Abstract

OBJECTIVE

The fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) in the synovial intimal lining of the joint are key mediators of inflammation and joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In RA, these cells aggressively invade the extracellular matrix, producing cartilage-degrading proteases and inflammatory cytokines. The behavior of FLS is controlled by multiple interconnected signal transduction pathways involving reversible phosphorylation of proteins on tyrosine residues. However, little is known about the role of the protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs) in FLS function. The objective of this study was to explore the expression of all the PTP genes (PTPome) in FLS.

METHODS

A comparative screening was conducted of the expression of the PTPome in FLS from patients with RA or osteoarthritis (OA). The functional effect of a PTP up-regulated in RA, SHP-2, was then analyzed by knock-down using cell-permeable antisense oligonucleotides in RA FLS.

RESULTS

PTPN11 was over-expressed in RA compared to OA FLS. Knock-down of PTPN11, which encodes SHP-2, using a cell-permeable antisense oligonucleotide, decreased the invasion, migration, adhesion, spreading and survival of RA FLS. Additionally, signaling in response to growth factors and inflammatory cytokines was impaired by the knock-down of SHP-2. RA FLS deficient in SHP-2 displayed decreased activation of focal adhesion kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinases.

CONCLUSION

These findings indicate a novel role for SHP-2 in mediating human FLS function, and suggest that SHP-2 promotes the invasiveness and survival of RA FLS. Further investigation may reveal SHP-2 to be a candidate therapeutic target for RA.

The fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) present in the intimal lining of the synovium are primary pathogenic effectors in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (1–5). In healthy individuals, these mesenchymal-derived cells provide structural and dynamic support for diarthrodial joints and secrete components of synovial fluid. In RA however, FLS become aggressive and invasive, displaying some characteristics of transformed cells. RA FLS are resistant to apoptosis, and contribute to the inflammatory milieu by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines. They also secrete matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that break down the extracellular matrix and cartilage, participate in the bone-eroding pannus formation, and promote angiogenesis to the joint. Direct targeting of FLS in RA is increasingly being considered as an option for new therapies aimed at ameliorating the course of disease.

A complex network of intracellular signaling pathways controls the behavior of RA FLS (1, 3). Many of these pathways involve reversible phosphorylation of proteins on tyrosine residues (1). Tyrosine phosphorylation results from the balanced action of protein tyrosine kinases (PTKs) and phosphatases (PTPs) (6). The involvement of PTKs in FLS growth and invasiveness is currently under investigation. For example, several receptors for key pathogenic growth factors in RA, such as Fibroblast Growth Factor (FGF) and Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF), are active PTKs (7, 8). On the other hand, with the exception of the phosphoinositol-specific Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog (PTEN) and the dual-specificity (phosphoserine/phosphothreonine and phosphotyrosine) MAP Kinase Phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) (9, 10), the vast majority of PTPs controlling FLS intracellular signaling–including all of the tyrosine-specific enzymes – remains unexplored.

The human genome contains more than 100 PTPs (termed the PTPome (11)), which are divided into 4 classes (6). The Class I PTP subfamily includes most of the tyrosine-specific PTPs and several subfamilies of dual-specificity PTPs (DSPs). The Class II family contains a single gene, ACP1, encoding the low molecular weight PTP. The Class III family contains the Cell Division Cycle 25 (CDC25) subfamily of cell cycle regulators. The Class IV family contains the EYA genes, encoding the Eyes Absent PTPs, which employ a unique catalytic mechanism. Two novel PTPs have also been recently identified: Suppressor of SUa7, gene 2 (SSU72) (6, 12) and Ubiquitin-associated and SH3-domain containing A (UBASH3A) (13).

Here, we profiled the PTPome in human FLS. After first performing an expression survey in RA FLS, we next identified that PTPN11 is overexpressed in RA FLS compared to FLS from osteoarthritis (OA) patients. Further functional studies were performed on this gene, which encodes the SH2-domain Containing PTP 2 (SHP-2), a known proto-oncogene and drug target for cancer (14, 15). Consistent with its role as a very upstream promoter of growth factor and cytokine signaling (16), we found that SHP-2 promotes both survival and invasion of RA FLS. We propose a novel role for SHP-2 in mediating the aggressive phenotype of FLS in RA.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of FLS

FLS lines were obtained from the UCSD Clinical and Translational Research Institute (CTRI) Biorepository. Each FLS line used in this study had been obtained from a different patient with either RA or OA. Discarded synovial tissue from patients with OA and RA had been obtained at the time of total joint replacement or synovectomy, as previously described (17). The diagnosis of RA conformed to American College of Rheumatology 1987 revised criteria (18). FLS were cultured in DMEM (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Omega Scientific, Tarzana, CA), 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 μg/mL gentamicin, 100 units/ml of penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cells in this study were synchronized in 0.1% FBS (serum-starvation media) for 24–48 h before the addition of the appropriate stimuli.

Antibodies and Other Reagents

The anti-SHP-2 antibody was purchased from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA). All other primary antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Secondary antibodies were purchased from GE Healthcare Life Sciences (Pittsburgh, PA). TNFα, IL-1β and PDGF-BB were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Control non-targeting and anti-SHP-2 antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) were purchased from Gene Tools, LLC (Philomath, OR). Unless otherwise specified, chemicals and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR (qPCR)

Following cell synchronization for 48 h, cells were stimulated as indicated for 24 h or left unstimulated. RNA was extracted using RNeasy Kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Genomic DNA was removed using the TURBO-DNA Free Kit (Life Technologies). cDNA was synthesized using the RT2 First Strand Kit (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD). qPCR was performed using a Roche Lightcycler 480 (Indianapolis, IN), with individual primer assays and SYBR® Green qPCR Mastermix purchased from SABiosciences. Efficiency of the primer assays was guaranteed by the manufacturer to be greater than 90%. Each reaction was measured in triplicate and data was normalized to the expression levels of the house-keeping gene RNA Polymerase II (RPII) or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (19), also measured in triplicate. Absence of genomic DNA contamination was confirmed using control reactions lacking the reverse transcriptase enzyme during the cDNA synthesis step.

