Summary

Elucidation of cellular and gene regulatory networks (GRNs) governing organ development will accelerate progress toward tissue replacement. Here, we have compiled reference GRNs underlying pancreas development from data mining that integrates multiple approaches including mutant analysis, lineage tracing, cell purification, gene expression and enhancer analysis, and biochemical studies of gene regulation. Using established computational tools, we integrated and represented these networks into frameworks that should enhance understanding of the surging output of genomic-scale genetic and epigenetic studies of pancreas development and diseases like diabetes and pancreatic cancer. We envision similar approaches would be useful for understanding development of other organs.

Pancreas development and cell differentiation

The pancreas is an exocrine and endocrine organ. Its exocrine functions derive from acinar cells, which produce zymogens that aid with nutrient digestion, and from duct cells, which form branched tubules that secrete bicarbonate and deliver zymogens for activation in the duodenum. Pancreatic endocrine function derives from hormone-secreting epithelial clusters called Islets of Langerhans that include β-cells which produce insulin. Below, we briefly outline aspects of development relevant for our discussion of pancreas GRNs. Pancreas morphogenesis begins with evagination of embryonic endoderm to form dorsal or ventral ‘buds’, whose development is guided by distinct transcription programs (reviewed in Zaret, 2008). Pancreatic progenitor cells arise around embryonic day (E) 9.0, first expressing the homeodomain transcription factor Pdx1, then the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) factor Ptf1a (reviewed in Seymour and Sander, 2011; Benitez et al 2012). Early growth and branching of pancreatic epithelium is regulated by fibroblast growth factor signaling derived from surrounding mesenchyme tissue (Bhushan et al., 2001), to form defined cellular domains beginning after E11. This includes a ‘tip’ domain containing multipotent pancreatic progenitor cells harboring the potential to self renew or differentiate into pro-acinar cells, and a ‘trunk’ domain harboring ‘bipotent’ cells that give rise to endocrine islet cells or exocrine ducts (reviewed in Benitez et al., 2012). After E13, the tip domain loses its multipotency and becomes a pro-acinar region, which then gives rise to mature acinar cells (Zhou et al., 2007). Further development is accompanied by marked branching of pancreatic epithelial cells and islet formation.

Multipotent pancreatic progenitors express Sox9 (Seymour et al., 2007), and after E13.5, Sox9 expression is restricted to bipotent trunk cells (Lynn et al., 2007; Solar et al., 2009; Kopp et al., 2011). These bipotent epithelial cells generate duct cells or a transient population of endocrine precursor cells expressing the bHLH factor, Neurogenin3 (Neurog3). Neurog3+ endocrine precursors generate the principal islet endocrine cells: glucagon+ α-cells, insulin+ β-cells, somatostatin+ δ-cells, pancreatic polypeptide+ PP cells, and a transient fetal population expressing ghrelin, called ε-cells (Arnes et al., 2012). In mice, expression of Neurog3 in the developing pancreas is transient, detectable between E11.5 and E18, and restricted to developing hormoneneg cells, while in humans, Neurog3 expression is maintained for many weeks during pancreas development and readily detected in hormone+ cells (Lyttle et al., 2008; McDonald et al., 2012). Evidence suggests Neurog3+ cells are post-mitotic (Miyatsuka et al., 2011) and that a single Neurog3+ cell gives rise to a single type of hormone+ islet cell (termed ‘unipotency’ (Desgraz and Herrera, 2009). Thus, pancreas development and cell differentiation may be viewed as a series of morphological and cellular ‘transitions’ to generate several distinct types of differentiated functional epithelial cells (Figure 1A). Below we provide a coherent set of gene regulatory networks framing these transitions.

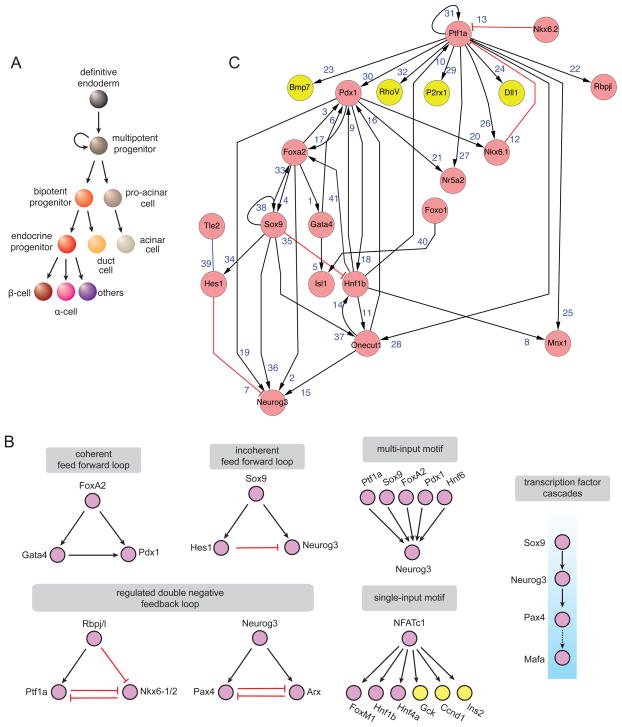

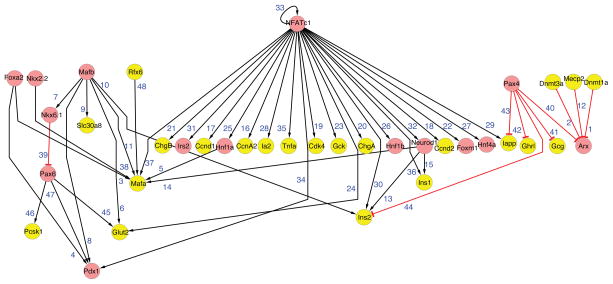

Figure 1. Pancreas cell lineage and gene regulatory motifs in development.

