Abstract

Species may exhibit similar thermal tolerances via either common ancestry or environmental filtering and local adaptation, if the species inhabit similar environments. We ask whether upper and lower thermal limits (critical thermal maxima and minima) and body temperatures are more strongly conserved across evolutionary history or geography for lizard populations distributed globally. We find that critical thermal maxima are highly conserved with location accounting for a higher proportion of the variation than phylogeny. Notably, thermal tolerance breadth is conserved across the phylogeny despite critical thermal minima showing little niche conservatism. Body temperatures observed during activity in the field show the greatest degree of conservatism, with phylogeny accounting for most of the variation. This suggests that propensities for thermoregulatory behaviour, which can buffer body temperatures from environmental variation, are similar within lineages. Phylogeny and geography constrain thermal tolerances similarly within continents, but variably within clades. Conservatism of thermal tolerances across lineages suggests that the potential for local adaptation to alleviate the impacts of climate change on lizards may be limited.

Keywords: critical thermal limits, environmental niche, space, phylogeny

1. Introduction

Similarities in species' thermal niches across evolutionary history (phylogenetic niche conservatism [1]) and geography can aid in forecasting responses to climate change. Thermal physiology and the magnitude of recent warming successfully predict patterns of recent lizard extinction, potentially owing to climate change restricting the activity of species with low upper thermal limits [2]. Lizard thermal physiologies exhibit conservatism across both phylogeny and geography as some forest-dwelling, non-basking lineages remaining restricted to the tropics and open-habitat, basking lineages extending into temperate zones [3]. Lineages with phylogenetically conserved thermal tolerances may be unlikely to adapt locally to climate change. Species with strong geographical gradients in thermal tolerance may be more likely to use dispersal and adaptation to track their environmental niches through climate change.

Does evolutionary history or geography better explain global patterns of lizard thermal physiology? We use a statistical method [4] to partition variance into spatial and phylogenetic contributions for the following four thermal metrics. We consider the upper and lower thermal limits on performance (CTmax and CTmin), which ranges from 33.4°C to 51.0°C and 1.9°C to 14.1°C respectively, as well as the distance (°C) between these limits (thermal tolerance breadth, TTB). CTmax and CTmin determine how the environment influences fitness as well as susceptibility to acute thermal stress [5]. We additionally consider activity body temperature (Tb), which range from 14.5°C to 42.1°C. While Tb is sometimes used as a more readily available proxy for thermal tolerances [2], it is additionally influenced by microclimate selection. The propensity for such thermoregulatory behaviour may be phylogenetically conserved, and may enable coping with climate change through environmental buffering [6]. Conversely, this buffering may reduce selection for elevated CTmax [7] and ultimately preclude the evolutionary responses necessary to cope with long-term climate change.

Broad-scale patterns of temperature means and seasonality both pose strong selection on thermal physiology [3,5,8]. Indeed, the CTmax of reptiles relates to thermal variability, whereas CTmin relates to mean annual temperature [9]. The limited temperature seasonality in the tropics selects for reduced TTB [3,5]. We first use distance as a proxy (‘geographical space’) for environmental similarity as location captures trends in both means and seasonality. We then examine environmental similarity directly.

2. Material and methods

We analysed 481 Tb measures for 254 lizard species from 34 families [2] (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). We expanded a previous database [8] to include CTmax, CTmin and TTB values for 68, 60 and 60 species, respectively (see the electronic supplementary material, table S2). We used a supertree of squamate reptiles constructed using matrix representation parsimony analysis and dated based on fossils and molecular data [10]. For each observation, we extracted annual means of daily minimum, mean and maximum air temperatures as well as seasonality calculated as the variance of monthly mean temperatures (0.5° resolution, which is sufficient resolution to account for broad elevational differences, IIASA database A03). We additionally combined these measures into a single principle component describing the environment (‘temperature space’).

