Abstract

Viral infections of the central nervous system (CNS) are of increasing concern, especially among immunocompromised populations. Rodent models are often inappropriate for studies of CNS infection, as many viruses, including JC virus (JCV) and HIV, cannot replicate in rodent cells. Consequently, human fetal brain-derived multipotential CNS progenitor cells (NPCs) that can be differentiated into neurons, oligodendrocytes, or astrocytes have served as a model in CNS studies. NPCs can be nonproductively infected by JCV, while infection of progenitor-derived astrocytes (PDAs) is robust. We profiled cellular gene expression at multiple times during differentiation of NPCs to PDAs. Several activated transcription factors show commonality between cells of the brain, in which JCV replicates, and lymphocytes, in which JCV is likely latent. Bioinformatic analysis determined transcription factors that may influence the favorable transcriptional environment for JCV in PDAs. This study attempts to provide a framework for understanding the functional transcriptional profile necessary for productive JCV infection.

INTRODUCTION

Biochemical and molecular studies of JCV and other viral infections of the central nervous system (CNS) have long been impeded by the lack of appropriate animal or cell culture models of disease. A number of important human viruses, such as JC virus (JCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cannot replicate in rodent cells. The lack of viral replication in rodent cells highlights major differences between human CNS cells and model organisms used to study neural development. Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection of primate brains is possible for HIV studies and has been used to demonstrate viral latency in the CNS (1). Unfortunately, these models are expensive and often have high animal-to-animal variation in disease phenotype and disease progression. JCV, except in one unique case, does not productively replicate in nonhuman primate cells in the absence of T antigen expressed in trans and does not recapitulate human disease (2).

In order to overcome these limitations, a system utilizing human multipotential human CNS progenitor cells (NPCs) derived from 8-week-gestation fetal brain was developed. By selective addition of media containing either bovine serum or neuronal or oligodendrocyte growth factors, these cells can be differentiated into progenitor-derived astrocytes (PDAs), progenitor-derived neurons (PDNs), or progenitor-derived oligodendrocytes (PDOs) (3, 4). PDAs are highly susceptible to both HIV and JCV, which mimics the susceptibility of astrocytes to these viruses in vivo (3, 5–7). The differentiation of these progenitor-derived cells is highly reproducible, since the cultures are more homogeneous than primary CNS-derived cell cultures. This system provides a stable and renewable resource with which to study NPC differentiation and its effects on viral pathogenesis.

More recently, other culture models of human astrocyte development have been established. NPCs cultured from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) or embryonic stem cells (ESCs) allow the use of defined chemical media and patterning for distinct subtypes of astroglial progenitor cells to occur (8, 9). On the other hand, NPCs derived from human fetal brain (3, 10) develop in a more physiologically relevant context and are patterned in vivo during fetal development.

NPCs, PDNs, and PDAs have been used to study a number of viruses that cause infections of the CNS, including JCV (11), HIV (7), human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) (12), and xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus (XMRV) (13). PDAs have also been used to test potential therapies for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) (14). Interestingly, HIV and JCV are restricted in NPCs but replicate robustly in PDAs, while XMRV replicates in NPCs and is restricted in PDAs. HHV-6A replicates robustly in PDAs, while HHV-6B can infect PDAs but is more restricted in replication. Thus, NPCs and PDAs may be used to study cell type and viral differences that influence replication and pathology.

The focus of this study was to identify cellular factors that influence JCV transcription and determine how the cellular transcriptional environment changes in a way that favors robust JCV infection during differentiation of NPCs to PDAs. JCV is a human polyomavirus that is the etiological agent of the human brain demyelinating disease progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). Replication in cell culture is limited to human cells of macroglial origin (JCV and PML are extensively reviewed in reference 11). JCV can nonproductively infect NPCs. Upon serum-induced differentiation of infected progenitor cells to PDAs, JCV commences early gene expression, followed by DNA replication and late gene expression. Thus, measuring changes in gene expression during the course of astrocyte differentiation provides insight into factors required in the transcription and replication of JCV. We have used Affymetrix microarrays, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), immunofluorescence, and Western blotting (Fig. 1) to determine the expression of over 25,000 genes at multiple times during astrocyte differentiation from NPCs. Of these, expression of more than 3,000 annotated genes changed during 30 days of differentiation. RNA for transcription factors known to increase JCV susceptibility, particularly NFIX, was generally upregulated, while factors which decrease JCV permissiveness were generally downregulated. The increased definition of the transcriptional environment of this system will give greater insight into factors involved in JCV activation and can serve as a resource for other viral studies of NPC and astrocyte infection, as well as human astrocyte differentiation.

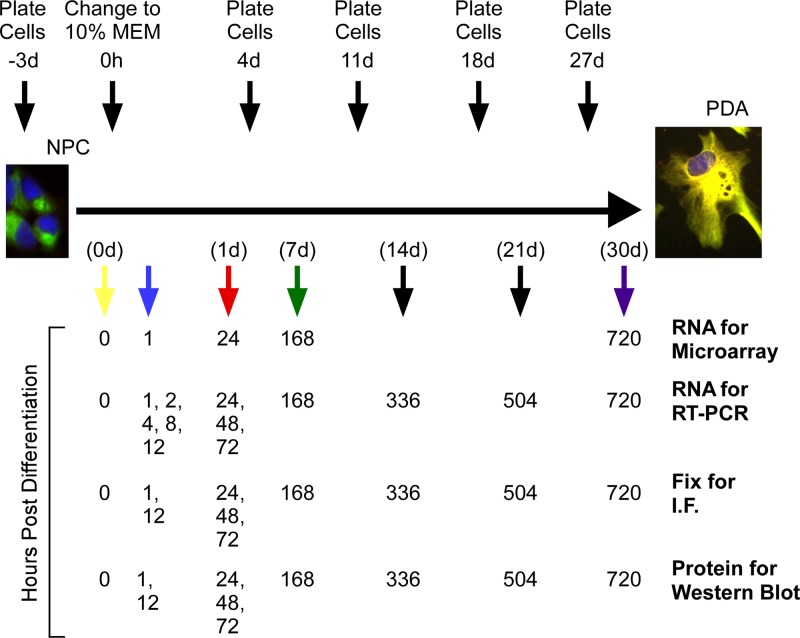

Fig 1.

Schematic of the gene expression experimental plan. Above the differentiation plot is information about timing of cell plating. Cells tested at the time points 0 to 3 days were plated 3 days prior to time zero. For all other time points, cells were plated 3 days before the time points. Below the differentiation line are the times of sample collection for each type of sample.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and differentiation.

The isolation and culture of multipotential human central nervous system progenitor cells have been described previously (3). Briefly, cells were grown as two-dimensional attached cultures on poly-d-lysine (PDL)-coated plasticware at 37°C in 5% CO2. Progenitor cells were grown in serum-free Neurobasal medium supplemented with N2 components, neural survival factor, 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, recombinant basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; 25 ng/ml; Peprotech), and recombinant epidermal growth factor (EGF; 20 ng/ml; Peprotech). To induce differentiation, progenitor growth medium was removed, cells were washed twice with 37°C phosphate-buffered saline, and PDA medium was added. PDAs were maintained in minimal essential medium (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine, and 50 mg/ml gentamicin. For differentiation experiments, cells were plated 3 to 4 days prior to isolation of RNA/protein. Cells tested at time points up to and including 3 days postdifferentiation were plated 3 days prior to differentiation. Cells tested at later time points were differentiated in flasks and plated 3 to 4 days prior to isolation of RNA/protein. Cells were plated at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well in 6-well plates for RNA isolation and plated on PDL-coated glass coverslips in 12-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well for immunofluorescence.

