Abstract

Objective

Chronic migraineurs (CM) have painful intolerances to somatosensory, visual, olfactory and auditory stimuli during and between migraine attacks. These intolerances are suggestive of atypical affective responses to potentially noxious stimuli. We hypothesized that atypical resting state functional connectivity (rs-fc) of affective pain processing brain regions may associate with these intolerances. This study compared rs-fc of affective pain processing regions in CM to controls.

Methods

Twelve minutes of resting blood oxygenation level dependent data were collected from 20 interictal adult CM and 20 controls. Rs-fc between 5 affective regions (anterior cingulate cortex, right/left anterior insula, and right/left amygdala) with the rest of the brain was determined. Functional connections consistently differing between CM and controls were identified using summary analyses. Correlations between number of migraine years and the strengths of functional connections that consistently differed between CM and controls were calculated.

Results

Functional connections with affective pain regions that differed in CM and controls included regions in anterior insula, amygdala, pulvinar, mediodorsal thalamus, middle temporal cortex, and periaqueductal gray. There were significant correlations between number of years with CM and functional connectivity strength between the anterior insula with mediodorsal thalamus and anterior insula with periaqueductal gray.

Conclusions

CM is associated with interictal atypical rs-fc of affective pain regions with pain-facilitating and pain-inhibiting regions that participate in sensory-discriminative, cognitive, and integrative domains of the pain experience. Atypical rs-fc with affective pain regions may relate to aberrant affective pain processing and atypical affective responses to painful stimuli characteristic of CM.

Keywords: Migraine, Chronic Migraine, Headache, Functional Connectivity, Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Pain

Introduction

Migraine afflicts 36 million Americans annually, causing pain, decreased quality of life, and impaired physical, social, and occupational functioning.1-2 While most people with migraine have a few headache days per month, 2% of Americans have chronic migraine (CM), a condition in which headaches occur on ≥15 days/month, with full-blown migraine on ≥8 of those days.3 Although headache is typically the most obvious symptom of migraine, migraineurs also have painful hypersensitivities and reduced tolerance to sound, light, odor and cutaneous stimulation.4-5 These painful hypersensitivities and reduced tolerance to environmental stimuli are most prominent during migraine attacks, but often persist with less magnitude between attacks (“interictally”).5-7

Pain perception is a complex process involving pain-facilitating and pain-inhibiting brain regions that play different roles in pain processing: sensory-discriminative (intensity, location, modality), affective (pain tolerance, self-awareness, fear, anxiety), cognitive (attention, expectation, pain memory), and integration of these different pain aspects with other sensory modalities (multisensory convergence).8-10 Pain detection thresholds (first instant that a stimulus is detected as painful) are thought to be indicative of sensory-discriminative processing of potentially noxious stimuli, while pain tolerance thresholds (first instant that a person decides they can no longer tolerate the painful stimulus) are considered indicative of affective responses to such stimuli.11-12 Migraineurs typically have reduced tolerance of somatosensory, auditory, visual and olfactory stimuli and prior fMRI studies suggest atypical affective processing of stimuli by the migraine brain.13-15 Thus, we focused on investigating the resting state functional connectivity (rs-fc) of brain regions responsible for affective processing of noxious stimuli.

Resting state functional connectivity magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fcMRI) is based on the observation that spontaneous, low frequency (<0.1 Hz) blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal fluctuations in spatially distant but functionally related brain regions are temporally correlated at rest.16 Rs-fcMRI allows for visualization and measurement of the brain’s intrinsic functional architecture.17-18 The rs-fc among brain regions may change over time according to usual brain activity and needs.19 Thus, regions of the brain that are frequently co-activated may, over time, develop a stronger rs-fc even when not being engaged by an external task (during the resting state).19-20 Atypical rs-fc among regions of resting state networks and between established networks has been identified in patients with several different medical disorders.21-22 Prior rs-fc studies in migraine have shown migraineurs to have atypical rs-fc of several regions that participate in pain processing including regions participating in pain integration (e.g. anterior temporal pole), affective processing (e.g. anterior cingulate cortex), and pain modulation (e.g. periaqueductal gray), as well as atypical rs-fc within regions of the default mode network, executive network, and salience network.23-28 In the present study, rs-fcMRI was used to investigate whether CM, a disorder consisting of frequent headaches and aberrant affective responses to stimuli perceived as painful (e.g. cutaneous stimulation, light, noise), is associated, interictally, with atypical rs-fc of affective pain processing regions.

Methods

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Following institutional review board approval, 20 CM subjects diagnosed using International Classification of Headache Disorders II (ICHD-II) criteria were enrolled.29 Subjects were excluded if they met ICHD-II criteria for medication overuse, had contraindications to MRI, neurologic disorders other than migraine, psychiatric disorders other than anxiety or depression, or pain disorders other than migraine. Use of medications considered migraine prophylactics was permitted as long as there were no changes in medications or dosages within 8 weeks of study participation. Extant data from healthy controls who were not taking medications and who were studied using the same imaging protocols, were used for comparison. All subjects provided written informed consent for study participation.

Clinical Parameters

Data collected from chronic migraineurs included: 1) Number of years with migraine; 2) Number of years with CM; 3) Headache frequency; 4) Current medications; 5) Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) score; 6) Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score; and 7) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) scores.30-32

Imaging Protocol

Migraineurs were studied when migraine free ≥48 hours and migraine abortive medication free ≥48 hours. Controls were in their usual healthy state at the time of imaging. Images were obtained on Siemens MAGNETOM Trio 3T scanners (Erlangen, Germany) with total imaging matrix (TIM) technology using12-channel head matrix coils. Structural anatomic scans included a high-resolution T1-weighted sagittal magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) series (TR 2400ms, TE 1.13ms, 176 slices, 1.0mm^3 voxels) and a coarse T2-weighted turbo spin echo (TSE) series (TR 6150, TE 86.0, 36 axial slices, 1×1×4mm^3 voxels). Functional imaging used a BOLD contrast-sensitive sequence (T2* evolution time = 25 ms, flip angle = 90°, resolution = 4×4×4 mm). Whole-brain EPI (echo planar imaging) volumes (MR frames) of 36 contiguous, 4mm thick axial slices were obtained every 2.2 seconds. BOLD data were collected in two 6 minute runs during which subjects were instructed to relax with their eyes closed.

