Abstract

While it has been well-documented that drugs of abuse such as cocaine can enhance progression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated neuropathological disorders, the underlying mechanisms mediating these effects remain poorly understood. The present study was undertaken to examine the effects of cocaine on microglial viability. Herein we demonstrate that exposure of microglial cell line-BV2 or rat primary microglia to exogenous cocaine resulted in decreased cell viability as determined by MTS and TUNEL assays. Microglial toxicity of cocaine was accompanied by an increase in the expression of cleaved caspase-3 as demonstrated by western blot assays. Furthermore, increased microglial toxicity was also associated with a concomitant increase in the production of intracellular reactive oxygen species, an effect that was ameliorated in cells pretreated with NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin, thus emphasizing the role of oxidative stress in this process. A novel finding of this study was the involvement of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) signaling mediators such as PERK, Elf2α, and CHOP, which were up regulated in cells exposed to cocaine. Reciprocally, blocking CHOP expression using siRNA ameliorated cocaine-mediated cell death. In conclusion these findings underscore the importance of ER stress in modulating cocaine induced microglial toxicity. Understanding the link between ER stress, oxidative stress and apoptosis could lead to the development of therapeutic strategies targeting cocaine-mediated microglial death/dysfunction.

Keywords: Cocaine, Microglia, BV2 cells, Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress, CHOP

Introduction

Cocaine is one of the most commonly abused drugs in the United States and other parts of the world. It is an indirect dopamine agonist acting by antagonizing dopamine reuptake mechanisms. In addition to its addictive properties, cocaine has also recently been shown to induce physiological changes in the cell via its interaction with the Sigma -1 (σ-1) receptor (Buch et al, 2011; Hayashi & Su, 2007; Yao et al, 2011). For example, cocaine has been shown to accelerate the incidence and progression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 associated neurological disorders (HANDs) (Aksenov et al, 2006; Gurwell et al, 2001; Turchan et al, 2001) by regulation the expression of certain chemokines (Yao et al, 2010) and adhesion molecules (Yao et al, 2011).

Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a well-orchestrated protein-folding machine composed of chaperone proteins that catalyze protein folding and sensors that detect the presence of misfolded or unfolded proteins [reviewed in (Walter & Ron, 2011)]. Factors that perturb ER function and contribute to the development of ER stress include increases in protein synthesis or protein misfolding rates exceeding the capacity of protein chaperons, alterations in the calcium stores in the ER lumen, oxidative stress and changes in the redox balance in the ER lumen (Tabas & Ron, 2011).

Unfolded protein response (UPR) is triggered when there is an imbalance between protein synthesis and folding capacity of ER. Three different protein families signal for the UPR through shared and independent gene targets: (1) activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), (2) double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR) like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), and (3) inositol requiring kinase 1 (IRE1) (Chakrabarti et al, 2011). These are the three major intracellular events that lead to UPR: (1) ER associated degradation (ERAD) to reduce the population of misfolded proteins from the ER. (2) Increased expression of chaperon proteins to facilitate protein folding. (3) ER stress induced autophagy or apoptosis is mediated by IRE1 and CHOP proteins (Lin et al, 2008; Schroder, 2008; Xu et al, 2005).

PERK signals for both pro-survival as well as pro-apoptotic signals following the accumulation of misfolded proteins (Chakrabarti et al, 2011). PERK reduces the translation by phosphorylating α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 (eIF2α) (Harding et al, 1999; Shi et al, 1999; Shi et al, 1998). Mechanically, activation of PERK upon ER stress signals for the dimerization and trans-autophosphorylation of its cytosolic domain, leading to the recruitment of its substrate, eIF2α which is then phosphorylated at Ser51, inhibiting pentameric guanine exchange factor eIF2B from recycling eIF2 to its active GTP bound form (Marciniak et al, 2006; Shi et al, 1999). Persistent ER stress even after attenuated transcription increases oxidative stress leading to cell death. Caspases are activated from their zymogens (pro-caspases), in response to various apoptotic signals. Initially caspase-8 and caspase-9 are activated in response to prolonged oxidative stress (Muzio et al, 1998). Followed by this the executioner caspases such as caspases-3,6 & 7 are activated, and they undergo several proteolytic processes facilitating cell death. Noteworthy that executioner caspases also activate initiator caspases, producing a positive feedback.

Although cocaine induced brain cell death is well studied (Crawford et al, 2007; Dabbouseh & Ardelt, 2011; Garcia et al, 2012; Shin et al, 2007), the molecular mechanism(s) of microglial cell death in response to cocaine remain poorly understood. Microglia are the resident macrophages of brain and spinal cord, key for innate immune response. Activated microglia release highly neurotoxic substances including glutamate, nitric oxide, and super oxide dismutase (SOD). Persistent activation of microglia ultimately culminates into apoptosis. Overactivated microglia are thus analogous to a “double-edged sword”, primarily functioning to phagocytoze the damaging neurons and, in turn, undergoing apoptosis due to uncontrolled activation. The present study was aimed to demonstrate the molecular mechanism(s) of cocaine-induced microglial cell death with a focus on ER stress mediators. This study not only provides a novel mechanism of cocaine induced microglial cell death, but also shed light on novel therapeutic targets that could be developed for treatment of neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials Methods

Cell culture

Immortalized mouse microglia (BV2) cells were plated (75cm corning cell culture flask) at a density of 1×105/ml and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) with 4g/L glucose (Gibco) supplemented with heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (10% v/v), 2mM glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 mg/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Confluent cells were re-plated at a density of 1–5×105/ml for various experiments.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfection

siRNA targeted against CHOP mRNA were obtained from Thermo Scientific Dharmacon RNAi Technologies (ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool - Mouse, Cat# L-062068-00-0005). For siRNA transfection, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, Dharma-FECT 1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon) was combined with serum free DMEM medium (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for 5 min at room temperature. The CHOP siRNA was then added into the mixture described above and incubated for 20 min at room temperature, after which the combined mixture was added to the cells to have the final concentration of 100nM CHOP siRNA or scrambled siRNA. The cell culture plate was shaken gently for 5s and incubated for 24 h at 37°C. Knockdown efficiencies were determined by western blotting.

