Abstract

Objective

This article sought to define whether an alternative safety-engineered device (SED) could help prevent needlestick injury (NSI) in healthcare workers (HCWs) who place central venous catheters (CVCs).

Design

The study involved three phases: (1) A retrospective analysis of deidentified occupational health records from our tertiary care urban US hospital to clearly identify NSI risk and rates to an HCW during invasive catheter placement; (2) 95 residents were surveyed regarding their knowledge and experience with NSIs and SEDs; (3) A random sample of six residents participated in a focus group session discussing barriers to the use of SED.

Setting

A single urban US tertiary care teaching hospital.

Participants

A retrospective analysis of NSI to HCWs in a tertiary care urban US hospital was conducted over a 4-year period (July 2007–June 2011). Ninety-five residents from specialties that often place CVC during training (surgery, surgical subspecialties, internal medicine, anaesthesia and emergency medicine) were surveyed regarding their experience with NSIs and SEDs. A random sample of six residents participated in a focus group session discussing barriers to the use of SED.

Results

314 NSIs were identified via occupational health records. 16% (21 of 131) of NSIs occurring in residents and fellows occurred during the securement of an invasive catheter such as a CVC. If an SED device had been used, the 5.25 NSIs/year could have been avoided. Each NSI occurring in an HCW incurred at least $2723 in charges. Thus, utilisation of the SED could have saved a minimum of $57 183 over the 4-year period.

Conclusions

SEDs are currently available and can be used as an alternative to sharps. If safety and efficacy can be demonstrated, then implementation of such devices can significantly reduce the number of NSIs.

Keywords: Accident & Emergency Medicine, Medical education & Training

Article summary.

Article focus

This article sought to determine whether an alternative safety-engineered device (SED) could potentially prevent needlestick injury (NSI) in healthcare workers (HCWs) who place central venous catheters (CVC). It also aims to identify potential reasons why an available SED is not utilised by HCW. To begin to answer these questions, the study involved three phases:

A retrospective analysis of deidentified occupational health records from our tertiary care urban US hospital to clearly identify how many HCW had NSI while placing CVC.

Ninety-five residents who frequently place CVC during training were surveyed regarding their knowledge and experience with NSIs and SEDs.

A random sample of six residents participated in a focus group session discussing the barriers to the use of SED.

Key messages

Sixteen per cent (21 of 131) of NSIs occurring in residents and fellows over a 4-year period (July 2007 to June 2011) in a single institution occurred during securement of an invasive catheter despite a readily available SED that would eliminate the need for sharps during this part of invasive catheter insertion.

If safety and efficacy of the device can be proven, 5.25 HCW NSIs per year could be avoided at our institution. This would translate into a savings of at least $57 183 in charges associated with NSIs over the 4-year period.

Introduction of SED in a hospital should be accompanied by education, detailed information and training of HCWs to encourage utilisation of the device.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A notable strength of this work is that it addresses the International Healthcare Worker Safety Center March 20121 call to action to address a lack of new progress in NSI rates. The study identifies a new area where significant progress may be made to reduce sharps injuries worldwide.

A significant limitation is that the study is currently limited to a single US tertiary care site.

Introduction

Needlestick or sharps injuries (NSIs) among healthcare workers (HCWs) are a common and potentially avoidable injury. An estimated 600 000–800 000 percutaneous injuries occur annually among HCWs in the USA.2 As high as these estimates appear, the literature indicates that sharps injuries are significantly under-reported.3–5 These injuries place HCWs at risk for blood-borne infections and result in considerable psychological distress. In addition, the healthcare system incurs substantial costs from the occupational health testing, prophylaxis and follow-up that must be implemented for each reported NSI.

Safety-engineered devices (SEDs) are promising design innovations intended to prevent hazards and accidents. In medicine, numerous engineering controls have been introduced to decrease the incidence of NSIs among HCWs, including safety-winged steel needles, safety-intravenous catheter insertion needles and many others.