Data Processing and Analysis

All analyses were performed using in-house software (FIDL analysis package, http://www.nil.wustl.edu/labs/fidl/index.html) that has been utilized in numerous previously published studies.33-35 fMRI BOLD data were preprocessed via standard methods used in our lab.35-37 Briefly, all images from a single subject were combined into a 4-dimensional (x,y,z, time) time-series and adjusted for timing offsets using sinc interpolation. Images were adjusted for the slice intensity differences introduced by contiguous interleaved slice acquisition. Next, a 6- parameter rigid body realignment process was used to minimize movement-induced noise across all frames in all runs for each subject. Images were resliced by 3D cubic spline interpolation. Data were transformed into a common stereotactic space based on Talairach and Tournoux (1988) but using an in-house atlas composed of the average anatomy of 12 healthy young adults (ages 21-29 years) (see Lancaster et al., 1995; Snyder, 1996 for methods).38-39 As part of the atlas transformation the data were resampled isotropically at 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm. Registration was accomplished via a 12-parameter affine warping of each individual’s MP-RAGE to the atlas target, using difference image variance minimization as the objective function. Subjects’ T2-weighted images were used as intermediate targets for transforming the BOLD images. The atlas-transformed images were checked against a reference average to ensure appropriate registration. Rs-fc pre-processing included removal of the linear trend, temporal band-pass filtering (.009 Hz<f<.08 Hz), Gaussian blur of 2 voxels FWHM, as well as regression of several “noise” parameters (6 motion parameters and signals from whole brain, white matter and ventricles) and their time-based derivatives.16, 40 Data volumes (i.e., MR frames) likely to be contaminated with motion-related artifact that was not addressed by standard movement regression routines were identified and eliminated using a volume-censoring technique.41 Data volumes with a frame by frame movement >0.5mm or a whole brain change >0.5% were identified and eliminated.

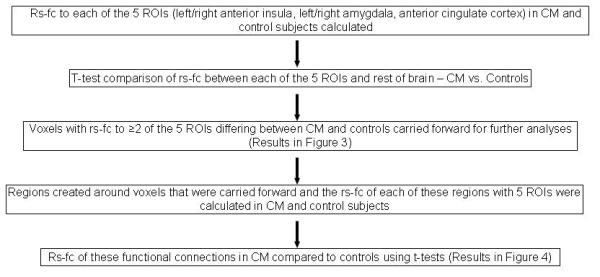

Rs-fc analyses [methods summarized in Figure 1] employed a region of interest (ROI)-based approach using 5 a priori selected regions that participate in affective pain processing. Rs-fc maps were derived using 10mm diameter spherical ROIs centered on: left anterior insula (Montreal Neurological Institute coordinates −35, 18, −1), right anterior insula (36, 19, −2), left amygdala (−21, −3, −27), right amygdala (20, −3, −28), and anterior cingulate cortex (−1, 10, 32). Coordinates were selected based upon those reported in the pain and headache literature.8, 42-45 For each seed, a resting state time-series was extracted separately for each subject by computing the mean of the BOLD intensity of all voxels enclosed by the seed region boundaries at each MR frame (time-point). Correlations with this time-series were calculated for each voxel in the brain, then Fisher z-transformed to produce a functional connectivity map for each seed in each subject.

Figure 1. Flow-Diagram Summarizing the Methods Used to Analyze Resting State Data.

Rs-fc = resting state functional connectivity; ROI = region of interest; CM = chronic migraine

To determine the rs-fc of the 5 affective pain ROIs, t-tests were used to identify functional connections with the 5 pain ROIs that differed from zero (p ≤ .01, uncorrected). Since rs-fc with 5 different ROIs was investigated, summary analyses were used to identify voxels that were involved in functional connections with at least 2 of the 5 a priori selected ROIs.16, 46-47

To investigate rs-fc differences between CM and control subjects, the rs-fc of the 5 pain ROIs in CM were compared to the rs-fc in controls using two-sample t-tests. Summary analyses of the two-sample t-tests were used to find consistent differences between CM and controls. Summary analyses stipulated that only those voxels exhibiting significant differences between control and CM in 2 or more of the 5 affective pain ROIs were carried forward for further analyses.16. 46-47 Regions were created based upon the results of these summary analyses using an in-house peak-finding algorithm. The rs-fc of these non-overlapping regions with each of the 5 a priori selected pain ROIs was determined for each subject. Functional connectivity strengths (i.e. correlation coefficients) of these region pairs in CM were compared to strengths in controls using two-sample t-tests. Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple comparisons allowing for false discovery rate of 5% was employed to identify functional connections significantly differing between subject groups.

To explore associations between atypical rs-fc and duration of migraine, Pearson correlations of functional connections that were atypical in CM with number of CM years were calculated. Correlations with an uncorrected p ≤ 0.05 were considered significant. Correlations between functional connection strength with depression and anxiety scores, possible mediators of rs-fc amongst our pain ROIs were also calculated. When rs-fc was significantly correlated with number of migraine years and depression or anxiety scores, the amount of variance in functional connectivity strength attributable to each variable (i.e. number of chronic migraine years, anxiety, depression) was calculated.

To investigate a potential influence of migraine prophylactic medication use on study results, post-hoc analyses were performed comparing whole brain rs-fc of the 5 pain ROIs in migraineurs taking prophylactic medications (n=8) to migraineurs not taking prophylactic medications (n=12). The rs-fc of the 5 pain ROIs in migraine subjects taking prophylactic medications were compared to the rs-fc in migraine subjects not using prophylactic medications via two-sample t-tests. Overlay images were used to identify voxels with rs-fc that significantly differed when comparing migraine subjects taking prophylactic medications to migraine subjects not taking prophylactic medications and when comparing migraine subjects to control subjects.

