Abstract

Objectives

Determine whether body mass index (BMI) and physical activity (PA) above, at or below MET minute per week (MMW) levels recommended in the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines interact or have additive effects on interleukin (IL)-6, C reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, interleukin6 (IL-6) soluble receptor (IL-6sr), soluble E-selectin and soluble intracellular adhesion molecule (sICAM)-1.

Design

Archived cohort data (n=1254, age 54.5±11.7 year, BMI 29.8±6.6 kg/m2) from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the USA (MIDUS) Biomarkers Study were analysed for concentrations of inflammatory markers using general linear models. MMW was defined as no regular exercise, <500 MMW, 500–1000 MMW, >1000 MMW and BMI was defined as <25, 25–29.9, ≥30 kg/m2. Analyses were adjusted for age, sex, smoking and relevant medication use.

Setting

Respondents reported to three centres to complete questionnaires and provide blood samples.

Participants

Participants were men and women currently enroled in the MIDUS Biomarker Project (n=1254, 93% non-Hispanic white, average age 54.5 years).

Primary outcome measures

Concentration of serum IL-6, CRP, fibrinogen, IL-6sr, sE-selectin and sICAM.

Results

Significant interactions were found between BMI and MMW for CRP and sICAM-1 (p<0.05). CRP in overweight individuals was similar to that in obese individuals when no PA was reported, but it was similar to normal weight when any level of regular PA was reported. sICAM-1 was differentially lower in obese individuals who reported >1000 MMW compared to obese individuals reporting less exercise.

Conclusions

The association of exercise with CRP and sICAM-1 differed by BMI, suggesting that regular exercise may buffer weight-associated elevations in CRP in overweight individuals while higher levels of exercise may be necessary to reduce sICAM-1 or CRP in obese individuals.

Keywords: Epidemiology

Article summary.

Article focus

Systemic inflammation is related to the progression of cardiovascular disease.

Independent of obesity, physical activity is inversely related to concentrations of well-established inflammatory biomarkers, such as C reactive protein (CRP) or interleukin-6 (IL-6).

This article evaluates the interactive effects of body mass index and physical activity on the established inflammatory markers, CRP and IL-6, and emerging inflammatory markers, fibrinogen, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule (sICAM)-1, soluble E-selectin and IL-6 soluble receptor.

Key messages

The interactive effects of body mass index and physical activity were observed for CRP, such that regular physical activity reported by overweight individuals was related to significantly lower CRP levels compared to those reporting no regular activity.

Independent of BMI, regular physical activity was related to lower IL-6, with a trend for lower fibrinogen.

Physical activity had no independent effect on circulating markers related to endothelial inflammation, such as sICAM-1 or sE-selectin.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A total of 1254 adults from the National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS) Biomarker Project were analysed. Statistical analyses were adjusted for age, sex, smoking and relevant medication use. The strength of this paper is categorising physical activity levels based on national recommendations. These data may be used to determine the appropriate levels of physical activity necessary for reducing inflammation in overweight and obese adults. However, cross-sectional data are limited, as causal inferences cannot be obtained. A second limitation is that the sample was predominantly comprised of non-Hispanic white individuals, and therefore the findings may not extend to all ethnicities.

Introduction

Obesity paired with low physical activity is well known to increase morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular disease (CVD).1 It is less clear, however, whether the benefits of higher levels of physical activity differ among normal weight, overweight and obese individuals.

Chronic, low-grade inflammation, marked by elevations in cytokines, acute phase reactants and soluble adhesion molecules, is a developing CVD risk factor.2 3 Circulating interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C reactive protein (CRP) are both considered to be established inflammatory markers related to CVD.3 Fibrinogen, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule (sICAM-1) and soluble e-selectin (sE-selectin) also have key roles in the progression of CVD and have been associated with elevated risk.4–6 Obesity is strongly associated with greater concentrations of inflammatory markers.7 8 Further, body fat distribution is also an important factor relating to inflammatory status. Accumulation of fat in visceral depots is more strongly associated with low-grade inflammation compared to accumulation of fat in subcutaneous or hip-region depots.9 10

