Abstract

Background

Depression is a major cause of chronic ill-health and is managed in primary care. Indicators on depression severity assessment were introduced into the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in 2006 and 2009. QOF is a pay-for-performance scheme and indicators should have evidence to support their use; potential unintended consequences should also have been considered.

Aim

To review the effectiveness of routine assessment of depression severity using structured tools in primary care, and to determine the views of GPs and patients regarding their use.

Design

Systematic review.

Method

Studies were identified by searching electronic databases; study selection, data abstraction, and quality assessment were carried out by one reviewer, with checks from other authors and GRADE (grading of recommendations, assessment, development and evaluation) tables completed for included effectiveness studies.

Results

Eight studies met the eligibility criteria. There was very low-quality evidence that assessing severity in a structured way at diagnosis using a validated tool led to interventions that were appropriate to the severity of depression. Patients and GPs had different perceptions of the assessment of depression at diagnosis, with patients being more positive. GPs highlighted unintended consequences. There was low-quality evidence that structured assessment at follow-up led to increased rates of remission and response, but changes to management were not seen. Patients used this assessment to measure their own response to treatment.

Conclusion

Any estimate of the effect of structured assessment of depression severity in UK general practice is uncertain. GPs consider routine use of questionnaires as incentivised by the QOF has unintended consequences, which could adversely affect patient care.

Keywords: depression; health care; incentive; performance measures; primary health care; quality assurance, reimbursement, Severity of Illness Index

INTRODUCTION

The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) for the UK was introduced in April 2004 and is a pay-for-performance scheme: it provides financial incentives to implement interventions across a range of clinical and health-improvement indicators.1 Pay-for-performance schemes are now widely used in different healthcare systems and there is evidence that they can improve health outcomes for patients.2 However, it is important that indicators have an evidence base to support their use and that any potential unintended consequences are identified and rectified, otherwise they may have adverse effects on care.3

Depression is a major cause of chronic ill-health and is largely managed in primary care.4,5 Two indicators in the depression domain of the QOF are related to depression severity assessment: one at diagnosis and one at follow-up. These were introduced into the QOF in April 2006 and 2009 respectively, using an expert panel process.6

The indicators are:

DEP4: in those patients with a new diagnosis of depression, recorded between the preceding 1 April to 31 March, the percentage of patients who have had an assessment of severity at the time of diagnosis, using an assessment tool validated for use in primary care;

DEP5: in those patients with a new diagnosis of depression and assessment of severity recorded between the preceding 1 April to 31 March, the percentage of patients who have had a further assessment of severity 4–12 weeks (inclusive) after the initial recording of the assessment of severity. Both assessments should be completed using an assessment tool validated for use in primary care.

Their rationale for inclusion is national guideline recommendations to assess severity in patients with depression, to determine appropriate interventions and improve the quality of care.4,5,7 Severity assessment as close as possible to diagnosis (DEP4) enables a discussion with the patient about relevant treatment options. Further assessment (DEP5) enables continued monitoring and determination of the treatment response. Its rationale is that depression is often a chronic disease, yet treatment is often episodic and short lived.7 The assessment tools recommended are any of three severity measures validated for use in primary care: the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the Beck Depression Inventory, second edition (BDI-II), and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Depression subscale (HADS-D). The underlying principle of all suggested measures is that a higher score indicates greater severity, requiring different types of intervention.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has managed the development of QOF indicators from April 2009. The process has a number of significant changes that should lead to the QOF acting as a vehicle for quality improvement, and delivery of more rigorously developed indicators. Key changes include a more explicit guideline recommendation-driven indicator-development process; the consideration of cost effectiveness and clinical effectiveness; and piloting of indicators in a representative sample of UK general practices prior to any recommendation for use.8 There is also an expectation that the QOF will continue to develop,9 and that existing indicators will be retired and new indicators introduced when certain criteria are met; these include retirement based on changes to evidence that suggest an indicator is likely to be ineffective.10

How this fits in

Since 2004, the UK’s Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) has incentivised the assessment of severity of depression in primary care. However, it is not known whether the QOF indicators are effective in improving outcomes for patients and whether they have unintended consequences. This systematic review shows that it is very uncertain whether using the QOF indicators for depression leads to improved health outcomes for patients. It also shows that GPs consider there are associated unintended consequences that could adversely affect patient care.

