Abstract

Objective

This study describes the 5 years’ results of the Sciatica trial focused on pain, disability, (un)satisfactory recovery and predictors for unsatisfactory recovery.

Design

A randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Nine Dutch hospitals.

Participants

Five years’ follow-up data from 231 of 283 patients (82%) were collected.

Intervention

Early surgery or an intended 6 months of conservative treatment.

Main outcome measures

Scores from Roland disability questionnaire, visual analogue scale (VAS) for leg and back pain and a Likert self-rating scale of global perceived recovery were analysed.

Results

There were no significant differences between groups on the 5 years’ primary outcome scores. Despite at least 6 months of conservative treatment 46% of the conservatively allocated patients were treated surgically because of severe leg pain and disability. Forty-nine (21%) patients had an unsatisfactory recovery at 5 years and the recovery pattern showed that there was a variable group of 66 patients (31%) with at least one unsatisfactory outcome at 1, 2 or 5 years of follow-up. Multivariate logistic regression showed that age (>40; OR 2.42 (95% CI 1.16 to 5.02)), severity of leg pain (VAS >70; OR 3.32 (95% CI 1.69 to 6.54)) and the Mc Gill affective score (score >3; OR 6.23 (95% CI 2.23 to 17.38)) were the only significant predictors for an unsatisfactory outcome at 5 years.

Conclusions

In the long term, 8% of the patients with sciatica never showed any recovery and in at least 23%, sciatica appears to result in ongoing complaints, which fluctuate over time, irrespective of treatment. Prolonged conservative care might give patients a fair chance for pain and disability to resolve without surgery, but with the risk to receive delayed surgery after prolonged suffering of sciatica. Age above 40 years, severe leg pain at baseline and a higher affective Mc Gill pain score were predictors for unsatisfactory recovery. Trial Registry ISRCT No 26872154.

Keywords: Neurosurgery

Article summary.

Article focus

The sciatica trial, a randomised controlled trial, showed no significant differences after 1 and 2 years of follow-up in disability and pain between patients with severe sciatica for 6–8 weeks, allocated for either early surgery or 6 months of prolonged conservative care.

Twenty per cent of all patients reported an unsatisfactory recovery after 2 years. In this study the 5 years’ follow-up is described and predictors for unsatisfactory recovery are identified.

Key messages

Eight per cent of all patients never showed any recovery.

In 23% of all patients sciatica results in ongoing complaints, which fluctuate over time, irrespective of treatment.

A strategy of prolonged conservative care with eventually delayed surgery gives a high chance of pain and disability to resolve, although 46% of these patients needed surgery after a few more months of prolonged suffering.

Age over 40 years, severe leg pain at baseline and a higher affective McGill pain score were predictors for an unsatisfactory recovery.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Five years follow-up results of a randomised controlled trial.

Eighteen per cent of the patients were lost to follow-up at 5 years.

No difference in baseline characteristics between dropouts and patients providing the 5 years’ data.

Introduction

The lumbosacral radicular syndrome (LSRS), caused by a herniated lumbar disc, is one of the most expensive disorders for society in terms of work absenteeism and disability.1 In 2007, the Sciatica Trial showed that the clinical outcome after 1 year was not different from prolonged conservative treatment, although recovery within the first year was better with early surgery.2 In the prolonged conservative treatment group, however, 39% of patients crossed over to surgical treatment because of intractable pain within 1 year and 44% within 2 years of follow-up.3 Despite the fact that this study showed, along with other randomised controlled trials,4–7 that a strategy of prolonged conservative care is safe and reduces the risk for patients undergoing surgery, the optimal timing of surgery with regard to long-term outcome has still not been defined.

Although LSRS is described in the literature as having a quite favourable course, one might question this assumption as the 2 years’ follow-up showed that about 20% of patients report an unsatisfactory outcome on all outcome scales and that the risk to suffer prolonged disability is higher than expected beforehand.2 3

The primary aim of the present study was to compare the pain and disability scores at 5 years’ follow-up between patients in the Sciatica Trial randomised for surgery or randomised for prolonged conservative treatment. The second aim was to evaluate the proportion of patients with an unsatisfactory recovery at 5 years’ follow-up and to identify factors contributing to these unsatisfactory results.

Material and methods

Design

The study is part of the Sciatica Trial, a multicentre, prospective randomised trial among patients with 6–12 weeks of sciatica to determine whether a strategy of early surgery leads to better outcomes during the first year than does a strategy of prolonged conservative treatment for an additional 6 months followed by surgery for those patients who do not improve.

In summary, patients, 18–65 years of age, with an LSRS with a concomitant disc herniation confirmed by MRI, were eligible for participation. A computer-generated permuted-block scheme was used for randomisation stratified by centre. In the surgical intervention group, a disc herniation removal through a unilateral transflaval approach using optical magnification was performed. Prolonged conservative treatment regimen was defined by general practitioners and treatment was mainly aimed at resuming daily activities. Patients were notified beforehand that they were participating in a study comparing two different strategies for the timing of intervention rather than comparing surgery with non-surgical treatment.

