Abstract

Objectives To determine the long term clinical effectiveness of laparoscopic fundoplication as an alternative to drug treatment for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).

Design Five year follow-up of multicentre, pragmatic randomised trial (with parallel non-randomised preference groups).

Setting Initial recruitment in 21 UK hospitals.

Participants Responders to annual questionnaires among 810 original participants. At entry, all had had GORD for >12 months.

Intervention The surgeon chose the type of fundoplication. Medical therapy was reviewed and optimised by a specialist. Subsequent management was at the discretion of the clinician responsible for care, usually in primary care.

Main outcome measures Primary outcome measure was self reported quality of life score on disease-specific REFLUX questionnaire. Other measures were health status (with SF-36 and EuroQol EQ-5D questionnaires), use of antireflux medication, and complications.

Results By five years, 63% (112/178) of patients randomised to surgery and 13% (24/179) of those randomised to medical management had received a fundoplication (plus 85% (222/261) and 3% (6/192) of those who expressed a preference for surgery and for medical management). Among responders at 5 years, 44% (56/127) of those randomised to surgery were taking antireflux medication versus 82% (98/119) of those randomised to medical management. Differences in the REFLUX score significantly favoured the randomised surgery group (mean difference 8.5 (95% CI 3.9 to 13.1), P<0.001, at five years). SF-36 and EQ-5D scores also favoured surgery, but were not statistically significant at five years. After fundoplication, 3% (12/364) had surgical treatment for a complication and 4% (16) had subsequent reflux-related operations—most often revision of the wrap. Long term rates of dysphagia, flatulence, and inability to vomit were similar in the two randomised groups.

Conclusions After five years, laparoscopic fundoplication continued to provide better relief of GORD symptoms than medical management. Adverse effects of surgery were uncommon and generally observed soon after surgery. A small proportion had re-operations. There was no evidence of long term adverse symptoms caused by surgery.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN15517081.

Introduction

Trials of laparoscopic fundoplication surgery1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 provide promising evidence of better short term symptomatic relief than continued medical management among people who would otherwise require continuous or intermittent medication for reasonable control of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Uncertainty remains about whether benefits are sustained and outweigh risks, subsequent drug use, and unwanted symptoms such as dysphagia and flatulence.7 We therefore undertook five year follow-up within a multicentre, UK based, randomised controlled trial, the REFLUX trial.

Methods

Design and participants

The study was approved by the Scotland A Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC/00/0/30). The design and one year results have been reported previously,1 2 9 and a detailed report of the follow-up is also available.10 The trial was pragmatic11 comparing a policy of laparoscopic fundoplication with a policy of optimised continued medical management. Patients were eligible if they had more than 12 months’ maintenance treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (or alternative) for reasonable control of GORD symptoms, they had evidence of GORD (endoscopic or 24 hour pH monitoring, or both), they were suitable for either policy, and the recruiting doctor was uncertain which management policy to follow.

Clinical management

Participating clinical centres had partnerships between surgeons and gastroenterologists who shared the secondary care of patients with GORD. They assessed eligibility and, working with research nurses, informed participants about the trial. Randomisation was organised centrally and computer generated. Participants who declined to take part in the randomised trial because of a strong preference either for remaining on medical management or for undergoing surgery were then given the opportunity to join one of two non-randomised preference arms.12 All participants gave informed consent.

For all participants in either the randomised or preference surgical groups, surgery could be deferred or declined after trial entry, by either the patient or the surgeon. A lead surgeon who had performed at least 50 laparoscopic fundoplication operations (or a surgeon working under supervision) undertook the surgery. The type of fundoplication was decided by the surgeon. We considered the different fundoplication techniques as a single policy. Those allocated to medical treatment had their treatment reviewed and adjusted as judged best by a local gastroenterologist.13 The medical protocol included the option of surgery if a clear indication developed after randomisation. In all groups, subsequent management was decided by the clinician responsible for care; most later care was in general practice.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the score from the REFLUX questionnaire,14 a validated measure of health related quality of life for patients with GORD that incorporates assessment of reflux related and other gastrointestinal symptoms and the side effects and complications of both treatments (scores ranged from 0 to 100, with the higher the score the better the patient felt). Other measures were health status (SF-3615 and EuroQol EQ-5D16), use of antireflux drugs, reflux related surgery and its complications, and individual symptoms. Participants were followed up by postal questionnaire (copies available on request) at equivalent to 3 and 12 months after surgery, and subsequently annually for five years.

