Abstract

Women are seeking care for pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in increasing numbers and a significant proportion of them will undergo a second repair for recurrence. This has initiated interest by both surgeons and industry to utilize and design prosthetic mesh materials to help augment longevity of prolapse repairs. Unfortunately, the introduction of transvaginal synthetic mesh kits for use in women was done without the benefit of Level 1 data to determine its utility compared to native tissue repair. This report summarizes the potential benefit/risks of transvaginal synthetic mesh use for POP and recommendations regarding its continued use.

Introduction/Background

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP), defined as the protrusion of the vagina and pelvic organs into or beyond the vaginal introitus, can affect the anterior, posterior, and apical compartments of the vagina or a combination thereof leading to a marked impact on quality of life. National population-based estimates using validated measures, reported an overall 2.9 percent prevalence of symptomatic POP. (1) However, other population based surveys have revealed prevalence estimates as high as 8 percent. (2, 3)

In the United States, an estimated 300,000 surgical procedures are performed annually for prolapse. (4) A woman’s lifetime risk for undergoing a surgical intervention for symptomatic pelvic floor disorders is approximately 11 to 19 percent. (5) A large percentage of the women, 6 to 29 percent, will require additional surgery for recurrent POP or urinary incontinence, and those who have undergone at least 2 prior prolapse procedures have reoperation rates over 50 percent. (6,7,8) Efforts to combat these high failure rates and to improve patient outcomes has led to the development and introduction of materials, including synthetic mesh, to augment gynecologic reconstructive surgical repairs. (9) In light of recent developments with the use of synthetic permanent mesh in vaginal reconstructive surgery, we will restrict the discussion to this material.

Food and Drug Administration Safety Communication

Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) cleared the first surgical mesh product specifically designed for the surgical treatment of POP in 2001, surgical mesh in absorbable and permanent forms had been employed in vaginal approaches to pelvic floor disorders for several years. Biologic grafts and synthetic mesh prostheses have been utilized in abdominal repairs for POP since the 1970s. (10) The use of vaginal mesh in gynecologic surgery increased since 2004 with the development of an estimated 100 synthetic mesh devices. However, concomitant to the increased use of vaginal synthetic mesh was an increase in adverse event reporting, specifically medical device reports (MDRs), within the Manufacturer and User Device Experience (MAUDE) database. In October 2008, the FDA issued a Public Health Notification (PHN) to inform physicians and patients of adverse events related to vaginal reconstructive surgical use of synthetic mesh, and to provide recommendations on how to mitigate risks and counsel patients appropriately. (10)

Over the next three years, and for reasons that are not completely delineated, the FDA observed a 5-fold increase in the number of MDRs associated with the use of synthetic vaginal mesh in POP surgery. Thus, in response to these reports and with the impetus to address growing concerns for patient safety, the FDA released a Safety Communication reflecting data from a systematic review of the literature addressing the safety, efficacy, and limitations of existing literature for urogynecologic surgical mesh. Due to media response as well as the depth and complexity of the impact the FDA release had on patient, physician, and manufacturing companies, several national gynecological and urological organizations released response statements to provide further guidance to this issue.

National Organizational Response to FDA Recommendations

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) echoed the FDA’s charge for rigorous comparative effectiveness research as well lending support to the formation of an advisory committee, the Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Panel. ACOG also recommended voluntary physician reporting through the MAUDE database and noted that complications of vaginal reconstructive surgery also occur with non-mesh approaches. (11)

The Society of Gynecologic Surgeons (SGS) reported general agreement with the recommendations made by the FDA and highlighted that discriminant use of synthetic transvaginal mesh to augment vaginal defects should be performed by trained surgeons with experience in complex reconstructive surgery and only on patients with perceived unacceptable risk of clinical failure using other non-mesh approaches. Furthermore, SGS in parallel with the FDA, called for long term clinical trials evaluating benefits and safety of vaginal mesh placement. (12)

The American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) responded in support as well, emphasizing that the FDA Safety Communication conclusions and recommendations should not apply to the use of synthetic mesh for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence or an abdominal approach to the repair of POP. In addition, AUGS focused on the FDA’s recommendations for thorough patient informed consent as well as the imperative that surgeons performing vaginal mesh procedures undergo training specific to each procedure. (13)

The Society for Female Urology and Urodynamics (SUFU) was also broadly supportive of the FDA white paper, and also noted that many of the complications of vaginal mesh surgeries also occur in non-mesh procedures. It was recommended that consideration of mesh placement be conducted on a case by case basis with informed discussion. As with ACOG and AUGS, SUFU also supported a review of the FDA 501k approval process. (14)

Indications for Mesh in Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

Historically, indications for the treatment of POP have focused on patient symptomology. Patients with bothersome symptoms related to POP including, pressure, protrusion, discomfort, as well as those with associated symptoms or impact on urinary, bowel, or sexual function are considered candidates for intervention. (15) Initial marketing of synthetic vaginal mesh was aimed at improved success rates for POP surgery and time-efficient, minimally invasive procedures. Currently, limited level 1 data exists that clearly guides indications to aid in surgical decision making for the use of synthetic transvaginal mesh augmentation in POP surgery.

