Abstract

Acute lung injury (ALI) is a complex syndrome with many aetiologies, resulting in the upregulation of inflammatory mediators in the host, followed by dyspnoea, hypoxemia and pulmonary oedema. A central mediator is inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) that drives the production of NO and continued inflammation. Thus, it is useful to have diagnostic and therapeutic agents for targeting iNOS expression. One general approach is to target the precursor iNOS mRNA with antisense nucleic acids. Peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) have many advantages that make them an ideal platform for development of antisense theranostic agents. Their membrane impermeability, however, limits biological applications. Here, we report the preparation of an iNOS imaging probe through electrostatic complexation between a radiolabelled antisense PNA-YR9 · oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) hybrid and a cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle (cSCK). The Y (tyrosine) residue was used for 123I radiolabelling, whereas the R9 (arginine9) peptide was included to facilitate cell exit of untargeted PNA. Complete binding of the antisense PNA-YR9 · ODN hybrid to the cSCK was achieved at an 8 : 1 cSCK amine to ODN phosphate (N/P) ratio by a gel retardation assay. The antisense PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes efficiently entered RAW264.7 cells, whereas the PNA-YR9 · ODN alone was not taken up. Low concentrations of 123I-labelled antisense PNA-YR9 · ODN complexed with cSCK showed significantly higher retention of radioactivity when iNOS was induced in lipopolysaccharide+interferon-γ-activated RAW264.7 cells when compared with a mismatched PNA. Moreover, statistically, greater retention of radioactivity from the antisense complex was also observed in vivo in an iNOS-induced mouse lung after intratracheal administration of the nanocomplexes. This study demonstrates the specificity and sensitivity by which the radiolabelled nanocomplexes can detect iNOS mRNA in vitro and in vivo and their potential for early diagnosis of ALI.

Keywords: cationic nanoparticles, acute lung injury, peptide nucleic acid, inducible nitric oxide synthase, radiolabelling, targeting

1. Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) is an inflammation-induced, heterogeneous lung injury syndrome characterized by hypoxemia and pulmonary oedema that is associated with the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome. ALI is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, indicating the need for improved diagnosis and treatment strategies [1]. Mediators commonly upregulated in ALI include inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS, NOSII), an enzyme abundant in activated lung macrophages, lung epithelial and endothelial cells. Inflammatory mediators such as interleukin-1 and interferon-γ may activate the expression of iNOS in macrophages, resulting in the production of nitric oxide (NO). NO is a double-edged sword, however, a dominant effect is pro-inflammatory resulting in tissue damage [2,3]. The inhibition of iNOS has been shown to reduce the accumulation of NO and improve the outcome of ALI in experimental models [4].

The prominent role of iNOS in ALI has spurred efforts towards developing iNOS protein probes and inhibitors for diagnosis and therapy, respectively [5–9]. An alternative strategy is to develop probes and inhibitors for the iNOS mRNA transcript that can be readily targeted by complementarily base pairing with an antisense oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN) or analogue [10–12]. Studies that show direct and specific targeting of iNOS mRNA both in vitro and in vivo are limited. Our work and that of others have shown that peptide nucleic acid (PNA) has a number of useful properties that make it an ideal choice for targeting candidate mRNA [13–19].

PNA, a synthetic analogue of DNA [20], is an ideal platform for the development of antisense diagnostic agents owing to its high resistance to enzymatic degradation, high affinity for RNA, ability to invade regions of secondary structure and inability to activate RNase H, which would otherwise degrade the target mRNA sequence and lead to signal loss [13,15,16,21–23]. Although PNAs have been used in many biological applications as biosensors and imaging agents [14,18], poor membrane permeability and rapid clearance have limited its in vitro and in vivo applications [22,24]. Numerous attempts have been made to improve the permeability of PNAs, including conjugation to cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) [25,26], lipids [27,28] and other ligands [29]. While these methods have shown the ability to improve PNA cellular uptake, the PNA often ends up being trapped in endosomes [30], and non-internalized PNA is rapidly excreted. One approach to overcome these challenges is to use nanoparticles that have improved cellular uptake, endosomal escape and pharmacokinetic properties for PNA delivery [31–33].

Studies of nanoparticles as delivery vehicles for antisense ODNs, siRNAs, DNAs and PNAs both in vitro and in vivo [32,34–40] have demonstrated their ability to overcome delivery barriers, including endosomal trapping and rapid clearance [35,41]. We have previously used shell-cross-linked knedel-like (SCK) nanoparticles for a range of biomedical applications [42]. Cationic SCK (cSCK) consists of a hydrophobic core and a positively charged, highly functionalizable hydrophilic cross-linked shell [43], which could greatly facilitate gene and ODN transfection in mammalian cells [44], and efficiently deliver PNAs into cells either through electrostatic complexation with a PNA · ODN hybrid or a bioreductively cleavable disulfide linkage [33].

Herein, we report specific in vitro and in vivo targeting of iNOS mRNA with an antisense nanocomplex, 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK, formulated by electrostatic complexation of a cSCK and a radiolabelled antisense 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti hybrid (figure 1). The particular PNA used showed high binding affinity to iNOS mRNA [40] as well as anti-iNOS activity [45]. The Y (tyrosine) of the PNA allowed radiolabelling with 123I, and the R9 (arginine9) group was used to attempt to facilitate endosomal, lysosomal and cellular escape of untargeted PNA probe. We found that the radiolabelled antisense PNA showed selective retention in both iNOS-expressing cells in vitro and in mouse lung in comparison with the nanocomplexes prepared with mismatched PNA. In particular, the specificity in cell culture improved with a decrease in the dose, suggesting that it was important to control the extent of target mRNA saturation with probe. In vivo targeting of iNOS similarly suggested the potential benefit of nanoparticle-mediated probe delivery and the importance of high specific activity.

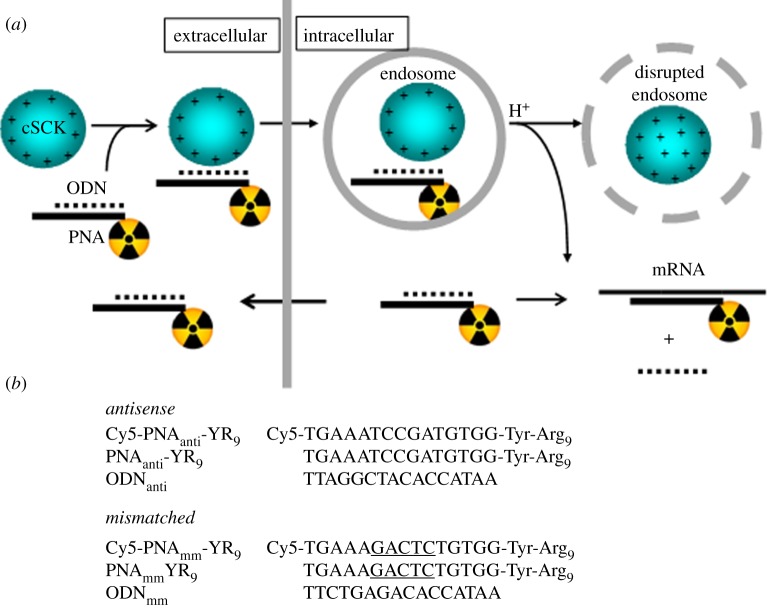

Figure 1.

cSCK nanoparticle-mediated delivery of radiolabelled antisense PNAs into cell. (a) Scheme showing formation of an electrostatic nanocomplex between the cationic cSCK and a negatively charged radiolabelled PNA · ODN hybrid. The nanocomplex is then endocytosed and neutralizes protons during endosomal acidification causing membrane disruption by the proton sponge effect thereby releasing the PNA· ODN hybrid. Once the sticky end of the ODN (the ‘toehold’) locates the target mRNA sequence, the ODN strand becomes displaced, and the radiolabelled PNA binds with high affinity. Exit of excess or non-targeted PNA is facilitated by the presence of the Arg9 peptide that has known cell-penetrating properties. (b) Sequences used in this study. PNAmmYR9 is a mismatched sequence that is otherwise identical to the antisense PNAantiYR9 except that the central five bases are mismatched.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

All solvents and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification, unless otherwise indicated. N-Hydroxybenzotriazole H2O (HOBT) and 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU) were purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. The amphiphilic block copolymer, poly(acrylic acid)60-block-polystyrene30 (PAA60-b-PS30), was prepared according to literature [33], and transformed into poly(acrylamidoethylamine)160-block-polystyrene30 (PAEA160-b-PS30) for the preparation of the cSCKs [44]. CellTiter 96 non-radioactive cell proliferation assay was purchased from Promega.

