined. We administered GK1.5 monoclonal antibodies weekly to U1A+ TMPD treated mice. Peripheral blood CD4 counts were monitored every 7 days to verify depletion of all CD4+ cells (data not shown). After 35 days of weekly GK1.5 treatment, lipogranulomas and spleen were harvested and the presence of live CD4+ T cells was determined by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 7A, the lipogranulomas and spleen did not contain any CD4+ T cells. In contrast to the transplanted mice (Fig. 6), depletion of CD4+ T cells in non-transplanted mice caused a 60% decrease in the levels of serum IgG anti-U1A autoantibodies between days 0 and 35 (Fig. 7B, left). However, despite substantially decreasing after T cell depletion, serum IgG anti-U1A remained significantly higher in GK1.5-treated mice than the background levels in non-TMPD-treated controls (Fig. 7B, right). This may reflect a population of anti-U1A secreting cells similar or identical to those observed in the transplanted lipogranulomas (Fig. 6), although we cannot exclude the possibility that the residual autoantibody levels might have been due to incomplete depletion of CD4+ T cells in other sites, such as omentum, mesenteric lymph node, parathymic lymph node, or BM.

Figure 7. Non-transplanted mice may have three populations of anti-U1A B-lineage cells.

Anti-U1A+ TMPD-treated mice were administered GK1.5 or control antibody for 35 days. (A) Spleen and lipogranulomas were devoid of CD4+ T cells after GK1.5 treatment (shaded) whereas CD4+ T cells were still present after treating with control antibody (open). (B) Left, serum IgG anti-U1A antibodies from TMPD-treated mice pre-GK1.5 or isotype control antibody (No GK1.5 Rx) treatment 35 days post-treatment. The % decrease of IgG anti-U1A post-treatment is shown (*P = 0.03, Mann-Whitney test). Right, IgG anti-U1A autoantibody levels in sera from TMPD mice treated with GK1.5 or control antibody (No GK1.5 Rx; *P = 0.006, Mann-Whitney test) or normal mouse serum from non-TMPD-treated BALB/c mice (No TMPD Rx) (** P = 0.004, Mann-Whitney test). (C) Lipogranulomas, spleen, and bone marrow were harvested from anti-U1A+ TMPD treated mice or from non-TMPD treated controls (No TMPD Rx). B cells were negatively selected and cultured in the presence or absence of LPS (5 μg/ml) for 5 days. IgG anti-U1A antibody production from cultured B cells was measured by ELISPOT (* P ≤ 0.02; ** P ≤ 0.04 Mann-Whitney test). (D) Anti-U1A ELISPOT assays were performed to determine if the antigen-specific IgG detected after LPS stimulation was of a relatively T cell-independent isotype (IgG3) or more T cell-dependent isotypes (IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b). B cells were stimulated for 5 days with LPS and then the ELISPOT assays were performed using anti-IgG antibodies (reactive with all IgG isotypes) or anti-IgG3 antibodies. (E) Lipogranulomas, spleen and bone marrow were harvested from anti-U1A+ TMPD treated mice treated weekly for 35 days with either GK1.5 or control mAb (No GK1.5). B cells were negatively selected and IgG anti-U1A antibody production from cultured B cells was measured by ELISPOT (* P ≤ 0.02; ** P ≤ 0.04 Mann-Whitney test). Numbers of IgG anti-U1A spots in (C) and (E) were quantified per 100,000 B cells.