Authors from the Consensus of the 2nd International Urogynecological Association’s (IUGA) Grafts Roundtable reported that the use of the term “indications” was too strong to employ regarding recommendations reported on the transvaginal mesh use at this time due to the paucity of data in the literature. A summary of potential benefits of synthetic graft use are seen in Table 1, in an adaptation from the terminology used for recommendations from IUGA delineated as “likely to be beneficial”, “possibly beneficial”, “unlikely to be beneficial”, and “not recommended”. (16)

Table 1.

Factors for the Consideration of Use of Vaginal Mesh in POP Surgery

| Variable | Likely Benefit |

Possible Benefit |

Unlikely Benefit |

Not Recommended |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| < 50 years | • | |||

| ≥ 50 years | • | |||

| Recurrent (same site) | • | |||

| Cystocele/Anterior Compartment | ||||

| ≥ Stage 2 | • | |||

| ≤ Stage 2 | • | |||

| Posterior Compartment | • | |||

| Apex (vault, cuff, cervix) | • | |||

| Deficient Fascia | • | |||

| Chronic increase intra-abdominal pressure |

• | |||

| Pain Syndromes (local/systemic) | • | |||

| Possibility of Pregnancy | • | |||

| Combination Factors | ||||

| Recurrent + Cystocele > Stage 2 | • | |||

| Recurrent + Posterior Compartment | • | |||

| Recurrent + Apex/Cuff/Cervix | • | |||

| Recurrent + Increased Abdominal Pressure |

• | |||

| Recurrent + Deficient Fascia | • | |||

| Cystocele > Stage 2 + Increased Intra-abdominal Pressure |

• | |||

| Cystocele > Stage 2 + Deficient Fasica |

• |

Adapted from Davila (16)

Conditions that may be taken into consideration include those in which patients experience repetitive increases in intra-abdominal pressure (chronic bronchitis, chronic constipation or other frequent Valsalva invoking conditions, such as heavy lifting). (17) As noted in the summary table, patients with collagen deficiency disorders, denoted as deficient fascia, may also be candidates that would have a likely benefit from transvaginal synthetic mesh repair.

The authors reported that despite the possible circumstances in which mesh use may be appropriate or provide benefit to a patient with POP, they recommend that the patient be fully counseled regarding outcomes and possible complications (discussed below). Furthermore, as other reviews have demonstrated, there is a timely call for more thorough investigation of surgical mesh use in POP repair, especially studies involving the use of control or native tissue repair arms as well as the inclusion of functional short and longer term outcomes with validated symptom and quality of life measures.

Contraindications of Mesh in Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

The authors are unaware of strong evidence-based guidelines regarding absolute contraindications for the use of vaginal mesh in the surgical treatment of POP. Several studies have demonstrated increased risk of mesh exposure and wound infections with increasing BMI. (18, 19) Also, noted is that tissue healing may be impaired in poorly controlled diabetic patients. Thus placement of a vaginal foreign body may not be indicated. Smoking is associated with decreased vascularity, poor tissue healing, and increased mesh exposure. (20) One series in which patients underwent abdominal sacral colpoperineorrhapy, tobacco users were noted to have a 4-fold risk of developing mesh erosions as compared to non-smokers. (21) These conditions as well as several others to be considered are noted in Table 2. Although not a contraindication, and quite often a concomitant procedure, hysterectomy at the same time as anterior vaginal wall mesh augmentation does pose a significant increased risk for mesh exposure. (22)

Table 2.

Co-morbid Conditions to Consider with Vaginal Mesh Implantation

| Condition | Issues |

|---|---|

| BMI | BMI > 30, associated with inc. mesh exposure |

| Diabetes | Poor wound healing |

| Genital Atrophy | Poor wound healing |

| Chronic Steroid Use | Poor wound healing |

| Smoking/Tobacco Abuse | Poor wound healing |

Adapted from Davila (16)

Vaginal atrophy should also be a consideration when counseling patients for transvaginal mesh repair. The vaginal epithelium should be well estrogenized both pre- and postoperatively with estrogen cream if necessary. (23) An additional consideration that has been noted in the literature is that of hypersensitivity reactions to synthetic transvaginal mesh. A case-controlled study that included the histological and immunohistochemical analysis of vaginal synthetic mesh explantations in a small population of women noted markers of humorally mediated lymphocytic reaction. (24) Though graft-versus-host reactions are not predictable, caution should be exercised in women who have had previous reactions to transvaginal mesh implantation.

Complications of Mesh in Surgical Treatment of Pelvic Organ Prolapse

In the FDA Safety Communication it was noted that mesh-associated complications are not rare. Brill et al, recently summarized POP adverse events as reported from the MAUDE database (Table 3). (10, 25)

Table 3.

