Background: Autosomal recessive mutation, sld, attenuates Muc19 expression.

Results: Intronic insertion of two CA repeats within the Muc19 coding region enhances retention of its downstream intron and degradation of resultant aberrant transcripts.

Conclusion: Effects of the intronic mutation explains decreased Muc19 mRNA stability in sld mice.

Significance: The novel splicing regulated by CA repeats is significant given this is a frequent genomic repeat motif.

Keywords: Gene Mapping, Mucins, Mutant, RNA Processing, RNA Splicing, Muc19, Nonsense-mediated Decay

Abstract

The autosomal recessive mutation, sld, attenuates mucous cell expression in murine sublingual glands with corresponding effects on mucin 19 (Muc19). We conducted a systematic study including genetic mapping, sequencing, and functional analyses to elucidate a mutation to explain the sld phenotype in neonatal mice. Genetic mapping and gene expression analyses localized the sld mutation within the gene Muc19/Smgc, specifically attenuating Muc19 transcripts, and Muc19 knock-out mice mimic the sld phenotype in neonates. Muc19 transcription is unaffected in sld mice, whereas mRNA stability is markedly decreased. Decreased mRNA stability is not due to a defect in 3′-end processing nor to sequence differences in Muc19 transcripts. Comparative sequencing of the Muc19/Smgc gene identified four candidate intronic mutations within the Muc19 coding region. Minigene splicing assays revealed a novel splicing event in which insertion of two additional repeats within a CA repeat region of intron 53 of the sld genome enhances retention of intron 54, decreasing the levels of correctly spliced transcripts. Moreover, pateamine A, an inhibitor of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, inhibits degradation of aberrant Muc19 transcripts. The mutation in intron 53 thus enhances aberrant splicing leading to degradation of aberrant transcripts and decreased Muc19 message stability, consistent with the sld phenotype. We propose a working model of the unique splicing event enhanced by the mutation, as well as putative explanations for the gradual but limited increase in Muc19 glycoprotein expression and its restricted localization to subpopulations of mucous cells in sld mice during postnatal gland development.

Introduction

Mucins are highly glycosylated glycoproteins whose genes are designated as MUC1 through MUC22, based upon their order of discovery. Mucins are grouped into three families: 1) large gel-forming and secreted mucins, 2) soluble and secreted mucins, and 3) membrane-associated mucins (1, 2). The large gel-forming mucins consist of Muc2, Muc5ac, Muc5b, Muc6, and Muc19. Gel-forming mucins are exocrine secretion products of surface goblet cells and glandular mucous cells of the airways, digestive tract, urogenital system, eyes, inner ear, and salivary system. These mucins polymerize into water-containing macromolecular networks with protective functions, including hydration and lubrication of tissue surfaces, as well as interaction with pathogens, either alone or as part of large molecular complexes with other molecules secreted in the mucus layer (3, 4). In human saliva, MUC5B is well recognized as a major mucin constituent (5), and MUC19 transcripts are localized to mucous cells of salivary glands (6).

In investigating salivary mucous cell biology, we study rodent sublingual glands (7–10). Muc19 glycoproteins are expressed in mucous cells of sublingual glands, as well as in minor mucous glands (11). Interestingly, minor mucous glands produce one or more additional gel-forming mucins (i.e., Muc5ac and Muc5b), whereas Muc19 is the sole gel-forming mucin of sublingual glands. Muc19 is also found in bulbourethral glands, the inner ear, and a subset of mucous cells within submucosal glands of the tracheolarynx, but not mucous cells of the gastrointestinal tract (11). Given the role of gel-forming mucins in lubrication and hydration, it is of interest to elucidate mechanisms that control Muc19 expression toward the potential future development of therapies to treat patients suffering with dry mouth caused by destruction of salivary glands during autoimmune disease or radiation treatment for head and neck cancer (12, 13). Unfortunately, appropriate in vitro systems to investigate molecular mechanisms controlling expression of gel-forming mucins in salivary cells are not readily available, in large part because of the absence of adequate culture conditions to maintain mucin expression by glandular mucous cells in primary culture (14), as well as the scarcity of cell lines derived from salivary glands.

As an alternative approach in delineating mechanisms controlling Muc19 expression, we study the NFS/N-sld mouse model. These mice harbor a spontaneous autosomal recessive mutation, sld, initially characterized as the delayed and limited development of mucous cells in sublingual salivary glands (15–17). We have since demonstrated that the sld mutation disrupts Muc19 expression as evidenced from ultrastructural and immunohistochemical studies, but without effects on the expression of other secreted proteins, as well as on global protein expression (15). Because Muc19 is the sole gel-forming mucin of sublingual glands, neonatal glands of sld mice are devoid of the large exocrine granules typical of the mucous cell phenotype. Nevertheless, the mucous cell phenotype begins to appear and increase in cell numbers postnatally. These cells all express Muc19 but are restricted because cells of the mucous cell phenotype make up less then half of the population of cells at 1 year of age (15). Correspondingly, Muc19 transcripts are barely detectable, and Muc19 glycoproteins are undetectable in sld neonates, although both gradually appear postnatally in conjunction with the increasing appearance of cells of the mucous cell phenotype (15).

Elucidation of the gene harboring the sld mutation, its genetic defect, and the mechanism through which Muc19 expression is disrupted may provide insights into factors regulating Muc19 expression and salivary mucous cell cytodifferentiation. For example, the defect may reside in the gene expressing Muc19 transcripts, Muc19/Smgc, or in a gene regulating Muc19 transcription or subsequent processing events (e.g., RNA splicing, nuclear export, or degradation). The gene Muc19/Smgc also encodes the splice variant Smgc to produce SMGC (submandibular gland protein C), an exocrine product of salivary glands expressed transiently during the exocrine cytodifferentiation of sublingual exocrine cells (18). In response to a developmentally regulated change in gene splicing, cells convert from expressing Smgc to Muc19 transcripts (18). Currently it is unknown whether Smgc expression is also affected in sublingual glands of sld mice, which may alter cytodifferentiation to Muc19 expression. We therefore report results of a systematic study of genetic mapping, sequencing, and functional analyses to elucidate a mutation to explain the sld phenotype in neonatal mice. An insertional mutation in intron 53 enhances retention of intron 54 to produce aberrant Muc19 transcripts targeted for degradation, thus explaining the observed decrease in Muc19 mRNA stability. To our knowledge, this is a novel case in which a microsatellite polymorphism in one intron affects splicing of the subsequent downstream intron. We further propose a working model of a mechanism through which insertion of CA repeats in intron 53 enhances the unique retention of a downstream intron. Finally, in light of our current knowledge of the postnatal expression of Muc19, we offer putative explanations for the gradual but limited postnatal increase in Muc19 glycoprotein expression and its restricted localization to subpopulations of mucous cells in sld mice.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Unless indicated, all basic salts and buffers were from Sigma, and molecular reagents and kits, enzymes, and culture reagents were from Invitrogen. All kits were used according to the manufacturers' instructions.

Animals and Collection of Glands

University of Florida, University of Cincinnati, and University of Rochester Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees approved all animal procedures. NFS/NCr and NFS/N-sld mice were from our own breeding colonies maintained under BSL2 conditions. NFS/NCr mice were obtained originally from the National Cancer Institute animal program (Charles River Laboratories, Frederick, MD). NFS/N-sld mice were obtained originally from the Central Institute for Experimental Animal (Kawasaki, Japan) as described previously (15). The mice were euthanized by exsanguination after carbon dioxide narcosis. Unless indicated, all excised tissues were blotted on filter paper, flash frozen, and stored in liquid nitrogen. To determine wet weight, frozen tissues were quickly weighed prior to use with a Mettler MT-5 microbalance (Mettler Toledo, Columbus, OH).

Genetic Mapping and RT-PCR of Transcripts in the Critical Region

Genomic DNA was isolated from kidneys using the DNeasy kit (Qiagen). Polymorphic genomic markers (sequence tagged sites (STSs))3 included established Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) STSs and STS markers D15Roc1–12 that we designed from genomic simple repeats as identified by the program COMPILE_SIMPLE of the RUMMAGE sequence annotation server (19). Chromosomal localization and amplicon sizes of MIT STSs are in supplemental Table S1. Primer sequences, amplicon sizes, GenBankTM accession numbers for D15Roc1–12, and PCR conditions are given in supplemental Table S2. To phenotype sld mutants, sublingual gland homogenates prepared from F2 mice at 3 weeks of age were assayed for the presence or near absence (mutant phenotype) of high molecular weight glycoproteins.

To isolate RNA, frozen tissues were homogenized directly in TRIzol reagent using a Mini Bead Beater 8 (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK) for 90 s in the presence of ∼500 mg of silicone carbide beads (1 mm in size). RNA was isolated as per manufacturer's instructions and treated with DNase I using Ambion's DNA-free reagent kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). RNA purity was assessed by capillary electrophoresis (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer; Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA). RNA integrity numbers ranged from 8.7 to 9.5. DNase I-treated RNA (5 μg) was reverse transcribed with random primers using the high capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems), and the resultant cDNA was purified with the QIAquick PCR purification system (Qiagen). RNA and cDNA were quantified using the Quant-iT RNA assay kit or the Quant-iT dsDNA HS assay kit with the Qubit fluorometer. The PCR conditions and specific primers used to detect transcripts in the critical interval are in supplemental Table S3. PCR products were confirmed by direct sequencing of gel-purified bands (QIAquick gel extraction kit; Qiagen).

PCR Amplification of Muc19 cDNA, Cloning, and DNA Sequencing

We previously sequenced Muc19 cDNA from wild type NFS/NCr mice (GenBankTM accession number AY570293) (7). For the current project, sequence from the 5′-end of mutant NFS/N-sld mice cDNA was derived from three overlapping clones produced using the Qiagen one-step RT-PCR kit. Total RNA from adult sublingual glands (1 μg; DNase digested) was reverse transcribed for 30 min at 50 °C with specific primers, and PCR was performed. The products were gel-purified and ligated into pCR Topo2.1, the resultant plasmids were transformed into DH10b cells, and purified DNA from expanded cell clones was sequenced. For a direct comparison, we also cloned sequence from exons 36–50 of NFS/NCr mice. To sequence the 3′-end of Muc19 cDNA from exons 50–60, we incorporated 3′-RLM-RACE (RNA ligase-mediated rapid amplification of cDNA ends) using the Ambion First Choice RLM-RACE kit (Austin, TX). RNA from both mouse strains were amplified and cloned. PCRs included an exon 50-specific 5′-primer and the 3′-outer RLM RACE primer. The subsequent reaction included the 3′-inner RLM RACE primer and the same Muc19 primer. Products were ligated, cloned, and sequenced (see supplemental Table S4 for primer sequences, amplicon sizes and PCR conditions for 5′-end and 3′-end clones).