The design and study protocol have been published previously.2 8 Baseline characteristics from the Sciatica Trial have been published previously2 3 and were combined with the findings obtained from the 5 years’ follow-up of the participants.

Procedures

As a standard procedure, the participants received the same study questionnaires as used for the 1-year and 2-year follow-up every year. At approximately 5 years after the study inclusion, the participants were contacted once again by mail, but now with an accompanied letter and asked to fill out the study questionnaires as used for the 1 and 2 years’ follow-up with extra-questions about reoperations. Patients who did not respond initially were contacted by telephone by a research nurse and asked once again to participate in the study by filling out the questionnaires. The additional 5 years’ assessment was approved by the local medical ethics committee.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcome measures consisted of the Roland disability questionnaire (RDQ) for sciatica,9 a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS) for leg pain,10 and a seven-point Likert score of global perceived recovery. Higher RDQ and VAS scores were indicative of the experience of worse disability or greater intensity of pain, respectively. Global perceived recovery was measured with a seven-point Likert self-rating scale. Complete or almost complete disappearance of complaints (Likert scores 1–2) was defined as the ‘satisfactory recovery’, whereas Likert scores 3–7 were defined as ‘unsatisfactory recovery’.2 8

Secondary outcomes were a 100 mm VAS for back pain and the number of (re)operations for severe sciatica in the interval between 2 and 5 years. The number of (re)operations for severe sciatica was evaluated by asking the patients whether there had been any new operations for severe sciatica in the interval between 2 and 5 years. Additionally, in all participating centres, it was checked whether patients had had a treatment because of sciatica in the intervening period.

Potential prognostic factors

The prognostic value of demographic and clinical baseline variables for unsatisfactory recovery at 5 years was evaluated. The initial list of prognostic factors, chosen in advance by the investigators, was based on potential clinical importance, as indicated by earlier clinical results11–13 The following potential prognostic demographic variables were included in the analysis: age (dichotomised <40/≥40), gender, smoking status, body mass index (BMI) (dichotomised <25/≥25), physical job (yes/no) or mentally demanding job (yes/no).

The following clinical baseline variables were included in the analysis: level of herniation at the MRI, the presence of a sequester on MRI (yes/no), sciatica provoked by sitting (yes/no), sciatica provoked by coughing/sneezing (yes/no), outcome of Bragard's test (positive/negative) and sensory disturbance (yes/no).

Furthermore, the following measurement instruments for general health, mental health, affective score and pain were included: the VAS scores for leg pain, back pain and general health, the Mental Health subscore of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-Item Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-36),14 and the McGill affective score.2 The VAS score range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. For this analysis, dichotomised VAS scores were used (<70/≥70), as described in an earlier study.2 The SF-36 Mental Health score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating less severe symptoms. For this analysis, dichotomised SF-36 Mental Health subscores were used (scores below 1 SD of the Dutch reference population1 were defined as impaired). The McGill affective score measures the qualitative perception of pain by the patient and ranges from 0 to 5 where a high score (3–5) is correlated with a more depressed and anxious mood. For this analysis, dichotomised McGill affective scores were used (<3/≥3).2

Statistical analysis

The original sample size calculation was based on a difference in RDQ outcome during and in a different speed to recovery during the first year. The main endpoint ‘recovery’ is in principle time-dependent in the sense that it reflects the situation of a patient at a particular moment in time and the situation may also deteriorate afterwards, so it can change from recovered to non-recovered and back to recovered again, therefore actually being a time-varying dichotomous outcome which should be taken into account when interpreting the results of the analyses. Differences between randomisation groups at baseline and after 5 years of follow-up were assessed by comparing means, medians or percentages, depending on the type of variable. Baseline values of variables were used as covariates in the main analyses whenever appropriate to adjust for possible differences between the randomised groups and to increase the power of the analyses. Outcomes of function and pain over the entire follow-up period were analysed using a repeated measurements analysis of variance with a first order autoregressive covariance matrix. Estimated consecutive scores were expressed as means and 95% CIs. Pointwise estimates were obtained using models with time as a categorical covariate to allow assessment of systematic patterns. Differences between groups in the dichotomised Likert score at 5 years were evaluated with Fisher's exact test (randomisation group) or Mann-Whitney U (disability and pain scores).

The analyses were done according to the intention-to-treat principle, except the comparison of groups with a satisfactory or unsatisfactory recovery.

Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate the prognostic value of baseline variables for an unsatisfactory outcome at 5 years. The results are presented as ORs with 95% CIs. χ² Tests were used to perform the univariate analyses. Potential predictors with a p<0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression. The multivariate logistic regression model was performed in a backward approach and included randomisation group irrespective of its significance in the univariate analysis, to control for its influence on the dependent variable.

