Abstract

During meiosis in the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa, unpaired genes are identified and silenced by a process known as meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA (MSUD). Previous work has uncovered six proteins required for MSUD, all of which are also essential for meiotic progression. Additionally, they all localize in the perinuclear region, suggesting that it is a center of MSUD activity. Nevertheless, at least a subset of MSUD proteins must be present inside the nucleus, as unpaired DNA recognition undoubtedly takes place there. In this study, we identified and characterized two new proteins required for MSUD, namely SAD-4 and SAD-5. Both are previously uncharacterized proteins specific to Ascomycetes, with SAD-4 having a range that spans several fungal classes and SAD-5 seemingly restricted to a single order. Both genes appear to be predominantly expressed in the sexual phase, as molecular study combined with analysis of publicly available mRNA-seq datasets failed to detect significant expression of them in the vegetative tissue. SAD-4, like all known MSUD proteins, localizes in the perinuclear region of the meiotic cell. SAD-5, on the other hand, is found in the nucleus (as the first of its kind). Both proteins are unique compared to previously identified MSUD proteins in that neither is required for sexual sporulation. This homozygous-fertile phenotype uncouples MSUD from sexual development and allows us to demonstrate that both SAD-4 and SAD-5 are important for the production of masiRNAs, which are the small RNA molecules associated with meiotic silencing.

Keywords: Illumina/Solexa sequencing, meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA (MSUD), Neurospora crassa, RNA interference (RNAi), small RNAs

EUKARYOTIC genomes are protected from viruses and transposons by a variety of defenses, many of which are based on RNA interference (RNAi). In a typical RNA silencing process, a double-stranded RNA is cleaved into small RNAs of 21–25 nt by an RNase III enzyme known as Dicer (Chang et al. 2012). An Argonaute-containing complex incorporates these small RNA species and uses them to guide transcriptional or post-transcriptional gene silencing.

Neurospora crassa, a filamentous fungus, is protected by at least two RNA silencing processes. The first process, called quelling (Romano and Macino 1992), defends the N. crassa genome from repetitive elements such as transposons (Nolan et al. 2005). The quelling machinery may also play an important role in rDNA stability and DNA damage response (Cecere and Cogoni 2009; Lee et al. 2009). The second defense process, known as meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA (MSUD) (Shiu et al. 2001), works specifically in meiotic cells and silences genes that are not paired between homologous chromosomes (Kelly and Aramayo 2007; Chang et al. 2012). Because parental genomes are likely to have differentially located transposons, MSUD is well suited to protect an organism from their amplification during meiosis.

In N. crassa, meiosis and sexual spore (ascospore) formation take place in specialized sac cells (asci). During homolog pairing, MSUD scans for the presence of unpaired DNA. If such unpaired DNA is detected, MSUD will silence the expression of this and all homologous copies. For example, if an extra copy of Ascospore maturation-1 (asm-1+) (Aramayo and Metzenberg 1996) is placed at an ectopic location in one parent but not the other, all copies of this gene (paired or unpaired) are silenced during sexual development, resulting in the production of white and inviable ascospores (Shiu et al. 2001). MSUD appears to be a robust mechanism and additional genes have been successfully used as reporting markers for its activity. These include actin (act+) and β-tubulin (bmlR), whose unpairings result in the abortion of most asci, and Round spore (r+), whose unpairing leads to the production of round ascospores (instead of spindle-shaped ones).

After an unpaired DNA is detected, the working model of MSUD holds that an aberrant RNA (aRNA) is transcribed from the unpaired region. This aRNA is then transported to the perinuclear region, where it encounters at least six known MSUD proteins (five of which are related to other RNAi processes). These include SAD-1, an RNA-directed RNA polymerase thought to turn an aRNA into a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) (Shiu and Metzenberg 2002); SAD-3, a helicase that may help SAD-1 form dsRNAs (Hammond et al. 2011a); DCL-1, a Dicer protein that cleaves a dsRNA into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) (Alexander et al. 2008); QIP, an exonuclease that processes siRNAs into single strands (Lee et al. 2010a; Xiao et al. 2010); SMS-2, an Argonaute protein that uses siRNAs to target complementary mRNAs (Lee et al. 2003); and SAD-2, which is the only uncommon RNA silencing protein listed here and may serve as a scaffold for other MSUD proteins in the perinuclear region (Shiu et al. 2006). All six of these proteins colocalize in the nuclear periphery, suggesting that they are members of a silencing complex.

While significant progress has been made in deciphering the MSUD processes outside of the nucleus, little is known about what happens inside of it. And although every reported MSUD protein is known to be required for both sexual development and silencing, their exact relationship remains an enigma. In this study, we have identified two novel components of the MSUD machinery and filled in some of the gaps in our knowledge of this unique silencing mechanism.

Materials and Methods

Fungal manipulation and genotypic information

Standard Neurospora protocols were used throughout this work (http://www.fgsc.net/Neurospora/NeurosporaProtocolGuide.htm). Fertilization of designated female (fl) strains and ascospore quantification were performed as described (Hammond et al. 2011a). Strain names and genotypes are listed in Table 1. Genetic markers and knockouts used in this study are originated from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (FGSC) (McCluskey et al. 2010) and the Neurospora Functional Genomics Group (Colot et al. 2006), and their descriptions can be found in the e-Compendium (http://www.bioinformatics.leeds.ac.uk/~gen6ar/newgenelist/genes/gene_list.htm).

Table 1. Strains used in this study.

