Abstract

Magnesium-protoporphyrin IX monomethylester cyclase is one of the key enzymes of the bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis pathway. There exist two fundamentally different forms of this enzyme. The oxygen-dependent form, encoded by the gene acsF, catalyzes the formation of the bacteriochlorophyll fifth ring using oxygen, whereas the oxygen-independent form encoded by the gene bchE utilizes an oxygen atom extracted from water. The presence of acsF and bchE genes was surveyed in various phototrophic Proteobacteria using the available genomic data and newly designed degenerated primers. It was found that while the majority of purple nonsulfur bacteria contained both forms of the cyclase, the purple sulfur bacteria contained only the oxygen-independent form. All tested species of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs contained acsF genes, but some of them also retained the bchE gene. In contrast to bchE phylogeny, the acsF phylogeny was in good agreement with 16S inferred phylogeny. Moreover, the survey of the genome data documented that the acsF gene occupies a conserved position inside the photosynthesis gene cluster, whereas the bchE location in the genome varied largely between the species. This suggests that the oxygen-dependent cyclase was recruited by purple phototrophic bacteria very early during their evolution. The primary sequence and immunochemical similarity with its cyanobacterial counterparts suggests that acsF may have been acquired by Proteobacteria via horizontal gene transfer from cyanobacteria. The acquisition of the gene allowed purple nonsulfur phototrophic bacteria to proliferate in the mildly oxygenated conditions of the Proterozoic era.

INTRODUCTION

The anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria are among the oldest organisms on Earth. They evolved more than 3 billion years (3 Gyr) ago under the anoxic conditions of the Archean Ocean (1, 2). Hence, many species of anoxygenic phototrophs remained strictly anaerobic organisms inhabiting anoxic environments. More evolutionary advanced oxygenic cyanobacteria evolved somewhat later (approximately 2.7 Gyr ago), and their rapid spreading resulted in a gradual oxygenation of the Proterozoic Ocean (3, 4). The changing conditions forced many groups of anoxygenic phototrophs (such as purple sulfur bacteria [PSB]) to retreat to marginal anaerobic niches, whereas some adapted to new oxic conditions and became facultative aerobes (i.e., purple nonsulfur bacteria [PNB]). Later, some phototrophic groups embarked on a completely aerobic lifestyle; they lost the ability to fix inorganic carbon and use light energy only as a supplement of their predominantly heterotrophic metabolism (5, 6). These organisms, called aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs (AAPs), were found in marine environments (7–10), but recently their presence was also demonstrated in river estuaries (11) as well as freshwater and saline lakes (12, 13).

The main light-harvesting pigments in the anoxygenic phototrophs are porphyrin molecules called bacteriochlorophylls, whereas oxygenic organisms, cyanobacteria, algae, and plants utilize structurally very similar pigments called chlorophylls (14, 15). A universal structural feature of all these molecules is an isocyclic ring, the formation of which is an essential step of (bacterio)chlorophyll biosynthesis (16). This complex reaction is catalyzed by Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethylester (oxidative) cyclase and results in the conversion of Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester into divinyl protochlorophyllide (see Fig. 1). The anaerobic phototrophs possess an oxygen-independent form of this enzyme containing 4Fe-4S and cobalamin prosthetic groups. The enzyme catalyzes a complex multistep reaction in which the oxygen atom necessary for the reaction is extracted from water (14, 17). An essential component or perhaps the whole oxygen-independent cyclase enzyme is encoded by the bchE gene. A completely different form of this enzyme exists in cyanobacteria, algae, and plants as well as in many PNB and AAP species. Unlike the oxygen-independent form, this enzyme catalyzes the formation of the isocyclic ring using oxygen as a substrate (18). Oxygen-dependent cyclase is expected to be active as a multisubunit complex (19); however, the only known subunit was identified by mutational analysis of the photosynthetic bacterium Rubrivivax gelatinosus (20) and denoted as AcsF (abbreviated from aerobic cyclase). A subsequent genetic study revealed that Rubrivivax contained both forms of the cyclase, which allows the cells to synthesize bacteriochlorophyll under different oxygen concentrations (21). AcsF homologs have since been identified in many cyanobacteria and photosynthetic eukaryotes, including Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (22), Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (23), and Arabidopsis thaliana (24). More recently, the acsF gene was also identified in the green nonsulfur bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus (25).

Fig 1.

A simplified scheme of the conversion of Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethylester into divinyl protochlorophyllide. The reaction is catalyzed by two fundamentally different forms of Mg-protoporphyrin monomethylester cyclase. The oxygen-dependent form of the enzyme encoded by the acsF gene operates under aerobic (oxic) conditions, whereas the oxygen-independent form encoded by the bchE gene operates under anaerobic (anoxic) conditions.

The acquisition of the oxygen-dependent form of the cyclase was proposed to be one of the key adaptations done by anoxygenic phototrophs during the evolutionary transition from anaerobic to aerobic conditions (26). In their recent review, Yurkov and Csotonyi (5) speculated that the presence of the oxygen-dependent cyclase and the absence of the oxygen-independent cyclase could serve as a convenient marker of predominantly aerobic phototrophic species. To test these hypotheses, we surveyed the presence and organization of acsF and bchE genes among various anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria. The obtained molecular information was used to infer the evolutionary origin of the two forms of the cyclase and their current role in anoxygenic phototrophic Proteobacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Anoxygenic phototrophs belonging to alpha, beta, and gamma classes of Proteobacteria were used for the study. Rhodobaca bogoriensis (strain LBB1), Rhodobaca barguzinensis (strain alga-05), Roseinatronobacter strains Dor-vul, Dor-3.5, Da, and Khil-ros, and Rhodobacterales strains Zun-kh and Chep-kr have been isolated from soda lakes as described earlier (27, 28). Marine isolates SO3, SYOP2, BS110, COL2P, B09, and B11, belonging to the Roseobacter clade, Roseovarius sp. strain SL25, Erythrobacter sp. strain NAP1, and Citromicrobium sp. strain CV44, were described previously (29–32). Freshwater betaproteobacterium strain VA01 was isolated from Velka Amerika lake, Czech Republic, by the dilution-to-extinction technique (M. Mašín, unpublished data). Rhodobacter sphaeroides and Rhodobacter capsulatus were cultured photoheterotrophically in organic medium as described previously (32). Cultures of Roseibaca ekhonensis (strain EL50), Roseisalinus antarcticus (strain EL88), and Staleya guttiformis (strain EL 38) were kindly provided by Matthias Labrenz. Sandarakinorhabdus limnophila (strain so42) was provided by Frederic Gich. Congregibacter litoralis strain KT71 (DSM 17192), Roseateles depolymerans (DSM 11813), Roseobacter litoralis (DSM 6996), and Rhodovulum sulfidophilum (DSM 1374) were obtained from the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ), Braunschweig, Germany. Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 was grown photoautotrophically in the BG11 mineral medium. The microbial cultures were grown at room temperature under a light/dark cycle with an irradiance of 150 μmol of photons m−2 s−1 in rotating Erlenmeyer flasks. If not stated otherwise, we used media recommended by the Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DMSZ).

