Abstract

We have constructed a system for the regulated coexpression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and red fluorescent protein (RFP) fusions in Staphylococcus aureus. It was validated by simultaneous localization of cell division proteins FtsZ and Noc and used to detect filament formation by an actin-like ParM plasmid partitioning protein in its native coccoid host.

TEXT

Multidrug-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus are endemic in hospitals and intensive care units worldwide (1). Despite the clinical importance of S. aureus, understanding of biological processes fundamental to the survival of this organism remains incomplete. In rod-shaped model organisms, such as Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, the elucidation of biological processes has been greatly enhanced through the use of protein labeling strategies using fluorescent protein (FP) probes (2). Cytological studies using FP probes have allowed the spatial and temporal localization of proteins involved in such processes to be determined. Although several systems have been developed and used to label whole S. aureus cells (3, 4), including dual labeling (5), studies describing the temporal compartmentalization of proteins within S. aureus cells are limited. However, several vector systems for the expression of fluorescently tagged fusion proteins in S. aureus have recently been established to address this situation (6, 7). In this work, we describe the construction and use of a two-plasmid system for tightly controlled expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) and red fluorescent protein (RFP) fusion proteins in S. aureus. We anticipate that this vector system will expand the breadth of applications for FP labeling in S. aureus.

Construction and features of pSK9065 and pSK9067, a two-plasmid system for dual GFP and RFP protein labeling in S. aureus.

