Abstract

Lipocalin 24p3 (24p3) is a neutrophil secondary granule protein. 24p3 is also a siderocalin, which binds several bacterial siderophores. It was therefore proposed that synthesis and secretion of 24p3 by stimulated macrophages or release of 24p3 upon neutrophil degranulation sequesters iron-laden siderophores to attenuate bacterial growth. Accordingly, 24p3-deficient mice are susceptible to bacterial pathogens whose siderophores would normally be chelated by 24p3. Specific granule deficiency (SGD) is a rare congenital disorder characterized by complete absence of proteins in secondary granules. Neutrophils from SGD patients, who are prone to bacterial infections, lack normal functions but the potential role of 24p3 in neutrophil dysfunction in SGD is not known. Here we show that neutrophils from 24p3−/− mice are defective in many neutrophil functions. Specifically, neutrophils in 24p3−/− mice do not extravasate to sites of infection and are defective for chemotaxis. A transcriptome analysis revealed that genes that control cytoskeletal reorganization are selectively suppressed in 24p3−/− neutrophils. Additionally, small regulatory RNAs (miRNAs) that control upstream regulators of cytoskeletal proteins are also increased in 24p3−/− neutrophils. Further, 24p3−/− neutrophils failed to phagocytose bacteria, which may account for the enhanced sensitivity of 24p3−/− mice to both intracellular (Listeria monocytogenes) and extracellular (Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus) pathogens. Listeria does not secrete siderophores and additionally, the siderophore secreted by Candida is not sequestered by 24p3. Therefore, the heightened sensitivity of 24p3−/− mice to these pathogens is not due to sequestration of siderophores limiting iron availability, but is a consequence of impaired neutrophil function.

Keywords: Lipocalin 24p3, neutrophils, Listeria monocytogenes, Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus

Introduction

Neutrophils provide the first line of defense against bacterial infections and are responsible for ingestion, killing, and digestion of bacteria. Neutrophils differentiate mainly in the bone marrow and are classified based on their morphology: promyelocytes>myelocytes>meta-myelocytes>band cells>segmented cells (1). Neutrophil granules are classified into four subsets based on their location, appearance and content: Primary or Azurophilic granules (peroxidases positive); Secondary or Specific granules (peroxidase negative); Tertiary or Gelatinase granules; and Secretory vesicles (2–4).

Lipocalin 24p3, also known as Lipocalin 2, is a neutrophil secondary granule protein. 24p3 is a member of the Lipocalin family of over 20 small, secreted proteins that share a highly conserved 3-dimensional folding pattern (an eight-stranded antiparallel β sheet that forms a squat β barrel cavity), which is a receptor for small molecular weight ligands. Lipocalins bind, transport, and deliver such ligands to specific cells, thereby eliciting a plethora of responses (5–8). 24p3 was first identified in mouse embryonic fibroblasts transformed with SV40 large T-antigen (9, 10). Our studies, as well as those from other laboratories, identified several functions for 24p3, which include: its being an acute phase response mediator (11), its importance for tissue involution (12,13), kidney morphogenesis (8, 14), erythropoiesis (15), cell death (16–20), and as a host-defense protein (21, 22).

Since 24p3 binds bacterial siderophores, which are essential for bacterial iron uptake, it was proposed that 24p3 secreted by stimulated macrophages or released upon neutrophil degranulation functions as a bacteriostat (7, 23). Specifically, 24p3 binds catecholate or mixed phenolate type siderophores. Not surprisingly, 24p3−/− mice are sensitive to E.coli or M.tb infections (15, 22, 24). However, certain strains of E.coli and S.aureus modify the siderophores or secrete more than one type of siderophore to evade capture by 24p3 (25). In this regard, the generality of siderophore sequestration by 24p3 in host defense is questionable. Further, does 24p3 play a role in innate immunity against pathogens that do not depend on siderophores for iron acquisition?

In this report, we examined the consequences of the absence of 24p3 for a variety of neutrophil functions. Unexpectedly, we found that neutrophils derived from 24p3−/− mice are defective for chemotaxis. To establish a comprehensive view of the molecular changes that might contribute to this defect, we performed global transcriptome analysis, which revealed that 24p3−/− neutrophils are unable to mount effective intracellular signaling in response to chemoattractant stimuli and consequently fail to undergo cytoskeletal reorganization. Specifically, we found that RhoA is inactive despite chemoattractant stimulation. As a result the downstream targets of RhoA signaling are also inactive. Interestingly, microRNAs that target transcription factors whose downstream targets include some of the regulators of cytoskeletal reorganization are also increased in 24p3−/− neutrophils. Thus, upregulation of the small regulatory RNAs together with downregulation of the Rho GTPases that induce actin remodeling converge to reduce chemotaxis. Additionally, 24p3−/− neutrophils failed to phagocytose bacteria, which may explain the enhanced sensitivity of 24p3−/− mice to Listeria monocytogenes, Candida albicans, and Staphylococcus aureus. Importantly, 24p3 does not sequester siderophore produced by Candida and, Listeria does not secrete siderophore. Therefore the observed sensitivity of 24p3−/− mice to these pathogens is not related to the antibacterial function of 24p3 resulting from sequestration of siderophores, but is a consequence of impaired neutrophil function.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines, culture conditions and transfections

NIH 3T3 Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) or 5% horse serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 units of Penicillin, and 100 μg Streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were transfected with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) or X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagent (Roche) as per the manufacturer’s recommended procedure.

Reagents

General laboratory chemicals and cell culture reagents were purchased from either Invitrogen or Sigma. The PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse Ly6G/Ly6C (Gr-1) mAb (clone RB6-8C5), the PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse Ly6G (Gr-1) mAb (clone 1A8), the PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD11b (Mac-1) mAb (clone M1/70), the PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse L-selectin (CD62L) mAb (clone MEL-14), the PE-conjugated rat IgG2 mAb (clone A95-1) isotype control were obtained from BD biosciences. The mAbs anti-mouse CD45.1 (clone A20) and CD45.2 (clone 104), mouse IgG2a isotype control, and the FITC conjugated CD115 (M-CSF receptor antibody; clone AFS98) were obtained from e-bioscience. Antibodies for immunoblotting were from Santa Cruz biotechnology (E2F-1), Thermo Scientific (RacGAP1), and Sigma (GAPDH).

Plasmid constructs

The expression plasmid for mouse miRNA miR362-3p (pCMV-MIR mIR362-3p) and empty miRNA expression vector (pCMV-MIR) were from Origene. The miRNA 3-UTR target expression clone for E2F1 (Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR) was from GeneCopoeia. This is a dual reporter plasmid, which contains both firefly luciferase and Renilla luciferase reporters that are driven by SV40 enhancer and CMV promoters, respectively (http://www.genecopoeia.com/wp-content/uploads/oldpdfs/product/mirna/pEZX-MT01.pdf). The oligomers for mIR362-3p and scramble miRNA were from IDT.

Animals

Mice genetically deficient for 24p3 (24p3−/−) were described previously (26). 24p3−/− mice described in this study were backcrossed onto C57BL/6 or 129SVimJ genetic backgrounds for 9 or 10 generations, respectively. C/EBPε−/− mice were originally derived in the laboratory of Dr. Xanthopoulos (ref. 30). We obtained C/EBPε−/− mice on C57BL/6 background from Dr. Koeffler, UCLA. The CD45.1 wild type mice utilized for adoptive transfer experiments were purchased from NCI (http://ncifrederick.cancer.gov/Programs/Science/App/StrainInformation/01B96.aspx). Age- and sex-matched adult mice on comparable genetic background were used for experiments. Mice were genotyped as described in refs. 26 & 30. Mice were housed in microisolator cages and received food and water ad libitum. All experimental protocols were performed in accordance with IACUC guidelines and were approved by the institutional ARC.

Analysis of peripheral blood smears

A drop of peripheral blood was smeared onto a clean glass slide, and the smear was quickly air dried for 30 min at room temperature. The smears were then stained with Diff-Quick staining kit (Dade-Behring) as per the manufacturer’s recommended protocol. Representative images were shown.

Casein or thioglycollate-induced peritonitis

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of 9% casein (Sigma) or with 1 ml of 4% thioglycollate (Sigma). Six hours later, mice were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation and the blood was drawn from the retro-orbital plexus into heparinized tubes. Neutrophils from the peritoneal exudates were isolated as described in Dong and Wu (ref. 27). Briefly, the peritoneal cells were harvested into 5 ml of PBS + 1% BSA, washed, layered onto a three-step Percoll (Pharmacia) gradient (1.07, 1.06, 1.05 g/ml), and centrifuged at 400 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The neutrophil band was aspirated and the contaminating RBCs were removed by lysing them in ACK lysis buffer (Gentra systems). The cellularity in the peritoneal exudate was enumerated with a hemocytometer. Elicited neutrophils from 5 mice were pooled for further analysis.

Isolation of bone marrow-derived neutrophils

Unelicited bone marrow neutrophils were obtained by flushing femurs of 5 mice each for 24p3+/+ or mutant 24p3 locus and centrifugation through Percoll as described in ref. 27. The percentage of neutrophils in peripheral blood was determined by flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry analysis

Samples were treated with RBC lysis buffer (Gentra systems) to remove contaminating RBC. Single cell suspensions were stained with different fluorescence-labeled Gr-1 (clones RB6-8C5 or 1A8; e-biosciences), CD62L (BD biosciences), Mac-1 (BD biosciences), and F4/80 (Serotec) and matching isotype control antibodies (BD biosciences) were used as controls. Labeled cells were subsequently analyzed on a FACS Calibur cytometer and analyzed using Cellquest and FlowJo software.