(A) Current lineage model of pancreatic cell differentiation. Key factors that mark each lineage are: FoxA2 - definitive endoderm, Pdx1/Ptf1a/Sox9/Nkx6.1 - multipotent progenitor, Nkx6.1/Sox9 - bipotent progenitor, Ptf1a - pro-acinar and acinar cell, Neurog3 - endocrine progenitor, Sox9 - duct cell, Nfatc1/Ins - β-cells, Arx/Gcg - α-cell.

(B) Sub-circuits of pancreas gene regulatory network representing canonical network motifs.

(C) Pancreatic progenitor gene regulatory network. Pink nodes - transcription factors, yellow nodes - effector genes, black lines - positive/inductive relation, red lines - negative/inhibitory relation.

GRNs that control pancreas development

Cellular differentiation and organ morphogenesis in fetal development are orchestrated by coordinated interactions between diverse components including genes linked through regulatory networks known as GRNs (Davidson, 2006). Discovery of individual components and their network relationships is critical for predicting and manipulating the behavior of complex biological systems; GRNs provide testable predictions that are not resolvable using more simplistic views of gene regulation. Collectively the interactions that make up GRNs appear visually complex, but at their heart are simpler building blocks called ‘canonical sub-circuits’ or ‘network motifs’ (Davidson, 2006; Alon, 2007) (Figure 1B). These smaller circuits generally consist of two or three nodes and are defined by their unique topologies of positive or negative interactions (see below), which accomplish specialized developmental programs or tasks. Establishment of the animal body plan is a result of hierarchical and modular use of these sub-circuits, whose topology has been selected and conserved through evolution of different species. Our aim is to highlight pancreas development from the perspective of network architecture and discuss the implications for studies of tissue regeneration and cellular reprogramming.

To compile regulatory networks of mouse pancreas development, we manually curated interactions by data and literature mining. We focused on interactions involving transcription factors that establish, specify and maintain the development, fate and function of major pancreatic cell types in the mouse (Figure 1A). We assessed each reported interaction (network ‘edge’) between a regulator gene and a target gene (network ‘nodes’), and categorized these as ‘positive’ if the regulator enhanced the target expression, or ‘negative’ if the regulator was reported to diminish target gene expression. A connection by an edge simply denotes evidence for an interaction, not necessarily a physical interaction. The type of experimental evidence reported for each interaction, including biochemical evidence for direct interactions between regulator and target gene (accompanied by the NCBI PubMed citation number) is provided in Table S1. We displayed the network interactions using Cytoscape (version 2.8.1) with hierarchical layout options (Shannon et al., 2003).

GRNs for specifying the pancreas anlage and multipotent pancreatic progenitor cells

To initiate pancreas development, cells derived from posterior foregut endoderm commit to form the pancreatic anlage. How is this anlage selected? Prior studies implicate signaling mediated by FGF TGF-β, and other factors (Deutsch et al., 2001; Bort et al., 2004), as well as chromatin regulation by Ezh2 and histone acetyltransferase P300 (Xu et al., 2011). However, additional studies are needed to understand the gene regulatory network governing this early stage of pancreas development. Prior studies suggest that co-expression of Ptf1a and Pdx1 may subsequently commit gut endoderm to a pancreatic fate (Afelik et al., 2006; Wiebe et al., 2007), perhaps through a ‘coincidence detection’ mechanism, in which the cells of the prospective pancreatic anlage need to receive two different input signals simultaneously to define a new regulatory state. Once established, this new regulatory state is stabilized by positive feedback circuitries that involve both Ptf1a autoregulation and direct Ptf1a induction of Pdx1 expression in pancreatic progenitor cells (Wiebe et al., 2007; Masui et al., 2008). Deficiency of either factor leads to severe pancreas malformations, including agenesis in humans (Stoffers et al., 1997; Sellick et al., 2004). Likewise, loss of Hnf1b (Haumaitre et al., 2006) Mnx1 (also called Hb9 or Hlxb9; (Harrison et al., 1999; Li et al., 1999), Gata4 and Gata6 (Lango Allen et al., 2012; Xuan et al., 2012)also leads to partial or complete pancreas agenesis. Gata4, FoxA2 and Pdx1 might be operating in a coherent positive feed forward loop (Figures 1B and 1C) with so-called ‘AND logic’ (Alon, 2007). The coherent feed forward loop feature in developmental networks may enhance generation of a coordinated pulse of gene expression specifying competent late embryonic endoderm toward a pancreatic fate. We speculate that a requirement for rapid diversification of gastrointestinal tract epithelium in the latter half of development in mice (10 days) may have selected for this feature. Retinoic acid signaling pathways likely reinforce this loop (Martín et al., 2005).

Following commitment of dorsal and ventral endoderm to a pancreatic fate, self renewing multipotent progenitor cells expressing Ptf1a, Pdx1, Sox9, Hnf6 and Nkx6.1 emerge around E11.5 (Figure 1C) (Lynn et al., 2007; Seymour et al., 2007). Prior studies (Stanger et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2007; T. Sugiyama and S.K., submitted) suggest that these multipotent cells represent a transient population ‘depleted’ by ~E14. In a current lineage model (Figure 1A), multipotent progenitors can self renew or differentiate to form exocrine or endocrine progenitors. Analysis of GRN features in progenitor cells, like Ptf1a autoregulation in a feed forward loop, suggests mechanisms for re-enforcing and sustaining proliferation and multipotency in this progenitor cell population. The natural transience of multipotent population in fetal pancreas may reflect cell intrinsic or non-autonomous mechanisms (or both). For example, the GRN of these progenitors contains several transcription factor cascades producing a sequential activation of factors (Figure 1B). In other developing organs this regulatory logic generates differentiated cells with increasingly restricted potential.