The effects of physical activity on markers of inflammation are more complex and may vary depending on body weight. A number of epidemiological studies have shown an inverse relationship between physical activity and CRP and IL-6, independent of obesity.11–16 Laboratory studies conducted in aerobically trained, typically normal weight individuals have demonstrated that a single bout of exercise stimulates IL-6 release from skeletal muscle, which promotes anti-inflammatory effects,17–19 as opposed to adipose tissue-derived IL-6 that is associated with proinflammatory effects.20 Randomised controlled trials have also been conducted, often in populations that also tend to be overweight or obese, to examine the effects of aerobic exercise interventions on inflammation and the results are mixed.21 Thus, the contribution of physical activity to inflammation in the context of obesity remains unclear.

The purpose of our study was to disentangle the relative contributions of BMI and physical activity recorded in MET minutes per week (MMW) to circulating levels of IL-6, IL-6sr, CRP, sICAM-1 and sE-selectin in middle-aged adults. MMW categories for this study were determined using values put forth by the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, which states that total weekly physical activity in the range of 500–1000 MET-minutes (approximately equivalent to 150–300 min of moderate or 75–150 min of vigorous activity per week) produces substantial health benefits for adults.22 We hypothesised that BMI and MMW would interact, such that the greater MMW reported would lessen the impact of obesity on markers of inflammation.

Materials and methods

Design and sample

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of archived data (BMI, self-reported physical activity and inflammatory biomarker concentrations) from 1254 respondents who provided consent (as approved by The University of Wisconsin Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board) and were subsequently enroled in the National Survey of Midlife Development in the USA (MIDUS) Biomarkers Study.23 The Biomarker Project was one of five projects within MIDUS II set up with the purpose of adding comprehensive biological assessments on a subsample of the MIDUS participants to further understand age-related differences in physical and mental health. Participants were eligible for The Biomarker Project if they were previously enroled in MIDUS and MIDUS II, which recruited non-institutionalised, English-speaking adults residing in the contiguous USA aged 25–74. Exclusion criteria included non-participation in MIDUS and MIDUS II and an unwillingness to travel to specified sites for biomarker assessment. The random digit dialling sample for the parent study was selected from working telephone banks, and a list of all individuals aged between 25 and 74 years within each household was generated in order to select a random respondent. Those who agreed to participate in the Biomarker Study stayed overnight at one of three General Clinical Research Centers: University of California Los Angeles, University of Wisconsin-Madison and Georgetown University. Upon arrival, each respondent provided a detailed medical history (including physical activity levels) and all prescription, over-the-counter and alternative medications to be inventoried by project staff. Following an overnight stay, morning fasting blood samples were obtained. Cohorts were assessed between July 2004 and May 2009 as a follow-up to MIDUS I respondents who were previously surveyed by the MacArthur Midlife Research Network between 1995 and 1996. Based on the MIDUS Biomarker Project sample of 1254 participants, 80% power was estimated to detect small effect sizes (δ=0.08 and higher) with an α level at 0.05 for a two-tailed test.24 25

Anthropometrics

Height was measured in centimetres and recorded to the nearest millimetre. A single measure of WC was taken directly on the skin or over a single layer of light, with close-fitting clothing at the narrowest point between the ribs and the iliac crest in centimetres to the nearest millimetre. Weight was measured in kilograms and BMI was calculated by dividing body mass in kilograms by height in metres squared. BMI categories were organised into three groups—normal weight (BMI ≤24.9 kg/m2), overweight (BMI≥25–29.9) and obese (BMI≥30).

Categorising physical activity by MET-minutes per week

The MMW variable was calculated using data provided in the medical history form. The form first described three types of regular physical activity

Vigorous: It causes your heart to beat so rapidly that you can feel it in your chest and you perform it long enough to work up a good sweat and breathe heavily (eg, competitive sports, running, vigorous swimming, high intensity aerobics, digging in the garden or lifting heavy objects).

Moderate: It causes your heart rate to increase slightly and you typically work up a sweat (eg, leisurely sports like light tennis, slow or light swimming, low intensity aerobics or golfing without a power cart, brisk walking, mowing the lawn with a walking lawnmower).

Light: It requires little physical effort (eg, light housekeeping like dusting or laundry, bowling, archery, easy walking, golfing with a power cart or fishing).