Cytokine and Chemokine determination

The levels of cytokines were evaluated using cytometric bead array as per the suggested procedure (http://www.bdbiosciences.com/research/cytometricbeadarray/). The levels of chemokines KC and MIP-2 in peritoneal lavages of induced peritonitis model were determined by ELISA (Ray Biotech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In vitro microbicidal assays

To determine the in vitro bactericidal effect of neutrophils, 5 x 106 cells were mixed with E.coli (ATCC strain 25922; 1 x 106 CFU/ml) or S. aureus (ATCC strain 25923; 1 x 106 CFU/ml) in HBSS, 1 mM HEPES and 10% autologous sera. The bacteria and neutrophil mixture was incubated with agitation at 37°C for 4 hours. Under these experimental conditions, we routinely observed ~75% killing of bacteria. The cells were lysed in sterile water and serial dilutions were made and 50 μls of lysate was plated onto LB agar plate. Following overnight incubation at 37°C, bacterial colonies were counted. The number of bacteria recovered in assays with 24p3+/+ neutrophils was considered 100% and the viable bacteria from assays with 24p3−/− neutrophils were calculated by (100 x number of bacteria recovered in null mice/number of bacteria recovered in 24p3+/+ mice).

Neutrophil chemotaxis

Chemotaxis assays were performed with neutrophils purified from bone marrow isolates as described in ref. 27. Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed from femora of 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice, RBC were lysed, remaining leukocytes were washed with HBSS (Invitrogen), and suspended in HBSS containing 45% Percoll (Amersham). The leukocyte suspension was then layered on to a Percoll gradient (81%, 62%, 55%, and 50%) and spun at 1600g for 30 min. The mature neutrophils banded between 81% and 62% layers were aspirated with a sterile Pasteur pipette, washed twice with HBSS, and their numbers were enumerated in a hemocytometer. Chemotaxis assays were performed using modified Zigmond and Dunn chamber as described (ref. 27). The isolated neutrophils were seeded onto a coverslip and the cells were allowed to settle for 5 min at RT. Later the cover slip was placed inverted on to a Dunn chamber containing concentric chemotactic gradient (5 μM fMLF, Sigma). The cell movement was recorded using a time-lapse video microscope. The speed and the distance traveled by the cells were then determined using Metamorph software. Neutrophil chemotaxis was also assayed in Boyden chamber as described in ref. 27. Chemotaxis index is the ratio of number of migrated neutrophils in the presence of chemoattractant to the number of neutrophils in the absence of chemoattractant.

Depletion of neutrophils

Neutrophil depletion was achieved by using anti-mouse Gr-1 antibody (clone 1A8, which is specific to Ly6-G, Bio X cell) as described in ref. 28. Briefly, mice received an intravenous injection of 100 μg of anti-Gr-1 antibody 24 hours prior to in vivo chemotaxis study. Control mice received equivalent amounts of isotype control antibody in sterile PBS. Depletion of neutrophils was confirmed by staining for circulating neutrophils with anti-Gr-1 antibody. This procedure routinely yielded >95% neutropenia.

Adoptive transfer of bone marrow neutrophils

Isolated bone marrow neutrophils were transplanted into mice that were rendered neutropenic by anti-Gr-1 antibody injection as described above. The success of transplantation was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis of peripheral blood leukocytes with antibodies against CD45.1 or CD45.2 depending on the origin of transplanted cells. The migration of transplanted neutrophils into the peritoneum of recipient mice was determined by flow cytometry analysis of peritoneal fluids of thioglycollate-injected mice (in vivo chemotaxis) with anti Gr-1 antibody.

Quantification of Phagocytosis

For quantitation of phagocytosis, 2 x 105 cells were first stained with phycoerythrin (PE) coupled Gr-1 Ab (BD biosciences) and excess Ab was removed by washing with PBS. Gr-1 stained neutrophils were then incubated with 50 μls of BODIPY FL-E.coli particles (Invitrogen), which were prior opsonized with 12.5% homologous sera. A portion of cells was kept on ice (as controls) and the remaining portion of cells was warmed to 37°C. After 30 min of incubation with gentle agitation, samples kept at 37°C were removed and chilled on ice rapidly to halt the phagocytosis. The cells were then treated with 0.25 mg/ml Trypan blue (Invitrogen) to quench the extracellular fluorescence. Cells were washed with 2 mls of ice-cold PBS and samples were recovered by centrifugation. The samples were washed two more times with PBS for a total of three washes. The recovered cells were subjected to Flow cytometry. Effectiveness of quenching was documented by the absence of fluorescence in negative control cells.

Neutrophil apoptosis

To determine neutrophil apoptosis, elicited neutrophils from 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice were cultured in RPMI (Invitrogen) with or without G-CSF (25 ng/ml, Peprotech) for indicated time periods. Cell death was determined by staining with Annexin-V FITC (BD Biosciences) and subsequent flow cytometry.

Transcriptome analysis

Isolated bone marrow neutrophils from 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice were used for identifying differentially regulated genes. Total RNA was isolated from naïve (untreated) neutrophils from 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice was isolated using RNeasy kit from Qiagen. Contaminating chromosomal DNA was removed by DNase (Qiagen) treatment. To identify genes that are differentially regulated upon fMLF treatment, we treated isolated neutrophils from 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice with 5 mM fMLF for 15 min. Total RNA from treated neutrophils was isolated as described above.

Purified total RNA was used to prepare fragmented and biotin-dUTP labeled cRNA according to Affymetrix target preparation protocols available online at (http://www.affymetrix.com/support/technical/manuals.affx). First, cDNA was synthesized from ~10 mg of total RNA in first-strand buffer containing 25 ng/ml engineered random primers containing T7 sequence (Ambion), 10 mM DTT, 0.5 mM dNTPs (Invitrogen) and 25 U/ml SuperScript RT (Invitrogen). The resulting first-strand cDNA was converted to double-stranded cDNA in a second-strand cDNA synthesis reaction. Ten mls of first-strand reaction was incubated with E.coli DNA polymerase (10 U/ml), E.coli RNaeH (2 U/ml), 10mM dNTPs in second strand buffer (Invitrogen). Labeled antisense cRNA was synthesized from dsDNA using T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion) with biotin-dUTP (Sigma). The biotinylated cRNA was fragmented and subjected to microarray analysis using Affymetrix GeneChip mouse whole transcript arrays (Mouse Gene 1.0 ST array) containing ~26,000 transcripts. Hybridization, washing and scanning of gene chips was performed at Case Comprehensive Cancer Center Microarray core facility (http://www.gegf.net). Specific protocols for Affymetrix hybridization and scanning protocols are available at the Internet address provided above.

Each experiment was repeated in triplicate. The “.CEL” files from the MAS5 software were used as starting points for all analyses. The data were analyzed by using the R statistical package. The Robust Multi-chip Average (RMA) method was used to obtain normalized expression estimates. Differences between samples groups are expressed as log2-ratio. The statistical significance of differential gene expression between 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice was calculated by significance analysis of microarrays (SAM) method as an alternative to Student’s t-test. Microarray data are posted on the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo), accession number series GSE43889.

The leading edge subset of genes was determined by the Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) criteria “core enrichment” as per the guidelines available at (www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/index.jsp).

cDNA synthesis and mRNA detection

Total RNA was isolated from naïve or treated cells using Trizol method (Invitrogen). DNase I (Promega) treated RNA was then reverse transcribed using Superscript III RT from Invitrogen as per manufacturer’s recommendations. The resulting cDNAs were subjected to real time PCR analysis using SYBR Green master mix (Promega) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The fold-change was calculated using ΔΔ CT method.

Expression profiling of miRNAs

Total RNA, including small non-coding RNAs was extracted from bone marrow neutrophils of 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice using the mirVana miRNA isolation kit from Ambion, as per the manufacturer’s protocol. For miRNA analysis, 300ng of total RNA was biotin labeled using the FlashTag HSR RNA labeling kit from Affymetrix miRNA arrays as per manufacturer’s suggestion (http://www.affymetrix.com/estore/browse/products.jsp?productId=131473&categoryId=35574&productName=GeneChip%26%23174%3B-miRNA-Arrays#1_3). Labeled RNA was hybridized to Affymetrix mouse GeneChip miRNA 3.0 array. Hybridization, washing and scanning was performed by the microarray core facility at Case Comprehensive Cancer Center (http://www.gegf.net).

.Cel files were converted to spreadsheets of numbers using miRNA QC tool (Affymetrix). The following QC parameters were consulted to assess the quality of the run: Oligos 2, 23, and 29 are RNA, and are used to confirm poly(A) tailing and ligation. Oligo 31 is poly(A) RNA, and confirms ligation. Oligo 36 is poly(dA) DNA, and confirms ligation and lack of RNAses in the RNA sample. Differential expression was inferred from records satisfying two criteria: Increased gene expression was reported for the treated sample when the signal was >= 1.5 compared to the control sample; and a p value of <=0.05. Genes satisfying these criteria were filtered and exported as excel files. Each experiment was repeated in triplicate. The data is available in GEO under the accession number series GSE43890.

cDNA synthesis and miRNA detection

Total RNA was isolated from naïve neutrophils was isolated using mirVana kit (Ambion). Reverse transcription of miRNA to first-strand cDNA stem-loop primers was performed using miRCURY LNA™ Universal RT microRNA PCR, Polyadenylation and cDNA synthesis kit (Exiqon). The resulting cDNA was subjected to real time PCR analysis using SYBR Green master mix (Promega) with primers specific for miR362-3p (mmu-miR-362-3p, LNA™ PCR primer set, Exiqon) following the manufacturer’s recommendations. The fold-change was calculated using ΔΔ CT method. The expression levels of miR362-3p were normalized by comparing to the expression levels of 5s rRNA (Exiqon).

