Abstract

Congenital myopathy related to mutations in myosin MyHC IIa gene (MYH2) is a rare neuromuscular disease. A single dominant missense mutation has been reported so far in a family in which the affected members had congenital joint contractures at birth, external ophthalmoplegia and proximal muscle weakness. Afterward only additional 4 recessive mutations have been identified in 5 patients presenting a mild non-progressive early-onset myopathy associated with ophthalmoparesis. We report a new de novo MYH2 missense mutation in a baby affected by a congenital myopathy characterized by severe dysphagia, respiratory distress at birth and external ophthalmoplegia. We describe clinical, histopathological and muscle imaging findings expanding the clinical and genetic spectrum of MYH2-related myopathy.

Keywords: MyHC IIa, MYH2, Congenital myopathy, Ophthalmoplegia, Joint contractures

1. Introduction

Hereditary myosin myopathies are a group of muscle diseases with variable age of onset and heterogeneous clinical features, caused by mutations in the skeletal muscle myosin heavy chain (MyHC) genes [1]. Three major isoforms are known in adult human limb muscle fibers: MyHC I, encoded by MYH7 and expressed in slow type I muscle fibers and in heart ventricles; MyHC IIa, encoded by MYH2 and expressed in fast type IIA muscle fibers, and MyHC IIx expressed in fast type IIB muscle fibers [1]. To date pathogenetic mutations associated to hereditary myopathies have been identified in both MYH7 and MYH2 genes [2]. The first pathogenetic MYH2 mutation, reported by Martinsson and coauthors in 2000 [3], was a dominant missense mutation in exon 17 (c.2116, G>A), giving rise to an amino acid shift p.Glu706 Lys (E706K). All affected members showed multiple joint contractures at birth and external ophthalmoplegia. The disease was non-progressive in childhood but patients progressively developed proximal muscle weakness by the age of 30 years [4]. In 2005 two additional heterozygous missense mutations in MYH2 have been identified in 2 unrelated patients affected by a mild proximal myopathy. However the pathogenetic role of these mutations was not completely proven [5]. Thus, with the exception of the original family harboring the dominant E706K, only 5 additional patients, from three unrelated families, with autosomal recessive mutations in MYH2 have been reported [6]. All these patients had an early-onset myopathy characterized by mild generalized muscle weakness and pronounced ophthalmoparesis [6]. We report an unusual phenotype of neonatal-onset congenital myopathy related to a new de novo missense mutation in MYH2.

