Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have emerged as a novel class of endogenous, small, non-coding RNAs that negatively regulate over 30% of genes in a cell via degradation or translational inhibition of their target mRNAs. Functionally, an individual miRNA is important as a transcription factor because it is able to regulate the expression of its multiple target genes. Recent studies have identified that miRNAs are highly expressed in vasculature and their expression is deregulated in diseased vessels. miRNAs are found to be critical modulators for vascular cell functions such as cell differentiation, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis. Accordingly, miRNAs are involved in the angiogenesis and in the pathogenesis of vascular diseases. miRNAs may serve as novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for vascular disease. This review article summarizes the research progress regarding the roles of miRNAs in vascular biology and vascular disease.

Keywords: MicroRNAs, Gene Regulation, Vascular Biology, Vascular Disease

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of endogenous, small, non-coding RNAs that can pair with sites in 3′ untranslated regions in mRNAs of protein-coding genes to downregulate their expression [1]. miRNAs are initially transcribed by RNA polymerase II (Pol II) in the nucleus to form large pri-miRNA transcripts. The pri-miRNAs are processed by the RNase III enzymes, Drosha and Dicer, to generate 18- to 24-nucleotide mature miRNAs [1]. The first miRNA, lin-4, was discovered in Caenorhabditis elegans in 1993 [2, 3]. The presence of miRNAs in vertebrates was confirmed in 2001 [4]. Currently, more than 800 miRNAs have been cloned and sequenced in human [5], and the estimated number of miRNA genes is as high as 1,000 in the human genome [6]. More importantly, one miRNA is able to regulate the expression of multiple genes because it can bind to its mRNA targets as either an imperfect or a perfect complement. Thus, a miRNA can be functionally as important as a transcription factor [7]. As a group, miRNAs may directly regulate at least 30% of the genes in a cell [8]. It is therefore not surprising that miRNAs are involved in the regulation of all major cellular functions [9].

It is well established that vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, post-angioplasty restenosis, transplantation arteriopathy, and diabetic vascular complication are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in developed countries. In addition, angiogenesis is a common vascular consequence in many diseases including cancer [10], atherosclerosis [11], and ischemic heart disease [12]. Cell differentiation, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs) are critical cellular events responsible for the development of angiogenesis and vascular disease. Recent studies have demonstrated that miRNAs are highly expressed in vascular walls and their expression is deregulated in diseased vessels [13–15]. miRNAs are found to play important roles in angiogenesis and vascular disease via regulating vascular cell differentiation, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis through their target genes [13–18]. The current review article is for summarizing the research progress regarding the roles of miRNAs in vascular biology and vascular disease.

miRNAs in Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis is an important mechanism for the maintenance of adequate blood supply to the tissues both in normal development and in the process of diseases such as ischemic heart disease, cancer, and atherosclerosis [10–12]. The first evidence showing miRNAs in the regulation of angiogenesis came from Dicer knockout mice [17]. Dicer is a critical enzyme for miRNA synthesis [17]. These Dicer-deficient mice died early during development due to the thinning of vascular walls and severe disorganization of the network of blood vessels [17]. Similarly, knockdown of Dicer in both human and animal vascular ECs via RNAi approach significantly reduced EC migration, capillary sprouting, and tube formation [18]. Dicer knockout and knockdown accompanied the expression changes of a number of angiogenesis-related genes including vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, tek-TIE-2, Tie-1, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and interleukin-8 [17, 18].

