Abstract

Objectives

Evidence-based services improve outcomes in schizophrenia, but most patients at mental health clinics do not receive such services. This gap in care has been perpetuated by a lack of routinely collected data on patients’ clinical status and the treatments they receive. However, routine data collection can be completed by patients themselves, especially when aided by health information technology (HIT). It is not known whether these data can be used to improve care quality.

Methods

In a controlled trial, eight medical centers of the Veterans Health Administration were assigned to implementation or usual care. 571 patients with schizophrenia were overweight and had not used evidence-based weight services. The implementation strategy included data from patient-facing kiosks, continuous data feedback, clinical champions, education, social marketing, and evidence-based quality improvement teams. Mixed methods evaluated the impact of the kiosks on utilization of and retention in weight services.

Results

Compared with usual care, implementation resulted in individuals being more likely to use weight services, getting services more than 5 weeks sooner, and using 3 times more visits. When compared to the year prior to implementation, patients at implementation sites saw a three-fold increase in treatment visits. Usual care resulted in no change.

Conclusions

Mental health clinics have been slow to adopt HIT. This study is among the first to implement and evaluate automated collection of data from patients at these clinics. Patient-facing kiosks are feasible in routine care, and provide data that can be used to substantially improve the quality of care.

Keywords: Health Information Technology, Quality Improvement, Mental Health

INTRODUCTION

Schizophrenia is a chronic serious mental illness (SMI) that occurs in about 1% of the population, and results in substantial morbidity and mortality when poorly treated.1-4 Although evidence-based practices improve outcomes and facilitate independence in schizophrenia,5 these treatments are not often used.3,6 Evidence-based family psychoeducation, for example, has a large effect size in efficacy studies, yet when made available in usual care clinics, is poorly attended.7,8 Improving the utilization of services for appropriate patients has been nearly impossible in specialty mental health because existing medical records (including electronic medical records) lack reliable, routinely collected data about patient symptoms, service needs and preferences, and utilization of evidence-based treatments9 and clinicians report being too busy to collect these data themselves.10-12 Collection of such data could allow care quality to be monitored, and improved, by identifying patients who would benefit from a specific evidence-based treatment, fostering access to and monitoring retention in that treatment.13 Other medical specialties have successfully used routinely collected patient data to improve care (e.g., Hemoglobin A1C for diabetes), yet mental health clinics have been slow to adopt methods for routine patient monitoring and have not tested whether such data can support quality improvement.14

Evidence-based quality improvement (EBQI)15-17 aims to systematically incorporate evidence and data regarding care provision and patient outcomes into quality improvement efforts, and has been utilized to improve care quality for depression.18,19 The question of how best to incorporate data—especially patient-centered data—into EBQI efforts targeting those with schizophrenia remains open, and represents an opportunity for HIT. The Institute of Medicine has strongly encouraged the use of HIT to obtain data from patients and then match their needs and preferences to evidence-based services, in order to improve the quality of care.20 Our group has amassed evidence that patients with SMI can complete self-assessments using HIT. In a series of studies, patient-facing kiosks have delivered gold-standard measures to outpatients with SMI and were found to be as accurate as clinician-delivered assessments, as well as reliable, feasible to implement in specialty mental health clinics, and preferred by this population.21,22 From our review, though, HIT systems such as patient-facing kiosks have not been used as part of a quality improvement effort in specialty mental health until the current study.

