Abstract

A decline in α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHC) activity has been associated with neurodegeneration. Provision of succinyl-CoA by KGDHC is essential for generation of matrix ATP (or GTP) by substrate-level phosphorylation catalyzed by succinyl-CoA ligase. Here, we demonstrate ATP consumption in respiration-impaired isolated and in situ neuronal somal mitochondria from transgenic mice with a deficiency of either dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (DLST) or dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (DLD) that exhibit a 20–48% decrease in KGDHC activity. Import of ATP into the mitochondrial matrix of transgenic mice was attributed to a shift in the reversal potential of the adenine nucleotide translocase toward more negative values due to diminished matrix substrate-level phosphorylation, which causes the translocase to reverse prematurely. Immunoreactivity of all three subunits of succinyl-CoA ligase and maximal enzymatic activity were unaffected in transgenic mice as compared to wild-type littermates. Therefore, decreased matrix substrate-level phosphorylation was due to diminished provision of succinyl-CoA. These results were corroborated further by the finding that mitochondria from wild-type mice respiring on substrates supporting substrate-level phosphorylation exhibited ∼30% higher ADP-ATP exchange rates compared to those obtained from DLST+/− or DLD+/− littermates. We propose that KGDHC-associated pathologies are a consequence of the inability of respiration-impaired mitochondria to rely on “in-house” mitochondrial ATP reserves.—Kiss, G., Konrad, C., Doczi, J., Starkov, A. A., Kawamata, H., Manfredi, G., Zhang, S. F., Gibson, G. E., Beal, M. F., Adam-Vizi, V., Chinopoulos, C. The negative impact of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex deficiency on matrix substrate-level phosphorylation.

Keywords: succinyl-CoA ligase, adenine nucleotide translocase, F0–F1 ATP synthase, reversal potential

The α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (KGDHC) is an enzyme consisting of multiple copies of three subunits: α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase (KGDH or E1k, EC 1.2.4.2), dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase (E2k or DLST, EC 2.3.1.61), and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (DLD or E3, EC 1.8.1.4). It participates in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, where it irreversibly catalyzes the conversion of α-ketoglutarate, CoASH, and NAD+ to succinyl-CoA, NADH, and CO2. It may exhibit a high flux-control coefficient in the generation of reducing equivalents (1) and is also crucial for maintenance of the mitochondrial redox state (2). In addition, KGDHC is involved in transaminations, glutamate metabolism (3). Furthermore, it provides succinyl-CoA for heme synthesis, a pathway commencing in mitochondria (4, 5), and mitochondrial substrate-level phosphorylation. Substrate-level phosphorylation in mitochondria is almost exclusively attributed to succinyl-CoA ligase (SUCL), an enzyme of the TCA cycle catalyzing the reversible conversion of succinyl-CoA and ADP (or GDP) to CoASH, succinate, and ATP (or GTP) (6). Finally, the DLST gene also encodes a truncated mRNA for another protein, designated as mitochondrial respiration generator of truncated DLST (MIRTD), that is localized in mitochondria, where it regulates the biogenesis of the respiratory chain (7).

A decline in KGDHC activity has been associated with a number of neurodegenerative diseases; however, activity decline is not universal for all TCA cycle enzymes (8–10). In search of an association between a decrease in KGDHC activity and incidence of neurodegeneration, two transgenic mouse strains have been generated, one lacking the DLST subunit (11), and the other lacking the DLD subunit (12). Disruption of both alleles of either gene results in perigastrulation lethality; heterozygote mice exhibit no apparent behavioral phenotypes. A deficiency in the DLD or DLST subunit has been shown to cause increased vulnerability to mitochondrial toxins modeling neurodegenerative diseases (11, 13, 14), and to result in reduced numbers of neural progenitor cells in the hippocampi of adult mice (15). In transgenic mice carrying human mutations prompting them to develop amyloid deposits, DLST deficiency aggravates amyloid plaque burden (16). In addition, increased levels of the lipid peroxidation marker, malondialdehyde, was found in DLD+/− (13) but not DLST+/− mice (15). KGDHC is known to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), and DLD+/− mice exhibited diminished rates of ROS production (17, 18).

Although the above findings establish a link between KGDHC deficiency and brain pathology, they stop short in identifying the molecular mechanisms underlying the propensity for neurodegeneration. So far, the focus of this association has been biased toward diminished provision of reducing equivalents and excess production of ROS. In this study, we demonstrate that in KGDHC-deficient mice, the decreased provision of succinyl-CoA diminishes matrix substrate-level phosphorylation, resulting in impaired mitochondrial ATP output and consumption of cytosolic ATP by respiration-impaired mitochondria, in line with the predictions reported recently (19).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Heterozygous DLD-knockout (DLD+/−; C57BL/6) mice have been developed and characterized (12). DLD+/− and wild type (WT) littermates were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (JAX mice; Jackson Laboratory Repository, Bar Harbor, ME, USA), deposited by Dr. Mulchand S. Patel (State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY, USA. Mice deficient in the DLST subunit (DLST+/−; C57BL/6 and 129SV/EV hybrid) and WT littermates were obtained from Lexicon Pharmaceuticals (The Woodlands, TX, USA). DLD+/− and DLST+/− mice have no apparent behavioral phenotype. WT mice were reproduced by crossing DLD+/− and DLST+/−; thus, all WT mice have DLD+/− or DLST+/− progeny. Double-transgenic DLD+/− DLST+/− mice were produced by cross-breeding DLD+/− and DLST+/− mice, and they also exhibited no apparent behavioral phenotype. The animals used in our study were of either sex and between 2 and 3 mo of age. Mice were housed in a room maintained at 20–22°C on a 12-h light-dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were approved by the Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Semmelweis University (Egyetemi Állatkísérleti Bizottság).

Isolation of mitochondria from mouse liver and brain

Nonsynaptic brain mitochondria from adult male and female mice were isolated on a Percoll gradient as described previously (20), with minor modifications detailed previously (21). Liver mitochondria were isolated as described previously (22). Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay, and calibrated using bovine serum standards (23) using a Tecan Infinite 200 PRO series plate reader (Tecan Deutschland GmbH, Crailsheim, Germany). Yields were typically 0.2 ml of ∼15 mg/ml per 2 brains; for liver, yields were typically 0.4 ml of ∼80 mg/ml per liver.

Isolation of synaptosomes from mouse brain

Synaptosomes were prepared from adult male and female mice by Percoll gradient purification as detailed previously (24). Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (23) and calibrated using bovine serum standards (23); yields were typically 0.2 ml of ∼20 mg/ml per 2 brains.

Neuronal cultures

Mixed primary cultures of cortical neurons and astrocytes (∼20% of total cell count were astrocytes) were prepared from mouse pups (P0–P1), as detailed elsewhere (25). Cultures were prepared from each pup individually; subsequent genotyping of the pups identified whether the culture was from a WT or a transgenic mouse. Cells were grown on poly-l-ornithine-coated 8-well Lab-Tek II chambered coverglasses (Nunc, Rochester, NY, USA) for 7–12 d, at a density of 105 cells/well in Neurobasal medium containing 2% B27 supplement and 2 mM glutamine.

Determination of membrane potential in isolated liver, brain, in situ synaptic and in situ neuronal somal mitochondria

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) of isolated mitochondria (0.25 mg for brain, 1 mg for liver) was estimated fluorimetrically with safranine O (26) and calibrated to millivolts exactly as described in ref. 19. ΔΨm of in situ mitochondria of synaptosomes was qualitatively estimated fluorimetrically by loading synaptosomes with 100 nM of the potentiometric fluorescent dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM). Synaptosomes (0.5 mg) were added to 2 ml of incubation medium containing 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM PIPES (Na+), and 15 mM glucose, pH 7.4. Fluorescence was recorded in a Hitachi F-4500 or F-7000 spectrofluorimeter (Hitachi High Technologies, Maidenhead, UK) at a 5-Hz acquisition rate, using 546- and 573-nm excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. ΔΨm of in situ mitochondria of neurons was qualitatively determined by wide-field fluorescence imaging, or confocal imaging. Briefly, the TMRM fluorescence (7.5 nM) was followed in time over cell bodies (see below). Experiments were performed in a medium containing 120 mM NaCl, 3.5 mM KCl, 1.3 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM HEPES (acid), 15 mM glucose, and 1 μM tetraphenylboron, pH 7.4. To prevent excitotoxicity, all experiments were performed in the presence of 1 μM tetrodotoxin, 10 μM MK801, 10 μM 2,3-dihydroxy-6-nitro-7-sulfamoylbenzo(f)quinoxaline, and 1 μM nifedipine (19). All ΔΨm determinations of isolated, in situ synaptic and in situ neuronal somal mitochondria were performed at 37°C.

Fluorescence imaging

Imaging was performed either with confocal imaging (on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal system; Leica Microsystems Inc, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA) or epifluorescent imaging. During the confocal imaging, full frames (using a Leica HC PL Fluotar ×10 air 0.3NA lens) were taken at 3-min intervals; 9–18 view fields in 3–6 wells of the Lab-Tek chamber were recorded cyclically using the inbuilt acquisition feature of the Leica Microsystems software. Epifluorescence imaging was performed on an Olympus IX-81 inverted microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a UAPO ×20 air 0.75NA lens, a Lambda LS Xe-arc light source (175 W), Lambda 10-2 excitation and emission filter wheels (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA), a Bioprecision-2 linear encoded xy stage (Ludl Electronic Products Ltd., Hawthorne, NY), and an ORCA-ER2 cooled digital charge-coupled device camera (−60°C, 10-MHz readout, low gain, 12-bit depth; Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). Full frames at 4 × 4 binning (1.3 μm/pixel resolution) were taken at 3-min intervals. Eight to 16 view fields in 4–8 wells of the Lab-Tek chamber were recorded cyclically using the Multi Dimensional Acquisition feature of Metamorph 6.3 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The filter sets, given as excitation-dichroic mirror-emission (nm) for TMRM were 535/20-555LP-590/20 (all from Chroma, Rockingham, VT, USA).

