Abstract

The development of new therapeutics for the treatment of neurodegenerative pathophysiologies currently stands at a crossroads. This presents an opportunity to transition future drug discovery efforts to target disease modification, an area in which much still remains unknown. In this Perspective we examine recent progress in the areas of neurodegenerative drug discovery, focusing on some of the most common targets and mechanisms; N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors, voltage gated calcium channels (VGCCs), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species, and protein aggregation. These represent the key players identified in neurodegeneration and are part of a complex, intertwined signaling cascade. The synergistic delivery of two or more compounds directed against these targets, along with the design of small molecules with multiple modes of action should be explored in pursuit of more effective clinical treatments for neurodegenerative diseases.

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative disease is an encompassing term for a set of over 600 diseases in which the nervous system progressively and irreversibly deteriorates. The single greatest risk factor for the development of neurodegenerative disease is advancing age, with associated mitochondrial DNA mutation and oxidative stress damage,1 illustrated by the fact that the majority of these diseases are late-onset. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), the most prevalent of the neurodegenerative diseases, affects approximately 15 million people worldwide. Estimates expect the number of sufferers to triple in the USA2 and Europe3 by 2050, figures that are repeated for most other forms of neurodegeneration, including Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Huntington’s disease (HD).

The most common forms of neurodegenerative diseases are AD, PD, HD, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), (or in Europe, motor neurone disease, MND).4 Specific aspects of these diseases, including protein aggregation, genetic mutations, and pathophysiology, are discussed in this Perspective. Extensive literature exists detailing each of the pathways highlighted, as well as for the many other neurodegenerative diseases. The interested reader is directed to those excellent reviews and references cited within this manuscript.

A commonality of the neurodegenerative diseases is that they are not diseases attributed to a single gene or even multiple genes; they are far more complicated, involving a myriad of known and unknown signaling cascades, misfolded proteins, protofibril formation, ubiquitin-proteasome dysfunction, oxidative and nitrosative stress, mitrochondrial injury, and many more events.5 Our current understanding of neuroscience has enabled the identification of some key genes involved, but since many cases are seemingly sporadic, we know that mechanisms of neurodegeneration are more than just genetic.6 While they vary in symptoms, neurodegenerative diseases have many pathologic overlaps (Figure 1). In this Perspective, we focus on the major components of this shared pathway: N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors, voltage gated calcium channels (VGCCs), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species (ROS), and protein aggregation.

Figure 1.

Common targets and mechanisms associated with many neurodegenerative diseases that are highlighted in this Perspective.

NMDA receptors are ligand-gated, voltage-dependent ion channels that respond to the neurotransmitters glutamate and NMDA. NMDA receptor activation leads to Ca2+ influx into post-synaptic cells, which continues signal potentiation by activating signaling cascades. Over-stimulation of NMDA receptors has been implicated in neurodegeneration, in addition to other disease states, and therefore NMDA receptors have been greatly investigated as a drug target (Section 2). Ca2+ influx is also regulated by VGCCs. As discussed in Section 3, one specific channel, Cav1.3, has been identified to play a role in the progression of PD and therefore selective antagonism of Cav1.3 is hypothesized to be potentially neuroprotective in early or presymptomatic stages of PD. Among many other responses, increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration activates nNOS. Overactivation of nNOS produces high intracellular levels of nitrite and superoxide, which react to form ROS including peroxynitrite. This oxidative stress within the cell causes damage to DNA, lipids, and causes protein modifications. Overactivation of nNOS has also been implicated in neurodegeneration and therefore inhibitors of nNOS are sought-after as potential therapeutics (Section 4). Additionally antioxidant therapeutics are designed to directly prevent cellular damage from oxidative species (Section 5). Lastly, protein aggregation is a hallmark of AD and PD, and while it may result from modifications by ROS, other mechanisms, such as mutations, are thought to be involved in protein aggregates observed in AD and PD. Progress towards developing anti-aggregation therapeutics is examined in Section 6.

A separate, but crucially important, pathophysiological pathway that contributes to neurodegeneration is inflammation and immune response.7, 8 Many of the most relevant immunological molecules are produced within the brain, and this leads to the observation that systemic immune responses affect brain function and contribute to neurodegeneration.9 This pathway of inflammation and immune response is intricately connected with several, if not all, of the individual targets discussed in this Perspective. Space does not permit an all-encompassing review of this subject, and the reader is directed to the excellent review articles referenced herein. Expanding research continues to link this key pathophysiological pathway to the individual targets discussed in this Perspective as briefly highlighted below.

Highly regulated by the immune system, the kynurenine pathway is an enzymatic cascade that converts tryptophan to serotonin but also to several other neuroactive compounds. Misregulation of this pathway results in increased or decreased production of these metabolites and contributes to a neurodegenerative effect.10 Kynurenic acid is a competitive antagonist for the NMDA, kainite, and AMPA receptors and forms the structural scaffold for drug discovery efforts mentioned in Section 2. Independent of the antagonistic effect of kynurenic acid is the observation that it is an effective free radical scavenger and can therefore display antioxidant properties similar to compounds discussed in Section 5.11

Further connections from inflammation and immune response to antioxidants and nNOS inhibitors exist via a family of proteins known as toll-like receptors (TLRs). Evidence is increasing for the role of TLRs in sterile inflammation observed in neurodegenerative diseases, such as PD and AD.12 These receptors play an important role in innate immunity because they recognize conserved motifs found in microorganisms. They are expressed in large numbers in various cells within the central nervous system (CNS) and serve to activate microglia. Microglia, the immune cells of the brain, are activated by distress signals from nearby cells. A side effect of this activation is the release of toxic factors, such as nitric oxide (Section 4) and ROS (Section 5), resulting in increased neuronal damage. TLRs are also being explored as targets for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.13 Furthermore, polyphenols, discussed in Section 5, acting predominantly as antioxidants, also have activity crossover to the inflammation and inflammatory response; these compounds are known to modulate neuroinflammation by inhibiting the expression of inflammatory genes and the level of intracellular antioxidants.14 Neuroinflammation commonly occurs as a result of oxidative and excitotoxic damage to neurons, and because of mitochondrial dysfunction and is linked to protein aggregation.15 It is therefore envisioned that drugs that combat neuroinflammation might also combat neurodegenerative disease progression.

However, while anti-inflammatory agents may be required to treat neurodegenerative diseases, they may not be sufficient on their own but may be effective as part of a combination therapy.16 Such a combination might include targeting pro-inflammatory factors, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha and Fas ligand. One compound, revlimid, has been reported to modestly reduce these proinflammatory cytokines and show some neuroprotection in an ALS mouse model.17 Use of revlimid in a combinatorial approach with selected antiaggregation agents discussed in Section 6 or potentially any of the agents in this Perspective may increase the neuroprotective effects from ‘modest’ results with a single therapeutic compound to ‘significant’ results with a combination of two or more compounds.

The thesis that AD, PD, HD, and ALS, although distinct disorders, share a common mechanism that progresses neuron death along a ‘neurodegenerative spectrum’ has been advanced by numerous researchers.18, 19

Recent advances have increased our understanding of the processes underlying neurodegeneration.20-23 Drug candidates that target single or dual processes have been advanced to the clinic, but they only provide relief of symptoms, not of the underlying causes (which still remain unknown). Modulation of multiple targets along the same biological pathway could potentially lead to disease modification rather than just control of symptoms. The widely accepted definition of a disease modifying drug is ‘an agent that alters the underlying pathophysiology of the disease in question and demonstrates meaningful reduction in the rate of decline or progression to a defined milestone.’24 In a complex pathway with many drug targets, such as those contributing to neurodegenerative diseases, a drug with a single-target mechanism of action cannot always correct that pathway. The synergistic delivery of a ‘cocktail’ of two or more drugs may deliver enhanced potency in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases by potentially leading to disease modification.

Polypharmacy, the synergistic combination of two or more drugs acting on different targets, has been successful in treating other diseases, such as hyperlipidemia (high blood cholesterol). The combination of simvastatin (a 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitor) and ezetimibe (an inhibitor of dietary cholesterol uptake) is marketed as Vytorin®.25 This combination therapy works by preventing the body from making its own cholesterol while also inhibiting the absorption of cholesterol from dietary intake. A drug that inhibits only one source of cholesterol is less effective at lowering overall levels, as cholesterol is still produced by the second source. This disease-modifying therapy reduces overall cholesterol levels by targeting both sources. Other disease-modifying synergistic drug combinations have been utilized for the treatment of cancer26, hepatitis C virus,27 and HIV/AIDS.28 supporting the potential strategy of treating other complex diseases in a similar manner.

