Abstract

Internet gaming addiction (IGA) is increasingly recognized as a widespread disorder with serious psychological and health consequences. Diminished white matter integrity has been demonstrated in a wide range of other addictive disorders which share clinical characteristics with IGA. Abnormal white matter integrity in addictive populations has been associated with addiction severity, treatment response and cognitive impairments. This study assessed white matter integrity in individuals with internet gaming addiction (IGA) using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI). IGA subjects (N=16) showed higher fractional anisotropy (FA), indicating greater white matter integrity, in the thalamus and left posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) relative to healthy controls (N=15). Higher FA in the thalamus was associated with greater severity of internet addiction. Increased regional FA in individuals with internet gaming addiction may be a pre-existing vulnerability factor for IGA, or may arise secondary to IGA, perhaps as a direct result of excessive internet game playing.

Keywords: internet addiction, internet gaming addiction, diffusion tensor imaging, thalamus, white matter, reward system

1. Introduction

Internet Gaming Addiction (IGA), a subtype of internet addiction disorder (IAD), is characterized by excessive or uncontrolled internet game use with negative consequences for aspects of psychological, social and/or work functioning (Young, 1998). Although internet addiction disorder is increasingly recognized as a widespread public health concern(Dong, Lu, Zhou, & Zhao, 2011b; Kim et al., 2010; Niemz, Griffiths, & Banyard, 2005; Young, 1998), the neurobiological underpinnings of this disorder have received relatively little study (Block, 2006; Dong, DeVito, Du, & Cui, 2012(in press); Dong, Lu, Zhou, & Zhao, 2010; Liu & Potenza, 2007; Yuan, Qin, Liu, & Tian, 2011).

Internet addiction disorder is often conceptualized as a ‘behavioral addiction’ since its proposed diagnostic criteria closely parallel those for substance use disorders and pathological gambling, although IAD is not formally included in the current edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders (DSM-IV) (Block, 2008). At least three subtypes of internet addiction have been identified, namely, excessive gaming, sexual pre-occupations, and e-mail/text messaging (Block, 2008). Although these variants share four defining characteristics (i.e., excessive use, withdrawal, tolerance, and negative repercussions) (Beard, 2001; Block, 2008), significant difference may exist among these IAD subtypes. In some countries, such as in China, internet gaming addiction (IGA) is the most prevalent form of IAD. Despite this, consensus is still lacking on the operational definition and diagnostic standards for IGA (Blaszczynski, 2008; Griffiths, 2008; Wood, 2008), leaving most researchers to define this specific IGA subgroup through more established general measures of internet addiction (Ko, Yen, Chen, Yeh, & Yen, 2009; van den Eijnden, Spijkerman, Vermulst, van Rooij, & Engels, 2010). In the present study, the IGA group is comprised of individuals who met general IAD criteria and report spending “most of their online time playing online games (>80%)”.