The above phenotypic change in angiogenesis observed in these Dicer-deficient animals and ECs led to an explosion in studying the biological roles of individual miRNAs in EC biology and angiogenesis. In this respect, Poliseno et al. [16] identified that miR-221 and miR-222 had significant inhibitory effects on EC migration, tube formation, and wound healing in cultured ECs. These investigators further identified that miR-221/miR-222-med-itaed effects on ECs occurred, at least in part, through their target gene, c-Kit. More recently, a series of studies were conducted by different research groups in this new research area to identify the angiogenesis-related miRNAs [18–30]. Based on the results, these miRNAs can be divided into two groups: pro-angiogenic miRNAs or anti-angiogenic miR-NAs. Pro-angiogenic miRNAs include miR-126 [19, 20], miR-17-92 [21], Let-7 [17], miR-130a [22], miR-210 [23], miR-378 [24], and miR-296 [25]. In contrast, the current known anti-angiogenic miRNAs include miR-221/222 [16, 26, 27], miR-328 [28], miR-92a [29], and miR-214 [30]. The currently identified angiogenesis-related miRNAs and their target genes are listed in Table 1. It should be noted that the effects of these miRNAs on EC biology and angiogenesis are not only identified in cultured ECs in vitro but also in ischemia-induced angiogenesis in vivo using limb ischemia and myocardial infarction models [20, 29].

Table 1.

Angiogenesis-related miRNAs and their target genes

| Pro-angiogenic miRNA | Target genes | Anti-angiogenic miRNAs | Target genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-126 | Spred1, PIK3R2/p85-beta, VEGF, FGF | miR-221 | c-kit |

| miR-17-92 | Tsp1, CTGF | miR-222 | c-kit |

| Let-7 | thrombospondin-1 | miR-328 | CD44 |

| miR-130a | GAX, HOXA5 | miR-92a | integrin subunit alpha5 |

| miR-210 | Ephrin-A3 | miR-214 | eNOS |

| miR-378 | SuFu, Fus-1 | ||

| miR-296 | HGS |

miRNAs in Vascular Disease

The formation of neointimal lesions is a common pathological feature of diverse vascular diseases. It is well established that neointimal formation is resulted from EC injury and activation followed by white blood cell infiltration, lipid deposition, and VSMC dedifferentiation, proliferation, and migration in the vascular walls. Ji et al. [13] were the first group to identify the potential involvement of miRNAs in vascular neointimal growth. Using microarray analysis, these investigators demonstrated that miRNAs were highly expressed in normal rat arteries. Interestingly, in vascular walls with neointimal growth induced by balloon-catheter angioplasty, many of the detected miRNAs are aberrantly expressed [13]. The broadly deregulated miRNAs in injured arteries indicated that multiple miRNAs are involved in vascular injury responses that match the complex feature of neointimal growth in diverse vascular diseases in which multiple genes participated. The aberrant expression of miRNA was not limited to rat model. In mouse arteries with neointimal growth after ligation injury, both miR-143 and miR-145 were downregulated as reported by Cordes et al. [31] and our group [32]. Moreover, in atherosclerotic human and mouse arteries without mechanical injuries, some of miRNAs were also deregulated as demonstrated in recent reports by Elia et al. [33] as well as our group [32]. Table 2 shows the miRNAs that are highly expressed in vascular walls and are aberrantly expressed in animal and human arteries with neointimal lesion formation. The putative cellular functions of these miRNAs are also listed (Table 2).

Table 2.

Aberrantly expressed miRNAs in diseased vascular walls and their potential cellular functions

| Upregulated miRNAs | Putative cellular functions | Downregulated miRNAs | Putative cellular functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | Anti-apoptosis, anti-proliferation | miR-125a | Anti-proliferation |

| miR-31 | Pro-proliferation, anti-metastasis | miR-125b | Anti-proliferation |

| miR-146 | Anti-inflammation | miR-133a | Anti-proliferation, anti-fibrosis, pro-differentiation |

| miR-221 | Anti- or pro-proliferation, Anti- or pro-migration | miR-143 | Anti-proliferation |

| miR-222 | Anti- or pro-proliferation, Anti- or pro-migration | miR-145 | Pro-differentiation, anti-proliferation |

