Abstract

Chronic infections strain the regenerative capacity of antiviral T lymphocyte populations, leading to failure in long-term immunity. The cellular and molecular events controlling this regenerative capacity, however, are unknown. We found that two distinct states of virus-specific CD8+ T cells exist in chronically infected mice and humans. Differential expression of the T-box transcription factors T-bet and Eomesodermin (Eomes) facilitated the cooperative maintenance of the pool of antiviral CD8+ T cells during chronic viral infection. T-bethi cells displayed low intrinsic turnover but proliferated in response to persisting antigen, giving rise to Eomeshi terminal progeny. Genetic elimination of either subset resulted in failure to control chronic infection, which suggests that an imbalance in differentiation and renewal could underlie the collapse of immunity in humans with chronic infections.

Lifelong immunity to acutely resolved infections requires maintenance of memory lymphocytes that, upon reinfection, regenerate a large cohort of short-lived, terminal progeny while concurrently replenishing the long-lived memory pool. During low-level latent/reactivating infections, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), this periodic replenishment of short-lived and long-lived populations is balanced to achieve lifelong immunity. Chronic viral infections with prolonged and elevated antigen load, however, may strain the renewal capacity of long-lived lymphocytes by persistent elicitation of short-lived cells. For example, increased CD8+ T cell turnover is observed during HIV infection (1–3). This stems from an elevated production of short-lived cells and a concurrent reduction in the long-lived pool (4) and is thought to underlie the eventual collapse of adaptive immunity during HIV infection. It is unclear, however, which molecular pathways govern the renewal and differentiation of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during chronic infections, or whether these antiviral responses are sustained by a progenitor-progeny relationship.

Two T-box transcription factors, T-bet and Eomesodermin (Eomes), regulate both functional and dysfunctional CD8+ T cell responses (5–10). During chronic viral infections, T-bet is reduced in virus-specific CD8+ T cells, and this reduction correlates with T cell dysfunction (9–11). In contrast, microarray analysis of CD8+ T cells suggested that Eomes mRNA is elevated during chronic infection (12). Using acute or chronic infection with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), we found that Eomes expression was up-regulated in exhausted CD8+ T cells during chronic infection (Fig. 1, A to C, and fig. S1A).

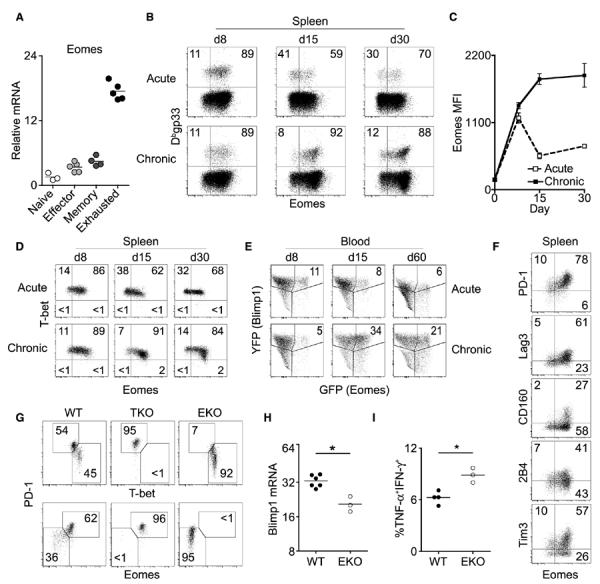

Fig. 1.

Eomes expression is up-regulated during chronic viral infection and supports enhanced CD8+ T cell exhaustion. (A) Sorted naïve or Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells from effector [acute; Armstrong day 8 (d8)], memory (acute; Armstrong d30), or exhausted (chronic; clone 13, d30) time points were analyzed for Eomes mRNA expression by real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction. (B) Flow cytometric analysis of Eomes protein expression in Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells at indicated numbers of days post-infection (p.i.) (C) Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of Eomes expression from cells in (B). Graph displays means ± SEM. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of T-bet versus Eomes expression in Dbgp33-specifc CD8+ T cells at indicated days p.i. Gates are based on T-bet–negative and Eomes-negative cells. (E) Longitudinal frequency of GFP+YFP+ Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells in Blimp1-YFP/Eomesgfp/+ dual reporter mice as analyzed by flow cytometry (GFP and YFP, green and yellow fluorescent protein, respectively). (F) Flow cytometric analysis of inhibitory receptor versus Eomes expression in Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells at d30 p.i. (G) Flow cytometric analysis of T-bet, Eomes, and PD-1 expression of Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells from wild-type (WT), T-bet KO (TKO), and Eomes cKO (EKO) mice at d22 p.i. (H) Blimp1 relative mRNA in Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells from WT and EKO mice at d15 p.i. (*P < 0.05; Mann-Whitney). (I) IFN-γ and TNF-α expression in CD8+ T cells from indicated mice after peptide pool stimulation as in fig. S1 (**P < 0.01; unpaired t test). In (B) to (G), numbers denote frequency of gated population; in (F) to (I), cells are from clone 13 infection. All data are representative of two to five independent experiments with at least three mice per experimental group.

