Abstract

Whole grain (WG)-rich diets are purported to have a variety of health benefits, including a favorable role in body weight regulation. Current dietary recommendations advocate substituting WG for refined grains (RG), because many of the beneficial bioactive components intrinsic to WG are lost during the refining process. Epidemiological studies consistently demonstrate that higher intakes of WG, but not RG, are associated with lower BMI and/or reduced risk of obesity. However, recent clinical trials have failed to support a role for WG in promoting weight loss or maintenance. Though the biochemical and structural characteristics of WG have been shown to modulate appetite, nutrient availability, and energy utilization, the capacity of WG foods to elicit these effects varies with the type and amount of grain consumed as well as the nature of its consumption. As such, WG foods differentially affect physiologic factors influencing body weight with the common practice of processing and reconstituting WG ingredients during food production likely mitigating the capacity for WG to benefit body weight regulation.

Introduction

Obesity is a predominant public health concern (1, 2) with related health care costs now estimated at more than $190 billion annually in the United States (3). Diet composition is among many lifestyle factors contributing to the development of obesity and associated chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and type 2 diabetes. As such, identifying dietary patterns, or individual foods and nutrients that should be increased or decreased in the diet to prevent and treat obesity, is an important public health strategy. Consuming whole grains (WG)3 is postulated to decrease chronic disease risk, in part due to beneficial effects on body weight regulation (4–6).

The American Association of Cereal Chemists (AACC) defines a WG food ingredient as consisting of the “intact, ground, cracked or flaked caryopsis (kernel) whose principal components—the starchy endosperm, germ, and bran—are present in the same relative proportions as they exist in the intact caryopsis” (7). Slight derivations of this definition have been proposed and a recognized need for an internationally accepted definition exists (8). Caryopses are the edible seeds of cereal crops that consist of 3 primary anatomical components: endosperm, germ, and bran. The endosperm comprises the largest portion of the grain, consisting primarily of storage proteins and starches needed to feed the germ during maturation (6). The germ contains the embryo and the bran acts as a multi-layered protective barrier for the grain (9). Though fiber, vitamins, minerals, and other phytochemicals are present throughout the grain, the bran and germ are more concentrated sources than endosperm (9).

The most commonly consumed WG worldwide are wheat, brown and long-grain rice, maize, oats, barley, rye, millet, sorghum, and triticale (9). Currently, these grains are more commonly processed (e.g., milled, cracked, rolled, ground, crushed, and flaked) and reconstituted before consumption than consumed in their intact form (10). Refined cereal grains (RG) are not fully reconstituted after processing and consist primarily of endosperm retained after the separation and removal of the bran and germ. Although the refining process improves the texture and stability of grain-based food products, much of the nutritive value of the WG is lost. Importantly, the AACC definition of a WG ingredient requires that the endosperm, bran, and germ isolated from the WG during processing be reconstituted in the same relative proportions as exists in the intact native grain. Thus, WG are generally richer in dietary fiber, vitamins, minerals, phytoestrogens, phenolic compounds, and phytic acid relative to their refined counterparts (11). The AACC definition, however, does not stipulate that the WG structure remain intact, nor does it limit the degree of processing or minimum particle size of the WG.

The superior nutritive value of WG relative to RG and associations of increased WG intake with reduced cardiovascular disease (12, 13), cancer (14, 15), and type 2 diabetes risk (16) underpin dietary recommendations worldwide encouraging WG consumption. The 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (17) recommend substituting WG for RG to consume at least 1.5 ounce-equivalents WG ⋅ 1000 kcal−1 ⋅ d−1 (≥24 g WG ⋅ 4185 kJ−1⋅d−1). Similarly, a number of European countries (18–23), Australia (24), and Canada (25) have recommendations encouraging intake of WG foods. Concomitant to these recommendations, the number of WG-containing food products introduced into the U.S. marketplace, e.g., has considerably increased over the past decade (26). However, WG consumption remains well below recommended levels for many (27), especially in the United States (28, 29). In this review, we examine the evidence for a role of WG in body weight regulation.

WG and body weight regulation: observational studies

Jonnalagadda et al. (4) recently described issues associated with estimating and comparing WG intakes in observational studies. Briefly, definitions of WG foods have varied across studies, with the most commonly used definitions being derivations of that proposed by Jacobs et al. (30). This definition includes food items such as dark bread, brown rice, oatmeal, popcorn, and breakfast cereals containing ≥25% WG or bran by weight. Added germ and bran are frequently included in the definition as well. This definition contrasts with the less commonly employed U.S. FDA definition used for health claims, which requires a WG food be ≥51% WG by weight and contain germ, bran, and endosperm in the same relative proportions as are found in the intact grain. The amount of WG in a serving of a WG food therefore varies based on the definition used in addition to the relative proportion of WG to RG in the food. The fact that the exact relative proportion of WG and RG grain ingredients is proprietary information and often unknown further complicates attempts to accurately quantify WG intake (4). Thus, WG intake may be under- or overestimated, resulting in misclassification and bias.

Despite differences in the definitions and methods used to estimate WG intake, the bulk of the epidemiological evidence suggests that WG have a beneficial role in body weight regulation. A 2008 meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies examining associations between WG intake and BMI summarized 15 studies including 119,829 primarily European and American adults (31). Harland et al. (31) documented a 0.6-kg/m2 lower BMI in individuals categorized as reporting the highest (∼3 servings/d) compared with the lowest (<0.5 servings/d) WG intakes. The inverse association between WG intake and BMI was consistent, documented in 12 of the 15 studies reviewed (30, 32–45), and is supported by recent reports (16, 29, 46–50). For example, using the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging cohort Newby et al. (49) documented a 0.7-kg/m2 lower BMI in individuals in the highest (2.8 servings/d) relative to lowest (<1 serving/d) quintile of WG intake. Likewise, McKeown et al. (47) reported a 1.1-kg/m2 lower BMI in individuals in the highest (2.9 servings/d) relative to lowest (0.1 servings/d) quintile of WG intake within a subset of the Framingham Heart Offspring and Third Generation cohorts. Nearly identical results were documented in a cohort of older adults with a 1.0-kg/m2 lower BMI being observed in individuals in the highest (2.9 servings/d) relative to lowest (0.2 servings /d) quartile of WG intake (48). Of note, the inverse associations between WG intake and BMI observed in these cross-sectional studies do not appear to simply reflect a beneficial effect of total grain intake on body weight regulation, because positive (33, 35, 47) or null (30, 36–38, 48, 49) associations between RG intake and BMI were reported.