2.2. Measurements

1H-NMR and 13C-NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 300 MHz spectrometer. IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum BX FT-IR system. N,N-Dimethylformamide-based gel permeation chromatography (DMF-GPC) was conducted on a Waters system equipped with an isocratic pump model 1515, a differential refractometer model 2414 and a two column set of Styragel HR 4 and HR 4E 5 µm DMF 7.8 × 300 mm columns. The system was equilibrated at 70°C with prefiltered DMF containing 0.05 M LiBr at 1.00 ml min−1. The system was calibrated with poly(ethylene glycol) standards (Polymer Laboratories, Amherst, MA, USA) ranging from 615 to 443 000 Da.

Transmission electron microscope (TEM) analyses were performed on a JEOL 1200EX TEM operating at 100 kV, and micrographs were recorded at calibrated magnifications, using an SIA-15C CCD camera. The final pixel size was 0.42 nm per pixel. The number-average particle diameters (Dav) and standard deviations were generated from the analysis of particles from at least two different micrographs.

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements were conducted using a Delsa Nano C (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA) equipped with a laser diode operating at 658 nm. Size measurements were made in water (n = 1.3329, η = 0.890 cP at 25 ± 1°C; n = 1.3293, η = 0.547 cP at 50 ± 1°C; n = 1.3255, η = 0.404 cP at 70 ± 1°C). Scattered light was detected at a 165° angle and analysed using a log correlator over 70 accumulations for 0.5 ml of sample in a glass sizing cell (0.9 ml capacity). The photomultiplier aperture and the attenuator were automatically adjusted to obtain a photon counting rate of ca 10 kcps. The calculations of the particle size distribution and distribution averages were performed using CONTIN particle size distribution analysis routines. The peak average of histograms from intensity, volume or number distributions out of 70 accumulations was reported as the average diameter of the particles.

2.3. Peptide nucleic acid synthesis and characterization

The antisense iNOS PNA was chosen from PNAs previously identified by an mRNA mapping method. PNAs were synthesized on XAL-PEG-PS resin on a 2 µmol scale by standard automated solid phase Fmoc chemistry on an Expedite 8909 synthesizer. For the Cy5-PNA, Cy5 NHS ester was coupled to the free amino terminus of the PNA on the column. After syntheses, the PNAs were cleaved from the solid support, and the bases were deprotected, using trifluoroacetic acid (TFA)/m-cresol (4 : 1, v/v) for 3 h and then precipitated with diethyl ether. The crude products were purified by high-performance liquid chromatography on a Microsorb-MV 300-5 C-18 column (Varian Inc.) with a method of 0–40% B/40 min, 40–100% B/5 min, 100–0%/3 min, where A = 0.1 per cent TFA in water, B = 0.1 per cent TFA in CH3CN. The fraction containing the pure PNA was evaporated to dryness in a Savant Speedvac and characterized by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry carried out with a PerSpective Voyager mass spectrometer with α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid as the matrix and insulin as the internal reference (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1).

2.4. Cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle synthesis and characterization

2.4.1. Preparation of the block copolymer micelles

To PAEA160-b-PS30 (25 mg) biological grade nanopure water (25 ml) was added and stirred at room temperature (RT). The polymer dissolved into solution immediately affording a clear solution of micelles at a concentration of 1 mg ml−1. (Dh)int (DLS) = 171±46 nm; (Dh)vol (DLS) = 45±30 nm; (Dh)num (DLS) = 30±8 nm. Zeta potential = 38±2 mV (pH 5.5).

2.4.2. Preparation of the cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticles

To a clear solution of micelles (13 ml, 1 mg ml−1), sodium carbonate (20 µl of 1.0 M aqueous solution) was added to adjust the pH to ca 8.0. A diacid cross-linker, 4,15-dioxo-8,11-dioxa-5,14-diazaoctadecane-1,18-dioic acid (2.0 mg), was activated with HOBT (1.7 mg, 2.2 equiv. per COOH) and HBTU (4.8 mg, 2.2 equiv. per COOH) in 300 µl of DMF, and the reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 30 min at RT. The activated cross-linker was slowly added to the micellar solution to cross-link ca 5 per cent of the amines. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight, and transferred to a pre-soaked dialysis tube (molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) ca 6000–8000 Da) and dialysed against nanopure water for ca 3 days to obtain clear cSCK solution with a final concentration of 0.85 mg ml−1. (Dh)int (DLS) = 157 ± 140 nm; (Dh)vol (DLS) = 33 ± 22 nm; (Dh)num (DLS) = 22 ± 6 nm. Zeta potential is 28 ± 2 mV; pH 5.5. TEM images are shown in the electronic supplementary material, figure S2.

2.4.3. Conjugation of cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticles with Alexa Fluor 488-NHS

To a cSCK solution (3.5 ml, 0.85 mg ml−1) was added sodium carbonate (20 µl of 1.0 M aqueous solution) to adjust the pH to ca 8.0. Alexa Fluor 488 (0.1 mg, 0.1 µM) in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) was added (1 mg per 0.5 ml) to tether ca 1 dye per polymer chain. The reaction was stirred overnight in dark at RT. The solution was dialysed (MWCO ca 6000–8000 Da) against 150 mM phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) buffer for 1 day followed by nanopure water for 3 days in an Al-foil-wrapped beaker to obtain fluorescent solution of cSCK with a concentration of 0.8 mg ml−1. Dye concentration was quantified with a UV–visible spectrophotometer and found to be 5.10 µM yielding 0.1 dye per polymer chain. (Dh)int (DLS) = 120 ± 91 nm; (Dh)vol (DLS) = 34 ± 20 nm; (Dh)num (DLS) = 23 ± 7 nm. Zeta potential = 37 ± 1 mV (pH 5.5).

2.4.4. Preparation of PNA-YR9 · ODN · cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle complexes

PNA · ODN duplexes were first hybridized by incubating PNA-YR9 and a partially complementary ODN in 0.1 M NaCl at 95°C for 5 min, followed by slowly cooling down to RT. PNA · ODN · cSCK complexes were formed by mixing the cSCK nanoparticles and PNA-ODN duplexes in PBS buffer or Opti-MEM medium for 30 min followed by gel electrophoresis.

2.4.5. Binding affinity of cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticles for PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti duplexes

The partially complementary ODNanti was 5′-labelled by [γ-32P]-adenosine triphosphate with T4 polynucleotide kinase and hybridized in about more than 1.5-fold to PNAantiYR9 to form the PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti hybrid. Serial amounts of cSCK were mixed in PBS buffer for 30 min with 50 nM radiolabelled PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti at cSCK amine to ODN phosphate (N/P) ratios of 0, 1 : 1, 2 : 1, 4 : 1, 8 : 1, 16 : 1 and 32 : 1. The complexes were then mixed with loading buffer (six times), and subjected to 6 per cent native polyacrylamide gel with 400 V for 1.5 h.