We conducted our analysis in R v 2.13.1 [11] using the package APE [12]. We determined the relative contribution of space and phylogeny to variation in each metric using a method derived from phylogenetically independent contrasts (PIC) [4]. The following method (equation (2.7) of [4]) produces three positive parameter estimates (φ, λ′ and γ), which sum to 1 and describe the variance in the metric as follows:

| eqn 2.7 in [4] |

Here, φ represents the relative contribution of spatial effects, λ′ = (1 – φ)λ represents the relative phylogenetic contribution, and γ = (1 – φ)(1 – λ) represents the relative contribution of effects independent of both phylogeny and space. V, Σ and W are variance–covariance matrices describing the expectation, phylogenetic distances and spatial distances, respectively. h is a vector of the heights of tips on the phylogeny. The λ used in calculating λ′ is Pagel's [13] estimate of phylogenetic signal. We additionally estimate Blomberg's K because it is a commonly implemented metric that indicates the amount of phylogenetic signal in the tip data relative to the expectation (K = 1) for a trait that evolved by Brownian motion [14]. We assessed significance by comparing the variance of independent contrasts for 1000 randomized (tip-swapped) trees with that of the observed trees (phylosignal function in R package picante). We computed PIC to examine correlations between the thermal metrics (R package APE). Correlations were estimated based on 1000 iterations to account for randomization.

Because the analysis requires a binary phylogeny, we resolved polytomies using a birth–death model of diversification (methods follow [15]) and repeated the analyses over 2500 potential phylogenies. Tb values were randomly selected (when multiple values were available for a single species) for each of the potential phylogenies. We estimated φ, λ′ and γ assuming that the traits followed a gradual Brownian motion model of evolution (branch lengths proportional to time).

3. Results and discussion

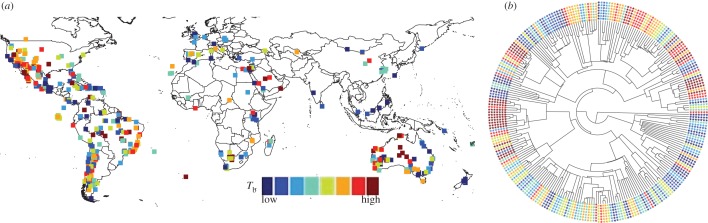

We find that body temperatures are less conserved across geography than evolutionary history (figure 1). Phylogeny accounts for most of the variation in Tb patterns (φ = 0.087, λ′ = 0.877 and γ = 0.036, figure 2). The strong phylogenetic signal of Tb (K = 1.075, p = 0.001) is notable because one would expect body temperatures to be strongly influenced by air and surface temperatures, which exhibit pronounced geographical gradients. However, many lizard species are able to maintain their preferred body temperatures through behavioural thermoregulation and habitat selection [16–18]. The propensity for thermoregulatory behaviour varies between lineages [3], but its phylogenetic conservatism has not been formally assessed.

Figure 1.

Activity body temperatures (Tb) for lizards are less conserved across (a) geography than (b) phylogeny (with blue to red depicting eight quantiles from low to high).

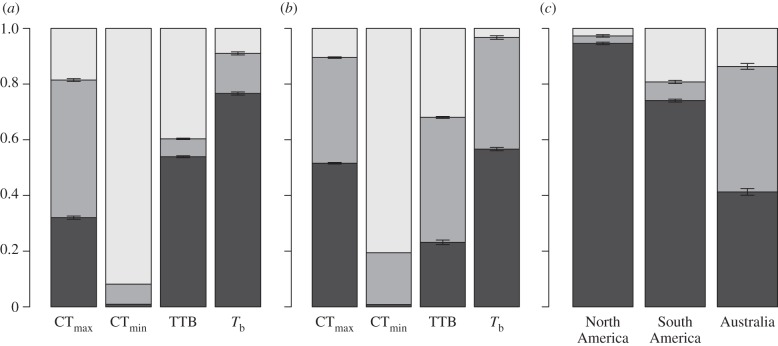

Figure 2.

The stacked contributions of phylogeny (φ, black) and space (λ′, grey) to patterns of thermal tolerance vary by metric (unaccounted for variance: γ, light grey). 95% CIs across the randomizations are depicted. We depict the contributions when characterizing both (a) geographical and (b) (mean annual) temperature space. We additionally analyse the determinants of body temperature (Tb) within continents.