The use of evidence-based weight management services is garnering considerable attention in specialty mental health since up to 75% of individuals with schizophrenia are overweight or obese due to a combination of illness-related factors and use of 2nd generation antipsychotic medications.23,24 People with schizophrenia lose 25 or more years of life expectancy, predominantly due to cardiovascular disease.25-27 This loss of life expectancy is attributable to obesity, and related diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which are 1.5-4 times more common than in the general population.28,29 There are effective weight interventions tailored for this population,30-32 but these programs are typically implemented in settings where high enrollment and retention rates are ensured (e.g., inpatient wards, day hospitals). In outpatient settings, enrollment and retention rates are consistently low, leading to an impact less than that observed in efficacy studies, and thereby leaving room for quality improvement.33

In this article, we report on “Enhancing QUality of Care In Psychosis” (EQUIP) which utilized a Hybrid Type 2 effectiveness-implementation study design. This design balances attention to the effectiveness of the clinical intervention and the implementation strategy that supports the intervention.34,35 EQUIP evaluated effectiveness and implementation of evidence-based care for schizophrenia at specialty mental health clinics in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). The clinical interventions of interest were Supported Employment and psychosocial interventions for weight management; this paper focuses on the latter. The implementation strategy included health information technology (HIT) in the form of routine data collection from patient-facing kiosks; continuous feedback of those data to patients, clinicians and managers; clinical champions; patient and clinician education; social marketing; and evidence-based quality improvement teams. Mixed methods were used to evaluate implementation and effectiveness, relative to usual care. We hypothesized that overweight individuals with schizophrenia at implementation sites would have timelier and greater utilization of weight services compared to similar individuals in usual care.

METHODS

Design

Veterans’ health care in the U.S. is separated geographically into 21 regions known as Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs). This clinic-level controlled trial was conducted in 4 of these VISNs. Leadership in each VISN nominated pairs of specialty mental health clinics. Pairs were matched on academic affiliation (known to affect organizational engagement in quality improvement),36,37 and number of patients with schizophrenia. Within each VISN pair, based on the preferences of VISN leadership, one clinic was assigned to implementation and the other to control (usual care), for a total of 4 implementation and 4 control clinics.

The effectiveness evaluation began in January 2008 when patients began enrollment and completed a baseline survey. Patient enrollment lasted an average of 13 months. Final patient interviews began in May 2009. In addition to this assessment, every third patient at implementation sites participated in a short semi-structured interview at post-implementation about the acceptability of the patient-facing kiosks. Utilization of weight management services by each patient was extracted from the electronic medical record for the year prior to baseline and the year of the study.

Participants

Patients were eligible to participate if they: 1) were at least 18 years old, 2) had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and 3) had at least two mental health clinic visits during a 6-month eligibility period. From the overall population of eligible patients, a random sample was identified at each site. Probability of inclusion was based on the overall eligible population, desired sample size, and expected non-participation. Eligible veterans were approached in person at clinic visits: 1964 patients were eligible, and 801 of these were contacted and consented to be enrolled (41%). 637 (80%) had a body mass index (BMI) of 25 or greater. Of those 637, 23 were excluded because they were at an implementation site but never used the patient-facing kiosks, and an additional 43 were excluded because they had a weight management visit in the month prior to enrollment, indicating that their utilization of weight services could not be attributed to implementation. Thus a total of 571 individuals (281 implementation, 290 control) were included in the analyses. Of 281 patients at implementation sites, 83 patients completed the brief post-implementation interview (average of 20 subjects at each site).

Clinicians were eligible to participate if they treated eligible patients. Mental health administrators of the enrolled clinics were also eligible. All clinicians and administrators agreed to participate. Written informed consent was obtained from patients, clinicians, and administrators. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of all applicable sites.