2.4.6. Confocal microscopy

RAW264.7 cells were plated in 35 mm MatTek glass bottom microwell dishes at a density of 3 × 104 cells per well and cultured in 150 µl of complete medium. The cells were then activated by lipopolysaccharides (LPS from Escherichia coli 055:B5, Sigma, 1 µg ml−1) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ; mouse, recombinant, E. coli, Peprotech, 50 ng ml−1) [46]. After 24 h, Cy5-PNA-YR9 · ODN (0.5 µM) complexed to cSCK-Alexa Fluor 488 (9.6 µg ml−1) was added to the cells and incubated for an additional 24 h. One hour before examining under a confocal microscope, 1 µl of Hoechst 33342 (10 µg ml−1) was added to each dish and incubated in the cell culture incubator to stain the nucleus. Each dish was washed with PBS buffer (n = 3) and viewed under a Nikon A1 confocal microscope (Nikon) with excitation by an Ar laser (488 nm) and a He–Ne laser (633 nm).

2.4.7. Cytotoxicity assay

Cytotoxicity of the PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK complexes was examined by CellTiter 96 non-radioactive cell proliferation assay (Promega). RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and cultured in 100 µl of complete medium. One day prior to transfection, cells were activated with LPS and IFN-γ. Twenty-four hours later, the medium was replaced with 100 µl fresh culture medium containing complexes of PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK (0.5 µM) with cSCKs (9.6 µg ml−1). After 24 h, cytotoxicity was determined according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.4.8. Radiolabelling of PNA-YR9

Iodine (123I; t1/2 = 13.2 h, EC = 97%) was purchased from Nordion with greater than or equal to 95 per cent radiochemical purity. The antisense and mismatch PNA-YR9 (9.65 nmol) were radio-iodinated with 37 MBq 123I, using the Iodogen method at RT [47]. The radiolabelled 123I-PNA-YR9 sequences were purified by solid phase extraction with specific activity of 1.53 MBq nmol−1. About 20 MBq, 123I-PNA-YR9 sequences (0.54 nmol, radiochemical purity ≥ 95%) were hybridized with equal amounts of the complementary ODN at 95°C in 50 µl 0.1 M NaCl for 5 min. The 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN hybrids were cooled at RT for 10 min and immediately followed by incubation with 500 µl cSCK (0.07 mg ml−1) in water for 10 min to form the 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes.

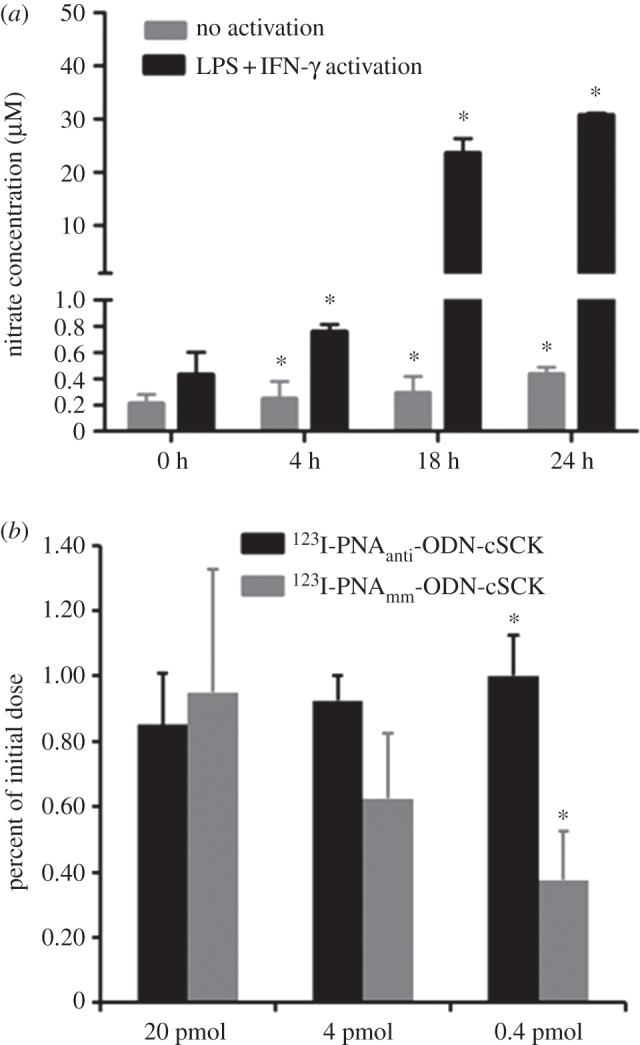

2.4.9. Time course of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in stimulated cells

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well and cultured in 100 μl medium. After 24 h, cells were activated with or without LPS and IFN-γ. Medium was then withdrawn at different time points (0, 4, 18 and 24 h), and NO concentration was measured by Griess assay (Promega) with absorbance at 540 nm read on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

2.4.10. Cellular uptake of 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle nanocomplexes

The cellular uptake studies of the 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes were performed in 2 × 105 RAW264.7 cells seeded on a semipermeable, polycarbonate supported membrane (Transwell, Corning) that were pre-stimulated with LPS (1 µg ml−1) and IFN-γ (50 ng ml−1) 24 h earlier. One microlitre samples of 37, 7.4, 0.74 kBq µl−1 solutions of 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes (64.75, 12.95 and 1.295 ng cSCK, respectively), containing 20, 4 and 0.4 pmol of 123I-PNA-YR9, respectively, were tested for dose–response studies. The complexes contained 10 molar equivalents of 123I-PNA-YR9 per cSCK. During the study, cells were washed three times at 4, 18 and 24 h. After the final wash, the cells on the membrane of insert and the washing solutions were separately counted in a gamma counter.

2.4.11. In vivo inducible nitric oxide synthase stimulation and measurement

C57BL/6 male mice (Jackson Laboratory) were anaesthetized with ketamine/xylazine, the trachea was surgically exposed and a Penn-Century MicroSprayer was inserted into the tracheal lumen. LPS (0.5 μg) and IFN-γ (20 ng), diluted in 50 μl sterile PBS, were injected into the lungs in two 25 µl boluses, 30 s apart. After 24 h, the mice were euthanized, and the lungs were lavaged with 1 ml of PBS (n = 3). The lungs were excised and disrupted via a bead homogenizer. RNA was extracted from the lung homogenate with the Illustra RNAspin mini isolation kit (GE Healthcare) and quantity determined by NanoDrop (Thermofisher, DE, USA). Reverse transcription was performed with the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (AB) in the presence of RNAse inhibitor (AB). The cDNA was then subjected to reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), using the TaqMan fast universal PCR master mix (AB) and PrimeTimeqPCR assays for NOS2 (IDT Mm.PT.42.11140954) and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (IDT Mm.PT.42.7902271.g). A vehicle (PBS, pH 7.4)-treated group was tested as a control.

2.4.12. In vivo biodistribution study

For biodistribution study, 24 h after the LPS + INF-γ stimulation, 9.25 kBq 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes in 50 µl of PBS were administrated intratracheally by bolus injection. At 4 and 24 h post injection (p.i.), the mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, and organs of interest were collected for determination of radioactivity, using a Beckman Gamma Counter 8000. Additionally, [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose ([18F]FDG) [48] (370 kBq) was also used to evaluate the lung inflammation following the same endotoxin stimulation through biodistribution study with organs collected at 1 h p.i. [18].

3. Results

3.1. Cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle synthesis and characterization

The block copolymer precursor to the cSCKs was prepared by a sequential atom transfer radical polymerization of tert-butyl acrylate and styrene followed by acidolysis of the tert-butyl protecting group, amidation of N-boc ethylene diamine to the polymer backbone and finally trifluoroacetic acid mediated removal of the boc protecting group to yield cationic amphiphilic block copolymer of PAEA160-b-PS30.

