Abstract

Background and Purpose

Strong implications in major neurological diseases make the neuronal α4β2 nicotinic ACh receptor (nAChR) a highly interesting drug target. In this study, we present a detailed electrophysiological characterization of NS9283, a potent positive allosteric modulator acting selectively at 3α:2β stoichiometry of α2* and α4* nAChRs.

Experimental Approach

The whole-cell patch-clamp technique equipped with an ultra-fast drug application system was used to perform electrophysiological characterization of NS9283 modulatory actions on human α4β2 nAChRs stably expressed in HEK293 cells (HEK293-hα4β2).

Key Results

NS9283 was demonstrated to increase the potency of ACh-evoked currents in HEK293-hα4β2 cells by left-shifting the concentration–response curve ∼60-fold. Interestingly, this modulation did not significantly alter maximal efficacy levels of ACh. Further, NS9283 did not affect the rate of desensitization of ACh-evoked currents, was incapable of reactivating desensitized receptors and only moderately slowed recovery from desensitization. However, NS9283 strongly decreased the rate of deactivation kinetics and also modestly decreased the rate of activation. This resulted in a left-shift of the ACh window current of (α4)3(β2)2 nAChRs in the presence of NS9283.

Conclusions and Implications

This study demonstrates that NS9283 increases responsiveness of human (α4)3(β2)2 nAChR to ACh with no change in maximum efficacy. We propose that this potentiation is due to a significant slowing of deactivation kinetics. In summary, the mechanism of action of NS9283 bears high resemblance to that of benzodiazepines at the GABAA receptor and to our knowledge, NS9283 constitutes the first nAChR compound of this class.

Keywords: nicotinic ACh receptor, NS9283, α4β2, positive allosteric modulator, patch-clamp

Introduction

Disturbance of cholinergic transmission is implicated in a series of neurological conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Potter et al., 2006; Wilens and Decker, 2007), schizophrenia (Radek et al., 2010), Parkinson's disease (Perez et al., 2010) and Alzheimer's disease (Haydar and Dunlop, 2010). This therapeutic potential founds the basis for an ongoing search for ligands selectively targeting various nAChR subtypes. Among these is the α4β2 nAChR, which due to its abundant expression in the CNS (Gotti et al., 2006) is believed to be a key player in neuronal synaptic communication.

The α4β2 nAChR exists in two functional stoichiometries determined by the α4:β2 subunit ratio. The (α4)3(β2)2 subtype is characterized by low sensitivity to the endogenous agonist, ACh, compared with the high-sensitive subtype, (α4)2(β2)3, the two receptors exhibiting functional ACh EC50 values of ∼100 and ∼1 μM, respectively (Nelson et al., 2003; Moroni et al., 2006; Harpsøe et al., 2011; Mazzaferro et al., 2011). The observed difference in ACh sensitivity between the two subtypes has recently been shown to arise from the presence of a third binding site for ACh in the (α4)3(β2)2 subtype (Harpsøe et al., 2011; Mazzaferro et al., 2011). Several studies indicate the presence of distinct 2α:3β and 3α:2β receptor populations in the CNS (Marks et al., 2007; Gotti et al., 2008; Timmermann et al., 2012), and thus the two α4β2 subtypes present another layer of complexity to the heterogeneous family of neuronal nAChRs.

Several agonists with activity at the α4β2 nAChR have been identified over the years (Sullivan et al., 1997; Coe et al., 2005). The α4β2 partial agonist varenicline has been approved in several countries as an aid in smoking cessation and in the treatment of nicotine addiction (Coe et al., 2005), and various α4β2 agonists have been tested in clinical studies for the treatment of ADHD (Wilens et al., 1999; 2011; 2006; Apostol et al., 2012). However, within the field of drug development targeting nAChRs, it has been proposed that positive allosteric modulators (PAMs; Sala et al., 2005; Albrecht et al., 2008; Pandya and Yakel, 2011; Timmermann et al., 2012) possess several pharmacological advantages over agonists. These include higher subtype selectivity (Pandya and Yakel, 2011) as well as maintenance of endogenous spatiotemporal patterns of cholinergic signalling (Sarter and Bruno, 1997) due to lack of desensitizing effects as observed with agonists (Giniatullin et al., 2005). At the present time, the number of published PAMs targeting the α4β2 nAChR is rather limited (Sala et al., 2005; Albrecht et al., 2008; Pandya and Yakel, 2011; Timmermann et al., 2012).

The compound NS9283, a potent PAM of α4β2 nAChRs, has displayed pro-cognitive (Timmermann et al., 2012) and analgesic effects (Lee et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011; Rode et al., 2012) in a wide range of in vivo assays. Interestingly, two-electrode voltage-clamp recordings in Xenopus laevis oocytes have revealed that NS9283 selectively increases ACh potency at the 3α:2β receptors while it does not modulate current conducted by the 2α:3β receptors (Timmermann et al., 2012). While these data describe the overall modulatory effects of NS9283, they do not investigate the fundamental mechanistic actions of the compound at the nAChR current waveform level.

In the present study, the mechanism behind the modulatory effect of NS9283 on human α4β2 nAChR currents was studied in mammalian cells using whole-cell patch-clamp techniques in a setup equipped with an ultra-fast application system. The study reveals that the main effect of NS9283 is selective modulation of receptor deactivation kinetics, resulting in an increased ACh potency and a left-shift of the ACh window current. This highlights NS9283 as a unique nicotinic PAM with mechanistic properties resembling those of benzodiazepines at the GABAA receptor, suggesting a therapeutic potential of positive allosteric modulation of 3α:2β α4β2 nAChRs.

Methods

Materials

All chemicals used in the study, including ACh and ACh esterase (AChE), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Brøndby, Denmark), except NS9283 (3-[3-(3-pyridyl)-1,2,4-oxadiazol-5-yl] benzonitrile), which was synthesized at NeuroSearch A/S. NS9283 was initially dissolved in DMSO and diluted to final concentrations thereof, where DMSO concentrations were kept below 0.1% in all experiments. Drug and molecular target nomenclature conforms to the British Journal of Pharmacology Guide to Receptors and Channels (Alexander et al., 2011).

Cell culture

HEK293 cells (CRL-1573, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA) stably expressing human α4β2 nAChRs were cultured as described in (Timmermann et al., 2012). Briefly, cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in DMEM (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with Gibco® 10% FBS and zeocin (100 μg·mL−1) (Invitrogen, Tåstrup, Denmark).