Implementation

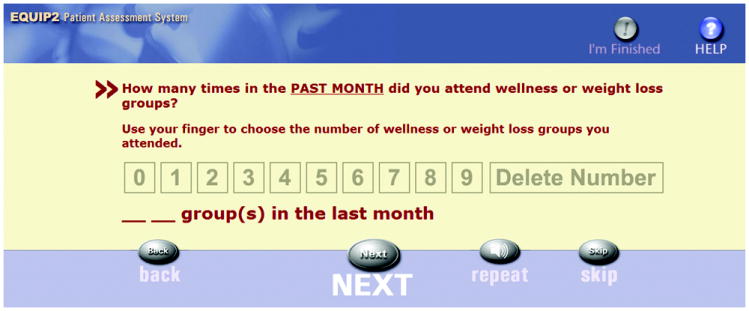

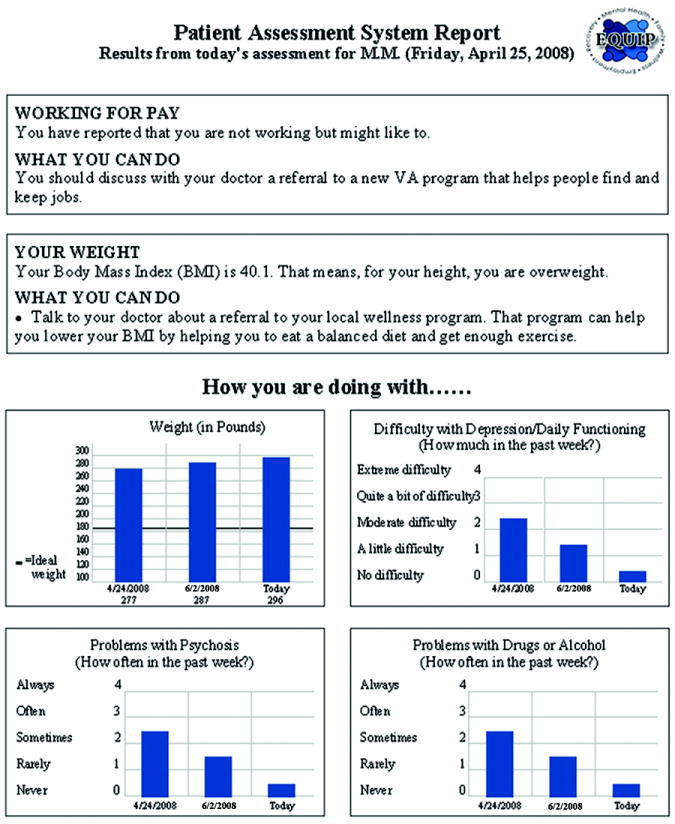

Patient-facing kiosks, called the Patient Assessment System (PAS), were placed in the waiting room of each implementation clinic and used for patient self-reporting of clinical status. Kiosks included audio and visual presentation of questions, were designed for people with cognitive deficits or limited literacy, and included a touchscreen monitor, computer, headphones, and a color printer.21 A scale was located next to each kiosk. At every clinic visit, before seeing the clinician, patients responded to questions including their current weight, whether they had received a referral to a weight service, and how many weight management visits they had in the past month. Questions were presented visually and orally (see Figure 1). Following the last question, the kiosk immediately printed a Summary Report (see Figure 2), which patients were instructed to take to their clinician that day and use to track their status. The Summary Report included a bar graph showing the patient’s current, previous, and ideal weight (corresponding to a BMI of 25). If the individual was overweight, the Summary Report included a page of educational information about weight loss, and “talking points,” so that the individual could advocate for a referral to a weight management program. Kiosk data were continuously reported to clinicians, including a nurse care manager at each site, to identify appropriate referrals (anyone with BMI ≥ 25), encourage service attendance, and monitor quality improvement.

Figure 1.

Example question from the patient-facing kiosk

Figure 2.

Example of patient-facing kiosk Summary Report

The Veterans Health Administration offers weight counseling services through primary care. In addition to these, the EQUIP team developed an implementation toolkit for a weight program to be led by a mental health clinician and delivered in the specialty mental health clinics at each implementation site. The EQUIP Wellness Program was based on “Solutions for Wellness,”38 an evidence-based psychosocial program of weight management topics designed specifically for individuals with cognitive disabilities.