Free Mg2+ concentration [Mg2+]f determination from magnesium green fluorescence in the extramitochondrial volume of isolated mitochondria and conversion to ADP-ATP exchange rate

ADP-ATP exchange rate was estimated using the recently described fluorimetric method by our laboratory (27), exploiting the differential affinity of ADP and ATP to Mg2+. The rate of ATP appearing in the medium following addition of ADP to energized mitochondria (0.25 mg for brain, 1 mg for liver), is calculated from the measured rate of change in free extramitochondrial [Mg2+] using standard binding equations. The assay is designed such that the adenine nucleotide translocase (ANT) is the sole mediator of changes in [Mg2+]f in the extramitochondrial volume, as a result of ADP-ATP exchange. For the calculation of [ATP] or [ADP] from [Mg2+]f, the apparent Kd values are identical to those reported previously (27) due to identical experimental conditions (KADP=0.906±0.023 mM; KATP=0.114±0.005 mM).

Determination of SUCL activity in isolated mitochondria

ATP- and GTP-forming SUCL activity in isolated mitochondria was determined at 30°C, as described previously (28), with modifications detailed in ref. 29. Mitochondria (0.25 mg from brain and 1 mg from liver) were added in an assay mixture (2 ml) containing 20 mM potassium phosphate, 0.4% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate (CHAPS; pH 7.2), 10 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM ADP or GDP. The reactions were initiated by adding 0.2 mM succinyl-CoA and 0.2 mM 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) in quick succession. The molar extinction coefficient value at 412 nm for the 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate anion formed on reaction of DTNB with CoASH was considered as 13,600 M−1 · cm−1. Rates of 2-nitro-5-thiobenzoate formation were followed spectrophotometrically during constant stirring by subtracting the rate observed when ADP or GDP was omitted.

Mitochondrial respiration

Oxygen consumption was performed polarographically using an Oxygraph-2k (Oroboros Instruments, Innsbruck, Austria). Brain and liver mitochondria (0.125 and 1 mg, respectively) were suspended in 2 ml incubation medium or 1 mg of liver mitochondria in 4 ml incubation medium, the composition of which was identical to that for [Mg2+]f determination. Experiments were performed at 37°C. Oxygen concentration and oxygen flux (pmol·s−1·mg−1; negative time derivative of oxygen concentration, divided by mitochondrial mass per volume) were recorded using DatLab software (Oroboros Instruments).

Determination of KGDHC activity

KGDHC activity in mouse liver and brain isolated mitochondria and isolated nerve terminals was measured fluorimetrically, as detailed previously (17), with minor modifications. The reaction medium was composed of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.8), 0.3 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 50 μM CaCl2, 0.2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM α-ketoglutarate, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 0.5 mM NAD+. The reaction was started by adding 0.12 mM CoASH to freeze-thawed mitochondria (0.1 mg/ml) or synaptosomes (0.5 mg/ml). Reduction of NAD+ was followed at 435-nm emission after excitation at 340 nm. The extinction coefficient (ε340) of NADH fluorescence was considered as 6220 M−1 · cm−1.

Western blotting

Frozen mitochondrial and synaptosomal pellets were thawed on ice and separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Separated proteins were transferred to a methanol-activated polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Immunoblotting was performed as recommended by the manufacturers of the antibodies. Mouse monoclonal anti-cyclophilin D (cypD; Mitosciences, Eugene, OR, USA), rabbit polyclonals anti-SUCLG1 and anti-SUCLG2 (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and anti-SUCLA2 (Proteintech Europe Ltd., Manchester, UK) primary antibodies were used at concentrations of 1 μg/ml, and rabbit polyclonal anti-manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD; Abcam) at 0.2 μg/ml. Immunoreactivity was detected using the appropriate peroxidase-linked secondary antibody (1:4000, donkey anti-mouse or donkey anti-rabbit; Jackson Immunochemicals Europe Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK) and enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (ECL system; Amersham Biosciences GE Healthcare Europe GmbH, Vienna, Austria).

Estimation of reversal potential of ANT (Erev_ANT) and F0–F1 ATPase (Erev_ATPase)

Computational estimations of Erev_ANT and Erev_ATPase were performed using Erev estimator (available at http://www.oxphos.org/index.php?option=com_remository&Itemid=40&func=fileinfo&id=74).

Statistics

Data are presented as means ± sem. Significant differences between 2 groups were evaluated by Student's t test; significant differences between ≥3 groups were evaluated by one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. If normality test failed, ANOVA on ranks was performed. Wherever single graphs are presented, they are representative of ≥3 independent experiments.

Reagents

Standard laboratory chemicals, safranine O, and valinomycin were from Sigma. Magnesium green and TMRM were from Invitrogen (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). 3,5-Di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidenemalononitrile (SF 6847) was from Biomol GmbH (Hamburg, Germany). Carboxyatractyloside (cATR) and bongkrekic acid (BKA) were from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Neurobasal medium and B27 supplement were from Invitrogen. Mitochondrial substrate stock solutions were dissolved in bidistilled water and titrated to pH 7.0 with KOH. ADP and ATP were purchased as K+ salts of the highest purity available (Merck) and titrated to pH 6.9.

RESULTS

Thermodynamic considerations on the directionalities of F0–F1 ATP synthase and ANT in respiration-impaired mitochondria from WT and transgenic animals with deficiencies in KGDHC

Mitochondria are able to synthesize and hydrolyze ATP (30–34). ATP for hydrolysis could derive either from matrix pools or from the extramitochondrial compartment. Hydrolysis of ATP in the matrix occurs primarily by a reverse-operating F0–F1 ATP synthase; import of extramitochondrial ATP into the matrix may occur by a reverse-operating ANT. The directionalities of the F0–F1 ATP synthase and that of ANT depend on several parameters (19, 35–37). It cannot be overemphasized that the statements appearing below concern only the directionality of the F0–F1 ATP synthase and ANT, and not their magnitudes of operation. The value of ΔΨm at which the F0–F1 ATP synthase shifts from ATP-forming to ATP-consuming is termed reversal potential, Erev_ATPase (36). Erev_ATPase is given by Eqs. 1 and 2:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where n is the H+/ATP coupling ratio (38); KM(ADP) and KM(ATP) are the true affinity constants of Mg2+ for ADP and ATP, valued 10−3.198 and 10−4.06, respectively (39); “in” and “out” signify inside and outside the mitochondrial matrix, respectively; R is the universal gas constant, 8.31 J · mol−1 · K−1; F is the Faraday constant, 9.64 × 104 C · mol−1; T is temperature (in Kelvin); and [P−] is the free phosphate concentration (in molar) given by Eq. 2, where pKa2 = 7.2 for phosphoric acid. By the same token, the value of ΔΨm at which the ANT shifts from forward (i.e., bringing ADP into the matrix in exchange for ATP) to reverse (i.e., bringing ATP into the matrix in exchange for ADP) mode of operation is termed Erev_ANT (19). Erev_ANT is given by Eq. 3:

| (3) |

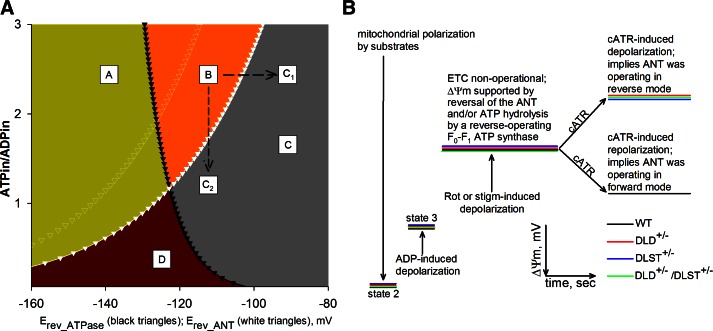

The values of Erev_ANT and Erev_ATPase were calculated using the above equations and parameters, as described previously (36), as a function of ΔΨm and matrix ATP/ADP ratio, and are depicted in Fig. 1A. As demonstrated previously (19), by inhibiting the respiratory chain of mitochondria respiring on substrates that support substrate-level phosphorylation, ΔΨm and matrix ATP/ADP ratio are clamped to values anywhere within the so-called B space (Fig. 1A, orange space; ref. 35). Mitochondria exhibiting such ΔΨm and matrix ATP/ADP ratio pair values that would place them in the B space hydrolyze ATP, but that cannot come from the extramitochondrial compartment, because the ANT did not reverse. Under these circumstances, mitochondria could enter the C space (Fig. 1A, gray space), where both the F0–F1 ATP synthase and the ANT operate in reverse mode and therefore gain access to extramitochondrial ATP pools by one or more of the following 3 routes: further change in ΔΨm toward more depolarizing values, so that they would reach point C1; further decrease in the matrix ATP/ADP ratio, so that they would reach point C2; or shift of Erev_ANT to the left (Fig. 1A, white open triangles; i.e., by increasing [ATP]out or decreasing [ADP]out or decreasing pHo), so that the existing ΔΨm and matrix ATP/ADP ratio pair values now fall within the C space. From Eq. 3, it is evident that because Erev_ANT encompasses the terms [ATP]in and [ADP]in, a change in matrix ATP/ADP ratio is bound to affect Erev_ANT as well. In other words, a change in matrix ATP/ADP ratio may not be the only reason for a mitochondrion becoming extramitochondrial ATP consumer; the accompanying shift in Erev_ANT will also contribute.

