Abstract

A large number of rare genetic variants have been discovered with the development in sequencing technology and the lowering of sequencing costs. Rare variant analysis may help identify novel genes associated with diseases and quantitative traits, adding to our knowledge of explaining heritability of these phenotypes. Many statistical methods for rare variant analysis have been developed in recent years, but some of them require the strong assumption that all rare variants in the analysis share the same direction of effect, and others requiring permutation to calculate the p-values are computer intensive. Among these methods, the sequence kernel association test (SKAT) is a powerful method under many different scenarios. It does not require any assumption on the directionality of effects, and statistical significance is computed analytically. In this paper, we extend SKAT to be applicable to family data. The family-based SKAT (famSKAT) has a different test statistic and null distribution compared to SKAT, but is equivalent to SKAT when there is no familial correlation. Our simulation studies show that SKAT has inflated type I error if familial correlation is inappropriately ignored, but has appropriate type I error if applied to a single individual per family to obtain an unrelated subset. In the contrast, famSKAT has the correct type I error when analyzing correlated observations, and it has higher power than competing methods in many different scenarios. We illustrate our approach to analyze the association of rare genetic variants using glycemic traits from the Framingham Heart Study.

Keywords: rare variant analysis, quantitative traits, family samples, heritability, linear mixed effects model

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, with the advances in whole-genome sequencing technology, assessing the association of rare genetic variants with complex diseases and quantitative traits has become of great interest. Rare genetic variants may account for some of the missing heritability unexplained by genetic loci identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [Eichler et al., 2010], as single variant tests used in GWAS are underpowered for rare genetic variants [Li and Leal, 2008]. To increase power, burden tests have been proposed [Li and Leal, 2008; Morgenthaler and Thilly, 2007; Madsen and Browning, 2009; Morris and Zeggini, 2010]; these tests are based on collapsing rare genetic variants in a predefined genomic region with either a rare variant indicator or a weighted score. These methods implicitly assume that all rare genetic variants in the region have the same direction of effect and even the same effect size, which may not be true. Alternatively, the data-adaptive sum test [Han and Pan, 2010] and step-up approach [Hoffmann, Marini and Witte, 2010] do not require such an assumption and use the signs from single marker test to determine the direction of effects, but both of these approaches require permutation to evaluate statistical significance.

The sequence kernel association test (SKAT) [Wu et al., 2011] proposed recently is a flexible and computationally efficient regression-based approach for rare genetic variants analysis. No assumptions about the directions of effect or the effect sizes of rare genetic variants in the region are required for SKAT. Instead of requiring permutation for the p-value computation, Davies’ method [Davies, 1980] is used to compute the p-values analytically for SKAT. SKAT has been shown to be much more powerful than traditional burden tests in many different scenarios. SKAT can be used in the association analysis of both dichotomous and continuous phenotypes.

Family-based study designs have been widely used in linkage analysis of diseases and quantitative traits [Falk and Rubinstein, 1987; Ott, 1989; Terwilliger and Ott, 1992; Spielman, McGinnis and Ewens, 1993]. In GWAS, ordinary regression approaches are not applicable to family data, because inflated type I error is observed when familial correlation is not appropriately modeled. For quantitative traits, instead of ordinary linear regressions, linear mixed effects models that take familial correlation as a random effect with covariance proportional to the kinship matrix is commonly used for single marker tests in GWAS [Almasy and Blangero, 1998; Rabinowitz and Laird, 2000]. However, burden tests and other methods for joint analysis of rare genetic variants in family samples have not been well established.

In this paper, we use the framework of linear mixed effects models to extend SKAT for rare genetic variants association analysis with quantitative traits in family data. The family-based SKAT (famSKAT) has a different form of test statistic and distribution under the null hypothesis, but has the same rationale as SKAT. When there is no familial correlation, famSKAT is equivalent to SKAT. P-values for famSKAT are also calculated analytically without requiring permutation.

We demonstrate in our simulation studies that SKAT has inflated type I error in family samples when familial correlation is not appropriately considered. By contrast, famSKAT does not suffer from this issue and has correct type I error. We also show that famSKAT is more powerful than applying SKAT to an unrelated subset of the sample. For mixed datasets with both unrelated and related individuals, as the proportion of unrelated individuals decreases, the difference in power between SKAT and famSKAT increases, with famSKAT being always the more powerful approach of the two. Thus, by using famSKAT there is no need to reduce sample size by selecting an unrelated subset of individuals. Finally, we illustrate our approach by assessing the association between rare genetic variants using two glycemic traits in the Framingham Heart Study.

