Abstract

Human sirtuin1 (SIRT1), the closest homolog of the yeast sir2 protein, functions as an NAD+-dependent histone and non-histone protein deacetylase in several cellular processes, like energy metabolism, stress responses, aging, etc. In our recent study, we have shown that lamin A (a major nuclear matrix protein) directly binds with and activates SIRT1. Resveratrol, a natural phenol, has long been known as an activator of SIRT1. However, resveratrol’s direct activation of SIRT1 has been refuted several times. In our study, we have provided a mechanistic explanation to this question, and have shown that resveratrol activates SIRT1 by increasing its binding with lamin A, thus aiding in the nuclear matrix (NM) localization of SIRT1. We have also shown that rescue of adult stem cell (ASC) decline in laminopathy-based premature aging mice by resveratrol is SIRT1-dependent. Further, resveratrol’s ameliorating effects on progeria and its capacity to extend lifespan in progeria mice has been established. Here we have summarized these findings and their probable implications on other aspects, like chromatin remodeling, stem cell therapy, DNA damage responses, etc.

Keywords: SIRT1, Lamin A, resveratrol, nuclear matrix, Zmpste24, progeria, adult stem cells

Sirtuins are the NAD+-dependent histone and non-histone protein deacetylases widely distributed from yeast to mammals. They also function as mono-ribosyltransferases. They were first identified in yeast and were named sir2 after the gene “silent mating-type information regulator 2,” which is responsible for cellular regulation in yeast. These class III histone deacetylases (HDACs) are highly conserved in nature. To date, seven human sirtuins (SIRT1–7) have been reported out of which SIRT1 is the most extensively studied.1-5

The research on sirtuins got a major thrust after the finding that calorie restriction leads to the extension of rat lifespan.6,7 Although several signaling pathways have been shown to mediate the impact of caloric restriction on aging, SIRT1 emerged as a promising target because of its functions at the regulatory crossroad between nutrient sensing, energy metabolism and genome stability.8-12 Because of SIRT1’s varied effects on several life processes like promoting insulin sensitivity, improving genomic stability, suppressing tumors, reducing inflammation, regulating stress resistance, etc., it was speculated that SIRT1 could also have a potential role in modulating lifespan via caloric restriction.13-16 This triggered the search for screening out potential activators of SIRT1, which could aid in extension of lifespan. In this search, resveratrol emerged as a potent SIRT1 activator that could also mimic the effects of calorie restriction.18,19 Resveratrol has been found to promote longevity in yeast, worms and short-lived fish, but its role in lifespan extension has been questioned in flies.20-24 Although many of resveratrol’s in vivo effects are found to be SIRT1-dependent, the mechanism by which it activates SIRT1 remains poorly understood.25,26