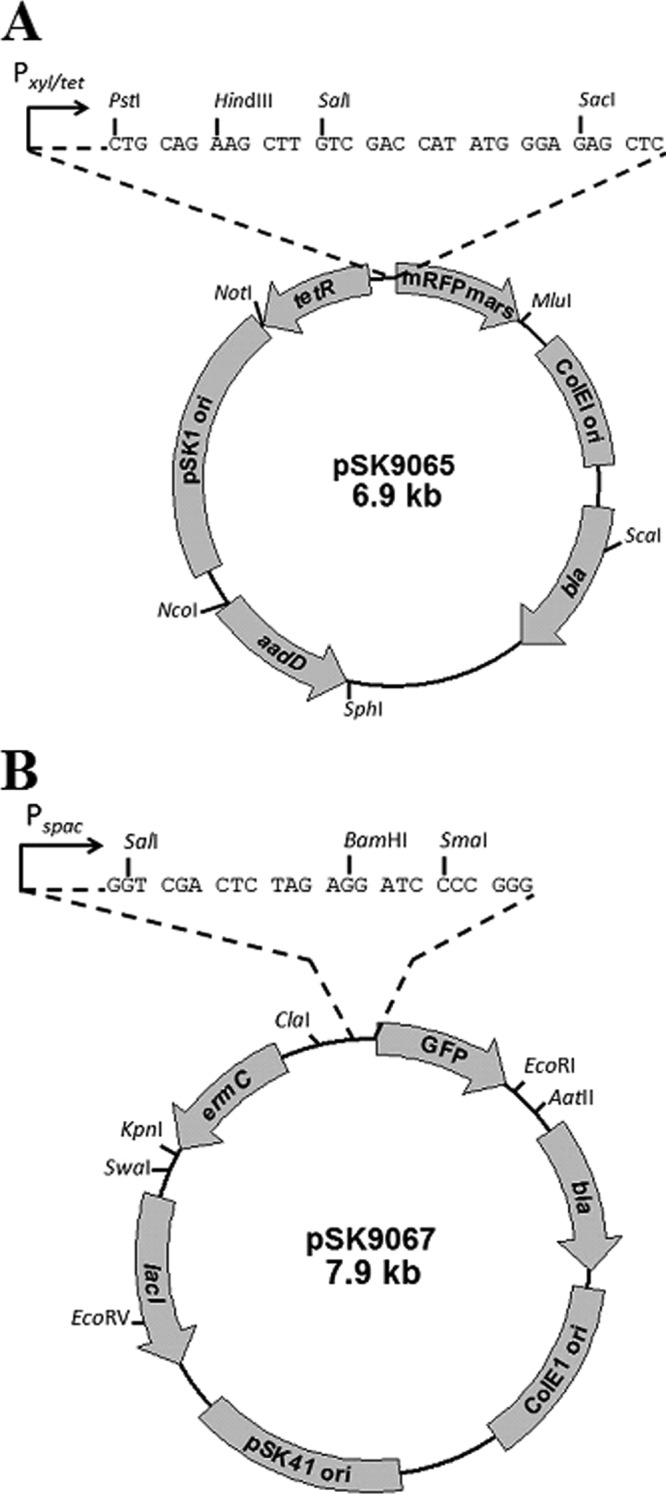

Two compatible and complementary plasmid vectors, pSK9065 and pSK9067 (Fig. 1), were constructed for the generation of regulated RFP and GFP fusion protein expression in S. aureus. The codon usage of both FP genes used, mRFPmars and gfpmut-1, is suitable for expression in low-GC Gram-positive bacteria (8, 9). The excitation and emission spectra for mRFPmars and GFPmut1 are 585 and 602 nm and 488 and 509 nm, respectively. A detailed methodology for the construction of these plasmids is available in the supplemental material. Both plasmids feature high-copy-number E. coli origins of replication and bla genes for ampicillin selection in E. coli. In S. aureus, pSK9065 replicates via the origin of replication from the staphylococcal multiresistance plasmid pSK1, whereas in pSK9067, the compatible origin from the conjugative S. aureus multiresistance plasmid pSK41 is used (10). These low-copy-number theta-replicating staphylococcal origins (5 to 10 copies per cell) were employed to minimize the structural instability that can arise in recombinant plasmids that utilize rolling circle replication (11). pSK9065 contains the aadD gene, which encodes neomycin resistance in S. aureus, whereas pSK9067 harbors ermC, which confers erythromycin resistance. Finally, pSK9065 and pSK9067 contain the Pxyl/tet and Pspac promoters, respectively, which have both been modified to enable tight regulation of the expression of rfp and gfp gene fusions. Specifically, in pSK9065, the tetR promoter contains an optimized −10 box, whereas an additional lacO operator sequence has been engineered into the Pspac promoter of pSK9067. These vectors facilitate tightly controlled expression of fusion proteins in S. aureus to enable visualization in the presence of natively expressed wild-type counterparts.

Fig 1.

Plasmid maps of pSK9065 (A) and pSK9067 (B). A detailed methodology for the construction of pSK9065 and pSK9067 can be found in the supplemental material. Genes: bla, gene conferring ampicillin resistance in E. coli; aadD, gene conferring neomycin resistance in S. aureus; ermC, gene conferring erythromycin resistance in S. aureus; ColEI ori, high-copy-number E. coli origin of replication; pSK1 ori, origin of replication from S. aureus multiresistance plasmid pSK1; pSK41 ori, origin of replication from S. aureus multiresistance plasmid pSK41; tetR, gene encoding the repressor of the Pxyl/tet promoter; lacI, gene encoding the repressor of the Pspac promoter; GFP, gfpmut-1 gene encoding the green fluorescent protein; mRFPmars, geneencoding the mRFPmars red fluorescent protein. Multiple cloning sites (MCS) are shown as expansions above the vector diagrams. Coding sequences to be inserted into the vectors should be cloned with translation initiation sequences but without their stop codon, such that they are in frame with the FP coding sequence; the triplet codon arrangement of the MCS nucleotide sequences indicates the reading frame. Native transcriptional promoters can be incorporated if desired, but gene dosage effects due to plasmid copy number should be considered. Unique restriction sites are shown.

Regulation of improved Pxyl/tet and Pspac promoters.