PCR amplification.

Bacterial DNA was extracted using the RTP bacteria DNA minikit (Invitek GmbH, Germany). Partial acsF gene sequences were PCR amplified using forward primer acsF-F and reverse primer acsF-R1, providing a 350-bp gene fragment (see Table 1). The program consisted of 35 cycles with 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 45 s of annealing at 45°C, and 1 min of extension at 72°C. The final extension was conducted for 10 min at 72°C. The bchE gene was amplified with the forward primer bchE-f (see Results) and reverse primer bchE-r2. The PCR program was 30 cycles with 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 45 s of annealing at 52°C, and 1 min of extension at 72°C. The size of the obtained product was 640 bp. In some cases, bchE gene presence was amplified using a bchE-f and bchE-r4 primer pair (Roseococcus sp. strain Da). The amplification conditions remained the same, while annealing was conducted at 48°C. The size of the amplified fragments was 405 bp. The obtained PCR products were purified using a GenElute PCR clean-up kit (Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC) and directly sequenced using the appropriate forward primers. The sequencing results were analyzed and manually corrected using BioEdit (Sequence Alignment Editor) version 5.0.9, Chromas version 1.5.

Table 1.

Primers designed for PCR amplification of bchE and acsF genes

| Primer | Direction | Target positions in the corresponding gene | Primer sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| acsF-F | Forward | 382–404 | 5′-ARTTYTCNGGCTGYGTNCTBTA-3′ |

| acsF-R1 | Reverse | 731–754 | 5′-TGSSDRAAYTCRTCRTTGCACCA-3′ |

| bchE-f | Forward | 640–662 | 5′-AATGGAAATTCTGGCGCGACTA-3′ |

| bchE-r2 | Reverse | 1320–1340 | 5′-GGRTARTGRAANAGCGCCTT-3′ |

| bchE-r4 | Reverse | 1045–1063 | 5′-ACGATGAACTGNGCYTCG-3′ |

GenBank accession numbers.

GenBank accession numbers of partial acsF sequences are as follows: Roseobacter sp. strain Zun-kholvo, JF917109; betaproteobacterium strain VA01, JF917110; Roseobacter sp. strain SY0P2, JF917111; Roseobacter sp. strain SO3, JF917112; Roseovarius sp. strain SL25, JF917113; Sandarakinorhabdus limnophila so42, JF917114; Rhizobiales sp. strain RM11-8-1, JF917115; Roseinatronobacter sp. strain Khil, JF917116; Staleya guttiformis EL38, JF917117; Roseinatronobacter sp. strain Dor-vul, JF917118; Roseinatronobacter sp. strain Dor 3.5, JF917119; Citromicrobium sp. strain CV44, JF917120; Roseobacter sp. strain COL2P, JF917121; Rhodobacterales strain Chep-kr, JF917122; Roseobacter sp. strain B11, JF917123; Roseobacter sp. strain B09, JF917124; Roseococcus sp. strain Da, JF917126; and Rhodobaca barguzinensis alga05, JF917125.

Partial bchE sequences are as follows: Roseobacter sp. strain B09, JF917127; Roseobacter sp. strain B11, JF917128; Citromicrobium sp. strain CV44, JF917129; Roseococcus sp. strain Da, JF917126; Rhodobacterales strain Chep-kr, JF917131; Roseinatronobacter sp. strain Dor 3.5, JF917132; Rhizobiales strain RM11-8-1, JN018414; Roseinatronobacter sp. strain Khil, JN018416; Roseinatronobacter sp. strain Dor-vul, JN018415; Roseobacter sp. strain Zun_kholvo, JN018417; Roseinatronobacter monicus ROS35, JN018418; and Rhodobaca bogoriensis LBB1, JN018419.

Phylogenetic analyses.

The obtained nucleotide sequences were translated into amino acids and aligned using the ClustalX2 program version 2.0.10. The alignments were manually checked; ambiguously aligned regions and gaps were excluded from further analyses. The redundant sequences representing different strains of the same species (i.e., Rhodopseudomonas palustris, Rhodobacter sphaeroides) were removed. The sequence identity matrix was calculated from the corrected alignment using the ClustalX2 program. The phylogenetic trees were computed from partial amino acid sequences using a neighbor-joining algorithm with 1,000 bootstraps. In addition, the inferred phylogeny was confirmed by the maximum likelihood algorithm (PhyML software) using the LG model chosen by the ProtTest 2.4 algorithm.

Isolation of cell membranes and immunodetection of AcsF homologs.

The bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in a breakage buffer containing 25 mM MES buffer (pH 6.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 25% glycerol. The cells were disrupted in a beadbeater (BioSpec Products Inc.) using zirconia/silica beads 0.1 mm in diameter. The disruption was performed in four 1-min cycles interrupted by 5 min of cooling on ice to prevent potential protein degradation. Cell membranes were pelleted by centrifugation at 40,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min, washed in the breakage buffer, and finally resuspended in 100 μl of the same buffer.

The obtained membranes were solubilized by 2% dodecyl-β-maltoside, spun down to remove cell debris, and separated by 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The proteins were then transferred onto the Hybond-P polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Biosciences, Sweden), which was incubated with polyclonal antibody raised against the AcsF protein (CHL27) from Arabidopsis thaliana (Agrisera AB, Sweden) to detect the presence of AcsF homologs in the photosynthetic bacteria studied.

RESULTS

Genome survey.