The StatLock device (Bard Access Systems, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA; figure 1) is an SED designed to prevent NSIs during placement of central venous catheters (CVCs). It is a locking device that secures CVCs to the skin with benzoin adhesive instead of the traditional method of using sutures to secure CVCs to skin. Traditionally, after a CVC is placed, the patient may require additional local anaesthesia in a site separate from the insertion site, necessitating the use of a hollow-bore needle for lidocaine injection. Then, a straight suture needle is used to suture the CVC to the patient's skin. After making a knot with the suture, the ends are then cut with a scalpel. Therefore, using the SED minimises the risk of NSI during securement of CVC by eliminating three steps during which sharps are used. Despite the easy availability of the StatLock device, few resident physicians are aware of it and fewer still have used it in clinical practice.

Figure 1.

Right infraclavicular subclavian triple-lumen catheter secured with StatLock needleless device (Bard Access Systems, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA). The StatLock needleless device replaces the need for suturing with a locking device secured with benzoin and tape.

This SED has been available in all adult triple-lumen CVC kits in our urban tertiary care US institution since July 2009. Despite its availability, the SED is not widely used in clinical practice. The purpose of our study was to perform a needs analysis by retrospectively examining HCWs’ data from our institution to determine whether implementation of the SED would significantly reduce NSIs. We sought to determine whether practitioners did incur NSIs during the securement phase of the CVC procedure, and if this could have been prevented with the use of this SED. Since this SED device has already been readily available in the safety-triple lumen catheter kits within the institution, but not yet utilised on a regular basis, we also sought to identify the potential barriers to the implementation of a new SED in the healthcare environment.

We hypothesised that a substantial number of NSIs occur during the resident placement of CVCs and could potentially be prevented by the use of SED. However, barriers to the utilisation of this SED, including the lack of training on the use of the device and staff resistance, are likely to impede the implementation of safety controls. This work addresses the International Healthcare Worker Safety Center 20121 call to action to address a lack of new progress in NSI rates.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained and all NSI data were deidentified. The study was conducted at Hahnemann University Hospital (HUH), an urban tertiary care hospital in the USA. We analysed retrospective data on all NSIs reported between July 2007 and June 2011 by HCWs in the adult-care ACGME resident training programmes (except neurosurgery).

NSI cost was determined by adding the required charges for a ‘minimal risk’ NSI. For the purpose of this study, a minimal risk NSI was defined as an NSI for which the HCW has a low risk for seroconversion to hepatitis or HIV viral infection. When this type of NSI occurs, both the HCW and source patient would be tested for HIV and hepatitis B and C immediately after the NSI. The sum of the charges for the required occupational health appointments and initial lab tests represents the lowest possible cost of an NSI in USD. When the potential risk of transmission of hepatitis or HIV infection is considered greater, an HCW may be prescribed prophylactic medications and requires repeated testing at regular intervals up to a year after a NSI, significantly increasing the costs associated with NSI.

Ninety-five residents from surgery, emergency medicine, internal medicine and anaesthesia programmes, the disciplines responsible for CVC placement at our institution, were identified and enrolled in the study. All participants signed written consent to participate. Demographic data for each of the residents were collected, including the level of training, department, age, sex, race and handedness. Survey questions were designed to determine the residents’ prior exposure to NSIs and to evaluate their prior knowledge of and experience with the StatLock device.

Finally, a focus group of six randomly selected residents was conducted to assess the impressions of the device and to identify the potential barriers to its implementation. Participants were interviewed by a study investigator (SG) individually and each session was audio recorded with the permission of the participant. During the focus group sessions, participants were asked to discuss their impressions of the SED and the additional thoughts they had on the use of this alternative method as compared with traditional sutures when securing central lines. These discussions were recorded so that they could be later analysed by two independent study investigators (SG and AB).