Results

Study Participants

In the CM cohort (n=20), average age was 28 years (SD +/- 5 years), 17 subjects were female, mean headache frequency was 22 headache days per month (SD +/- 7 headache days per month), average number of years with migraine was 10 (SD +/- 6 years), and average number of years with CM was 4 (SD +/- 3 years). Amongst the control subjects (n=20) average age was 28 years (SD +/- 5 years) and 12 subjects were female. Eight CM subjects were taking daily medications that are used for migraine prophylaxis, six of whom were taking doses of medications that typically may be effective for migraine prophylaxis and two subjects were taking doses that would typically be subtherapeutic. Individual subject characteristics are illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics. Five CM subjects had Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores suggestive of borderline or more severe clinical depression (score ≥11). None of the CM subjects had a state anxiety score greater than 1 standard deviation from the normal mean (mean scores in the general population for 19-39 year olds are 36.4 ±10.6), although 6 chronic migraineurs had trait anxiety scores greater than 1 standard deviation from the normal mean (36.4 ±9.6), consistent with trait anxiety.25 Six CM subjects were taking medications at doses that could be considered migraine prophylactic therapies. Two CM subjects were taking medications that are used for migraine prophylaxis but at doses lower than are typically needed for effective migraine treatment. According to scores on the Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS), disability from migraine was severe in 17 subjects (score ≥21), moderate in 2 (score = 11-20), and little to none in 1 (score ≤10).23

| CM Subject |

Age (years) |

Gender | Handed | Headache Frequency (Days/Month) |

Years with Migraine |

Years with CM |

MIDAS | BDI | State Anxiety |

Trait Anxiety |

Prophylactic Medication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | F | Right | 30 | 4 | 4 | 74 | 6 | 33 | 33 | Y (gabapentin 200 mg/day) |

| 2 | 35 | F | Left | 30 | 19 | 5 | 162 | 1 | 20 | 54 | Y |

| 3 | 20 | F | Right | 20 | 4 | 1 | 90 | 0 | 31 | 36 | Y |

| 4 | 21 | F | Right | 20 | 8 | 8 | 28 | 26 | 27 | 50 | Y (pregabalin 50 mg/day) |

| 5 | 28 | M | Right | 30 | 12 | 10 | 16 | 11 | 27 | 48 | Y |

| 6 | 24 | F | Left | 30 | 12 | 2 | 195 | 4 | 46 | 40 | Y |

| 7 | 30 | F | Right | 15 | 3 | 3 | 29 | 7 | 20 | 32 | N |

| 8 | 29 | F | Right | 15 | 9 | 4 | 26 | 8 | 31 | 46 | N |

| 9 | 23 | F | Right | 16 | 14 | 1 | 34 | 7 | 24 | 39 | N |

| 10 | 32 | F | Right | 20 | 20 | 1 | 64 | 17 | 27 | 47 | N |

| 11 | 33 | F | Right | 15 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 36 | 35 | N |

| 12 | 32 | F | Right | 25 | 2 | 2 | 74 | 14 | 33 | 49 | N |

| 13 | 24 | F | Left | 16 | 15 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 28 | 37 | N |

| 14 | 33 | M | Right | 30 | 2 | 1 | 155 | 32 | 46 | 62 | N |

| 15 | 34 | F | Right | 15 | 5 | 2 | 70 | 0 | 28 | 35 | N |

| 16 | 33 | M | Right | 15 | 11 | 4 | 53 | 2 | 32 | 40 | N |

| 17 | 20 | F | Right | 30 | 10 | 3 | 78 | 1 | 34 | 28 | Y |

| 18 | 28 | F | Right | 15 | 18 | 7 | 38 | 4 | 31 | 34 | Y |

| 19 | 29 | F | Right | 15 | 14 | 7 | 22 | 10 | 33 | 41 | N |

| 20 | 23 | F | Right | 30 | 2 | 1 | 45 | 10 | 29 | 28 | N |

Pain Regions are Functionally Connected in Chronic Migraineurs and Controls

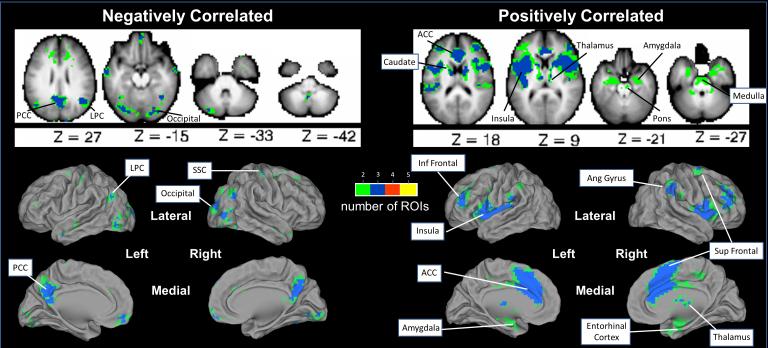

Strong rs-fc (Fisher’s Z-transformed r scores >2.58, p≤0.01) was found among our pain ROIs and between these pain ROIs and other brain regions that participate in sensory-discriminative, affective, cognitive and/or integrative pain processing. Regions positively correlated with ≥2 of 5 a priori selected affective pain ROIs were identified in: anterior insula, middle insula, posterior insula, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, angular gyrus, superior frontal, inferior frontal, anterior cingulate cortex, caudate, thalamus, amygdala, cerebellum, entorhinal cortex, pons, and ventral medulla. (Figure 2) Regions negatively correlated with ≥2 of affective pain ROIs were found in: posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus, lateral parietal cortex, somatosensory cortex, occipital cortex, medial frontal lobes, and cerebellum. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Resting State Functional Connectivity with the 5 Pain ROIs – Summary Analyses.

Voxels with significant rs-fc with at least 2 of 5 a priori selected pain ROIs are illustrated. Axial slices are shown with the left hemisphere on the left side. Green = voxel has rs-fc with 2 of 5 a priori ROIs; Blue = voxel has rs-fc with 3 of 5 a priori ROIs. Red = voxel has rs-fc with 4 of 5 a priori ROIs. Yellow = voxel has rs-fc with 5 of 5 a priori ROIs. PCC = posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus; LPC = lateral parietal cortex; ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; SSC = somatosensory cortex; Inf Frontal = inferior frontal; Sup Frontal = superior frontal; Ang Gyrus = angular gyrus.