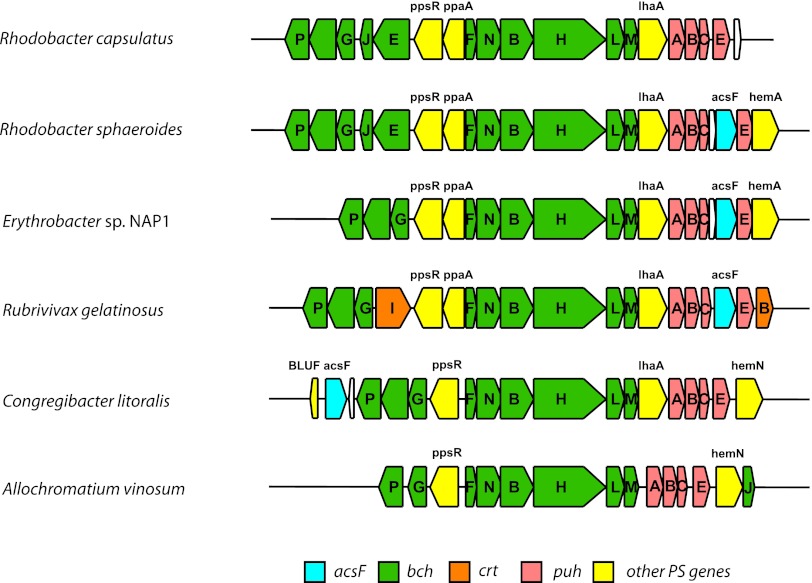

In the first stage of this work, we computationally surveyed the genome sequences of 53 phototrophic Proteobacteria available in GenBank. Twenty-one species contained both the acsF and bchE genes (see Table 2). All PSB species and five PNB species (Rhodospirillum rubrum, Rhodospirillum photometricum, Phaeospirillum molischianum, Rhodomicrobium vannielii, and Rhodobacter capsulatus) contained only the bchE gene, which was consistent with their anaerobic character. On the other hand, 18 predominantly aerobic species contained only the acsF gene (see Table 2). In our survey, we noticed that, if present, the acsF gene was always located inside the so-called photosynthesis gene cluster (PGC) together with other photosynthesis genes (see also reference 33). In all studied Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria, the acsF gene was placed inside the puh operon (between the puhABC and puhE genes), whereas in aerobic members of the NOR5 cluster (Gammaproteobacteria) it was located independently at the periphery of the PGC (see Fig. 2). In contrast, bchE was found inside (i.e., Rhodobacter sphaeroides), at the border of (i.e., Congregibacter litoralis), or outside (i.e., Dinoroseobacter shibae, Roseobacter denitrificans) the PGC. The presence of a bchE gene either inside or outside PGC is shown in Table 2. Frequently, the bchE gene was located together with the bchJ gene (i.e., Acidiphilium multivorum, Rhodopseudomonas palustris, Rhodobacter capsulatus); however, in some cases, bchE and bchJ were situated separately (i.e., Roseobacter litoralis, gammaproteobacterium strain HTCC2080).

Table 2.

Presence of the acsF and the bchE genes among full-genome-sequenced phototrophic Proteobacteria

| Organism | GenBank no. | Group | Presence/absencea of: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acsF | bchE | |||

| Acidiphilium multivorum AIU301 | AP012035 | α1, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Phaeospirillum molischianum DSM 120 | ZP_09875400 | α1, PNB | − | ∘ |

| Rhodospirillum centenum SWb | CP000613 | α1, PNB | • | ∘ |

| Rhodospirillum rubrum ATCC 11170 | CP000230 | α1, PNB | − | ∘ |

| Rhodospirillum photometricum DSM 122 | YP_005416037 | α1, PNB | − | ∘ |

| Ahrensia sp. strain R2A130 | NZ_AEEB01000017 | α2, AAP | • | − |

| Agrobacterium albertimagni AOL15 | ALJF00000000 | α2, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Hoeflea phototrophica DFL43 | NZ_ABIA02000022 | α2, AAP | • | − |

| Labrenzia alexandrii DFL11 | NZ_EQ973123.1 | α2, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Methylobacterium sp. strain 4-46 | CP000943 | α2, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Methylobacterium radiotolerans | CP001001 | α2, AAP | • | − |

| Methylobacterium populi BJ001 | YP_001927978 | α2, AAP | • | − |

| Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 | YP_002966142 | α2, AAP | • | − |

| Methylocella silvestris BL2 | CP001280 | α2, AAP | • | − |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. strain BTAi1 | CP000494 | α2, PNB | • | • |

| Bradyrhizobium sp. strain ORS278 | CU234118 | α2, PNB | • | • |

| Rhodomicrobium vannielii ATCC 17100 | NC_014664 | α2, PNB | − | ∘ |

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris | Multipled | α2, PNB | • | ∘ |

| Dinoroseobacter shibae DFL12 | CP000830 | α3, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Jannaschia sp. strain CCS1 | CP000264 | α3, AAP | • | − |

| Loktanella vestfoldensis SKA53 | AAMS01000000 | α3, AAP | • | − |

| Roseobacter denitrificans Och 114 | CP000362 | α3, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Roseobacter litoralis Och 149c | ABIG00000000 | α3, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Roseobacter sp. strain AzwK-3b | ABCR00000000 | α3, AAP | • | • |

| Roseobacter sp. strain CCS2 | AAYB00000000 | α3, AAP | • | − |

| Roseovarius sp. strain TM1035 | ABCL00000000 | α3, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Roseovarius sp. strain 217 | AAMV00000000 | α3, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Rhodobacter capsulatus SB 1003 | NC_014034 | α3, PNB | − | • |

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | Multiplee | α3, PNB | • | • |