Keeping these definitions in mind, participants were asked if they engaged in regular physical activity of any type for 20 min or more at least three times per week (yes or no). If participants answered “yes”, they entered up to seven types of seasonal and/or non-seasonal exercise or activity along with the frequency, duration and intensity.

MMW were calculated in a two-step process. Step 1: participants who reported no physical activity (for whom no MMW calculations could be made) were designated as the no regular exercise group (NRE). Step 2: for participants who indicated that they performed regular physical activity, total MMW were calculated by multiplying minutes per week by intensity level (1.1 for low, 3.0 for moderate and 6.0 for vigorous) and summed across each non-seasonal activity reported. Four groups reflecting participation in physical activity and whether or not their participation was below, at or above United States Department of Health and Human Services (USDHHS) guidelines were created: NRE (reported no regular physical activity), below recommended (reported <500 MMW), recommended (reported 500–1000 MMW) and above recommended (reported >1000 MMW).

Blood collection, processing and assays

Participants were asked to avoid strenuous activity on the day of blood collection. Venous blood samples were collected in 10 ml serum separator vacutainers following a 12-h overnight fast and processed at a General Clinical Research Center using standardised procedures. Blood samples were not collected at any specific point during the menstrual cycle in female participants. Briefly, following collection, vacutainers were allowed to stand 15–30-min (2-h maximum) prior to centrifugation at 4°C for 20-min at 2000–3000 rpm. Serum samples were frozen and shipped to the MIDUS Biocore Lab and treated and/or analysed for inflammation markers (IL-6, IL-6sr, CRP, fibrinogen, sE-selectin and sICAM-1).

IL-6 and IL-6sr were assayed in the MIDUS Biocore Laboratory (University of Madison, Madison WI) using Quantikine High-sensitivity ELISA kits (cat# HS600B and cat# DR600, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Plates were read at 490 and 450 nm, respectively, for IL-6 and IL-6sr using a Dynex MRXe plate reader (Magellan Biosciences, Chantilly, Virginia, USA). Intra-assay and interassay precision (CV%) for IL-6 was approximately 4.1% and 13%, respectively. CV% values for IL-6sr were 5.9–5.7% and 2.0%, respectively.

Assays for sICAM-1, sE-selectin, fibrinogen and CRP were performed at the Laboratory for Clinical Biochemistry Research (University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont, USA). Measurement of sICAM-1 was completed using an ELISA assay (Parameter-Human sICAM-1 Immunoassay; R&D Systems). Inter-assay precision for sICAM-1 was 5.0%. Measurement of sE-selectin was completed using a high-sensitivity ELISA assay (Parameter Human sE-Selectin Immunoassay, R&D Systems). Intra-assay and inter-assay precision for sE-selectin was 4.7–5.0% and 5.7–8.8%, respectively. Fibrinogen was measured using the BNII nephelometer (N Antiserum to Human Fibrinogen; Dade Behring Inc, Deerfield, Illinois, USA). Intra-assay and inter-assay precision for fibrinogen was 2.7% and 2.6%, respectively. CRP was analysed using a BNII nephelometer with a particle enhanced immunonepolometric assay. Intra-assay and inter-assay precision for CRP was 2.3–4.4% and 2.1–5.7%, respectively.

Statistical analyses

All variables were assessed for normality and non-normal data were log transformed, which included data for CRP, IL-6, IL-6sr, fibrinogen, sE-selectin and sICAM-1. General linear models were performed to determine the relationship of MMW and BMI with the inflammatory markers. For each outcome, the ordinal MMW and BMI factors were entered as independent factors with an interaction term. If the interaction term was not significant, the interaction term was dropped and the model was refit for main effects only. Pairwise comparisons were assessed using post hoc univariate analyses with a Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. Covariates for all models included factors that are known to affect inflammatory status—age, sex, smoking and relevant medications (cholesterol-lowering, corticosteroids, antidiabetics, antidepressants, hormone replacements and hormonal contraceptives). Race was initially included as a covariate; however, approximately 200 data points were lost in the analyses owing to incomplete racial data. As race was not found to be a predictor of our dependent variables, with the exception of sICAM-1, race was excluded as a covariate to increase sample size in all analyses excluding sICAM-1. All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS V.17 (Chicago, Illinois, USA) and statistical significance was set α=0.05.