Western Blotting

Following 24-h serum-starvation and the indicated stimulations, cells were lysed in ice cold RIPA buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) with 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 5 mM sodium fluoride and 2 mM sodium pyrophosphate. Protein concentration of cell lysates was determined using the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL).

FLS Invasion Assays

The in vitro invasion assays were performed in Transwell systems as previously described (20, 21). Cells were pre-treated with 2.5 μM ASO for 6 days, followed by synchronization for 24 h in assay media (serum-free media with 0.5% BSA) supplemented with additional ASO, and then subjected to the invasion assays. In the 7-day assay, cells invaded through a thick extracellular matrix in response to 5% FBS, in the presence of additional ASO. In this assay, 35 μl of Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) Matrigel Matrix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) was coated onto Transwell inserts. In the 24-h assay, FLS invaded through BD BioCoat™ GFR Matrigel™ Invasion Chambers (BD Biosciences) in response to 50 ng/ml platelet-derived growth factor BB (PDGF-BB). Following staining with 50 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI), fluorescence of invading cells on each membrane was visualized using the Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) at 5x magnification. Images were acquired from 4–5 non-overlapping fields per membrane, and invading cells in each field were counted. Each experiment included 3–4 membranes per invading sample containing 5% FBS or PDGF in the lower compartment, and 2 membranes of a control non-invading sample.

FLS Migration Assays

Cells were pre-treated with 2.5 μM ASO for 6 days, followed by synchronization for 24 h in assay media (serum-free media with 0.5% BSA) supplemented with additional ASO. Cells were then stained with 2 μM CellTracker Green™ (Life Technologies) for 30 min and then allowed to migrate for 24 h through uncoated Transwell inserts in response to 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB. Fluorescence of migrated cells was visualized as above. For each FLS line tested, the assays included 3–4 membranes per migrating sample containing 5% FBS in the lower compartment, and 2 membranes of control non-migrating samples.

FLS Adhesion and Spreading Assays

Cells were pre-treated with 2.5 μM ASO for 6 days, followed by synchronization for 24 h in serum-starvation media in the presence of additional ASO. Equal cell numbers were then resuspended in complete media and allowed to adhere onto circular coverslips coated with 10 μg/ml fibronectin (FN) at 37°C for 15 min (adhesion assays) or 15, 30 and 60 min (spreading assays). Following the incubation period, cells were fixed in 4% para-formaldehyde for 5 min, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100 for 2 min, and stained with 5 U/ml Alexa Fluor® 568 (AF 568) phalloidin and 2 μg/ml Hoechst for 20 min each (Life Technologies). Samples were imaged with an Olympus FV10i Laser Scanning Confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA). Using the FV10i acquisition software, each circular coverslip of cells was separated into four nine-paneled mega-images. Each panel (1024×1024) was optically acquired with a 10x objective using the FV10i acquisition software and stitched together, through a 10% overlap, with the Olympus FluoView 1000 imaging software. Total cell number and cell areas for each panel were calculated using Image Pro Analyzer software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD).

FLS Transfection

OA FLS were transfected with a plasmid encoding hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged SHP-2 in the pEF-HA vector (22), or with empty vector, using the Amaxa Human Dermal Fibroblast Nucleofector Kit (Lonza, Allendale, NJ). After 24 h, cells were serum-starved for an additional 24 h prior to the indicated analyses.

FLS Survival and Apoptosis Assays

Cells were treated with 2.5 μM ASO for 6 days, followed by synchronization for 24 h in serum-starvation media supplemented with additional ASO. Cells were washed and incubated for an additional 24 h in serum-starvation media containing the indicated stimulant. Adherent and non-adherent cells were collected and stained with Annexin V-Alexa Fluor® 647 and PI according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Biolegend, San Diego, CA). Cell fluorescence was assessed by FACS using a BD LSR-II.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed as indicated in the Figure Legends using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). A comparison was considered significant if p was less than 0.05.

Results

PTPs from all subfamilies are expressed in human FLS

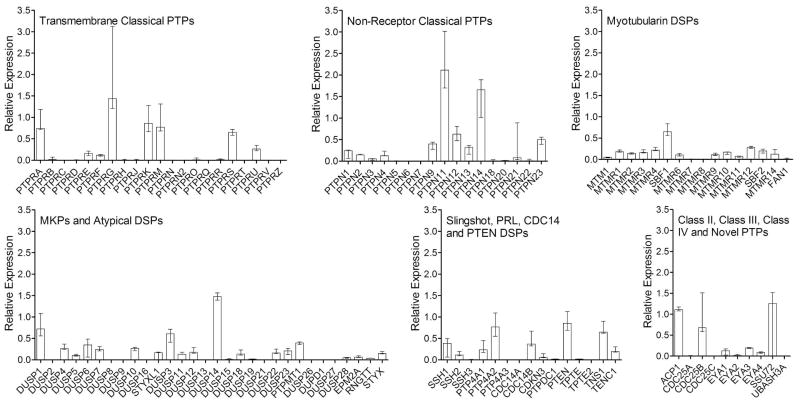

To investigate the role of PTPs in FLS function, we first profiled the PTPome in human RA FLS. We analyzed the mRNA expression of all PTPs in 3 separate FLS lines from RA synovial tissues and found PTPs from all subfamilies are expressed (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Expression of the PTPome in human RA FLS.