Sample size and statistical analysis

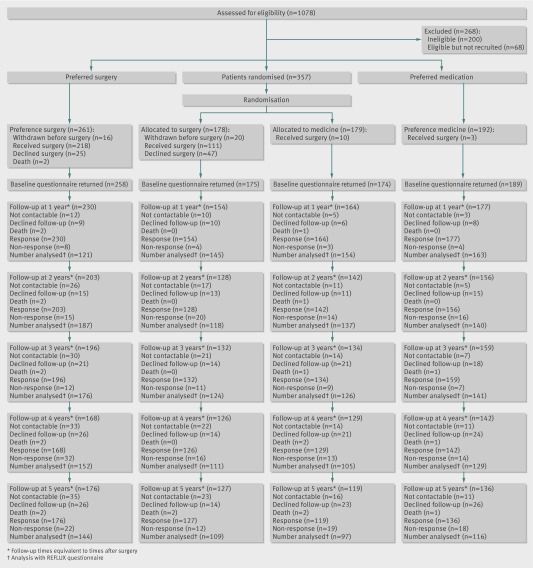

The original sample size of 176 per group was chosen to give 80% power (α=0.05) to detect a difference of 0.3 of one standard deviation (equivalent to 7 points) in the REFLUX questionnaire score. Secure randomisation was organised centrally using a computer generated sequence, stratified by clinical site, with balance in age, sex, and body mass index secured by minimisation.2 There was no subsequent blinding. Figure 1 summarises the stages of the study in a CONSORT diagram.

Fig 1 Consort diagram of flow of participants through study

Primary statistical analysis in the randomised comparison was by intention to treat. The REFLUX questionnaire score, SF-36, EQ-5D, and antireflux drug use were analysed using general linear models. The analyses were adjusted for the minimisation covariates; in addition, the randomised comparisons were also adjusted for baseline REFLUX questionnaire scores and for baseline by treatment interaction. Sensitivity to assumptions about missing values was explored using a repeated measures analysis.17 Secondary “adjusted treatment received” analyses 18 were based on actual treatment in the first year. These are similar to per protocol analyses but are less prone to bias; they give a measure of efficacy of surgery when compared with medical management.

Results

Recruitment took place in 21 UK centres between March 2001 and June 2004: 357 patients recruited to the randomised comparison (178 to surgery and 179 to medical management) and 453 recruited to non-randomised preference groups (261 for surgery and 192 for medical management).

Description of trial groups

As described previously,1 2 the randomised groups were balanced at trial entry. Follow-up rates decreased over time (318/357 (89%) at 1 year to 246/357 (69%) at 5 years). Four randomised participants are known to have died by five years—none related to trial participation. Respondents at five years tended to have been older at entry, to have been prescribed medication for a shorter time before recruitment, and to have had higher baseline quality of life scores. However, other than in baseline body mass index (table 1), respondents at five years were similar in the two randomised groups. The baseline characteristics of the randomised groups lay between those of the preference groups: members of the group who expressed a preference for surgery were younger, had been prescribed drugs for GORD for longer, and had lower baseline REFLUX scores; participants who preferred medical treatment were older, more likely to be women, had been prescribed medication for a shorter time, and had higher baseline REFLUX scores.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of respondents at five year follow-up by randomisation to surgical or medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Values are numbers (percentages) of participants unless stated otherwise

| Characteristic | Surgical (n=127 maximum) | Medical (n=119 maximum) | P value of difference* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age in years | 48.5 (9.3) (n=127) |

46.4 (11.6) (n=119) |

0.12 |

| Sex: | |||

| Men | 79/127 (62) | 76/119 (64) | 0.79 |

| Women | 48/127 (38) | 43/119 (36) | — |

| Mean (SD) body mass index | 29.0 (4.3) (n=127) |

27.7 (3.8) (n=119) |

0.01 |

| Mean (SD) months of antireflux medication before trial entry | 57.2 (63.4) (n=124) |

46.3 (60.1) (n=117) |

0.17 |

| Erosive oesophagitis: | |||

| Yes | 63/111 (57) | 68/108 (63) | 0.35 |

| No | 48/111 (43) | 39/108 (36) | — |

| H pylori infection status: | |||

| Positive (treated) | 6/96 (6) | 10/92 (11) | 0.52 |

| Positive (untreated) | 1/96 (1) | 2/92 (2) | — |

| Negative | 55/96 (57) | 45/92 (49) | — |

| Uncertain | 34/96 (35) | 34/92 (37) | — |

| Hiatus hernia: | |||

| Yes | 73/117 (62) | 71/114 (62) | 0.99 |

| No | 44/117 (38) | 43/114 (38) | — |

| Mean (SD) questionnaire scores: | |||

| REFLUX† | 65.9 (23.7) (n=121) |

68.6 (24.0) (n=110) |

0.38 |

| EQ-5D‡ | 0.736 (0.223) (n=122) |

0.755 (0.228) (n=118) |

0.51 |

| SF-36 physical§ | 44.8 (10.0) (n=121) |

46.1 (9.1) (n=114) |

0.30 |

| SF-36 mental§ | 46.6 (11.0) (n=121) |

46.5 (11.1) (n=114) |

0.98 |

| Taking any proton pump inhibitor | 120/125 (96) | 109/118 (92) | 0.23 |

| Taking any antireflux drug | 124/125 (99) | 113/118 (96) | 0.11 |

*Using Student’s t test, χ2 test, or Fischer’s exact test as appropriate.