POP Adverse Events (MAUDE database), 2005-2010

| Rank | Type of Event | Medical Device Reports |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Erosion | 528 |

| 2 | Pain | 472 |

| 3 | Infection | 253 |

| 4 | Bleeding | 124 |

| 5 | Dyspareunia | 108 |

| 6 | Organ perforation | 88 |

| 7 | Urinary Problems | 80 |

| 8 | Vaginal Scarring/Shrinkage | 43 |

| 9 | Neuromuscular Problems | 38 |

| 10 | Recurrent Prolapse | 32 |

Brill (25)

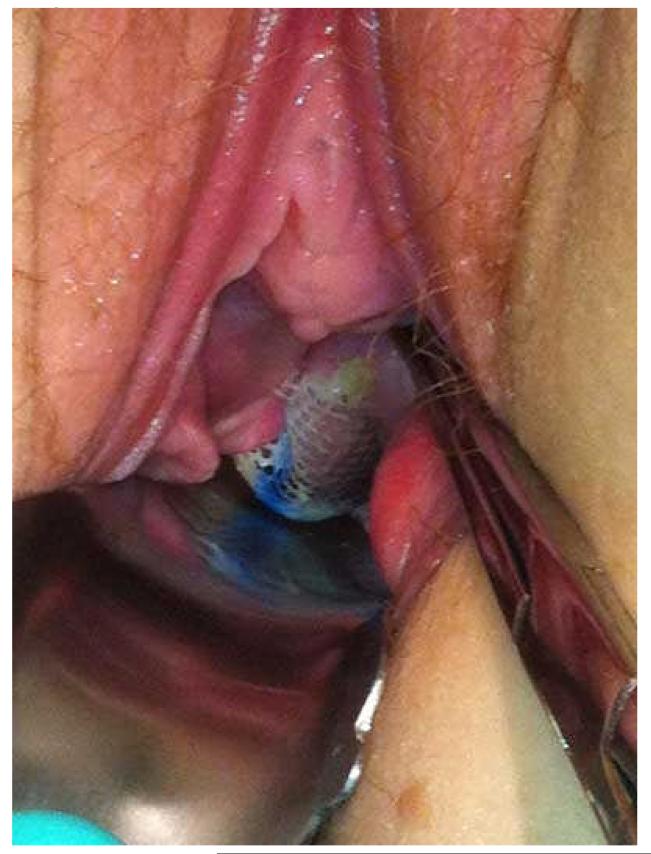

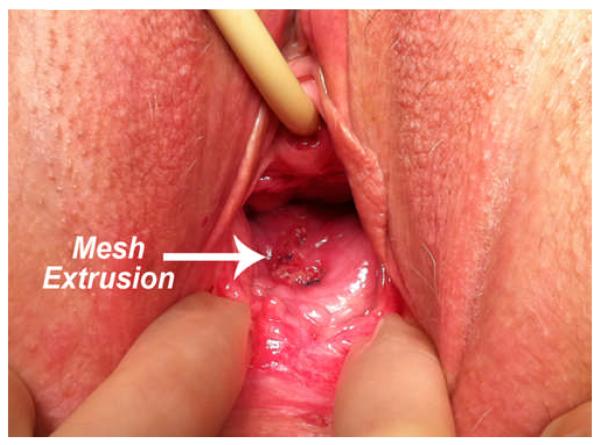

As noted in the recent ACOG Committee Opinion, compared to native tissue repair, synthetic mesh exposure/erosion or extrusion is unique and the most common complication of transvaginal mesh augmentation for POP repair. Often the terms mesh exposure and mesh extrusion are utilized interchangeably. IUGA and the International Continence Society have stated that the generic use of the term “erosion” does not necessarily describe all clinical scenarios and complications of synthetic transvaginal mesh implantation, and therefore have provided a new terminology and classification system for complications involving transvaginal meshes, tapes, and grafts in the female pelvic floor. Within this classification system, an exposure is defined as vaginal mesh visualized through separated epithelium, whereas a mesh extrusion is the gradual passage of mesh out of the body structure or tissue. (26) (Figures 1 and 2, respectively) Rates of mesh exposure and extrusion complications vary in the literature, as does the follow-up rates of the outcome studies from which they are obtained. Many studies report mesh “erosion” rates. Mesh erosions as characterized by the FDA refers to mesh coming through the vagina. The FDA notes that this complication is often called exposure or extrusion. (10) For the purposes of this review, the authors will report the complication rates as they are previously published, whether those complications are reported as erosions or more specifically as mesh exposures or extrusions.

Figure 1.

Mesh Exposure

Figure 2.