Alternatively, a single therapeutic agent could be designed to interact at two different targets. An example of a dual-acting drug that is disease-modifying is duloxetine (Cymbalta®), used in the treatment of depression. This compound inhibits both serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake in the CNS.29 Inhibition of the reuptake of both neurotransmitters increases overall levels of the two compounds, known to play an important role in mood. A deficit in either neurotransmitter can cause depression; therefore, increasing levels of both provides a disease-modifying therapy to counteract this deficit.30 An example relevant to the disease pathway outlined in Figure 1 is the polycyclic caged amine compound NGP1-01 (18) (Section 2), which blocks both the NMDA receptor and L-type calcium channel with resulting neuroprotective effects. Blocking only one of these targets allows the continued influx of Ca2+ ions from the other. As excess Ca2+ ion concentration is implicated in excitotoxicity, this would be analogous to trying to stop a bucket leaking from two holes by only stoppering one. Preventing an increase in overall Ca2+ ion concentration, and thereby excitotoxicity, could be considered disease-modifying over simply reducing the concentration.

Additionally, a multi-faceted strategy would further probe the pathophysiological pathway(s) of neurodegeneration and confirm the intricate connectivity that has been proposed between therapeutic targets. Therapeutics developed for one type of neurodegenerative disease, when delivered in combination, may transfer their therapeutic potential to a different disease state, thereby exploiting and expanding the neurodegenerative therapeutic arsenal. Such combination therapy would also have advantages in drug delivery and dosing. Delivery of a significant dose of an inhibitor of Cav1.3-type calcium channels is hindered by concerns of selectivity over other Cav channels and resultant off-target toxicity. Dosing a lower concentration of such an inhibitor in conjunction with a modulator of another target on the pathophysiological pathway would allow for the inhibition of two targets that alone may provide no therapeutic response. This approach would provide the opportunity to use drugs that are active but only have low efficacy because of selectivity problems. As a result, the potential to tune inhibitory responses rather than outright blockage would allow for the use of small molecules previously discarded as non-efficacious.

This Perspective examines the state-of-the-art small molecule therapeutics available for each of the neurodegenerative disease targets depicted in Figure 1. A combination of these molecules or the design of new compounds bearing active moieties that target two or more of the pathophysiological hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases might be expected to bring about a new era in neuroscience drug discovery while efforts continue toward further elucidation of the underlying causes of neurodegeneration.

2. Alteration of NMDA Receptor Function

NMDA receptors, named after their selective agonist, N–methyl–d–aspartate, are ionotropic receptors that mediate glutamatergic neurotransmission. These receptors, as well as α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors, kainate cation channel receptors, and metabotropic receptors, respond to glutamate, the major excitatory transmitter in the brain.31, 32 The NMDA receptors have long been studied as potential therapeutic targets because of the numerous CNS functions in which they have been implicated, both in normal physiological function and in disease states.32, 33 However, the numerous roles they play in normal neurological function have led to disappointing clinical outcomes in the development of new drugs as a result of adverse side effects.32, 34 Another complicating factor for the lack of successful therapeutic intervention through modification of NMDA receptor function lies in the permeability of Ca2+ through the channel; excessive ion influx results in excitotoxicity that can lead to neuronal cell death.35, 36

The NMDA receptor has a relatively complex tetrameric subunit organization, and the subunit combination varies in different regions of the brain. This subunit heterogeneity presents additional challenges in drug design since each subunit has distinct functional and pharmacological properties. Seven NMDA receptor subunits have been identified: a GluN1 subunit, four different GluN2 subunits (GluN2 A-D), and two GluN3 subunits (GluN3A,B). The intact receptor consists of two GluN1 subunits and two GluN2 subunits. Glutamate binds to the GluN2 subunit, but for the receptor to be functional, glycine must simultaneously bind to the GluN1 subunit as a co-agonist.37 However, studies involving the CA1 region of rat hippocampus tissue slices have shown that synaptic NMDA receptors, which are important in long-term potentiation and NMDA-induced neurotoxicity, utilize d-serine as co-agonist, whereas extrasynaptic NMDA receptors have a preferential affinity for glycine.38 The intracellular portion of the transmembrane domains connect to a post-synaptic signaling complex known as the postsynaptic density, which contains PSD-95, enzymes such as nNOS or kinases, and other signaling and scaffolding proteins (Figure 2). 39, 40 Excitotoxicity, including the excessive stimulation of NMDA receptors, has long been hypothesized to play a role in the etiology of neurodegenerative disorders, such as PD41 and HD,42, 43 and may contribute, at least in part, to neuronal loss in AD44 and other dementias, ALS,36, 45-47 and possibly multiple sclerosis and prion disease.48

Figure 2.

NMDA receptor showing agonist and antagonist binding site domains

Earlier work on NMDA receptor antagonists has focused on designing compounds targeting four regions of the receptor: the glutamate and the glycine agonist binding domain (ABD) sites, the channel pore, and the N-terminal domain (NTD) region between GluN1 and GluN-B.49 Among the earliest glutamate competitive antagonists to be developed was phosphonic acid (R)-AP5 (1), which showed strong selectivity for NMDA receptors over kainate and AMPA receptors.50, 51 The introduction of rigidity with a piperazine ring provided another phosphonic glutamate site antagonist (2), which relieved parkinsonian symptoms and improved locomotion in animal models of PD when co-administered with l-DOPA, although it was not effective when given alone.52 A drawback of the phosphonic acid class of antagonists is that their polarity makes passage

through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and intestinal membranes difficult.53 Another problem with these competitive antagonists is that they generally demonstrate poor subunit selectivity.31 The differences in potency between NMDA and glutamate between the different GluN2 subtypes is less than 4-fold, and an analysis of key residues in the binding pocket shows the presence of a highly conserved binding site.54 Glycine site competitive antagonist 7-chlorokynurenate (3) did prevent NMDA-induced striatal lesions in an animal model as well as in vitro, but the compound targeted kainite receptors as well as NMDA receptors. In addition, the protection afforded by the compound could not be surmounted by co-administration of glycine, but instead by increasing the dose of NMDA, calling into question its actual mechanism of action.55 Since glycine acts at all NMDA subtypes, there may be an issue of tolerability of compounds targeting the glycine binding site, in addition to the higher doses of either glutamate or glycine antagonists that would be needed to surmount the competition with the endogenous ligands for their respective binding sites.39 However, since glycine antagonists act at the GluN1 subunit, they may be associated with fewer side effects, although in the case of 7-chlorokynurenate (3), there has been the added issue of poor BBB penetration.53, 54 A series of 3-amino-1-hydroxypyrrolidin-2-one (HA-966, 4) analogues were synthesized to overcome the limitations of poor solubility and BBB penetration.53

through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and intestinal membranes difficult.53 Another problem with these competitive antagonists is that they generally demonstrate poor subunit selectivity.31 The differences in potency between NMDA and glutamate between the different GluN2 subtypes is less than 4-fold, and an analysis of key residues in the binding pocket shows the presence of a highly conserved binding site.54 Glycine site competitive antagonist 7-chlorokynurenate (3) did prevent NMDA-induced striatal lesions in an animal model as well as in vitro, but the compound targeted kainite receptors as well as NMDA receptors. In addition, the protection afforded by the compound could not be surmounted by co-administration of glycine, but instead by increasing the dose of NMDA, calling into question its actual mechanism of action.55 Since glycine acts at all NMDA subtypes, there may be an issue of tolerability of compounds targeting the glycine binding site, in addition to the higher doses of either glutamate or glycine antagonists that would be needed to surmount the competition with the endogenous ligands for their respective binding sites.39 However, since glycine antagonists act at the GluN1 subunit, they may be associated with fewer side effects, although in the case of 7-chlorokynurenate (3), there has been the added issue of poor BBB penetration.53, 54 A series of 3-amino-1-hydroxypyrrolidin-2-one (HA-966, 4) analogues were synthesized to overcome the limitations of poor solubility and BBB penetration.53