Chronic Migraineurs Have Atypical Rs-Fc with Affective Pain Regions

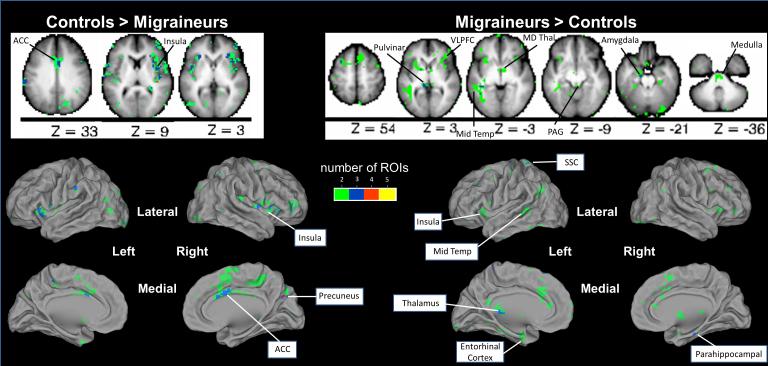

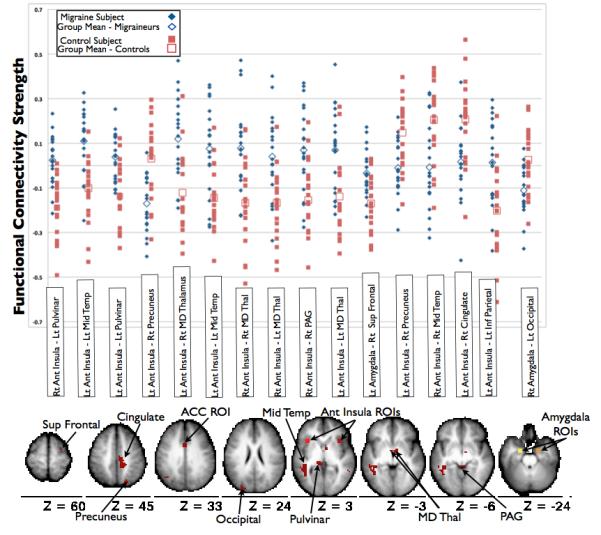

Comparison of CM to controls via summary analyses revealed 92 non-overlapping regions with rs-fc that differed between subject groups. This included regions in the anterior cingulate cortex, anterior insula, middle insula, posterior insula, pulvinar, medial dorsal thalamus, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, amygdala, middle temporal cortex, somatosensory cortex, periaqueductal gray, entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, ventral medulla, and precuneus. (Figure 3) After multiple comparison correction, the strength of 16 functional connections (each including one of our 5 a priori selected pain seeds) differed between CM and controls. These functional connections included anterior insula with regions in pulvinar, middle temporal cortex, mediodorsal thalamus, precuneus, periaqueductal gray, cingulate cortex, and inferior parietal cortex, and amygdala with regions in superior frontal cortex and occipital cortex. (Figure 4)

Figure 3. Resting State Functional Connectivity with Pain Regions Differs in Chronic Migraineurs Compared to Controls.

Summary analyses of 2-sample t-tests for each of the 5 pain ROIs identified voxels with rs-fc that differed between chronic migraineurs and controls. Axial slices are shown with the left hemisphere on the left side. Green = the rs-fc of that voxel with 2 of 5 a priori pain ROIs differs between chronic migraineurs and controls; Blue = the rs-fc of that voxel with 3 of 5 a priori pain ROIs differs between groups; Red = the rs-fc of that voxel with 4 of 5 a priori pain ROIs differs between groups; Yellow = the rs-fc of that voxel with 5 of 5 a priori pain ROIs differs between groups. ACC = anterior cingulate cortex; VLPFC = ventrolateral prefrontal cortex; Mid Temp = middle temporal cortex; MD Thal = medial dorsal thalamus; PAG = periaqueductal gray; SSC = somatosensory cortex.

Figure 4. Resting State Functional Connections to Affective Pain Regions that Significantly Differ Between Chronic Migraineurs and Controls.

After correction for multiple comparisons, the strengths of 16 functional connections significantly differ between chronic migraine and control subjects. The scatterplot illustrates the BOLD time series correlations (functional connectivity strength) on the Y-axis for individual chronic migraine and control subjects. The locations of the regions involved in the functional connections that differed between chronic migraine and control subjects are shown on the axial brain slices (all slices are shown with the left hemisphere on the left side). Rt = right; Lt = left; Ant = anterior; Mid = middle; Temp = temporal; MD = mediodorsal; Thal = thalamus; PAG = periaqueductal gray; Sup = superior; Inf = inferior; ROIs = regions of interest.

There were no voxels that were involved in functional connections that differed between migraineurs and controls and in functional connections that differed in migraine subjects taking prophylactics and migraine subjects not taking prophylactics.

Atypical Rs-Fc Correlates with Number of Years with Chronic Migraine

There were correlations between number of CM years with rs-fc between: left anterior insula and right mediodorsal thalamus (r = .64, p = .002), right anterior insula with right mediodorsal thalamus (r = .45, p = .049), and right anterior insula with right periaqueductal gray (r = .472, p = .036). There were no significant correlations between the strengths of these functional connections and depression scores (per BDI) or anxiety scores (per STAI) in CM subjects, except for a correlation between right anterior insula and periaqueductal gray rs-fc strength with state anxiety scores (r = −.46, p = .042). 22% of the variance in rs-fc between right anterior insula and periaqueductal gray was attributed to CM years while 21% of the variance was attributable to state anxiety.

Discussion

The main study finding is the presence of atypical rs-fc of affective pain regions in interictal CM. Themes emerging from this study include: 1) identification of interictal atypical rs-fc supports the notion that CM has persistent manifestations between migraine attacks; 2) atypical functional connections with affective pain regions involve regions that participate in multiple domains of the pain experience, including sensory-discriminative, cognitive, modulating and integrative domains; 3) atypical rs-fc between affective pain processing regions with middle temporal cortex and with the pulvinar may relate to intolerance to sound and light, two key characteristics of migraine.