Since IAD appears to share clinical phenomena with substance use disorders and behavioral addictions (e.g., experience of euphoria, craving and/or withdrawal; development of tolerance) (Beard, 2001; Block, 2008; Grant, Potenza, Weinstein, & Gorelick, 2010), the neurobiological underpinnings of IAD are hypothesized to overlap with those of other addictive disorders. Disruptions to neural systems underlying reward processing and impulse control are thought to play crucial roles in the development and maintenance of drug addiction (Robbins & Everitt, 1999; Volkow, Fowler, Wang, & Goldstein, 2002). Several lines of evidence converge toward the hypothesis that drug addicts have a disrupted reward system and that addictive behaviors (e.g. drug taking, gambling) may serve as maladaptive means for compensating for this deficit (Robbins et al., 1999). Blunted neural response to monetary reward have been demonstrated in internet addiction and pathological gambling (de Ruiter et al., 2009; Reuter et al., 2005) (Dong, Huang, & Du, 2011a), suggesting behavioral addictions and substance dependence may be characterized by similar disruptions to reward circuitry. Despite serious mental health and social consequences of IGA in young adults, very few studies have directly assessed the whether the integrity of neural circuitry is disrupted in individuals who display problematic, under-controlled online game playing. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) assesses integrity of white matter microstructures by indexing the degree to which water diffusion deviates from isotropic diffusion in the white matter, with greater deviations from isotropic diffusion indicating more uniform directionality of water diffusion along the axon, implying greater white matter integrity. A fractional anisotropy (FA) value is calculating from the normalized standard deviation of axial eigenvalue (λ1) (i.e. a marker of diffusion along the axon) and radial eigenvalue (λ2)(i.e. a marker of diffusion perpendicular to the axon) (Alexander, Lee, Lazar, & Field, 2007; Xu, Li, Lin, Sinha, & Potenza, in press). White matter integrity has been shown to be disrupted in individuals with substance use disorders (Bora et al., 2012; Jacobus et al., 2009) and to relate to cognitive function (Piras, Caltagirone, & Spalletta, 2010; Tuch et al., 2005) (Takeuchi et al., 2011), substance-related symptoms (Clark, Chung, Thatcher, Pajtek, & Long, 2012) and addiction treatment outcome(Xu et al., 2010). Such relationships may reflect pre-existing individual differences that influence vulnerability to addiction or damage, which arises secondary to addictive disorders (de Laat et al., 2011; Stanek et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2010). The possibility of neuroplasticity improvements in white matter integrity is indicated by associations between greater white matter integrity with substance use abstinence (relative to active use)(Bell, Foxe, Nierenberg, Hoptman, & Garavan, 2011) and with prolonged cognitive or motor training (e.g., musical instrument training; abacus use; Boduk playing) (Hu et al., 2011; Imfeld, Oechslin, Meyer, Loenneker, & Jancke, 2009). The thalamus is generally believed to act as a relay between a variety of subcortical areas and the cerebral cortex, including the mesolimbic pathway (such as the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex). Integrity of these connections is essential for reward sensitivity, and IAD subjects show enhanced reward sensation (Dong et al., 2011a). Thus, investigate the pattern of thalamus is its connection to hippocampus and is important. Long-term internet game can be conceived of as a form of cognitive-motor ‘training’ and, as such, may be expected to result in white matter integrity improvements in thalamo-cortical circuitry important for reward processing, motor control and impulse control.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Subjects

This research, conducted in September 2010, was approved by the Human Investigations Committee of Zhejiang Normal University. All participants provided written informed consent. Participants were right-handed males (16 IGA, 15 healthy controls (HC)). IGA and HC groups did not significantly differ in age (IGA mean=22.2, SD=3.3 years; HC mean=21.6, SD=2.6 years; t(29) = 0.83, p >0.05). Only males were included due to higher IAD prevalence in men than women. Participants were university students and were recruited through advertisements. All participants underwent structured psychiatric interviews (M.I.N.I.) (Lecrubier et al., 1997) performed by an experienced psychiatrist with an administration time of approximately 15 minutes., The MINI was designed to meet the need for a short but accurate structured psychiatric interview for multicenter clinical trials and epidemiology studies. All participants were free of Axis I psychiatric disorders listed in M.I.N.I. Depression was further assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961) and no participants scoring higher than 5 were included. IGA and HC did not fulfill DSM-IV criteria for abuse or dependence of substances, including alcohol, although all IGA and HC participants reported having consumed alcohol in their lifetime. All participants were medication free and were instructed not to use any substances of abuse, including coffee, on the day of scanning. No participants reported previous experience with illicit drugs (e.g., cocaine, marijuana).

Internet addiction disorder, of which internet gaming addiction is one sub-type, was determined based on Young’s online internet addiction test (IAT) (Young, 2009) scores of 80 or higher (This cut-off is much stringent than the proposed 50 in Young’s criteria. Scored more than 80 in IAT mean ‘Your Internet usage is causing significant problems in your life’). The IAT was proved to be a valid and reliable instrument that can be used in classifying IAD. Factor analysis of the IAT revealed six factors-salience, excessive use, neglecting work, anticipation, lack of control and neglecting social life (Widyanto, Griffiths, & Brunsden, 2011; Widyanto & McMurran, 2004). All participants meeting criteria for internet addiction disorder fulfilled the sub-group classification of internet gaming addiction (IGA) by reporting spending most of their time online (>80%) playing online games. Young’s IAT consists of 20 items associated with online internet use including psychological dependence, compulsive use, withdrawal, related problems in school or work, sleep, family or time management. For each item, a graded response is selected from 1 = “Rarely” to 5 = “Always”, or “Does not Apply”. Scores over 50 indicate occasional or frequent internet-related problems and scores over 80 indicate significant internet addiction disorder-related life problems (www.netaddiction.com). HCs all scored lower than 30 on Young’s IAT (mean=16.3, SD=4.3).

