Abstract

Adenylyl cyclase G (ACG) is activated by high osmolality and mediates inhibition of spore germination by this stress factor. The catalytic domains of all eukaryote cyclases are active as dimers and dimerization often mediates activation. To investigate the role of dimerization in ACG activation, we coexpressed ACG with an ACG construct that lacked the catalytic domain (ACGΔcat) and was driven by a UV-inducible promoter. After UV induction of ACGΔcat, cAMP production by ACG was strongly inhibited, but osmostimulation was not reduced. Size fractionation of native ACG showed that dimers were formed between ACG molecules and between ACG and ACGΔcat. However, high osmolality did not alter the dimer/monomer ratio. This indicates that ACG activity requires dimerization via a region outside the catalytic domain but that dimer formation does not mediate activation by high osmolality. To establish whether ACG required auxiliary sensors for osmostimulation, we expressed ACG cDNA in a yeast adenylyl cyclase null mutant. In yeast, cAMP production by ACG was similarly activated by high osmolality as in Dictyostelium. This strongly suggests that the ACG osmosensor is intramolecular, which would define ACG as the first characterized primary osmosensor in eukaryotes.

INTRODUCTION

Fluctuations in external osmolality are one of the most commonly encountered stress signals of living cells. In prokaryotes, osmotic up-shifts activate transporters, such as ProP, BetP, and OpuA, which increase cytosolic solute levels. In addition, dual-component histidine kinases, such as KdpK and EnvZ are activated, which trigger transcription of transporter genes. Osmotic down-shifts trigger opening of mechanosensitive channels, such as MscL, and release of solutes. All these proteins harbor intramolecular osmosensors that either detect changes in membrane tension or in cytosolic ion concentrations. Such changes are the consequences of the passive water fluxes that follow osmotic shifts (Blount et al., 1996; Jung et al., 2000, 2001; van der Heide and Poolman, 2000; Racher et al., 2001; Rubenhagen et al., 2001).

In eukaryotes, the yeast dual component histidine kinase SLN1 is the best characterized osmoregulated protein. Phosphorelay initiated by the SLN1 histidine kinase inhibits the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase HOG1, which triggers synthesis of the solute glycerol. Osmotic up-shift inhibits SLN1 kinase activity, which then allows HOG1 activation and glycerol synthesis to occur (Maeda et al., 1994). In Arabidopsis, the histidine kinase ATHK1 functions in a similar manner as SLN1 to activate a MAP kinase pathway after osmotic up-shift (Urao et al., 1999). MAP kinase pathways also mediate osmotic stress responses in animals, but no primary osmosensors have yet been identified (Kultz and Burg, 1998). It is also not clear whether SLN1 or ATHK1 harbor an intramolecular osmosensor.

In the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum, osmotic up-shift increases cAMP levels by two separate pathways. In the amoeba stage, osmotic up-shift reverts the histidine kinase DokA into a histidine phosphatase, which, similar to SLN1 and ATHK1, then acts as a phosphoryl group sink. This results in inactivation of the cAMP phosphodiesterase RegA and ultimately in fortification of the cell cortex (Schuster et al., 1996; Zischka et al., 1999; Ott et al., 2000). DokA is a soluble protein that is indirectly regulated by osmotic up-shift through phosphorylation of a serine in the histidine kinase domain (Oehme and Schuster, 2001). In the spore stage, osmotic up-shift activates adenylyl cyclase G (ACG), an enzyme that is structurally homologous to the Trypanosoma receptor adenylyl cyclases (Ross et al., 1991; Pitt et al., 1992; Van Es et al., 1996). High osmolality prevents premature germination of spores, while still in the fruiting body (Cotter and Raper, 1966; Virdy et al., 1999), and this process is mediated by ACG acting on cAMP-dependent protein kinase (Van Es et al., 1996).

The catalytic domains of eukaryote adenylyl- and guanylyl cyclases can only be active as dimers (Tesmer et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1997). Although the catalytic domains can sometimes dimerize in isolation (Zhang et al., 1997; Taylor et al., 1999), the signaling processes that activate these enzymes usually act on regions elsewhere in the protein to either induce dimerization or to correctly juxtapose or stabilize the monomer partners (Hurley, 1998; Yu et al., 1999).

We investigated the role of ACG dimerization in osmoregulation of enzyme activity, and we addressed the question whether the osmosensor is intrinsic to the ACG protein.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ACG Expression in Yeast

Preparation of ACG cDNA. An ACG cDNA was prepared from vector pBACG (gift from Peter N. Devreotes, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), which contains a 3.44-kb genomic fragment with the complete ACG coding sequence, 51 nucleotides (nt) 5′-untranslated region (UTR) and 616 nt 3′UTR, cloned into EcoRV-ClaI digested pBluescript SK. The XbaI site in the multiple cloning site of pBACG was eliminated by excision of the surrounding SacI/BamHI fragment, treatment with T4 DNA polymerase to blunt the 3′ and 5′ overhangs, and religation of the vector. The BglII/XbaI fragment from the ACG gDNA, which contains the two introns (Pitt et al., 1992), was then replaced by BglII/XbaI digested cDNA, which was generated by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction of D. discoideum spore RNA with primers cACG1 and cACG2 (Table 1). This yielded vector pBcACG.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| cACG1 | AGAGAGATCTTCAAAAC |

| cACG2 | GACTCCATTCTAGAGGC |

| HindIII-pBS5′ | CACAAGCTTCCCGGGCTGCAGGAATTCG |

| Sacl-ACGc3′ | GACGGAGCTCATCACTTGGAAATGGATCATCATGG |

| BamHI-PrA5′ | CAAGGATCCGGAGCAGGGGCGGGTGC |

| XhoI-PrA3′ | GAACTCGAGCGAATTCGCGTCTACTTTCGGCGC |

| BamHI-N-ACG | AAAGGATCCAAAACATTTGTAAAGATACTATC |

| XhoI-ACGΔCat | AACCTCGAGATCTAAAAAGAAGACACAAGC |

| XhoI-C-ACG | AACCTCGAGCTTTTTTTGATTCTACATTTTCGTC |

GAL1-ACG Construct and Yeast Transformation. An ACG cDNA fragment consisting of 51 nt of 5′UTR and 2049 base pairs of ACG open reading frame was amplified from pBcACG by using primers HindIII-pBS5′ and SacIACGc3′ (Table 1).