Anti-U1A memory B cells are present in the BM and spleen

IgG memory cells are a hallmark of the germinal center reaction and the maturation of these cells into PC/PB generally is dependent on CD4+ T cells (15). This suggested that some anti-U1A autoantibodies could have been produced by PC/PB derived from the activation of switched memory B cells. Murine memory B cells, but not PC, can be stimulated by LPS to secrete antibody in vitro (16, 17). To look for anti-U1A memory cells, B cells from the lipogranulomas, spleen, or BM of TMPD-treated, anti-U1A+, mice were cultured in the presence or absence of LPS (5 μg/mL) followed by assessment of the numbers of anti-U1A secreting cells by ELISPOT. In the spleen, but not the lipogranulomas, the number of IgG anti-U1A spots increased significantly in the presence of LPS, consistent with the presence of a switched memory B cell population (Fig. 7C). Unexpectedly, unstimulated BM from TMPD-treated mice did not contain IgG anti-U1A producing cells, whereas the number of spots increased dramatically after LPS stimulation. In contrast, LPS treatment of spleen or BM from control (non-TMPD-treated) mice did not stimulate the secretion of anti-U1A antibodies detectable by ELISPOT assay (Fig. 7C). Since naïve B cells can be stimulated by LPS to produce T cell independent IgG3 antibodies (26–28), IgG3 spots were compared to total IgG to verify that most of the anti-U1A was of T cell dependent isotypes (i.e. IgG1, IgG2a, and/or IgG2b) (Fig. 7D). These data indicate that the BM and spleen of TMPD-treated mice, but not control (non-TMPD-treated) mice, contain a population of anti-U1A B cells that do not secrete autoantibodies at rest but can be stimulated to secrete anti-U1A by TLR4 ligation. These are likely to represent memory B cells and/or early plasmablasts. Interestingly, although flow cytometry suggests that the BM, spleen, and lipogranulomas all contained B cells phenotypically consistent with memory B cells (B220+CD38+IgM−, Fig. S1B), the memory cells in lipogranulomas could not be activated to make anti-U1A by LPS and therefore may not have participated in autoantibody production in the mice transplanted with lipogranulomas. When T cells were depleted in non-transplanted anti-U1A+ mice using GK1.5 antibodies, the number of anti-U1A spots in the lipogranulomas and spleen decreased by about 50% (Fig. 7E). Thus, T cells appear to help maintain the numbers of anti-U1A PC/PB (Fig. 7E) as well as at least a portion of the serum anti-U1A autoantibody levels (Fig. 7B). This could reflect an effect on the formation of new anti-U1A PC/PB, on the survival of these cells, or both.

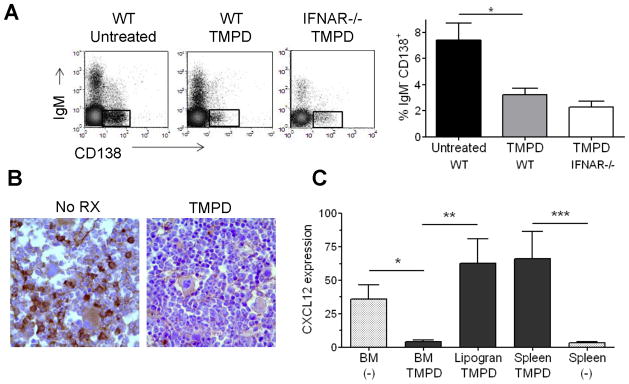

TMPD treatment depletes PC/PB from the BM

A striking and unexpected observation of the ELISPOT experiments (Fig. 7C, E) was the absence of spontaneous anti-U1A secreting cells in the BM, a major site for the accumulation of long-lived PC (29). To examine whether the absence of PC/PB was unique to autoantibody producing cells or a more general phenomenon, we determined the effects of TMPD treatment on the total number of CD138+IgM−B220− PC/PB in the BM of untreated or TMPD-treated (after 3–4 months) wild type mice. As shown in Fig. 8A, numbers of BM PC/PB were substantially lower in TMPD-treated wild type mice than in non-TMPD treated mice. Decreased BM PC/PB also were apparent following immunohistochemical staining of the BM for intracellular κ-light chain+ cells (Fig. 8B). Since increased IFN-I levels cause lymphopenia in the BM (30), we examined whether IFN-I production induced by TMPD caused the decreased numbers of BM PC. However, in the BM of TMPD-treated IFNAR −/− mice, the percentage of CD138+IgM− B220− PC was comparable to the percentage in wild type TMPD treated mice (Fig. 8A). Thus, although signaling through the IFNAR may skew hematopoietic development, it was not responsible for the decreased numbers of BM PC/PB following TMPD treatment.

Figure 8. TMPD treatment depletes PC/PB from the bone marrow.

(A) Bone marrow was harvested from TMPD treated BALB/c or untreated wild type (WT) BALB/c mice or from TMPD-treated BALB/c IFNAR−/− mice. The presence of CD138+IgM− PC/PB was detectedby flow cytometry (left panel). The percentages of bone marrow PC/PB were compared between each group of mice (right panel) (*P ≤ 0.02 Mann-Whitney test, untreated vs. TMPD treated). (B) Immunoperoxidase staining for κ light chain-expressing PC/PB in decalcified, formalin-fixed bone marrow sections from untreated (No Rx) or TMPD-treated BALB/c mice. (C) Using real-time PCR the amount of CXCL12 was quantified from bone marrow (BM), lipogranuloma (Lipogran), and spleen cDNA of TMPD-treated or untreated (-) mice (*P = 0.02; **P = 0.03 Mann-Whitney test, *** P = 0.01 Mann-Whitney test

