Abstract

Objective

To determine the effect of contact with a podiatrist on the occurrence of Lower Extremity Amputation (LEA) in people with diabetes.

Design and data sources

We conducted a systematic review of available literature on the effect of contact with a podiatrist on the risk of LEA in people with diabetes. Eligible studies, published in English, were identified through searches of PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE and Cochrane databases. The key terms, ‘podiatry’, ‘amputation’ and ‘diabetes’, were searched as Medical Subject Heading terms. Reference lists of selected papers were hand-searched for additional articles. No date restrictions were imposed.

Study selection

Published randomised and analytical observational studies of the effect of contact with a podiatrist on the risk of LEA in people with diabetes were included. Cross-sectional studies, review articles, chart reviews and case series were excluded. Two reviewers independently assessed titles, abstracts and full articles to identify eligible studies and extracted data related to the study design, characteristics of participants, interventions, outcomes, control for confounding factors and risk estimates.

Analysis

Meta-analysis was performed separately for randomised and non-randomised studies. Relative risks (RRs) with 95% CIs were estimated with fixed and random effects models as appropriate.

Results

Six studies met the inclusion criteria and five provided data included in meta-analysis. The identified studies were heterogenous in design and included people with diabetes at both low and high risk of amputation. Contact with a podiatrist did not significantly affect the RR of LEA in a meta-analysis of available data from randomised controlled trials (RCTs); (1.41, 95% CI 0.20 to 9.78, 2 RCTs) or from cohort studies; (0.73, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.33, 3 Cohort studies with four substudies in one cohort).

Conclusions

There are very limited data available on the effect of contact with a podiatrist on the risk of LEA in people with diabetes.

Keywords: Vascular surgery

Article summary.

Article focus

People with diabetes are at increased risk of Lower Extremity Amputation (LEA). As the prevalence of diabetes escalates worldwide, it is anticipated that there will be an increase in the number of LEAs.

It is assumed that contact with a podiatrist prevents the occurrence of an LEA.

This systematic review aims to determine from available literature the documented effect of contact with a podiatrist on the occurrence of an LEA in people with diabetes.

Key messages

Very limited data are available and the authors conclude that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether contact with a podiatrist has an effect on the risk of LEA in people with diabetes.

Some existing studies suggest that contact with a podiatrist has a positive effect on shorter-term outcomes including patient knowledge of foot care and ulcer recurrence.

Further research on the long-term outcome of LEA is warranted.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first systematic review which investigates if contact with a podiatrist prevents the occurrence of an LEA in people with diabetes.

Failure to demonstrate an effect on this long-term outcome is most likely due to limitations of available studies.

Limitations include that studies in this systematic review looked at different sample populations ranging from patients with low baseline risk to patients with active disease. Also, included randomised controlled trials were underpowered to detect a significant difference for the outcome of LEA.

Introduction

A worldwide diabetes epidemic is unfolding.1 Diabetes is associated with a significantly increased risk of Lower Extremity Amputation (LEA). LEA rates vary between populations with estimates ranging from 46 to 9600/105 people with diabetes.2 A number of factors influence the occurrence of an LEA in people with diabetes; including hypertension, obesity and hyperglycaemia.3 4 In the foot, previous ulceration, infection and ischaemia are proven risk factors.5 Nearly 85% of amputations begin as foot ulcers among persons with diabetes.6 Protective factors include control of clinical parameters and screening to identify those people at high risk and many LEAs are preventable.7 8 The effects of clinical and sociodemographic risk factors on the occurrence of an LEA have been well documented in people with diabetes.9–12

In 2008, a task force report by the Foot Care Interest Group of the American Diabetes Association, which included podiatrists, stated that all people with diabetes should be assigned to a foot risk category.13 These categories were designed to direct referral to and subsequent therapy by a speciality clinician or team but did not refer specifically to the role of podiatry. Recent guidelines from Scotland outline a diabetic-risk stratification and triage tool, highlighting which people need podiatry referral. According to these guidelines, all patients classified as moderate risk (ie, at least one risk factor present), severe risk or with active disease require podiatry review.14 Podiatry is practiced as a specialty in many countries and in many English-speaking countries, the older term of ‘chiropodist’ may still be used. According to the National Health Service in the UK, there is no difference between a chiropodist and a podiatrist.15 It is assumed that podiatrists prevent LEAs by treating existing disease and educating people with diabetes on proper foot care. However, the effect of patient contact with a podiatrist on the risk of LEA in people with diabetes is unproven.

