Abstract

Background

Deciphering the molecular and cellular processes that govern macrophage foam cell formation is critical to understanding the basic mechanisms underlying atherosclerosis and other vascular pathologies.

Methods and Results

Here, we identify a pivotal role of plasminogen (Plg) in regulating foam cell formation. Deficiency of Plg inhibited macrophage cholesterol accumulation on exposure to hyperlipidemic conditions in vitro, ex vivo, and in vivo. Gene expression analysis identified CD36 as a regulated target of Plg, and macrophages from Plg−/− mice had decreased CD36 expression and diminished foam cell formation. The Plg-dependent CD36 expression and foam cell formation depended on conversion of Plg to plasmin, binding to the macrophage surface, and the consequent intracellular signaling that leads to production of leukotriene B4. Leukotriene B4 rescued the suppression of CD36 expression and foam cell formation arising from Plg deficiency.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate an unanticipated role of Plg in the regulation of gene expression and cholesterol metabolism by macrophages and identify Plg-mediated regulation of leukotriene B4 as an underlying mechanism.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, cholesterol, plasminogen

Macrophage-derived foam cell formation, a hallmark of the progression of atherosclerosis, begins with recruitment of monocytes into the subendothelial space of affected blood vessels. In the cytokine-rich subendothelial microenvironment, monocytes differentiate into macrophages with concomitant expression of proteins that mediate the uptake of modified lipoproteins and retention of cholesterol in the cells.1,2 Among the genes upregulated during foam cell formation are scavenger (CD36, MSRA, CD68) and phagocytic (phosphatidylserine receptor, Fcγ, SRB1, ATP-binding cassette transporter [ABCA1]) receptors that mediate uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL), nuclear receptors (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor [PPAR] and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein [CEBP]) that regulate expression of the receptors involved in LDL uptake, and genes involved in eicasanoid (eg, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids, leukotrienes) biosynthesis that activate the aforementioned nuclear receptors.

Plasminogen (Plg) is synthesized primarily by the liver and circulates in the blood at 1 to 2 μmol/L.3,4 Plg is converted to an active serine protease, plasmin, by Plg activators, a transition that is influenced by interaction of Plg with C-terminal lysines of extracellular matrix and cell-surface Plg receptors (Plg-Rs). Hence, blockade of Plg with lysine analogs such as tranexamic acid or antibodies directed at the C-terminal lysine region of Plg-Rs blocks the interaction of Plg with cells and dampens plasmin generation.5

Beyond the extracellular proteolytic functions of Plg,6 its interaction with cells can trigger intracellular signaling.7,8 Plasmin activates 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO),7,9 a key enzyme in leukotriene biosynthesis that generates eicosanoids, including leukotriene B4 (LTB4), a biologically active lipid mediator associated with cardiovascular pathologies.10 Indeed, the predominant source of blood leukotrienes is inflammatory cells such as activated monocytes and macrophages.10 5-LO and LTB4 contribute to the formation of atherosclerotic lesions in both ApoE−/− and Ldr−/− mouse models by enhancing inflammation and foam cell formation.11,12

A number of studies in humans have established a direct association between Plg levels or plasmin activity and the incidence of coronary artery disease. As examples, 2 separate perspective cohort studies, FINRISK ‘92 Hemostasis Study13 and the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC),14 showed that Plg levels were an independent risk factor for coronary artery disease. A separate cohort study15 reported that the level of plasmin-α2-antiplasmin, a marker of plasmin generation, was directly associated with abnormal ankle-arm index, a measure of atherosclerosis. Other studies also confirm a direct correlation between blood levels of plasmin–α2 plasmin complex16 or fibrin D-dimer14,16,17 and coronary artery disease. The role of Plg in atherosclerosis has also been studied in Plg-deficient mice system.18–20 In the most recently published study, Kremen et al19 demonstrated that Plg knockout mice in an ApoE−/− background displayed a marked reduction in aortic lesion area. However, the mechanism by which Plg influenced lesion development remains unknown. Here, we present in vitro and in vivo studies that demonstrate that Plg is critical for transforming macrophages into lipid-laden foam cells. Surprisingly, this effect depends on alteration of expression of key genes associated with cholesterol accumulation into macrophages.

Methods

Animals

All animal experiments were performed under institutionally approved protocols. Tenth-generation male and female Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice4 in C57BL/6J were used, beginning at 8 to 10 weeks of age. ApoE−/− mice in C57BL/6J background were from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) and bred with Plg+/− mice to obtain ApoE−/−Plg+/+ and ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice. Male mice with <20% variation in weight among ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−Plg−/− genotypes were used. Four-week-old ApoE−/− and Plg−/−ApoE−/− mice were fed either a normal chow diet (CD) or a high-cholesterol diet (HCD; containing 0.15% added cholesterol and 42% milk fat, TD88137, Harlan-Teklad) for 6 weeks. Plg mutant mice in which the active-site Ser was replaced by Ala21 were kindly provided by Drs Ploplis and Castellino (University of Notre Dame). CD36−/− (10 times backcrossed to C57Bl/6) mice have previously been described.22

Ex Vivo and In Vivo Foam Cell Formation

Ex vivo foam cell formation was assessed with thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages and serum from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. In vivo foam cell formation was performed with ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice. Specific protocols for both assays are expanded in the online-only Data Supplement. The isolation and use of human blood monocyte–derived macrophages, THP-1, and RAW264.7 cell lines are explained in the online-only Data Supplement.

OxLDL Binding and Internalization

These assays using OxLDL fluorescently labeled with 1,1′-dioctadecyl-1-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (Dil, Biomedical Technologies, Inc) are described in the online-only Data Supplement.

In Vivo Transfer of Macrophages

This analysis is detailed in the online-only Data Supplement.

Real-Time Reverse Transcription–Polymerase Chain Reaction

Isolated RNA from variously treated cells was transcribed into cDNA. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed on cDNA with specific oligonucleotides (Table I in the online-only Data Supplement).

Western Blots

Total cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting (detailed in the online-only Data Supplement) using anti-CD36 antibody (R&D or Novus Biologicals).

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter Analysis

Cell surface expression of CD36 was analyzed by flow cytometry (detailed in the online-only Data Supplement) using FITC-labeled rat anti-mouse CD36 (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI).

Blood Cholesterol Quantification

Mice were fasted for 16 hours before blood collection from tail clips. Plasma from the mice was used to measure total LDL/very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) and high-density lipoprotein content with quantification kits from Biovision (Milpitas, CA).

Serum LTB4 Measurement

Serum LTB4 levels were quantified with a kit from Cayman Chemical.

Statistical Analysis

A 2-tailed t test was used in comparing 2 groups, and differences between multiple groups were evaluated with either a 1-way ANOVA or a 2-way ANOVA test followed by the Tukey multiple-comparison test (detailed in the online-only Data Supplement).