METHODS

Sequence Kernel Association Test for Quantitative Traits in Family Samples

We first define notation and assumptions before we derive the SKAT statistic that accounts for familial correlation. Assuming a sample size of n, let the n × 1 vector of the quantitative trait y follow a linear mixed effects model

where X is an n × p covariate matrix, β is a p × 1 vector consisting of fixed effects parameters (an intercept and p − 1 coefficients for covariates), G is an n × q genotype matrix for q rare genetic variants of interest, γ is a q × 1 vector for the random effects of rare variants, δ is an n × 1 vector for the random effects of familial correlation, which is added to the SKAT model, and ε is an n × 1 vector for the error. The vector of error ε and the random effects γ and δ are assumed normally distributed and uncorrelated with each other:

where W is the pre-specified diagonal weight matrix for the rare variants of q × q, Φ is twice the kinship matrix of size n × n obtained from family information only, I is the identity matrix of size n × n, and τ, , are corresponding variance component parameters. In this parameter setting, we are interested in testing H0: τ = 0 versus H1: τ > 0, which is equivalent to testing H0: γ = 0 versus H1: γ ≠ 0. This is a variance component score test in the linear mixed effects model, which is a locally most powerful test [Wu et al., 2011; Lin, 1997].

Under these assumptions, the phenotypic variance can be written as

The log likelihood for the linear mixed effects model is

To derive a score test for H0:τ = 0, we first take the derivative with respect to τ to get

If we use the restricted maximum likelihood instead of the maximum likelihood method, we would get a different first term, but the same second term. In both cases, if we replace Σ by its consistent estimator, and treat genotype matrix G as fixed, then the first term in the score function is fixed and independent of phenotype data y. Following the same rationale in the derivation of the SKAT score statistic [Liu, Lin and Ghosh, 2007; Kwee et al., 2008], we take twice the second term to be derived as our test statistic.

Under the null hypothesis τ = 0, we can estimate

by fitting the null linear mixed effects model

The maximum likelihood estimators can be obtained using the function lmekin from R package kinship. We replace β, and (and hence Σ) by their maximum likelihood estimators and take

as the famSKAT test statistic. Under the null hypothesis, the variance of the residuals is

Thus

where λi are the eigenvalues of the matrix . The p-value can be computed analytically by Davies’ method [Davies, 1980] or Kuonen’s saddlepoint method [Kuonen, 1999].

We note that even though the null model, test statistic, residual variance and null distribution of famSKAT have different forms compared to those of SKAT, they are directly connected. Actually, if we add a restriction on the model, famSKAT is equivalent to SKAT. Then

where is estimated from the null linear model

and famSKAT statistic becomes

with distribution under the null hypothesis

where λi are the eigenvalues of the matrix . They are proportional to SKAT statistic and null distribution matrix with the coefficient . We favor this form of null distribution matrix, rather than the form proposed in Wu et al. [2011], because usually the sample size n is larger than the number of genetic variants of interest q, the non-zero eigenvalues of and are the same, but the first matrix is of size q × q, while the second matrix is of size n × n; and taking the square root of the diagonal matrix W is computationally much easier than taking the square root of P0.

We note that famSKAT can also be used when we want to provide a known heritability coefficient h2 externally, rather than estimating it from the data. By the reparametrization

when h2 is known, we can use the generalized least square method to estimate only σ2 under the null model. Then we can follow the rest of the famSKAT procedure to perform the test.

Simulations

Type I Error Simulations

To evaluate the type I error, we performed several simulation studies under the null hypothesis of no genetic association. We compared four approaches: famSKAT, burden test accounting for familial correlation (famBT), SKAT which only takes the unrelated subset of the sample (unrSKAT) and SKAT. We used Kuonen’s saddlepoint method [Kuonen, 1999] to compute the p-values for famSKAT, unrSKAT and SKAT. For famBT, we fit the linear mixed effects model

where wj is the jth element on the diagonal of the pre-specified weight matrix W, Gj is the jth column of the genotype matrix G, the scalar γ is the fixed effect for the weighted genetic score, and y, X, β, δ, ε are defined in the same parameter setting as in famSKAT. The genotype effect in this model can be tested as fixed effect test H0: γ = 0 versus H1: γ ≠ 0.

We set the heritability of the trait

For each parameter setting, we simulated 100 genotype datasets with a total sample size of 1000 and 20 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) with minor allele frequency (MAF) in the founders randomly sampled from a uniform distribution of 0.005 to 0.05, and with low (r = 0.1), moderate (r = 0.5), or high (r = 0.7) linkage disequilibrium (LD) between adjacent SNPs in the founders. The LD correlation between farther SNPs decays as an autoregressive model with order 1. We simulated haplotypes for unrelated founders with desired MAF and LD structure using the same procedure as HapSim [Montana, 2005], then we passed down the haplotypes to the next generation to simulate sib pairs, and took the remaining founders as unrelated individuals. Thus we created genotype datasets mixed with unrelated individuals and sib pairs, and let the proportion of unrelated individuals decrease from 75% to 50%, 25%, 0%. For each genotype dataset, 10,000 phenotype datasets including covariates were simulated by using the model

where age is a vector of continuous covariate generated from a normal distribution with mean 50 and standard deviation 5, sex is a vector of dichotomous covariate generated from a Bernoulli distribution with probability 0.5, ε follows a multivariate normal distribution with means 0 and covariance matrix Σ, where

We calculated the p-values of famSKAT, famBT, unrSKAT and SKAT by using the Wu weights [Wu et al., 2011], corresponding to the square of a beta density function of the observed MAF in the founders with parameters 1 and 25. We computed the empirical type I error at α levels of 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001 by counting the proportion of p-values less than or equal to the corresponding α level in the 1 million genotype-phenotype datasets.