Patch-clamp electrophysiology

The HEK293-hα4β2 cells used for the patch-clamp experiments were grown on poly-D-lysine coated glass coverslips. The coverslips were placed in a recording chamber fixed at the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus, Ballerup, Denmark). During the experiments, cells were perfused with an extracellular buffer containing: 140 mM NaCl, 10 mM HEPES, 4 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4, adjusted with NaOH). Patch pipettes, made from borosilicate capillary tubes, were pulled using a horizontal puller (Zeitz-Instrument, Munich, Germany) and backfilled with intracellular buffer containing: 120 mM KCl, 31 mM KOH, 10 mM EGTA, 10 mM HEPES, 1.785 MgCl2 (pH 7.4, adjusted with KOH). Pipette resistances were in the range of 1.5–3 MΩ when submerged in extracellular buffer. Patch-clamp experiments were performed in whole-cell configuration at 21–25°C. Data were sampled at minimum 4 kHz with Pulse software (v8.80) controlling an EPC-9 amplifier (HEKA, Lambrecht, Germany) and low-pass filtered at 2.9 kHz. Cells were held at a holding potential of −60 mV throughout experiments. Capacitive currents and series resistances were determined upon establishment of whole-cell configuration. Series resistance was compensated by 80%. Only cells with series resistance <10 MΩ were accepted for data analysis. Fast application of the drugs was managed using a double-barrelled micropipette made from a theta-glass capillary (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) with a tip diameter of ∼50–100 μm. Using a micromanipulator system (Eppendorf Nordic, Hørsholm, Denmark) the application micropipette was positioned in the near vicinity of the patch-clamped cell under visual guidance. This system allows control of the environment of the cell, which can be rapidly exchanged upon a fast lateral step between the buffers (with/without drug) flowing from the two barrels, controlled by a piezo-ceramic device (Burleigh Instruments, Fishers, NY, USA). Solution exchange time of the application system was estimated by recording the open tip current caused by differences in liquid junction potentials when stepping to a solution of reduced ionic strength. The 10–90% rise time for solution exchange was ∼600–800 μs.

For the experiments, the extracellular buffer supplemented with ACh in various concentrations (10 nM to 10 mM) was applied onto the cells. To prevent leftover of ACh in the application tubing when going from higher to lower ACh concentrations, the tubings were washed with a 5 unit·mL−1 AChE solution. In the majority of experiments with NS9283, a concentration of 10 μM of the compound was added to the extracellular buffer. To ensure full recovery of the receptors from desensitization, exposure of the cells to ACh (with or without NS9283) was separated by wash steps for 60–120 s. Specific protocol details are described in the Results section and in figure legends. All solutions were prepared on the day of the experiment from stock solutions.

Data analysis and statistics

In the patch-clamp concentration–response studies, currents were quantified by measuring peak current amplitude. Values were normalized to the peak current amplitude of a control response evoked by a saturating concentration of 3 mM ACh as indicated for each experiment. Normalized peak current amplitudes were graphically depicted and fitted to the monophasic Hill equation:

or biphasic Hill equation:

|

(where Inormalized is the current response; Bottom and Emax is minimum and maximum of the fit, respectively; Frac is the proportion of maximal response due to the more potent phase; and X is drug concentration) using GraphPad Prism (v4.03, GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). If nothing else is stated constraints for the Hill equation were: Bottom = 0, Hill coefficient = 1. In the kinetic studies curve fitting of current traces with single and double exponential functions was performed using GraphPad Prism to obtain estimates of deactivation and desensitization time constants. A double exponential function was used in desensitization and desensitization recovery experiments. Activation kinetics were quantified by determining maximum slope in the rising phase of a current response and calculated as the slope of a linear regression line through 13 consecutive data points. Window currents were quantified by calculating AUC. Statistical analysis was mainly performed with Student's t-test using GraphPad Prism (α = 0.05). The GraphPad Prism best-model F-test was used to evaluate whether a given data set was better represented with one of two models, see the Results section for details. Results are written as F-values (DFn, DFd). Where applicable, statistical errors of averaged data are given as mean ± SEM. values with the number of determinations (n).

Results

In this study, modulatory effects of NS9283 on ACh-evoked signalling through α4β2 nAChRs were investigated using the whole-cell patch-clamp technology. For this we used a HEK293 cell line stably expressing human α4β2 nAChR (Timmermann et al., 2012).

NS9283 increases potency, but not efficacy of ACh at the human α4β2 nAChR

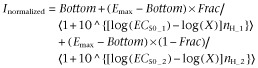

In whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, application of 30 μM ACh at HEK293-hα4β2 cells elicited inward current responses with a distinct peak amplitude followed by current decay (Figure 1A). Application of NS9283 (10 μM) alone did not elicit any current response whereas preincubating cells with NS9283 for 90 s resulted in significant potentiation of currents elicited by non-saturating ACh concentrations when co-applied with NS9283 (Figure 1A). These modulatory effects of NS9283 were investigated over a wide range of ACh concentrations (Figure 1B). The resulting concentration–response relationships (CRRs) were obtained by fitting data to the Hill equation by non-linear regression, yielding agonist potencies and efficacies (with 95% CIs) in the absence and presence of NS9283. The best-model F-test revealed that the ACh CRR was better represented by a biphasic than a monophasic Hill fit [P < 0.05, F = 3.639 (2,76) ]: ACh: EC50_1 = 0.74 μM (0.01–44.7), EC50_2 = 121.6 μM (65.3–225.9), Frac = 0.10 and Emax = 96% (88–104). These EC50 values and fraction between the two components closely resembles that observed for a uniform population of 3α:2β stoichiometry α4β2 receptors reported previously (Harpsøe et al., 2011) indicating that the HEK cell line predominantly, and potentially exclusively, expresses this receptor stoichiometry. Interestingly, in the presence of NS9283, the ACh CRR was better represented by a monophasic Hill equation: ACh + NS9283: EC50 = 2.0 μM (1.1–3.8) and Emax = 105% (92–119) (Figure 1B). The EC50 value in presence of 10 μM NS9283 is thus comparable with EC50_1 but ∼60-fold smaller than EC50_2. The substantial overlap of Emax 95% CIs obtained with and without NS9283 demonstrates that NS9283 does not alter ACh efficacy at α4β2 nAChRs. No significant difference was found between Hill equation fits with unrestricted and restricted Emax = 100 [ACh: P = 0.33, F = 0.94 (1,76)], suggesting negligible current rundown.

Figure 1.

NS9283 increases ACh potency in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments in HEK293-hα4β2 cells. Cells were voltage-clamped at −60 mV and currents recorded in whole-cell mode. Drugs were applied for 1 s using an ultra-fast piezo-ceramic device. Each application step was separated by 60–120 s of wash with standard extracellular buffer. All experiments with NS9283 included a ∼90 s preincubation period with NS9283 before ACh application. (A) Representative current traces of a voltage-clamped HEK293-hα4β2 cell elicited by ACh (full bar), NS9283 (dotted bar) and ACh in presence of NS9283. (B) CRR for ACh in the absence and presence of NS9283. Cells were exposed to ACh for 1 s, and the average peak current amplitude from two to three responses was calculated. Each ACh response was normalized with respect to the peak amplitude of the average of two to three responses elicited by a saturating ACh concentration (3 mM) prior to the test application. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. values of 4–12 cells. Mono and biphasic Hill equations were fitted to the data points in presence and absence of NS9283, respectively. (C) CRR for NS9283. Cells were preincubated with varying concentrations of NS9283 and exposed to 10 μM ACh + NS9283 for 1 s. The average peak current amplitude from two to three responses was calculated and normalized as in B). Each data point represents the mean ± SEM. values of 5–7 cells. For illustrative purposes, the data point of 10 μM ACh in the absence of NS9283 is shown (full circle). A monophasic Hill equation was fitted to the data points.