Results

Plg Regulates Macrophage Foam Cell Formation

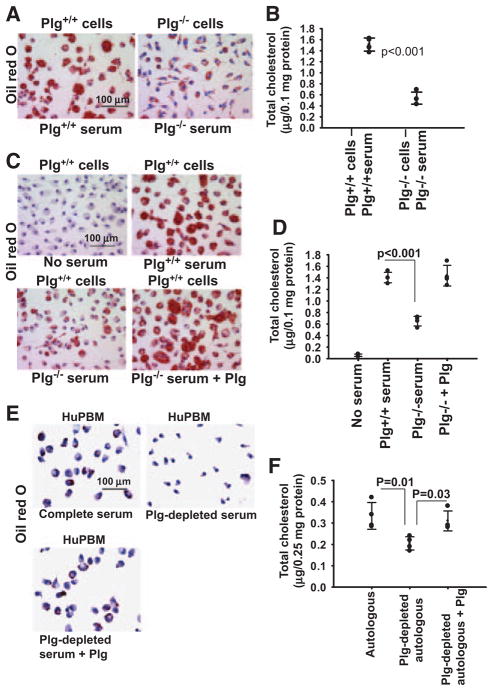

Plg was shown to support lipid core growth in a murine diet-induced atherosclerosis model.19,20 To dissect the mechanism for this proatherogenic activity, we assessed lipid uptake by thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice on exposure to OxLDL, culturing the cells in autologous serum. Lipid uptake, assessed by Oil Red O (ORO) staining, was dramatically impaired by macrophages derived from Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ mice (Figure 1A). Quantitatively, the reduction in total cholesterol in macrophages derived from Plg−/− mice was 62.5% (P<0.001) less than in wild-type (WT) macrophages (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Plasminogen (Plg) regulates lipid uptake by macrophages and foam cell formation. A through D, Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice were induced to form foam cell with oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) in the absence of serum or in the presence of serum derived from either Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice. E and F, Human monocyte–derived macrophages (HuPBMs) were induced to form foam cells by the addition of OxLDL and cultured in autologous serum or autologous serum depleted of Plg. In some murine or human cultures, Plg-deficient serum was supplemented with 1 μmol/L Glu-Plg. A, C, and E, Oil Red O staining of foam cells at original magnification ×40. Images are representative of 2 independent experiments. B, D, and F, Total cholesterol was measured in foam cells. Dots represent individual data points; the number of replicates is 4. Error bars are ±SD of the mean.

Mixing experiments were performed with macrophages derived from Plg+/+ mice cultured in serum derived from Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice. OxLDL induced no lipid accumulation in the absence of serum (Figure 1C and 1D). Macrophages cultured in Plg+/+ serum took up OxLDL and developed a rounded foam cell appearance (Figure 1C and 1D). In contrast, Plg+/+ macrophages cultured in Plg−/− serum displayed reduced ORO staining and cholesterol content (48.4% reduction; P<0.001) compared with the same (WT) macrophages cultured in Plg+/+ serum. The reduced ability of Plg−/− serum to support lipid uptake was restored when Glu-Plg was added at its physiological concentration (1 μmol/L4) to Plg−/− serum.

The influence of Plg on cholesterol accumulation also was observed with human monocyte–derived macrophages. In the presence of OxLDL, human monocyte–derived macrophages accumulated lipids when cultured in autologous serum as indicated by ORO staining (Figure 1E) and total cholesterol quantification (Figure 1F). Depletion of Plg from the serum on lysine-Sepharose lowered lipid accumulation by 49.1% (Figure 1F), and supplementing the depleted serum with Plg re-established cholesterol accumulation. A similar dependence of lipid uptake on Plg was observed with human monocytoid THP-1 cells (Figure IA in the online-only Data Supplement) and mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells (Figure IB in the online-only Data Supplement). The RAW264.7 cells cultured in only 1% Nutridoma still showed an increased lipid accumulation in response to OxLDL on addition of Plg.

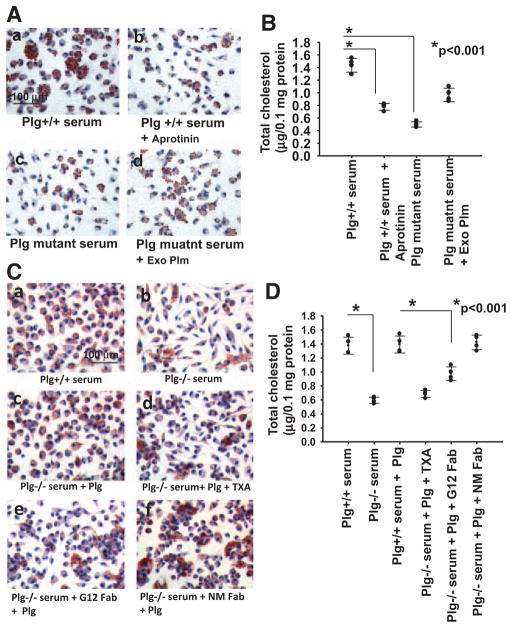

Functional Requirements for Plg-Mediated Foam Cell Formation

The requirement for proteolytic activity of plasmin in foam cell formation was evaluated by 2 approaches. First, aprotinin, a serine protease inhibitor, added to macrophages cultured in Plg+/+ serum (Figure 2A and 2B) inhibited cholesterol accumulation by 48.4% (P<0.001). Second, cholesterol accumulation by macrophages cultured in serum from mice expressing an active-site mutant of Plg,21 which is cleavable by Plg activators but does not form an active enzyme (Figure 2Ac and 2B), was suppressed by 67.7% compared with WT serum (P<0.001). Addition of exogenous Plg to the serum from Plg mutant mice enhanced ORO staining and cholesterol uptake (33% recovery; Figure 2Ad and 2B), but not as effectively as the addition of the same amount of Plg to Plg−/− serum (Figure 1C and 1D). This partial restoration of lipid uptake may reflect competition of mutant Plg with added WT Plg.

Figure 2.

Plasminogen (Plg) receptors and plasmin activity are required for Plg-mediated foam cell formation. A and B, Thioglycollate-elicited macrophages from Plg+/+ mice were untreated or treated with aprotinin (100 KIU/mL). The cells were then allowed to form foam cells by adding oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) in the presence of serum derived from Plg+/+ mice or Plg mutant mice (expressing active-site mutant of Plg). C and D, Tranexamic acid (TXA; 200 μmol/L), Fab fragments of anti-H2B monoclonal antibody (G12; 8 μmol/L), nonimmune mouse IgG Fab (NM; 8 μmol/L), or buffer was added to thioglycollate-elicited macrophages, and foam cell formation was induced with OxLDL. A and C, Oil Red O staining of foam cells at original ×40 magnification. Images are representative of 2 independent experiments. B and D, Total cholesterol was measured in the cultured macrophages. Each dot is 1 of 4 replicates; error bars are ±SD of the mean. Exo Plm indicates exogenous plasmin.

Many cellular functions of Plg depend on its interaction with Plg-Rs via its kringle-associated lysine binding sites, and tranexamic acid, a lysine analog, blocks Plg binding to most Plg-Rs on macrophages. The recovery of foam cell formation on the addition of Plg to macrophages cultured in Plg−/− serum (Figure 2Cc and 2D) was inhibited by >90% (P<0.001) by tranexamic acid (Figure 2Cd and 2D). Multiple Plg-Rs have been implicated in the binding of Plg to macrophages, and among these, histone H2B plays a particularly prominent in Plg binding.23 Fab fragments of the monoclonal antibody G12 raised to the C-terminal peptide of H2B (Figure 2C and 2D) inhibited the ability of Plg to enhance cholesterol accumulation by macrophages by 53% (P<0.001) compared with nonimmune Fab (Figure 2Cf and 2D). Hence, the ability of Plg to enhance foam cell formation is dependent on its interaction with the Plg-Rs. H2B does contribute and other Plg-Rs may contribute to this response.