Furthermore, all individuals were assessed using a Chinese “Internet addiction test” developed by the Beijing Military Region Central Hospital (Tao et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009). Internet addicts should satisfy several requirements. First, participants should spend more than six hours online everyday aside from work. Second, participants should show symptoms such as psychological dependence, abstinent reaction, compulsive use, social withdrawal, and negative effect on body and mental health for more than three months. The scale was tested in more than 1300 clinical trials, which proved to be valid in distinguishing IAD subjects (Wang et al., 2009). In the subtypes of the participants, all participants were internet gaming addicts (they spent most of their time playing online internet games).

2.2. Scanning Procedures

DTI data were acquired with a 3.0T Siemens Trio scanner. Diffusion sensitizing gradients were applied along 64 non-collinear directions using b-value image 0 and 1000 s/mm2 (TR=6800 ms, TE =93 ms, matrix=128* 128, FOV=256mm *256mm), 50 contiguous slices were acquired interleaved, and each slice was 2.5 mm thick. The entire scan lasted 12 minutes.

2.3. Image preprocessing

Eddy current distortions and head motion artifacts in the DTI dataset were corrected by applying affine alignment of each diffusion-weighted image to the non-diffusion image, using FMRIB’s diffusion toolbox (FSL, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) (Smith et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2004). Diffusion tensor elements were then estimated using the Stejskal and Tanner equation(Basser, Mattiello, & Lebihan, 1994). All eigenvalues and FA maps were calculated using DTIFit within the FMRIB Diffusion Toolbox in FSL. After alignment of each subject’s FA map to standard MNI152 space, tract-based spatial statistics for FA images was carried out using the package TBSS in FSL with the following steps. First, the mean FA image and its skeleton were created from the control and IGA groups in MNI152 space. Then, each subject’s FA map was projected onto the skeleton and voxel-wise statistics were performed across subjects for skeletonized FA images. An FA threshold of 0.2 was set to differentiate between white and grey matter FSL (Smith et al., 2006). In order to find the changes in thalamus, we used some specific ways (Zarei et al., 2010): First, voxels within the thalamus were classified according to the probability of their connectivity to the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex. Clusters of voxels were thresholded at 25% of the maximum probability of connectivity to their targets. Second, tractography between the hippocampus/medial prefrontal cortex (seeds), and the thalamus (target) were calculated to visualize their anatomical connections. Thirdly, we subtracted the group FA maps of the thalamus in MNI space.

Finally, voxel-wise statistics of FA were carried out to test for regional differences in white matter tract integrity between the IGA and HC groups. Independent two-sample t-tests were administered at each voxel using the randomize procedure in FSL with 5,000 permutations. Corrections for multiple comparisons were carried out using threshold-free cluster enhancement method with a false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of p<0.05 for between-group differences(Smith & Nichols, 2009). Mean FA values were extracted from the clusters showing significant between-group differences and were included in correlations with Young’s IAT scores within the IGA group only.