This amplified product lacks the last 528 base pairs of the C-terminal region, which contains highly AT-rich repetitive sequence and may be recombined or not properly translated in yeast. The HindIII-SacI digested product was fused to the yeast GAL1 promoter by subcloning into the HindIII-SacI digested yeast expression vector pYES2 (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA). The 430-base pair ZZ domain of protein A, obtained by amplification of vector pZZ-his5 (Rayner and Munro, 1998) with primers BamHI-PrA5′ and XhoIPrA3′, was fused to the C terminus of ACG by cloning into the BamHI-XhoI sites of the pYES2 multiple cloning site for future protein purification. Construct integrity was verified by DNA sequencing. The construct (GAL1-ACGZZ) was transformed by means of the lithium acetate method (Gietz et al., 1992) into the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cyr1 null mutant TC41F2-1 (MATa cyr1::ura3 cam1 cam2 cam3 leu2-3,112 his3-532 his4 ura3) (Heideman et al., 1990). Transformants were selected for growth in the absence of 1 mM cAMP. Standard methods and media for yeast culture were used (Burke et al., 2000).

ACG Constructs and Transformation of Dictyostelium Cells

To generate a construct for spore-specific expression of truncated ACG (ACGΔcat), we amplified 1487 base pairs of genomic ACG DNA from vector pBACG with primers BamHI-N-ACG and XhoI-ACGΔCat (Table 1). When translated, this DNA fragment (which contains the two introns) will yield the first 401 amino acids of the ACG gene but will lack almost the entire catalytic domain and the low-complexity C terminus. The BamHI-XhoI digested fragment was used to replace the BglII-XhoI LacZ insert from psA-Neo-Gal (gift from Jeff Williams, University of Dundee, Dundee, United Kingdom). This placed ACGΔcat downstream of the psA prespore promoter and start codon and yielded plasmid psA-ACGΔcat. AX2 cells were transformed with the plasmid by electroporation, and transformed clones were selected for growth in the presence of 100 μg/ml G418.

To generate a construct for inducible expression of ACGΔcat, we first exchanged a BamHI-HindIII fragment from plasmid RNR-P that contained the neomycin selection cassette (Gaudet et al., 2001) with a BamHI-HindIII fragment from PucBsr that carried the blasticidin selection cassette (Sutoh, 1993) to generate pBsr-RNR. The BamHI-XhoI digested ACGΔcat fragment was then fused to the RNR promoter by ligation into BglII-XhoI digested pBsr-RNR to create vector RNR-ACGΔcat. aca cells (Pitt et al., 1992) were cotransformed with RNR-ACGΔcat and vector pGSP1, which harbors the neomycin selection cassette and a gene fusion of the constitutive actin15 promoter and full-length ACG (Pitt et al., 1992). Cells were selected for growth in the presence of 20 μg/ml G418 and 5 μg/ml blasticidin. pGSP1 was also singly transformed into aca cells and selected for growth with 20 μg/ml G418.

Spore Germination Assay

Cells were grown in axenic medium, harvested, and plated at 106 cells/cm2 on KK2 agar (1.5% agar in 10 mM K-phosphate, pH 6.2) until fruiting bodies had formed. Spores were harvested from 2-d-old fruiting bodies by shaving their spore heads with the edge of a glass slide. Spores were washed three times with KK2, resuspended to 107 spores/ml, and either heat shocked for 30 min at 45°C or left at 22°C. Spore suspensions were then diluted 1:1 with either KK2 or 0.5 M sucrose in KK2 and shaken for 12 h at 165 rpm and 23°C. The number of spores and germinated amoebae was counted every 2 h in a hemocytometer under a phase-contrast microscope (Cotter, 1981).

Assay for cAMP Accumulation in Yeast

Exponentially growing yeast cells were harvested from YPD medium (Burke et al., 2000), washed, and resuspended in 5 mM MES buffer, pH 6.0, at 30 mg of wet weight per milliliter. Cells were preincubated for 10 min at 30°C and subsequently stimulated with NaCl or sorbitol at 30°C as indicated in the figure legends. At different time intervals, 2.5-ml aliquots of cell suspension were quenched by rapid submersion in 10 ml of 60% methanol, precooled to -40°C. Cells were pelleted by centrifuging for 5 min at 1560 × g and 1°C and resuspended in 0.5 ml of 1 M perchloric acid. The suspension was transferred to a Microfuge tube containing 0.5 ml of glass beads (size 425-600 μm), vortexed for 10 cycles of 30 s at 4°C, and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g. Then 20-μl aliquots of supernatant were neutralized with 8 μl of 100% saturated KHCO3, and cAMP levels were measured by isotope dilution assay (Gilman, 1972; Thevelein et al., 1987a).

Activation of the RNR Promoter and Assay for ACG Activity in Dictyostelium Cells

Cells grown to 5 × 106 cells/ml in HL5 were irradiated with UV at 30 J/m2 by using a Bio-Link UV cross linker (VWR, Poole, United Kingdom). Cells were then diluted 10-fold in HL5 and left for 1 h at 22°C to allow transcription from the RNR promoter (Gaudet et al., 2001). The uninduced controls were treated in the same manner, except that UV irradiation was omitted. For assay of ACG activity, cells were washed free from HL5, resuspended to 5 × 107 cells/ml in KK2, and shaken for 10 min at 165 rpm. Aliquots of 25 μl of cell suspension were incubated with different variables in a total volume of 30 μl. Reactions were started by addition of the phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitor dithiothreitol to a final concentration of 5 mM and terminated by the addition of 30 μl of 3.5% perchloric acid (vol/vol). Lysates were neutralized with 50% saturated KHCO3 and cAMP levels were measured by isotope dilution assay.