Figure 1.

A) Computational estimation of Erev_ANT and Erev_ATPase. Space A: ATPase forward, ANT forward; space B: ATP reverse, ANT forward; space C, points C1, C2: ATPase reverse, ANT reverse; space D: ATPase forward, ANT reverse. Black solid triangles represent Erev_ATPase; white solid triangles represent Erev_ANT. Values were computed for [ATP]out = 1.2 mM, [ADP]out = 10 μM, Pin = 0.01 M, n = 3.7 (2.7 + 1 for the electrogenic ATP4−/ADP3− exchange of the ANT), pHin = 7.38, and pHout = 7.25. White open triangles represent Erev_ANT values computed for [ATP]out = 1.4 mM, and all other parameters as above. B) Cartoon graph of all safranine O-related measurement from all kinds of mitochondria and conditions (see Fig. 2).

Identifying mitochondria as extramitochondrial ATP consumers

To label a respiration-impaired mitochondrion as an extramitochondrial ATP consumer, its ΔΨm and matrix ATP/ADP ratio pair of values must be anywhere within the C space of Fig. 1A. Due to the dynamism of ΔΨm, matrix ATP/ADP ratio, Erev_ATPase and Erev_ANT values that define the borders of the C space, it is experimentally exceptionally challenging to measure all these parameters and judge at any given time if a mitochondrion consumes extramitochondrial ATP. Instead, for this purpose it is much simpler and equally informative to examine the effect of ANT inhibitors on ΔΨm during ADP-induced respiration (19, 35, 36). Adenine nucleotide exchange through the ANT is electrogenic, since 1 molecule of ATP4− is exchanged for 1 molecule of ADP3− (40). In fully energized mitochondria, export of ATP in exchange for ADP costs ∼25% of the total energy produced (41). Therefore, during the forward mode of ANT, abolition of its operation by an ANT inhibitor, such as cATR or BKA, will lead to a gain of ΔΨm, whereas during the reverse mode of ANT, abolition of its operation by the inhibitor will lead to a loss of ΔΨm. This biosensor test (i.e., the effect of cATR on isolated, or BKA on in situ mitochondria obtained from WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− transgenic mice) was employed to address the directionality of ANT during respiratory inhibition. A generalized scheme of this test is depicted in Fig. 1B.

Categorization of substrates used for isolated mitochondria

Using isolated mitochondria, we were afforded the capacity to manipulate the substrates that the organelles respired on. Substrates can be categorized to those that participate directly in the citric acid cycle (α-ketoglutarate, succinate, fumarate, and malate), and those that participate indirectly (pyruvate, aspartate, and glutamate) or not at all (β-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate). An alternative categorization is to those that support substrate-level phosphorylation vs. those that do not. Glutamate and α-ketoglutarate are the two substrates that support substrate-level phosphorylation to the greatest extent. Malate alone does not support substrate-level phosphorylation, but it assists in the entry of many substrates in mitochondria, including glutamate and α-ketoglutarate, thus indirectly supporting substrate-level phosphorylation. Pyruvate and aspartate alone or in combination support substrate-level phosphorylation very weakly. β-Hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate alone do not support substrate-level phosphorylation, but the latter leads to NAD+ regeneration that could boost substrate-level phosphorylation supported by glutamate (or α-ketoglutarate). β-Hydroxybutyrate would work in the exact opposite way; i.e., it does not support substrate-level phosphorylation when glutamate or α-ketoglutarate is used because it competes for NAD+ with KGDHC. This claim is validated later on, showing that addition of β-hydroxybutyrate to glutamate plus malate exacerbated the differences between cATR-induced changes in ΔΨm of WT and KGDHC-deficient mice during inhibition of complex I; by the same token, addition of acetoacetate to glutamate plus malate decreased the differences between cATR-induced changes in ΔΨm of the WT and the KGDHC-deficient mice during inhibition of complex I (see below). Likewise, β-hydroxybutyrate or acetoacetate did not assist malate in boosting substrate-level phosphorylation. Succinate and fumarate disfavor substrate-level phosphorylation.

Effect of cATR on ΔΨm during respiratory inhibition in isolated brain mitochondria from WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice

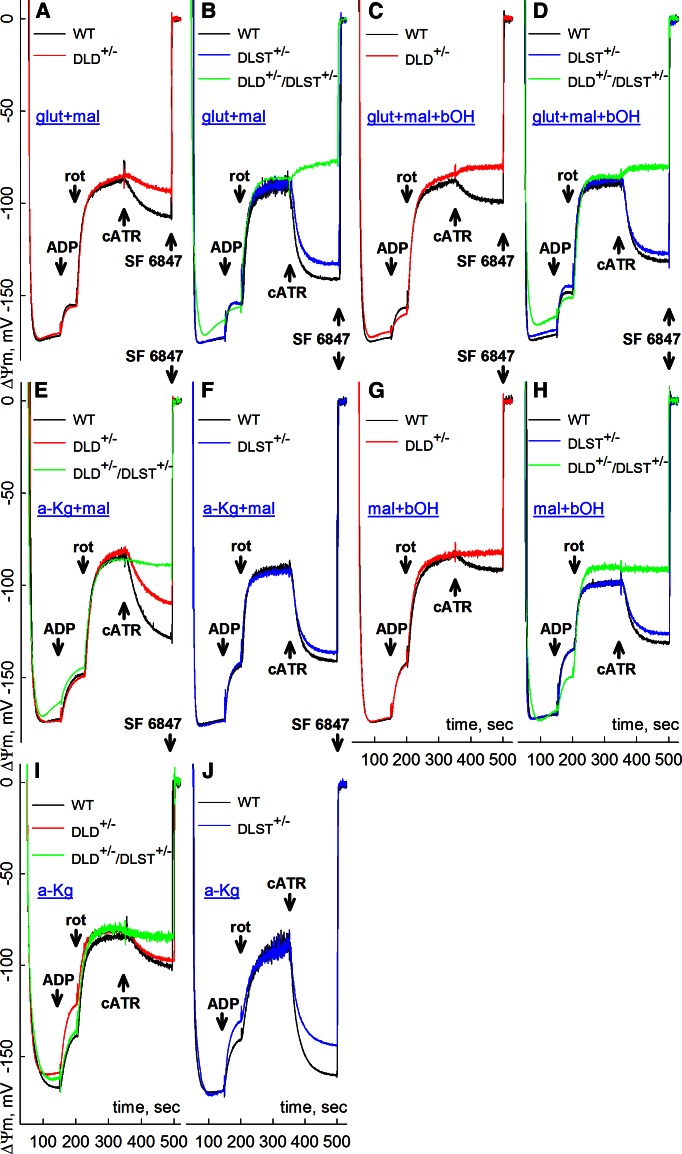

As shown in Fig. 2, ΔΨm was measured by safranine O fluorescence in Percoll-purified brain mitochondria obtained from WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/− and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice and calibrated as detailed in Materials and Methods. Based on experiments performed first with liver mitochondria where yields were high (Supplemental Figs. S1–S5), specific substrates and their combinations were selected to investigate brain mitochondria where much lower yields are typically obtained. The sequence of additions, identical for all panels, was the following: mitochondria were allowed to polarize, followed by the addition of 2 mM ADP, where indicated. ADP would depolarize mitochondria to a variable level depending on the substrate combinations (27). After 50 s, during which a substantial amount of ADP has been converted to ATP, complex I was inhibited by rotenone (1 μM), which clamped ΔΨm in the −83- to −99-mV range, again depending on substrate combinations. After an additional 150 s, cATR (2 μM) was added. Toward the end of each experiment, the uncoupler SF 6847 (1 μM) was added in order to completely depolarize mitochondria; this would assist in the calibration of the safranine O signal.

Figure 2.

Effect of cATR (2 μM) on ΔΨm of mouse brain mitochondria of WT vs. DLD+/− (A, C, E, G, I), DLST+/− (B, D, F, H, J), or DLD+/−/DLST+/− double-transgenic mice (B, D, E, H, I) compromised at complex I by rotenone (rot; 1 μM), in the presence of different substrate combinations: glutamate + malate (A, B), glutamate + malate + β-hydroxybutyrate (C, D), α-ketoglutarate + malate (E, F), malate + β-hydroxybutyrate (G, H), and α-ketoglutarate (I, J). ADP (2 mM) was added where indicated. Substrate concentrations: glutamate (glut), 5 mM; malate (mal), 5 mM; β-hydroxybutyrate (bOH), 2 mM; α-ketoglutarate (a-Kg), 5 mM. At the end of all experiments, 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization. The WT mice compared with the DLD+/− littermate mice are of C57BL/6 genetic background. The WT mice compared with the littermate DLST+/− mice are of C57BL/6 and 129SV/EV hybrid genetic background. DLD+/−/DLST+/− double transgenic mice are of either C57BL/6 only or C57BL/6 and 129SV/EV hybrid genetic background. Because of this background heterogeneity, some of the traces from WT mice appear in several panels in order to match as littermates of the KGDHC-deficient mice.