Since NICE has managed the QOF programme, it has received stakeholder suggestions that the QOF depression indicator set should be reviewed, owing to concerns that there is limited evidence these indicators lead to improved health outcomes, and the use of these indicators may have unintended consequences.11 NICE’s independent QOF Indicator Advisory Committee therefore recommended that a review of the evidence was undertaken for the QOF depression severity indicators.

This study systematically reviewed the evidence for the effectiveness of assessing depression severity using structured tools in UK primary care, and unintended consequences of the use of two QOF depression severity indicators as reported by GPs and patients.

METHOD

Four review questions were formulated:

Does structured assessment of severity at diagnosis improve depression-related outcomes, or processes of care?

What is the experience of GPs and patients assessing the severity of depression at diagnosis as incentivised by the QOF indicator, with specific reference to unintended consequences?

Does structured assessment of severity after diagnosis improve depression-related outcomes or processes of care?

What is the experience of GPs and patients assessing the severity of depression after diagnosis, as incentivised by the QOF indicator, with specific reference to unintended consequences?

Review protocols were developed and reviewed by a panel consisting of GP academic advisers. Details are provided in the Appendix (available from the authors).

Studies were included if they were primary studies of the effectiveness of assessing depression severity, either at diagnosis or at follow-up in a primary care population, or reported the views or experience of GPs or patients. For studies of effectiveness, the review aimed to include randomised controlled studies only; however, owing to the lack of such studies, observational studies were included where relevant. For studies of GP and patient views, qualitative studies or surveys were included. Because of concerns about applicability, studies reporting the views of GPs or patients were restricted to UK primary care only. Studies published in abstract only, or written in languages other than English were excluded.

MEDLINE®, Embase, PsycINFO, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Central Database of Controlled Trials, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) databases were searched from inception to June 2012. See Appendix (available from the authors) for details of the search strategies. Grey literature sources were also searched for any relevant audits.

Studies were assessed for inclusion by a single reviewer and the final list of included studies was checked by GP experts and academic advisers. No relevant, additional studies were suggested. See Appendix (available from the authors) for a full list of excluded studies. Data were extracted from included studies by a single reviewer, and checked for accuracy by another reviewer. Risk of bias was assessed using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology (www.gradeworkinggroup.org),12 a system for appraising and summarising the quality and strength of recommendations. In this system, the following features are assessed for evidence found for each relevant outcome:

study design (as proxy for bias);

limitations in the methodological quality of the study;

consistency of an effect across studies (defined as inconsistent when heterogeneity of results exists, but no plausible explanation is identified); and

directness (the degree to which the results directly address the question posed).

Quality of evidence reflects the extent to which confidence in an estimate of the effect is adequate to support a particular recommendation.

The use of GRADE is consistent with the methods used by NICE in developing recommendations on the effectiveness of interventions in its clinical guideline programme.13 Owing to the nature of the data and outcomes, meta-analysis and statistical assessments of inconsistency and publication bias were not possible; results and judgements are therefore reported qualitatively. See Appendix (available from the corresponding author) for full GRADE tables.

A narrative review of the qualitative evidence is reported; GRADE is not currently formally developed for such use.

RESULTS

Evidence review

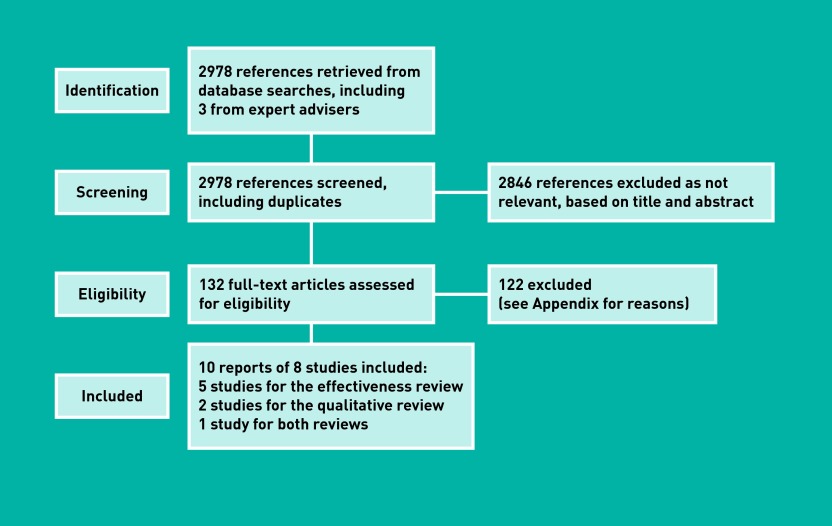

A total of 2978 references, including duplicates, were identified through systematic searching and asking expert advisers. Full text was ordered for 132 articles, based on their title and abstract. Searches for published audits found no new relevant references (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the process.