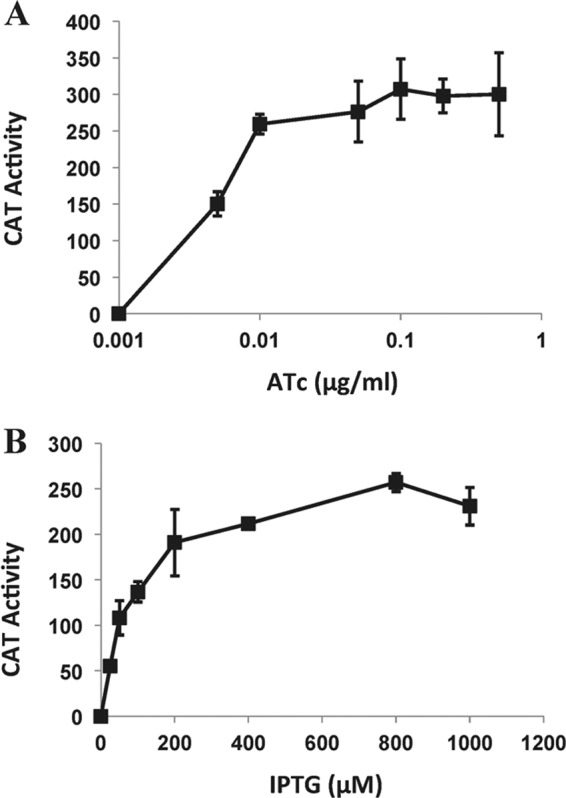

To assess the regulation of the improved promoter-operator regions in pSK9065 and pSK9067, we conducted in vitro chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter gene assays. A DNA fragment amplified from pRB394 using primers AB85 and AB86, which encompasses the cat open reading frame (ORF) and its corresponding ribosome binding site (RBS), was cloned downstream from Pxyl/tet and Pspac in pSK9065 and pSK9067, giving rise to reporter plasmids pSK9066 (Pxyl/tet) and pSK9068 (Pspac), respectively (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The cat ORF in these plasmids contains its own stop codon and therefore does not produce in-frame fusions with the fluorescent reporter genes present on these plasmids. pSK9066 and pSK9068 were separately electroporated into S. aureus RN4220 cells (12), and transformants were selected on solid media containing neomycin (15 μg/ml) or erythromycin (10 μg/ml), respectively. Transcription of the cat gene was induced in mid-log-phase cells using anhydrotetracycline (ATc) or IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside), for pSK9066 or pSK9068, respectively, at eight inducer concentrations. CAT assays were performed as described previously (13). No CAT activity was detected from strains containing either pSK9066 or pSK9068 in the absence of inducer, indicating that the improved Pxyl/tet and Pspac promoter/operator regions in these vectors afford tight repression (Fig. 2A and B). Titratable gene expression was observed over a range of inducer concentrations for each promoter, and induction maxima were observed at 0.1 μg/ml ATc and at 800 μM IPTG for Pxyl/tet and Pspac, respectively.

Fig 2.

Titratable expression of improved Pxyl/tet (A) and Pspac (B) promoters in S. aureus. In vitro CAT assays, using lysates from S. aureus RN4220 cells harboring pSK9066 or pSK9068 reporter plasmids, were performed in a microplate format according to the method of Kwong et al. (12). Eight inducer concentrations of ATc (pSK9066) and IPTG (pSK9068) were tested as shown. CAT activity is expressed as mmol of chloramphenicol acetylated per mg protein per min. Assays were conducted in triplicate using three biological replicates. Standard deviations are shown.

Dual localization of proteins in S. aureus.