Two previous Cochrane reviews by Dorresteijn et al16 17 have looked first at the effect of an integrated care approach and second, the effect of patient education on the outcome of LEA in people with diabetes. The first of these reviews found no high-quality evidence evaluating an integrated care approach and insufficient evidence of benefit in preventing diabetic foot ulceration.16 The second review, updated in 2012, concluded that there is insufficient robust evidence that limited patient education alone is effective in achieving clinically relevant reductions in ulcer and LEA incidence.17 Individual patient contact with a podiatrist was not examined as an intervention in either review. Thus, the objective of the present systematic review of the published literature is to examine the effect of contact with a podiatrist on risk of LEA in people with diabetes.

Methods

The research question, inclusion and exclusion criteria and proposed methods of analysis were specified in advance and documented in a protocol (attached as a supplementary file).

Search Strategy

PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE (Excerpta Medica) and Cochrane databases were searched to identify relevant studies published up to and including 25 September 2011. The key terms, ‘podiatry’, ‘amputation’ and ‘diabetes’, were searched as Medical Subject Heading terms. Randomised and observational studies, published in English, which reported the effect of contact with a podiatrist on risk of LEA in people with diabetes (type 1 or 2), were included. No date restrictions were imposed. Cross-sectional studies, review articles, non-systematic reviews, chart reviews and case series were excluded. A manual search for references cited in relevant articles was performed. All potentially eligible studies were independently reviewed by two authors (CMB and PMK).

Data abstraction and quality assessment:

Using a standardised data collection form, two reviewers (CMB and PMK) independently abstracted information on the study design, year of study, characteristics of participants, interventions and outcomes, control for potential confounding factors and risk estimates. A modified version of a checklist developed by Downs and Black for assessing the methodological quality of both randomised and non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions was used to critically appraise the studies in this review.18 Inconsistencies between reviewers were discussed and resolved through consensus.

Statistical analysis

Review Manager Software V.5 (Revman 5.0; the Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, England) and STATA V.12IC were used for statistical analysis. The relative risk (RR) with 95% CI was recorded for included studies. One study presented individual results for four various stages of disease so this study was analysed as four substudies. Meta-analysis was performed separately for randomised and non-randomised studies, using either the fixed or random effects model as appropriate. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with Cochran's Q statistic. Cochran's Q is computed by summing the squared deviations of each study's estimate from the overall meta-analytic estimate, weighting each study's contribution in the same manner as in the meta-analysis. p Values were obtained by comparing the statistic with a χ² distribution with k−1° of freedom (where k is the number of studies).19 To assess publication bias, a funnel plot of the overall estimate and its SE was derived.

Results

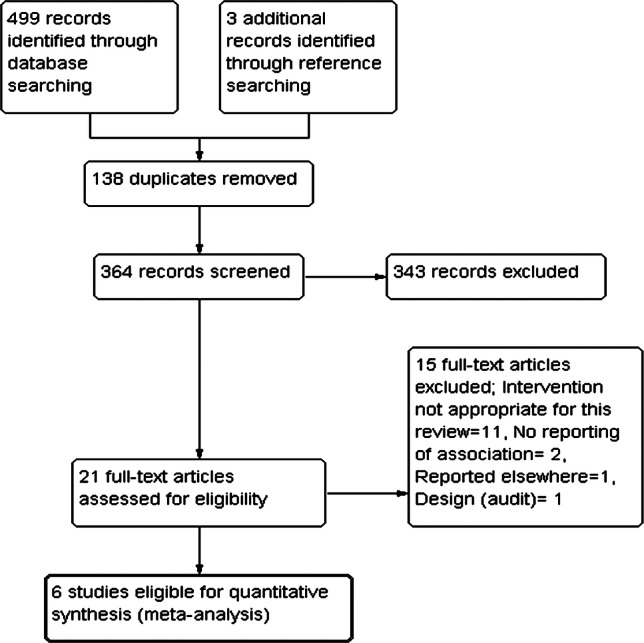

Four hundred and ninety-nine titles were retrieved from searches of electronic databases. Duplicates (138) were removed and 361 titles/abstracts were reviewed. Eighteen papers were considered for review after initial screening of titles and abstracts. Three further studies were identified as potentially eligible from reference checking. After reviewing the full text articles, six studies met the inclusion criteria; two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and four cohort studies (figure 1).20 Studies were excluded because of study design for example, chart review/audit; intervention for example, contact with a multidisciplinary team instead of contact with a podiatrist; or in one case, the study was described in another article already included in this systematic review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart: selection of studies for inclusion in review.