†REFLUX questionnaire a disease-specific measure of quality of life (score range 0–100).

‡EuroQol EQ-5D measure of health status.

§Short Form (36) Health Survey measure of health status.

Clinical management

By five years, 112 (62.9%) of the 178 patients randomised to surgery had received fundoplication (table 2)—53 (47.3%) with a total wrap and 59 (52.7%) with a partial wrap. Surgery was also performed for 24 (13.4%) of the 179 patients randomised to medical management—10 in the first year and 14 in years 2–5; post hoc analyses showed that these 24 had significantly lower baseline REFLUX questionnaire scores than those randomised to medical management who did not have surgery. Of the total of 364 patients who had fundoplication (randomised and preference groups), 16 (4.4%) had a subsequent reflux related reoperation—mainly a reconstruction of the same wrap or conversion to another type of wrap—and 12 (3.3%) had a late complication (table 2).

Table 2.

Reflux related surgery and subsequent complications among participants with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who were randomised to or selected surgical or medical management. Values are numbers (percentages) of participants

| Participants randomised to treatment | Participants with preferred treatment | Total cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical (n=178) | Medical (n=179) | Surgical (n=261) | Medical (n=192) | |||

| Fundoplication within 1 year of enrolment | 111 (62.4) | 10 (5.6) | 218 (83.5) | 3 (1.6) | ||

| Fundoplication at any time during 5 year follow-up | 112 (62.9) | 24 (13.4) | 222 (85.1) | 6 (3.1) | ||

| Reflux related re-operation: | 5 (4.5) | 1 (4.2) | 8* (4.5) | 2 (33.3) | 16 (4.4) | |

| Reconstruction of same wrap | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 6 | |

| Conversion of type of wrap | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 6 | |

| Reversal of fundoplication | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Repair of hiatus hernia only | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| Late postoperative complication†: | 2 (1.8) | 0 | 8 (3.6) | 2 (33.3) | 12 (3.3) | |

| Oesophageal dilatation or stricture dilatation | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | |

| Repair of incisional hernia | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Other | 1‡ | 0 | 2§ | 2¶ | 5 | |

*Two of the eight also had a third reflux related operation.

†Complication ≥1 month after operation.

‡Pain due to original wrap shifting.

§Admission for venous thromboembolism; pain from operation.

¶Hole between stomach and liver; bleed in stomach and/or bowel.

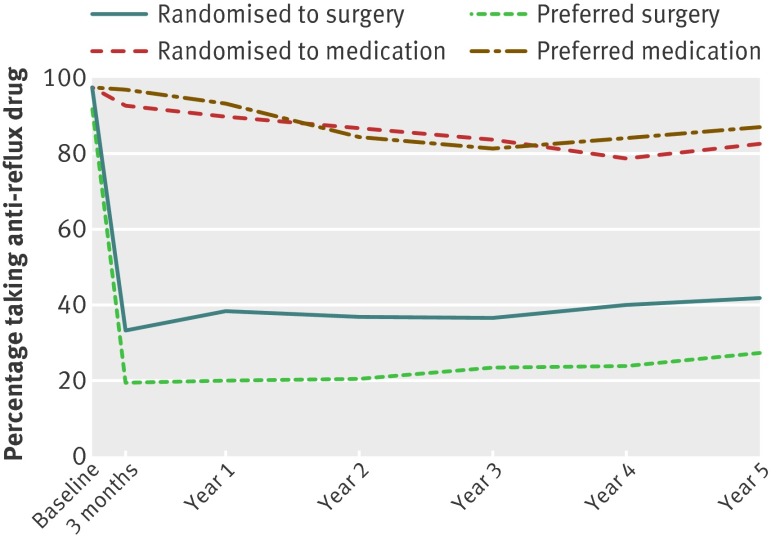

Figure 2 shows the use of antireflux drugs in the four participant groups based on intention to treat. This applied to 37.7% (58/178) of those randomised to surgery versus 90.2% (148/179) of those randomised to medical management at one year follow-up and to 44.1% (56/127) versus 82.4% (98/119) at five years. The equivalent rates among those randomised to surgery who had surgery in the first year were 9.6% (10/104) at one year rising to 26.7% (24/90) at five years. The most commonly prescribed proton pump inhibitors were omeprazole, lansoprazole, and esomeprazole.