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| F1-05 | fl a |

| F2-01 | fl A |

| F2-14 | fl a |

| F2-25 | rid his-3+::asm-1+; fl; asm-1Δ::mtr+ A |

| F2-27 | rid rΔ::hph; fl a |

| F2-29 | rid rΔ::hph; fl A |

| F2-35 | his-3::act+; fl A |

| F2-36 | his-3::bmlR; fl A |

| F2-37 | his-3::act+; fl a |

| F2-38 | his-3::bmlR; fl a |

| F3-24 | rid his-3+::asm-1+; fl; asm-1Δ::hph a |

| F5-23 | fl A |

| F5-32 | sad-4Δ::hph fl A |

| F5-33 | sad-4Δ::hph fl A |

| F5-35 | fl a |

| F5-36 | fl; sad-5Δ::hph a |

| F5-37 | fl; sad-5Δ::hph a |

| F5-38 | rΔ::hph; sad-4Δ::hph fl A |

| F5-39 | rΔ::hph; fl A |

| P3-07 | Oak Ridge wild type (WT) A |

| P3-08 | Oak Ridge wild type (WT) a |

| P3-25 | mep sad-1Δ::hph a |

| P8-18 | mep sad-1Δ::hph A |

| P11-43 | sad-4Δ::hph a |

| P11-46 | sad-4Δ::hph A |

| P12-01 | rΔ::hph A |

| P12-02 | rΔ::hph a |

| P13-22 | rid his-3+::rfp-sad-4; sad-4Δ::hph a |

| P15-14 | rid his-3; mus-52Δ::bar; gfp-sms-2::hph A |

| P17-57 | sad-5Δ::hph A |

| P17-58 | sad-5Δ::hph a |

| P17-59 | rΔ::hph; sad-4Δ::hph a |

| P17-60 | rΔ::hph; sad-4Δ::hph a |

| P17-61 | sad-4Δ::hph A |

| P17-62 | sad-4Δ::hph a |

| P17-63 | sad-4Δ::hph a |

| P17-64 | a |

| P17-65 | A |

| P17-66 | sad-5Δ::hph A |

| P17-67 | sad-5Δ::hph a |

| P17-68 | a |

| P17-69 | sad-5Δ::hph A |

| P17-70 | rΔ::hph; sad-5Δ::hph A |

| P17-71 | rΔ::hph; sad-5Δ::hph A |

| P18-55 | rid his-3+::rfp-sad-2; gfp-sad-5 a |

| P18-57 | rid his-3+::rfp-sad-2; gfp-sad-5; inv sad-2RIP A |

Plasmid and strain construction

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study are listed in Supporting Information, Table S1. For construction of his-3+::rfp-sad-4, the predicted sad-4 (NCU01591.5) coding region was amplified and inserted into the N-terminal red fluorescent protein (RFP) tagging plasmid pMF334 (Freitag and Selker 2005). gfp-sad-5::hph was constructed with double-joint polymerase chain reactions (DJ-PCR), essentially as described (Hammond et al. 2011b). The complementation test described by Shiu et al. (2006) (e.g., sad-2-gfp rescues the barren phenotype of a sad-2–null cross) is not possible here because neither sad-4 nor sad-5 is required for fertility. Nevertheless, the two aforementioned fluorescent proteins are not known to accumulate where SAD-4 and SAD-5 are localized.

Photography and microscopy

For photography of perithecia (fruiting bodies) and asci, a Canon PowerShot S3 IS camera was employed (in combination with a VanGuard 1274ZH or 1231CM microscope). For fluorescent microscopy, Zeiss LSM710 and Olympus BX61 were used. Perithecial sample preparation and GFP/RFP/DAPI visualization were essentially as described (Alexander et al. 2008; Xiao et al. 2010).

Sequence analysis

Accession or genome database numbers for sequences used in this study are listed in Table S2. The protein sequences of SAD-4 (NCU01591.5) and SAD-5 (NCU06147.5) are available from version 10 of the N. crassa genome database (Galagan et al. 2003; http://www.broadinstitute.org/annotation/genome/neurospora/MultiHome.html). These were used to predict their molecular weights with the Compute pI/Mw tool (http://web.expasy.org/compute_pi/) and to search the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Conserved Domain Database (CDD v.3.03) (Marchler-Bauer et al. 2010) for known domains. To identify putative homologs, these sequences were used to search the NCBI protein database (nr) with BLASTP 2.2.26+ and nucleotide collection (nr/nt) with TBLASTN 2.2.26+ (Altschul et al. 1997). Neurospora discreta homologs were identified and obtained from the Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute website (http://genome.jgi.doe.gov/). To identify conserved amino acids among the SAD-4 or SAD-5 homologs, alignments were created with Clustal W (Thompson et al. 1994) in BioEdit (Hall 1999). Similarity was determined using the Blosum62 similarity matrix.

Phylogenetic trees

SAD-4 and SAD-5 phylogenetic trees were constructed from Clustal W-based alignments of amino acid sequences (Table S2) with MEGA5 (Tamura et al. 2011) using the following parameters: (1) neighbor joining (Saitou and Nei 1987), (2) bootstrapping: 1000 replicates (Felsenstein 1985), (3) p-distance substitution (Nei and Kumar 2000), and (4) gap elimination. Taxonomic classifications were obtained from the NCBI taxonomy database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/taxonomy).

Small RNA sequencing and analysis

Crosses were performed on Neurospora crossing medium (Westergaard and Mitchell 1947) overlaid with a single layer of Miracloth (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Five days after fertilization, perithecia were scraped from the Miracloth with a razor blade, weighed, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. A total RNA sample was purified from ∼0.8 g of fungal tissue with TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and small RNAs were purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Small RNA library preparation and sequencing was performed by the University of Missouri DNA Core. Essentially, the TruSeq Small RNA Sample Preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego) was used to prepare indexed small RNA libraries from PAGE-purified small RNAs (15–35 nt). Four libraries were combined and sequenced by the Illumina’s HiSeq 2000 sequencing system, and the raw reads were divided into separate files based on their index. These data are available through the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database (SRX244308, SRX244469, SRX244665, and SRX244676).

The 3′ adapter sequences were trimmed from the small RNA reads with Cutadapt v.1.0 (Martin 2011). Reads ≥14 nt were aligned to the N. crassa genome (Galagan et al. 2003). Alignments were performed with Bowtie v.0.12.7 (Langmead et al. 2009) and only 18–30 nt reads with no mismatches to the reference genome were included in our final analysis. An overview of the sequencing and alignment data are provided in Table S3.

Results

Identification of sad-4Δ and sad-5Δ deletion strains as semidominant MSUD suppressors

Using the high-throughput reverse-genetic screen described by Hammond et al. (2011a), we identified four additional strains in the N. crassa knockout library (Colot et al. 2006) that appeared to be MSUD-deficient. These strains correspond to the putative deletion mutants (in both mating types) of NCU01591 (FGSC 13237 and 13238) and NCU06147 (FGSC 17863 and 17864).