The expression of PTPs in 3 RA FLS lines was measured by qPCR following cell synchronization for 48 h. Panels show the median±range of the PTP expression from the 3 lines relative to the housekeeping gene RPII, according to the PTP subfamilies classified in (6): the Transmembrane Classical PTPs, the Non-Receptor Classical PTPs, the Myotubularin DSPs, the MKPs and Atypical DSPs, the Slingshot, PRL, CDC14 and PTEN DSPs, the Class II, Class III and Class IV PTPs, and the 2 novel PTPs SSU72 and UBASH3A.

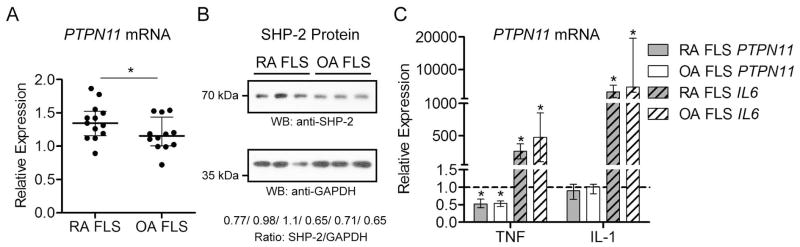

PTPN11 expression is increased in RA FLS

Comparison of the expression of PTPs in FLS obtained from 3 RA patients to 3 OA patients revealed increased expression of PTPN11 in RA FLS (data not shown). PTPN11 is a known proto-oncogene encoding the SH2 domain-containing PTP-2 (SHP-2), a cytosolic PTP and promoter of growth factor and cytokine receptor signaling (14, 23). Given the aggressive features of FLS in RA, and the proto-oncogenic nature of SHP-2, we reasoned there might be a role for this PTP in RA FLS physiopathology. As shown in Figure 2A, we retested the expression of PTPN11 in a further set of FLS lines from 13 RA and 12 OA patients, and confirmed that PTPN11 expression is significantly increased in RA compared to OA FLS (Median relative expression, 1.35 and IQR, 1.16–1.52 for RA FLS; Median relative expression 1.15 and IQR, 1.00–1.44 for OA FLS, p<0.05). We next tested whether SHP-2 protein levels were also increased, and found that SHP-2 levels were modestly higher in total lysates from 3 RA compared to 3 OA FLS lines (Figure 2B).

Figure 2. PTPN11 expression is increased in RA compared to OA FLS.

(A) The expression of PTPN11 in 13 RA FLS lines was compared to the expression in 12 OA lines. Panel shows median±interquartile range (IQR) PTPN11 expression relative to the housekeeping gene RPII. Significance was calculated using the Mann-Whitney test. *, p<0.05 (B) SHP-2 protein levels are higher in RA than OA FLS. Panels show Western blotting of lysates from 3 RA and 3 OA FLS lines with the indicated antibodies. Ratios of SHP-2/GAPDH expression as assessed by densitometric scanning of the blots are shown. (C) PTPN11 expression is reduced in RA and OA FLS after TNF, but not IL-1 stimulation. The expression of PTPN11 and as a positive control, IL6, was measured by qPCR in 8 RA and 8 OA FLS lines following stimulation with 50 ng/ml TNFα or 2 ng/ml IL-1β for 24 h. Graph shows median±IQR expression level relative to the unstimulated samples from the same lines following normalization to the housekeeping gene RPII. Dotted line indicates relative expression level of 1.0 (no change). Significance was calculated using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. *, p<0.05.

TNF stimulation decreases PTPN11 expression

Given the abundance of inflammatory cytokines in the RA synovium and the status of TNF as a target of therapy for RA (24), we compared the expression of PTPN11 in unstimulated RA or OA FLS to PTPN11 expression in cells stimulated with TNF or IL-1. As shown in Figure 2C, the expression of PTPN11 in RA and OA FLS is significantly reduced in response to TNF, but not IL-1, stimulation.

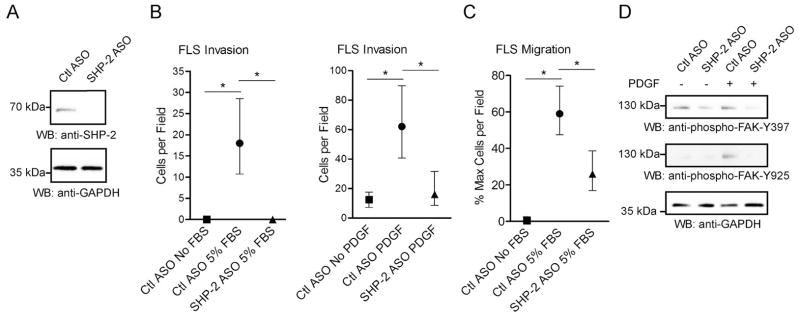

SHP-2 knock-down inhibits RA FLS invasiveness

We next explored the possibility that reduced expression of SHP-2 could inhibit the ex vivo invasiveness of RA FLS, an FLS phenotype that has been shown to correlate with radiographic damage in RA (21). To perform these studies we utilized a cell-permeable antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) (25) to knock-down SHP-2 expression in RA FLS. As shown in Figure 3A, the ASO enables nearly complete knock-down of SHP-2 without need of electroporation or a transfection reagent. We subjected the ASO-treated cells to Transwell invasion assays through Matrigel matrix. As shown in Figure 3B, RA FLS treated with SHP-2 ASO, compared to control non-targeting ASO-treated cells, demonstrated significantly impaired invasiveness in response to 5% FBS (Median cells per field, 18.00, and IQR, 10.75–28.50 for Ctl ASO; Median cells per field, 0 and IQR, 0 for SHP-2 ASO; p<0.05) and PDGF (Median cells per field, 62.00, and IQR, 40.75–89.75 for Ctl ASO; Median cells per field, 16.0 and IQR, 8.50–31.50 for SHP-2 ASO; p<0.05).