| miR-352 | n/a | miR-347 | n/a |

| miR-365 | n/a |

VSMC dedifferentiation, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis are critical cellular events responsible for the development of a number of proliferative vascular diseases. Indeed, VSMCs are the major cells within neointimal lesions in these vascular diseases. The biological roles of miRNAs in VSMCs have been identified by recent studies [13, 14, 32–35]. We demonstrated that miR-21, a miRNA that is upregulated in vascular walls with neointima, was a critical regulator for VSMC proliferation and apoptosis [13]. In cultured cells, upregulation of miR-21 via pre-miR-21 resulted in an increased VSMC proliferation, but decreased VSMC apoptosis. In contrast, VSMC proliferation was decreased, but apoptosis was increased via miR-21 inhibition through its inhibitor. In addition, we identified that the target genes of miR-21 involved in miR-21-mediated cellular effects on VSMCs were phosphatase and tensin homology deleted from chromosome 10 (PTEN)[13] and programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4)[32]. In our study targeting miR-221/222, we identified that miR-221/222 were critical pro-proliferative miRNAs in cultured VSMCs via their target genes, p27(Kip1) and p57(Kip2) [14]. The proliferative effect of miR-221/222 on VSMCs was further confirmed by another independent research group in which Davis et al. demonstrated that miR-221 increased the proliferation and migration of VSMCs through its target gene, p27(Kip1) [33].

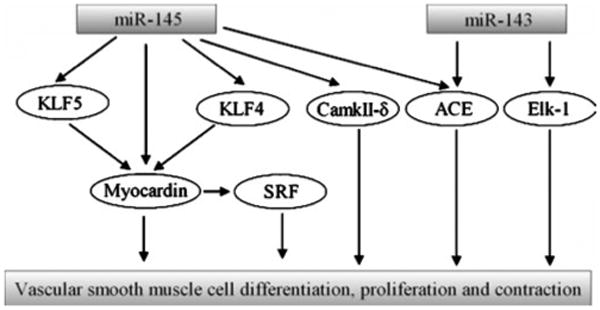

More recently, the roles of miR-145 and miR-143 in VSMC biology have received special attention because they are abundant miRNAs in normal vascular walls and their expression is downregulated in diseased arteries [13, 15, 31–33, 36, 37]. We identified that miR-145 was selectively expressed in VSMCs of arterial walls and its expression was significantly downregulated in differentiated, proliferative VSMCs [15]. Both in cultured cells in vitro and in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries in vivo, we demonstrated that miR-145 was a novel biomarker and a critical modulator for VSMC phenotype [15]. Indeed, the expression of miR-145 was consistent with that of VSMC differentiation maker genes, SM α-actin, calponin, and SM-MHC. Moreover, the expression of VSMC differentiation maker genes was significantly upregulated by overexpression of miR-145, but was downregulated by miR-145 inhibition. Furthermore, VSMC proliferation was inhibited by miR-145 overexpression via pre-miR145. To determine the potential gene targets of miR-145 in VSMCs, both bioinformatic and experimental approaches were applied. We identified that Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) was one of the critical target genes responsible for miR-145-mediated cellular effects on VSMCs [15]. Although Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) was also a potential target gene of miR-145 in VSMCs, the time course change of its expression in cultured VSMCs after PDGF stimulation and in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries did not match perfectly with the expression change of miR-145 [32]. Thus, the role of KLF4 in miR-145-mediated biological effects on VSMCs should be further studied. The role of miR-145 in VSMC biology was further confirmed by Cordes et al. [31]. These investigators demonstrated that KLF4 and calmodulin kinase IIdelta (CamkIIδ) are two target genes of miR-145 in VSMCs [31]. In addition, they also found that myocardin may be a direct target gene of miR-145 in VSMCs. However, in contrast to the inhibitory effect of a miRNA on its target genes, overexpression of miR-145 increased the expression of myocardin. We also found that the expression of myocardin was increased in miR-145-overexpressed VSMCs [15]. However, our explanation was that at least in part, the upregulated myocardin is induced by an indirect effect of miR-145 through its target gene KLF5 [15]. If myocardin is indeed a direct target of miR-145 but the expression is increased by miR-145, it could be a new discovery because recent studies revealed that some small RNAs may be able to increase their target gene expression via RNA activation mechanisms (RNAa) [38]. In addition to the above studies, Boettger et al. [36] identified that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is also a target gene of miR-145 related to its biological effect on VSMCs. More excitedly, miR-145 was found to play a critical role in keeping the contractive functions of VSMCs and vessels [36], which matched our finding regarding the role of miR-145 in VSMC phenotype. miR-143 is another important miRNA in VSMC biology [31, 33, 36, 37]. It was found that miR-143 was an important regulator for proliferation and contractive function of VSMC by targeting Elk-1 [31] and ACE [36]. The roles of miR-143 and miR-145 in VSMC biology were further verified by miR-143/145 knockout approach [33, 36, 37]. Boettger et al. [36] demonstrated that VSMCs from miR-143/145-deficient mice were locked in the synthetic state (dedifferentiated phenotype), which incapacitated their contractile abilities. The incomplete differentiation of VSMCs in miR-143/145-deficient mice was also demonstrated by Condorelli's group [33]. Disarray of actin stress fibers of VSMCs in miR-143/145-deficient mice was identified by Xin et al. [37]. In addition, decreased blood pressure was found in these miR-143/145-deficient mice due to the decreased contractile abilities of the vessels [36, 37]. The biological roles of miR-143/145 in VSMCs and their identified targets were summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell functions by miR-143 and miR-145. miR-143 and miR-145 are two abundant miRNAs in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5), Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), myocardin, and calmodulin kinase IIdelta (CamkIIδ) are found to be the target genes of miR-145, whereas Elk-1 is a target gene of miR-143 within VSMCs. In addition, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is target gene for both miR-143 and miR-145. These targets are able to regulate VSMC cell differentiation, proliferation, and contraction directly or indirectly via interaction with serum response factor (SRF)