Prospective cohort studies support a role for WG in attenuating weight gain (32, 34, 35). Liu et al. (35) used the Nurses Health Study cohort to examine relationships between changes in WG and RG intakes, weight change, and obesity risk. Following 12 y of follow-up, women in the quintile representing the largest increase in WG intake (0.9 servings ⋅ 4185 kJ−1 ⋅ d−1) compared with those in the quintile representing the largest decrease in WG intake (−0.6 servings ⋅ 4185 kJ−1 ⋅ d−1) experienced a 0.4-kg lower weight gain (4.1 vs. 4.5 kg) and 19% lower odds of developing obesity (35). In contrast, women with the largest increase in RG intake (0.9 servings ⋅ 4185 kJ−1 ⋅ d−1) experienced a 0.4-kg greater increase in body weight (4.7 vs. 4.3 kg) and 18% higher odds of developing obesity compared with those with the largest reduction in RG intake (−0.9 servings ⋅ 4185 kJ−1 ⋅ d−1) (35). Similarly, Koh-Banarjee et al. (34) used the Health Professionals Follow-up Study cohort to examine relationships between WG and RG intakes and weight gain by categorizing men into quintiles of change in WG or RG intake. After 8 y of follow-up, a 0.5-kg lower weight gain (0.7 vs. 1.2 kg) was observed in men reporting the greatest increase in WG intake (1.5 servings/d) compared with those with the largest decreases in WG intake (−0.9 serving/d) (34). No benefit of RG intake on prospective weight change was documented (34). Finally, in the Physicians’ Health Study, consumption of ≥1 serving/d compared with <1 serving/wk of WG breakfast cereals was associated with a 0.4-kg lower weight gain over 13 y (1.9 vs. 2.3 kg) in age-adjusted models (32). In this study, a 0.4-kg lower weight gain (1.8 vs. 2.3 kg) was also observed in men consuming ≥1 serving/d of RG breakfast cereals compared with those who reported consuming these cereals <1/wk (32).

In addition to beneficial effects on body weight, WG consumption may be associated with reduced abdominal adiposity. In a subset of studies included in the meta-analysis of Harland et al. (31), the highest WG consumers were determined to have a 2.7-cm lower waist circumference (WC) and 0.02 lower waist:hip ratio compared with the lowest WG consumers. McKeown et al. (47, 48) recently advanced these findings by reporting associations between WG intake and direct measures of adiposity obtained by DXA and computed tomography. Older adults in the highest (2.9 servings/d) relative to lowest (0.2 servings/d) quartile of WG intake had 2.4% lower total body fat and 3.6% lower trunk fat (48). Within a subset of the Framingham Offspring cohort, visceral adipose tissue volume as measured by computed tomography was 10% lower in individuals in the highest (2.9 servings/d) compared with lowest (0.1 servings/d) quintiles of WG intake (47). Interestingly, no association between WG intake and visceral adiposity was observed in individuals consuming ≥4 daily servings of RG, suggesting that high RG intake may counter any benefits of WG on body weight regulation (47). Few prospective cohort studies have directly examined associations between WG intake and central adiposity. In 2 separate studies, Halkjaer et al. (51, 52) reported no association between intake of WG food products (51) or breads (52) and prospective WC change in Danish adults, but they noted a positive association between intake of RG food products or breads and WC change in women.

In summary, observational studies strongly suggest that consuming ∼3 servings/d WG is associated with lower BMI and central adiposity relative to low or no WG consumption, and higher WG intakes may attenuate weight gain. These relationships appear to be specific to WG, because intakes of RG have not generally been associated with lower BMI or adiposity in these studies. Of note, the meta-analysis of Harland et al. (31) demonstrated that higher WG intakes were associated with both increased energy and dietary fiber intakes and lower smoking prevalence. The greater energy intakes observed in high WG consumers is likely associated with the trend for higher prevalence of exercise also reported in these individuals (31). Further, Harland et al. (31) noted trends for higher micronutrient intakes and supplement use and lower saturated fat intakes in the highest compared with lowest WG consumers. Recent reports are generally consistent with these findings, demonstrating that high WG consumers tend to be more physically active, smoke less, and consume more fruit, vegetables, and dietary fiber than low WG consumers (46, 47, 49, 53). Further, cluster and factor analyses frequently link WG consumption with dietary patterns that include high fruit and vegetable intake and that are associated with other desirable health behaviors (54, 55). Although statistical adjustment for these lifestyle factors is common, the potential for residual confounding remains; therefore, associations between high WG intake and lower BMI may be mediated by healthier lifestyles of WG consumers.

WG and body weight regulation: clinical trials

A number of recent randomized controlled trials investigating the effects of consuming WG relative to RG on biomarkers of health status have reported changes in appetite, energy intake, body weight, or body composition as primary or secondary outcomes following incorporation of WG into diets consumed ad libitum or into energy-restricted diets for weight loss. Ad libitum intake studies commonly incorporated ≥48 g WG/d (3 ounce-equivalents/d) or a similar amount of RG derived from a variety of sources (56–60) or single food items such as WG breakfast cereal (61–63) or bread (64) into participant diets over 2–52 wk. Only 2 of these studies reported perceived appetite or ad libitum energy intake as primary outcomes (Table 1) (63, 64). Isaksson et al. (63) documented postprandial reductions in perceived appetite following consumption of a WG rye breakfast porridge providing 55 g WG/d compared with refined wheat bread. This effect persisted after daily consumption of the porridge for 3 wk but did not translate into reduced energy intake or weight loss (63). In a pilot study of 14 participants, Bodinham et al. (64) observed no differential effects on perceived appetite or ad libitum energy intake over 3 wk in which WG wheat rolls providing 48 g/d WG or RG rolls were added to habitual diets. Similarly, no evidence for a spontaneous reduction in energy intake or body weight in response to WG interventions was observed in any study in which these measures were reported as secondary outcomes (56–61, 65, 66). However, all but 3 of these studies (61, 65, 66) appear to have encouraged body weight maintenance or adherence to habitual diets (excepting the intervention component) throughout the intervention (Table 1). Therefore, the reported results cannot reliably assess whether increased WG consumption should be expected to promote a spontaneous reduction in energy intake and weight loss. Two of the trials in which no recommendations regarding energy intake were given were ≤3 wk duration and therefore too short to infer effects on body weight outcomes (61, 66). Ross et al. (66) did, however, report energy intake, documenting no significant effect on energy intake while substituting 150 g/d WG for RG into a diet in which all foods were provided over 2 wk. In another study, Brownlee et al. (65) attempted to investigate the effects of substituting 60 g/d or 120 g/d of WG from a variety of sources for RG on cardiovascular risk factors to include body weight and adiposity. The authors noted that volunteers more often appeared to add rather than substitute WG into their habitual diets, with energy intake increasing concomitant with WG intake. No significant changes in body weight or body fat were documented in any group (65).

Table 1.

Clinical studies of WG intake and energy regulation1

| Reference | Design and population | Intervention | Fiber intake, g/d | ∆ Weight, kg | ∆ Body composition | Appetite/ (∆) energy intake, kJ/d |

| Energy intake ad libitum | ||||||

| Bodinham et al. (64) | 3 wk CO; n = 14 | WG: 48 g WG/d, milled wheat bread | WG: 30* | Ø | BF: Ø | Ø / |

| Nrmwt M/F, 26 y | C: RG bread | C: 26 | WC: Ø | WG: 0 | ||

| C: +368 | ||||||

| Brownlee et al. (65) | 16 wk RCT; n = 266 | WG1: 60 g WG/d for 8 wk | WG1: +11* WG2: +5* | WG1: +0.2 | BF: | Not measured/ |

| Ovwt and Ob M/F, 18–65 y | + 120 g WG/d for 8 wk2 | WG2: +0.7 | WG1: +0.3% | WG1: +585* | ||

| WG2: 60 g WG/d for 16 wk2 | C: 0 | WG2: +1.0% | WG2: +389 | |||

| C: no intervention | C: +0.3% | C: −677 | ||||

| WC: Ø | ||||||

| Carvalho-Wells et al. (61) | 3 wk CO; n = 32 | WG: 48 g WG/d, maize semolina breakfast cereal | WG: 14*,4C: 3 | Ø | WC: Ø | Not measured/Not measured |