In contrast to acute infection, T-bet and Eomes were reciprocally expressed in exhausted CD8+ T cells by day 15 to day 30 of chronic infection (Fig. 1D). In addition, Eomes-expressing CD8+ T cells had higher expression of Blimp-1 and several inhibitory receptors (Fig. 1, E and F, and fig. S1B), consistent with more severe exhaustion (13–17). Furthermore, Eomeshi virus-specific CD8+ Tcells had less co-production of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) (16, 18) (fig. S1C). However, high expression of Eomes or the inhibitory receptor PD-1 correlated with increased granzyme B and cytotoxicity, despite lower degranulation (fig. S1, D to H). Thus, Eomes expression in virus-specific CD8+ T cells during chronic infection was associated with markers of severe exhaustion and reduced co-production of antiviral cytokines, despite better cytotoxicity than T-bethi cells.

Although wild-type CD8+ T cells had bimodal expression of T-bet and Eomes, genetic deletion of T-bet resulted in increased Eomes and PD-1 expression (Fig. 1G) (9). In contrast, Eomes-deficient CD8+ T cells had reduced PD-1 and Blimp-1, as well as increased T-bet and cytokine co-production (Fig. 1, G to I, and fig. S2). Thus, T-bet and Eomes support separate subpopulations of virus-specific CD8+ T cells during chronic infection.

To determine the relative contribution of these T-bethi and Eomeshi CD8+ T cell subsets to the magnitude of the response during chronic infection, we quantified these populations in multiple anatomical locations. Overall, the Eomeshi population outnumbered the T-bethi population by a factor of ~20 (fig. S3A), and these subsets had distinct tissue distribution (fig. S3, B and C). As observed in intact mice, sorted and adoptively transferred PD-1int (T-bethi) cells preferentially accumulated in the spleen, whereas PD-1hi (Eomeshi) cells distributed systemically (fig. S3, D and E). These data indicate a large numerical accumulation of Eomeshi exhausted CD8+ Tcells throughout the body and suggest potential distinct contributions of Eomeshi and T-bethi subsets to the antiviral response.

Previous studies suggest that proliferating and nonproliferating subpopulations of exhausted CD8+ Tcells exist during chronic infections (4, 19), but the regulation of this process is poorly understood. We hypothesized that T-bethi and Eomeshi CD8+ T cells might have different in vivo proliferative dynamics. Whereas T-bethi CD8+ Tcells had low expression of the cell cycle–regulated protein Ki67 and low incorporation of 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU), Eomeshi CD8+ T cells expressed Ki67 and had high BrdU incorporation in multiple tissues (Fig. 2A and fig. S4, A to C). Using carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (fig. S4D), we observed robust proliferation in CD8+ T cells that were Eomeshi at the time of analysis, whereas less CFSE dilution was observed for the T-bethi population (Fig. 2B). The modest proliferation of T-bethi cells was unlikely to have been due to limited access to antigen, because essentially all virus-specific memory CD8+ T cells divided extensively in this setting (fig. S4, E and F) (19). In addition, T-bet and Eomes governed these distinct proliferative behaviors, because deletion of T-bet increased Ki67 expression and BrdU incorporation, whereas loss of Eomes diminished proliferation (Fig. 2C and fig. S4G). Thus, T-bet and Eomes regulate distinct CD8+ T cell pools with differential division during chronic infection.

