Abstract

Objective

The myeloid translocation genes (MTGs) are transcriptional corepressors with both Mtg8−/− and Mtgr1−/− mice showing developmental and/or differentiation defects in the intestine. We sought to determine the role of MTG16 in intestinal integrity.

Methods

Baseline and stress induced colonic phenotypes were examined in Mtg16−/− mice. To unmask phenotypes, we treated Mtg16−/− mice with dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) or infected them with Citrobacter rodentium and the colons were examined for ulceration and for changes in proliferation, apoptosis and inflammation.

Results

Mtg16−/− mice have altered immune subsets, suggesting priming towards Th1 responses. Mtg16−/− mice developed increased weight loss, diarrhoea, mortality and histological colitis and there were increased innate (Gr1+, F4/80+, CD11c+ and MHCII+; CD11c+) and Th1 adaptive (CD4) immune cells in Mtg16−/− colons after DSS treatment. Additionally, there was increased apoptosis and a compensatory increased proliferation in Mtg16−/− colons. Compared with wild-type mice, Mtg16−/− mice exhibited increased colonic CD4;IFN-γ cells in vehicle-treated and DSS-treated mice. Adoptive transfer of wildtype marrow into Mtg16−/− recipients did not rescue the Mtg16−/− injury phenotype. Isolated colonic epithelial cells from DSS-treated Mtg16−/− mice exhibited increased KC (Cxcl1) mRNA expression when compared with wild-type mice. Mtg16−/− mice infected with C rodentium had more severe colitis and greater bacterial colonisation. Last, MTG16 mRNA levels were reduced in human ulcerative colitis versus normal colon tissues.

Conclusions

These observations indicate that MTG16 is critical for colonocyte survival and regeneration in response to intestinal injury and provide evidence that this transcriptional corepressor regulates inflammatory recruitment in response to injury.

INTRODUCTION

Myeloid translocation gene-16 (also referred to as MTG16, CBFA2T3 or ETO2) is the third member of the MTG family of transcriptional corepressors and is disrupted by the t(16;21) chromosomal translocation in acute myeloid leukaemia.1–5 Chromosomal translocations often target master regulatory genes affecting growth, differentiation and apoptosis. MTG family members form repression complexes with other corepressors such as mSin3A, N-CoR/SMRT and histone deacetylases (HDAC1–3).6 MTG repression specificity occurs via interactions with transcription factors such as PLZF, BCL-6, TAL-1 and Gfi1 and, more recently, the WNT effector TCF4.7 Thus, MTGs form tertiary repression complexes at promoters with specificity dictated via interactions with trans-acting factors.3

Both MTG16 and MTGR1 are expressed in the colonic epithelium whereas MTG8 is absent.8,9 However, a quarter of Mtg8-null mice had deletion of the entire mid-gut leading to perinatal lethality.10 Mtg8−/− pups surviving past 48 h were 30%–50% smaller than their littermates, and 60% of those died by 21 days after birth. The surviving Mtg8−/− mice were smaller than their littermates, but otherwise normal. At necropsy, all organs were normal in appearance with the exception of small intestinal defects, most pronounced in the jejunum where there was marked intraluminal distention and blunted disorganised appearing villi. Analysis of Mtgr1−/− mice revealed that Mtgr1 was required for maintenance of the small intestine secretory lineage.9 In these animals, there is normal intestinal architecture at birth, but from weaning until 6–8 weeks of age there is progressive depletion of the secretory lineage in the small intestine. A rather subtle colonic phenotype was apparent with increased proliferation and mild expansion of the crypts. Collectively, the gene knockout studies suggest that MTG transcriptional corepressors play critical roles in intestinal biology and likely function in influencing stem cell behaviour.

To evaluate the contribution of MTG16 to haematopoiesis, Mtg16 deficient mice were generated by targeting exon 8 causing splicing-mediated insertion of a stop codon resulting in nonsense-mediated RNA decay.11 At birth, Mtg16−/− mice are mildly anaemic with a predominance of the granulocyte/macrophage lineage at the expense of megakaryocyte–erythroid lineages. Under conditions of haematopoietic stress/crisis, Mtg16−/− marrow had markedly attenuated multi-lineage expansion capabilities resulting in an inability for Mtg16−/− marrow to form colonies on the spleen of recipient mice.11 These observations implicate MTG16 in regulating haematopoietic stem cell programmes pivotal to lineage allocation and expansion.