NMDA channel pore blockers, in particular amantadine (5) and its derivative memantine (6), have been developed for therapeutic use in inhibiting excitotoxicity. One of the earlier NMDA pore blockers to be advanced was dizocilpine (7), a high-affinity, uncompetitive antagonist.56 Co-administration of dizocilpine with l-DOPA completely prevented the progressive reduction in the duration of the l-DOPA response occurring with chronic l-DOPA therapy in parkinsonian rats.57 However, use of dizocilpine has been associated with severe side effects, such as coma,58 and in one study, actually exacerbated the symptoms of MPTP-induced parkinsonism when administered to a monkey.59

Amantadine (5) is an FDA approved drug that has been widely used in the treatment of PD. The predominant inhibitory mechanism of action of amantadine results from increasing the rate of channel closed states when the drug is bound in the channel of NMDA receptors.60 In a retrospective study of PD patients attending a single clinic, improved survival was associated with amantadine use.61 Amantadine, as well as the NMDA channel pore blocker dextromethorphan (8), also improved l-DOPA-associated motor response complications when given as an adjuvant to l-DOPA therapy.62, 63 However, a systematic Cochrane review of randomized controlled trials for amantadine concluded that because of a lack of evidence, it was not possible to determine whether amantadine is a safe and effective treatment for l-DOPA-induced dyskinesias in PD patients. The report also noted that in one study, 8 out of 18 participants had side effects, including confusion and worsening of hallucinations.64 In an unrelated study, NMDA channel blocker remacemide (9), as adjunct therapy with l-DOPA, was not found to significantly improve motor fluctuation symptoms, although the compound was found to be safe and tolerable.65

Memantine (6), another NMDA antagonist, is classified as an uncompetitive, open-channel blocker. The drug was patented by Eli Lilly & Co. in 1968 and was marketed by the German pharmaceutical company Merz to treat PD. The drug has a relatively fast off-rate from channel binding, which contributes to the drug’s low affinity for the channel pore, and, as a result, its clinical efficacy and tolerability. As a result, after several clinical trials, memantine was approved by the European Union in 2002 and the FDA in 2003 for the treatment of moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease.66 One analysis concluded that the safety profile of memantine makes it particularly suitable for its use in elderly patients, since it is associated with a low overall rate of adverse events and a low potential for drug-drug interactions (because of a low extent of metabolism and protein binding, particularly to cytochrome P450 enzymes).67 A recent review adds that for the treatment of moderate to severe AD, memantine should be offered as either a monotherapy or in conjunction with an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, but that the use of memantine as a first-line therapy for mild to moderate AD is not supported by current data. Further, insufficient data exist to make a recommendation for its use in PD dementia.68 A paradoxical feature of the action of memantine is that a higher concentration of memantine is needed to alleviate mild dementia than to counteract the damage associated with moderate-to-severe dementia. This apparent incongruity has been explained by the on-rate for channel blockage by memantine being increased by increasing the drug’s concentration, which leads to a greater proportion of channels being blocked.66 To increase the neuroprotective efficacy of memantine, a second-generation derivative has been designed to incorporate a nitric oxide moiety, which should bind to the sulfhydryl group of a cysteine residue in the channel pore that has been found to down-regulate NMDA receptor activity.58, 69

Much work remains for the design of therapeutic agents that can modulate NMDA receptors without adversely affecting normal cellular processes regulated by these channels. One more recent approach toward accomplishing this goal would be to design ligands that are subunit-specific and serve as noncompetitive antagonists.31 The first subunit-selective NMDA receptor antagonist was ifenprodil (10), which inhibits Glu2B-containing receptors with a 200 to 400-fold selectivity over receptors containing Glu2A, Glu2C, and Glu2D subunits, and an IC50 of 0.34 μM for the GluN1/Glu2B receptor.31, 70 The difficulty in designing noncompetitive antagonists for the Glu2B subunit, which may be therapeutically relevant for a number of disorders, is that they also act at other receptors and channels, leading to side effects, causing a sub-efficacious lowering of the dose.71, 72 To improve selectivity, ifenprodil analogue 1173 and traxoprodil (CP-101,606, 12)74 were designed. Analogue 11 was found to be more effective than 10 in preventing toxicity to cortical neurons that mimic ischemic brain damage when exposed to glutamate (IC50 of 0.4 versus 3.5 μM, respectively).73 Compounds 10-12 have antiparkinsonian activity in animal models. In a study of the use of 12 in counteracting dyskinesia and parkinsonism, it was found to reduce the maximum severity of l-DOPA-induced dyskinesia by approximately 30%, although many of the subjects in the study experienced dissociation, abnormal thinking, and amnesia. Compound 12 did not reduce parkinsonism in the study; however, the antidyskinetic effects were maximal at a lower dose, and the adverse effects were found to be dose-responsive.75

Among the recently identified voltage-independent negative allosteric modulators of NMDA receptors is 13, one of the quinazoline-4-one derivatives advanced by Traynelis and co-workers.76 Compound 13 had approximately 50-fold selectivity for recombinant GluN2C/D-containing receptors over GluN2A/B-containing receptors, low micromolar potency, and a novel mechanism that requires binding of glutamate to the GluN2 subunit, but not glycine binding to the GluN1 subunit. The GluN2C/D over GluNA/B subunit selectivity of 13 was determined from ABD residues adjacent to the transmembrane helices.77 Differing subunit selectivity profiles for negative allosteric modulation were also seen in a recent series of naphthalene and phenanthrene derivatives.78 9-Iodophenanthrene-3-carboxylic acid (UBP512, 14) inhibited only GluN1/GluN2C and GluN1/GluN2D receptors, while 6-bromocoumarin-3-carboxylic acid (UBP608, 15) inhibited GluN1/GluN2A receptors (23-fold) over GluN1/GluN2D, with IC50 values in the micromolar range. Consistent with their characterization as allosteric modulators, these compounds were found to be voltage-independent and not competitive with glutamate and glycine agonists. The site of action for 14 and related compounds is thought to be at the dimer interface between the ABDs, and the NTD was not found to be necessary for inhibitory activity.78 Another negative allosteric antagonist, dihydropyrazoloquinoline 16, inhibited GluN2C- and GluN2D-containing NMDA receptors over recombinant GluN2A- and GluN2B-containing receptors, with at least 50-fold difference in IC50 values. The selectivity was attributed to residues in the membrane-proximal lower lobe of the GluN2 ABD.79

Bettini and co-workers reported several sulfonamide derivatives from high-throughput screening that were selective antagonists at GluN1/GluN2A over GluN1/GluN2B.80 Addition of 1 mM glycine, but not 1 mM L-glutamate, overcame the inhibitory effects of the two most promising compounds. It was subsequently determined that one of the compounds, 17, binds to a novel allosteric site at the dimer interface between the GluN1 and GluN2 ABDs, thereby reducing glycine potency (IC50 = 0.1 – 0.32 μM).

To exploit the subunit selectivity of these newer pharmacological tools for therapeutic advantage, it will be necessary to map the relative contribution of each subunit to its function in both normal cellular processes as well as in disease states. Recently, it was found that the NMDA receptor subtype specificity of three crucial channel properties – Mg2+ blockage, relative Ca2+ permeability, and single-channel conductance – were all determined primarily at a single GluN2 subunit residue in the transmembrane region.81 However, because of the challenges involved in obtaining highly selective antagonists, there is still relatively little known about the function and therapeutic potential of the different subunits of the NMDA receptors.49 One confounding issue in this regard is the subunit composition of the NMDA receptor, since two different GluN2 subunits may be present, rather than only the binary combination of GluN1 and one type of GluN2 (or GluN3) subunit, in different regions of the brain.82 Using recombinant heterotrimeric GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2B and GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2C receptors with Zn2+ and ifenprodil antagonism, it was found that each ligand produced only partial inhibition and that maximal inhibition was only achieved with both copies of each GluN2 subunit in the receptor.83 This finding suggested a potential limitation in using ifenprodil and its derivatives, since both GluN1/GluN2B and heterotrimeric GluN1/GluN2A/GluN2B receptors will be inhibited, possibly affecting subunit-specific control of normal neurological processes.