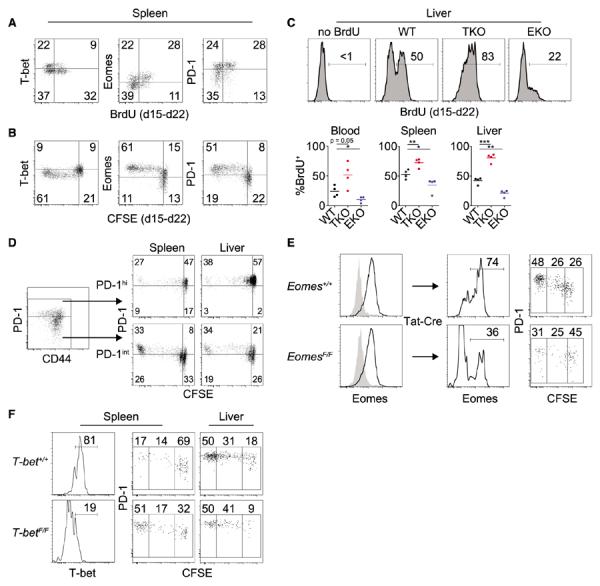

Fig. 2.

Conversion from T-bethi precursors to Eomeshi progeny is critical for the antiviral CD8+ T cell response. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of T-bet, Eomes, and PD-1 expression versus BrdU incorporation in Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells monitored from d15 to d22 p.i. Gates are placed between T-bethi and Eomeshi populations (fig. S4B). (B) Flow cytometric analysis of T-bet, Eomes, and PD-1 expression versus CFSE in Dbgp276-specific donor CD8+ T cells monitored from d15 to d22 p.i. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of BrdU incorporation in Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells from WT, TKO, and EKO mice monitored from d15 to d22. Upper panels are representative stains; lower panels are summarized data (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; unpaired t test). In (A) to (C), data are representative of two to five independent experiments with at least three mice per experimental group. Gates were set on the basis of staining controls for BrdU, CFSE, GFP, or T-bethi and Eomeshi subsets. (D) Flow cytometric analysis of PD-1 expression versus CFSE dilution of sorted PD-1int or PD-1hi Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells 7 days after transfer. (E) Eomes+/+ and EomesF/F CD8+ T cells were isolated at d15 p.i. and treated in vitro with Tat-Cre. Two weeks after transfer, Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells were assessed for Eomes and PD-1 expression and CFSE dilution by flow cytometry. (F) T-bet+/+ and T-betF/F CD8+ T cells were isolated at d15 p.i. and treated in vitro with Tat-Cre. Two weeks after transfer, Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells were assessed for T-bet and PD-1 expression and CFSE dilution by flow cytometry. Data in (D) to (F) are representative of two to four independent experiments.

To trace lineage relationships, we used PD-1 expression as a surrogate marker (fig. S1F) to separate T-bethi and Eomeshi subsets, followed by CFSE labeling to monitor proliferation and differentiation. After adoptive transfer to infection-matched mice (fig. S5A), PD-1hi (Eomeshi) CD8+ T cells divided modestly and retained high expression of PD-1 (Fig. 2D and fig. S5B). In contrast, purified PD-1int (T-bethi) CD8+ T cells demonstrated enhanced in vivo proliferation, and this extensive division was associated with conversion to PD-1hi (Fig. 2D and fig. S5B). Similar results were obtained using an Eomesgfp/+ reporter mouse (20) (fig. S5, C and D). Thus, virus-specific CD8+ Tcells converted from T-bethi to Eomeshi in a process coupled to extensive cell division. Once generated by conversion from T-bethi cells, however, the PD-1hi Eomeshi T-betlo subset had reduced capacity to undergo additional vigorous proliferation in vivo.

To test whether Eomes was essential during the T-bethi to Eomeshi transition, we treated virus-specific CD8+ T cells from chronically infected Eomes+/+ and EomesF/F mice in vitro with Tat-Cre and adoptively transferred them into infection-matched mice (fig. S5E). The temporal loss of Eomes reduced the extensively divided CD8+ T cell population (Fig. 2E), which suggests that Eomes is critical for initiating or sustaining this proliferative and conversion event. In contrast, temporal deletion of T-bet (fig. S5F) accelerated decay of the progenitor population (Fig. 2F), suggesting a critical role for T-bet in maintaining this precursor pool. Thus, temporal deletion indicates an ongoing requirement for these transcription factors in regulating the differential proliferative behavior of subsets of exhausted CD8+ T cells.