In an exploratory analysis, we examined whether the relative effects of BMI and MMW on the inflammatory markers differed by sex in three-way interaction models. As none of the interactions approached statistical significance (data not shown), sex was retained as a covariate in the models.

Results

Participant characteristics

Table 1 presents the anthropometric characteristics and circulating levels of inflammatory biomarkers in all participants (n=1254). Participants were 92.6% non-Hispanic white, 56.8% female and, on average, middle-aged and overweight. Of all the respondents, 14.9% were currently smokers, 27.8% were taking cholesterol-lowering medications, 12.1% corticosteroids, 10.4% antidiabetic medications, 14.2% antidepressant medications, 7.3% hormone replacements and 2.5% oral contraceptives. The percentages of participants with missing data for each variable were as follows: 1.6% for CRP, 1.0% for sICAM-1, 1.0% for IL-6, 1.6% for fibrinogen, 1.2% for sE-selectin, and 1.0% for IL-6sr.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Demographic | BMI <25 n=298 | BMI 25–29.9 n=440 | BMI ≥30 n=516 | Overall n=1254 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean±SD |

|||

| Age (years) | 54.6±12.8 | 56.4±11.7 | 54.6±11.2 | 54.5±11.7 |

| Gender (%) | ||||

| Male | 31.2 | 52.7 | 42.1 | 43.20 |

| Female | 68.8 | 47.3 | 57.9 | 56.80 |

| Race (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 94.0 | 94.0 | 90.3 | 92.60 |

| Hispanic | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.05 |

| African American | 1.9 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 2.60 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.30 |

| Native American | 1.1 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 1.30 |

| Other | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.5 | 2.30 |

| Medication use (%) | ||||

| Cholesterol-lowering | 13.1 | 32.3 | 32.6 | 27.80 |

| Corticosteroids | 12.8 | 12.5 | 11.4 | 12.10 |

| Antidiabetics | 4.7 | 8.4 | 15.3 | 10.40 |

| Antidepressants | 14.4 | 13.4 | 16.9 | 14.2 |

| Hormone replacement therapy | 9.4 | 8.6 | 5.0 | 7.3 |

| Oral contraceptives | 3.7 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 2.5 |

| Currently smoking | 17.8 | 14.1 | 14.0 | 14.90 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.7±1.8 | 27.4±1.4 | 35.9±5.7 | 29.8±6.6 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 2.4±3.1 | 2.7±2.48 | 3.7±3.2 | 3.0±3.1 |

| IL-6sr (pg/ml) | 34473.1±10861.9 | 35337.4±10065.1 | 35475.7±10325.7 | 35184.7±10359.1 |

| CRP (μg/ml) | 1.5±2.5 | 2.5±4.0 | 4.4±5.9 | 3.0±4.8 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dl) | 315.8±75.9 | 343.2±82.1 | 373±92.1 | 348.9±87.9 |

| sE-Selectin (ng/ml) | 36.9±19.6 | 41.2±20.6 | 49.1±24.7 | 43.4±22.7 |

| sICAM-1 (ng/ml) | 284.8±122.0 | 276.2±99.9 | 301.4±123.1 | 288.6±115.6 |

BMI, body mass index; IL, interleukin; IL-6sr, IL-6 soluble receptor; MMW, MET-minutes per week; sE-selectin, soluble E-selectin; sICAM-1, soluble intracellular adhesion molecule-1.