2. Case report and results

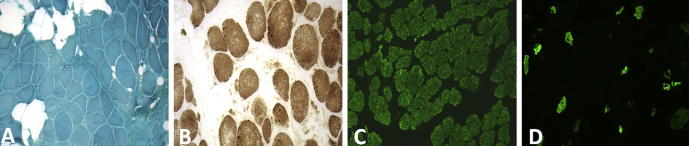

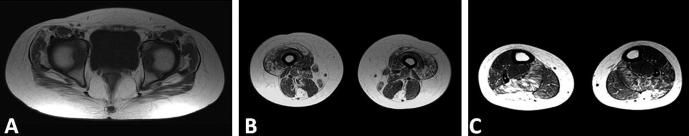

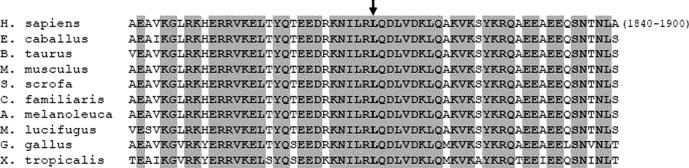

The patient is a 12-year-old Italian girl. She was the second child of healthy non-consanguineous parents. She was born at 36 weeks of gestational age by spontaneous vaginal delivery. Both amniotic fluid and fetal movements were reportedly normal. She developed severe respiratory distress during the first hour of life requiring assisted ventilation. At birth she had generalized hypotonia with preserved anti-gravity limb movements without joint contractures or limb deformities. The baby had a myopathic face with ptosis and ophthalmoparesis and she presented inability to swallow. Respiratory function progressively improved whereas severe dysphagia persisted requiring gastrostomy. CPK were normal and electromyography did not show any myotonic discharges. AChR antibodies and repetitive nerve stimulation were normal. Muscle biopsy, performed at the age of 9 months, showed marked variability in fiber size and moderate fibrosis without inflammation or necrosis. Immunochemistry for myosin isoforms showed predominance of type I fibers and few type II fibers (Fig. 1). This histological picture moved us towards a diagnosis of congenital myopathy that was over time supported by the observation of clinical gradual improvement. The baby acquired independent ambulation at the age of 2 years and swallowing problems gradually improved allowing the removal of gastrostomy at the age of 4 years. Genetic analysis for Ryanodine-Receptor 1 (RYR1), beta-tropomyosin (TPM2) and tropomyosin 3 (TPM3) genes were normal. At last clinical examination, at the age of 12 years, she still had a myopathic face with bilateral ptosis and ophthalmoplegia, arched palate and rhinolalia, waddling–steppage gait and mild dorsal scoliosis. Muscle MRI showed diffuse involvement of the thigh mainly involving vastus lateralis, rectus femoris and semitendinosus muscles. At calf level there were marked changes in the lateral head of the gastrocnemius (Fig. 2). The main clinical features of ophthalmoplegia and non-progressive myopathy prompted us to search for a MYH2 defect. We performed direct sequencing analysis of all coding exons of MYH2 (Ref. cDNA sequence NM_017534.5) disclosing a heterozygous c.5737T>C mutation in exon 39. This variant was not found in both parents and in 100 unrelated healthy controls. The prediction analysis by SIFT (sift.jcvi.org/) classified the mutation as damaging (score:0). The c.5737T>C mutation changed the strongly conserved hydrophobic leucine residue at position 1870 to proline (L1870P). L1870P is located in the highly conserved LMM domain within the myosin tail, whose staggered and tight intermolecular packing involving several myosin proteins leads to the formation of thick filaments [7]. The multiple sequence alignment of the region of MyHC IIa surrounding the Leu 1870 residue affected by mutation with a proline is shown in Fig. 3. Because proline is a potent α-helix and β-sheet structure breaker [8] it is likely that the L1870P mutation introduces a bending in the α-helical coiled coil structure in which the myosin tail is known to be organized. Distortions in this region are expected to affect the formation of myosin homodimers, because the latter require the intertwinement of the helical structures of myosins across their tail length. Such structural distortions are even amplified during the formation of thick filaments, which employ an ordered and almost parallel packing of several homodimer tails. Despite the L1870P change is located near the C-terminus of the protein, multiple sites of the L1870P mutation and related distortions are distributed at various positions within the thick filament [7] thus introducing alterations at different longitudinal points in the filaments. Moreover, despite the L1870P is heterozygous, the expression of the correctly folded MyHC IIa by the wild type allele cannot compensate the deleterious effects produced by the mutated allele. In fact, the formation of myosin filaments implies the assembly of multiple MyHC IIa proteins, which are contributed by both the wild type and mutant proteins, and thus cannot escape the deformations associated with the structurally distorted form of the protein. Finally it can be noticed that proline residues are absent in the entire α-helical coiled coil region (amino acid 845–1941) of native protein. This remarks the vulnerability of this long region of the protein to amino acid changes with proline residues and further supports the pathogenetic role of the L1870P mutation.

Fig. 1.

Muscle biopsy. Quadriceps muscle biopsy shows marked variability in fiber size with proliferation of perimysial and endomysial connective tissue without inflammation and necrosis (A). Hystochemistry for cytocorme c-oxidase does not show disorganization of the intermyofibrillar network (B). Immunochemistry for Myosin isoforms shows type I fibers predominance (monoclonal antibodies against slow type I fibers, Leica Microsystems) (C). In (D) are shown the rare and hypotrophic type II fibers (monoclonal antibody against fast type fast IIa and IIx fibers, mAb A4.74, Hybridoma Bank, The University of Iowa, Department of Biology, Iowa City).

Fig. 2.

Muscle MRI. Axial T1-weighted fast spin echo sequences of pelvic girdle, thigh and calf muscles. At the pelvic level is an evident predominant involvement of gluteus maximus and tensor fascia lata (A). At the thigh vastus lateralis, rectus femoris, semitendinosus and gracilis are mainly involved (B). At calf level there are marked changes in the lateral head of the gastrocnemius and minor involvement of soleus (C).

Fig. 3.

Sequence alignment of MyHC IIa isoform among different species. Figure shows multiple sequence alignment of MyHC IIa across species in the amino acid region 1840–1900 of the human protein. The site of the L1870P mutation is indicated by an arrow. Invariant residues are grayed.