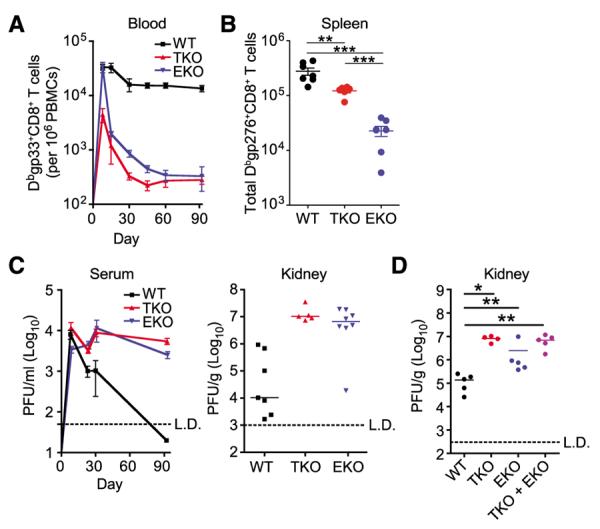

The absence of T-bet impedes the control of chronic viral infection, possibly due to a shift toward more severe exhaustion (9). In light of the reduced features of exhaustion when Eomes was deleted (Fig. 1, G to I), we tested whether eliminating Eomes would improve control of chronic viral infection. In the absence of T-bet or Eomes, however, virus-specific CD8+ T cells could neither maintain the antiviral response (Fig. 3, A and B, and figs. S6 and S7) nor limit viral replication (Fig. 3C and fig. S8). Because each subpopulation failed to independently sustain an effective response, it was possible that the T-bet–dependent and Eomes-dependent subsets might contribute distinct functions and cooperate to achieve viral control. To test this possibility, we examined mixed chimeras containing both Eomes conditional knockout (cKO) and T-bet KO bone marrow. The combination of Eomes cKO (T-bethi)–exhausted and T-bet KO (Eomeshi)–exhausted CD8+ T cells, however, did not improve viral control over either subset alone (Fig. 3D). These data suggest that the major factor sustaining virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses and containing viral replication during chronic infection is not independent functions of T-bethi and Eomeshi CD8+ T cells, but rather the lineage relationship between these subpopulations.

Fig. 3.

Deletion of T-bet or Eomes leads to impaired maintenance of the CD8+ T cell response and loss of viral control. (A) Longitudinal frequency of Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood of infected mice (PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells). (B) Total Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells in the spleens of indicated mice at d30 p.i. (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; unpaired t test). (C) Viral load in the serum longitudinally and kidney at d90 p.i. (PFU, plaque-forming units). (D) Viral load in kidneys of bone marrow chimeras transplanted with indicated bone marrow at d90 p.i. (*P < 0.05,**P<0.01;Mann-Whitney). All panels used LCMV clone 13 infection. Data are representative of two to six independent experiments with at least four mice per experimental group.