Table 1 describes the included studies according to study design, participants, interventions and outcomes. Quality of included studies was assessed and all studies were deemed of suitable quality for inclusion (tables 2 and 3). Risk of foot disease at baseline was assessed using the Diabetic foot risk stratification and triage system from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines (see online supplementary appendix 1).14 Results of included studies are presented in table 4.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Study (author, country, year) | Type of study | Participants | Interventions | Source of data used in study | Length of follow-up | Baseline risk as per diabetic foot risk stratification14 | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ronnemaa, Finland, 199722 16 | RCT | 530 patients with diabetes randomised Intervention: 267 Control: 263 |

Intervention: 45 min individual patient education Podiatric care visits as necessary Control: Written information |

Clinical report forms | 1 and 7 years | Low | Primary: Patient knowledge about foot care Secondary: ulcer incidence Amputation rate |

| Plank, Austria, 200323 | RCT | 91 patients with diabetes randomised Intervention: 47 Control: 44 |

Intervention: Chiropodist visit at least once a month Control: chiropodist treatment not specifically recommended |

Clinical report forms | 386 days (368–424, 25th–75th percentile) | High (healed foot ulcers) | Primary: Recurrence rate of ulcers Secondary: Amputation rate Death |

| Sowell, USA, 199924 | Cohort | 255 256 with diabetes or PVD or gangrene followed over time | Intervention: Podiatric Medical care—receipt of any M0101 services Comparison: Did not receive podiatry (M0101) services |

Medicare claims database | 1 year | Unknown | Number of amputations |

| Lipscombe, Canada, 200337 | Cohort | 132 patients with diabetes on peritoneal dialysis (PD) | Intervention: Assessment, education and footcare by chiropody | Medical charts | 3 years | High | Number of amputations |

| Lavery, USA, 201021 | Cohort | 300 high-risk patients with diabetes 150 with an ulcer history 150 on dialysis followed over time |

Intervention: Podiatry services—number of visits to podiatrist for prevention, ulcer treatment of other pathology | Claims data and electronic medical records | 30 months | High (history of foot ulcer) | Amputation rate Ulcer incidence |

| Sloan, UK, 201038 | Cohort | 189 598 patients with diabetes followed over time Participants grouped into different stages (1–4) of disease depending on severity of symptoms and signs |

Intervention: Care provided by podiatrist Comparison: Care provided by ‘other health professional’—GP/internist/endocrinologist/nurse/physician assistant |

Medicare claims database | 6 years | Stage 1: Moderate Stage 2: High Stage 3: Active Stage 4: Active |

Amputation rate |

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 2.

Quality assessment of included RCTs

| Study (author, country, year) | Type of study | Base population | Randomisation | Blinding | Confounding | Losses to follow-up | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ronnemaa, Finland, 199722 | RCT | Community-based care in Finland, receiving antidiabetic drug treatment from the national drug reimbursement register | Randomisation performed separately for men/women and patients </> 20 years. Method of randomisation not described | Outcome assessor blinded to baseline characteristics but no further information on blinding provided | Baseline characteristics not described | Follow-up completed by 63% of patients in intervention group and 62% patients in control group at 7 years | No intention to treat analysis undertaken |

| Plank, Austria, 200323 | RCT | All in routine outpatient care at hospital diabetic foot clinic in Austria | Subjects were assigned a patient number in ascending order and randomly allocated to the intervention or control group | Allocation concealment ensured | Similar baseline characteristics | All patients followed up | Intention to treat and per protocol analysis |

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Table 3.