In all panels of Fig. 2, it is evident that addition of cATR to respiration-impaired mitochondria obtained from WT mice resulted in the gain of ΔΨm, indicating that the ANT was operating in forward mode. However, addition of cATR to respiration-impaired mitochondria obtained from DLD+/− (Fig. 2C), and DLD+/−/DLST+/− (Fig. 2B, D) mice resulted in the loss of ΔΨm, implying that the ANT was operating in reverse mode. Therefore, for the corresponding substrates, respiration-impaired mitochondria of KGDHC-deficient mice imported extramitochondrial ATP. Addition of succinate to any substrate combination in brain mitochondria of WT or KGDHC-deficient mice resulted in cATR-induced depolarization, attributed to the shifting of the SUCL equilibrium toward ATP consumption, as described previously (ref. 19; not shown for brain, see Supplemental Figs. S1–S5 for liver mitochondria). No swelling was observed under any circumstances (see Supplemental Figs. S8 and S9); therefore, the losses of ΔΨm were not due to opening of the permeability transition pore. For other substrate combinations, addition of cATR to KGDHC-deficient mitochondria was either causing less repolarization (Fig. 2A, E, I for DLD+/−; B, J for DLST+/−) than WT littermates, no difference compared to WT (Fig. 2F), or no effect (Fig. 2G, H; red and green traces, respectively); in the latter case, this means that the values of ΔΨm and Erev_ANT were identical.

Results obtained using the cATR biosensor test (Fig. 2), in conjunction with the thermodynamic considerations mentioned above (Fig. 1), imply that, using substrate combinations supporting substrate-level phosphorylation in mitochondria obtained from KGDHC transgenic mice compared to those from WT littermates, Erev_ANT values were more negative, and/or matrix ATP/ADP ratios were lower. Besides the function of the ANT, matrix ATP/ADP ratios are primarily (but not exclusively) affected by the reversible mechanisms producing or consuming ATP. In the mitochondrial matrix the two most significant contributors are the F0–F1 ATP synthase and the ATP-forming SUCL. The GTP-forming SUCL still contributes to the matrix ATP pools due to the concerted action of nucleoside diphosphokinase, converting GTP and ADP to GDP and ATP (42). The activity of the F0–F1 ATP synthase but not of SUCL strongly depends on ΔΨm (22, 37, 43). We therefore investigated ATP efflux and respiration rates from fully energized mitochondria of WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice for various substrates in the absence of confounding factors, such as respiratory inhibition, that would lead to membrane depolarization.

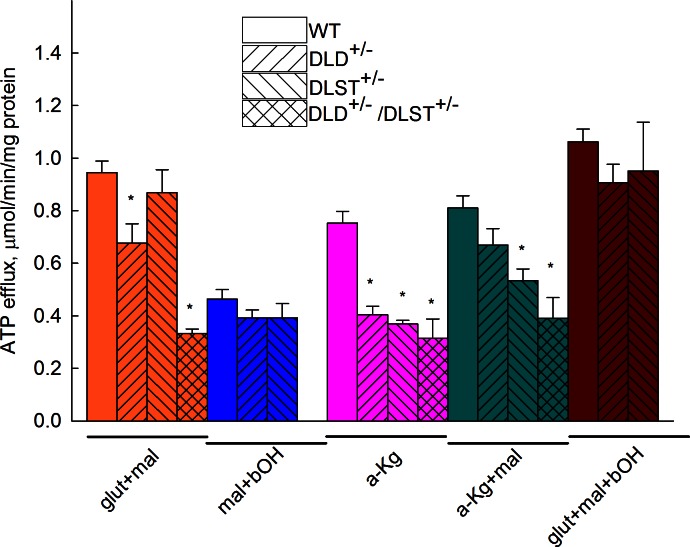

ATP efflux rates in brain mitochondria from WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice

Figure 3 shows ATP efflux rates of isolated brain mitochondria obtained from WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− transgenic mice and calibrated as detailed in Materials and Methods. In DLST+/− liver mitochondria, all substrates and their combinations yielded lower ATP efflux rates than WT littermates. It is evident that in KGDHC-deficient brain mitochondria, those substrates and their combinations supporting substrate-level phosphorylation yielded lower ATP efflux rates than WT littermates (glutamate+malate, α-ketoglutarate, α-ketoglutarate+malate). From these results, we conclude that mitochondria deficient in DLD and/or DLST subunit of KGDHC may exhibit diminished ATP efflux rates depending on substrates used. For those substrate combinations that do not support substrate-level phosphorylation (malate+β-hydroxybutyrate), no difference was found in the ATP efflux rates among WT and KGDHC-deficient liver mitochondria. However, the substrate combination glutamate + malate + β-hydroxybutyrate also did not show a statistically significant difference in ATP efflux rates among WT and KGDHC-deficient mice, nor for glutamate + malate for DLST+/− vs. WT mice or α-ketoglutarate + malate for DLD+/− vs. WT mice.

Figure 3.

ATP efflux rates of isolated brain mitochondria of WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/− and DLD+/−/ DLST+/− mice as a function of various substrate combinations. Substrate concentrations: glutamate (glut), 5 mM; malate (mal), 5 mM; β-hydroxybutyrate (bOH), 2 mM;, α-ketoglutarate (a-Kg), 5 mM). P values for the various substrate combination groups: glut+mal, P < 0.001; a-Kg, P < 0.001; a-Kg+mal, P < 0.001. *P < 0.05 vs. WT control mice; 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test post hoc analysis if comparing ≥3 groups.

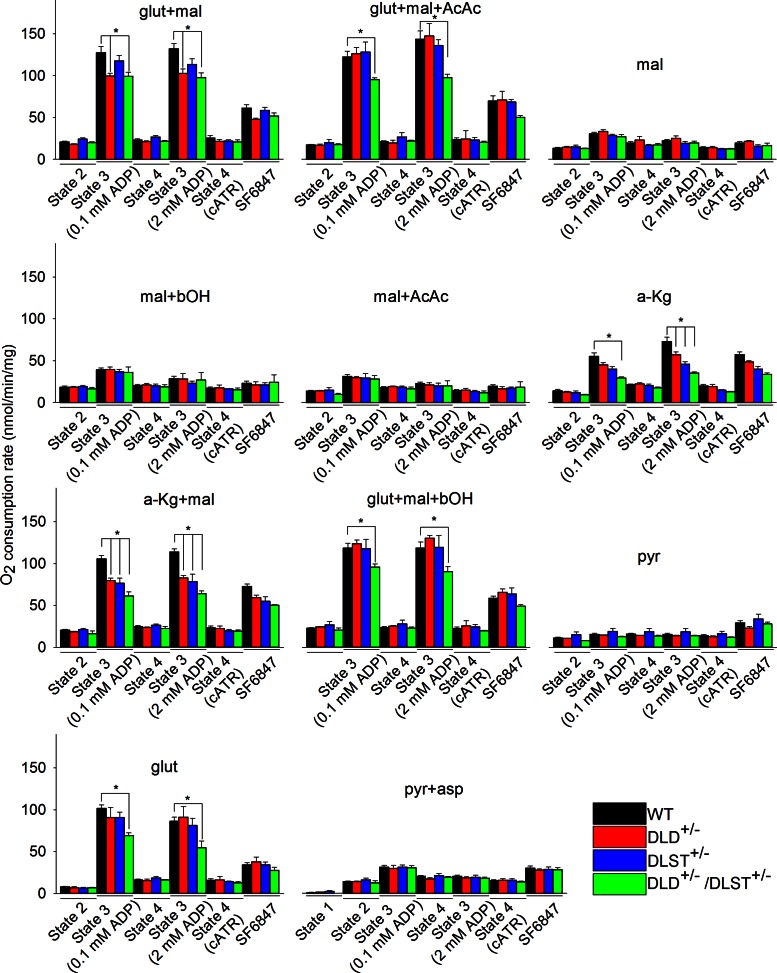

Respiration rates in isolated brain mitochondria from WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice

To investigate the possibility that cATR-induced alterations in ΔΨm are due to membrane leaks, we measured mitochondrial respiration. Respiration rates were measured during state 2; state 3 induced by a small bolus of ADP (0.1 mM); state 4 (on phosphorylation of the entire amount of ADP); state 3 reinduced by a large bolus of ADP (2 mM); state 4 induced by cATR, and uncoupled respiration induced by SF 6847 (50 nM for brain and 170 nM for liver mitochondria). Experiments were performed for isolated brain (and liver, shown in Supplemental Fig. S7) mitochondria from WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− transgenic mice for all substrate combinations. Each substrate combination was repeated 4–6 times on independent occasions. Quantitative data in bar graph format are shown in Fig. 4. It is evident that in KGDHC-deficient brain mitochondria, several substrates and their combinations supporting substrate-level phosphorylation yielded lower respiration rates than WT littermates (glutamate+malate, glutamate+malate+acetoacetate, α-ketoglutarate, α-ketoglutarate+malate, glutamate+malate+β-hydroxybutyrate, glutamate). From these results, we conclude that mitochondria deficient in DLD and/or DLST subunit of KGDHC exhibited diminished respiration rates. For those substrates and their combinations that support only weakly substrate-level phosphorylation (malate, malate+β-hydroxybutyrate, malate+acetoacetate, pyruvate, pyruvate+aspartate), no difference was found in the respiration rates among WT and KGDHC-deficient brain mitochondria. These data are in congruence with the ATP efflux data shown in Fig. 3. Furthermore, state 2 respiration and state 4 respiration (whether induced after phosphorylation of the entire bolus of ADP given or induced by cATR) was not statistically significantly different for any substrate combination among WT and KGDHC-deficient mice, arguing against a possible contribution from leaks to the changes in membrane potential shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 4.