3. Results

3.1. Voxel-wise statistics of FA

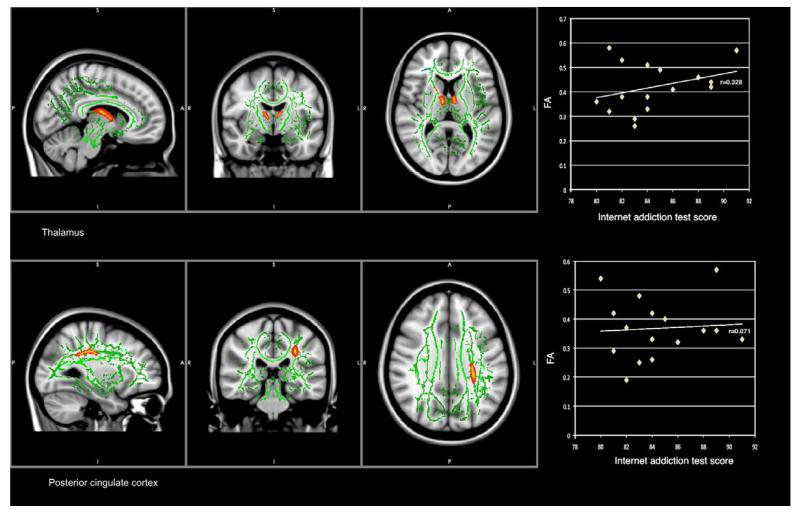

The IGA group showed higher FA values in two brain regions relative to the HC group: (1) bilateral thalamus, and (2) left posterior cingulate cortex (Figure 1). There were no regions with significantly lower FA in the IGA group relative to the HC group.

Figure 1.

MNI (Montreal Neurological Institute) T1 template is used to localize brain regions showing significant correlations. Green color on the T1 image shows ‘group mean_FA_skeleton’. Only clusters surviving correction for multiple comparisons of voxel-wise whole brain analysis are shown on brain images. ‘Tbss_fill’ command was used to make the figure easier to visualize. Higher FA was found in thalamus and posterior cingulate cortex in the IGA group relative to healthy controls. Scatter-plots show correlations between internet addiction test scores (x axis) and mean values of FA in thalamus (top) and PCC (bottom) (y axis), calculated from all voxels within clusters that survived corrections for multiple comparisons in the IGA versus healthy control group analyses.

3.2. Relations between regional FA value and IAT score

In the IGA group, internet addiction severity scores (i.e. Young’s IAT) were positively correlated with the average FA in the thalamus cluster (r= 0.328, p<0.05), but not the posterior cingulate cortex cluster (r=0.071, p>0.05). See Figure 1.

4. Discussion

DTI permits voxel-wise comparisons of white matter regions at the whole brain level. Increased or decreased FA value is usually interpreted as reflecting richer or poorer white matter integrity, respectively (Alexander et al., 2007; Xu et al., in press). Relative to healthy controls, IGA subjects show increased FA values in thalamus and the left PCC. In addition, this study revealed an association between greater severity of internet addiction, as measured by Young’s IAT score, and better white matter integrity in the thalamus (i.e. higher FA).

4.1. Abnormal thalamo-cortical circuitry in IGA subjects: Implications for reward sensitivity

In the present study, IGA subjects show higher FA value in the thalamus than healthy controls. Previous studies have found the thalamus to play an important role in reward processing (Rieck, Ansari, Whetsell, Deutch, & Kessler, 2004; Yu, Gupta, & Yin, 2010) and goal-directed behaviors, alongside many other cognitive and motor functions (Corbit, Muir, & Balleine, 2003). Thalamus lesions have also been reported to disrupt the acquisition of stimulus-reward associations(Gaffan & Murray, 1990; Gaffan, Murray, & Fabre-Thorpe, 1993) Auto-radiographic studies suggest that the thalamic nuclei may integrate activity by conveying information to dopamine adapter systems involved in reward(Rieck et al., 2004).

Thus, increased thalamus integrity in the IGA group, and associations between greater FA in the thalamus and higher severity of internet addiction may be consistent with enhanced reward sensitivity systems in IGA. These abnormalities may serve as a vulnerability factor for the development of IGA or may arise as a neuroplastic change in response to excessive internet game playing in the context of IAD. This interpretation may be consistent with the enhanced reward sensitivity observed in a separate group of internet addicted individuals in an event-related fMRI study (Dong et al., 2011a).

