Abstract

Objective:

To review the evidence base for different treatment strategies in intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis in adults and children.

Method:

A literature search of Medline, EMBASE, LILACS, and the Cochrane Database from 1980 to 2008, updated in 2012, resulted in the identification of 10 Class I or Class II trials of cysticidal drugs administered with or without corticosteroids in the treatment of neurocysticercosis.

Results:

The available data demonstrate that albendazole therapy, administered with or without corticosteroids, is probably effective in decreasing both long-term seizure frequency and the number of cysts demonstrable radiologically in adults and children with neurocysticercosis, and is well-tolerated. There is insufficient information to assess the efficacy of praziquantel.

Recommendations:

Albendazole plus either dexamethasone or prednisolone should be considered for adults and children with neurocysticercosis, both to decrease the number of active lesions on brain imaging studies (Level B) and to reduce long-term seizure frequency (Level B). The evidence is insufficient to support or refute the use of steroid treatment alone in patients with intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis (Level U).

Cysticercosis, infection with the larval form of Taenia solium, is widely prevalent in developing countries of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It is considered by the WHO to be the most common preventable cause of epilepsy in the developing world, with an estimated 2 million people having epilepsy caused by T solium infection.1 Humans can acquire 2 different forms of infection—by eating raw or undercooked pork containing T solium cysts or by eating food contaminated with T solium eggs. Cysts consumed in undercooked meat mature into adult parasites in the human intestine, at which time they release eggs and gravid proglottids in the stool. This form of intestinal infection is called taeniasis. When T solium eggs are consumed, through fecal–oral transmission from another human with taeniasis or through autoinfection, they release oncospheres into the host's digestive tract and can then migrate throughout the host's body, becoming encysted in end organs. This systemic infection is called cysticercosis. Seeding of larvae in the CNS results in neurocysticercosis. Neurocysticercosis, in turn, may affect the CNS parenchyma or the CSF space. In this guideline, we focus solely on parenchymal infections.

Cysticercal cysts evolve through 4 stages, with different appearances on neuroimaging—the vesicular stage, where the cyst contains a living larva; a colloidal stage as the larva degenerates; a “granulo-nodular” stage as the membrane of the cyst thickens; and the final stage of calcification. Only cysts in the vesicular and colloidal stages contain live larvae2 and are amenable to anticysticercal treatment. Encysted larvae can remain asymptomatic for years. When the larvae do elicit a host immune response, patients can develop brain edema and, more often, seizures. Optimal treatment of this infection has been the subject of considerable debate, with controversy regarding the appropriate role of both corticosteroids and cysticidal drugs such as praziquantel or albendazole for active infections.

To address this controversy, we performed a systematic review of the literature regarding the following specific clinical questions:

In patients with symptomatic intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis, is cysticidal therapy more effective than no therapy, and does it affect long-term seizure outcome?

In patients with symptomatic intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis, is treatment with corticosteroids more effective than no treatment?

When during the course of antiparasitic treatment should steroids be started?

What is the efficacy of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in treating or decreasing occurrence of subsequent seizures secondary to intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis, and what is the optimal time course of AED treatment for seizures secondary to intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis?

DESCRIPTION OF THE ANALYTIC PROCESS

Because cysticercosis is quite prevalent in Latin America, a number of relevant studies have been published in the Spanish-language literature. Therefore, a comprehensive search was performed of both English- and Spanish-language articles (with the latter reviewed by 2 panel members, J.R.Z. and S.W., who are fluent in Spanish) in Medline, EMBASE, LILACS, and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from 1980 to 2008, using the search terms “neurocysticercosis,” “cerebral cysticercosis,” “brain cysticercosis,” “antiparasitic agents,” “antihelmintics,” “cysticidal,” “clinical trials,” “research design,” “antiseizure,” “anticonvulsant,” “antiepileptic,” “albendazole,” “praziquantel,” “steroid,” “corticosteroid,” “anti-inflammatory agents,” “hydrocortisone,” “prednisone,” “prednisolone,” “dexamethasone,” and “neurosurgery” (see appendix e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org for complete search strategy). The search identified 590 citations. An updated search of Medline and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews was performed in January 2012 and identified an additional 20 citations. Each abstract was reviewed by at least 2 reviewers. Review articles without primary data, case reports, and small case series were discarded. The remaining pertinent 123 articles were reviewed in detail, and data regarding cohort size, patient characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, completion rate, treatment and dosage, study design, study length, primary and secondary outcomes, efficacy, and effect size were extracted from each article and tabulated using a data extraction form. Each article was classified according to the American Academy of Neurology therapeutic classification of evidence scheme (see appendix e-4).