| Nrmwt, Ovwt, and Ob | C: RG breakfast cereal | |||||

| M/F, 20–51 y | ||||||

| Isaksson et al. (63) | 3 wk CO; n = 24 | WG: 55 g WG/d, cut and rolled rye porridge | WG: 21 | Ø | Not measured | ↓H, ↓DTE, |

| Nrmwt M/F, 18–60 y | C: RG wheat bread | C: 15 | ↑S after WG | |||

| breakfast; Ø | ||||||

| after lunch3/ | ||||||

| WG: −4 | ||||||

| C: −184 | ||||||

| Ross et al. (66) | 2 wk CO; n = 17 | WG: 150 g WG/d2 | WG: 32* | WG: −0.5 | Not measured | Not measured/ |

| Nrmwt M/F, 20–50 y | C: RG foods | C: 19 | C: 0 | WG: 8414 | ||

| C: 8628 | ||||||

| Energy intake restricted | ||||||

| Katcher et al. (67) | 12 wk RCT; n = 47 | WG: 4–7 oz-eq WG foods/d2 | WG: 21* | WG: −3.7 | BF: | Not measured/ |

| Ob M/F with MetS, 20–65 y | C: Avoid WG foods | C: 15 | C: −5.3 | WG: −1.2% | WG: −1488 | |

| All: 2090 kJ/d (500 kcal/d) energy deficit + DG 2005 + activity | C: −1.0% | C: −2884 | ||||

| Abdominal BF: | ||||||

| WG: −2.2%* | ||||||

| C: −0.9% | ||||||

| WC: | ||||||

| WG: −2.5 cm | ||||||

| C: −4.7 cm | ||||||

| Kristensen et al. (68) | 12 wk RCT; n = 72 | WG: 105 g WG/d2 | WG: 11*,4 | WG: −3.6 | Total FM: | Not measured/ |

| Ovwt and Ob postmenopausal F, 45–70 y | C: RG foods | C: 4 | C: −2.7 | WG: −3.0%*,5 | WG: 6329 | |

| All: 1254 kJ/d (300 kcal/d) energy deficit | C: −2.1% | C: 6061 | ||||

| Central FM: | ||||||

| WG: −3.8%** | ||||||

| C: −2.7% | ||||||

| WC: | ||||||

| WG: −4.1 cm | ||||||

| C: −4.1 cm | ||||||

| Maki et al. (69) | 12 wk RCT; n = 144 | WG: 3 c/d oat cereal | WG: 22* | WG: −2.2 | WC: | Not measured/ |

| Ovwt and Ob M/F, 20–65 y | C: Low-fiber foods | C: 13 | C: −1.7 | WG: −3.3 cm* | WG: −1714 | |

| All: 2090 kJ/d (500 kcal/d) energy deficit | C: −1.9 cm | C: −1714 | ||||

| Melanson et al. (70) | 24 wk RCT; n = 92 | WG: 40–80 g/d WG breakfast cereal | WG: 23* | WG: −4.7 | Not measured | Not measured/ |

| Ovwt and Ob M/F, 18–70 y | C: Avoid breakfast cereals | C: 17 | C: −5.0 | WG: −2901 | ||

| All: 2090 kJ/d (500 kcal/d) energy deficit from diet + exercise | C: −1793 | |||||

| Saltzman et al. (71) | 6 wk RCT; n = 41 | WG: 45 g ⋅ 4185 kJ-1 ⋅ d#x22121 rolled oats | WG: 17* | WG: −4.4 | FM: | Trend for ↓H |

| Nrmwt, Ovwt, and Ob | C: 45 g ⋅ 4185 kJ-1 ⋅ d#x22121 RG wheat | C: 13 | C: −4.3 | WG: −2.6 kg | on WG diet**/ | |

| M/F, 18–78 y | All: 4185 kJ/d (1000 kcal/d) energy deficit | C: −3.0 kg | WG: −3678 | |||

| C: −3816 |

**P ≤ 0.1, *P < 0.05 compared with control. Ø, no difference (actual values not reported); BF, body fat percentage; C, control; CO, crossover; DG, Dietary Guidelines for Americans; DTE, desire to eat; F, female; FM, fat mass; H, hunger; M, male; MetS, metabolic syndrome; Nrmwt, normal-weight (18.5 kg/m2 ≤ BMI <25 kg/m2); Ovwt, overweight (25 kg/m2 ≤ BMI <30 kg/m2); Ob, obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2); oz-eq, ounce-equivalents; RG, refined grain; s/d, servings per day; S, satiety; WC, waist circumference; WG, whole grain; wt, body weight.

Various sources of WG consumed.

Measured over 12 h following WG or RG test meal.

From intervention foods.

Percent change.

Recent studies have also examined whether incorporating WG into energy-restricted diets enhances weight loss beyond energy restriction alone (67–71). Taken together, these studies provide no evidence that a hypoenergetic diet that includes ∼3–7 daily servings of WG (48–112 g/d WG) promotes greater weight loss than a low-WG hypoenergetic diet (Table 1). However, in 2 of 3 studies in which body fatness was directly measured using DXA (67, 68) or hydrostatic weighing (71), hypoenergetic WG-containing diets were associated with a greater reduction in body fat, primarily from the abdominal region, relative to hypoenergetic low-WG diets despite conferring no additional weight loss benefit (67, 68). Katcher et al. (67) randomly assigned 50 obese adults with metabolic syndrome to receive dietary advice to obtain all recommended daily grain servings from either WG or non-WG sources while reducing energy intake 2090 kJ/d (500 kcal/d) from weight maintenance requirements. The group receiving the advice to increase WG intake averaged 5 servings/d WG compared with <0.25 servings/d in controls. Although reductions in total body fat, abdominal fat, and WC were observed in both groups after 12 wk, the abdominal fat loss was 1.3% greater in the WG group (67). In another trial, Kristensen et al. (68) instructed overweight and obese postmenopausal women to reduce energy intake by ≥1255 kJ/d (300 kcal/d) from weight maintenance requirements and to consume ∼1985 kJ/d (475 kcal/d) of either WG or RG foods that were provided to participants. Total body and central fat mass and WC were reduced in both groups; however, decreases in total fat mass were significantly greater and decreases in central fat mass tended to be greater in women consuming the WG-rich diet (68). In contrast, substituting 84 g/d oats for RG wheat in a hypoenergetic diet did not differentially affect body fat loss over 6 wk in healthy adults (71). The inclusion of normal-weight participants, a greater energy deficit of 4185 kJ/d (1000 kcal/d), type of grain used, or shorter duration of this study may account for the discrepant results.

In summary, recent clinical trials provide little evidence for an effect, beneficial or detrimental, of WG intake on body weight regulation. When WG are added to or substituted for RG in ad libitum diets, no spontaneous reduction in energy intake or body weight is observed. Likewise, on the background of a hypoenergetic diet for weight loss, substituting WG for RG does not appear to promote body weight loss beyond energy restriction alone. In 2 separate studies, WG-rich hypoenergetic diets appeared to be associated with greater losses of body fat or central body fat. However, the observed effect sizes were small, within the measurement error of the methods used to assess fat mass (72–74), and not always consistent with changes in WC (67, 68). These findings should therefore be considered preliminary but warrant further investigation.