PCR Amplification of Muc19 Genomic DNA, Cloning, and/or DNA Sequencing

Overlapping genomic segments of Muc19/Smgc were amplified using specific primer sets (see supplemental Tables S5 and S6 for primer sequences, amplicon sizes, and PCR conditions). Gel-purified products (QiaQuick PCR purification kit) were either sequenced directly or first cloned using the Topo XL PCR cloning kit. Sequences were compiled into contigs using AssemblyALIGN (version 1.0.9c; Oxford Molecular Group) and compared using ClusTalW alignments (MacVector, version 7.2.2; Oxford Molecular Group). All sequences had at least 3-fold coverage, each from a different DNA preparation. All of the sequencing was performed at the University of Florida Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research with an Applied Biosystems 3100 Genetic Analyzer with Big Dye chemistry (version 3.1).

Generation of Muc19 Knock-out Mice

Genomic DNA to create the 5′ and 3′ homologous arms of the targeting vector were generated by PCR of BAC DNA (clone E11, RPCI-22 BAC Library from 129S6/SvEvTac female mouse; BACPAC Resources, Oakland, CA). All primers and PCR conditions used in the production and genotyping of KO mice are given in supplemental Table S7. The 5′-arm PCR product was cut with BclI and ApaI (4,744-bp product), and the 3′-arm PCR product was cut with SacI and HindIII (2,462-bp products). The 5′-arm was inserted 5′ to the upstream loxP site of the selection cassette PGKneolox2DTA that encodes for neomycin under control of the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter (20), kindly provided by Dr. Rulang Jiang. A sequence from the STOP cassette, pBS302 (21), kindly provided by Dr. Rulang Jiang (GenBankTM accession number U51223), was inserted between the downstream loxP site, and diphtheria toxin A (DTA) was driven by the PGK promoter for negative selection. The vector was cloned into Electro 10 Blue cells (Stratagene) and sequenced, and the purified plasmid DNA was linearized with AdhI. Linearized plasmid was electroporated into 129S6/SvEvTac ES (embryonic stem) cells at the University of Cincinnati Gene Targeted Mouse Service. ES cell clones (after G418 selection) were screened initially by PCR using two primer sets to identify appropriately targeted cells. Positive ES cell clones identified by PCR were further verified for correct vector integration by Southern analysis. Templates for upstream and downstream probes were generated by PCR from genomic DNA. Southern blots were performed with random primed probes, and genomic DNA was cut with either PvuII or SphI using standard techniques. One ES cell clone was expanded and injected into C57Bl/6 blastocysts, resulting in six chimeric mice. The five chimeric males were mated to Black Swiss (NIHBS) females. Of 19 litters, a single agouti heterozygous F1 male was produced. Appropriate targeting of the male was confirmed by PCR as described above for ES cell lines. The agouti male was mated to NFS/NCr females at the University of Florida, and heterozygous progeny were intercrossed to generate wild type and heterozygous animals for phenotypic analyses. The pups were genotyped using tail genomic DNA (Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit; Promega).

Quantitative Real Time PCR (Q-PCR)

Q-PCR assays were run in triplicate and conducted using an Applied Biosystems 7900HT real time PCR system and included standard TaqMan gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems) for Muc19, Smgc, Lrrk2, Cntn1, Rn18s, and Hprt. To assay Muc19 pre-RNA, we used a custom TaqMan assay specific for intron 19 and exon 20. All probes were labeled with 6-carboxy-fluorescein.

For absolute quantification of assays, we prepared purified DNA templates diluted in 50 ng/μl of yeast RNA to generate standard curves from 102 to 1010 copy number/reaction versus threshold cycle (Ct), determined from fluorescence by the system SDS 2.2.1 software (Applied Biosystems). Standard curves were used to determine the amplification efficiencies (E = 10 (−1/n), where n = slope of the standard curve) in TaqMan assays as well as copy numbers of templates in experimental samples. The relative abundance of transcripts was expressed as copy number per nanogram cDNA normalized to that for the endogenous control gene. Differences in normalized values were used to determine the relative ratio or fold change of transcript expression between two conditions (see supplemental Table S8 for assays and primers).

To assay aberrant and correctly spliced transcripts near the 3′-end of Muc19, we used SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with primers designed for correctly spliced and aberrantly spliced products and for Actb as the endogenous control (see supplemental Table S9 for primer sequences and cycling conditions). The same primers were used to prepare standard templates for quantification of copy numbers per reaction. To verify that a single product was amplified, dissociation curves were generated for all reactions.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blots

Procedures were as described previously (11) with minor modifications. Samples were run on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels and stained for proteins with Coomassie Blue or stained for highly glycosylated glycoproteins with Alcian blue followed by subsequent silver enhancement. To detect Muc19 in Western blots, blots (nitrocellulose, 0.2 μm; GE Healthcare) were probed overnight at 4 °C with rabbit anti-Muc19 (1:20,000). Antibody specificity for Muc19 was recently presented (11). Novex Sharp protein standards were used.

Immunohistochemistry and Electron Microscopy

Immunohistochemistry was carried out as described previously (11) on 5-μm paraffin sections fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and probed with rabbit anti-Muc19 (1:1,000 dilution). Immunodetection was with either Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:250) or the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method (Vectastain Elite kit) with diaminobenzidine as peroxidase substrate. Electron microscopy was performed as described previously (11).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

ChIP was performed using the Tissue Epiquik ChIP kit (Epigentek Group Inc.). Briefly, eight sublingual glands or one submandibular gland from 8-week-old mice were minced and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for 25 min. The reaction was stopped with 125 mm glycine. The tissue was homogenized (Dounce; pestle A) followed by isolation of nuclei. The nuclei were lysed in the presence of protease inhibitor, and chromatin was sonicated into fragments of 200–1,000 bp using a Branson Digital Sonifier (model 250 with tapered micro-tip) with four 5-s pulses with 25-s intervals between pulses (30% amplitude level). One-twentieth of the fragmented chromatin was removed as input DNA before subsequent precipitation with either mouse IgG (negative control) or anti-Pol II. Recovered DNA from input and ChIP samples were initially assayed by conventional PCR using primers to intron 19 (5′-GGAACACGACATTTAGCGTCTCAC-3′) and exon 20 (5′-CTGGAACATGGGATGCTTTTTC-3′) to give a 227-bp product. PCR conditions were as described for genetic mapping in supplemental Table S2 but for 25 cycles. One-eighth of the recovered DNA from input, and ChIP samples were then used as template in TaqMan assays for Muc19 hnRNA (intron 19 to exon 20), and copy numbers from a standard curve were normalized as percentages of total input DNA.

RNA Stability Assay

Sublingual glands were excised from mice (7–10 weeks old) and enzymatically dispersed tubuloacini prepared using a modification of our protocol for rats (8). Glands from 10 mice were minced and incubated in 10 ml of medium containing 100 units/ml collagenase (Worthington CLSPA) and 40 units/ml hyaluronidase. Aliquots of freshly prepared and washed tubuloacini were incubated at 37 °C for 0, 1, 2, 4, or 6 h with the transcription inhibitor, 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazoleriboside (80 μm). Random primed cDNAs were assayed using TaqMan Q-PCR assays for Muc19 mRNA, Muc19 hnRNA, and 18S rRNA. Copy numbers were normalized to 18S rRNA.

RACE-PAT

We used the protocol described by Sallés et al. (22). Briefly, total RNA (50 ng) from sublingual glands was reverse transcribed in the presence of 1 mm dNTPs, avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) and 200 ng of a 3′-Adapter (5′-GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTTTTTTTTTTTT-3′) at 42 °C for 1 h. Resultant cDNA was used as template for subsequent PCRs using Accuprime high fidelity Taq DNA polymerase, the forward primer (5′-GGACCAGTGTGAACAGTCTAA-3′ specific to Muc19/Smgc exon 60 and reverse primer (5′-GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACT-3′) specific to the adapter. PCR cycling profiles were: 94 °C for 2 min followed by 39 cycles (94 °C for 30 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 60 s) and 5 min of extension at 68 °C. RACE-PAT products were resolved in 3.5% NuSieve 3:1 agarose gels.

Minigene Splicing Assay

Pre-mRNA substrate minigenes of specific genomic regions from wild type and sld mutant mice were produced and transformed into the mouse hepatoma cell line, Hepa 1–6 (ATCC). Cells were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS and transformed using Lipofectamine reagent (0.5–2 μg of DNA in 1.6 ml of medium in 6-well plates for 5 h) followed by G418 selection and sequencing to verify appropriate mouse DNA insertions. PCR of random-primed cDNA contained exon-specific primers as well as to the loading control, neomycin phosphotransferase, present in all constructs. All of the products were confirmed by direct sequencing. Primers and PCR conditions are given in supplemental Table S9.

To create minigenes encoding exons 57–58 and exons 53–55, we used as templates the previously produced and sequenced genomic clones, as indicated in supplemental Table S5, that contain exons 57–60 (HM132020 and HM132021) and exons 53–56 (HM132018 and HM132019). The primers and PCR conditions are given in supplemental Table S9. PCR products were cloned directly into pCR Topo2.1. Inserts were then excised (HindIII-XhoI for introns 52–55 and HindIII-BstXI for introns 56–58), and fragments were cloned into identical sites of expression vector pcDNA 3.1(+). The resultant plasmids were transformed into DH10b cells.