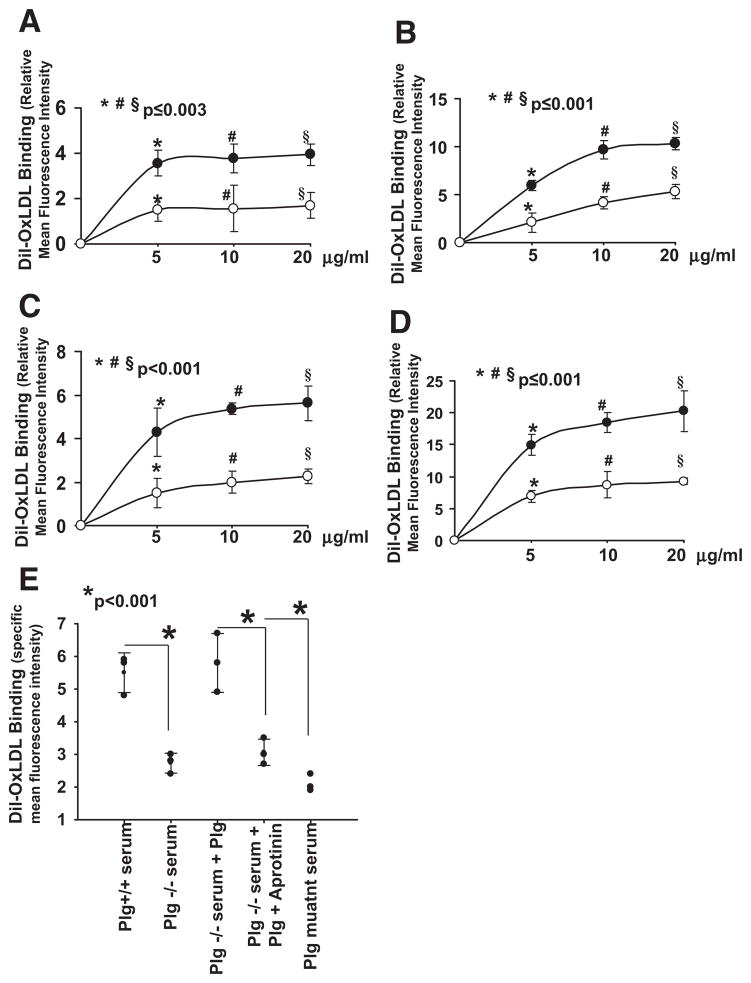

Plg Supports Binding and Internalization of OxLDL

To assess the effects of Plg on lipoprotein binding and/or internalization, thioglycollate-inflamed peritoneal macrophages were incubated with various concentrations of fluorescently tagged OxLDL (Dil-OxLDL) for 30 minutes at 4°C for binding and 2 hours at 37°C for internalization. By flow cytometry, macrophages from Plg−/− mice showed reduced binding (Figure 3A) and internalization (Figure 3B) compared with Plg+/+ macrophages. At 10 μg/mL, Plg−/−-derived macrophages bound 2.5-fold (P≤0.04) less and took up 1.7-fold (P≤0.001) less Dil-OxLDL than Plg−/− mice. Binding and uptake results were confirmed on WT macrophages cultured in serum derived from either Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice for 2 days. Both parameters were lowered (at 10 μg/mL Dil-OxLDL, 2-fold, P<0.001 for binding, and 2.2-fold, P≤0.003 for internalization) in macrophages cultured in Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ serum (Figure 3C and 3D).

Figure 3.

Role of plasminogen (Plg) in oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) binding and internalization. A and B, Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages derived from Plg+/+ (●) or Plg−/− (○)mice were allowed to bind (A; 30 minutes at 4°C) or to internalize (B; 2 hours at 37°C) Dil-OxLDL. C and D, Peritoneal macrophages from Plg+/+ mice were cultured in the presence of serum derived from Plg+/+ (●) or Plg−/− mice (○) and then allowed to bind (C) or to internalize (D) varying concentrations of Dil-OxLDL. Points are ±SD of means from triplicate samples. E, Macrophages derived from Plg+/+ mice were cultured in Plg+/+, Plg−/− serum, or serum from Plg active-site mutant mice. In some panels, Plg (1 μmol/L) or aprotinin (blocks plasmin activity) was added. Cells were washed and allowed to bind Dil-OxLDL in the presence or absence of excess unlabeled OxLDL. Bound or internalized Dil-OxLDL was measured by flow cytometry. Specific binding values are displayed and were obtained by subtracting residual nonspecific binding in the presence of excess OxLDL. Each dot is an average of triplicates.

To consider whether plasmin might modify OxLDL and aid in cholesterol accumulation, we cultured the macrophages in Plg+/+ or Plg−/− serum and then washed the cells thoroughly and measured Dil-OxLDL binding in the absence of Plg. Binding to cells cultured in the Plg−/− serum was still 50% less (P<0.001) than macrophages cultured in Plg+/+ serum (Figure 3E). Macrophages cultured in Plg−/− serum supplemented with exogenous Plg recovered their capacity to bind Dil-OxLDL, and inclusion of aprotinin with the exogenous Plg during culture inhibited this recovery. Additionally, macrophages cultured in serum from Plg mutant mice bound 62% less Dil-OxLDL (P<0.001) compared with macrophages cultured in Plg+/+ serum. These differences correlated well with cholesterol accumulation and foam cell formation (Figures 1 and 2).

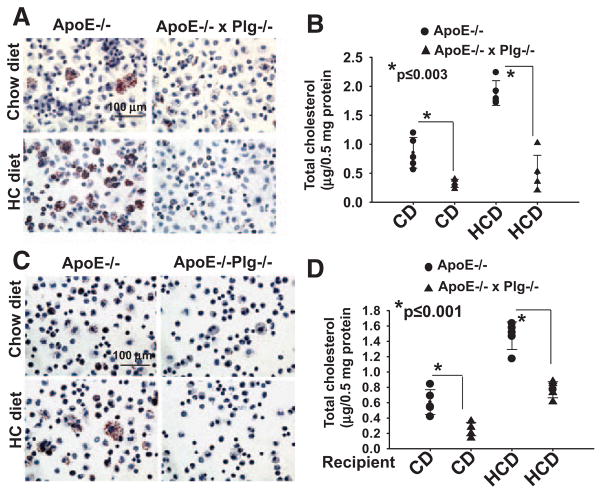

Foam Cell Formation In Vivo Is Impaired by the Absence of Plg

To translate our observations into an in vivo setting, we crossed the Plg−/− and ApoE−/− mice and maintained the resulting ApoE−/−Plg−/− and ApoE−/− mice on the CD or HCD. After 6 weeks, plasma LDL/VLDL was elevated in mice of both backgrounds fed the HCD compared with those fed the CD, and high-density lipoprotein was lower in ApoE−/− mice fed the HCD compared with those fed the CD (Table II in the online-only Data Supplement). Plasma LDL/VLDL levels were similar in the Plg-deficient and Plg-replete ApoE−/− backgrounds, but the high-density lipoprotein level was lower (P≤0.01) in Plg −/−ApoE−/− mice compared with ApoE−/− on both the CD and HCD (Table II in the online-only Data Supplement). Thioglycollate was used to recruit peritoneal macrophages in these mice, and equal numbers of cells were evaluated for lipid and total cholesterol content. Regardless of genotype, macrophages derived from mice fed the HCD showed increased lipid staining and a higher intracellular cholesterol than those fed the CD (Figure 4A and 4B). However, internal lipid staining and total cholesterol content were dramatically reduced in macrophages derived from ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice compared with ApoE−/− mice (Figure 4A and 4B). These differences in lipid accumulation in the Plg−/− background were observed in mice fed either the CD (60%; P≤0.003) or the HCD (68.3%; P≤0.003). Thus, cholesterol accumulation in macrophages in vivo is strongly influenced by Plg.

Figure 4.