Power Simulations

To evaluate the power of famSKAT, famBT and unrSKAT, we set the heritability of phenotype h2 = 0.5 and LD between adjacent SNPs in the founders r = 0.5, and performed simulations under different scenarios. For each parameter setting, we simulated 100 genotype datasets with a total sample size 1000 and 20 SNPs with MAF in the founders randomly sampled from a uniform distribution of 0.005 to 0.05. Similar to the null simulation setting, we simulated genotype datasets mixed with unrelated individuals and sib pairs, and changed the proportion of unrelated individuals from 75% to 50%, 25%, 0%. For each genotype dataset G, 10,000 phenotype datasets including covariates were simulated by using the model

where age, sex and ε are generated in the same way as in the type I error simulations, γ is a vector consisting of the effect sizes of the causal SNPs. We varied the proportion of causal SNPs from 20% to 50% and 80%, and we simulated both same and opposite directions of effects. Causal SNPs were randomly selected out of the 20 SNPs for each phenotype replicate, and in each parameter setting the effect sizes of causal SNPs were determined by

where MAFi is the MAF used to generate the genotype dataset for causal SNP i, and c is a constant for all causal SNPs in each phenotype replicate, calculated as

where R2, the total proportion of variance explained by all causal SNPs, was fixed at 1% for scenarios when all causal SNPs had effects in the same direction, and 5% for scenarios when 50% of the causal SNPs had positive effects and 50% had negative effects. D is the LD correlation matrix for the 20 SNPs, and ν is a vector indicating the directions of causal SNP effects in each replicate. We used the same weights for famSKAT, unrSKAT and famBT, which were the Wu weights calculated from the observed MAF in founders. The empirical power was evaluated at the α level of 0.001.

RESULTS

Type I Error Simulations

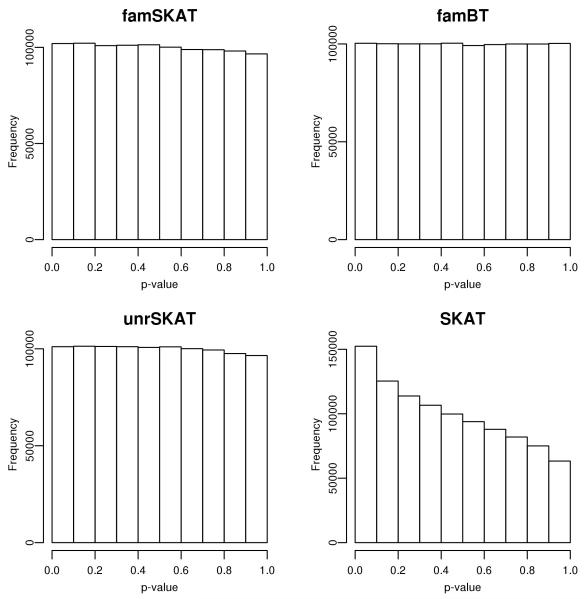

Table 1 shows the empirical type I errors of famSKAT, famBT, unrSKAT and SKAT at different α levels in 3 LD scenarios and 4 scenarios for the proportion of unrelated individuals. The results suggest that when SKAT is directly applied to the full sample with correlated individuals, it has inflated type I error at all α levels. The empirical type I error tends to be higher when LD decays. In the contrast, famSKAT, famBT and unrSKAT retain the correct type I errors. Thus, in subsequent power simulations we only investigated these three approaches. The distributions of the p-values from the four approaches for the scenario of LD between adjacent SNPs r = 0.5 and proportion of unrelated individuals 0% were shown in Figure 1. We found that famSKAT, famBT and unrSKAT all had uniform distribution of the p-values, while the distribution of the pvalues from SKAT was more likely to be small, explaining the inflated type I error.

Table 1. Type I Errors of famSKAT and SKAT.

| α = 0.01 | α = 0.001 | α = 0.0001 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | Unrelated% | famSKAT | famBT | unrSKAT | SKAT | famSKAT | famBT | unrSKAT | SKAT | famSKAT | famBT | unrSKAT | SKAT |

| r = 0.1 | 0% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.027 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0008 | 0.0038 | 0.00009 | 0.00009 | 0.00008 | 0.00052 |

| 25% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.0009 | 0.0011 | 0.0008 | 0.0028 | 0.00009 | 0.00012 | 0.00008 | 0.00036 | |

| 50% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.017 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0020 | 0.00009 | 0.00009 | 0.00008 | 0.00024 | |

| 75% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 0.0009 | 0.0011 | 0.0009 | 0.0013 | 0.00009 | 0.00012 | 0.00009 | 0.00016 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| r = 0.5 | 0% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.020 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0024 | 0.00008 | 0.00008 | 0.00009 | 0.00029 |