For all other analyses, p<0.05 was considered significant. Data collection and quality checks were performed with the ProMISe web-based secure data management system of the Department of Medical Statistics and Bioinformatics of Leiden University Medical Centre. For all statistical analyses, SPSS V.18.0 was used.

Results

Fifty-two of the 283 patients (18%) were lost to follow-up, among them one patient who died after a cardiac bypass operation and 19 patients who refused to participate. The baseline characteristics age, gender, BMI, randomisation group, RDQ and VAS-scores were not significantly different between the dropouts and those patients providing the 5 years’ follow-up data. Twenty-six of the dropouts were randomised for early surgery. Among the 26 dropouts in the prolonged conservative group, 11 (42%) had surgery for sciatica during follow-up.

At 5 years’ follow-up, 66 of the 142 patients (46%) assigned to conservative treatment had had surgery because of intractable sciatica (table 1). Within the first year this was 55 (39%) and after 2 years 62 (44%). Of the 141 patients allocated for early surgery, 16 (11%) recovered before surgery and were not operated on during the 5 years of follow-up. Within this 5 years period, nine patients (7%) in the early surgery group and eight of the conservatively allocated patients who had surgery (12%) needed recurrent disc surgery. Three patients in the conservative group needed two reoperations or more (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline and follow-up characteristics of patients with sciatica

| Patient characteristics | Early surgery (n=141) | Conservative treatment (n=142) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 41.6 (10.0) | 43.3 (9.6) |

| Male sex | 89 (63) | 97 (68) |

| Mean (SD) BMI | 25.9 (4.1) | 25.5 (3.3) |

| Mean (SD) duration of sciatica (weeks) | 9.43 (2.37) | 9.48 (2.11) |

| Took sick leave from work | 107 (76) | 116 (82) |

| Mean (SD) duration of sick leave (weeks) | 5.32 (2.78) | 5.28 (2.62) |

| Left sided leg pain | 67 (48) | 73 (51) |

| Positive straight leg raising test (SLR) | 100 (71) | 104 (73) |

| Positive crossed SLR | 71 (50) | 70 (49) |

| Dermatomal sensory loss | 123 (87) | 128 (90) |

| Dermatomal anaesthesia | 31 (22) | 33 (23) |

| Dermatomal muscle weakness | 93 (66) | 99 (70) |

| Knee tendon reflex difference | 54 (38) | 51 (36) |

| Ankle tendon reflex difference | 75 (53) | 107 (75) |

| Clinically suspected level of herniated disc | – | – |

| L3–L4 | 6 (4) | 4 (3) |

| L4–L5 | 65 (46) | 52 (37) |

| L5–S1 | 70 (50) | 86 (61) |

| Preference for conservative treatment | 42 (30) | 43 (30) |

| Mean (SD) RD score | 16.5 (4.4) | 16.3 (3.9) |

| Mean (SD) VAS score | – | – |

| Leg pain | 67.3 (19.6) | 64.3 (21.2) |

| Back pain | 34.0 (29.6) | 30.8 (27.7) |

| Mean (SD) SF-36 scores | – | – |

| Bodily pain | 21.9 (16.6) | 23.9 (18.1) |

| Physical functioning | 33.9 (19.6) | 34.6 (19.0) |

| Surgical treatment during follow-up | ||

| Surgery performed in first year | 125 (89) | 55 (39) |

| Surgery performed during 2 years | 125 (89) | 62 (44) |

| Surgery performed during 5 years | 125 (89) | 66 (46) |

| Recurrent disc surgery after 5 years | 9 (6) | 8 (6) |

| Follow-up | 9 of 125 (7) | 8 of 66 (12) |

| Patients requiring two reoperations or more | 0 | 3 |

| Patients who dropped out during 5 year | 26 (18) | 26 (18) |

Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise.

BMI, body mass index; VAS, visual analogue scale.