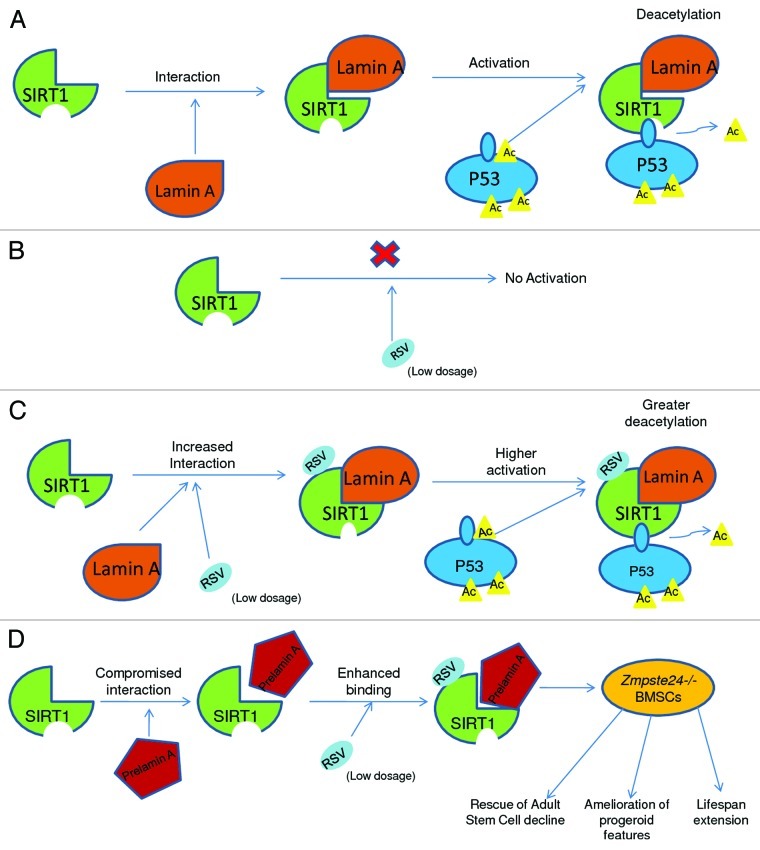

In our recent paper,34 this mystery is resolved to a great extent, and a mechanistic explanation of resveratrol’s activation of SIRT1 has been provided. It is shown that lamin A directly interacts with and activates SIRT1. This interaction is compromised in the presence of prelamin A and progerin (mutant forms of lamin A), which are present in adult stem cells from Zmpste24−/− mice and Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) fibroblasts, respectively. We have provided evidence that resveratrol increases the binding between SIRT1 and A-type lamins and enhances its deacetylase activity. This further aids in restoration of adult stem cell (ASC) population, amelioration of progeroid features and extension of lifespan in Zmpste24−/− progeroid mice (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration showing (A) Lamin A interacts with SIRT1 to activate it causing further deacetylation of P53. (B) Resveratrol (RSV) in itself cannot activate SIRT1. (C) Resveratrol (RSV) further increases interaction between SIRT1 and Lamin A to enhance its deacetylation activity toward P53. (D) SIRT1’s interaction with prelamin A is compromised, but resveratrol (RSV) treatment enhances this binding, resulting in amelioration of progeroid features in Zmpste24−/− bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs).

Lamins are intermediate filament proteins that form a major component of the nuclear matrix (NM) and regulate the nuclear shape and structure. NM also associates with a vast number of histone deacetylases, thus regulating chromatin structure. There are two types of lamins, A-type (encoded by the LMNA focus and comprising the splice isoforms lamin A and lamin C) and B-type (lamin B1, B2).27-30,35 The predominant cause of HGPS, an early onset premature aging, is a de novo mutation in LMNA gene causing alternative splicing, thus resulting in a truncated prelamin A, termed as progerin.31 The lack of functional metalloproteinase ZMPSTE24, which is responsible for prelamin A maturation, also results in progeroid features in mice and humans.32,33 Taking into consideration that NM has a prominent role in preserving histone deacetylase (HDAC) activity, we questioned the impact of prelamin A on SIRT1. Consequently, lamin A emerged not only as a novel interacting partner of SIRT1, but also as its activator. However, lamin C (differing from lamin A only in the C-terminal domain)36 showed negligible interaction with SIRT1, indicating that lamin A possibly interacts with SIRT1 via its C-terminal domain. To provide evidence, a synthetic peptide (LA-80) containing the carboxyl 80 amino acids of lamin A was used, and the effect of SIRT1’s deacetylase activity on its native target, acetyl p53 was observed.17 As predicted, the LA-80 peptide increased SIRT1’s deacetylase activity in vitro in a dose-dependent manner. Interestingly, resveratrol significantly enhanced SIRT1’s deacetylase activity toward full-length p53 only in the presence of recombinant lamin A (rhLamin A) and not in its absence. This further indicates that resveratrol is not a direct activator of SIRT1. Surprisingly, rhLamin A could independently increase rhSIRT1’s deacetylase activity, though not as much as in addition with resveratrol. So while investigating the plausible reason of this observation, we found that resveratrol further enhances the interaction between lamin A and SIRT1 both in vivo and in vitro. Thus, we provided a novel mechanism of how resveratrol activates SIRT1 and showed that this activation is lamin A-mediated.