Luciferase assays

NIH3T3 cells at 50 to 60% confluency cultured in a 6-well plate were transiently cotransfected with the Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR reporter construct, graded doses of miR-362-3p (mCmCmUmCmUmGmGmGmCmCmCmUmUmCmCmUmCmCmAmGmU), or scrambled miRNA (mAmAmAmAmCmCmUmUmUmUmGmAmCmCmGmAmGmCmGmUmGmUmU) oligomers. In a related set of experiments, Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR was also cotransfected with increasing amounts of pCMV-MIR-miR362-3p or pCMV-MIR. Following the removal of DNA complexes cells were recultured in fresh growth medium. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities of lysates were assayed using a Dual Luciferase Assay kit from Promega as per the suggested procedure. All Luciferase measurements were normalized to the Renilla Luciferase expression in order to correct for differences in transfection efficiency.

RhoA activation assay

RhoA activation was assessed using Rho pull down assay kit from Millipore as per the manufacturer’s recommended suggestions. Briefly, clarified cell lysates from naïve or fMLF stimulated bone marrow neutrophils from 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice were incubated with GST-tagged Rhotekin (Rho binding domain) fusion protein immobilized on glutathione coupled agarose beads. The activated Rho (GTP-Rho) but not inactive Rho (GDP-Rho) specifically binds Rhotekin. The activated Rho in fMLF-stimulated cells was pulled down with Rhotekin-Rho-binding domain-agarose beads. The interacting activated RhoA was recovered by pelletizing the beads. The beads were then washed extensively to remove unbound proteins or inactive Rho. The bound active Rho was eluted into the Laemmli sample buffer by boiling the beads. The active Rho was detected by performing Immunoblotting with anti-RhoA antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology).

Rac activation assay

Activation of Rac was measured using GST-PAK pull down assay with a kit from Millipore as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, clarified cell lysates from naïve or fMLF stimulated bone marrow neutrophils from 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice were incubated with the Rac/Cdc42 binding domain of GST-PAK fusion protein immobilized on glutathione coupled agarose beads. The activated Rac (GTP-Rac) but not inactive Rac (GDP-Rac) specifically binds PBD. The activated Rac in fMLF-stimulated cells was pulled down with PAK fusion protein was recovered by pelletizing the beads. The beads were then washed extensively to remove unbound proteins or inactive Rac. The bound active Rho was eluted into the Laemmli sample buffer by boiling the beads. The active Rac was detected by performing Immunoblotting with anti-Rac antibody (Santa Cruz biotechnology).

Actin polymerization assay

Bone marrow neutrophils from 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice were stimulated with 5 μM fMLF for indicated periods of time. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at RT. Cells were then stained with 160 nM FITC-Phalloidin for an additional 30 min at RT. Cells were washed and resuspended in PBS containing 0.05% BSA and analyzed by flowcytometry.

Experimental infection with S. aureus, C.albicans, and L. monocytogenes

S.aureus (strain ATCC 25923) was cultured in trypticase soy broth (TSB), washed three times with PBS then resuspended in PBS for animal injection. Age and sex-matched mice from each genotype were intraperitoneally injected with 1ml PBS containing 3 x 108 S.aureus. The mortality in infected mice was recorded and plotted in Kaplan-Meier analysis. For determination of bacterial loads, infected mice were sacrificed 72 hours post infection and the amount of bacteria was determined in homogenates of liver, spleen, and kidney. Serial dilutions of homogenates were plated on to TSB agar plates. Bacteria colonies were enumerated after incubation for 24 hours at 37°C.

Stock cultures of C.albicans (ATCC 562) were cultured in YM broth (BD biosciences). For experimental inoculation, cultures were propagated overnight in YM broth at 37°C and the blastoconidia were collected by centrifugation, washed with sterile PBS, and suspended in sterile PBS. The number of fungi was determined with a hemocytometer and their viability was determined by plating the diluted samples on YM agar plates. Mice (8 mice per group) were injected intravenously with 5 x 105 cells of C.albicans. All the injected doses were verified by determining the CFU. The mortality in infected mice was recorded and plotted in Kaplan-Meier analysis.

To assess the kinetics of infection, groups of 4 mice challenged with C.albicans were sacrificed at 4, 6, and 12 days post challenge. Organs were then homogenized in 5 ml of PBS and serial dilutions were plated in YM agar plates. Colonies were enumerated following incubation at 37°C for 36 to 48 hours.

L. monocytogenes (strain EGD) was propagated in tryptic soy broth (TSB). For mice listeriosis experiments, a frozen aliquot of L. monocytogenes was thawed, diluted 10-fold into TSB and recovered at 37°C for 1 hr and 30 min. Recovered bacteria were then diluted 200-fold into sterile PBS to obtain 3 – 10 x 104 CFU/ml. Mice were injected intravenously via lateral tail vein with 1 – 3 x 104 CFU. All the injected doses were verified by determining the CFU. To determine the bacterial load in injected mice, spleens and livers of infected mice were harvested 48 hrs post inoculation. Tissues were then homogenized using a Polytron homogenizer and 5 μl aliquots of each homogenate were plated in serial 5-fold dilutions in TSB plates. Colonies were enumerated two days later.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical analysis software package SAS (SAS institute. Cary, NC). Differences between groups were examined by ANOVA and Bonferroni correction for multiple tests, Student’s t-test for equality of means and Mann-Whitney test for non-Gaussian distribution of variables. p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Altered neutrophil homeostasis in 24p3−/− mice

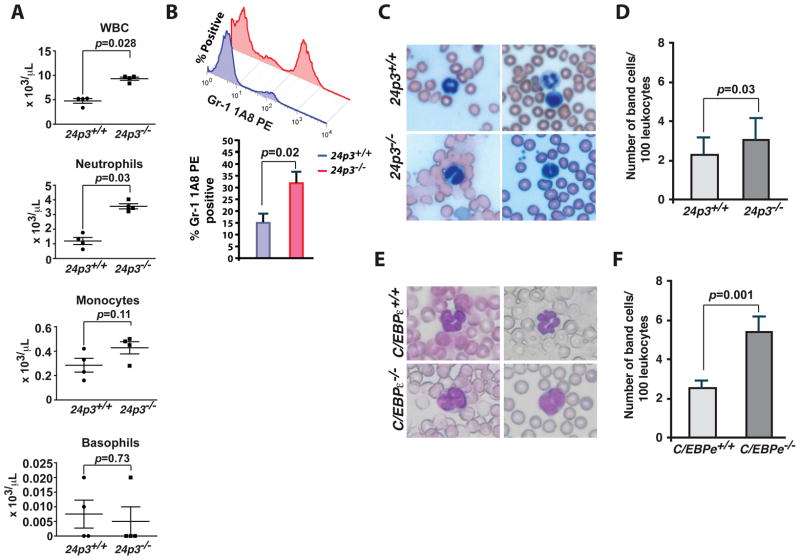

Mutations in C/EBPε, a transcriptional regulator of neutrophil secondary granules, including 24p3, affect neutrophil differentiation (Supplemental Fig. 1 A; refs. 29, 30). Therefore, we determined whether a deficiency of 24p3 alone has consequences for neutrophil development. We evaluated the hematological parameters of peripheral blood of 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice. We observed an increased number of neutrophils in 24p3−/− mice. Additionally we also found that absolute leukocyte counts were also elevated (Fig. 1 A, Table 1; also see ref. 26). In contrast monocytes and basophil counts remain unchanged in 24p3−/− mice (Fig. 1 A and Table 1). The observed increase in leukocyte counts is unrelated to an opportunistic infection; routine disease surveillance did not indicate the presence of adventitious pathogens in the mouse colony (26). Analysis using flow cytometry with an antibody specific for a granulocyte-specific marker (Ly6G, clone 1A8; ref. 28) confirmed an increase in neutrophils in the peripheral blood of 24p3−/− mice (Fig. 1 B and Table 2).

Fig. 1. Granulocyte abnormalities in 24p3−/− mice.

(A) Hematological parameters of peripheral blood from 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice. The data is presented as mean x 103 cells/μl. Error bars depict SD. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of neutrophils in the peripheral blood. Cells were stained with indicated clones of Gr-1 antibody (clone 1A8) and %positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 2 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (C) Wright-Giemsa staining of peripheral blood smears of 24p3−/− mice identified atypical hyposegmented neutrophils in the peripheral blood. In contrast, 24p3+/+ mice displayed normal neutrophil maturation. (D) Enumeration of number of band neutrophils in the peripheral blood of 24p3−/− mice. The data is presented as mean band cell numbers per 100 leukocytes. Error bars depict SD. (E) Wright-Giemsa staining of peripheral blood smears of C/EBPε−/− mice shows augmented band neutrophils in the peripheral blood when compared with C/EBPε+/+ mice. (F) Enumeration of number of atypical hyposegmented neutrophils in the peripheral blood of C/EBPε−/− mice. The data is presented as mean band cell numbers per 100 leukocytes. Error bars depict SD.

Table 1.

Hematological profile of bone marrow and peripheral blood and spleen from 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice.

| Peripheral Blood | 24p3+/+ | 24p3−/− | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells (x103) | 6.75 ± 3.03 | 9.42 ± 0.61 | 0.028 |

| Lymphocytes (x103) | 5.62 ± 2.17 | 6.80 ± 0.73 | 0.05 |

| Neutrophils (x103) | 2.17 ± 1.39 | 3.90 ± 0.81 | 0.025 |

| Eosinophils | 64.00 ± 1.39 | 19.00 ± 0.12 | 0.014 |

| Monocytes | 426.00± 0.36 | 412.00 ± 0.09 | 0.11 |

| Basophils | 8.00 ± 0.08 | 1.80 ± 0.09 | 0.03 |

Numbers represent the mean (± standard deviation) per mouse of 9 mice for peripheral blood analysis. Values are given per ml of blood.

Table 2.