Measurement of oxidative stress

The Image-iT™ LIVE Green Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Detection Kit obtained from Invitrogen (cat#136007) was used to estimate ROS in live BV2 cells. Briefly, BV2 cells with different treatments were trypsinized and centrifuged, and the resulting cell pellet was stained for 30 minutes with 15μM 5-(and -6)-carboxy-2”,7”- dichlorodihydroflourescein diacetate (carboxy- H2-DCF-DA; Molecular Probes Inc) to assess cytoplasmic ROS.

TUNEL staining

BV2 or rat primary cells were plated at a density of 1×105 cells per well in a 24-well plate with cover slips to study the morphological features of apoptosis (cell shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and DNA fragmentation and TUNEL staining). Followed by serum-starvation, cells were treated with 10μM cocaine and/or pretreated (1hr) with 100uM NADPH oxidase inhibitor, apocynin and incubated for 48 (BV2) or 72hrs (primary microglia) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 30 min with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. The fixed cells were permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X100 in PBS for 30 min, followed by staining with TUNEL reaction mixture for 60 min, according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Roche, Palo Alto, CA). Coverslips were mounted using Prolong gold anti fading mounting medium with DAPI (Invitrogen) as counterstaining and the slides were visualized under dark field using a fluorescence microscope. Six to eight images per treatment group were analyzed. Image analysis of tunnel positive cells was done using Image J software (version 1.37; NIH, Bethesda, MD). Fluorescent images were acquired at room temperature on a Zeiss Observer. Images were processed with the use of AxioVs 40 Version 4.8.0.0 software (Carl Zeiss, MicroImaging GmbH). Threshold intensity for DAPI labeling was set to allow DAPI signals to be counted while eliminating false positive background staining. The number of DAPI-positive cells was then quantified for all images. Similarly, threshold intensity for TUNEL labeling was set to allow counting of TUNEL-positive cells while eliminating false-positive background staining. After quantifying the number of TUNEL-positive cells for all the images, the percentage of TUNEL-positive cells to the total number of DAPI-positive cells was determined. The mean percentage (±SEM) of all images from each treatment group was reported.

MTS assay

Microglial cell viability was measured by (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium) (MTS) method. Briefly, BV2 cells were collected from culture flask and seeded in 96-well plates. Different seeding densities were optimized at the beginning of the experiments and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 48hrs. Serum starved cells were then treated with various concentrations of cocaine (1, 10, 100 μM) or pretreated (1hr) with 100μM NADPH oxidase inhibitor, apocynin or 24hrs pretreatment with CHOP siRNA. After incubation for up to 48h, 20μl MTS reagent dissolved in DMEM at a final concentration of 5mg/ml was added to each well and incubated in CO2 incubator for 4 h. Finally, the absorbance of each well was obtained using a plate counter at 490 nm.

Western blotting

Treated cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 1.0% NP-40 and 0.5% sodium deoxycholate) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Equal amounts of the corresponding proteins were electrophoresed in sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels (12%) under reducing conditions followed by transfer to PVDF membranes. Blots were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk or BSA in tris buffered saline and probed with antibodies recognizing p(T981)-PERK, (cat# SC32577) and PERK (cat# SC13073) Santacruz Biotechnology, 1:200; eIF2α (cat# 5324S), p(S51)eIF2α cat# 5324S, cleaved caspases-3 (cat # 9661), caspases-3 (cat #9662S), and CHOP (cat#2895s) Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, 1:1000). The secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase conjugated to goat anti mouse/rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:5000). Signals were detected by chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Immunohistochemistry

Adult rats weighing 150-200g were administered cocaine (daily dose of 20mg/kg body weight; IP) for 14 days and sacrificed 1hr after the final dose for the preparation of brain tissue sections. Rats were perfused transcardially using chilled 4% paraformaldehyde. Free-floating sections encompassing the entire brain were sectioned at 40μm using cryostat. For Iba1 (cat#019-19741, Wako) and CHOP co-immunostaining, tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Fluorescent tagged goat anti-rabbit (594nm, Red), goat anti-mouse (488nm, Green) secondary antibodies were used to probe Iba1and CHOP expression, respectively. Immunostained floating tissue samples were gelatin mounted and examined for co-localization of Iba1 and CHOP protein. Images were captured at wavelengths encompassing the emission spectra of the probes, with a 40× objective. The fluorescence emission of each probe and autofluorescence of the tissue samples were analyzed by Nuance multispectral imaging system (Cambridge Research Instruments, Worburn, MA), and Nuance image analysis software. These spectra were incorporated into a spectral un-mixing algorithm (Nuance system) that quantitatively separated the grayscale images representing each spectral component. The grayscale images representing each fluorescent probe were exported from the Nuance system to the image analysis software for the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by student t test using Graphpad Prism 5 software. Results were judged statistically significant if P <0.05.