Finally, in order to determine the potency of NS9283 as a α4β2 PAM, a CRR of NS9283 was established in patch-clamp experiments by preincubating HEK293-hα4β2 cells with different concentrations of NS9283 and applying 10 μM ACh + NS9283 in the same concentration for 1 s. A monophasic Hill equation could be fitted to the resulting data points, yielding an EC50 value of 4.0 μM (Figure 1C). It should be mentioned that here, the ‘Bottom’ of the Hill equation was restricted to the normalized current amplitude of 10 μM ACh in the absence of NS9283, whereas ‘Top’ was unrestricted. This EC50 value resembles what has previously been established for NS9283 (Timmermann et al., 2012). Based on these observations, a concentration of 10 μM NS9283 was used for all further experiments in this study.

NS9283 has no effect on ACh-induced desensitization

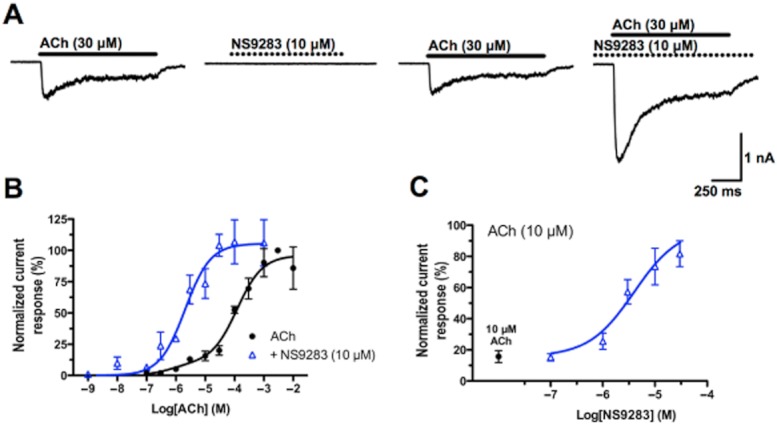

The influence of NS9283 on α4β2 desensitization kinetics was addressed by fitting exponential functions to the current decay in presence of ACh to obtain estimates of desensitization time constants, τdesens. In order to eliminate possible influence of current amplitude on estimated desensitization parameters, currents were evoked with 1 mM ACh [∼EC100 both in the absence and presence of NS9283 (Figure 1B)]. ACh application time was 10 s, thereby allowing the current to reach steady state. Both in the absence and presence of NS9283 double exponential functions provided better current trace fits compared with single exponential functions (P < 0.0001, F-test, data not shown). Representative traces of currents evoked with 1 mM ACh for 10 s in the absence and presence of NS9283 are given in Figure 2A. As seen in Figure 2B, NS9283 did not significantly affect any of the two time constants of ACh-evoked current decay (ACh: τdesens,1 = 67 ± 10 ms, ACh + NS9283: τdesens,1 = 66 ± 8 ms, P = 0.944; ACh: τdesens,2 = 1421 ± 188 ms, ACh + NS9283: τdesens,2 = 1469 ± 424 ms, P = 0.923; unpaired t-test, n = 7–8). Furthermore, NS9283 did not affect the fractions of the current decay represented by the fast and the slow component (ACh: Span1 = 88 ± 1%, ACh + NS9283: Span1 = 89 ± 1%, P = 0.449; ACh: Span2 = 12 ± 1%, ACh + NS9283: Span2 = 11 ± 1%, P = 0.449; unpaired t-test, n = 7–8) or the estimated current plateau (ACh: Plateau = 1.8 ± 0.3%, ACh + NS9283: Plateau = 1.7 ± 0.6%, P = 0.85; unpaired t-test, n = 7–8).

Figure 2.

NS9283 does not affect ACh-induced desensitization of α4β2 nAChRs. (A) Representative current responses to 10 s applications of 1 mM ACh at HEK293-hα4β2 cells in the absence and presence of NS9283. Exponential fits (dashed lines) are made to the current decay in presence of ACh (from peak amplitude to end of 10 s application). The individual current traces are normalized to their respective peak amplitude. (B) Time constants of the fast and slow components of desensitization (τdesens,1 and τdesens,2, respectively) in the absence and presence of NS9283. Time constants of desensitization were obtained by double exponential curve fitting of the decaying phase of current traces (Figure 2A). Desensitization parameters were measured two to three times for each cell and averaged. Each data point represents the mean ± SEM values of 7–8 cells.

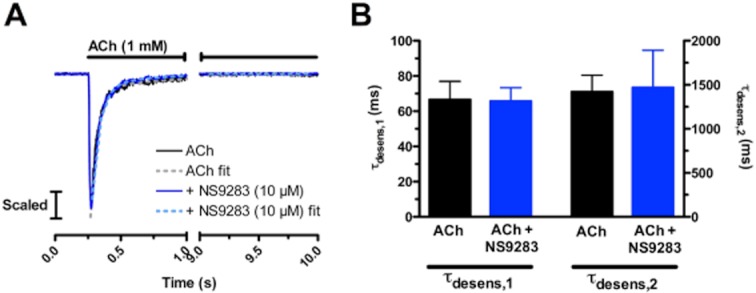

NS9283 reduces the rate of recovery from desensitization

The effect of NS9283 on the recovery of α4β2 nAChRs from ACh-induced desensitization was addressed by measuring paired-pulse responses. This was carried out by applying two pulses of 1 mM ACh (1 s) separated by an interpulse interval of varying lengths (from 0.25 s to 128 s) with NS9283 absent or present during the pulse and interpulse interval. An ACh concentration of 1 mM was chosen for this experiment in order to compare recovery from desensitization at the same EC value (∼EC100). As can be seen from Figure 3A, the amplitude of the second response was gradually increased with the duration of the interpulse interval, reflecting recovery from desensitization. The average recovery (normalized to the initial response to ACh) in the absence and presence of NS9283 over a period of 4 s is shown in Figure 3B (n = 6–17 cells). Full recovery of the receptor was obtained within 32 and 128 s in the absence and presence of NS9283, respectively (data not shown). The time-course of recovery could be described with a double exponential function, where the time constants of fast and slow recovery were 0.37 and 12.8 s in the absence of NS9283 and 0.75 and 67.3 s in presence of NS9283. In average, the amplitude of the second pulse was 18% lower in presence of NS9283 than in the absence of the PAM within the first 32 s (P < 0.001, paired t-test). This effect was more pronounced at shorter interpulse intervals (0.25 s: 51%, 0.5 s: 29%, 1 s: 20%, 2 s: 12%, 4 s: 7%, 8 s: 7%, 16 s: 9%, 32 s: 12%).

Figure 3.

NS9283 reduces the rate of recovery of α4β2 nAChR from desensitization. (A) Representative current responses following paired-pulse applications (1 s) of ACh in presence of NS9283. The solid line indicates the first ACh pulse and the arrows indicate the time points for the second pulses. The interpulse interval is indicated at the top and measured as the interval from removal of ACh of the first application to the beginning of the second application. Each paired-pulse application is separated by a wash step with standard extracellular buffer (ACh alone: 60 s, ACh + NS9283: 120 s). The time course of recovery could be described by fitting a double exponential curve to the data points (dashed line). (B) Time course of recovery of α4β2 nAChR from desensitization in the absence and presence of NS9283. The amplitude of the second pulse is normalized to the amplitude of the first. Each data point represents n = 6–9 cells, and error bars indicate SEM values. The data points were fitted with double exponential functions.