| Rhodobacter sp. strain SW2 | ZP_05842911 | α3, PNB | • | • |

| Erythrobacter sp. strain NAP1 | AAMW00000000 | α4, AAP | • | − |

| Citromicrobium bathyomarinum JL354 | ZP_06861151 | α4, AAP | • | ∘ |

| Sphingomonas spp. | Multiplef | α4, AAP | • | − |

| Brevundimonas subvibrioides ATCC 15264 | CP002102 | α4, AAP | • | − |

| Rubrivivax gelatinosus IL-114 | NC_017075 | β, PNB | • | ∘ |

| Rubrivivax benzoatilyticus JA2 | NZ_AEWG01000000 | β, PNB | • | ∘ |

| Methyloversatilis universalis FAM5 | ZP_08506871 | β, PNB | • | − |

| Limnohabitans sp. strain Rim28 | ALKN00000000 | β, PNB | • | − |

| Limnohabitans sp. strain Rim47 | ALKO00000000 | β, PNB | • | − |

| Allochromatium vinosum DSM 180 | NC_013851 | γ, PSB | − | ∘ |

| Ectothiorhodospira sp. strain PHS-1 | NZ_AGBG01000002 | γ, PSB | − | ∘ |

| Halorhodospira halophila SL1 | CP000544 | γ, PSB | − | • |

| Marichromatium purpuratum 984 | NZ_AFWU01000001 | γ, PSB | − | ∘ |

| Thiocapsa marina 5811 | NZ_AFWV01000003 | γ, PSB | − | ∘• |

| Thiocystis violascens DSM198 | AGFC00000000 | γ, PSB | − | ∘ |

| Thioflavicoccus mobilis 8321 | NC_019940 | γ, PSB | − | ∘ |

| Thiorhodococcus drewsii AZ1 | NZ_AFWT01000007 | γ, PSB | − | ∘ |

| Thiorhodospira sibirica ATCC 700588 | AGFD01000016 | γ, PSB | ∘ | |

| Congregibacter litoralis KT71 | AAOA01000014 | γ, AAP | • | • |

| Gammaproteobacterium strain NOR5-3 | ZP_05125815 | γ, AAP | • | • |

| Gammaproteobacterium strain NOR51-B | NZ_DS999411 | γ, AAP | • | |

| Gammaproteobacterium strain HTCC2080 | NZ_DS999405 | γ, AAP | • | |

| Gammaproteobacterium strain HIMB55 | ZP_09691978 | γ, AAP | • | |

The genome data were obtained from GenBank. •, gene present in the PGC; ∘, gene present outside PGC; −, gene absent.

Alternative name, Rhodocista centenaria.

In Roseobacter litoralis, PGC is located on a plasmid whereas the bchE gene is located on the chromosome.

Represents the following strains of Rhodopseudomonas palustris: TIE-1 (CP001096), BisA53 (CP000463), BisB18 (CP000301), BisB5 (CP000283), CGA009 (BX571963), HaA2 (NC_007778), and DX-1 (NC_014834).

Represents the following strains of R. sphaeroides: 2.4.1. (CP000143), KD131 (NC_011963), WS8N (AFER01000001), ATCC 17029 (NC_009049), and ATCC 17025 (NC_009428).

Represents the following Sphingomonas isolates: S. echinoides ATCC 14820 (AHIR00000000) and Sphingomonas sp. strains PAMC 26605 (AHIS00000000), PAMC 26617 (AHHA00000000), and PAMC 26621 (AIDW00000000).

Fig 2.

Positions of acsF genes in photosynthetic gene clusters (partial) in various phototrophic species. Rhodobacter capsulatus and Allochromatium vinosum are shown for comparison as an example of organisms devoid of the acsF gene.

Design of universal PCR primers.

Apart from analyzing the GenBank data, we designed universal primers for both aerobic and anaerobic forms of oxidative cyclase to survey the presence of these genes in other species of phototrophic Proteobacteria (see Fig. S1 and S2 in the supplemental material). The new primers were used to survey for the presence of acsF and bchE genes in 22 strains of AAP bacteria belonging to various subgroups of Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria. In addition, we included three strains of PNB belonging to Rhodobacterales which exhibit both aerobic and anaerobic growth (Table 3). The acsF gene fragments were successfully amplified in all tested strains (Fig. 3A). However, while the bchE gene was detected in all PNB species, it was detected only in 10 AAP strains (Fig. 3B, Table 3). All the obtained PCR products were purified and sequenced.

Table 3.

Presence of acsF and bchE genes in the tested strains of phototrophic Proteobacteria

| Strain | Group | Environment | Presence/absencea of: |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| acsF | bchE | |||

| Roseococcus strain Da | α1, AAP | Mud volcano | + | + |

| Rhizobiales strain RM11-8-1 | α2, AAP | Marine | + | + |

| Roseobacter strain SO3 | α3, AAP | Marine | + | − |

| Roseobacter strain SYOP2 | α3, AAP | Marine | + | − |

| Roseobacter strain BS110 | α3, AAP | Marine | + | − |

| Roseobacter strain COL2P | α3, AAP | Marine | + | − |

| Roseobacter strain B09 | α3, AAP | Marine | + | + |

| Roseobacter strain B11 | α3, AAP | Marine | + | + |

| Roseisalinus antarcticus EL-88 | α3, AAP | Hypersaline lake | + | − |

| Staleya guttiformis EL-38 | α3, AAP | Hypersaline lake | + | − |

| Roseibaca ekhonensis EL-50 | α3, AAP | Hypersaline lake | + | − |

| Roseovarius strain SL25 | α3, AAP | Hypersaline lake | + | − |

| Roseinatronobacter monicus ROS35 | α3, AAP | Soda lake | + | + |

| Roseinatronobacter strain Dor-vul | α3, AAP | Mud volcano | + | + |

| Roseinatronobacter strain Dor-3.5 | α3, AAP | Soda lake | + | + |

| Roseinatronobacter strain Khil-ros | α3, AAP | Soda lake | + | + |

| Roseobacter strain Zun-kh | α3, AAP | Soda lake | + | + |

| Rhodobacterales strain Chep-kr | α3, AAP | Soda lake | + | + |

| Rhodobaca barguzinensis alga-05 | α3, PNB | Soda lake | + | + |

| Rhodobaca bogoriensis LBB1 | α3, PNB | Soda lake | + | + |

| Rhodovulum sulfidophilum DSM 1374 | α3, PNB | Marine sediments | + | + |

| Citromicrobium strain CV44 | α4, AAP | Marine | + | + |

| Sandarakinorhabdus limnophila so42 | α4, AAP | Fresh water | + | − |

| Betaproteobacterium strain VA01 | β, AAP | Fresh water | + | − |

| Roseateles depolymerans DSM11813 | β, AAP | Fresh water | + | − |

+, gene present; −, gene absent or not amplified.

Fig 3.

Electrophoretic analysis of PCR products for the acsF gene (A) and the bchE gene (B). Description of the lines: M, marker; 1, Roseococcus sp. Da; 2, Hoeflea phototrophica; 3, Labrenzia alexandrii; 4, Rhodobacterales strain SO3; 5, Rhodobacterales strain SYOP2; 6, Roseobacter sp. COL2P; 7, Roseibaca ekhonensis; 8, Staleya guttiformis; 9, Roseinatronobacter sp. Khil-ros; 10, Sandarakinorhabdus limnophila so42; 11, Roseobacter sp. Chep-kr; 12, Rhodobacterales sp. Dor-vul; 13, Citromicrobium sp. CV44; 14, Betaproteobacterium VA01; 15, Rhodobaca barguzinensis; 16, Rhodobacter sphaeroides (used as the positive control).