Effect of plasminogen (Plg) deficiency on foam cell formation in vivo. A and B, Foam cells were measured in thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages derived from ApoE−/− or ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice fed either a chow diet (CD) or a high-cholesterol diet (HCD). C and D, Foam cell formation was assessed by macrophages transferred to ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−/Plg−/− recipient mice that had been fed a CD or an HCD. A and C, Oil Red O staining at an original ×40 magnification. Images are representative of cells from 5 mice. B and D, Quantification of total cholesterol. Each dot represents a data point from 1 of 5 mice. Error bars are the SD of the means.

We considered whether the observed in vivo differences in lipid accumulation might reflect differences in the macrophage populations recruited into the peritoneal cavity of ApoE−/− and Plg−/−ApoE−/− mice and performed macrophage transfer experiments.24 Thioglycollate-elicited macrophages derived from Plg+/+ mice were injected into the peritoneal cavity of recipient ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice that had been maintained on the CD or HCD for 6 weeks. Cells were recovered 3 days after thioglycollate stimulation and analyzed for lipid accumulation. Reduction of ORO staining (Figure 4C) and cholesterol content (42.1%, P≤0.001 on CD, and 48%, P≤0.001 on HCD; Figure 4D) were observed in transferred macrophages obtained from ApoE−/−Plg−/− recipient mice compared with ApoE−/− recipient mice. Additionally, levels of Plg in the peritoneal fluid were found to be the same in ApoE−/− mice on CD and mice on a high-fat diet (607.1 versus 586.5 ng/mL lavage; P>0.7). Plg was not detected in the lavage from ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice in either diet. Thus, the differences in cholesterol content of macrophages were consequences of both diet and Plg deficiency and were not due to differences in the population of recruited macrophages or to diet-associated differences in the peritoneal content of Plg. We also measured the levels of LDL/VLDL in the peritoneal lavage from these mice. In CD-fed mice, VLDL and LDL in the lavage were the same in ApoE−/− and ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice (38.2 versus 41.2 mg/mL in 1.5 mL peritoneal wash), yet these mice still showed a difference in foam cell formation (Figure 4C and 4D), supporting the direct role of Plg in lipid uptake. In the HCD-fed mice, a 2-fold difference in VLDL/LDL levels in the ApoE−/−Plg−/− compared with ApoE−/− mice (81 versus 38.1 mg/mL) was noted. Despite this difference in VLDL/LDL levels, the differences in cholesterol content were similar (42.1% and 48% reduction) in Plg−/− and Plg+/+ mice regardless of diet.

Plg Regulates the Expression of Genes Involved in Foam Cell Formation

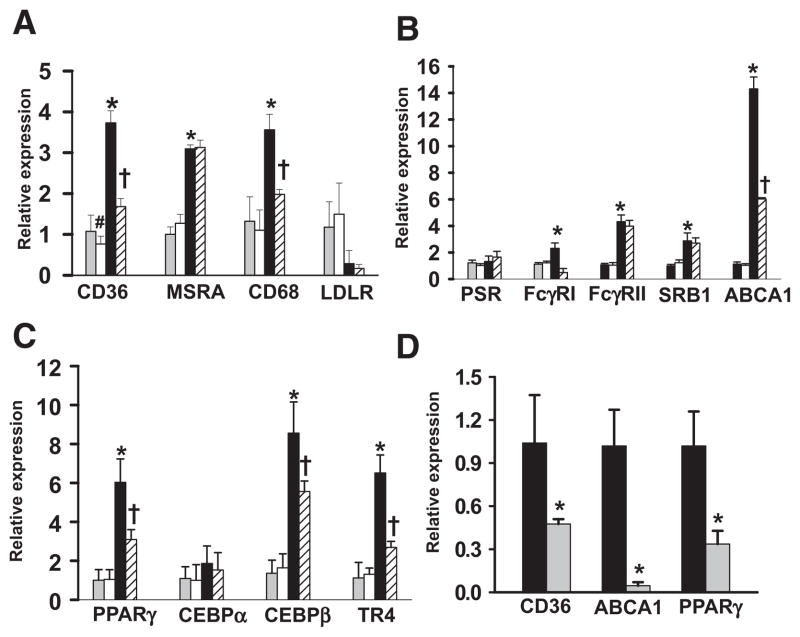

We next examined how Plg influences the expression of selected genes implicated in lipid metabolism. These included receptors involved in OxLDL uptake, CD36, MSRA and CD68; receptors involved in phagocytosis of OxLDL, immune complexes, and apoptotic bodies, represented by phosphatidylserine receptor, Fcγ receptor type 1, Fcγ receptor type II, SRB1, and ABCA1; and nuclear receptors known to regulate these receptors, including PPARγ, CEBPα, CEBPβ, and TR4.1,2,25,26 In the absence of OxLDL, no differences were observed in the expression levels of genes tested between cells cultured in Plg+/+ and Plg−/− conditions except CD36 (Figure 5A); CD36 expression was inhibited by 30% (P=0.04) in Plg−/− serum compared with Plg+/+ serum. Expression levels of tested genes were consistently higher on stimulation with OxLDL in macrophages cultured in Plg+/+ serum compared with unstimulated cells (P≤0.01). The exceptions were phosphatidylserine receptor and CEBPα (Figure 5B and 5C), which did not change on OxLDL stimulation. In the absence of Plg, OxLDL-mediated CD36 expression decreased by 57% (P=0.005) compared with Plg+/+ serum (Figure 5A). Among other genes, OxLDL-mediated CD68 (Figure 5A), Fcγ receptor type 1, and ABCA1 expression levels were significantly lower in the absence of Plg (Figure 5B). Among the nuclear receptors, OxLDL induced upregulation of transcripts for PPARγ, CEBPβ, and TR4 in macrophages, and all were suppressed in the Plg−/− environment (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Plasminogen (Plg) deficiency causes reduced expression of genes involved in lipid uptake. A through C, Real-time polymerase chain reaction quantification of transcripts of genes related to lipid uptake (A), phagocytosis (B), or nuclear receptors (C) on foam cells treated with either Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mouse–derived serum. Gray bars indicate Plg+/+ serum, oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) untreated; white bars, Plg−/− serum, OxLDL untreated; black bars, Plg+/+ serum, OxLDL treated; and striated bars, Plg−/− serum, OxLDL treated. Bars are mean±SD of triplicates. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments. *P≤0.01 vs Plg+/+ serum; #P=0.04 vs Plg+/+ serum; †P<0.002 vs Plg+/+ serum treated with OxLDL. D, Real-time polymerase chain reaction quantification on mRNA of transferred macrophages derived from hyperlipidemic ApoE−/− (black bars) and ApoE−/−Plg−/− (gray bars) recipient mice. Bars are mean±SD of triplicates. mRNAs are pooled from macrophages derived from 5 mice. ABCA1 indicates ATP-binding cassette transporter; CEBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; FcγRI, Fcγ receptor type 1; FcγRII, Fcγ receptor type II; and PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. *P<0.001 vs Plg+/+ serum treated with OxLDL.

The expression levels of the most effected genes were further evaluated in macrophages derived from in vivo transfer experiments. Transcript levels of CD36, ABCA1, and PPARγ were significantly suppressed (P≤0.01) in ApoE−/−Plg−/− recipient–derived macrophages compared with ApoE−/− recipient–derived macrophages (Figure 5D). Collectively, these results suggest that Plg might enhance macrophage accumulation of cholesterol by affecting the expression of various receptors involved in OxLDL uptake.