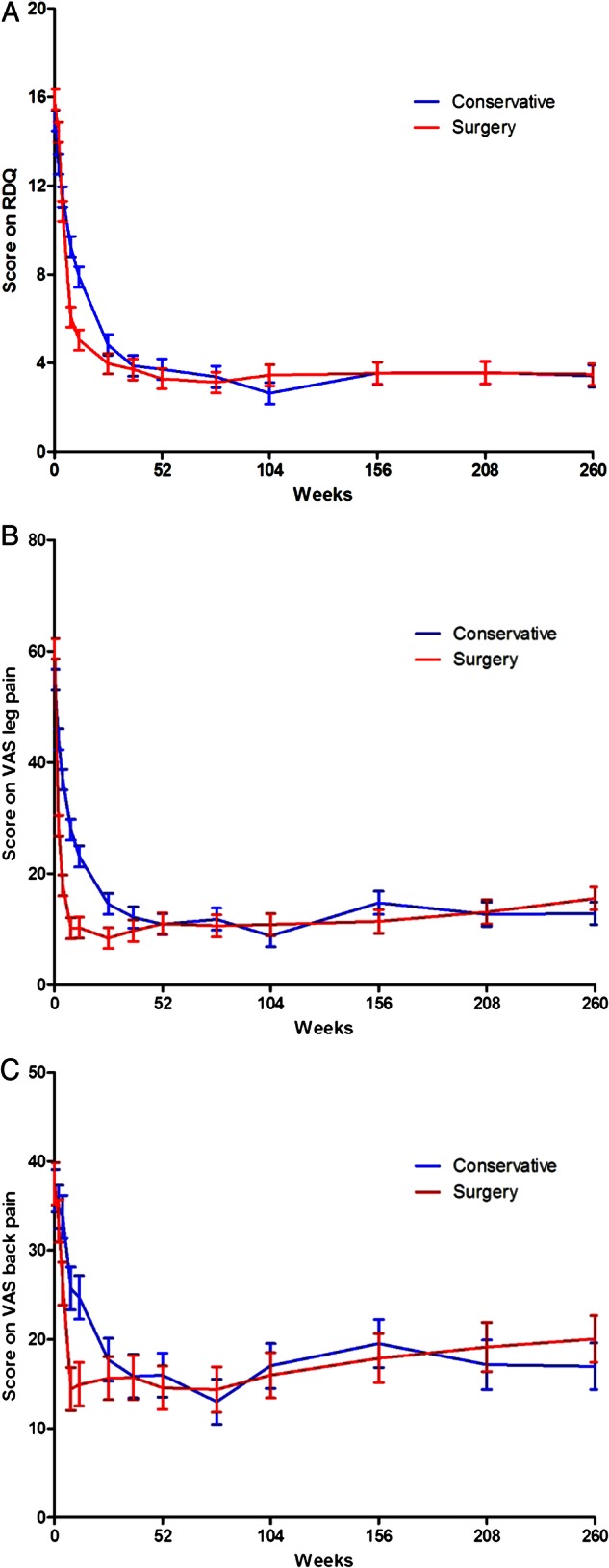

The primary and secondary outcome scores concerning disability, leg pain and back pain at 5 years were slightly higher in the early surgery group compared with the prolonged conservative group; however, there were no significant differences (table 2 and figure 1A–C).

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes from early surgery (ES) versus prolonged conservative treatment (CT) for patients with sciatica

| 8 weeks |

52 weeks |

104 weeks |

260 weeks |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | ES | PCT | Difference (95% CI) | ES | PCT | Difference (95% CI) | ES | PCT | Difference (95% CI) | ES | PCT | Difference (95% CI) |

| Disability* | 6.1 (0.5) | 9.2 (0.5) | 3.2 (1.9 to 4.4) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 0.4 (−0.8 to 1.7) | 3.4 (0.5) | 2.6 (0.5) | −0.8 (−2.1 to 0.5) | 3.5 (0.5) | 3.4 (0.5) | −0.1 (−1.4 to 1.3) |

| Leg pain† | 10.2 (1.9) | 27.9 (1.9) | 17.7 (12.5 to 22.9) | 11.0 (1.9) | 10.9 (1.9) | −0.1 (−5.3 to 5.1) | 10.9 (2.0) | 8.8 (2.0) | −2.0 (−7.5 to 3.4) | 15.6 (2.0) | 12.8 (2.0) | −2.7 (−8.4 to 2.9) |

| Back pain† | 14.4 (2.4) | 25.7 (2.4) | 11.3 (4.6 to 18.0) | 14.6 (2.4) | 16.0 (2.4) | 1.4 (−5.3 to 8.2) | 16.0 (2.6) | 17.0 (2.5) | 1.0 (−6.0 to 8.1) | 20.0 (2.6) | 17.0 (2.6) | −3.1 (−10.3 to 4.2) |

*Roland disability questionnaire for sciatica. Score ranges from 0 to 23, with higher scores representing worse disability.

†Measured on a 100 mm visual analogue scale, with 0 representing no pain and 100 the worst pain ever experienced.

Values are means (SE) unless stated otherwise and are based on intention to treat, CI assessed with repeated measurements analysis.

Figure 1.

(A–C) Repeated measurement analysis curves of mean scores for Roland disability questionnaire (top panel) and visual analogue scales for leg pain and back pain (lower panels).

In the total group, after 5 years, 49 (21%) patients still had an unsatisfactory recovery, defined as not having a complete or almost complete recovery on the dichotomised Likert scale, irrespective of their allocated treatment group (25 patients in the prolonged conservative group, 24 patients in the early surgery group, p=1.00).

Patients with an unsatisfactory recovery had a significantly higher amount of leg pain, back pain and disability (all p values <0.01) compared with the group with a satisfactory recovery (table 3). At 5 years’ follow-up, 93 patients (62 men and 31 women, mean age 43.7, SD 9.8) had not had surgery (76 from the conservative group and 16 from the early surgery group) and the percentage recovered (77%) or not-recovered at 5 years (23%) was not different from the total group.

Table 3.