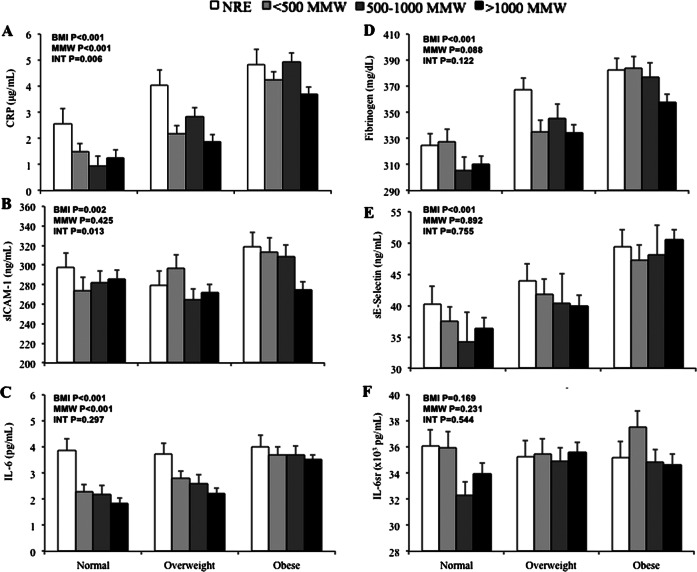

C reactive protein

We found a significant interaction between BMI and MMW for CRP concentration (F=3.022, p=0.006; figure 1A). In post hoc comparisons, CRP levels were higher in overweight and obese participants compared to normal weight participants among those who reported no regular exercise (p<0.001). However, among participants who reported any amount of regular exercise (<500, 500–1000 or >1000 MMW), CRP levels were significantly greater only in obese participants compared to both normal weight and overweight participants (p<0.01). In obese individuals, CRP tended to be lower in those reporting >1000 MMW compared to those reporting no regular exercise (p=0.053).

Figure 1.

Inflammatory markers. Data from 1254 men and women in MIDUS. Joint association of BMI category (normal, overweight and obese) and MMW category (no regular exercise, <500 MMW, 500–1000 MMW and >1000 MMW) for C reactive protein (A), sICAM-1 (B), IL-6 (C), fibrinogen (D), sE-selectin (E) and IL-6sr (F). These analyses were adjusted for age, sex, smoking and relevant medication use. The analysis for sICAM-1 was further adjusted for race. Error bars represent SEM. BMI=BMI main effect p value, MMW=MMW main effect p value, INT=interaction effect p value.

We also found main effects of BMI (F=130.873 p<0.001) and MMW (F=11.576, p<0.001) on CRP. CRP was significantly greater with each increasing BMI category, in a dose-dependent manner (p<0.001). Compared to participants who reported no regular exercise, CRP was significantly lower in those who reported 500–1000 and >1000 MMW (p<0.01), with a trend for lower CRP in those who reported <500 MMW of regular exercise (p=0.078).

sICAM-1

We found a significant interaction between BMI and MMW for sICAM-1 concentration (F=2.701, p=0.013) (figure 1B). Levels of sICAM-1 were significantly lower in obese participants who reported >1000 MMW compared to obese participants who reported no regular exercise (p=0.014) and <500 MMW (p=0.026) and tended to be lower than levels in obese participants who reported 500–1000 MMW (p=0.079). No differences in sICAM-1 by MMW were observed among normal weight or overweight individuals.

We also observed a main effect of BMI (F=6.060, p=0.002), such that sICAM-1 levels in obese participants were significantly higher than levels found in both normal weight and overweight participants (p<0.01). No significant main effect of MMW was found for sICAM-1 (F=0.931, p=0.425).

Interleukin L-6

Both BMI and MMW had independent effects on circulating concentrations of IL-6 (BMI F=60.150, p<0.001, MMW: F=10.680, p<0.001), with no significant interaction (F=1.21, p=0.297) (figure 1C). We found a dose-dependent effect of BMI, such that higher BMI levels were associated with significantly greater IL-6 (p<0.001). Independent of BMI, IL-6 was significantly lower in participants who reported regular exercise (<500 MMW, 500–1000 MMW and >1000 MMW) compared to those who reported no regular exercise (p<0.01) with no difference between levels of MMW.

Fibrinogen

BMI contributed significantly to circulating levels of fibrinogen (F=42.385, p<0.001), such that dose-dependent increases were observed for all BMI levels (p<0.01) (figure 1D). While we observed a trend for lower fibrinogen with regular physical activity, similar to that of IL-6, the effect did not reach statistical significance (F=2.187, p=0.088). We observed no significant interaction between BMI and MMW for fibrinogen (F=1.680, p=0.122).

sE-Selectin

BMI contributed significantly to circulating levels of sE-selectin (F=28.253, p<0.001), with no significant contribution by MMW (F=0.207, p=0.892; figure 1E). Dose-dependent increases in sE-selectin were also observed across BMI levels (p<0.01). We observed no significant interaction between BMI and MMW for sE-selectin (F=0.570, p=0.755).