Fig 2 Use of any antireflux drugs at baseline and at follow-up among participants with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who were randomised to or selected surgical or medical treatment

Health status and symptoms

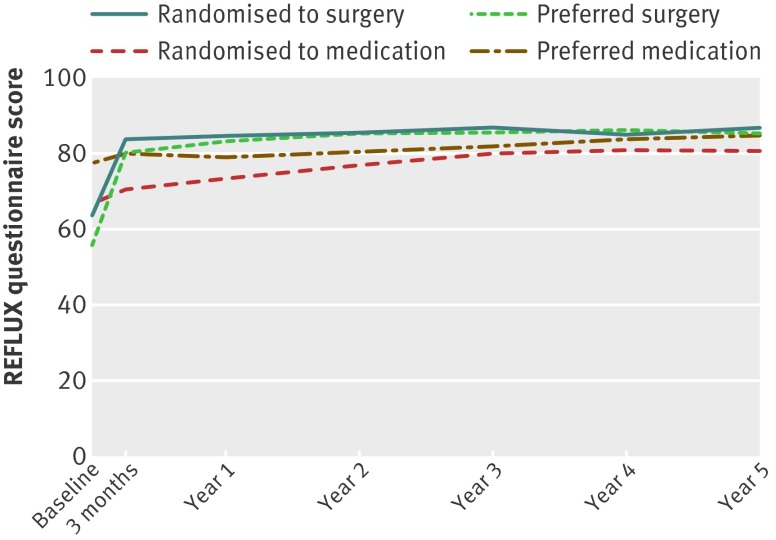

The REFLUX questionnaire mean scores at all follow-up time points were highest in the groups randomised to surgery or who preferred surgery (fig 3). The differences between the surgical and medical groups narrowed over time, principally because the scores for the group randomised to medical treatment improved over the first three years. However, there were still clear differences between the randomised groups at five years: mean difference 8.5 (95% confidence interval 3.9 to 13.1, P<0.001) for intention to treat, 11.5 (4.2 to 18.7, P=0.002) adjusted for treatment received; and 8.1 (4.4 to 11.7) for repeated measures analysis.

Fig 3 Mean REFLUX questionnaire score at baseline and at follow-up points among participants with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease who were randomised to or selected surgical or medical treatment. Scores range 0–100, the higher the score the better the participant felt

Heartburn, regurgitation, and belching were reported less frequently in the group randomised to surgery than among those randomised to medication, with no significant differences in ‘difficulty swallowing’, ‘wind from the bowel’ and ‘wanting to be sick but being unable’ (table 3).

Table 3.

Frequency of related symptoms among participants at three and five year follow-up after randomisation to surgical or medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Values are numbers (percentages) of participants

| Symptom frequency (No of times/week) |

Year 3 follow-up | Year 5 follow-up | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical | Medical | Surgical | Medical | ||

| Heartburn: | |||||

| 0 | 77 (58.8) | 46 (34.8) | 65 (58.6) | 28 (26.4) | |

| 1–3 | 44 (33.6) | 64 (48.5) | 38 (34.2) | 64 (60.4) | |

| >3 | 10 (7.6) | 22 (16.7) | 8 (7.2) | 14 (13.2) | |

| Regurgitation: | |||||

| 0 | 102 (77.3) | 83 (61.9) | 89 (75.4) | 71 (63.4) | |

| 1–3 | 27 (20.5) | 47 (35.1) | 26 (22.0) | 37 (33.0) | |

| >3 | 3 (2.3) | 4 (3.0) | 3 (2.5) | 4 (3.6) | |

| Difficulty swallowing: | |||||

| 0 | 100 (75.8) | 102 (76.1) | 91 (77.1) | 82 (74.5) | |

| 1–3 | 30 (22.7) | 27 (20.1) | 25 (21.2) | 25 (22.7) | |

| >3 | 2 (1.5) | 5 (3.7) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.7) | |

| Wind from bowel: | |||||

| 0 | 19 (14.4) | 20 (15.0) | 14 (11.9) | 14 (12.7) | |

| 1–3 | 37 (28.0) | 35 (26.3) | 27 (22.9) | 30 (27.3) | |

| >3 | 76 (57.6) | 78 (58.6) | 77 (65.3) | 66 (60.0) | |

| Belching: | |||||

| 0 | 53 (40.2) | 33 (24.8) | 46 (39.3) | 27 (24.5) | |

| 1–3 | 39 (29.5) | 48 (36.1) | 40 (34.2) | 37 (33.6) | |

| >3 | 40 (30.3) | 52 (39.1) | 31 (26.5) | 46 (41.8) | |

| Nausea but unable to be sick: | |||||

| 0 | 116 (87.9) | 110 (83.3) | 101 (85.6) | 92 (82.9) | |

| 1–3 | 15 (11.4) | 17 (12.9) | 15 (12.7) | 16 (14.4) | |

| >3 | 1 (0.8) | 5 (3.8) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.7) | |