Figure 3. SHP-2 knock-down inhibits RA FLS invasion, migration and FAK phosphorylation.

(A) RA FLS were treated with 2.5 μM control (Ctl) or SHP-2 ASO for 7 days and cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting. Data are representative of 5 independent experiments in different lines. (B) Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, RA FLS were allowed to invade through Matrigel-coated transwell chambers. Graphs show median±IQR cells per field following 7-day invasion in response to 5% FBS (left panel) or 24-h invasion in response to 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB (right panel). Data are each representative of 2 independent experiments in different lines. (C) Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, RA FLS were allowed to migrate through uncoated chambers. Graph shows median±IQR % maximum number of cells per field of 3 different RA FLS lines following 24-h migration. Significance in (B and C) was calculated using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. *, p<0.05. (D) Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, RA FLS were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB for 30 min or left unstimulated. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments in different lines.

Loss of SHP-2 in RA FLS impairs FLS migration and phosphorylation of FAK

To understand the mechanism of the decreased invasiveness of RA FLS by SHP-2 knockdown, we assessed the effect of SHP-2 ASO on RA FLS migration. As shown in Figure 3C, SHP-2-ASO-treated cells were significantly less efficient at migration than Ctl ASO-treated cells (Median % maximum cells per field, 59.01, and IQR, 47.45–74.12 for Ctl ASO; Median % maximum cells per field, 25.96 and IQR, 16.99–38.70 for SHP-2 ASO; p<0.05). The effect of SHP-2 on FLS motility suggested involvement of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase, which has been shown to promote motility of both fibroblasts and cancer cells (26, 27). Thus we next analyzed the effect of SHP-2 deficiency on activation of FAK. As shown in Figure 3D, SHP-2 knock-down decreased the basal levels of FAK phosphorylation on Y397, a FAK autophosphorylation site and substrate of Src family kinases. PDGF-induced phosphorylation of FAK on Y925, a substrate of Src family kinases, was also reduced.

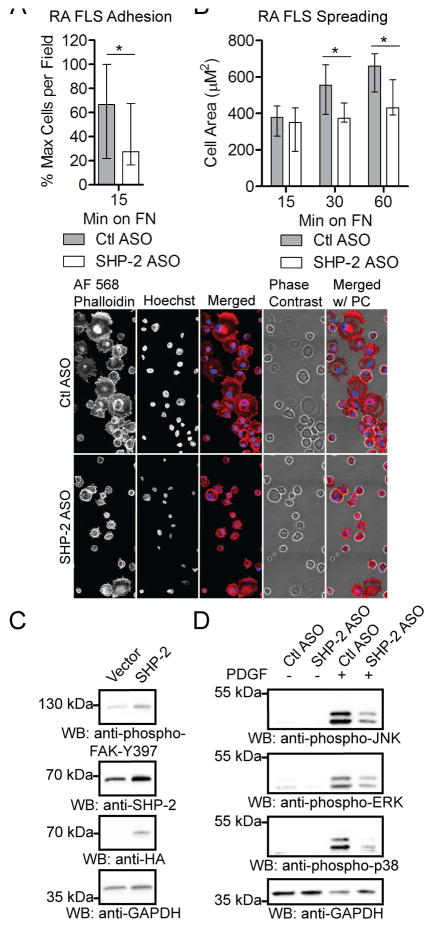

SHP-2 knock-down inhibits RA FLS adhesion, spreading and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs)

We next tested the effect of SHP-2 knock-down on RA FLS adhesion and spreading, both FAK-regulated cellular functions (26). Consistent with the decreased phosphorylation of FAK, SHP-2 ASO-treated cells were significantly less adherent to, and displayed significantly impaired spreading on, fibronectin (FN)-coated coverslips compared to Ctl ASO-treated cells (Figures 4A and 4B). These results are consistent with previous findings that loss of SHP-2 in murine embryonic fibroblasts impairs focal adhesion maturation, leading to defective cell spreading (28). We reasoned that increased SHP-2 expression in OA FLS would promote phosphorylation of FAK, and as shown in Figure 4C, we found that a low level of overexpression of SHP-2 was sufficient to increase the phosphorylation of FAK on Y397 in these cells. We also found that SHP-2 knock-down led to reduced PDGF-induced activation of MAPKs in RA FLS, as evidenced by reduced phosphorylation of c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK), Extracellular signal Regulated Kinase (ERK) and p38 MAPKs (Figure 4D). These findings suggest that SHP-2 contributes to the aggressive phenotype of RA FLS through promotion of FAK and downstream MAPK activation.

Figure 4. SHP-2 promotes FAK-mediated FLS function.

(A) SHP-2 knock-down inhibits RA FLS adhesion. Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, RA FLS were plated onto FN-coated coverslips. Graph shows median±IQR % maximum number of cells per field of 3 different RA FLS lines. (B) SHP-2 knock-down inhibits RA FLS spreading. Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, RA FLS were plated onto FN-coated coverslips. Upper panel shows median±IQR cell area of 4 different RA FLS lines. Lower panel shows representative image of cells 60 min after plating on FN. Significance in (A and B) was calculated using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. *, p<0.05. (C) SHP-2 overexpression increases phosphorylation of FAK in OA FLS. OA FLS were transfected with HA-tagged SHP-2 or empty vector. Data is representative of 3 independent experiments in different lines. (D) SHP-2 knock-down impairs activation of MAPKs. Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, RA FLS were stimulated with 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB for 30 min or left unstimulated. Data is representative of 5 independent experiments in different lines.