Other considerations may enter into the design of NMDA therapeutic antagonists, such as whether the agents will preferentially target synaptic or extrasynaptic NMDA receptors and the GluN2 subunit composition at those receptor sites. Work on the mechanism of action of memantine has shown that it preferentially targets extrasynaptic over synaptic NMDA receptors in a hippocampal autaptic neuronal preparation. In this study, the synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA receptors in mature neurons differed in subunit composition, with the GluN2A receptors predominating at the synaptic receptors and the GluN2B subunits at the extrasynaptic receptors.84 When cultured primary striatal or cortical neurons from rat were transfected with the gene coding for mutant huntingtin, a protein with polyglutamine repeat residues implicated in the pathogenesis of HD, and treated with D-APV, memantine, or ifenprodil, there was a significant decrease in the number of neurons expressing aggregated mutant-protein macro inclusions.85 Further studies using a transgenic YAC128 mouse HD model showed that at high concentration of memantine both synaptic and extrasynaptic NMDA-mediated currents were blocked, worsening neurodegeneration; at low concentration of memantine the extrasynaptic receptors were predominately blocked, leading to a neuroprotective effect (reduction of striatal volume loss and motor learning deficits at 12 months post-treatment) from the largely unaffected synaptic activity.85 Milnerwood et al. reported a similar reversal in intracellular signaling and motor learning deficits, when the extrasynaptic NMDA receptors of YAC128 HD mice were pharmacologically blocked with a low dose of memantine, thus providing further evidence for a new therapeutic approach to combating HD.86, 87

In view of the complex interplay of factors affecting NMDA receptor function, an integrative approach involving the modulation of receptor-associated pathways in the disease state may constitute a viable therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative disorders. Since an excessive influx of Ca2+ ion into neurons is an important factor in the excitotoxic process, blockade of NMDA receptors could potentially be offset by the presence of L-type voltage-gated calcium channels. 88 Thus, design of therapeutic agents that can jointly antagonize both targets may be a desirable goal, and at least one such compound (18) has been developed.89-91 Dimebon (latrepirdine) (19), an antihistamine compound used clinically in Russia for many years, has demonstrated efficacy in Phase II clinical trials for AD and HD,92 although a Phase III trial for use in mild-to-moderate AD gave disappointing results.93 Dimebon was found to inhibit both NMDA receptors (IC50 = 10 μM) and L-type calcium channels (IC50 = 50 μM) in cultured neurons, possibly accounting, at least in part, for its mechanism of action.92, 94, 95 Blockage of NMDA-induced currents was different from that of memantine, suggesting a different site of action for dimebon at the NMDA receptor.95

Influx of calcium via NMDA receptors can induce necrotic or apoptotic cell death, depending on the degree of glutamate stimulation, with the cellular fate influenced by the effect of the resultant intracellular calcium concentration on the mitochondria.96 A therapeutic approach targeting the apoptotic pathway had mixed results when compounds shown to be effective both in vitro and in animal models for several neurodegenerative disorders were tested in human clinical trials.97-99

Another strategy for counteracting neuronal excitotoxicity might involve co-administration of an NMDA antagonist with an inhibitor of glutamate release. One potential candidate, riluzole (20), has been approved for use in treating the symptoms of ALS, although with limited success.48 In addition to its role as an inhibitor for glutamate release, riluzole also protects neurons against NMDA-induced toxicity.100-102 A clinical trial for use of riluzole in early PD showed that it was well tolerated in patients, but with no significant difference relative to the placebo group.103 Similarly, a 3-year randomized controlled study showed no neuroprotective or beneficial symptomatic effect of riluzole in HD.104 An alternative to inhibiting glutamate release might be to use an agonist, such as ceftriaxone (21), for stimulation of glutamate uptake transporters. Ceftriaxone, a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, was found to be a potent modulator of glutamate transport through NF-κB-mediated excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EAAT2) in primary human fetal astrocytes105 and was in a clinical trial for ALS.48

Another important facet of an integrative therapeutic strategy to combat neurodegenerative diseases is the role that metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) may play in the neural excitotoxicity process. An advantage of additionally targeting the mGlu receptors is that they can modulate the activity of voltage-gated calcium channels, while not affecting fast excitatory synaptic transmission.106 Pharmacological blockade of mGlu5 receptors has led to reduced neuronal death in animal models of PD and ALS, and negative allosteric modulators for this receptor, as well as selective mGlu3 receptor agonists, have been in clinical development.107 A recent perspective provides an excellent overview of this subject.108

3 Voltage-Gated Calcium Channels

In the central nervous system, calcium’s conductance properties are principally mediated by two types of receptors: ligand109 and voltage-gated channels.110 While NMDA receptors are involved in the total calcium load in neurons, smaller, but still significant, calcium contributions are mediated primarily through voltage-gated calcium channels.111 Voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) are expressed on the plasma membrane and open in response to depolarizing stimuli (events that lower the resting potential of neurons). In most physiological environments, VGCCs shuttle calcium from the extracellular space into the intracellular space. The accessory subunit and conducting pore (α1-subunit) that constitutes VGCCs is the portion of the channel that conducts calcium, gives rise to the biochemical and biophysical properties in identified channels, and is the major site of pharmacological action. To date, ten types of α1-subunits have been identified, normally classified into five subtypes: L-type (Cav1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4), P/Q-type (Cav2.1), N-type (Cav2.2), R-type (Cav2.3), and T-type (Cav3.1, 3.2, 3.3).112

Cav1.1, Cav1.2, Cav1.3, and Cav1.4 α1-subunits, constituting the family of L-type calcium channels (LTCCs), are central players in neuronal calcium dynamics in both physiological and pathophysiological states. α1-Subunits constituting Cav1.1 and Cav1.4 LTCCs are predominantly expressed outside of the central nervous system, in skeletal muscle and the retina, respectively.109 Functional Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 LTCCs are found in cardiovascular113 and nervous tissue, respectively,114 and play central roles as pharmacological targets in anti-arrhythmia and anti-hypertension therapeutics. 1,4-Dihydropyridines (DHPs), phenylalkylamines (PAAs), and benzodiazepines (BZAs) are among the most common LTCC channel antagonists.115, 116

Cav1.3 LTCCs have been identified as playing a role in the progression of Parkinson’s disease by allowing uncompensated calcium loading in dopaminergic (DA) neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), which subsequently places a heavy and unsustainable metabolic burden on these neurons. It has been shown that by antagonism of these channels non-selectively with isradipine (22), a potent LTCC inhibitor, SNc DA neurons exhibit less metabolic stress and are protected in multiple PD animal models.117 Selective antagonism of Cav1.3 LTCC is therefore hypothesized to be potentially neuroprotective in early or presymptomatic stages of PD.

While promising, isradipine is non-selective; it is also a potent Cav1.2 LTCC inhibitor. Therefore, long-term use of isradipine as a treatment for PD might result in hypotension or peripheral edema. Even if this does not result directly from isradipine use, it is known that during the course of PD, hypotension is common, thereby exacerbating this undesirable side-effect.118 Moreover, the non-selective nature of DHP inhibition of both neuronal types of LTCCs, Cav1.2 and Cav1.3, makes dosing regimens of isradipine, or other non-selective DHPs that might be disease-modifying in PD or other neurodegenerative diseases, an impossibility because the efficacious dose may have a serious effect on the therapeutic index of this strategy.119 None of the Cav1 antagonists in the clinic preferentially selects for Cav1.3 channels.114, 120 Thus, the search for more isoform-selective Cav1.3 LTCC antagonists has garnered recent attention.

Chang et al. described121 a comprehensive structure-activity-relationship (SAR) study of modifications to the structurally simple, active DHP nifedipine122 (23). A collection of 124 chemically diverse 4-substituted 1,4-dihydropyridines was generated; however, little selectivity of Cav1.3 over Cav1.2 was obtained. The most selective compounds generated (24 and 25) possessed Cav1.3 selectivities of only 2.2 and 2.4-fold, respectively, and both demonstrated only micromolar potencies. Observations from the SAR study showed an activity pattern for 4-substituted 1,4-dihydropyridines of substituted phenyl > thienyl > furyl > pyridyl > napthyl > alkyl (cyclic alkyl), with substitution of the phenyl ring at the 2-position the most potent and at the 4-position the least potent. Complete loss of activity was observed when the pyridyl nitrogen was methylated or replaced with oxygen. These data implied that the generation of a high Cav1.3 selective DHP may be unlikely, and attention was focused on the generation of new scaffolds.