Primary and secondary outcome scores among patients treated for sciatica according to perceived recovery at 5 years

| Disability* |

Leg pain† |

Back pain† |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) |

| Unsatisfactory recovery (n=49)‡ | 11.3 (5.6) | 11.0 (6.5–15.5) | 42.8 (27.9) | 46.0 (17.5–66.0) | 48.6 (49.5) | 49.5 (32.0–66.75) |

| Satisfactory recovery (n=182)‡ | 1.3 (2.3) | 0.0 (0.0–2.0) | 6.5 (13.7) | 1.0 (0.0–6.0) | 10.2 (14.6) | 4.0 (0.0–15.0) |

*Roland disability questionnaire for sciatica.

†Measured on a 100 mm analogue scale.

‡The seven-point Likert scale of global perceived recovery was dichotomised to satisfactory outcome (‘complete’ and ‘nearly complete’ recovery) and unsatisfactory outcome (the other 5 scores ranging from ‘some recovery’ to ‘severe worsening of complaints’).

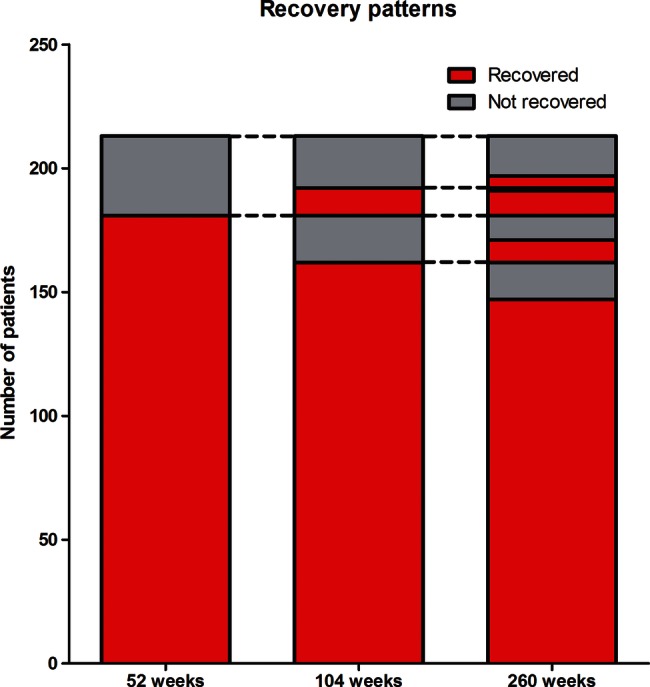

In the period of 5 years, 66 of the 213 patients (31%) with collected data at one, 2 and 5 years of follow-up had at least one period of unsatisfactory recovery. The pattern of recovery showed 16 patients who did not report any recovery at 1, 2 and 5 years of follow-up. Twenty-four patients switched from ‘not recovered’ in the first or second year to ‘recovered’ at the 5 years’ analysis. Sixteen of these patients were from the prolonged conservative group. Six of these patients needed an operation of whom four needed a reoperation before they recovered, compared with two of the eight patients in the early surgery group needing a reoperation. Twenty-six patients showed a good recovery at 1 and/or 2 years but not at 5 years of follow-up (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patterns of recovery between results of the 1, 2 and 5 years’ analyses with a dichotomised Likert score for perceived recovery.

Univariate logistic regression evaluating the relationship between possible prognostic variables and unsatisfactory recovery at 5 years, irrespective of intermediate recovery, showed that a high McGill affective score (score >3; OR 6.23 (95% CI 2.23 to 17.38)) was a significant predictor, as were severe leg pain at baseline (VAS >70; OR 2.95 (95% CI 1.54 to 5.64), an impaired score on the SF-36 Mental Health subscale (OR 2.25 (95% CI 1.16 to 4.35)), higher age (age >40; OR 2.22 (95% CI 1.11 to 4.47)) and a positive Bragard test (OR 1.91(95% CI 0.97 to 3.74); table 4). The multivariate analysis included all variables that were related to unsatisfactory outcome in the univariate analysis (p<0.10), as well as randomisation group. This analysis showed that a high McGill affective score (score >3; OR 4.48 (95% CI 1.43 to 14.08)), severity of leg pain (VAS >70; OR 2.80 (95% CI 1.39 to 5.62)) and age (age >40 years; OR 2.36 (95% CI 1.12 to 5.00)) were the only significant predictors for an unsatisfactory outcome at 5 years.