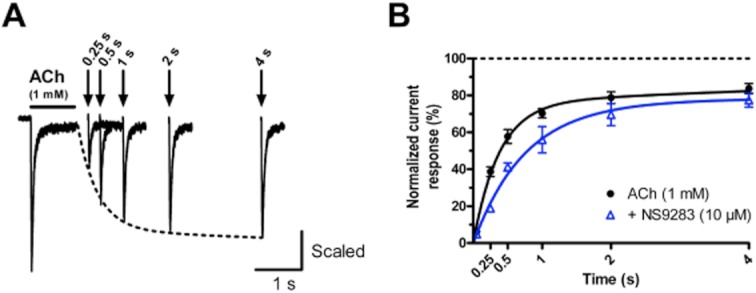

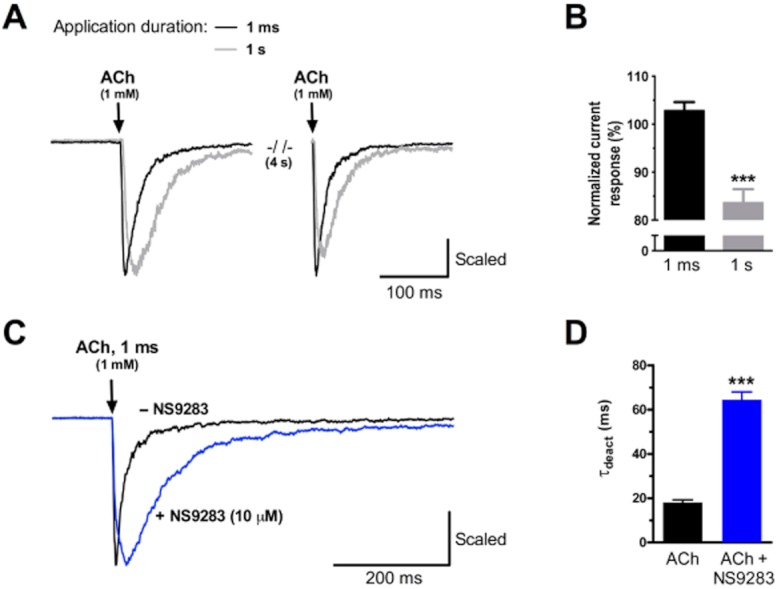

NS9283 slows the rate of deactivation

Deactivation is defined as the current decay in the absence of agonist. When evaluating deactivation kinetics, it is important to ensure that current decay primarily reflects deactivation and not desensitization. In practical terms, this was accomplished by comparing two ultra-short 1 ms pulses of 1 mM ACh separated by a brief wash period (4 s). Assuming that the current decay observed following the first pulse solely represents transition from an open-bound to a closed-unbound receptor state, all receptors should theoretically be available for re-activation at the second pulse. When using this ultra-short pulsing regime, peak currents elicited by ACh was fully recovered from first firing after the brief wash period as seen in Figure 4A. Calculating the ratio between the amplitudes of the first and the second peak reveals no significant difference (103 ± 2%, P = 0.184, paired t-test, n = 5) (Figure 4B). In contrast, a similar experiment carried out using a longer 1 s ACh application duration (Figure 4A) showed a significant reduction in amplitude of the second peak with accordingly diminished peak ratio (84 ± 3%, P < 0.001, paired t-test, n = 7) (Figure 4B). These data indicate that 1 ms long applications do not cause significant desensitization and, hence, obtained time constants from such experiments can be used as an approximated measure of deactivation kinetics.

Figure 4.

NS9283 significantly reduces the rate of deactivation of α4β2 nAChRs. (A) Representative current responses to two ACh pulses of 1 ms and 1 s duration. The two pulses were separated by a 4 s wash period. Current traces have been normalized to the peak amplitude of the first pulse. (B) Average current response of the second of two 1 mM ACh pulses normalized to the peak amplitude of the first pulse. ACh was applied for 1 ms (n = 5) and 1 s (n = 7). ***P < 0.001, paired t-test. (C) Representative current responses to 1 ms application of ACh in the absence and presence of NS9283. Currents have been normalized to their respective peak amplitude. (D) Average time constants of deactivation (τdeact) of α4β2 nAChR in the absence and presence of NS9283 (n = 5). τdeact was obtained by single exponential curve fitting to current decay upon 1 ms application of 1 mM ACh (Figure 4B). Time constants of deactivation were measured two to three times for each cell and averaged. ***P < 0.001, paired t-test.

In Figure 4C, trace examples of ultra-short applications of a high concentration of ACh (1 mM) to HEK293-hα4β2 cells are depicted in the absence and presence of NS9283. It is clearly seen, that the current decay was substantially slower in presence of NS9283. Using the same approach as in the analysis of desensitization kinetics, a single exponential function was fitted to the current decay to obtain deactivation time constants, τdeact. As seen from Figure 4D, the presence of NS9283 significantly increased the deactivation time constant for the receptor from 18 ± 1.2 ms (ACh) to 65 ± 3.5 ms (ACh + NS9283) (P < 0.001, paired t-test, n = 5).

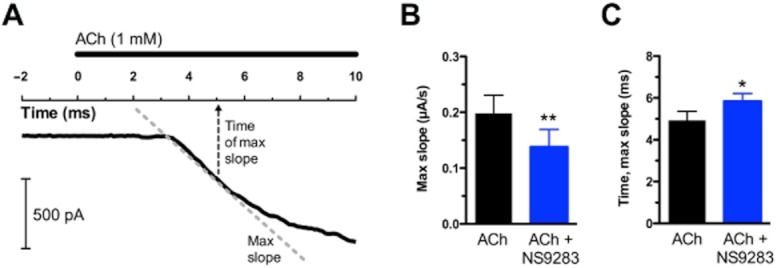

NS9283 has moderate effects on activation kinetics

In addition to desensitization and deactivation kinetics, effects of NS9283 on α4β2 nAChR activation kinetics were investigated. This was achieved by calculating the maximum slope during the current rising phase in response to a 1 s application of 1 mM ACh in absence or presence of NS9283 (Figure 5A). The presence of NS9283 significantly reduced the maximum slope of this current response (ACh: 0.20 ± 0.03 μA·s−1, ACh + NS9283: 0.14 ± 0.03 μA·s−1, P < 0.01, paired t-test, n = 7) (Figure 5B). Furthermore, the maximum slope occurred at a later stage (time to maximum slope after ACh application onset: ACh: 4.9 ± 0.4 ms, ACh + NS9283: 5.8 ± 0.4 ms, P < 0.05, paired t-test, n = 7) (Figure 5C). Although these effects are significant on a grand scale, they only result in moderate overall changes from application initiation until the time where maximal current is obtained as observed from Figure 5A.

Figure 5.