Factors mediating physiological effects of WG relevant to the regulation of body weight and composition

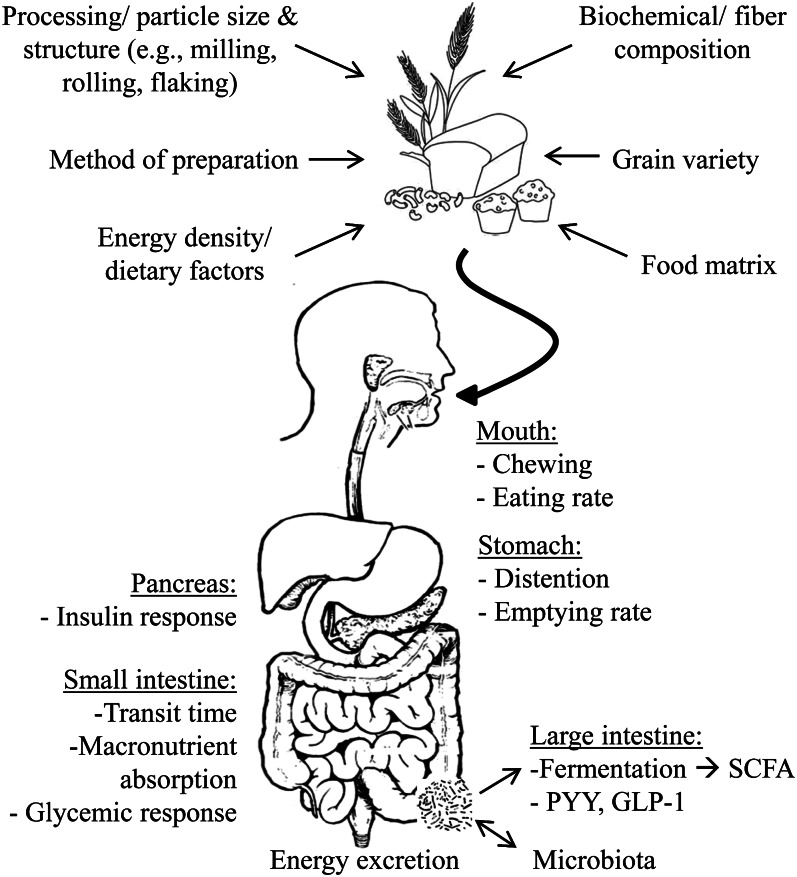

The structural and physicochemical properties of WG are diverse and made more so when incorporated into foods. This diversity is the result of the varied chemical compositions and quantities of indigestible carbohydrates within different WG, the degree to which grains are processed prior to consumption, the methods by which WG foods are prepared, and interactions with the food matrix (75). Together, these factors mediate the physiological effects of WG and may in turn differentially influence short-term appetite regulation and nutrient utilization, thereby altering WG-mediated effects on the regulation of body weight and composition (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Structural and physicochemical properties of WG foods mediate the effect of WG on physiologic factors influencing body weight and composition. GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; PYY, peptide-YY; WG, whole grain.

Chewing

The fiber content, particle size, and structural integrity of WG alter the amount of chewing required for ingestion of WG foods (76, 77). Increased chewing may promote satiation by enhancing gastric distention (78), augmenting gut hormone responses (79, 80), prolonging orosensory stimulation (81), or slowing eating rate (82, 83).

Energy density and availability

WG foods generally have a lower energy density, defined as digestible energy per unit weight, than comparable RG foods. This effect derives from the low digestible energy per unit mass (84) and water-holding capacities of dietary fibers intrinsic to many WG. Short-term studies have demonstrated that humans have a tendency to eat a consistent weight of food irrespective of energy content, indicating that from meal to meal, appetite is influenced more by the mass of food than the amount of energy consumed (85–87). Consequently, decreasing dietary energy density results in a reduction in energy intake without a concomitant increase in hunger (88, 89).

The magnitude of the reduction in energy density that can be achieved using WG, however, varies with the amount and type of fiber present in the grain. WG contain both nonfermentable fibers, which provide no digestible energy, and fibers that are fermented to varying degrees by colonic microbes salvaging otherwise unavailable energy in the form of SCFA. Further, viscous fibers present in varying amounts within different WG decrease digestible energy by impairing macronutrient digestion and absorption, leading to energy excretion (90, 91).

Energy digestibility has been shown to decrease by 3–4% following 20- to 25-g/d increases in dietary fiber intake, a reduction equivalent to ∼418 kJ/d (100 kcal/d) in these studies (92, 93). This relationship appears to be dose dependent, as evidenced by manipulations of dietary fiber content leading to 150-kJ/d (36 kcal/d) increases in fecal energy content for each additional 5 g/d fiber consumed (94). Similar effects on energy availability appear to be achieved when dietary substitutions of WG for RG are made, but only if dietary fiber intake increases substantially. Substituting ≥350 g/d of coarse or finely ground wholemeal bread for mixed wheat bread resulted in a 21-g/d increase in dietary fiber intake and a 3% reduction in digestible energy (95). However, substituting 105 g/d milled WG for RG did not affect fecal energy excretion when dietary fiber intake increased by only 7 g/d (68). Similarly, an 84-g/d rolled oats intervention did not affect the fecal energy content of healthy adults despite a 4-g/d increase in soluble fiber intake (71). Taken together, these findings suggest that consuming WG-rich foods may contribute to body weight regulation, at least in the short term, by reducing energy availability, but only if substantial increases in dietary fiber intake are concurrent.

Glycemic response

By combination of reduced nutrient availability and delayed gastric emptying, viscous fibers reduce the postprandial glycemic response (90). Foods that elicit high glycemic responses are postulated to promote fat storage and hunger by augmenting postprandial insulin secretion and altering counter-regulatory hormone responses (96, 97). However, the glycemic response associated with consuming WG foods is less dependent on the fiber content of the grain. Rather, factors such as the structural integrity, grain particle size after processing, and the food matrix appear to be the primary determinants of glycemic responses to WG foods (98).

Holt et al. (77) demonstrated progressive reductions in postprandial glycemic and insulinemic responses with increasing particle size following consumption of WG wheat provided in intact, cracked, coarse, and finely ground forms and similar findings have been reported for maize, barley, and rice (99–102). Appetite may also be affected by grain processing, as Holt et al. (77) documented higher satiety ratings following consumption of the intact relative to the finely ground grain. More recently, Kristensen et al. (103) measured glycemic responses and appetite following consumption of 4 separate meals composed of either bread or pasta made using milled WG wheat or refined wheat flours. No differences in energy intake at the subsequent meal were observed, though the WG bread was rated as more satiating that the RG wheat bread. Consuming WG foods had no effect on glycemic responses despite being higher in fiber, suggesting the relative importance of particle size and structural integrity. Further, glycemic responses were attenuated following consumption of the pastas compared with the breads, demonstrating the importance of the food matrix on glycemia (103).

In addition to postprandial modulation of glycemic responses, WG-rich meals have also been shown to favorably affect glucose metabolism following the subsequent meal (104), an occurrence termed the “second meal effect.” Nilsson et al. (105, 106) recently extended this finding by demonstrating that, relative to RG wheat bread, consuming an equivalent amount of available carbohydrate from barley kernels prepared using various methods at evening meals depressed the glycemic response following a standardized breakfast the next morning. Colonic fermentation of indigestible carbohydrate was postulated to be an underlying mechanism as evidenced by inverse associations between glycemic responses and breath hydrogen, plasma SCFA, and plasma glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) concentrations (106, 107). Similar effects, however, were not observed when wheat kernels were substituted for barley (105) or when the barley meal was consumed at breakfast and glycemic responses measured following the subsequent dinner 9.5 h later (108). In a separate study, compared with RG wheat bread, an evening meal consisting of barley kernels depressed the postprandial glycemic response, enhanced peripheral insulin sensitivity, and increased breath hydrogen and plasma butyrate concentrations the following morning (109). Of note, the fiber contents of the barley meals consumed in these studies exceeded the average daily amount consumed by Americans (110) and reached 81 g/meal (106). Thus, whether these findings are applicable to the types and amounts of WG commonly consumed is unclear.