Results

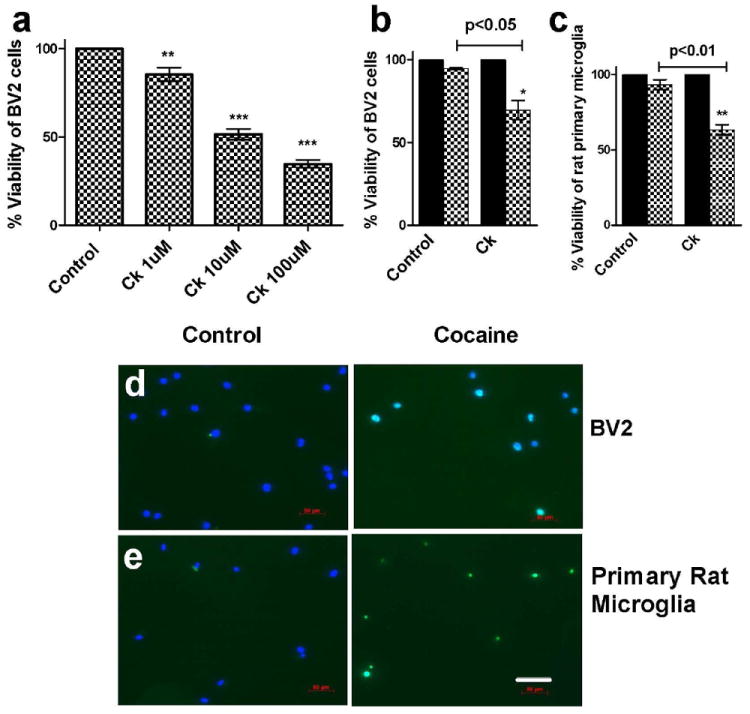

Cocaine reduces microglial cell viability by activating pro-apoptotic pathways

In order to investigate whether cocaine causes microglial cell death, cell viability assay was performed using MTS reagent (Fig.1a). BV2 cells were treated with 1 or 10 or 100μM cocaine for 48hrs and assayed for cell viability using MTS reagent (Fig.1a). As shown in Fig.1, cocaine dose dependently reduced (1, 10, 100μM; 90, 55 & 37%; p<0.01, p<0.001& p<0.001; respectively) BV2 cell viability compared to the untreated control cells. To confirm the results obtained from MTS assay, we performed TUNEL staining assay for BV2 cells after 10μM cocaine treatment for 48hrs and reproduced the reduction in cell viability (69%, p<0.05, Fig.1.b) observed with MTS assay. 10μM concentration of cocaine was chosen for rest of the study as it is physiologically relevant among cocaine users and experimentally validated by previous studies (Yao et al, 2009; Yao et al, 2010). We then sought to study the effect of cocaine on rat primary microglia following the same TUNEL staining procedure as demonstrated for BV2 cells. Consistent to the results obtained with BV2 cells, cocaine also significantly reduced rat primary microglial cell viability (70%, p<0.01 Fig.1.c). The representative pictures demonstrate TUNEL (green) positive nucleus (blue) in both BV2 cells (b) and primary rat microglia (c).

Figure 1. Cocaine reduces the microglial cell viability.

(a) BV2 cells were treated with 1 or 10 or 100μM cocaine for 48hrs and assayed for cell viability using MTS reagent. Results show that cocaine significantly reduces BV2 cell viability in a dose dependent manner. Quantitative analysis of TUNEL positive BV2 cells (b) or primary rat microglia (c) indicates the reduction in cell viability after 48h (b) or 72h (c) of cocaine treatment. The representative pictures show TUNEL (green) positive nucleus (blue) in BV2 cells (d) or primary rat microglia (e). Scale: 70μM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

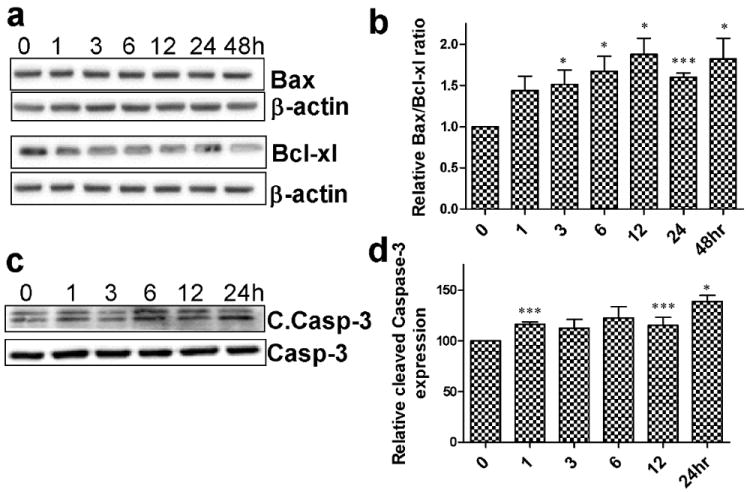

To corroborate the findings that cocaine-induced microglial toxicity involved apoptotic pathway, we next sought to investigate the ratio of pro and anti-apoptotic makers Bax and Bcl-xl, respectively. Changes in these biomarker levels indicate whether the cells experience apoptosis associated signals. As expected, the Bax to Bcl-xl ratio was significantly increased (Fig.2a&b, p<0.05, p<0.001) with time following exposure to cocaine, thereby indicating the kinetics of cell death in presence of cocaine. We then investigated the expression of apoptosis executer protein caspases-3 and its proteolytically cleaved active fragment known as “cleaved caspase-3” in cells treated with cocaine. Consistent with the findings on reduction of cell viability in presence of cocaine using MTS and TUNEL assays, activation of caspase-3 levels was also significantly upregulated (Fig.2.c&d; p<0.001) in cocaine treated BV2 cells compared with untreated control group.