miR-126 is also a well-studied miRNA in vascular biology. In addition to its critical roles in angiogenesis and vascular integrity by targeting Spred1, PIK3R2/p85-beta, VEGF, and FGF [19, 20, 39–41], miR-126 may also be a regulator for EC activation and vascular inflammation via its target, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1).

The effects of miRNAs on vascular disease have recently been intensively explored [13–15, 36–38, 42]. We demonstrated that miR-21, miR-221/222, and miR-145 were deregulated in balloon-injured rat carotid arteries [13–15]. Inhibition of the upreguated miR-21 [13] and miR-221/222 [14] inhibited vascular neointimal growth. In addition, the neointimal formation in carotid arteries was also significantly reduced by restoration of miR-145 after angioplasty [15]. The negative effect of miR-145 on vascular neointimal growth was also demonstrated in another study using the same rat model [33]. More recently, the role of miR-143/145 in neointimal formation was further confirmed using gene knockout approach in which Boettger et al. [36] found that spontaneous huge neointimal lesion formation was displayed in arteries from miR-143/145 knockout mice without any additional injuries. However, Xin et al. [37] reported that neointimal formation after carotid artery ligation injury was decreased in these miR-143/145 knockout mice. Obviously the result was different from that obtained in Dr. Braun's study [36] and also different from our unpublished data in mouse carotid artery guide-wire injury and air drying injury models using the pharmacological approaches. The mechanism for the different results is unclear. We think it might be related to the following reasons: First, miR-143/145 knockout may affect the normal development of VSMCs and vessels; thus, the real direct effect of miR-145 on vascular neointimal growth is affected. Thus, inducible miR-143/145 knockout should be needed to overcome the pitfall of the regular knockout approach. Second, neointimal formation in ligation model is dependent on the distance to the ligation site, which is difficult for the correct histological analysis. In addition, the neointimal response in carotid artery ligation model often has big difference even among the same group. Other injury models such as air dying injury and guide-wire injury (guide-wire injury should be performed in ApoE mice) should be tested in these knockout mice. More recently, Zernecke et al. [42] demonstrated that delivery of miR-126 by apoptotic body limited atherosclerosis, promoted the incorporation of Sca-1+ progenitor cells, and conferred features of plaque stability in mouse models of atherosclerosis via CXCL12-dependent mechanisms.