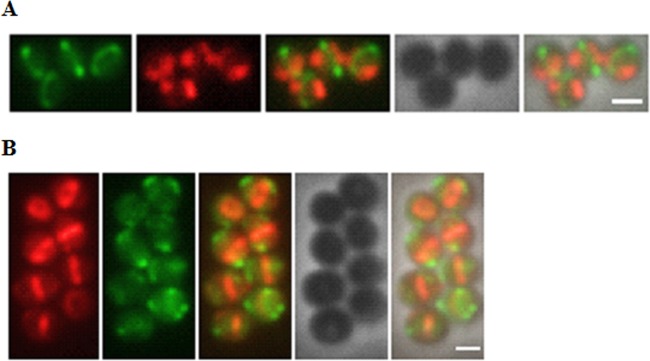

To assess the utility of this system for the simultaneous localization of FP fusions in S. aureus, we constructed in-frame fusions of the cell cycle genes ftsZ and noc with both rfp and gfp, in addition to the construction of an in-frame fusion of the cytoskeletal gene parM with rfp. FtsZ is an essential protein that polymerizes into a distinctive ring-like structure (the Z-ring) at midcell prior to cell division (14). Conversely, the recently characterized protein Noc functions to occlude chromosomal DNA from the divisional plane during cytokinesis (15). ParM is an actin-like protein that is important for the stable maintenance of the staphylococcal multiresistance plasmid pSK41 (16). pSK41 ParM has been shown to form polymers in vitro (17); however, the configuration of ParM in S. aureus cells has yet to be determined. DNA fragments encompassing the ftsZ, noc, and parM coding sequences, and which included the strong RBS from the S. aureus superoxide dismutase (SOD) gene (18) appended during PCR, were ligated into pSK9065 or pSK9067 to produce in-frame fusions of the ftsZ and noc ORFs with gfp or rfp or the parM ORF with rfp, such that the FP is appended to the C terminus of the mature polypeptide; in the cases of Noc and ParM, the FP is joined via a flexible five-amino-acid linker (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Constructs resulting from this process were named pSK9075 (pSK9065; ftsZ-rfp), pSK9076 (pSK9067; ftsZ-gfp), pSK9083 (pSK9065; noc-rfp), pSK9084 (pSK9067; noc-gfp), and pSK9089 (pSK9065; parM-rfp) (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The resulting plasmids were used to generate three separate S. aureus strains: S. aureus RN4220 containing pSK9075 and pSK9084, S. aureus RN4220 containing pSK9076 and pSK9083, and S. aureus RN4220 containing pSK9076 and pSK9089. For fluorescence imaging, a stationary-phase culture of cotransformed strains was used to make a 1:50 dilution in 10 ml fresh LB containing antibiotics, before cultures were incubated at 37°C with shaking. Expression of GFP-fused proteins was induced by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 100 μM, whereas RFP fusions were induced by adding ATc to a final concentration of 0.0025 μg/ml. Optimal visualization of FP probe-protein fusions was achieved after 180 min of growth. Fluorescence imaging was undertaken essentially as described previously (7), using a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 microscope with a Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ camera.

The relative localizations of FtsZ and Noc have recently been described in S. aureus (19) and therefore presented a good starting point for evaluation of the pSK9065-pSK9067 vector system. Micrographs of S. aureus RN4220 strains expressing FtsZ-GFP and Noc-RFP are shown in Fig. 3A, and the localizations of FtsZ-RFP and Noc-GFP are shown in Fig. 3B. In early divisional stages, hemispheric foci can be observed at the peripheries of GFP-decorated Z-rings in some cells (Fig. 3A), whereas in later divisional stages, Z-ring constriction can be seen (Fig. 3B). These results closely parallel the stage-specific distribution of FtsZ elucidated using time-lapse imaging (20). Also in agreement with previously reported results (19), Noc did not colocalize with FtsZ and was largely absent from the predivisional plane, instead forming polar foci (Fig. 3B). Noc foci evident in early stage cell division were more dispersed (Fig. 3A), whereas in later stages, the foci were more compact (Fig. 3B). These differences in Noc distribution may reflect the changing organizational state of the S. aureus nucleoid during the division process.

Fig 3.

Localizations of FP-labeled FtsZ and Noc in S. aureus RN4220 cells. (A) S. aureus RN4220 cells harboring pSK9076 (expressing FtsZ-GFP) and pSK9083 (expressing Noc-RFP). (B) S. aureus RN4220 cells harboring pSK9075 (expressing FtsZ-RFP) and pSK9084 (expressing Noc-GFP). Expression was induced using 0.0025 ATc μg/ml for RFP fusions and with 100 μM IPTG for GFP fusions (see the text for details). Micrographs were processed and pseudocolored using Adobe Photoshop CS5.1. Left to right in both panels: FtsZ-FP, Noc-FP, merge of FtsZ-FP and Noc-FP, phase-contrast image, and merge of FtsZ-FP, Noc FP, and the phase-contrast image. Scale bar, 1 μm.