Phylogeny of acsF and bchE genes.

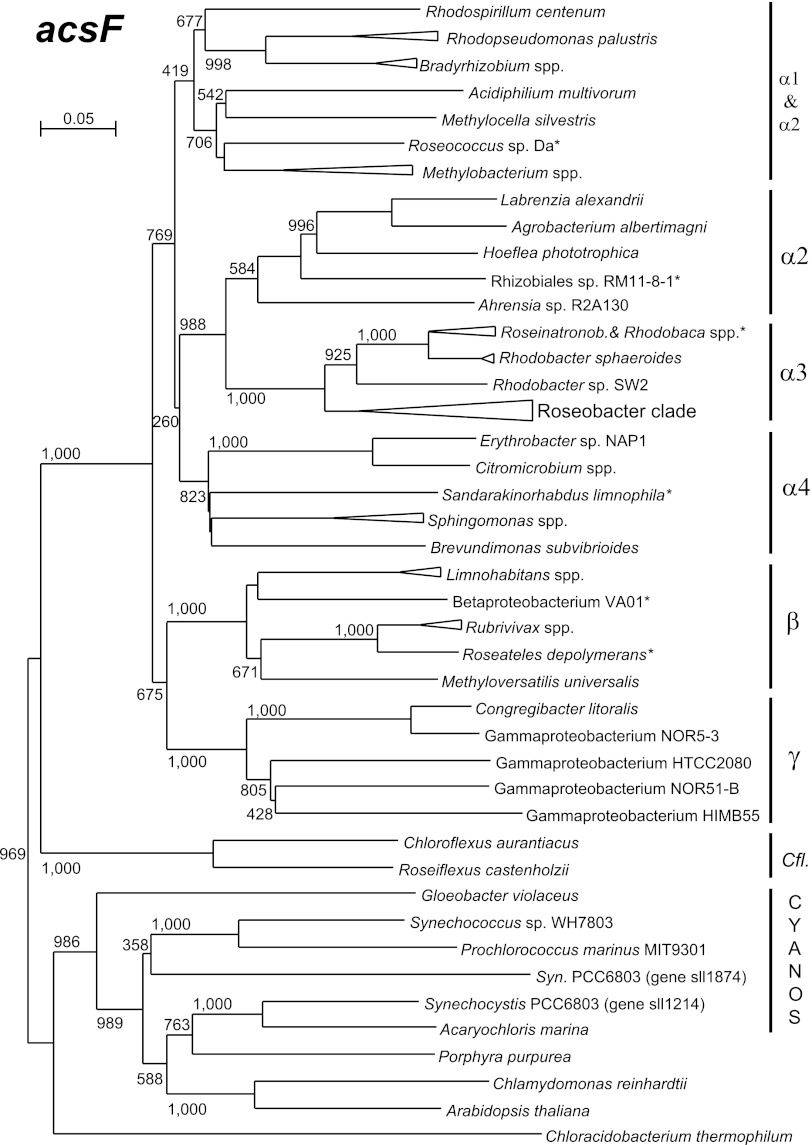

To analyze the phylogenetic relationship and potential evolutionary origin of genes coding for oxygen-dependent cyclase, we constructed phylogenetic trees using sequences obtained from both GenBank and de novo sequencing. We have also included the acsF sequences from various oxygenic organisms encompassing unicellular cyanobacteria, algae, and higher plants (here, acsF was encoded on chloroplast chromosomes). The phylogenetic tree was calculated from partial amino acid sequences using the neighbor-joining algorithm (the analysis was also performed using the maximum likelihood algorithm, but the maximum likelihood tree suffered from overall low bootstrap values). The constructed tree displayed relatively well-separated individual subgroups (α-1, α-2, α-3, α-4) of Alphaproteobacteria, as well as Beta- and Gammaproteobacteria, which signalized a good agreement with 16S rRNA-derived phylogeny (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The proteobacterial sequences were clearly separated from those of various oxygenic organisms (cyanobacteria, algae, and plants) and green nonsulfur bacteria Chloroflexus and Roseiflexus (Fig. 4). The amino acid sequences of the selected oxygenic organisms had a 42% ± 3% (mean ± standard deviation) identity to the proteobacterial sequences, while the average sequence identity among tested Proteobacteria was 61% ± 7% (calculated for 34 organisms).

Fig 4.

Phylogenetic tree as inferred from partial acsF amino acid sequences (312 amino acids). The tree was computed using a neighbor-joining algorithm. Species with shorter sequences obtained by PCR (marked with an asterisk) were added later to the tree. Numbers above protein trees indicate bootstrap values (1,000 replicates). Roseinatronob., Roseinatronobacter; Syn., Synechocystis sp.