Mesh Extrusion

In an update to their original systematic review in 2008, the SGS analyzed 110 studies reporting adverse events associated with vaginal mesh applications in POP surgery and revealed an overall erosion rate of 10.3 percent. (27) Sixteen of the 110 studies reported on wound granulation tissue development and reported an overall rate of 7.8 percent. Rardin and colleagues recently reported transvaginal mesh erosion rates varying from 0 to 25 percent. (28) Exposure rates for level 1 studies range from 5 to 19 percent. (29)

A more recent review of over 1,508 prolapse repair procedures using implanted prostheses, revealed a 3% reoperation rate for vaginal mesh erosion in 29 of the 858 procedures performed using transvaginal synthetic mesh. Compared to the posterior and apical compartment, mesh erosions, requiring surgical excision, were more commonly seen after anterior compartment transvaginal mesh repairs. (30)

Vaginal Contracture

Erosions may be the most common complication reported in the MAUDE database, however, another unique complication that is often associated with pelvic pain, and perhaps a more morbid sequelae, is mesh contraction, a shrinkage or reduction in the size of the vaginal mesh implant that may lead to mesh prominences or strictures within the vagina. (31) A recent case series reported results of seventeen women undergoing surgical intervention for mesh contraction. All of these women presented with severe vaginal pain and focal tenderness over the contracted portions of the mesh. Furthermore, seven of the seventeen women were noted to have vaginal tightness, and five of the seventeen women reported vaginal shortening. All of the sexually active women within the series reported dyspareunia. (32) Moore et al. discuss the importance of avoiding tension on the levator ani muscle and ligamentous attachments as well as minimizing vaginal epithelium excision and maximizing vaginal estrogen both pre- and postoperatively. (23) Ideal graft augmentation and the avoidance of tensioning can still be complicated by scar tissue formation which may vary from patient to patient. This complication needs to be more robustly characterized and collected in all studies reporting outcomes with synthetic transvaginal mesh augmented prolapse repairs.

Dyspareunia and Vaginal Pain

Weber, et al. reported a dyspareunia rate of 19 percent following traditional reconstructive vaginal surgery for prolapse or incontinence. (32) Dyspareunia rates were reported in 70 of the 110 studies from the SGS review of mesh augmented vaginal repairs with an overall rate of 9.1 percent. (27) Another prospective observational study reported a 20 percent dyspareunia rate after transvaginal synthetic mesh augmentation. (33) As revealed in a recent review of transvaginal synthetic mesh applications for prolapse repair, reported complications of dyspareunia vary from one end of the spectrum to the other. (28) In fact, Nieminen, et al. reported a reduction in dyspareunia for patients undergoing transvaginal synthetic mesh anterior wall repairs as compared to traditional anterior repair. Ninety-seven patients were treated with anterior colporrhaphy and one hundred five were randomized to synthetic transvaginal mesh. The dyspareunia score was lower in the mesh group (p = 0.015). (34) Sentilhes, et al. reported no effect of transvaginal synthetic mesh augmentation on sexual function. (35) As noted in IUGA Grafts Roundtable, post-operative vaginal and pelvic pain following either transvaginal mesh or native tissue repairs for POP is difficult to characterize. (16) In a recent review of 23 patients undergoing transvaginal removal of synthetic mesh for mesh related complications, vaginal pain and dyspareunia were the most noted complications. Excision of synthetic mesh resolved pain in 10 out of the 11 patients. (36)

Other Complications

Seven deaths were reported to the MAUDE database for patients who underwent POP repair procedures with transvaginal mesh. Three of the deaths were related directly to the mesh placement procedure and included two bowel perforations and one hemorrhage. (37) Other major complications have been reported in the literature including retrovesical hematoma formation as well as mesh erosions not simply through the vaginal epithelium but into the bladder. (38) Additionally, vesicovaginal fistula formation after the use of synthetic transvaginal mesh in the anterior compartment has been reported. (39) It is clear that a wide spectrum of complications exists for the use of transvaginal mesh in POP surgery. A thorough understanding of these complications, especially with the perspective of complications associated with native tissue repairs, and the subsequent management of them is imperative to the consideration of synthetic transvaginal mesh use in POP surgery.

Management of Mesh Complications

The majority of mesh complications can be managed conservatively. Some investigators have reported if large bore polypropylene mesh is used, the graft is typically not infected and usually does not have to be completely excised. (23) In the case of mesh extrusions and exposures, many will heal with the use of vaginal antibiotics and or the use of vaginal estrogen cream. Other outpatient management includes the use of local anesthetic and excision of the exposed mesh. (23) Conservative treatments for dyspareunia have also included the application of vaginal estrogen cream. (40) Additional techniques to address postoperative dyspareunia include trigger point injections with anti-inflammatory medications as well as the use of pelvic floor physical therapy. Dyspareunia associated with focal contracture bands or vaginal prominences has been noted to be substantially reduced with surgical excision or release when conservative measures do not alleviate symptoms. (31)

Clinical Correlation with Complications

Anterior Compartment

The historical focus of the use of transvaginal mesh has been to improve anatomical outcomes and improve POP recurrence rates as compared to traditional vaginal repairs for POP. A systematic review reported in 2008 that compared to native tissue repair non-absorbable synthetic mesh may improve anatomic outcomes of anterior vaginal wall repair, but there are increased risks of adverse events. (41) In one of the reviewed studies, the mesh group was reported to have a lower POP recurrence rate (6.7 percent compared to 38.5 percent), however, this was offset by a mesh exposure rate of 17.3 percent. (42)