Having known that lamin A interacts with SIRT1 via its C-terminal tail, we next questioned if the binding between SIRT1 and prelamin A or progerin is impaired in comparison with lamin A. In our co-immunoprecipitation studies, we noted that prelamin A or progerin have a considerable decrease in the interaction with SIRT1. Given the fact that lamin A is a major component of the nuclear matrix (NM), we further asked if SIRT1 was associated with the NM. As hypothesized, we found NM fraction to be enriched with SIRT1. Consistent with our results of SIRT1’s lesser binding with prelamin A and progerin, we observed a huge decline of NM-associated SIRT1 in Zmpste24−/− bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs) as compared with wild type controls. A similar reduction was also seen in HGPS dermal fibroblasts. Collectively, these data suggest that the normal localization of SIRT1 on NM is compromised in the presence of prelamin A or progerin. While investigating the functional significance of this phenomenon, we found that the mislocalization of SIRT1 resulted in an appreciable reduction in its deacetylase activity. FOXO3a (a downstream target of SIRT1)16,37 was found to be hyper-acetylated in Zmpste24−/− BMSCs. Moreover, ectopic expression of either prelamin A or progerin further enhanced Foxo3a acetylation. Given that resveratrol could enhance lamin A-SIRT1 interaction, we further investigated if it could also increase NM localization of SIRT1. Consistent with our previous data, we found that resveratrol enhanced the localization of SIRT1 on NM by increasing its binding with lamin A.

We observed a significant decline of BMSCs in Zmpste24−/− mice as compared with wild type controls. This decline could be attributable to the compromised colony-forming capacity, reduced proliferation and increased cellular senescence observed in Zmpste24−/− BMSCs. Given that resveratrol’s enhancement of SIRT1 deacetylase activity is lamin A-dependent and SIRT1 (highly expressed in stem cells)38 is essential for the maintenance of stem cell renewal and function,39 we investigated the effect of resveratrol on adult stem cells. Intriguingly, we found a dose-dependent enhancement of colony-forming capacity in Zmpste24−/− BMSCs by resveratrol treatment. The treatment also increased the association of SIRT1 to prelamin A and downregulated FOXO3a acetylation. Upon knocking down SIRT1, resveratrol’s stimulating effect was attenuated. These data suggest that a major cause of BMSC decline in Zmpste24−/− mice is the impairment of SIRT1 function, which can be rescued by resveratrol. In addition to this, resveratrol treatment for 4 months in Zmpste24−/− mice ameliorated progeroid features and extended lifespan significantly.

There has been a huge debate in the past decade regarding the resveratrol activation of SIRT1. The idea of its being a direct activator of SIRT1 has been refuted in several independent studies. However, no mediating factor has been highlighted so far.26,40-45 Our study, for the first time, addresses this question and provides evidence that resveratrol mediates its activating effects on SIRT1 by increasing its interaction with lamin A and thus helps in the NM localization of SIRT1. Although this study brings forth a novel explanation to the resveratrol-SIRT1 mystery, it also crops up several unanswered questions. For example, the questions like whether resveratrol increases binding capacity of other SIRT1 activators or inhibitors, whether other resveratrol mimics can also activate SIRT1 in a similar fashion, how resveratrol enhances binding capacity of A-type lamins to SIRT1, etc. still remain to be addressed. As SIRT1 is involved in numerous cellular processes and signaling pathways,46-53 the effect of its novel interaction with lamin A on other downstream targets await to be explored. The implications of this finding in the field of chromatin remodeling, cancer, energy metabolism and several other cellular processes are enormous. For example, the effect of resveratrol-mediated enhancement of SIRT1-lamin A interaction in the epigenetic modifications of histone H4K16 and their further implications (if any) are still unknown. This can provide valuable insights into the DNA damage responses regulated by chromatin remodeling in progeroid conditions.54,55 It is also possible that this interaction affects various SIRT1 targets in different organs in order to bring about metabolic homeostasis in the organism.56 However, SIRT1’s significance in promoting cancer protection by dietary restriction in mammals has been questioned.57 Apart from these, it would be interesting to extrapolate our findings to the poly (ADP-ribosyl) polmerases (PARPs)-SIRT1 story and try to examine if PARP1 and/or PARP2 could somehow influence SIRT1-Lamin A interaction.58 Our finding further raises the possibility that a peptide mimicking lamin A’s C-terminal tail might have therapeutic benefits in improving health status in HGPS patients by activating SIRT1. This can prove to be a potential breakthrough in the treatment of laminopathy-based progeroid pathologies. Given SIRT1’s critical role in stem cells self-renewal and the requirement of NM association of SIRT1 for its activation, it is highly probable that resveratrol can serve as a beneficial drug in stem cell therapy for various degenerative disorders.59