3. Discussion

MYH2-related myopathy is the first human myopathy reported to be associated with a mutation in one of the skeletal muscle-specific MyHC isoforms. We report a congenital myopathy related to a new pathogenetic missense mutation in the MYH2 that, to the best of our knowledge, represents the fourth MYH2 missense mutation reported so far. As in previously reported cases our patient had the invariable clinical feature of external ophthalmoplegia, but despite the severe neonatal presentation she did not present joint contractures. It has been previously suggested that the expression of MyHCs is developmentally regulated and the presence of joint contractures is related to fetal expression of MyHC IIa [9]. The absence of joint contractures in our case could be explained by the fact that in our patient limb movements were reported to be normal in utero. Severe dysphagia has never been reported in MYH2-related myopathies. Although this feature appears to be unusual it is not surprising because genioglossus and other extrinsic tongue muscles exhibit a high expression of MyHC IIa [10,11]. In the first reported family harboring the p.E706K mutation muscle biopsies of young patients showed minor changes consisting in few small type IIa muscle fibers with irregular intermyofibrillar network. However in patients with long lasting clinical course muscle specimens showed dystrophic changes and it has been demonstrated that the degree of these pathological findings was proportional to the level of MyHC IIa expression [9]. Because it is known that the expression of MyHC IIa increases with age this observation explains the progressive course of the disease in adulthood and confirms the dominant negative effect of the p.E706K mutation. In our young patient, as expected, muscle biopsy showed minimal changes consisting in very few and small type II fibers. Muscle MRI has been only reported in 2 patients harboring recessive MYH2 mutations [6] showing diffuse fatty infiltration with an unusual pattern of predominant involvement of medial gastrocnemius in the lower legs, combined with predominant involvement of the semitendinosus, gracilis and vastus lateralis muscles in the thigh. Also in our patient muscle MRI showed in the thigh predominant involvement of vastus lateralis and semitendinosus muscles. In contrast at calf level we observed marked changes in the lateral head of the gastrocnemius. Finally, the pathogenetic role of L1870P mutation is supported by the following considerations: (1) non-pathogenic variants in MYH2 are very rare considering the strong selective pressure against mutations in this gene demonstrated by Tajshargi and colleagues [5]; (2) the mutation arose de novo in the family and it was not found in a large set of control chromosomes; (3) in silico analyses predicted the new amino acid substitution to be pathological and “probably” damaging; (4) the L1870P mutation interrupts the continuity of the coiled coil structure influencing the contact with nearby myosins within thick filaments. In conclusion we have reported detailed clinical, muscle imaging, genetic findings and expected effects on the protein structure of the second dominant mutation in the MYH2 expanding the clinical and genetic spectrum of this very rare disease. We suggest that a MYH2 defect should be ever considered in a congenital myopathy associated to extraocular muscular involvement also in absence of congenital joint contractures.

Acknowledgements

The financial support of Telethon – Italy (Grant no. GUP08005) and of the Ministry of Health (Grant Finalizzata code GR-2010-2310981) are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Oldfors A. Hereditary myosin myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(5):355–367. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.02.008. 2007 Apr 16. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smerdu V., Karsch-Mizrachi I., Campione M., Leinwand L., Schiaffino S. Type IIx myosin heavy chain transcripts are expressed in type IIb fibers of human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:1723–1728. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.6.C1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinsson T., Oldfors A., Darin N. Autosomal dominant myopathy: missense mutation (Glu-706 → Lys) in the myosin heavy chain IIa gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(26):14614–14619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250289597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Darin N., Kyllerman M., Wahlström J., Martinsson T., Oldfors A. Autosomal dominant myopathy with congenital joint contractures, ophthalmoplegia, and rimmed vacuoles. Ann Neurol. 1998;44(2):242–248. doi: 10.1002/ana.410440215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tajsharghi H., Darin N., Rekabdar E. Mutations and sequence variation in the human myosin heavy chain IIa gene (MYH2) Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13(5):617–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tajsharghi H., Hilton-Jones D., Raheem O., Saukkonen A.M., Oldfors A., Udd B. Human disease caused by loss of fast IIa myosin heavy chain due to recessive MYH2 mutations. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1451–1459. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Craig R., Woodhead J.L. Structure and function of myosin filaments. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16(2):204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.03.006. Epub 2006 Mar 24. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li S.C., Goto N.K., Williams K.A., Deber C.M. Alpha-helical, but not beta-sheet, propensity of proline is determined by peptide environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6676–6681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tajsharghi H., Thornell L.E., Darin N. Myosin heavy chain IIa gene mutation E706K is pathogenic and its expression increases with age. Neurology. 2002;58(5):780–786. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daugherty M., Luo Q., Sokoloff A.J. Myosin heavy chain composition of the human genioglossus muscle. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2012;55(2):609–625. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0287). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sokoloff A.J., Daugherty M., Li H. Myosin heavy-chain composition of the human hyoglossus muscle. Dysphagia. 2010;25(2):81–93. doi: 10.1007/s00455-009-9227-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]