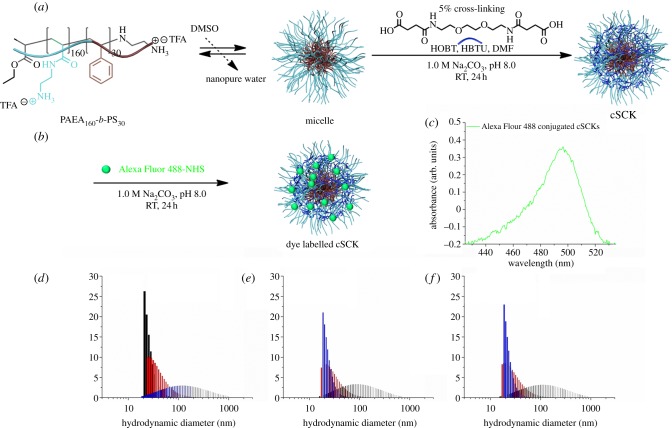

cSCKs were prepared by solution-state assembly of the cationic amphiphilic block copolymer in water followed by cross-linking reactions selectively throughout the hydrophilic shell layer (figure 2a). Self-assembly was induced by dissolving PAEA160-b-PS30 in water to obtain a clear micellar solution. The cSCKs were obtained by cross-linking approximately 5 per cent of the amine residues on the hydrophilic shell via the reaction of amines with acid groups in the cross-linker, activated by HOBT and HBTU in DMF, followed by extensive dialysis.

Figure 2.

(a) Self-assembly of amphiphilic block copolymer to form micelles followed by cross-linking of micelles to afford cSCKs. (b) Alexa Fluor 488-NHS conjugation to cSCKs. (c) UV–visible spectroscopy of fluorophore-labelled cSCK. (d–f) Dynamic light scattering measurements of micelles, cSCKs and dye-labelled SCKs. (d) Black bar, number; red bar, volume; blue bar, intensity. (e,f) Blue bar, number; red bar, volume; black bar, intensity.

Alexa Fluor 488 NHS was attached to the cSCKs by performing a post-assembly modification of the nanoparticles (figure 2b). The amines on the hydrophilic shell were allowed to react with activated ester moieties on the dye, followed by extensive dialysis to remove unconjugated dye and reaction by-products. The amount of dye conjugated was quantified by UV–visible spectrophotometry and ca 0.1 dye was conjugated per polymer chain (figure 2c). The sizes of the particles were ca 22 nm in diameter as observed by DLS (figure 2d–f). The positive charge (37 ± 1 mV) was used to form PNA–cSCK complexes through electrostatic interactions.

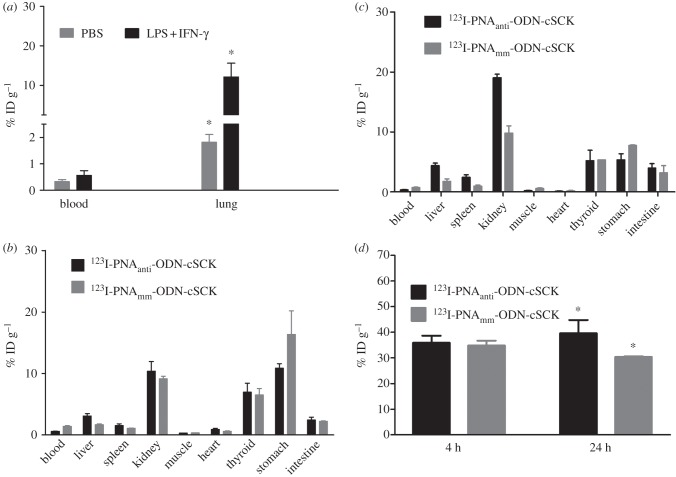

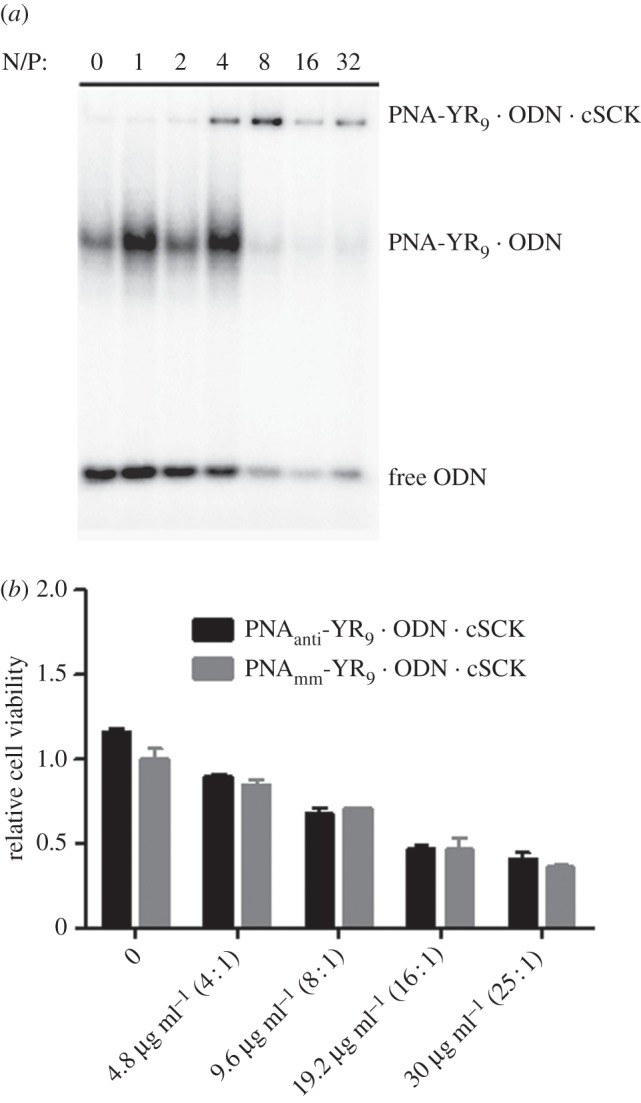

3.2. Binding affinity of cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle for the PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti duplex

The binding affinity of cSCK for the PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti duplex was determined by a gel retardation assay with 50 nM PNAantiYR9 · 32P-ODNanti duplex, along with excess 32P-labelled ODN at increasing N/P ratios (ratios of cSCK amino groups to ODN phosphates). Complete binding of both the PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti duplex and free ODNanti could be achieved at an N/P ratio of 8 (figure 3a). At an N/P ratio of 4, more of the ODN was observed to be bound by the cSCK than the PNA-YR9.

Figure 3.

(a) Gel retardation assay of PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes at different N/P ratios. (b) Cytotoxicity of antisense and mismatched PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK in RAW264.7 cells.

3.3. Cytotoxicity of PNA-YR9 · ODN · cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle

The cytotoxicity gradually increased for both PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti and PNAmmYR9 · ODNmm hybrids with an increase in cSCK concentration (figure 3b). Very low cytotoxicity was observed at 9.6 µg ml−1 cSCK with 0.5 µM PNA · ODN corresponding to an N/P ratio of 8 : 1, which was found to bind all the PNA-YR9 · ODN hybrid, and thus serves as the optimal concentration for further in vitro and in vivo studies.

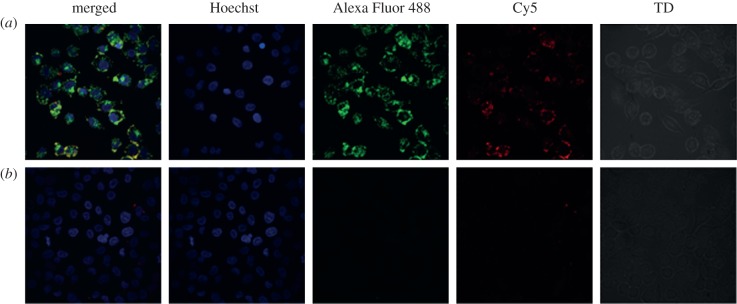

3.4. Intracellular localization of fluorescently labelled PNA · ODN · cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle

After 24 h incubation with unstimulated cells, the entry of PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes inside the RAW264.7 cells was shown by the co-localization of Alexa Fluor 488-labelled cSCK with the Cy5-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti in endosomal- or lysosomal-like vesicles using confocal microsocopy. Analysis of the images showed that all cells contained the Alexa Fluor 488-cSCK with a mean intensity of 28 ± 11 arb. units and the Cy5-PNA with 7.4 ± 3.4 arb. units indicating that they were entering the cells together. Cy5-PNA-YR9 · ODN was not able to enter cells by itself (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Confocal microscopy of intracellular localization of Cy5-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK-Alexa Fluor 488 nanocomplexes in iNOS-induced RAW264.7 cells. (a) Cy5-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK-Alexa Fluor 488 and (b) Cy5-PNAantiYR9 · 0DNanti.