Data analysis

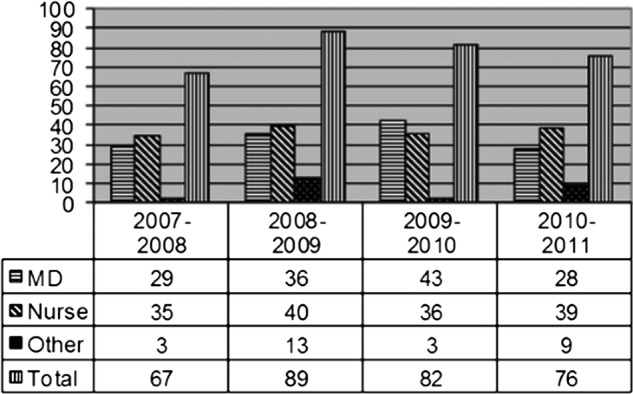

Deidentified data on all NSIs occurring at our institution were independently reviewed by three study investigators (SG, AB and CJR). All reported NSIs were reviewed and characterised according to the occupation of the HCW incurring the injury (figure 2) and according to the circumstances regarding the injury. Frequency counts of physician NSIs that occurred during a catheter placement such as a CVC, large bore single lumen catheter, dialysis catheter or arterial catheter line were also reviewed by the same three investigators and compared for agreement in interpretation. After the focus group sessions, two independent study investigators categorised the residents’ statements as neutral, positive or negative observations regarding the StatLock device.

Figure 2.

Needlestick injury at Hahnemann Hospital by occupation from 4-year period: 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2011. MD includes residents, attendings and fellows. Nurse includes nurses, nurse anaesthesia and nurse practitioners. Others include respiratory therapy, environmental services, laboratory personnel and others not categorised above.

Results

Retrospective institutional data analysis

Analysis of the retrospective NSI data revealed that physicians (residents, fellows and attendings) accounted for 43% (136 of 314) of the total NSIs occurring between July 2007 and June 2011 (figure 2). Resident NSIs accounted for 87% (118 of 136) of the total physician NSIs occurring during this 4-year period. Analysis of the circumstances surrounding each NSI showed that 40 NSIs occurred during the placement of CVCs or other catheter lines that required securement to patient skin. Fifty-three per cent (21 of 40) of the NSIs that occurred during these procedures occurred specifically while the line was being secured to the patient's skin with a suture needle. This accounted for 16% (21 of 131) of the total number of NSIs occurring in residents and fellows over the 4-year period. It is possible that 13 additional NSIs occurred during the securement of these catheter lines; but, unless our occupational health record specifically documented that the NSI occurred while the worker was securing the line to the patient's skin, those data were not included. The remaining six NSIs that occurred during the placement of a CVC or other invasive catheter occurred with the large-bore needle while the physician was attempting to cannulate the vessel.

Cost analysis

Given the number of NSIs determined from retrospective analysis, we calculated that the use of a needleless device to secure the CVC could have prevented 21 NSIs. The cost analysis estimates that each NSI incurs at least US$2723 in charges at this institution. Table 1 lists the minimal charges associated with a low-risk NSI using data from our institution's Occupational Health Clinic. While the calculations for this study represent the lowest possible cost of an NSI, the actual cost of an NSI varies from case to case depending on the circumstances surrounding the NSI, the treatment plan, medication requirements and frequency of follow-up visits. If the HCW has a high risk exposure to HIV, prophylactic antiviral medications must be prescribed and the cost of the medications, additional laboratory studies and frequent follow-up visits increase the cost of the NSI significantly. The cost estimates also do not include the indirect cost of time lost from work and other indirect financial and social costs. Eliminating all 21 NSIs that definitively occurred during the securement of a CVC would have translated into a savings of at least $57 183 in US dollar charges. If the additional 13 NSIs that possibly occurred during the securement phase were also prevented, the cost savings would be at least $92 582 over the 4-year period.

Table 1.

Needlestick injury costs per incident occupational health charges

| 2011 USD charges for ‘minimal risk’ HCW exposure | Additional charges if more follow-up visits deemed necessary | |

|---|---|---|

| Office visit (during weekday business hours) | ||

| Initial visit | $240 | |

| Each additional follow-up visit | $76 | |

| Lab costs | ||

| HIV 1,2 antibody test | ||

| Initial source patient | $533 | |

| HCW testing at baseline and each follow-up interval | $533 | |

| Hepatitis B panel | ||

| Initial source patient | $511 | |

| HCW testing at baseline and each follow-up interval | $511 | |

| Hepatitis C panel | ||

| Initial source patient | $863 | |

| HCW testing at baseline and each follow-up interval | $863 | |

| Total cost | $2732 | Varies by number of follow-up visits required |

HCW, healthcare worker.