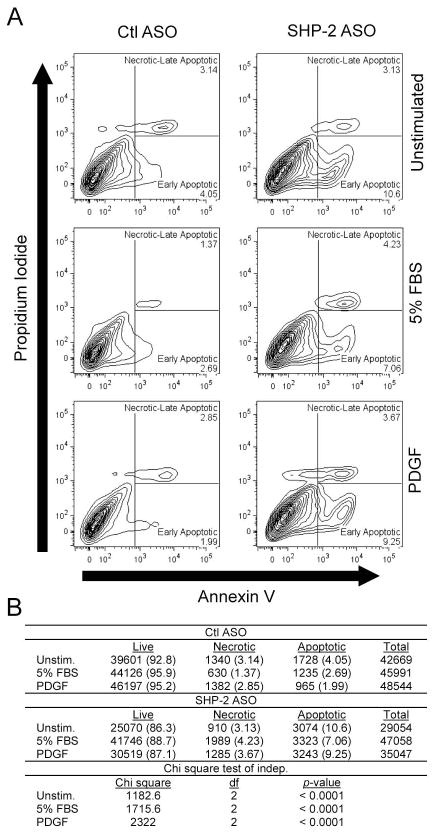

SHP-2 knock-down inhibits survival of RA FLS

As activation of FAK is known to inhibit apoptosis (27), we assessed whether SHP-2 deficiency affects the survival of RA FLS. As shown in Figure 5, the SHP-2-ASO-treated cells showed significantly increased apoptosis compared to control ASO-treated cells, an effect which remained after stimulation with 5% FBS or platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF).

Figure 5. SHP-2 knock-down increases apoptosis of RA FLS.

Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, RA FLS were left unstimulated or stimulated with 5% FBS or 50 ng/ml PDGF-BB. After 24 h, cells were collected and stained with Annexin V and PI, and cell fluorescence was assessed by FACS. (A) Plots show percentage of early apoptotic (Annexin V+PI−) and necrotic/late apoptotic (Annexin V+PI+) cells. (B) Significance of data in (A) was calculated using a Chi-square test for independence. Cell numbers for each sample are shown. Cell percentages are indicated in parentheses. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments in different FLS lines.

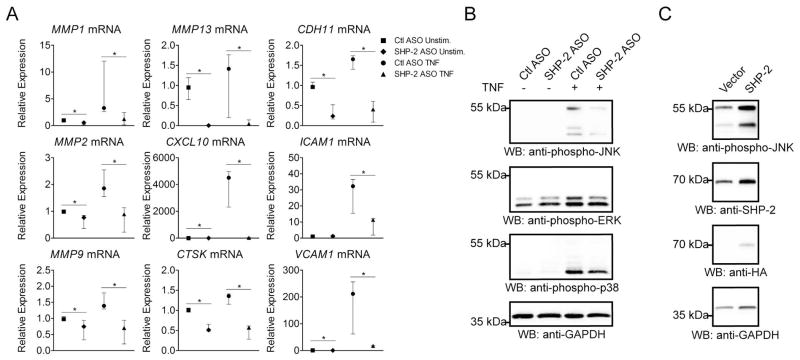

SHP-2 knock-down inhibits TNF-induced gene expression and signaling in RA FLS

The rheumatoid synovium is characterized by overexpression of multiple inflammatory cytokines, including TNF (24). To further explore the role of SHP-2 in RA FLS function in conditions close to those present in the rheumatoid synovium, we investigated the effects of SHP-2 knock-down on TNF signaling in RA FLS. As secretion of inflammatory cytokines and invasiveness are critical pathogenic characteristics of FLS in RA, we assessed the effect of SHP-2 ASO on TNF-inducible expression of genes encoding the inflammatory cytokines interleukin 6 (IL-6) and interleukin 8 (IL-8), and mediators of invasion, the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), Cathepsin K (CTSK), C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10), Cadherin-11 (CDH11), Intercellular Adhesion Molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 (VCAM-1) (1, 20, 21, 29–32). As shown in Figure 6A, SHP-2 deficiency led to significantly decreased induction of many genes critical for FLS invasion, including MMP1, MMP2, MMP9, MMP13, CTSK, CXCL10, CDH11, ICAM1 and VCAM1. Interestingly, SHP-2 did not affect the TNF-induced expression of IL6, IL8, MMP3 or MMP10 (data not shown). We next assessed the effect of SHP-2 ASO treatment on TNF-induced activation of MAPKs in RA FLS, and found that RA FLS treated with SHP-2 ASO showed reduced phosphorylation of the MAPKs upon TNF stimulation, most notably, JNK (Figure 6B). Finally, we tested whether increased expression of SHP-2 in OA FLS would promote TNF signaling. As shown in Figure 6C, overexpression of SHP-2 in these cells increased phosphorylation of JNK upon TNF stimulation.

Figure 6. SHP-2 promotes TNF-induced signaling in RA FLS.