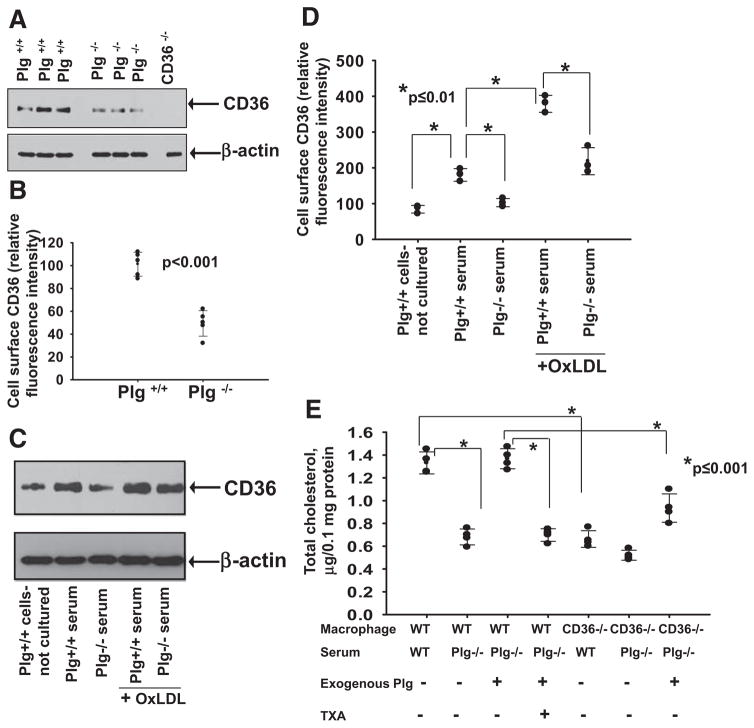

Role of CD36 in Plg-Mediated Cholesterol Accumulation

Among the scavenger receptors tested, CD36 expression was altered by the absence of Plg regardless of whether OxLDL was present (Figure 5A). At the protein level, Western blots of whole-cell lysates showed lower CD36 in macrophages from Plg−/− mice compared with Plg+/+ mice (Figure 6A). By flow cytometry, CD36 cell-surface levels were 2.2-fold (P<0.001) lower in macrophages from Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ mice (Figure 6B). The expression of CD36 depends on the differentiation status of macrophages.27 Plg+/+ mouse–derived macrophages cultured for 2 days in Plg+/+ serum showed a 2-fold higher CD36 protein expression than freshly isolated macrophages from Plg+/+ mice at both the whole-cell (Figure 6C) and cell-surface levels (Figure 6D). However, CD36 expression did not increase from basal levels when these cells were cultured for 2 days in Plg−/− serum. On OxLDL treatment, CD36 expression was enhanced 2-fold in Plg+/+ serum compared with untreated cells but inhibited by 45% when OxLDL-treated macrophages were cultured in Plg−/− serum (Figure 6C and 6D). These data suggest that CD36 gene and protein expression is regulated by Plg. Regulation of CD36 expression by Plg was confirmed with RAW264.7 cells grown in the absence of serum. When these cells were treated with 1 μmol/L Plg, their CD36 protein expression increased (Figure IIA in the online-only Data Supplement).

Figure 6.

Role of CD36 in plasminogen (Plg)-mediated foam cell formation. A, Western blot for CD36 (top) of macrophages derived from either Plg+/+ mice or Plg−/− mice. CD36−/− macrophages were analyzed as a negative control. B, Flow cytometry for cell surface CD36 of macrophages derived from either Plg+/+ mice (n=5) or Plg−/− mice (n=5). Each dot is a data point from 1 of 5 mice. Error bars are mean±SD. C and D, Western blot (C, top) and flow cytometry (D) for CD36 on either freshly isolated macrophages derived from Plg+/+ mice or macrophages cultured in Plg+/+ mouse–derived serum in either the absence or presence of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL). Dots are averages of triplicate values. Actin levels serve as loading controls (A and C, bottom). E, Total cholesterol quantification on OxLDL-treated macrophages from Plg+/+ mice or CD36−/− mice cultured in either Plg+/+ or Plg−/− serum in the absence or presence of Plg. Each dot is 1 of 4 replicates; error bars are the SD of the means. TXA indicates tranexamic acid.

CD36 was further implicated in Plg-mediated OxLDL uptake and cholesterol accumulation. When macrophages derived from CD36−/− mice were cultured in Plg−/− serum, they showed little accumulation of lipid in response to OxLDL (Figure 6E), and the addition of Plg did not rescue cholesterol accumulation in CD36−/− macrophages as it did with CD36+/+ cells (Figure 6E). Together, these data indicate that a major component of Plg-mediated foam cell formation is dependent on its regulation of CD36 expression.

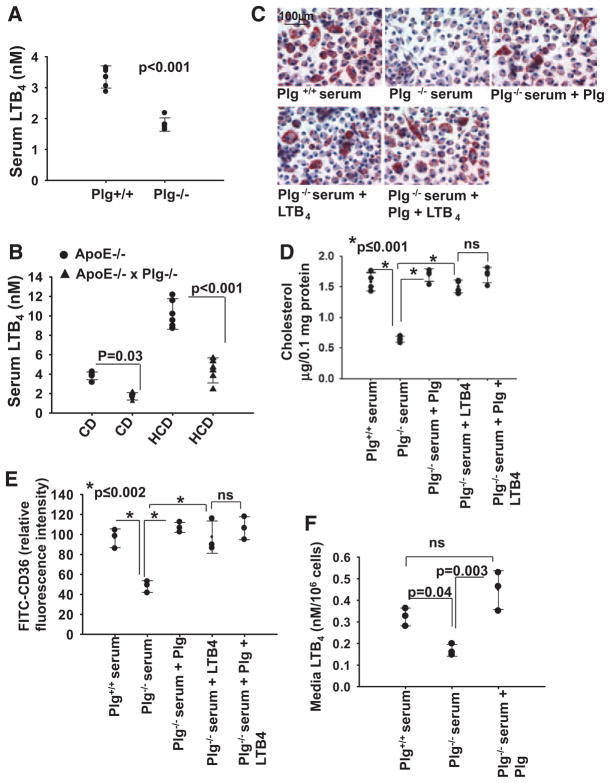

Effect of Plg on LTB4 Biosynthesis

LTB4 influences many crucial steps in early development of atherosclerosis,10−12 and Plg/plasmin induces monocyte production of several leukotrienes, including LTB4.9 We hypothesized that reduced LTB4 production could be a mechanism underlying Plg-dependent foam cell formation. We first quantified LTB4 levels in serum from Plg−/− and Plg+/+ mice (Figure 7A). Serum from Plg−/− mice contained 2-fold less LTB4 than serum from Plg+/+ mice (1.8±0.2 versus 3.3±0.4 nmol/L; n=5; P<0.001). LTB4 levels were also measured in ApoE−/− mice. LTB4 levels were 2.3-fold higher (P <0.001) in ApoE−/− mice fed the HCD compared with animals fed the CD for 6 weeks (Figure 7B), consistent with previous reports.28 Most notably, in ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice, LTB4 levels in serum were ≈40% lower in both CD-fed mice (1.7±0.4 nmol/L in ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice versus 3.8±0.4 nmol/L in ApoE−/−Plg+/+ mice; n=5; P=0.03) and HCD-fed mice (4.4±1.2 nmol/L in ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice versus 10.2±1.6 nmol/L in ApoE−/−Plg+/+ mice; n=5; P<0.001; Figure 7B). Additionally, in ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice, LTB4 levels in peritoneal fluid were 46% lower (0.06 versus 0.1 nmol/L in CD-fed mice and 0.2 nmol/L versus 0.4 nmol/L in HCD-fed mice) compared with ApoE−/− mice. Thus, Plg influences LTB4 production in vivo.