The influence of phylogeny and geography varies between thermal tolerance metrics. Space accounts for more variation in CTmax than phylogeny (φ = 0.549, λ′ = 0.270 and γ = 0.181; figure 2a). CTmin shows little conservatism across either phylogeny or space (φ = 0.073, λ′ = 0.009 and γ = 0.917). Interestingly, TTB shows a greater contribution of phylogeny than either CTmax or CTmin (φ = 0.083, λ′ = 0.547 and γ = 0.369). CTmax (K = 0.585, p = 0.001), CTmin (K = 0.427, p = 0.02) and TTB (K = 0.458, p = 0.002) exhibit significant phylogenetic conservatism, but to a lesser extent than Tb. A previous, counterintuitive result is that both CTmin and CTmax increase with latitude, because many temperate lizards are basking species that inhabit warm and thermally variable desert environments [3]. The conservation of thermoregulatory behaviour across lineages may alter selection and thus geographical patterns of thermal tolerance. Patterns of conservatism are similar when we consider temperature space rather than geography (see figure 2b and electronic supplementary material, table S3) with several exceptions. Habitat selection may cause more thermal similarity than would be expected based on geography and account for these exceptions. Indeed, environmental temperatures account for more of the variation in Tb and TTB than geography.

We used PIC (standardized) to investigate why TTB exhibits greater phylogenetic conservatism than CTmax or CTmin (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S1). We find that lizards have a broad TTB owing to either a low CTmin (F1,52 = 117, p < 10−15 and r2 = 0.69) or high CTmax (F1,52 = 18.2, p < 10−4 and r2 = 0.26). However, CTmin and CTmax are not correlated (p = 0.70). We find that Tb is positively correlated with CTmax (p < 0.01, r2 = 0.56) but is not related to CTmin (p = 0.4). These findings suggest that narrow TTB, which confers sensitivity to climate warming, is not associated with a particular range of thermal tolerance. The importance of the thermal metrics as determinants of activity time and thermal stress varies latitudinally, and is likely to shift through climate warming: CTmin may become less important as a constraint on activity in temperate areas, whereas CTmax is likely to become increasingly important as a determinant of thermal stress in the tropics [6].

Is Tb conservatism similar within geographical and phylogenetic subsets (see figure 2c and electronic supplementary material, table S3)? The importance of phylogeny persists within North America (n = 71, φ = 0.027, λ′ = 0.946 and γ = 0.027) and South America (n = 40, φ = 0.067, λ′ = 0.741 and γ = 0.192). Greater conservatism across geographical and temperature space occurs in Australia, perhaps owing to its pronounced aridity gradient (n = 62, φ = 0.451, λ′ = 0.413 and γ = 0.136 for geographical space). Patterns of conservatism are more variable across clades (defined by Sites et al. [19]). Conservatism was substantially stronger across phylogeny than geography for the Anguimorpha (n = 23) and Scincoidea (n = 67) clades, and somewhat stronger for Lacertoidea (n = 36). Estimates of conservatism varied between geographical and temperature space for Iguania (n = 96), and were generally low for Gekkota (n = 27). These results suggest that thermoregulatory behaviours diverged deep within the lizard phylogeny and have persisted through colonization and radiations on different continents. The thermal niches of ants (λ ∼ 0.9) [20] and amphibians [21] also exhibit phylogenetic conservatism, whereas geography is more important for mammals [22].

Our analysis suggests that thermal tolerances are conserved deep within evolutionary history rather than being determined by ecological filtering, dispersal, or local adaptation (perhaps due to limits to adaptation). The potential for local adaptation to alleviate the impacts of climate change on lizards may be limited [23] particularly in the tropics [3,17], where narrow TTBs can correspond to low genetic variation and limited evolutionary potential [24]. However, strong phylogenetic signal in body temperatures suggests that some lineages may effectively use thermoregulation to avoid thermal stress [6].

Acknowledgements

We thank Rob Freckleton for contributing R code, and J. Kingsolver, G. Thomas, members of the Buckley and Kingsolver research groups and reviewers for comments. Work supported in part by NSF grant no. EF-1065638 to L.B.B.