Protein Fractionation

To extract total Dictyostelium proteins under denaturing conditions, cells were resuspended to 2 × 107 cells/ml in KK2, mixed with an equal volume of 2× SDS-PAGE sample buffer, boiled for 5 min, and size fractionated on 10% SDS-PAA gels. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and Western blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with a 1:2000 diluted αACG antibody. This antibody was raised in rabbit by Sigma Genosys (Pampisford, United Kingdom) against a cysteine-linked peptide SLNSNDLIDGSEYHDDPFP in the C-terminal of ACG (aa 663-681). Detection was performed with the Supersignal chemoluminescence kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL) according to the manufacturer's instructions, by using 1:2000 diluted horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Promega, Madison, WI) as secondary antibody.

To extract yeast proteins, 5 × 108 cells were resuspended in 1.2 ml of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.3 M sorbitol, 0.1 M NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 1× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, United Kingdom) and vortexed at 4°C for 15 cycles of 30 s with 0.7 g of glass beads. Lysates were centrifuged at 800 × g and 4°C for 10 min. Supernatants were mixed with an equal volume of 2× sample buffer and further treated as Dictyostelium total protein extracts.

Assay for Dimer Formation

To test for effects of osmotic up-shift on ACG dimer formation, cells were resuspended in KK2 and incubated for 5 min with or without 100 mM NaCl before being lysed by passage through nuclepore filters (pore size 3 μm). Lysates were prepared in the presence of 1× Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics) and centrifuged for 30 min at 20,000 × g and 4°C. Pellets were washed in 5 mM glycine, pH 7.4, and centrifuged once more at 20,000 × g. The membranes were resuspended in 0.5% Triton in 5 mM glycine, pH 7.4, and incubated for 1 h on ice to solubilize the membrane proteins. The suspension was cleared by centrifuging for 15 min at 16,000 × g, and the protein concentration of the supernatant fraction was measured using Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom). Equal amounts of protein were directly loaded on nonreducing 8% SDS-PAA gels, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes after electrophoresis, and incubated with ACG antibody as described above.

RESULTS

Heterologous Expression of ACG

To investigate whether high osmolality acts directly on ACG or requires a separate sensor protein, we expressed ACG in the fungus S. cerevisiae, which is only distantly related to the mycetozoan Dictyostelium (Baldauf et al., 2000). To avoid interference from the yeast adenylyl cyclase, we used strain TC41F2-1, which carries a null mutation in the CYR1 gene, that encodes the single yeast adenylyl cyclase (Heideman et al., 1990). CYR1 is essential for growth and the cyr1 null mutant can only grow in the presence of 1 mM cAMP. An ACG cDNA was prepared in which 175 aa of C-terminal low-complexity sequence was replaced by a 140-aa protein A ZZ tag. The construct was expressed in cyr1 under control of the yeast GAL1 promoter (GAL1-ACG-ZZ; Figure 1). Figure 2A shows rescue of the growth-deficient phenotype of cyr1 in four independent transformed clones. This indicates that ACG is active in the cyr1 mutant.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the ACG expression constructs. The constructs and protein structural domains are drawn according to scale except for the promoters (block arrows). The position and sequence of the peptide used to generate the αACG antibody is marked on the A15-ACG construct. The size of the proteins in amino acid residues is indicated.

Figure 2.

Expression of ACG in S. cerevisiae. (A) Growth of the yeast cyr1 mutant TC41F2-1 (parent) and four clones (A1, A5, B1, and B5) transformed with the GAL1-ACG-ZZ fusion construct (cyr1/ACG) on standard yeast culture medium without cAMP. (B) Western blots of expressed ACG proteins. Lysates of Dictyostelium acg and aca/ACG cells, and of yeast cyr1 and cyr1/ACG cells were size fractionated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with αACG antibodies. The size (in kilodaltons) of protein markers is indicated.

Expression of the ACG fusion construct was confirmed by immunoblotting of size-fractionated cell lysates with an αACG antibody. The antibody was raised in rabbit against a 19-aa peptide in the C-terminal region of ACG (Figure 1) and was tested for specificity on acg null cells and aca null cells that constitutively express ACG (aca/ACG) (Pitt et al., 1992). The antibody identified a single band of ∼100 kDa on Western blots of aca/ACG cells, which agrees with the predicted size of 98 kDa for full-length ACG. The band was absent from acg null mutants, which indicates that the antibody is specific for ACG (Figure 2B). The yeast cyr1 cells transformed with the GAL1-ACG-ZZ construct (cyr1/ACG) showed a somewhat smaller band, which was absent from the untransformed cyr1 cells (Figure 2B). The difference in size is due to replacement of the C-terminal low-complexity region with the ZZ tag.

We measured whether cAMP production by ACG in the cyr1/ACG cells was stimulated by high osmolality. Dictyostelium cells secrete most of the cAMP that they produce and cAMP production by ACG can be readily detected in the extracellular medium. Under those conditions solute concentrations of 200 milliosmolar induce a further two- to fourfold stimulation of cAMP accumulation (Van Es et al., 1996). In contrast, yeast cells secrete very little cAMP and require rigorous procedures to break the cell wall before cAMP can be measured (Thevelein et al., 1987a). cyr1/ACG cells and the yeast wild-type strain AY297 were stimulated with either 0.5 M NaCl or 1 M sorbitol or with low-osmolality buffer, and cAMP levels were measured at the indicated time intervals. Figure 3A shows that both 0.5 M NaCl and 1 M sorbitol induced a rapid increase of cAMP levels, which peaked at 45 s after stimulation. The osmolarity required for maximal ACG stimulation in yeast was at 1 M rather higher than in Dictyostelium (Figure 3B). This could be due to dissimilarities in the phospholipid composition of Dictyostelium and yeast membranes, as was demonstrated for the bacterial osmosensor BetP (Rubenhagen et al., 2000). In wild-type yeast, both NaCl and sorbitol induced a decrease in cAMP levels (Figure 3A). This demonstrates that the osmostimulation of cAMP production in cyr1/ACG cells must result from activation of ACG and not from, e.g., inactivation of a yeast phosphodiesterase.