Respiration rates of isolated brain mitochondria of WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/ DLST+/− mice for various substrate combinations indicated in the panels. Substrate concentrations: glutamate (glut), 5 mM; malate (mal), 5 mM; acetoacetate (AcAc), 0.5 mM; β-hydroxybutyrate (bOH), 2 mM; α-ketoglutarate (a-Kg), 5 mM; pyruvate (pyr), 5 mM; aspartate (asp), 5 mM. At the end of each experiment, 50 nM SF 6847 was administered. P values were as follows: glut-mal: 0.1 mM ADP bolus, 0.002; glut-mal with 2 mM ADP bolus, 0.002; glut-mal-AcAc: 0.1 mM ADP bolus, 0.026; 2 mM ADP bolus, 0.006; α-Kg: 0.1 mM ADP bolus, 0.002; 2 mM ADP bolus, <0.001; α-Kg-mal: 0.1 mM ADP bolus, <0.001; 2 mM ADP bolus, <0.001; glut+mal+bOH: 0.1 mM ADP bolus, 0.021; 2 mM ADP bolus, 0.015; glut: 0.1 mM ADP bolus, 0.011; 2 mM ADP bolus, 0.022. State 1 (no mitochondria, no substrates) is shown only in bottom middle panel (pyr+asp). *P < 0.05 vs. WT control mice; 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test post hoc analysis.

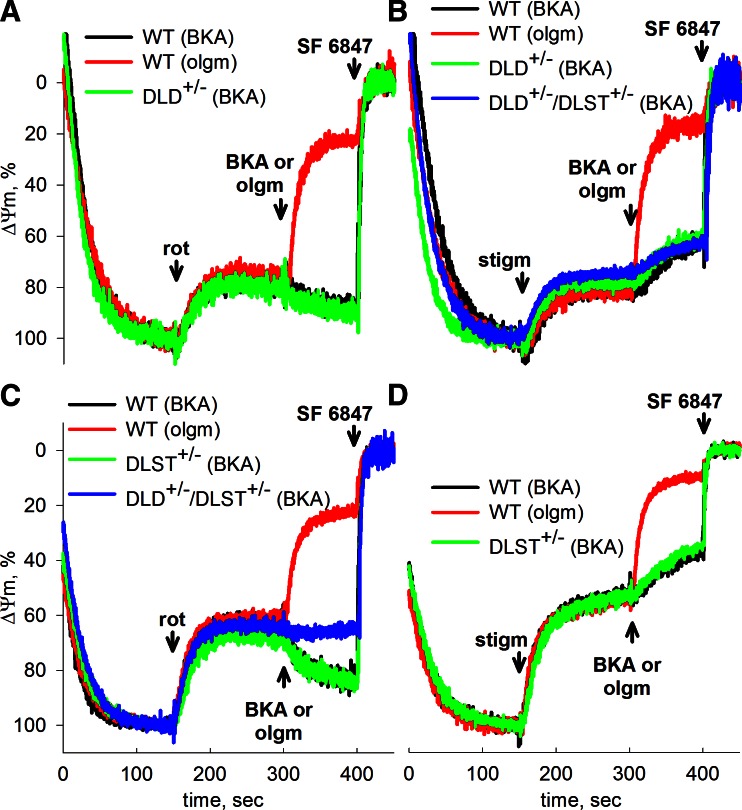

Effect of BKA during respiratory inhibition of in situ synaptic and neuronal somal mitochondria from WT and transgenic mice

In the above experiments using isolated mitochondria, the choice of substrate was a controlled variable. We therefore addressed whether the differences in ANT directionalities can be demonstrated among WT and transgenic mice in in situ mitochondria, where substrate is an uncontrolled variable. For this purpose, isolated nerve terminals (synaptosomes) and cultured cortical neurons were prepared from the brains of WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice. Also, BKA was used to inhibit the ANT instead of cATR, because the former can penetrate the plasma membrane, but the latter cannot. The same principles as detailed above apply here for identifying whether in situ synaptic mitochondria consume extramitochondrial ATP. The experimental protocol for the synaptosomes was the following (Fig. 5): synaptosomes were incubated in an extracellular-like buffer, supplemented with 15 mM glucose as the sole energy substrate, and ΔΨm was measured by TMRM fluorescence, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Addition of the uncoupler SF 6847 at the end of each experiment, causing the complete collapse of ΔΨm, assisted in the normalization of the TMRM signal of all traces. In this in situ mitochondrial model, mitochondria respire, albeit submaximally (44). Application of the complex I inhibitor, rotenone (1 μM; Fig. 5A, C) or the complex III inhibitor, stigmatellin (1.2 μM; Fig. 5B, D) caused a significant depolarization. Subsequent addition of oligomycin (10 μg/ml; Fig. 5A, C, red traces) caused a nearly complete collapse of ΔΨm, implying that in situ mitochondria relied on ATP hydrolysis by the F0–F1 ATPase. However, addition of BKA in lieu of oligomycin led to a robust repolarization in WT, DLD+/−, and DLST+/− mice (Fig. 5A, C, black and green traces), implying that the ANT was still operating in the forward mode. Only in synaptosomes prepared from DLD+/−/DLST+/− double-transgenic mice did BKA cause almost no repolarization (Fig. 5C, blue trace), followed by a delayed minor depolarization. This implied that in double-transgenic animals, net adenine nucleotide flux through the ANT of rotenone-treated in situ synaptic mitochondria is near zero, and perhaps importing minor amounts of synaptoplasmic ATP into the matrix. Synaptosomes of WT mice inhibited by stigmatellin did not exhibit BKA-induced repolarization (Fig. 5B, D, black traces), and neither did those obtained from DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice (Fig. 5B, D, green and blue traces). It must be emphasized that KGDHC determinations from synaptosomal preparations (see Fig. 7) also involve enzymes from contaminating isolated mitochondria, the extent of which cannot be reliably estimated from the various transgenic mouse colonies. Therefore, the results obtained from the TMRM measurements of in situ mitochondria from the isolated nerve terminals cannot be reliably correlated to the extent of maximal KGDHC activity from the exact same mitochondria.

Figure 5.

Effect of BKA and oligomycin on the rotenone- or stigmatellin-evoked depolarization of ΔΨm in isolated nerve terminals of WT vs. DLD+/− mice (A, B), or WT vs. DLST+/− (C, D) or DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice (B, C). ΔΨm was followed using the potentiometric probe TMRM. Concentrations: BKA, 20 μM; oligomycin (olgm), 10 μg/ml; rotenone (rot), 1 μM; stigmatellin (stigm), 1.2 μM. At the end of each experiment, 1 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization.

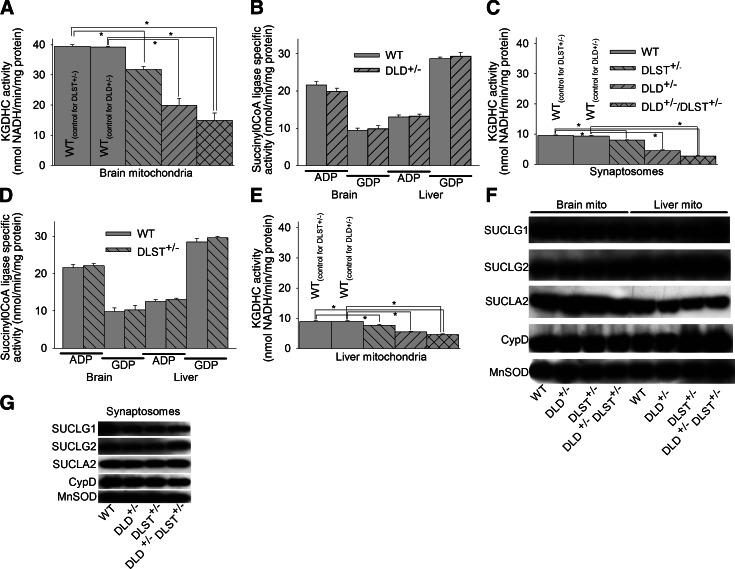

Figure 7.

Enzymatic activities of KGDHC and SUCL and immunoreactivities of the subunits of the latter enzyme in isolated liver and brain mitochondria and synaptosomes. A, C, E) KGDHC activities of isolated brain mitochondria (A), synaptosomes (C), and isolated liver mitochondria (E) of WT, DLST+/−, DLD+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/−transgenic mice. *P < 0.05; 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test post hoc analysis. B, D) SUCL activities (ATP- and GTP-forming) of isolated liver and brain mitochondria of WT vs. DLD+/− (B) and WT vs. DLST+/− mice (D). F, G) Immunoreactivities of SUCLG1, SUCLG2, SUCLA2 subunits of SUCL; (CypD); and MnSOD of isolated brain and liver mitochondria (F) and synaptosomes (G) of WT, DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice.