Compounds that show Cav1.3 LTCC inhibition, however selective, must maintain good pharmacokinetic properties and structure components with good potential for passing through the BBB. A high-throughput screen was initialized by the Silverman laboratory to identify novel Cav1.3 selective LTCC inhibitors by use of a calcium-sensing fluorescent imaging plate reader (FLIPR) assay. Over 60,000 molecules from a variety of commercial and government libraries were screened for activity with no hits resulting. In parallel with this screen Xia et al. described a series of symmetric pyrimidine-2,4,6-triones (PYT) investigated for applications in anti-aggregation ALS models, possessing good pharmacokinetic properties and BBB penetration.123 About 200 of these compounds and other scaffolds from the Silverman lab that were active in anti-aggregation assays were tested, and the first PYT Cav1.3-selective antagonists were realized, although most of the compounds screened showed Cav1.2 selectivity. The lead compound was modified, providing the first highly selective Cav1.3 antagonist (26),124

4. Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase Inhibitors

As shown in the Figure 1 cellular cascade, activation of the NMDA receptor leads to calcium influx, which activates many downstream proteins, including nNOS.125 The signaling molecule, nitric oxide (NO), is a free radical that is produced by nitric oxide synthases (NOSs) from substrate l-arginine, molecular oxygen, and NADPH. There are three isoforms of NOS: neuronal NOS (nNOS), which produces NO as a neurotransmitter; endothelial NOS (eNOS), which produces NO to signal the relaxation of smooth muscle cells in blood vessels; and inducible NOS (iNOS), which produces a burst of NO in response to invading pathogens. The prominent role of NO in the nervous system leads to the possibility of improper regulation of NO and, therefore, various disease pathologies. High levels of NO have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases including ALS and PD.126 NO itself is a reactive molecule that leads to the formation of other oxidative species, such as superoxide and peroxynitrite. Also, nitrated protein aggregates, which are highly toxic to neurons, are found in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. S-Nitrosylation of proteins is a common feature of Lewy bodies and intraneuronal protein aggregates found in PD.127 Increased nitrosative stress may also compromise the ubiquitin degradation system, which, when impaired, cannot properly degrade proteins, leading to aggregation.125 Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase implicated in PD, has been shown to be S-nitrosylated, which impairs its function and leads to increased protein aggregation.128-130 S-Nitrosylation of Hsp90 compromises its protection abilities as a chaperone, and leads to increased aggregation.131 NO stress can also compromise mitochondrial function. Electrons leak from the electron transport chain (ETC) to react with NO, forming peroxynitrite (ONOO−), which damages lipids, proteins, and DNA.132 S-Nitrosylation of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic proteins, p21, Ras, and Bcl-2 alters their activity.132 Two of the isoforms of NOS, nNOS and eNOS, are constitutively expressed and activated by an increase in intracellular calcium concentration. Calcium binds to calmodulin, a small protein, and this complex binds and activates these NOSs.133

NOS inhibitors as potential therapeutics have been sought since the discovery of NO’s signaling role in the late 1980s. Since crystal structure information was not yet available, early inhibitors began as arginine analogues, shown in Table 1 (27 - 33).134 These inhibitors, however, lacked selectivity. Selectivity has proven difficult to achieve over the past 20 years because of the high homology of the isoforms, especially in the active site. N-Nitro-l-arginine (L-NNA, 27) does show some selectivity, about 250-fold for nNOS over iNOS, but essentially no selectivity for nNOS over eNOS.135 Because of the important role of eNOS in vascular regulation, this poor selectivity over eNOS leads to hypertension in animals.136 L2NNA (27), L-NMA (28), and L-NAME (29) are commonly used in both in vitro and in vivo pharmacology experiments because of their stability, commercial availability, low toxicity, and solubility. Thiocitrulline and methylated thiocitrulline analogues have also been explored, but selectivity over eNOS has been difficult to achieve.134

Table 1.

Structures, potencies, and selectivities of arginine analogues. Data reported from Erdal et al. and references within.134

| Selectivity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | R 1 | R 2 |

K

i rat

nNOS (μM) |

nNOS/eNOSa | nNOS/iNOSb | ||

|

27 | L-NNA | NO2 | H | 0.015c | 11 | 293 |

| 28 | L-NMA | CH3 | H | 0.2 | 4.5 | 65 | |

| 29 | L - NAME | CH3 | CH3 | -d | - | - | |

| 30 | L-NAA | NH2 | H | 0.3 c | 8.3 | 10 | |

| 31 | L-ALA |

|

H | 0.2 c | 35 | 11 | |

| 32 | L-NCPA |

|

H | 0.6 | - | 400 | |

| 33 | L-NPA | CH2CH2CH3 | H | 0.55 | 18 | 145 | |

Notes:

Ki bovine eNOS / Ki rat nNOS.

Ki murine iNOS / Ki rat nNOS.

bovine nNOS, not rat nNOS.

L-NAME presumably is hydrolyzed to L-NMA intracellularly or in vivo.

Using L-NNA as a starting point, Silverman and coworkers developed several series of nNOS-selective dipeptides (see Table 2). This approach takes advantage of the potency of the arginine analogue scaffolds, but also provides compounds that can potentially extend out of the heme binding pocket in an attempt to interrogate the isozymes for selective contacts away from the active site. Residue differences between isoforms include: S585 in nNOS is N370 in iNOS, but S356 in eNOS; and D597 nNOS is N368 in eNOS.

Table 2.

Dipeptide ester and amide nNOS inhibitors.

| Selectivity | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R |

K

i rat nNOS

(μM) |

nNOS/eNOSa | nNOS/iNOSb | ||

|

34 137 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1800 | |

|

35 138 | 0.13 | 1540 | 190 | |

|

36 140 | 0.10 | 1280 | 290 | |

|

|

37 141 | 0.12 | 2600 | 330 |

|

38 142 | 0.05 | 2100 | 70 | |

Notes:

Ki bovine eNOS / Ki rat nNOS.

Ki murine iNOS / Ki rat nNOS.

Early dipeptide esters (34) achieved impressive selectivity over iNOS,137 while more optimization led to 35, which is highly selective over eNOS (1500 fold).138 Modifications of the peptide scaffold included acetylation, benzyloxycarbonylation, amide-methylation or conversion to peptoids, in an attempt to protect against metabolic degradation, but led to drops in selectivity.139 Exploration of conformationally-rigid analogues of 34 led to highly potent, selective dipeptide amides 36,140 37,141 and 38,142 but these compounds have limited BBB permeability because of their tricationic structures.

As crystal structures of NOS became available,143, 144 nNOS inhibitors moved away from the arginine mimetic scaffold. The Silverman group switched their strategy to de novo design using a pharmacophoric approach they developed termed “fragment hopping”.145, 146 This led to a potent, nNOS selective aminopyridine scaffold (±39). Optimization led to potent, selective nNOS inhibitors (±40), and replacement of a nitrogen atom with an oxygen atom increased bioavailability (41).145 Furthermore, (±)-40 was shown to prevent hypoxia-ischemia-induced death in a rabbit model of cerebral palsy.147 Upon maternal administration, (±)-40 and an analogue was able to distribute readily to the fetal brain, inhibit NOS activity and decrease NO concentration in vivo, to be nontoxic, without detrimental cardiovascular effects, and show a remarkable protection of fetal rabbit kits from the HI induced phenotype of cerebral palsy. The rabbit kits from saline-treated dams had a large incidence of fetal/neonatal deaths (16/34; 47%) but no deaths (0/49) were observed from animals treated with (±)-40 and its analogue. Of the kits from saline-treated dams that came to term (18/34), severe neurobehavioral abnormalities occurred in 12/18 (67%) compared to only 7/49 (14%) in those from dams treated with the inhibitors. Furthermore, the inhibitor-treated animals exhibited a remarkably larger number (83%) of normal kits; only 9% (3/34) of the kits from saline-treated dams were born normal.

Crystal structures of single enantiomers 41 and 42 revealed a surprising difference in binding mode.148 Previous crystal structures show aminopyridines bind NOS with the aminopyridine head over the heme, but the (R,R) stereochemistry of 42 induces a flipped binding mode with the fluoro-phenyl tail binding over the heme. Moreover, this flipped binding mode is more potent; the Ki of 42 is 7.2 nM, which is lower than the Ki of 41 (116 nM) for nNOS.149 Bioavailability of these inhibitors is poor as a result of the multiple cationic charges. A successful attempt to increase bioavailability and take advantage of the two binding pockets for the aminopyridine head led to 43,150 which displayed decreased nNOS selectivity. Compound 43 is a lead compound for designing future selective inhibitors of nNOS with increased bioavailability and a synthetically simple structure.