Fermentation and the gut microbiota

The studies of Nilsson et al. (105–108) and Priebe et al. (109) draw attention to the potential influence of the gut microbiota in mediating relationships between WG intake and body weight regulation. SCFA produced during the fermentation of certain fibers within WG contribute to the regulation of body weight and composition by serving as metabolizable energy sources, directly mediating hepatic and peripheral glucose and lipid oxidation and stimulating secretion of the gut hormones peptide-YY and GLP-1, which act to suppress appetite, slow gastrointestinal transit, and modulate glucose metabolism (111). SCFA production is influenced by a number of factors, including the availability of fermentable substrate and the composition of the gut microbiota (112). Substrate availability and gut microbiota composition are interrelated, as evidenced by the prebiotic effect, a symbiotic relationship between the gut microbiota and human host whereby specific fermentable carbohydrate selectively promote the proliferation of colonic bacteria beneficial to host health (113). Emerging evidence has demonstrated that the composition of the gut microbiota may be linked to human obesity (114–120) and is sensitive to multiple dietary factors (116, 121–124), thus suggesting a possible role for WG in body weight regulation via modulation of the gut microbiome.

Few studies to date have investigated interrelationships between WG-based diet interventions, gut microbiota composition, and energy regulation. Consuming 48 g/d of WG wheat (125) or maize (61) cereals over 3 wk was shown to have a prebiotic effect in 2 separate trials; however, similar effects were not observed when 150 g WG/d from a variety of food sources was consumed over 2 wk (66). The short duration of these studies precludes any meaningful conclusions with regard to body weight regulation from being reached, and only one study quantified energy intake, reporting no effect of the WG intervention (66). No changes in fasting insulin, fasting glucose, or fecal SCFA concentrations were reported in any of these studies, nor was breath hydrogen excretion or endocrine mediators of appetite such as peptide-YY or GLP-1 measured.

Inulin and oligofructose are prebiotic fibers found in a variety of cereal grains but predominantly obtained from wheat products in American diets (126, 127). Daily oligofructose supplementation has been shown to alter glucose metabolism, enhance postprandial gut hormone responses, increase breath hydrogen levels, and promote weight and body fat loss, suggesting interrelationships between prebiotic fiber intake, gut microbiota activity, and energy regulation (128, 129). However, these effects may be dose dependent, because similar effects are not always observed at lower doses (130). Though these studies provide some support for a beneficial effect of intrinsic WG components on body weight regulation, the amount of oligofructose shown to be effective (>16 g/d) would be difficult to consume from WG products alone (9), and more work is needed to determine if smaller doses achieved through consumption of WG would have similar beneficial effects.

Conclusion

Evidence for beneficial effects of WG intake on body weight regulation should derive from randomized controlled trials demonstrating spontaneous weight loss, enhanced weight loss during energy restriction, or prevention of weight (re)gain in response to increased WG intake. Recent trials examining the effects of substituting WG for RG on body weight regulation do not provide evidence for a benefit of WG consumption, which is counter to epidemiologic observations. However, the nature of WG interventions employed may have dampened the ability to detect effects of WG intake on body weight regulation. In particular, the <10-g/d differences in dietary fiber intake achieved by substituting WG for RG in these studies is less than what has been reported to induce even modest weight loss (131, 132) and may have been insufficient to modulate short- or long-term mechanisms involved in body weight regulation. The differences in fiber intake achieved, however, are consistent with the increase in total daily fiber intake expected for an average individual adopting the 2010 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommendation to replace RG with WG. Currently consumed forms of WG may also mitigate the potential benefit of WG consumption on body weight or composition. Processing clearly influences WG-mediated postprandial physiologic responses, with less processing associated with metabolic effects most likely to benefit body weight and composition, specifically the blunting of postprandial glycemic and insulinemic responses. Intervention trials commonly used commercially available or similar food products in which WG ingredients are more often processed and reconstituted than consumed intact. Although using these products reflects the current food environment, the null findings may suggest that many WG products, as commonly consumed, are ineffective for facilitating weight control or triggering the underlying physiologic mechanisms.

Reproducing recent findings of beneficial effects of WG intake on body composition and elucidating the underlying mechanisms should be targeted in future trials because central adiposity is a more clinically relevant predictor of metabolic risk than body weight or BMI (133). It is intriguing to speculate that the mechanisms derive from interactions between WG intake, gut microbiota composition, and host physiology. Direct effects of the gut microbiota on fatty acid metabolism and the regulation of total body and fat mass have been demonstrated (134, 135); however, much of this work is restricted to animal and in vitro models, with the relevance to humans undetermined. Owing to recent advances in molecular biology techniques, the study of dietary influences on the human gut microbiome has become more accessible. Long-term randomized trials applying these techniques to explore interrelationships between WG-based diet interventions, gut microbiota composition, and the regulation of adiposity are needed.

In summary, intervention trials conducted to date have failed to demonstrate beneficial effects of WG intake on body weight regulation despite observational studies consistently demonstrating that high intakes of WG are associated with lower BMI, and the existence of a variety of mechanisms that could result in WG-mediated effects on body weight. Nonetheless, recent findings suggesting possible beneficial effects of WG intake on body composition deserve further attention. Investigations of sufficient duration to capture changes in body composition, providing less processed forms of WG, comparing different varieties of WG, and discriminating between effects of fiber and WG are needed. The continued development of biomarkers of WG intake is also needed for monitoring compliance in these studies. Plasma and urine alkylresorcinol concentrations are promising in this respect (66, 68), though large interindividual variation; exclusivity to WG wheat, rye, barley, and triticale; short half-life; and possible nonlinear increases at high levels of WG intake remain limitations (136).

At present, insufficient evidence exists to demonstrate clear beneficial effects of WG intake on body weight regulation. However, given the nutritive superiority of WG relative to RG, WG consumption should continue to be encouraged as part of a health-promoting diet.

Acknowledgments

Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by the USDA, Agricultural Research Service under Cooperative Agreement no. 58-1950-7-707. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USDA.