| 25% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.017 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0020 | 0.00010 | 0.00011 | 0.00008 | 0.00025 | |

| 50% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.014 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0016 | 0.00009 | 0.00011 | 0.00009 | 0.00018 | |

| 75% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0012 | 0.00009 | 0.00011 | 0.00009 | 0.00013 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| r = 0.7 | 0% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.017 | 0.0009 | 0.0011 | 0.0009 | 0.0020 | 0.00010 | 0.00011 | 0.00009 | 0.00025 |

| 25% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.015 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0017 | 0.00010 | 0.00011 | 0.00007 | 0.00019 | |

| 50% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.013 | 0.0009 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0014 | 0.00009 | 0.00009 | 0.00010 | 0.00015 | |

| 75% | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.0010 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0012 | 0.00011 | 0.00011 | 0.00009 | 0.00013 | |

Empirical type I errors were calculated as the proportion of p-values less than or equal to the corresponding α level in 1 million genotype-phenotype datasets. LD between adjacent SNPs changes from r = 0.1, 0.5 to 0.7, and the proportion of unrelated individuals changes from 0%, 25%, 50% to 75%.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the p-values for famSKAT, famBT, unrSKAT and SKAT from the null simulation with LD between adjacent SNPs 0.5 and proportion of unrelated individuals 0%.

Power Simulations

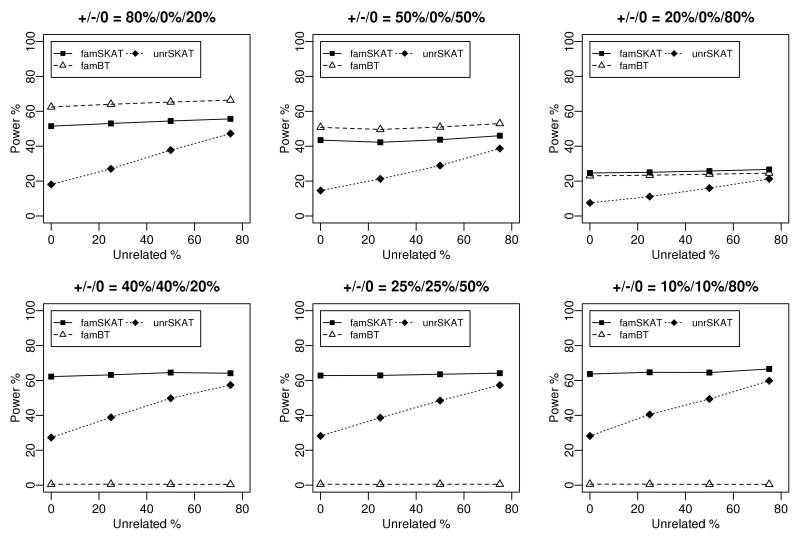

Power simulation results of famSKAT, famBT and unrSKAT are shown in Figure 2. In all scenarios, 20 SNPs were analyzed. We simulated scenarios in which the proportion of causal SNPs was 20%, 50% or 80%, with effects in the same or opposite directions. As the proportion of unrelated individuals decreases from 75% to 50%, 25% and 0%, the sample size for unrSKAT also decreases from 875 to 750, 625 and 500. As a result, the power of unrSKAT also drops. In contrast, the power of famSKAT and famBT remains almost constant, regardless of the proportion of unrelated individuals. FamBT has higher power than famSKAT when the proportion of causal SNPs is greater than or equal to 50% and all causal SNPs have the same direction of effects, but it has almost no power in scenarios when causal SNPs have opposite directions of effects. Generally, famSKAT performs well in all these scenarios, suggesting that famSKAT is an omnibus method which does not have compromised power for different mixtures of related and unrelated individuals.

Figure 2.

Power comparisons of famSKAT, famBT and unrSKAT. Empirical power calculated at level of 0.001. The sample consists of sib pairs and unrelated individuals. The total sample size in each scenario is 1000, and the total number of SNPs analyzed is 20. In each panel, +/−/0 indicates the proportion of SNPs with positive effects, negative effects and no effects.

Analysis of Framingham Heart Study Data

We used genotype data from Framingham SNP Health Association Resource (SHARe) and phenotype data from the Framingham Heart Study to analyze the association with two glycemic traits: fasting glucose and log-transformed fasting insulin. We restricted our analyses to SNPs with MAF less than 5% within 100kb of 16 gene regions selected for the prior association with fasting glucose, and 2 genes reported to be associated with log-transformed fasting insulin [Dupuis et al., 2010]. We adjusted the fasting glucose analysis for age and sex, and logtransformed insulin was additionally adjusted for body mass index. We performed famSKAT and famBT for all individuals with both genotype and phenotype available, and performed SKAT for only a subset of unrelated individuals. For comparison purpose, we calculated the MAF using a subset of unrelated individuals and applied Wu weights to all three methods.