To verify that NCU01591Δ and NCU06147Δ truly suppress MSUD, the aforementioned knockout strains were isolated from the library plates and their deletions were confirmed with standard polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays. The knockout mutants were then individually tested for their ability to suppress MSUD in crosses with four different MSUD-tester strains, which were designed to create the meiotic unpairing of either actin (::act+), Ascospore maturation-1 (asm-1Δ), β-tubulin (::bmlR), or Round spore (rΔ). Unpairing of these genes leads to abnormal sexual phenotypes (lollipop asci, white ascospores, elongated asci, and round ascospores, respectively) unless MSUD is suppressed (Shiu et al. 2001). When an NCU01591Δ strain (P11-43) was crossed to the four testers, MSUD suppression was seen in each case (Table 2). On the other hand, when a similar experiment was performed with an NCU06147Δ strain (P17-57), silencing was suppressed in three of the four test crosses but not the one containing rΔ (Table 2; F2-27 × P17-57). This is reminiscent of the observation by Raju et al. (2007), where the MSUD suppressors encoded by Sk-2 and Sk-3 also had no effect on rΔ. Accordingly, we have assigned the names suppressor of ascus dominance-4 and -5 (sad-4 and sad-5) to genes NCU01591 and NCU06147, respectively.

Table 2. sad-4Δ and sad-5Δ act as semidominant suppressors of MSUD.

| Experiment 1 | ::act+ (F2-35) | ::bmlR (F2-36) | asm-1Δ (F2-25) (%) | rΔ (F2-29) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (P3-08) | 36.0 × 103 | 0.6 × 103 | 2.7 | 0.8 |

| sad-4Δ (P11-43) | 173.2 × 103 | 55.9 × 103 | 61.6 | 52.4 |

| sad-1Δ (P3-25) | 285.0 × 103 | 107.4 × 103 | 81.0 | 99.0 |

| (spores) | (spores) | (black) | (football) | |

| Experiment 2 | ::act+ (F2-37) | ::bmlR (F2-38) | asm-1Δ (F3-24) (%) | rΔ (F2-27) (%) |

| WT (P3-07) | 28.8 × 103 | 0.6 × 103 | 0.7 | 0.0 |

| sad-5Δ (P17-57) | 118.9 × 103 | 12.0 × 103 | 15.9 | 0.4 |

| sad-1Δ (P8-18) | 342.9 × 103 | 398.7 × 103 | 83.4 | 98.7 |

| (spores) | (spores) | (black) | (football) |

Each MSUD tester (::act+, ::bmlR, asm-1Δ, or rΔ) is designed to cause the unpairing of a reporter gene during meiosis. When MSUD is proficient (i.e., tester × WT), these unpairings lead to the reduced production of black American football (spindle)-shaped ascospores. When MSUD is suppressed, the phenotypes can be partially (e.g., tester × sad-4Δ/5Δ) or near-fully (e.g., tester × sad-1Δ) restored to normal, depending on the strength of the suppressor.

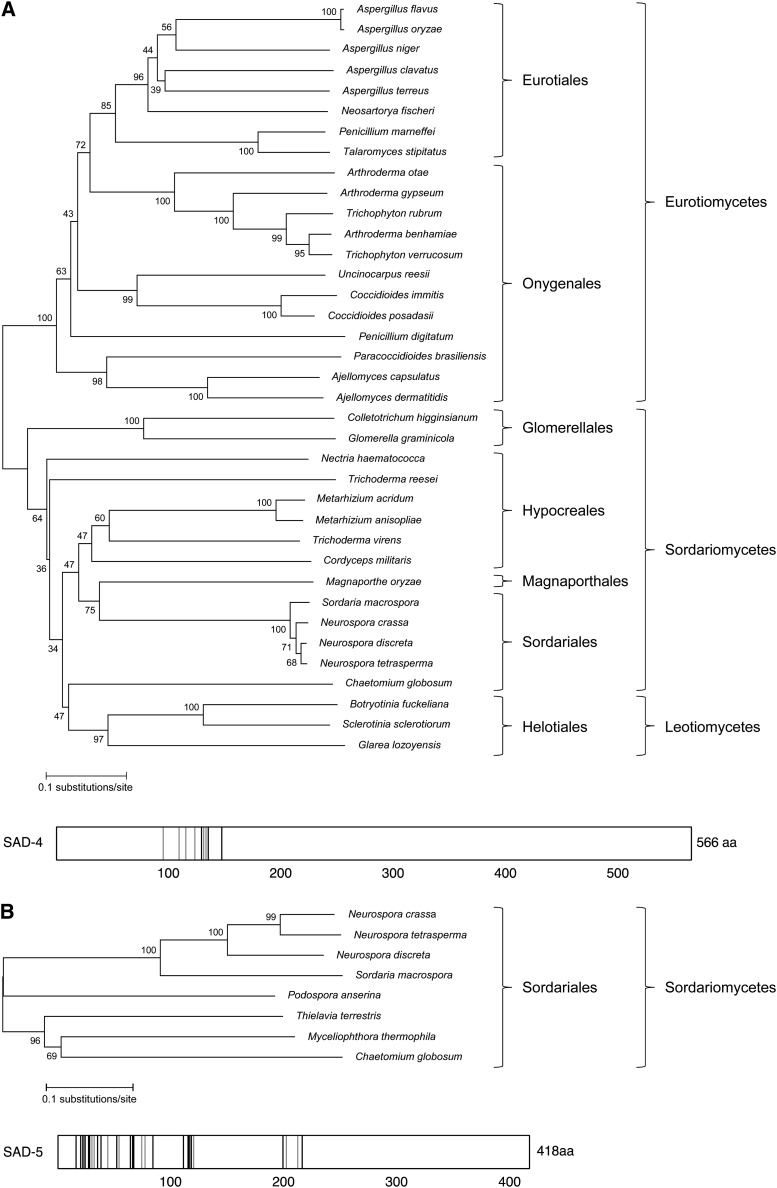

SAD-4 is a novel protein found in three classes of Ascomycete fungi

The translated SAD-4 sequence consists of 566 amino acids with a molecular weight of 60.5 kDa. Although SAD-4 does not contain known functional domains, its homologs can be found among three classes of Ascomycete fungi: Sordariomycetes (e.g., Neurospora), Leotiomycetes (e.g., Sclerotinia), and Eurotiomycetes (e.g., Aspergillus) (Figure 1A). However, SAD-4 is not ubiquitous in these fungal classes as database searches and syntenic analyses failed to reveal similar sequences in Gibberella zeae, a Sordariomycete thought to be capable of MSUD (Son et al. 2011), and Aspergillus nidulans, a Eurotiomycete whose sad genes are degenerating (Hammond et al. 2008). Other exceptions include the dung-inhabiting Podospora anserina as well as the thermophilic biomass-degrading Thielavia terrestris and Myceliophthora thermophila. This is particularly interesting because although these three lack a SAD-4 sequence, they are among the relatively few fungi that encode a SAD-5 homolog (see below).