Eight studies, reported in 10 publications (Figure 1), met the eligibility criteria (for the full review protocol and inclusion/exclusion criteria, see Appendix, available from the corresponding author).14–23

Studies related to the assessment of severity at diagnosis are detailed in Tables 1 and 2 and studies related to the assessment of severity at follow-up are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 1.

Summary of included studies for DEP4 assessment — effectiveness of assessment of severity

| Study reference | Study type | Aim of study | Number of participants | Characteristics of participants | Intervention | Comparator |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kendrick et al, 200516 | Observational study (prospective) | To explore associations between GP treatment and severity of depression, patients’ life difficulties, previous history of illness and treatment, and patient attitudes | 694 patients screened, with 101 patients being rated as depressed; 20 GPs (4 of whom took part in both phases) | Patients were approached for participation if aged >18 years, not currently taking antidepressant or receiving psychiatric treatment, able to complete the screening questionnaire, and not terminally ill | Severity of depression was assessed by the GP (using a rating scale) | Severity of depression was assessed using the HADS (self-assessment) |

| Kendrick et al, 200917 | Observational study (retrospective analysis of medical record data) | To determine if GP rates of antidepressant drug prescribing and referrals to specialist services for depression vary in line with patients’ scores on depression severity questionnaires | Records of 2294 patients assessed for severity of depression (from 38 practices in 3 localities) | Patients with a record of depression severity assessment (from medical records) | n/r | n/r |

| Smith et al, 201022 | Observational study (prospective) | To describe the service use and clinical outcomes associated with the implementation of a complex intervention designed to improve care for people with depression in a primary care setting | 1584 patients referred, with 1169 meeting the inclusion criteria and attending at least once | Referred if new presentation of low mood, depression, or adjustment disorder; adults aged 18–64 years; new presentation defined as no presentation for affective disorder in the previous 6 months, or had begun treatment for new episode in previous 2 months; excluded if primary diagnosis of alcohol dependence, psychosis, bipolar affective disorder, dementia, or terminal illness | The programme incorporated a number of changes, including the following: no ‘severity threshold’ for referral to secondary care (assessment used PHQ-9); routine use of an objective measure of depression severity without continuous outcome monitoring; prompt access to guided self-help; prompt ‘step-up’ care to more formal psychological therapy or medical care, if indicated; and careful attention to staff training and satisfaction; led by a small team of clinicians | No comparator |

HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire. n/r = not recorded.

Table 2.

Summary of included studies for DEP4 experience

| Study reference | Study type | Aim of study | Number of participants | Characteristics of participants | Method of analysis | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dowrick et al, 200915 | Semi- structured qualitative interviews with GPs and patients | To gain understanding of GP and patient opinions of the routine introduction of standardised measures of severity of depression through the UK GP QOF | 34 GPs; 24 patients (from 38 practices in 3 localities) | Purposive sampling used for a maximum-variation approach; for GPs, variation was by sex, years of experience, full-time/part-time practice, trainer-non-trainer, location, and size of practice; for patients, variation was by sex, age, self-defined ethnicity, and sociodemographic group | Constant comparative analysis, using open, axial, and selective coding. | Interviews used broad prompts, including for views on intended and unintended consequences of the introduction of a severity indicator; GPs were asked to provide examples; patients were asked to describe how they felt, and their understanding and views on the impact of assessment |

| Leydon et al, 201118 | As for Dowrick et al, 200914 | To gain understanding of GPs’ opinions and perceived impact on practice of the routine introduction of standardised questionnaire measures of severity of depression through the UK general practice contract QOF | 34 GPs | As for Dowrick et al, 200914 | As for Dowrick et al, 200914 | Interviews used broad prompts, asking GPs about their experience of using the severity indicators in practice, and their views on their use |