NS9283 modestly affects activation kinetics of α4β2 nAChRs. (A) Representative current trace. Time scale (ms) has been offset corrected to the ACh application. The dashed grey line indicates the maximum slope of the current response to ACh. The dashed arrow indicates the time of maximum slope. (B) Average maximum slope in the absence and presence of 10 μM NS9283 (n = 7). Maximum slope was calculated from the rising phase of current responses evoked by 1 s application of 1 mM ACh. **P < 0.01, paired t-test. (C) Average time to maximum slope after ACh application onset (1 mM) in the absence and presence of 10 μM NS9283 (n = 7). *P < 0.05, paired t-test.

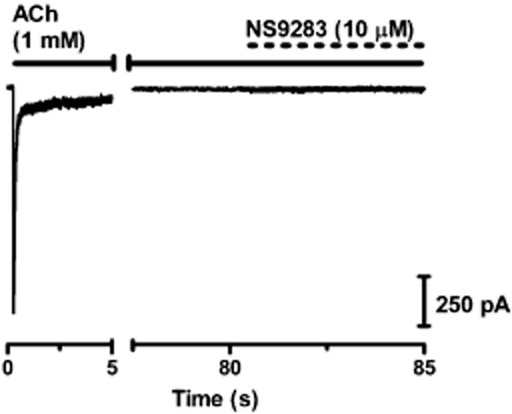

NS9283 cannot rescue α4β2 receptors from ACh-induced desensitization

Several PAMs of both α7 (Hurst et al., 2005; Gronlien et al., 2007; Malysz et al., 2009) and α4β2 nAChRs (Weltzin and Schulte, 2010) have been demonstrated capable of reactivating desensitized receptors, releasing them from a non-conducting state despite continued presence of an agonist. To investigate whether or not NS9283 was capable of this, HEK293-hα4β2 cells were exposed to 1 mM ACh for ∼90 s, after which NS9283 was co-applied with ACh for 5 s. No current response was observed in any of the recordings made (n = 5) (Figure 6). In similar experiments using 100 μM ACh (∼EC50), small and inconsistent responses were observed (∼10% of peak current amplitude in two of five cells, data not shown).

Figure 6.

NS9283 does not reactivate desensitized α4β2 nAChRs. Representative recording. Following long ACh exposure (∼90 s) HEK293-hα4β2 cells were exposed to NS9283 (5 s).

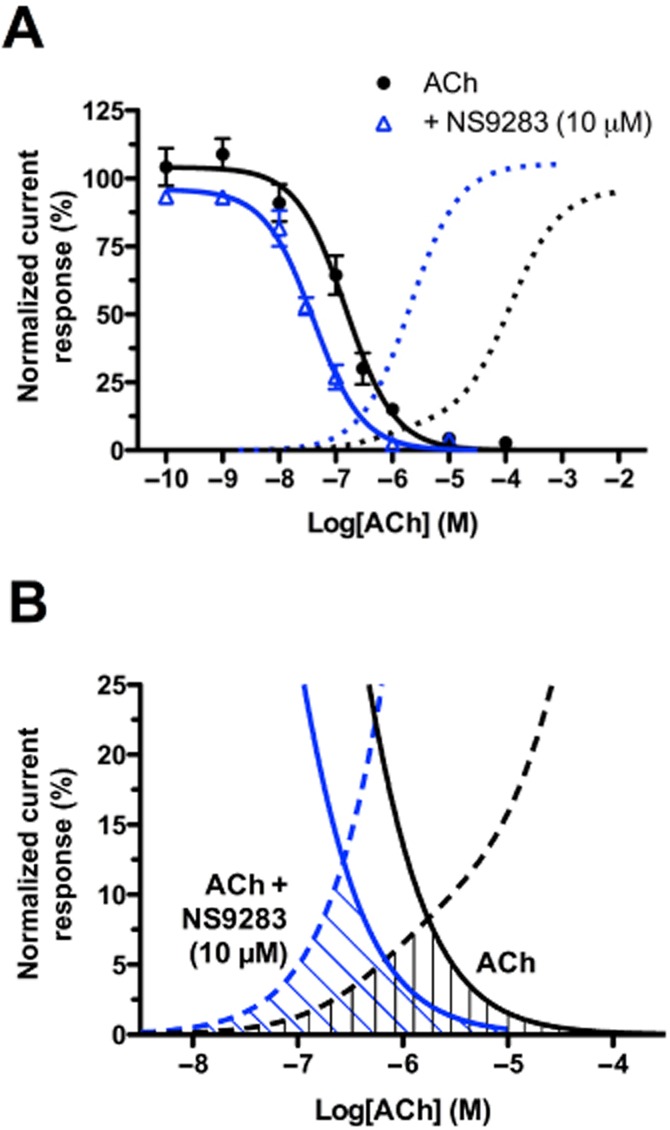

NS9283 left-shifts the ACh window current

The ‘window current’ of a ligand-gated ion channel describes an agonist concentration range in which a finite number of receptors can be recruited for activation despite the presence of a desensitizing agonist (Lester, 2004). To determine whether NS9283 affects α4β2 window currents, HEK293-hα4β2 cells were preincubated with different concentrations of ACh in absence and presence of NS9283 followed by a 1 mM ACh application (1 s). Based on the desensitization–reactivation experiments (Figure 6), the incubation step was set to 90 s and current responses were normalized to a 1 mM ACh response (1 s) recorded prior to the incubation period. This provides a measurement of the fraction of receptors that can be activated after incubation at each given ACh concentration. As expected, the incubations resulted in a concentration-dependent inhibition of the 1 mM ACh-elicited currents (Figure 7A). These CRRs could be fitted to the Hill equation, yielding the following IC50 values (with 95% confidence intervals): ACh: IC50 = 151 nM (100–228), ACh + NS9283: IC50 = 40 nM (31–53). Thus, NS9283 left-shifted the ACh desensitization curve by a factor of ∼4.

Figure 7.

NS9283 left-shifts the ACh window current at the α4β2 nAChR. (A) Desensitization curves for ACh in the absence and presence of NS9283. The desensitization curves were obtained from experiments where HEK293-hα4β2 cells were preincubated with varying concentrations of ACh for 90 s in the absence and presence of NS9283 and then exposed to 1 mM ACh or 1 mM ACh + NS9283, respectively. The evoked responses were normalized to a 1 mM ACh application recorded prior to the ACh incubation. Each data point represents the mean value ± SEM of 3–14 cells. The activation curves for ACh in the absence and presence of NS9283 are given in dotted lines (from Figure 1B). (B) Detail of Figure 7A: Window current of ACh in the absence and presence of NS9283.

As can be seen from Figure 7, the overlap of the activation and desensitization curves depicts a concentration range of desensitizing agonist where the receptor can still be activated: this concentration range is the window current. Close comparison of the window currents observed in the absence (area with black vertical lines) and presence of NS9283 (area with blue oblique lines) in Figure 7B indicates that the peak of the ACh window current occurs at ∼1.75 μM reaching a maximal response of ∼8% of the initial 1 mM ACh response, whereas the peak of the ACh window current in presence of NS9283 occurs at ∼250 nM and reaches a maximal response of ∼13% of the initial 1 mM ACh response. NS9283 did not appear to alter the ACh window current AUC as this was 1.2-fold larger in presence of NS9283 (Figure 7B).