Viruses and antibodies.

In all experiments with viral infection of NPCs or PDAs, the JCV viral variant Mad-4 was used (15). The Mad-4 isolate of JCV was grown in PDAs and purified by cellular membrane disruption by 0.25% sodium deoxycholate (Sigma-Aldrich), followed by centrifugation and removal of the cellular debris. One hemagglutination unit (HAU) of Mad-4 virus contains approximately 1 × 104 infectious particles. Hemagglutination titers were expressed as the reciprocal of the final dilution resulting in hemagglutination of human type O erythrocytes. Owl-586 cells were isolated from an astrocytoma, are persistently infected with JCV, and produce infectious particles of the Mad-4 variant of JCV (2). Owl-586 cells are the only known nonhuman, nonchimpanzee primate cells that are productively infected with JCV. Primary antibodies were rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP; Millipore), mouse IgG1 anti-nestin (16), mouse IgG2a anti-βIII tubulin (Covance), mouse anti-SV40 T antigen (which binds JCV T antigen) (Calbiochem), and anti-VP1 (in house).

Immunofluorescence.

Uninfected human neural progenitor cells or differentiating PDAs were plated at a density of 5 × 104 on glass coverslips in 12-well dishes 3 days prior to differentiation. Owl-586 cells and PDAs (21 days postdifferentiation) were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well onto glass coverslips in 6-well plates. The day after, PDAs were exposed to 200 HAU of JCV per 1 × 106 cells. Uninfected differentiating cells, infected PDAs (four or 12 days after JCV infection), and Owl-586 cells (5 days after seeding) were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% PFA for 15 min at RT, washed, and permeabilized either with 0.2% Triton X-100 (uninfected cells) or at −20°C in 70% ethanol (infected cells for 15 min). Primary antibodies were as noted above. Alexafluor secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used at 1 to 2 mg/ml for indirect immunofluorescence. Coverslips were mounted on glass slides using Prolong Gold with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Invitrogen). Labeled cells were visualized using an Axiovert 200M fluorescence microscope (Zeiss).

Immunoblotting.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared as described previously (17) or by direct extraction in 2× SDS loading dye with 100 mM dithiothreitol. Equal amounts of protein were separated by electrophoresis on a 4 to 12% bis-Tris gel, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes, and blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline–0.5% Tween 20 (TBS-T). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in TBS-T for 3 h, washed with TBS-T, and incubated with secondary fluorescent label-conjugated antibodies (Invitrogen). Blots were visualized using a Fluorchem Q imager (Alpha Innotech). To quantify, GFAP levels were first normalized to GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase). Levels of NPCs (i.e., 0 h) were set to 1, and all ratios were normalized to that at time zero.

RNA isolation.

Cells were collected with Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) and then extracted with chloroform and ethanol. RNA was isolated in H2O using Qiagen RNeasy columns according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples used for RT-PCR were DNase treated (Ambion Turbo DNA free kit) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA concentration was determined on a Nanodrop ND-8000 8-sample spectrophotometer.

RT-PCR.

RNA was reverse transcribed with an Applied Biosystems kit using oligo(dT) primers. cDNA and no-RT controls were assayed in triplicate with TaqMan primer/probe sets for genes of interest (FAM) and primer-limited VIC-labeled β-actin (see Table S4 in the supplemental material) on an Applied Biosystems ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system. Average cycle threshold (CT) values were log transformed, mean centered, and autoscaled in order to draw statistical comparisons (18). The RT-PCR data are from three biological replicates. Error bars in the figures indicate 95% confidence intervals, and asterisks indicate Welch-modified t test P values of less than 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001.

Microarray processing and analysis.

Samples were prepared according to Affymetrix protocols (Affymetrix, Inc.). RNA quality and quantity were ensured using Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Inc.) and NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific, Inc.), respectively. For RNA labeling, 200 ng total RNA was used in conjunction with the Affymetrix-recommended protocol for the GeneChip Human 1.0 ST array (Affymetrix, Inc.). Labeled cDNA was hybridized, washed, and stained to separate Affymetrix GeneChip 1.0 ST human gene arrays by sample according to the protocols described by Affymetrix (Affymetrix, Inc.). For staining, streptavidin phycoerythrin solution was used (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA) and enhanced by an antibody solution containing 0.5 mg/ml of biotinylated anti-streptavidin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). An Affymetrix GeneChip scanner 3000 was used to scan each Affymetrix GeneChip 1.0 ST human gene array. After scanning, gene probe intensities were generated using Affymetrix AGCC software (Affymetrix, Inc.). The Affymetrix expression console (Affymetrix, Inc.) was subsequently used to summarize the gene probe intensities and provided 33,297 RMA (robust multichip average)-normalized gene fragment expression values per sample.

Microarray data analysis.

Analysis was done in R (http://cran.r-project.org/). Data quality was first inspected and ensured via sample-level Tukey box plot, covariance-based principal component analysis (PCA) scatter plot, and correlation-based heat map using the “box.plot(),” “princomp(),” “cor(),” and “image()”functions. Afterward, gene fragments not having at least one expression value greater then system noise were deemed noise-biased and discarded. System noise was defined as the expression value across experiment groups at which the observed CV (coefficient of variation) grossly deviated from linearity. For gene fragments not discarded, expression values were floored to equal system noise if they were less than system noise and then subjected to a one-factor ANOVA (analysis of variance) test under the BH (Benjamini and Hochberg) FDR (false discovery rate) MCC (multiple comparison correction) condition using time as the factor. For gene fragments having a corrected P value of <0.05 only, the Tukey HSD (honestly significant difference) test was applied, and the fold change between all possible group means was calculated. Gene fragments having both a Tukey HSD P value of <0.05 and a change of ≥1.5-fold for a pairwise group comparison were flagged as having expression that was significantly different for that comparison. Subsequent annotation for each gene fragment flagged was obtained using Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA; Ingenuity Systems). Subsequent inspection of those genes flagged by heat mapping was accomplished using the “heatmap.2()” function.

Transcription factor binding motif analysis.

Promoter sequences for the 10 continuously upregulated genes were downloaded using the Transcriptional Regulatory Element Database (http://rulai.cshl.edu/cgi-bin/TRED/tred.cgi?process=home) on 20 October 2012. The best sequence available was chosen for each promoter from −700 to + 299 bp from the known curated transcriptional start sites. The sequences of these promoters and the Mad-4 variant of the JCV regulatory region were uploaded to the PROMO website for transcription factor binding site (TFBS) identification using the MultiSearchSites tool (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3). Only human factors and human sites were selected. PROMO uses position weight matrices based on known binding sites found in the TRANSFAC database (version 8.3) to identify putative TFBSs (19, 20). Only sites found in 100% of sequences were selected.

Upstream regulator activation analysis.

Fold change data from Table S1 in the supplemental material were analyzed through the use of IPA (Ingenuity Systems). A change of 1.5-fold was used as a cutoff value. The analysis for each time point during differentiation can be found in Table S3 in the supplemental material. Upstream regulators with a P value of overlap of 0.01 or less and an activation z-score of ≥2.0 or of −2.0 or less were considered activated or inhibited. An explanation can be found above. A description of IPA can be found in references 21 and 22.

Microarray data accession number.

Microarray data obtained here can be accessed at NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), accession number GSE43794.