It has been reported that c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK1) phosphorylates SIRT1, which further enhances its nuclear localization and enzymatic activity toward histone H3 in response to oxidative stress. Moreover, DYRK1A, DYRK3 and CK2 are also shown to phosphorylate SIRT1, thereby activating it to promote cell survival and cellular response to DNA damage, respectively.60-62 SIRT1 phosphorylation is shown to modulate its oligomeric status to make it more active.63 This raises the possibility of a synergistic effect between these kinases and lamin A for activating SIRT1 in response to oxidative and genotoxic stress. It is also probable that SIRT1 phosphorylation might enhance its interaction with lamin A to further activate it. Thus, our data insinuate at several other related aspects, which, if investigated, have the potential to provide therapeutic benefits in the field of cancer, aging, defects in metabolism and also stress responses.

Acknowledgments

This project is supported by research grants from Research Grant Council of Hong Kong (CRF/HKU3/07C) and Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2011CB964700).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/24061

References

- 1.Shore D, Squire M, Nasmyth KA. Characterization of two genes required for the position-effect control of yeast mating-type genes. EMBO J. 1984;3:2817–23. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02214.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michishita E, Park JY, Burneskis JM, Barrett JC, Horikawa I. Evolutionarily conserved and nonconserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:4623–35. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunders LR, Verdin E. Sirtuins: critical regulators at the crossroads between cancer and aging. Oncogene. 2007;26:5489–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frye RA. Phylogenetic classification of prokaryotic and eukaryotic Sir2-like proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;273:793–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haigis MC, Sinclair DA. Mammalian sirtuins: biological insights and disease relevance. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:253–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osborne TB, Mendel LB, Ferry EL. The effect of retardation of growth upon the breeding period and duration of life of rats. Science. 1917;45:294–5. doi: 10.1126/science.45.1160.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCay C, Crowell MF, Maynard LA. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of lifespan and upon the ultimate body size. J Nutr. 1935;10:63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spindler SR. Caloric restriction: from soup to nuts. Ageing Res Rev. 2010;9:324–53. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen D, Steele AD, Lindquist S, Guarente L. Increase in activity during calorie restriction requires Sirt1. Science. 2005;310:1641–41. doi: 10.1126/science.1118357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Xu W, McBurney MW, Longo VD. SirT1 inhibition reduces IGF-I/IRS-2/Ras/ERK1/2 signaling and protects neurons. Cell Metab. 2008;8:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oberdoerffer P, Michan S, McVay M, Mostoslavsky R, Vann J, Park SK, et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell. 2008;135:907–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu J, Auwerx J. Protein deacetylation by SIRT1: an emerging key post-translational modification in metabolic regulation. Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bordone L, Cohen D, Robinson A, Motta MC, van Veen E, Czopik A, et al. SIRT1 transgenic mice show phenotypes resembling calorie restriction. Aging Cell. 2007;6:759–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Firestein R, Blander G, Michan S, Oberdoerffer P, Ogino S, Campbell J, et al. The SIRT1 deacetylase suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis and colon cancer growth. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshizaki T, Milne JC, Imamura T, Schenk S, Sonoda N, Babendure JL, et al. SIRT1 exerts anti-inflammatory effects and improves insulin sensitivity in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1363–74. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00705-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunet A, Sweeney LB, Sturgill JF, Chua KF, Greer PL, Lin Y, et al. Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science. 2004;303:2011–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaziri H, Dessain SK, Ng Eaton E, Imai SI, Frye RA, Pandita TK, et al. hSIR2(SIRT1) functions as an NAD-dependent p53 deacetylase. Cell. 2001;107:149–59. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00527-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baur JA, Pearson KJ, Price NL, Jamieson HA, Lerin C, Kalra A, et al. Resveratrol improves health and survival of mice on a high-calorie diet. Nature. 