Gr-1+ cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood from 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice.

| 24p3+/+ | 24p3−/− | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bone marrow | |||

| Gr-1+ cells (%) | 28 ± 1 | 60 ± 2 | 0.01 |

| Peripheral Blood | |||

| Gr-1+ cells (%) | 2.8 ± 0.05 | 7.4 ± 0.7 | 0.04 |

Leukocytes were stained with anti-Gr-1 antibody (clone 1A8). Numbers represent the mean (± standard deviation) per mouse of n= 5 mice for bone marrow and peripheral blood analysis. The cell subset composition was expressed as the percentage relative to the total cell population.

Wright-Giemsa staining of peripheral blood smears from 24p3−/− mice revealed the presence of neutrophils with atypical bi-lobed nuclei (band cells), whereas neutrophils of 24p3+/+ mice bore all the characteristics of mature cells including ring-shaped segmented nuclei and pale abundant cytoplasm (Figs. 1 C & D).

C/EBPε deficiency results in neutrophil abnormalities (30). As mentioned above, 24p3 is regulated by C/EBPε (29) and 24p3 deficiency also contributes to neutrophil abnormalities. We next sought to compare the morphology of neutrophils obtained from mice bearing mutations in either of these two genes. In agreement with the previous findings, we noticed a profound developmental delay in neutrophil maturation in C/EBPε null mice (Fig. 1 E). In contrast, the morphological changes were subtle in neutrophils from 24p3 null mice when compared with the morphology of C/EBP−/− neutrophils. (Fig. 1 C). Further, the number of circulating band cells in C/EBP−/− mice is greater than 5% (Fig. 1 F). In addition to 24p3, C/EPBε also regulates the expression of genes encoding both primary and secondary granule proteins (29, 30). Therefore, the combined deficiency of primary as well as secondary granules following the loss of C/EBPε contributes to the blunted neutrophil development. Thus, these results confirm the previous notion that C/EBPε is a regulator of neutrophil development in mice.

Reduced migration of 24p3−/− neutrophils

We next performed a series experiments to determine the functional competence of 24p3−/− neutrophils. First, we examined the ability of neutrophils to migrate and function in response to an inflammatory stimulus. Leukocyte extravasation into the peritoneal cavity was studied in an in vivo model of inflammation induced by intraperitoneal casein challenge in 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice. Extravasated leukocytes from the peritoneal fluid were harvested, separated on Percoll gradients, counted, and characterized by flow cytometry.

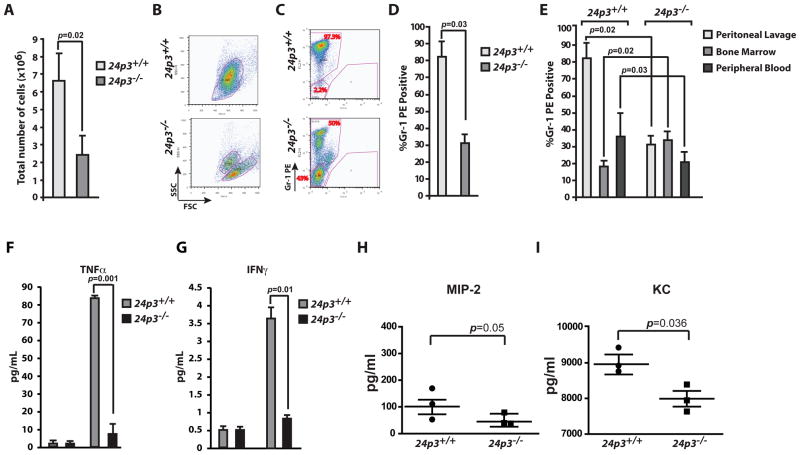

Casein challenge resulted in a robust inflammatory response as demonstrated by the hypercellularity of the peritoneal lavage in 24p3+/+ mice. In contrast, the total number of extravasated neutrophils in casein challenged 24p3−/− mice was ~2-fold lower than that observed in casein challenged 24p3+/+ mice (Fig. 2 A). Giemsa staining of peritoneal exudates demonstrated an approximately 50% reduction in segmented neutrophils in 24p3−/− mice, compared to the segmented neutrophils in the peritoneum of casein injected 24p3+/+ mice (data not shown). Forward and side scatter analyses suggested that by size and granularity the extravasated cells from 24p3+/+ mice are neutrophils and in contrast, the cells recovered from 24p3−/− mice lacked granularity (Fig. 2 B). To assess the composition of cells extravasated into the peritoneum, we performed flow cytometry with an anti Gr-1 antibody. As expected, ~90% of the cells in peritoneal lavage were neutrophils in 24p3+/+ mice, but only ~40% of the cells in 24p3−/− mice expressed Gr-1 (Figs. 2 C & D).

Fig. 2. Reduced emigration of 24p3−/− neutrophils.

(A) Total cellularity of the peritoneal exudates of casein challenged mice. Cellularity was enumerated in a hemocytometer. Error bars depict SD. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of neutrophils in the peritoneal exudates. Forward and Side scatter analysis. (C & D) Peritoneal exudates were stained with Gr-1 antibody and %positive cells were determined by flow cytometry. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 2 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (E) Flow cytometry analysis of bone marrow, peripheral blood and peritoneal exudates of casein challenged mice following staining with a Gr-1 PE antibody. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 2 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (F & G). CBA analysis of inflammatory cytokines in the sera of casein challenged mice. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 2 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (H & I). Quantitative determination of chemokines MIP-2 and KC in the sera of casein challenged mice. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 2 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD.

Normally, the neutrophil containing compartments of the bone marrow, peripheral blood, and extravascular space are in dynamic equilibrium. Under inflammatory conditions neutrophils extravasate from the blood compartment to the sites of inflammation. To compensate for the decrease in their number in the blood compartment, bone marrow neutrophils migrate into the circulation. We analyzed neutrophil kinetics in bone marrow, peripheral blood and peritoneum of casein-injected 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice by flow cytometry following Gr-1 staining. As expected, we observed a drop in neutrophil levels in the bone marrow and peripheral blood compartments and elevated levels in the peritoneum of casein-injected 24p3+/+ mice. In contrast neutrophil levels remain unchanged in the bone marrow and blood compartments in 24p3−/− mice (Fig. 2 E). Thus, the results shown in Fig. 2 suggest that the migration of neutrophils into the peritoneum in 24p3−/− mice is reduced. Interestingly, this is corroborated by a recent study that demonstrated that neutrophils in 24p3 null mice are unable to migrate to the site of injury in a mouse model of spinal cord injury (31). Thus, multiple lines of evidence establish the migratory defect of neutrophils in 24p3 null mice.

Altered chemokine and cytokine responses in 24p3−/− mice

The release of chemokines and cytokines by hematopoietic (macrophages, mast cells, phagocytes) and non-hematopoietic (endothelial, epithelial and others) cells initiates the inflammatory response. Proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, and IFN-γ and chemokines such as IL-8, GRO-1α, and MCP-1 are instrumental in eliciting a neutrophil response. The reduced migration of neutrophils may be due in part to the reduced secretion or absence of any of these chemoattractants. To examine this possibility, we first quantitated levels of proinflammatory cytokines by performing cytometric bead array analysis (CBA; BD Biosciences). Specifically, we assayed the levels of TNF-α and IFN-γ in serum samples of 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice challenged with casein. Data presented in Figs. 2 F and G shows that the levels of these cytokines were elevated in sera from 24p3+/+ mice as predicted. In contrast, the levels of these factors were only slightly elevated in casein-challenged 24p3−/− mice (Figs. 2 F & G). One explanation for the observed reduction in cytokines in 24p3 null mice is that the macrophages, which are the principal producers of cytokines, may need 24p3 to effectively recognize inflammatory stimuli and to mount an effective cytokine response. To directly test this assumption, we isolated peritoneal macrophages from thioglycollate-injected 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice and determined expression levels of mRNAs encoding various cytokines. The mRNA transcripts for TNFα and IFNγ are strongly repressed in 24p3−/− neutrophils compared to 24p3+/+ neutrophils (Supplemental Figs. 1 B and C). In support of our findings, a recent study also reported that 24p3 deficiency adversely affects the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (31).

Chemokines are generated at local inflammatory milieu and play an important role in the local recruitment of neutrophils by promoting their extravasation. Murine chemokines such as KC (CXCL-1) and MIP-2 (CXCL-2) are the major chemoattractants responsible for neutrophil recruitment (32, 33). We therefore evaluated levels of these two chemokines in the peritoneal fluids of thioglycollate-injected mice. We observed a marginal decrease in the expression of MIP-2 in 24p3−/− mice (Fig. 2 H). In contrast, we found that levels of KC are reduced significantly in peritoneal lavages of 24p3−/− mice (Fig. 2 I). The differential expression profiles of these two chemokines in 24p3−/− mice are probably related to mechanisms that govern their synthesis and secretion. Nonetheless, a reduction in KC levels in part can explain the delayed recruitment of neutrophils in 24p3−/− mice in response to inflammation.

L selectin (CD62L), its ligand SLex, and CD18 (Mac-1) are normally expressed on neutrophils, and mediate adhesion to the endothelial cells. Reduced expression of these markers may also account for the defective migration of neutrophils into the peritoneum (34). To test this prediction, we analyzed expression of CD62L and Mac-1 on peritoneal neutrophils derived from casein challenged mice by flow cytometry. We observed a moderate reduction in CD62L expression (~2.5-fold) on neutrophils derived from 24p3−/− mice. These data are consistent with the findings reported in a recent study (35). In contrast, no detectable change in the expression of Mac-1 was observed (Supplemental Fig. 1 D). In combination, a reduction in levels of cytokines and chemokines together with reduced surface expression of CD62L may account for the reduced migration of neutrophils under inflammatory conditions observed in 24p3−/− mice.