The logic of hypothesizing a potential role for a enhanced reward system in IGA subjects may be clarified by specifying features of online games: First players build an avatar, which may differ significantly from their own personality, in a virtual world in which they can accomplish tasks(Van Rooij, Schoenmakers, Vermulst, Van den Eijnden, & Van de Mheen, 2010). The virtual world provides players with more reward than punishment experiences, for even when players failed in their tasks, they can simply begin again with minimal repercussions. Second, online internet games cannot be completed in a set time because of the regular introduction of new contents, which require players to continue playing to ‘keep up’ with the game (Charlton & Danforth, 2007). Thus, internet games may be addictive (i.e. ’habit-forming’) due to these characteristics which induce operant conditioning via variable-ratio reinforcement schedules, which are highly effective conditioning paradigms (Wallace, 1999). As players reach higher levels of difficulty in the game, more cooperation is required with other players to succeed, which provides social reinforcement (Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2000). These features of internet games may drive players to pursue more rewarding/winning experiences by spending still more time playing online games.

4.2. Enhanced visual and spatial processing system

Higher FA value was also observed in the PCC in the IGA group relative to healthy controls. Previous studies have shown that the PCC plays a role in visual-spatial orientation. For instance, functional imaging studies have indicated that the PCC is part of a network that mediates spatial navigation (Berthoz, 1997; Ghaem et al., 1997); single neuron electrophysiology studies in alert monkeys while assessing large visual field patterns show activity in PCC neurons was tightly linked to the position of the eye in the orbit and the direction and amplitude of saccadic eye movements (Olson, Musil, & Goldberg, 1996). In addition, previous studies have shown that action games can modify visual processing (see a review of (Riesenhuber, 2004)). In fact, video games are now employed as a useful tool in training visual skills (see review of (Achtman, Green, & Bavelier, 2008)). As such, enhanced white matter integrity in visual and spatial processing system (e.g. PCC) may arise secondary to extended online game playing.

5. Limitations

Although his study revealed several important findings that may deepen our understanding about internet gaming addiction, several limitations should be considered. Firstly, although this study focused on the internet gaming subgroup of IAD, no direct comparisons were made with other IAD subgroups. So the degree to which the results would extend to other IAD subgroups or is specific to IGA, is not known. Secondly, the present study was cross-sectional., So abnormalities in white matter integrity of the IGA group may have represented pre-existing vulnerabilities or changes as a result of extensive online playing or other related IGA behaviors/symptoms.. Thirdly, all participants in present study were male university students, so further studies should assess whether these results extend to women and different age groups. Finally, the lack of an established diagnostic tool for internet gaming addiction limits the ability to draw direct comparisons across studies of IGA samples.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Science Foundation of China (30900405). EED is supported by a grant (K12-DA-031050) from NIDA, ORWH, NIH (OD) and NIAAA. The author thanks Qilin Lu and Yuzheng Hu for their help in data collecting and analyzing.

Role of funding source

The funder had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict in this manuscript.