The aminopyridine moiety is a bioisostere of the guanidium group of arginine. 2-Amino-4-methylpyridine (44) was found to be potent both in vitro and in vivo, but is non-selective.151 Simple substituted 2-aminopyridines were studied as NOS inhibitors, but were found to be mostly selective for iNOS.152 6-Phenyl-2-aminopyridines were explored by Pfizer in the early 2000s as nNOS selective inhibitors. Compound 45 had an IC50 of 140 nM for human nNOS, but only modest selectivity over eNOS (6 fold).153 Compound 46 has an IC50 of 70 nM for human nNOS with 50- and 10-fold selectivity over eNOS and iNOS, respectively. The compound possessed a good pharmacokinetic profile and was well tolerated and effective in vivo.154

L-NIO (47) is an arginine analogue known to be a non-selective inactivator of NOS.155 Compound 48,156, is an nNOS selective reversible inhibitor, unlike its homologue 49,157 which is iNOS selective and is an irreversible inhibitor. Compound 48 is selective for nNOS over eNOS (155 fold) and potent (IC50 human nNOS = 40 nM) but is not effective in vivo in rats.156 nNOS selective carbamidines 50 and 51 were reported by Amoroso and coworkers;158 computer modeling was used to rationalize that the selectivity of these bulky inhibitors is the result of the larger heme binding pocket of nNOS compared to that of eNOS and iNOS.

Another successful guanidine-mimetic moiety is the thiophene amidine (thienylcarbamidine) (52). Developed by AstraZeneca, 52 is a selective nNOS inhibitor with an IC50 of 0.035, 5.0 and 3.5 uM for human nNOS, iNOS and eNOS, respectively.159 It has been shown to effectively cross the BBB in animal studies and to be neuroprotective in ischemia models.160 Crystal structures reveal that the amidine nitrogens hydrogen bond to nNOS Glu592, much like arginine, while the thiophene sulfur lies 3.4 Å above the heme iron, but does not coordinate as a sixth ligand.161 NeurAxon has further explored the thienylcarbamidine functionality with 53 and 54; these nNOS selective inhibitors are being developed for the treatment of migraine pain. Compound 53 is a dual-acting inhibitor of nNOS (IC50 of 0.44 μM) and agonist of the μ-opioid receptor (Ki of 5.4 nM), which is involved in pain.162 Compound 54 is a potent, selective nNOS inhibitor without any cardiovascular effects and with a good side effect profile.163

A variety of other scaffolds have been explored as NOS inhibitors, but they are beyond the scope of this perspective. They are described in detail in other excellent, recent review articles.134, 164, 165 The compounds described above have all been active site inhibitors. Inhibitors that disrupt dimerization166 and inhibitors that displace tetrahydrobiopterin167 also have been explored as NOS inhibitors.

5. Antioxidants as therapeutics for neurodegenerative disorders

Misregulation of nNOS production can lead to oxidative stress, a hallmark of neurodegeneration. In addition to unregulated production of nitric oxide (NO) by nNOS, other reactive oxygen species (ROS) exist and have also been implicated in neurodegeneration. A large number of ROS are free radicals or radical-generating derivatives of oxygen such as superoxide (O2•−), hydroxyl radical (•OH), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Cellular damage in the nervous system by free radical species has been implicated in AD,168-173 PD,174-177 HD,178 and ALS.179, 180 Antioxidants are molecules that react with ROS to deactivate them and are of interest as potential therapeutics. Here, we present a summary of the major classes of antioxidants and their known or potential efficacy as treatments of neurodegenerative disease.

Compounds that can directly react with free radical species are referred to as direct antioxidants. These compounds do not generally rely on endogenous cellular mechanisms to wield their primary effect. The major classes of direct antioxidants include phenols, low-molecular weight enzyme mimetics, and polyenes. Because of their ability to quench free radical species, direct antioxidants can halt the procession of potentially damaging radical chain reactions.

Free radical scavenging phenols, which rely on the facile ability of phenols to be oxidized to their corresponding quinones, can be divided into two categories: monophenolic and polyphenolic compounds. Monophenols vitamin E (α-tocopherol, 55) and estrogens (56) have been repeatedly investigated for potential efficacy in treating a number of neurodegenerative diseases. Vitamin E has been shown to offer modest cognitive benefits in some AD patients;181-183 however, other studies have shown no preventative benefit of vitamin E for AD development.182-186 While no significant effects have been observed in PD187-190 or HD,191 vitamin E was found to delay onset as well as slow the progression of ALS.192, 193 The use of estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) is also believed to play a preventative rather than therapeutic role in AD,194-198 and it is likewise the case for PD,199-201 which may be related to the increased disease prevalence observed in men over women.202, 203 Polyphenols, which include well-known compounds resveratrol (57) and curcumin (58), as well as a large family of flavonoids such as quercitin (59) and epicatechin (60), have already been extensively reviewed for their potential therapeutic properties.204-207

Under normal conditions, cellular antioxidant defense mechanisms are present to combat both metabolic and exogenous sources of ROS. These mechanisms include both small molecules and enzymes. The primary small molecule utilized is glutathione (GSH), a tripeptide possessing a sulfhydryl moiety capable of donating electrons to oxidized molecules, followed by regeneration via NADPH.208, 209 As for antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase (SOD) converts O •−2 into H2O2, which can then be rapidly reduced by catalase or glutathione peroxidase (GPx) to H2O and O2.177, 210, 211 The metabolism of O2•− and H2O2 is critical because O2•− can react with NO to form peroxynitrite (ONOO−), and H2O2 can react with Fe2+ to generate •OH, which are highly reactive species that are capable of lipid, protein, and DNA damage.209, 212 A study of potential low-molecular weight mimics of SOD and GPx has identified a small number of potential therapeutics. The small, organoselenium compound ebselen (61) has exhibited notable activity as a GPx mimetic and ONOO− scavenger in vitro213, 214 and has shown significant beneficial effects in a primate model of PD.215 Ebselen’s catalytic ability can be initiated with or without the presence of ROS. In the presence of oxidative species, oxidation to the selenoxide (Se=O) followed by reduction via a thiol electron donor generates a reactive selenenic acid (Se–OH) that readily loses water and converts back to ebselen. Without the presence of ROS, oxidation of a free thiol forms a selenyl sulfide (Se–S-R) leading to the production of a disulfide (R-S–S-R) and a selenol intermediate (Se–H). The selenol can be readily oxidized by ROS to form selenenic acid, which leads to regeneration of ebselen.216 The organoselenium compound 62, similar to ebselen, has shown even higher in vitro GPx-like activity and may also possess therapeutic potential for PD or other neurodegenerative disorders.217, 218 Organoselenium compound 62 is currently in clinical trials for cardiovascular indications.

In addition to the therapeutic potential found in GPx mimetics, Mn-containing complexes have been found to be effective SOD mimetics. Metalloporphyrins 63 and 64 have been found to exhibit high SOD activity, catalase activity, as well as inhibition of lipid peroxidation.219, 220 The antioxidant activity of 63, 64, and similar metalloporphyrins has been extensively studied in a variety of models for oxidative neuronal damage.221 Salen manganese complexes 65 and 66 are also SOD and catalase mimetics. These complexes

have been shown to confer neuroprotection in both in vitro and in vivo models for PD.222, 223

have been shown to confer neuroprotection in both in vitro and in vivo models for PD.222, 223

Polyene antioxidants are primarily comprised of carotenoids, such as β-carotene (67), lycopene, retinol, and lutein, and are typically of plant origin. These carotenoids are capable of scavenging singlet molecular oxygen (1O2) and peroxyl radicals forming stabilized radicals that can further react with ROS to halt radical chain reaction processes.224 The rate constants for singlet oxygen quenching by carotenoids are in the range of 109 M−1 s−1, which is near diffusion control.225 Peroxyl radical scavenging is also efficient, especially under hypoxic conditions, and is important for the prevention of lipid peroxidation.226 Carotenoids are an important part of the diet of animals because many carotenoids are metabolized to retinol (vitamin A), which cannot be synthesized endogenously. Retinoic acid (RA), an irreversibly oxidized form of retinol, is an important signaling molecule involved in embryonic growth and development. There have been a number of studies that suggest the therapeutic potential of RA for AD prevention,227, 228 but there has been no evidence to suggest a direct antioxidant effect of carotenoids being involved in neurodegenerative prevention. A more recent study, however, has shown that all-trans RA (ATRA, 68) treatment invokes a decrease in brain Aβ deposition in an AD mouse model by inhibition of amyloid precursor protein processing.229

Indirect antioxidants are compounds that do not directly react with ROS, but are involved in cellular management of oxidative species. Many of these compounds are essential cofactors required for cellular oxidative metabolism; however, a number of synthetic compounds have been identified that fall under this classification. These compounds act by easing the secondary metabolic burden of free radicals and therefore diminishing oxidative damage.