We investigated the association between fasting glucose and rare genetic variants in 16 gene regions previously shown to be associated in large scale GWAS [Dupuis et al., 2010]: ADCY5, ADRA2A, C2CD4B, CRY2, DGKB-AGMO, FADS1, G6PC2, GCK, GCKR, GLIS3, MADD, MTNR1B, PROX1, SLC2A2, SLC30A8, and TCF7L2. The results are shown in Table 2. After adjusting for multiple testing using a Bonferroni correction, we detected no association between fasting glucose and rare genetic variants in the selected gene regions at the family-wise α level of 0.05, for all three methods. CRY2 reaches the nominal significance level with a p-value of 0.0381 using famSKAT and 0.0085 using famBT, and G6PC2 reaches the nominal significance level with a p-value of 0.0418 using famSKAT, but none of these gene regions reaches nominal statistical significance when evaluated using unrSKAT.

Table 2. Analysis of Framingham Heart Study Data.

| famSKAT | famBT | unrSKAT | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Chr | Start | Stop | Sample Size |

N SNPs |

p- value |

Sample Size |

N SNPs |

p- value |

Sample Size |

N SNPs |

p- value |

| Trait: fasting glucose | ||||||||||||

| ADCY5 | 3 | 124486089 | 124650082 | 6479 | 18 | 0.9125 | 6479 | 18 | 0.5842 | 1924 | 17 | 0.9698 |

| ADRA2A | 10 | 112826911 | 112830560 | 6479 | 5 | 0.9557 | 6479 | 5 | 0.9453 | 1924 | 5 | 0.7293 |

| C2CD4B | 15 | 60243029 | 60244774 | 6479 | 3 | 0.9576 | 6479 | 3 | 0.8209 | 1924 | 3 | 0.7104 |

| CRY2 | 11 | 45825533 | 45861375 | 6479 | 8 | 0.0381 | 6479 | 8 | 0.0085 | 1924 | 7 | 0.7299 |

| DGKB-AGMO | 7 | 14153770 | 15568165 | 6479 | 76 | 0.6579 | 6479 | 76 | 0.3648 | 1924 | 72 | 0.1992 |

| FADS1 | 11 | 61323677 | 61340886 | 6479 | 5 | 0.5245 | 6479 | 5 | 0.3723 | 1924 | 5 | 0.7049 |

| G6PC2 | 2 | 169465996 | 169474756 | 6479 | 24 | 0.0418 | 6479 | 24 | 0.1173 | 1924 | 22 | 0.1373 |

| GCK | 7 | 44150395 | 44165412 | 6479 | 4 | 0.6283 | 6479 | 4 | 0.5864 | 1924 | 4 | 0.2486 |

| GCKR | 2 | 27573210 | 27600054 | 6479 | 7 | 0.2603 | 6479 | 7 | 0.2461 | 1924 | 6 | 0.0930 |

| GLIS3 | 9 | 3814128 | 4290035 | 6479 | 57 | 0.9170 | 6479 | 57 | 0.3920 | 1924 | 56 | 0.9822 |

| MADD | 11 | 47247775 | 47308158 | 6479 | 7 | 0.6571 | 6479 | 7 | 0.5145 | 1924 | 7 | 0.6316 |

| MTNR1B | 11 | 92342437 | 92355596 | 6479 | 11 | 0.8384 | 6479 | 11 | 0.7243 | 1924 | 11 | 0.0833 |

| PROX1 | 1 | 212228483 | 212276385 | 6479 | 34 | 0.2414 | 6479 | 34 | 0.3976 | 1924 | 33 | 0.1082 |

| SLC2A2 | 3 | 172196831 | 172227462 | 6479 | 5 | 0.8383 | 6479 | 5 | 0.7365 | 1924 | 5 | 0.6836 |

| SLC30A8 | 8 | 118216518 | 118258134 | 6479 | 12 | 0.1766 | 6479 | 12 | 0.0970 | 1924 | 12 | 0.7869 |

| TCF7L2 | 10 | 114699999 | 114916060 | 6479 | 7 | 0.1035 | 6479 | 7 | 0.4249 | 1924 | 7 | 0.2147 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Trait: log-transformed fasting insulin | ||||||||||||

| GCKR | 2 | 27573210 | 27600054 | 6031 | 7 | 0.4878 | 6031 | 7 | 0.1586 | 1840 | 6 | 0.1016 |

| IGF1 | 12 | 101335584 | 101398508 | 6031 | 16 | 0.0232 | 6031 | 16 | 0.0234 | 1840 | 16 | 0.1258 |

Association analysis with fasting glucose and log-transformed fasting insulin from the Framingham Heart Study and genotype data from the Framingham SNP Health Association Resource, using famSKAT, famBT and unrSKAT. Fasting glucose was adjusted for age and sex, and log-transformed fasting insulin was adjusted for age, sex and body mass index. SNPs with MAF less than 5% within 100kb of each gene region were included in the analysis. Gene and SNP locations were reported on NCBI build 36. All individuals with available genotypes and phenotype were analyzed with famSKAT and famBT, while unrSKAT analyses only included a subset of unrelated participants. Wu weights with beta (1, 25) based on the MAF in a subset of unrelated individuals were used for all three methods.