Author disclosures: J. P. Karl and E. Saltzman, no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: AACC, American Association of Cereal Chemists; GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide-1; RG, refined grain; WC, waist circumference; WG, whole grain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, et al. National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gortmaker SL, Swinburn BA, Levy D, Carter R, Mabry PL, Finegood DT, Huang T, Marsh T, Moodie ML. Changing the future of obesity: science, policy, and action. Lancet. 2011;378:838–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012;31:219–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jonnalagadda SS, Harnack L, Liu RH, McKeown N, Seal C, Liu S, Fahey GC. Putting the whole grain puzzle together: health benefits associated with whole grains: summary of American Society for Nutrition 2010 satellite symposium. J Nutr. 2011;141:S1011–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okarter N, Liu RH. Health benefits of whole grain phytochemicals. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2010;50:193–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slavin J. Whole grains and human health. Nutr Res Rev. 2004;17:99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AACC members agree on definition of whole grain [Internet]; American Association of Cereal Chemists [cited 2011 May 17]. Available from: www.aaccnet.org

- 8.Jones JM. The second C&E spring meeting and third international whole grain global summit. Cereal Foods World. 2009;54:132–5 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fardet A. New hypotheses for the health-protective mechanisms of whole-grain cereals: what is beyond fibre? Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23:65–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seal CJ, Jones AR, Whitney AD. Whole grains uncovered. Nutr Bull. 2006;31:129–37 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slavin J. Why whole grains are protective: biological mechanisms. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:129–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs DR, Jr, Gallaher DD. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a review. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2004;6:415–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellen PB, Walsh TF, Herrington DM. Whole grain intake and cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:283–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs DR, Jr, Marquart L, Slavin J, Kushi LH. Whole-grain intake and cancer: an expanded review and meta-analysis. Nutr Cancer. 1998;30:85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aune D, Chan DS, Lau R, Vieira R, Greenwood DC, Kampman E, Norat T. Dietary fibre, whole grains, and risk of colorectal cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ. 2011;343:d6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Munter JS, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Franz M, van Dam RM. Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.USDA and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.WHO. Food based dietary guidelines in the WHO European region. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office; 2003.

- 19.Ministry of Health and Welfare SSHC Dietary guidelines for adults in Greece. Arch Hellenic Med. 1999;16:516–24 [Google Scholar]

- 20.UK Foods Standard Agency healthy eating nutrition essentials [Internet] [cited 2012 May 20]. Available from: www.eatwell.gov.uk/healthydiet/nutritionessentials

- 21.National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark Wholegrain: definition and scientific background for recommendations of wholegrain intake in Denmark [Internet] [cited 2012 May 20]. Available from: www.food.dtu.dk

- 22.The Food Guide Pyramid for Germany, Austria, and Switzerland [Internet] [cited 2012 May 20]. Available from: www.dge.de/pyramide/pyramide.html

- 23.Walter P, Infanger E, Muhlemann P. Food pyramid of the Swiss Society for Nutrition. Ann Nutr Metab. 2007;51 Suppl 2:S15–20 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian Government, National Health and Medical Research Council Dietary Guidelines for Australians. Canberra ACT: Australian Government NHMRC National Mailing and Marketing; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Health Canada Canada's Food Guide; 2007. [Internet] [cited 2012 May 20]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/food-guide-aliment/index-eng.php