Quinones are a class of compounds, often derived from aromatic compounds, containing two carbonyl groups in an unsaturated six membered carbon ring. The general label of vitamin K is applied to a number of related quinone compounds with a polyprenylated naphthoquinone ring structure. The primary role of vitamin K is to act as a necessary enzyme cofactor for a number of processes that include blood coagulation230 and bone metabolism.231 There is growing evidence, however, that vitamin K has important functions in the brain, and that a deficiency may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD.232 Ubiquinone (69), also known as coenzyme Q10, serves as an important cofactor, primarily in the electron transport chain during aerobic cellular respiration. Ubiquinone has been found to exert a protective effect against PD and HD,233, 234 in addition to reducing intracellular Aβ deposition235 and plaque pathology in AD mouse models.236

The mitochondrial-targeted ubiquinone analogues 70 and 71 have shown encouraging results for the treatment of age-related neurodegenerative disease.237 Targeted delivery of these analogues is made possible by the cationic triphenylphosphonium group, which takes advantage of the potential gradient of the inner-mitochondrial membrane. Both have gone to clinical trials.238

Spin trapping compounds are labeled as such because of their ability to form adducts with free radicals via their nitrone functionality. Initially utilized in analytical chemistry, spin traps have exhibited biological activity in a number of ROS implicated disease states.239, 240 Although spin traps are capable of directly quenching ROS, recent evidence suggests that they induce a number of endogenous antioxidants and enzymes involved in the attenuation of oxidative cellular damage.241 α-Phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN, 72) has exhibited efficacy for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases by affecting signal transduction pathways related to neuroinflammatory processes.242, 243 On the other hand, Cerovive (73) was tested in stroke patients in clinical trials and failed to show efficacy, likely because of its poor pharmacokinetic properties.244 The more lipophilic nitrones 74 and 75 have much higher radical scavenging potential over PBN and Cerovive and have both exhibited neuroprotective efficacy in mouse models of PD.245, 246

This final category of antioxidants is composed of a large and mixed group of compounds that are employed by the cell in the transport of reducing equivalents. Prominent examples include ascorbate (76), which has exhibited antioxidant activity in several in vitro studies,247 and the previously mentioned GSH (77). A number of thiol precursors of GSH belong to this category as well. These include the dipeptide CysGly, which is used to generate GSH in neurons,248 as well as cysteine precursors N-acetylcysteine (78) and procysteine (79).249, 250 Despite no known efficacy of these compounds for the treatment or prevention of neurodegenerative disease, brain levels of GSH are depleted by up to 30% in the elderly, suggesting a strong link to age-related disease.

The nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaled gene expression in response to cellular stress must be considered when discussing potential therapeutic effects of antioxidants. Nrf2 is a transcription factor responsible for the activation of a number of genes whose products are important in the reduction of cellular oxidative stress. These genes, which include glutathione-S-transferase (GST), coenzyme Q10, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase, superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), and many others, contain a common promoter called the antioxidant response element (ARE). Under normal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to repressor protein Keap1 (Kelch ECH associating protein 1) and retained in the cytoplasm. In the Nrf2-Keap1-ARE expression pathway, Keap1 acts as a sensor for oxidative stress through oxidation of or electrophilic addition to its many cysteine residues.251 Alteration of the cysteine residues of Keap1 disturbs Nrf2 binding, which allows Nrf2 to translocate into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, Nrf2 heterodimerizes with members of the small Maf (sMaf) family of transcription factors, binds to the ARE, and ultimately leads to gene expression (Figure 3). An ever-growing number of molecules able to induce Nrf2 signaling have been identified, including many previously mentioned antioxidants. These molecules, and the varying chemical characteristics that provide their activity, have previously been reviewed in great detail.252, 253

The nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaled gene expression in response to cellular stress must be considered when discussing potential therapeutic effects of antioxidants. Nrf2 is a transcription factor responsible for the activation of a number of genes whose products are important in the reduction of cellular oxidative stress. These genes, which include glutathione-S-transferase (GST), coenzyme Q10, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase, superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), and many others, contain a common promoter called the antioxidant response element (ARE). Under normal conditions, Nrf2 is bound to repressor protein Keap1 (Kelch ECH associating protein 1) and retained in the cytoplasm. In the Nrf2-Keap1-ARE expression pathway, Keap1 acts as a sensor for oxidative stress through oxidation of or electrophilic addition to its many cysteine residues.251 Alteration of the cysteine residues of Keap1 disturbs Nrf2 binding, which allows Nrf2 to translocate into the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, Nrf2 heterodimerizes with members of the small Maf (sMaf) family of transcription factors, binds to the ARE, and ultimately leads to gene expression (Figure 3). An ever-growing number of molecules able to induce Nrf2 signaling have been identified, including many previously mentioned antioxidants. These molecules, and the varying chemical characteristics that provide their activity, have previously been reviewed in great detail.252, 253

Figure 3.

Mechanism of ARE-promoted gene expression by Nrf2. Disruption of the Keap1-Nrf2 complex allows for Nrf2 migration to the nucleus, where it joins with other transcription factors that bind to ARE regions of genes and initiate their transcription.

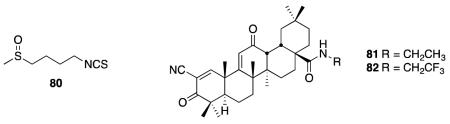

The Nrf2 system has previously been the subject of reviews in regard to its potential as a therapeutic target.254, 255 Activation of Nrf2 has been observed to prevent apoptosis of motor neurons that were co-cultured with the ALS model G93A-SOD1 mutant astrocytes. This prevention of apoptotic signaling is believed to be caused by glutathione-mediated NO detoxification.256 Downregulation of Nrf2 activated genes has also been observed in microarray analysis of mutant SOD transfected motor neuron-like Nsc34 cells.257 It has also been shown that dietary sulforophane (80), a known Nrf2 signaling activator, protects against degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in a Drosophila PD model.258 A study to assess the localization of Nrf2 in hippocampal neurons of AD indicated a loss of nuclear Nrf2 when compared to age-matched control individuals; however, cytoplasmic levels were the same between AD and control cases. This suggests impairment in nuclear trafficking and may limit Nrf2 activation as a potential AD treatment.259 In an N171-82Q transgenic mouse model of HD, upregulation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway by synthetic terpenoids 81 and 82 was found to rescue behavioral deficits, extend survival, and attenuate brain and peripheral pathology.260

6. Antiaggregation Agents

One consequence of high levels of ROS is the damage and aggregation of proteins. Neurodegenerative diseases have been termed ‘protein aggregation diseases’ because protein aggregation is another hallmark of these diseases. Aggregation consists of the formation of identical monomers of proteins self-associated into large oligomeric structures of reduced solubility that directly contribute to the onset and progression of the disease in question. Commonly implicated proteins (Table 3) include tau and amyloid-β in AD, α-synuclein in PD, huntingtin in HD, SOD1 in ALS, and others covering a range of diseases.261 The aggregation process leads to formation of fibrils with defined morphologies or amorphous deposits, or both. Here, we present an overview of therapeutic targets and a selection of molecules displaying anti-aggregation properties. In this section we will concentrate on the most frequently studied protein targets for the development of antiaggregation inhibitors as listed in Table 3. Additional targets are known, and inhibitors are being actively developed; however, space precludes a detailed examination of all potential targets. Comprehensive introductions to the subjects of pathogenicity and potential targets,262 and strategies for the design of anti-aggregation inhibitors263 that have been published previously, are excellent sources of in-depth coverage of the subject matter.

Table 3.