RESULTS

Morphology and marker protein expression change rapidly upon serum-induced differentiation of NPCs to PDAs.

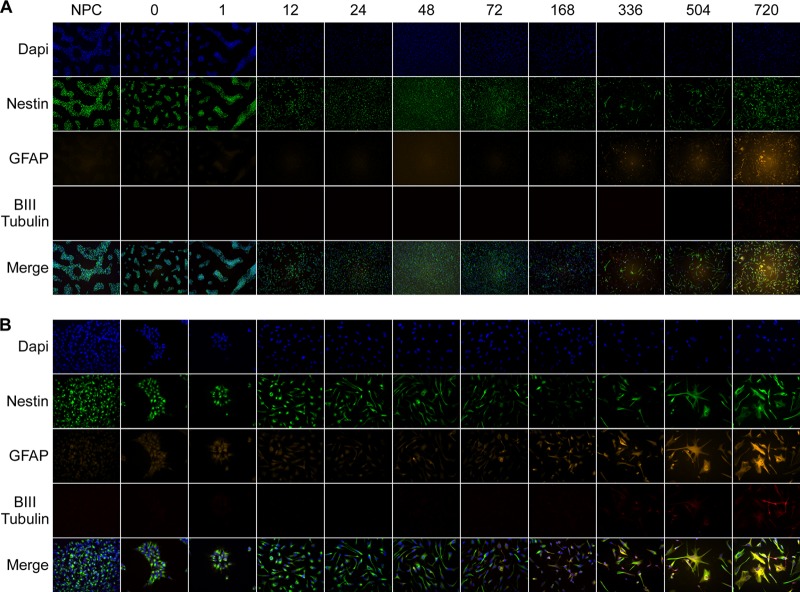

NPCs harvested from fetal brain neurospheres can form monolayers when grown in progenitor media, and these monolayers can differentiate into all three types of neural cells (3, 4). Removal of NPC growth factors and addition of serum induce differentiation of NPCs to PDAs. A rapid change in morphology was observed upon serum addition (see Video S1 in the supplemental material). By 1 h after serum induction, growth could be seen in the characteristic clustering of progenitor cells (Fig. 2), and by 12 h, the clustering pattern of NPCs had changed to a more even and homogeneous cellular distribution. The astrocyte marker GFAP could be detected by immunofluorescence by approximately 2 to 3 days postdifferentiation. Approximately 1 week after serum induction, the homogeneous culture of NPCs became more heterogeneous, as some cells began to look like characteristic astrocytes and express GFAP, while others remained small and progenitor-like, without expressing GFAP. After several days of differentiation, phagocytosis could be observed (see Video S1), a characteristic of astrocytes and glial precursors (23, 24). Nestin expression remained in the majority of cells for the entire differentiation process. At 30 days postdifferentiation, a small number of cells expressed the neuronal marker βII-tubulin. Almost all cells that express βII-tubulin coexpress GFAP, indicating that these may be remaining multipotential cells (25). By 30 days after serum induction, more than 90% of cells expressed GFAP and had an astrocytic morphology. Additionally, these astrocytes have the ability to take up glutamate (7).

Fig 2.

Multipotent neural progenitor cells change morphology, size, and marker expression during differentiation to astrocytes. Cells were stained with primary antibodies for nestin, GFAP, and βIII-tubulin and Alexafluor fluorescent secondary antibodies. Samples were mounted with Prolong Gold (Invitrogen) containing the DNA dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and analyzed by fluorescence microscopy using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope. Magnification, ×10 (A) and ×40 (B). NPC and time zero panels show various passage numbers and levels of confluence of NPCs. Numbers above the panels indicate hours postdifferentiation.

Transcriptional changes during differentiation are rapid and occur in at least two distinct phases.

Because NPCs and PDAs have been used for viral studies in numerous stages between NPC and fully differentiated astrocyte, we determined gene expression levels at a number of times during differentiation of NPCs to PDAs. We used Affymetrix microarrays to measure gene expression before differentiation and at 1 h, 24 h (1 day), 168 h (7 days), and 720 h (30 days) after serum-induced differentiation (Fig. 1).

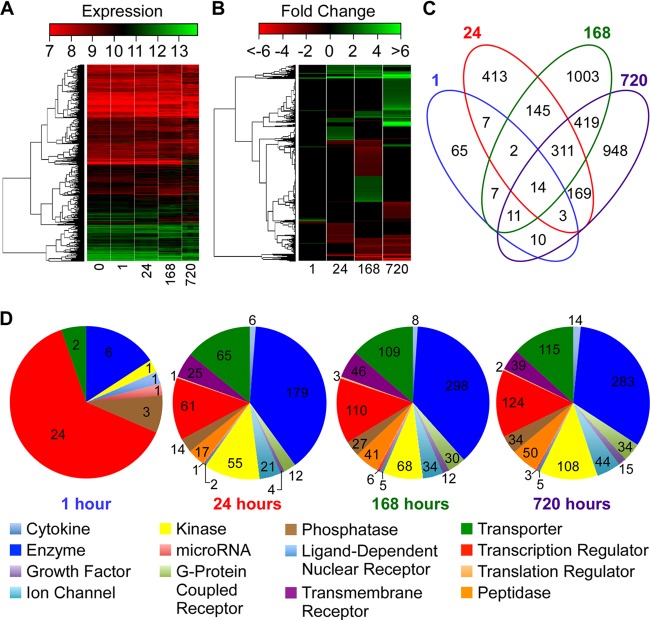

An analysis of changes in gene expression indicates that there are at least 7 major groups of genes that share similar temporal regulation, as well as a number of minor groups and subgroups (Fig. 3A and B). The largest group of genes is differentially regulated only at 30 days (Fig. 3C). Similar to in vivo differentiation, some genes change expression during differentiation and then return to the levels found in progenitor cells.

Fig 3.

Global gene expression patterns during astrocyte differentiation. RNA was collected at 0 h (0 h), 1 h (1 h), 24 h (1 day), 168 h (7 days) and 720 h (30 days) postdifferentiation and analyzed by microarray analysis as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Clustered heat map depicting RMA-normalized expression levels (log2) for 3,527 gene probes, representing 2,848 genes, identified as being significantly dysregulated during differentiation from NPCs to PDAs. (B) Clustered heat map of mean expression differences (i.e., fold change) between 0 h and 1 h, 24 h, 168 h, or 720 h for the 3,527 gene probes. (C) Venn diagram depicting the number of gene probes observed dysregulated between 0 h and 1 h, 24 h, 168 h, and 720 h. (D) Pie charts depicting the number of annotated genes dysregulated between 0 h and 1 h, 24 h, 168 h, and 720 h versus type. Those annotated as “other” are not represented.

During the first hour of differentiation, 119 gene probes are significantly differentially regulated in relation to NPCs. Of these, 74 have annotated gene descriptions in the IPA database. The majority are transcriptional regulators (Fig. 3C), indicating that the first wave of transcription in response to growth factor removal and serum addition initiates a transcriptional cascade, by first regulating transcription factors and genes that interact with transcription factors (e.g., inhibitor of DNA binding 1, 2, and 3 [ID1, ID2, and ID3]). At 24 h postdifferentiation and beyond, genes encoding enzymes make up the largest plurality of gene expression changes, with genes for transcriptional regulators, kinases, and transporters making up the next largest groups of changing genes.