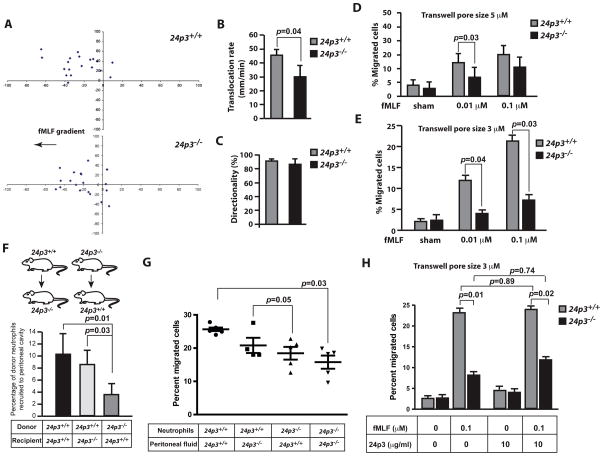

24p3−/− neutrophils are defective for chemotaxis

The results presented in Fig. 2 suggest that neutrophil chemotaxis in vivo in 24p3−/− mice is defective. Therefore, we also tracked neutrophil migration using a Dunn chemotaxis chamber and time-lapse video microscopy. In this assay, we established a stable, shallow chemoattractant gradient and observed neutrophil migration in real time. As expected, bone marrow-derived neutrophils from 24p3+/+ mice sensed and migrated along the chemoattractant gradient (Fig. 3 A and Movie S1). In contrast, fewer 24p3−/− neutrophils sensed and migrated towards the chemoattractant (Fig. 3 A and Movie S2). Quantitative determination of directionality (migration towards the chemoattractant) and rate of migration revealed significant differences between 24p3−/− and 24p3+/+ neutrophils (Figs. 3 B & C). Overall there is a 30% reduction in the translocation rate (distance traveled in 10 min) in 24p3−/− neutrophils (Fig. 3 B). To further confirm these observations, we measured neutrophil migration in a modified Boyden chamber (pore size 5 μM). The percentage of cells that migrated towards the chemoattractant was ~30% lower in 24p3−/− neutrophils compared to 24p3+/+ neutrophils (Fig. 3 D). To further rigorously test this impediment in migration, we tested 24p3−/− neutrophils in a Boyden chamber with a smaller pore size (3 μM). Data presented in Fig. 3 E shows that a vast majority of 24p3−/− neutrophils are retained in the upper chamber. Thus, 24p3 deficiency contributes to reduced migration of neutrophils both in vivo and in vitro.

Fig. 3. 24p3−/− neutrophils are defective for chemotaxis.

(A) Neutrophil chemotaxis was analyzed in a Dunn chamber. Migratory tracks of representative neutrophils are shown. (B) Translocation rates of neutrophils over a period of 10 min. (C) Percentages of cells migrated towards the chemoattractant are shown. (D & E). Chemotaxis of neutrophils was analyzed by the modified Boyden chamber assay. Percentages of cells migrated towards the bottom of the filter were determined. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (F). Bone marrow neutrophils from 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice were adoptively transferred to 24p3−/− or 24p3+/+ recipient mice, which were rendered neutropenic by injection of 100 μg of anti-Gr-1 (clone 1A8) antibody. Migration of transplanted neutrophils into the peritoneum of thioglycollate-injected mice was assessed. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (G). Peritoneal lavages from thioglycollate-injected 24p3−/− or 24p3+/+ mice were analyzed for their chemoattractant ability in a Boyden chamber. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (H). Exogenous supplementation of 24p3 does not correct the chemotaxis defect in 24p3−/− neutrophils. Neutrophils from 24p3−/− were supplemented with 24p3 and their migration was assessed in a Boyden chamber as described above. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD.

24p3 is also secreted by non-hematopoietic cells (8–15, 19, 20). To study the contribution of non-hematopoietic derived 24p3 in neutrophil migration, we adoptively transferred to recipient 24p3−/− mice neutrophils from 24p3+/+ mice (24p3+/+/CD45.2→ 24p3−/−/CD45.1 mice) or to recipient 24p3+/+ mice neutrophils from 24p3−/− mice (24p3−/−/CD45.1 → 24p3+/+/CD45.2 mice; Fig. 3 F). All recipient mice were rendered neutropenic prior to transplantation. Success of transplantation was confirmed by flowcytometry with antibodies specific for CD45.1 or CD45.2 markers (not shown). Adoptively transferred cells were >90% neutrophils (Ly6G+), ~0.5% monocytes (CD115+) and ~9% were negative for both Gr-1 and CD115, which may represent eosinophils, basophils or immature RBCs. Two hours after adoptive transfer, neutrophil migration in to the peritoneum of transplanted mice was studied following stimulation with thioglycollate. As expected, transplanted 24p3+/+ neutrophils migrated efficiently into the peritoneum of 24p3+/+ mice and to a lesser extent in to the peritoneum of 24p3−/− mice (Fig. 3 F). Reduced migration of 24p3+/+ neutrophils into the peritoneum of 24p3−/− mice may be secondary to the reduced levels of chemokines, such as KC, in these mice (also see Fig. 2 I). In contrast, transplanted 24p3−/− neutrophils failed to migrate into the peritoneum of 24p3+/+ mice (Fig. 3 F). Thus, these results suggest that the effects of 24p3 are cell intrinsic.

Chemokines that are important for neutrophil migration are reduced in 24p3−/− mice (Figs. 2 H and I). To further evaluate the chemotactic properties of the peritoneal lavages of 24p3−/− mice, we studied migration of neutrophils in a Boyden chamber using peritoneal fluids of thioglycollate-injected 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice. As expected, 24p3+/+ neutrophils migrated well towards peritoneal fluids of 24p3+/+ mice and less efficiently towards peritoneal fluids from 24p3−/− mice (Fig. 3 G). However, only a few percent of the 24p3−/− neutrophils migrated towards peritoneal fluids of 24p3−/− mice and this deficiency was partially corrected when peritoneal fluids of 24p3+/+ mice were used as a chemotactic stimuli (Fig. 3 G). These observations further confirm the data presented in Fig. 3 F.

Finally, we asked whether ectopic addition of 24p3 confers the ability on 24p3−/− neutrophils to migrate towards the chemoattractant more efficiently. We added purified recombinant 24p3 derived from mammalian cells to 24p3−/− neutrophils and studied their migration in a Boyden chamber as described above. The data presented in Fig. 3 H shows that exogenous supplementation of 24p3 had a marginal effect on the transmigration of 24p3−/− neutrophils. Taken together, these results suggest that for an efficient migration of neutrophils both 24p3 that is intrinsic to neutrophils and 24p3 in the resident cells, which secrete inflammatory mediators is required to mount an effective response to infection/inflammation.

24p3 deficiency does not impair the oxidative burst of neutrophils

Deficiency of lactoferrin also a secondary granule protein, impairs the oxidative burst in neutrophils (ref. 36). We asked whether the absence of 24p3 also adversely affects oxidative burst in neutrophils. We measured oxidative burst in naïve as well as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-stimulated neutrophils obtained from peritoneal exudates of casein-challenged 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice. We found that the oxidative burst in PMA-stimulated neutrophils of 24p3−/− mice was impaired when compared with 24p3+/+ neutrophils as judged by dihydrorhodamine (DHR) oxidation (Supplemental Fig. 1 E). However, some activated cells were present in the cells without PMA treatment. This likely reflects baseline activation of neutrophils that have emigrated into the peritoneal space. Therefore, we repeated the DHR studies with bone marrow neutrophils, which are resting cells. In contrast to the results obtained using peritoneal neutrophils, we did not observe impairment of DHR oxidation in 24p3−/− neutrophils upon agonist stimulation (Supplemental Fig. 1 F). We also measured oxidative burst in neutrophils from 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice using a quantitative assay to complement the results of the DHR assay. We examined agonist-dependent SOD-inhibitable reduction of ferri cytochrome c as a measure of oxidase activation with bone marrow neutrophils and as before, we did not detect any differences in SOD-inhibitable ferri cyt c reduction in agonist-stimulated neutrophils between 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice (Supplemental Fig. 1 G). Finally, analysis of the levels of p47 and p67 PHOX proteins, two major NADPH oxidases in bone marrow neutrophils of 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice did not reveal any major differences as judged by immunoblot analysis (Supplemental Fig. 1 H). Thus, the functional ability of 24p3−/− neutrophils to produce reactive oxygen species is not impaired.