References

- 1.Wiens JJ, et al. 2010. Niche conservatism as an emerging principle in ecology and conservation biology. Ecol. Lett. 13, 1310–1324 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01515.x (doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01515.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sinervo B, et al. 2010. Erosion of lizard diversity by climate change and altered thermal niches. Science 328, 894–899 10.1126/science.1184695 (doi:10.1126/science.1184695) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huey RB, Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Vitt LJ, Hertz PE, Álvarez Pérez HJ, Garland T. 2009. Why tropical forest lizards are vulnerable to climate warming. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 1939–1948 10.1098/rspb.2008.1957 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1957) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freckleton RP, Jetz W. 2009. Space versus phylogeny: disentangling phylogenetic and spatial signals in comparative data. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 21–30 10.1098/rspb.2008.0905 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0905) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deutsch CA, Tewksbury JJ, Huey RB, Sheldon KS, Ghalambor CK, Haak DC, Martin PR. 2008. Impacts of climate warming on terrestrial ectotherms across latitude. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6668–6672 10.1073/pnas.0709472105 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0709472105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearney M, Shine R, Porter WP. 2009. The potential for behavioral thermoregulation to buffer ‘cold-blooded’ animals against climate warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3835–3840 10.1073/pnas.0808913106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0808913106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huey RB, Hertz PE, Sinervo B. 2003. Behavioral drive versus behavioral inertia in evolution: a null model approach. Am. Nat. 161, 357–366 10.1086/346135 (doi:10.1086/346135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sunday JM, Bates AE, Dulvy NK. 2010. Global analysis of thermal tolerance and latitude in ectotherms. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 1823–1830 10.1098/rspb.2010.1295 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1295) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clusella-Trullas S, Blackburn TM, Chown SL. 2011. Climatic predictors of temperature performance curve parameters in ectotherms imply complex responses to climate change. Am. Nat. 177, 738–751 10.1086/660021 (doi:10.1086/660021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergmann PJ, Irschick DJ. 2011. Vertebral evolution and the diversification of squamate reptiles. Evolution 66, 1044–1058 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01491.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01491.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.R Core Development Team 2012. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. 2004. APE: analyses of phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics 20, 289–290 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pagel M. 1999. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature 401, 877–884 10.1038/44766 (doi:10.1038/44766) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blomberg SP, Garland T, Ives AR. 2003. Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution 57, 717–745 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00285.x (doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00285.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhn TS, Mooers AØ, Thomas GH. 2011. A simple polytomy resolver for dated phylogenies. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2, 427–436 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00103.x (doi:10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00103.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seebacher F, Shine R. 2004. Evaluating thermoregulation in reptiles: the fallacy of the inappropriately applied method. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 77, 688–695 10.1086/422052 (doi:10.1086/422052) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tewksbury JJ, Huey RB, Deutsch CA. 2008. Putting the heat on tropical animals. Science 320, 1296–1297 10.1126/science.1159328 (doi:10.1126/science.1159328) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huey RB, Tewksbury JJ. 2009. Can behavior douse the fire of climate warming? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3647–3648 10.1073/pnas.0900934106 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0900934106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sites JW, Jr, Reeder TW, Wiens JJ. 2011. Phylogenetic insights on evolutionary novelties in lizards and snakes: sex, birth, bodies, niches, and venom. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 42, 227–244 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145051 (doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145051) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond SE, Sorger DM, Hulcr J, Pelini SL, Toro ID, Hirsch C, Oberg E, Dunn RR. 2012. Who likes it hot? A global analysis of the climatic, ecological, and evolutionary determinants of warming tolerance in ants. Glob. Change Biol. 18, 448–456 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02542.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02542.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hof C, Rahbek C, Araújo MB. 2010. Phylogenetic signals in the climatic niches of the world's amphibians. Ecography 33, 242–250 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06309.x (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06309.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper N, Freckleton RP, Jetz W. 2011. Phylogenetic conservatism of environmental niches in mammals. Proc. R. Soc. B 278, 2384. 10.1098/rspb.2010.2207 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.2207) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angilletta MJ. 2009. Thermal adaptation: a theoretical and empirical synthesis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kellermann V, Van Heerwaarden B, Sgrò CM, Hoffmann AA. 2009. Fundamental evolutionary limits in ecological traits drive Drosophila species distributions. Science 325, 1244–1246 10.1126/science.1175443 (doi:10.1126/science.1175443) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]