Figure 3.

Osmoregulation of ACG in S. cerevisiae. (A) Time course of cAMP accumulation. cyr1/ACG cells were harvested from growth medium and resuspended in 5 mM MES, pH 6.0. Cells were stimulated with 1/10 volume of either 5 M NaCl or 1/5 volume of 5 M sorbitol. Reactions were quenched at the indicated time intervals by sixfold dilution in 60% methanol at -40°C. After cell rupture, cAMP levels were measured by isotope dilution assay. Means and SE of three experiments performed in triplicate are presented. (B) Dose-response curve. cyr1/ACG cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of NaCl. Reactions were quenched at 45 s after stimulation and assayed for cAMP. Means and SE of four experiments performed in triplicate are presented.

The Role of Dimerization in Osmoregulation of Spore Dormancy

Truncated forms of the receptor guanylyl cyclases that lack the catalytic domain act as dominant-negative inhibitors because they sequester the native proteins by dimerization (Chinkers and Wilson, 1992). We used the same strategy to establish whether dimerization outside the catalytic domain is essential for ACG function during spore germination. Wild-type cells were transformed with a fusion construct of the psA prespore promoter and sequence encoding the N-terminal 401 amino acids of ACG. This construct (psAACGΔcat) lacks the cyclase domain and the low-complexity C-terminal region (Figure 1). The psA promoter directs expression of the construct in prespore and spore cells during normal development (Hopper et al., 1993).

Dictyostelium spores are normally activated to germinate by exposure to food, but rapid synchronous activation can be achieved by a heat shock. After activation spores enter a lag phase of 1-2 h before swelling and emergence occur. Exposure to high osmolality during the lag phase will induce the spores to return to dormancy (Cotter and Raper, 1967; Virdy et al., 1999). Figure 4A shows that after heat shock, wild-type spores germinated within 10 h at low osmolality, but not at all at high osmolality or in the absence of heat shock. In contrast to wild-type spores, the psAACGΔcat spores did not require a heat shock to germinate and germination was not inhibited by high osmolality (Figure 4B). These data suggest that ACGΔcat inhibits ACG function during spore germination.

Figure 4.

Effects of a truncated ACG protein on spore germination. Wild-type cells were transformed with a fusion construct of the psA prespore promoter and an ACG truncation that lacks the catalytic domain (psA-ACGΔcat). Wild-type and transformed spores either received a 45°C heat shock for 30 min or were left at 22°C before being incubated for 11 h in the presence and absence of 250 mM sucrose. Every 2 h, the ratio of spores to emerged amoebae was counted in a sample size of 100 cells. Means and SD of four experiments are presented.

The Role of Dimerization in Osmoregulation of ACG Activity

Spores are inaccessible for direct measurement of ACG inhibition by ACGΔcat. We therefore coexpressed ACG and ACGΔcat in growing cells. Heterologous protein expression presents the problem that the absolute amount of expressed protein is determined by the copy number of the transformation vector. Results that depend on stochiometric interaction between two heterologously expressed proteins will for this reason suffer from unpredictable clone-to-clone variability. To circumvent this problem, we coexpressed ACG under control of the constitutive actin15 promoter (A15-ACG) (Pitt et al., 1992) with ACGΔcat under control of the UV-inducible ribonucleotide reductase promoter (RNRACGΔcat). The UV-inducible promoter allows modulation of the level of ACGΔcat in the same transformed cell line (Gaudet and Tsang, 1999; Gaudet et al., 2001). The vectors that harbor the A15-ACG and RNR-ACGΔcat gene fusions carried cassettes for neomycin and blasticidin selection, respectively, to allow for simultaneous selection and were transformed into aca cells to prevent interference with cAMP production by ACA, which is expressed during early development (Pitt et al., 1992). The RNR promoter was activated by exposure of growing cells to UV light, followed by further incubation for 1 h in growth medium to allow for optimal induction of RNR-ACGΔcat gene expression. Pilot experiments showed that in the absence of RNR-ACGΔcat, UV irradiation had no effect on ACG activity.

Figure 5A shows that cAMP accumulation in the parent aca strain is very low. Cells cotransformed with A15-ACG and RNR-ACGΔcat accumulate ∼40 pmol of cAMP/107 cells over a 10-min period in the absence of UV induction of ACGΔcat expression. Hyperosmotic conditions, created by 100 mM NaCl induced a twofold stimulation of cAMP accumulation (Figure 5B). After induction of RNR-ACGΔcat expression by UV, cAMP production by A15ACG was ∼50% inhibited, but 100 mM NaCl still induced a twofold stimulation (Figure 5C). These data show that expression of ACGΔcat reduces the absolute level of ACG activity but does not prevent stimulation of the enzyme by high osmolality. The inhibitory effect of ACGΔcat seems rather moderate in comparison with its complete block of osmoregulation of spore germination as shown in Figure 4. However, it should be realized that in the spore germination experiment only the endogenous ACG, with low expression levels (Pitt et al., 1992) needs to be inactivated, whereas in the double-transformed cells ACGΔcat competes with ACG expressed from the strong actin15 promoter.

Figure 5.

Effect of conditional ACGΔcat expression on osmoregulation of ACG. aca cells were double transformed with constructs A15-ACG and RNR-ACGΔcat. The A15 and RNR promoters in these constructs direct constitutive and UV-inducible transcription, respectively. Effects of 100 mM NaCl on cAMP accumulation were measured in untransformed aca cells (A), uninduced transformants (B), and UV-induced transformants (C). Means and SE of three experiments performed in triplicate are presented.