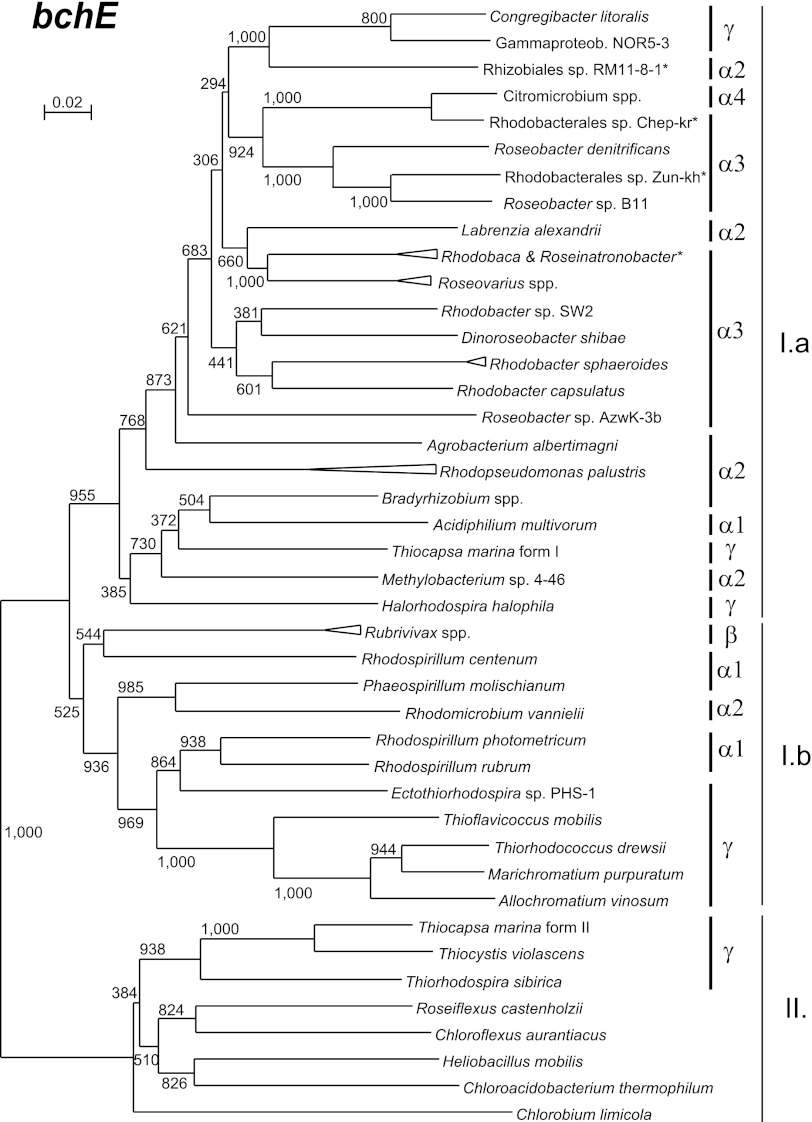

A different situation was encountered for the phylogeny of the oxygen-independent cyclase. Here, the constructed phylogenetic tree (Fig. 5) differed significantly from the 16S rRNA phylogeny (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The bchE tree clearly split (bootstrap = 1,000/1,000) into two main clades, suggesting that two forms of bchE genes exist (Fig. 5). The first clade (cluster I) is formed by the majority of Proteobacteria, whereas the second clade (cluster II) was formed by other phototrophic phyla, such as Chlorobi, Chloroflexi, and Chloracidobacterium tepidum. Cluster I could be further divided into subcluster Ia, which contained mostly Alphaproteobacteria, and mixed subcluster Ib. The complicated phylogeny of the bchE gene can be best documented on the example of Gammaproteobacteria. While Halorhodospira halophila (Ectothiorhodospiraceae) and Congregibacter litoralis (NOR5 clade) clustered by Alphaproteobacteria forming cluster Ia, some PSB from the Chromatiaceae family (Allochromatium vinosum and Marichromatium purpuratum) belonged to the mixed cluster Ib. In addition, two other PSB species, Thiocystis violascens (Chromatiaceae) and Thiorhodospira sibirica (Ectothiorhodospiraceae), belonged to cluster II. Moreover, Thiocapsa marina contained two forms of the bchE gene, one belonging to cluster Ia and the other to cluster II (Fig. 5). Even within Alphaproteobacteria, the situation was complex. The bchE sequences from α-1 and α-2 species were largely scattered across both clusters Ia and Ib. Such topology suggests relatively common horizontal gene transfers of this gene, perhaps driven by a strong environmental selection.

Fig 5.

Phylogenetic tree as inferred from partial bchE amino acid sequences (202 amino acids). The tree was computed using the neighbor-joining algorithm. Numbers above protein trees indicate bootstrap values (1,000 replicates). Sequences obtained by the PCR are marked by an asterisk. Gammaproteob., Gammaproteobacteria.

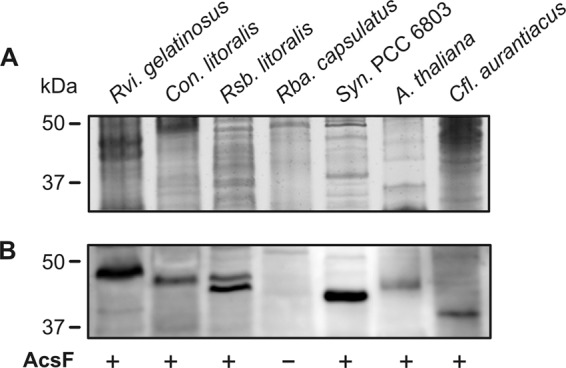

Immunodetection of AcsF homologs in photosynthetic bacteria.

To confirm the presence of the AcsF protein and also to test its structural similarity in different groups of photosynthetic bacteria, we detected this protein using an anti-AcsF antibody raised against the AcsF homolog from Arabidopsis thaliana (24). As the AcsF protein is known to be tightly associated with membranes (24, 34), we first isolated membrane fractions from Roseobacter litoralis (Alphaproteobacteria), Rubrivivax gelatinosus (Betaproteobacteria), Congregibacter litoralis (Gammaproteobacteria), and Chloroflexus aurantiacus (green nonsulfur bacterium). The membrane proteins were then separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 6A), blotted, and probed with the anti-AcsF antibody (Fig. 6B). Membrane proteins from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, Arabidopsis thaliana, and Rhodobacter capsulatus were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The antibody reacted with all four samples, producing bands of the expected sizes (39 to 42 kDa). It is noteworthy that AcsFs from Roseobacter litoralis appears to form a double band, indicating a specific protein modification or fast degradation not observed in cyanobacteria. Nonetheless, given that the used antibody was raised against the plant AcsF homolog, our results suggest that the oxygen-dependent cyclase is a conserved enzyme despite being employed by very evolutionarily distant organisms such as anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria and oxygenic cyanobacteria or plants.

Fig 6.

Isolation and separation of membrane proteins from photosynthetic organisms and immunodetection of AcsF protein. (A) Approximately 10 μg of solubilized membrane proteins was separated by SDS electrophoresis and stained with Coomassie blue. (B) The separated proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and probed by polyclonal anti-AcsF antibody generated using the AcsF homolog of Arabidopsis thaliana (see Materials and Methods). Membrane fractions of Arabidopsis thaliana and the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803 were included as positive controls, and anaerobic bacterium Rhodobacter capsulatus was included as a negative control. Rvi. gelatinosus, Rubrivivax gelatinosus; Rsb. litoralis, Roseobacter litoralis; Rba. capsulatus, Rhodobacter capsulatus; Cfl. aurantiacus, Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Con. Litoralis, Congregibacter litoralis; Syn. PCC 6803, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803; A. thaliana, Arabidopsis thaliana.

DISCUSSION

The performed survey revealed that different functional groups of phototrophic Proteobacteria employ different forms of the cyclase. All investigated PSB contained the bchE gene only, which is consistent with their strictly anaerobic lifestyle. The majority of the tested PNB species contained both genes. As could be expected from their aerobic character, all AAP species contained the acsF gene; however, in contrast to Yurkov and Csotonyi's original assumption (5), about half of the AAP strains also contained the bchE gene.