We also investigated the association between log-transformed fasting insulin and rare genetic variants in 2 gene regions previously shown to be associated in large scale GWAS [Dupuis et al., 2010]: GCKR and IGF1. After adjusting for multiple testing using a Bonferroni correction, IGF1 shows association with log transformed fasting insulin with a nominal p-value of 0.0232 using famSKAT and 0.0234 using famBT. Neither gene reaches even the nominal significance level using SKAT.

Table 2 also shows that the sample size for unrSKAT is much smaller than that for famSKAT and famBT, because even though the Framingham Heart Study is not a family-based cohort, there are many families in the study. Thus, by selecting unrelated individuals we greatly reduced the sample size. Because some SNPs with rare minor alleles may not be polymorphic in the subset of unrelated individuals, for some gene regions the number of SNPs for unrSKAT is smaller than the number of SNPs for famSKAT and famBT.

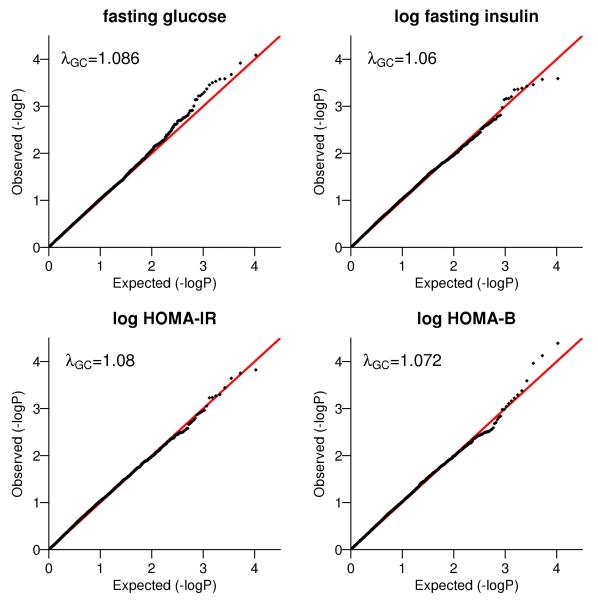

We also performed a genome-wide sliding window analysis on these two traits, as well as logtransformed HOMA-IR and HOMA-B, using SHARe genotype data. We only included SNPs with MAF less than 5% and ran the analysis using a sliding window of 500kb, with 250kb overlap each with previous and subsequent windows. We removed windows with 0 or 1 SNP, resulting in 10,546 windows for all autosomes with the number of SNPs ranging from 2 to 76 with median 18. No window reached the genome-wide significance using famSKAT, famBT or unrSKAT. The Q-Q plots for famSKAT are shown in Figure 3. There is minimal inflation of the p-values from this genome-wide analysis.

Figure 3.

Q-Q plots for famSKAT in the genome-wide sliding window analysis on four glycemic traits. The p-values were plotted as minus log base 10 p-values. The genomic control factor λGC was computed as the ratio of median chi-square statistics with 1 df corresponding to observed and expected p-values.

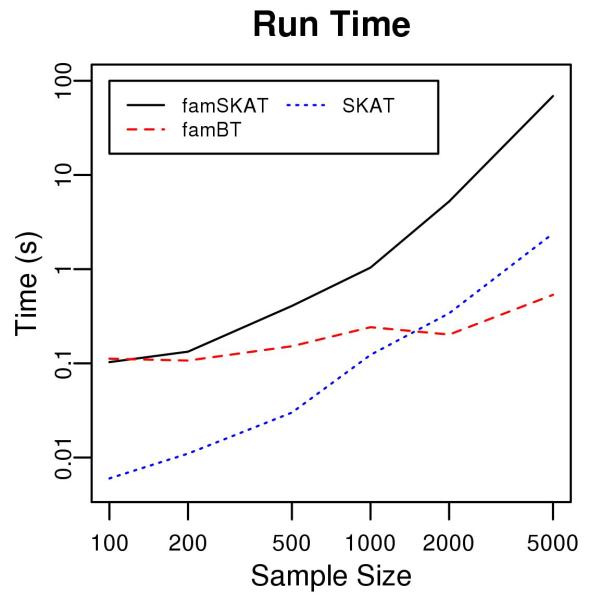

Computation Time

The computation time of famSKAT depends on both the sample size and the number of SNPs. The empirical run time of famSKAT, famBT and SKAT in analyzing sib pairs with indicated total sample sizes on a single computing node with 2.33 GHz CPU and 4 GB memory is shown in Figure 4. With a small sample size, the limiting step in famSKAT is fitting the null linear mixed effects model, so the computation time is comparable to that of famBT, which also requires fitting a linear mixed effects model. As the sample size increases, all three methods require more computation time, and the time of famSKAT and SKAT increases dramatically. Both famSKAT and SKAT require matrix calculation, and the limiting step in famSKAT becomes inverting the matrix , which takes about 90% of the computation time when the sample size is 5000. The genome-wide sliding window analysis of SHARe genotype data using a sliding window of 500kb takes about 5 hours for chromosome 1 on a single computing node with 2.33 GHz CPU and 4 GB memory.