SF-36 scores favoured the surgical group in all domains at all time points. Differences decreased over time, and this decrease is reflected in most P values being <0.05 up to three years’ follow-up, whereas at five years only the norm-based general health and role emotional domains had P values <0.05 (table 4). Mean EQ-5D scores showed a similar pattern—differences all favouring the surgical group but tending to narrow so that scores at years 2 and 3 were significantly different but not at later time points (table 4).

Table 4.

Differences at five year follow-up in self reported outcomes between participants randomised to surgery and those randomised to medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

| Intention to treat | Adjusted for treatment received | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (95% CI)* | P value | Mean difference (95% CI)* | P value | ||

| REFLUX total score† | 8.3 (3.2 to 13.4) | 0.001 | 11.6 (3.5 to 19.8) | 0.005 | |

| REFLUX symptom scores: | |||||

| General discomfort | 11.82 (6.50 to 17.14) | <0.001 | 15.59 (7.52 to 23.66) | <0.001 | |

| Wind and frequency | 3.34 (−1.98 to 8.66) | 0.218‡ | 5.12 (−3.50 to 13.73) | 0.243‡ | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 4.97 (1.53 to 8.41) | 0.005 | 7.32 (2.04 to 12.60) | 0.007 | |

| Activity limitation | 5.97 (2.03 to 9.91) | 0.003 | 8.27 (2.03 to 14.52) | 0.010 | |

| Constipation and swallowing | 2.54 (−2.09 to 7.18) | 0.281‡ | 4.11 (−3.40 to 11.62) | 0.282‡ | |

| SF-36 scores (norm based): | |||||

| Physical functioning | 2.01 (−0.26 to 4.28) | 0.082‡ | 3.35 (−0.33 to 7.03) | 0.074‡ | |

| Role physical | 0.57 (−2.10 to 3.24) | 0.674‡ | 1.14 (−3.20 to 5.47) | 0.606‡ | |

| Bodily pain | 1.52 (−0.90 to 3.94) | 0.218‡ | 1.65 (−2.25 to 5.54) | 0.406‡ | |

| General health | 2.76 (0.21 to 5.31) | 0.034 | 3.79 (−0.29 to 7.88) | 0.068‡ | |

| Vitality | 0.37 (−2.23 to 2.98) | 0.777‡ | 0.19 (−4.03 to 4.41) | 0.928‡ | |

| Social functioning | 1.72 (−1.05 to 4.49) | 0.221‡ | 2.36 (−2.13 to 6.84) | 0.301‡ | |

| Role emotional | 2.67 (0.07 to 5.27) | 0.044 | 4.56 (0.34 to 8.79) | 0.034 | |

| Mental health | 0.59 (−1.96 to 3.14) | 0.650‡ | 0.40 (−3.72 to 4.51) | 0.849‡ | |

| EQ-5D score | 0.047 (−0.013 to 0.108) | 0.126‡ | 0.069 (−0.029 to 0.167) | 0.168‡ | |

*Difference is surgery group minus medical group. Analyses adjusted for body mass index, age, sex, baseline score, and baseline-group interaction unless stated otherwise.

†REFLUX questionnaire a disease-specific measure of quality of life (score range 0–100).

‡Adjusted for body mass index, age, sex, and baseline score.

Preference groups

The preference surgery group had a markedly lower mean REFLUX score at baseline than the preference medical group (55.8 v 77.5, equivalent to 1 SD). Despite this, all subsequent scores favoured the preference surgery group (fig 3). Other quality of life scores showed a similar pattern.

Discussion

Principal findings

After five years, a policy of laparoscopic fundoplication among patients for whom reasonable control of GORD symptoms required long term medication and for whom both surgery and medical management were suitable continued to provide better relief of GORD symptoms with associated improved health related quality of life. Despite some narrowing over time, the difference in the primary outcome measure remained highly significant at five years. There was reassuringly little evidence of new chronic symptoms caused by surgery. Reoperations and complications of surgery occurred early after surgery and were uncommon.

Strengths and weaknesses of study

The trial design was pragmatic, aiming to make clinical management similar to normal NHS care, and so the results should be generalisable to standard care. The trial compared two policies for managing GORD (intention to treat analyses) rather than directly comparing surgery with antireflux medication. The first policy was earlier surgery for eligible patients, when deemed appropriate and acceptable, with the option to take medication if considered helpful. The second policy was continued, initially optimised, medical management, with “delayed” surgery in selected cases when considered indicated.