The origin of the oxygen-independent form of the cyclase among phototrophic proteobacteria is not completely clear. Presumably, it represents an ancient form of the cyclase, which is consistent with its presence in all main phyla containing anoxygenic phototrophs. On the other hand, the bchE phylogenetic tree indicates a very complex evolutionary history (see Fig. 4). Moreover, in contrast to the conserved position of acsF inside the PGC, bchE occurs in different places in the genome, both inside or outside the PGC. All this suggests that the bchE gene was probably transferred several times during the evolution. This is especially evident among Gammaproteobacteria, where individual species possess completely unrelated forms of the cyclase. As the phylogeny partially displays ecological subclusters such as halophilic species (marine and soda and salt lake strains), freshwater, or strictly anaerobic purple sulfur bacteria, this may signalize a strong environmental selection pressure on this gene.

The function of the bchE gene in AAP species is not clear. One explanation is that AAPs may use this gene to supplement the activity of oxygen-dependent cyclase in situations when they are temporarily facing anaerobic conditions. On the other hand, a bchE gene homologue was also found in the heterotrophic organism Acidiphilium cryptum strain JF-5 (GenBank accession no. CP000697). Also, three bchE gene homologues were identified in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803, which, however, did not seem to have any cyclase activity (22). All this indicates that the bchE genes in AAP species may encode proteins with another enzymatic function.

A very different situation was encountered in the case of the acsF gene. Unlike the bchE gene, the acsF gene phylogeny corresponds relatively well with 16S rRNA-based phylogeny (Fig. 4; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Moreover, in all investigated Alpha- and Betaproteobacteria, the acsF genes occupy the same conserved position inside the PGC (Fig. 2; see also reference 33). All this evidence suggests that the adoption of the oxygen-dependent cyclase by proteobacteria occurred in a single event. The origin of the acsF gene cannot be clearly reconciled based on available genetic data. However, based on both the similarity between proteobacterial and cyanobacterial acsF sequences (42% ± 3%) and the immunoreactivity of bacterial AcsF proteins with plant anti-AcsF antibody (Fig. 6), we speculate that the acsF gene may have been transferred between PNB and cyanobacteria via horizontal gene transfer. The direction of the transfer cannot be unambiguously determined using the current data. The fact that oxygenic cyanobacteria were naturally exposed to oxygen, whereas anoxygenic species were originally anaerobes, however, suggests that the gene first evolved in cyanobacteria and only later was it transferred to Proteobacteria.

The timing of the acsF adoption by Proteobacteria can be estimated using the available genomic data. The fact that acsF genes were found in all major proteobacterial lineages (Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaproteobacteria) indicates that its acquisition probably occurred only shortly after the radiation of Proteobacteria. Using the molecular clock calculation, Battistuzzi et al. (35) estimated that the Proteobacteria evolved together with the onset of oxygenic photosynthesis approximately 2.6 to 2.3 Gyr ago. This suggests that the acsF gene may have been acquired during the early Proterozoic (Paleoproterozoic) period. Such a scenario is consistent with the current biogeochemical models. During the Archean period, the Earth's atmosphere was largely anoxic. At the beginning of the Proterozioc era, oxygen produced by cyanobacteria started to gradually oxygenate the Earth's atmosphere. Based on the geological record, it was estimated that the so-called Great Oxidation event occurred approximately 2.45 to 2.0 Gyr ago (4). After that, the concentration of oxygen stayed relatively constant (0.02 to 0.04 atm) through most of the Proterozoic era (till approximately 0.85 Gyr ago). During this period, the ocean was probably mildly oxygenated at its surface, whereas the deep waters remained anoxic, providing an environment supporting both anoxygenic and oxygenic phototrophs (36), facilitating the horizontal gene transfer event. Since the enzymatic activity of the oxygen-independent cyclase is strongly inhibited by free oxygen (21, 37), the adoption of the oxygen-dependent cyclase was a necessary step, allowing the early purple phototrophic bacteria to adapt to new conditions (26). Therefore, we suggest that the acquisition of the oxygen-dependent cyclase by Proteobacteria was an important innovation which allowed the evolutionary transition from anaerobic to aerobic conditions and facilitated the radiation of purple nonsulfur species during the Proterozoic era. We speculate that the fully aerobic AAP species probably evolved only later, at the end of the Proterozoic era, when oxygen concentrations reached approximate present levels.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by GAČR projects P501/10/0221 and P501/12/G055 and project Algatech (CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0110).