In summary, an EBQI framework that integrated HIT as part of the intervention was utilized at the implementation sites to support the utilization of weight management services. Specifically the strategy included routine collection of data from patient-facing kiosks, data continuously provided to clinicians and administrators, utilization of clinical champions to discuss these data and their relationship to benchmarks, clinician education, automated patient education, social marketing of the EQUIP Wellness Program, and evidence-based quality improvement multidisciplinary teams at each implementation site, some of which worked on barriers to utilization of weight management services.35

Measures

Data from the patient baseline interview were analyzed. Diagnosis was confirmed using an abbreviated version of the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV.39,40 Current symptoms were rated using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS).41 Demographics, including age, gender, race, marital status, presence of children, and education were collected. Research assistants administered the baseline interview and collected each patient’s height and weight. Interviewers were trained to a high level of reliability, and quality assurance checks were completed during the study.41 It was not possible to blind interviewers to clinic assignment. To reduce bias, interviewers had minimal or no contact with staff involved with study implementation.

Structured chart reviews were completed for each patient using the electronic medical record. Visits that included psychosocial or psychoeducational weight management interventions were counted. The total number of visits for the year pre-baseline and the year post-baseline was computed for each patient.

The semi-structured patient interview guide included questions specific to the patient-facing kiosks, e.g., “Did you enjoy sitting at the computer and answering questions?”; “Did you like having a print-out of what you said? Why?”; “In the future, would you be willing to use a kiosk or computer in the community to provide a report of your symptoms to your doctor? Why would this be a good or bad idea?” The implementation evaluation lead (AH), who is an expert in qualitative data collection and analysis, supervised the research assistants who conducted these interviews.

Data Analysis

All quantitative analyses were conducted using Statistical Software Package SAS Version 9.1.3. Analyses included only those who met the criteria for referral to weight services (BMI≥25), did not have an appointment in the month prior to baseline, and had used the patient-facing kiosks at least once (at implementation sites). Baseline characteristics between implementation and control groups were compared using t-tests for continuous and χ2 analysis for categorical variables.

Three outcomes were analyzed: 1) presence of a visit for weight management, 2) number of days from baseline to first visit for weight management, and 3) number of visits for weight management within the study year. A logistic regression model was conducted to predict presence of a visit for weight management (yes=1, no=0). Predictor variables were entered by block in the following order: intercept, demographics (age, white race, male gender, years of education), weight category (obese, overweight), and intervention status (control, implementation). A likelihood ratio test was used to test if adding intervention status to the model added significant predictive information, over demographics and weight category.42 An odds ratio for intervention status was computed. General linear models (GLM) were conducted to predict the number of days from the baseline to the first visit for weight management and the number of visits for weight management within the study year. Each GLM used the same predictor variables in the same block order as the logistic regression model. The extra sums of squares test was used to determine if each additional block added significant predictive information to the model.42 A sensitivity analysis examined the impact of controlling for weight management service use in the year before baseline on all three outcomes. In these additional analyses, the additional covariate was not significant nor did it improve the explanatory power of the model.

Qualitative data (i.e., short answers) from patients were placed in a domain x respondent matrix by the implementation evaluation lead (AH) and the study co-Principal Investigator (AC), who examined the frequency of positive, negative, and neutral responses and extracted quotes relevant to acceptability of the HIT.

RESULTS

Sample

Characteristics of the 571 participants are shown in Table 1. The average participant was 54 years old, male, either White or African-American, not currently married, and had completed high school or some college. All were diagnosed with schizophrenia. At the baseline interview, the average participant reported having mild psychotic symptoms in the previous week. The majority of the sample had a BMI in the obese range. The only significant differences between implementation and control were in presence of children and level of education. Level of education was controlled for in all the models.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients

| Sample (n=571) | Implementation (n=281) | Control (n=290) | Test Statistic t score or χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age | 54 (SD=9.1) | 54 (SD=9.2) | 54 (SD=9.0) | 0.96 |