Quality assessment of included cohort studies

| Study (author, country, year) | Type of study | Base population | Confounding | Losses to follow-up | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sowell, USA, 199924 | Cohort | All Medicare population at risk for lower extremity amputation in 1993–1994 | Not addressed—only looked at 1 variable—acknowledged as a limitation | No losses to follow-up | Amputation incidence rates with and without exposure to podiatry |

| Lipscombe, Canada, 200337 | Cohort | Patients in Peritoneal Dialysis program at University Health Network, between January 1997 and December 1999 | Data on confounding variables collected | No losses to follow-up | Descriptive stats |

| Lavery, USA, 201021 | Cohort | Patients with diabetes attending Scott and White Health Plan, Texas, USA | Data on confounding variables collected | 150 consecutive patients with at least 30 months follow-up from the time of diagnosis recruited so no losses to follow-up | Descriptive stats |

| Sloan, UK, 201038 | Cohort | All individuals with a DM-related LEC diagnosis between 1994 and 2001 | Data on confounding variables collected | No losses to follow-up | HRs adjusted for Medicare expenditures from care received from non-study health professionals |

Table 4.

Results of included studies

| Study (author, country, year) | Type of study | Primary outcome | Baseline risk as per diabetic foot risk stratification14 | Relative risk of amputation with contact with a podiatrist compared with no contact with a podiatrist |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ronnemaa, Finland, 199722 16 | RCT |

Diabetes-related amputation: One year follow-up: Intervention: 0 Control: 0 7-years follow-up: Intervention: 1 Control: 0 |

Low | 2.96 |

| Plank, Austria, 200323 | RCT |

Diabetes-related amputation: 1-year follow-up: Intervention: 2 Control: 1 |

High (healed foot ulcers) | 0.92 |

| Sowell, USA, 199924 | Cohort |

Amputation related to diabetes/gangrene/PVD 1-year follow-up: Intervention: 20 Control: 130 |

Unknown | 0.25 |

| Lipscombe, Canada, 200337 | Cohort |

Diabetes-related amputation: Amputation during any of the 3 years of the study: Intervention: 11 Control: 4 |

High | 2.16 |

| Lavery, USA, 201021 | Cohort |

Diabetes-related amputation: Actual number of amputations not outlined Amputation incidence density: 58.7 in Dialysis Group per 1 000 person-years 13.1 in Ulcer Group per 1 000 person-years |

High (history of foot ulcer) | Unknown |

| Sloan, UK, 201038 | Cohort |

Diabetes-related amputation: 6-year follow-up: actual number of amputations not outlined |

Stage 1: Moderate Stage 2: High Stage 3: Active Stage 4: Active |

Stage 1 disease : 2.20 Stage 2 disease : 0.85 Stage 3 disease : 0.44 Stage 4 disease : 0.36 |

RCT, randomised controlled trial.

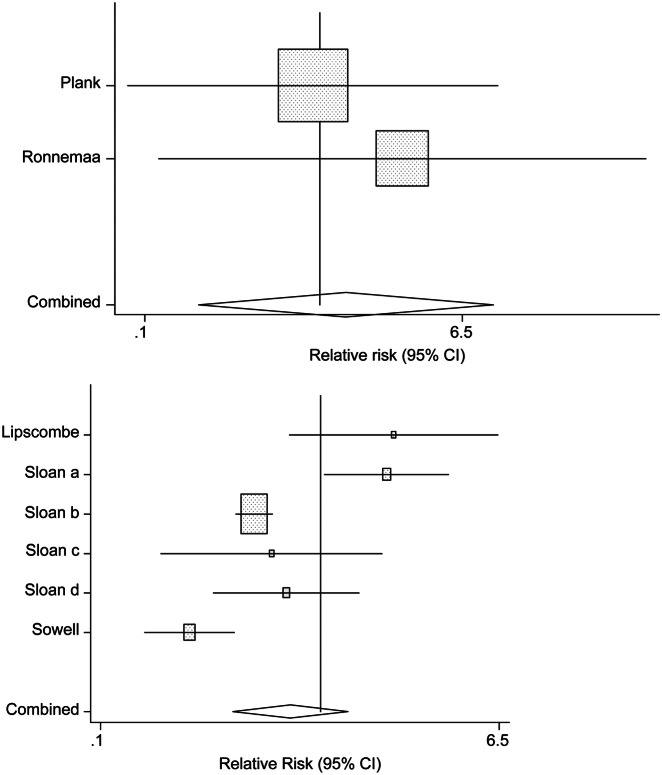

Results from available studies were pooled together in separate meta-analyses for RCTs and observational studies. Five of these studies provided sufficient data to allow meta-analysis. For RCTs, the fixed effects model was applied (Q=0.328, p=0.567) and for cohort studies, the random effects model is reported as there was evidence of significant heterogeneity between the cohort studies (Q=32.698, p=0.000). Meta-analysis of the two RCTs yielded an insignificant pooled RR of 1.41 (95% CI 0.20 to 9.78) while meta-analysis of the cohort studies also yielded an insignificant pooled RR of 0.73 (95% CI 0.39 to 1.33; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (top) and cohort studies (bottom) with the intervention of contact with a podiatrist on left side of plot.