IL-6sr

No significant main effects for BMI (F=1.783, p=0.169), MMW (F=1.434, p=0.231) or their interaction (F=0.834, p=0.544) were detected for IL-6sr (figure 1F).

Waist circumference and inflammatory markers

A secondary analysis was completed using waist circumference (WC) and MMW as independent variables and the complete results of these analyses are located in the supplemental information (see online supplementary figure S1). Briefly, we found a significant interaction between WC and MMW on sICAM-1. In individuals with an at-risk WC (≥102.0 cm for men and ≥88.0 cm for women), sICAM-1 was significantly lower in those reporting 1000+ MMW compared to less than 500 MMW and tended to be lower in those reporting no regular exercise. Overall, the main effects were similar to those found for BMI and MMW analyses. Having an at-risk WC was independently related to higher levels of CRP, sICAM-1, IL-6, fibrinogen and sE-selectin. Independent of WC, any level of regular exercise was related to lower levels of CRP, IL-6 with a similar tendency for fibrinogen.

Discussion

The current study aimed to determine whether the impact of BMI and MMW on inflammatory markers varied by level of overweight or obesity. For CRP and s-ICAM-1, regular physical activity appeared to diminish the effects of higher BMI compared to those who reported no regular physical activity. In addition, we found that BMI was strongly and independently related to greater concentrations of both established and emerging inflammatory markers that may increase CVD risk. Independent of BMI, regular physical activity was also associated with lower IL-6, with a similar trend for fibrinogen. These results suggest that although obesity has a clear impact on inflammation, physical activity appears to mitigate at least some of this effect.

For example, overweight individuals had CRP levels which were similar to levels observed in obese individuals if they reported no regular exercise (4.05 and 4.83 μg/ml, respectively). CRP levels greater than 3 μg/ml are typically associated with high CVD risk.26 In overweight participants who reported regular physical activity of at least three 20-min sessions per week (be it below (<500), within (500–1000) or above (>1000) USDHHS MMW recommendations), CRP levels were lower and not significantly different from CRP levels found in normal weight participants. This suggests that increasing physical activity level to a minimum of 3 days/week, at least 20 min/day, may improve CRP profiles among overweight individuals.

Obese individuals may require a higher level of regular physical activity in order to lower inflammatory markers. While obese participants also had greater levels of CRP and sICAM-1 compared to lean and overweight participants, those who reported >1000 MMW (above the USDHHS recommendation) had lower levels of sICAM-1 and tended to have lower CRP than obese participants reporting no regular physical activity. Taken together, we may speculate that while physical activity levels currently recommended for the general population may reduce particular inflammatory makers in overweight populations, obese populations may require greater levels of physical activity above the recommended values to reduce inflammatory markers like CRP and sICAM-1.

As expected, strong main effects of BMI were observed for CRP, IL-6, fibrinogen, sICAM-1 and sE-selectin, in agreement with previous work.27–30 Independent of BMI effects, our results suggest that physical activity has differentiating effects on inflammatory markers. Individuals reporting no regular physical activity had higher levels of IL-6 with a tendency for higher fibrinogen, compared to those reporting any level of regular physical activity (<500, 500–1000 or >1000 MMW). Similar results have been observed in the MONItoring trends and determinants in the CArdiovascular disease (MONICA) study,31 the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III)12 14 and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA),32 such that both the increased frequency and intensity of physical activity have been related to lower IL-6 and fibrinogen. Our findings add to these prior results by standardising levels of physical activity by using USDHHS. Our results suggest that regular physical activity at any level (<500, 500–1000, >1000) appears to be associated with lower levels of IL-6 and possibly fibrinogen, independent of BMI.

Although IL-6 produced in hypertrophied adipose tissue33 34 initiates the acute phase response, marked by the release of hepatic CRP,35 36 an interaction between BMI and physical activity was detected for CRP, but not IL-6. While IL-6 and CRP were significantly correlated (r=0.514, see online supplementary table S1), this correlation suggests that IL-6 levels do not fully explain CRP levels at any given moment. Further, CRP is a more stable biomarker, owing to its substantially longer plasma half-life,37 which may improve our ability to detect interaction effects in CRP compared to IL-6.