Risk differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used as the preferred measure of effect and statistical precision. When necessary to increase statistical precision, studies with the lowest risk of bias were pooled in a fixed-effects meta-analysis. Class II studies were included in the meta-analysis only when precision was insufficient after Class I studies were pooled.

ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE

In patients with symptomatic intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis, is cysticidal therapy more effective than no therapy, and does it affect long-term seizure outcome?

Treatment efficacy can be judged by a radiologic surrogate marker—the numbers of remaining active and inactive cysts—and clinically by the number of patients experiencing seizures after treatment. Of note in these studies, patients received anticonvulsants initially, most often phenytoin, but this was not explicitly controlled as part of the treatment protocols. Also of note, although some of the cited studies were limited to patients with active cysts, some included individuals with transitional cysts, in which the parasite is already dead or dying. Because cysticidal therapy would not be expected to affect the disease course if the organism were already dead, this may actually have led to an underestimation of treatment efficacy.

Three Class I3−5 (1 Class I for imaging only5 and Class IV for clinical measures, including seizure frequency) and 6 Class II studies6–11 (1 Class II for imaging studies only6) addressed cysticidal therapy (administered with or without steroids) in the initial treatment of neurocysticercosis. One11 of the Class II studies compared albendazole alone with albendazole with praziquantel without a control group and therefore was not informative regarding whether antihelminthic therapy is useful. (There was no difference in any outcome measure between the 2 regimens.) Five of the remaining Class II studies were restricted to the pediatric population.7–11 One of these studies was Class II for imaging studies only.9 One Class I study3 included adults only. Two Class I studies3,4 and all 5 pediatric Class II studies7–11 combined corticosteroid treatment with cysticidal therapy.

One randomized controlled trial (RCT) (Class I) evaluated 120 patients with viable parenchymal cysts and seizures who were assigned to receive either albendazole (800 mg/day) plus dexamethasone (6 mg/day, both for 10 days) or 2 placebos.3 During months 2–30 following treatment, there was a nonsignificant 46% reduction in the number of total seizures (95% CI 74% to 83%) in the albendazole/dexamethasone group as compared with placebo and a significant 67% reduction in number of seizures with generalization (95% CI 20% to 86%, p = 0.01). At 6-month follow-up the number of patients with active cysts on imaging studies was significantly lower in patients receiving active treatment than in those receiving placebo (p < 0.007). Therapy was well-tolerated with the exception of abdominal pain and nausea, which were reported more commonly in the treatment group. The studies do not state whether gastrointestinal prophylaxis was used.

An RCT (Class II) in 29 patients with multiple cystic lesions on CT (cysts of all types, excluding only calcified cysts)6 who received either albendazole (15 mg/kg/day for 7 days) or placebo showed no significant difference in total number of lesions or resolution of cysts on head CT at 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months. Seizure outcomes were not reported.

A third RCT, in which all patients had active or transitional (i.e., vesicular evolving into colloidal) cysts,4 assigned 88 patients to receive albendazole (800 mg/day, or weight based, for 8 days) and oral prednisone (75 mg/day or weight based) and 90 patients to receive prednisone and placebo. At 1 month, cysts had disappeared in 31% of those receiving albendazole and in 7% of those receiving prednisone alone (p < 0.001). When Kaplan-Meyer projections were applied, at 12 months 62% of patients receiving albendazole were seizure-free vs 52% of controls (not significant).

In a fourth RCT,5 in which all patients had contrast-enhancing cysts, 33 patients received 3 days of albendazole (15 mg/kg for 3 days, without corticosteroids), and 34 patients received placebo. At 6 months, cysts had resolved completely in 85% of those receiving albendazole and in 41% of those receiving placebo (p < 0.001). Seizure frequency was low in both groups at 6-month follow-up, with no significant difference in frequency.