We are indebted to Matthias Labrenz, Frederic Gich, and Vladimir Gorlenko for their kind gift of AAP strains, Dzmitry Hauruseu for his help with bacterial cultures, and Michal Mašín for providing DNA from his VA01 isolate.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 February 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00104-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blankenship RE. 2010. Early evolution of photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 154:434–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Des Marais DJ. 2000. Evolution: when did photosynthesis emerge on Earth? Science 289:1703–1705 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Buick R. 2008. When did oxygenic photosynthesis evolve? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 363:2731–2743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holland HD. 2006. The oxygenation of the atmosphere and oceans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 361:903–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yurkov VV, Csotonyi JT. 2009. New light on aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs, p 31–55 In Hunter CN, Daldal F, Thurnauer MC, Beatty JT. (ed), The purple phototrophic bacteria. Advances in photosynthesis and respiration, vol 28 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hauruseu D, Koblížek M. 2012. The influence of light on carbon utilization in aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:7414–7419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kolber ZS, Plumley FG, Lang AS, Beatty JT, Blankenship RE, VanDover CL, Vetriani C, Koblizek M, Rathgeber C, Falkowski PG. 2001. Contribution of aerobic photoheterotrophic bacteria to the carbon cycle in the ocean. Science 292:2492–2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiao N, Zhang Y, Zeng Y, Hong N, Liu R, Chen F, Wang P. 2007. Distinct distribution pattern of abundance and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the global ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 9:3091–3099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yutin N, Suzuki MT, Teeling H, Weber M, Venter JC, Rusch DB, Béjà O. 2007. Assessing diversity and biogeography of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in surface waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans using the Global Ocean Sampling expedition metagenomes. Environ. Microbiol. 9:1464–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koblížek M. 2011. Role of photoheterotrophic bacteria in the marine carbon cycle, p 49–51 In Jiao N, Azam F, Sanders S. (ed), Microbial carbon pump in the ocean. Science/AAAS, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 11. Waidner LA, Kirchman DL. 2007. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria attached to particles in turbid waters of the Delaware and Chesapeake estuaries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3936–3944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mašín M, Nedoma J, Pechar L, Koblížek M. 2008. Distribution of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in temperate freshwater systems. Environ. Microbiol. 10:1988–1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Medová H, Boldareva E, Hrouzek P, Borzenko S, Namsaraev Z, Gorlenko V, Namsaraev B, Koblížek M. 2011. High abundances of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in saline steppe lakes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 76:393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Willows R, Kriegel M. 2009. Biosynthesis of bacteriochlorophylls in purple bacteria, p 57–79 In Hunter CN, Daldal F, Thurnauer MC, Beatty JT. (ed), The purple phototrophic bacteria. Advances in photosynthesis and respiration, vol 28 Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chew AGM, Bryant DA. 2007. Chlorophyll biosynthesis in bacteria: the origins of structural and functional diversity. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:113–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chereskin BM, Wong YS, Castelfranco PA. 1982. In vitro synthesis of the chlorophyll isocyclic ring: transformation of Mg-protoporphyrin IX and Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester into Mg-2,4-divinylpheoporphyrin a5. Plant Physiol. 70:987–993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gough SP, Petersen BO, Duus JØ. 2000. Anaerobic chlorophyll isocyclic ring formation in Rhodobacter capsulatus requires a cobalamin cofactor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6908–6913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walker CJ, Mansfield KE, Smith KM, Castelfranco PA. 1989. Incorporation of atmospheric oxygen into the carbonyl functionality of the protochlorophyllide isocyclic ring. Biochem. J. 257:599–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bollivar DW, Beale SI. 1996. The chlorophyll biosynthetic enzyme Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethyl ester (oxidative) cyclase: characterization and partial purification from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii and Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Plant Physiol. 112:105–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pinta V, Picaud M, Reiss-Husson F, Astier C. 2002. Rubrivivax gelatinosus acsF (previously orf358) codes for a conserved, putative binuclear-iron-cluster-containing protein involved in aerobic oxidative cyclization of Mg-protoporphyrin IX monomethylester. J. Bacteriol. 184:746–753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ouchane S, Steunou A-S, Picaud M, Astier C. 2004. Aerobic and anaerobic Mg-protoporphyrin monomethyl ester cyclases in purple bacteria. A strategy adopted to bypass the repressive oxygen control system. J. Biol. Chem. 279:6385–6394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Minamizaki KK, Mizoguchi TT, Goto TT, Tamiaki HH, Fujita YY. 2008. Identification of two homologous genes, chlAI and chlAII, that are differentially involved in isocyclic ring formation of chlorophyll a in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. J. Biol. Chem. 283:2684–2692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moseley JL, Page MD, Alder NP, Eriksson M, Quinn J, Soto F, Theg SM, Hippler M, Merchant S. 2002. Reciprocal expression of two candidate di-iron enzymes affecting photosystem I and light-harvesting complex accumulation. Plant Cell 14:673–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tottey S, Block MA, Allen M, Westergren T, Albrieux C, Scheller HV, Merchant S, Jensen PE. 2003. Arabidopsis CHL27, located in both envelope and thylakoid membranes, is required for the synthesis of protochlorophyllide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:16119–16124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang K-H, Wen J, Li X, Blankenship RE. 2009. Role of the AcsF protein in Chloroflexus aurantiacus. J. Bacteriol. 191:3580–3587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Raimond J, Blankenship RE. 2004. Biosynthetic pathways, gene replacement and the antiquity of life. Geobiology 2:199–220 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boldareva EN, Bryantseva IA, Tsapin A, Nelson K, Sorokin DY, Tourova TP, Boichenko VA, Stadnichuk IN, Gorlenko VM. 2007. The new bacteriochlorophyll a-containing bacterium Roseinatronobacter monicus sp. nov. from the hypersaline soda lake (Mono Lake, California, United States). Microbiology 76:82–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boldareva EN, Akimov VN, Boichenko VA, Stadnichuk IN, Moskalenko AA, Makhneva ZK, Gorlenko VM. 2008. Rhodobaca barguzinensis sp. nov., a new alkalophylic purple nonsulfur bacteria isolated from soda lake on the Barguzin valley (Buryat Republic, Russia). Microbiology 77:206–218 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koblížek M, Béjà O, Bidigare RR, Christensen S, Benetiz-Nelson B, Vetriani C, Kolber MK, Falkowski PG, Kolber ZS. 2003. Isolation and characterization of Erythrobacter sp. strains from the upper ocean. Arch. Microbiol. 180:327–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Oz A, Sabehi G, Koblížek M, Massana R, Béjà O. 2005. Roseobacter-like bacteria in Red and Mediterranean Sea aerobic anoxygenic photosynthetic populations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:344–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rontani J-F, Christodoulous S, Koblížek M. 2005. GC-MS structural characterization of fatty acids from marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. Lipids 40:97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Koblížek M, Mlčoušková J, Kolber Z, Kopecký J. 2010. On the photosynthetic properties of marine bacterium COL2P belonging to Roseobacter clade. Arch. Microbiol. 192:41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zheng Q, Zhang R, Koblížek M, Boldareva EN, Yurkov V, Yan S, Jiao N. 2011. Diverse arrangement of photosynthetic gene clusters in aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria. PLoS One 6:e25050 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peter E, Salinas A, Wallner T, Jeske D, Dienst D, Wilde A, Grimm B. 2009. Differential requirement of two homologous proteins encoded by sll1214 and sll1874 for the reaction of Mg protoporphyrin monomethylester oxidative cyclase under aerobic and micro-oxic growth conditions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1787:1458–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Battistuzzi FU, Feijao A, Hedges SB. 2004. A genomic timescale of prokaryote evolution: insights into the origin of methanogenesis, phototrophy, and the colonization of land. BMC Evol. Biol. 4:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnston DT, Wolfe-Simon F, Pearson A, Knoll AH. 2009. Anoxygenic photosynthesis modulated Proterozoic oxygen and sustained Earth's middle age. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106:16925–16929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bollivar DW. 2003. Intermediate steps in chlorophyll biosynthesis, p 49–70 In Kadish K, Smith KM, Guillard R. (ed), The porphyrin handbook. Academic Press, San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]