| Mitchell et al, 201120 | Focus groups of healthcare professionals from four general practices | To explore primary care practitioner perspectives on the clinical utility of the NICE guideline and the impact of the QOF on diagnosis and management of depression in routine practice | 38 participants, including GPs, nurses, doctors in training, mental health workers, and a manager | Four diverse practices purposely identified, following a postal invitation to 26 practices in one region | Iterative, thematic and self-conscious; emergent content units identified, coded, grouped into themes, and compared across groups | Focus groups led by trained facilitator, using a topic guide; open questioning used, allowing participants to explore themes |

NICE = National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Table 3.

Summary of included studies for DEP5 assessment — effectiveness of assessment of severity

| Study reference | Study type | Aim of study | Number of participants | Characteristics of participants | Method of analysis | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang et al, 201214 and Yeung et al, 201223 | Quasi- randomised controlled trial | To assess whether communicating patient-reported depression symptom severity to primary care physicians affects patient outcomes at 6 months | 364 patients in the intervention group and 278 in a control group; 82 physicians enrolled at least 1 patient; 40 assigned to intervention, 43 to control | Patients: intervention 67.6% female control 64.6%; mean age 46.6 years(SD = 15.0 years), intervention; 45.3 years (SD = 15.4 years) control; physicians: most were family practice physicians or internists (intervention 65.8% and 26.3% respectively; control 50.0% and 47.4%); almost all were in private practice (92.11% intervention and 95.24% control) | PHQ-9 scores (administered by telephone as part of a monthly interview) faxed to the physician monthly for first 6 months | PHQ-9 scores (administered by telephone) at 3 and 6 months faxed the to physician at 6 months only |

| Malpass et al, 201019 | Mixed methods (PHQ-9 and in-depth interviews) | To explore the extent to which changes in PHQ-9 score over time reflect patients’ accounts of their experiences of depression during the same period; and to explore patients’ experiences of using the PHQ-9 within primary care consultations | 10 patients | Patients aged 18–75 years with a baseline PHQ-9>10; included if referred by GP to the study after consultation where antidepressants were prescribed, or records indicated a consultation for a new episode of depression; excluded if severely mentally ill, or unable to participate in interviews | PHQ-9 to assess the severity of depression over time | Patient-reported experience (through interview) |

| Moore et al, 201221 | Retrospective cohort study using primary care records | To determine whether there is evidence that GPs change treatment, or decide to refer, on the basis of a change in scores, in line with QOF indicators | 604 patients from 13 general practices | 69% female; mean age 44.4 years; 35% with previous history of depression; 18% with at least one comorbidity | Use of PHQ-9 in people with new diagnosis of depression and completed paired scores at onset and follow-up in line with QOF requirements | No comparator |

PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Table 4.

Summary of included studies for DEP5 experience

| Study reference | Study type | Aim of study | Number of participants | Characteristics of participants | Method of analysis | Methods: |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malpass et al, 201019 | Mixed methods (PHQ-9 and in-depth interviews) | To explore the extent to which changes in PHQ-9 score over time reflect patients’ accounts of their experiences of depression during the same period; and to explore patients’ experiences of using the PHQ-9 within primary care consultations | 10 patients | Patients aged 18–75 years with a baseline PHQ-9>10; included if referred by GP to study after consultation where antidepressants were prescribed, or records indicated a consultation for a new episode of depression; excluded if severely mentally ill, or unable to participate in interviews | Principles of constant comparison | Interviews at the patient’s home as soon as possible after the initial diagnosis, and at 3 and 6 months post diagnosis |

| Mitchell et al, 201120 | Focus groups of healthcare professionals from four general practices | To explore primary care practitioner perspectives on the clinical utility of the NICE guideline and the impact of the QOF on diagnosis and management of depression in routine practice | 38 participants, including GPs, nurses, doctors in training, mental health workers, and a manager | Four diverse practices purposely identified, following a postal invitation to 26 practices in one region | Iterative, thematic and self-conscious; emergent content units identified, coded, grouped into themes, and compared across groups | Focus groups led by trained facilitator, using topic guide; open questioning used, allowing participants to explore themes |

NICE = National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framework.