| Male | 518 (90.7%) | 260 (92.5%) | 258 (89.0%) | 2.15 |

| Race | 5.02 | |||

| Caucasian | 255 (44.6%) | 133 (47.3%) | 122 (42.1%) | |

| African American | 261 (45.7%) | 116 (41.3%) | 145 (50.0%) | |

| Other | 55 (9.6%) | 32 (11.4%) | 23 (7.9%) | |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Presently Married | 133 (23.3%) | 61 (21.7%) | 72 (25.0%) | 0.77 |

| Has Children | 295 (51.7%) | 133 (47.3%) | 162 (55.9%) | 4.16* |

| Education | 8.77* | |||

| Less than high school | 52 (9.1%) | 35 (12.6%) | 17 (5.9%) | |

| High school graduate or some college | 388 (68.1%) | 190 (67.6%) | 198 (68.5%) | |

| College graduate or higher degree | 130 (22.8%) | 56 (19.9%) | 74 (25.6%) | |

| Clinical Characteristics | ||||

| Psychosis symptom severity (BPRS) | 2.7 (SD=1.8) | 2.7 (SD=1.8) | 2.7 (SD=1.8) | 1.00 |

| BMI category | 0.71 | |||

| Overweight (BMI 25.0 - 29.9) | 254 (44.5%) | 120 (42.7%) | 134 (46.2%) | |

| Obese (BMI ≥ 30.0) | 317 (55.5%) | 161 (57.3%) | 156 (53.8%) | |

| Service Utilization | ||||

| Number of subjects who had at least one weight management visit in year prior to baseline | 88 (15.7%) | 36 (13.0%) | 52 (18.3%) | 2.93 |

| Mean weight service appointments in the year prior to baseline (of those who had at least 1) | 2.9 (SD=4.5) | 3.5 (SD=6.6) | 2.5 (SD=2.1) | -0.83 |

p<0.05; BMI=Body Mass Index; BPRS=Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

Visit for weight management

In the year prior to baseline, rates of having at least one weight service appointment were comparable at implementation (13%) and control sites (18%) (p>.05) (Table 1). When predicting a weight management visit during the study year, intervention status (control versus implementation) was a significant predictor (χ2 = 10.5, p<.01) after controlling for demographic variables and weight category (Table 2). The likelihood ratio test indicated that this model had significantly more predictive value over a model which only included demographics and weight category (χ2 = 11.1, p<.01). The odds of having a weight service appointment during the study year was 1.9 times more likely if the individual was at an implementation site versus a control site.

Table 2.

Variables affecting receipt of a weight management visit during implementation

| Presence of a visit for weight management | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B(SE) | χ2 | p |

| Intercept | 0.34(0.73) | 0.22 | 0.65 |

| Demographics | |||

| Age | -0.01(0.01) | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| White race | -0.04(0.20) | 0.03 | 0.86 |

| Male gender | -0.56(0.32) | 3.02 | 0.08 |

| Years of education | 0.09(0.08) | 1.33 | 0.25 |

| Weight category (obese versus overweight) | 0.09(0.20) | 0.21 | 0.65 |

| Intervention status (control versus implementation) | -0.65(0.20) | 10.53 | <0.01 |

Number of days from baseline to first visit for weight management

When predicting the number of days to the first visit for weight management during the study year, intervention status (control versus implementation) was a significant predictor (t=2.0, p=.05) after controlling for demographic variables and weight category (Table 3). Specifically, individuals at control sites took, on average, 136 days (SE=17) to attend their first weight management session, compared to 98 days (SE=15) at implementation sites. The model explained 6% of the variance in the number of days to first visit for weight management, which was significantly more explained variance than the model without intervention status (F(1,143)=4.1, p<.01). Demographic variables and weight category were not significant predictors on their own.

Table 3.