3.5. In vitro cell uptake of 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like nanoparticle in stimulated RAW264.7 cells

The induction of iNOS mRNA expression in the RAW264.7 cells was carried out with IFN-γ and LPS [46], and iNOS expression was quantified by the Griess reaction. After 4 h, the nitrite concentration was significantly (p < 0.005, n = 3) elevated and further increased at 18 h, and at 24 h, at which it was 70-fold higher than that of the control group (figure 5a). To study the uptake and retention of the radiolabelled PNA-YR9 probes, RAW264.7 cells were first activated with LPS + INF-γ and 24 h later incubated with three different amounts of antisense and mismatched 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes for 24 h (figure 5b). An increase in the difference between the amount of antisense and mismatched PNA-YR9 probes retained by the cells was observed as the amount of probe was decreased from 20 to 0.4 pmol of PNA. The greatest difference was observed for 0.4 pmol of PNA (0.02 µCi; 1.0 ± 0.13% versus 0.38 ± 0.15%, p < 0.01, n = 3; figure 5b).

Figure 5.

(a) Time course of iNOS expression in RAW264.7 cells with and without LPS + INF-γ activation. (b) Cellular uptake of 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK and 123I-PNAmmYR9 · ODNmm · cSCK. *p < 0.05, n = 3 per group.

3.6. In vivo biodistribution study

To evaluate the ability of the 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODN · cSCK complex to detect iNOS mRNA in vivo, we first established that iNOS could be induced in mice lungs by intratracheal administration of LPS + INF-γ. The iNOS expression level was increased almost threefold compared with the PBS-vehicle-treated group (2.7 ± 0.8 versus 1.00 ± 0.18, n = 3 each group, p < 0.05). Further evaluation of the iNOS-associated inflammatory response in the LPS + INF-γ activated lung by the [18F]FDG metabolism radiotracer showed similar blood uptake in both stimulated and unstimulated groups as expected [9]. However, there was significantly higher lung retention in the LPS + INF-γ-treated group (p = 0.001, n = 4) compared with the PBS-treated group (figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Biodistribution of (a) [18F]FDG in PBS and LPS + INF-γ-treated C57BL/6 mice at 1 h p.i., 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK and 123I-PNAmmYR9 · ODNmm · cSCK in iNOS stimulated C57BL/6 mice at (b) 4 h and (c) 24 h p.i. (d) Lung retention of 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK and 123I-PNAmmYR9 · ODNmm · cSCK in iNOS stimulated C57BL/6 mice. *p < 0.05, n = 4 per group.

Next, mice were treated with LPS + INF-γ in the same manner, followed 24 h later with either 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK or 123I-PNAmmYR9 · ODNmm · cSCK nanocomplexes and analysed for biodistribution at 4 (figure 6b) and 24 h (figure 6c). The highest retention of radioactivity was observed in the lungs at both time points (figure 6d). This observation is in contrast to the fast lung clearance and low retention obtained with free 123I-PNAantiYR9 and 123I-PNAmmYR9 (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S3) suggesting an important role of the cSCK nanoparticles. Noticeably, the 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK resulted in significantly (p < 0.05, n = 4) higher lung retention (40 ± 5% injected dose (ID) g−1 at 24 h, n = 4) when compared with 123I-PNAmmYR9 · ODN · cSCK (30.3 ± 0.2% ID g−1, n = 4) at 24 h.

Relatively elevated levels were observed in other organs such as thyroid, stomach, intestine, liver and kidney (figure 6b,c). Interestingly, the accumulation of radioactivity in the kidney was 19 ± 1% ID g−1 for the antisense PNA which was significantly (p < 0.05, n = 4) higher than that for mismatched PNA (10 ± 2% ID g−1) at 24 h. Accumulation of radioactivity in thyroid is most likely due to de-iodination and decreased slightly at 24 h.

4. Discussion

Customized nanoparticles have been widely used for diagnosis and treatment of lung disease owing to their unique physico-chemical properties [42,49]. Development of specific nanostructures for lung imaging, however, still needs comprehensive development before translation to the clinic. Among various nanoconstructs, polymeric nanoparticles have drawn particular attention owing to advances in controlled polymerization techniques. As a result, multifunctional and multivalent nanostructures can be prepared with an architecture, shape, size, surface charge and functionalization tailored for a particular application.

Most imaging probes for diagnosis of injury and disease make use of small-molecule ligands, peptides and proteins targeted to specific receptors. In comparison, much fewer studies have focused on targeting disease- and injury-specific mRNAs, despite the fact that it is very easy to design highly specific antisense nucleic acids, using Watson–Crick base pairing [12,17,21,40]. One of the principal reasons for the slow development of antisense imaging agents is that these agents are quite large and membrane impermeable which requires that they be delivered through some auxiliary, such as a CPP. Even with such auxiliaries, the antisense nucleic acid agent often becomes trapped in endosomes or lysosomes, as well as inside the cytoplasm, resulting in a high background signal. In previous studies [33,44], we have demonstrated the efficient intracellular delivery of PNA and DNA via cSCK in vitro but not in vivo.

In this study, a self-assembling electrostatic nanocomplex of PNA · ODN hybrids with cSCK was evaluated as a potential imaging agent for iNOS expression. To the best of our knowledge, iNOS mRNA-targeted nanoparticles have not previously been evaluated for delivery to the respiratory tract, where cell targets and host defence mechanisms present an environment that is very different from that of the vascular system and other organs. To ensure that we could demonstrate sequence-specific binding to the target mRNA, we carefully designed the antisense PNA probe to target a validated, high affinity binding site [33]. We then designed the control PNA probe to be identical in base composition, and 66 per cent identical in sequence, only having the central five nucleotides out of 15 mismatched. The PNAs were then hybridized to complementary ODNs to leave a three-nucleotide sticky end or ‘toehold’ to enable initial binding to the target mRNA, which is then followed by branch migration and displacement of the shorter ODN to produce a more stable PNA · RNA hybrid. The displaced or spontaneously dissociated ODN is also expected to be enzymatically degraded thereby ensuring binding of the PNA to the target mRNA. This strand displacement strategy has recently been successfully used to generate fluorescent imaging probes for iNOS mRNA [19].

The cSCK nanoparticle has been reported as an effective vehicle for intracellular delivery of PNA · ODN hybrids and DNA by an endocytotic mechanism [33]. By adjusting the N/P ratio, the cSCK binding affinity could be optimized for the binding and delivery of the PNA-YR9 · ODN. Consistent with previous results [50], complete binding of cSCK to PNA-YR9 · ODN was achieved at low N/P ratio (8 : 1) as evidenced by the gel retardation assay (figure 3a). The cSCK did show a higher affinity for the ODN alone at an N/P ratio of 4, as might be expected from the greater net charge of the ODN than PNA-YR9, owing to cancellation of nine of the 16 negative charges by the arginines. Importantly, no significant cytotoxicity in the RAW264.7 cell line was observed during the MTT assay with this ratio. Thus, the 8 : 1 N/P ratio was used for PNA delivery to target the iNOS mRNA.