GRNs controlling pancreatic progenitor cell differentiation

Other than self-renewal, Sox9+ Pdx1+ Ptf1a+ Nkx6+ multipotent progenitor cells appear to have two principal fate choices, (1) differentiation to immature exocrine acinar (pro-acinar) cells expressing Ptf1a and Rpbj or (2) differentiation into bipotent Nkx6.1+ cells that generate exocrine duct cells expressing Sox9, or generate endocrine progenitor cells expressing Neurog3 (Figure 1A; Iype et al., 2004; Masui et al., 2008). Incisive analysis by Sander and colleagues (Schaffer et al., 2010) has revealed that a modified double negative feedback loop between Ptf1a and Nkx6.1/2 (Figures 1B and 1C) regulates differentiation of multipotent pancreatic progenitors to one of these two fates. In their model, based on gain- and loss-of-function studies, Ptf1a induces a pro-acinar cell program while the Nkx6.1/2 factors specify progenitors to an alternate fate that engenders Sox9+ Hnf1b+ ‘bipotential’ cells with the capacity to produce duct and endocrine islet progeny. The action of a regulated double negative feedback loop at this stage results in mutually exclusive expression of Ptf1a and Nkx6.1/2 and defines the boundaries of these two spatial domains (Davidson, 2010).

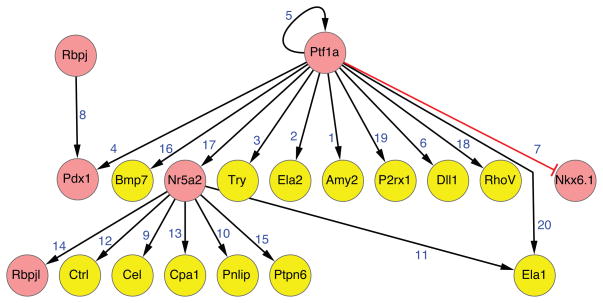

Reciprocal repression appears to be a general mechanism to regulate and stabilize lineage commitment choices in a variety of tissues (Briscoe et al., 2000). Thus the Ptf1a-Nkx6 bistable network structure in pancreatic progenitor cells may ensure that - once initiated - the cell fate is ‘locked’ into a transcriptional state that promotes establishment of chromatin-mediated cellular memory. Many aspects of this model warrant further investigation. For example, Ptf1a is thought to function principally in transcriptional activator complexes; however it is possible that the PTF1 complex might be interacting with yet unidentified co-repressor proteins. Recent studies modeling pancreas development with embryonic stem cell culture systems suggest that the Nkx6-Ptf1a motif may be regulated by extracellular signaling, including TGF-β pathways (Micallef et al., 2012; Guo, et al., 2013). In pro-acinar cells Ptf1a regulates maturation first by activating RBPJ, the vertebrate orthologue of Supressor of Hairless. Ptf1a and RBPJ function in a complex to induce expression of RBPJL, the constitutively active, pancreas-restricted paralog of RBPJ. As acinar cells mature, RBPJL replaces RBPJ in the PTF1 complex bound to Rbpjl and also associates with the promoters of other acinar-specific genes, including those encoding exocrine digestive enzymes (Beres et al., 2006; Fujikura et al., 2007; Masui et al., 2008). Thus acinar cell maturation is regulated by a positive feed forward loop governed by a dynamic Ptf1a transcriptional complex (Figure 2). There are intensive efforts underway to use ChIP-based approaches to identify Ptf1a-associated genetic targets in pancreatic progenitors, pro-acinar and acinar cells (Thompson et al., 2012). These - and related efforts to identify co-factors in Ptf1a transcription factor complexes - should eventually reveal the regulatory logic for producing and maintaining pro-acinar cells and acinar cells, and shed light on the GRN features related to pancreatic progenitor regulation by Ptf1a.

Figure 2. Gene regulatory network of differentiating acinar cells.

See text for details.

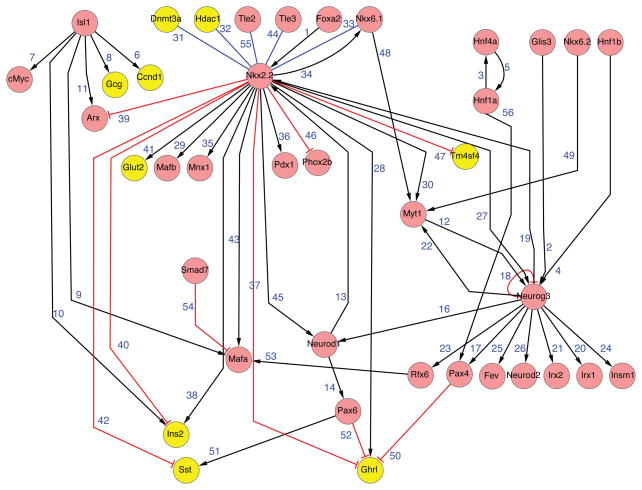

GRN governing the transition to pancreatic endocrine progenitor cells

A crucial transition in pancreas development is the differentiation of bipotent Sox9+ Nkx6.1+ cells to generate ducts and Neurog3+ endocrine progenitors. One critical component of this fate choice appears to be the levels of Neurog3 expression. Recent studies suggest that Neurog3 expression must surpass a threshold in order to commit progenitors to an endocrine fate (Wang et al., 2010; Magenheim et al., 2011). Remarkably, these studies show that the development of Neurog3-expressing cells towards an endocrine fate is reversible. For example, progeny of bipotent progenitors that initiate transcription of a null Neurog3 allele lack Neurog3 protein but survive and remain within the epithelium, and later acquire a ductal or acinar cell phenotype fate (Wang et al., 2010; Magenheim et al., 2011). It should be useful to identify Neurog3 targets systematically at different stages of pancreatic epithelial development (E11 and later), to elucidate the GRN mechanisms underlying these striking examples of in vivo fate conversion in the pancreas. Likewise, elucidating mechanisms regulating Neurog3 expression (for example, see Johnson et al 2007) is a current focus of investigation by multiple groups. Neurog3 expression may be regulated by an incoherent positive feed-forward loop (Figure 1B, (Alon, 2007) in which Sox9 activates both Neurog3 and Hes1, a repressor of Neurog3 expression (Jensen et al., 2000). Prior studies suggest that Hes1 coordinates input from intercellular signaling, particularly the Notch pathway (Apelqvist et al., 1999; Jensen et al., 2000). Recent studies also revealed that Ptf1a controls Dll1 to restrain Neurog3 expression (Ahnfelt-Rønne et al., 2012).