In a 2010 Cochrane review, higher rates of complications associated with vaginal mesh were reported as compared to native tissue anterior vaginal repairs with a reported mesh erosion rate of 10 percent. (43) In 2008, Jia et al demonstrated lower objective failure rates for non-absorbable synthetic vaginal mesh in comparison with xenografts, absorbable synthetic mesh and no mesh, but mesh erosion rates were highest in the non-absorbable group (10.2 percent for non-absorbable synthetic versus 6.0% percent for xenografts and 0.7 percent for absorbable synthetic mesh). (44) As this was a systematic review, success was variably defined, however, the primary outcomes for efficacy were subjective prolapse symptoms as well as objective measures using both pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) and the Baden-Walker systems.

In a more recent randomized controlled trial of 99 women with stage II or greater anterior prolapse assigned to one of 3 groups: anterior colporrhaphy, paravaginal repair with porcine dermis, or polypropylene mesh, Menefee et al, reported that vaginal paravaginal repair with polypropylene mesh had the lowest anatomic failure rate at 2 year follow-up. The anatomic failure rate, defined as POP-Q stage II or greater was 18 percent for the polypropylene mesh group as compared to 58 percent and 46 percent for the anterior colporrhaphy and porcine dermis groups, respectively. However, as with earlier trials the anatomic benefit, 4 percent recurrence rate of prolapse for synthetic vaginal mesh augmentation as compared to 13 percent for colporrhaphy and 12 percent for porcine dermis, is associated with an erosion rate of 14 percent. (45) Another large randomized trial reported outcomes from 389 women assigned to anterior synthetic transvaginal mesh or anterior colporrhaphy revealed a higher subjective composite success rate for the synthetic mesh arm as compared to the control arm (60.8 percent vs. 34.5 percent, p< 0.001; adjusted odds ratio, 3.6; 95 percent confidence interval, 2.2 to 5.9) but intraoperative complications as well as new onset stress incontinence was observed in the mesh arm compared to traditional repair. Mesh exposure requiring surgical revision occurred in 3.2 percent of patients. (46)

Apical Compartment

In comparison to the transvaginal mesh use in the anterior compartment, abdominal sacrocolpopexy is widely regarded as the gold standard for apical prolapse with success rates reported from 58 to 100 percent depending on outcome definitions. (47) In 2009, a systematic review of 30 studies evaluating a total of 2,653 patients undergoing apical repairs with mesh kits reported success rates from 87 to 95 percent, though outcome definitions varied widely. (48) Abdominal apical repairs with synthetic mesh appear to have lower erosion rates than synthetic transvaginally placed mesh. In 2004, Nygaard, et al reported synthetic mesh erosion rates from 0.5 to 5.0 percent with an average erosion rate of 3.4 percent. (49) The time from surgery in this review ranged from 6 months to 3 years. In a more recent systematic review, it was concluded that when comparing traditional vaginal surgery for apical prolapse to sacral colpopexy, and vaginal synthetic mesh kits, total reoperation rate was highest in the synthetic mesh kit group (8.5 percent) though vaginal synthetic mesh kits had a lower reoperation rate for prolapse recurrence. Complications were highest in the vaginal synthetic mesh group with a mesh erosion rate of 5.8 percent. (50)

Posterior Compartment

Currently, there are no robust comparative studies of posterior colporrhaphy comparing non-absorbable synthetic graft augmentation repair for posterior compartment defects to extract data regarding complications. Two retrospective case series report high success rates of 95 percent and 100 percent, respectively. The first was a series of 22 women, 14 underwent vaginal synthetic mesh repair of posterior compartment defects and 8 received a combination of polyglactin and polypropylene mesh where success was measured by subjective outcomes. (51) The other report was a series of 31 women who underwent posterior colporrhaphy with absorbable mesh placement. One hundred percent anatomic cure rate defined as less than stage II prolapse, as defined by the ICS pelvic organ prolapse grading system, was reported at 17 months postoperatively, however, mesh erosion was noted in 6.5 percent of patients. (33) Despite noted factors where one may consider transvaginal mesh augmentation of vaginal prolapse, outcomes compared to native tissue repair are, in general, short-term, not significantly different subjectively and potential complications are higher although comparator groups are not always available.