Figure 2. Cocaine induces the expression of Pro-apoptotic proteins in BV2 cells.

(a&c) Immunoblots represent pro [Bax, cleaved caspase3 (c.caspase)] and anti-apoptotic (Bcl-xl) marker protein expression levels in BV2 cells following 10μM cocaine treatment. (b&d) Quantitative analysis reveals pro-apoptotic protein levels significantly (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001) elevated following 10μM cocaine treatment compared to the 0hr control.

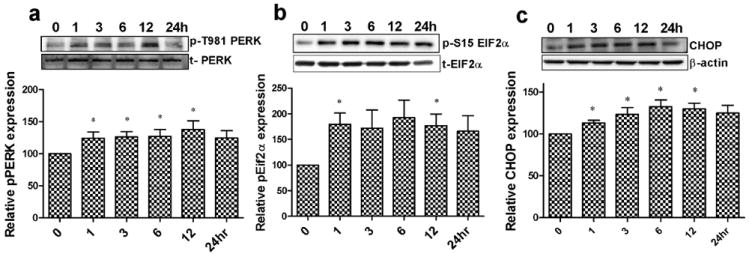

ER stress marker protein levels are altered following cocaine treatment in BV2 cells

Having established that cocaine reduces microglial cell viability, we next sought to examine the mechanisms leading to cell death. Phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2α is an early indication that the cells are undergoing ER stress. Therefore, we next studied time-dependent phosphorylation of Thr981(PERK) and Ser51(eIF2α) at various times points (0 to 24hrs) following cocaine treatment of BV2 cells. Consistent with our hypothesis, the phosphorylation levels of both Thr981 (PERK) (Fig.2a) and Ser51 (eIF2α) (Fig.2b) were significantly elevated (p<0.05), with maximal phosphorylation between 6-12hrs compared to the untreated control group. Furthermore, we also assessed the expression level of another protein - CHOP, a transcription factor that signals both directly and indirectly the pro-apoptotic protein pathway (Tabas & Ron, 2011), and that is upregulated following expression of PERK and eIF2α. Interestingly, CHOP protein levels were significantly (p<0.05) elevated (Fig.2.c) in a time-dependent manner following cocaine exposure with the maximal expression at 24 hrs.

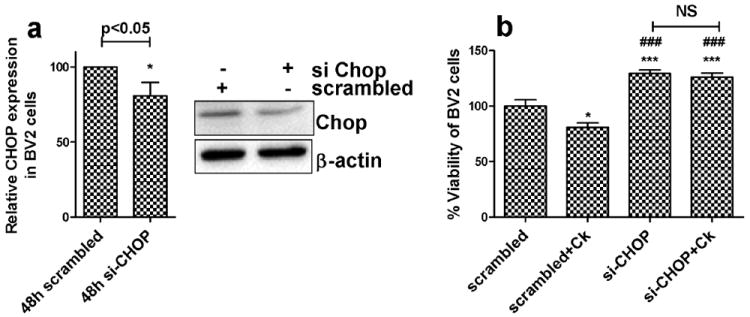

CHOP plays a role in cocaine induced toxicity in BV2 cells

Having determined that ER stress pathway is upregulated following cocaine exposure, the next step was to link the ER stress with apoptosis. Since CHOP is critical for executing the pro-apoptotic pathway, we next sought to determine its role in apoptosis using the CHOP small interfering RNA (siRNA) to block endogenous CHOP protein expression. Twenty four hours following transfection of BV2 cells with CHOP siRNA, there was significant reduction of CHOP protein level compared to the cells treated with scrambled (non-specific) siRNA (Fig.4a, p>0.05). To ascertain the role of CHOP in cocaine-mediated cell death, cell viability was examined in cells transfected with CHOP and scrambled siRNA BV2 cells exposed to cocaine. As shown in Fig. 4b, viability of cells transfected with CHOP siRNA was significantly higher (129%, p<0.001) compared with scrambled siRNA cells not exposed to cocaine (100%). CHOP siRNA and cocaine treated cells demonstrated no significant difference (126%) in viability compared to CHOP siRNA alone treated cells. These results thus demonstrate the role of CHOP in cocaine induced microglial cell death.

Figure 4. Involvement of CHOP in cocaine mediated toxicity in BV2 cells.

(a) BV2 cells were transfected with 100nM scrambled (nonspecific) or CHOP siRNA for 24hrs and treated with 10uM cocaine for 48hrs, followed by assessment of cell viability using MTS assay. Results show that CHOP siRNA pretreatment not only protected BV2 cells from cocaine induced toxicity but also significantly (***p<0.001) increased cell viability compared to scrambled siRNA control or scrambled siRNA+cocaine. In addition, CHOP siRNA and CHOP siRNA+cocaine treated group did not exhibit any significant difference in cell viability. (b) Quantitative analysis of (and immunoblot) CHOP protein expression in BV2 cells treated with 100nM scrambled (nonspecific) siRNA or CHOP siRNA for 48hrs, confirming CHOP siRNA activity.