Data required for inclusion in the meta-analysis was unavailable for one eligible study. Lavery et al compared people with diabetes on dialysis and people with diabetes with a history of a healed ulcer. During a 30-month evaluation period, only 30% of patients from both groups combined were seen for preventative care prior to ulceration. The amputation incidence density was high in both groups (dialysis group 58.7 and ulcer group 13.1/1000 person-years).21 However, it was not possible to extract the LEA event rate in those who did or did not have contact with a podiatrist.

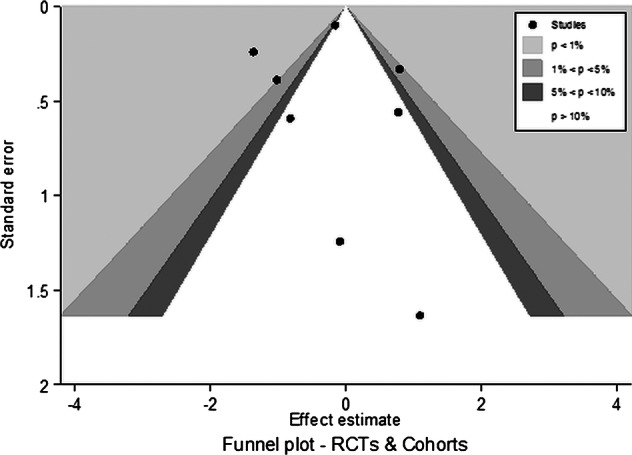

Visual inspection of the funnel plot produced for the included studies shows no strong evidence of publication bias (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Funnel plot of included studies (randomised controlled trials and cohort studies).

Discussion

In this systematic review, we conclude that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether contact with a podiatrist has an effect on LEA in people with diabetes.

Strengths and limitations of this review

This is the first systematic review that the authors are aware of that investigates if contact with a podiatrist prevents the occurrence of an LEA in patients with diabetes. A thorough literature search examining multiple databases was undertaken and six studies with two different study designs were included. While individual study design meta-analysis was performed in an effort to pool the available data, we acknowledge that heterogeneity exists between studies included in the meta-analysis in terms of baseline diabetic foot risk and type of intervention.

Included studies looked at different sample populations ranging from patients with low baseline risk to patients with active disease. For example, Ronnemaa et al22 recruited patients with diabetes from the national drug imbursement register in Finland which is representative of the total population with diabetes. However, Plank et al23 recruited patients with diabetes from a tertiary referral centre which represents a population of patients with diabetes that have developed complications requiring referral to a tertiary centre. In five of the six included studies, the population at risk were patients with diabetes. However, Sowell et al24 examined a population mix of patients with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease (PVD) and gangrene. It was decided to include this study due to the dearth of research in this area. This difference in populations studied between the Sowell paper and the other five studies needs to be highlighted as a limitation in this review.

The diabetic foot risk of the participants at baseline (low-active) reflects the different treatment settings at recruitment and highlights heterogeneity amongst the studies (table 1). Cochran's Q statistic was used to assess heterogeneity. For RCTs, the fixed effects model was appropriate but this meta-analysis is limited as there are only two included studies. For cohort studies, the Q statistic of 32.698 (p=0.000) indicated that strong heterogeneity existed so the random effects model was applied to account for both random variability and the variability in effects among the studies. However, use of the random effects model limits the conclusions that can be drawn from the meta-analysis.25 ‘A priori’ sensitivity analyses were planned for different levels of baseline risk but there were insufficient data.