Interestingly, our results also suggest that regular exercise may have a more profound impact on lowering classical markers of inflammation and less impact on the inflammatory status of the endothelium. Regular physical activity has reliably been associated with lower levels of IL-6 and CRP, both classical inflammatory markers related to adipose and systemic inflammation.38 However, regular exercise appeared to have no independent impact on markers of endothelial activation, particularly sE-selectin. Higher levels of exercise were related to lower sICAM-1 in obese individuals only. In one prior study, inverse relationships between physical activity and sICAM-1 and sE-selectin were reported in drug-treated hypertensive men.39 Thus, further research is necessary to understand mechanisms underlying differential associations of exercise with systemic and endothelial inflammation.

Several limitations must be addressed. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow us to infer causal relationships. Prospective and interventional designs are necessary to confirm our findings. No objective measures of physical activity were available in the MIDUS sample. Therefore, the use of self-report physical activity data may have diminished our ability to detect effects. However, in addition to being in line with previous studies using self-report physical activity, our findings are also in line with previous studies40 41 that demonstrated that higher cardiorespiratory fitness, as measured by indirect calorimetry, was associated with lower levels of inflammation independent of visceral adiposity or BMI. Another limitation is that the sample was predominantly comprised of non-Hispanic white individuals, suggesting that the findings may not extend to all ethnicities. Finally, BMI and physical activity variables are correlated, potentially raising the concern of small sample sizes in specific groups crossed by BMI and MMW. However, the smallest group for analyses still contained 54 individuals (normal weight individuals reporting no exercise).

In summary, our results demonstrate both the interactive and independent influences of BMI and levels of physical activity on both established and emerging markers of inflammation. Inflammation is both a consequence of obesity and a mechanism promoting CVD. Regular physical activity appears to mitigate the effects of higher BMI on some inflammatory markers, particularly CRP, which is strongly implicated in CVD. Importantly, while any level of regular physical activity may help reduce inflammation in overweight individuals, similar effects in obese individuals may require levels of physical activity that are greater than currently recommended by the USDHHS for general health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Clinical Research Centers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, UCLA and Georgetown University for their effort in conducting the original data collection.

Footnotes

Contributors: KS, JMMC and RRW made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, data acquisition, analysis and interpretation, as well as to the drafting and revision for substantial intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: KS was supported through a T32 Training Fellowship (Training in Behavioral and Preventive Medicine; T32 HL076134). The original research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Aging (P01-AG020166) to conduct a longitudinal follow-up of the MIDUS (Midlife in the US) Investigation. The original study was supported by the John D and Catherine T MacArther Foundation Research Network on Successful Midlife Development and by the following grants: M01-RR023942 (Georgetown), M01-RR00865 (UCLA) from the General Clinical Research Centers programme and 1UL1RR025011 (UW) from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) programme of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data and documentation for the MIDUS studies are available at the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR). http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/landing.jsp