Because adequate primer pairs to exons 52 and 53 could not be developed, we produced an expression vector incorporating pEGFP-N3 (Clontech). The multiple cloning site of pEGFP-N3 from restriction sites NheI to BamHI was replaced with 99 base pairs of synthesized sequence (supplemental Table S9) containing identical terminal restriction sites, plus 60 bp from exon 3, starting from a XhoI site in the 5′-end of exon 3. A genomic clone containing Muc19/Smgc exons 1–5 (GenBankTM accession numbers HM132006; supplemental Table S5) was then used as template in a PCR with forward primer 5′-TTGCTAGCCCTAGGCGGTAAAATGGGAGTCTTTGATT-3′ and reverse primer 5-CCCAGAAGAAGAGTCCCGGTAGAATACCTCCTA-3′. The reverse primer is within intron 3. The forward primer is within exon 2 with additional 5′ sequence that adds an NheI site. This primer also includes two nucleotide mismatches (bold) to produce an efficient Kozak consensus sequence and ATG initiation site (underlined). The PCR product (748 bp) was cut with NheI and XhoI and inserted into the modified multiple cloning site of pEGFP-N3, producing pE2–3-EGFP. This plasmid produces a transcript starting from the modified ATG site in exon 2 through the 5′-end of exon 3 that is fused in frame to EGFP. To insert the genomic region from introns 52–55, we amplified this region using forward primer 5′-ATAGATCTCAAGAAGACAGGTGATCTGTGTGAGCTTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-GAAAGCTTCCGTTGCCCTTGAACCTATTGATGC-3′, each containing 5′-end BglII and HindIII restriction sites, respectively. Genomic clones HM132018 and HM132019 (supplemental Table S5) served as templates. The PCR products were cut and inserted into identical sites located within intron 2 of pE2–3-EGFP. The resultant plasmids were transformed into DH10b cells.

Pateamine A Experiments

In three separate experiments, freshly excised sublingual glands from three mutant sld mice at 8 weeks of age were finely minced into small fragments less than 1 mm3, washed thrice with PBS, and cultured for 2 h under the same conditions as enzymatically dispersed tubuloacini, as described above, except either 2 nm pateamine A (kindly provided by Dr. Jerry Pelletier) or Me2SO (vehicle control) was added. RNA was immediately extracted in TRIzol reagent and treated with DNase I, and random primed cDNAs were assayed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with primers for correctly and aberrantly spliced products as described above.

Statistics

Statistical comparisons were conducted with Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Genetic Mapping of the sld Mutation

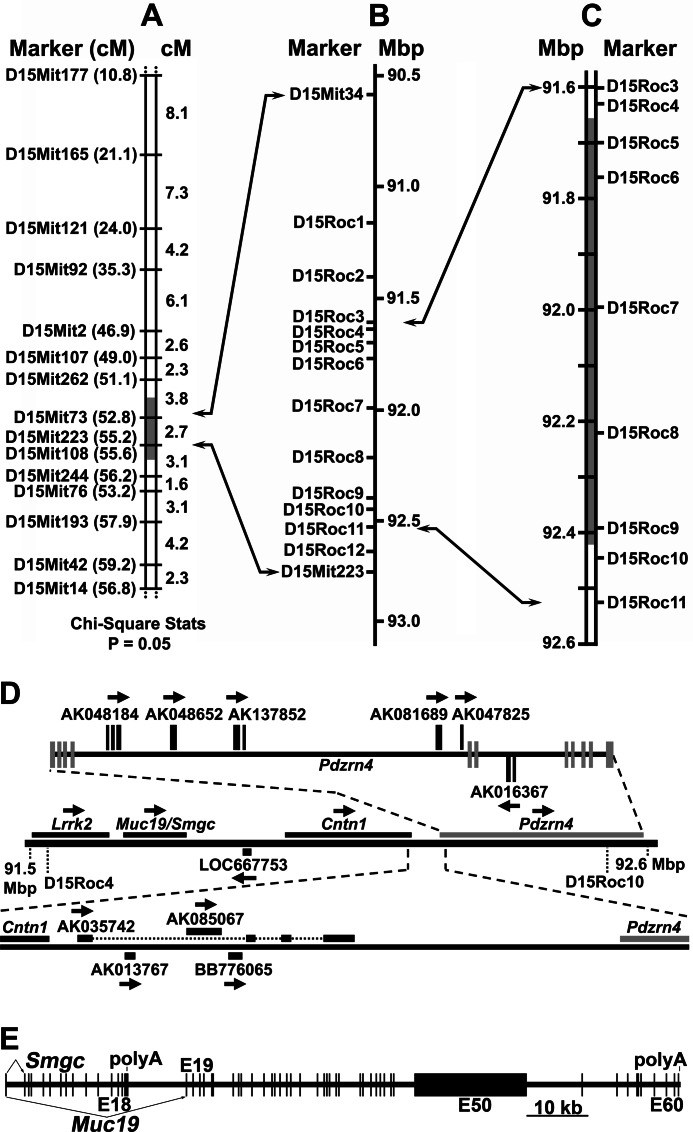

To genetically map the sld mutation, we produced 537 F2 mice from an F1 intercross of CAST/EiJ and NFS/N-sld mice. The mice were phenotyped at 3 weeks of age by the differential expression in sublingual glands of high molecular weight mucin glycoproteins, Muc19, as assessed by SDS-PAGE (see supplemental Fig. S1). Interestingly, F1 heterozygotes were indistinguishable from CAST/EiJ homozygotes (not shown). Homozygous mutants comprised 26.6% of F2 mice, consistent with an autosomal recessive mutation. We initially screened 14 mutant and 8 wild type F2 mice using 59 MIT STS markers with average spacing of 20.5 centimorgans along chromosomes 1–19. Linkage analysis using Map Manager QTX (23) indicated strong linkage to chromosome 15 but weak linkage to chromosome 6 (not shown). After assaying a total of 133 F2 mice (31 mutant and 102 wild type), the mutation was clearly linked only to chromosome 15 within a critical interval of less than 5.1 centimorgans (Fig. 1A). Screening 417 additional F2 animals further constricted the interval to between D15Mit73 and D15Mit223 (one mutant and one wild type informant). We then identified 13 additional polymorphic markers (D15Mit34 and 12 new markers, D15Roc1-D15Roc12) and subsequently fine mapped the mutation to a critical interval of ∼825 kb (Fig. 1, B and C). Each boundary is identified by two separate crossover events: two wild type phenotypes at the proximal border and one mutant and one wild type phenotype at the distal border.

FIGURE 1.

Mapping the sld mutation and Muc19/Smgc genomic organization. A, linkage analysis of 133 F2 mice (31 mutant and 102 wild type phenotypes) from an F1 intercross of Cast/EiJ and NFS/N-sld mice. The loci are listed in probable order beginning with the most proximal locus. The gray area indicates the critical interval. The positions of STS markers on chromosome 15 (in parentheses) are given in centimorgans (cM) based on the MGI genetic map. B, positions (mega-base pairs, Mbp) of STS markers on the genomic sequence of chromosome 15 (NCBI Build 36.1) used in fine mapping of the critical interval. Note that D15Mit34 is positioned 0.6 centimorgans upstream of D15Mit73 (52.2 centimorgans) on the MGI genetic map but is 3.84 mega-base pairs downstream of D15Mit73 in the genomic sequence. C, fine mapping of 537 F2 mice (143 mutants). The gray box indicates the resultant critical interval. D, transcript map of the critical interval. The middle horizontal line is the critical interval within genomic sequence with known genes (Lrrk2, Muc19/Smgc, and Cntn1), one putative gene (Pdzrn4), and a computer-predicted locus consisting of only a single open reading frame (LOC667753), for which there are no expression data. Pdzrn4 (PDZ domain containing RING finger 4) is predicted primarily on genomic alignments of multiple ESTs and from a predicted PDZ protein domain. The top horizontal line shows six ESTs localized within the Pdzrn4 domain but do not have significant overlap with exons associated with the Pdzrn4 model. Pdzrn4 exons are vertical gray bars centered on the black line. EST exons are in black above or below the line. The bottom horizontal line shows four ESTs aligned between contactin 1 (Cntn1) and Pdzrn4. Arrows indicate directions along genomic DNA that transcripts are encoded. E, exon map of mouse Muc19/Smgc. Exon 1 is shared by transcripts encoding Smgc (exons 1–18) and Muc19 (exons 1 and 19–60). Exon 50 (E50) contains ∼36 tandem repeats that encode 163 amino acid repeats rich in serine and threonine residues, sites of apoprotein O-glycosylation.

Transcripts within the Critical Interval and Differential Expression

The critical interval contains three confirmed genes (Lrrk2, Muc19/Smgc, and Cntn1), one putative gene (Pdzrn4), and a computer-predicted single open reading frame (LOC667753) (Fig. 1D). Ten representative expressed sequence tags (ESTs) without significant overlap with exons of annotated genes are also present. Of these, eight are curated as “unclassifiable” in the FANTOM3 database. Although Muc19/Smgc lies within the critical interval, we took a conservative approach and compared all transcripts for differential expression to initially distinguish the specificity of the mutation to impact expression of Muc19 transcripts. We compared transcript expression between wild type and sld mice at 3 days of age, when differences in mucous cell expression are most pronounced (15). All three known genes (Lrrk2, Muc19/Smgc, and Cntn1) are expressed in neonatal sublingual glands of both strains, whereas no expression is detected for all other transcripts in the critical region. Representative RT-PCR results are shown in supplemental Fig. S2. Of the four expressed transcripts within the critical interval, only Muc19 transcripts demonstrate significant differential expression in sublingual glands of 3-day-old sld mutant mice, with Muc19 transcripts nearly 10-fold less that in wild type mice (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Comparisons by Q-PCR of mRNAs of genes within the critical interval expressed in sublingual glands of 3-day-old wild type and sld mutant mice

The values are the means and (standard deviation) of copy numbers from eight preparations of sublingual glands normalized to Hprt1. Random-primed cDNA was quantified using the appropriate TaqMan Q-PCR assay. The ratio is expression in glands of wild type mice relative to sld mice. The p values are from Student's two-tailed t tests (unpaired).

| Transcript | Relative copy number |

Ratio (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | sld | ||

| Lrrk2 | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.11 (0.03) | 1.18 (0.63) |

| Muc19 | 114 (45) | 12 (2) | 9.50 (<0.001) |

| Smgc | 7.2 (3.4) | 4.8 (2.1) | 1.50 (0.10) |

| Cntn1 | 0.19 (0.14) | 0.24 (0.17) | 0.79 (0.5) |

In Fig. 1E is shown an exon map of Muc19/Smgc to indicate the relationship between exons encoding Smgc versus Muc19. The gene contains 60 exons spanning more than 106 kb of genomic sequence. Smgc is encoded by exons 1–18, whereas Muc19 transcripts incorporate exons 1 and 19–60 (7). Exon 1 is therefore shared between the two transcripts and encodes for most of the predicted signal peptide directing each translation product to the secretory pathway. Note that exon 50 is ∼18 kb, and its central region contains ∼36 tandem repeats of 489 bp encoding Ser/Thr-rich sequences, abundant sites of O-glycosylation (7). We established previously that expression of these two transcripts in sublingual glands is developmentally controlled, with transition from Smgc to the alternate splice variant, Muc19, during the latter stages of mucous cell cytodifferentiation (18). Expression of Smgc in neonatal sublingual glands is therefore due to glandular growth and initial cytodifferentiation of newly formed tubuloacini, and by 3 weeks of age, Smgc transcripts are barely detectable (18). As shown in Table 1, Smgc expression in neonates is not significantly different in sld mice. The sld mutation therefore specifically disrupts expression of the Muc19 splice variant of Muc19/Smgc.