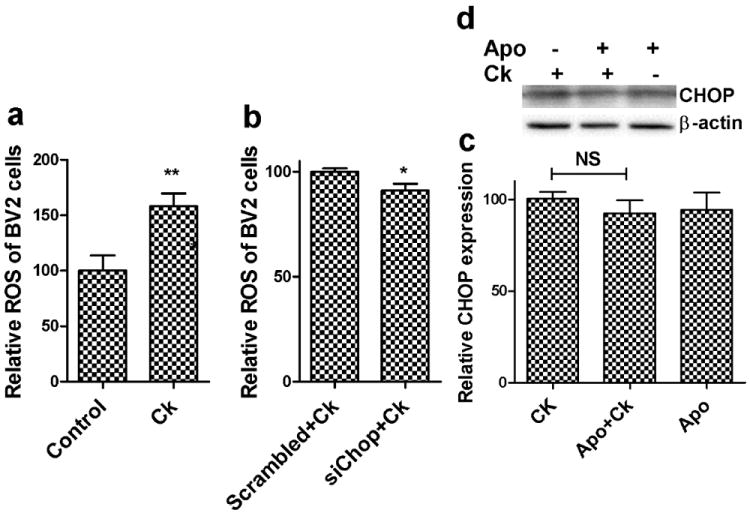

Involvement of ROS in cocaine-mediated cell death

Excessive ROS production can lead to oxidation of macromolecules and has been implicated in mitochondrial (mt) DNA mutations, ageing, and cell death (Orrenius, 2007). Having established the role of CHOP in cocaine-mediated cell death, we next sought to investigate the link between ROS and CHOP protein expression. In order to examine this, ROS levels were monitored in cocaine treated BV2 cells that were transfected with either CHOP or scrambled siRNA (Fig.5a&b). Our findings indicated that cocaine treated cells produced significantly more (1.7 fold increase, p<0.01) ROS compared with the untreated control group. Conversely, CHOP siRNA and cocaine treated BV2 cells produced significantly less (p<0.05) ROS compared to scrambled siRNA transfected, cocaine treated cells. Intriguingly, these results revealed that ROS production was mediated by CHOP signaling, with CHOP being upstream of ROS production. We next wanted to validate the finding that CHOP was indeed an upstream mediator of ROS. We thus hypothesized that blocking ROS could have no effect on CHOP if the latter was an upstream factor. CHOP protein expression was thus monitored by western blot in BV2 cells exposed to cocaine in the presence or absence of NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin pretreatment. In agreement with the CHOP siRNA study and as expected, apocynin treatment had no effect on CHOP expression compared to cocaine alone exposed cells (Fig.5c&d). These findings further validate the role of CHOP signaling in generation of ROS production.

Figure 5.

Involvement of CHOP in cocaine mediated reactive oxidative species (ROS) production during ER stress. Control BV2 cells (a) or pretreated with 100nM scrambled (nonspecific) siRNA or CHOP siRNA (b) for 24hrs were treated with 10μM cocaine and assayed for ROS using 2’,7’ dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFDA) reagent. Results show that cocaine significantly increased (**p<0.01) ROS compared to untreated control group, whereas CHOP siRNA treated cells significantly decreased (*p<0.05) ROS production compared to scrambled siRNA treated cells. (c) Quantitative analysis of cells treated with 10μM cocaine and/or 100μM apocynin were monitored for CHOP expression using western blot. (d) Representative western blot for CHOP expression. Results indicate that apocynin treatment had no significant effect on cocaine induced CHOP expression in BV2 cells.

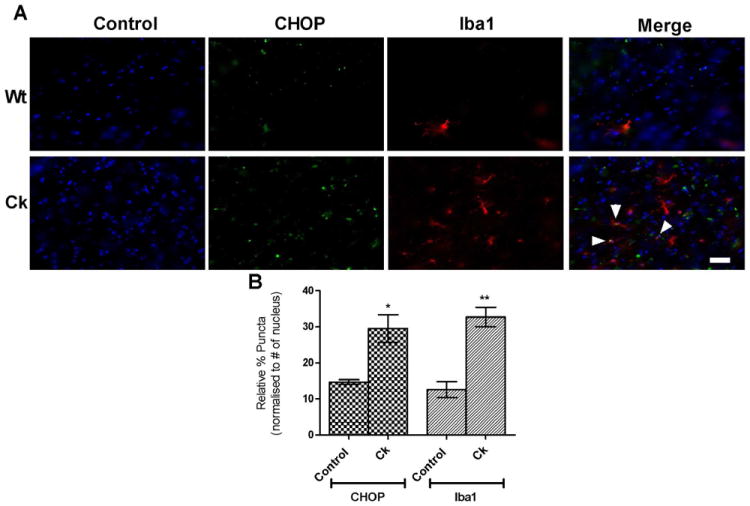

Cocaine up regulated CHOP protein expression in rat microglia in vivo

To confirm the in vitro findings of cocaine-mediated induction of ER stress, we sought to examine the effects of cocaine in vivo. Two groups of rats were treated either with saline or a daily dose of cocaine at 20mg/kg body weight IP for 14 days and were sacrificed 1hr following the final dose. Immunostained floating tissue samples were then examined for co-localization of Iba1 (marker for microglia) and CHOP protein using Zeiss fluorescent microscope. Nuance multispectral imaging system was used to analyze the images for CHOP (green) and Iba1 (red) signal (in appropriate wavelength). As shown in Fig.6a&b, cocaine treatment increased both CHOP and Iba1 protein expression (*p<0.05 and **p<0.01) compared to untreated rat brain tissue. The co-localization of CHOP and Iba1 protein expression is marked with arrow head. These results substantiate our in vitro findings about cocaine induced ER stress using BV2 cells.