Figure 1.

SAD-4 homologs are present in a wide range of Ascomycete fungi, while SAD-5 homologs are restricted to a single order. (A, top) Phylogenetic tree of SAD-4 homologs. Sequence accession numbers are listed in Table S2. Numbers next to branches indicate the percentage of bootstrap support. (Bottom) Conserved amino acids of SAD-4. Strictly conserved residues are solid (identical) and shaded (similar). See Figure S1 for sequence alignment. (B) Phylogenetic tree and conserved amino acids of SAD-5 homologs. The Thielavia terrestris SAD-5 sequence is incomplete at both ends. See Figure S2 for sequence alignment.

The aforementioned SAD-4 homologs appear to be orthologous (separated by speciation) rather than paralogous (separated by duplication). This notion is supported by the syntenic finding that many of the sad-4–like sequences were found adjacent to hsp60, a highly conserved heat-shock protein-encoding gene present in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms (Johnson et al. 1989). These include the sad-4 homolog identified in Aspergillus terreus, which is one of the most distant species from N. crassa in our phylogenetic analysis.

Despite their orthologous nature, SAD-4 sequences are quite diverse. For example, while the N. crassa and N. tetrasperma orthologs are 99% alike, the N. crassa and Trichoderma reesei orthologs share a similarity level of only 21%. Nevertheless, a highly conserved region (positions 94–147) exists among these SAD-4 orthologs from three different classes of fungi (Figure 1A and Figure S1). The conservation of these amino acids suggests that they could constitute an important functional motif.

SAD-5 is a novel protein restricted to a single order of Sordariomycete fungi

sad-5 encodes a 418-aa (47.8 kDa) polypeptide with no known conserved domains. A search of the NCBI and the N. discreta genome databases identified seven SAD-5 homologs (Figure 1B). Syntenic analysis indicated that SAD-5, like SAD-4, is orthologous to its homologs.

The Sordariales is one of several orders that fall under the class Sordariomycetes. The failure to identify SAD-5 homologs in any other Sordariomycete order suggests that SAD-5 is specific to the Sordariales. To investigate this possibility more closely, the most likely locations of sad-5 were identified in four fungi from other Sordariomycete orders by searching their genomes with sad-5 flanking sequences. Analysis of these regions in Glomerella graminicola (of Glomerellales), Magnaporthe oryzae (of Magnaporthales), G. zeae (of Hypocreales), and Grosmannia clavigera (of Ophiostomatales) showed that synteny collapses near the predicted location of sad-5 in each case, suggesting that these species have indeed lost their sad-5 orthologs.

Although the SAD-5 orthologs appear to be specific to the Sordariales, a wide range of sequence variation can still be found among them. For example, N. crassa SAD-5 is 28% and 90% similar to its counterparts in T. terrestris and N. tetrasperma, respectively. Despite this variability, we identified a number of consensus amino acids among the SAD-5 sequences, with a clustering of conserved residues toward the N-terminal end (Figure 1B and Figure S2).

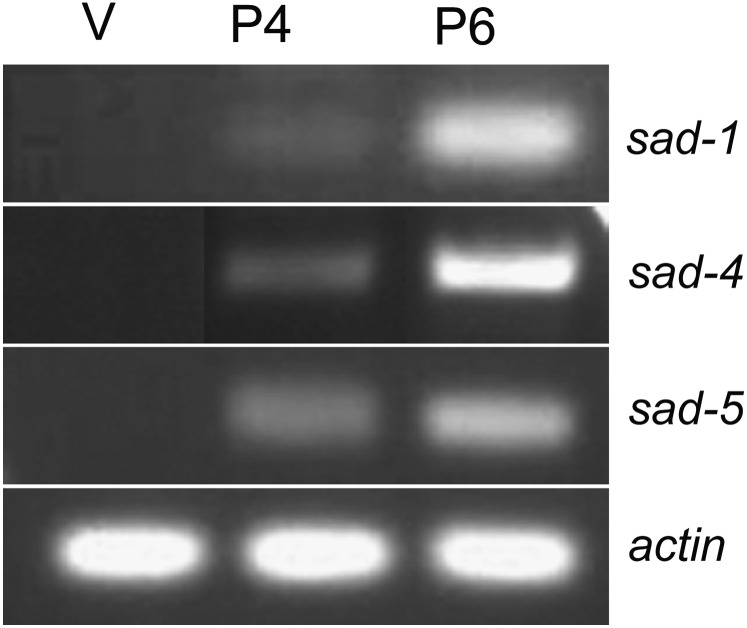

sad-4 and sad-5 are expressed during the sexual cycle

Two MSUD proteins, DCL-1 and QIP, are known to have roles in another RNA silencing process known as quelling (Catalanotto et al. 2004; Maiti et al. 2007). Since quelling, unlike MSUD, is active in the somatic tissue, a gene involved in both processes would need to be expressed in both vegetative and sexual phases of the fungal life cycle. We examined the vegetative levels of sad-4 and sad-5 transcripts by two different methods. First, we analyzed several N. crassa mRNA-Seq datasets from the NCBI SRA database (Ellison et al. 2011). Vegetative expression levels of sad-4 and sad-5, like those found in other MSUD genes, were near the limit of detection in all datasets (reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads, RPKM = 0.01–0.14; Table 3). In contrast, genes required for quelling (whether or not they are also required for MSUD) were expressed at much higher levels (RPKM = 3.81–63.72). These data suggest that sad-4 and sad-5 are barely active, if at all, during the vegetative phase. Second, we attempted to detect sad-4 and sad-5 mRNAs from vegetative and sexual tissues. In agreement with the database analysis, we were able to amplify sad-4 and sad-5 cDNA sequences only from the sexual tissue (Figure 2), demonstrating once again that the expression levels of these genes are very low during the vegetative phase. The low vegetative expression of these sad genes predicts that their deletion should have no effect on the vegetative phenotype. Accordingly, morphological analysis and growth assays revealed no significant differences between a sad-4Δ or sad-5Δ mutant and wild type (Figure S3).