Survey of residents

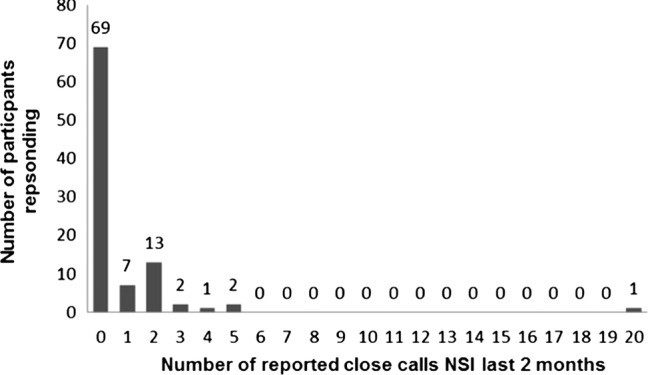

Of the 95 residents surveyed, only 30% had previous knowledge of the needleless SED that is supplied in all CVC safety kits at our institution. Only 19% had ever had training regarding the use of any SED or used the device in clinical practice. Twenty-seven per cent of residents surveyed stated that they had had at least one close call needlestick incident in the past 2 months. And, 20% of the residents surveyed had at least two near miss/close call needlestick incident in the past 2 months (figure 3). Twenty-five per cent of the responding residents (24 of 95) answered yes when asked the question, ‘Have you ever had a needlestick injury associated with patient body fluid exposure?’ In a follow-up question, we asked, ‘Did you report the incident each time?’ Twenty-one per cent (5 of 24) responded that they did not always report NSI. This finding is consistent with the prior data suggesting that HCW NSIs are under-reported.3–6

Figure 3.

Close calls involving needlestick injuries witnessed in the 2-month preceding survey administration in July 2011.

Focus group data

Data from discussions with six randomly selected study participants are presented in table 2. Statements regarding each resident's experience with StatLock were categorised into positive, negative or neutral. Opinions about the SED and experiences varied across participants. In general, those residents who were comfortable and adept at suturing, especially surgical residents, seemed to prefer using sutures over the StatLock device. According to the responses, the use of the SED may also be dependent on patient characteristics, situational circumstances and knowledge or acceptance of the SED by other HCWs. One resident indicated that she would want additional practice with the device before using it in a clinical setting, suggesting that additional training may encourage increased use of the SED.

Table 2.

Data extracted from six randomly selected focus group participants

| Neutral comments | Positive comments | Negative comments |

|---|---|---|

| [I] would want more practice with applying the StatLock device before using it in a clinical setting | “[I] am motivated to use StatLock after witnessing multiple coworkers experience fingersticks | Time is of the essence. [I] don't want to wait for StatLock to dry when sutures are faster, more efficient, more comfortable |

| After using the StatLock device just one time, one resident found that the placement of the StatLock device was quicker than suturing the CVC | Some residents were hesitant to use the device because the nurses and other practitioners lacked knowledge of the device | |

| Two of the 6 residents reported that they valued the StatLock device in certain situations when they were more likely to incur an NSI. One stated this was particularly useful when the patient is unpredictable or unwilling to lie still | The admitting team was confused, did not know what device was, and [was] concerned over whether StatLock would stay in place | |

| One stated that the device may be useful especially for patients who form keloids | Resistance to StatLock due to familiarity with suturing, especially among surgical residents |

Discussion

In 2009, we developed a partnership with our institutional industrial hygienist to investigate opportunities to reduce NSIs among resident physicians in our institution. In the fiscal year between 2008 and 2009, nurse NSIs increased 10% and physician NSIs increased 70% at our institution. In 2009 at HUH, 46% of the total reported NSIs involved residents. A 2007 study of 699 surgical residents at 17 US medical centres found that by the fifth year of residency, 99% had had at least one NSI. Moreover, for 53% of respondents, the NSI had involved a high-risk patient with a history of HIV infection, hepatitis B or C virus infection or injection drug use.2 In 2009, our US-based urban hospital reported 27.6 injuries/100 occupied beds, which is above the EPINet average of 20.1 for teaching hospitals.7 Despite increased awareness of sharps injuries and some attempts at prevention, NSIs continue to be a serious problem. Our study supported earlier research findings that among HCWs, physicians have the highest risk of NSI,2 8 and among physicians, residents have a three times greater risk of blood and body fluids exposure than senior doctors.9 These data were alarming and required immediate analysis for the potential for intervention.