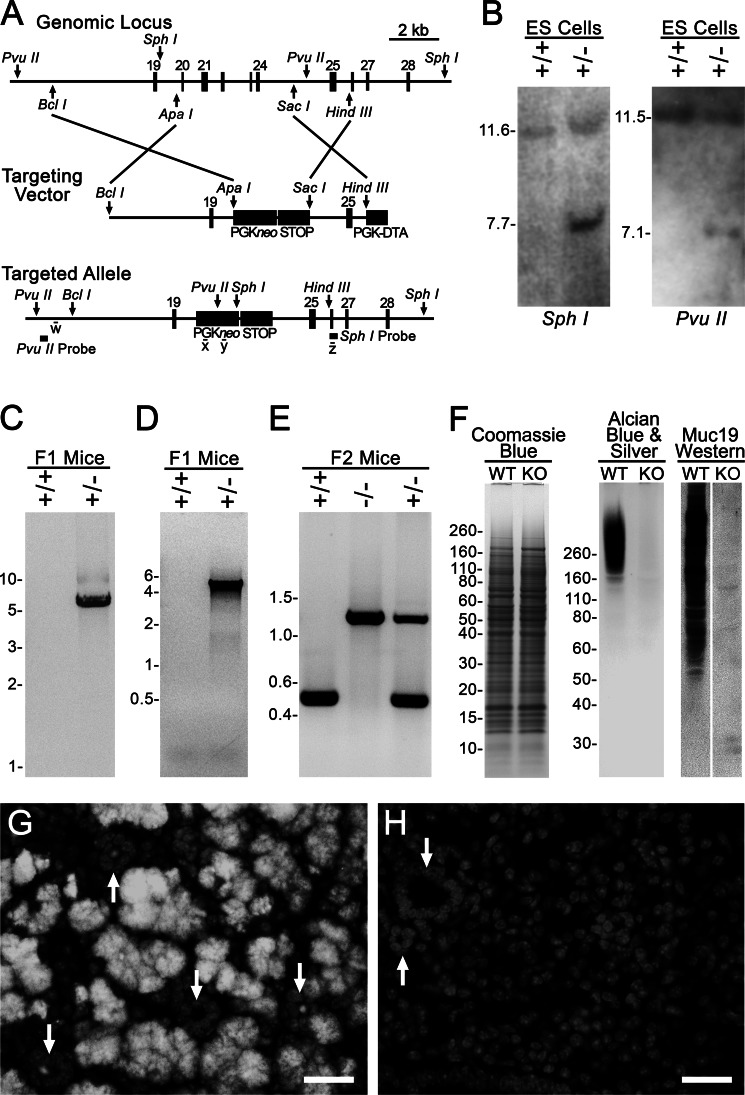

Targeted Disruption of Muc19 Expression Mimics the sld Phenotype

As further evidence that the sld mutation specifically disrupts the expression of Muc19 transcripts, we generated Muc19 knock-out mice to test whether the sld phenotype is recapitulated. We used a targeting strategy (Fig. 2A) to disrupt production of Muc19 transcripts without compromising Smgc transcripts. Genetic analyses of ES cell targeting, germ line transmission, correct insertion of F1 agouti mice, and genotyping of progeny from intercrossing F1 recombinant mice are shown in Fig. 2 (B–E). As shown in Fig. 2 (F–H), homozygous Muc19 knock-out (−/−) mice display no apparent difference in protein expression, whereas high molecular weight glycoproteins, Muc19 mucins, are undetectable in gland homogenates as well as in tissue sections.

FIGURE 2.

Production and characterization of Muc19 knock-out mice. A, strategy for targeted disruption of Muc19 transcripts from the gene Muc19/Smgc. The homology arms were inserted into the selection cassette PGKneolox2DTA that encodes for neomycin under control of the PGK promoter. The PGKneo sequence is flanked by loxP sites (not shown). The sequence from the STOP cassette, pBS302, was inserted between the downstream loxP site, and diphtheria toxin A was driven by the PGK promoter for negative selection. The targeted allele is shown with restriction sites (PvuII and SphI) and probes used for Southern blot analyses as well as sites of PCR primers w–z. B, Southern blot analyses of DNA from nonrecombinant ES cells (+/+) and correctly targeted ES cells (+/−) digested with SphI and with PvuII. C, PCR-based genotyping of F1 agouti mice to distinguish the absence (+/+) or presence (+/−) of germ line transmission and correct insertion of the 3′-end of the targeted allele using primers w and x (as shown in A). D, same as in C, but using primers y and z to detect germ line transmission and correct insertion of the 5′-end of the targeted allele. E, genotyping of progeny from intercrossing F1 recombinant mice. F, sublingual gland homogenates (wet weight, 200 μg) from wild type (WT) and homozygous Muc19 knock-out (KO) mice were subjected to SDS-PAGE (4–12% gel) and stained with Coomassie Blue to detect proteins. Homogenates (wet weight, 300 μg) were also run on a 4–12% gel and either stained with Alcian blue and subsequent silver enhancement to detect highly glycosylated glycoproteins or identical lanes blotted and probed with rabbit anti-Muc19. G and H, anti-Muc19 immunofluorescence. G, low power micrograph of a paraffin section from a 3-day-old wild type mouse probed with rabbit anti-Muc19 and Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG displaying Muc19 in mucous cells of tubuloacini. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (light gray). Arrows indicate cross-sectioned ducts, most of which contain Muc19 within their lumen. H, section from a 3-day-old Muc19 KO mouse processed in an identical manner displays an absence of Muc19 immunostaining. Only DAPI staining is visible. The arrows indicate cross-sectioned ducts. Bars, 25 μm.

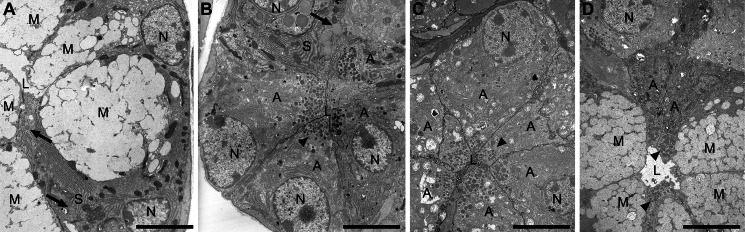

In wild type sublingual glands, mucous cells contain an expansive cytoplasm packed with large electron-lucent secretion granules, whereas RER, Golgi, and mitochondria are confined basally near the nucleus and lateral cytoplasmic regions (Fig. 3A). In Muc19 KO mice, the absence of Muc19 expression results in mucous cells with small moderately electron-dense apical granules (Fig. 3B). The cytoplasm is much less organized with a large round nucleus surrounded by loosely arranged RER and associated Golgi. These are all features of “atypical” cells in sld glands (Fig. 3C) as identified previously (15). Serous demilune cells of Muc19 knock-out mice appear mostly unchanged, with multiple layers of tightly arrayed RER and secretion granules that are less electron-dense and larger than those of atypical mucous cells (Fig. 3, A and B). Groups of cells expressing the mucous cell phenotype are apparent in sld mice at 8 weeks of age, although their exocrine granules are more electron-dense and smaller than in wild type mucous cells (Fig. 3D). Atypical cells can be seen in juxtaposition to the mucous cells.

FIGURE 3.

Ultrastructural comparisons between sublingual glands of wild type, Muc19 knock-out, and sld adult mice. A, transmission electron microscopy of WT sublingual gland with typical mucous cell ultrastructure (M), including an expansive cytoplasm filled with large electron lucent secretory granules, a basal nucleus (N). Golgi and mitochondria are localized near the nucleus and lateral aspects of the central region. A serous demilune cell (S) projects an apical cytoplasmic extension between two mucous cells to meet the lumen (L). Present within the cell projection are abundant RER and a couple of slightly electron-dense secretion granules (arrows). B, transmission electron microscopy of sublingual gland from Muc19 KO mouse. A serous demilune cell (S) with normal features is present, including slightly electron-dense secretion granules (arrow). Most cells are of atypical appearance (A) and contain small moderately electron-dense granules (arrowhead) concentrated within the apical cytoplasm near the lumen (L). The cytoplasm is much less organized with a large round nucleus (N) and loosely arranged RER and associated Golgi complexes. C, transmission electron microscopy of atypical mucous cells (A) within a tubuloacinus of an sld sublingual gland. These cells display the same features as mucous cells in the Muc19 KO, including small moderately electron-dense granules (arrowhead) near the lumen (L). D, transmission electron microscopy of a tubuloacinus of an adult sld sublingual gland with atypical cells (A) juxtaposed to a group of cells expressing a mucous cell phenotype (M). Note that the exocrine granules (arrowheads) of these cells appear smaller and more electron-dense than granules in wild type mucous cells (panel A). N, nucleus; L, lumen. Scale bars, 4 μm.

The sld Defect Does Not Alter the Rate of Muc19/Smgc Gene Transcription

Because the coding region of Muc19/Smgc encompasses such a large stretch of genomic sequence, we first investigated the process by which steady-state levels of Muc19 transcripts are attenuated in sld mice to potentially localize and restrict subsequent sequencing efforts. Previously, we established that Muc19 pre-RNA and mRNA increased nearly 4-fold from birth to 8 weeks of age (18). We therefore hypothesized the sld genetic defect disrupts a putative transcriptional regulatory site in the 5′-flanking region of Muc19/Smgc to attenuate gene transcription throughout gland development and maturation. As shown in Table 2, Muc19 pre-mRNA levels in sublingual glands are not significantly different between wild type and sld neonatal mice at either 3 days or 8 weeks of age, even though pre-mRNA levels increase markedly over this time frame. Coinciding with the postnatal increase in pre-mRNA is an increase in steady-state Muc19 mRNA levels. Whereas mRNA levels are 10-fold less in sld neonates, levels are ∼3-fold less at 8 weeks of age (Table 2), consistent with the appearance of a subpopulation of Muc19-containing mucous cells at 8 weeks, as described above.

TABLE 2.