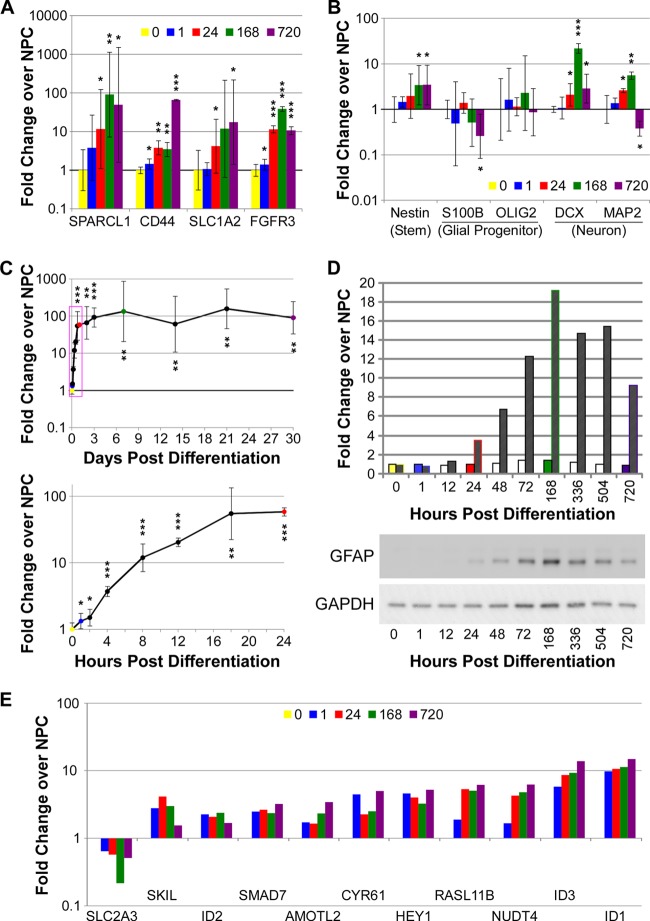

Astrocyte marker RNA expression is upregulated almost immediately after serum-induced differentiation.

NPCs do not express protein markers of glia or neurons. However, RNA of markers of stem cells, glial progenitors, neuronal cells, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes are all expressed in NPCs and differentiated PDAs. GFAP RNA is present at intermediate levels in progenitor cells, but protein is undetectable until 24 to 48 h postdifferentiation. RNA for the CNS stem cell marker nestin, the glial progenitor markers S100β and OLIG2, and the neuronal markers DCX and MAP2 are all expressed in glial progenitors (Fig. 4B). Thus, it appears that NPCs are primed to differentiate rapidly into any type of neural cell upon receiving signals for differentiation.

Fig 4.

Expression of RNA and protein markers during differentiation. (A) RT-PCR analysis of genes described as astrocyte markers, compared to neural progenitor cells (i.e., time zero). Numbers indicate hours postdifferentiation. Relative gene expression was determined compared to NPC expression (time zero) and normalized to β-actin expression. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). (B) RT-PCR analysis of change in gene expression, described as neural stem cell, glial progenitor, or neuronal markers, compared to neural progenitor cells (i.e., time zero). Relative gene expression was determined as for panel A. (C) Expression of GFAP RNA determined by RT-PCR. RNA was collected at the times depicted in Fig. 1. Relative gene expression was determined as for panel A. The red box indicated the region of expression expanded in the lower graph. (D) GFAP protein is upregulated during differentiation toward astrocytes. Protein was collected at the indicated hours and days during differentiation and visualized by Western blotting using Fluorchem Q software to analyze relative protein expression levels. Solid bars indicate relative GAPDH levels to time zero and indicate equal protein loading. Hatched bars indicate GFAP levels normalized to GAPDH levels and to levels in NPCs. (E) Microarray analysis of fold change in expression of genes continuously differentially regulated by 1 h postdifferentiation, normalized to expression in NPCs (i.e., time zero).

GFAP expression increased over 5-fold by 24 h postdifferentiation and remained elevated throughout astrocyte differentiation by microarray analysis. By more sensitive RT-PCR, GFAP expression was upregulated more than 3-fold by 4 h postdifferentiation and increased exponentially until after 18 h postdifferentiation (Fig. 4C). Levels of GFAP RNA then remained upregulated in the range of 100-fold compared to NPCs. Protein expression was detectable by 24 h postdifferentiation, peaked approximately 7 days postdifferentiation (Fig. 4D), and remained upregulated throughout the time course. As determined by RT-PCR, expression of SLC1A2 (EAAT2/Glt-1), the major astroglial glutamate transporter, increased over 4-fold by 24 h and continued to increase throughout differentiation. RNA expression of SLC1A3 (EAAT1), another astrocyte glutamate transporter, was high in NPCs and remained high upon differentiation (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). RNA for the CD44 gene, a marker of astrocyte-restricted precursor cells, was expressed at low levels in NPCs but increased significantly by 168 h (Fig. 4A).

The data may indicate that in vitro differentiation of NPCs to PDAs does not result in fully terminally differentiated astrocytes. Evidence is mounting that astrocytes in vivo which appear to be terminally differentiated and lineage restricted may also serve as immature cell populations. For example, SPARCL1, a protein highly expressed in radial glial cells (26), was upregulated approximately 10-fold at 24 h after serum addition and was almost 100-fold upregulated by RT-PCR at 168 and 720 h after serum addition. Additionally, the neuronal precursor marker doublecortin (DCX) was also upregulated at 168 and 720 h (Fig. 4B), and some cells coexpressed GFAP and the neuronal marker βIII-tubulin after 30 days (Fig. 2). Radial glial cells and other GFAP-positive cells can further differentiate into adult neural precursors (27), and midgestational fetal astrocytes can coexpress βII-tubulin and GFAP (25). Thus, as human NPCs differentiate in serum toward PDAs, they remain multipotential.

Continuously upregulated genes share common promoter transcription factor binding sites with the JC virus noncoding control region.

Microarray data showed that 10 annotated genes were immediately and continuously upregulated more than 1.5-fold, while only one—SLC2A3 (GLUT3), a neuron-specific glucose transporter—was immediately and continuously downregulated (Fig. 4E). Expression changes of SMAD7, SKIL, HEY1, ID1, ID2, and ID3 were confirmed by RT-PCR (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). We hypothesized that these genes would be coregulated and therefore share significant homology in the promoter regions. Using ClustalW (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2), we were unable to find significant regions of alignment (data not shown).