Table 3. Expression of RNA silencing genes during the vegetative phase.

| Function | Gene | Expression (RPKM) |

|---|---|---|

| Housekeeping | actin | 1634.1998 |

| β-tubulin | 685.3888 | |

| Quelling | dcl-2 | 3.9767 |

| qde-1 | 11.1222 | |

| qde-2 | 63.7201 | |

| qde-3 | 5.1974 | |

| Quelling/MSUD | dcl-1 | 3.8117 |

| qip | 10.3140 | |

| MSUD | sad-1 | 0.0736 |

| sad-2 | 0.0088 | |

| sad-3 | 0.0213 | |

| sad-4 | 0.1357 | |

| sad-5 | 0.0123 | |

| sms-2 | 0.0225 |

Neurospora vegetative mRNA-seq datasets were obtained from the NCBI SRA database (SRX033295, SRX033369, SRX033410, SRX033477, SRX033487, SRX033498, and SRX037168–037170) and aligned to predicted N. crassa transcripts with Bowtie (Langmead et al. 2009). RPKM, reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (Mortazavi et al. 2008).

Figure 2.

sad-4 and sad-5 are expressed in the sexual tissue. sad-4 and sad-5 transcripts, like those from sad-1, can be detected in the sexual but not vegetative tissue. RT-PCR products from various sad genes and actin (control) are shown (from top: 250 bp, 1054 bp, 369 bp, and 227 bp). RNAs from vegetative (V; P3-07) and 4/6-day perithecial (P4 and P6; F1-05 × P3-07) preparations were used for the amplification.

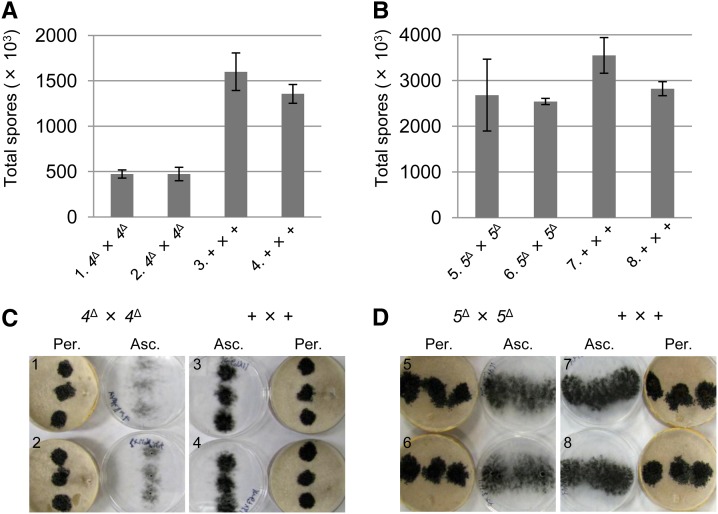

Neither SAD-4 nor SAD-5 is essential for sexual development

All known MSUD proteins thus far are required for sexual development. For example, crosses lacking either dcl-1 or qip produce barren perithecia with no asci (Alexander et al. 2008; Xiao et al. 2010). On the other hand, while sad-1–, sad-2–, or sad-3–null perithecia are also barren, they abort at a later stage, some time after the production of elongated asci (Shiu et al. 2001, 2006; Hammond et al. 2011a). Predicting that perithecia lacking sad-4 or sad-5 would follow one of these two patterns, crosses homozygous for either sad-4Δ or sad-5Δ were performed. Surprisingly, unlike previously characterized MSUD genes, neither sad-4 nor sad-5 is required for ascospore production (Figure 3), although the loss of sad-4 did correlate with a threefold decrease in the total number of shot progeny (Figure 3, A and C).

Figure 3.

Crosses homozygous for sad-4Δ or sad-5Δ are fertile. (A) Deletion of sad-4 from both parents reduces, but not prevents, ascospore production. (B) Deletion of sad-5 from both parents does not affect ascospore production. (C and D) Pictures of crossing plates. Lids have been removed and placed next to the crossing plates to show both perithecial (Per.) and ascospore (Asc.) levels. Note that while sad-4–null and wild-type crosses have similar perithecial levels, their ascospore levels are different. Three replicates were performed for each cross, with the error bar representing the standard deviation. 4Δ and 5Δ, deletion of sad-4 and sad-5, respectively. +, wild type at sad loci. Cross 1, F5-32 × P17-62. Cross 2, F5-33 × P17-63. Cross 3, F2-01 × P3-08. Cross 4, F2-01 × P17-64. Cross 5, F5-36 × P17-66. Cross 6, F5-37 × P17-69. Cross 7, F2-14 × P3-07. Cross 8, F5-35 × P17-65.

In an attempt to identify the defect leading to reduced ascospore production in crosses homozygous for sad-4Δ, their perithecial development was examined over 13 days. No appreciable differences in perithecial morphology and abundance were observed over this time frame between sad-4Δ and wild-type crosses (Figure S4). This suggests that the sporulation defect may lie within the perithecia. Accordingly, perithecial dissection revealed that crosses homozygous for sad-4Δ have roughly twice the amount of aborted asci (Figure S4). Thus a high ascus abortion rate is the likely cause of reduced ascospore production in a sad-4–null cross.