Comparative expression of Muc19 RNA species in sublingual, submandibular, and bulbourethral glands of wild type and sld mutant mice at different ages

The values are the means and (standard deviation) of copy numbers, from n preparations of glands, normalized to Hprt1. Random-primed cDNA was quantified using the appropriate TaqMan Q-PCR assay. The ratio is expression in glands of wild type mice relative to sld mice. The p values are from Student's two-tailed t test (unpaired). ND, not determined.

| Age | Gland | Muc19 RNA | Normalized expression |

Ratio (p value) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | sld | ||||

| 3 days | Sublingual (n = 8) | mRNA | 114 (45) | 12 (2) | 9.50 (<0.001) |

| Pre-RNA | 2.6 (1.7) | 4.3 (2.6) | 0.60 (0.14) | ||

| Submandibular (n = 7) | mRNA | 1.7 (1.1) | 0.38 (0.30) | 4.47 (0.01) | |

| Pre-RNA | ND | ND | ND | ||

| 8 weeks | Sublingual (n = 6) | mRNA | 594 (49) | 181 (89) | 3.28 (<0.0001) |

| Pre-RNA | 25 (6) | 30 (5) | 0.83 (0.11) | ||

| Bulbourethral (n = 4) | mRNA | 6.3 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.4) | 2.62 (0.01) | |

| Pre-RNA | 0.24 (0.03) | 0.27 (0.06) | 0.89 (0.52) | ||

Also shown in Table 2 are results for 3-day-old submandibular salivary glands and 8-week-old bulbourethral glands. Bulbourethral glands express transcripts for Muc19 in addition to Muc5b (11). Neonatal submandibular glands are poorly developed, and some cells transiently express very low levels of Muc19, although upon final postnatal differentiation, acinar cells express and secrete the small mucin, Muc10 (18). From Table 2 it is apparent that both glandular tissues in sld mice express lower levels of Muc19 mRNA than in wild type mice and at levels approximately proportionate to those in sublingual glands at the same age. The disruption of Muc19 expression associated with the sld mutation is therefore not selective for sublingual glands.

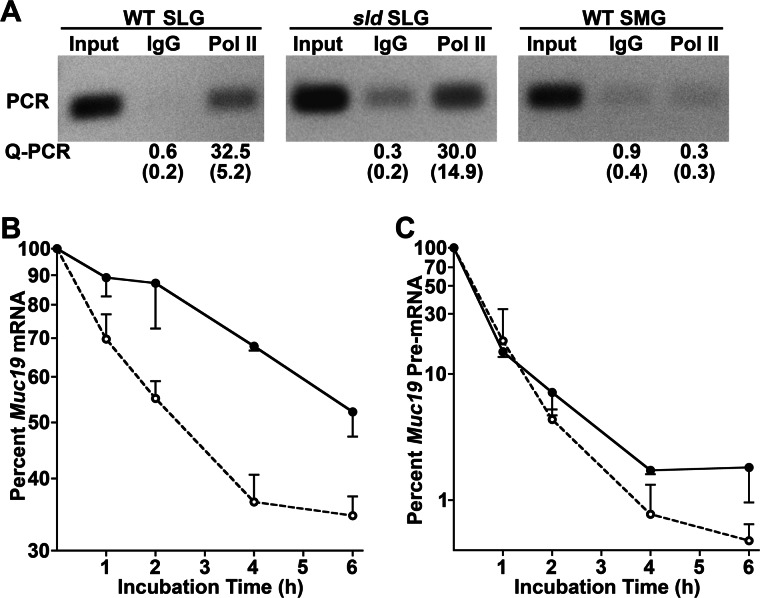

As another indicator of the rate of Muc19 transcription, we assessed RNA Pol II densities by ChIP, targeting the region from intron 19 to exon 20 of Muc19 pre-mRNA using standard PCR as well as a custom TaqMan assay. As shown in Fig. 4A, Pol II density along this 5′ segment of the Muc19 coding region is equivalent in adult sublingual glands from both strains of mice. In addition to assessing Muc19 transcription, we cloned and sequenced 7.7 kb of Muc19/Smgc 5′-flanking sequence from both sld and wild type mice but found no sequence variations (GenBankTM accession number HM132005). Collective results therefore argue against the sld mutation disrupting Muc19 transcription.

FIGURE 4.

Comparisons of Muc19 transcription and mRNA stability between wild type and sld mutant mice. A, Muc19 transcription in sublingual glands (SLG) of WT and sld mutant adult mice determined by Pol II density. Samples of recovered genomic DNA from anti-Pol II ChIP, either the input fragmented DNA (Input), DNA immunoprecipitated by anti-Pol II, or by the negative control, IgG, were assayed by PCR for a short genomic region spanning Muc19/Smgc intron 19 and exon 20. DNA was also assayed by Q-PCR using a TaqMan assay, and the results are expressed as the means and S.E. of copy numbers as percentages of total input DNA. The results are from three separate experiments. Submandibular glands (SMG) from adult wild type mice (tissue negative control) demonstrated no significant transcriptional activity. B and C, stability of Muc19 mRNA (B) and pre-mRNA (C) transcripts in sublingual tubuloacinar structures isolated from WT and sld adult mice. Aliquots of isolated tubuloacini were incubated at 37 °C for increasing time periods with the transcription inhibitor, 5,6-dichlorobenzimidazoleriboside (80 μm). Transcripts were quantified by Q-PCR, and copy numbers were normalized to 18 S RNA. The values are the means (± S.D. or range) for two WT (closed circles) and three sld (open circles) acinar preparations, expressed as the percentage at time 0. Half-lives were determined from linear regressions (r2 = 0.93–0.98) of the curves, using points that reflect the initial decay rate (0–4 h or 0–6 h). Calculated mRNA half-lives are 6.7 h (WT) and 2.5 h (sld); pre-mRNA half-lives are 0.48 h (WT) and 0.42 h (sld).

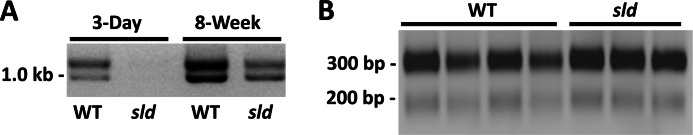

The sld Mutation Decreases Muc19 Message Stability

Because the rate of Muc19 transcription is equivalent in both strains of mice, we compared the stability of Muc19 mRNA in enzymatically dispersed sublingual tubuloacini from 8-week-old sld and wild type mice. The half-life of Muc19 mRNA is ∼3-fold less in sld mice, whereas Muc19 pre-mRNA is not affected by the sld mutation (Fig. 4, B and C). Decreased mRNA stability may be mediated by a number of mechanisms including changes in 3′-end processing (cleavage and polyadenylation) and subsequent nuclear export (24). Because Muc19 transcripts can incorporate one of two polyadenylation sites within the 3′-UTR (6), mutation within a cis-element controlling polyadenylation may alter either site usage and/or the efficiency of the polyadenylation machinery to effect nuclear export or the extent of polyadenylation. We therefore compared poly(A) site utilization between wild type and sld mice by 3′-RLM RACE. As shown in Fig. 5A, wild type neonates and adults of both strains use both poly(A) sites. Consistent with the low levels of Muc19 mRNA in sld neonates, 3′-RLM RACE products are barely detectable in 3-day-old sld glands. The 3′-RLM RACE products from adult wild type and sld mice were cloned and sequenced. There were no differences in the 3′-UTR sequences between the two strains of mice (not shown; GenBank accession numbers HM132025 and HM132026). Moreover, we compared poly(A) tail length of Muc19 transcripts in adult glandular RNA by RACE-PAT (22) and further found no significant differences (Fig. 5B), although the downstream polyadenylation site appears more extensively utilized.

FIGURE 5.

Comparisons of 3′-end processing of Muc19 transcripts between WT and sld mutant mice. A, polyadenylation site utilization between WT and sld mice at 3 days and 8 weeks of age by 3′-RLM RACE. PCR of ligated cDNA produced two products that differ by ∼100 bp, indicating that both polyadenylation sites are utilized by both strains of mice. The transcript levels in sld neonates are too low for detection. B, RACE-PAT to compare poly(A) tail length of Muc19 transcripts. Sublingual total RNA from four WT and three sld glands from mice at 8 weeks of age was reverse transcribed with a 44-bp primer/adapter containing 11 thymines at the 3′-end. Subsequent PCR of the cDNA incorporated a Muc19-specific forward primer 103 bp 5′ to the first polyadenylation site and a reverse primer to the 5′-end of the primer/adapter. The prominent band at ∼300 bp suggests that the downstream polyadenylation site is utilized more extensively.

Previously we reported the sequence for Muc19 cDNA from wild type NFS/NCr mice (GenBankTM accession number AY570293) (7). We also demonstrated Muc19 mRNA transcripts of both strains of mice are of similar size (∼22 kb) in Northern blots and that mucin glycoproteins display similar, albeit extremely slow, electrophoretic mobility (15). Synthesis of mucin glycoproteins of similar mobilities argues against a defect within the Muc19 coding sequence that creates solely nonsense or transcripts truncated prior to the large central exon 50, which contains nearly all predicted sites of O-glycosylation. Alternatively, the Muc19 coding sequence may contain a mutation proximal to a splice site or within the binding motif of an exon splicing enhancer/silencer that may lower splicing efficiency and through exon skipping produce a frameshift resulting in a subpopulation of transcripts with one or more premature stop codons. We therefore compared Muc19 cDNA sequences between the two strains of mice. Sequence of the 5′-end of mutant NFS/N-sld mice cDNA was derived from three overlapping clones covering from exon 1 through the nonrepetitive 5′-end region of exon 50 (GenBankTM accession numbers HM132022, HM132023, and HM132024). The sequence of the 3′-end of Muc19 cDNA, from the nonrepetitive 3′-end of exon 50 through the 3′-UTRs, was derived from the cloned 3′-RLM RACE products described above. Note that the tandem repeats within the central region of exon 50 were characterized originally by Southern blot of a partial restriction digest and are intractable to both cloning and sequencing (7). Collectively, we found no sequence differences in Muc19 cDNA between wild type and mutant mice.