Feed forward loop regulation can promote pulsatile gene expression and is associated with cell fate specification in several systems, but the features in the Neurog3 locus that control transient expression are poorly understood. There is evidence suggesting that Neurog3 may positively or negatively autoregulate its own gene expression (Smith et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2008; Ejarque et al., 2013). Building models that incorporate these types of autoregulation may reveal how cis-regulatory elements in the Neurog3 locus function. For example, low affinity enhancers that associate with Neurog3 to mediate repression may underlie both the rise and fall of Neurog3 expression. Alternately, positive autoregulatory elements could enhance initial increases of Neurog3 expression. Precedents for such models include studies of enhancer with distinct binding affinities for trans-acting factors in Drosophila (Jiang and Levine, 1993; Papatsenko and Levine, 2005).

Neurog3+ cells are post-mitotic and express Cdkn1a (Miyatsuka et al., 2011), and acquire features of mesenchyme, including the ability to migrate and form islets (Gouzi et al., 2011). Thus, GRNs describing development of pancreatic endocrine progenitors will likely incorporate modules governing cell cycle control, epithelial-mesenchymal transitions, and islet cell specification. How unipotent endocrine progenitors commit to specific islet cell fates also remains an open question. Prior studies have shown that the developmental stage when Neurog3 is active can influence the type of endocrine cell generated (Johansson et al., 2007). The authors suggested that Neurog3-expressing cells transit through different ‘competence’ periods that promote formation of α-cells, followed by β-cells then δ and PP-cells. The signaling-, genetic- or chromatin-regulated basis for this finding has not been elucidated, but likely connects with elements defining a double-negative feedback loop, including Neurog3, Nkx2.2, Pax4 and Arx (Figures 1B and 3; Collombat et al., 2003, 2005, 2009; Kordowich et al., 2011; Papizan et al., 2011), central to islet cell fate allocation. The core element in this loop is direct reciprocal repression by the homeodomain factors Pax4 and Arx (Collombat et al., 2003, 2005, 2009), a motif known to control and maintain lineage choices in development (Figure 1B). MafB, MafA, Is1 and Pdx1 are also important determinants of α-cell and β-cell fate (Artner et al., 2010; Hang and Stein, 2011; Yang et al., 2011) and networks linking the Pax4-Arx regulatory loop and these factors are being established (Liu et al., 2011; Hunter et al., 2012). However, our understanding is far from complete. For example, a direct reciprocal repression by Arx and Pax4 in an unmitigated double-negative feedback loop would produce an “ON-OFF” state for these factors. However, loss of Arx or Pax4 does not lead to complete loss of beta cells or alpha cells (Collombat et al., 2005). Thus, from GRN considerations, we predict discovery of additional regulators that modulate Arx or Pax4 expression to control apportioning of cell fates during islet cell differentiation (Figure 1B). With the advances of cell sorting followed by global chromatin and RNA analysis using small number of cells, and methods to assess gene function in a developmentally-relevant context, we anticipate rapid expansion and understanding of cell-specific, time-specific networks on a genome-wide scale.

Figure 3. Endocrine progenitor gene regulatory network.

See text for details.

GRN governing pancreatic β-cell maturation and fate

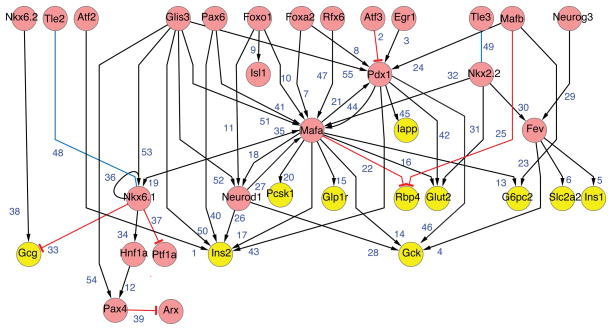

Compared to knowledge about the genetic control of fetal pancreas development or adult β-cells (Figure 4), less is known about the GRNs governing late fetal and postnatal pancreas development. Once formed, islet β-cells proliferate and acquire physiological functions promoting their principal roles in nutrient sensing and insulin secretion. Knowledge about the GRNs governing adult β-cell function (Figure 4) is dominated by studies revealing the functions of transcription factors implicated in monogenic forms of diabetes, called maturity onset diabetes in the young (MODY), including Pdx1, Hnf1a, Hnf1b, Hnf4a, and NeuroD1. Recent studies show that β-cell ‘maturation’ and expansion is regulated by the Ca2+-regulated calcineurin/NFAT pathway (Figure 5; Heit et al., 2006; Goodyer et al., 2012; references therein). Cn/NFAT signaling is required for the appropriate post-natal expression of cell cycle regulators that promote β-cell growth, including CcnD2, FoxM1 and CcnA2, for expression of genes encoding MODY factors (Figure 5, Heit et al., 2006) and components crucial for insulin production, processing, storage and secretion (Goodyer et al., 2012). Cn/NFAT pathways also regulate ‘activity-dependent’ development, functional maturation and expansion in other tissues and cells, including neurons, muscle, bone and lymphocytes; thus knowledge from GRN investigations in these contexts may expand understanding of Cn/NFAT roles in β-cell maturation. The transcription factors MafB, MafA, and Glis3 are linked to this network and also regulate post-natal development of islet β-cells (Artner et al., 2008, 2010; Kang et al., 2009). The structure of this sub-circuit can be considered a ‘single input motif’ or ‘a gene battery’ (Figures 1B and 3). In these structures, the regulator has a high number of outgoing links, and may coordinately control a cohort of effector genes. This enables cells to coordinate the activity of a group of genes that function in the same or related pathways.