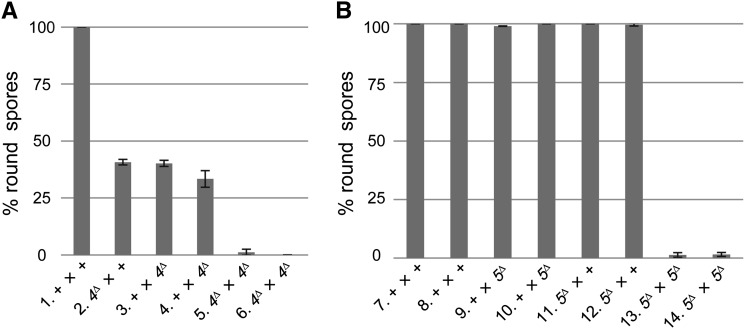

Crosses homozygous for sad-4Δ or sad-5Δ are completely deficient in MSUD

Because all previously characterized MSUD proteins are required for sexual development, a meiotic silencing assay has typically involved a heterozygous cross between deletion strains, with one parent lacking an MSUD gene (e.g., sad-1) and the other lacking a gene important for ascospore development (e.g., r). In such a “silencing the silencer” assay, the sad gene is itself unpaired and hence self-silenced, leading to the loss of (or decrease in) MSUD activity. sad-4Δ and sad-5Δ did not appear to be strong dominant suppressors of MSUD (as compared to sad-1Δ). This is especially true for the rΔ test crosses, where sad-4Δ and sad-5Δ suppress roughly half and none of the MSUD activity, respectively (Table 2). Since the two sad genes are dispensable for sexual development, it is possible to assay MSUD suppression in a homozygous sadΔ cross for the first time. In crosses homozygous for sad-4Δ or sad-5Δ, the silencing of an unpaired r+ appeared completely suppressed, demonstrating that these genes are indeed essential for MSUD (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

SAD-4 and SAD-5 are essential MSUD proteins. (A) A normal cross produces black American football (spindle)-shaped ascospores. In this study, crosses heterozygous for rΔ were examined. In an MSUD-proficient background, an unpaired r+ is silenced and nearly 100% of the progeny are round (cross 1). When both parents are deleted of sad-4+, progeny are predominantly normal (crosses 5 and 6), suggesting MSUD is suppressed. (B) Similarly, MSUD is suppressed in a sad-5–null background (crosses 13 and 14). Unlike sad-4Δ (crosses 2–4), sad-5Δ is not semidominant in a cross (crosses 9–12). Three replicates were performed for each heterozygous rΔ cross, with the error bar representing the standard deviation. WT, wild type at sad loci. Cross 1, F2-01 × P12-02. Cross 2, F5-32 × P12-02. Cross 3, F2-01 × P17-59. Cross 4, F2-01 × P17-60. Cross 5, F5-32 × P17-59. Cross 6, F5-33 × P17-60. Cross 7, F2-14 × P12-01. Cross 8, F5-35 × P12-01. Cross 9, F2-14 × P17-70. Cross 10, F5-35 × P17-71. Cross 11, F5-36 × P12-01. Cross 12, F5-37 × P12-01. Cross 13, F5-36 × P17-70. Cross 14, F5-37 × P17-71.

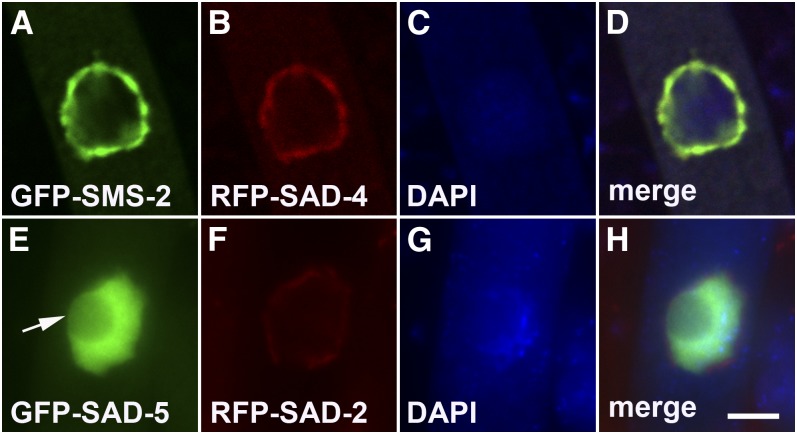

SAD-4 and SAD-5 localize in the perinuclear and nuclear regions, respectively

All previously characterized MSUD proteins (SAD-1/2/3, DCL-1, QIP, and SMS-2) colocalize around the nucleus during meiosis (Shiu et al. 2006; Alexander et al. 2008; Xiao et al. 2010; Hammond et al. 2011a), suggesting that they form an RNA-processing complex. Despite the fact that MSUD must also involve nuclear proteins (e.g., those that detect unpaired DNA), their discovery has remained elusive thus far. To determine the subcellular localization of SAD-4 and SAD-5, they were tagged with RFP and GFP, respectively. Like all known MSUD proteins, SAD-4 is found in the perinuclear region (Figure 5B). Moreover, it colocalizes with SMS-2, a component of the meiotic silencing complex described above (Figure 5D). SAD-5, unlike any MSUD protein reported before it, is localized diffusely in the nucleus (excluding the nucleolus) (Figure 5E).

Figure 5.

SAD-4 and SAD-5 localize in the perinuclear and nuclear regions, respectively. Micrographs illustrate prophase asci expressing (A–D) gfp-sms-2 and rfp-sad-4 (P15-14 × P13-22) and (E–H) gfp-sad-5 and rfp-sad-2 (P18-57 × P18-55). SAD-4 colocalizes with SMS-2, a component of the perinuclear MSUD complex that also includes SAD-2. SAD-5 localizes in the nucleus, excluding the nucleolus (arrow). Bar, 5 μm.

Deletion of sad-4 or sad-5 correlates with loss of masiRNAs

The involvement of RNA silencing proteins in MSUD, such as Dicer, Argonaute, and RdRP, suggests that this process is mediated by small RNAs. In a related work, we have identified and characterized MSUD-associated small interfering RNAs (masiRNAs) that correlate with the unpairing of r+ during meiosis (see Hammond et al. 2013, accompanying article in this issue). To determine if sad-4 or sad-5 deletion affects the production of r-specific masiRNAs, we prepared and sequenced small RNA libraries from perithecia of various crosses. The positive control (r-unpaired) cross, consistent with our previous result, produced abundant r-specific small RNAs mostly 21–27 nt in length (Figure 6A, blue). In contrast, the negative control (r-paired) cross produced a much lower level of r-specific small RNAs, which were uniformly distributed and likely mRNA degradation products (Figure 6A, purple). For the experimental (r-unpaired) crosses involving homozygous sad-4 or sad-5 deletion (Figure 6A, green and orange), the levels and size distributions of r-specific small RNAs were similar to the negative control where r was not silenced. These data suggest that SAD-4 and SAD-5 function upstream of masiRNA generation in the MSUD pathway.