In the pediatric population, 4 Class II studies provide conflicting results for radiologic outcomes but used differing criteria. Two studies7,9 (63 patients and 93 patients, respectively) found a decrease in active lesions in patients receiving albendazole (15 mg/kg/day for 28 days in both, prednisolone 1–2 mg/kg/day for the first 5 days in the first, dexamethasone 0.15 mg/kg/day for 5 days in the second). In the first study, CT scans performed 3 months after treatment showed disappearance of active lesions in 64.5% of patients treated with albendazole and in 37.5% of controls. In the second study, CT scans performed at 3 months demonstrated complete or partial resolution of cysts in 79% of patients given treatment vs in 57% of controls. Two8,10 studies (with 53 patients and 110 patients, respectively) found no difference in the number of patients in whom lesions disappeared (treatment albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 28 days, with prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day for 3 days before albendazole in the first; albendazole 15 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks, prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day for 21 days, and then a 1-week taper in the second). In the first, cysts disappeared on 6-month follow-up CT scan in 54% of patients receiving treatment and in 55% of those receiving placebo. In the second, single cysts disappeared on 3-month follow-up CT in 53% of patients receiving steroids, in 60% of those receiving albendazole, and in 63% of those receiving both treatments. One Class II study7 showed a decrease in late recurrent seizures among treated patients, although the numbers were small in both groups, and the difference was not significant. One Class II study10 showed cysticidal therapy was beneficial in reducing seizure recurrence.

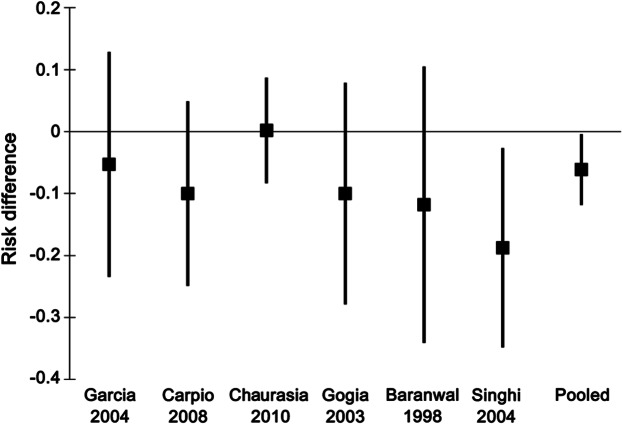

To increase the precision of the estimate of the effectiveness of albendazole regarding seizure frequency, we performed a meta-analysis combining the 2 Class I3,4 and 4 Class II studies5,7,8,10 with comparable data (figure). Overall, there was a 6.1% decrease in the risk of having seizures (95% CI 0.3% to 11.9%, number needed to treat = 16).

Figure. Effect on seizure risk.

Meta-analysis, combining data from the 2 Class I and 4 Class II studies with outcome data regarding seizure risk (proportion of treated patients with seizures relative to proportion of untreated patients with seizures).

Conclusion.

Based on imaging findings in 4 Class I studies (3 concordant, 1 underpowered study failing to show an effect) and a meta-analysis of 2 Class I and 4 Class II studies, albendazole (400 mg BID for adults or weight-based dosing for either adults or children) is probably safe and effective in reducing both the number of cysts and long-term seizure frequency in adults and children with neurocysticercosis. In most studies, corticosteroids were coadministered, in varying dosages, and this combination appears effective. Data are insufficient to indicate whether corticosteroids are necessary in this setting.

Clinical context.

The available studies have used different stratification methods for seizure analysis and different criteria for judging improvement in imaging. On the basis of the 3 Class I studies it appears albendazole plus corticosteroids decreases the number of active brain lesions relative to placebo and, on the basis of a meta-analysis of available data, decreases the number of patients with seizures, at modest cost. These findings appear to be consistent in adults and children.

Side effects of treatment appear minimal. Of greatest concern has been the potential—emphasized in a single large study12—for increased seizures and encephalopathy as a result of treatment-induced parasite death. This study, in which all patients had multiple cysts (with 5 or more cysts in over 25% of patients) and in which neither allocation nor treatment was concealed, was considered to be Class IV and therefore not considered contributory. Of the 3 Class I or II studies that reported seizure frequency during treatment,3,4,7 none showed an increase in seizure frequency with treatment (pooled risk difference vs placebo −0.1%, 95% CI −6.2% to 5.9%). Only 2 studies3,4 detailed other side effects. In the first study3 headaches occurred in 32 of 60 patients given treatment vs in 31 of 60 controls; dizziness occurred in 9 patients vs in 4, and abdominal complaints occurred in 8 vs in 0. Only the last finding was significant; however, patients given treatment in this study all received corticosteroids, whereas controls did not. In the second study, headaches occurred in 59 of 88 patients given treatment vs in 53 of 90 controls; abdominal complaints occurred in 38 vs in 40 (neither side-effect finding being significant).