Figure 6.

Cocaine up regulated CHOP protein expression in rat microglia in vivo. Adult rats weighing 150-200g were administered with cocaine (daily dose of 20mg/kg body weight;IP) for 14 days and sacrificed 1hr after the final dose for the preparation of brain tissue section. Immunostained floating tissue samples were gelatin mounted and examined for co-localization of Iba11 and CHOP protein using nuance multi spectrum imaging system. Scale: 50μM. Images revealed that cocaine induced CHOP (green) expression which co-localized (marked with arrowhead) with activated microglia (Iba1, red) in the rat brain.

Discussion

Cocaine abuse is known to cause serious health problems, accidents and death. Cocaine is widely used by injection drug users, who constitute one third of the new AIDS cases in the United States. Although the pharmacology of cocaine action and adverse effects have been investigated for several decades, underlying molecular mechanisms are yet to be clearly understood, as cocaine acts through multiple pathways in the brain to elicit euphoric as well as deleterious effects. In addition to activation of dopaminergic pathway, which is long believed to be the only mechanism of cocaine action, increasing number of studies demonstrate that cocaine binds with an ER chaperon protein, sigma-1 receptor (Katz et al, 2011; Matsumoto et al, 2003). Microglia activation and induction of innate immune gene expression is the basis for drug addiction (Crews & Vetreno, 2011; Crews et al, 2011). Initial activation of microglia increases expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins and toll-like receptor proteins (TLR), key proteins involved in innate immune amplification (Colton & Wilcock, 2010). Prolonged microglial activation however, not only causes neurotoxicity (Block & Hong, 2007; Block et al, 2007) but is also reported to result in cell apoptosis via different mechanisms (Ji et al, 2007; Yang et al, 2006; Yang et al, 2002). Recent studies have identified the effect of cocaine on ER stress with the role of glutamate receptors in mediating neurotoxicity (Choe et al, 2011). It has also been reported that in the rat dorsal striatum cocaine administration induces ER stress and activates c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway resulting in cell death (Go et al, 2010).

Continuing the investigation in this direction, in the present study we sought to elucidate the molecular mechanism(s) by which cocaine-induced ER stress mediated microglial cell death. Firstly, we examined whether exposure of microglial BV2 cells and rat primary microglia exposed to cocaine could result in cell death. Unambiguously, cocaine produced a dose dependent reduction of microglial cell viability as shown in Fig.1a-e. This prompted us to investigate whether there was involvement of the ER stress pathway in this process. We sought to examine the PERK pathway - one of the three important UPR signaling pathways. In agreement with our hypothesis, cocaine exposure of microglia resulted in phosphorylation of both PERK and its downstream translation repressor protein, eIF2α (Fig.3a-c). Phosphorylation of PERK suggested that the chaperone protein Bip was dissociated from the N-terminal of PERK leading to initiation of autophosphorylation of the kinase domain of PERK at Thr981 amino acid. This, in turn, serves as a signal for phosphorylation of eIF2α at Ser51, which subsequently leads to reduction of the ER protein load by attenuating translation. These early findings led to the suggestion that the microglia were attempting to overcome the effects of the noxious stimuli induced by cocaine exposure. Prolonged PERK activation is known to subsequently induce the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein CHOP via activation of ATF6 signaling. Our finding of increased CHOP expression following cocaine treatment (Fig.3c) was indicative of microglial apoptosis. These findings lead to the suggestion that cocaine exposure results in disruption of the ER homeostatic balance with the induction of cellular apoptosis. To understand the mechanism of programmed cell death, we next sought to assess the ratio of pro and anti-apoptotic proteins (Bax:Bcl-xl), and the cell death executor protein, caspase-3 and its proteolytically cleaved fragment, cleaved caspases-3 in cocaine-exposed microglia. Consistent with the hypothesis, cocaine treatment increased expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and cleaved caspases-3 (Fig.2a-d).

Figure 3. Effect of cocaine on the ER stress marker protein expression in BV2 cells.

Representative immunoblots and quantitative analysis of ER stress marker protein levels following 10μM cocaine treatment for phosphorylation of Thr981(PERK) (a) Ser51(eIF2α) (b), and CHOP (c), represent ER stress marker protein expression levels in BV2 cells following 10μM cocaine treatment. Results indicate that there was a significant (*p<0.05) increase in phosphorylation of eIF2α, PERK, and CHOP expression after cocaine treatment.

It has previously been reported that the downstream ER sensor pro-apoptotic protein CHOP increases protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed ER. In fact, CHOP deletion has been shown to protect cells from ER stress damage by decreasing the levels of ER client proteins (Marciniak et al, 2004). We thus sought to extend the investigation and examine whether CHOP protein-mediated induction of oxidative stress was involved in apoptosis. Silencing CHOP by siRNA resulted in amelioration of cocaine-induced ROS and cell viability (Fig.4b) in microglial cultures. Reciprocally, pretreatment of cells with the NADPH oxidase inhibitor, apocynin did not downregulate CHOP levels, indicating thereby that CHOP lies upstream of ROS production (Fig.5 a-d & Fig.S1a-e).