Figure 4.

Run time of famSKAT, famBT and SKAT in analyzing 20 SNPs.

DISCUSSION

In this paper, we propose famSKAT as an extension of SKAT which can be applied to data with familial correlation. We demonstrate that famSKAT is a general and flexible variance component score test approach, which is equivalent to SKAT when the familial variance component is set to 0. It can be applied to quantitative traits with unknown or known heritability.

Compared with famBT, famSKAT is advantageous in power when the proportion of causal SNPs in a genomic region is small, and when not all causal SNPs have the same direction of effects. As expected, famBT outperforms famSKAT when the proportion of causal SNPs is greater than or equal to 50% and all these SNPs have positive effects, but the performance of famSKAT in these scenarios is still satisfactory. In real data analysis, when we do not have sufficient a priori information about the proportion of causal SNPs or the directions of effects, famSKAT would be a better choice over famBT.

We show that when SKAT is inappropriately applied to correlated data, it has inflated type I error. Thus, the best we can do for SKAT is to select unrelated individuals from the whole sample. However, our power simulations demonstrate that this strategy is not in favor of power in many scenarios. In the contrast, we do not need to reduce our sample size if we use famSKAT. Our real data example from the Framingham Heart Study also shows that SKAT does not even have an observation which reaches the nominal significance level of 0.05.

Common genetic variants at 16 gene regions we chose for fasting glucose and 2 gene regions we chose for log-transformed fasting insulin have been shown to be associated with either trait in large GWAS [Dupuis et al., 2010]. However, we do not have solid evidence to show that there is strong association between either trait and the rare genetic variants in these regions. We noticed that the sample size in this analysis was far smaller than in Dupuis et al. [2010], which reduced the power. In addition, the SHARe project was not specifically designed for rare variants analysis, so most SNPs in our genotype dataset are common SNPs which were excluded from the analysis. With the progress of sequencing studies, we should be able to identify much more rare variants and perform the candidate gene or even genome-wide analysis again using the new genotype dataset with dense rare genetic variants. On the other hand, some gene regions may be truly associated with the trait only through common SNPs, so we do not expect to identify the association with rare genetic variants for all these gene regions we selected.

With the development in sequencing technology and the lowering of the cost, sequencing data which contain a lot of rare genetic variants have become available, not only for case-control studies, but also for cohorts that include family members. Based on SKAT, one of the most powerful rare genetic variants analysis methods to date, we developed famSKAT in the hope of facilitating rare genetic variants analysis to identify novel genes associated with quantitative traits. With famSKAT, cohorts with family data can perform the association analysis with rare genetic variants, using as much data as possible, without having to select unrelated individuals from the pedigree. FamSKAT has been implemented in R, and source code is available at http://www.bumc.bu.edu/linga/research/publications/famskat/.

For calculating the p-values, we recommend using Kuonen’s saddlepoint method [Kuonen, 1999] instead of Davies’ method [Davies, 1980]. As a method based on numerical integration, Davies’ method requires specifying the accuracy. When the p-value is expected to be very small, Davies’ method cannot calculate it accurately. Table 3 shows this numerical issue in a power simulation context. Davies’ method suffers from negative and zero p-values (and possibly significant roundoff error) regardless of the accuracy specified. In the contrast, Kuonen’s method does not have such issues. Thus, if we perform a genome-wide rare variants analysis using sequence data, from which we expect extreme low p-values, Kuonen’s method might be a better choice over Davies’ method.

Table 3. Comparison of Kuonen’s and Davies’ methods in calculating p-values in the tail.

| Method | Accuracy | Minimum p-value | Median p-value | Maximum p-value | % p-value < 0 | % p-value = 0 | % round-off error$ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuonen | NA | 1.2×10−23 | 2.1×10−9 | 0.021 | 0% | 0% | 0% |