In a previous transfection study in HeLa cells, we observed significant fluorescein signal in the cytoplasm, along with co-localized Cy5 and fluorescein signals in what appeared to be endosomes and lysosomes. We interpreted this to indicate that the cSCK was able to disrupt the endosome and facilitate release of some of the PNAs, while remaining largely trapped inside. We had proposed that the presence of free amine groups on cSCK at neutral pH might lead to endosomal destabilization upon acidification by the sponge effect, thus resulting in the release of PNAs to cytoplasm for mRNA binding, but that the cSCK was too large to exit [33]. Dissociation of the PNA · ODN from the cSCK is expected to occur upon exposure to mRNA and other negatively charged biomolecules in the cytoplasm, and possibly as a result of the spontaneous dissociation and enzymatic degradation of the ODN that originally imparted the negative charge to the PNA. In this study, we mainly observed what we interpreted to be co-localization of the fluorescein-cSCK and the Cy5-PNA-YR9 in endosomes of RAW264.7 cells. The failure to observe significant release of PNA into the cytoplasm may possibly be due to the lower detection sensitivity of confocal microscopy for the Cy5 than the fluorescein, and the higher numbers of fluorophores per nanoparticle than for the free PNA. It is also possible that cSCK-mediated escape from endosomes in RAW264.7 cells is less efficient. We do not believe this to be the case, however, as studies with a quenched strand displacement PNA · ODN system targeted to iNOS mRNA in RAW264.7 cells showed a significant increase in signal indicating that a good fraction of the PNAs escaped from the cSCKs into the cytoplasm and were able to hybridize to the target mRNA [19]. It may also be that if the PNA is in excess over the target mRNA, then the majority of the signal will come from the PNA that remains associated with the cSCK, and little from the PNA · mRNA.

When we tested the preferential ability of iNOS stimulated RAW264.7 cells to uptake and retain antisense versus mismatched 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes at 24 h, we found that the selectivity was strongly concentration-dependent, with no significant selectivity with 20 pmol of delivered PNA, but significant selectivity with 0.4 pmol (p < 0.05, n = 3). The results can be understood by considering the amount of iNOS mRNA present in the cell compared with the amount of probe. As part of another study [19], we had determined, by absolute RT-PCR using authentic iNOS mRNA to generate a standard curve, that the iNOS level rises 100-fold 18 h after induction, to about 76 000 copies of iNOS mRNAs per cell. Given that 105 cells were used in the experiment and assuming 100 000 copies of iNOS mRNA per cell after 24 h, one can estimate that the amount of target iNOS mRNA in the sample was about 0.02 pmol. Therefore, at doses of 37, 7.4 and 0.74 kBq, corresponding to 20, 4 and 0.4 pmol of 123I-PNA-YR9 based on its specific activity of 1.53 MBq nmol−1, there would be about 1200-, 235- and 23-fold excess PNA probe over target mRNA.

The poor selectivity at the high dose could therefore be explained by the large excess (approx. 0.2 pmol) of antisense and mismatched PNAs that remain in the cell after 24 h relative to the amount of target mRNA (0.02 pmol). The lack of a difference between the amount of retained antisense and mismatched probes further confirms that both targeted and non-targeted PNAs are being delivered equally efficiently by the cSCK and are exiting the cell equally efficiently. Thus, if both PNAs were entering and exiting with the same rate, at best, then the target mRNA could retain only an additional 10 per cent of the antisense PNA compared with the amount of mismatch PNA remaining in the cell (0.2 + 0.02 pmol antisense to 0.2 pmol mismatch). On the other hand, when the dose is low, the amount of target mRNA is much greater than the amount of mismatch PNA remaining in the cell and could thus retain a much greater proportion of the antisense PNA. In this case, one could predict a factor of 14 in favour of the antisense PNA compared with the mismatch PNA (0.0015 + 0.02 to 0.0015 pmol antisense). This is much greater than the value of 2.7 observed, but there are many other factors that might reduce the observed selectivity, such as failure of the antisense PNA to exit the endosomes efficiently and reach the target mRNA. In any case, these results suggested that the in vivo experiments should be carried out with as low a dose as possible.

To determine the specificity of the probe in vivo, we used a mouse ALI model. Although the exact mechanisms underlying ALI are still unclear, it is known that macrophages, neutrophils and lung epithelial cells become highly activated in response to inflammatory stimuli, and neutrophilic inflammation is a prominent characteristic [51]. Thus, [18F]FDG has been widely used to monitor the lung inflammatory response to low-dose endotoxin in a single lung segment [52]. In our ALI model, the [18F]FDG uptake was almost sixfold higher than that retained in the control group (figure 6a), confirming the on-going inflammatory process during the study. Although the presence of cSCK nanocomplexes might also cause severe lung injury [53], their effect is beyond the scope of this study.

The biodistribution studies were carried out with a dose of 9.25 kBq of antisense and mismatched 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes, corresponding to 14 pmol of 123I-PNA-Y-R9 for 250 mg of mouse lung. Given about 108 cells g−1 of tissue, this would correspond to approximately 3.3 × 105 PNAs per cell if taken up equally, which roughly corresponds to the 105 copies of iNOS in induced cells. We know, however, from other studies that the cSCK complexes are preferentially taken up in macrophages, so that the amount of PNA may be much higher in these cells. Considering the cellular heterogeneity of the lung, it was quite remarkable that we saw a statistically different retention of the antisense PNA compared with the mismatch PNA. This difference in retention was observed only for the lung, and not for any other organs. As expected, for non-specific uptake of the nanocomplexes of antisense and mismatched PNAs and non-specific clearance from uninduced cells, the biodistribution in the non-targeted organs showed similar profiles at both 4 and 24 h. Accumulation of radioactivity in the thyroid, liver and kidney is likely due to transit from the air space through the alveolar epithelium–capillary endothelial barrier [54], which was also confirmed by measurable activity in the blood at 4 and 24 h p.i. Similar to the reported extra pulmonary fate of nanoparticles, following intratracheal instillation [51,55], significant amounts of gastrointestinal tract clearance were observed for both nanocomplexes, likely due to mucociliary clearance.

Recently, a report showed that the translocation of nanoparticles from the lung airspace to the body was size-dependent, irrespective of chemical composition, shape and conformational flexibility. Consistent with these findings, the two positively charged nanocomplexes (approx. 22 nm) showed low blood retention during the 24 h study period (less than 1.5% ID g−1 at 4 h and less than 1% ID g−1 at 24 h, figure 6) possibly owing to their small size. Noticeably different from the predominant renal clearance of free 123I-PNAantiYR9 and 123I-PNAmmYR9, the 123I-PNAantiYR9 · ODNanti · cSCK and 123I-PNAmmYR9 · ODNmm · cSCK nanocomplexes exhibited significantly (p < 0.001, n = 4) prolonged lung retention. This prolonged retention is possibly due to rapid uptake by pulmonary macrophage and epithelial cells, while retaining constant kidney clearance, indicating the in vivo stability of these electrostatic nanocomplexes, and more importantly, the release of 123I-PNAmmYR9 · ODNmm from cSCK for iNOS mRNA targeting possibly owing to the proton sponge effect. Further, the low thyroid uptake of these two nanocomplexes and 123I-labelled PNAs (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S3) also confirmed the stability of the radio-iodination label. While the initial results are encouraging, the difference in uptake between the antisense and mismatched PNAs used in this study is not sufficient for diagnostic imaging. Further studies are focusing on enhancing the escape of unbound PNA and using radioisotopes with longer half-life and better detection efficiency such as 124I to enable imaging at longer times.