Figure 7.

Relationship between plasminogen (Plg), leukotriene B4 (LTB4), and foam cell formation. A, Serum LTB4 levels in thioglycollate-treated Plg+/+ and Plg−/− mice. B, Serum LTB4 levels in ApoE−/− mice or Plg−/−ApoE−/− mice maintained on a high-cholesterol diet (HCD) or a chow diet (CD). Error bars are mean±SD from 5 mice. C through E, Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) induced foam cell formation by thioglycollate-elicited macrophages in Plg+/+ serum or Plg−/− serum with or without added Plg (1 μmol/L) and LTB4 (500 nmol/L). C, Oil Red O staining (original magnification ×40). Images are representative of 2 independent experiments. D, Total cholesterol quantification. Each dot is the data point from 1 of 4 individual wells. Error bars are the SD of means. E, Flow cytometry for surface CD36 expression. Bars are mean fluorescence intensities ±SD of triplicates. F, Plg+/+ mouse–derived macrophages were cultured in serum derived from Plg+/+ or Plg−/− mice in the absence or presence of Plg. Culture media were collected and LTB4 levels measured. Each dot is the value for 3 independent experiments. Error bars are ±SD of means.

LTB4 Bypasses the Effects of Plg Deficiency on Foam Cell Formation and Gene Expression

Thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages were presented with OxLDL in Plg+/+ or Plg−/− serum (Figure 7C and 7D) with or without supplemental Plg or LTB4. The addition of Plg or LTB4 overcame the suppressive effects of Plg deficiency (Figure 7C and 7D). As noted, macrophages grown in Plg−/− serum have less CD36 on their surface than macrophages in Plg+/+ serum. The addition of either Plg or LTB4 (500 nmol/L)29 to the Plg−/− serum enhanced cell-surface expression of CD36 (Figure 7E and Figure IIB in the online-only Data Supplement). Adding Plg and LTB4 together to Plg−/− serum did not have an additional effect on ORO staining (Figure 7C), cholesterol accumulation (Figure 7D), or CD36 expression (Figure 7E and Figure IIB in the online-only Data) compared with LTB4 alone, suggesting that LTB4 is a downstream effector of Plg. When Plg was added to Plg−/− culture media, LTB4 levels were fully recovered (Figure 7F).

5-LO–catalyzed LTB4 synthesis requires an integral membrane protein, 5-LO activating protein. MK886 blocks LTB4 secretion by inhibiting 5-LO activating protein activity.30 When RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with MK886 and then with Plg, Plg-mediated upregulation of CD36 protein expression was completely suppressed at 500 nmol/L MK886 (Figure IIB in the online-only Data Supplement). LTB4 can signal intracellularly or by binding to the G-protein–coupled receptors BLT1 and BLT2. Blocking BLT1 (the higher-affinity LTB4 receptor) with 2 unrelated inhibitors, LY293111 and U-75302, reduced Plg-mediated CD36 expression (75% with LY293111 and >90% with U-75302; Figure III in the online-only Data Supplement), suggesting that Plg-induced LTB4 acts primarily via its extracellular release and interaction with BLT1. In addition to LTB4, Plg induces biosynthesis of cysteinyl-LTs 9. Adding LTE4, the most stable of the cysteinyl-LTs, did not enhance CD36 expression in RAW264.7 cells (Figure IV in the online-only Data Supplement), suggesting that between these 2 leukotrienes, the effect of Plg on CD36 expression depends on LTB4.

Discussion

It is now clear that the role of Plg in vivo extends well beyond its function in fibrinolysis. By virtue of its capacity to degrade various extracellular matrix proteins, to activate certain MMPs, and to cleave secreted growth factors, Plg facilitates tissue reorganization and enhances cell migration.3,5,6 In the present study, we report an unexpected effect of Plg on the capacity of macrophages to take up lipids and become foam cells. Surprisingly, Plg exerts these effects by controlling the expression of genes involved in OxLDL uptake by macrophages, most notably CD36, and this regulation is dependent on Plg-dependent activation of the 5-LO biosynthetic pathway. Thus, we have assigned a novel function to Plg in macrophage biology and have begun to define the molecular pathway underlying this function.

The importance of Plg in cholesterol accumulation was demonstrated with primary cells and cell lines of murine (peritoneal macrophages and RAW264.7 cells) and human (human monocyte–derived macrophages and THP-1) origin. With all these cells, culture in absence of Plg reduced ORO staining and cholesterol content in response to OxLDL compared with presence of Plg, and supplementing the Plg-deficient media with exogenous Plg overcame this suppression. Decreased cholesterol accumulation by macrophages under Plg-deficient conditions was very extensive (eg, cholesterol accumulation was reduced by 60% in macrophages from Plg−/−ApoE−/− mice compared with those derived from Plg+/+ApoE−/− mice). The pathway giving rise to residual cholesterol uptake in the absence of Plg is unknown. SRA1 expression was unaffected by the absence of Plg but was induced by OxLDL, and it is a candidate for mediating Plg-independent cholesterol accumulation. Growth factors such as insulin31 and many cytokines like interleukin-1032 also support foam cell formation and could contribute to Plg-independent lipid uptake. The molecular and cellular requirements for fat cell formation during adipogenesis often parallel those for macrophage transformation into foam cells. Hints about a possible role for Plg in lipid uptake can be derived from 2 prior studies of adipogenesis. Selvarajan et al33 described a role for Plg in lipid absorption during preadipocyte differentiation to adipocytes, and Hoover-Plow et al34 demonstrated reduced body weight and less accumulation of fat in Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ mice. Thus, the influence of Plg on lipid uptake may not be restricted to macrophages.

Correlating with Plg-dependent changes in cholesterol accumulation, binding and internalization of OxLDL were also impaired in the absence of Plg. In 1 arm of these studies, the Dil-OxLDL tracer was not directly exposed to Plg, yet macrophages cultured in Plg-deficient culture conditions showed reduced binding. These data suggest that the primary role of Plg is to affect the capacity of the macrophages to take up OxLDL rather than to modify the OxLDL ligand. Nevertheless, we do not exclude the possibility that plasmin may modify OxLDL over the 24 to 48 hours of the foam cell formation assays. Consistent with binding data among the tested scavenger receptors, mRNA and protein levels of the CD36 molecule were significantly suppressed in macrophages derived from Plg−/− mice compared with Plg+/+ mice or in WT macrophages cultured in Plg−/− serum. CD36 accounts for almost 80% of foam cell formation by OxLDL generated by a myeloperoxidase-hydrogen peroxide-nitrite pathway35 and 60% of OxLDL generated by copper oxidation.22 Furthermore, studies of hypercholesterolemic CD36−/− mice have shown the importance of this receptor in uptake of OxLDL and foam cell formation.22 We verified the role of CD36 in Plg-dependent foam cell formation using macrophages from CD36 knockout mice. The addition of exogenous Plg to Plg-deficient medium, which fully rescued cholesterol accumulation in WT macrophages, had little effect on CD36 knockout macrophages.