Chronic Migraine is Associated with Atypical Interictal Rs-Fc

Although migraine is often considered a chronic disorder with episodic manifestations, there is increasing evidence that migraine has manifestations that persist between attacks (i.e., interictally). Evidence for this argument comes from imaging of the migraine brain, as well as physiological studies.5-7, 48-49 Many of the atypical imaging and physiological findings in migraineurs positively associate with longer disease duration and/or more frequent migraine attacks, suggesting a causal relationship. Furthermore, migraineurs recognize and report interictal migraine manifestations. Interictal visual hypersensitivity to light (photophobia) is reported by ~45% of migraineurs and interictal sound hypersensitivity (phonophobia) by ~75%.6,50 This rs-fc study supports the argument that CM is associated with atypical interictal brain function, specifically atypical rs-fc between affective pain processing regions and regions participating in other aspects of the pain experience. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine if these interictal manifestations are secondary to repeated migraine attacks or if they represent underlying aberrations in the migraineur’s brain that predispose to migraine.

In this study, CM subjects had rs-fc to affective pain regions that differed from control subjects in several ways depending upon the specific functional connection: 1) positive temporal correlation in control and no correlation in CM (e.g. left anterior insula with right precuneus); 2) negative correlation in control and no correlation in CM (e.g. right anterior insula with left pulvinar); 3) negative correlation in control and positive correlation in CM (e.g. left anterior insula with left middle temporal); and 4) negative correlation in CM and no correlation in control (e.g. right amygdala with left occipital). Stronger positive correlations and stronger negative correlations may both be associated with maximal processing efficiency.51 A stronger positive correlation between two regions suggests more frequent coactivation of those two regions. Thus, stronger rs-fc may be observed between two regions of the brain that are activated in response to the same stimulus, such as two regions of the pain matrix in a patient who has experienced frequent pain. A negative correlation between two regions may suggest that those two regions have divergent functions and/or exhibit cross-modal inhibition.16, 52 A negative correlation may represent a “division of labor”, a division that allows a brain region that is responsible for processing a specific stimulus to be activated while a brain region that does not participate in processing that specific stimulus is inhibited.53 As found in this study, negative correlations between pain processing regions and regions of the default mode network (e.g. precuneus, lateral parietal cortex) or between pain regions and occipital cortex regions may be representative of this “division of labor”.

Atypical Rs-Fc in CM Involves Multiple Domains of the Pain Experience

In the present study, atypical rs-fc was identified between four of our affective pain ROIs (right and left anterior insula, right and left amygdala) with other brain regions that participate in different aspects of pain processing. The anterior insula was involved in 14 of 16 functional connections that differed in CM subjects compared to controls. The anterior insula participates predominantly in affective pain processing, a statement supported by several observations: 1) anterior insula is activated when feeling empathy for pain in a loved one, even when no noxious stimulation is being applied to the subject; 2) there is a stronger correlation between anterior insula activity and subjective ratings of thermal pain intensity than there is between anterior insula activity and the actual temperature that is being used for stimulation; and 3) lesioning of the anterior insula results in changes in the emotional dimension of pain with maintenance of pain discrimination, a condition called asymbolia for pain.54-56 When in pain, anterior insula activation is associated with pain relief. Reductions in pain intensity ratings associated with placebo and opioid analgesia coincide with increased activity in the anterior insula.57 However, greater activity in the anterior insula prior to a painful stimulus is a marker of increased susceptibility to pain, predicting increased pain perception to future nociceptive stimuli.58

In this study, CM had atypical rs-fc with right and left amygdala. The amygdala also plays a role in affective aspects of pain. Lesioning of the amygdala results in decreased emotional reactions to pain with no change in baseline nociceptive responses.59 The amygdala likely has anti-nociceptive and pro-nociceptive activity.59-60 Electrical and chemical stimulation of the amygdala can both activate and inhibit periaqueductal gray neurons, brainstem neurons involved predominantly in descending pain inhibition.61 Neugebauer and colleagues theorize that negative emotions such as fear and stress, that are associated with pain reduction, activate amygdala-linked inhibitory control systems, while negative emotions such as depression and anxiety, that are associated with an increase in the pain experience, activate amygdala-linked pain facilitatory pathways.59

Amongst those functional connections that differed between CM and controls, rs-fc of anterior insula with mediodorsal thalamus and anterior insula with periaqueductal gray correlated with number of years that subjects had CM. Correlations with a marker of disease burden (i.e. number of CM years) serve as evidence that these rs-fc differences between CM and controls directly relate to having migraine. Furthermore, the mediodorsal thalamus likely has a role in headache since: 1) it participates in long-term pain memory; 2) it plays a role in sensory-discriminative pain, encoding the intensity of noxious heat; 3) it is involved in striatal and limbic system arousal; and 4) animal studies have identified trigeminal projections to the medial thalamus.62-64 The periaqueductal gray is a key region of the brainstem descending pain modulating system, a system which modulates trigeminal nociceptive transmission. The descending pain modulating system is predominantly pain inhibiting, although it is also capable of pain facilitation.65-68 There is substantial interest in the role of the periaqueductal gray in migraine due to the prior identification of atypical periaqueductal gray structure and atypical periaqueductal gray function in migraineurs.26,48 In this study, CM had atypical rs-fc of anterior insula to periaqueductal gray. Prior structural and functional connectivity studies show that the periaqueductal gray is connected to anterior insula.69-71 Furthermore, prestimulus functional connectivity between the anterior insula and periaqueductal gray determines if a future stimulus is perceived as painful.58 Thus, atypical rs-fc between anterior insula and periaqueductal gray in CM subjects might relate to the enhanced susceptibility to pain that is characteristic of CM. We hypothesize that atypical rs-fc between anterior insula and periaqueductal gray identified in CM could relate to inappropriate control of the PAG via the anterior insula, a “higher order” pain-processing region. Although correlations between rs-fc strength and number of CM years suggest a direct relationship between these two parameters, conclusions cannot be drawn regarding causality or the direction of these potential associations (e.g. greater number of migraine years leads to greater aberrations in rs-fc vs. more atypical rs-fc leads to earlier onset or longer duration of migraine). Longitudinal studies are needed to draw strict conclusions.