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariate logistic analysis of predicting factors for unsatisfactory outcome of sciatica

| Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| Randomisation | |||||||

| Surgery | 115 | 0.96 | 0.51 to 1.80 | 0.899 | |||

| Conservative | 116 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 75 | 1.27 | 0.66 to 2.46 | 0.472 | |||

| Male | 156 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Age | |||||||

| ≥40 | 137 | 2.22 | 1.11 to 4.47 | 0.023 | 2.36 | 1.11 to 5.00 | 0.024 |

| <40 | 94 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Mentally demanding job | |||||||

| Yes | 139 | 1.17 | 0.57 to 2.37 | 0.669 | |||

| No | 76 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Physical job | |||||||

| Yes | 85 | 1.39 | 0.71 to 2.70 | 0.339 | |||

| No | 132 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Smoking | |||||||

| Yes | 84 | 1.09 | 0.57 to 2.09 | 0.792 | |||

| No | 142 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| BMI | |||||||

| ≥25 | 125 | 1.19 | 0.62 to 2.29 | 0.605 | |||

| <25 | 101 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Sciatica provoked by sitting | |||||||

| Yes | 180 | 0.73 | 0.35 to 1.51 | 0.397 | |||

| No | 51 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Coughing, sneezing | |||||||

| Yes | 163 | 1.06 | 0.53 to 2.12 | 0.881 | |||

| No | 68 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Bragard's test | |||||||

| Positive | 62 | 1.91 | 0.97 to 3.74 | 0.059 | |||

| Negative | 154 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| Sensory disturbance | |||||||

| Yes | 200 | 1.45 | 0.47 to 4.47 | 0.514 | |||

| No | 24 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| VAS leg pain | |||||||

| ≥70 | 89 | 2.95 | 1.54 to 5.64 | 0.001 | 2.80 | 1.39 to 5.62 | 0.004 |

| <70 | 142 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| VAS back pain | |||||||

| ≥70 | 34 | 1.68 | 0.74 to 3.80 | 0.211 | |||

| <70 | 196 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| McGill affective score | |||||||

| High (3–5) | 17 | 6.227 | 2.23 to 17.38 | <0.001 | 4.48 | 1.43 to 14.08 | 0.010 |

| Low (0–2) | 209 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| MRI-level herniation | |||||||

| L5S1 | 125 | 0.69 | 0.37 to 1.31 | 0.256 | |||

| L3L4/L4L5 | 106 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| MRI-sequester | |||||||

| Yes | 84 | 0.85 | 0.43 to 1.68 | 0.643 | |||

| No | 122 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| SF-36 mental health* | |||||||

| Impaired | 66 | 2.25 | 1.16 to 4.35 | 0.014 | |||

| Not impaired | 163 | 1.00 | – | ||||

| VAS general health | |||||||

| ≥70 | 60 | 1.36 | 0.68 to 2.74 | 0.382 | |||

| <70 | 168 | 1.00 | – | ||||

Only the numbers of the potential predictors with a p<0.10 in the univariate analysis were shown in the multivariate logistic regression.

*The scores on the SF-36 Mental Health subscale were dichotomised using 1 SD below the Dutch reference population.

BMI, body mass index; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Discussion

This long-term follow-up study of the same patient cohort corroborates with earlier 1-year and 2-year results as no significant differences between randomisation groups in disability, leg pain or back pain are found after 5 years of follow-up.2 3 Eighteen per cent of the initial cohort of 283 patients was lost to follow-up after 5 years. This reduced the power of our latest analysis to some extent. However, the baseline characteristics showed no differences between the included group and the dropouts.

The allocated strategy of an extra 6 months of wait-and-see resulted in a large proportion of delayed surgical treatment (46%) for persistent intense leg pain causing severe disability, despite all kinds of conservative treatment. This means that patients should be informed that prolonged conservative care gives them quite a high chance for resolution of pain and disability without the need of a surgical intervention, but that this strategy also carries a fair chance (46%) that this waiting for the pain to resolve will still end with them needing disc surgery.

The question, however, is whether this conclusion is completely accurate. The design of the original study was a comparison of early surgery versus prolonged conservative care for 6 months, after which the surgery was offered when there still were severe complaints. This means that we do not know the precise percentage of patients who would have become pain free with even longer conservative care, because the majority of these patients were operated on after 6 months. But, on the other hand, one might question whether such a proposed long-conservative regimen is in proportion with the small risk of a surgical intervention, which provides a better outcome in the first 6 months, rather than being disabled in daily life during this long period of conservative care. Furthermore, the proportion of patients who were not operated after 5 years with a satisfactory or unsatisfactory recovery was the same as in the total population, showing that also in the non-operated patients there was a rather high amount of unsatisfactory recovery.

Twenty-one per cent of patients experienced unsatisfactory recovery at 5 years, while 31% of the patients with complete data at 1, 2 and 5 years of follow-up noted at least once an unsatisfactory recovery during this 5 years’ follow-up period, irrespective of their allocated group. So, the optimal timing of surgery is still on debate, as is the question which patients would benefit from surgery and which from prolonged conservative care.