Variables affecting receipt of weight management services during implementation

| Number of days from baseline to first visit for weight management | Number of visits for weight management within the study year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | B(SE) | t | p | R2 | B(SE) | t | p | R2 |

| Overall Model | F(6, 143) | 1.4 | 0.22 | 0.06 | F(6, 146) | 4.0 | 0.00 | 0.14 |

| Intercept | 121.8 (65.9) | 1.9 | 0.07 | 14.8 (5.6) | 2.7 | 0.01 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 | 0.69 | -0.1 (0.1) | -0.7 | 0.50 | ||

| White race | -10.8 (17.5) | -0.6 | 0.54 | 0.2 (1.4) | 0.1 | 0.90 | ||

| Male gender | 0.9 (26.6) | 0.03 | 0.97 | -2.9 (2.1) | -1.4 | 0.18 | ||

| Years of education | -8.0 (7.0) | -1.1 | 0.26 | 0.6 (0.6) | 1.0 | 0.33 | ||

| Weight category (obese versus overweight) | -30.0 (17.3) | -1.7 | 0.09 | -1.6 (1.5) | -1.1 | 0.28 | ||

| Intervention status (control versus implementation) | 36.0 (17.6) | 2.0 | 0.05 | -6.8 (1.5) | -4.6 | <.01 | ||

Number of visits for weight management within the study year

Patients who had a weight management visit in the year prior to baseline attended, on average, 3 weight visits at the control sites and 4 weight visits at the implementation sites in that pre-baseline year (p>.05) (Table 1). When predicting the number of visits for weight management during the study year, intervention status (control versus implementation) was a significant predictor (t=-4.6, p<.01) after controlling for demographic variables and weight category (Table 3). Specifically, individuals at control sites attended, on average, 4 (SE=1) appointments compared to 12 (SE=1) appointments at implementation sites during the study year. The model explained 14% of the variance in the number of weight management visits, which was significantly more explained variance than the model without intervention status (F(1,146)=21.4, p<.01). Demographic variables and weight category were not significant predictors on their own.

Acceptability of the Patient-facing Kiosks

In terms of acceptability, the majority of patients responded affirmatively that they enjoyed using the patient-facing kiosks (n=60; 76%) and liked getting a Summary Report (n=55; 71%). Those who found the Summary Report helpful noted that that it helped them visit with their psychiatrist and see their progress “in black and white,” as one patient said. Most (n=65; 82%) responded affirmatively that it would be good to use these kiosks in future projects; “sitting at the computer” was noted as one of the highlights of participation in the overall project. Patients noted that kiosk questions promoted self-reflection: “It asked questions that made you think about changing things about yourself;” “It kept me in check with myself;” “I like talking and being heard; I got a lot out of my system;” “The fact that I felt in touch with where I’m at; it helped me connect some dots.”

CONCLUSIONS

The implementation strategy utilized in this study, which included integration of routine data from patient-facing kiosks, resulted in patients being more likely to use weight services, getting to those services more than 5 weeks faster, and staying in services for 3 times as many visits when compared to usual care. Compared to the year prior to implementation, individuals at implementation sites saw a threefold increase in visits, while usual care essentially experienced no change. Sensitivity analyses showed that intervention status (control versus implementation) remained a significant predictor in each model after controlling for weight management service use in the pre-baseline year. It was hypothesized that overweight individuals with schizophrenia at implementation sites would have timelier and greater utilization of weight services compared to similar patients in usual care; this hypothesis was supported.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that increased utilization of weight management services for individuals with schizophrenia in typical specialty mental health clinics. This result is a critical improvement in care for individuals with schizophrenia suffering from obesity and obesity-related illnesses. The EQUIP study was successful in using an implementation strategy, including health information technology that automated routine data collection. The patient-facing kiosks provided the data needed for routine measurement of care quality and identification of patients’ service needs, allowing clinics to narrow the gap in receipt of weight management services by overweight patients. These data were used by patients to monitor their own progress and to communicate their preferences and concerns to their clinician; by clinicians to identify, refer, and encourage patients to use services; by administrators to identify service needs and engage in quality improvement; by clinical champions to discuss improvements in relation to benchmarks; and by local evidence-based quality improvement teams to measure progress towards improved care quality goals. The patient-facing kiosks also provided a means by which care became more patient-centered through printed patient reports, which informed the clinical encounter, allowed monitoring of progress toward measurable goals, and fostered patient education and activation. It is also likely that other aspects of the implementation strategy contributed to this significant improvement in weight service utilization including clinician education and social marketing of the weight groups. Consistent with previous findings in a smaller scale study,22 the patient-facing kiosks in this study were found to be acceptable to patients in this large sample.