Figure 6.

SAD-4 and SAD-5 are required for the generation of masiRNAs. Small RNA (sRNA) levels and lengths were determined for four different crosses. These included three r-unpaired crosses that were MSUD-proficient (blue; F5-39 × P3-08), sad-4–null (green; F5-38 × P17-62), or sad-5–null (orange; F5-36 × P17-71). The fourth cross was the r-paired control (purple; F2-01 × P3-08). (A) r-specific sRNAs do not accumulate when sad-4 or sad-5 is deleted, suggesting that the two genes are involved in masiRNA generation. (B and C) Deletion of either sad gene does not qualitatively affect milRNA/disiRNA levels. RNA levels are listed in reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (RPKM).

SAD-4 and SAD-5 are not required for milRNA and disiRNA biogenesis

MicroRNA-like RNAs (milRNAs) and dicer-independent small interfering RNAs (disiRNAs) are small RNA species that originated from hairpin and convergent transcripts, respectively (Lee et al. 2010b). Some of these molecules require known RNAi factors (e.g., Dicers and Argonaute) for their production. To determine if sad-4 and sad-5 are required for the biogenesis of milRNAs and disiRNAs, we examined their levels in crosses homozygous for sad-4Δ or sad-5Δ. We found that milRNA and disiRNA production was qualitatively unaffected when either of these sad genes was deleted (Figure 6, B and C). This observation is consistent with the notion that SAD-4 and SAD-5 are possibly specific for masiRNA generation during meiotic silencing.

Discussion

In this study, we have characterized two MSUD proteins that were identified with a recently developed reverse-genetic screen. This screen involves the transferring of conidial (asexual spore) suspensions of knockout strains to various MSUD testers, and sad-4Δ/sad-5Δ strains were first identified as candidates in crosses that were unpaired for asm-1+. sad-5Δ, like two other MSUD suppressors (Raju et al. 2007), does not dominantly suppress rΔ. It is unclear why some sadΔ strains are weaker dominant suppressors of MSUD, although one can speculate that certain sad genes may be expressed at a high level or have a long protein half-life, making it harder to silence them. It seems possible that one of these mechanisms (high expression or protein stability) could allow some repetitive elements to escape silencing should they become unpaired. Fortunately for N. crassa, there are at least two other surveillance mechanisms (quelling and repeat-induced point mutation) to keep them in check (Catalanotto et al. 2006).

SAD-4– and SAD-5–like proteins appear to be fungal specific and have no known motifs. Our report marks the first time they could be associated with a function (i.e., RNA silencing). Perhaps the most interesting aspect of our phylogenetic analysis is that SAD-4 is found in a broader range of fungi relative to SAD-5, with the latter appearing to be specific to a single order of Sordariomycete fungi. One possibility is that SAD-4 has a role in other cellular processes. This is consistent with our finding that although sad-4 is not absolutely required for sexual sporulation, its deletion from both parents correlates with increased ascus abortion. Additionally, it is interesting that some Sordariomycete fungi encode SAD-5 but not SAD-4, and the only other fungus in which MSUD has been experimentally demonstrated thus far (G. zeae) has neither. Perhaps SAD-4 and SAD-5 have mechanistic roles that are relatively species specific. For example, if defense against selfish genetic elements is a major driving force for adaptive change in MSUD, then its mechanism may be subject to the evolutionary arms race typical of host–parasite interactions (Obbard et al. 2009). If this is the case, SAD-4 and SAD-5 may represent N. crassa’s specific modifications of the MSUD mechanism.

The perinuclear localization of SAD-4 suggests that it may be involved in dsRNA production and/or masiRNA generation. Alternatively, it may assist the Argonaute protein in using masiRNAs to identify/destroy mRNA transcripts. In quelling, the lack of Argonaute (functioning downstream of small RNA generation) leads to the accumulation of siRNAs (Catalanotto et al. 2002). The fact that the absence of SAD-4 correlates with the loss of masiRNAs suggests that it must function upstream of their production.

SAD-5 is the first nuclear MSUD protein to be identified. SAD-5’s localization makes it tempting to speculate that it may be directly involved in the initial stages of MSUD, i.e., detecting unpaired DNA or producing/transporting the aRNA. Each of these possibilities is supported by the finding that masiRNAs do not accumulate in a sad-5\x{2013}null cross. To decipher the exact roles of SAD-4 and SAD-5 in gene silencing, additional research is needed (e.g., their influence on aRNA production, quelling, expression of other sad genes, and silencing of various unpaired loci).

This study demonstrates that masiRNAs are an important part of N. crassa’s silencing mechanism and that certain members of the MSUD machinery are indispensable for their production. The detection of masiRNAs (or the lack thereof) allows us to place a protein function upstream or downstream of their generation. In addition, all previously identified MSUD proteins are essential for ascospore production. It has been speculated that perhaps some degree of silencing constitutes a checkpoint in sexual development. The finding that SAD-4 and SAD-5 are not required for sporulation is a breakthrough in our understanding of MSUD, disputing a previous belief that this silencing process is absolutely coupled with sexual development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to James Birchler, members of the Shiu laboratory, University of Missouri Core Facilities, the Fungal Genetics Stock Center, the Neurospora Functional Genomics Group, and colleagues from our community for their help. We are pleased to acknowledge use of materials generated by P01 GM068087 “Functional Analysis of a Model Filamentous Fungus.” T.M.H. was supported by a Life Science Fellowship from the University of Missouri and a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (MCB1157942 to P.K.T.S.).