The study design of this 5 year analysis did not permit us to look properly for the causes of an unsatisfactory recovery. A shortcoming of this study is the fact that there was no permission in the present study to retrieve new MRI, but a recent study with the same patient population did not show any correlation between MRI and satisfactory or unsatisfactory recovery at 1 year.15

The patterns of recovery show that 8% of all patients with collected data had never had any recovery during the follow-up period, showing that there are not that many non-responders of conservative or surgical treatment. The other 50 patients (23%) with an unsatisfactory recovery showed a switch over time from recovered to not-recovered, or vice versa. This is in line with the idea that sciatica is caused by chronic disc disease with intermittent nerve compression or inflammation and that pain can thus reoccur despite any earlier treatment.16 17 In the 24 patients who switched from ‘not-recovered’ in the first or second year to ‘recovered’ at the 5-years’ analysis, there was a higher amount of patients who needed a reoperation before recovery occurred in the prolonged conservative group compared with the early surgery group. This may be caused by less effectiveness of late surgery, although this could not be proven. This less effectiveness of late surgery compared with early surgery could be caused by more chronic changes around the disc protrusion or sequester, causing more difficulty in freeing the nerve from compression.

In our study, we could not estimate the effect of early versus late surgery, or surgery versus conservative treatment in an unbiased way since that would require a per protocol analysis. This would ignore the randomised allocation and compare patients who by definition would be incomparable since the design of our study did not envisage a randomisation between early and late surgery, but merely allowed for the time of surgery being determined by the assessment of both patient and physician after initial randomisation. The impossibility to capture completely the condition of the patient and the selection mechanism which leads to the decision to operate, or not, at any given point in (follow-up) time, renders any multivariate analysis that attempts to make the groups of early and late operations comparable, biased. This bias has occurred in other randomised studies where this ‘per protocol’ analysis was used and patients who were operated on after a prolonged duration of symptoms from a herniated lumbar disk have been shown to have a worse outcome than patients who were operated on relatively early.18–21 As a consequence of this E “per protocol analysis both groups differed in baseline characteristics such as type of disc herniation, neurological deficit and reported depression, rendering comparison of both groups fallacious.”21

In this 5-year analysis the independent prognostic factors for an unsatisfactory outcome were a high McGill affective score, a high amount of leg pain and age over 40 years at baseline. A high McGill affective score correlates with a more depressed and anxious mood,2 and mental stress, depression or other psychological factors have been widely described as risk factors for development of chronic pain.22 Although a high amount of pain at baseline can also be caused by psychological factors, it is an independent prognostic factor for an unsatisfactory outcome in this study. Perhaps the severity of nerve root compression at intake predicts the overall outcome, but a correlation between amount of pain and amount of root compression has not been proven.23 In our study, other factors concerning the severity of nerve root damage, such as severe sensibility disturbance, showed no association. In a systematic review of non-surgically treated sciatica, none of the three studies that investigated baseline leg pain severity showed a clear prognostic influence on outcome. Age was also not found to be a prognostic factor in six of seven studies.24 The reason for age over 40 years being a prognostic indicator for a unsatisfactory outcome could be because disc herniation is part of a degenerative disease which seems to worsen in time. A study of prognostic factors for unsatisfactory recovery among operated and unoperated patients did not show leg pain severity and age to be a prognostic factor, but found the variables severe back pain and male gender as predictors for a bad outcome at the 1-year follow-up.24 25 This was in contrast with our 1-year study where being woman was a prognostic factor for a bad outcome, but in this 5 years’ analysis this also disappeared. The possible prognostic role of gender might be overestimated in the past.

Conclusion

After 5 years of follow-up, there were still no differences in pain and disability between the patients randomised for early surgery or prolonged conservative care.

Signs of pain quality associated with depression and a more anxious mood, the age of the patient and the severity of leg pain at baseline were predictive of an unsatisfactory outcome.

In general, patients must be informed that prolonged conservative care might give them a fair chance for pain and disability to resolve without surgery, but with the risk for delayed surgery in the end after a prolonged period of suffering from sciatica.

Furthermore, although the total number of disabled patients without pain free periods in this study seems to be low, in almost one-fourth of the patients, sciatica appears to be an ongoing disease with variable complaints in time, irrespective of treatment. These patients need our full attention, and further investigation at 10 years’ follow-up is being planned, because this patient category has the highest burden on society concerning work absenteeism and general health costs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Collaborators: The participants in the Leiden-The Hague Spine Intervention Prognostic Study Group were: protocol committee, WCP, BWK and RTWMT; steering committee, BWK, RTWMT, JAH Eekhof, JTJ Tans, WBvdH, WCP, RB, and HC van Houwelingen; statistical analysis, WBvdH; research nurses and data collection and management, M Nuyten, P Bergman, G Holtkamp, S Dukker, A Mast, L Smakman, C Waanders, L Polak, A Nieborg; coordinating physicians of participating hospitals, JTJ Tans, R Walchenbach (Medical Center Haaglanden, The Hague), J van Rossum, P Schutte, RTWMT (Diaconessen Hospital, Leiden), GAM Verheul, JE Dalman, JAL Wurzer (Groene Hart Hospital, Gouda), JWA Sven, A Kloet (Reinier de Graaf Hospital, Delft/Voorburg), ISJ Merkies, H van Dulken (Spaarne Hospital, Heemstede/Haarlem), PCLA Lambrechts, JAL Wurzer (Bronovo Hospital, The Hague), RWM Keunen, CFE Hoffmann (Haga Hospital, The Hague), J Haan, H van Dulken (Rijnland Hospital, Leiderdorp/Alphen ad Rijn), R Groen, RRF Kuiters (Lange Land Hospital, Zoetermeer), RAC Roos, JHC Voormolen (Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden), JAH Eekhof (Public Health and Primary Care, Leiden University, Leiden). WCP is guarantor for the study. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributors: WCP, RB, GJB and MBL conceived the idea of this follow-up study and were responsible for the design of the study. MBL, DV, WCHJ and RB were responsible for collecting the data, data analysis and MBl, DV and RB were responsible for tables and graphs. WCP, WPV, GJB and WCHJ provided input in the data analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by MBL and DV and then circulated repeatedly among all authors for critical revision. MBL, DV, WCHJ and RB were responsible for the acquisition of the data and WCP, WPV, GJB, RB, DV and MBL contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing Interests: None.