The strength of this study is the positive impact of health information technology on the quality of care, specifically in the high priority area of overweight and obesity in individuals on antipsychotics, at typical VHA outpatient specialty mental health clinics. This study demonstrates that implementation that includes routine, electronic collection of patient data can be used to support evidence-based quality improvement. Patient-facing kiosks were easily worked into routine care flow at mental health clinics. Patients liked using them and saw their value. These same methods could likely improve care in other settings, whether in the VHA or the community. Future implementation research should examine the use of kiosks with other disorders, including bipolar disorder, depression, and anxiety disorders. Based on feedback from study patients, it could be desirable to also provide education using the kiosks, in addition to assessments. This approach could increase the effectiveness of the kiosks, and perhaps strengthen treatment engagement by patients. While it is possible to use free-standing kiosks, as we did in this study, implementation would be strengthened by integration with electronic medical record systems, where they exist. Subsequent to this study, we worked with VHA to integrate this kiosk data with the existing electronic medical record, producing note templates with data for clinicians, and data tables for quality improvement and performance measurement. It is clear that individuals with serious mental illness are able to routinely provide information using HIT in the form of kiosks used to improve their treatment and outcomes as a critical component of a quality improvement program aimed at weight management.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The research was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI; MNT 03-213), and VA Desert Pacific Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC); and by the UCLA-RAND NIMH Partnered Research Center for Quality Care (P30 MH082760). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the affiliated institutions.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None for any author.