For further details of how the evidence is graded, see the NICE guidelines manual.13 GRADE profiles for the effectiveness studies are presented in Tables 5 & 6.

Table 5.

GRADE profile 1 assessment at diagnosis

| Number of studies | Design | Results | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness of assessment of severity | ||||||||

| 3: Kendrick et al, 200516 Kendrick et al, 200917 Smith et al, 201022 |

Observational | Rates of treatment and referral were higher with increased severity of depression when assessed using structured tools or GP perception of severity. GPs’ perceived severity of depression did not correspond to severity on the structured tool | No serious limitations | No serious inconsistency | Some serious indirectnessa | Some serious imprecisionb | None | VERY LOW |

Indirect outcomes of rates of treatment or referral; not depression outcomes (downgraded 1 level).

Where reported, some CIs were wide; however, this has not been downgraded, owing to the heterogeneity of results.

Table 6.

GRADE profile 2 assessment at follow-up

| Number of studies | Design | Results | Limitations | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness of assessment of severity | ||||||||

| 3: Chang et al, 201213 Malpass et al, 201018 Moore et al, 201220 Yeung et al, 201222 |

Quasi-randomised controlled trial and observational | Monthly feedback of severity scores to practitioners was associated with increased chances of remission and response to treatment. However, feedback was not associated with an increase in medication change, although discontinuation of medication was approximately half that of no monthly feedback. However, in another study, severity scores at follow-up were also associated with increased rates of management changes. Practitioners reported that they found the feedback useful and patients used the scores as a way to measure their own treatment response and recovery process | No serious limitations | Some serious inconsistencya | No serious indirectness | Some serious imprecisionb | None | LOWC |

Specifically around the impact on changes in management.

Where reported, some CIs were wide; however, this has not been downgraded, owing to the heterogeneity of results.

Initial level of MODERATE, owing to quasi randomised controlled trial study.

Assessment of severity at diagnosis

Assessment of depression severity at diagnosis, and its use to inform treatment is generally considered to be good practice,4 and increased severity of depression as assessed at diagnosis using structured tools or GP judgement is associated with higher rates of treatment and referral (based on very low-quality evidence). However, no evidence was found on whether structured assessment of severity and subsequent treatment based on the assessment resulted in improved outcomes, such as depression remission or improved quality of life.

Patients and GPs had different perceptions of assessing depression severity at diagnosis,15,18 with patients generally being more positive than GPs. For example, patients considered structured assessment to be an efficient addition to clinical judgement, while GPs perceived clinical judgement to be more important than an objective measure. GPs considered that routine use of questionnaire severity measures as incentivised by the QOF had a number of unintended consequences, specifically compromising the doctor–patient relationship, threatening holistic practice and intuition, interfering with the consultation process, and being mechanistic and intrusive.18,20 Concerns were also raised about the need to adapt questionnaires to different patient groups and how this affected the validity of the tools.20

Assessment of severity at follow-up

As at diagnosis, professional opinion supports assessment of depression severity at follow-up, and its use to evaluate treatment effectiveness. The score for assessment of severity broadly reflected patients’ accounts of the severity of depression over time. Severity scores were associated with changes in management; however, this was not a consistent finding across studies. Structured assessment of severity after diagnosis was associated with increased rates of remission and response, but changes in management were not seen. A proposed explanation was that the intervention may have influenced patient behaviour and thus led to improved outcomes.

As at diagnosis, GPs noted concerns about the need to adapt the questionnaires to different patient groups and how this affected the validity of the tools.20 However, some patients used the severity assessment at follow-up to measure and monitor their own treatment response and recovery process.19

DISCUSSION

Summary

Very limited evidence was found of the effectiveness of assessing depression severity using structured tools as incentivised in UK primary care by the QOF. No evidence was found on whether structured assessment of severity (either at diagnosis or follow-up) and subsequent treatment based on the assessment resulted in improved health outcomes, such as depression remission or improved quality of life. The assessment of depression severity at diagnosis, and its use to inform treatment, is generally considered to be good practice, and increased depression severity as assessed at diagnosis using structured tools or GP judgement is associated with higher rates of treatment and referral. As at diagnosis, professional opinion supports the assessment of severity of depression at follow-up, and its use to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment. The assessment of severity score broadly reflected patients’ accounts of the severity of their depression over time. This review shows that any estimate of the effect of the use of structured tools to assess severity in UK general practice is very uncertain and should not form the basis for a strong (‘should do’) recommendation for clinical practice.13,24 This uncertainty is reflected in the NICE depression clinical guidelines, where it is recommended that when assessing a person with suspected depression, the use of a validated measure (for example, for symptoms, functions and/or disability) be considered to inform and evaluate treatment, rather than being recommended as a ‘should do’.4,5