Sources of potential bias should be considered in relation to the observational studies. Although information was collected on potential confounders in many of the included observational studies, the analyses were not adjusted for potential confounders and sources of bias. Clinical practices may vary per individual and per location. Guidelines have been recently developed to standardise referral of patients with diabetes to podiatry.14 Healthcare-seeking behaviours are complex and multifactorial and ethnicity and socioeconomic position can influence attendance at podiatry.26 27 Level of disease may also influence a patient's decision to attend the podiatrist and create a self-selection bias in the patients with diabetes who visit the podiatrist. Patients who received healthcare services in early stages of disease may be more likely to engage in other healthy lifestyle behaviours, for example, healthy diet, not smoking and this phenomenon of ‘healthy user bias’ has been previously documented.28 In their retrospective cohort study, Sowell et al24 reported 20 LEAs in the intervention group and 130 in the control group (noting that the population at risk in this study is patients with diabetes and/or gangrene and/or PVD). This study described the majority of included participants with the outcome of LEA. However, their analysis did not adjust for important potential confounders which limit the conclusions that can be drawn from this study.

The issues of bias and confounding are minimised by the gold standard technique of randomisation in RCTs. However, there is a lack of RCTs in this area. The two available RCTs have a lack of power as few participants had the outcome of LEA. The most likely cause of the low numbers of outcomes in the included studies is length of follow-up. LEA takes years to develop, especially from the time-point when a patient is classified as low risk. In the first included RCT, Plank et al23 described two LEAs in the intervention group and one in the control group. In the second RCT, Ronnemaa et al22 noted no LEA after 1 year of follow-up and one LEA in the intervention group after 7 years of follow-up.16 Neither RCT was designed to assess LEA as a primary outcome and thus, had insufficient power to detect a significant difference for the outcome of LEA.

Conclusions and implications

Two Cochrane reviews have looked at the outcome of LEA in patients with diabetes.16 17 These reviews concluded that there is insufficient evidence that brief educational interventions or complex interventions reduce the risk of LEA. This systematic review concludes that there is insufficient evidence that contact with a podiatrist reduces the risk of LEA in patients with diabetes. Thus, this review cannot make any recommendations about practice. To detect the true effect, adequately powered RCTs and longer follow-up studies are needed to examine the effect of contact with a podiatrist on LEA in patients with diabetes. Perhaps, podiatry programmes could be rolled out in a manner designed to answer the question of effect on outcomes such as LEA. Such studies could also assess the impact of the timing and intensity of the podiatry intervention on outcomes. Perhaps studies focusing on high-risk participants are too close in timing to the LEA event and studies of lower-risk participants would be better to detect an effect in LEA prevention.

International standards recommend a multidisciplinary team should manage the footcare of a patient with diabetes.14 Many studies have looked at the effects of a multidisciplinary team of which podiatry serves as a member of the team and found positive effects on various outcomes.29–36 This may be a more realistic reflection of how patients with diabetes are managed; looking at one service in isolation could be flawed as services are seldom delivered in isolation. According to the SIGN guidelines a multidisciplinary foot team should include a podiatrist, diabetes physician, orthotist, diabetes nurse specialist, vascular surgeon, orthopaedic surgeon and radiologist.14 A systematic review of the literature looking at the effectiveness of multidisciplinary teams which include contact with a podiatrist would be useful.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the authors who responded to our queries and Professor John Browne, UCC for advice on methodology.

Footnotes

Contributors: CMB conceived and designed the study, extracted the data and wrote the paper. IJP revised the paper. CPB approved the final version to be published. PMK designed the study, extracted the data and wrote the paper. CMB will act as guarantor for the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project is partially funded by the HRB (Health Research Board), Ireland—Grant Reference Number: HPF/2009/79 and partially funded by the ICGP (Irish College of General Practitioners) Research and Education Foundation.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lam DW, LeRoith D. The worldwide diabetes epidemic. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obesity 2012;19:93–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moxey P, Gogalniceanu P, Hinchliffe R, et al. Lower extremity amputations—a review of global variability in incidence. Diabetic Med 2011;28:1144–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner R, Holman R, Stratton I, et al. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ 1998;317:703–13 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998;352:837–53 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulton AJ. Lowering the risk of neuropathy, foot ulcers and amputations. Diabet Med 1998;15(Suppl 4):S57–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apelqvist J, Larsson J. What is the most effective way to reduce incidence of amputation in the diabetic foot? Diabetes/Metab Res Rev 2000;16:S75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA 2005;293:217–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IDF. Position Statement—the Diabetic Foot. Secondary Position Statement—the Diabetic Foot. http://www.idf.org/position-statement-diabetic-foot (accessed 24 Mar 2013).