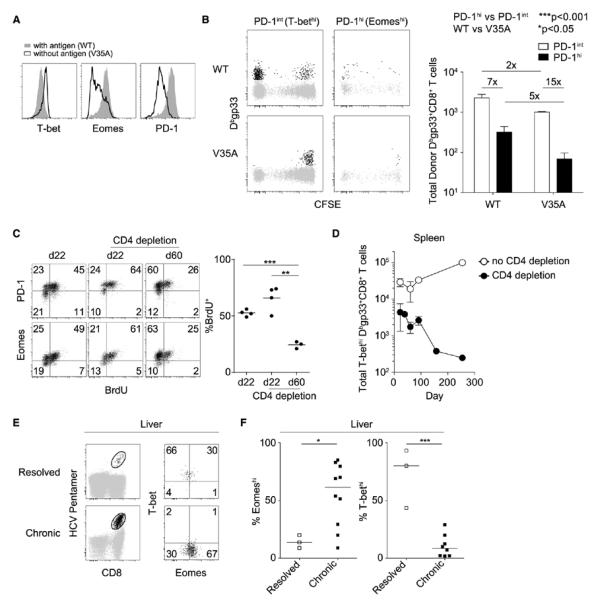

We next tested whether persisting antigen was necessary for converting T-bethi precursors into the Eomeshi progeny. Relative to cells adoptively transferred into a wild-type infection, transfer into mice chronically infected with a variant of LCMV containing a mutation in the gp33-41 epitope (V35A) (19) resulted in H-2Db–restricted gp33-specific CD8+ T cells with elevated T-bet but reduced Eomes and PD-1 expression (Fig. 4A). The preferential recovery of T-bethi cells in the absence of antigen resulted from poor persistence of preformed Eomeshi cells and reduced repopulation of Eomeshi cells from the T-bethi pool (Fig. 4B and fig. S9). In addition, Eomeshi cells retained Eomes expression and did not revert back to Eomeslo cells after the removal of antigen (fig. S9C), which suggested that conversion from T-bethi to Eomeshi during chronic infection is accompanied by terminal differentiation.

Fig. 4.

Persistent antigen may progressively deplete the T-bethi Eomeslo CD8+ T precursor pool. (A) CD8+ T cells from infected mice were isolated at d8 p.i. and transferred to mice infected with either WT or V35A clone 13. Flow cytometry plots display T-bet, Eomes, and PD-1 expression in Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells in the presence or absence of antigen. (B) Left: Flow cytometric analysis of CFSE dilution and recovery of sorted Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells 2 weeks after transfer into WT or V35A infections. Right: Mean numbers (TSEM) of Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells from three mice per experimental group (two-way analysis of variance). Numbers followed by x denote relative difference between the indicated groups. (C) Left: Flow cytometric analysis of Eomes and PD-1 expression versus BrdU incorporation in Dbgp276-specific CD8+ T cells from WT mice infected with clone 13 with or without CD4+ T cell depletion. Right: Summary data for multiple mice (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; unpaired t test). Data in (A) to (C) are representative of two or three independent experiments with at least three mice per experimental group. (D) Total T-bethi Dbgp33-specific CD8+ T cells were enumerated at the indicated time points with or without CD4+ T cell depletion. Data are aggregated across three independent experiments. (E) Flow cytometric analysis of T-bet and Eomes expression in intrahepatic HCV-specific CD8+ T cells isolated from patients with resolved or chronic infections. (F) Frequency of Eomeshi and T-bethi HCV-specific CD8+ T cells in the liver of patients with resolved or chronic infections (*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001; unpaired t test). In (E) and (F), a total of 3 and 10 samples were analyzed from resolved and chronic infections, respectively.

If persisting antigen induces T-bethi precursors to continually proliferate and give rise to Eomeshi progeny, one might predict that prolonged, uncontrolled viral replication could eventually deplete the T-bethi precursor population. This possibility was tested by transiently depleting CD4+ T cells before LCMV clone 13 infection, which led to lifelong high viral load (21). Sustained high viral loads caused an erosion of the in vivo BrdU accumulation in the Eomeshi subset and loss of T-bethi precursors over time (Fig. 4, C and D, and fig. S10), suggesting a progressive imbalance of T-bethi to Eomeshi lineage repopulation.

To examine whether years of chronic viral infection erode virus-specific CD8+ T cell renewal capacity by continuous depletion of the T-bethi precursor pool, we examined hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Although 20 to 30% of HCV infections spontaneously resolve, most untreated patients experience a high viral burden for many years (22). Patients with uncontrolled viral replication have a gradual loss of systemic CD8+ T cell responses with an associated accumulation of highly exhausted T cells in the liver (23–26), consistent with a dys-regulated balance between self-renewal and terminal differentiation. We therefore examined whether T-bethi precursors could be found in patients with resolved versus chronic HCV infection and whether Eomeshi progeny accumulated in patients with active viral replication (Fig. 4E). Although HCV-specific CD8+ T cells in the blood trended toward higher Eomes expression in chronically infected subjects, there was equivalent T-bet expression in systemic responses from resolved or chronic infection (fig. S11). In contrast, at the site of viral replication, there was substantial accrual of Eomeshi HCV-specific CD8+ T cells and a relative depletion of the T-bethi subset during chronic infection relative to resolved infection (Fig. 4, E and F). Consistent with the observations in mice, chronic HCV infection is associated with few T-bethi precursors and concurrent accumulation of Eomeshi terminal progeny.