GPs considered that the routine use of depression severity structured tools as incentivised by the QOF had a number of unintended consequences, specifically compromising the doctor–patient relationship, threatening holistic practice and intuition, and interfering with the consultation process. In contrast, patients were more positive, seeing the tools as efficient and structured supplements to medical judgement and as evidence that GPs were taking their problems seriously, through full assessment of their patients’ depression.

Strengths and limitations

The main strengths of this review are its recognition of the need for setting-specific (UK primary care) evidence, its inclusive approach to the types of interventions studied, and its use of GRADE profiles. Although no randomised controlled trials were found, the researchers were able to consider observational evidence and, through the use of GRADE, assess confidence in the results, in a transparent and systematic way.

One limitation is that the study focused on the use of structured assessments in primary care alone; there may be evidence from other settings, such as hospital-based clinics, that care is improved through their use. However, it is not clear whether or how such evidence could be extrapolated to primary care populations.

Comparison with existing literature

This is the first systematic review to appraise the evidence of the effectiveness of assessing depression severity using structured tools, and any unintended consequences in UK primary care related to the use of two QOF depression severity indicators as reported by GPs and patients.

While making recommendations on this area, the NICE depression guidelines did not conduct a systematic review on the method of assessment of severity, and the NICE recommendations were made using expert opinion with documented consultation with professionals and wider stakeholders. However, it is notable that the NICE depression guidelines do not make a strong recommendation for the routine use of structured assessment tools in the assessment of depression severity, rather they state that clinicians should ‘consider using a validated measure to inform and evaluate treatment’.4,5 Such a weak recommendation, which makes explicit the need for clinical judgement and does not advocate the routine use of such tools, is consistent with the findings of this review. The conclusions of this review on effectiveness are supported by a psychometric assessment of the discriminatory performance of the three structured depression tools (PHQ-9, HADS-D and BDI-II) in UK general practice.25 This shows that none of these tools have optimal cut-off values with likelihood ratios that are adequate to inform clinical practice, and they are therefore inappropriate for use to assess depression severity in general practice.25

The qualitative studies reviewed here are specific to depression and the UK but the findings based on GP interviews are consistent with the wider international literature on pay-for-performance schemes. Studies of unintended consequences of indicators used in such schemes have shown they can lead to changes in the nature of the consultation/office visit, threats to the physician–patient relationship, and threats to professional autonomy.3

Implications for practice and research

The current QOF depression severity indicators (DEP4 and DEP5) incentivise routine use of structured assessment tools to assess depression severity at diagnosis and follow-up. This systematic review shows that it is very uncertain whether this leads to improved health outcomes for patients. These indicators, therefore, do not meet the criteria that indicators used in pay for performance should lead to improved health outcomes for patients and should not have major unintended consequences.26 Given these findings, the recommendations of NICE’s independent QOF Indicator Advisory Committee, that these indicators should be retired from the QOF,11 is consistent with this evidence review.

It should be noted that these indicators were developed using the previous QOF expert panel process,6 and the evidence base was not the subject of independent external review through public consultation, nor were the indicators piloted prior to their adoption (which should have allowed unintended consequences to have been identified). The new NICE QOF process uses an explicit guideline recommendation-driven approach,8 with piloting of indicators prior to any recommendation on their use.9,27 There is therefore scope to develop new QOF indicators on depression that have evidence to support their use to improve health outcomes for patients and are piloted prior to introduction, to minimise the risk of unintended consequences.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the GP academic advisers for their help with the study protocol and the late Helen Lester for her comments on the draft version of the paper.

Funding

Elizabeth J Shaw, Terence Lacey, and Daniel Sutcliffe are employees of NICE which is funded by the Department of Health to develop QOF indicators for publication on the NICE menu of indicators. Tim Stokes was an employee of NICE at the time the systematic review was conducted.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests.