Identification of atypical rs-fc in CM involving brain regions participating in multiple aspects of the pain experience is consistent with expectations based upon knowledge of the migraine phenotype. CM is a disorder with wide-ranging effects due to frequent pain, negative effects on mood, and impairment of cognition. Chronic migraineurs suffer from frequent pain due to headaches (the typical chronic migraineur has 22 headache days/month), central sensitization, and co-morbid pain disorders such as fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome.72-74 Migraineurs have lower interictal pain thresholds than controls, suggestive of abnormal sensory-discriminative processing, and lower pain tolerance thresholds suggestive of abnormal affective responses to pain.5,75 CM also has deleterious effects on mood and cognitive abilities. Irritability, depression, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, and impairments in executive function are common during and between migraine attacks.76-77 Consistent with the wide-ranging phenotypic expression of migraine, the findings of this rs-fc study suggest that migraine involves numerous aspects of the pain experience, including affective, sensory-discriminative, and cognitive domains.

Atypical Rs-Fc Could Relate to Key Migraine Characteristics

Atypical rs-fc between anterior insula and pulvinar might relate to migraine intolerance to light, the abnormal perception of visual stimuli as painful, and/or visual salience.78 Since the pulvinar receives inputs from dura-sensitive spinal trigeminal nucleus neurons and from the optic nerves, it is postulated that the pulvinar participates in integration of visual stimuli with trigeminal nerve mediated head pain.23, 79-80 Pulvinar-mediated integration may help to explain why: 1) 40% of migraineurs have light-triggered migraines; 2) >90% of migraineurs have light hypersensitivity (photophobia) during attacks; 3) headache intensity and photophobia intensity are positively correlated; 4) exposing interictal migraineurs to bright light leads to reduced pain thresholds in trigeminal innervated locations, an effect not detected in controls; 5) painful forehead stimulation in interictal migraineurs, but not controls, leads to decreased visual discomfort thresholds; 6) compared to controls and migraineurs without allodynia, migraineurs with interictal allodynia have altered cortical visual processing.81-84

Atypical rs-fc of the anterior insula with middle temporal cortex could relate to migraine intolerance to auditory stimuli and to migraineurs misperception of normally non-painful auditory stimuli as painful.7 Auditory stimuli interact with migraine in several ways: 1) 50%-75% of migraineurs have noise-triggered migraines; 2) >90% of migraineurs have sound hypersensitivity (phonophobia) during migraine attacks; 3) headache intensity positively correlates with phonophobia intensity; 4) interictal sound hypersensitivity is reported by ~75% of migraineurs; 5) sound aversion thresholds are lower in interictal migraineurs compared to controls.6-7, 50, 85

Future studies will explore relationships between quantitative measures of light and sound hypersensitivity with functional connectivity strength between affective pain regions with pulvinar and affective pain regions with middle temporal cortex.

Study Limitations

Since there are no identified brain regions that are solely responsible for pain processing, each of the “pain regions” in this study also serves non-pain functions. Thus, we cannot be certain that the rs-fc differences in this study are attributable to having CM. However, correlations between number of years with CM and atypical rs-fc are highly suggestive that our findings relate to the presence of CM. Since we did not have a cohort of episodic migraine subjects in this study, it is unclear if our findings are specific for CM or are applicable to episodic and CM. Migraine and control groups were not gender matched, potentially introducing a source of bias.86 Also, subjects were not matched according to measures of anxiety and depression, conditions that may affect rs-fc between pain regions. Considering the 3 functional connections differing between CM and controls that also correlated with number of CM years, only one (anterior insula with PAG) also correlated with state anxiety scores. Eight CM subjects were using daily medications considered migraine prophylactic therapies (six at doses considered sufficient for migraine prophylaxis). To explore the possibility that the use of these medications was driving our results, we performed post-hoc analyses comparing rs-fc to the 5 pain ROIs in migraineurs taking prophylactic medications to migraineurs not taking prophylactic medications. There was no anatomic overlap between regions involved in the functional connections that differed between migraineurs and controls and regions involved in functional connections that differed in migraineurs taking prophylactics and those not taking prophylactics. Thus, use of migraine prophylactic medications by a proportion of the migraineurs likely had little impact on our results reported herein. Also, CM subjects had a relatively short duration of CM (about 4 years). A longer duration of CM may be associated with more atypical rs-fc of pain regions.

Conclusions

CM is associated with interictal atypical rs-fc of affective pain regions with regions participating in sensory-discriminative, cognitive, and integrative pain functions. Correlations between years with CM and the strength of some of these atypical functional connections suggest a causal relationship, although the direction of this relationship is uncertain. Atypical rs-fc of affective pain regions might relate to the abnormal affective processing of potentially painful stimuli and atypical affective responses to painful stimuli that are characteristic of CM. Studies comparing episodic migraine and CM and longitudinal studies are needed to determine if atypical rs-fc is a result of having CM or if atypical rs-fc predisposes the individual to developing CM.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by the National Headache Foundation [to TJS]; the National Institutes of Health [K23NS070891 to TJS, KL2RR024994 to TJS, UL1RR024992 to Washington University]; and American Roentgen Ray Scholar Award [to TB].