Given the phenotypes associated with deletion of the other family members, we examined the intestines of Mtg16−/− mice. While the intestines of these mice initially appeared normal, we found that Mtg16−/− colons exhibited an increase in both enterocyte proliferation and intestinal permeability, and an increase in adaptive immune signatures suggesting skewing towards Th1 responses. Mtg16−/− mice developed worse colitis than their wild-type (WT) counterparts after dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) treatment. This was not model-specific as Mtg16−/− mice were also sensitive to Citrobacter rodentium infection. Multi-analyte cytokine arrays showed increased interleukin (IL)-17 and Macrophage Inflammatory Protein (MIP)-1β at baseline, which was further increased after DSS injury in the Mtg16−/− mice. Additionally, after injury, there was excessive production of interferon γ (IFN-γ), tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) and the CXC chemokine KC. Early after DSS injury there was accelerated apoptosis in the Mtg16−/− colons, with a compensatory increase in proliferation at later time points. Adoptive transfer of WT marrow into the Mtg16−/− background did not rescue the Mtg16−/− DSS phenotype of exacerbated colitis. Last, analysis of human ulcerative colitis samples demonstrated decreased MTG16 expression. Collectively, these findings indicate that MTG16 regulates the colonic microenvironment, potentially protecting against intestinal epithelial injury and inflammation.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals

Mtg16−/− mice were maintained according to an approved IACUC protocol at the Vanderbilt University animal care facility. Genotyping was performed as described.11 All experiments were performed on 8–10-week-old male and female mice.

DSS protocol

DSS, MW 40 000–50 000, was obtained from USB Corporation (Cleveland, Ohio, USA) and experiments were performed as described in online Supplementary Methods.

Induction of C rodentium colitis

Mice were orally inoculated with WT C rodentium as described.12 Briefly, bacteria were grown overnight in Luria broth and mice were infected by oral gavage with 0.1 ml of broth containing 1×108 CFU of C rodentium. Control mice received sterile broth. At the selected end point, the animals were sacrificed and the colons were removed, cleaned and Swiss-rolled for histology. Distal colon-pieces were taken for colonisation studies. For colonisation, tissues were homogenised, serially diluted in Luria broth and plated on MacConkey Agar plates; colonies were counted after 24 h; and CFU/g of colon tissues were calculated.

Enterocyte proliferation and apoptosis determination

BrdU (5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine) was injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 16.7 μg/g of body weight 2 h prior to sacrifice. Actively replicating cells were visualised by immunohistochemical labelling using anti-BrdU13 as described in online Supplementary Methods.

Assessment of apoptosis

Apoptosis rates were measured via indexing selectively labelled apoptotic cells using an in situ TUNEL assay or activated caspase-3 as described in online Supplementary Methods.

Bone marrow transplantation

Bone marrow isolated from femurs and tibias of WT mice were transplanted into Mtg16−/− mice as described in online Supplementary Methods.

RT-PCR analysis

RNA from Mtg16−/− or WT colons was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Santa Clarita, California, USA). cDNA was synthesised from 1 μg of total RNA using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (BioRad, Hercules, California, USA) and 1 μl was used as template in subsequent PCR reactions. SYBR green qRT-PCR was performed for KC, IFN-γ, IL-17, iNOS, TNFα and β-actin (see online Supplementary Methods for primer list). Human MTG16 (Hs00602520_m1) and GAPDH (Hs03929097_g1) TaqMan probes were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, California, USA). Expression was normalised to GAPDH.

Immunophenotyping

Colon tissue was enzymatically digested and isolated cells were stained for CD11b, CD11c, F4/80, Gr-1, CD3, CD4 and CD19, and MHC II surface markers with respective antibodies or isolated cells were incubated with a Golgi blocker and stained for intracellular IFN-γ. See online Supplementary Methods for additional detail.

Cytokine profiling

Thirteen cytokines and/or chemokines (IFN-γ, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 p40, TNFα, IL-12 p70, IL-13, KC,MCP-1,MIP-1α, MIP-1β) were measured from colon tissue lysates using the MILLIPLEX MAP Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine Panel kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Millipore, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) as described in online Supplementary Methods.

Intestinal permeability

Mice were anaesthetised and 100 microliters of 80 mg/ml FITC-dextran solution was delivered via rectal enema. Mice were inverted for 30 min prior to sacrificing and harvesting blood via cardiac puncture. Blood was allowed to clot followed by centrifugation and serum harvesting. Samples were read at 480 and 520 nm on a BioTek (Winooski, Vermont, USA) microplate flourometer.

Human subjects

Tissues were obtained during colonoscopies at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, following a protocol approved by the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board.

Statistics

Colon lengths and immunohistochemistry (number of stained cells) were analysed for statistical significance using Student t test, always two tailed. Grades of crypt damage were performed in a blinded manner and analysed by the non-parametric Mann–Whitney test.