References

- Achtman RL, Green CS, Bavelier D. Video games as a tool to train visual skills. Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience. 2008;26:435–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander AL, Lee JE, Lazar M, Field AS. Diffusion tensor imaging of the brain. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:316–329. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Mattiello J, Lebihan D. Estimation of the Effective Self-Diffusion Tensor from the Nmr Spin-Echo. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Series B. 1994;103:247–254. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard KW, E M. Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2001;4:377–383. doi: 10.1089/109493101300210286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An Inventory for Measuring Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RP, Foxe JJ, Nierenberg J, Hoptman MJ, Garavan H. Assessing white matter integrity as a function of abstinence duration in former cocaine-dependent individuals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthoz A. Parietal and hippocampal contribution to topokinetic and topographic memory. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences. 1997;352:1437–1448. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaszczynski A. Commentary: A Response to “Problems with the Concept of Video Game ”Addiction“: Some Case Study Examples”. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2008;6:179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Block JJ. Prevalence Underestimated in Problematic Internet Use Study. CNS Spectr. 2006;12:14–15. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900020459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block JJ. Issues for DSM-V: internet addiction. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:306–307. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora E, Yucel M, Fornito A, Pantelis C, Harrison BJ, Cocchi L, Pell G, Lubman DI. White matter microstructure in opiate addiction. Addiction Biology. 2012;17:141–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton JP, Danforth IDW. Distinguishing addiction and high engagement in the context of online game playing. Computers in Human Behavior. 2007;23:1531–1548. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Chung T, Thatcher DL, Pajtek S, Long EC. Psychological dysregulation, white matter disorganization and substance use disorders in adolescence. Addiction. 2012;107:206–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbit LH, Muir JL, Balleine BW. Lesions of mediodorsal thalamus and anterior thalamic nuclei produce dissociable effects on instrumental conditioning in rats. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;18:1286–1294. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Laat KF, Tuladhar AM, van Norden AGW, Norris DG, Zwiers MP, de Leeuw FE. Loss of white matter integrity is associated with gait disorders in cerebral small vessel disease. Brain. 2011;134:73–83. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ruiter MB, Veltman DJ, Goudriaan AE, Oosterlaan J, Sjoerds Z, van den Brink W. Response Perseveration and Ventral Prefrontal Sensitivity to Reward and Punishment in Male Problem Gamblers and Smokers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1027–1038. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G, DeVito E, Du X, Cui Z. Impaired Inhibitory Control in ‘Internet Addiction Disorder’: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.02.001. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G, Huang J, Du X. Enhanced reward sensitivity and decreased loss sensitivity in Internet addicts: An fMRI study during a guessing task. J Psychiatr Res. 2011a doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G, Lu Q, Zhou H, Zhao X. Impulse inhibition in people with internet addiction disorder: electrophysiological evidence from a Go/NoGo study. Neurosci Lett. 2010;485:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong G, Lu Q, Zhou H, Zhao X. Precursor or sequela: pathological disorders in people with internet addiction disorder. PLoS One. 2011b;6:e14703. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffan D, Murray EA. Amygdalar interaction with the mediodorsal nucleus of the thalamus and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex in stimulus-reward associative learning in the monkey. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3479–3493. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-11-03479.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffan D, Murray EA, Fabre-Thorpe M. Interaction of the amygdala with the frontal lobe in reward memory. Eur J Neurosci. 1993;5:968–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1993.tb00948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaem O, Mellet E, Crivello F, Tzourio N, Mazoyer B, Berthoz A, Denis M. Mental navigation along memorized routes activates the hippocampus, precuneus, and insula. Neuroreport. 1997;8:739–744. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199702100-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Potenza MN, Weinstein A, Gorelick DA. Introduction to Behavioral Addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:233–241. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.491884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths M. Videogame Addiction: Further Thoughts and Observations. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2008;6:182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Hu YZ, Geng FJ, Tao LX, Hu N, Du FL, Fu KA, Chen FY. Enhanced White Matter Tracts Integrity in Children With Abacus Training. Human Brain Mapping. 2011;32:10–21. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imfeld A, Oechslin MS, Meyer M, Loenneker T, Jancke L. White matter plasticity in the corticospinal tract of musicians: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroimage. 2009;46:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobus J, McQueeny T, Bava S, Schweinsburg BC, Frank LR, Yang TT, Tapert SF. White matter integrity in adolescents with histories of marijuana use and binge drinking. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 2009;31:349–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Lau CH, Cheuk K-K, Kan P, Hui HLC, Griffiths SM. Predictors of heavy Internet use and associations with health-promoting and health risk behaviors among Hong Kong university students. Journal of Adolescence. 2010;33:215–220. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CS, Yeh YC, Yen CF. Predictive Values of Psychiatric Symptoms for Internet Addiction in Adolescents A 2-Year Prospective Study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:937–943. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Harnett Sheehan K, Janavs J, Dunbar GC. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity according to the CIDI. European Psychiatry. 1997;12:224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Liu T, Potenza MN. Problematic Internet Use: Clinical Implications. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:453–466. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900015339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morahan-Martin J, Schumacher P. Incidence and correlates of pathological Internet use among college students. Computers in Human Behavior. 2000;16:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Niemz K, Griffiths M, Banyard P. Prevalence of pathological Internet use among university students and correlations with self-esteem, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ), and disinhibition. CyberPsychology and Behavior. 2005;8:562–570. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2005.8.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson CR, Musil SY, Goldberg ME. Single neurons in posterior cingulate cortex of behaving macaque: Eye movement signals. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1996;76:3285–3300. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.76.5.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piras F, Caltagirone C, Spalletta G. Working Memory Performance and Thalamus Microstructure in Healthy Subjects. Neuroscience. 2010;171:496–505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter J, Raedler T, Rose M, Hand I, Glascher J, Buchel C. Pathological gambling is linked to reduced activation of the mesolimbic reward system. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:147–148. doi: 10.1038/nn1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieck RW, Ansari MS, Whetsell WO, Deutch AY, Kessler RM. Distribution of dopamine D-2-like receptors in the human thalamus: Autoradiographic and PET studies. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:362–372. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesenhuber M. An action video game modifies visual processing. Trends in Neurosciences. 2004;27:72–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Drug addiction: bad habits add up. Nature. 1999;398:567–570. doi: 10.1038/19208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TEJ. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang YY, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S208–S219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek KM, Grieve SM, Brickman AM, Korgaonkar MS, Paul RH, Cohen RA, Gunstad JJ. Obesity Is Associated With Reduced White Matter Integrity in Otherwise Healthy Adults. Obesity. 2011;19:500–504. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Taki Y, Sassa Y, Hashizume H, Sekiguchi A, Fukushima A, Kawashima R. Verbal working memory performance correlates with regional white matter structures in the frontoparietal regions. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:3466–3473. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YY, Lu QL, Geng XJ, Stein EA, Yang YH, Posner MI. Short-term meditation induces white matter changes in the anterior cingulate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:15649–15652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011043107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao R, Huang X, Wang J, Liu C, Zhang H, Xiao L, Yao S. A proposed criterion for clinical diagnosis of internet addiction. Medical Journal of Chinese People’s Liberation Army. 2008;33:1188–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Tuch DS, Salat DH, Wisco JJ, Zaleta AK, Hevelone ND, Rosas HD. Choice reaction time performance correlates with diffusion anisotropy in white matter pathways supporting visuospatial attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12212–12217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407259102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Eijnden RJJM, Spijkerman R, Vermulst AA, van Rooij TJ, Engels RCME. Compulsive Internet Use Among Adolescents: Bidirectional Parent-Child Relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:77–89. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9347-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, Vermulst AA, Van den Eijnden RJ, Van de Mheen D. Online video game addiction: identification of addicted adolescent gamers. Addiction. 2010;106:205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang G-J, Goldstein RZ. Role of Dopamine, the Frontal Cortex and Memory Circuits in Drug Addiction: Insight from Imaging Studies. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2002;78:610–624. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace P. The psychology of the Internet. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Tao R, Niu Y, Chen Q, Jia J, Wang X, Kong Q, Tian C. Preliminarily Proposed Diagnostic Criteria of Pathological Internet Use. Chinese Mental Health Journal. 2009;23:890–894. [Google Scholar]