Multi-Compartment

Few studies address multi-compartment defects with comparison of vaginal synthetic mesh augmented to traditional native tissue repairs. Iglesia et. al and Withagen et al each performed randomized controlled trials that included patients with multi-compartment defects and neither study revealed improvement in success. (52, 53) In the trial of Iglesia et al, 65 women with POP-Q stages 2-4 were randomized to colpopexy with synthetic mesh or traditional vaginal colpopexy. 33 women were randomized to vaginal synthetic mesh colpopexy (24 anterior mesh, 8 total mesh) and 32 were randomized to traditional repair. The study ultimately was halted due to predetermined criteria for vaginal synthetic mesh erosion. The authors reported a 15.6 percent rate of vaginal erosions. Three months postoperatively, the subjective cure of bulge symptoms was 93.3 percent in the synthetic mesh arm and 100 percent in the traditional arm. The second study aimed to compare efficacy and safety of trocar-guided vaginal synthetic mesh with traditional vaginal repair in a population of patients with recurrent prolapse. (53) Ninety-seven women underwent traditional colporrhaphy and ninety-three underwent synthetic mesh repair. Though subjective improvement was comparable between the two groups (80 percent and 81 percent, respectively), anatomic failure at 12 months, defined as POP-Q stage II or higher was noted, to be 45.2 percent in the traditional arm and 9.6 percent in the mesh arm. (52, 53)

The debate that continues to develop for the care of patients with multi-compartment defects, and especially those with recurrent pelvic organ prolapse, centers around whether to approach repairs vaginally with native tissue, or with transvaginal synethic mesh, or to proceed endoscopically with laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Schmid and colleagues recently reported a prospective case series in which 16 women underwent laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for treatment of recurrent pelvic organ prolapse after trocar-guided transvaginal synthetic mesh repairs. After a mean follow-up of 12 months, all of the patients reported resolution of awareness of prolapse and were found to have < Stage 2 on pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) examination. (54). Iglesia, Hale, and Lucente published a case-base debate regarding appropriate surgical approach toward a patient with recurrent pelvic organ prolapse after native tissue repair and uterosacral ligament suspension. (55) Regarding the laparoscopic approach, only one Level 1 study was cited, a randomized controlled trial of women with stage ≥ 2 vaginal vault prolapse, in which 53 patients were allocated to the laparoscopic sacral colpopexy arm and 55 underwent total transvaginal mesh augmentation. The primary outcome was objective success rates using POP-Q examination. At 2 year follow-up, the total objective success rate at all vaginal sites was 77% for the endoscopic arm and 43% for the total vaginal mesh arm (p<0.001), and notably, the reoperation rate was significantly higher after total vaginal mesh than laparoscopic approach (22% versus 5%, p=0.006). (56) The counter-argument tends to focus on complications related to longer operating room times associated with endoscopic surgery as well as cost comparisons. Regarding outcomes and complication rates between the two approaches, many of the differences are clouded variations of surgeon technique. (53) Furthermore, although serious endoscopic complications, such as bowel obstruction and lumbosacral osteomyelitis are low, the morbidity associated with these complications overshadows transvaginal complications of exposure and extrusion. (57)

Conclusions

Undoubtedly, the primary focus of gynecologists/urogynecologists performing vaginal repairs is patient safety and optimizing outcomes. Maximizing patients’ outcomes and minimizing complications is at the heart of the FDA’s investigations as well the forward momentum in research efforts in this arena. A summary of the FDA’s recommendations for health care providers is seen in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of Recommendations for Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for POP

| In most cases, POP can be treated successfully without mesh thus avoiding the risk of mesh- related complications |

| Mesh surgery should be pursued only after weighing the risks and benefits of surgery with mesh versus all surgical and non-surgical alternatives |

Factors to consider before using surgical mesh:

|

| Inform patients about the benefits and risks of non-surgical options, non-mesh surgery, surgical mesh placed abdominally and the likely success of these alternatives compared to transvaginal surgery with mesh |

| Notify the patient if mesh will be used in her POP surgery and provide the patient with information about the specific product used |

|

Ensure that the patient understands the postoperative risks and complications of mesh surgery as well as limited long-term outcomes data |

Adapted from FDA (10)

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) collaborated in an ACOG Committee Opinion release entitled Vaginal Placement of Synthetic Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse, released in December 2011. The Committee Opinion sought to address several concerns including the existing outcome data for the vaginal mesh placement for POP as well as a review of the complications of vaginal mesh surgery. A summary of the recommendations from this joint committee is in Table 5. (57)

Table 5.

Recommendations for the Safe and Effective Use of Vaginal Mesh for Repair of POP

| Outcome reporting for prolapse surgical techniques must clearly define success both objectively and subjectively. Complications and total reoperation rates should be reported as outcomes |

|

POP vaginal mesh repair should be reserved for high-risk individuals in whom the benefit of mesh placement may justify the risk |

|

Surgeons should undergo training specific to each device and have experience with reconstructive surgical procedures and a thorough understanding of pelvic anatomy |

|

Compared to existing mesh products and devices, new products should not be assumed to have equal or improved safety and efficacy unless long-term data are available |

|

ACOG and AUGS support continued audit and review of outcomes, as well as the development of a registry for surveillance for all current and future vaginal mesh implants |

|

Rigorous comparative effectiveness randomized trials of synthetic mesh and native tissue repair and long-term follow-up are ideal |

|

Patients should provide their informed consent after reviewing the risks and benefits of the procedure, as well as discussing alternative repairs |