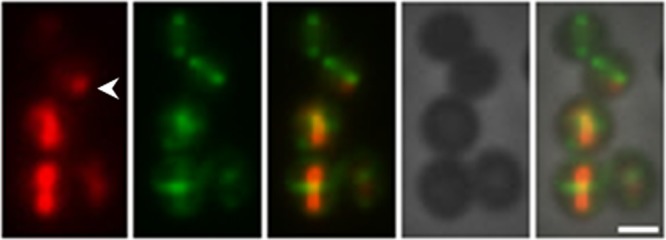

The two-plasmid system was then used to examine the localization of the actin-like ParM protein encoded by the type II partitioning system of the staphylococcal multiresistance plasmid pSK41 (16). ParM-like proteins from rod-shaped bacteria form pole-to-pole axial filaments in vivo (21, 22). Although pSK41 ParM has been shown to form polymers in vitro (17), the in vivo configuration of a ParM protein in a coccoid host has not been determined previously. To investigate this, the pSK41 parM coding sequence was amplified and cloned into pSK9065, as described above, to generate the parM-rfp fusion construct pSK9089 (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), which was subsequently electroporated into S. aureus RN4200 cells harboring pSK9076, which encodes FtsZ-GFP. Fluorescence microscopy revealed that in S. aureus cells, ParM-RFP either formed discrete foci (Fig. 4, first panel, arrowhead) or was polymerized into straight filaments that traversed the diameter of the cell (Fig. 4, cells without the arrowhead; see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These observations demonstrate that pSK41 ParM is able to polymerize into filaments in the absence of the other partitioning system components, parC and ParR, and are consistent with the lack of dynamic instability observed for ParM filaments in isolation in vitro (17). The filament assembly dynamics of pSK41 ParM therefore appear to be more similar to those of pLS31 AlfA from Bacillus subtilis than to the dynamically unstable paradigm ParM of the E. coli plasmid R1 (23, 24). However, the possibility that the other partitioning components of the pSK41 par system might alter ParM filament assembly properties should not be discounted. For example, the cognate centromere and DNA binding protein of the Bacillus subtilis plasmid pLS20 are required to convert filaments composed of their ParM-like partner, Alp7A, from a static to a dynamic configuration by lowering the critical concentration for Alp7A filament formation (25). Notably, our studies showed that pSK41 ParM filaments did not adopt a preferred axial orientation in the coccoid S. aureus cells, since only 30% of filaments were observed to be positioned perpendicular to the Z-ring (n = 113 cells); examples in which filaments are oblique or parallel to the divisional plane are shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material (panel 3, arrowheads).

Fig 4.

Localizations of ParM-RFP and FtsZ-GFP in S. aureus RN4220 cells. S. aureus RN4220 cells were cotransformed with pSK9089 (expressing ParM-RFP) and pSK9076 (expressing FtsZ-GFP), and expression was induced using 0.0025 μg/ml ATc for ParM-RFP fusions and with 100 μM IPTG for FtsZ-GFP fusions (see the text for details). Micrographs were processed and pseudocolored using Adobe Photoshop CS5.1. Left to right: ParM-RFP, FtsZ-GFP, merge of ParM-RFP and FtsZ-GFP, phase-contrast image, and merge of ParM-RFP, FtsZ-GFP, and the phase-contrast image. The arrowhead indicates ParM-RFP foci. Scale bar, 1 μm.

Vector systems that facilitate the localization of multiple fluorescent fusion proteins within S. aureus cells are limited. Pereira et al. (6) have described a set of integrative plasmids that allow the expression of FP fusions from their native chromosomal loci; an additional plasmid able to integrate at the spa locus of S. aureus was also generated for ectopic expression. The two-plasmid system described here affords a complementary approach that provides the option of independently titratable expression of multiple fluorescent fusion proteins in the presence of naturally controlled native counterparts. This system has enabled us to simultaneously localize the cell cycle proteins FtsZ and Noc and to visualize an actin-like ParM partitioning protein in its native coccoid host.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Deborah Barton and Danielle Davies for assistance with microscopy and Martin Fraunholz for making the plasmid pmRFPmars available.