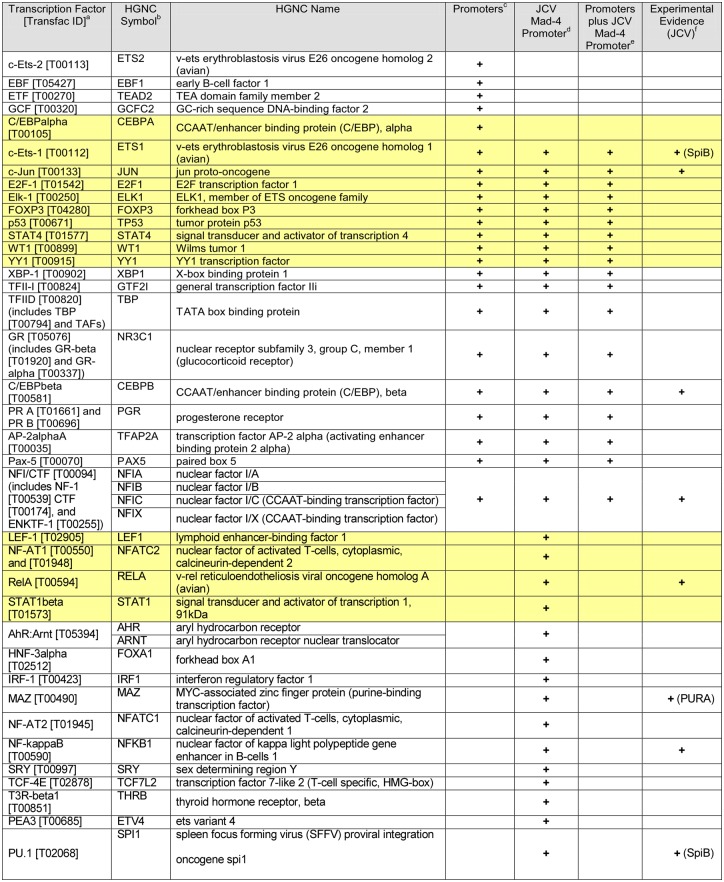

Despite their lack of alignment, the promoters of these genes share a number of transcription factor binding motifs. PROMO is a web-based program which accesses the TRANSFAC database of transcription factor binding motifs and constructs a weighted matrix to search for potential transcription factor binding sites in a given DNA sequence or across multiple DNA sequences (19, 20). Using PROMO, we analyzed the promoters of the 10 continuously upregulated genes (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Twenty-three unique factors from the TRANSFAC database were predicted to bind 100% of the promoters with a dissimilarity score of less than 15% (Table 1; also, see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Several binding sites found in the analysis, including those for NFI/CTF, JUN (AP-1), ETS1 (which shares the same binding site as SPIB), MAZ (which binds sequences similar to those bound by PURα), and C/EBPβ, are also known binding sites on the JCV promoter (also called the noncoding control region), so we included the JCV Mad-4 variant promoter in the analysis of common transcription factor binding sites. Eighteen unique factors were predicted to bind 100% of the promoters as well as the Mad-4 promoter with a dissimilarity score of less than 15% (Table 1; also, see Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Table 1.

Predicted transcription factor binding sitesg

a Common name and Transfac ID of putative binding transcription factors.

b HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) symbol for transcription factor genes.

c Transcription factors that bind all 10 immediately and continuously upregulated promoters.

d Transcription factors that bind the promoter of the Mad-4 variant of JCV.

e Transcription factors that bind all 10 human promoters, as well as the Mad-4 promoter.

f Transcription factors for which there is experimental evidence of binding to the JCV promoter.

Yellow boxes contain factors that were also determined by Ingenuity upstream regulator analysis to be either activated or inhibited (see Table 2, yellow box).

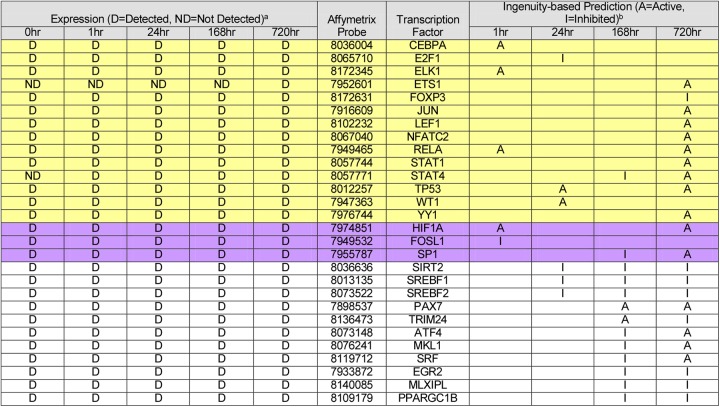

Several of these factors overlapped with predicted activated or inhibited factors from Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) (Tables 1 and 2, yellow). IPA uses gene expression data to predict the activity of upstream factors known to influence gene expression. Transcriptional regulator activity is calculated by determining the number and intensity of known regulated genes, their agreement with the literature, and the statistical likelihood that genes regulated by a transcription factor could be coexpressed by chance. The result of this analysis is a z-score. The magnitude of the z-score is the degree to which a factor is activated or inhibited. Positive z-scores indicate activated factors, while negative scores indicate that a factor is inhibited. Table 2 is a curated table of the IPA (full results are available in Table S3 in the supplemental material) and lists activated and inhibited transcriptional regulators that potentially bind the promoters of all 10 continuously upregulated genes (yellow), those that potentially bind the JCV Mad-4 promoter (violet), and those determined to be activated or inhibited at both 168 and 720 h (7 and 30 days) postdifferentiation (unshaded). Of the 33 transcription factors found to potentially bind the Mad-4 promoter, 14 are predicted to be activated or inhibited during the course of PDA differentiation. An additional two known regulators of JCV (HIF1α and SP1) as well as FOSL1, which is an Ap-1 protein, are also predicted to be either activated or inhibited during PDA differentiation. These analyses confirm known transcription factors responsible for JCV regulation, as well as identifying potentially important factors that were previously unknown.

Table 2.

Predicted activities of transcription regulatorsc

a Gene expression was determined by microarray analysis at the indicated time points.

b Transcription factor activity was determined by IPA at the indicated time points and compared to that of NPCs.

Yellow box, transcriptional regulators that may bind the promoters of the 10 immediately and continuously upregulated genes (see Table 1); violet box, transcriptional regulators related to those known to bind the JCV promoter; unshaded box, transcriptional regulators consistently activated or inhibited at both 168 h and 720 h postdifferentiation.

Transcription factors known to bind the JCV promoter are differentially regulated during astrocyte differentiation.

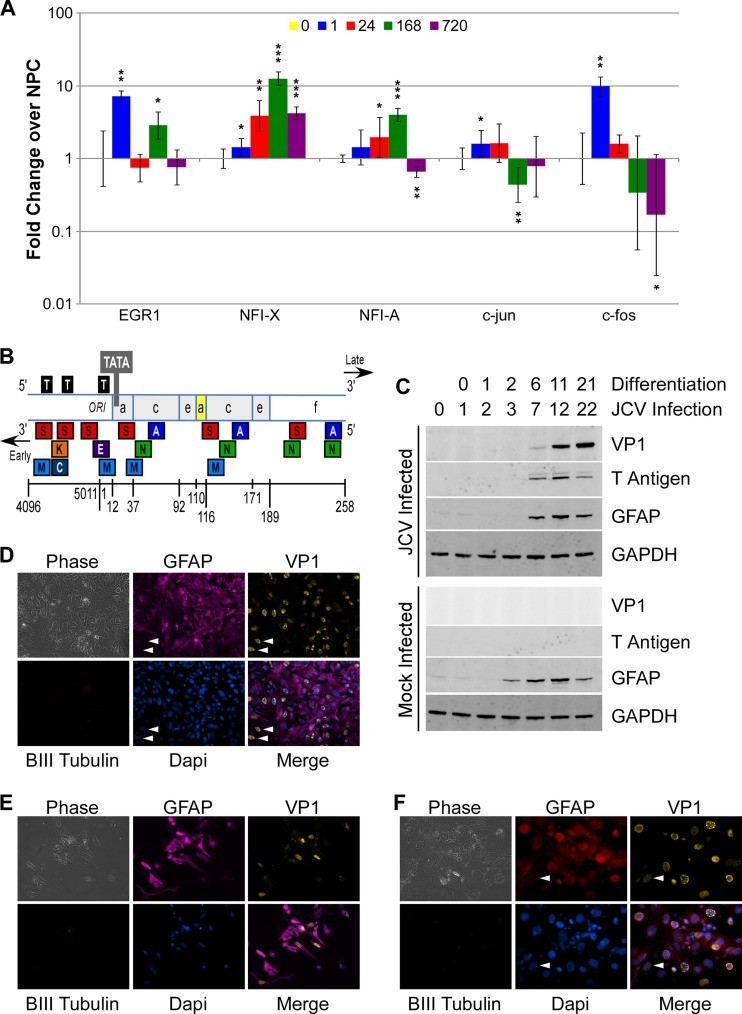

A number of transcriptional regulators are known to interact with the JCV promoter and affect transcriptional activation. Of these, 5 were significantly differentially expressed during the course of astrocyte differentiation, as determined by microarray. The expression changes of these genes were confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 5A).