PC/PB are attracted to the BM niches by CXCL12 abundant reticular (CAR) cells and other cells producing the chemokine CXCL12 (SDF-1)(31, 32) (33). However, the recruitment of PC/PB to BM niches is independent from their survival, which depends on APRIL rather than CXCL12 (34). CXCL12 expression was much lower in the BM of TMPD treated mice than in untreated controls (Fig. 8C). In contrast, CXCL12 expression in the spleen was enhanced by TMPD treatment and CXCL12 also was expressed at high levels in lipogranulomas. Thus, TMPD treatment may cause the depletion of PC/PB from the BM by reducing CXCL12 expression. Conversely, we hypothesized that the high level of CXCL12 expression in the ectopic lymphoid tissue might promote the accumulation of PC/PB in the lipogranulomas.

CXCR4 retains autoantibody producing PC/PB in lipogranulomas

Inhibition of the CXCL12 receptor CXCR4 can deplete autoantibody producing PC in kidneys of lupus mice (35). To see if CXCL12/CXCR4 retains PC in ectopic lymphoid tissue, TMPD-treated anti-U1A+ mice were treated with either the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 or PBS before transplanting lipogranulomas into untreated anti-U1A− recipients. After AMD3100 treatment the numbers of CD138+CD44+ PC/PB in the spleen and lipogranulomas were greatly reduced (Fig. 9A). After transplanting lipogranulomas from AMD3100-treated mice, there was little or no autoantibody production in the recipient mice for up to 35 days (Fig. 9B). However, although anti-U1A secreting PC/PB were nearly absent in the transplanted lipogranulomas from AMD3100-treated mice (Fig. 9A), lipogranulomas from AMD3100-treated and control mice contained similar percentages of total PC/PB 35 days after transplanting into untreated recipients (Fig. 9C), suggesting that the recipient’s PC/PB can home to the transplanted lipogranulomas. Thus, the lipogranulomas are likely to continue producing high levels of CXCL12 after transplantation.

Figure 9. CXCR4-CXCL12 interactions facilitate PC/PB accumulation in lipogranulomas.

(A) Single cell suspensions of spleen or lipogranuloma cells were obtained from either AMD3100 or PBS treated mice. The percentages of PC/PB (CD138+CD44+) were determined by flow cytometry. (B) Anti-U1A+ TMPD treated mice were treated with AMD3100 (TMPD + AMD3100) or PBS (TMPD) and 24 h later lipogranulomas were transplanted into untreated U1A− recipient mice. Other mice underwent sham surgery without transplantation. Sera were collected at days 0, 7, 14, and 35 post-transplant and serum IgG anti-U1A levels were assessed by ELISA (optical density at 405 nm). (C) Mice were transplanted with lipogranulomas from TMPD-treated mice or from TMPD-treated mice that received AMD3100 24 h prior to transplantation. Percentages of CD44+CD138+ PC/PB were determined by flow cytometry in single cell suspensions from spleen and lipogranulomas of the recipient mice at day 35. (D) Accumulation of newly generated PB in lipogranulomas after AMD3100 treatment. TMPD treated mice received either AMD3100 or PBS for three days, followed by BrdU 0.2 mg i.p. every 12 h for 2 d. Twelve hours after the last BrdU injection spleen and lipogranulomas were harvested. The % of BrdU+ IgM−CD138+ PB in spleen or lipogranulomas from each treatment group is shown.

To evaluate the kinetics of plasmablast accumulation in the spleen and ectopic lymphoid tissue, TMPD-treated mice were fed BrdU for two days and the percentage of BrdU+ PC/PB was determined 12 hours later. As shown in Figure 9D, BrdU+ plasmablasts were present in both the ectopic lymphoid tissue (7.5% BrdU+CD138+IgM− cells) and the spleen (5% BrdU+ CD138+IgM−cells). The numbers of plasmablasts in these sites were unaffected by pre-treatment with AMD3100 prior to BrdU labeling.

Discussion

Antigen-specific B and T lymphocytes accumulate in ectopic lymphoid tissue induced by i.p. injection of TMPD and autoantibody secreting cells (ASC) can be detected readily (11). Here we show that when ectopic lymphoid tissue from anti-U1A autoantibody positive mice was transplanted into non-TMPD treated recipients, serum IgG anti-U1A autoantibodies derived from donor PC/PB were produced for up to 2 months in the absence of de novo autoantibody production by the recipients’ B cells. Unexpectedly, few cells spontaneously producing anti-U1A were found in the BM. Instead, the BM and spleen of TMPD-treated mice contained numerous non-secreting IgG anti-U1A B cells, likely to be memory cells, which could be activated in vitro by the TLR4 ligand LPS to differentiate into ASC. Interestingly, the de novo generation of anti-U1A B cells appears to depend on ongoing peritoneal inflammation, since the transplanted ectopic lymphoid tissue did not generate anti-U1A B cells of recipient origin.