5. Conclusion

We have shown that PNA · ODN · cSCK nanocomplexes had significant sequence-specific retention in the induced RAW264.7 cells when used at a dose corresponding to the level of target mRNA. When used in a mouse ALI model, the 123I-PNA-YR9 · ODN-cSCK nanocomplexes showed much greater lung retention compared with the free 123I-PNA-YR9 and a statistically significant sequence specificity for iNOS mRNA. This study demonstrates the potential feasibility of using a radiolabelled electrostatic nanocomplex for selective in vivo iNOS mRNA imaging. Further studies will be directed towards increasing the specific activity of the PNAs, and radiolabelling with 124I/76Br for positron emission tomography imaging of iNOS expression in an ALI model. In addition, nanoparticles are under development with better properties, including degradability and enhanced endosomal release, which may make such radiolabelled antisense imaging agents a viable imaging technology.

Acknowledgements

All animal studies were performed in compliance with guidelines set forth by the NIH Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare and approved by the Washington University Animal Studies Committee.

We thank Nicole Fettig, Margaret Morris, Amanda Roth, Lori Strong and Ann Stroncek for their assistance with animal studies. This study was supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health as a Programme of Excellence in Nanotechnology (HHSN268201000046C). The Welch Foundation is gratefully acknowledged for support through the W.T. Doherty-Welch Chair in Chemistry (grant no. A-0001). We thank Deborah Sultan for editing.