2006;444:337–42. doi: 10.1038/nature05354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagouge M, Argmann C, Gerhart-Hines Z, Meziane H, Lerin C, Daussin F, et al. Resveratrol improves mitochondrial function and protects against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell. 2006;127:1109–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, et al. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature. 2003;425:191–6. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, et al. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature. 2004;430:686–9. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valenzano DR, Terzibasi E, Genade T, Cattaneo A, Domenici L, Cellerino A. Resveratrol prolongs lifespan and retards the onset of age-related markers in a short-lived vertebrate. Curr Biol. 2006;16:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agarwal B, Baur JA. Resveratrol and life extension. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2011;1215:138–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bass TM, Weinkove D, Houthoofd K, Gems D, Partridge L. Effects of resveratrol on lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:546–52. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baur JA. Biochemical effects of SIRT1 activators. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1626–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villalba JM, de Cabo R, Alcain FJ. A patent review of sirtuin activators: an update. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2012;22:355–67. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.669374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruenbaum Y, Margalit A, Goldman RD, Shumaker DK, Wilson KL. The nuclear lamina comes of age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:21–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dittmer TA, Misteli T. The lamin protein family. Genome Biol. 2011;12:222. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-5-222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsutsui KM, Sano K, Tsutsui K. Dynamic view of the nuclear matrix. Acta Med Okayama. 2005;59:113–20. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies BS, Fong LG, Yang SH, Coffinier C, Young SG. The posttranslational processing of prelamin A and disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:153–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eriksson M, Brown WT, Gordon LB, Glynn MW, Singer J, Scott L, et al. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature. 2003;423:293–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pendás AM, Zhou Z, Cadiñanos J, Freije JM, Wang J, Hultenby K, et al. Defective prelamin A processing and muscular and adipocyte alterations in Zmpste24 metalloproteinase-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 2002;31:94–9. doi: 10.1038/ng871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergo MO, Gavino B, Ross J, Schmidt WK, Hong C, Kendall LV, et al. Zmpste24 deficiency in mice causes spontaneous bone fractures, muscle weakness, and a prelamin A processing defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13049–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192460799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu B, Ghosh S, Xi Y, Zheng H, Liu X, Wang Z, et al. Resveratrol rescues Sirt1-dependent adult stem cell decline and alleviates progeroid features in laminopathy-based progeria. 2012;16:738–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendzel MJ, Delcuve GP, Davie JR. Histone deacetylase is a component of the internal nuclear matrix. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:21936–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu B, Zhou Z. Lamin A/C, laminopathies and premature ageing. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:747–63. doi: 10.14670/HH-23.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang F, Nguyen M, Qin FX, Tong Q. SIRT2 deacetylates FOXO3a in response to oxidative stress and caloric restriction. Aging Cell. 2007;6:505–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saunders LR, Sharma AD, Tawney J, Nakagawa M, Okita K, Yamanaka S, et al. miRNAs regulate SIRT1 expression during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation and in adult mouse tissues. Aging (Albany NY) 2010;2:415–31. doi: 10.18632/aging.100176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Han MK, Song EK, Guo Y, Ou X, Mantel C, Broxmeyer HE. SIRT1 regulates apoptosis and Nanog expression in mouse embryonic stem cells by controlling p53 subcellular localization. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:241–51. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pacholec M, Bleasdale JE, Chrunyk B, Cunningham D, Flynn D, Garofalo RS, et al. SRT1720, SRT2183, SRT1460, and resveratrol are not direct activators of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8340–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai H, Kustigian L, Carney D, Case A, Considine T, Hubbard BP, et al. SIRT1 activation by small molecules: kinetic and biophysical evidence for direct interaction of enzyme and activator. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:32695–703. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.133892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaeberlein M, McDonagh T, Heltweg B, Hixon J, Westman EA, Caldwell SD, et al. Substrate-specific activation of sirtuins by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17038–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500655200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beher D, Wu J, Cumine S, Kim KW, Lu SC, Atangan L, et al. Resveratrol is not a direct activator of SIRT1 enzyme activity. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2009;74:619–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2009.00901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Borra MT, Smith BC, Denu JM. Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17187–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Timmers S, Auwerx J, Schrauwen P. The journey of resveratrol from yeast to human. Aging (Albany NY) 2012;4:146–58. doi: 10.18632/aging.100445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lavu S, Boss O, Elliott PJ, Lambert PD. Sirtuins--novel therapeutic targets to treat age-associated diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:841–53. doi: 10.1038/nrd2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith BC, Hallows WC, Denu JM. Mechanisms and molecular probes of sirtuins. Chem Biol. 2008;15:1002–13. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fusco S, Maulucci G, Pani G. Sirt1: def-eating senescence? Cell Cycle. 2012;11:4135–46. doi: 10.4161/cc.22074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calvanese V, Fraga MF. SirT1 brings stemness closer to cancer and aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:162–7. doi: 10.18632/aging.100272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pardo PS, Boriek AM. The physiological roles of Sirt1 in skeletal muscle. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:430–7. doi: 10.18632/aging.100312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fatoba ST, Okorokov AL. Human SIRT1 associates with mitotic chromatin and contributes to chromosomal condensation. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2317–22. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.14.15913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Milner J, Allison SJ. SIRT1, p53 and mitotic chromosomes. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:3049–50. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.18.16994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stein S, Matter CM. Protective roles of SIRT1 in atherosclerosis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:640–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.4.14863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Krishnan V, Chow MZY, Wang Z, Zhang L, Liu B, Liu X, et al. Histone H4 lysine 16 hypoacetylation is associated with defective DNA repair and premature senescence in Zmpste24-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12325–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102789108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu B, Wang Z, Ghosh S, Zhou Z. Defective ATM-Kap-1-mediated chromatin remodeling impairs DNA repair and accelerates senescence in progeria mouse model. Aging Cell. 2012 doi: 10.1111/acel.12035. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Laurène V, Maechler P. Resveratrol-activated SIRT1 in liver and pancreatic β-cells: a Janus head looking to the same direction of metabolic homeostasis. Aging. 2011;4:444–9. doi: 10.18632/aging.100304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Herranz D, Iglesias G, Muñoz-Martín M, Serrano M. Limited role of Sirt1 in cancer protection by dietary restriction. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:2215–7. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.13.16185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cantó C, Auwerx J. Interference between PARPs and SIRT1: a novel approach to healthy ageing? Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3:543–7. doi: 10.18632/aging.100326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singec I, Jandial R, Crain A, Nikkhah G, Snyder EY. The leading edge of stem cell therapeutics. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:313–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.070605.115252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nasrin N, Kaushik VK, Fortier E, Wall D, Pearson KJ, de Cabo R, et al. JNK1 phosphorylates SIRT1 and promotes its enzymatic activity. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guo X, Williams JG, Schug TT, Li X. DYRK1A and DYRK3 promote cell survival through phosphorylation and activation of SIRT1. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13223–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kang H, Jung JW, Kim MK, Chung JH. CK2 is the regulator of SIRT1 substrate-binding affinity, deacetylase activity and cellular response to DNA-damage. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo X, Kesimer M, Tolun G, Zheng X, Xu Q, Lu J, et al. The NAD(+)-dependent protein deacetylase activity of SIRT1 is regulated by its oligomeric status. Sci Rep. 2012;2:640. doi: 10.1038/srep00640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]