Immunological Detection of ACG Dimerization

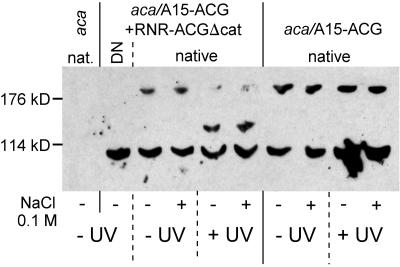

To demonstrate that ACG and ACGΔcat form homo- and heterodimers, we isolated the native protein complexes. Cells transformed with both the A15-ACG and RNRACGΔcat constructs were exposed to UV to induce ACGΔcat expression and both UV-treated and untreated cells were stimulated for 5 min with 100 mM NaCl and lysed. As controls, we also included the aca parent strain and aca cells that were transformed with A15-ACG alone. Membrane proteins were solubilized, and native proteins were size fractionated by gel electrophoresis and immunoblotted with αACG antibody. The antibody can detect full-length ACG but not ACGΔcat because the epitope is in the truncated region (Figure 1).

Figure 6 shows that in aca cells transformed with A15-ACG and RNR-ACGΔcat, that were not exposed to UV, the ACG antibody detected bands around 100 and 200 kDa in a roughly 70:30% ratio. These bands most likely represent monomers and dimers of full-length ACG, which are 98 and 196 kDa, respectively. Membrane proteins that were denatured and therefore monomerized by boiling in SDS sample buffer (DN) did not show the dimer band at 200 kDa, which indicates that this band does not represent nonspecific reactivity of the ACG antibody with a 200-kDa protein. This is further confirmed by the absence of any bands in native preparations from untransformed aca cells. After UV-induction of RNR-ACGΔcat expression, the 200-kDa bands largely disappeared and a novel band of ∼140 kDa occurred. This band most likely represents the heterodimer of full-length ACG (98 kDa) and ACGΔcat (46 kDa). The appearance of the 140-kDa band is not an artifact of the UV exposure, because cells that only contained the A15-ACG construct showed the 100- and 200-kDa bands in the presence and absence of UV exposure. In both UV-induced and uninduced cells the monomer/dimer ratio was not altered by stimulation with 100 mM NaCl, which suggests that high osmolality does not promote dimer formation.

Figure 6.

Effects of high osmolality on ACG and ACGΔcat homo- and heterodimerization. aca cells, either single transformed with A15-ACG or double transformed with A15-ACG and RNRACGΔcat, were UV induced as indicated and subsequently treated with and without 100 mM NaCl for 5 min and lysed. The untransformed aca parent was lysed without pretreatment. Membranes were purified and membrane proteins were solubilized in 0.5% Triton X-100. For one sample of double-transformed cells, the membrane proteins were denatured (DN) by boiling in sample buffer containing 2% SDS. Equal amounts of native protein and denatured protein were loaded on nonreducing SDS-PAA gels and immunoblotted with αACG antibodies. The position of protein size markers is indicated.

DISCUSSION

ACG Harbors an Intramolecular Osmosensor

ACG is predominantly expressed in the spore stage (Pitt et al., 1992), where it mediates inhibition of spore germination by high osmolality (Van Es et al., 1996). However, when expressed from a constitutive promoter in the amoeba stage, the enzyme was also activated by high osmolality, which suggested that the osmosensor could be intramolecular (Van Es et al., 1996). Because we could not rule out that an accessory sensor protein was expressed throughout development, it was essential to measure ACG activity in a system that was unlikely to express such a sensor. The choice of organism was limited to protists, because metazoan cells require culture at high osmolality. Preferably, the organism of choice should not display any adenylyl cyclase activity, which could interfere with the assay. We chose a mutant strain of the fungus S. cerevisiae that lacks the single adenylyl cyclase gene CYR1. In contrast to ACG, yeast CYR1 is not a transmembrane protein (Mitts et al., 1990); it is stimulated by glucose and requires both the heterotrimeric G protein Gpa2 and the small G protein Ras2 for activity (Thevelein et al., 1987b; Colombo et al., 1998). Because ACG is not regulated by G proteins (Pitt et al., 1992), it is unlikely that the mechanisms that activate CYR1 would act on ACG. In both yeast and Dictyostelium, high osmolality modulates histidine kinase activity (Maeda et al., 1994; Schuster et al., 1996), but the Dictyostelium histidine kinase DokA plays no role in regulating ACG (Ott et al., 2000) and the yeast enzyme SLN1, which targets the HOG1 MAP kinase pathway, is therefore also unlikely to do so. In fact, responses to osmotic stress are very different in the two organisms. Yeast cells respond to high osmolality with synthesis of the compatible osmolyte glycerol, a process that is mediated by the HOG1 pathway (Maeda et al., 1994). Dictyostelium cells do not accumulate compatible osmolytes and respond instead by remodeling of the cell cortex, a process that involves phosphorylation of actin and myosin (Zischka et al., 1999). It is therefore unlikely that any component of the osmostimulated HOG1 pathway, including glycerol, would activate ACG.

Dictyostelium ACG complemented the growth defect of the yeast cyr1 null mutant (Figure 2) and similar to Dictyostelium cells, cAMP production in the cyr1/ACG cells was stimulated by high osmolality. However, higher solute concentrations were required and the stimulated cAMP accumulation in yeast was more transient than in Dictyostelium.

The transient kinetics of cAMP accumulation in yeast is probably due to the fact that the yeast cAMP phosphodiesterase PDE1 is strongly stimulated by cAMP through activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. This rapidly neutralizes glucose-induced cAMP accumulation in wild-type yeast after 45 s of stimulation (Ma et al., 1999), which agrees exactly with the kinetics of high osmolality-induced cAMP accumulation in cyr1/ACG cells (Figure 3A). This suggests that the transient kinetics of cAMP accumulation in yeast is a function of PDE1, rather than of either CYR1 or ACG. The pronounced effect of PDE1 on cAMP levels in yeast raises the possibility that high osmolality could have increased cAMP by inhibiting PDE1 (or PDE2), instead of by activating ACG. However, this cannot be the case because in wild-type yeast both NaCl and sorbitol decreased cAMP levels (Figure 3A). We cannot completely exclude that a currently unknown response to osmotic up-shift in yeast has led to activation of ACG, but direct stimulation of ACG by high osmolality is by far the most likely explanation. This implies that the osmosensor is intrinsic to the ACG protein.