Ethics approval: Medical ethic commission LUMC.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: WCP, BWK, RTWMT, JAH Eekhof, JTJ Tans, WBvdH, RB, HC van Houwelingen, M Nuyten, P Bergman, G Holtkamp, S Dukker, A Mast, L Smakman, C Waanders, L Polak, A Nieborg, R Walchenbach, J van Rossum, P Schutte, GAM Verheul, JE Dalman, JAL Wurzer, JWA Sven, ISJ Merkies, H van Dulken, PCLA Lambrechts, JAL Wurzer, RWM Keunen, CFE Hoffmann, J Haan, H van Dulken, R Groen, RRF Kuiters, RAC Roos, and JHC Voormolen

References

- 1.van Tulder MW, Koes BW, Bouter LM. A cost-of-illness study of back pain in the Netherlands. Pain 1995;62:233–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peul WC, Van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med 2007;356:2245–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peul WC, van den Hout WB, Brand R, et al. Prolonged conservative care versus early surgery in patients with sciatica caused by lumbar disc herniation: two year results of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;336:1355–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs WC, van TM, Arts M, et al. Surgery versus conservative management of sciatica due to a lumbar herniated disc: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 2011;20:513–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) observational cohort. JAMA 2006;296:2451–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinstein JN, Tosteson TD, Lurie JD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disk herniation: the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT): a randomized trial. JAMA 2006;296:2441–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: four-year results for the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). Spine 2008;33:2789–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peul WC, Van Houwelingen HC, van der Hout WB, et al. Prolonged conservative treatment or ‘early’ surgery in sciatica caused by a lumbar disc herniation: rationale and design of a randomized trial [ISRCT 26872154]. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2005;6:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick DL, Deyo RA, Atlas SJ, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with sciatica. Spine 1995;20:1899–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. The visual analogue pain intensity scale: what is moderate pain in millimetres? Pain 1997;72:95–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hurme M, Alaranta H. Factors predicting the result of surgery for lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. Spine 1987;12:933–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peul WC, Brand R, Thomeer RT, et al. Influence of gender and other prognostic factors on outcome of sciatica. Pain 2008;138:180–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vroomen PC, de Krom MC, Knottnerus JA. Predicting the outcome of sciatica at short-term follow-up. Br J Gen Pract 2002; 52:119–23 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ 1992;305:160–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.el BA, Vleggeert-Lankamp CL, Nijeholt GJ, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in follow-up assessment of sciatica. N Engl J Med 2013;368:999–1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omarker K, Myers RR. Pathogenesis of sciatic pain: role of herniated nucleus pulposus and deformation of spinal nerve root and dorsal root ganglion. Pain 1998;78:99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulleman D, Mammou S, Griffoul I, et al. Pathophysiology of disk-related sciatica. I—evidence supporting a chemical component. Joint Bone Spine 2006;73:151–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonsson B. Patient-related factors predicting the outcome of decompressive surgery. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1993;251:69–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng LC, Sell P. Predictive value of the duration of sciatica for lumbar discectomy. A prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:546–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nygaard OP, Kloster R, Solberg T. Duration of leg pain as a predictor of outcome after surgery for lumbar disc herniation: a prospective cohort study with 1-year follow up.[see comment]. J Neurosurg Pediatrics 2000;92(Suppl 2):131–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rihn JA, Hilibrand AS, Radcliff K, et al. Duration of symptoms resulting from lumbar disc herniation: effect on treatment outcomes: analysis of the Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93:1906–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, et al. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine 2002; 27:E109–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1055–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashworth J, Konstantinou K, Dunn KM. Prognostic factors in non-surgically treated sciatica: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haugen AJ, Brox JI, Grovle L, et al. Prognostic factors for non-success in patients with sciatica and disc herniation. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.