Figure 4. Immature β-cell gene regulatory network.

See text for details.

Figure 5. Adult β-cell gene regulatory network.

See text for details

Information about GRNs controlling β-cell maturation in juvenile animals will grow in the near future, given the intensive worldwide efforts in this area, and enabled by knowledge about physiological and intercellular regulators of β-cell growth and maturation like glucose, incretins, Ca2+ and glucokinase (Puri and Hebrok, 2010; Seymour and Sander, 2011; Benitez et al., 2012; Goodyer et al., 2012). Studies of adult β-cell fate should also inform our understanding of β-cell maturation. Likewise, studies of cycling adult β-cells should demonstrate how regulatory networks change when β-cells proliferate. Do β-cells, perhaps similar to proliferating hepatocytes (Klochendler et al., 2012) have programs permitting controlled de-differentiation? If so, are the regulatory networks that govern β-cell development simply reestablished? For example, loss of Insulin expression has been repeatedly observed in β-cells driven to proliferate in culture (Chen et al., 2011; Figure 5), or deficient in mechanisms that re-enforce β-cell fate (Dhawan et al., 2011). Studies of Insulin chromatin and the GRN, including MODY factors, governing expression of β-cell Insulin might reveal that naturally cycling β-cells also transiently de-differentiate to accommodate the requirements of cell cycle progression and division. This possibility is underscored by recent studies, including those by Accili and colleagues (Talchai et al., 2012) providing evidence for de-differentiation of adult islet β-cells in animal models of diabetes. Identification of GRNs governing natural or pathological de-differentiation in β-cells might advance efforts to convert or re-program non-β cells toward a β-cell fate (Zhou et al., 2008). For instance, current reprogramming protocols involve constitutive over-expression of pancreatic factors, but GRN-guided reprogramming protocols, which would mimic the dosage, combinatorial logic, and temporal expression of normal pancreatic development, may generate functional β-cells with better efficiency.

Summary and prospects

For this perspective, we compiled a set of regulatory networks that represent development of major pancreatic cell types in the mouse based on literature mining. However, these networks remain far from being complete. A systematic catalog of transcription factors and cis-regulatory information that coordinates the regulation of target genes would provide essential building blocks of GRNs. Application of genome-scale assays to query gene expression profiles and chromatin states of purified pancreatic cell types at distinct developmental stages should provide an experimental strategy to expand the regulatory networks presented here. The insights obtained from studying developmental GRNs can have applications that range from building synthetic circuits in reprogrammed cells (Ruder et al., 2011) to finding pharmacological agents with minimal off-target effects. Despite some initial successes, cell reprogramming or conversion to generate medically-important cell types like functional pancreatic islet cells remains relatively inefficient and stochastic, likely reflecting an ignorance of important regulatory interactions that exist during pancreas development. Advances in developmental and stem cell biology also reveal an unexpected degree of flexibility in developing or diseased cells, and the regulatory networks that underlie acquisition or maintenance of cell fate and physiological functions. This may be particularly important for some adult organs, including the pancreas, which may lack a dedicated ‘stem cell’ and therefore require maintenance of cell and tissues function through self-renewal of differentiated cells instead of neogenesis.

Similar approaches should be possible for studies of human pancreas development and for building gene regulatory networks of human pancreas. For instance, using cell surface markers and flow cytometry it is possible to enrich for adult human β-cell, α-cell, acinar and ductal cell populations (Dorrell et al., 2011). Expanding this strategy to human juvenile and fetal pancreas would permit gene expression analysis that can ultimately guide mapping gene regulatory networks of human pancreas. In addition, integrating the data available from the ENCODE consortium regarding open chromatin sites, chromatin interactions, transcription factor motif information, and from gene-centered studies such as enhanced yeast one-hybrid assays (Reece-Hoyes et al., 2011) should prove fruitful for generating comprehensive maps of gene regulatory networks. Taken together, the analysis of these networks would provide insights beyond single-factor centered pathways, generate a more global view of pancreas development, and guide regenerative therapies by presenting alternative ways to reprogram cells into different pancreatic fates. The general points we discussed in this perspective should be applicable to other organ systems.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. List of interactions compiled to represent the gene regulatory networks of pancreas development.