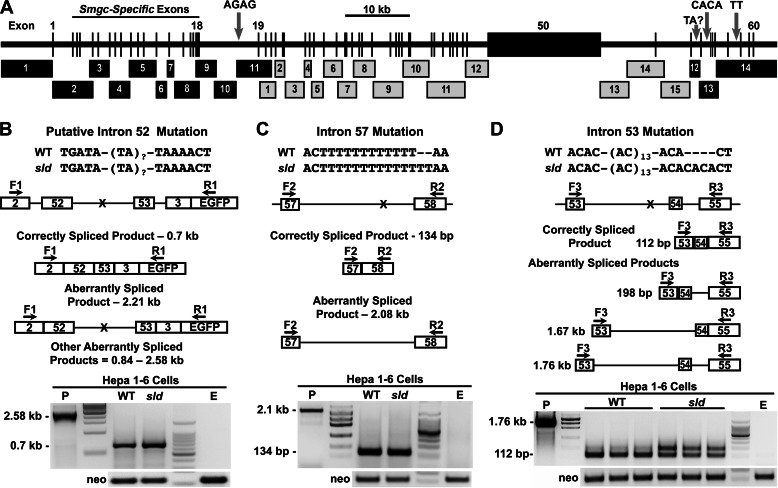

Comparative Sequencing of the Muc19/Smgc Genomic Coding Region

At this stage, we suspected the mutation is within an intron that either disrupts a commonly used splice site or creates an alternative splice site to produce aberrant transcripts. We therefore sequenced the coding region (106 kb) of Muc19/Smgc in both strains of mice, except for the repetitive central region of exon 50. We identified four candidate mutations, each within introns (Fig. 6A). These mutations include three sites within the 3′-end of the gene: an insertion of two CA repeats within intron 53, insertion of two T residues within intron 57, and a putative site within intron 52. The site within intron 52 represents a TA repeat region that was intractable to sequencing of either PCR amplicons or cloned PCR products. Hence, we consider the TA repeat length a candidate mutation. The fourth mutation is an insertion of two GA repeats within intron 18 at ∼2.7 kb upstream of exon 19. Note that intron 18 is ∼9 kb in length and separates exons 2–18 used for Smgc transcripts from exons 19–60 that are incorporated into Muc19 transcripts (Fig. 1E).

FIGURE 6.

Map of genomic sequencing strategy, resultant sequence variations and minigene splicing assays of the 3′-end mutations. A, genomic sequencing of Muc19/Smgc incorporated either cloned PCR products (black numbered boxes) or PCR products (gray numbered boxes). See “Experimental Procedures” for details. Three insertion mutations in introns 18, 53, and 57 are indicated by gray arrows. Because we were unable to sequence through TA repeats within intron 52, we label this region as a potential mutation site with unknown TA repeats. The central region of exon 50 is intractable to both cloning and sequencing because its central region contains ∼36 tandem repeats of 489 bp that encode Ser/Thr-rich sequences. B–D, minigene splicing assays of the 3′-end mutations. In each panel is shown the sequence variation between WT and sld mutant mice. Underneath is a map of the genomic sequence inserted into each minigene, along with positions of each sequence variation (X) and of forward (F) and reverse (R) primers used in subsequent PCRs of cDNA isolated from transfected Hepa 1–6 cells. Below each genomic map are analogous maps of correctly spliced products and of potential aberrantly spliced products. At the bottom of each panel are assay results, representative of at least two separate experiments with neo loading controls, an empty vector control (E) and a positive control (P) using DNA from the appropriate minigene. B and C, cells transfected with minigene DNA containing either intron 52 or 57 from each mouse genotype produced only a single PCR product representing the correctly spliced RNA. D, three preparations of cells transfected with 2 μg of minigene DNA from each genotype containing intron 53 displayed two products: the 112-bp correctly spliced product and a 198-bp aberrant product containing intron 54. The unmarked lanes show molecular size markers. The maps are not drawn to scale.

Interrogating Mutations for Disruption of Splicing

We first evaluated the effects of the three 3′-end mutations in splicing of surrounding exons using minigene splicing assays in the murine epithelial cell line, Hepa 1–6 cells. Assays involved the use of minigenes containing specific exons bordering the introns of interest. The 5′-end mutation in intron 18 is not amenable to these assays given the length of the intron and was therefore not tested in Hepa 1–6 cells. For minigenes that contain either intron 52 (Fig. 6B) or 57 (Fig. 6C), we find only a single RT-PCR product, each representing correctly spliced RNA. To test the mutation in intron 53, we incorporated the additional downstream sequence of exon 55 in the minigenes because exons 53 (30 bp) and 54 (32 bp) proved too short to design working primer pairs. Interestingly, both wild type and mutant minigenes each produced two products, a 112-bp product representing correct RNA splicing and an aberrant 198-bp product containing intron 54 (Fig. 6D). However, the aberrant product is much more prevalent in the minigene samples with the intron 53 mutation compared with wild type sequence.

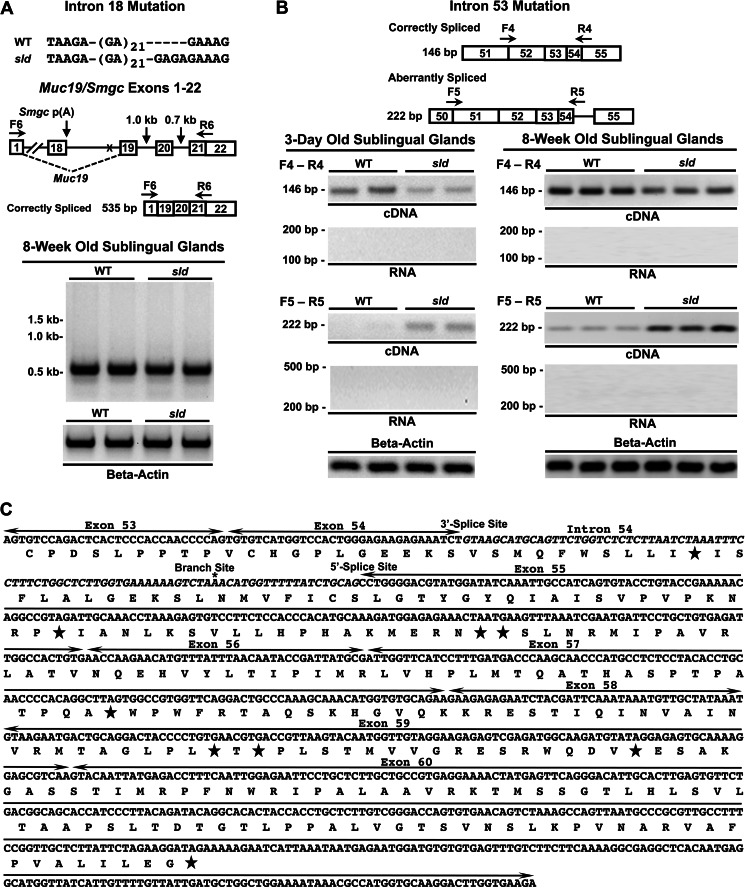

To determine whether the mutation in intron 18 affects the splicing of downstream exons 19 and 20, we tested cDNA from sublingual glands of 8-week-old mice using a forward primer in exon 1 and a reverse primer overlapping exons 21 and 22. As shown in Fig. 7A, only the correctly spliced 5′-region of Muc19 mRNA was amplified with no evidence of alternative splicing.

FIGURE 7.

Interrogation of aberrant splicing of sublingual gland Muc19 mRNA caused by intron 18 or intron 53 mutations. A, shown is the sequence variation in intron 18 between WT and sld mutant mice. Underneath is a map of the genomic sequence with positions of the sequence variation (X) of forward (F) and reverse (R) primers and the length of intervening introns. PCR of two separate preparations of cDNA from each mouse strain detected only correctly spliced products. β-Actin loading controls shown below. The maps are not drawn to scale. B, primer-specific detection of correctly and aberrantly spliced transcripts in WT and sld cDNAs from 3-day-old and 8-week-old mice. Shown are the positions of transcript-specific forward (F) and reverse (R) primers. Below are PCR results using glandular cDNA from each strain of mice, as well as RNA negative controls and β-actin loading controls. The maps are not drawn to scale. C, annotated sequence of the 3′-end of mutant Muc19 mRNA starting from exon 53. Exons are labeled and demarcated by lines with arrows. Intron 54 is in italics, and the splice sites and branch site sequence are labeled. *, putative branch point. The predicted translation sequence is given below the message sequence, with stars indicating stop codons.

Comparison of Aberrant Splicing in Sublingual Glands

In light of aberrant splicing of intron 54, we probed cDNA from sublingual glands of 3-day-old and 8-week-old mice using primers to specifically amplify either the correctly or aberrantly spliced transcripts. Consistent with minigene splicing assays, aberrant transcripts are amplified in both strains of mice at 8 weeks of age but are more abundant in glands from sld mice (Fig. 7B). Aberrant transcripts in 3-day-old mice are only detected readily in sld mice. Correspondingly, correctly spliced transcripts are reduced in sld mice at both ages. Retention of intron 54 incorporates an in-frame premature termination codon within intron 54, as well as a frameshift in exon 55 that is predicted to produce many additional termination codons that are upstream of the junction between exons 55 and 56 (Fig. 7C).