- 26.Mancino L, Kuchler F, Leibtag E. Getting consumers to eat more whole-grains: the role of policy, information, and food manufacturers. Food Policy. 2008;33:489–96 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lang R, Jebb SA. Who consumes whole grains, and how much? Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:123–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess-Champoux TL, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Hannan PJ, Story MT. Longitudinal and secular trends in adolescent whole-grain consumption, 1999–2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:154–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Zanovec M, Cho S. Whole-grain consumption is associated with diet quality and nutrient intake in adults: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1461–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacobs DR, Jr, Meyer KA, Kushi LH, Folsom AR. Whole-grain intake may reduce the risk of ischemic heart disease death in postmenopausal women: The Iowa Women's Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;68:248–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harland JI, Garton LE. Whole-grain intake as a marker of healthy body weight and adiposity. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:554–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bazzano LA, Song Y, Bubes V, Good CK, Manson JE, Liu S. Dietary intake of whole and refined grain breakfast cereals and weight gain in men. Obes Res. 2005;13:1952–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Whole-grain consumption and the metabolic syndrome: a favorable association in Tehranian adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:353–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koh-Banerjee P, Franz M, Sampson L, Liu S, Jacobs DR, Jr, Spiegelman D, Willett W, Rimm E. Changes in whole-grain, bran, and cereal fiber consumption in relation to 8-y weight gain among men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:1237–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu S, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hu FB, Rosner B, Colditz G. Relation between changes in intakes of dietary fiber and grain products and changes in weight and development of obesity among middle-aged women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:920–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKeown NM, Meigs JB, Liu S, Wilson PW, Jacques PF. Whole-grain intake is favorably associated with metabolic risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:390–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sahyoun NR, Jacques PF, Zhang XL, Juan W, McKeown NM. Whole-grain intake is inversely associated with the metabolic syndrome and mortality in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:124–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steffen LM, Jacobs DR, Jr, Stevens J, Shahar E, Carithers T, Folsom AR. Associations of whole-grain, refined-grain, and fruit and vegetable consumption with risks of all-cause mortality and incident coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:383–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thane CW, Stephen AM, Jebb SA. Whole grains and adiposity: little association among British adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:229–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steffen LM, Kroenke CH, Yu X, Pereira MA, Slattery ML, Van Horn L, Gross MD, Jacobs DR., Jr Associations of plant food, dairy product, and meat intakes with 15-y incidence of elevated blood pressure in young black and white adults: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1169–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larsson SC, Giovannucci E, Bergkvist L, Wolk A. Whole grain consumption and risk of colorectal cancer: a population-based cohort of 60,000 women. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:1803–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montonen J, Knekt P, Jarvinen R, Aromaa A, Reunanen A. Whole-grain and fiber intake and the incidence of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:622–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steffen LM, Jacobs DR, Jr, Murtaugh MA, Moran A, Steinberger J, Hong CP, Sinaiko AR. Whole grain intake is associated with lower body mass and greater insulin sensitivity among adolescents. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:243–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jacobs DR, Jr, Meyer HE, Solvoll K. Reduced mortality among whole grain bread eaters in men and women in the Norwegian county study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:137–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Good CK, Holschuh N, Albertson AM, Eldridge AL. Whole grain consumption and body mass index in adult women: an analysis of NHANES 1999–2000 and the USDA pyramid servings database. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:80–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lutsey PL, Jacobs DR, Jr, Kori S, Mayer-Davis E, Shea S, Steffen LM, Szklo M, Tracy R. Whole grain intake and its cross-sectional association with obesity, insulin resistance, inflammation, diabetes and subclinical CVD: The Mesa Study. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:397–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McKeown NM, Troy LM, Jacques PF, Hoffmann U, O'Donnell CJ, Fox CS. Whole- and refined-grain intakes are differentially associated with abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adiposity in healthy adults: The Framingham Heart Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1165–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKeown NM, Yoshida M, Shea MK, Jacques PF, Lichtenstein AH, Rogers G, Booth SL, Saltzman E. Whole-grain intake and cereal fiber are associated with lower abdominal adiposity in older adults. J Nutr. 2009;139:1950–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newby PK, Maras J, Bakun P, Muller D, Ferrucci L, Tucker KL. Intake of whole grains, refined grains, and cereal fiber measured with 7-d diet records and associations with risk factors for chronic disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1745–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van de Vijver LP, van den Bosch LM, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA. Whole-grain consumption, dietary fibre intake and body mass index in The Netherlands Cohort Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:31–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Halkjaer J, Tjonneland A, Thomsen BL, Overvad K, Sorensen TI. Intake of macronutrients as predictors of 5-y changes in waist circumference. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:789–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halkjaer J, Sorensen TI, Tjonneland A, Togo P, Holst C, Heitmann BL. Food and drinking patterns as predictors of 6-year BMI-adjusted changes in waist circumference. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:735–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu E, McKeown NM, Newby PK, Meigs JB, Vasan RS, Quatromoni PA, D'Agostino RB, Jacques PF. Cross-sectional association of dietary patterns with insulin-resistant phenotypes among adults without diabetes in the Framingham Offspring Study. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:576–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kant AK. Dietary patterns and health outcomes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:615–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Newby PK, Tucker KL. Empirically derived eating patterns using factor or cluster analysis: a review. Nutr Rev. 2004;62:177–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Andersson A, Tengblad S, Karlstrom B, Kamal-Eldin A, Landberg R, Basu S, Aman P, Vessby B. Whole-grain foods do not affect insulin sensitivity or markers of lipid peroxidation and inflammation in healthy, moderately overweight subjects. J Nutr. 2007;137:1401–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Enright L, Slavin J. No effect of 14 day consumption of whole grain diet compared to refined grain diet on antioxidant measures in healthy, young subjects: a pilot study. Nutr J. 2010;9:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giacco R, Clemente G, Cipriano D, Luongo D, Viscovo D, Patti L, Di Marino L, Giacco A, Naviglio D, Bianchi MA, et al. Effects of the regular consumption of wholemeal wheat foods on cardiovascular risk factors in healthy people. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:186–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McIntosh GH, Noakes M, Royle PJ, Foster PR. Whole-grain rye and wheat foods and markers of bowel health in overweight middle-aged men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:967–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tighe P, Duthie G, Vaughan N, Brittenden J, Simpson WG, Duthie S, Mutch W, Wahle K, Horgan G, Thies F. Effect of increased consumption of whole-grain foods on blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk markers in healthy middle-aged persons: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:733–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Carvalho-Wells AL, Helmolz K, Nodet C, Molzer C, Leonard C, McKevith B, Thielecke F, Jackson KG, Tuohy KM. Determination of the in vivo prebiotic potential of a maize-based whole grain breakfast cereal: a human feeding study. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1353–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Freeland KR, Wilson C, Wolever TM. Adaptation of colonic fermentation and glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion with increased wheat fibre intake for 1 year in hyperinsulinaemic human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Isaksson H, Tillander I, Andersson R, Olsson J, Fredriksson H, Webb DL, Aman P. Whole grain rye breakfast: sustained satiety during three weeks of regular consumption. Physiol Behav. 2012;105:877–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bodinham CL, Hitchen KL, Youngman PJ, Frost GS, Robertson MD. Short-term effects of whole-grain wheat on appetite and food intake in healthy adults: a pilot study. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:327–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brownlee IA, Moore C, Chatfield M, Richardson DP, Ashby P, Kuznesof SA, Jebb SA, Seal CJ. Markers of cardiovascular risk are not changed by increased whole-grain intake: The Wholeheart Study, a randomised, controlled dietary intervention. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:125–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ross AB, Bruce SJ, Blondel-Lubrano A, Oguey-Araymon S, Beaumont M, Bourgeois A, Nielsen-Moennoz C, Vigo M, Fay LB, Kochhar S, et al. A whole-grain cereal-rich diet increases plasma betaine, and tends to decrease total and ldl-cholesterol compared with a refined-grain diet in healthy subjects. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:1492–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Katcher HI, Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Gillies PJ, Demers LM, Bagshaw DM, Kris-Etherton PM. The effects of a whole grain-enriched hypocaloric diet on cardiovascular disease risk factors in men and women with metabolic syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:79–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kristensen M, Toubro S, Jensen MG, Ross AB, Riboldi G, Petronio M, Bugel S, Tetens I, Astrup A. Whole grain compared with refined wheat decreases the percentage of body fat following a 12-week, energy-restricted dietary intervention in postmenopausal women. J Nutr. 2012;142:710–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maki KC, Beiseigel JM, Jonnalagadda SS, Gugger CK, Reeves MS, Farmer MV, Kaden VN, Rains TM. Whole-grain ready-to-eat oat cereal, as part of a dietary program for weight loss, reduces low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in adults with overweight and obesity more than a dietary program including low-fiber control foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:205–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Melanson KJ, Angelopoulos TJ, Nguyen VT, Martini M, Zukley L, Lowndes J, Dube TJ, Fiutem JJ, Yount BW, Rippe JM. Consumption of whole-grain cereals during weight loss: effects on dietary quality, dietary fiber, magnesium, vitamin B-6, and obesity. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1380–8, quiz 9–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saltzman E, Moriguti JC, Das SK, Corrales A, Fuss P, Greenberg AS, Roberts SB. Effects of a cereal rich in soluble fiber on body composition and dietary compliance during consumption of a hypocaloric diet. J Am Coll Nutr. 2001;20:50–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gibson RS. Principles of nutrition assessment. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee RD. Nutritional assessment. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lohman TG, Harris M, Teixeira PJ, Weiss L. Assessing body composition and changes in body composition. Another look at dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;904:45–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Englyst KN, Englyst HN. Carbohydrate bioavailability. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haber GB, Heaton KW, Murphy D, Burroughs LF. Depletion and disruption of dietary fibre. Effects on satiety, plasma-glucose, and serum-insulin. Lancet. 