Recommendations often emphasize the danger of antihelminthic treatment in patients with a very large lesion burden. The cited studies all excluded patients with massive cerebral edema or innumerable lesions but were otherwise inconsistent. Three studies5,7,10 were limited to patients with single lesions. In one study, patients had 1 or 2 cysts.9 In another study, 84% of patients had 1 or 2; the remainder had fewer than 100. In the remaining 3 studies, the number of cysts was described as “multiple,”6 “less than 20,”3 and “less than 36.”4

Recommendation.

Albendazole plus either dexamethasone or prednisolone should be considered for adults and children with neurocysticercosis, both to decrease the number of active lesions on brain imaging studies (Level B) and to reduce long-term seizure frequency (Level B).

In patients with symptomatic intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis, is treatment with corticosteroids more effective than no treatment?

One Class I study13 and one Class II/Class IV study14 assessed steroid treatment without administration of cysticidal therapy. In the Class I study, 148 patients with solitary cysts were randomized to receive prednisolone (40–60 mg/day on the basis of weight for 2 weeks, followed by a 4-day taper) or placebo. At 3 months there were no differences in imaging findings or in overall seizure frequency between the 2 groups. Frequency of generalized seizures at follow-up was 16% in patients receiving corticosteroids and 60% in controls; frequency of focal seizures was 63% among those receiving methylprednisolone and 25% among controls (both differences significant).

The second study14 included 97 patients with new-onset seizures and a single enhancing CT lesion, randomized to receive AEDs plus prednisolone (prednisolone 1 mg/kg/day for 10 days, followed by a 4-day taper) or AED monotherapy alone. At 6-month follow-up, the CT lesions had disappeared in 88% of patients in the prednisolone group vs in 52% of those in the antiepileptic group (p = 0.003). The Kaplan-Meier estimated risk of seizure recurrence was significantly less in the prednisolone group (8.38; df 1; p < 0.01). Although the study showed benefit, the strength of evidence is Class II for CT resolution of lesions outcome and Class IV for seizure outcome.

Conclusion.

On the basis of one Class I study showing no benefit radiologically and ambiguous benefit clinically and one Class II/IV study showing benefit, there is insufficient evidence to recommend steroid treatment alone for patients with solitary intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis granulomata.

Clinical context.

The effect of corticosteroid treatment alone in neurocysticercosis has not been widely studied. Most trials include a combination of cysticidal therapy and steroid treatment.

Recommendation.

The evidence is insufficient to support or refute the use of steroid treatment alone in patients with intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis (Level U).

When during the course of antiparasitic treatment should steroids be started?

We found no studies to answer this question.

What is the efficacy of AEDs in treating or decreasing occurrence of subsequent seizures secondary to intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis, and what is the optimal time course of AED treatment for seizures secondary to intraparenchymal neurocysticercosis?

We found no studies to answer this question.

Clinical context.

Given the well-established efficacy and safety of a broad range of AEDs and the frequency with which neurocysticercosis causes seizures, it is reasonable to treat these patients with AEDs at least until the active lesions have subsided.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

Several aspects of treatment require further study.

Cysticercal cysts evolve through 4 stages: the living larva, the degenerating larva, a reactive thickening of the cyst membrane, and calcification. Only cysts in the first 2 stages contain live cysts.2 A study that evaluates the response to therapy on the basis of the stage of the cyst would be useful.

The successful treatment trials cited all used cysticidal therapy administered with or without corticosteroids. Studies are needed to determine the appropriate use and timing of administration of adjuvant corticosteroids and the potential benefit of combination cysticidal therapy.

Neurocysticercosis can be intraventricular or intraocular or can involve the subarachnoid space. Studies have not addressed these forms of the infection. Assessment of different treatment strategies, medical or surgical, for such patients would be helpful.

HIV coinfection may alter efficacy of antihelminthic treatment or produce important drug–drug interactions; determination of best treatment for neurocysticercosis in such patients is needed.

Additional studies should focus on clinical outcomes rather than surrogate CT outcomes, as the two do not always correlate. Patients may experience seizure recurrence despite resolution of lesions on CT.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- AED

antiepileptic drug

- CI

confidence interval

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

Footnotes

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ruth Ann Baird: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data. Samuel Wiebe: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data. Joseph Raymond Zunt: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data. John Halperin: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, statistical analysis, study supervision. Gary Gronseth: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, statistical analysis. Karen L. Roos: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

This guideline was developed with financial support from the American Academy of Neurology. None of the authors received reimbursement, honoraria, or stipends for their participation in development of this guideline.