|

| |||||||

| Davies | 10−4 | −1.2×10−6 | 0 | 0.022 | 0.87% | 83.31% | 0% |

| 10−5 | −5.6×10−7 | 0 | 0.022 | 6.04% | 71.37% | 0% | |

| 10−6 | −3.1×10−8 | 0 | 0.022 | 12.14% | 54.32% | 0% | |

| 10−7 | −4.4×10−9 | 0 | 0.022 | 16.38% | 38.19% | 0% | |

| 10−8 | −2.4×10−9 | 0 | 0.022 | 27.65% | 23.15% | 0% | |

| 10−9 | −2.0×10−10 | 1.8×10−9 | 0.022 | 21.41% | 14.86% | 0% | |

| 10−10 | −3.3×10−11 | 1.9×10−9 | 0.022 | 17.89% | 9.23% | 0% | |

| 10−11 | −5.7×10−13 | 1.9×10−9 | 0.022 | 7.64% | 5.38% | 0% | |

| 10−12 | −9.7×10−14 | 1.9×10−9 | 0.022 | 5.93% | 2.93% | 0% | |

| 10−13 | −2.4×10−14 | 1.9×10−9 | 0.022 | 4.79% | 1.53% | 0% | |

| 10−14 | −4.4×10−16 | 1.9×10−9 | 0.022 | 0.01% | 0.89% | 20.34% | |

| 10−15 | −2.9×10−15 | 1.9×10−9 | 0.022 | 1.40% | 0.58% | 99.67% | |

Proportion of significant round-off error in the calculation, returned by the function davies from R package CompQuadForm. Using our power simulation framework, we simulated a scenario in which the heritability of phenotype h2 = 0.5, LD between adjacent SNPs in the founders r = 0.5. We simulated 500 sib pairs and 20 SNPs with MAF in the founders randomly sampled from a uniform distribution of 0.005 to 0.05. Of these 20 SNPs, 16 were neutral and 4 were positively associated with the trait, explaining 5% of the phenotypic variance in total. We analyzed 10000 replicates using famSKAT with Kuonen’s method, and Davies’ method with accuracy from 10−4 to 10−15.

Even though famSKAT was developed for analyzing rare genetic variants, it can also be used for common variant analysis, combined common and rare variant analysis or conditional association analyses. Depending on the research hypothesis, common variants can be treated as fixed effects in the model, or random effects along with the rare genetic variants. During the review of this paper, we became aware that Schifano et al. [2012] had recently developed a SNP set association analysis approach for common variants analysis in family data, which is essentially equivalent to our method. The use of famSKAT combined with the collapsing of some very rare genetic variants such as singletons is also possible. Similar with SKAT, external weights based on annotation information or functional prediction can be incorporated to further boost the power.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Thomas Lumley for his insights in Kuonen’s saddlepoint method. This research was partially supported by NIH awards R01 DK078616, U01 DK85526 and K24 DK080140. A portion of this research was conducted using the Linux Clusters for Genetic Analysis (LinGA) computing resources at Boston University Medicine Campus. The Framingham Heart Study is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with Boston University (Contract No. N01-HC-25195). This work was partially supported by a contract with Affymetrix, Inc for genotyping services (Contract No. N02-HL-6-4278).

REFERENCES

- Almasy L, Blangero J. Multipoint quantitative-trait linkage analysis in general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62:1198–1211. doi: 10.1086/301844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies RB. The distribution of a linear combination of chi-square random variables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics) 1980;29:323–333. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2010;42:105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichler EE, Flint J, Gibson G, et al. Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nrg2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk CT, Rubinstein P. Haplotype relative risks: an easy reliable way to construct a proper control sample for risk calculations. Ann Hum Genet. 1987;51:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1987.tb00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han F, Pan W. A data-adaptive sum test for disease association with multiple common or rare variants. Hum Hered. 2010;70:42–54. doi: 10.1159/000288704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann TJ, Marini NJ, Witte JS. Comprehensive approach to analyzing rare genetic variants. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuonen D. Saddlepoint approximations for distributions of quadratic forms in normal variables. Biometrika. 1999;86:929–935. [Google Scholar]

- Kwee LC, Liu D, Lin X, Ghosh D, Epstein MP. A powerful and flexible multilocus association test for quantitative traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Leal SM. Methods for detecting associations with rare variants for common diseases: application to analysis of sequence data. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X. Variance component testing in generalised linear models with random effects. Biometrika. 1997;84:309–326. [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Lin X, Ghosh D. Semiparametric regression of multidimensional genetic pathway data: least-squares kernel machines and linear mixed models. Biometrics. 2007;63:1079–1088. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen BE, Browning SR. A groupwise association test for rare mutations using a weighted sum statistic. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montana G. HapSim: a simulation tool for generating haplotype data with pre-specified allele frequencies and LD coefficients. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4309–4311. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenthaler S, Thilly WG. A strategy to discover genes that carry multi-allelic or mono-allelic risk for common diseases: a cohort allelic sums test (CAST) Mutat Res. 2007;615:28–56. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AP, Zeggini E. An evaluation of statistical approaches to rare variant analysis in genetic association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:188–193. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott J. Statistical properties of the haplotype relative risk. Genet Epidemiol. 1989;6:127–130. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370060124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowitz D, Laird N. A unified approach to adjusting association tests for population admixture with arbitrary pedigree structure and arbitrary missing marker information. Hum Hered. 2000;50:211–223. doi: 10.1159/000022918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano ED, Epstein MP, Bielak LF, Jhun MA, Kardia SLR, Peyser PA, Lin X. SNP set association analysis for familial data. Genet Epidemiol. 2012;36:797–810. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielman RS, McGinnis RE, Ewens WJ. Transmission test for linkage disequilibrium: the insulin gene region and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:506–516. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger JD, Ott J. A haplotype-based ‘haplotype relative risk’ approach to detecting allelic associations. Hum Hered. 1992;42:337–346. doi: 10.1159/000154096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, Lin X. Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89:82–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]