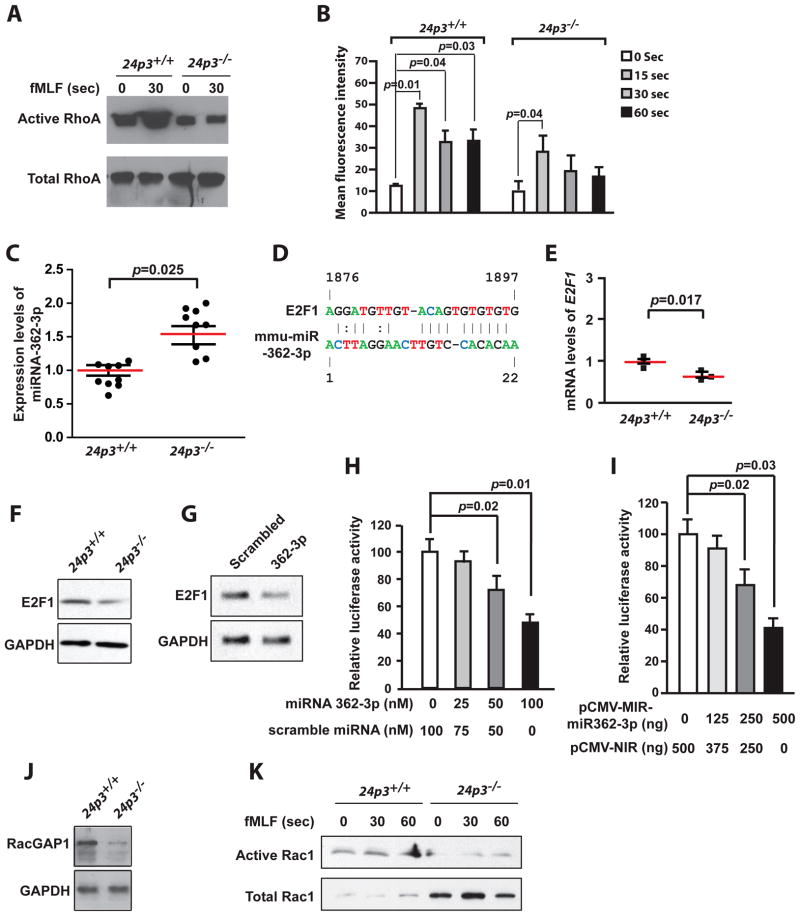

Altered RhoA signaling pathway in 24p3−/− neutrophils

To understand the molecular basis of reduced neutrophil migration both in vivo and in vitro, we compared the global transcriptomes of naïve bone marrow neutrophils or bone marrow neutrophils stimulated with fMLF from 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice using the Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse whole transcript array. The transcriptome of naïve bone marrow neutrophils of 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice is very similar (Fig. 4). However, fMLF stimulation elicited a broader transcriptional response in 24p3+/+ bone marrow neutrophils as compared to 24p3−/− bone marrow neutrophils. Overall, ~600 mRNA transcripts differed significantly in expression between wild type and mutant neutrophils that were stimulated with fMLF (SAM p value, <0.01; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Microarray transcriptome analysis of fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− neutrophils.

(A). The table shows functional categories most significantly enriched in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ neutrophils. 3 gene sets with highest number of genes represent cell motility. (B). Enrichment plot showing upregulation of genes indicative of activated RhoA signaling in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ neutrophils versus fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils. Each vertical line represents a gene within the dataset. Leading edge of the curve indicates significantly upregulated expression of many genes in the RhoA signaling pathway in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ neutrophils compared to fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils. Size = number of genes; NES = normalized enrichment score; p-val = p value; FDR = false discovery rate. (C). Heat map representation of the expression of the top 50 leading edge genes enriched in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ neutrophils compared to fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils. Fold changes are indicated on the right. Regulators of cytoskeletal proteins or genes that encode cytoskeletal proteins are highlighted in red.

We used the computational algorithm Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) to assess whether any of several thousand predefined sets of genes representing biological pathways are differentially expressed in 24p3−/− bone marrow neutrophils. One of the most significantly and consistently enriched gene sets in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ neutrophils comprises components of the RhoA signaling pathway (Fig. 4 A–C). These results are consistent with the notion that RhoA signaling is important for cell motility. The “leading edge” genes, the subset of the RhoA Gene list that account for the enrichment, included transcription factors, inflammatory regulators, and cytoskeletal protein regulators (Fig. 4 A). In contrast, the expression of the leading edge genes derived from the RhoA Gene list was not increased when fMLF was added to 24p3−/− neutrophils (Fig. 4 C). Interestingly, we also found that mDia1 an important regulator of actin nucleation is severely repressed in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils (Fig. 4 C and ref. 37). To independently confirm the differential expression of gene expression, we performed a quantitative real time PCR analysis. In agreement with the microarray data, we found that fMLF stimulation alters gene expression differentially in 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− neutrophils (Supplemental Fig. 2).

To directly test the differential activation of RhoA upon fMLF stimulation, we performed a RhoA pull down assay. This assay utilizes a Rhotekin-GST fusion protein that binds only to the GTP-bound active form of RhoA. Such binding can then be detected using an anti-RhoA antibody. This assay was used successfully to detect basal levels of active RhoA in naïve cells (Fig. 5 A). RhoA activity was particularly high in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ neutrophils but not in 24p3−/− neutrophils (Fig. 5 A).

Fig. 5. Impaired RhoA and Rac1 activation in 24p3−/− neutrophils.

(A). Active RhoA was detected in a pull down assay. Bone marrow neutrophils were stimulated with fMLF followed by affinity precipitation using Rhotekin-GST. Immunoblot of one representative experiment is shown. (B). F-actin staining before and after fMLF stimulation of FITC-Phalloidin stained 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− neutrophils and expressed as mean fluorescence intensity. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (C). fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils express miR-362-3p. Total RNA from naïve or fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− neutrophils was analyzed for miR-362-3p expression by quantitative real time PCR analysis. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 9 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (D) mir-362-3p seed match in the 3′-UTR of E2F1. (E) Analysis of endogenous E2F1 mRNA in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− neutrophils by quantitative real time PCR analysis Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (F) Immunoblot analysis of endogenous E2F1 levels in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− neutrophils. Immunoblot of a representative experiment is shown. (G) NIH3T3 cells were transfected with miR-362-3p or scrambled miRNA oligomers (100 nM each). Immunoblot shows that E2F1 levels were down regulated in cells transfected with miR-362-3p. Immunoblot of a representative experiment is shown. (H) Ectopic expression of miR-362-3p suppresses E2F1 in a reporter assay. Analysis of Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR activity in NIH3T3 cells, which were cotransfected with graded doses of miR362-3p or scrambled miRNA oligomers. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (I) Overexpression of miR-362-3p suppressed E2F1 in a reporter assay. Analysis of Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR reporter activity in NIH3T3 cells, which were cotransfected with miR-362-3p expressing vector (pCMV-miR-362-3p). Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 3 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD. (J) Immunoblot analysis of RacGap1 levels in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− neutrophils. Immunoblot of a representative experiment is shown. (K) Rac activation assay. Active Rac in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− neutrophils was affinity precipitated using PAK-GST. Immunoblot of a representative experiment is shown.

If these results are correct, then interruption of RhoA signaling should result in actin anucleation. To examine this idea, we analyzed actin polymerization in naïve as well as fMLF-stimulated neutrophils from 24p3+/+ and 24p3 null mice. Phalloidin staining revealed that actin levels are equivalent in 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− neutrophils at baseline, but only increase 3-fold in 24p3−/− neutrophils vs almost 5-fold in 24p3+/+ neutrophils 15s after fMLF stimulation and remained low in 24p3−/− neutrophils compared with 24p3+/+ neutrophils (Fig. 5 B).

Taken together, these results suggest that fMLF stimulation initiates transcription of a network of genes in 24p3+/+ neutrophils, which collectively promotes a chemotactic response, and the lack of such transcriptional response accounts for the reduced migration of 24p3−/− neutrophils.

Chemoattractant stimulation induces miR-362-3p

MicroRNAs are 19–25 nucleotide non coding RNAs that can regulate gene expression posttranscriptionally by binding to partially complementary sequences, mainly in the 3′-UTR of their target mRNAs. Deregulated expression of miRNAs affects several effector molecules resulting in alterations in cell proliferation, differentiation and migration. Several reports identified miRNAs in neutrophils, but their roles in neutrophil function are unknown. Since we observed altered mRNA expression profiles in fMLF-stimulated bone marrow neutrophils, we theorized that fMLF stimulation might also affect miRNA expression. For this reason, we decided to examine the miRNA profile in fMLF treated bone marrow neutrophils of 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed for miRNA expression by performing miRNA microarray analysis using an Affymetrix GeneChip miRNA 3.0 array.

The data presented in Supplemental Fig. 3 A shows the 14 most abundant microRNAs in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils. To explore functions for the target genes for these altered microRNAs, we evaluated the frequency of gene ontology (GO) functional classifications using the annotation software DAVID. The target genes populated many major GO functional categories (Supplemental Fig. 3 B). We found that various processes were significantly modulated, including metabolism, signaling, and gene regulation. The importance of these alterations to the biology of neutrophils is unclear, but suggest that mammalian miRNAs are involved in the regulation of target genes with a wide spectrum of biological functions. Nonetheless, we found that miR-362-3p was highly-induced in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils (Supplemental Fig. 3 A).

In agreement with the microarray findings, a quantitative real time PCR analysis confirmed the induction of miR-362-3p in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils (Fig. 5 C). A computational analysis using the TargetScan predicted that miR-362-3p targets several genes that are important for various cellular processes (Supplemental Fig. 3 B). However, amongst all these predicted target genes, the transcription factor E2F1 was experimentally confirmed to be regulated by miR-362-3p (38). The 3′-UTR of E2F1 has a matching sequence to the seed sequence of miR-362-3p (Fig. 5 D). In agreement with this prediction, endogenous E2F1 levels are lower in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils when compared with 24p3+/+ neutrophils (Figs. 5 E and F). To examine whether E2F1 is a target for miR-362-3p, we transiently overexpressed miR-362-3p in NIH3T3 cells. NIH3T3 cells were transiently transfected with either miR-362-3p or a scrambled miRNA. Protein was isolated 48 hrs post transfection and analyzed. We found a 5-fold reduction of E2F1 in miR-362-3p overexpressing cells compared with scrambled miRNA transfected cells (Fig. 5 G). To further elucidate effect of miR-362-3p on E2F1, we utilized a luciferase-E2F1 3′-UTR (Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR) reporter plasmid. We cotransfected NIH3T3 cells with the Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR reporter construct along with graded doses of miR-362-3p or scrambled miRNA. Transfection of scrambled miRNA has no effect on luciferase activity. In contrast, transfection of miR-362-3p suppressed luciferase activity (Fig. 5 H). In a complementary set of experiments, we cotransfected NIH3T3 cells with the Luc-E2F1 3′-UTR reporter construct along with incremental doses of miR-362-3p expressing plasmid (pCMV-MIR-miR362-3p) and, as a control, an empty expression plasmid (pCMV-MIR). In agreement with the data presented in Fig. 5 H, overexpression of miR-362-3p reduced luciferase activity (Fig. 5 I). These results show that miR-362-3p regulates E2F1.