Discussion and conclusions

The selective positive allosteric modulation by NS9283 at the 3α:2β stoichiometry of human α4β2 nAChRs (Lee et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011; Rode et al., 2012; Timmermann et al., 2012) formed the basis for the present study. Using whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology, we carried out an in-depth analysis of how NS9283 exerts its actions on ACh-evoked currents in α4β2 nAChR-expressing HEK293 cells. In order to interpret the mechanism of action of NS9283, various kinetic parameters were approximated to reflect transitions between different receptor states.

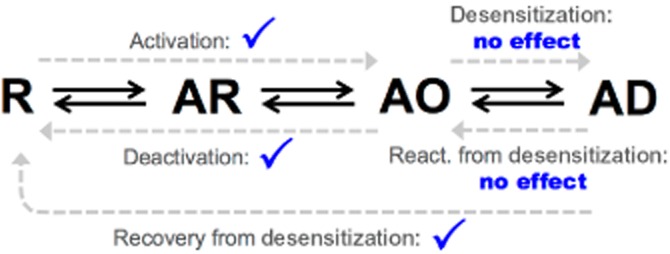

The modulation of the kinetic processes of macroscopic ACh-evoked currents through α4β2 nAChR by NS9283 as demonstrated in this study is outlined in an activation scheme in Figure 8. NS9283 was found to exert its potentiation of the receptor predominantly through a marked reduction of the deactivation rate of macroscopic whole-cell currents. In contrast, NS9283 only exhibited a modest effect on the activation rate and had no major effects on desensitization characteristics, just as it was incapable of reactivating desensitized receptors. This separates NS9283 functionally from many previously published nAChR PAMs, which appear to exert their effects by modulating receptor desensitization characteristics (Hurst et al., 2005; Gronlien et al., 2007; Malysz et al., 2009; Weltzin and Schulte, 2010; Dinklo et al., 2011). In contrast, NS9283 appeared to moderately decrease the rate of receptor recovery from a desensitized state. This was especially apparent at shorter interpulse intervals, an effect possibly explained by the profound effect of NS9283 on deactivation.

Figure 8.

Activation scheme of macroscopic ACh-evoked α4β2 currents and modulation exerted by NS9283. R is the closed unliganded receptor, AR is the closed agonist-bound receptor, AO is the open agonist-bound receptor, and AD is the desensitized agonist-bound receptor. Although not shown in the scheme the possibility of an unliganded desensitized receptor state is assumed and thereby follows the cyclical model proposed by Katz and Thesleff (1957). The grey dashed lines indicate the kinetic processes addressed in this study. The presence of ticks indicate processes that are statistical significantly modulated by NS9283 and ‘no effect’ those not modulated by the PAM as observed in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments in HEK293-hα4β2 cells in this study.

In previous studies, nAChR PAMs have been speculated to affect receptor deactivation kinetics without any further investigation or quantification (Hurst et al., 2005; Dinklo et al., 2011). To our knowledge, this is the first study to address deactivation kinetics of a nAChR PAM using ultra-fast application. Analogously to the pronounced effects of NS9283 on α4β2 deactivation kinetics, PAMs targeting the AMPA-type glutamate receptors, for example aniracetam and CX614, have been shown to primarily exert their effects through modulation of deactivation rather than desensitization kinetics (Arai and Lynch, 1998). Aniracetam has thus been proposed to stabilize an agonist-bound activated AMPA receptor state that ultimately results in a slowed channel deactivation and agonist release (Jin et al., 2005).

A number of PAMs of other Cys-loop receptors exerting their effects by increasing mean channel open time have been shown also to decrease macroscopic desensitization (Hill et al., 1998; Hurst et al., 2005; Sala et al., 2005; Weltzin and Schulte, 2010; daCosta et al., 2011; Nardou et al., 2011). Furthermore, an increase in mean channel open time also appears to result in an increased agonist efficacy (Hurst et al., 2005; Weltzin and Schulte, 2010). In contrast to these PAMs, diazepam, the prototypic benzodiazepine acting as a PAM of GABAA receptors, has a distinct modulation profile as it neither affects macroscopic desensitization at saturating levels (Ghansah and Weiss, 1999; Bianchi et al., 2009) nor agonist efficacy, but exclusively alters agonist potency at the receptors. Furthermore, diazepam has been demonstrated to delay deactivation of GABA-evoked currents (Bianchi and Macdonald, 2001). Thus, at the macroscopic level diazepam modulation of GABAA receptors appears similar to that of NS9283. In single-channel recordings, diazepam has been demonstrated to increase channel opening frequency of GABAA receptors (MacDonald and Twyman, 1992; Macdonald and Olsen, 1994), supposedly through an effect mainly on koff (Bianchi and Macdonald, 2001). The delayed deactivation has been used as an argument for the GABA-‘trapping’ hypothesis, which suggests that GABA dissociation is prevented by the open and desensitized states (Bianchi and Macdonald, 2001). It is tempting to speculate that NS9283 could exert its potentiation of α4β2 signalling in a similar manner. The slowing of deactivation rate arising from NS9283 binding prolongs the duration of the agonist-bound receptor state, and due to the limited effects of NS9283 at desensitization kinetics, this would ultimately result in increased charge transfer. This would also explain the unaltered ACh efficacy with NS9283 at maximal ACh-evoked currents, because the equilibrium is heavily shifted towards agonist association rather than dissociation at high ACh concentrations. It is interesting to note that while a close to maximal concentration of NS9283 results in a ∼60-fold left-shift of the ACh concentration–response curve at α4β2 (Figure 1B), the diazepam-induced increase in GABA potency at the GABAA receptor is substantially more subtle (apprpoximately two- to fivefold) (Verdoorn, 1994). This difference is likely to be rooted in inherent differences between the two receptors.

NS9283 was previously shown to enhance ACh responsiveness of 3α:2β, but not 2α:3β stoichiometry α4β2 nAChRs (Timmermann et al., 2012). Given this unique stoichiometry selectivity, it appears likely that only the 3α:2β receptor presents a binding site for NS9283. A major difference between the two stoichiometries is the presence of an α4α4 subunit interface in the 3α:2β receptor, and it was recently shown that this interface has a third ACh binding site (Harpsøe et al., 2011; Mazzaferro et al., 2011). From the monophasic ACh CRR in presence of NS9283, with an EC50 value mimicking the one for a receptor only activated by its two αβ sites (at low ACh concentrations), occupation of all three binding sites appears necessary for not only full receptor activation, but also NS9283 modulation. Hence, it is tempting to speculate that binding of NS9283 increases the affinity of ACh in the orthosteric α4α4 site. However, functionally, the data could also be consistent with a hypothesis where NS9283 substitutes for ACh binding in the α4α4 site albeit this will require a clarification of the apparent lack of cytisine and epibatidine displacement in binding studies (Timmermann et al., 2012). In either case, the linkage of NS9283 actions to the α4α4 subunit interface provides an explanation to why NS9283 at α4β2 nAChRs give functional readouts that are highly comparable with that of benzodiazepines at GABAA receptors, as these are known to act through a binding site located in the interface between an α- and a γ subunit (Wieland et al., 1992).