The difference in concentration dependence between ACG expressed in Dictyostelium or in yeast may relate to the question of what is actually being detected by ACG. Apart from the increase in extracellular solute concentration, osmotic up-shift causes passive water efflux from cells, which in turn induces many physicochemical changes, such as cell shrinkage, increased intracellular solute and ion concentration, macromolecular crowding, and increased membrane curvature (Wood, 1999). Many of these parameters can potentially affect protein function. Elegant studies of reconstituted purified bacterial osmosensors in liposomes have shown that the ABC transporter OpuA and the channel protein Mscl respond to alterations in membrane tension (Blount et al., 1996; van der Heide and Poolman, 2000). The dual component histidine kinases KdpK and EnvZ sense the cytosolic increases of respectively ionic strength and K+-ions that result from water efflux (Jung et al., 2000, 2001). The Na+/betaine symport transporter BetP is also activated by K+ ions (Rubenhagen et al., 2001). If ACG activation is similarly dependent on the secondary effects of passive water efflux, the higher solute concentration dependence of ACG expressed in yeast may simply reflect higher resistance of yeast cells to those effects. The different membrane composition of yeast cells may also play a role, because it was demonstrated that the dose dependence for osmostimulation of the bacterial osmosensor BetP was strongly influenced by the phospholipid composition of the membrane (Rubenhagen et al., 2000). Our next challenge will be to purify and reconstitute ACG in liposomes that mimic the Dictyostelium membrane lipid composition (Weeks and Herring, 1980), to identify the actual parameter for activation of ACG.

Role of Dimerization

A wide range of signal transduction proteins ranging from growth factor receptors (Schlessinger, 2002), dual component histidine kinases (Bilwes et al., 1999), and STAT transcription factors (Imada and Leonard, 2000) to adenylyl cyclases (Tesmer et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 1997) requires dimerization for activity, and in many cases, dimer formation mediates activation of these proteins. Eukaryote adenylyl- and guanylyl cyclases can only bind substrate when two catalytic domains are combined in an antiparallel wreath-like structure (Liu et al., 1997). In the case of the G protein-regulated adenylyl cyclases, which harbor two intramolecular catalytic domains, the monomers are already joined and activating factors such as Gsα or forskolin promote the catalytically optimal juxtaposition of the two monomers (Hurley, 1998). However, for the single transmembrane cyclases, which like ACG harbor a single catalytic domain, dimerization can mediate activation. This is the case for the retinal guanylyl cyclase RetGC, which is dependent on guanylyl cyclase activator proteins (GCAPs) for dimer formation. Each RetGC momomer binds to a GCAP monomer. The GCAP monomers dimerize in the absence of cytosolic Ca2+, and this also brings the RetGC monomers together (Olshevskaya et al., 1999; Yu et al., 1999). In the receptor guanylyl cyclases, such as the atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) receptor, activation is due to a change in relative orientation of the dimers, rather than in dimer formation itself. In the basal state the ANP receptor forms an inactive dimer by interactions between the intracellular coiled-coil and kinase homology domains. The ligand ANP binds simultaneously to the extracellular regions of the two monomers, which triggers closure of their membrane proximal domains. This causes a change in alignment of the intracellular domains, which ultimately results in activation of guanylyl cyclase (Wilson and Chinkers, 1995; He et al., 2001; Labrecque et al., 2001).

ACG and the Leishmania and Trypanosoma adenylyl cyclases show a superficial structural similarity to the ANP receptor, but no kinase homology domain or coiled-coil domains are present (Figure 7). There is no significant sequence similarity between the extracellular domains of ANP-R, ACG, and the parasite cyclases. The isolated catalytic domains of the T. brucei enzymes ESAG4, GRESAG4.1, and GRESAG4.3 show a weak tendency to form catalytically competent dimers (Bieger and Essen, 2001). The catalytic domains of both GRESAG4.4B and TczAC can form stable dimers, although the full-length TczAC protein shows much higher catalytic activity (D'Angelo et al., 2002). Enforced dimer formation by fusion of a leucine zipper to the GRESAG4.4B catalytic domains also greatly enhanced activity (Naula et al., 2001). In the case of ACG, the isolated catalytic domains showed no catalytic activity and did not dimerize (our unpublished data). This group of enzymes is therefore likely to either require additional proteins or additional regions within the protein to enforce the dimerized state.

Figure 7.

Domain architecture of receptor adenylyl- and guanylyl cyclases. All sequences were retrieved from GenBank and the domain architecture was determined with the SMART program (Schultz et al., 1998). The size of the proteins in aa residues is indicated. The cyclase catalytic domains (AC or GC), kinase homology domain (KHD), ANP binding domain (ANP-R), coiled-coil, and transmembrane domains are drawn according to scale. Accession numbers are Homo sapiens ANPR: XM_113360; D. discoideum ACG: M87278; Trypanosoma brucei ESAG4: Q26721; T. brucei GRESAG4.3: X52121; T. brucei GRESAG4.4B: AF228602; Trypanosoma cruzi ADC1: AJ012096; T. cruzi zAC: AF040382; and Leishmania donovani RAC-A: U17042.

We show here that the ACGΔcat construct without the catalytic domain can dimerize with the full-length protein (Figure 6) and acts as a dominant-negative inhibitor of enzyme activity (Figures 4 and 5). This indicates that in addition to the catalytic domain, ACG has a separate dimerizing region. Unlike ANP-R, neither ACG nor the parasite adenylyl cyclases have a significant juxtamembrane intracellular region that could mediate dimer formation (Figure 7), and dimerization therefore most likely requires the extracellular domain of the protein.