References

- 1.Blair SN, Brodney S. Effects of physical inactivity and obesity on morbidity and mortality: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1999;31(11 Suppl):S646–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and metabolic disorders. Nature 2006;444:860–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koenig W, Khuseyinova N, Baumert J, et al. Increased concentrations of C-reactive protein and IL-6 but not IL-18 are independently associated with incident coronary events in middle-aged men and women: results from the MONICA/KORA Augsburg case-cohort study, 1984–2002. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26:2745–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papageorgiou N, Tousoulis D, Siasos G, et al. Is fibrinogen a marker of inflammation in coronary artery disease? Hellenic J Cardiol 2010;51:1–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt C, Hulthe J, Fagerberg B. Baseline ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 are increased in initially healthy middle-aged men who develop cardiovascular disease during 6.6 years of follow-up. Angiology 2009;60:108–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demerath E, Towne B, Blangero J, et al. The relationship of soluble ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P-selectin and E-selectin to cardiovascular disease risk factors in healthy men and women. Ann Hum Biol 2001;28:664–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009;6:399–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calabro P, Yeh ET. Obesity, inflammation, and vascular disease: the role of the adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. Subcell Biochem 2007;42:63–91 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pou KM, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, et al. Visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue volumes are cross-sectionally related to markers of inflammation and oxidative stress: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2007;116:1234–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathieu P, Poirier P, Pibarot P, et al. Visceral obesity: the link among inflammation, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Hypertension 2009;53:577–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reuben DB, Judd-Hamilton L, Harris TB, et al. The associations between physical activity and inflammatory markers in high-functioning older persons—MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1125–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King DE, Carek P, Mainous AG, III, et al. Inflammatory markers and exercise: differences related to exercise type. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:575–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wannamethee SG, Lowe GD, Whincup PH, et al. Physical activity and hemostatic and inflammatory variables in elderly men. Circulation 2002;105:1785–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abramson JL, Vaccarino V. Relationship between physical activity and inflammation among apparently healthy middle-aged and older US adults. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:1286–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geffken DF, Cushman M, Burke GL, et al. Association between physical activity and markers of inflammation in a healthy elderly population. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:242–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taaffe DR, Harris TB, Ferrucci L, et al. Cross-sectional and prospective relationships of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein with physical performance in elderly persons: MacArthur studies of successful aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2000;55:M709–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Starkie R, Ostrowski SR, Jauffred S, et al. Exercise and IL-6 infusion inhibit endotoxin-induced TNF-alpha production in humans. FASEB J 2003;17:884–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen BK, Steensberg A, Fischer C, et al. Exercise and cytokines with particular focus on muscle-derived IL-6. Exerc Immunol Rev 2001;7:18–31 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen BK, Steensberg A, Fischer C, et al. The metabolic role of IL-6 produced during exercise: is IL-6 an exercise factor? Proc Nutr Soc 2004;63:263–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Adipokines: inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br J Nutr 2004;92:347–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beavers KM, Brinkley TE, Nicklas BJ. Effect of exercise training on chronic inflammation. Clin Chim Acta 2010;411:785–93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.USDHHS, ed. 2008 Physical activity guidelines for Americans. Washington DC, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryff C, Almeida DM, Ayanian JS, et al. 2011 National Survey of Midlife Development in the United State (MIDUS II), 2004–2006. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraemer H. How many participants? Statistical power analysis in research. SAGE Publications, Inc, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edn Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassuk SS, Rifai N, Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: clinical importance. Curr Probl Cardiol 2004;29:439–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of CRP, TNF-alpha and IL-6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2005;69:29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bastard JP, Jardel C, Bruckert E, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3338–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ditschuneit HH, Flechtner-Mors M, Adler G. Fibrinogen in obesity before and after weight reduction. Obes Res 1995;3:43–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straczkowski M, Lewczuk P, Dzienis-Straczkowska S, et al. Elevated soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 levels in obesity: relationship to insulin resistance and tumor necrosis factor-alpha system activity. Metabolism 2002;51:75–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Autenrieth C, Schneider A, Doring A, et al. Association between different domains of physical activity and markers of inflammation. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:1706–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Majka DS, Chang RW, Vu TH, et al. Physical activity and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:56–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Day CP. From fat to inflammation. Gastroenterology 2006;130:207–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fain JN, Madan AK, Hiler ML, et al. Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology 2004;145:2273–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castell JV, Gomez-Lechon MJ, David M, et al. Interleukin-6 is the major regulator of acute phase protein synthesis in adult human hepatocytes. FEBS Lett 1989;242:237–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heinrich PC, Castell JV, Andus T. Interleukin-6 and the acute phase response. Biochem J 1990;265:621–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pradhan AD, Manson JE, Rifai N, et al. C-reactive protein, interleukin 6, and risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2001;286:327–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathieu P, Lemieux I, Despres JP. Obesity, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2010;87:407–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hjelstuen A, Anderssen SA, Holme I, et al. Markers of inflammation are inversely related to physical activity and fitness in sedentary men with treated hypertension. Am J Hypertens 2006;19:669–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Church TS, Barlow CE, Earnest CP, et al. Associations between cardiorespiratory fitness and C-reactive protein in men. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:1869–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arsenault BJ, Cartier A, Cote M, et al. Body composition, cardiorespiratory fitness, and low-grade inflammation in middle-aged men and women. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:240–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.