Fig 5.

Changes induced during differentiation make astrocytes more susceptible to JCV transcription and replication. (A) Uninfected NPCs were differentiated and gene expression assayed by RT-PCR. Relative gene expression was determined as for Fig. 3A. (B) Schematic of the JCV Mad-4 variant noncoding control region showing the origin of DNA replication (ORI), direct tandem repeats of DNA sequence blocks a, c, and e, and a nonrepeated DNA sequence block, block f. The late-proximal block, block a (shaded yellow), contains a 19-bp deletion. Viral T antigen binding sites (black box labeled “T”) and the TATA box are also shown. Experimentally determined binding sites for EGR1 (E), NFIX (N), FOS (A), JUN (A), NFIA (N), SpiB/ETS1/Spi1 (S), NF-ΚB/RELA (K), MAZ/PURA (M), and CEBPβ (C) are shown. (C) NPCs were infected with JCV and differentiated as described in Materials and Methods. Protein was collected at the indicated days, and visualized by Western blot with a Fluorchem Q imager. (D to F) GFAP expression is highly correlated with, but not absolutely required for, productive viral infection. White arrowheads indicate cells expressing VP1 but not GFAP. Cells were seeded onto glass coverslips exposed to JCV, stained for expression of GFAP, βIII-tubulin, and VP1, and imaged with a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope at a ×20 magnification. Images were overlaid with Adobe Photoshop software. (D) PDAs 4 days postinfection; (E) PDAs 12 days postinfection; (F) Owl-586 cells.

Early growth response-1 protein (EGR1) activates late transcription from the JCV promoter (28). During differentiation of NPCs to PDAs, it is upregulated at 1 h postdifferentiation but downregulated thereafter. JCV may overcome this downregulation by inducing expression of EGR1 during infection (28). NFIX also activates JCV transcription (3, 17) and is upregulated in PDAs by 168 h (7 days) postdifferentiation. The AP-1 transcription factors FOS and JUN negatively regulate JCV (29, 30), as does NFIA (31). All three are downregulated during differentiation to PDAs, although NFIA is slightly upregulated prior to being downregulated. Thus, expression of factors known to activate JCV are generally upregulated during differentiation, while those known to inhibit JCV transcription are downregulated.

Changes in transcriptional regulation during differentiation result in increased JCV gene expression.

NPCs were infected by JCV. One day following infection, differentiation was induced. JCV large T antigen protein was detectable at the same time as GFAP, by 6 days postdifferentiation, while there was minimal expression of the late viral structural protein VP1. By 11 days postdifferentiation, VP1 was highly expressed, indicating that differentiation to astrocytes allowed JCV to complete its life cycle. Interestingly, infection of NPCs with JCV seemed to delay differentiation, as seen by GFAP expression. Mock-infected NPCs expressed detectable GFAP protein by 2 days postdifferentiation, while GFAP expression was not detectable until later in infected cells.

GFAP expression is highly correlated with, but not required for, JCV gene expression and replication in PDA cultures.

Evidence indicates that transcription factor availability and activation are the key determinants of JCV gene expression in neural-derived cells. Thus, GFAP expression may serve as a proxy marker for a transcriptional environment conducive to productive JCV infection. Almost all PDAs that are productively infected by JCV, as indicated by detection of the late viral capsid protein VP1, also express GFAP. The small percentage of GFAP-negative cells that express VP1, however, demonstrate that GFAP expression is neither an absolutely necessary nor sufficient condition for productive JCV infection. This is true in vivo, as well, as the primary target of JCV infection is oligodendrocytes, which do not express GFAP. Cells that do not express GFAP can also be infected with JCV, as demonstrated by the ability of JCV to infect NPCs (Fig. 5C). Although the percentage of GFAP− cells expressing VP1 is very low, de novo expression of VP1 can also be detected in some cells that do not produce GFAP, as demonstrated previously (3), and in PDAs 4 days postinfection (Fig. 5D, white arrowheads) and 12 days postinfection (Fig. 5E).

This can be seen in another model system as well. Normally, nonhuman primates inoculated with JCV exhibit nonproductive infection that develops into tumors of astroglial origin. In a unique case, however, the astrocytoma cells of the owl monkey line Owl-586 produced infectious virus from a culture suspension containing both integrated and free viral DNA (2). As in PDAs, most VP1 protein expression is found in GFAP-expressing cells, while some VP1-expressing cells are GFAP− (Fig. 5F, white arrowheads).

DISCUSSION

The culture model used in this study offers several advantages over models utilizing differentiating neurospheres. The two-dimensional progenitor culture is homogeneous in its access to media and growth factors (there are no cells inside neurospheres). Monolayers also allow greater access by viruses during infection and greater resolution during imaging. NPCs are homogeneous in morphology and marker expression. The homogeneous starting point of the NPC culture, followed by temporally heterogeneous differentiation toward astrocyte and potentially astrocytic neuronal stem cell lineages, can also offer a number of advantages to researchers. Future studies may combine viral infection of NPCs, differentiation, and fluorescence-activated cell sorting to more fully elucidate links between marker protein expression and viral and cellular gene expression, potentially leading to biomarkers for PML.

As progenitor cells differentiate toward astrocytes, quiescent JCV in infected progenitor cells is activated and begins to produce viral proteins. This system is highly reproducible and allows the study of factors that affect JCV transcription and replication. During the course of differentiation, cells begin to express GFAP, as well as other astrocyte markers, and change morphology. Additionally, RNA of several known activators (EGR1, NFIX) of JCV is upregulated and repressors (NFIA, JUN, and FOS) are downregulated.

Our overarching goal is to fully elucidate the transcriptional profile of cells permissive to JCV transcription and replication, as it differs from the profile of those that do not support robust JCV infection. The use of multiple time points during the course of differentiation allowed analysis of the transcriptional cascade of differentiation and bioinformatic analysis of genes that were continuously regulated upon differentiation, as well as determination of activated or inhibited transcriptional regulators. In the first hour after differentiation, the majority of differentially regulated genes are transcription regulators. These changes promote a transcriptional environment that favors JCV transcription, protein expression, and DNA replication.

Ten genes are immediately upregulated and remain so for the entire course of differentiation. Analysis of their proximal promoters and the JCV promoter identified 18 conserved potential transcription factor binding sites. Not all factors that have been experimentally determined to bind the Mad-4 promoter were found by PROMO analysis. Bioinformatics, while powerful, remains in its infancy and will improve as algorithms are refined and more data are incorporated into databases. These tools, however, offer a model to determine transcriptional activation in a more physiologically relevant context than ever before.

Analysis of transcription regulator activation yielded several important patterns that are supported by previous studies and point to new factors important for JCV transcription and replication. Factors of major interest include the NFI family of transcriptional regulators, the AP-1 and ETS proteins, and the WNT pathway transcription factor LEF1.