In medicine, engineering controls that have been introduced to decrease the incidence of NSIs among HCWs include safety-winged steel needles, safety intravenous catheter insertion needles, polyester film-coated capillary tubes, safety-shielded phlebotomy needles, needleless blood transfer devices, safety peripherally inserted central catheter stylets, blood gas needle-holding devices, blunt-tip needles and shielded hypodermic needles/syringes.10 Current literature indicates that 29–35% of the reported occupational NSIs could have been prevented if an SED had been used.11 Although engineering controls may require capital investment, the cost savings resulting from improved safety may justify the expense. However, devices that depend on user activation generate benefit only when correctly used; thus, HCWs must be educated in their use.

For some HCWs, their lack of training and their unfamiliarity with SEDs are major barriers to its use. Only 30% in our study had previous knowledge of the needleless SED that is supplied in all CVC safety kits at our institution. Only 19% had ever used the device in clinical practice. Exposure to the SED and effective training may encourage the use of SEDs and subsequently reduce NSI. A prospective cohort study using the same 95 residents who participated in this survey has been designed to determine the best means of educating residents on the use of the StatLock device. Each resident was randomly assigned to either a standard teaching video or a simulation curriculum involving both the video teaching plus hands-on practice in a simulated clinical environment. The endpoint for the longitudinal phase of the study was defined as a difference in NSIs between the groups. Additionally, all participants agreed to return in 12 months for a repeat questionnaire on their attitudes and experience with the SED. This portion of the study is still in progress.

In our institution, some physicians familiar with the SED have been reluctant to use it because of potential patient safety concerns. Some express apprehension that the device is not as effective as the traditional method of securing a CVC to patients' skin using sutures. The manufacturer advises concern if a patient is too sweaty, bloody or hairy. Hence it is difficult to implement an alternative device that cannot be used in every patient. Lastly, some reports in the literature claiming efficacy to suture securement have been associated with the SED manufacturers, raising the question of potential bias. The StatLock device is currently available in every triple-lumen CVC kit in our institution. Therefore, the issue of use of the device does not rest on its availability, but rather on physician awareness, training and preference.

Focus group discussions revealed that such factors have indeed presented barriers to the implementation of SED. Residents expressed concerns regarding time constraints and familiarity with device. Previous literature has documented similar barriers to the implementation. Cost, personnel time and resistance to change are several of the most commonly documented deterrents.6 12–16 Surgeons and anaesthesiologists have been recognised as the cohorts least likely to use safety devices designed to prevent NSIs, presumably because they are skilled at suturing.17Reluctance may also stem from feelings of discomfort and questions of efficacy.17 Evidence-based reasoning is often absent from the foundation of implementation programmes, exacerbating opposition to change.18 Perpetual access to conventional sharps also hinders the implementation of safety devices.19

Some institutions have recognised that simple logistics can prevent staff from using SEDs. Contractual purchasing agreements can render devices unavailable and certain devices may not be compatible with the existing equipments.6 16 The overabundance of SEDs on the market makes it difficult for the institutions to choose,15 yet most devices are not applicable for all situations and technology must become more advanced to meet the remaining demand.15 18

Lastly, HCWs are characterised as being desensitised to disease and consequently possessing a false sense of security regarding the effects of NSIs.17 When this complacency is coupled with a lack of multidisciplinary support, both ‘horizontally and vertically,’ the implementation of safety devices becomes extremely difficult.20