Proteins implicated in misfolding aggregation diseases and respective targets for aggregation inhibitor compound design, as discussed herein.

| Disease | Aggregating Protein | Direct Targets | Indirect Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s | Amyloid-β | BACE-1 α-secretase γ-secretase Metal chelators |

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors Protein kinases (GSK3, CDK5) Autophagy activators |

| Tau | Physiological tau | ||

| Parkinson’s | α-synuclein | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors Protein kinases (LRRK2) Autophagy activators Heat Shock Protein |

|

| Huntington’s | Huntingtin | PolyQ aggregates | HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors Autophagy activators Heat Shock Protein |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

SOD1 and many others implicated |

Protein Kinases (GSK3) Autophagy activators Heat Shock Protein |

Inhibiting the accrual of misfolded forms of the proteins comprising aggregates is one commonly exploited approach for targeting many neurodegenerative diseases. Kinase inhibitors offer the advantage of allowing inhibition of the transformative process responsible for misfolding over inhibition of the production of the naturally occurring protein, which may be crucial to normal cellular function. Dual inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK23)264 and cyclin-dependant kinase 5265 is a promising strategy for tau-related diseases such as AD, when hyperphosphorylation of tau protein leads to malfunction and aggregation.266 One such example of a dual-acting inhibitor for both kinases is the natural product hymenialdisine 83, which has been the basis of intense SAR and analogue development to generate potential therapeutic candidates.267 Similarly, GSK23 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of a number of neurodegenerative diseases, such as ALS268 and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA).269 GSK23 inhibitor VII (84) has been shown to significantly delay the onset of symptoms and extend the life span of a G93A-SOD1 mouse model of ALS.270 BIP2135 (85) was found to prolong the median survival of the Δ7 SMA KO mouse model of SMA and elevate survival motor neuron levels in SMA patient-derived fibroblast cells.269 Leucine-rich repeat kinase-2 (LRRK2) may regulate the propensity of α-synuclein to aggregate and, as a result, has garnered much attention as a target for a therapeutic intervention in PD.271

Inhibition of tau aggregation has become an important strategy in targeting pathological tau. The use of small molecules to inhibit self-assembly of tau into oligomeric and/or polymeric species, including the well-defined fibrils comprising neurofibrillary tangles, has met with mixed success. Several compounds demonstrate activity in vitro; however, most also suffer from toxicity and/or limited CNS uptake issues.272 A testament to the difficulty in designing tau inhibitors is the fact that one of the most promising structures is still one of the originally reported compounds having tau aggregation inhibition activity – methylene blue (86).273 While methylene blue itself only possesses weak inhibitory activity, the compound provided a lead scaffold for derivatization. The dimethyl derivative, tolonium chloride, was found to exhibit 30-fold greater activity with a Ki of 69 nM, acting at almost equimolar concentrations with tau. Crucially, the compound did not inhibit the required tau-tubulin binding interaction. Interestingly the inhibitory activity was also observed in hyperphosphorylated tau, bringing into question the need to inhibit kinases to elicit a subsequent inhibition of tau aggregation. Recent advances have identified aminothienopyridazines (ATPZs) as a novel class of tau fibrilization inhibitors with efficacy in in vitro models and favorable drug-like properties. Compound 87 represents the current lead structure, demonstrating good brain penetration, oral bioavailability, and non-specific brain tissue binding. The compound is set to undergo long term in vivo testing.274 Refinement of in vitro models of tauopathy will also have a large impact on drug design targeting tau aggregation. A recently disclosed model using inducible hippocampal brain slices provides a more robust assay environment for further advances.275

Accumulation of oligomeric β-amyloid peptides (Aβ) is characteristic of AD and is the primary agent in the pathogenesis of the disease. Aβ is generated from the amyloid precursor protein (APP) via two proteolytic enzymes, β-secretase and γ-secretase, responsible for the regulation of the first step in amyloidogenic APP metabolism and generation of Aβ, respectively. α-Secretase conducts an alternative proteolytic cleavage that prevents Aβ production and accumulation. Development of β-secretase (BACE-1) inhibitors has been hindered because of poor BBB permeability.276 Recent efforts have moved away from peptide-based compounds to more lipophilic structures such as difluoride 88, which demonstrated a 70% reduction of Aβ in beagle dog CSF up to nine hours after dosing.277 Progression to Phase I trials followed, showing, for the first time, a good correlation with preclinical and clinical efficacy. However, rat toxicology data indicated renal toxicity from an off-target interaction that has yet to be identified. The compound succeeded in demonstrating BACE to be a ‘druggable’ target. Potent compounds inhibiting γ-secretase have been developed; however, inherent toxicity problems still remain as a challenge.278 Avegacestat (89) a potent and selective γ-secretase inhibitor, succeeded in reducing brain levels of Aβ40 in wild-type rats by 59 ± 12% with a 30 mg/kg dose.279 However, the compound has now been dropped from clinical studies by BMS. Modulation of α-secretase is an increasingly attractive target in AD therapy; activation is controlled by the protein phosphorylation signal transduction pathway of protein kinase C (PKC).280 The known PKC activator bryostatin (90) promotes sAPP-α-secretase at sub-nanomolar levels;281 analogue construction to refine pharmacological properties has garnered a great deal of attention in the literature.282

Twenty-five percent of the cholesterol present in humans is synthesized in the brain, where it performs many vital functions, such as myelin formation, structural composition of glial and neuronal membranes, and in neurotransmission. A link between cholesterol levels and the production of APP in Alzheimer’s patients has been suggested by the use of statins, cholesterol-lowering drugs that inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, demonstrating a decreased prevalence of AD.283 In particular, simvastatin showed a marked decrease of both cholesterol and Aβ in guinea pig CSF; however, translation to human patients only showed a small decrease, which may be attributed to the higher concentration of Aβ in plaque formed within the brain and therefore not available to transfer to CSF.284 Interest in the link between cholesterol regulation and neurodegenerative diseases has grown considerably in recent years with implications ranging past AD,285 to PD,286 HD,287 and the prion diseases.288 Attempts to identify new HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and analogues of statins continue.289

There is increasing evidence that heat shock proteins (HSPs), molecular chaperones that control protein misfolding and aggregation, could counteract the pathological mechanisms that take place during AD, PD, and HD.290 The HSPs can interfere with the misfolded disease-linked proteins, thereby preventing interactions that can lead to formation of toxic oligomers. Moreover, HSPs are expected to interfere with detrimental processes that occur during these diseases, such as oxidative stress, and act in support of the ubiquitin-proteasome degradation process. These factors combine to make HSP activators an important target in combatting neurodegenerative disease.291 Central to the hypothesis of targeting protein misfolding is heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1), the main activator of chaperone protein gene expression; activating HSF1 increases the amount of chaperone expression and, in turn, the rate of clearance of misfolded proteins.292 The chaperone protein Hsp90 is responsible for protein folding regulation in many cells and, in addition, is known to bind to HSF1 and impeded activation; therefore, Hsp90 inhibitors have therapeutic potential in many neurodegenerative diseases.293 A representative example of a Hsp90 inhibitor, celastrol (91), which is isolated from a Chinese medicinal herb, is a potent inhibitor of Hsp90 acting by activation of HSF1;294 however, the exact mode of action is poorly understood and is the subject of much investigation to aid in the development of this compound as a potential therapeutic.295 Arimoclomol (92), a coinducer of heat shock proteins, increases median survival in a G93A-SOD1 mouse model of ALS by 22%, illustrating the therapeutic potential of the HSP target in ALS.296 In addition, the closely related protein, Hsp70, is rapidly gaining interest as a target for many diseases, including those contributing to neurodegeneration.297 In addition to HSP inhibitors, several other classes of compounds have been found to elicit an activation effect in autophagy and hence increase the rate of fibril clearance.298 Among the most widely investigated of these compounds are rapamycin (93), which displays neuroprotective effects in many neurodegenerative diseases,299 and the disaccharide trehalose (94), which has been shown to reverse aggregation caused by proteasome inhibition.300 HSPs act as protein folding machinery and work in conjunction with the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS),301 failure of which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of PD.302

A myriad of additional approaches for therapeutic design and intervention in neurodegenerative disease have been proposed, and a comprehensive discussion is beyond the scope of this perspective; however, several newly emerging areas will be discussed briefly. The use of chemical chaperones, small molecules having the ability to stabilize unfolded monomer conformations and/or to destabilize misfolded oligomers, has been widely explored.303, 304 An alternative approach involves the use of metal chelators, compounds that sequester physiological metal ions, and in so doing, block protein aggregation. Aβ, for example, shows ready binding to metals such as Zn2+ and Cu2+, which induce nucleation and the formation of aggregate plaques. In addition, the interaction between redox active Cu2+ and Aβ can produce neurotoxic reactive oxygen species.305 Recent developments have led to the synthesis of platiniferous chelators, such as 95, containing a Pt(bipyridine)Cl2 group as the Aβ binding portion.306 Compounds of this type show almost complete reversal of Aβ aggregation in turbidimetry experiments conducted using Aβ40. Further compounds, many of them peptidyl in structure, acting as β-sheet blockers, have been investigated.307