In vivo experiments demonstrate that cocaine administration to rats increased the expression of Iba1 and CHOP (Fig.6a&b), makers for microglia activation and ER stress respectively. These findings indicate the in vivo activation of microglia as an active immune response to cocaine exposure subsequently leads to the ER stress. However, 14 days treatment may not be long enough to cause the activation induced microglial cell death in vivo. Nevertheless, we found cocaine induced cell death in both BV2 cells and rat primary microglia. This can be reasoned that 48hrs cocaine treatment directly on the cells in the culture flask produce persistent activation of microglia, which in turn causes ER stress mediated cell death. Since microglial activation is a hallmark feature of HIV-1 associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) and based on our findings that cocaine exposure leads to a reduction in the number of microglia, it can be argued that cocaine mediated apoptosis of microglia can actually dampen cellular activation, thereby being beneficial for the degenerative brain. However, this conclusion cannot be reached from our studies since it is not clear whether cocaine exposure leads to apoptosis of activated or normal resting microglia. Furthermore, since activation can be both beneficial as well as detrimental depending on the time and extent of activation, it remains to be determined whether cocaine is apoptotic for the M1 or the M2 microglia

In conclusion, the present study unravels a novel mechanism involved in cocaine mediated microglial cell toxicity. Insights into the role of ER proteins that could be responsible for microglial apoptosis will be helpful for identification of novel possible biomarkers and therapeutic drug targets. Recent discovery of a therapeutic peptide (humanin) against pro-apoptotic Bax protein has received a great deal of attention for its neuroprotective effect in Alzheimer’s disease. Notably, humanin directly binds with the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, thereby changing its conformation, resulting in reversal of cell toxicity. Further research to explore novel drug target in other ER stress pathway protein like CHOP that will help treat neurological disorders in illicit drug abusers is warranted.

Supplementary Material

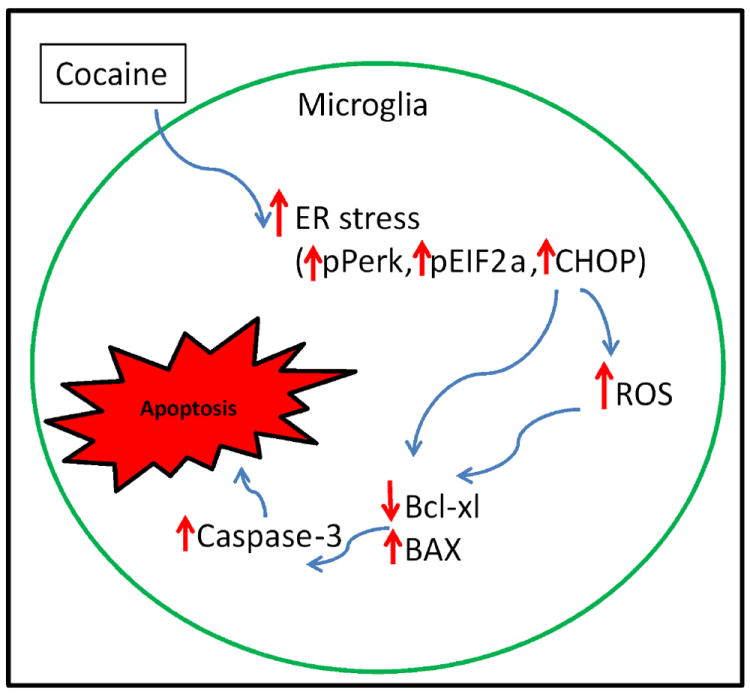

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram depicts the ER stress pathway we present in this study. Cocaine phosphorylates PERK and eILF2α, and then eventually increases the CHOP expression. CHOP signal increases the pro apoptotic protein Bax over anti-apoptotic Bcl-xl. Finally, these events activate death executor protein caspases-3, which signals for the microglial cell death.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants DA020392, DA023397 and DA024442 (SB) and DA030285 (HY) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Authors claim no actual or potential conflicts of interest