Recruiting patients for randomisation to such markedly differing managements as surgery and medical treatment is challenging. Patients who agree to be randomised have to be uncertain between the two approaches, and hence it should be expected that they sometimes change their minds once they discuss and reflect on the implications of their allocation. These circumstances are largely responsible for the apparently low rate of surgery among those randomly allocated surgery (112/178 (63%), table 1) compared with those who expressed a preference for surgery (218/261 (83%)). Among those allocated surgery who did not have surgery in the first year, a definite decision was later made not to have an operation for 47. For 25 of these, this was a clinical decision—most commonly the surgeon deciding after randomisation that surgery was not appropriate. Most of the others changed their minds about having surgery for a variety of work or home related reasons, because of worries about having surgery (after a fuller discussion with the surgeon), because of a wish to avoid unpleasant preoperative tests, or because their symptoms had improved. In addition to these 47, a further 20 withdrew for unknown reasons. There is no doubt that some of these participants experienced long delays before formally being offered surgery, and we believe that this was an important factor in their eventual decision not to have surgery after all. Recruitment and early treatment in the trial was conducted in 2001–4, when there was great pressure on surgical services in the NHS, and long delays for elective surgery for non-life threatening, benign conditions were common. (Average time between trial entry and surgery in the trial was 8–9 months.)

Despite only 63% of those allocated surgery actually receiving it, there were still clear differences in outcome between the intention to treat groups. However, the analyses adjusted for treatment received probably give better estimates of differential effects in the randomised comparison in terms of efficacy. As would be expected, these analyses gave larger estimates (11.5 v 8.5 for intention to treat), but they are more prone to bias.

The 69% response rate at five years is similar to the 67% reported for the LOTUS clinical trial.7 The responders in the randomised groups were generally similar in baseline characteristics (table 1). Although responders did show some differences from non-responders, it is reassuring that the repeated measures analysis that uses data from all follow-up points gave broadly similar results to the intention to treat analyses.

The 24 (13%) of the 179 participants randomised to medical management who subsequently had surgery had significantly lower baseline REFLUX questionnaire scores, which then improved markedly. This group contributed to the narrowing of differences over time between the two randomised groups (fig 1), and this is another reason why the analyses based on intention to treat are likely to underestimate the effects of surgery. Some participants did take medication intermittently. The estimated longer term use of antireflux drugs (fig 2) was based on participants’ recall of the preceding two weeks and may not fully reflect use over the entire year.

We anticipated that some eligible patients would have strong preferences for their future management, especially when clinical uncertainty was expressed. We gave these patients the opportunity to participate in non-randomised preference groups. These groups do aid the interpretation of the randomised trial results in important ways: they provide added data on rare but serious complications; they contextualise the randomised cohort (which sits between the preference groups in terms of baseline characteristics); they add further evidence of the effects of surgery (the preference surgery group started with much lower REFLUX questionnaire scores but had high scores after surgery); and they provide better guides to real world management in terms of surgical take up.

Comparison with other studies

Four randomised trials have compared laparoscopic fundoplication with medical management of GORD.1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 19 The REFLUX trial had the most pragmatic design—for example, greater flexibility in the choice of surgical procedure. Also, other trials incorporated regular specialist assessment of antireflux medication and adjustment, whereas in REFLUX, after initial review by a gastroenterologist, all subsequent prescription was decided by the clinician responsible for normal care, usually in primary care.

All four trials show significantly better relief of symptoms over their length of follow-up. Limited data are available for generic quality of life measures: while differences are less marked, they are consistent with benefit from surgery. The trials are also broadly consistent in showing small numbers of operations needing to be converted to an open procedure, visceral injuries associated with the procedure, postoperative problems, and numbers requiring dilatation of the wrap. The REFLUX trial suggests that 4.4% (16/364) have reoperations over five years, broadly consistent with other trials.

The REFLUX trial’s main outcomes were patient reported, providing “common currency” across trial policies independent of clinical judgment. In contrast, the primary outcome in the other large trial (LOTUS6 7) was “treatment failure” as judged by cross over to the alternative treatment—all surgical patients who developed a need for medication were classified into this category whether or not their GORD symptoms were satisfactorily controlled by that medication. A concern about using patient reported outcomes is that completion of questionnaires might be influenced by knowledge of management received, but this possibility is likely to become more remote as follow-up lengthens. Also, the randomised component was limited to patients who were uncertain which treatment to choose (those with strong views were enrolled into the preference groups).