With regards to the biphasic ACh CRR observed in the HEK293-hα4β2 cell line in this study, it is important to stress that a significant contribution from 2α:3β receptors to the reported findings is considered unlikely based on the following: (i) NS9283 only has effect on 3α:2β receptors (Timmermann et al., 2012); (ii) a high-sensitive component is an inherent quality of 3α:2β receptors (Harpsøe et al., 2011); and (iii) in this study the high-sensitive component of the ACh CRR comprises 10% of the maximal response, which is less than the high-sensitive component reported by Harpsøe et al. in Xenopus oocytes expressing exclusively 3α:2β receptors (Harpsøe et al., 2011). Combined, these findings strongly speak in favour of the HEK293-hα4β2 cell line predominantly, if not solely, expressing 3α:2β receptors.

Finally, the impact of NS9283 on α4β2 window currents was addressed in this study. The experimental demonstration of an ACh window current suggests the possibility of the nAChRs maintaining residual activity in a certain ACh concentration range despite the concurrent ACh-induced desensitization. This has previously been described for α7 PAMs (Gronlien et al., 2007), but not for α4β2 PAMs. NS9283 was found to left-shift the window current of α4β2, but had no effect on window current AUC (Figure 7B). Any interpretation of how this profile translates into effects on synaptic α4β2 signalling is bound to be speculative. However, in light of reported ACh resting levels in the rat brain in the nanomolar (Vinson and Justice, 1997) to low micromolar (Mattinson et al., 2011) range, we note that this physiologically relevant ACh range to a higher degree is covered by the window current in presence of NS9283 than in absence of the compound. This could speak in favour of NS9283 enhancing cholinergic volume transmission. It should be mentioned that the ACh incubation time used in our experiments is shorter than the one used in a study by Marks et al., in which window currents of α4β2 nAChRs were investigated (Marks et al., 2010). This could potentially give rise to higher ‘desensitization’ IC50 values and thereby a larger window current. In contrast to diffuse volume transmission, ‘wired’ transmission assumes ACh signalling is restricted to the classical synapse. As NS9283 displays no intrinsic agonist activity, in this setting NS9283 would be expected to only augment the responsiveness of α4β2 nAChRs as the ACh concentration decays following a synaptic release, thereby maintaining the spatiotemporal patterns of cholinergic transmission. It has been demonstrated that transient increases in ACh in prefrontal cortex (at the scale of seconds) is necessary for cue detection in a rat attention task (Parikh et al., 2007), involving especially α4β2 nAChRs (Parikh et al., 2008; Howe et al., 2010). Whether NS9283 exerts its demonstrated behavioural effects (Lee et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2011; Rode et al., 2012; Timmermann et al., 2012) through one or both of these transmission modes is at present not clear.

In conclusion, we propose that NS9283 increase ACh responsiveness of the 3α:2β stoichiometry α4β2 nAChR primarily by reducing deactivation kinetics. Besides being a highly useful tool for delineation of specific physiological functions governed by 3α:2β α4β2 nAChRs, we propose that NS9283 could be an efficacious modulator of cholinergic signalling in a synaptic setting and that the compound represents an interesting candidate for future explorations of the drug potential of α4β2 nAChR PAMs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Ministry of Science, Innovation and Higher Education, Denmark, PhD grant 10-084289. The authors acknowledge the technical contributions of Lene G. Larsen and Aino Munch.

Glossary

- AChE

ACh esterase

- CRR

concentration–response relationship

- HEK293-hα4β2

HEK293 cell line stably expressing human α4β2 nAChR

- nAChR

nicotinic ACh receptor

- PAM

positive allosteric modulator

Conflict of interest

Morten Grupe and Philip K. Ahring are employees of NeuroSearch A/S. Jeppe K. Christensen and Morten Grunnet were employed by NeuroSearch A/S at the time of the study.