References

- 1.Johnson ER, Matthay MA. 2010. Acute lung injury: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. J. Aerosol Med. Pulmon. Drug Deliv. 23, 243–252 10.1089/jamp.2009.0775 (doi:10.1089/jamp.2009.0775) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta S. 2005. The effects of nitric oxide in acute lung injury. Vasc. Pharmacol. 43, 390–403 10.1016/j.vph.2005.08.013 (doi:10.1016/j.vph.2005.08.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo FH, De Raeve HR, Rice TW, Stuehr DJ, Thunnissen FB, Erzurum SC. 1995. Continuous nitric oxide synthesis by inducible nitric oxide synthase in normal human airway epithelium in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 7809–7813 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7809 (doi:10.1073/pnas.92.17.7809) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hosogi S, Iwasaki Y, Yamada T, Komatani-Tamiya N, Hiramatsu A, Kohno Y, Ueda M, Arimoto T, Marunaka Y. 2008. Effect of inducible nitric oxide synthase on apoptosis in Candida-induced acute lung injury. Biomed. Res. 29, 257–266 10.2220/biomedres.29.257 (doi:10.2220/biomedres.29.257) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hesslinger C, Strub A, Boer R, Ulrich WR, Lehner MD, Braun C. 2009. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase in respiratory diseases. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 886–891 10.1042/BST0370886 (doi:10.1042/BST0370886) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim MH, Xu D, Lippard SJ. 2006. Visualization of nitric oxide in living cells by a copper-based fluorescent probe. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 375–380 10.1038/nchembio794 (doi:10.1038/nchembio794) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taira J, Ohmine W, Ogi T, Nanbu H, Ueda K. 2012. Suppression of nitric oxide production on LPS/IFN-γ-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages by a novel catechin, pilosanol N, from Agrimonia pilosa Ledeb. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 22, 1766–1769 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.086 (doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.086) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouyang J, Hong H, Zhao Y, Shen H, Shen C, Zhang C, Zhang J. 2008. Bioimaging nitric oxide in activated macrophages in vitro and hepatic inflammation in vivo based on a copper-naphthoimidazol coordination compound. Nitric Oxide 19, 42–49 10.1016/j.niox.2008.03.003 (doi:10.1016/j.niox.2008.03.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou D, Lee H, Rothfuss JM, Chen DL, Ponde DE, Welch MJ, Mach RH. 2009. Design and synthesis of 2-amino-4-methylpyridine analogues as inhibitors for inducible nitric oxide synthase and in vivo evaluation of [18F]6-(2-fluoropropyl)-4-methyl-pyridin-2-amine as a potential PET tracer for inducible nitric oxide synthase. J. Med. Chem. 52, 2443–2453 10.1021/jm801556h (doi:10.1021/jm801556h) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mishra R, Su W, Pohmann R, Pfeuffer J, Sauer MG, Ugurbil K, Engelmann J. 2009. Cell-penetrating peptides and peptide nucleic acid-coupled MRI contrast agents: evaluation of cellular delivery and target binding. Bioconjug. Chem. 20, 1860–1868 10.1021/bc9000454 (doi:10.1021/bc9000454) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prigodich AE, Seferos DS, Massich MD, Giljohann DA, Lane BC, Mirkin CA. 2009. Nano-flares for mRNA regulation and detection. ACS Nano 3, 2147–2152 10.1021/nn9003814 (doi:10.1021/nn9003814) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn DG, Shim SB, Moon JE, Kim JH, Kim SJ, Oh JW. 2011. Interference of hepatitis C virus replication in cell culture by antisense peptide nucleic acids targeting the X-RNA. J. Viral Hepat. 18, e298–e306 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01416.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01416.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bai H, et al. 2012. Antisense inhibition of gene expression and growth in gram-negative bacteria by cell-penetrating peptide conjugates of peptide nucleic acids targeted to rpoD gene. Biomaterials 33, 659–667 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.075 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.09.075) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briones C, Moreno M. 2012. Applications of peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) and locked nucleic acids (LNAs) in biosensor development. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 402, 3071–3089 10.1007/s00216-012-5742-z (doi:10.1007/s00216-012-5742-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen J, Peterson KR, Iancu-Rubin C, Bieker JJ. 2010. Design of embedded chimeric peptide nucleic acids that efficiently enter and accurately reactivate gene expression in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16 846–16 851 10.1073/pnas.0912896107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0912896107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kam Y, Rubinstein A, Nissan A, Halle D, Yavin E. 2012. Detection of endogenous K-ras mRNA in living cells at a single base resolution by a PNA molecular beacon. Mol. Pharm. 9, 685–693 10.1021/mp200505k (doi:10.1021/mp200505k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nielsen PE. 2010. Gene targeting and expression modulation by peptide nucleic acids (PNA). Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 3118–3123 10.2174/138161210793292546 (doi:10.2174/138161210793292546) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun X, Fang H, Li X, Rossin R, Welch MJ, Taylor JS. 2005. MicroPET imaging of MCF-7 tumors in mice via unr mRNA-targeted peptide nucleic acids. Bioconjug. Chem. 16, 294–305 10.1021/bc049783u (doi:10.1021/bc049783u) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Zhang K, Wooley KL, Taylor JS. 2012. Imaging mRNA expression in live cells via PNA · DNA strand displacement-activated probes. J. Nucleic Acids 2012, 962652. 10.1155/2012/962652 (doi:10.1155/2012/962652) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen PE. 2004. PNA technology. Mol. Biotechnol. 26, 233–248 10.1385/MB:26:3:233 (doi:10.1385/MB:26:3:233) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lundin KE, Good L, Stromberg R, Graslund A, Smith CI. 2006. Biological activity and biotechnological aspects of peptide nucleic acid. Adv. Genet. 56, 1–51 10.1016/S0065-2660(06)56001-8 (doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(06)56001-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koppelhus U, Nielsen PE. 2003. Cellular delivery of peptide nucleic acid (PNA). Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 55, 267–280 10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00182-5 (doi:10.1016/S0169-409X(02)00182-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu J, Corey DR. 2007. Inhibiting gene expression with peptide nucleic acid (PNA): peptide conjugates that target chromosomal DNA. Biochemistry 46, 7581–7589 10.1021/bi700230a (doi:10.1021/bi700230a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer AK, He J. 2011. Radiolabeled oligonucleotides for antisense imaging. Curr. Org. Synth. 8, 604–614 10.2174/157017911796117241 (doi:10.2174/157017911796117241) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakase I, Akita H, Kogure K, Graslund A, Langel U, Harashima H, Futaki S. 2012. Efficient intracellular delivery of nucleic acid pharmaceuticals using cell-penetrating peptides. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1132–1139 10.1021/ar200256e (doi:10.1021/ar200256e) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers FA, Lin SS, Hegan DC, Krause DS, Glazer PM. 2012. Targeted gene modification of hematopoietic progenitor cells in mice following systemic administration of a PNA-peptide conjugate. Mol. Ther. 20, 109–118 10.1038/mt.2011.163 (doi:10.1038/mt.2011.163) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen G, Fang H, Song Y, Bielska AA, Wang Z, Taylor JS. 2009. Phospholipid conjugate for intracellular delivery of peptide nucleic acids. Bioconjug. Chem. 20, 1729–1736 10.1021/bc900048y (doi:10.1021/bc900048y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shiraishi T, Hamzavi R, Nielsen PE. 2008. Subnanomolar antisense activity of phosphonate-peptide nucleic acid (PNA) conjugates delivered by cationic lipids to HeLa cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 4424–4432 10.1093/nar/gkn401 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkn401) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen FW, Bendifallah N, Zachar V, Shiraishi T, Fink T, Ebbesen P, Nielsen PE, Koppelhus U. 2006. Evaluation of transfection protocols for unmodified and modified peptide nucleic acid (PNA) oligomers. Oligonucleotides 16, 43–57 10.1089/oli.2006.16.43 (doi:10.1089/oli.2006.16.43) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abes R, Arzumanov AA, Moulton HM, Abes S, Ivanova GD, Iversen PL, Gait MJ, Lebleu B. 2007. Cell-penetrating-peptide-based delivery of oligonucleotides: an overview. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 35, 775–779 10.1042/BST0350775 (doi:10.1042/BST0350775) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McNeer NA, Chin JY, Schleifman EB, Fields RJ, Glazer PM, Saltzman WM. 2011. Nanoparticles deliver triplex-forming PNAs for site-specific genomic recombination in CD34+ human hematopoietic progenitors. Mol. Ther. 19, 172–180 10.1038/mt.2010.200 (doi:10.1038/mt.2010.200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Opitz AW, Wickstrom E, Thakur ML, Wagner NJ. 2010. Physiologically based pharmacokinetics of molecular imaging nanoparticles for mRNA detection determined in tumor-bearing mice. Oligonucleotides 20, 117–125 10.1089/oli.2009.0216 (doi:10.1089/oli.2009.0216) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang H, Zhang K, Shen G, Wooley KL, Taylor JS. 2009. Cationic shell-cross-linked knedel-like (cSCK) nanoparticles for highly efficient PNA delivery. Mol. Pharm. 6, 615–626 10.1021/mp800199w (doi:10.1021/mp800199w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juliano R, Alam MR, Dixit V, Kang H. 2008. Mechanisms and strategies for effective delivery of antisense and siRNA oligonucleotides. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 4158–4171 10.1093/nar/gkn342 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkn342) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. 2009. Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 8, 129–138 10.1038/nrd2742 (doi:10.1038/nrd2742) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shim MS, Kwon YJ. 2010. Efficient and targeted delivery of siRNA in vivo. FEBS J. 277, 4814–4827 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07904.x (doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07904.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sokolova V, Epple M. 2008. Inorganic nanoparticles as carriers of nucleic acids into cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 47, 1382–1395 10.1002/anie.200703039 (doi:10.1002/anie.200703039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scholz C, Wagner E. 2011. Therapeutic plasmid DNA versus siRNA delivery: common and different tasks for synthetic carriers. J. Control. Release 161, 554–565 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.014 (doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.11.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nimesh S, Gupta N, Chandra R. 2011. Cationic polymer based nanocarriers for delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 7, 504–520 10.1166/jbn.2011.1313 (doi:10.1166/jbn.2011.1313) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shrestha R, Shen Y, Pollack KA, Taylor JS, Wooley KL. 2012. Dual peptide nucleic acid- and peptide-functionalized shell cross-linked nanoparticles designed to target mRNA toward the diagnosis and treatment of acute lung injury. Bioconjug. Chem. 23, 574–585 10.1021/bc200629f (doi:10.1021/bc200629f) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang J, Lu Z, Wientjes MG, Au JL. 2010. Delivery of siRNA therapeutics: barriers and carriers. AAPS J. 12, 492–503 10.1208/s12248-010-9210-4 (doi:10.1208/s12248-010-9210-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elsabahy M, Wooley KL. 2012. Design of polymeric nanoparticles for biomedical delivery applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 2545–2561 10.1039/c2cs15327k (doi:10.1039/c2cs15327k) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang K, Fang H, Shen G, Taylor JS, Wooley KL. 2009. Well-defined cationic shell crosslinked nanoparticles for efficient delivery of DNA or peptide nucleic acids. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 6, 450–457 10.1513/pats.200902-010AW (doi:10.1513/pats.200902-010AW) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang K, Fang H, Wang Z, Taylor JS, Wooley KL. 2009. Cationic shell-crosslinked knedel-like nanoparticles for highly efficient gene and oligonucleotide transfection of mammalian cells. Biomaterials 30, 968–977 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.057 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.10.057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fang H, Shen Y, Taylor JS. 2010. Native mRNA antisense-accessible sites library for the selection of antisense oligonucleotides, PNAs, and siRNAs. RNA 16, 1429–1435 10.1261/rna.1940610 (doi:10.1261/rna.1940610) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chan ED, Riches DW. 2001. IFN-γ + LPS induction of iNOS is modulated by ERK, JNK/SAPK, and p38mapk in a mouse macrophage cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C441–C450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salacinski PR, McLean C, Sykes JE, Clement-Jones VV, Lowry PJ. 1981. Iodination of proteins, glycoproteins, and peptides using a solid-phase oxidizing agent, 1,3,4,6-tetrachloro-3α,6α-diphenyl glycoluril (Iodogen). Anal. Biochem. 117, 136–146 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90703-X (doi:10.1016/0003-2697(81)90703-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen DL, et al. 2009. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for lung antiinflammatory response evaluation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 180, 533–539 10.1164/rccm.200904-0501OC (doi:10.1164/rccm.200904-0501OC) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu Y, Welch MJ. 2012. Nanoparticles labeled with positron emitting nuclides: advantages, methods, and applications. Bioconjug. Chem. 23, 671–682 10.1021/bc200264c (doi:10.1021/bc200264c) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang K, Fang H, Wang Z, Li Z, Taylor JS, Wooley KL. 2010. Structure–activity relationships of cationic shell-crosslinked knedel-like nanoparticles: shell composition and transfection efficiency/cytotoxicity. Biomaterials 31, 1805–1813 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.033 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.033) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu Y, Ibricevic A, Cohen JA, Cohen JL, Gunsten SP, Frechet JM, Walter MJ, Welch MJ, Brody SL. 2009. Impact of hydrogel nanoparticle size and functionalization on in vivo behavior for lung imaging and therapeutics. Mol. Pharm. 6, 1891–1902 10.1021/mp900215p (doi:10.1021/mp900215p) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen DL, Schuster DP. 2004. Positron emission tomography with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose to evaluate neutrophil kinetics during acute lung injury. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 286, L834–L840 10.1152/ajplung.00339.2003 (doi:10.1152/ajplung.00339.2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi HS, et al. 2010. Rapid translocation of nanoparticles from the lung airspaces to the body. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 1300–1303 10.1038/nbt.1696 (doi:10.1038/nbt.1696) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shimada A, Kawamura N, Okajima M, Kaewamatawong T, Inoue H, Morita T. 2006. Translocation pathway of the intratracheally instilled ultrafine particles from the lung into the blood circulation in the mouse. Toxicol. Pathol. 34, 949–957 10.1080/01926230601080502 (doi:10.1080/01926230601080502) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lipka J, Semmler-Behnke M, Sperling RA, Wenk A, Takenaka S, Schleh C, Kissel T, Parak WJ, Kreyling WG. 2010. Biodistribution of PEG-modified gold nanoparticles following intratracheal instillation and intravenous injection. Biomaterials 31, 6574–6581 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.009 (doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.05.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]