Ectopic lymphoid tissue is a reservoir for anti-U1A PC/PB

In addition to regaining functional capacity (revascularization and the ability to attract T and B lymphocytes) following transplantation (Fig. 2B, Fig. 4C, Fig. 5C), lipogranuloma ASC from anti-U1A+ donors produced anti-U1A autoantibodies at levels sufficient for detection in the recipients’ serum (Fig. 3). Autoantibody levels in the recipients were lower than those in the donors, probably because 2–5 lipogranulomas were transplanted (vs. 10–20 large lipogranulomas in each donor mouse). The lower level of autoantibodies and/or the relatively short exposure of the recipients’ kidneys to them may explain the absence of proteinuria in the recipients (Fig. 3D). Also, the recipients lack the chronic TMPD-induced inflammatory response seen in donor mice. This response, which leads to the chronic export of inflammatory (Ly6Chi) monocytes from the BM (42), may contribute to renal damage as inflammatory monocyte/macrophage recruitment is thought to be important in the pathogenesis of lupus nephritis (43).

The ectopic lymphoid tissue was a significant reservoir for PC/PB secreting IgG anti-U1A (anti-RNP) autoantibodies with approximately double the number of U1A-specific ASC per 100,000 B cells as the spleen (Fig. 7). Lipogranuloma PC/PB were the likely source of serum anti-U1A antibodies in the recipients, since serum autoantibodies were not seen after transplanting lipogranulomas from donors pre-treated with AMD3100 (Fig. 9B). Nevertheless, despite depletion of PC/PB by pre-treatment with AMD3100, “normal” numbers of actively dividing PB had re-accumulated in the ectopic lymphoid tissue 48 hours after removing AMD3100 (Fig. 9D). After transplantation, serum IgG anti-U1A levels peaked at ~ 1 month but were maintained for at least 2 months (Fig. 3C). Since short-lived PC have a lifespan of < 2 weeks (36,37) and the half-life of murine IgG is < 3 weeks (24), some of the serum autoantibodies in the recipients of anti-U1A+ lipogranulomas may have been produced by long-lived PC residing in ectopic lymphoid tissue niches, which like those in the BM may be a site where PC/PB survival factors such as APRIL are produced (34). Like PC/PB, APRIL-producing eosinophils, megakaryocytes, and other cell types are recruited to the niche by CXCL12. In the absence of APRIL, antibody production by adoptively transferred tetanus toxoid-specific PC/PB declines rapidly and is nearly absent 5 weeks after transfer (34). The nature of the presumptive lipogranuloma survival niches and the cell type(s) producing CXCL12 in ectopic lymphoid tissue remain to be determined, though Ly6Chi monocytes [critical for PC survival in the BM niches (34)], are numerous in the lipogranulomas (20).

It is noteworthy that pre-treating the donor with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (44) not only depleted PC from the anti-U1A+ lipogranulomas but also abolished the ability of lipogranulomas to generate serum anti-U1A autoantibodies upon transplantation (Fig. 9A-B). Thus, lipogranuloma B cells cannot replenish the anti-U1A PC/PB. The effects of AMD3100 treatment are consistent with a recent report implicating CXCR4/CXCL12 in the pathogenesis of lupus (35), and suggest that CXCR4 antagonists, already in clinical use for the treatment of HIV infection, may be useful for depleting autoreactive PC/PB. Indeed, both AMD3100 (45) and thalidomide, which also inhibits CXCL12/CXCR4 interactions (46), mobilize malignant PC in the BM of multiple myeloma patients.