Acknowledgments

We thank H. Chakravarthy, J. Lee, P. Pauerstein, T. Sugiyama, P. Wang for their contributions to construct the GRNs described here, and the members of the Kim group, and Drs. L. Sussel, R. MacDonald, J. Ferrer and R. Stein for discussions or critical reading of this manuscript. H.E.A. is supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF) postdoctoral fellowship. C.B. is supported by an NIH Developmental Genetics training grant. Work in the Kim group has been supported by the Snyder Foundation, the Elser Foundation, the Doolittle Charitable Trusts, the Helmsley Charitable Trust, JDRF, U.S. NIH Beta Cell Biology Consortium and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). S.K.K. is an Investigator of the HHMI. We apologize to colleagues whose work we could not cite because of space constraints.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Afelik S, Chen Y, Pieler T. Combined ectopic expression of Pdx1 and Ptf1a/p48 results in the stable conversion of posterior endoderm into endocrine and exocrine pancreatic tissue. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1441–1446. doi: 10.1101/gad.378706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahnfelt-Rønne J, Jørgensen MC, Klinck R, Jensen JN, Füchtbauer EM, Deering T, MacDonald RJ, Wright CVE, Madsen OD, Serup P. Ptf1a-mediated control of Dll1 reveals an alternative to the lateral inhibition mechanism. Development. 2012;139:33–45. doi: 10.1242/dev.071761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apelqvist A, Li H, Sommer L, Beatus P, Anderson DJ, Honjo T, Hrabe de Angelis M, Lendahl U, Edlund H. Notch signalling controls pancreatic cell differentiation. Nature. 1999;400:877–881. doi: 10.1038/23716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnes L, Hill JT, Gross S, Magnuson MA, Sussel L. Ghrelin expression in the mouse pancreas defines a unique multipotent progenitor population. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artner I, Hang Y, Guo M, Gu G, Stein R. MafA is a dedicated activator of the insulin gene in vivo. J Endocrinol. 2008;198:271–279. doi: 10.1677/JOE-08-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artner I, Hang Y, Mazur M, Yamamoto T, Guo M, Lindner J, Magnuson MA, Stein R. MafA and MafB regulate genes critical to beta-cells in a unique temporal manner. Diabetes. 2010;59:2530–2539. doi: 10.2337/db10-0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez CM, Goodyer WR, Kim SK. Deconstructing pancreas developmental biology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012:4. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beres TM, Masui T, Swift GH, Shi L, Henke RM, MacDonald RJ. PTF1 is an organ-specific and Notch-independent basic helix-loop-helix complex containing the mammalian Suppressor of Hairless (RBP-J) or its paralogue, RBP-L. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:117–130. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.117-130.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan A, Itoh N, Kato S, Thiery JP, Czernichow P, Bellusci S, Scharfmann R. Fgf10 is essential for maintaining the proliferative capacity of epithelial progenitor cells during early pancreatic organogenesis. Development. 2001;128:5109–5117. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bort R, Martinez-Barbera JP, Beddington RSP, Zaret KS. Hex homeobox gene-dependent tissue positioning is required for organogenesis of the ventral pancreas. Development. 2004;131:797–806. doi: 10.1242/dev.00965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe J, Pierani A, Jessell TM, Ericson J. A homeodomain protein code specifies progenitor cell identity and neuronal fate in the ventral neural tube. Cell. 2000;101:435–445. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Gu X, Liu Y, Wang J, Wirt SE, Bottino R, Schorle H, Sage J, Kim SK. PDGF signalling controls age-dependent proliferation in pancreatic [bgr]-cells. Nature. 2011;478:349–355. doi: 10.1038/nature10502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collombat P, Hecksher-Sørensen J, Broccoli V, Krull J, Ponte I, Mundiger T, Smith J, Gruss P, Serup P, Mansouri A. The simultaneous loss of Arx and Pax4 genes promotes a somatostatin-producing cell fate specification at the expense of the alpha- and beta-cell lineages in the mouse endocrine pancreas. Development. 2005;132:2969–2980. doi: 10.1242/dev.01870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collombat P, Mansouri A, Hecksher-Sorensen J, Serup P, Krull J, Gradwohl G, Gruss P. Opposing actions of Arx and Pax4 in endocrine pancreas development. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2591–2603. doi: 10.1101/gad.269003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collombat P, Xu X, Ravassard P, Sosa-Pineda B, Dussaud S, Billestrup N, Madsen OD, Serup P, Heimberg H, Mansouri A. The Ectopic Expression of Pax4 in the Mouse Pancreas Converts Progenitor Cells into α and Subsequently β Cells. Cell. 2009;138:449–462. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH. The Regulatory Genome: Gene Regulatory Networks In Development and Evolution. Academic Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson EH. Emerging properties of animal gene regulatory networks. Nature. 2010;468:911–920. doi: 10.1038/nature09645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgraz R, Herrera PL. Pancreatic neurogenin 3-expressing cells are unipotent islet precursors. Development. 2009;136:3567–3574. doi: 10.1242/dev.039214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch G, Jung J, Zheng M, Lóra J, Zaret KS. A bipotential precursor population for pancreas and liver within the embryonic endoderm. Development. 2001;128:871–881. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhawan S, Georgia S, Tschen S, Fan G, Bhushan A. Pancreatic β Cell Identity Is Maintained by DNA Methylation-Mediated Repression of Arx. Developmental Cell. 2011;20:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorrell C, Schug J, Lin CF, Canaday PS, Fox AJ, Smirnova O, Bonnah R, Streeter PR, Stoeckert CJ, Jr, Kaestner KH, et al. Transcriptomes of the major human pancreatic cell types. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2832–44. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2283-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejarque M, Cervantes S, Pujadas G, Tutusaus A, Sanchez L, Gasa R. Neurogenin3 cooperates with Foxa2 to autoactivate its own expression. J Biol Chem. 2013 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.388173. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikura J, Hosoda K, Kawaguchi Y, Noguchi M, Iwakura H, Odori S, Mori E, Tomita T, Hirata M, Ebihara K, et al. Rbp-j regulates expansion of pancreatic epithelial cells and their differentiation into exocrine cells during mouse development. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2779–2791. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyer WR, Gu X, Liu Y, Bottino R, Crabtree GR, Kim SK. Neonatal β Cell Development in Mice and Humans Is Regulated by Calcineurin/NFAT. Developmental Cell. 2012;23:21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouzi M, Kim YH, Katsumoto K, Johansson K, Grapin-Botton A. Neurogenin3 initiates stepwise delamination of differentiating endocrine cells during pancreas development. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:589–604. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo T, Landsman L, Li N, Hebrok M. Factors Expressed by Murine Embryonic Pancreatic Mesenchyme Enhance Generation of Insulin-Producing Cells From hESCs. Diabetes. 2013 doi: 10.2337/db12-0167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hang Y, Stein R. MafA and MafB activity in pancreatic β cells. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison KA, Thaler J, Pfaff SL, Gu H, Kehrl JH. Pancreas dorsal lobe agenesis and abnormal islets of Langerhans in Hlxb9-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1999;23:71–75. doi: 10.1038/12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haumaitre C, Fabre M, Cormier S, Baumann C, Delezoide AL, Cereghini S. Severe pancreas hypoplasia and multicystic renal dysplasia in two human fetuses carrying novel HNF1beta/MODY5 mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2363–2375. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heit JJ, Apelqvist ÅA, Gu X, Winslow MM, Neilson JR, Crabtree GR, Kim SK. Calcineurin/NFAT signalling regulates pancreatic β-cell growth and function. Nature. 2006;443:345–349. doi: 10.1038/nature05097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter CS, Dixit S, Cohen T, Ediger B, Wilcox C, Ferreira M, Westphal H, Stein R, May CL. Islet α, β, and δ Cell Development Is Controlled by the Ldb1 Coregulator, Acting Primarily With the Islet-1 Transcription Factor. Diabetes. 2012;62:875–886. doi: 10.2337/db12-0952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iype T, Taylor DG, Ziesmann SM, Garmey JC, Watada H, Mirmira RG. The transcriptional repressor Nkx6.1 also functions as a deoxyribonucleic acid context-dependent transcriptional activator during pancreatic beta-cell differentiation: evidence for feedback activation of the nkx6.1 gene by Nkx6.1. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1363–1375. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen J, Pedersen EE, Galante P, Hald J, Heller RS, Ishibashi M, Kageyama R, Guillemot F, Serup P, Madsen OD. Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1. Nat Genet. 2000;24:36–44. doi: 10.1038/71657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Levine M. Binding affinities and cooperative interactions with bHLH activators delimit threshold responses to the dorsal gradient morphogen. Cell. 1993;72:741–752. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90402-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson KA, Dursun U, Jordan N, Gu G, Beermann F, Gradwohl G, Grapin-Botton A. Temporal Control of Neurogenin3 Activity in Pancreas Progenitors Reveals Competence Windows for the Generation of Different Endocrine Cell Types. Developmental Cell. 2007;12:457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DS, Mortazavi A, Myers RM, Wold B. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science. 2007;316:1497–502. doi: 10.1126/science.1141319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HS, Kim YS, ZeRuth G, Beak JY, Gerrish K, Kilic G, Sosa-Pineda B, Jensen J, Pierreux CE, Lemaigre FP, et al. Transcription factor Glis3, a novel critical player in the regulation of pancreatic beta-cell development and insulin gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:6366–6379. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01259-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klochendler A, Weinberg-Corem N, Moran M, Swisa A, Pochet N, Savova V, Vikeså J, Van de Peer Y, Brandeis M, Regev A, et al. A transgenic mouse marking live replicating cells reveals in vivo transcriptional program of proliferation. Dev Cell. 2012;23:681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopp JL, Dubois CL, Schaffer AE, Hao E, Shih HP, Seymour PA, Ma J, Sander M. Sox9+ ductal cells are multipotent progenitors throughout development but do not produce new endocrine cells in the normal or injured adult pancreas. Development. 2011;138:653–665. doi: 10.1242/dev.056499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordowich S, Collombat P, Mansouri A, Serup P. Arx and Nkx2.2 compound deficiency redirects pancreatic alpha- and beta-cell differentiation to a somatostatin/ghrelin co-expressing cell lineage. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lango Allen H, Flanagan SE, Shaw-Smith C, De Franco E, Akerman I, Caswell R, Ferrer J, Hattersley AT, Ellard S. GATA6 haploinsufficiency causes pancreatic agenesis in humans. Nat Genet. 2012;44:20–22. doi: 10.1038/ng.1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Arber S, Jessell TM, Edlund H. Selective agenesis of the dorsal pancreas in mice lacking homeobox gene Hlxb9. Nat Genet. 1999;23:67–70. doi: 10.1038/12669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Hunter CS, Du A, Ediger B, Walp E, Murray J, Stein R, May CL. Islet-1 regulates Arx transcription during pancreatic islet alpha-cell development. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15352–15360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.231670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn FC, Smith SB, Wilson ME, Yang KY, Nekrep N, German MS. Sox9 coordinates a transcriptional network in pancreatic progenitor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:10500–10505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704054104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyttle BM, Li J, Krishnamurthy M, Fellows F, Wheeler MB, Goodyer CG, Wang R. Transcription factor expression in the developing human fetal endocrine pancreas. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1169–1180. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magenheim J, Klein AM, Stanger BZ, Ashery-Padan R, Sosa-Pineda B, Gu G, Dor Y. Ngn3(+) endocrine progenitor cells control the fate and morphogenesis of pancreatic ductal epithelium. Dev Biol. 2011;359:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín M, Gallego-Llamas J, Ribes V, Kedinger M, Niederreither K, Chambon P, Dollé P, Gradwohl G. Dorsal pancreas agenesis in retinoic acid-deficient Raldh2 mutant mice. Dev Biol. 2005;284:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui T, Swift GH, Hale MA, Meredith DM, Johnson JE, MacDonald RJ. Transcriptional Autoregulation Controls Pancreatic Ptf1a Expression during Development and Adulthood. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:5458–5468. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00549-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald E, Li J, Krishnamurthy M, Fellows GF, Goodyer CG, Wang R. SOX9 regulates endocrine cell differentiation during human fetal pancreas development. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2012;44:72–83. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micallef SJ, Li X, Schiesser JV, Hirst CE, Yu QC, Lim SM, Nostro MC, Elliott DA, Sarangi F, Harrison LC, et al. INS(GFP/w) human embryonic stem cells facilitate isolation of in vitro derived insulin-producing cells. Diabetologia. 