(A) SHP-2 knockdown in RA FLS decreases TNF-induced expression of proteases, cytokines and adhesion molecules. Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml TNFα for 24 h or left unstimulated. Graph shows the median±IQR relative mRNA expression levels from 3 (MMP1, MMP2, CXCL10, CTSK, CDH11, ICAM1 and VCAM1) or 4 (MMP9 and MMP13) different RA FLS lines, following normalization to GAPDH. Significance was calculated using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. *, p<0.05. (B) SHP-2 knock-down inhibits TNF-induced phosphorylation of JNK in RA FLS. Following treatment with Ctl or SHP-2 ASO, cells were stimulated with 50 ng/ml TNFα for 15 min or left unstimulated. (C) SHP-2 overexpression increases TNF-induced phosphorylation of JNK in OA FLS. Cells were transfected with HA-SHP-2 or empty vector. After 24 h, cells were serum-starved for an additional 24 h, then stimulated with 50 ng/ml TNFα for 15 min. Data in (B and C) are each representative of 3 independent experiments in different FLS lines.

Discussion

We report the first unbiased expression survey of the PTPome in RA FLS. Comparative analysis revealed PTPN11 displayed modest, yet functionally significant overexpression in RA compared to OA FLS. This gene attracted our attention, as it is a proto-oncogene whose gain-of-function mutations lead to leukemias, breast cancer and other neoplastic syndromes (14, 23). In addition, a genome-wide association study revealed that the PTPN11 locus is located within a linkage disequilibrium block associating with rheumatoid arthritis (33). The phosphatase encoded by PTPN11, SHP-2, promotes cell survival, migration and invasiveness, and is currently considered a drug target for treatment of cancer (15, 34–39). Here we report a new role for SHP-2 in promoting the survival and invasiveness of RA FLS.

As the aggressive phenotype of RA FLS parallels that of transformed cells (1), it is possible that the molecular mechanisms underlying alterations in gene expression in RA FLS are similar to those found in neoplastic cells. Since mutations in proto-oncogenes are found in many cancers (16), it is possible that the aberrant expression pattern of this gene in RA is due to somatic mutations or epigenetic anomalies, such as altered DNA methylation patterns or altered histone modification. Further mutational and epigenetic analysis of the PTPN11 gene is likely to reveal mechanisms by which it is increased in RA.

In this study we optimized the use of a novel cell-permeable ASO (25) targeted against SHP-2. Treatment of RA FLS with the SHP-2 ASO led to remarkably efficient SHP-2 knock-down without need of electroporation or a transfection reagent. Using this approach we demonstrated that RA FLS subjected to knock-down of SHP-2 show impaired adhesiveness, spreading, motility and invasiveness, impaired responsiveness to growth factor and inflammatory cytokine stimulation, and increased susceptibility to apoptosis. Functional analysis positioned SHP-2 upstream the activation of FAK, and showed SHP-2 affects the activation of the JNK, p38 and ERK MAPKs in RA FLS. To explore the potential of SHP-2 inhibition for abrogating the aggressiveness of RA FLS, we also characterized the effect of SHP-2 knock-down on responsiveness of FLS to stimulation by TNF, a prominent inflammatory cytokine of the rheumatoid synovium (1). SHP-2 deficiency led to decreased TNF-induced JNK activation and expression of a variety of mediators of FLS invasiveness, including collagenases (MMP-1 and MMP-3), gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), the cysteine protease Cathepsin K, adhesion molecules (Cadherin-11, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) and the chemokine CXCL10 (1, 20, 21, 29–32). We also found that PTPN11 levels are reduced in RA FLS upon TNF stimulation, suggesting perhaps that regulation of SHP-2 levels may function as a negative feedback mechanism in TNF signaling.

SHP-2 is a ubiquitously expressed cytosolic PTP that is recruited to receptors for growth factors and cytokines, or their associated adaptor proteins, and promotes activation of the Ras and Rho-families of small GTPases, and downstream MAPKs (14, 16, 37, 40). SHP-2 is critical for migration and invasion of fibroblasts and tumor cells (34, 35, 37). PTPN11 was also the first proto-oncogene identified to encode a PTP (14). Somatic gain-of-function mutations occur in several types of hematologic malignancies, including juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia, and more rarely, in adult leukemias (41). Mutations or induction of PTPN11 have also been found in multiple solid tumors (14, 16, 42).

FLS subjected to SHP-2 knock-down display reduced basal phosphorylation of FAK on Y397, and reduced PDGF-induced phosphorylation on Y925. FAK is a critical mediator of cell motility and invasiveness, and has been shown to activate MAPKs through activation of Rho- and Ras-GTPases (26). FAK also promotes resistance to apoptosis (27). The activation of FAK is dependent upon phosphorylation on Y397 induced by integrin-mediated cell adhesion (26). This site can be autophosphorylated by FAK, and also acts as a substrate for Src. Phospho-Y397 provides a docking site for Src, which then phosphorylates other tyrosine residues of FAK, including Y925, resulting in FAK activation. Increased levels of phospho-FAK were shown in lining cells from RA synovial tissue compared to normal tissue (43). SHP-2 has been shown to regulate the activation of FAK by multiple groups. While some studies have indicated SHP-2 promotes dephosphorylation of FAK, possibly to regenerate active FAK through a recycling mechanism (34, 35), others have shown that SHP-2 enhances phosphorylation and activation of FAK by inhibiting phosphorylation of the inhibitory tyrosine residue of Src family kinases by C-terminal Src family kinase (CSK) (44, 45). We have extended the role of SHP-2 in the regulation of FAK to FLS, and propose that SHP-2 acts upstream to promote the phosphorylation of FAK in this cell type.