References

- Albrecht BK, Berry V, Boezio AA, Cao L, Clarkin K, Guo W, et al. Discovery and optimization of substituted piperidines as potent, selective, CNS-penetrant alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor potentiators. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5209–5212. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.08.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostol G, Abi-Saab W, Kratochvil CJ, Adler LA, Robieson WZ, Gault LM, et al. Efficacy and safety of the novel alphabeta neuronal nicotinic receptor partial agonist ABT-089 in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219:715–725. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai A, Lynch G. The waveform of synaptic transmission at hippocampal synapses is not determined by AMPA receptor desensitization. Brain Res. 1998;799:230–234. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00446-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT, Macdonald RL. Agonist trapping by GABAA receptor channels. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9083–9091. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09083.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi MT, Botzolakis EJ, Lagrange AH, Macdonald RL. Benzodiazepine modulation of GABA(A) receptor opening frequency depends on activation context: a patch clamp and simulation study. Epilepsy Res. 2009;85:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe JW, Brooks PR, Vetelino MG, Wirtz MC, Arnold EP, Huang J, et al. Varenicline: an alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist for smoking cessation. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3474–3477. doi: 10.1021/jm050069n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- daCosta CJ, Free CR, Corradi J, Bouzat C, Sine SM. Single-channel and structural foundations of neuronal alpha7 acetylcholine receptor potentiation. J Neurosci. 2011;31:13870–13879. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2652-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinklo T, Shaban H, Thuring JW, Lavreysen H, Stevens KE, Zheng L, et al. Characterization of 2-[ [4-fluoro-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]amino]-4-(4-pyridinyl)-5-thiazoleme thanol (JNJ-1930942), a novel positive allosteric modulator of the {alpha}7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:560–574. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.173245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghansah E, Weiss DS. Benzodiazepines do not modulate desensitization of recombinant alpha1beta2gamma2 GABA(A) receptors. Neuroreport. 1999;10:817–821. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199903170-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giniatullin R, Nistri A, Yakel JL. Desensitization of nicotinic ACh receptors: shaping cholinergic signaling. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Zoli M, Clementi F. Brain nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: native subtypes and their relevance. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotti C, Moretti M, Meinerz NM, Clementi F, Gaimarri A, Collins AC, et al. Partial deletion of the nicotinic cholinergic receptor alpha 4 or beta 2 subunit genes changes the acetylcholine sensitivity of receptor-mediated 86Rb+ efflux in cortex and thalamus and alters relative expression of alpha 4 and beta 2 subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1796–1807. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronlien JH, Hakerud M, Ween H, Thorin-Hagene K, Briggs CA, Gopalakrishnan M, et al. Distinct profiles of alpha7 nAChR positive allosteric modulation revealed by structurally diverse chemotypes. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:715–724. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harpsøe K, Ahring PK, Christensen JK, Jensen ML, Peters D, Balle T. Unraveling the high- and low-sensitivity agonist responses of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:10759–10766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1509-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydar SN, Dunlop J. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors – targets for the development of drugs to treat cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease. Curr Top Med Chem. 2010;10:144–152. doi: 10.2174/156802610790410983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MW, Reddy PA, Covey DF, Rothman SM. Contribution of subsaturating GABA concentrations to IPSCs in cultured hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5103–5111. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05103.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe WM, Ji J, Parikh V, Williams S, Mocaer E, Trocme-Thibierge C, et al. Enhancement of attentional performance by selective stimulation of alpha4beta2(*) nAChRs: underlying cholinergic mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1391–1401. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst RS, Hajos M, Raggenbass M, Wall TM, Higdon NR, Lawson JA, et al. A novel positive allosteric modulator of the alpha7 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor: in vitro and in vivo characterization. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4396–4405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5269-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, Clark S, Weeks AM, Dudman JT, Gouaux E, Partin KM. Mechanism of positive allosteric modulators acting on AMPA receptors. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9027–9036. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2567-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Thesleff S. A study of the desensitization produced by acetylcholine at the motor end-plate. J Physiol. 1957;138:63–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CH, Zhu C, Malysz J, Campbell T, Shaughnessy T, Honore P, et al. alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptor positive allosteric modulation: an approach for improving the therapeutic index of alpha4beta2 nAChR agonists in pain. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:959–966. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lester RA. Activation and desensitization of heteromeric neuronal nicotinic receptors: implications for non-synaptic transmission. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1897–1900. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.02.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald RL, Olsen RW. GABAA receptor channels. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:569–602. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.003033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald RL, Twyman RE. Kinetic properties and regulation of GABAA receptor channels. Ion Channels. 1992;3:315–343. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3328-3_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malysz J, Gronlien JH, Anderson DJ, Hakerud M, Thorin-Hagene K, Ween H, et al. In vitro pharmacological characterization of a novel allosteric modulator of alpha 7 neuronal acetylcholine receptor, 4-(5-(4-chlorophenyl)-2-methyl-3-propionyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)benzenesulfonami de (A-867744), exhibiting unique pharmacological profile. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;330:257–267. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.151886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Meinerz NM, Drago J, Collins AC. Gene targeting demonstrates that alpha4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits contribute to expression of diverse [3H]epibatidine binding sites and components of biphasic 86Rb+ efflux with high and low sensitivity to stimulation by acetylcholine. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53:390–405. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks MJ, Meinerz NM, Brown RW, Collins AC. 86Rb+ efflux mediated by alpha4beta2*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors with high and low-sensitivity to stimulation by acetylcholine display similar agonist-induced desensitization. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1238–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattinson CE, Burmeister JJ, Quintero JE, Pomerleau F, Huettl P, Gerhardt GA. Tonic and phasic release of glutamate and acetylcholine neurotransmission in sub-regions of the rat prefrontal cortex using enzyme-based microelectrode arrays. J Neurosci Methods. 2011;202:199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaferro S, Benallegue N, Carbone A, Gasparri F, Vijayan R, Biggin PC, et al. Additional acetylcholine (ACh) binding site at alpha4/alpha4 interface of (alpha4beta2)2alpha4 nicotinic receptor influences agonist sensitivity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:31043–31054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.262014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moroni M, Zwart R, Sher E, Cassels BK, Bermudez I. alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptors with high and low acetylcholine sensitivity: pharmacology, stoichiometry, and sensitivity to long-term exposure to nicotine. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:755–768. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardou R, Yamamoto S, Chazal G, Bhar A, Ferrand N, Dulac O, et al. Neuronal chloride accumulation and excitatory GABA underlie aggravation of neonatal epileptiform activities by phenobarbital. Brain. 2011;134(Pt 4):987–1002. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson ME, Kuryatov A, Choi CH, Zhou Y, Lindstrom J. Alternate stoichiometries of alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:332–341. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya A, Yakel JL. Allosteric modulators of the alpha4beta2 subtype of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:952–958. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh V, Kozak R, Martinez V, Sarter M. Prefrontal acetylcholine release controls cue detection on multiple timescales. Neuron. 2007;56:141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh V, Man K, Decker MW, Sarter M. Glutamatergic contributions to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist-evoked cholinergic transients in the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3769–3780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5251-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez XA, Bordia T, McIntosh JM, Quik M. alpha6B2* and alpha4B2* nicotinic receptors both regulate dopamine signaling with increased nigrostriatal damage: relevance to Parkinson's disease. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:971–980. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.067561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter AS, Newhouse PA, Bucci DJ. Central nicotinic cholinergic systems: a role in the cognitive dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Behav Brain Res. 2006;175:201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radek RJ, Kohlhaas KL, Rueter LE, Mohler EG. Treating the cognitive deficits of schizophrenia with alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptor agonists. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:309–322. doi: 10.2174/138161210790170166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rode F, Munro G, Holst D, Nielsen EO, Troelsen KB, Timmermann DB, et al. Positive allosteric modulation of alpha4beta2 nAChR agonist induced behaviour. Brain Res. 2012;1458:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala F, Mulet J, Reddy KP, Bernal JA, Wikman P, Valor LM, et al. Potentiation of human alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic receptors by a Flustra foliacea metabolite. Neurosci Lett. 2005;373:144–149. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Bruno JP. Trans-synaptic stimulation of cortical acetylcholine and enhancement of attentional functions: a rational approach for the development of cognition enhancers. Behav Brain Res. 1997;83:7–14. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(97)86039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan JP, Donnelly-Roberts D, Briggs CA, Anderson DJ, Gopalakrishnan M, Xue IC, et al. ABT-089 [2-methyl-3-(2-(S)-pyrrolidinylmethoxy)pyridine]: I. A potent and selective cholinergic channel modulator with neuroprotective properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;283:235–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann DB, Sandager-Nielsen K, Dyhring T, Smith M, Jacobsen AM, Nielsen EO, et al. Augmentation of cognitive function by NS9283, a stiochiometry-dependent positive allosteric modulator of alpha2- and alpha4-containing nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:164–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01989.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn TA. Formation of heteromeric gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors containing two different alpha subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;45:475–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson PN, Justice JB., Jr Effect of neostigmine on concentration and extraction fraction of acetylcholine using quantitative microdialysis. J Neurosci Methods. 1997;73:61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(96)02213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltzin MM, Schulte MK. Pharmacological characterization of the allosteric modulator desformylflustrabromine and its interaction with alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor orthosteric ligands. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:917–926. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.167684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland HA, Luddens H, Seeburg PH. A single histidine in GABAA receptors is essential for benzodiazepine agonist binding. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1426–1429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Decker MW. Neuronal nicotinic receptor agonists for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: focus on cognition. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1212–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ, Bostic J, Prince J, Monuteaux MC, et al. A pilot controlled clinical trial of ABT-418, a cholinergic agonist, in the treatment of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1931–1937. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.12.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Verlinden MH, Adler LA, Wozniak PJ, West SA. ABT-089, a neuronal nicotinic receptor partial agonist, for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: results of a pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1065–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilens TE, Gault LM, Childress A, Kratochvil CJ, Bensman L, Hall CM, et al. Safety and efficacy of ABT-089 in pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from two randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.001. e71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu CZ, Chin CL, Rustay NR, Zhong C, Mikusa J, Chandran P, et al. Potentiation of analgesic efficacy but not side effects: co-administration of an alpha4beta2 neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist and its positive allosteric modulator in experimental models of pain in rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]