Conclusions

The common incidence of NSIs among HCWs clearly indicates a need for further intervention. Retrospective analysis of institutional records demonstrated that over a 4-year period (July 2007–June 2011), 16% of resident/fellow NSIs (21 of 131) could have been avoided with the use of a needleless securement device such as the StatLock device. While such SEDs are currently available, they are infrequently used by HCWs for various reasons. The implementation of an SED in an institution requires proof of safety and efficacy as well as education and training of HCWs to encourage the use of the device and reduce the number of NSIs among physicians.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SG had access to and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis and contributed to study conception and design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. AB contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, reviewing and editing of the manuscript and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. CJR and JE contributed to study design, data collection and analysis, review and editing of the manuscript. JP contributed to study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, reviewing, editing and section writing of the manuscript. RN contributed to study design, data collection and data interpretation, reviewing, editing, section writing of the manuscript and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. RH contributed to interpretation of the data, reviewing and editing of the manuscript and critical revision of the article for important intellectual content. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by Drexel College of Medicine IBC Simulation Grant Funding. The funding source had no involvement in the study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; writing of the report; nor the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Drexel University IRB.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Consensus Statement and Call to Action on Sharps Safety released March 2012: International Healthcare Worker Safety Center, 2012. http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/pub/epinet/ConsensusStatementOnSharpsInjuryPrevention.pdf (accessed 29 Mar 2013).

- 2.Makary MA, Al-Attar A, Holzmueller CG, et al. Needlestick injuries among surgeons in training. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2693–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elliott SKF, Keeton A, Holt A. Medical students’ knowledge of sharps injuries. J Hosp Infect 2005;60:374–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamamoto AJ, Solomon JA, Soulen MC, et al. Sutureless securement device reduces complications of peripherally inserted central venous catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2002;13:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trim JC, Elliott TSJ. A review of sharps injuries and preventative strategies. J Hosp Infect 2003;53:237–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). Summary of the Request for Information on Occupational Exposure to Bloodborne Pathogens. Quick Reference Guide to the Bloodborne Pathogen Standard. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor 2011; http://www.osha.gov/SLTC/bloodbornepathogens/bloodborne_quickref.html (accessed 23 Mar 2013)

- 7.2007. EPINet. http://healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/epinet/EPINet-2007-rates.pdf (accessed 29 Mar 2013).

- 8.Wicker S, Jung J, Allwinn R, et al. Prevalence and prevention of needlestick injuries among health care workers in a German university hospital. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2008;81:347–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naghavi SHR, Sanati KA. Accidental blood and body fluid exposure among doctors. Occup Med 2009;59:101–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dement JM, Epling C, Østbye T, et al. Blood and body fluid exposure risks among health care workers: results from the Duke Health and Safety Surveillance System. Am J Ind Med 2004;46:637–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elder A, Paterson C. Sharps injuries in UK health care: a review of injury rates, viral transmission and potential efficacy of safety devices. Occup Med 2006;56:566–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sharps Injuries Among Medical Trainees. In: Occupational Health Surveillance Program MDoPH, editor. Boston, 2011. http://www.mass.gov/eohhs/docs/dph/occupational-health/injuries/injuries-medical-trainees-02-09.pdf (accessed 23 Mar 2013)

- 13.Jagger J, Perry J, Gomaa A, et al. The impact of U.S. policies to protect healthcare workers from bloodborne pathogens: the critical role of safety-engineered devices . J Infect Public Health 2008;1:62–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vason BJ. The safety needle switchover, part 1 of 2. Nurs Manag 2002;33:33–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pegues DAMD. Building better programs to prevent transmission of blood-borne pathogens to healthcare personnel: progress in the workplace, but still no end in sight. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003;24:719–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sohn SMPH, Eagan JRN, Sepkowitz KAMD, et al. Effect of implementing safety-engineered devices on percutaneous injury epidemiology. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2004;25:536–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guglielmi CL, Spratt DG, Berguer R, et al. A call to arms to prevent sharps injuries in our ORs. AORN J 2010;92:387–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall J. Worker safety: a road well-traveled, yet so far to go. Healthc Purchasing News 2003;27:46–46 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Association of Operating Room Nurses (AORN) Seeking solutions to increase sharps safety. AORN J 2011;94:C1–C1,C8,C9 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagstrom AM. Perceived Barriers to Implementation of a Successful Sharps Safety Program. AORN J 2006;83:391–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.