Our data suggest that SHP-2 promotes the invasiveness of RA FLS through a collective effect of multiple mechanisms, including impaired adhesion, spreading and motility, increased apoptosis, decreased activation of MAPKs and decreased MMP expression. The loss of motility of SHP-2-deficient cells parallels that of FAK-deficient cells (46), suggesting that decreased FAK activation mediates the reduced motility of FLS subjected to SHP-2 knockdown. FAK downregulation also correlates well with reduced JNK activation and MMP secretion, as Rac1-dependent activation of JNK has been shown to increase production of MMP-2 and MMP-9 downstream of FAK activation (26, 27). Furthermore, FAK is a known promoter of cell survival, suggesting that the effect of SHP-2 on RA FLS apoptosis might also be at least partially mediated by FAK. Interestingly, the anti-TNF drug Etanercept was recently shown to induce apoptosis of FLS through inhibition of FAK phosphorylation on Y397 (47). Although it is tempting to speculate that decreased basal activation of FAK at least partially underlies all the phenotypes observed after knock-down of SHP-2, further experimentation is needed to demonstrate that FAK mediates the action of SHP-2 in RA FLS. SHP-2 is known to promote MAPK activation through additional mechanisms and regulates a multitude of additional intracellular pathways. Further investigation of the mechanism of action of SHP-2 in RA FLS is certainly warranted.

The results in this study suggest that inhibition of SHP-2 in RA may decrease FLS invasiveness and resistance to apoptosis, and thus may provide a beneficial therapeutic effect. As global deletion of SHP-2 in mice causes embryonic lethality (48), alternative strategies such as pharmacological inhibition or use of inducible knockout models will need to be employed in order to explore the potential of SHP-2 as a therapeutic target for RA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Amgen (N.B.) and NIH (G.S.F.; AR47825, AI070555, and Clinical and Translational Science Award UL1TR000100). H.A.A. is employed by and received support from Amgen.

We are grateful to Dr. Maripat Corr (Division of Rheumatology, Allergy and Immunology, UCSD School of Medicine) for critical review of the manuscript, to Dr. Bjoern Peters (Division of Vaccine Discovery, La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology) for guidance in statistical analysis, and to the UCSD CTRI Biorepository for assisting with the FLS lines. This is manuscript number 1526 from the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology.