Our data do not support a role for osmotic up-shift as direct trigger for dimerization. Overexpression of ACGΔcat in spores blocked the inhibition of spore dormancy by high osmolality, but the spores also no longer required a heat shock to activate the germination process (Figure 4). Spores contain 10 times higher cAMP concentrations than amebae, most of which is produced by ACG (Virdy et al., 1999). Shortly after heat shock cAMP levels decrease dramatically, but they transiently increase again during the postactivation lag phase. This increase is more pronounced when heat-activated spores are exposed to high osmolality. Heat shock induces a transient loss of ACG mRNA, which may cause the decrease of cAMP levels and activation of the germination process (Virdy et al., 1999). The fact that ACGΔcat both obviated the requirement for heat shock and prevented osmoregulation of germination suggests that it inhibits both basal and osmostimulated ACG activity. This was confirmed by measurement of ACG activity in the presence and absence of the ACGΔcat. Even though ACGΔcat strongly reduced ACG activity, it did not prevent activation of the residual activity by high osmolality (Figure 5). Most importantly, high osmolality did not increase the ACG dimer to monomer ratio (Figure 6). We therefore conclude that high osmolality does not activate ACG by causing it to dimerize and that osmoregulation of ACG involves a novel mode of regulation of this important class of enzymes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Pascal Gaudet for the kind gift of the RNR-P plasmid, Professor Peter N. Devreotes for the vectors pGSP1 and pBACG, and professor Jeff Williams for psA-neo-gal. We are grateful to Professor Warren Heideman for the kind gift of the yeast cyr1 mutant TC41F2-1, and we thank professor Johan M. Thevelein for protocols and valuable advice on cAMP assays in yeast. We thank Professor Michael J. Stark and Dr. Najma Richidi for assistance with yeast culture and transformation and Dr. Marcel Meima for preparation of the ACG cDNA. This research was funded by Wellcome Trust University Award grant 057137.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0622. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0622.

References

- Baldauf, S.L., Roger, A.J., Wenk-Siefert, I., and Doolittle, W.F. (2000). A kingdom-level phylogeny of eukaryotes based on combined protein data. Science 290, 972-977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieger, B., and Essen, L.O. (2001). Structural analysis of adenylate cyclases from Trypanosoma brucei in their monomeric state. EMBO J. 20, 433-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilwes, A.M., Alex, L.A., Crane, B.R., and Simon, M.I. (1999). Structure of CheA, a signal-transducing histidine kinase. Cell 96, 131-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blount, P., Sukharev, S.I., Moe, P.C., Schroeder, M.J., Guy, H.R., and Kung, C. (1996). Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel protein of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 15, 4798-4805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, D., Dawson, D., and Stearn, T. (2000). Methods in Yeast Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Chinkers, M., and Wilson, E.M. (1992). Ligand-independent oligomerization of natriuretic peptide receptors. Identification of heteromeric receptors and a dominant negative mutant. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 18589-18597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, S., et al. (1998). Involvement of distinct G-proteins, Gpa2 and Ras, in glucose- and intracellular acidification-induced cAMP signalling in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 17, 3326-3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter, D.A. (1981). Spore activation. In: The Fungal Spore, ed. A. Turian and H. R. Hohl, New York: Academic Press, 385-411.