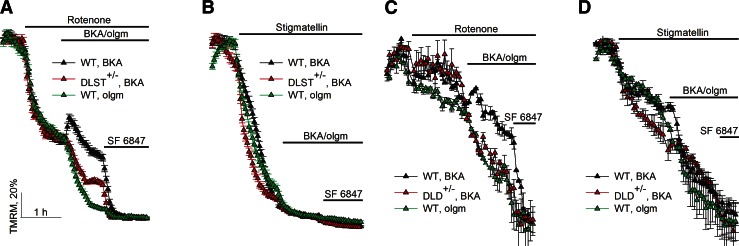

Results obtained from cultured cortical neurons are shown in Fig. 6. Neurons of DLST+/− vs. WT mice are compared in Fig. 6A, B; neurons of DLD+/− vs. WT mice in Fig. 6C, D. For all panels, the experimental paradigm was similar to that applied for synaptosomes. Cultures were bathed in an extracellular-like buffer, supplemented with 15 mM glucose as the sole substrate, and ΔΨm was measured by TMRM fluorescence, as detailed in Materials and Methods. Addition of the uncoupler SF 6847 at the end of each experiment, causing the complete collapse of ΔΨm, assisted in the normalization of the TMRM signal of all traces. Rotenone (1 μM) or stigmatellin (1.2 μM) was applied where indicated to inhibit in situ mitochondrial respiration, causing a significant depolarization. Subsequent addition of oligomycin (10 μg/ml) caused a nearly complete collapse of ΔΨm (Fig. 6, green traces), implying that respiration-impaired in situ mitochondria relied on ATP hydrolysis by the F0–F1 ATPase. However, when in situ mitochondria were inhibited by rotenone, subsequent addition of BKA in lieu of oligomycin led to a repolarization in WT cultures (Fig. 6A, C, black traces), unlike in cultures obtained from DLD+/− and DLST+/− mice where a depolarization was observed (Fig. 6A, C, red traces). This implied that respiration-impaired in situ neuronal somal mitochondria of DLD+/− and DLST+/− mice were consuming extramitochondrial ATP. Application of stigmatellin (1.2 μM) in lieu of rotenone caused a large depolarization, and subsequent addition of BKA in either WT or transgenic mice neurons did not confer any repolarization (Fig. 6B, D, black traces). The results obtained from in situ somal neuronal mitochondria using stigmatellin are supported by results obtained from Percoll-purified mitochondria (which consist of both somal neuronal and astrocytic mitochondria), where a very large depolarization was observed (not shown).

Figure 6.

Effect of BKA and oligomycin on the rotenone- or stigmatellin-evoked depolarization of ΔΨm in cultured mouse cortical neurons of WT vs. DLST+/− mice (A, B), or WT vs. DLD+/− mice (C, D). ΔΨm was followed in intact cells with confocal (A, B) or epifluorescence (C, D) microscopy using the potentiometric probe TMRM. Concentrations: BKA (black triangles), 20 μM; oligomycin (olgm; green triangles), 10 μg/ml; rotenone (where indicated, red triangles), 1 μM; stigmatellin (where indicated, red triangles), 1.2 μM. Data were pooled from 13 cell culture preparations. Data points obtained by epifluorescent imaging represent means ± sem of 2 view fields/well containing 50–60 neurons/condition. Data points obtained by confocal imaging represent means ± sem of 3 view fields/well containing 90–120 neurons/condition. At the end of each experiment, 5 μM SF 6847 was added to achieve complete depolarization.

KGDHC and succinyl-CoA maximal activities in tissues from WT and transgenic mice

SUCL has been reported to coprecipitate with KGDHC (45); therefore, alterations in KGDHC due to genetic manipulations could have an effect on SUCL. To address this possibility, we measured KGDHC activity and succinyl-CoA ATP-and GTP-forming activities in isolated liver and brain mitochondria and synaptosomes obtained from WT and transgenic mice, as well as immunoreactivities of all three subunits of SUCL. We were unable to measure KGDHC and SUCL activity from cultured neurons, due to limitations on the available tissue (i.e., neurons from one pup brain were sufficient to cover a single Lab-Tek chamber). SUCL is a heterodimer enzyme, composed of an invariant α subunit encoded by SUCLG1 and a substrate-specific β subunit encoded by either SUCLA2 or SUCLG2. This dimer combination results in either an ATP-forming SUCL (EC 6.2.1.5) or a GTP-forming SUCL (EC 6.2.1.4). Results on KGDHC activities are shown in Fig. 7A (isolated brain mitochondria), C (synaptosomes), E (isolated liver mitochondria). Immunoreactivities of SUCLG1, SUCLG2, and SUCLA2 from the same tissues are shown in Fig. 7F, G. As shown in Fig. 7A and consistent with previous reports (11, 17), KGDHC activity of DLD+/− and DLST+/− brain mitochondria was reduced by 20–48%, compared to WT littermates. KGDHC activity of double-transgenic DLD+/−/DLST+/− brain and liver isolated mitochondria was reduced by 62 and 50%, respectively. On the contrary, succinyl-CoA ATP- or GTP-forming maximal activities were not different between WT and transgenic mice. This finding is in accordance with the findings regarding immunoreactivities of the subunits of the SUCL enzyme, showing no differences between WT and any KGDHC transgenic mice (Fig. 7F, G). These results strongly suggest that the effect of genetic manipulations of KGDHC on matrix substrate-level phosphorylation is solely due to decreased provision of succinyl-CoA.

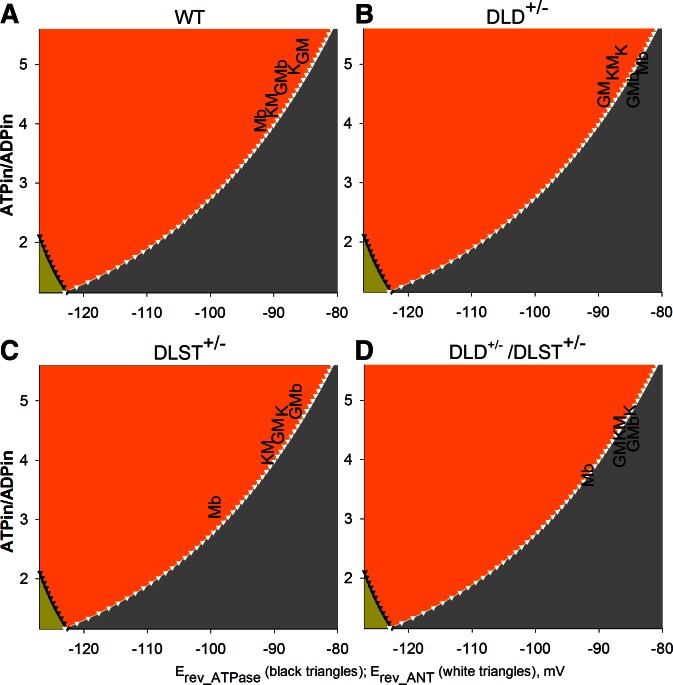

Predictions of matrix ATP/ADP ratios for each substrate combination used for isolated brain mitochondria from WT vs. KGDHC-deficient mice, after inhibition by rotenone

From the ΔΨm values extracted from Fig. 2, the cATR-induced de- or repolarization for each substrate combination indicating the directionality of the ANT, and the thermodynamic considerations appearing in Fig. 1, we can predict the range of matrix ATP/ADP ratios for these conditions after inhibition of complex I of the respiratory chain. These predictions are depicted in Fig. 8A for mitochondria from WT mice, Fig. 8B for mitochondria from DLD+/− mice, Fig. 8C for mitochondria from DLST+/− mice, and Fig. 8D for mitochondria from DLD+/−/DLST+/− mice. Substrates are indicated by a single letter as detailed in the legend. For each substrate combination found in the B space (Fig. 8, orange), matrix ATP/ADP ratio may have a value from Erev_ANT for the respective membrane potential and upwards. If the substrate combination is found in the C space (Fig. 8, gray), the matrix ATP/ADP ratio may have a value from Erev_ANT for the respective membrane potential until theoretical zero. As shown in Fig. 8 for brain mitochondria, and in Supplemental Fig. S10 for liver mitochondria, several substrate combinations supporting substrate-level phosphorylation appear in the B space in WT mice, while the substrate combinations appear in the C space in KGDHC-deficient mice. Substrate combinations that disfavor substrate-level phosphorylation appear exclusively in the C space for both WT and KGDHC-deficient mice.

Figure 8.

Predicted ranges of matrix ATP/ADP ratios (ATP/ADPin) for each substrate combination used for brain mitochondria from WT mice (A) vs. DLD+/− (B), DLST+/− (C), and DLD+/−/DLST+/− (D) KGDHC-deficient mice, after inhibition by rotenone. Substrates: G, glutamate; M, malate; b, β-hydroxybutyrate; K, α-ketoglutarate. For each substrate combination found in the B space (orange), the range of values that the matrix ATP/ADP ratio may attain is from Erev_ANT for the respective membrane potential and upwards. If the substrate combination is found in the C space (gray), the range of values that the matrix ATP/ADP ratio may attain is from Erev_ANT for the respective membrane potential until theoretical zero.

DISCUSSION

KGDHC is at a crossroad of biochemical pathways, and as such, greatly affects the overall cell metabolism. It is therefore not surprising that diminished KGDHC activity of transgenic mice results in alterations of glucose utilization, a hallmark of metabolic abnormality, albeit depending on the model (46, 47). Yet, extensive work on transgenic mice for 2 of the 3 subunits of KGDHC failed to pinpoint the exact mechanisms responsible. In view of this gap of information, the most important aim of the present study was to address the effect of a decreased KGDHC activity on matrix substrate-level phosphorylation in isolated and in situ mitochondria with diminished ΔΨm values achieved by respiratory inhibition.

The rationale of this aim is manifold: provision of succinyl-CoA through KGDHC is much higher than that originating from propionyl-CoA metabolism (48); matrix substrate-level phosphorylation provides ATP in the matrix parallel to that by oxidative phosphorylation (6, 29, 49); SUCL does not require oxygen to produce ATP, and it is even activated during hypoxia (50); in ischemia and/or hypoxia, there is mounting evidence of pronounced conversion of α-ketoglutarate to succinate, implying that KGDHC is operational (51, 52–67); brains from patients with autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer's disease exhibited significant decreases in the activities of the enzymes in the first part of the citric acid cycle (pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, −41%; isocitrate dehydrogenase, −27%; and KGDHC, −57%), while enzyme activities of the second half of the cycle were increased (succinate dehydrogenase, +44%; and malate dehydrogenase, +54%) (8, 9). It is as though reactions after the SUCL step were up-regulated in order to remove succinate and shift the equilibrium toward ATP formation, given the diminished succinyl-CoA provision. ΔΨm values in neurons are far from being static; in physiological conditions, ΔΨm is regulated between −108 and −158 mV by concerted increases in ATP demand and Ca2+-dependent metabolic activation (68), a range that would assign mitochondrial phosphorylation within the A, B, or C space of Fig. 1A (no conditions have been described that are suitable for the D space; ref. 35); the implications of the latter statement is that even under physiological conditions, mitochondria are not only ATP producers, but could also be consumers of ATP arising from the cytosol and/or the matrix, depending on their ΔΨm and matrix ATP/ADP ratio pair of values.