The NFI factors are a family of four proteins (NFI-A, -B, -C, and -X) with substantial homology encoded by distinct genes which have been extensively documented in neural development in mice (32) and in the transcription and replication of JCV in culture. All 10 continuously upregulated promoters, as well as the JCV promoter, contain NFI binding sites. NFIX is significantly upregulated almost immediately upon PDA differentiation, and NFIA is slightly upregulated and then downregulated during differentiation. Overexpression of NFIX alone is sufficient to cause nonproductive cells to become more permissive to JCV replication (3, 11, 17, 33), while knockdown of NFIA is also sufficient to increase JCV permissiveness (31). Unfortunately, the literature, and thus the IPA database, partially due to a lack of specific anti-NFI antibodies, has limited information on NFI-interacting proteins and NFI-mediated activation or repression of genes, so the IPA upstream regulation algorithm does not indicate NFI protein inhibition or activation.

Previously, the promoters of a number of neural genes and the regulatory region of JCV were shown to contain juxtaposed NFI and AP-1 binding elements (34). These proteins may compete for binding sites in these genes, providing a means for regulation of expression. All 10 upregulated promoters in the present study also contain both NFI and AP-1 binding sites. The AP-1 proteins FOS and JUN have been shown to downregulate JCV expression, particularly late expression, in the presence of viral T antigen (29, 30) and are downregulated during differentiation.

JUN and FOS also interact with many of the other factors that potentially bind the JCV promoter, such as WT1 (35) and the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) (36). UBC9, which interacts with JUN, also interacts with GR (37), ETS1 (38), and EGR2 (39). ETS1 is an important factor in B cell differentiation. SPIB, another important factor in B cell differentiation and maturation (40), also may interact with JUN (41) and has been shown to regulate JCV transcription (42). SPIB, like NFIX, can confer JCV susceptibility to nonpermissive cells when overexpressed (33). Lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1) is expressed in pre-B cells and is required for proper B cell differentiation (43). SMAD proteins, AP-1 proteins, and LEF1 also interact with each other (44–46) and with RUNX1 (47–49), which is also important in hematopoietic stem cell differentiation (49).

Other known activators of JCV transcription include TGF-β (50), which is known to activate SMAD DNA-binding proteins (51). SMAD proteins interact directly and functionally with AP-1 proteins (46). Many of these genes, including those encoding TGF-β and several SMADs (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), were also greatly upregulated over the course of differentiation. MEK1/2 inhibitors have been shown to block JCV multiplication (50), further implicating AP-1 proteins in JCV replication. Transcription factor networks at each time point (see Table S3 in the supplemental material) are depicted in Fig. S2 in the supplemental material.

These interactions and activation patterns, as well as the presence of binding sites for these proteins, further highlight the connections between lymphocytes, where JCV is likely to be latent, and astrocytes, where JCV establishes a lytic infection. This is just a small sample of the known interactions between the transcription regulators that change activation state during PDA differentiation. The JCV promoter likely utilizes previously established transcription factor networks that are activated during PDA differentiation. JCV has an extremely limited host range that is directly related to molecular factors that affect transcription and replication. Integration of signaling pathways for TGF-β/SMAD, Wnt, MAPK, and NFI transcription factors appears to promote JCV susceptibility of differentiating astrocytes.

Bioinformatic analysis of gene expression during astrocyte differentiation points to several potential target genes which may affect JCV expression. Further work is needed to confirm any potential interactions, but this gene expression data set, in concert with sequence information, may serve as a resource for discovery of factors important for the life cycle of neurotropic viruses, including JCV and HIV.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

RNA extractions, sample processing, and initial analysis of DNA microarrays were performed by Abdel Elkahloun and Weiwei Wu of the Microarray Core Facility of the National Human Genome Institute.