Where the REFLUX trial results differ from those of the other trials, especially LOTUS,6 7 is the low prevalence of chronic adverse symptoms associated with fundoplication. Although a small number in the REFLUX trial did have a postoperative dilatation procedure,1 2 later reports of difficulty swallowing, flatulence, and wanting to vomit but being unable to do so were similar in the two randomised groups (table 3). These differences between trials are important as they potentially alter the balance between benefits and risks of surgery. A possible explanation is the difference in fundoplication policies. In REFLUX, the choice of operation was left to the surgeon, and a high proportion of patients (53%) had a partial fundoplication. In the LOTUS trial, a standardised protocol specified total Nissen fundoplication.20 Partial fundoplication is associated with a lower rate of postoperative side effects but may have a higher rate of reoperation for recurrence of GORD.21

Meaning of the study

Five year follow-up has shown that laparoscopic fundoplication for patients for whom reasonable control of GORD symptoms requires long term medication, and for whom both surgery and medical management are suitable, continued to provide better relief of symptoms with associated improved quality of life. The more troublesome the symptoms at baseline, the greater the potential benefit from surgery. Decisions about surgery will be informed by the balance between benefits and risks. In this study, complications were rare and, unlike in other studies, there was no evidence that surgery caused long term unwanted symptoms such as difficulty swallowing.

Unanswered questions and future research

Patients and doctors making decisions about laparoscopic fundoplication would be aided by clearer evidence about the risks of long term morbidity and its associations with surgical technique. People with GORD are usually managed in primary care, and it is not clear currently how many such people might seek fundoplication in light of the findings of this and other trials.

What is already known on this topic

Laparoscopic fundoplication surgery provides better short term symptomatic relief than continued medical management for people with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD)

Uncertainty remains about whether benefits are sustained and possible long term side effects such as dysphagia and flatulence

What this study adds

Five year follow-up of trial participants confirmed sustained benefits of surgery as an alternative to drug treatment for GORD

Adverse effects of surgery were uncommon and generally observed soon after surgery

Unlike in some other studies, unwanted long-term symptoms were not associated with surgery in this trial

We thank Janice Cruden and Pauline Garden for their secretarial support and data management; Samantha Wileman and Julie Bruce for help with the overview of trials; Samantha Wileman, Maureen G C Gillan, Marie Cameron, Christiane Pflanz-Sinclair, and Lynne Swan for their assistance in nurse coordination and patient recruitment and follow-up; Sharon McCann for assistance in the piloting of the practical arrangements of this trial; and Allan Walker, Daniel Barnett, and Gladys McPherson for database and programming support.

Contributors: AMG was the principal grant holder, helped develop the trial protocol and prepare the paper, and was responsible for the overall conduct and reporting of the study. SCC was responsible for the day to day management of the trial, monitored data collection, and helped prepare the paper. CB conducted the statistical analysis. CRR helped with the grant application and trial design and conducted the statistical analysis. ZHK advised on clinical aspects of the trial and commented on the paper. RCH advised on clinical aspects of the trial design and the conduct of the trial and commented on the paper. MKC helped develop the trial design and contributed to all aspects of the conduct of the trial. AMG is the guarantor for this paper.

Members of the REFLUX Trial Group primarily responsible for the economic evaluation of the trial (reported separately) were Rita Faria, Laura Bojke, David Epstein, Belen Corbacho, and Mark Sculpher.

Members of the REFLUX Trial Group responsible for recruitment in the clinical centres were: A Mowat, Z Krukowski, E El-Omar, P Phull, T Sinclair, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary; B Clements, J Collins, A Kennedy, H Lawther, Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast; D Bennett, N Davies, S Toop, P Winwood, Royal Bournemouth Hospital; D Alderson, P Barham, K Green, R Mittal, Bristol Royal Infirmary; M Asante, S El Hasani, Princess Royal University Hospital, Bromley; A De Beaux, R Heading, L Meekison, S Paterson-Brown, H Barkell, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh; G Ferns, M Bailey, N Karanjia, TA Rockall, L Skelly, Royal Surrey County Hospital, Guildford; M Dakkak, J King, C Royston, P Sedman, Hull Royal Infirmary; K Gordon, LF Potts, C Smith, PL Zentler-Munro, A Munro, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness; S Dexter, P Maoyeddi, General Infirmary at Leeds; DM Lloyd, Leicester Royal Infirmary; V Loh, M Thursz, A Darzi, St Mary’s Hospital, London; A Ahmed, R Greaves, A Sawyerr, J Wellwood, T Taylor, Whipps Cross Hospital, London; S Hosking, S Lowrey, J Snook, Poole Hospital; P Goggin, T Johns, A Quine, S Somers, S Toh, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth; J Bancewicz, M Greenhalgh, W Rees, Hope Hospital, Salford; CVN Cheruvu, M Deakin, S Evans, J Green, F Leslie, North Staffordshire Hospital, Stoke-on-Trent; JN Baxter, P Duane, MM Rahman, M Thomas, J Williams, Morriston Hospital, Swansea; D Maxton, A Sigurdsson, MSH Smith, G Townson, Princess Royal Hospital, Telford; S Gore, RH Kennedy, ZH Khan, J Knight, Yeovil District Hospital; D Alexander, G Miller, D Parker, A Turnbull, J Turvill, York District Hospital.