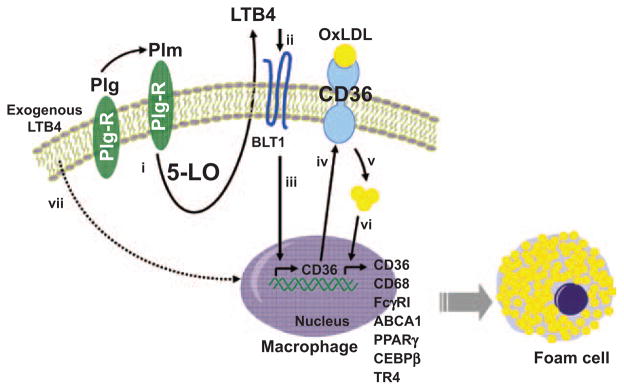

5-LO and its product, LTB4, have been implicated in CD36 expression.12 We found a reduced level of LTB4 in serum from thioglycollate-treated Plg−/− compared with Plg+/+ mice. This influence of Plg in LTB4 biosynthesis was also substantiated in proatherogenic ApoE−/− mice, in which reduced LTB4 levels were observed in serum of ApoE−/−Plg−/− mice compared with ApoE−/− mice. Of particular note, we found that the addition of LTB4 to Plg-deficient cultures overcame the reduction in cholesterol accumulation by macrophages. The effects of Plg and LTB4 on cholesterol accumulation and CD36 expression suggest that these molecules function in the same pathway because LTB4+Plg did not have an additive effect. Additionally, Plg-mediated CD36 expression required BLT1, a high-affinity LTB4 receptor. These data support the model depicted in Figure 8. Accordingly, Plg and plasmin bind to receptors, including but not limited to H2B. Plasmin stimulates 5-LO activity, which in turn generates LTB4. LTB4, in part by releasing from the cell and engaging its high-affinity receptor, BLT1, generates nuclear signals that enhance CD36 mRNA levels, protein, and cell-surface expression. The present study does not establish how Plg activates the 5-LO pathway to induce CD36 expression. Activation of 5-LO can be mediated by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation,36 and plasmin is known to be a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activator.7 LTB4 also can activate the intracellular nuclear factors PPARα and weakly PPARγ, but these nuclear factors do not support foam cell formation.37 Plasmin-induced leukotriene secretion and chemotaxis have been shown to be sensitive to pertussis toxin,7 which supports our suggestion that LTB4 signals via binding to BLT1, a G-protein–coupled receptor. Although our model suggests that released LTB4 exerts its effects on the expression of CD36 on the same cell, released LTB4 may stimulate other macrophages or other cells sensitive to LTB4. LTB4 but not LTE4 enhanced CD36 expression, but other products of Plg-induced signaling may exert other far-reaching effects.

Figure 8.

The plasminogen (Plg)-dependent pathway of foam cell formation. Plg binding to Plg receptors (Plg-Rs) activates 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) in a plasmin (Plm)-dependent manner and leads to leukotriene B4 (LTB4) production and secretion by the macrophage (i). Secreted LTB4 binds to BLT1 (ii) and activates transcription of the CD36 gene (iii), CD36 protein synthesis, and translocation to the cell membrane (iv). The increased expression of CD36 facilitates uptake of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (OxLDL) and accumulation of cholesterol within the cells (v). The accumulated sterols induce a positive feedback loop for further cholesterol accumulation by enhancing the expression many relevant genes, including those for scavenger and phagocytic receptors and for the transcription factors that regulate these genes (vi). The Plg dependence of this pathway for CD36 expression and foam cell formation can be bypassed by exogenous LTB4 (vii). This pathway shows the actions of Plg on a single cell, but released LTB4 may affect adjacent cells. ABCA1 indicates ATP-binding cassette transporter; CEBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; FcγRI, Fcγ receptor type 1; FcγRII, Fcγ receptor type II; and PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Kremen et al19 demonstrated that Plg deficiency markedly reduced atherosclerosis lesion growth, an observation entirely consistent with our data. In contrast, Xiao et al18 suggested that Plg deficiency accelerated lesion development. In the Kremen et al study, mice were fed an atherogenic diet; in the Xiao et al study, they were fed a low-fat diet. However, our data showed a diet-independent effect of Plg in macrophage foam cell formation in ApoE−/− mice. In the studies by Xiao et al and Kremen et al, the lesions were observed at different stages of development (15 weeks in the former and 18–25 weeks in the latter study). Plg exerts numerous effects in vivo, and its proatherogenic activities (eg, enhanced ingress of inflammatory cells or enhanced lipid uptake) may dominate its antiatherogenic effects (eg, turnover of extracellular matrix or cytokines) at different stages of lesion development. Such counterbalancing effects of Plg may have contributed to the absence of a significant benefit of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy on the incidence of mortality and nonfatal myocardial infarction in patients with unstable angina or non–ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction;38 the effects of Plg on foam cell formation and accelerated atherosclerosis may have offset the benefits of thrombolysis.

Conclusions

Plg is a key regulator of foam cell formation. Inactivation of Plg reduces OxLDL-driven foam cell formation by reducing the biosynthesis of LTB4, reducing the expression of CD36, and suppressing OxLDL-driven expression of multiple genes involved in foam cell formation. The combination of these effects identifies a prominent role of Plg in atherogenesis. These findings provide a molecular explanation for the association of Plg with coronary artery disease and provide an impetus to further explore Plg-mediated lipid metabolism and to consider Plg and Plg-Rs as targets for therapeutic intervention in cardiovascular disease.

Supplementary Material

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVE.