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article on the Discussion Forum: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/bjgp-discuss

REFERENCES

- 1.Roland M. Linking physicians’ pay to the quality of care — a major experiment in the United Kingdom. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(14):1448–1454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr041294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Redesigning Health Insurance Performance Measures PaPIP . Rewarding provider performance: aligning incentives in Medicare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald R, Roland M. Pay for performance in primary care in England and California: comparison of unintended consequences. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(2):121–127. doi: 10.1370/afm.946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Depression. The treatment and management of depression in adults. CG90. London: NICE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem. Treatment and management. CG91. London: NICE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lester H, Campbell S. Developing Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) indicators and the concept of ‘QOFability’. Qual Prim Care. 2010;18(2):103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.NHS Employers . Quality and Outcomes Framework guidance for GMS contract 2011/12 Delivering investment in general practice. Leeds: NHS Employers; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . Developing clinical and health improvement indicators for the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) — interim process guide. London: NICE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutcliffe D, Lester H, Hutton J, Stokes T. NICE and the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) 2009–2011. Qual Prim Care. 2012;20(1):47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Primary Care QOF Advisory Committee Position statements. www.nice.org.uk/media/658/C6/Position_Statements.pdf (accessed 13 Mar 2013).

- 11.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence Special Health Authority Primary Care Quality and Outcomes Framework Indicator Advisory Committee Confirmed minutes of the December 2012 QOF Advisory Committee. www.nice.org.uk/media/717/B8/QOF_Independent_Primary_Care_QOF_Indicator_Advisory_Committee_021210_Confirmed_minutes.pdf (accessed 13 Mar 2013).

- 12.GRADE working group http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org (accessed 2 April 2013).

- 13.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence . The guidelines manual. London: NICE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang TE, Jing Y, Yeung AS, et al. Effect of communicating depression severity on physician prescribing patterns: findings from the Clinical Outcomes in Measurement-based Treatment (COMET) trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dowrick C, Leydon GM, McBride A, et al. Patients’ and doctors’ views on depression severity questionnaires incentivised in UK quality and outcomes framework: qualitative study. BMJ. 2009;338(7697):1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendrick T, King F, Albertella L, Smith PW. GP treatment decisions for patients with depression: an observational study. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(513):280–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kendrick T, Dowrick C, McBride A, et al. Management of depression in UK general practice in relation to scores on depression severity questionnaires: analysis of medical record data. BMJ. 2009;338:b750. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leydon GM, Dowrick CF, McBride AS, et al. Questionnaire severity measures for depression: a threat to the doctor–patient relationship? Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X556236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malpass A, Shaw A, Kessler D, Sharp D. Concordance between PHQ-9 scores and patients’ experiences of depression: a mixed methods study. Br J Gen Pract. 2010 doi: 10.3399/bjgp10X502119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mitchell C, Dwyer R, Hagan T, Mathers N. Impact of the QOF and the NICE guideline in the diagnosis and management of depression: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2011 doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X572472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moore M, Ali S, Stuart B, et al. Depression management in primary care: an observational study of management changes related to PHQ-9 score for depression monitoring. Br J Gen Pract. 2012 doi: 10.3399/bjgp12X649151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith MJ, Ackland L, O’Loughlin S, et al. ‘Doing well’: description of a complex intervention to improve depression care. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2010;11(4):326–38. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeung AS, Jing Y, Brenneman SK, et al. Clinical Outcomes in Measurement-based Treatment (COMET): a trial of depression monitoring and feedback to primary care physicians. Depress Anxiety. 2012;29(10):865–873. doi: 10.1002/da.21983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cameron IM, Cardy A, Crawford JR, et al. Assessing the validity of the PHQ-9, HADS, BDI-II and QIDS-SR16 in measuring of depression in a UK sample of primary care patients with a diagnosis of depression. Edinburgh: Healthcare Improvement Scotland; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chassin MR, Loeb JM, Schmaltz SP, Wachter RM. Accountability measures — using measurement to promote quality improvement. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):683–688. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1002320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell SM, Kontopantelis E, Hannon K, et al. Framework and indicator testing protocol for developing and piloting quality indicators for the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework. BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]