References

- 1.Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunological reviews. 2010;233(1):233–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noss EH, Brenner MB. The role and therapeutic implications of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in inflammation and cartilage erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunological reviews. 2008;223:252–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ospelt C, Gay S. The role of resident synovial cells in destructive arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22(2):239–52. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefevre S, Knedla A, Tennie C, Kampmann A, Wunrau C, Dinser R, et al. Synovial fibroblasts spread rheumatoid arthritis to unaffected joints. Nat Med. 2009;15(12):1414–20. doi: 10.1038/nm.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kontoyiannis D, Kollias G. Fibroblast biology. Synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis: leading role or chorus line? Arthritis Res. 2000;2(5):342–3. doi: 10.1186/ar109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the human genome. Cell. 2004;117(6):699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumkumian GK, Lafyatis R, Remmers EF, Case JP, Kim SJ, Wilder RL. Platelet- derived growth factor and IL-1 interactions in rheumatoid arthritis. Regulation of synoviocyte proliferation, prostaglandin production, and collagenase transcription. Journal of immunology. 1989;143(3):833–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melnyk VO, Shipley GD, Sternfeld MD, Sherman L, Rosenbaum JT. Synoviocytes synthesize, bind, and respond to basic fibroblast growth factor. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(4):493–500. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toh ML, Yang Y, Leech M, Santos L, Morand EF. Expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase 1, a negative regulator of the mitogen-activated protein kinases, in rheumatoid arthritis: up-regulation by interleukin-1beta and glucocorticoids. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50(10):3118–28. doi: 10.1002/art.20580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pap T, Franz JK, Hummel KM, Jeisy E, Gay R, Gay S. Activation of synovial fibroblasts in rheumatoid arthritis: lack of Expression of the tumour suppressor PTEN at sites of invasive growth and destruction. Arthritis Res. 2000;2(1):59–64. doi: 10.1186/ar69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tautz L, Pellecchia M, Mustelin T. Targeting the PTPome in human disease. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2006;10(1):157–77. doi: 10.1517/14728222.10.1.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Zhang M. Crystal structure of Ssu72, an essential eukaryotic phosphatase specific for the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II, in complex with a transition state analogue. The Biochemical journal. 2011;434(3):435–44. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen JN, Mortensen OH, Peters GH, Drake PG, Iversen LF, Olsen OH, et al. Structural and evolutionary relationships among protein tyrosine phosphatase domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(21):7117–36. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7117-7136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan RJ, Feng GS. PTPN11 is the first identified proto-oncogene that encodes a tyrosine phosphatase. Blood. 2007;109(3):862–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-028829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang ZX, Zhang ZY. Targeting PTPs with small molecule inhibitors in cancer treatment. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2008;27(2):263–72. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan G, Kalaitzidis D, Neel BG. The tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 (PTPN11) in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27(2):179–92. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvaro-Gracia JM, Zvaifler NJ, Brown CB, Kaushansky K, Firestein GS. Cytokines in chronic inflammatory arthritis. VI. Analysis of the synovial cells involved in granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor production and gene expression in rheumatoid arthritis and its regulation by IL-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Journal of immunology. 1991;146(10):3365–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radonic A, Thulke S, Mackay IM, Landt O, Siegert W, Nitsche A. Guideline to reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2004;313(4):856–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laragione T, Brenner M, Mello A, Symons M, Gulko PS. The arthritis severity locus Cia5d is a novel genetic regulator of the invasive properties of synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(8):2296–306. doi: 10.1002/art.23610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolboom TC, van der Helm-Van Mil AH, Nelissen RG, Breedveld FC, Toes RE, Huizinga TW. Invasiveness of fibroblast-like synoviocytes is an individual patient characteristic associated with the rate of joint destruction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):1999–2002. doi: 10.1002/art.21118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Von Willebrand M, Jascur T, Bonnefoy-Berard N, Yano H, Altman A, Matsuda Y, et al. Inhibition of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase blocks T cell antigen receptor/CD3-induced activation of the mitogen-activated kinase Erk2. Eur J Biochem. 1996;235(3):828–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan G, Kalaitzidis D, Neel BG. The tyrosine phosphatase Shp2 (PTPN11) in cancer. Cancer metastasis reviews. 2008;27(2):179–92. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thalayasingam N, Isaacs JD. Anti-TNF therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2011;25(4):549–67. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morcos PA, Li Y, Jiang S. Vivo-Morpholinos: a non-peptide transporter delivers Morpholinos into a wide array of mouse tissues. Biotechniques. 2008;45(6):613–4. 6, 8. doi: 10.2144/000113005. passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(1):56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanks SK, Ryzhova L, Shin NY, Brabek J. Focal adhesion kinase signaling activities and their implications in the control of cell survival and motility. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d982–96. doi: 10.2741/1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herrera Abreu MT, Wang Q, Vachon E, Suzuki T, Chow CW, Wang Y, et al. Tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 regulates IL-1 signaling in fibroblasts through focal adhesions. J Cell Physiol. 2006;207(1):132–43. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiener HP, Niederreiter B, Lee DM, Jimenez-Boj E, Smolen JS, Brenner MB. Cadherin 11 promotes invasive behavior of fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60(5):1305–10. doi: 10.1002/art.24453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laragione T, Brenner M, Sherry B, Gulko PS. CXCL10 and its receptor CXCR3 regulate synovial fibroblast invasion in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3274–83. doi: 10.1002/art.30573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou WS, Li Z, Gordon RE, Chan K, Klein MJ, Levy R, et al. Cathepsin k is a critical protease in synovial fibroblast-mediated collagen degradation. Am J Pathol. 2001;159(6):2167–77. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63068-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seemayer CA, Kuchen S, Kuenzler P, Rihoskova V, Rethage J, Aicher WK, et al. Cartilage destruction mediated by synovial fibroblasts does not depend on proliferation in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(5):1549–57. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64289-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhernakova A, Stahl EA, Trynka G, Raychaudhuri S, Festen EA, Franke L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies in celiac disease and rheumatoid arthritis identifies fourteen non-HLA shared loci. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(2):e1002004. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu DH, Qu CK, Henegariu O, Lu X, Feng GS. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2 regulates cell spreading, migration, and focal adhesion. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273(33):21125–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang FM, Liu HQ, Liu SR, Tang SP, Yang L, Feng GS. SHP-2 promoting migration and metastasis of MCF-7 with loss of E-cadherin, dephosphorylation of FAK and secretion of MMP-9 induced by IL-1beta in vivo and in vitro. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89(1):5–14. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-1002-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neel BG, Gu H, Pao L. The ‘Shp’ing news: SH2 domain-containing tyrosine phosphatases in cell signaling. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28(6):284–93. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feng H, Liu KW, Guo P, Zhang P, Cheng T, McNiven MA, et al. Dynamin 2 mediates PDGFRalpha-SHP-2-promoted glioblastoma growth and invasion. Oncogene. 2012;31(21):2691–702. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Wang S, Yu WM, Zhang W, McCrae KR, Neel BG, Qu CK. Noonan syndrome/leukemia-associated gain-of-function mutations in SHP-2 phosphatase (PTPN11) enhance cell migration and angiogenesis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284(2):913–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804129200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott LM, Lawrence HR, Sebti SM, Lawrence NJ, Wu J. Targeting protein tyrosine phosphatases for anticancer drug discovery. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(16):1843–62. doi: 10.2174/138161210791209027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kontaridis MI, Eminaga S, Fornaro M, Zito CI, Sordella R, Settleman J, et al. SHP-2 positively regulates myogenesis by coupling to the Rho GTPase signaling pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(12):5340–52. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.12.5340-5352.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bentires-Alj M, Paez JG, David FS, Keilhack H, Halmos B, Naoki K, et al. Activating mutations of the noonan syndrome-associated SHP2/PTPN11 gene in human solid tumors and adult acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res. 2004;64(24):8816–20. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhou XD, Agazie YM. Inhibition of SHP2 leads to mesenchymal to epithelial transition in breast cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(6):988–96. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shahrara S, Castro-Rueda HP, Haines GK, Koch AE. Differential expression of the FAK family kinases in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis synovial tissues. Arthritis research & therapy. 2007;9(5):R112. doi: 10.1186/ar2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oh ES, Gu H, Saxton TM, Timms JF, Hausdorff S, Frevert EU, et al. Regulation of early events in integrin signaling by protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(4):3205–15. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang SQ, Yang W, Kontaridis MI, Bivona TG, Wen G, Araki T, et al. Shp2 regulates SRC family kinase activity and Ras/Erk activation by controlling Csk recruitment. Mol Cell. 2004;13(3):341–55. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ilic D, Furuta Y, Kanazawa S, Takeda N, Sobue K, Nakatsuji N, et al. Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;377(6549):539–44. doi: 10.1038/377539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pattacini L, Boiardi L, Casali B, Salvarani C. Differential effects of anti-TNF-alpha drugs on fibroblast-like synoviocyte apoptosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49(3):480–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saxton TM, Henkemeyer M, Gasca S, Shen R, Rossi DJ, Shalaby F, et al. Abnormal mesoderm patterning in mouse embryos mutant for the SH2 tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2. EMBO J. 1997;16(9):2352–64. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]