There is an extensive body of literature, including data from large prospective trials, that associates the levels of plasminogen, plasmin:antiplasmin complexes (a reflection of plasminogen activation), and fibrin degradation products (the products of plasmin action) with coronary artery disease, and murine models support the influence of plasminogen deficiency on atherosclerosis. Here, we provide insights into a direct mechanism by which plasminogen influences atherogenesis. In the absence of plasminogen, macrophages, of either human or murine origin, take up substantially less lipid, and their foam cell formation is markedly suppressed. This transformation to foam cells, a hallmark of atherosclerosis, is shown to be dependent on the proteolytic activity generated from plasminogen and on the interaction of plasmin with the macrophage surface. This interaction turns on expression of the gene for CD36; hence, cell-surface expression of CD36, the major receptor for uptake of oxidized phospholipids, is dampened in plasminogen-deficient conditions. The pathway by which plasminogen controls CD36 gene expression is dependent on its activation of 5-lipoxigenase and generation of leukotriene B4, known effectors of atherogenesis in vivo. Leukotriene B4 released from plasmin-stimulated macrophages binds to its high-affinity receptor and triggers expression of the CD36 gene. These results identify a basic mechanism by which plasminogen regulates a macrophage function that is an essential component of atherogenesis, provides an explanation for the association of plasminogen with cardiovascular disease, and may open up new approaches to consider in the treatment of atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Timothy Burke for technical assistance, Drs Judy Drazba and John Peterson for help with microscopy, and Colin O’Rourke for biostatistical analyses.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL017964 to Dr Plow and American Heart Association Scientist Development grant 11SDG7390041 to Dr Das.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Glass CK, Witztum JL. Atherosclerosis: the road ahead. Cell. 2001;104:503–516. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shashkin P, Dragulev B, Ley K. Macrophage differentiation to foam cells. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3061–3072. doi: 10.2174/1381612054865064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plow EF, Herren T, Redlitz A, Miles LA, Hoover-Plow JL. The cell biology of the plasminogen system. FASEB J. 1995;9:939–945. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.10.7615163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ploplis VA, Carmeliet P, Vazirzadeh S, Van Vlaenderen I, Moons L, Plow EF, Collen D. Effects of disruption of the plasminogen gene on thrombosis, growth, and health in mice. Circulation. 1995;92:2585–2593. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.9.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miles LA, Hawley SB, Baik N, Andronicos NM, Castellino FJ, Parmer RJ. Plasminogen receptors: the sine qua non of cell surface plasminogen activation. Front Biosci. 2005;10:1754–1762. doi: 10.2741/1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Plow EF, Hoover-Plow J. The functions of plasminogen in cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Syrovets T, Simmet T. Novel aspects and new roles for the serine protease plasmin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:873–885. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3348-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laumonnier Y, Syrovets T, Burysek L, Simmet T. Identification of the annexin A2 heterotetramer as a receptor for the plasmin-induced signaling in human peripheral monocytes. Blood. 2006;107:3342–3349. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weide I, Römisch J, Simmet T. Contact activation triggers stimulation of the monocyte 5-lipoxygenase pathway via plasmin. Blood. 1994;83:1941–1951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poeckel D, Funk CD. The 5-lipoxygenase/leukotriene pathway in preclinical models of cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:243–253. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aiello RJ, Bourassa PA, Lindsey S, Weng W, Freeman A, Showell HJ. Leukotriene B4 receptor antagonism reduces monocytic foam cells in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:443–449. doi: 10.1161/hq0302.105593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subbarao K, Jala VR, Mathis S, Suttles J, Zacharias W, Ahamed J, Ali H, Tseng MT, Haribabu B. Role of leukotriene B4 receptors in the development of atherosclerosis: potential mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:369–375. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000110503.16605.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajecki M, Pajunen P, Jousilahti P, Rasi V, Vahtera E, Salomaa V. Hemostatic factors as predictors of stroke and cardiovascular diseases: the FINRISK ‘92 Hemostasis Study. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2005;16:119–124. doi: 10.1097/01.mbc.0000161565.74387.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folsom AR, Aleksic N, Park E, Salomaa V, Juneja H, Wu KK. Prospective study of fibrinolytic factors and incident coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:611–617. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakkinen PA, Cushman M, Psaty BM, Rodriguez B, Boineau R, Kuller LH, Tracy RP. Relationship of plasmin generation to cardiovascular disease risk factors in elderly men and women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:499–504. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morange PE, Bickel C, Nicaud V, Schnabel R, Rupprecht HJ, Peetz D, Lackner KJ, Cambien F, Blankenberg S, Tiret L AtheroGene Investigators. Haemostatic factors and the risk of cardiovascular death in patients with coronary artery disease: the AtheroGene study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2793–2799. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000249406.92992.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koenig W, Rothenbacher D, Hoffmeister A, Griesshammer M, Brenner H. Plasma fibrin D-dimer levels and risk of stable coronary artery disease: results of a large case-control study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1701–1705. doi: 10.1161/hq1001.097020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao Q, Danton MJ, Witte DP, Kowala MC, Valentine MT, Bugge TH, Degen JL. Plasminogen deficiency accelerates vessel wall disease in mice predisposed to atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10335–10340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kremen M, Krishnan R, Emery I, Hu JH, Slezicki KI, Wu A, Qian K, Du L, Plawman A, Stempien-Otero A, Dichek DA. Plasminogen mediates the atherogenic effects of macrophage-expressed urokinase and accelerates atherosclerosis in apoE-knockout mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17109–17114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808650105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwaki T, Donahue DL, Sandoval-Cooper MJ, Castellino FJ, Ploplis VA. A plasminogen deficiency attenuates atherosclerosis as a result of altered lipoprotein processing [abstract]. Presented at: International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis XXII Congress; Boston, Massachusetts. July 11–16, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwaki T, Malinverno C, Smith D, Xu Z, Liang Z, Ploplis VA, Castellino FJ. The generation and characterization of mice expressing a plasmin-inactivating active site mutation. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2341–2344. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03995.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Febbraio M, Podrez EA, Smith JD, Hajjar DP, Hazen SL, Hoff HF, Sharma K, Silverstein RL. Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1049–1056. doi: 10.1172/JCI9259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Das R, Burke T, Plow EF. Histone H2B as a functionally important plasminogen receptor on macrophages. Blood. 2007;110:3763–3772. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ploplis VA, French EL, Carmeliet P, Collen D, Plow EF. Plasminogen deficiency differentially affects recruitment of inflammatory cell populations in mice. Blood. 1998;91:2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Osterud B, Bjorklid E. Role of monocytes in atherogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:1069–1112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00005.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie S, Lee YF, Kim E, Chen LM, Ni J, Fang LY, Liu S, Lin SJ, Abe J, Berk B, Ho FM, Chang C. TR4 nuclear receptor functions as a fatty acid sensor to modulate CD36 expression and foam cell formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13353–13358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905724106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huh HY, Pearce SF, Yesner LM, Schindler JL, Silverstein RL. Regulated expression of CD36 during monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation: potential role of CD36 in foam cell formation. Blood. 1996;87:2020–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doi K, Hamasaki Y, Noiri E, Nosaka K, Suzuki T, Toda A, Shimizu T, Fujita T, Nakao A. Role of leukotriene B4 in accelerated hyperlipidaemic renal injury. Nephrology (Carlton) 2011;16:304–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López-Parra M, Titos E, Horrillo R, Ferré N, González-Périz A, Martínez-Clemente M, Planagumà A, Masferrer J, Arroyo V, Clària J. Regulatory effects of arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase on hepatic microsomal TG transfer protein activity and VLDL-triglyceride and apoB secretion in obese mice. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2513–2523. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800101-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu S, McKeever BM, Wisniewski D, Miller DK, Spencer RH, Chu L, Ujjainwalla F, Yamin TT, Evans JF, Becker JW, Ferguson AD. Expression, purification and crystallization of human 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein with leukotriene-biosynthesis inhibitors. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2007;63(pt 12):1054–1057. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107055571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Park YM, Kashyap RS, Major AJ, Silverstein RL. Insulin promotes macrophage foam cell formation: potential implications in diabetes-related atherosclerosis. Lab Invest. 2012;92:1171–1180. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halvorsen B, Waehre T, Scholz H, Clausen OP, von der Thüsen JH, Müller F, Heimli H, Tonstad S, Hall C, Frøland SS, Biessen EA, Damås JK, Aukrust P. Interleukin-10 enhances the oxidized LDL-induced foam cell formation of macrophages by antiapoptotic mechanisms. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:211–219. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400324-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Selvarajan S, Lund LR, Takeuchi T, Craik CS, Werb Z. A plasma kallikrein-dependent plasminogen cascade required for adipocyte differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:267–275. doi: 10.1038/35060059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoover-Plow J, Ellis J, Yuen L. In vivo plasminogen deficiency reduces fat accumulation. Thromb Haemost. 2002;87:1011–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podrez EA, Febbraio M, Sheibani N, Schmitt D, Silverstein RL, Hajjar DP, Cohen PA, Frazier WA, Hoff HF, Hazen SL. Macrophage scavenger receptor CD36 is the major receptor for LDL modified by monocyte-generated reactive nitrogen species. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:1095–1108. doi: 10.1172/JCI8574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Werz O, Klemm J, Samuelsson B, Rådmark O. 5-Lipoxygenase is phosphorylated by p38 kinase-dependent MAPKAP kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5261–5266. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050588997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li AC, Binder CJ, Gutierrez A, Brown KK, Plotkin CR, Pattison JW, Valledor AF, Davis RA, Willson TM, Witztum JL, Palinski W, Glass CK. Differential inhibition of macrophage foam-cell formation and atherosclerosis in mice by PPARalpha, beta/delta, and gamma. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1564–1576. doi: 10.1172/JCI18730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Anderson HV, Cannon CP, Stone PH, Williams DO, McCabe CH, Knatterud GL, Thompson B, Willerson JT, Braunwald E. One-year results of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) IIIB clinical trial: a randomized comparison of tissue-type plasminogen activator versus placebo and early invasive versus early conservative strategies in unstable angina and non-Q wave myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1643–1650. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00404-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.