Genetic variations of pre-miRNAs, mature miRNAs, and their target genes determined by gene polymorphisms and single-nucleotide polymorphisms have revealed that the variations of pre-miRNAs, mature miRNAs, and miRNA binding sites in their target genes are related to many human diseases such as cancer and heart disease [43–45]. It is well known that polymorphism ss52051869 in the 3′UTR of human SLC7A1 with the binding sites of miR-122 is related to human hypertension [46]. Polymorphism study revealed that the variants of the miR-122 binding sites of 3′ UTR3′UTR in SLC7A1 might be related to the development of hypertension in human [46]. More polymorphism studies on miRNAs and their targets involved in vascular diseases should be performed.

Unlike cancer tissues, human vessel tissues with vascular diseases are not easy to be obtained. However, exciting results from animal studies have revealed that many critical genes related to vascular diseases are regulated by miRNAs. Some miRNAs have strong effects on vascular cell functions and vascular lesions in animals. Limited human atherosclerotic studies have also revealed that multiple miRNAs are deregulated [32, 33]. Clearly, more clinical studies should be performed using human vessel tissues. In addition, human miRNA studies using blood cells isolated from patients with vascular diseases could be an alternative approach for the clinical studies in this area.

Conclusion and Perspective

miRNAs in vascular biology and vascular disease has emerged as a new research area. The initial exciting results have demonstrated that multiple miRNAs are involved in the development of both human and animal vascular diseases via regulating vascular cell differentiation, migration, proliferation, and apoptosis through their target genes. Several in vivo animal studies have revealed the promising therapeutic results in vascular disease. Thus, miRNAs may represent new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for diverse vascular diseases. miRNA-based therapy may have both advantages and disadvantages. As we know well, the vascular diseases are multifactorial complex diseases in which many genes are involved. miRNA-based therapy may have some advantages compared with those for other molecular targets because one endogenous miRNA can target its multiple target genes. On the other hand, multiple target genes might induce some unexpected side effects, and this could be the disadvantage [47]. However, as miRNAs are endogenous, restoration of the aberrantly expressed miRNAs to the physiological levels should not have major unexpected side effects.

miRNAs are aberrantly expressed in vascular diseases, some being upregulated and others downregulated. Thus, two major miRNA-based therapeutic strategies are restoring the expression of miRNAs reduced in diseases and, conversely, inhibiting overexpressed miRNAs. We should realize that we are still at the early stages in miRNA-based therapy. The following studies should be performed before it can be used in the clinic. First, the critical miRNAs responsible for the development of vascular diseases should be further identified. Second, the detailed cellular and molecular mechanisms of these critical miRNAs in the prevention and treatment of vascular diseases should be studied. Third, in addition to the biological effects of these miRNAs on ECs and VSMCs, their effects on other vascular disease-related cellular events should be identified. Fourth, although methods are available to downregulate miRNA in vivo, technology for upregulating miRNA in the vascular walls in vivo requires development. Finally, the potential side effects of miRNA-based therapy should be studied before application in the clinic.

Acknowledgments

The author's research was supported by a National Institutes of Health Grant (HL080133) and a grant from the American Heart Association (09GRNT2250567).