E2F1 is an important regulator of many cellular functions including cell motility and extracellular matrix remodeling through its control of the expression of downstream target genes (39). One of the downstream target genes of E2F1 that is relevant to neutrophil chemotaxis is RacGAP1 (40). RacGAP1 is a strong stimulator of Rac1 activity (41). Based on this, we surmised that miR-362-3p regulates RacGAP1 via E2F1. Several lines of evidence support this hypothesis: 1) RacGAP1 mRNA levels are lower in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils as indicated by the microarray analysis (Fig. 4 C); 2) immunoblot analysis with anti-RacGAP1 antibody further confirmed these results (Fig. 5 J); 3) we tested Rac1 activity in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils (Fig. 5 K). This assay, based on a similar RhoA activation assay, utilizes a PAK-GST fusion protein that binds only to the GTP-bound active form of Rac1. Such binding can then be detected by using anti-Rac1 antibody. This assay was used successfully to detect basal levels of active Rac1 in naïve cells (Fig. 5 K). Rac1 activity was particularly high in fMLF-stimulated 24p3+/+ neutrophils but not in 24p3−/− neutrophils (Fig. 5 K).

Together these results suggest that the upregulation of a miRNA and downregulation of a set of genes that collectively control actin nucleation causes the reduced neutrophil chemotaxis observed in 24p3−/− mice.

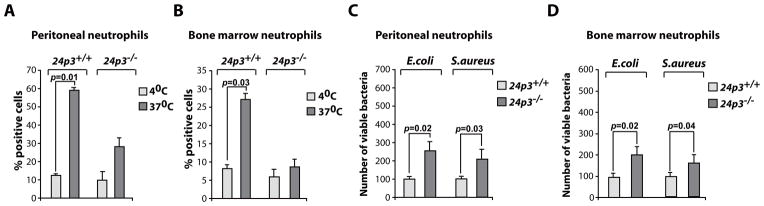

Phagocytosis is reduced in 24p3−/− neutrophils

We next evaluated phagocytosis in 24p3−/− neutrophils. Phagocytosis by peritoneal or bone marrow neutrophils was compared by quantifying the ingestion of fluorescently labeled E.coli by flow cytometry. The data presented in Figs. 6 A & B show that fewer 24p3−/− neutrophils ingested bacteria. Additionally, 24p3−/− neutrophils ingest far fewer bacteria per cell than their 24p3+/+ counterparts (Supplemental Fig. 3 C).

Fig. 6. 24p3−/− neutrophils failed to phagocytose bacteria.

(A) Neutrophils from peritoneal exudates of casein challenged mice were incubated with fluorescently labeled E.coli were analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Phagocytosis by bone marrow derived neutrophils using fluorescently labeled E.coli. (C) In vitro bactericidal assay. Neutrophils from peritoneal exudates of casein challenged mice were incubated with E.coli or S.aureus and the number of viable bacteria were determined. (D) Assessment of bactericidal activity of bone marrow derived neutrophils. Values are average means of triplicate experiments with 4–8 mice per genotype per experiment. Error bars depict SD.

In in vitro experiments, both elicited peritoneal neutrophils and bone marrow neutrophils derived from 24p3−/− mice were deficient in killing of E.coli and S.aureus. A significant number of these bacteria were recovered even after 3 hours of incubation with neutrophils (Figs. 6 C & D). In summary, both phagocytosis and microbicidal functions of neutrophils are impaired in 24p3−/− mice.

Delayed apoptosis in 24p3−/− neutrophils

Neutrophils are abundant, short-lived leukocytes and their death by apoptosis is central to the resolution of inflammation. To optimize the neutrophil’s bactericidal function, their lifespan can be extended by a range of inflammatory mediators including cytokines, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). G-CSF is a lineage-specific hematopoietic cytokine that modifies the functional, biochemical, and survival characteristics of mature neutrophils (42).

To test the hypothesis that a delay in apoptosis contributes to the increased number of neutrophils, we evaluated apoptosis of neutrophils from 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice following the loss of G-CSF signaling at multiple time points. Neutrophil survival was not significantly accelerated upon G-CSF deprivation in 24p3−/− cells, however, under similar experimental conditions, 24p3+/+ neutrophils readily underwent apoptosis (Supplemental Fig. 3 D). Thus, 24p3 is required for neutrophil apoptosis.

24p3−/− mice develop neutrophilia in late age

Given the potential of 24p3 to regulate apoptosis of neutrophils and to determine whether 24p3−/− mice have an abnormal incidence or an altered pathological spectrum of neutrophil number over their life span, we compared the hematological profile of 24p3−/− mice with control mice at different ages. We did not observe any difference in the kinetics of mortality in 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice over 18 months. The surviving mice were sacrificed 18 months after birth and their blood was collected and analyzed for its cellularity and cell subset composition. Neutrophilia was most pronounced in aged 24p3−/− mice and the number of circulating neutrophils was ~4-fold higher in these mice when compared to 24p3+/+ mice. In addition, the majority of circulating neutrophils in 24p3−/− mice were band cells, whereas segmented cells were predominant in the peripheral blood of 24p3+/+ mice (Supplemental Figs. 4 A & B). These results further suggest that 24p3 regulates homeostasis of the myeloid compartment. Other leukocyte sub-types were largely unchanged in 24p3−/− mice.

24p3−/− mice are sensitive to Listeria monocytogenes infection

The observations listed above indicate that 24p3−/− granulocytes are unable to mature and function as normal neutrophils. Since neutrophils provide the first line of defense against invading pathogens, we theorized that 24p3−/− mice would be susceptible to various pathogens. We evaluated the response to various infections using Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria, as well as yeast, in both control and 24p3−/− mice.

Listeria monocytogenes (L.monocytogenes) is an enteroinvasive, facultative, intracellular, Gram+ve coco bacillus. Because of the similarity of L.monocytogenes pathogenesis in humans and rodents, the murine model of systemic L.monocytogenes infection has been widely accepted as an excellent experimental system (43–46). One of the initial mechanisms of resistance to L.monocytogenes is phagocytosis and breakdown of most bacteria by resident macrophages such as Kupffer cells in the liver (43). This is followed by rapid recruitment of neutrophils, within 24 hours, to the sites of infection (43–46). The presence of neutrophils is critical during the early stages, first 48 hours, of infection (43–46). Mice rendered neutrophil-deficient by injection of an anti-neutrophil antibody or mice that are unable to mobilize neutrophils to the site of infection exhibit a marked increase in the replication of L.monocytogenes and enhanced mortality (45). Thus, these studies highlight the importance of neutrophils in providing defense against invading L.monocytogenes.

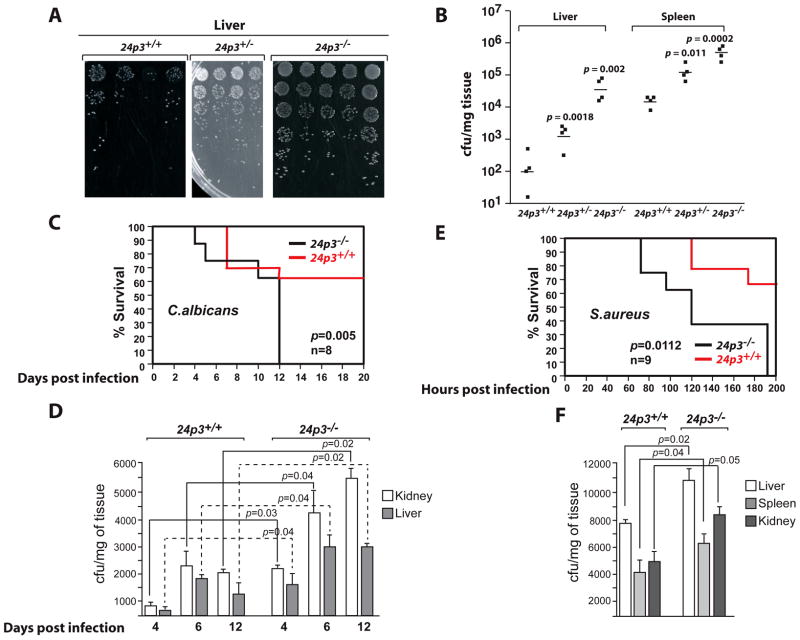

As presented above, 24p3−/− neutrophils fail to mature and are unable to perform some normal neutrophil functions. To evaluate the contribution of 24p3 in host defense against L.monocytogenes infection, we studied listeriosis in 24p3−/− mice. Age and sex-matched 24p3+/+ or 24p3+/− or 24p3−/− mice were injected intravenously with a sublethal dose (1 – 3 x 104 CFU) of Listeria. In mice, the majority of the bacteria are recovered in the liver, where they attach to non-parenchymal cells including Kupffer cells. Two days post-infection, the mice were sacrificed, and livers and spleens were collected. Single-cell suspensions from these organs were then plated in serial dilutions on tryptic soy agar plates, and the number of colonies was enumerated one day later. The bacteria recovered from 24p3−/− mice were ~300 fold higher in liver and ~70 fold higher in spleen when compared with the titer in 24p3+/+ mice (Figs. 7 A & B). Increased susceptibility of 24p3−/− mice to L.monocytogenes infection was not due to a deficiency in the total number of neutrophils, because, as indicated above, neutrophil number is elevated in these mice (Fig. 1, Tables 1 and 2; also see ref. 26).

Fig. 7. Enhanced sensitivity of 24p3−/− mice to Listeria, Candida, and S.aureus.