- Cotter, D.A., and Raper, K.B. (1966). Spore germination in Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 56, 880-887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotter, D. A. and Raper, K. B. (1967). Analysis of heat shock-induced germination in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Cell Biol. 35, 28A. [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo, M.A., Montagna, A.E., Sanguineti, S., Torres, H.N., and Flawia, M.M. (2002). A novel calcium-stimulated adenylyl cyclase from Trypanosoma cruzi, which interacts with the structural flagellar protein paraflagellar rod. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35025-35034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet, P., MacWilliams, H., and Tsang, A. (2001). Inducible expression of exogenous genes in Dictyostelium discoideum using the ribonucleotide reductase promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, E5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet, P., and Tsang, A. (1999). Regulation of the ribonucleotide reductase small subunit gene by DNA-damaging agents in Dictyostelium discoideum. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 3042-3048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz, D., St Jean, A., Woods, R.A., and Schiestl, R.H. (1992). Improved method for high efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman, A.G. (1972). Protein binding assays for cyclic nucleotides. Adv. Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 2, 9-24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, X., Chow, D., Martick, M.M., and Garcia, K.C. (2001). Allosteric activation of a spring-loaded natriuretic peptide receptor dimer by hormone. Science 293, 1657-1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heideman, W., Casperson, G.F., and Bourne, H.R. (1990). Adenylyl cyclase in yeast: antibodies and mutations identify a regulatory domain. J. Cell. Biochem. 42, 229-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, N.A., Harwood, A.J., Bouzid, S., Véron, M., and Williams, J.G. (1993). Activation of the prespore and spore cell pathway of Dictyostelium differentiation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and evidence for its upstream regulation by ammonia. EMBO J. 12, 2459-2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley, J.H. (1998). The adenylyl and guanylyl cyclase superfamily. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 8, 770-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imada, K., and Leonard, W.J. (2000). The Jak-STAT pathway. Mol. Immunol. 37, 1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K., Hamann, K., and Revermann, A. (2001). K+ stimulates specifically the autokinase activity of purified and reconstituted EnvZ of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 40896-40902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, K., Veen, M., and Altendorf, K. (2000). K+ and ionic strength directly influence the autophosphorylation activity of the putative turgor sensor KdpD of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 40142-40147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kultz, D., and Burg, M. (1998). Evolution of osmotic stress signaling via MAP kinase cascades. J. Exp. Biol. 201, 3015-3021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrecque, J., Deschenes, J., McNicoll, N., and De Lean, A. (2001). Agonistic induction of a covalent dimer in a mutant of natriuretic peptide receptor-A documents a juxtamembrane interaction that accompanies receptor activation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 8064-8072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y., Ruoho, A.E., Rao, V.D., and Hurley, J.H. (1997). Catalytic mechanism of the adenylyl and guanylyl cyclases: modeling and mutational analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13414-13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, P.S., Wera, S., Van Dijck, P., and Thevelein, J.M. (1999). The PDE1-encoded low-affinity phosphodiesterase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has a specific function in controlling agonist-induced cAMP signaling. Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 91-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda, T., Wurgler-Murphy, S.M., and Saito, H. (1994). A two-component system that regulates an osmosensing MAP kinase cascade in yeast. Nature 369, 242-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitts, M.R., Grant, D.B., and Heideman, W. (1990). Adenylate cyclase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a peripheral membrane protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 3873-3883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naula, C., Schaub, R., Leech, V., Melville, S., and Seebeck, T. (2001). Spontaneous dimerization and leucine-zipper induced activation of the recombinant catalytic domain of a new adenylyl cyclase of Trypanosoma brucei, GRESAG4.4B. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 112, 19-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehme, F., and Schuster, S.C. (2001). Osmotic stress-dependent serine phosphorylation of the histidine kinase homologue DokA. BMC Biochem. 2, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshevskaya, E.V., Ermilov, A.N., and Dizhoor, A.M. (1999). Dimerization of guanylyl cyclase-activating protein and a mechanism of photoreceptor guanylyl cyclase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25583-25587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott, A., Oehme, F., Keller, H., and Schuster, S.C. (2000). Osmotic stress response in Dictyostelium is mediated by cAMP. EMBO J. 19, 5782-5792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, G.S., Milona, N., Borleis, J., Lin, K.C., Reed, R.R., and Devreotes, P.N. (1992). Structurally distinct and stage-specific adenylyl cyclase genes play different roles in Dictyostelium development. Cell 69, 305-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racher, K.I., Culham, D.E., and Wood, J.M. (2001). Requirements for osmosensing and osmotic activation of transporter ProP from Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 40, 7324-7333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner, J.C., and Munro, S. (1998). Identification of the MNN2 and MNN5 mannosyltransferases required for forming and extending the mannose branches of the outer chain mannans of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 26836-26843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross, D.T., Raibaud, A., Florent, I.C., Sather, S., Gross, M.K., Storm, D.R., and Eisen, H. (1991). The trypanosome VSG expression site encodes adenylate cyclase and a leucine-rich putative regulatory gene. EMBO J. 10, 2047-2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenhagen, R., Morbach, S., and Kramer, R. (2001). The osmoreactive betaine carrier BetP from Corynebacterium glutamicum is a sensor for cytoplasmic K+. EMBO J. 20, 5412-5420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenhagen, R., Ronsch, H., Jung, H., Kramer, R., and Morbach, S. (2000). Osmosensor and osmoregulator properties of the betaine carrier BetP from Corynebacterium glutamicum in proteoliposomes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 735-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlessinger, J. (2002). Ligand-induced, receptor-mediated dimerization and activation of EGF receptor. Cell 110, 669-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, J., Milpetz, F., Bork, P., and Ponting, C.P. (1998). SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 5857-5864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, S.C., Noegel, A.A., Oehme, F., Gerisch, G., and Simon, M.I. (1996). The hybrid histidine kinase DokA is part of the osmotic response system of Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 15, 3880-3889. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutoh, K. (1993). A transformation vector for Dictyostelium discoideum with a new selectable marker bsr. Plasmid 30, 150-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M.C., Muhia, D.K., Baker, D.A., Mondragon, A., Schaap, P.B., and Kelly, J.M. (1999). Trypanosoma cruzi adenylyl cyclase is encoded by a complex multigene family. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 104, 205-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer, J.J., Sunahara, R.K., Gilman, A.G., and Sprang, S.R. (1997). Crystal structure of the catalytic domains of adenylyl cyclase in a complex with Gsalpha. GTPgammaS. Science 278, 1907-1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevelein, J.M., Beullens, M., Honshoven, F., Hoebeeck, G., Detremerie, K., Griewel, B., den Hollander, J.A., and Jans, A.W. (1987a). Regulation of the cAMP level in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the glucose-induced cAMP signal is not mediated by a transient drop in the intracellular pH. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133, 2197-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thevelein, J.M., Beullens, M., Honshoven, F., Hoebeeck, G., Detremerie, K., Griewel, B., den Hollander, J.A., and Jans, A.W. (1987b). Regulation of the cAMP level in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the glucose-induced cAMP signal is not mediated by a transient drop in the intracellular pH. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133, 2197-2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urao, T., Yakubov, B., Satoh, R., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., Seki, M., Hirayama, T., and Shinozaki, K. (1999). A transmembrane hybrid-type histidine kinase in Arabidopsis functions as an osmosensor. Plant Cell 11, 1743-1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heide, T., and Poolman, B. (2000). Osmoregulated ABC-transport system of Lactococcus lactis senses water stress via changes in the physical state of the membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7102-7106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Es, S., Virdy, K.J., Pitt, G.S., Meima, M., Sands, T.W., Devreotes, P.N., Cotter, D.A., and Schaap, P. (1996). Adenylyl cyclase G, an osmosensor controlling germination of Dictyostelium spores. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 23623-23625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virdy, K.J., Sands, T.W., Kopko, S.H., van Es, S., Meima, M., Schaap, P., and Cotter, D.A. (1999). High cAMP in spores of Dictyostelium discoideum: association with spore dormancy and inhibition of germination. Microbiology 145, 1883-1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, G., and Herring, F.G. (1980). The lipid composition and membrane fluidity of Dictyostelium discoideum plasma membranes at various stages during differentiation. J. Lipid. Res. 21, 681-686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E.M., and Chinkers, M. (1995). Identification of sequences mediating guanylyl cyclase dimerization. Biochemistry 34, 4696-4701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood, J.M. (1999). Osmosensing by bacteria: signals and membrane-based sensors. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 230-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H., Olshevskaya, E., Duda, T., Seno, K., Hayashi, F., Sharma, R.K., Dizhoor, A.M., and Yamazaki, A. (1999). Activation of retinal guanylyl cyclase-1 by Ca2+-binding proteins involves its dimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 15547-15555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G., Liu, Y., Ruoho, A.E., and Hurley, J.H. (1997). Structure of the adenylyl cyclase catalytic core. Nature 386, 247-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zischka, H., Oehme, F., Pintsch, T., Ott, A., Keller, H., Kellermann, J., and Schuster, S.C. (1999). Rearrangement of cortex proteins constitutes an osmoprotective mechanism in Dictyostelium. EMBO J. 18, 4241-4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]