Note added in proof: See Hammond et al. 2013 (pp. 279–284) in this issue, for a related work.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: C.-ting Wu

Literature Cited

- Alexander W. G., Raju N. B., Xiao H., Hammond T. M., Perdue T. D., et al. , 2008. DCL-1 colocalizes with other components of the MSUD machinery and is required for silencing. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45: 719–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schäffer A. A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., et al. , 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramayo R., Metzenberg R. L., 1996. Meiotic transvection in fungi. Cell 86: 103–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalanotto C., Azzalin G., Macino G., Cogoni C., 2002. Involvement of small RNAs and role of the qde genes in the gene silencing pathway in Neurospora. Genes Dev. 16: 790–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalanotto C., Pallotta M., P. ReFalo, M. S. Sachs, L. Vayssie et al, 2004. Redundancy of the two dicer genes in transgene-induced posttranscriptional gene silencing in Neurospora crassa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24: 2536–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalanotto C., Nolan T., Cogoni C., 2006. Homology effects in Neurospora crassa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 254: 182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecere G., Cogoni C., 2009. Quelling targets the rDNA locus and functions in rDNA copy number control. BMC Microbiol. 9: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S. S., Zhang Z., Liu Y., 2012. RNA interference pathways in fungi: mechanisms and functions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 66: 305–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colot H. V., Park G., Turner G. E., Ringelberg C., Crew C. M., et al. , 2006. A high-throughput gene knockout procedure for Neurospora reveals functions for multiple transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 10352–10357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison C. E., Hall C., Kowbel D., Welch J., Brem R. B., et al. , 2011. Population genomics and local adaptation in wild isolates of a model microbial eukaryote. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 2831–2836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J., 1985. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 39: 783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag M., Selker E. U., 2005. Expression and visualization of red fluorescent protein (RFP) in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 52: 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Galagan J. E., Calvo S. E., Borkovich K. A., Selker E. U., Read N. D., et al. , 2003. The genome sequence of the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa. Nature 422: 859–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T. A., 1999 BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acid Symp. Ser. 41: 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond T. M., Bok J. W., Andrewski M. D., Reyes-Domínguez Y., Scazzocchio C., et al. , 2008. RNA silencing gene truncation in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 7: 339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond T. M., Xiao H., Boone E. C., Perdue T. D., Pukkila P. J., et al. , 2011a SAD-3, a putative helicase required for meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA, interacts with other components of the silencing machinery. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 1: 369–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond T. M., Xiao H., Rehard D. G., Boone E. C., Perdue T. D., et al. , 2011b Fluorescent and bimolecular-fluorescent protein tagging of genes at their native loci in Neurospora crassa using specialized double-joint PCR plasmids. Fungal Genet. Biol. 48: 279–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond T. M., Spollen W. G., Decker L. M., Blake S. M., Springer G. K., et al. , 2013. Identification of small RNAs associated with meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA. Genetics 194: 279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. B., Fearon K., Mason T., Jindal S., 1989. Cloning and characterization of the yeast chaperonin HSP60 gene. Gene 84: 295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly W. G., Aramayo R., 2007. Meiotic silencing and the epigenetics of sex. Chromosome Res. 15: 633–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B., Trapnell C., Pop M., Salzberg S. L., 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 10: R25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. W., Pratt R. J., McLaughlin M., Aramayo R., 2003. An argonaute-like protein is required for meiotic silencing. Genetics 164: 821–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. W., Millimaki R., Aramayo R., 2010a QIP, a component of the vegetative RNA silencing pathway, is essential for meiosis and suppresses meiotic silencing in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 186: 127–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. C., Chang S. S., Choudhary S., Aalto A. P., Maiti M., et al. , 2009. qiRNA is a new type of small interfering RNA induced by DNA damage. Nature 459: 274–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H. C., Li L., Gu W., Xue Z., Crosthwaite S. K., et al. , 2010b Diverse pathways generate microRNA-like RNAs and Dicer-independent small interfering RNAs in fungi. Mol. Cell 38: 803–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiti M., Lee H. C., Liu Y., 2007. QIP, a putative exonuclease, interacts with the Neurospora Argonaute protein and facilitates conversion of duplex siRNA into single strands. Genes Dev. 21: 590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchler-Bauer A., Lu S., Anderson J. B., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M. K., et al. , 2010. CDD: a Conserved Domain Database for the functional annotation of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: D225–D229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M., 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 17: 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- McCluskey K., Wiest A., Plamann M., 2010. The Fungal Genetics Stock Center: a repository for 50 years of fungal genetics research. J. Biosci. 35: 119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortazavi A., Williams B. A., McCue K., Schaeffer L., Wold B., 2008. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 5: 621–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nei M., Kumar S., 2000. Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics, Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan T., Braccini L., Azzalin G., De Toni A., Macino G., et al. , 2005. The post-transcriptional gene silencing machinery functions independently of DNA methylation to repress a LINE1-like retrotransposon in Neurospora crassa. Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 1564–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obbard D. J., Gordon K. H., Buck A. H., Jiggins F. M., 2009. The evolution of RNAi as a defence against viruses and transposable elements. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364: 99–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju N. B., Metzenberg R. L., Shiu P. K. T., 2007. Neurospora spore killers Sk-2 and Sk-3 suppress meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA. Genetics 176: 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano N., Macino G., 1992. Quelling: transient inactivation of gene expression in Neurospora crassa by transformation with homologous sequences. Mol. Microbiol. 6: 3343–3353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N., Nei M., 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4: 406–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu P. K. T., Metzenberg R. L., 2002. Meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA: properties, regulation, and suppression. Genetics 161: 1483–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu P. K. T., Raju N. B., Zickler D., Metzenberg R. L., 2001. Meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA. Cell 107: 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiu P. K. T., Zickler D., Raju N. B., Ruprich-Robert G., Metzenberg R. L., 2006. SAD-2 is required for meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA and perinuclear localization of SAD-1 RNA-directed RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 2243–2248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son H., Min K., Lee J., Raju N. B., Lee Y. W., 2011. Meiotic silencing in the homothallic fungus Gibberella zeae. Fungal Biol 115: 1290–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Peterson D., Peterson N., Stecher G., Nei M., et al. , 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28: 2731–2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J., 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22: 4673–4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westergaard M., Mitchell H. K., 1947. Neurospora V. A synthetic medium favoring sexual reproduction. Am. J. Bot. 34: 573–577. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H., Alexander W. G., Hammond T. M., Boone E. C., Perdue T. D., et al. , 2010. QIP, a protein that converts duplex siRNA into single strands, is required for meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA. Genetics 186: 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.