M.W.F. was supported in part by the Intramural AIDS Research Fellowship from the NIH Office of AIDS Research. The Laboratory of Molecular Medicine and Neuroscience and Bioinformatics Section are supported by the Division of Intramural Research of the NINDS.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 March 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00396-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Clements JE, Babas T, Mankowski JL, Suryanarayana K, Piatak M, Jr, Tarwater PM, Lifson JD, Zink MC. 2002. The central nervous system as a reservoir for simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV): steady-state levels of SIV DNA in brain from acute through asymptomatic infection. J. Infect. Dis. 186:905–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Major EO, Vacante DA, Traub RG, London WT, Sever JL. 1987. Owl monkey astrocytoma cells in culture spontaneously produce infectious JC virus which demonstrates altered biological properties. J. Virol. 61:1435–1441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Messam CA, Hou J, Gronostajski RM, Major EO. 2003. Lineage pathway of human brain progenitor cells identified by JC virus susceptibility. Ann. Neurol. 53:636–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Monaco MC, Maric D, Bandeian A, Leibovitch E, Yang W, Major EO. 2012. Progenitor-derived oligodendrocyte culture system from human fetal brain. J. Vis. Exp. 70:4274 doi:10.3791/4274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Churchill MJ, Wesselingh SL, Cowley D, Pardo CA, McArthur JC, Brew BJ, Gorry PR. 2009. Extensive astrocyte infection is prominent in human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia. Ann. Neurol. 66:253–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aksamit AJ, Sever JL, Major EO. 1986. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: JC virus detection by in situ hybridization compared with immunohistochemistry. Neurology 36:499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Henderson LJ, Sharma A, Monaco MC, Major EO, Al-Harthi L. 2012. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transactivator of transcription through its intact core and cysteine-rich domains inhibits Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in astrocytes: relevance to HIV neuropathogenesis. J. Neurosci. 32:16306–16313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krencik R, Zhang SC. 2011. Directed differentiation of functional astroglial subtypes from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Protoc. 6:1710–1717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Krencik R, Weick JP, Liu Y, Zhang ZJ, Zhang SC. 2011. Specification of transplantable astroglial subtypes from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 29:528–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Obayashi S, Tabunoki H, Kim SU, Satoh J. 2009. Gene expression profiling of human neural progenitor cells following the serum-induced astrocyte differentiation. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 29:423–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferenczy MW, Marshall LJ, Nelson CD, Atwood WJ, Nath A, Khalili K, Major EO. 2012. Molecular biology, epidemiology, and pathogenesis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, the JC virus-induced demyelinating disease of the human brain. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 25:471–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donati D, Martinelli E, Cassiani-Ingoni R, Ahlqvist J, Hou J, Major EO, Jacobson S. 2005. Variant-specific tropism of human herpesvirus 6 in human astrocytes. J. Virol. 79:9439–9448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ravichandran V, Major EO, Ibe C, Monaco MC, Girisetty MK, Hewlett IK. 2011. Susceptibility of human primary neuronal cells to xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related (XMRV) virus infection. Virol. J. 8:443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gosert R, Rinaldo CH, Wernli M, Major EO, Hirsch HH. 2011. CMX001 (1-O-hexadecyloxypropyl-cidofovir) inhibits polyomavirus JC replication in human brain progenitor-derived astrocytes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2129–2136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin JD, King DM, Slauch JM, Frisque RJ. 1985. Differences in regulatory sequences of naturally occurring JC virus variants. J. Virol. 53:306–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Messam CA, Hou J, Berman JW, Major EO. 2002. Analysis of the temporal expression of nestin in human fetal brain derived neuronal and glial progenitor cells. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 134:87–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Monaco MC, Sabath BF, Durham LC, Major EO. 2001. JC virus multiplication in human hematopoietic progenitor cells requires the NF-1 class D transcription factor. J. Virol. 75:9687–9695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Willems E, Leyns L, Vandesompele J. 2008. Standardization of real-time PCR gene expression data from independent biological replicates. Anal. Biochem. 379:127–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Messeguer X, Escudero R, Farre D, Nunez O, Martinez J, Alba MM. 2002. PROMO: detection of known transcription regulatory elements using species-tailored searches. Bioinformatics 18:333–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Farre D, Roset R, Huerta M, Adsuara JE, Rosello L, Alba MM, Messeguer X. 2003. Identification of patterns in biological sequences at the ALGGEN server: PROMO and MALGEN. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:3651–3653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ingenuity Systems 2012. A novel approach to predicting upstream regulators. Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ingenuity Systems 2012. Ingenuity upstream regulator analysis in IPA. Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cahoy JD, Emery B, Kaushal A, Foo LC, Zamanian JL, Christopherson KS, Xing Y, Lubischer JL, Krieg PA, Krupenko SA, Thompson WJ, Barres BA. 2008. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J. Neurosci. 28:264–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wu HH, Bellmunt E, Scheib JL, Venegas V, Burkert C, Reichardt LF, Zhou Z, Farinas I, Carter BD. 2009. Glial precursors clear sensory neuron corpses during development via Jedi-1, an engulfment receptor. Nat. Neurosci. 12:1534–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Draberova E, Del Valle L, Gordon J, Markova V, Smejkalova B, Bertrand L, de Chadarevian JP, Agamanolis DP, Legido A, Khalili K, Draber P, Katsetos CD. 2008. Class III beta-tubulin is constitutively coexpressed with glial fibrillary acidic protein and nestin in midgestational human fetal astrocytes: implications for phenotypic identity. J. Neuropathol Exp. Neurol. 67:341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gongidi V, Ring C, Moody M, Brekken R, Sage EH, Rakic P, Anton ES. 2004. SPARC-like 1 regulates the terminal phase of radial glia-guided migration in the cerebral cortex. Neuron 41:57–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Anthony TE, Klein C, Fishell G, Heintz N. 2004. Radial glia serve as neuronal progenitors in all regions of the central nervous system. Neuron 41:881–890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Romagnoli L, Sariyer IK, Tung J, Feliciano M, Sawaya BE, Del Valle L, Ferrante P, Khalili K, Safak M, White MK. 2008. Early growth response-1 protein is induced by JC virus infection and binds and regulates the JC virus promoter. Virology 375:331–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kim J, Woolridge S, Biffi R, Borghi E, Lassak A, Ferrante P, Amini S, Khalili K, Safak M. 2003. Members of the AP-1 family, c-Jun and c-Fos, functionally interact with JC virus early regulatory protein large T antigen. J. Virol. 77:5241–5252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sadowska B, Barrucco R, Khalili K, Safak M. 2003. Regulation of human polyomavirus JC virus gene transcription by AP-1 in glial cells. J. Virol. 77:665–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ravichandran V, Major EO. 2008. DNA-binding transcription factor NF-1A negatively regulates JC virus multiplication. J. Gen. Virol. 89:1396–1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gronostajski RM. 2000. Roles of the NFI/CTF gene family in transcription and development. Gene 249:31–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marshall LJ, Dunham L, Major EO. 2010. Transcription factor Spi-B binds unique sequences present in the tandem repeat promoter/enhancer of JC virus and supports viral activity. J. Gen. Virol. 91:3042–3052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Amemiya K, Traub R, Durham L, Major EO. 1992. Adjacent nuclear factor-1 and activator protein binding sites in the enhancer of the neurotropic JC virus. A common characteristic of many brain-specific genes. J. Biol. Chem. 267:14204–14211 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dejong V, Degeorges A, Filleur S, Ait-Si-Ali S, Mettouchi A, Bornstein P, Binetruy B, Cabon F. 1999. The Wilms' tumor gene product represses the transcription of thrombospondin 1 in response to overexpression of c-Jun. Oncogene 18:3143–3151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Diamond MI, Miner JN, Yoshinaga SK, Yamamoto KR. 1990. Transcription factor interactions: selectors of positive or negative regulation from a single DNA element. Science 249:1266–1272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gottlicher M, Heck S, Doucas V, Wade E, Kullmann M, Cato AC, Evans RM, Herrlich P. 1996. Interaction of the Ubc9 human homologue with c-Jun and with the glucocorticoid receptor. Steroids 61:257–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hahn SL, Wasylyk B, Criqui-Filipe P. 1997. Modulation of ETS-1 transcriptional activity by huUBC9, a ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Oncogene 15:1489–1495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Garcia-Gutierrez P, Juarez-Vicente F, Gallardo-Chamizo F, Charnay P, Garcia-Dominguez M. 2011. The transcription factor Krox20 is an E3 ligase that sumoylates its Nab coregulators. EMBO Rep. 12:1018–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Su GH, Ip HS, Cobb BS, Lu MM, Chen HM, Simon MC. 1996. The Ets protein Spi-B is expressed exclusively in B cells and T cells during development. J. Exp. Med. 184:203–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rao S, Matsumura A, Yoon J, Simon MC. 1999. SPI-B activates transcription via a unique proline, serine, and threonine domain and exhibits DNA binding affinity differences from PU.1. J. Biol. Chem. 274:11115–11124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marshall LJ, Moore LD, Mirsky MM, Major EO. 2012. JC virus promoter/enhancers contain TATA box-associated Spi-B-binding sites that support early viral gene expression in primary astrocytes. J. Gen. Virol. 93:651–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reya T, O'Riordan M, Okamura R, Devaney E, Willert K, Nusse R, Grosschedl R. 2000. Wnt signaling regulates B lymphocyte proliferation through a LEF-1 dependent mechanism. Immunity 13:15–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Labbe E, Letamendia A, Attisano L. 2000. Association of Smads with lymphoid enhancer binding factor 1/T cell-specific factor mediates cooperative signaling by the transforming growth factor-beta and wnt pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:8358–8363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rivat C, Le Floch N, Sabbah M, Teyrol I, Redeuilh G, Bruyneel E, Mareel M, Matrisian LM, Crawford HC, Gespach C, Attoub S. 2003. Synergistic cooperation between the AP-1 and LEF-1 transcription factors in activation of the matrilysin promoter by the src oncogene: implications in cellular invasion. FASEB J. 17:1721–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang Y, Feng XH, Derynck R. 1998. Smad3 and Smad4 cooperate with c-Jun/c-Fos to mediate TGF-beta-induced transcription. Nature 394:909–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zaidi SK, Sullivan AJ, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Stein GS, Lian JB. 2002. Integration of Runx and Smad regulatory signals at transcriptionally active subnuclear sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99:8048–8053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hess J, Porte D, Munz C, Angel P. 2001. AP-1 and Cbfa/runt physically interact and regulate parathyroid hormone-dependent MMP13 expression in osteoblasts through a new osteoblast-specific element 2/AP-1 composite element. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20029–20038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Friedman AD. 2009. Cell cycle and developmental control of hematopoiesis by Runx1. J. Cell. Physiol. 219:520–524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ravichandran V, Jensen PN, Major EO. 2007. MEK1/2 inhibitors block basal and transforming growth factor 1beta1-stimulated JC virus multiplication. J. Virol. 81:6412–6418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Derynck R, Zhang YE. 2003. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 425:577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.