Funding: This project was funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme (Project No 97/10/03) and will be published in full in Health Technology Assessment. See the HTA Programme website for further information. The Health Services Research Unit is funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorate.

This paper presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HTA Programme, or the Department of Health.

The sponsor had no direct role in the study design, analysis or reporting of the study. The researchers are independent of the funder.

All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support for the submitted work; RCH has received money from Reckitt Benckiser as chairman of its Medical Advisory Board and for consultancy and lectures, he has also received money for lectures from Nycomed (Takeda) and holds stock in Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser, and Novartis; AMG received partial salary support from the NIHR as director of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work have been declared.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Scotland A Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC/00/0/30).

Data sharing: An anonymised study dataset is available on request subject to resource implications and proposed use.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:f1908

References

- 1.Grant AM, Wileman SM, Ramsay CR, Mowat NA, Krukowski ZH, Heading RC, et al. Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: UK collaborative randomised trial. BMJ 2008;337:a2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant A, Wileman S, Ramsay C, Bojke L, Epstein D, Sculpher M, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of minimal access surgery amongst people with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease—a UK collaborative study. The REFLUX trial. Health Technol Assess 2008;12:1-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, Armstrong D, Goeree R, Ungar W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease: one-year follow-up. Surgical Innovation 2006;13:238-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, Armstrong D, Goeree R, Ungar W, et al. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): 3-year outcomes. Surg Endosc 2011;25:2547-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goeree R, Hopkins R, Marshall JK, Armstrong D, Ungar WJ, Goldsmith C, et al. Cost-utility of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for chronic and controlled gastroesophageal reflux disease: a 3-year prospective randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation. Value Health 2011;14:263-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundell L, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Galmiche J, Hatlebakk J, et al. Comparing laparoscopic antireflux surgery with esomeprazole in the management of patients with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a 3-year interim analysis of the LOTUS trial. Gut 2008;57:1207-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galmiche J, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, Ell C, Fiocca R, Eklund S, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD. The LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2011;305:1969-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahon D, Rhodes M, Decadt B, Hindmarsh A, Lowndes R, Beckingham I, et al. Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication compared with proton-pump inhibitors for treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg 2005;92:695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein D, Bojke L, Sculpher MJ, the REFLUX trial group. Laparoscopic fundoplication compared with medical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: cost effectiveness study. BMJ 2009;339:b2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant AM, Boachie C, Cotton SC, Faria R, Bojke L, Epstein DM, et al. Clinical and economic evaluation of laparoscopic surgery compared with medical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease—five-year follow-up of multicentre randomised trial (The REFLUX trial). Health Technol Assess (forthcoming). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Roland M, Torgerson DJ. What are pragmatic trials? BMJ 1998;316:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torgerson D, Sibbald B. Understanding controlled trials: What is a patient preference trial? BMJ 1998;316:360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dent J, Brun J, Fendrick AM, Fennerty MB, Janssens J, Kahrilas PJ, et al. An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management—the Genval Workshop Report. Gut 1999;44:S1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macran S, Wileman S, Barton G, Russell I. The development of a new measure of quality of life in the management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: the Reflux questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2007;16:331-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkinson C, Layte R, Wright L, Coulter A. The UK SF-36: an analysis and interpretation manual. 1996.

- 16.Brooks R, with the EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown H, Prescott R. Applied mixed models in medicine. Wiley, 1999.

- 18.Nagelkerke N, Fidler V, Bersen R, Borgdorff M. Estimating treatment effects in randomised clinical trials in the presence of non-compliance. Stat Med 2000;19:1849-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wileman SM, McCann S, Grant AM, Krukowski ZH, Bruce J. Medical versus surgical management for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;(3):CD003243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Attwood SEA, Lundell L, Ell C, Galmiche J, Hatlebakk J, Fiocca R, et al. Standardization of surgical technique in antireflux surgery: the LOTUS Trial experience. World J Surg 2008;32:995-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broeders JA, Roks DJ, Jamieson GG, Devitt PG, Baigrie RJ, Watson DI. Five year outcome after laparoscopic anterior partial versus Nissen fundoplication: four randomised trials. Ann Surg 2012;255:637-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]