The BM and spleen of TMPD-treated mice contain anti-U1A memory B cells

Serological memory is maintained by long-lived PC, which continue to produce immunoglobulin for many years, and memory B cells, which can be induced to differentiate into short- and/or long-lived PC by T cells and/or TLR ligand stimulation (13, 47–49). Ectopic lymphoid tissue in TMPD-treated mice contained PC/PB producing anti-U1A autoantibodies. Since GK1.5 treatment could reduce the numbers of IgG anti-U1A ASCs in lipogranulomas and spleen by about two-thirds (Fig. 7E), we suspected that some of these ASCs were generated by the terminal differentiation of memory B cells. Memory B cells, but not mature PC, can be stimulated to produce antibody in vitro with TLR ligands, such as LPS (16). Although spontaneous anti-U1A producing ASCs were absent in the BM, we found a population of B cells in the BM and spleen that did not secrete IgG anti-U1A autoantibodies spontaneously, but did so after LPS stimulation (Fig. 7C). These cells functionally resemble memory B cells and B cells with a memory phenotype were detected in the BM by flow cytometry (Fig. S1B). In contrast, the number of anti-U1A ASCs in lipogranulomas was unchanged by LPS stimulation, suggesting that although the ectopic lymphoid tissue contains PC/PB, there may be few anti-U1A memory cells in that location or that they are incapable of responding to LPS stimulation. Retention of anti-U1A memory B cells in the BM is unlikely to involve CXCL12/CXCR4 interactions (50), since CXCL12 was greatly decreased in the BM of TMPD-treated mice but significantly increased in spleen and lipogranulomas (Fig. 8C). We hypothesize that an as yet undefined chemokine attracts/retains anti-U1A memory B cells in the bone marrow and spleen. The BM anti-U1A B cells may represent a renewable pool of switched-memory cells capable of developing into autoantibody secreting cells that can home to ectopic lymphoid tissue in response to CXCL12.

It is of interest that the number of PC in transplanted lipogranulomas decreased substantially when CD4+ T cells were depleted with GK1.5 mAb (Fig. 6). PC/PB are attracted to BM survival niches by stromal cells producing CXCL12 whereas their survival within these niches is critically dependent on the interaction of PC BCMA with APRIL (34, 51, 52). T cells are not required to maintain PB in these survival niches (12, 13). Similarly, the survival of memory B cells depends on factors other than cognate T cell help (53). In contrast, in many (but not all) cases the generation of PB from switched memory B cells requires the interaction of T cell CD40L with B cell CD40 and other signals (15, 53–55). Together, the reduction of PC/PB in the ectopic lymphoid tissue following GK1.5 treatment along with the rapid re-appearance of BrdU+ PB in the lipogranulomas following AMD3100 treatment (Fig. 9D) suggest that the presumptive memory B cells in the BM and spleen may mature into PB that migrate to the ectopic lymphoid tissue in response to the high levels of CXCL12 produced there (Fig. 8C). Our data are consistent with previous reports that long- and short- lived PC home to the inflamed kidneys and spleen in NZB/W mice (56). Autoantibody producing PC also accumulate in ectopic lymphoid tissue in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, or myasthenia gravis (4,34,42).

Our data are consistent with previous reports that the BM contains memory B cells specific for exogenous antigens, serving as a site of antigen-driven and T cell dependent differentiation of memory B cells into ASCs (13,47). Interestingly, the BM also is a site of CD4+ memory T cell accumulation (57), suggesting that the memory B cells also found there might receive cognate help and begin the process of terminal differentiation within the BM. Remarkably, PC/PB were deficient in the BM of TMPD-treated mice, probably due to inflammation-induced reductions of CXCL12 (Fig. 8C). CXCL12 recruits PC to survival niches in the BM (58) and inflammation induced by oil adjuvants alters lymphopoiesis and granulopoiesis by altering CXCL12 expression (59, 60). Our data suggest that in addition to decreasing lymphopoiesis and increasing myeloid precursors, TMPD treatment profoundly alters the PC compartment. Whether this reflects the action of TNFα and IL-1β on CXCL12 expression (60), the action of G-CSF on CXCR4 expression (61), or other as yet unidentified factors is under investigation. As inflammation-induced alterations of B cell homeostasis may be involved in the pathogenesis of lupus autoantibodies, the current observations may suggest new therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R01-AR44731, R37-GM40586, and R01-GM81923 from the US PHS and by grants from the Lupus Foundation of America and the Lupus Research Institute. JSW, PYL, MJD, and KKC were NIH T32 trainees (AR007603, DK07518, and GM08431).

The authors thank P. Chen, T. Barker, H. Zhuang, S. Han, M. Satoh, and L. Morel for technical expertise, reagents, and helpful discussions. The work was supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Malcolm Randall VA Medical Center, Gainesville, FL.