Memory CD8+ T cells generated after acutely resolved infection or successful vaccination are quiescent, but they are capable of slow self-renewal and production of differentiated effector progeny upon reinfection (27, 28). In contrast, exhausted CD8+ T cells during chronic infections are continually activated by persisting antigen and undergo prolonged, extensive division (19, 29, 30). It has been unclear how the regenerative capacity of these cells develops and why it ultimately fails in pathological chronic infections. Collectively, our results suggest that in the face of persisting antigen, virus-specific CD8+ T cells make use of two homologous T-box transcription factors to maintain long-lasting antiviral immunity. This maintenance parallels progenitor-progeny dynamics of cells in other tissues organized according to proliferative hierarchies. Although unable to fully eradicate the virus, these two cell subsets act together to maintain a durable and partially effective CD8+ T cell response during chronic infection.

Despite functional impairment, exhausted CD8+ T cells are not inert. Rather, these cells continually constrain viral replication and/or drive viral epitope escape (31). The critical balance between progenitors and progeny in exhausted CD8+ T cells indicates a vital role for proper regulation of antiviral lymphocyte dynamics during chronic infections. In addition, the ability to define and monitor progenitors and progeny over time might provide an opportunity to pre dict the collapse of long-term control of chronic infections. Delineating the molecular coordination of this process provides a framework for prophylactic or therapeutic strategies to improve the durability and regenerative capacity of antiviral T cells during persisting infections.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Wherry, Reiner, and Artis labs for helpful comments and the UPenn Flow Cytometry Core for cell sorting. We thank E. Crosby for isolation of skin lymphocytes. Supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant r3839/1-1 (D.C.K.); NIH grants T32-AI-07324 (M.A.P.), AI0663445 (G.M.L.), AI061699 and AI076458 (S.L.R.), AI083022, AI078897, and HHSN266200500030C (E.J.W.), and AI082630 (E.J.W. and G.M.L.); and the Dana Foundation (E.J.W. and G.M.L.). E.J.W. has a patent licensing agreement on therapeutic targeting of the PD-1 pathway (U.S. patent application no. 20070122378).

Footnotes

Supplementary Materials www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/338/6111/1220/DC1

References and Notes

- 1.Sachsenberg N, et al. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:1295. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.8.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hellerstein M, et al. Nat. Med. 1999;5:83. doi: 10.1038/4772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCune JM, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;105:R1. doi: 10.1172/JCI8647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hellerstein MK, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:956. doi: 10.1172/JCI17533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Intlekofer AM, et al. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:2015. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi NS, et al. Immunity. 2007;27:281. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Intlekofer AM, et al. Science. 2008;321:408. doi: 10.1126/science.1159806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee A, et al. J. Immunol. 2010;185:4988. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kao C, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:663. doi: 10.1038/ni.2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hersperger AR, et al. Blood. 2011;117:3799. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-322727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro-Dos-Santos P, et al. Blood. 2012;119:4928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wherry EJ, et al. Immunity. 2007;27:670. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin H, et al. Immunity. 2009;31:309. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber DL, et al. Nature. 2006;439:682. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Day CL, et al. Nature. 2006;443:350. doi: 10.1038/nature05115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blackburn SD, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:29. doi: 10.1038/ni.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin HT, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:14733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009731107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blackburn SD, et al. J. Virol. 2010;84:2078. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin H, Blackburn SD, Blattman JN, Wherry EJ. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:941. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold SJ, Sugnaseelan J, Groszer M, Srinivas S, Robertson EJ. Genesis. 2009;47:775. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matloubian M, Concepcion RJ, Ahmed R. J. Virol. 1994;68:8056. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8056-8063.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Micallef JM, Kaldor JM, Dore GJ. J. Viral Hepat. 2006;13:34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lechner F, et al. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:2479. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200009)30:9<2479::AID-IMMU2479>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasprowicz V, et al. J. Virol. 2008;82:3154. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02474-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamoto N, et al. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1927. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMahan RH, et al. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:4546. doi: 10.1172/JCI43127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ciocca ML, Barnett BE, Burkhardt JK, Chang JT, Reiner SL. J. Immunol. 2012;188:4145. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wherry EJ, et al. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:225. doi: 10.1038/ni889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Casazza JP, Betts MR, Picker LJ, Koup RA. J. Virol. 2001;75:6508. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.14.6508-6516.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wherry EJ, Barber DL, Kaech SM, Blattman JN, Ahmed R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:16004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407192101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wherry EJ. Nat. Immunol. 2011;12:492. doi: 10.1038/ni.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.