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646–657. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Terwindt GM, Ferrari MD, Tijhuis M, et al. The impact of migraine on quality of life in the general population: the GEM study. Neurology. 2000;55:624–629. doi: 10.1212/wnl.55.5.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castillo J, Munoz P, Guitera V, Pascual J. Kaplan Award 1998. Epidemiology of chronic daily headache in the general population. Headache. 1999;39:190–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1999.3903190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demarquay G, Royet JP, Giraud P, Chazot G, Valade D, Ryvlin P. Rating of olfactory judgements in migraine patients. Cephalalgia. 2006;26:1123–1130. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwedt TJ, Krauss MJ, Frey K, Gereau RW. Episodic and chronic migraineurs are hypersensitive to thermal stimuli between migraine attacks. Cephalalgia. 2011;31:6–12. doi: 10.1177/0333102410365108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Main A, Dowson A, Gross M. Photophobia and phonophobia in migraineurs between attacks. Headache. 1997;37:492–495. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.1997.3708492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashkenazi A, Mushtaq A, Yang I, Oshinsky ML. Ictal and interictal phonophobia in migraine-a quantitative controlled study. Cephalalgia. 2009;29:1042–1048. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peyron R, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta-analysis (2000) Neurophysiol Clin. 2000;30:263–288. doi: 10.1016/s0987-7053(00)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlsson K, Andersson J, Petrovic P, et al. Predictability modulates the affective and sensory-discriminative neural processing of pain. Neuroimage. 2006;32:1804–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price DD. Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science. 2000;288:1769–1772. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berthier M, Starkstein S, Leiguarda R. Asymbolia for pain: a sensory-limbic disconnection syndrome. Annals of Neurology. 1988;24:41–49. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Starr CJ, Sawaki L, Wittenberg GF, Burdette JH, Oshiro Y, Quevedo AS, Coghill RC. Roles of the insular cortex in the modulation of pain: insights from brain lesions. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29:2684–2694. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5173-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maleki N, Linnman C, Brawn J, Burstein R, Becerra L, Borsook D. Her versus his migraine: multiple sex differences in brain function and structure. Brain. 2012;135:2546–2559. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maleki N, Becerra L, Brawn J, McEwen B, Burstein R, Borsook D. Common hippocampal structural and functional changes in migraine. Brain Struct Funct. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00429-012-0437-y. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maleki N, Becerra L, Brawn J, Bigal M, Burstein R, Borsook D. Concurrent functional and structural cortical alterations in migraine. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:607–620. doi: 10.1177/0333102412445622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9673–9678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shehzad Z, Kelly AM, Reiss PT, et al. The Resting Brain: Unconstrained yet Reliable. Cereb Cortex. 2009 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fair DA, Cohen AL, Power JD, et al. Functional brain networks develop from a “local to distributed” organization. PLoS Comput Biol. 2009;5:e1000381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fair DA, Dosenbach NU, Church JA, et al. Development of distinct control networks through segregation and integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13507–13512. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705843104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Goekoop R, et al. Altered resting state networks in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;26:231–239. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depression: abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:429–437. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moulton EA, Becerra L, Maleki N, et al. Painful heat reveals hyperexcitability of the temporal pole in interictal and ictal migraine states. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:435–438. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jin C, Yuan K, Zhao L, et al. Structural and functional abnormalities in migraine patients without aura. NMR Biomed. 2013;26:58–64. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yuan K, Qin W, Liu P, et al. Reduced fractional anisotropy of corpus callosum modulates interhemispheric resting state functional connectivity in migraine patients without aura. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mainero C, Boshyan J, Hadjikhani N. Altered functional magnetic resonance imaging resting-state connectivity in periaqeuductal gray networks in migraine. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:838–845. doi: 10.1002/ana.22537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russo A, Tessitore A, Giordano A, et al. Executive resting-state network connectivity in migraine without aura. Cephalalgia. 2012;32:1041–1048. doi: 10.1177/0333102412457089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue T, Yuan K, Zhao L, et al. Intrinsic brain network abnormalities in migraines without aura revealed in resting-state fMRI. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52927. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Classification of Headache Disorders Committee International classification of headache disorders II. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):1–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, et al. Validity of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain. 2000;88:41–52. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moran PJ, Mohr DC. The validity of Beck Depression Inventory and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression items in the assessment of depression among patients with multiple sclerosis. J Behav Med. 2005;28:35–41. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-2561-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults. Mind Garden, Inc.; 1983. pp. 1–76.pp. 22 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vogel AC, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. The left occipitotemporal cortex does not show preferential activity for words. Cerebral Cortex. 2012;22:2715–2732. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron. 2011;72:665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown TT, Lugar HM, Coalson RS, Miezin FM, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Developmental changes in human cerebral functional organization for word generation. Cerebral Cortex. 2005;15:275–290. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miezin FM, Maccotta L, Ollinger JM, et al. Characterizing the hemodynamic response: effects of presentation rate, sampling procedure, and the possibility of ordering brain activity based on relative timing. Neuroimage. 2000;11:735–759. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlaggar BL, Brown TT, Lugar HM, Visscher KM, Miezin FM, Petersen SE. Functional neuroanatomical differences between adults and school-age children in the processing of single words. Science. 2002;296:1476–1479. doi: 10.1126/science.1069464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lancaster JL, Glass TG, Lankipalli BR, et al. A modality-independent approach to spatial normalization of tomographic images of the human brain. Human Brain Mapping. 1995;3:209–223. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder AZ. Difference image versus ratio image error function forms in PET-PET realignment. In: Myer R, Cunningham VJ, Bailey DL, Jones T, editors. Quantification of Brain Function Using PET. Academic Press; San Diego, Ca: 1996. pp. 131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fox MD, Zhang D, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME. The global signal and observed anticorrelated resting state brain networks. JN Physiol. 2009;101:3270–3283. doi: 10.1152/jn.90777.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powers J, Barnes K, Snyder A, Schlaggar B, Petersen S. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2142–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schweinhardt P, Glynn C, Brooks J, et al. An fMRI study of cerebral processing of brush-evoked allodynia in neuropathic pain patients. Neuroimage. 2006;32:256–265. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Farrell MJ, Laird AR, Egan GF. Brain activity associated with painfully hot stimuli applied to the upper limb: a meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping. 2005;25:129–139. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saarela MU, Hlushchuk Y, de C. Williams AC, et al. The compassionate brain: humans detect intensity of pain from another’s face. Cerebral Cortex. 2007;17:230–237. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Henderson LA, Gandevia SC, Macefield VG. Somatotopic organization of the processing of muscle and cutaneous pain in the left and right insula cortex: a single-trial fMRI study. Pain. 2007;128:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He BJ, Snyder AZ, Cinvent JL, et al. Breakdown of functional connectivity in frontoparietal networks underlies behavioral deficits in spatial neglect. Neuron. 2007;53:905–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krain Roy A, Shehzad Z, Margulies DS, et al. Functional connectivity of the human amygdala using resting state fMRI. Neuroimage. 2009;45:614–626. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Welch KM, Nagesh V, Aurora SK, Gelman N. Periaqueductal gray matter dysfunction in migraine: cause or the burden of illness? Headache. 2001;41:629–637. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim JH, Suh SI, Seol HY, et al. Regional grey matter changes in patients with migraine: a voxel-based morphometry study. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vingen JV, Pareja JA, Storen O, et al. Phonophobia in migraine. Cephalalgia. 1998;18:243–249. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1998.1805243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kilpatrick LA, Suyenobu BY, Smith SR, et al. Impact of mindfulness-based stress reduction training on intrinsic brain connectivity. Neuroimage. 2011;56:290–298. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uddin LQ, Kelly AMC, Biswal BB, et al. Functional connectivityof default mode network components: correlation, anticorrelation, and causality. Human Brain Mapping. 2009;30:625–637. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fransson P. How default is the default mode of brain function? Further evidence from intrinsic BOLD signal fluctuations. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:2836–2845. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singer T, Seymour B, O’Doherty J, Kaube H, Dolan RJ, Frith CD. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303:1157–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.1093535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655–666. doi: 10.1038/nrn894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berthier M, Starkstein S, Leiguarda R. Asymbolia for pain: a sensory-limbic disconnection syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1988;24:41–49. doi: 10.1002/ana.410240109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petrovik P, Kalso E, Petersson KM, Ingvar M. Placebo and opioid analgesia – imaging a shared neuronal network. Science. 2002;295:1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.1067176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ploner M, Lee MC, Wiech K, Bingel U, Tracey I. Prestimulus functional connectivity determines pain perception in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:355–360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906186106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neugebauer V, Li W, Bird GC, Han JS. The amygdala and persistent pain. Neuroscientist. 2004;10:221–234. doi: 10.1177/1073858403261077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. Negative affect: effects on an evaluative measure of human pain. Pain. 2003;104:617–626. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.da Costa Gomez TM, Behbehani MM. An electrophysiological characterization of the projection from the central nucleus of the amygdala to the periaqueductal gray of the rat: the role of opioid receptors. Brain Res. 1995;689:21–31. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00525-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Craig AD, Burton H. Spinal and medullary lamina 1 projection to nucleus submedius in medial thalamus: a possible pain center. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1981;45:443–466. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.45.3.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chai SC, Kung JC, Shyu BC. Roles of the anterior cingulated cortex and medial thalamus in short-term and long-term aversive information processing. Mol Pain. 2010;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bushnell MC, Duncan GH. Sensory and affective aspects of pain perception: is medial thalamus restricted to emotional issues? Exp Brain Res. 1989;78:415–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00228914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bingel U, Tracey I. Imaging CNS modulation of pain in humans. Physiology. 2008;23:371–380. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00024.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fields HL, Bry J, Hentall I, Zorman G. The activity of neurons in the rostral ventral medulla of the rat during withdrawal from noxious heat. Journal of Neuroscience. 1983;3:2545–2552. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-12-02545.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haws CM, Williamson AM, Fields HL. Putative nociceptive modulatory neurons in the dorsolateral pontomesencephalic reticular formation. Brain Research. 1989;483:272–282. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zambreanu L, Wise RG, Brooks JCW, et al. A role for the brainstem in central sensitisation in humans. Evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Pain. 2005;114:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Linnman C, Moulton EA, Barmettler G, Becerra L, Borsook D. Neuroimaging of the periaqueductal gray: state of the field. Neuroimage. 2012;60:505–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kong J, Tu PC, Zyloney C, Su TP. Intrinsic functional connectivity of the periaqueductal gray, a resting fMRI study. Behav Brain Res. 2010;211:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jasmin L, Burkey AR, Granato A, Ohara PT. Rostral agranular insular cortex and pain areas of the central nervous system: a tract-tracing study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:425–440. doi: 10.1002/cne.10978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peres MF. Fibromyalgia, fatigue, and headache disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2003;3:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s11910-003-0059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Aamodt AH, Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Zwart JA. Comorbidity of headache and gastrointestinal complaints. The Head-HUNT Study. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:144–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Woodrow KM, Friedman GD, Siegelaub AB, Collen MF. Pain tolerance: differences according to age, sex and race. Psychom Med. 1972;34:548–556. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Baskin SM, Smitherman TA. Migraine and psychiatric disorders: comorbidities, mechanisms, and clinical applications. Neurol Sci. 2009;30 Suppl 1:S61–65. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schmitz N, Arkink EB, Mulder M, et al. Frontal lobe structure and executive function in migraine patients. Neurosci Lett. 2008;440:92–96. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robinson DL, Petersen SE. The pulvinar and visual salience. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:127–132. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90354-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Maleki N, Becerra L, Upadhyay J, et al. Direct optic nerve pulvinar connections defined by diffusion MR tractography in humans: Implications for photophobia. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011 doi: 10.1002/hbm.21194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Noseda R, Kainz V, Jakubowski M, et al. A neural mechanism for exacerbation of headache by light. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:239–245. doi: 10.1038/nn.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Drummond PD, Woodhouse A. Painful stimulation of the forehead increases photophobia in migraine sufferers. Cephalalgia. 1993;13:321–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1993.1305321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kowacs PA, Piovesan EJ, Werneck LC, et al. Influence of intense light stimulation on trigeminal and cervical pain perception thresholds. Cephalalgia. 2001;21:184–188. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Vincent AJ, Spierings EL, Messinger HB. A controlled study of visual symptoms and eye strain factors in chronic headache. Headache. 1989;29:523–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1989.hed2908523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shibata K, Yamane K, Iwata M. Change of excitability in brainstem and cortical visual processing in migraine exhibiting allodynia. Headache. 2006;46:1535–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Martin PR, Reece J, Forsyth M. Noise as a trigger for headaches: relationship between exposure and sensitivity. Headache. 2006;46:962–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Filippi M, Valsasina P, Misci P, et al. The organization of intrinsic brain activity differs between genders: a resting-state fMRI study in a large cohort of young healthy subjects. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hbm.21514. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]