References

- Aksenov MY, Aksenova MV, Nath A, Ray PD, Mactutus CF, Booze RM. Cocaine-mediated enhancement of Tat toxicity in rat hippocampal cell cultures: the role of oxidative stress and D1 dopamine receptor. Neurotoxicology. 2006;27:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Hong JS. Chronic microglial activation and progressive dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1127–1132. doi: 10.1042/BST0351127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch S, Yao H, Guo M, Mori T, Su TP, Wang J. Cocaine and HIV-1 interplay: molecular mechanisms of action and addiction. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2011;6:503–515. doi: 10.1007/s11481-011-9297-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti A, Chen AW, Varner JD. A review of the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2011;108:2777–2793. doi: 10.1002/bit.23282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe ES, Ahn SM, Yang JH, Go BS, Wang JQ. Linking cocaine to endoplasmic reticulum in striatal neurons: role of glutamate receptors. Basal Ganglia. 2011;1:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.baga.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton CA, Wilcock DM. Assessing activation states in microglia. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9:174–191. doi: 10.2174/187152710791012053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford FC, Wood M, Ferguson S, Mathura VS, Faza B, Wilson S, Fan T, O’Steen B, Ait-Ghezala G, Hayes R, Mullan MJ. Genomic analysis of response to traumatic brain injury in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (APPsw) Brain Res. 2007;1185:45–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Vetreno RP. Addiction, adolescence, and innate immune gene induction. Front Psychiatry. 2011;2:19. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Zou J, Qin L. Induction of innate immune genes in brain create the neurobiology of addiction. Brain Behav Immun. 2011;25(Suppl 1):S4–S12. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabbouseh NM, Ardelt A. Cocaine mediated apoptosis of vascular cells as a mechanism for carotid artery dissection leading to ischemic stroke. Med Hypotheses. 2011;77:201–203. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia RC, Dati LM, Fukuda S, Torres LH, Moura S, de Carvalho ND, Carrettiero DC, Camarini R, Levada-Pires AC, Yonamine M, Neto ON, Abdalla FM, Sandoval MR, Afeche SC, Marcourakis T. The neurotoxicity of anhydroecgonine methyl ester, a crack cocaine pyrolysis product. Toxicol Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go BS, Ahn SM, Shim I, Choe ES. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase is required for the regulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response in the rat dorsal striatum following repeated cocaine administration. Neuropharmacology. 2010;59:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurwell JA, Nath A, Sun Q, Zhang J, Martin KM, Chen Y, Hauser KF. Synergistic neurotoxicity of opioids and human immunodeficiency virus-1 Tat protein in striatal neurons in vitro. Neuroscience. 2001;102:555–563. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00461-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding HP, Zhang Y, Ron D. Protein translation and folding are coupled by an endoplasmic-reticulum-resident kinase. Nature. 1999;397:271–274. doi: 10.1038/16729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 2007;131:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji KA, Yang MS, Jeong HK, Min KJ, Kang SH, Jou I, Joe EH. Resident microglia die and infiltrated neutrophils and monocytes become major inflammatory cells in lipopolysaccharide-injected brain. Glia. 2007;55:1577–1588. doi: 10.1002/glia.20571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Su TP, Hiranita T, Hayashi T, Tanda G, Kopajtic T, Tsai SY. A Role for Sigma Receptors in Stimulant Self Administration and Addiction. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2011;4:880–914. doi: 10.3390/ph4060880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin JH, Walter P, Yen TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:399–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak SJ, Garcia-Bonilla L, Hu J, Harding HP, Ron D. Activation-dependent substrate recruitment by the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 kinase PERK. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:201–209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak SJ, Yun CY, Oyadomari S, Novoa I, Zhang Y, Jungreis R, Nagata K, Harding HP, Ron D. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3066–3077. doi: 10.1101/gad.1250704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto RR, Liu Y, Lerner M, Howard EW, Brackett DJ. Sigma receptors: potential medications development target for anti-cocaine agents. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;469:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01723-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzio M, Stockwell BR, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. An induced proximity model for caspase-8 activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2926–2930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrenius S. Reactive oxygen species in mitochondria-mediated cell death. Drug Metab Rev. 2007;39:443–455. doi: 10.1080/03602530701468516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder M. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:862–894. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7383-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, An J, Liang J, Hayes SE, Sandusky GE, Stramm LE, Yang NN. Characterization of a mutant pancreatic eIF-2alpha kinase, PEK, and co-localization with somatostatin in islet delta cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5723–5730. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Vattem KM, Sood R, An J, Liang J, Stramm L, Wek RC. Identification and characterization of pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit kinase, PEK, involved in translational control. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7499–7509. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin EH, Bian S, Shim YB, Rahman MA, Chung KT, Kim JY, Wang JQ, Choe ES. Cocaine increases endoplasmic reticulum stress protein expression in striatal neurons. Neuroscience. 2007;145:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I, Ron D. Integrating the mechanisms of apoptosis induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:184–190. doi: 10.1038/ncb0311-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchan J, Anderson C, Hauser KF, Sun Q, Zhang J, Liu Y, Wise PM, Kruman I, Maragos W, Mattson MP, Booze R, Nath A. Estrogen protects against the synergistic toxicity by HIV proteins, methamphetamine and cocaine. BMC Neurosci. 2001;2:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2656–2664. doi: 10.1172/JCI26373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MS, Ji KA, Jeon SB, Jin BK, Kim SU, Jou I, Joe E. Interleukin-13 enhances cyclooxygenase-2 expression in activated rat brain microglia: implications for death of activated microglia. J Immunol. 2006;177:1323–1329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang MS, Park EJ, Sohn S, Kwon HJ, Shin WH, Pyo HK, Jin B, Choi KS, Jou I, Joe EH. Interleukin-13 and -4 induce death of activated microglia. Glia. 2002;38:273–280. doi: 10.1002/glia.10057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Bethel-Brown C, Buch S. Cocaine Exposure Results in Formation of Dendritic Varicosity in Rat Primary Hippocampal Neurons. Am J Infect Dis. 2009;5:26–30. doi: 10.3844/ajidsp.2009.26.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Kim K, Duan M, Hayashi T, Guo M, Morgello S, Prat A, Wang J, Su TP, Buch S. Cocaine hijacks sigma1 receptor to initiate induction of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule: implication for increased monocyte adhesion and migration in the CNS. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5942–5955. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5618-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao H, Yang Y, Kim KJ, Bethel-Brown C, Gong N, Funa K, Gendelman HE, Su TP, Wang JQ, Buch S. Molecular mechanisms involving sigma receptor-mediated induction of MCP-1: implication for increased monocyte transmigration. Blood. 2010;115:4951–4962. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-266221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.