- 9.Adler A, Erqou S, Lima TAS, et al. Association between glycated haemoglobin and the risk of lower extremity amputation in patients with diabetes mellitus—review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2010;53:840–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adler AI, Boyko EJ, Ahroni JH, et al. Lower-extremity amputation in diabetes. The independent effects of peripheral vascular disease, sensory neuropathy, and foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pecoraro R, Reiber G, Burgess E. Pathways to diabetic limb amputation. Basis for prevention. Diabetes Care 1990;13:513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agardh E, Allebeck P, Hallqvist J, et al. Type 2 diabetes incidence and socio-economic position: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:804–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boulton AJM, Armstrong DG, Albert SF, et al. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1679–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SIGN. Management of diabetes. A national clinical guideline March 2010. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign116.pdf (accessed 24 Mar 2013).

- 15.NHS. Careers in Detail. Secondary Careers in Detail. http://www.nhscareers.nhs.uk/details/Default.aspx?Id=280 (accessed 24 Mar 2013).

- 16.Dorresteijn JA, Kriegsman DM, Valk GD. Complex interventions for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD007610 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007610.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Dorresteijn JA, Kriegsman DM, Assendelft WJ, et al. Patient education for preventing diabetic foot ulceration. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD001488 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001488.pub4). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 1998;52:377–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavery LA, Hunt NA, LaFontaine J, et al. Diabetic foot prevention. Diabetes Care 2010;33:1460–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronnemaa T, Hamalainen H, Toikka T, et al. Evaluation of the impact of podiatrist care in the primary prevention of foot problems in diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 1997;20:1833–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plank J, Haas W, Rakovac I, et al. Evaluation of the impact of chiropodist care in the secondary prevention of foot ulcerations in diabetic subjects. Diabetes Care 2003;26:1691–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sowell RD, Mangel WB, Kilczewski CJ, et al. Effect of podiatric medical care on rates of lower-extremity amputation in a medicare population. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1999; 89:312–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pereira TV, Patsopoulos NA, Salanti G, et al. Critical interpretation of Cochran's Q test depends on power and prior assumptions about heterogeneity. Res Synth Methods 2010;1:149–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fylkesnes K. Determinants of health care utilization—visits and referrals. Scand J Public Health 1993;21:40–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adamson J, Ben-Shlomo Y, Chaturvedi N, et al. Ethnicity, socio-economic position and gender—do they affect reported health—care seeking behaviour? Soc Sci Med 2003;57:895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson LA, Jackson ML, Nelson JC, et al. Evidence of bias in estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness in seniors. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:337–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leese GP, Schofield CJ. Amputations in diabetes: a changing scene. Prac Diabetes Int 2008;25:297–9 [Google Scholar]

- 30.El Sakka K, Fassiadis N, Gambhir RP, et al. An integrated care pathway to save the critically ischaemic diabetic foot. Int J Clin Pract 2006;60:667–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dargis V, Pantelejeva O, Jonushaite A, et al. Benefits of a multidisciplinary approach in the management of recurrent diabetic foot ulceration in Lithuania: a prospective study. Diabetes Care 1999;22:1428–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Gils CC, Wheeler LA, Mellstrom M, et al. Amputation prevention by vascular surgery and podiatry collaboration in high-risk diabetic and nondiabetic patients. The Operation Desert Foot experience. Diabetes Care 1999;22:678–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meltzer DD, Pels S, Payne WG, et al. Decreasing amputation rates in patients with diabetes mellitus. An outcome study. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2002;92:425–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson J, Apelqvist J, Agardh CD, et al. Decreasing incidence of major amputation in diabetic patients: a consequence of a multidisciplinary foot care team approach? Diabet Med 1995;12:770–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frykberg RG. Team approach toward lower extremity amputation prevention in diabetes. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1997; 87:305–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patout CA, Birke JA, Horswell R, et al. Effectiveness of a comprehensive diabetes lower-extremity amputation prevention program in a predominantly low-income African-American population. Diabetes Care 2000;23:1339–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lipscombe J, Jassal SV, Bailey S, et al. Chiropody may prevent amputations in diabetic patients on peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 2003;23:255–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sloan FA, Feinglos MN, Grossman DS. Receipt of care and reduction of lower extremity amputations in a nationally representative sample of U.S. elderly. Health Serv Res 2010;45:1740–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.