2012;55:694–706. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2379-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyatsuka T, Kosaka Y, Kim H, German MS. Neurogenin3 inhibits proliferation in endocrine progenitors by inducing Cdkn1a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:185–190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004842108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papatsenko D, Levine M. Quantitative analysis of binding motifs mediating diverse spatial readouts of the Dorsal gradient in the Drosophila embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4966–4971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409414102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papizan JB, Singer RA, Tschen SI, Dhawan S, Friel JM, Hipkens SB, Magnuson MA, Bhushan A, Sussel L. Nkx2.2 repressor complex regulates islet β-cell specification and prevents β-to-α-cell reprogramming. Genes Dev. 2011;25:2291–2305. doi: 10.1101/gad.173039.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri S, Hebrok M. Cellular Plasticity within the Pancreas— Lessons Learned from Development. Developmental Cell. 2010;18:342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece-Hoyes JS, Barutcu AR, McCord RP, Jeong JS, Jiang L, MacWilliams A, Yang X, Salehi-Ashtiani K, Hill DE, Blackshaw S, Zhu H, Dekker J, Walhout AJ. Yeast one-hybrid assays for gene-centered human gene regulatory network mapping. Nat Methods. 2011;8:1050–1052. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruder WC, Lu T, Collins JJ. Synthetic Biology Moving into the Clinic. Science. 2011;333:1248–1252. doi: 10.1126/science.1206843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer AE, Freude KK, Nelson SB, Sander M. Nkx6 Transcription Factors and Ptf1a Function as Antagonistic Lineage Determinants in Multipotent Pancreatic Progenitors. Developmental Cell. 2010;18:1022–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwitzgebel VM, Scheel DW, Conners JR, Kalamaras J, Lee JE, Anderson DJ, Sussel L, Johnson JD, German MS. Expression of neurogenin3 reveals an islet cell precursor population in the pancreas. Development. 2000;127:3533–3542. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.16.3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellick GS, Barker KT, Stolte-Dijkstra I, Fleischmann C, Coleman RJ, Garrett C, Gloyn AL, Edghill EL, Hattersley AT, Wellauer PK, et al. Mutations in PTF1A cause pancreatic and cerebellar agenesis. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1301–1305. doi: 10.1038/ng1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour PA, Freude KK, Tran MN, Mayes EE, Jensen J, Kist R, Scherer G, Sander M. SOX9 is required for maintenance of the pancreatic progenitor cell pool. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:1865–1870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour PA, Sander M. Historical Perspective: Beginnings of the β-Cell Current Perspectives in βCell Development. Diabetes. 2011;60:364–376. doi: 10.2337/db10-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Watada H, German MS. Neurogenin3 activates the islet differentiation program while repressing its own expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:142–149. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solar M, Cardalda C, Houbracken I, Martín M, Maestro MA, De Medts N, Xu X, Grau V, Heimberg H, Bouwens L, et al. Pancreatic Exocrine Duct Cells Give Rise to Insulin-Producing β Cells during Embryogenesis but Not after Birth. Developmental Cell. 2009;17:849–860. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger BZ, Tanaka AJ, Melton DA. Organ size is limited by the number of embryonic progenitor cells in the pancreas but not the liver. Nature. 2007;445:886–891. doi: 10.1038/nature05537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoffers DA, Zinkin NT, Stanojevic V, Clarke WL, Habener JF. Pancreatic agenesis attributable to a single nucleotide deletion in the human IPF1 gene coding sequence. Nat Genet. 1997;15:106–110. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talchai C, Xuan S, Lin HV, Sussel L, Accili D. Pancreatic β Cell Dedifferentiation as a Mechanism of Diabetic β Cell Failure. Cell. 2012;150:1223–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson N, Gésina E, Scheinert P, Bucher P, Grapin-Botton A. RNA Profiling and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-Sequencing Reveal that PTF1a Stabilizes Pancreas Progenitor Identity via the Control of MNX1/HLXB9 and a Network of Other Transcription Factors. Mol Cell Biol. 2012;32:1189–1199. doi: 10.1128/MCB.06318-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Hecksher-Sorensen J, Xu Y, Zhao A, Dor Y, Rosenberg L, Serup P, Gu G. Myt1 and Ngn3 form a feed-forward expression loop to promote endocrine islet cell differentiation. Dev Biol. 2008;317:531–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Yan J, Anderson DA, Xu Y, Kanal MC, Cao Z, Wright CVE, Gu G. Neurog3 gene dosage regulates allocation of endocrine and exocrine cell fates in the developing mouse pancreas. Dev Biol. 2010;339:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe PO, Kormish JD, Roper VT, Fujitani Y, Alston NI, Zaret KS, Wright CVE, Stein RW, Gannon M. Ptf1a Binds to and Activates Area III, a Highly Conserved Region of the Pdx1 Promoter That Mediates Early Pancreas-Wide Pdx1 Expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4093–4104. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01978-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CR, Cole PA, Meyers DJ, Kormish J, Dent S, Zaret KS. Chromatin “Prepattern” and Histone Modifiers in a Fate Choice for Liver and Pancreas. Science. 2011;332:963–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1202845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xuan S, Borok MJ, Decker KJ, Battle MA, Duncan SA, Hale MA, Macdonald RJ, Sussel L. Pancreas-specific deletion of mouse Gata4 and Gata6 causes pancreatic agenesis. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3516–3528. doi: 10.1172/JCI63352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YP, Thorel F, Boyer DF, Herrera PL, Wright CVE. Context-specific α-to-β-cell reprogramming by forced Pdx1 expression. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1680–1685. doi: 10.1101/gad.16875711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaret KS. Genetic programming of liver and pancreas progenitors: lessons for stem-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:329–340. doi: 10.1038/nrg2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Brown J, Kanarek A, Rajagopal J, Melton DA. In vivo reprogramming of adult pancreatic exocrine cells to beta-cells. Nature. 2008;455:627–632. doi: 10.1038/nature07314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Law AC, Rajagopal J, Anderson WJ, Gray PA, Melton DA. A multipotent progenitor domain guides pancreatic organogenesis. Dev Cell. 2007;13:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. List of interactions compiled to represent the gene regulatory networks of pancreas development.