- Widyanto L, Griffiths MD, Brunsden V. A psychometric comparison of the Internet Addiction Test, the Internet-Related Problem Scale, and self-diagnosis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2011;14:141–149. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2010.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widyanto L, McMurran M. The psychometric properties of the internet addiction test. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2004;7:443–450. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2004.7.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood R. Problems with the Concept of Video Game “Addiction”: Some Case Study Examples. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 2008;6:169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Li Y, Lin H, Sinha R, Potenza MN. Body mass index correlates negatively with white matter integrity in the fornix and corpus callosum: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Hum Brain Mapp. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21491. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JS, DeVito EE, Worhunsky PD, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Potenza MN. White Matter Integrity is Associated with Treatment Outcome Measures in Cocaine Dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:1541–1549. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young K. Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. CyberPsychology and Behavior. 1998;1:237–244. [Google Scholar]

- Young KS. Internet Addiction Test (IAT) used in 2009. www.netaddiction.net.

- Yu C, Gupta J, Yin HH. The role of mediodorsal thalamus in temporal differentiation of reward-guided actions. Front Integr Neurosci. 2010;4 doi: 10.3389/fnint.2010.00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan K, Qin W, Liu Y, Tian J. Internet addiction: Neuroimaging findings. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:637–639. doi: 10.4161/cib.17871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarei M, Patenaude B, Damoiseaux J, Morgese C, Smith S, Matthews PM, Barkhof F, Rombouts SA, Sanz-Arigita E, Jenkinson M. Combining shape and connectivity analysis: an MRI study of thalamic degeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2010;49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]