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Project grant 571028.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 March 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00144-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kluytmans J, Struelens M. 2009. Meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the hospital. BMJ 338:b364 doi:10.1136/bmj.b364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lewis PJ. 2004. Bacterial subcellular architecture: recent advances and future prospects. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1135–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malone CL, Boles BR, Lauderdale KJ, Thoendel M, Kavanaugh JS, Horswill AR. 2009. Fluorescent reporters for Staphylococcus aureus. J. Microbiol. Methods 77:251–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guo Y, Ramos RI, Cho JS, Donegan NP, Cheung AL, Miller LS. 2013. In vivo bioluminescence imaging to evaluate systemic and topical antibiotics against community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus-infected skin wounds in mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:855–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boles BR, Horswill AR. 2008. Agr-mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 4:e1000052 doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pereira PM, Veiga H, Jorge AM, Pinho MG. 2010. Fluorescent reporters for studies of cellular localization of proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4346–4353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liew AT, Theis T, Jensen SO, Garcia-Lara J, Foster SJ, Firth N, Lewis PJ, Harry EJ. 2011. A simple plasmid-based system that allows rapid generation of tightly controlled gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology 157:666–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sastalla I, Chim K, Cheung GY, Pomerantsev AP, Leppla SH. 2009. Codon-optimized fluorescent proteins designed for expression in low-GC gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:2099–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Paprotka K, Giese B, Fraunholz MJ. 2010. Codon-improved fluorescent proteins in investigation of Staphylococcus aureus host pathogen interactions. J. Microbiol. Methods 83:82–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Firth N, Apisiridej S, Berg T, O'Rourke BA, Curnock S, Dyke KG, Skurray RA. 2000. Replication of staphylococcal multiresistance plasmids. J. Bacteriol. 182:2170–2178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Janniere L, Bruand C, Ehrlich SD. 1990. Structurally stable Bacillus subtilis cloning vectors. Gene 87:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kreiswirth BN, Lofdahl S, Betley MJ, O'Reilly M, Schlievert PM, Bergdoll MS, Novick RP. 1983. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305:709–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kwong SM, Skurray RA, Firth N. 2004. Staphylococcus aureus multiresistance plasmid pSK41: analysis of the replication region, initiator protein binding and antisense RNA regulation. Mol. Microbiol. 51:497–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ma X, Ehrhardt DW, Margolin W. 1996. Colocalization of cell division proteins FtsZ and FtsA to cytoskeletal structures in living Escherichia coli cells by using green fluorescent protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:12998–13003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu LJ, Errington J. 2004. Coordination of cell division and chromosome segregation by a nucleoid occlusion protein in Bacillus subtilis. Cell 117:915–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schumacher MA, Glover TC, Brzoska AJ, Jensen SO, Dunham TD, Skurray RA, Firth N. 2007. Segrosome structure revealed by a complex of ParR with centromere DNA. Nature 450:1268–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Popp D, Xu W, Narita A, Brzoska AJ, Skurray RA, Firth N, Ghoshdastider U, Maeda Y, Robinson RC, Schumacher MA. 2010. Structure and filament dynamics of the pSK41 actin-like ParM protein: implications for plasmid DNA segregation. J. Biol. Chem. 285:10130–10140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Clements MO, Watson SP, Foster SJ. 1999. Characterization of the major superoxide dismutase of Staphylococcus aureus and its role in starvation survival, stress resistance, and pathogenicity. J. Bacteriol. 181:3898–3903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Veiga H, Jorge AM, Pinho MG. 2011. Absence of nucleoid occlusion effector Noc impairs formation of orthogonal FtsZ rings during Staphylococcus aureus cell division. Mol. Microbiol. 80:1366–1380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Erickson HP, Anderson DE, Osawa M. 2010. FtsZ in bacterial cytokinesis: cytoskeleton and force generator all in one. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74:504–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moller-Jensen J, Jensen RB, Lowe J, Gerdes K. 2002. Prokaryotic DNA segregation by an actin-like filament. EMBO J. 21:3119–3127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Becker E, Herrera NC, Gunderson FQ, Derman AI, Dance AL, Sims J, Larsen RA, Pogliano J. 2006. DNA segregation by the bacterial actin AlfA during Bacillus subtilis growth and development. EMBO J. 25:5919–5931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Polka JK, Kollman JM, Agard DA, Mullins RD. 2009. The structure and assembly dynamics of plasmid actin AlfA imply a novel mechanism of DNA segregation. J. Bacteriol. 191:6219–6230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gerdes K, Howard M, Szardenings F. 2010. Pushing and pulling in prokaryotic DNA segregation. Cell 141:927–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Derman AI, Becker EC, Truong BD, Fujioka A, Tucey TM, Erb ML, Patterson PC, Pogliano J. 2009. Phylogenetic analysis identifies many uncharacterized actin-like proteins (Alps) in bacteria: regulated polymerization, dynamic instability and treadmilling in Alp7A. Mol. Microbiol. 73:534–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]