Adapted from ACOG/AUGS (53)

Physicians need to continue to review the literature, report their own outcomes, and educate patients regarding new outcome data, complications and recommendations from national organizations in women’s health regarding prolapse repair. Surgeons with specialized training in native tissue and use of synthetic mesh augmented repairs and management of complications inherent in both groups should be at the forefront of delivering care to women affected by POP.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: 2 K24 DK68389 to HER

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Drs Richter and Ellington have no relevant conflicts of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Nygaard I, et al. NHANES. Prevalence of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in US Women. JAMA. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tegerstedt G, Maehle-Schmidt M, Nyrén O, Hammarström M. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse in a Swedish population. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16:497. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-1326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rortveit G, Brown JS, Thom DH, et al. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse: prevalence and risk factors in a population-based, racially diverse cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:1396. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263469.68106.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones KA, Shepherd JP, Oliphant SS, et al. Trends in inpatient prolapse procedures in the United States, 1979-2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:501.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith FJ, Holman CD, Moorin RE, Tsokos N. Lifetime risk of undergoing surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1096. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f73729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blandon RE, Bharuch AE, Melton LJ, et al. Incidence of pelvic floor repair after hysterectomy: A population-based cohort study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:664.e.1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whiteside JL, Weber AM, Meyn LA, Walters MD. Risk factors for prolapse recurrence after vaginal repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1533–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sung VW, Rogers RG, Schaffer JI, Balk EM, Uhlig K, Lau J, et al. Graft use in transvaginal pelvic organ prolapse repair: a systematic review. Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1131–42. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181898ba9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Drug Administration . FDA safety communication: UPDATE on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Silver Spring (MD); FDA: 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/ucm.262435.htm. Retrieved July 27, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Response of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists to the FDA’s 2011 Patient Safety Communication: Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Jul 13, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Executive Committee Statement Regarding the FDA Communication: Surgical placement of mesh to repair pelvic organ prolapse imposes risks. Jul 25, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Urogynecologic Society Response: FDA Safety Communication: Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Jul, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Society for Female Urology and Urodynamics Response: FDA Safety Communication: Update on serious complications associated with transvaginal placement of surgical mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. Jul, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelovsek JE, Barber MD. Women seeking treatment for advanced pelvic organ prolapse have decreased body image and quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1455–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.01.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davila GW, Baessler K, Cosson M, Cardozo L. Selection of patients in whom vaginal graft use may be appropriate. Consensus of the 2nd IUGA Grafts Roundtable: Optimizing safety and appropriateness of graft use in transvaginal pelvic reconstructive surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:S7–S14. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arya LA, Novi JM, Shaunik A, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse, constipation and dietary intake in women; a case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1687–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Araco F, Gravante G, Sorge R, Overton J, DeVita D, et al. the influence of BMI, smoking and age on vaginal erosions after synthetic mesh repair for pelvic organ prolapses. A multicenter study. Acta Obstet Gynecol. 2009;88:772. doi: 10.1080/00016340903002840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen CC, Collins SA, Rodgers AK, Paraiso MF, Walters MD, Barber MD. Perioperative complications in obese women vs. normal weight women who undergo vaginal surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:98. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collinet P, Belot F, Debodinance P, HaDuc E, Lucot JP, Cosson M. Transvaginal mesh technique for pelvic organ prolapse repair: mesh exposure management and risk factors. Int Urogynecol J. 2006;17:315. doi: 10.1007/s00192-005-0003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowman JK, Woodman PJ, Nosti PA, Bump RC, Terry CL, Hale DS. Tobacco use is a risk factor for mesh erosion after abdominal sacral colpoperineorrhaphy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:561e1–561e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caquant F, Collinet P, Debodinance P, et al. Safety of transvaginal mesh procedure: retrospective study of 684 patients. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34(4):449–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2008.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore RD, Miklos JR. Vaginal mesh kits for pelvic organ prolapse, friend or foe: a comprehensive review. The Scientific World Journal. 2009;9:163–189. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang AC, Lee L, Lin CT, Chen JR. A histologic and immunohistochemical analysis of defective vaginal healing after continence taping procedures: a prospective case-controlled pilot study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1868–1874. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brill AI. The hoopla over mesh: what it means for practice. Obstetrics and Gynecology News. Jan. 2012:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:3. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abed H, Rahn DD, Lowenstein L, Balk EM, Clemons JL, Rogers RG, Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group Incidence and management of graft erosion, wound granulation, and dyspareunia following vaginal prolapse repair with graft materials: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2011 Jul;22(7):789–98. doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1384-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rardin CR, Washington BB. New considerations in the use of vaginal mesh for prolapse repair. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16:360–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brubaker L, Glazener C, Jacquentin B, Maher C, Melgrem A, Norton P, et al. 4th International Consultation on Incontinence. Recommendations of the International Scientific Committee: evaluation and treatment of urinary incontinence, pelvic organ prolapse and faecal incontinence. Paris, France; Jul 5-9, 2008. Surgery for pelvic organ prolapse; pp. 1273–320. Available at: http://www.icsoffice.org/Publications/ICI_4/files-book/comite-15.pdf. Retrieved June 2nd, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen J, Jakus-Waldman S, Walter A, White T, Menefee S. Perioperative complications and reoperations after incontinence and prolapse surgeries using prosthetic implants. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119:539–546. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182479283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition, clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:325–330. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181cbca4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber AM, Walter MD, Piedmonte MR. Sexual function and vaginal anatomy in women before and after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1610–15. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milani R, Salvatore S, Soligo M, et al. Functional and anatomical outcome of anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse repair with prolene mesh. BJOG. 2005;112:107. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nieminen K, Hitunen R, Heiskanen E, Takala T. Symptom resolution and sexual function after anterior vaginal wall repair with or without polypropylene mesh. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysunct. 2008;19:1611–1616. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0707-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sentilhes L, Berthier A, Sergent F, et al. Sexual function in women before and after transvaginal mesh repair for pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19:763–772. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0521-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Firoozi F, Ingber M, Moore C, Vasavada S, Rackley R, Goldman H. Purely transvaginal/perineal management of complications from commercial prolapse kits using a new prostheses/grafts complication classification system. J Urology. 2012;187:1674–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.FDA Executive Summary Surgical mesh for the treatment of women with pelvic organ prolapse and stress urinary incontinence; Obstetrics and Gynecology Devices Advisory Committee Meeting; 2011.Sep 8-9, [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ignjatovic I, Stosic D. Retrovesical haematoma after Prolift procedure for cystocele correction. Int Urogynecol J. 2007;18:1495–1497. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0396-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada BS, Govier FE, Stefanovic KB, Kobashi KC. Vesicovaginal fistula and mesh erosion after Perigee (transobturator polypropylene mesh anterior repair) Urology. 2006;68(5):1121–e5. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flood CG, Drutz HP, Waja L. Anterior colporrhaphy reinforced with Marlex mesh for the treatment of cystoceles. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 9:200–204. doi: 10.1007/BF01901604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murphy M. Clinical practice guidelines on vaginal graft use from the society of gynecologic surgeons. Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Systematic Review Group. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1123–30. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318189a8cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hiltunen R, Nieminen K, Takala T, Heiskanen E, Merikari M, Niemi K, et al. Low-weight polypropylene mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:455–62. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000261899.87638.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Glazener CM. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub4. Issue 4 Art.No.:CD004014.DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jia X, Glazener C, Mowatt G, Jenkinson D, Fraser C, Bain C, Burr J. Systematic review of the efficacy and safety of using mesh in surgery for uterine or vaginal vault prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2010;21:1413–1431. doi: 10.1007/s00192-010-1156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menefee SA, Dyer KY, Lukacz ES, Simsiman AJ, Luber KM, Nguyen JN. Colporrhaphy compared with mesh or graft-reinforced vaginal paravaginal repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1337–44. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318237edc4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altman D, Vayrynen T, Engh ME, Axelsen S, Falconer C, Nordic Transvaginal Mesh Group Anterior colporrhaphy versus transvaginal mesh for pelvic organ prolapse. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1826–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Culligan PJ, Blackwell L, Goldsmith LJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing fascia lata and synthetic mesh for sacral colpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:29. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000165824.62167.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feiner B, Jelovsek JE, Maher C. Efficacy and safety of transvaginal mesh kits in the treatment of prolapse of the vaginal apex: a systematic review. BJOG. 2009;116:15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.02023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:805. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139514.90897.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, Maher C, Jelovsek JE. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:367–373. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318195888d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mercer-lnameJones MA, Sprowson A, Varma JS. Outcome after transperineal mesh repair of rectocele: a case-series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:864. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0526-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iglesia CB, et al. Vaginal mesh for prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:293–303. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e7d7f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Withagen MI, et al. Trocar-guided mesh compared with conventional vaginal repair in recurrent prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:242–50. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318203e6a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmid C, et al. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for recurrent pelvic organ prolapse after failed transvaginal polypropylene mesh surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1926-5. DOI 10.1007/s00192-012-1926-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Iglesia C, Hale D, Lucente V. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy vesus transvaginal mesh for recurrent pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1918-5. DOI 10.1007/s00192-012-1918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Maher CF, Feiner B, DeCuyper EM, Nichols CJ, Hickey KV, O’Rouke P. Laparoscopic sacral colpopexy versus total vaginal mesh for vaginal vault prolapse: a randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):360.e1–360.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McDermott CD, Hale DS. Abdominal, laparoscopic, and robotic surgery for pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36(3):585–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion: Vaginal Placement of Synthetic Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Dec, 2011. Number 513. [Google Scholar]