A potential drawback of our work is that we could not explicitly measure succinyl-CoA flux. This is technically extremely challenging; current state-of-the-art isotopomeric analysis would fall short in measuring fluxes of succinyl-CoA (69, 70), but more important, such information would be insufficient unless coupled to another measured parameter with a more profound effect, such as ATP flux across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Therefore, we relied on a biosensor approach, measuring the effect of ANT inhibition of respiration-impaired mitochondria on ΔΨm, during which the organelles are exquisitely dependent on matrix substrate-level phosphorylation (19). It is a great strength of this work that we benefitted from transgenic animals exhibiting 20–48% decrease in KGDHC activity, a condition that does not evoke severe metabolic aberrations.

Mindful of the above considerations and the results of the present work, the scenario that could be unfolding in the presence of diminished KGDHC activity, is the following: KGDHC exhibits a high flux control coefficient for producing reducing equivalents in the citric acid cycle, also implying that provision of succinyl-CoA would be diminished when the enzyme complex is partially inhibited (especially because metabolism of propionyl-CoA yields only small amounts of succinyl-CoA); in turn, this would lead to a decreased production of ATP in the mitochondrial matrix from substrate-level phosphorylation. This was reflected in the smaller ATP efflux rates in isolated mitochondria from DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− double-transgenic mice compared to WT littermates, in the absence of respiratory inhibitors. The diminished production of ATP in the mitochondrial matrix from substrate-level phosphorylation results in a decrease in matrix ATP/ADP ratio, which is also a term in Eq. 3 defining Erev_ANT, thereby shifting its values to the left in the computed graph of Fig. 1A. Since ΔΨm of mitochondria varies within a wide range even under physiological conditions, the likelihood of the organelles becoming extramitochondrial ATP consumers increases with shifting Erev_ANT values toward more negative potentials. Here we have demonstrated the consumption of extramitochondrial ATP by mitochondria of DLD+/−, DLST+/−, and DLD+/−/DLST+/− double-transgenic mice provided with substrates supporting substrate-level phosphorylation, by clamping ΔΨm in a depolarized range due to targeted respiratory inhibition. Using the same substrates and their combinations, consumption of extramitochondrial ATP was not observed in isolated mitochondria of WT mice; likewise, cytosolic ATP was consumed by in situ neuronal somal mitochondria of DLD+/− and DLST+/−, but not WT mice. In addition to the fact that KGDHC-deficient mitochondria exhibit diminished ATP output when fully polarized, excessive reliance of submaximally polarized mitochondria on extramitochondrial ATP poses an overall metabolic stress. This renders the cell less capable of dealing with unrelated circumstantial challenges predisposing to neurodegenerative diseases, as is already shown to occur in situ (71, 72), or in vivo (11, 13, 14).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant P01 AG014930 to G.E.G., A.A.S.. and M.F.B.; NIH/National Institute of Neurological Disease and Stroke grant F31 NS054554 to H.K.; NIH grant 1R21NS065396 to A.A.S.; NIH grant R01 GM088999 to G.M.; grants from the Országos Tudományos Kutatási Alapprogram (OTKA), Magyar Tudományos Akadémia (MTA) to V.A.-V.; and grants MTA-SE Lendület Neurobiochemistry Research Division 95003, OTKA NNF 78905, OTKA NNF2 85658, OTKA K 100918, and Egészségügyi Tudományos Tanács ETT 55160 to C.C.

The authors thank Katalin Zölde for excellent technical assistance. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- ΔΨm