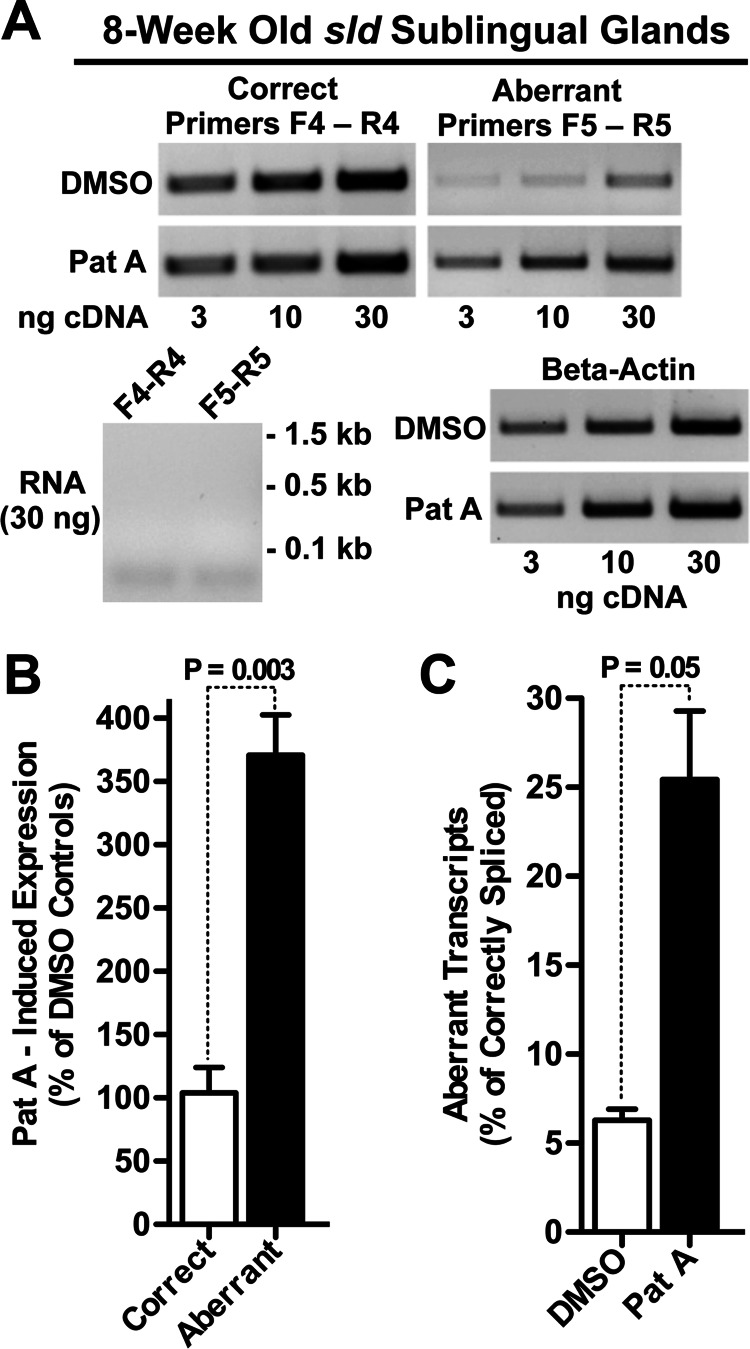

Pateamine A Inhibits Degradation of Aberrant Transcripts in Sublingual Glands of sld Mice

Aberrant Muc19 mRNA with downstream premature termination codons might serve as a substrate for degradation by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) (25) and thus account for the decrease in message stability. We therefore hypothesized that inhibition of NMD would result in increased levels of aberrant message with little change in correctly spliced Muc19 mRNA. To test this hypothesis, we incubated minced fragments from 8-week-old sld sublingual glands with pateamine A, a selective inhibitor of NMD through its direct interaction and stimulation of eIF4AIII, one of the core proteins of the exon junction complex, and indirectly via inhibition of eIF4AI/II-mediated translation initiation (26). As shown in Fig. 8A, incubation with pateamine A for 2 h increases aberrant transcripts compared with the vehicle control (Me2SO), whereas correctly spliced transcripts appear unchanged. In three separate preparations of fragments from sld mutant glands of mice at 8 weeks of age, we quantified correctly and aberrantly spliced transcripts by Q-PCR. Pateamine A has little effect on the average level of correctly spliced transcripts, whereas aberrant transcripts are induced nearly 4-fold (Fig. 8B). We also compared the levels of aberrant transcripts relative to correctly spliced transcripts after incubation with either pateamine A or Me2SO. In Me2SO, expression of aberrant transcripts is only 6.7% of that for correctly spliced transcripts but increases to 25% with pateamine A (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Effects of pateamine A on expression of aberrant and correctly spliced Muc19 transcripts. A, minced fragments of sublingual glands from 8-week-old sld mice were incubated in 2 nm pateamine A (Pat A) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, vehicle controls) for 2 h. PCR of increasing amounts of random primed cDNAs using primers specific for correctly and aberrantly sliced transcripts demonstrate pateamine A increases aberrant message compared with dimethyl sulfoxide controls, whereas correctly spliced message appeared mostly unchanged. Shown are RNA negative controls and β-actin loading controls. B, random primed cDNAs (10 ng) from three separate preparations of fragments were assayed by Q-PCR for correctly and aberrantly spliced transcripts, and copy numbers were normalized to β-actin. The results were then evaluated for expression of transcripts induced by pateamine A as a percentage of dimethyl sulfoxide controls. The p values were from Student's two-tailed t test (unpaired). C, results from the experiment in B were further evaluated for expression of aberrant transcripts as a percentage of correctly spliced transcripts under each condition. p value, Student's two-tailed t test (unpaired).

DISCUSSION

Evidence Supports That the Mutation in Intron 53 Is Responsible for Decreased Muc19 mRNA Stability

To delineate the sld genetic defect, we first localized the mutation within a critical interval containing Lrrk2, Muc19/Smgc Cntn1, and Pdzrn4. This genomic region evidently contains genes selective for neural cell types, because Cntn1 encodes the axonal adhesion molecule F3 glycoprotein (27), Lrrk2 is implicated in several age-related neurodegenerative disorders (28), and transcripts associated with Pdzrn4 are expressed in brain but not in sublingual glands. The relatively low levels of expression of Lrrk2 and Cntn1 in sublingual glands may thus be due to their association with endogenous neural elements of the autonomic nervous system.

Collective results in addition to genetic mapping indicate that disruption of Muc19 expression is related directly to a defect in the Muc19 coding region. First, we find features of cell ultrastructure consistent with the absence of Muc19 mucin glycoproteins in Muc19 KO mice, and in previous results we found expression of other sublingual secretory proteins were unaltered in sld mice (15). Second, specificity of the mutation in disrupting Muc19 expression is demonstrated in Muc19 KO mice, in which mucous cells mimic atypical cells of sld mice. Also, we find attenuation of Muc19 transcripts without a significant effect on the expression of transcripts for the splice variant, Smgc. Third, the functional effect of the mutation on Muc19 expression is not due to effects on Muc19 transcription, but instead it decreases Muc19 mRNA stability without altering the 3′-end processing of Muc19 transcripts. Comparative sequencing of the Muc19/Smgc gene identified just four candidate mutations, all within introns of the Muc19 coding region. Only the mutation in intron 53 affects splicing of Muc19 pre-mRNA. Surprisingly, insertion within the sld genomic sequence of two additional CA repeats in intron 53 results in retention of intron 54 during splicing. The effect on splicing is not absolute, because correctly spliced transcripts can be detected in sld neonates, albeit at very low levels, whereas Muc19 glycoproteins are undetectable in mutant neonates (15). The mutation therefore alters the splicing machinery to enhance aberrant splicing within the 3′-end of the ∼110-kb pre-mRNA. Retention of intron 54 and subsequent correct splicing of downstream exons will result in transcripts with multiple premature termination codons, prime substrates for degradation by NMD (25). We demonstrate that pateamine A markedly increases aberrant transcripts in mutant glands, indicating that the aberrant message is degraded, consistent with a role for NMD in message degradation (26). These results further indicate that steady-state levels of aberrant transcripts detected by RT-PCR underestimate the proportion of aberrantly spliced transcripts compared with those spliced correctly. Based on our collective results, we propose that the increase in aberrant transcripts induced by the mutation in intron 53 accounts for the sld phenotype by decreasing the stability of large Muc19 transcripts (i.e., ∼22 kb) to result in 10-fold lower steady-state levels of Muc19 mRNA in sld mice at 3 days of age.

Postnatal Changes in Muc19 Expression in Relation to the sld Phenotype

In a previous study of Muc19 expression in wild type mice during sublingual gland development (18), we found Muc19 glycoproteins increased linearly ∼7-fold from postnatal days 0–21, but with only minor changes in Muc19 pre-mRNA or mRNA. These results point toward a progressive early postnatal enhancement of the translational processing of Muc19 mRNA. With further postnatal development (i.e., postnatal days 21–28), a period during weaning and conversion to a solid diet, Muc19 pre-RNA and mRNA increased nearly 4-fold (18). The increase in transcripts upon weaning may be in response to increased activity of the reflex pathways that exist between receptors of taste and mastication with cholinergic axons innervating mucous cells. Heightened cholinergic reflex pathways may then increase Muc19 mRNA expression as reported for cholinergic agonists (29). Consistent with the postnatal increase in Muc19 pre-mRNA levels, we herein demonstrated that Muc19 pre-mRNA levels in sld mice increase more than 6-fold from 3 days to 8 weeks of age. Because the effect of the intron 53 mutation on pre-mRNA splicing is not absolute, Muc19 mRNA levels also increase and, when combined with enhanced translational processing, account for the previously observed postnatal appearance of Muc19 glycoproteins in mutant glands at 8 weeks of age, although at levels significantly less than the wild type (15).

Why Two Mucous Cell Phenotypes in Adult Mutant Glands?

Despite an attenuated increase in expression of Muc19 glycoproteins in mutant glands with age, only a subpopulation of mucous cells is able to express Muc19 glycoproteins, whereas atypical cells without mucin expression predominate, even at 1 year of age (15, 18). One would instead expect all mucous cells in mutant glands to express lower but equivalent levels of mucins. We posit that the disparity in cell expression of Muc19 glycoproteins is related, in part, to the pattern of innervation of mucous cells. Glandular cholinergic axons have numerous unmyelinated neuroeffector sites interspersed among mucous cells (30, 31) that may release cholinergic neurotransmitter intermittently at different neuroeffector sites (31). Unequal cholinergic innervation of cells may result in subpopulations of mucous cells that vary in Muc19 transcription and pre-mRNA. Additionally, aberrant transcripts may hinder processing of correctly spliced transcripts to further promote the atypical cell type in mutant glands. For example, intron retention in yeast retards nuclear export of message (32). Delayed nuclear export of aberrant Muc19 transcripts may thus hinder export of correctly spliced transcripts. A proportion of aberrant transcripts may initially escape degradation, because of NMD not being 100% efficient (33) or because of overloading of the degradation pathway by enhanced aberrant splicing of the abundantly expressed pre-mRNAs. Aberrant transcripts escaping degradation may then alter targeting of correctly spliced transcripts to the RER. The atypical cell type may therefore be unable to produce Muc19 glycoproteins because of lower levels of transcription in combination with aberrant transcripts attenuating the processing of correctly spliced transcripts. Further investigations are required to delineate the mechanisms responsible for two populations of mucous cells and may provide new insights into negative effects of aberrant transcripts in the processing of correctly spliced transcripts. Nevertheless, detection of aberrant transcripts in wild type adult mice support the importance of surveillance systems, such as NMD, in apparently healthy cells to protect against potentially deleterious gene products.