1977;2:679–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Holt SH, Miller JB. Particle size, satiety and the glycaemic response. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48:496–502 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heaton KW. Food fibre as an obstacle to energy intake. Lancet. 1973;2:1418–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cassady BA, Hollis JH, Fulford AD, Considine RV, Mattes RD. Mastication of almonds: effects of lipid bioaccessibility, appetite, and hormone response. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:794–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li J, Zhang N, Hu L, Li Z, Li R, Li C, Wang S. Improvement in chewing activity reduces energy intake in one meal and modulates plasma gut hormone concentrations in obese and lean young Chinese men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:709–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Graaf C. Texture and satiation: the role of oro-sensory exposure time. Physiol Behav. Epub 2012. May 15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andrade AM, Greene GW, Melanson KJ. Eating slowly led to decreases in energy intake within meals in healthy women. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1186–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scisco JL, Muth ER, Dong Y, Hoover AW. Slowing bite-rate reduces energy intake: an application of the bite counter device. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1231–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Elia M, Cummings JH. Physiological aspects of energy metabolism and gastrointestinal effects of carbohydrates. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61 Suppl 1:S40–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bell EA, Castellanos VH, Pelkman CL, Thorwart ML, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake in normal-weight women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:412–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bell EA, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake across multiple levels of fat content in lean and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73:1010–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stubbs RJ, Johnstone AM, O'Reilly LM, Barton K, Reid C. The effect of covertly manipulating the energy density of mixed diets on ad libitum food intake in ‘pseudo free-living’ humans. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:980–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rolls BJ. The relationship between dietary energy density and energy intake. Physiol Behav. 2009;97:609–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Effects of energy density of daily food intake on long-term energy intake. Physiol Behav. 2004;81:765–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dikeman CL, Fahey GC. Viscosity as related to dietary fiber: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2006;46:649–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kristensen M, Jensen MG. Dietary fibres in the regulation of appetite and food intake. Importance of viscosity. Appetite. 2011;56:65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miles CW. The metabolizable energy of diets differing in dietary fat and fiber measured in humans. J Nutr. 1992;122:306–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miles CW, Kelsay JL, Wong NP. Effect of dietary fiber on the metabolizable energy of human diets. J Nutr. 1988;118:1075–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Baer DJ, Rumpler WV, Miles CW, Fahey GC., Jr Dietary fiber decreases the metabolizable energy content and nutrient digestibility of mixed diets fed to humans. J Nutr. 1997;127:579–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wisker E, Bach Knudsen KE, Daniel M, Feldheim W, Eggum BO. Digestibilities of energy, protein, fat and nonstarch polysaccharides in a low fiber diet and diets containing coarse or fine whole meal rye are comparable in rats and humans. J Nutr. 1996;126:481–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2002;287:2414–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pereira MA. Weighing in on glycemic index and body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:677–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2281–3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Heaton KW, Marcus SN, Emmett PM, Bolton CH. Particle size of wheat, maize, and oat test meals: Effects on plasma glucose and insulin responses and on the rate of starch digestion in vitro. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;47:675–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jenkins DJ, Wesson V, Wolever TM, Jenkins AL, Kalmusky J, Guidici S, Csima A, Josse RG, Wong GS. Wholemeal versus wholegrain breads: proportion of whole or cracked grain and the glycaemic response. BMJ. 1988;297:958–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liljeberg H, Granfeldt Y, Bjorck I. Metabolic responses to starch in bread containing intact kernels versus milled flour. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992;46:561–75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.O'Dea K, Nestel PJ, Antonoff L. Physical factors influencing postprandial glucose and insulin responses to starch. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:760–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kristensen M, Jensen MG, Riboldi G, Petronio M, Bugel S, Toubro S, Tetens I, Astrup A. Wholegrain vs. refined wheat bread and pasta. Effect on postprandial glycemia, appetite, and subsequent ad libitum energy intake in young healthy adults. Appetite. 2010;54:163–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liljeberg HG, Akerberg AK, Bjorck IM. Effect of the glycemic index and content of indigestible carbohydrates of cereal-based breakfast meals on glucose tolerance at lunch in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:647–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nilsson A, Granfeldt Y, Ostman E, Preston T, Bjorck I. Effects of gi and content of indigestible carbohydrates of cereal-based evening meals on glucose tolerance at a subsequent standardised breakfast. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:1092–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nilsson AC, Ostman EM, Holst JJ, Bjorck IM. Including indigestible carbohydrates in the evening meal of healthy subjects improves glucose tolerance, lowers inflammatory markers, and increases satiety after a subsequent standardized breakfast. J Nutr. 2008;138:732–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nilsson AC, Ostman EM, Knudsen KE, Holst JJ, Bjorck IM. A cereal-based evening meal rich in indigestible carbohydrates increases plasma butyrate the next morning. J Nutr. 2010;140:1932–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nilsson AC, Ostman EM, Granfeldt Y, Bjorck IM. Effect of cereal test breakfasts differing in glycemic index and content of indigestible carbohydrates on daylong glucose tolerance in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:645–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Priebe MG, Wang H, Weening D, Schepers M, Preston T, Vonk RJ. Factors related to colonic fermentation of nondigestible carbohydrates of a previous evening meal increase tissue glucose uptake and moderate glucose-associated inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:90–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.King DE, Mainous AG III, Lambourne CA. Trends in dietary fiber intake in the United States 1999–2008. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:642–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sleeth ML, Thompson EL, Ford HE, Zac-Varghese SE, Frost G. Free fatty acid receptor 2 and nutrient sensing: A proposed role for fibre, fermentable carbohydrates and short-chain fatty acids in appetite regulation. Nutr Res Rev. 2010;23:135–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Macfarlane S, Macfarlane GT. Regulation of short-chain fatty acid production. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, Wolvers D, Watzl B, Szajewska H, Stahl B, et al. Prebiotic effects: metabolic and health benefits. Br J Nutr. 2010;104 Suppl 2:S1–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Armougom F, Henry M, Vialettes B, Raccah D, Raoult D. Monitoring bacterial community of human gut microbiota reveals an increase in lactobacillus in obese patients and methanogens in anorexic patients. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kalliomäki M, Collado MC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Early differences in fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:534–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Million M, Maraninchi M, Henry M, Armougom F, Richet H, Carrieri P, Valero R, Raccah D, Vialettes B, Raoult D. Obesity-associated gut microbiota is enriched in lactobacillus reuteri and depleted in bifidobacterium animalis and methanobrevibacter smithii. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36:817–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 118.Nadal I, Santacruz A, Marcos A, Warnberg J, Garagorri M, Moreno LA, Martin-Matillas M, Campoy C, Marti A, Moleres A, et al. Shifts in clostridia, bacteroides and immunoglobulin-coating fecal bacteria associated with weight loss in obese adolescents. Int J Obes (Lond). 2009;33:758–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, et al. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature. 2009;457:480–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zhang H, DiBaise JK, Zuccolo A, Kudrna D, Braidotti M, Yu Y, Parameswaran P, Crowell MD, Wing R, Rittmann BE, et al. Human gut microbiota in obesity and after gastric bypass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:2365–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Duncan SH, Lobley GE, Holtrop G, Ince J, Johnstone AM, Louis P, Flint HJ. Human colonic microbiota associated with diet, obesity and weight loss. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1720–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Fava F, Gitau R, Griffin BA, Gibson GR, Tuohy KM, Lovegrove JA. The type and quantity of dietary fat and carbohydrate alter faecal microbiome and short-chain fatty acid excretion in a metabolic syndrome 'at-risk’ population. Int J Obes (Lond). Epub 2012. Mar 13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jumpertz R, Le DS, Turnbaugh PJ, Trinidad C, Bogardus C, Gordon JI, Krakoff J. Energy-balance studies reveal associations between gut microbes, caloric load, and nutrient absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;94:58–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wu GD, Chen J, Hoffmann C, Bittinger K, Chen YY, Keilbaugh SA, Bewtra M, Knights D, Walters WA, Knight R, et al. Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science. 2011;334:105–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Costabile A, Klinder A, Fava F, Napolitano A, Fogliano V, Leonard C, Gibson GR, Tuohy KM. Whole-grain wheat breakfast cereal has a prebiotic effect on the human gut microbiota: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Br J Nutr. 2008;99:110–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Moshfegh AJ, Friday JE, Goldman JP, Ahuja JK. Presence of inulin and oligofructose in the diets of americans. J Nutr. 1999;129:S1407–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.van Loo J, Coussement P, de Leenheer L, Hoebregs H, Smits G. On the presence of inulin and oligofructose as natural ingredients in the western diet. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 1995;35:525–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Cani PD, Lecourt E, Dewulf EM, Sohet FM, Pachikian BD, Naslain D, De Backer F, Neyrinck AM, Delzenne NM. Gut microbiota fermentation of prebiotics increases satietogenic and incretin gut peptide production with consequences for appetite sensation and glucose response after a meal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1236–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Parnell JA, Reimer RA. Weight loss during oligofructose supplementation is associated with decreased ghrelin and increased peptide YY in overweight and obese adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1751–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Verhoef SP, Meyer D, Westerterp KR. Effects of oligofructose on appetite profile, glucagon-like peptide 1 and peptide YY3–36 concentrations and energy intake. Br J Nutr. 2011;106:1757–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Howarth NC, Saltzman E, Roberts SB. Dietary fiber and weight regulation. Nutr Rev. 2001;59:129–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wanders AJ, van den Borne JJ, de Graaf C, Hulshof T, Jonathan MC, Kristensen M, Mars M, Schols HA, Feskens EJ. Effects of dietary fibre on subjective appetite, energy intake and body weight: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12:724–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC, Jr, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Bäckhed F, Ding H, Wang T, Hooper LV, Koh GY, Nagy A, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15718–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bäckhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:979–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ross AB. Present status and perspectives on the use of alkylresorcinols as biomarkers of wholegrain wheat and rye intake. J Nutr Metab. 2012;2012:462967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]