DISCLOSURE

R.A. Baird has no disclosures to report. S. Wiebe has received honoraria from UCB Pharma Inc. and has received research funding from Alberta Heritage Medical Research Foundation, Canadian Institute for Health Research, MSI Foundation of Alberta, and the Hotchkiss Brain Institute of the University of Calgary. J.R. Zunt has received honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology and has received funding from the NIH on retroviral infections. J. Halperin has testified in several physician medical malpractice cases and aided the Connecticut Department of Health in proceedings regarding Lyme disease. G. Gronseth has served on a speakers' bureau for Boehringer Ingelheim (resigned December 2011), and receives honoraria from the American Academy of Neurology. K. Roos has received funding for travel from the American Academy of Neurology as a member of its Board of Directors. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

DISCLAIMER

This statement is provided as an educational service of the American Academy of Neurology. It is based on an assessment of current scientific and clinical information. It is not intended to include all possible proper methods of care for a particular neurologic problem or all legitimate criteria for choosing to use a specific procedure. Neither is it intended to exclude any reasonable alternative methodologies. The AAN recognizes that specific patient care decisions are the prerogative of the patient and the physician caring for the patient, based on all of the circumstances involved. The clinical context section is made available in order to place the evidence-based guideline(s) into perspective with current practice habits and challenges. Formal practice recommendations are not intended to replace clinical judgment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The American Academy of Neurology is committed to producing independent, critical, and truthful clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). Significant efforts are made to minimize the potential for conflicts of interest to influence the recommendations of this CPG. To the extent possible, the AAN keeps separate those who have a financial stake in the success or failure of the products appraised in the CPGs and the developers of the guidelines. Conflict of interest forms were obtained from all authors and reviewed by an oversight committee before project initiation. AAN limits the participation of authors with substantial conflicts of interest. The AAN forbids commercial participation in, or funding of, guideline projects. Drafts of the guideline have been reviewed by at least 3 AAN committees, a network of neurologists, Neurology peer reviewers, and representatives from related fields. The AAN Guideline Author Conflict of Interest Policy can be viewed at www.aan.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Coyle CM, Mahanty S, Zunt JR, et al. Neurocysticercosis: neglected but not forgotten. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012;6:e1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murthy JMK, Reddy YVS. Prognosis of epilepsy associated with single CT enhancing lesion: a long term follow-up study. J Neurol Sci 1998;159:151–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia HH, Pretell EJ, Gilman RH, et al. A trial of antiparasitic treatment to reduce the rate of seizures due to cerebral cysticercosis. N Engl J Med 2004;350:249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpio A, Kelvin EA, Bagiella E, et al. Effects of albendazole treatment on neurocysticercosis: a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2008;79:1050–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaurasia RN, Garg RK, Agarwal A, et al. Three day albendazole therapy in patients with a solitary cysticercus granuloma: a randomized double blind placebo controlled study. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2010;41:517–525 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padma MV, Behari M, Misra NK, Ahuja GK. Albendazole in neurocysticercosis. Natl Med J India 1995;8:255–258 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baranwal AK, Singhi PD, Khandelwal N, Singhi SC. Albendazole therapy in children with focal seizures and single small enhancing computerized tomographic lesions: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1998;17:696–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gogia S, Talukdar B, Choudhury V, Arora BS. Neurocysticercosis in children: clinical findings and response to albendazole therapy in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in newly diagnosed cases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2003;97:416–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalra VK, Dua T, Kumar V. Efficacy of albendazole and short-course dexamethasone treatment in children with 1 or 2 ring-enhancing lesions of neurocysticercosis: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr 2003;143:111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singhi P, Jain V, Khandelwal N. Corticosteroids versus albendazole for treatment of single small enhancing computed tomographic lesions in children with neurocysticercosis. J Child Neurol 2004;19:323–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaur S, Singhi P, Singhi S, Khandelwal N. Combination therapy with albendazole and praziquantel versus albendazole alone in children with seizures and single lesion neurocysticercosis: a randomized, placebo-controlled double blind trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009;28:403–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das K, Mondal GP, Banerjee M, Mukherjee BB, Singh OP. Role of antiparasitic therapy for seizures and resolution of lesions in neurocysticercosis patients: an 8 year randomised study. J Clin Neurosci 2007;14:1172–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singla M, Prabhakar S, Modi M, Medhi B, Khandelwal N, Lal V. Short-course of prednisolone in solitary cysticercus granuloma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia 2011;52:1914–1917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mall RK, Agarwal A, Garg RK, Kar AM, Skukla R. Short course of prednisolone in Indian patients with solitary cysticercus granuloma and new-onset seizures. Epilepsia 2003;44:1397–1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.