References

- 1.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75(5):843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75(5):855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294(5543):853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Friedman JM, Jones PA. MicroRNAs: Critical mediators of differentiation, development and disease. Swiss Medical Weekly. 2008;139(33–34):466–472. doi: 10.4414/smw.2009.12794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentwich I, Avniel A, Karov Y, Aharonov R, Gilad S, Barad O, et al. Identification of hundreds of conserved and nonconserved human microRNAs. Nature Genetics. 2005;37(7):766–770. doi: 10.1038/ng1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen K, Rajewsky N. The evolution of gene regulation by transcription factors and microRNAs. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8:93–103. doi: 10.1038/nrg1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang C. MicroRNomics: A newly emerging approach for disease biology. Physiological Genomics. 2008;33(2):139–147. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00034.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Paepe B. Anti-angiogenic agents and cancer: Current insights and future perspectives. Recent Patents on Anti-cancer Drug Discovery. 2009;4(2):180–185. doi: 10.2174/157489209788452821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Stefano R, Felice F, Balbarini A. Angiogenesis as risk factor for plaque vulnerability. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2009;15(10):1095–1106. doi: 10.2174/138161209787846892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smart N, Dubé KN, Riley PR. Coronary vessel development and insight towards neovascular therapy. International Journal of Experimental Pathology. 2009;90(3):262–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji R, Cheng Y, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen H, et al. MicroRNA expression signature and antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of MicroRNA in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circulation Research. 2007;100(11):1579–1588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.141986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu X, Cheng Y, Zhang S, Lin Y, Yang J, Zhang C. A necessary role of miR-222 and miR-221 in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal hyperplasia. Circulation Research. 2009;104(4):476–487. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.185363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheng Y, Liu X, Yang J, Lin Y, Xu D, Lu Q, et al. MicroRNA-145, a novel smooth muscle cell phenotypic marker and modulator, controls vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circulation Research. 2009;105:158–166. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.197517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poliseno L, Tuccoli A, Mariani L, Evangelista M, Citti L, Woods K, et al. MicroRNAs modulate the angiogenic properties of HUVECs. Blood. 2006;108:3068–3071. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-012369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuehbacher A, Urbich C, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Role of Dicer and Drosha for endothelial microRNA expression and angiogenesis. Circulation Research. 2007;101(1):59–68. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.153916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suárez Y, Fernández-Hernando C, Pober JS, Sessa WC. Dicer dependent microRNAs regulate gene expression and functions in human endothelial cells. Circulation Research. 2007;100(8):1164–1173. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265065.26744.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fish JE, Santoro MM, Morton SU, Yu S, Yeh RF, Wythe JD, et al. miR-126 regulates angiogenic signaling and vascular integrity. Developmental Cell. 2008;15(2):272–284. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Solingen C, Seghers L, Bijkerk R, Duijs JM, Roeten MK, van Oeveren-Rietdijk AM, et al. Antagomir-mediated silencing of endothelial cell specific microRNA-126 impairs ischemia-induced angiogenesis. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2009;13(8A):1577–1585. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, Murphy D, Sevignani C, Wentzel E, et al. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nature Genetics. 2006;38(9):1060–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Gorski DH. Regulation of angiogenesis through a microRNA (miR-130a) that down-regulates antiangiogenic homeobox genes GAX and HOXA5. Blood. 2008;111(3):1217–1226. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-104133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fasanaro P, D'Alessandra Y, Di Stefano V, Melchionna R, Romani S, Pompilio G, et al. MicroRNA-210 modulates endothelial cell response to hypoxia and inhibits the receptor tyrosine kinase ligand Ephrin-A3. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283(23):15878–15883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800731200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee DY, Deng Z, Wang CH, Yang BB. MicroRNA-378 promotes cell survival, tumor growth, and angiogenesis by targeting SuFu and Fus-1 expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(51):20350–20355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706901104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Würdinger T, Tannous BA, Saydam O, Skog J, Grau S, Soutschek J, et al. miR-296 regulates growth factor receptor overexpression in angiogenic endothelial cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(5):382–393. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y, Song YH, Li F, Yang T, Lu YW, Geng YJ. MicroRNA-221 regulates high glucose-induced endothelial dysfunction. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;381(1):81–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Minami Y, Satoh M, Maesawa C, Takahashi Y, Tabuchi T, Itoh T, et al. Effect of atorvastatin on microRNA 221 / 222 expression in endothelial progenitor cells obtained from patients with coronary artery disease. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;39(5):359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang CH, Lee DY, Deng Z, Jeyapalan Z, Lee SC, Kahai S, et al. MicroRNA miR-328 regulates zonation morphogenesis by targeting CD44 expression. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(6):e2420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonauer A, Carmona G, Iwasaki M, Mione M, Koyanagi M, Fischer A, et al. MicroRNA-92a controls angiogenesis and functional recovery of ischemic tissues in mice. Science. 2009;324(5935):1710–1713. doi: 10.1126/science.1174381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan LS, Yue PY, Mak NK, Wong RN. Role of MicroRNA-214 in ginsenoside-Rg1-induced angiogenesis. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009;38(4):370–377. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordes KR, Sheehy NT, White MP, Berry EC, Morton SU, Muth AN, et al. miR-145 and miR-143 regulate smooth muscle cell fate and plasticity. Nature. 2009;460(7256):705–710. doi: 10.1038/nature08195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang C. MicroRNA-145 in vascular smooth muscle cell biology: A new therapeutic target for vascular disease. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(21):3469–3473. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elia L, Quintavalle M, Zhang J, Contu R, Cossu L, Latronico MV, et al. The knockout of miR-143 and -145 alters smooth muscle cell maintenance and vascular homeostasis in mice: Correlates with human disease. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2009;16(12):1590–1598. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin Y, Liu X, Cheng Y, Yang J, Huo Y, Zhang C. Involvement of microRNAs in hydrogen peroxide-mediated gene regulation and cellular injury response in vascular smooth muscle cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(12):7903–7913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806920200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis BN, Hilyard AC, Nguyen PH, Lagna G, Hata A. Induction of microRNA-221 by platelet-derived growth factor signaling is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle phenotype. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284(6):3728–3738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808788200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boettger T, Beetz N, Kostin S, Schneider J, Krüger M, Hein L, et al. Acquisition of the contractile phenotype by murine arterial smooth muscle cells depends on the Mir143/145 gene cluster. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2009;119(9):2634–2647. doi: 10.1172/JCI38864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xin M, Small EM, Sutherland LB, Qi X, McAnally J, Plato CF, et al. MicroRNAs miR-143 and miR-145 modulate cytoskeletal dynamics and responsiveness of smooth muscle cells to injury. Genes & Development. 2009;23(18):2166–2178. doi: 10.1101/gad.1842409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pushparaj PN, Aarthi JJ, Kumar SD, Manikandan J. RNAi and RNAa—The yin and yang of RNAome. Bioinformation. 2008;2(6):235–237. doi: 10.6026/97320630002235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang S, Aurora AB, Johnson BA, Qi X, McAnally J, Hill JA, et al. The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Developmental Cell. 2008;15(2):261–271. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhnert F, Mancuso MR, Hampton J, Stankunas K, Asano T, Chen CZ, et al. Attribution of vascular phenotypes of the murine Egfl7 locus to the microRNA miR-126. Development. 2008;135(24):3989–3993. doi: 10.1242/dev.029736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2008;105(5):1516–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zernecke A, Bidzhekov K, Noels H, Shagdarsuren E, Gan L, Denecke B, et al. Delivery of microRNA-126 by apoptotic bodies induces CXCL12-dependent vascular protection. Science Signaling. 2009;2(100):ra81. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishra PJ, Mishra PJ, Banerjee D, Bertino JR. MiRSNPs or MiR-polymorphisms, new players in microRNA mediated regulation of the cell: Introducing microRNA pharmacogenomics. Cell Cycle. 2008;7(7):853–858. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang M, Ye Y, Qian H, Song Z, Jia X, Zhang Z, et al. Common genetic variants in pre-microRNAs are associated with risk of coal workers' pneumoconiosis. Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;55(1):13–17. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sethupathy P, Collins FS. MicroRNA target site polymorphisms and human disease. Trends in Genetics. 2008;24(10):489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Z, Kaye DM. Mechanistic insights into the link between a polymorphism of the 3′ UTR of the SLC7A1 gene and hypertension. Human Mutation. 2009;30(3):328–333. doi: 10.1002/humu.20891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fluiter K, Mook OR, Baas F. The therapeutic potential of LNA-modified siRNAs: Reduction of off-target effects by chemical modification of the siRNA sequence. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2009;487:189–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-547-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]