References

- 1.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, et al. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 Sep;58(9):861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perala J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Jan;64(1):19–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehman AF. Quality of care in mental health: the case of schizophrenia. Health Affairs. 1999;18(5):52–65. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West JC, Wilk JE, Olfson M, et al. Psychiatric services. 3. Vol. 56. Washington, D.C.: 2005. Patterns and quality of treatment for patients with schizophrenia in routine psychiatric practice; pp. 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, et al. The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010 Jan;36(1):48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young AS, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB, et al. Quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in communities across the United States. Abstract Book / Association for Health Services Research. 1999;16(3):443–444. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen AN, Glynn SM, Murray-Swank AB, et al. Psychiatric services. 1. Vol. 59. Washington, D.C.: Jan, 2008. The family forum: directions for the implementation of family psychoeducation for severe mental illness; pp. 40–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen AN, Glynn SM, Hamilton AB, et al. Implementation of a family intervention for individuals with schizophrenia. J Gen Intern Med. 2010 Jan;25(Suppl 1):32–37. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cradock J, Young AS, Sullivan G. The accuracy of medical record documentation in schizophrenia. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2001 Nov;28(4):456–465. doi: 10.1007/BF02287775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Young AS. The client, the clinician, and the computer. Psychiatr Serv. 2010 Jul;61(7):643. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young AS, Niv N, Chinman M, et al. Routine Outcomes Monitoring to Support Improving Care for Schizophrenia: Report from the VA Mental Health QUERI. Community Ment Health J. 2010 Jul 25; doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbody SM, House AO, Sheldon TA. Psychiatrists in the UK do not use outcomes measures. National survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2002 Feb;180:101–103. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.2.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Young AS, Niv N, Chinman M, et al. Routine outcomes monitoring to support improving care for schizophrenia: report from the VA Mental Health QUERI. Community Ment Health J. 2011 Apr;47(2):123–135. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al. Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998 Jul;55(7):611–617. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubenstein LV, McCoy JM, Cope DW, et al. Improving patient quality of life with feedback to physicians about functional status. J Gen Intern Med. 1995 Nov;10(11):607–614. doi: 10.1007/BF02602744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rubenstein LV, Parker LE, Meredith LS, et al. Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2002 Aug;37(4):1009–1029. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.63.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shojania KG, Grimshaw JM. Still no magic bullets: pursuing more rigorous research in quality improvement. Am J Med. 2004 Jun 1;116(11):778–780. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortney J, Enderle M, McDougall S, et al. Implementation outcomes of evidence-based quality improvement for depression in VA community based outpatient clinics. Implement Sci. 2012 Apr 11;7(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute of Medicine. Crossing The Quality Chasm: A New Health System For The 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chinman M, Young AS, Schell T, et al. Computer-assisted self-assessment in persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004 Oct;65(10):1343–1351. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chinman M, Hassell J, Magnabosco J, et al. The feasibility of computerized patient self-assessment at mental health clinics. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007 Jul;34(4):401–409. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0120-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolotkin RL, Corey-Lisle PK, Crosby RD, et al. Impact of obesity on health-related quality of life in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008 Apr;16(4):749–754. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiden PJ, Newcomer JW, Loebel AD, et al. Long-Term Changes in Weight and Plasma Lipids during Maintenance Treatment with Ziprasidone. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007 Jul 18; doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colton C, Manderscheid R. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis [serial online] 2006 http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2006/apr/05_0180.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Auquier P, Lancon C, Rouillon F, et al. Mortality in schizophrenia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007 Dec;16(12):1308–1312. doi: 10.1002/pds.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007 Oct;64(10):1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newcomer JW, Hennekens CH. Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2007 Oct 17;298(15):1794–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holt RI, Abdelrahman T, Hirsch M, et al. The prevalence of undiagnosed metabolic abnormalities in people with serious mental illness. J Psychopharmacol. 2010 Jun;24(6):867–873. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vreeland B, Minsky S, Menza M, et al. A program for managing weight gain associated with atypical antipsychotics. Psychiatr Serv. 2003 Aug;54(8):1155–1157. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.8.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown C, Goetz J, Hamera E. Weight loss intervention for people with serious mental illness: a randomized controlled trial of the RENEW program. Psychiatr Serv. 2011 Jul;62(7):800–802. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.7.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu MK, Wang CK, Bai YM, et al. Outcomes of obese, clozapine-treated inpatients with schizophrenia placed on a six-month diet and physical activity program. Psychiatr Serv. 2007 Apr;58(4):544–550. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niv N, Cohen AN, Hamilton A, et al. Effectiveness of a Psychosocial Weight Management Program for Individuals with Schizophrenia. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2012 Mar 20; doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9273-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, et al. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012 Mar;50(3):217–226. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown AH, Cohen AN, Chinman M, et al. EQUIP: Implementing Chronic Care Principles and Applying Formative Evaluation Methods to Improve Care for Schizophrenia. Implementation Science. 2008;3(9) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yano EM. Managed care performance of VHA primary care delivery systems. Washington, D. C.: Health Services Research and Development Service, Veterans Health Administration; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weeks WB, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV. Primary care practice management in rural and urban Veterans Health Administration settings. J Rural Health Spring. 2002;18(2):298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2002.tb00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jan S, Mooney G, Ryan M, et al. The use of conjoint analysis to elicit community preferences in public health research: a case study of hospital services in South Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2000 Feb;24(1):64–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2000.tb00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young AS, Sullivan G, Burnam MA, et al. Measuring the quality of outpatient treatment for schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55(7):611–617. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, et al. Structured Clinical Interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Patient Edition, Version 2.0. New York, NY: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ventura J, Lukoff D, Nuechterlein KH, et al. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) expanded version (4.0): scales, anchor points and administration manual. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1993;3:227–243. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neter J. Applied Linear Statistical Models. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 1996. [Google Scholar]