- mitochondrial membrane potential

- ANT

- adenine nucleotide translocase

- BKA

- bongkrekic acid

- cATR

- carboxyatractyloside

- CypD

- cyclophilin D

- DLD

- dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase

- DLST

- dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase

- Erev_ANT

- reversal potential of ANT

- Erev_ATPase

- reversal potential of F0–F1 ATPase

- KGDH

- α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase

- KGDHC

- α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex

- MnSOD

- manganese superoxide dismutase

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- SF 6847

- 3,5-di-tert-butyl-4-hydroxybenzylidenemalononitrile

- SUCL

- succinyl-CoA ligase

- TCA

- tricarboxylic acid

- TMRM

- tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

- WT

- wild type

REFERENCES

- 1. Sheu K. F., Blass J. P. (1999) The alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 893, 61–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gibson G. E., Park L. C., Sheu K. F., Blass J. P., Calingasan N. Y. (2000) The alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex in neurodegeneration. Neurochem. Int. 36, 97–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cooper A. J. (2012) The role of glutamine synthetase and glutamate dehydrogenase in cerebral ammonia homeostasis. Neurochem. Res. 37, 2439–2455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atamna H., Frey W. H. (2004) A role for heme in Alzheimer's disease: heme binds amyloid beta and has altered metabolism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 11153–11158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Atamna H., Liu J., Ames B. N. (2001) Heme deficiency selectively interrupts assembly of mitochondrial complex IV in human fibroblasts: revelance to aging. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 48410–48416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnson J. D., Mehus J. G., Tews K., Milavetz B. I., Lambeth D. O. (1998) Genetic evidence for the expression of ATP- and GTP-specific succinyl-CoA synthetases in multicellular eucaryotes. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27580–27586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanamori T., Nishimaki K., Asoh S., Ishibashi Y., Takata I., Kuwabara T., Taira K., Yamaguchi H., Sugihara S., Yamazaki T., Ihara Y., Nakano K., Matuda S., Ohta S. (2003) Truncated product of the bifunctional DLST gene involved in biogenesis of the respiratory chain. EMBO J. 22, 2913–2923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bubber P., Haroutunian V., Fisch G., Blass J. P., Gibson G. E. (2005) Mitochondrial abnormalities in Alzheimer brain: mechanistic implications. Ann. Neurol. 57, 695–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gibson G. E., Starkov A., Blass J. P., Ratan R. R., Beal M. F. (2010) Cause and consequence: mitochondrial dysfunction initiates and propagates neuronal dysfunction, neuronal death and behavioral abnormalities in age-associated neurodegenerative diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1802, 122–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bubber P., Hartounian V., Gibson G. E., Blass J. P. (2011) Abnormalities in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in the brains of schizophrenia patients. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21, 254–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yang L., Shi Q., Ho D. J., Starkov A. A., Wille E. J., Xu H., Chen H. L., Zhang S., Stack C. M., Calingasan N. Y., Gibson G. E., Beal M. F. (2009) Mice deficient in dihydrolipoyl succinyl transferase show increased vulnerability to mitochondrial toxins. Neurobiol. Dis. 36, 320–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson M. T., Yang H. S., Magnuson T., Patel M. S. (1997) Targeted disruption of the murine dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase gene (Dld) results in perigastrulation lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 14512–14517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Klivenyi P., Starkov A. A., Calingasan N. Y., Gardian G., Browne S. E., Yang L., Bubber P., Gibson G. E., Patel M. S., Beal M. F. (2004) Mice deficient in dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase show increased vulnerability to MPTP, malonate and 3-nitropropionic acid neurotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 88, 1352–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Browne S. E., Beal M. F. (2002) Toxin-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 53, 243–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Calingasan N. Y., Ho D. J., Wille E. J., Campagna M. V., Ruan J., Dumont M., Yang L., Shi Q., Gibson G. E., Beal M. F. (2008) Influence of mitochondrial enzyme deficiency on adult neurogenesis in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroscience 153, 986–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dumont M., Ho D. J., Calingasan N. Y., Xu H., Gibson G., Beal M. F. (2009) Mitochondrial dihydrolipoyl succinyltransferase deficiency accelerates amyloid pathology and memory deficit in a transgenic mouse model of amyloid deposition. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 1019–1027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Starkov A. A., Fiskum G., Chinopoulos C., Lorenzo B. J., Browne S. E., Patel M. S., Beal M. F. (2004) Mitochondrial alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex generates reactive oxygen species. J. Neurosci. 24, 7779–7788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. (2004) Generation of reactive oxygen species in the reaction catalyzed by alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. J. Neurosci. 24, 7771–7778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chinopoulos C., Gerencser A. A., Mandi M., Mathe K., Torocsik B., Doczi J., Turiak L., Kiss G., Konrad C., Vajda S., Vereczki V., Oh R. J., Adam-Vizi V. (2010) Forward operation of adenine nucleotide translocase during F0F1-ATPase reversal: critical role of matrix substrate-level phosphorylation. FASEB J. 24, 2405–2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sims N. R. (1990) Rapid isolation of metabolically active mitochondria from rat brain and subregions using Percoll density gradient centrifugation. J. Neurochem. 55, 698–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chinopoulos C., Starkov A. A., Fiskum G. (2003) Cyclosporin A-insensitive permeability transition in brain mitochondria: inhibition by 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27382–27389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chinopoulos C., Konrad C., Kiss G., Metelkin E., Torocsik B., Zhang S. F., Starkov A. A. (2011) Modulation of F0F1-ATP synthase activity by cyclophilin D regulates matrix adenine nucleotide levels. FEBS J. 278, 1112–1125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Smith P. K., Krohn R. I., Hermanson G. T., Mallia A. K., Gartner F. H., Provenzano M. D., Fujimoto E. K., Goeke N. M., Olson B. J., Klenk D. C. (1985) Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 150, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dunkley P. R., Jarvie P. E., Robinson P. J. (2008) A rapid Percoll gradient procedure for preparation of synaptosomes. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1718–1728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chinopoulos C., Gerencser A. A., Doczi J., Fiskum G., Adam-Vizi V. (2004) Inhibition of glutamate-induced delayed calcium deregulation by 2-APB and La3+ in cultured cortical neurones. J. Neurochem. 91, 471–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Akerman K. E., Wikstrom M. K. (1976) Safranine as a probe of the mitochondrial membrane potential. FEBS Lett. 68, 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chinopoulos C., Vajda S., Csanady L., Mandi M., Mathe K., Adam-Vizi V. (2009) A novel kinetic assay of mitochondrial ATP-ADP exchange rate mediated by the ANT. Biophys. J. 96, 2490–2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Alarcon C., Wicksteed B., Prentki M., Corkey B. E., Rhodes C. J. (2002) Succinate is a preferential metabolic stimulus-coupling signal for glucose-induced proinsulin biosynthesis translation. Diabetes 51, 2496–2504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lambeth D. O., Tews K. N., Adkins S., Frohlich D., Milavetz B. I. (2004) Expression of two succinyl-CoA synthetases with different nucleotide specificities in mammalian tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36621–36624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rouslin W., Erickson J. L., Solaro R. J. (1986) Effects of oligomycin and acidosis on rates of ATP depletion in ischemic heart muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 250, H503–H508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McMillin J. B., Pauly D. F. (1988) Control of mitochondrial respiration in muscle. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 81, 121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Petronilli V., Azzone G. F., Pietrobon D. (1988) Analysis of mechanisms of free-energy coupling and uncoupling by inhibitor titrations: theory, computer modeling and experiments. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 932, 306–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rouslin W., Broge C. W., Grupp I. L. (1990) ATP depletion and mitochondrial functional loss during ischemia in slow and fast heart-rate hearts. Am. J. Physiol. 259, H1759–H1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wisniewski E., Kunz W. S., Gellerich F. N. (1993) Phosphate affects the distribution of flux control among the enzymes of oxidative phosphorylation in rat skeletal muscle mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 9343–9346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chinopoulos C. (2011) The “B space” of mitochondrial phosphorylation. J. Neurosci. Res. 89, 1897–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chinopoulos C. (2011) Mitochondrial consumption of cytosolic ATP: not so fast. FEBS Lett. 585, 1255–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Metelkin E., Demin O., Kovacs Z., Chinopoulos C. (2009) Modeling of ATP-ADP steady-state exchange rate mediated by the adenine nucleotide translocase in isolated mitochondria. FEBS J. 276, 6942–6955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Watt I. N., Montgomery M. G., Runswick M. J., Leslie A. G., Walker J. E. (2010) Bioenergetic cost of making an adenosine triphosphate molecule in animal mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107, 16823–16827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Martell A. E., Smith R. M. (1974) Critical Stability Constants. Plenum Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 40. Klingenberg M. (2008) The ADP and ATP transport in mitochondria and its carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778, 1978–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alexandre A., Reynafarje B., Lehninger A. L. (1978) Stoichiometry of vectorial H+ movements coupled to electron transport and to ATP synthesis in mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75, 5296–5300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kadrmas E. F., Ray P. D., Lambeth D. O. (1991) Apparent ATP-linked succinate thiokinase activity and its relation to nucleoside diphosphate kinase in mitochondrial matrix preparations from rabbit. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1074, 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Demin O. V., Westerhoff H. V., Kholodenko B. N. (1998) Mathematical modelling of superoxide generation with the bc1 complex of mitochondria. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 63, 634–649 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. (2007) Uncoupling is without an effect on the production of reactive oxygen species by in situ synaptic mitochondria. J. Neurochem. 103, 1864–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Porpaczy Z., Sumegi B., Alkonyi I. (1983) Association between the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and succinate thiokinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 749, 172–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shi Q., Risa O., Sonnewald U., Gibson G. E. (2009) Mild reduction in the activity of the alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex elevates GABA shunt and glycolysis. J. Neurochem. 109(Suppl. 1), 214–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nilsen L. H., Shi Q., Gibson G. E., Sonnewald U. (2011) Brain [U-13 C]glucose metabolism in mice with decreased alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex activity. J. Neurosci. Res. 89, 1997–2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stryer L. (1995) Biochemistry, W.H. Freeman, New York [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nicholls D. G., Bernson V. S. (1977) Inter-relationships between proton electrochemical gradient, adenine-nucleotide phosphorylation potential and respiration, during substrate-level and oxidative phosphorylation by mitochondria from brown adipose tissue of cold-adapted guinea-pigs. Eur.J. Biochem. 75, 601–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Phillips D., Aponte A. M., French S. A., Chess D. J., Balaban R. S. (2009) Succinyl-CoA synthetase is a phosphate target for the activation of mitochondrial metabolism. Biochemistry 48, 7140–7149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chinopoulos C. (2013) Which way does the citric acid cycle turn during hypoxia? The critical role of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. [E-pub ahead of print] J. Neurosci. Res. doi: 10.1002/jnr.23196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Pisarenko O., Studneva I., Khlopkov V., Solomatina E., Ruuge E. (1988) An assessment of anaerobic metabolism during ischemia and reperfusion in isolated guinea pig heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 934, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peuhkurinen K. J., Takala T. E., Nuutinen E. M., Hassinen I. E. (1983) Tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolites during ischemia in isolated perfused rat heart. Am. J. Physiol. 244, H281–H288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sanborn T., Gavin W., Berkowitz S., Perille T., Lesch M. (1979) Augmented conversion of aspartate and glutamate to succinate during anoxia in rabbit heart. Am. J. Physiol. 237, H535–H541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pisarenko O. I., Solomatina E. S., Ivanov V. E., Studneva I. M., Kapelko V. I., Smirnov V. N. (1985) On the mechanism of enhanced ATP formation in hypoxic myocardium caused by glutamic acid. Basic Res. Cardiol. 80, 126–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pisarenko O., Studneva I., Khlopkov V. (1987) Metabolism of the tricarboxylic acid cycle intermediates and related amino acids in ischemic guinea pig heart. Biomed. Biochim. Acta 46, S568–S571 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hunter F. E., Jr. (1949) Anaerobic phosphorylation due to a coupled oxidation-reduction between alpha-ketoglutaric acid and oxalacetic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 177, 361–372 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chance B., Hollunger G. (1960) Energy-linked reduction of mitochondrial pyridine nucleotide. Nature 185, 666–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Randall H. M., Jr., Cohen J. J. (1966) Anaerobic CO2 production by dog kidney in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. 211, 493–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sanadi D. R., Fluharty A. L. (1963) On the mechanism of oxidative phosphorylation. VII. The energy-requiring reduction of pyridine nucleotide by succinate and the energy-yielding oxidation of reduced pyridine nucleotide by fumarate. Biochemistry 2, 523–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Penney D. G., Cascarano J. (1970) Anaerobic rat heart. Effects of glucose and tricarboxylic acid-cycle metabolites on metabolism and physiological performance. Biochem. J. 118, 221–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Wilson M. A., Cascarano J. (1970) The energy-yielding oxidation of NADH by fumarate in submitochondrial particles of rat tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 216, 54–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Taegtmeyer H., Peterson M. B., Ragavan V. V., Ferguson A. G., Lesch M. (1977) De novo alanine synthesis in isolated oxygen-deprived rabbit myocardium. J. Biol. Chem. 252, 5010–5018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Taegtmeyer H. (1978) Metabolic responses to cardiac hypoxia. Increased production of succinate by rabbit papillary muscles. Circ. Res. 43, 808–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chick W. L., Weiner R., Cascareno J., Zweifach B. W. (1968) Influence of Krebs-cycle intermediates on survival in hemorrhagic shock. Am. J. Physiol. 215, 1107–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Weinberg J. M., Venkatachalam M. A., Roeser N. F., Saikumar P., Dong Z., Senter R. A., Nissim I. (2000) Anaerobic and aerobic pathways for salvage of proximal tubules from hypoxia-induced mitochondrial injury. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 279, F927–F943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Weinberg J. M., Venkatachalam M. A., Roeser N. F., Nissim I. (2000) Mitochondrial dysfunction during hypoxia/reoxygenation and its correction by anaerobic metabolism of citric acid cycle intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97, 2826–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gerencser A. A., Chinopoulos C., Birket M. J., Jastroch M., Vitelli C., Nicholls D. G., Brand M. D. (2012) Quantitative measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential in cultured cells: calcium-induced de- and hyperpolarization of neuronal mitochondria. J. Physiol. 590, 2845–2871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zacharias N. M., Chan H. R., Sailasuta N., Ross B. D., Bhattacharya P. (2012) Real-time molecular imaging of tricarboxylic acid cycle metabolism in vivo by hyperpolarized 1-(13)C diethyl succinate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 934–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Alves T. C., Jarak I., Carvalho R. A. (2012) NMR methodologies for studying mitochondrial bioenergetics. Methods Mol. Biol. 810, 281–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chinopoulos C., Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. (1999) Depolarization of in situ mitochondria due to hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in nerve terminals: inhibition of alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. J. Neurochem. 73, 220–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tretter L., Adam-Vizi V. (2000) Inhibition of Krebs cycle enzymes by hydrogen peroxide: A key role of α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in limiting NADH production under oxidative stress. J. Neurosci. 20, 8972–8979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.