Abbreviations used

- TMPD

tetramethylpentadecane

- EBD

Evans Blue dye

- SDF-1

stromal derived factor 1

- ASC

antibody secreting cells

- PC

plasma cells

- PB

plasmablasts

- BM

bone marrow

References

- 1.Aloisi F, Pujol-Borrell R. Lymphoid neogenesis in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:205–217. doi: 10.1038/nri1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gause A, Gundlach K, Zdichavsky M, Jacobs G, Koch B, Hopf T, Pfreundschuh M. The B lymphocyte in rheumatoid arthritis: analysis of rearranged V kappa genes from B cells infiltrating the synovial membrane. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2775–2782. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830251010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barone F, Bombardieri M, Manzo A, Blades MC, Morgan PR, Challacombe SJ, Valesini G, Pitzalis C. Association of CXCL13 and CCL21 expression with the progressive organization of lymphoid-like structures in Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1773–1784. doi: 10.1002/art.21062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sims GP, Shiono H, Willcox N, Stott DI. Somatic hypermutation and selection of B cells in thymic germinal centers responding to acetylcholine receptor in myasthenia gravis. J Immunol. 2001;167:1935–1944. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kratz A, Campos-Neto A, Hanson MS, Ruddle NH. Chronic inflammation caused by lymphotoxin is lymphoid neogenesis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1461–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Satoh M, Reeves WH. Induction of lupus-associated autoantibodies in BALB/c mice by intraperitoneal injection of pristane. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2341–2346. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.6.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh M, Kumar A, Kanwar YS, Reeves WH. Anti-nuclear antibody production and immune-complex glomerulonephritis in BALB/c mice treated with pristane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10934–10938. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.24.10934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nacionales DC, Weinstein JS, Yan XJ, Albesiano E, Lee PY, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Lyons R, Satoh M, Chiorazzi N, Reeves WH. B cell proliferation, somatic hypermutation, class switch recombination, and autoantibody production in ectopic lymphoid tissue in murine lupus. J Immunol. 2009;182:4226–4236. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0800771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee PY, Li Y, Kumagai Y, Xu Y, Weinstein JS, Kellner ES, Nacionales DC, Butfiloski EJ, van Rooijen N, Akira S, Sobel ES, Satoh M, Reeves WH. Type I interferon modulates monocyte recruitment and maturation in chronic inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2009;175:2023–2033. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nacionales DC, Kelly KM, Lee PY, Zhuang H, Li Y, Weinstein JS, Sobel E, Kuroda Y, Akaogi J, Satoh M, Reeves WH. Type I interferon production by tertiary lymphoid tissue developing in response to 2,6,10,14-tetramethyl-pentadecane (pristane) Am J Pathol. 2006;168:1227–1240. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinstein JS, Nacionales DC, Lee PY, Kelly-Scumpia KM, Yan XJ, Scumpia PO, Vale-Cruz DS, Sobel E, Satoh M, Chiorazzi N, Reeves WH. Colocalization of antigen-specific B and T cells within ectopic lymphoid tissue following immunization with exogenous antigen. J Immunol. 2008;181:3259–3267. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R. Humoral immunity due to long-lived plasma cells. Immunity. 1998;8:363–372. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ochsenbein AF, Pinschewer DD, Sierro S, Horvath E, Hengartner H, Zinkernagel RM. Protective long-term antibody memory by antigen-driven and T help-dependent differentiation of long-lived memory B cells to short-lived plasma cells independent of secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13263–13268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230417497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHeyzer-Williams LJ, McHeyzer-Williams MG. Antigen-specific memory B cell development. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:487–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aiba Y, Kometani K, Hamadate M, Moriyama S, Sakaue-Sawano A, Tomura M, Luche H, Fehling HJ, Casellas R, Kanagawa O, Miyawaki A, Kurosaki T. Preferential localization of IgG memory B cells adjacent to contracted germinal centers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:12192–12197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richard K, Pierce SK, Song W. The agonists of TLR4 and 9 are sufficient to activate memory B cells to differentiate into plasma cells in vitro but not in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:1746–1752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.3.1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernasconi NL, Onai N, Lanzavecchia A. A role for Toll-like receptors in acquired immunity: up-regulation of TLR9 by BCR triggering in naive B cells and constitutive expression in memory B cells. Blood. 2003;101:4500–4504. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukacs NW, Berlin A, Schols D, Skerlj RT, Bridger GJ. AMD3100, a CxCR4 antagonist, attenuates allergic lung inflammation and airway hyperreactivity. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1353–1360. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62562-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tokoyoda K, Zehentmeier S, Hegazy AN, Albrecht I, Grun JR, Lohning M, Radbruch A. Professional memory CD4+ T lymphocytes preferentially reside and rest in the bone marrow. Immunity. 2009;30:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee PY, Weinstein JS, Nacionales DC, Scumpia PO, Li Y, Butfiloski E, van Rooijen N, Moldawer L, Satoh M, Reeves WH. A novel Type I IFN-producing cell subset in murine lupus. J Immunol. 2008;180:5101–5108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luther SA, Tang HL, Hyman PL, Farr AG, Cyster JG. Coexpression of the chemokines ELC and SLC by T zone stromal cells and deletion of the ELC gene in the plt/plt mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:12694–12699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.23.12694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.O’Garra A, Vieira P. Regulatory T cells and mechanisms of immune system control. Nature Med. 2004;10:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nm0804-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richards HB, Satoh M, Jennette JC, Croker BP, Yoshida H, Reeves WH. Interferon-gamma is required for lupus nephritis in mice treated with the hydrocarbon oil pristane. Kidney Int. 2001;60:2173–2180. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieira P, Rajewsky K. The half-lives of serum immunoglobulins in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:313–316. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830180221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Richards HB, Satoh M, Jennette JC, Okano T, Kanwar YS, Reeves WH. Disparate T cell requirements of two subsets of lupus-specific autoantibodies in pristane-treated mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;115:547–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00825.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gronowicz ES, Doss C, Assisi F, Vitetta ES, Coffman RL, Strober S. Surface Ig isotypes on cells responding to lipopolysaccharide by IgM and IgG secretion. Journal of immunology. 1979;123:2049–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothman P, Lutzker S, Gorham B, Stewart V, Coffman R, Alt FW. Structure and expression of germline immunoglobulin gamma 3 heavy chain gene transcripts: implications for mitogen and lymphokine directed class-switching. International immunology. 1990;2:621–627. doi: 10.1093/intimm/2.7.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siebenkotten G, Esser C, Wabl M, Radbruch A. The murine IgG1/IgE class switch program. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:1827–1834. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manz RA, Thiel A, Radbruch A. Lifetime of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature. 1997;388:133–134. doi: 10.1038/40540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamphuis E, Junt T, Waibler Z, Forster R, Kalinke U. Type I interferons directly regulate lymphocyte recirculation and cause transient blood lymphopenia. Blood. 2006;108:3253–3261. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-027599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser AE, Debes GF, Arce S, Cassese G, Hamann A, Radbruch A, Manz RA. Chemotactic responsiveness toward ligands for CXCR3 and CXCR4 is regulated on plasma blasts during the time course of a memory immune response. J Immunol. 2002;169:1277–1282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hargreaves DC, Hyman PL, Lu TT, Ngo VN, Bidgol A, Suzuki G, Zou YR, Littman DR, Cyster JG. A coordinated change in chemokine responsiveness guides plasma cell movements. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;194:45–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Omatsu Y, Sugiyama T, Kohara H, Kondoh G, Fujii N, Kohno K, Nagasawa T. The Essential Functions of Adipo-osteogenic Progenitors as the Hematopoietic Stem and Progenitor Cell Niche. Immunity. 2010;33:387–399. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Belnoue E, Tougne C, Rochat AF, Lambert PH, Pinschewer DD, Siegrist CA. Homing and Adhesion Patterns Determine the Cellular Composition of the Bone Marrow Plasma Cell Niche. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;188:1283–1291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang A, Fairhurst AM, Tus K, Subramanian S, Liu Y, Lin F, Igarashi P, Zhou XJ, Batteux F, Wong D, Wakeland EK, Mohan C. CXCR4/CXCL12 hyperexpression plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of lupus. J Immunol. 2009;182:4448–4458. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drayton DL, Liao S, Mounzer RH, Ruddle NH. Lymphoid organ development: from ontogeny to neogenesis. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:344–353. doi: 10.1038/ni1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rendt KE, Barry TS, Jones DM, Richter CB, McCachren SS, Haynes BF. Engraftment of human synovium into severe combined immune deficient mice. Migration of human peripheral blood T cells to engrafted human synovium and to mouse lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1993;151:7324–7336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Ectopic germinal center formation in rheumatoid synovitis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;987:140–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb06042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humby F, Bombardieri M, Manzo A, Kelly S, Blades MC, Kirkham B, Spencer J, Pitzalis C. Ectopic Lymphoid Structures Support Ongoing Production of Class-Switched Autoantibodies in Rheumatoid Synovium. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0060001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiow LR, Rosen DB, Brdickova N, Xu Y, An J, Lanier LL, Cyster JG, Matloubian M. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-[alpha]/[beta] to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature04606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu Y, Lee PY, Li Y, Liu C, Zhuang H, Han S, Nacionales DC, Weinstein J, Mathews CE, Moldawer LL, Li SW, Satoh M, Yang LJ, Reeves WH. Pleiotropic IFN-Dependent and -Independent Effects of IRF5 on the Pathogenesis of Experimental Lupus. The Journal of Immunology. 2012;188:4113–4121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee PY, Weinstein JS, Nacionales DC, Scumpia PO, Li Y, Butfiloski E, Van Rooijen N, Moldawer L, Satoh M, Reeves WH. A novel type I IFN-producing cell subset in murine lupus. J Immunol. 2008;180:5101–5108. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tesch GH, Maifert S, Schwarting A, Rollins BJ, Kelley VR. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1-dependent leukocytic infiltrates are responsible for autoimmune disease in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1813–1824. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.12.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Clercq E. The AMD3100 story: The path to the discovery of a stem cell mobilizer (Mozobil) Biochemical Pharmacology. 2009;77:1655–1664. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Azab AK, Runnels JM, Pitsillides C, Moreau AS, Azab F, Leleu X, Jia X, Wright R, Ospina B, Carlson AL, Alt C, Burwick N, Roccaro AM, Ngo HT, Farag M, Melhem MR, Sacco A, Munshi NC, Hideshima T, Rollins BJ, Anderson KC, Kung AL, Lin CP, Ghobrial IM. CXCR4 inhibitor AMD3100 disrupts the interaction of multiple myeloma cells with the bone marrow microenvironment and enhances their sensitivity to therapy. Blood. 2009;113:4341–4351. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-186668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliveira AM, Maria DA, Metzger M, Linardi C, Giorgi RR, Moura F, Martinez GA, Bydlowski SP, Novak EM. Thalidomide treatment down-regulates SDF-1α and CXCR4 expression in multiple myeloma patients. Leukemia Research. 2009;33:970–973. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inamine A, Takahashi Y, Baba N, Miyake K, Tokuhisa T, Takemori T, Abe R. Two waves of memory B-cell generation in the primary immune response. Int Immunol. 2005;17:581–589. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199–2202. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Herlands RA, Christensen SR, Sweet RA, Hershberg U, Shlomchik MJ. T Cell-Independent and Toll-like Receptor-Dependent Antigen-Driven Activation of Autoreactive B Cells. Immunity. 2008;29:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muehlinghaus G, Cigliano L, Huehn S, Peddinghaus A, Leyendeckers H, Hauser AE, Hiepe F, Radbruch A, Arce S, Manz RA. Regulation of CXCR3 and CXCR4 expression during terminal differentiation of memory B cells into plasma cells. Blood. 2005;105:3965–3971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-2992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Benson MJ, Dillon SR, Castigli E, Geha RS, Xu S, Lam KP, Noelle RJ. Cutting edge: the dependence of plasma cells and independence of memory B cells on BAFF and APRIL. J Immunol. 2008;180:3655–3659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elgueta R, De Vries VC, Noelle RJ. The immortality of humoral immunity. Immunological Reviews. 2010;236:139–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimoda M, Mmanywa F, Joshi SK, Li T, Miyake K, Pihkala J, Abbas JA, Koni PA. Conditional Ablation of MHC-II Suggests an Indirect Role for MHC-II in Regulatory CD4 T Cell Maintenance. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;176:6503–6511. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dogan I, Bertocci B, Vilmont V, Delbos F, Megret J, Storck S, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effectorfunctions. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoshida T, Mei H, Dörner T, Hiepe F, Radbruch A, Fillatreau S, Hoyer BF. Memory B and memory plasma cells. Immunological Reviews. 2010;237:117–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00938.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoyer BF, Moser K, Hauser AE, Peddinghaus A, Voigt C, Eilat D, Radbruch A, Hiepe F, Manz RA. Short-lived plasmablasts and long-lived plasma cells contribute to chronic humoral autoimmunity in NZB/W mice. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1577–1584. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tokoyoda K, Zehentmeier S, Hegazy AN, Albrecht I, Grün JR, Löhning M, Radbruch A. Professional Memory CD4+ T Lymphocytes Preferentially Reside and Rest in the Bone Marrow. Immunity. 2009;30:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moser K, Tokoyoda K, Radbruch A, MacLennan I, Manz RA. Stromal niches, plasma cell differentiation and survival. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:265–270. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ueda Y, Kondo M, Kelsoe G. Inflammation and the reciprocal production of granulocytes and lymphocytes in bone marrow. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1771–1780. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ueda Y, Yang K, Foster SJ, Kondo M, Kelsoe G. Inflammation Controls B Lymphopoiesis by Regulating Chemokine CXCL12 Expression. J Exp Med. 2004;199:47–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim HK, De La Luz Sierra M, Williams CK, Gulino AV, Tosato G. G-CSF down-regulation of CXCR4 expression identified as a mechanism for mobilization of myeloid cells. Blood. 2006;108:812–820. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.