Mechanism of Intron 54 Retention

Statistical analyses of retained introns suggest that multiple sequence elements are associated with intron retention. In particular, there is an apparent bias toward retention of introns with short sequence (i.e., 75–150 nucleotides), with splice sites that conform poorly to consensus sequences, and of introns associated with highly expressed genes (34–36). Muc19 is highly expressed in sublingual mucous cells, and intron 54 is only 86 nucleotides, consistent with intron retention in other systems. More intriguing is the novel retention of a downstream intron caused by the insertion of two additional CA repeats within the immediate upstream intron. Intronic CA repeats positioned proximal to the 5′ splice site were shown to enhance splicing, whereas when positioned more downstream within an intron, they promote intron retention (37). The regulatory functions of CA repeat regions may be mediated by the binding of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins, hnRNP L (38, 39). As the number of CA repeats is expanded, both the level of bound hnRNP L and the efficiency of its splicing regulatory function are increased (38). hnRNP L can interact with exonic silencer elements to block spliceosome assembly even after formation of the spliceosomal A complex (40). In light of the known effects of hnRNP L on splicing, we speculate that it may mediate the splicing defect associated with two additional CA repeats within intron 53. Additional repeats may add hnRNP L binding sites or increase its affinity. Because the 5′ splice site of exon 54 and the 3′ splice site of exon 55 lie in very close proximity to the CA repeat region (217 and 303 nucleotides downstream, respectively), an increase in the association of hnRNP L may allow this domain to further antagonize subsequent assembly of spliceosomal components at the 5′ splice site of exon 54. Increased hnRNP L may interfere with 5′ splice site recognition by reducing U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein binding at the 5′ splice site and/or the subsequent interaction between the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein-containing complex with the U2 auxiliary factor complex at the 3′ splice site of exon 55 (41–44). Testing this putative model in future investigations of the mechanism through which the mutation in intron 53 affects splicing may thus shed additional light on the functions of hnRNP L proteins and/or of other splicing proteins. Furthermore, a regulatory role for CA repeats is of special interest given they represent the most frequent simple repeat sequence motif in the human genome (45).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally Chuang, Shirley Markant, Ashley Grillo, Brian Boesch, Sara Shah, Jillian Rose, David Serwanski, and Maya Yankova for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DE014730 and DE016509 (to D. J. C.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S9 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- STS

- sequence tagged site

- Pol II

- RNA polymerase II

- poly(A)

- polyadenylation

- NMD

- nonsense-mediated mRNA decay

- hnRNP

- heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins

- Q-PCR

- quantitative real time PCR

- contig

- group of overlapping clones

- PGK

- phosphoglycerate kinase

- RACE

- rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- PAT

- poly(A) test

- EST

- expressed sequenced tag

- RER

- rough endoplasmic reticulum.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hattrup C. L., Gendler S. J. (2008) Structure and function of the cell surface (tethered) mucins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 70, 431–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rose M. C., Voynow J. A. (2006) Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 86, 245–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tabak L. A. (1995) In defense of the oral cavity. Structure, biosynthesis, and function of salivary mucins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 57, 547–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Nieuw Amerongen A., Bolscher J. G., Veerman E. C. (2004) Salivary proteins. Protective and diagnostic value in cariology? Caries Res. 38, 247–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sonesson M., Wickström C., Kinnby B., Ericson D., Matsson L. (2008) Mucins MUC5B and MUC7 in minor salivary gland secretion of children and adults. Arch. Oral. Biol. 53, 523–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Y., Zhao Y. H., Kalaslavadi T. B., Hamati E., Nehrke K., Le A. D., Ann D. K., Wu R. (2004) Genome-wide search and identification of a novel gel-forming mucin MUC19/Muc19 in glandular tissues. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 30, 155–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Culp D. J., Latchney L. R., Fallon M. A., Denny P. A., Denny P. C., Couwenhoven R. I., Chuang S. (2004) The gene encoding mouse Muc19. cDNA, genomic organization and relationship to Smgc. Physiol. Genomics 19, 303–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Culp D. J., Luo W., Richardson L. A., Watson G. E., Latchney L. R. (1996) Both M1 and M3 receptors regulate exocrine secretion by mucous acini. Am. J. Physiol. 271, C1963–1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Culp D. J., Zhang Z., Evans R. L. (2011) Role of calcium and PKC in salivary mucous cell exocrine secretion. J. Dent. Res. 90, 1469–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luo W., Latchney L. R., Culp D. J. (2001) G protein coupling to M1 and M3 muscarinic receptors in sublingual glands. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C884–C896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Das B., Cash M. N., Hand A. R., Shivazad A., Grieshaber S. S., Robinson B., Culp D. J. (2010) Tissue distibution of murine muc19/smgc gene products. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 58, 141–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bhide S. A., Miah A. B., Harrington K. J., Newbold K. L., Nutting C. M. (2009) Radiation-induced xerostomia. Pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. Clin. Oncol. (R. Coll. Radiol.) 21, 737–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chiorini J. A., Cihakova D., Ouellette C. E., Caturegli P. (2009) Sjogren syndrome. Advances in the pathogenesis from animal models. J. Autoimmun. 33, 190–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Culp D. J., Latchney L. R. (1993) Mucinlike glycoproteins from cat tracheal gland cells in primary culture. Am. J. Physiol. 265, L260–L269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fallon M. A., Latchney L. R., Hand A. R., Johar A., Denny P. A., Georgel P. T., Denny P. C., Culp D. J. (2003) The sld mutation is specific for sublingual salivary mucous cells and disrupts apomucin gene expression. Physiol. Genomics 14, 95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hayashi Y., Kojima A., Hata M., Hirokawa K. (1988) A new mutation involving the sublingual gland in NFS/N mice. Partially arrested mucous cell differentiation. Am. J. Pathol. 132, 187–191 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kojima A., Hata M. (1988) Sublingual gland differentiation arrest in the NFS/N subline. Mouse News Letter 80, 147 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Das B., Cash M. N., Hand A. R., Shivazad A., Culp D. J. (2009) Expression of Muc19/Smgc gene products during murine sublingual gland development. Cytodifferentiation and maturation of salivary mucous cells. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 57, 383–396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taudien S., Rump A., Platzer M., Drescher B., Schattevoy R., Gloeckner G., Dette M., Baumgart C., Weber J., Menzel U., Rosenthal A. (2000) RUMMAGE. A high-throughput sequence annotation system. Trends Genet. 16, 519–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Soriano P. (1997) The PDGF alpha receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development 124, 2691–2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lakso M., Sauer B., Mosinger B., Jr., Lee E. J., Manning R. W., Yu S. H., Mulder K. L., Westphal H. (1992) Targeted oncogene activation by site-specific recombination in transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 6232–6236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sallés F. J., Strickland S. (1999) Analysis of poly(A) tail lengths by PCR. The PAT assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 118, 441–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Manly K. F., Cudmore R. H., Jr., Meer J. M. (2001) Map Manager QTX, cross-platform software for genetic mapping. Mamm. Genome 12, 930–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Houseley J., Tollervey D. (2009) The many pathways of RNA degradation. Cell 136, 763–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schoenberg D. R., Maquat L. E. (2012) Regulation of cytoplasmic mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 246–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dang Y., Low W. K., Xu J., Gehring N. H., Dietz H. C., Romo D., Liu J. O. (2009) Inhibition of nonsense-mediated mRNA decay by the natural product pateamine A through eukaryotic initiation factor 4AIII. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23613–23621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Buttiglione M., Cangiano G., Goridis C., Gennarini G. (1995) Characterization of the 5′ and promoter regions of the gene encoding the mouse neuronal cell adhesion molecule F3. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 29, 297–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zimprich A., Biskup S., Leitner P., Lichtner P., Farrer M., Lincoln S., Kachergus J., Hulihan M., Uitti R. J., Calne D. B., Stoessl A. J., Pfeiffer R. F., Patenge N., Carbajal I. C., Vieregge P., Asmus F., Müller-Myhsok B., Dickson D. W., Meitinger T., Strom T. M., Wszolek Z. K., Gasser T. (2004) Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron 44, 601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Couwenhoven R. I., Norris K., Denny P. A., Denny P. C. (1995) Identification and expression of a mouse sublingual gland cDNA. J. Dent. Res. 74, (Suppl. 1) 196 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bogart B. I. (1971) The fine structural localization of acetylcholinesterase activity in the rat parotid and sublingual glands. Am. J. Anat. 132, 259–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Garrett J. R. (1988) Innervation of salivary glands. Neurohistological and functional aspects, in The Salivary System (Sreebny L. M., ed) pp. 69–93, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dreyfuss G., Kim V. N., Kataoka N. (2002) Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 195–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Isken O., Maquat L. E. (2008) The multiple lives of NMD factors. Balancing roles in gene and genome regulation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 699–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Galante P. A., Sakabe N. J., Kirschbaum-Slager N., de Souza S. J. (2004) Detection and evaluation of intron retention events in the human transcriptome. RNA 10, 757–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sakabe N. J., de Souza S. J. (2007) Sequence features responsible for intron retention in human. BMC Genomics 8, 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stamm S., Zhu J., Nakai K., Stoilov P., Stoss O., Zhang M. Q. (2000) An alternative-exon database and its statistical analysis. DNA Cell Biol. 19, 739–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hui J., Hung L. H., Heiner M., Schreiner S., Neumüller N., Reither G., Haas S. A., Bindereif A. (2005) Intronic CA-repeat and CA-rich elements. A new class of regulators of mammalian alternative splicing. EMBO J. 24, 1988–1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheli Y., Kunicki T. J. (2006) hnRNP L regulates differences in expression of mouse integrin α2β1. Blood 107, 4391–4398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hung L. H., Heiner M., Hui J., Schreiner S., Benes V., Bindereif A. (2008) Diverse roles of hnRNP L in mammalian mRNA processing. A combined microarray and RNAi analysis. RNA 14, 284–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. House A. E., Lynch K. W. (2006) An exonic splicing silencer represses spliceosome assembly after ATP-dependent exon recognition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 937–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Brow D. A. (2002) Allosteric cascade of spliceosome activation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 36, 333–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Heiner M., Hui J., Schreiner S., Hung L. H., Bindereif A. (2010) hnRNP L-mediated regulation of mammalian alternative splicing by interference with splice site recognition. RNA Biol. 7, 56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim J. H., Hahm B., Kim Y. K., Choi M., Jang S. K. (2000) Protein-protein interaction among hnRNPs shuttling between nucleus and cytoplasm. J. Mol. Biol. 298, 395–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang Z., Burge C. B. (2008) Splicing regulation. From a parts list of regulatory elements to an integrated splicing code. RNA 14, 802–813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]