(A) Mice were injected intravenously with indicated dose of Listeria monocytogenes. Growth characteristics of Listeria recovered from livers and spleens of infected mice. (B) CFU determination in livers and spleens of Listeria infected mice. Bacterial load was determined per mg of tissue 48 hours post infection. (C) Systemic infection with C.albicans (strain ATCC 562) in 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice. Mice were injected with 5 x 105 CFU of C.albicans intravenously and viability was monitored at regular intervals. Values are average means of 8 mice per genotype per experiment. (D). Course of Candida infection in livers and kidneys of 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice challenged with 5 x 105 CFU of C.albicans. Depicted data correspond to mean CFU± SD obtained from livers and kidneys of 3 mice per time point. (E). Survival curve comparing 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice after i.p. challenge with S.aureus 25923 strain (3 x 108 CFU). Values are average means of 9 mice per genotype per experiment. (F). Bacteria loads in livers, spleens, and kidneys of 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice 72 hours after i.p. infection with 3 x 108 CFU of S.aureus. Bars represent mean± SD of five mice per group.

24p3−/− mice are sensitive to systemic infection with Candida albicans

To study the general susceptibility of 24p3−/− mice to pathogens, we challenged 24p3+/+ or 24p3−/− mice with 5 x 105 CFU of Candida albicans (C.albicans) intravenously and the survival of the mice was monitored over 2 weeks. All the mice survived until 3 days post-infection. However, 24p3−/− mice succumbed to the infection on the 4th day post-infection, whereas the onset of mortality was delayed until the 7th day post-infection in 24p3+/+ mice. At day 12, the mortality was 100% in 24p3−/− mice compared to 35% mortality in injected 24p3+/+ mice (Fig. 7 C). The differences in time of death correlated well with the C.albicans load in kidneys and livers of challenged mice (Fig. 7 D). 24p3−/− mice exhibited significantly higher Candida loads in their livers and kidneys 4, 6, and 12 days post challenge than 24p3+/+ mice (Fig. 7 D). No significant difference in the appearance of internal organs was observed in these mice (data not shown).

24p3 deficiency confers sensitivity to Staphylococcus aureus infection

Iron sequestration by 24p3 has no effect on the replication of S.aureus and its pathogenesis in mouse models (22). To determine whether 24p3−/− mice have enhanced susceptibility to S.aureus, 24p3+/+ and 24p3−/− mice were intraperitoneally challenged with 3 x 108 CFU of S.aureus. More than 70% of S.aureus-inoculated 24p3+/+ mice survived, whereas none of the 24p3−/− mice recovered (Fig. 7 E). Further, bacterial loads in livers, spleens, and kidneys of 24p3−/− are significantly higher when compared with 24p3+/+ mice (Fig. 7 F). These results suggest that neutrophils are required to promote an effective protective response against S.aureus infection in 24p3−/− mice.

Thus, modeling of multiple bacterial infections in 24p3−/− mice indicated that 24p3 is important for neutrophil function and its deficiency adversely affects host innate immune defense.

Discussion

We recently derived 24p3−/− mice to determine the essential physiological roles of 24p3 (26). We found that 24p3−/− mice exhibited altered hematopoiesis and developed neutrophilia. 24p3 is a secondary granule protein in neutrophils and plays an important role in innate immunity by restricting iron availability to invading bacteria (7, 22, 24). Gene targeting studies have demonstrated that the absence of primary or secondary granules contributes to neutrophil abnormalities (36, 47, 48). In addition, specific granule deficiency (SGD), a congenital disorder arising from genetic alteration in CCAAT enhancer-binding protein epsilon (C/EBPε) a transcription factor that controls the expression of secondary granule proteins (SGPs) results in disruption of neutrophil maturation and abnormal neutrophil function (49). Interestingly, neutrophils derived from Lactoferrin (LF) deficient mice, a secondary granule protein, are defective for the stimulus-dependent oxidative burst. It was therefore proposed that the absence of LF contributes to the phenotype of SGD patients (36). We hypothesize that deficiency of 24p3 also contributes to neutrophil dysfunction in SGD patients. In support of this prediction, we found that 24p3−/− mice produce abnormal neutrophils (26). We therefore propose that the lack of 24p3 itself contributes to neutrophil dysfunction. We found that 24p3-deficient neutrophils fail to mature normally, are defective for chemotaxis and are unable to phagocytose and kill bacteria. Most importantly, 24p3−/− neutrophils are unable to mount an effective response to promote chemoattractant-induced motility. Finally, 24p3−/− mice displayed enhanced sensitivity to bacterial and yeast infections. In summary, 24p3-deficient neutrophils lack many functions of normal neutrophils.

Unexpectedly, we found that maturation of neutrophils is deficient in 24p3−/− mice. It is unclear how 24p3 deficiency contributes to abnormal neutrophil development, but based on our observations, we propose that its expression is required for normal neutrophil maturation. The granules of neutrophils are expressed at a specific point in neutrophil development. Inappropriate or premature expression of granules sorts them into wrong compartments. Therefore it is entirely possible that absence of certain granule components might adversely affect the sorting of the other granules, which may contribute to a developmental delay. C/EBPε binding sites in the 24p3 promoter play an important role in the expression of 24p3 (29). We also found that expression levels of 24p3 were severely reduced in C/EBPε null mice (Supplemental Fig. 1 A). SGPs are the targets for the C/EBPε and accordingly, mice lacking C/EBPε lack neutrophil SGPs. Additionally, these neutrophils have bi-lobed nuclei, exhibit a much-reduced oxidative burst and are impaired in chemotaxis (30). Thus, C/EBPε is a regulator of myeloid development (49). It is therefore reasonable to suggest that the lack of 24p3 contributes to the neutrophil phenotype of SGD patients.

Chemoattractant driven neutrophil extravasation to the sites of infection and inflammation is a well-coordinated and orderly process. Chemoattractants signal through pertussis toxin-sensitive G protein-coupled receptors. Upon binding to their cognate receptors, GTPase activation is induced resulting in release of G proteins culminating in activation of a variety of kinases including Rho GTPases, tyrosine kinases, and PI3 kinase (50). The collective effect of some of these signaling pathways is to link chemoattractant signaling to cytoskeletal alterations, which result in chemotaxis. These alterations result in the establishment of front-rear asymmetry, with generation of lamellipodial protrusion at the leading edge, establishment of a new adhesion site at the leading edge, cell body contraction, and concomitant trailing edge detachment. These changes are highly dependent on actin assembly and disassembly or reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (50).

This cytoskeletal reorganization in a motile cell is controlled by a variety of intracellular signaling molecules, including the MAPK cascade, phosphatases, lipid kinases, and scaffold proteins. However, one family of proteins, the Rho GTPases, is a key regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics and cell polarity. Although this family contains 22 members, only 3 of them are important for neutrophil motility, Rho (Rho A, RhoB, RhoC), Rac (Rac1 and Rac2) and Cdc42 (50). In general, Rac1 is crucial for membrane protrusion at the front of the cell through stimulation of actin polymerization and integrin adhesion complex. RhoA promotes myosin cytoskeletal organization in the cell body and at the rear. Cdc42 is essential in organizing cell polarity, although it is not required for cell motility per se. The interplay between the Rho family members, as well as interaction of Rho family members with other signaling effectors, creates both positive and negative feedback loops to control cytoskeletal dynamics, which are integral to chemotaxis. Although the importance of the Rho family in actin remodeling has been demonstrated unequivocally, such reorganization requires the activities of cytoskeletal regulatory proteins, which are downstream of Rho family enzymes, but upstream of cytoskeletal proteins. The identity of these intermediate proteins was not known until recently. Nonetheless, mDIA1, a member of the formins, is one such mediator, which connects Rho signaling to actin nucleation (37).

Intriguingly, 24p3−/− neutrophils are defective in chemotaxis. Global expression profiling of 24p3+/+ neutrophils using GSEA analysis suggests coordinated activation of genes with engagement of programs that favor neutrophil motility. RhoA signaling in neutrophil motility is a complex process (50). The Rho family consists of at least 22 members, of which Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA are critical for neutrophil motility. We found that these genes are not activated in 24p3−/− neutrophils following fMLF stimulation. How the absence of 24p3 contributes to the selective down regulation of these genes is a mystery? Nonetheless, it was shown that addition of 24p3 to cells results in differential gene expression (51). Thus, it is entirely conceivable that the absence of 24p3 also leads to an altered transcriptional profile.

Based on expression profiling experiments we propose the following model, in which, if RhoA is not active, activation of genes that culminate in actin nucleation is suppressed. In addition, differential activation of miR-362-3p could also account for a defect in chemotaxis. E2F1, a transcription factor that controls cell motility and extracellular matrix remodeling via modulation of downstream target genes (39), is targeted by miR-362-3p, which is activated in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils. RacGAP1, a regulator of Rac1 is in turn regulated by E2F1 (40), thus silencing of E2F1 by miR-362-3p in fMLF-stimulated 24p3−/− neutrophils results in inactivation of Rac1, which is critical for actin assembly at the front end (50). Thus, activation of miR-362-3p and downregulation of a host of genes that regulate cytoskeletal proteins provides an explanation for the observed defect in chemotaxis in 24p3−/− neutrophils.

Non-hematopoietic cell-derived 24p3 also plays a role in neutrophil infiltration by promoting the release of inflammatory mediators. Two line of evidence support this prediction: First, levels of inflammatory mediators are lower in 24p3−/− mice when compared with 24p3+/+ mice; Second, adoptively transferred 24p3−/− neutrophils were able to migrate efficiently in recipient mice. Additionally, the effects of 24p3 on neutrophil functions are cell intrinsic because exogenous supplementation of 24p3 does not confer the ability on neutrophils to migrate towards the chemoattractant.

Since 24p3 is a proapoptotic protein, we determined whether the neutrophilia observed in 24p3−/− mice reflects their enhanced survival. We found that a significant number of cultured 24p3−/− neutrophils fail to undergo cell death following the removal of G-CSF. Thus, neutrophilia in 24p3−/− mice can be attributed to a defect in granulocyte apoptosis. Abnormal apoptosis of neutrophils has also been demonstrated to contribute to neutrophilia in mice lacking Mac-1 or CD18 (52).