RESULTS

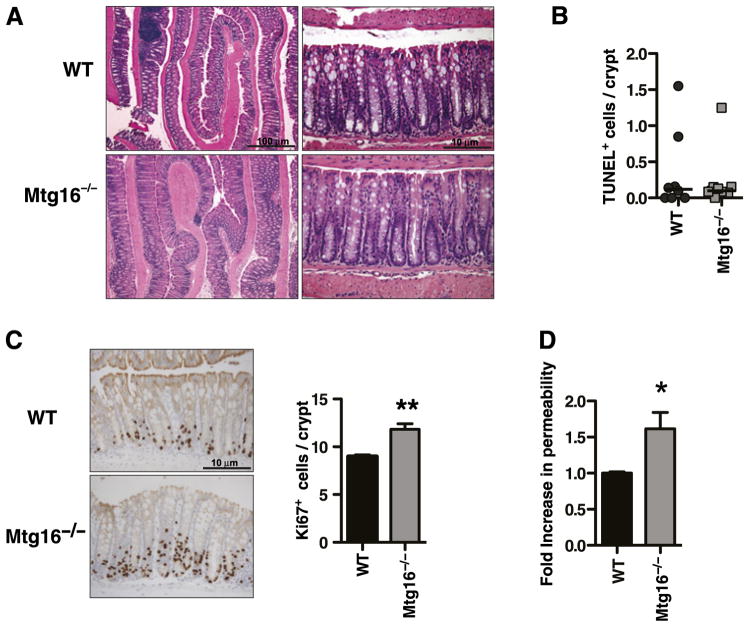

MTG16 regulates colonocyte proliferation and intestinal barrier function

Mtg16−/− mice have haematopoietic lineage allocation and proliferation defects, but nothing is known about the impact on the intestine of deleting Mtg16 or whether the haematopoietic defects have a functional impact in the gut. Therefore, we examined the Mtg16−/− mice for intestinal phenotypes. Mtg16−/− mice displayed normal enterocyte lineage allocation in the small intestine and colon and normal architecture (figure 1A and data not shown). There was no difference in apoptosis in Mtg16−/− colons in comparison with WT colons (0.10 vs 0.12 TUNEL-stained cells/crypt, p=0.86, figure 1B). However, Mtg16−/− mice, similar to Mtgr1−/− mice, showed increased colonocyte proliferation (11.8 vs 8.9 Ki67+ cells/crypt, p<0.01, figure 1C). Next, colonic permeability in 8–10-week-old WT and Mtg16−/− mice was assessed using the FITC-labelled dextran method.14–17 Mtg16−/− mice showed 60% (p<0.05) greater permeability in comparison with WT mice (figure 1D). No ultrastructural abnormalities were seen on electron microscopy (online supplementary figure 4).

Figure 1.

Myeloid translocation gene-16 (MTG16) regulates colonocyte proliferation. (A) H&E stained Mtg16−/− or WT colons. (B) In situ TUNEL staining. Results presented as the number of TUNEL labelled cells/crypt, 20 crypts/mouse counted (p=0.86) (n=9 mice/genotype). (C) Representative photomicrographs of Ki67 staining in WT or Mtg16−/− colonic crypts. Graph at right shows comparison between Mtg16−/− and WT Ki67 counts per crypt, with an average of 50 crypts/mouse counted (**p<0.01, n=4 mice/genotype). (D) FITC-dextran permeability assay (*p<0.05) (n=6 WT, n=7 Mtg16−/−).

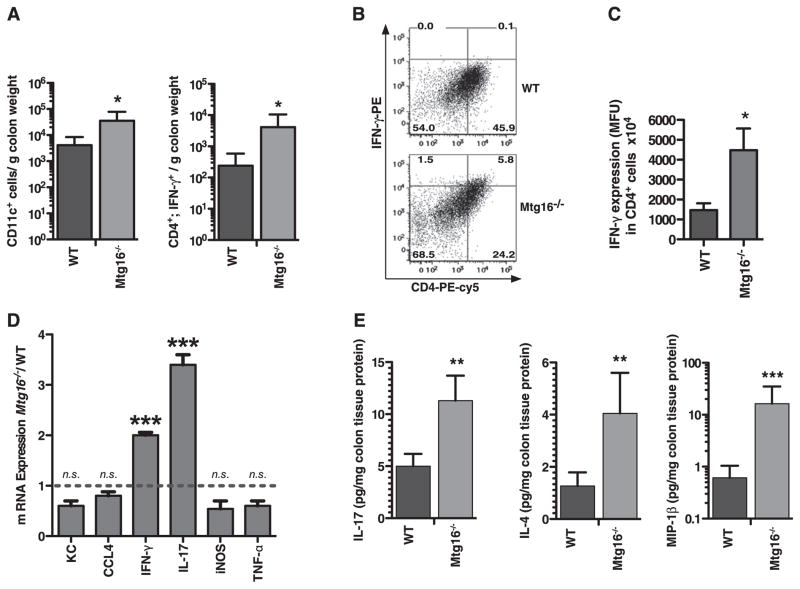

Augmented adaptive and innate immunity in Mtg16−/− colons

Because we found differences in epithelial permeability, we assessed whether there could also be baseline immune activation in Mtg16−/− mice. Immunophenotyping of Mtg16−/− colons via flow cytometry for haematopoietic cell types revealed a significant increase in dendritic cells (DCs; CD11c; 4133 vs 34 673 cells/g colon, p<0.05, figure 2A). No differences were observed in GR1+, F4/80+, CD11b+, CD3+, CD19+ or total CD4+ cells (online supplementary figure 1A). Mucosal DCs program T cell reactivity and DCs can initiate innate or adaptive immune responses. While the total number of CD4 cells was similar between genotypes, the fraction of CD4;IFN-γ cells was increased 17-fold (p<0.05) in the Mtg16−/− mice. In support of this, IFN-γ production in CD4 cells was increased threefold (1470 vs 4476 MFU/CD4+ cell, p<0.05, figure 2B,C). Increased IFN-γ as well as IL-17 expression was observed at the RNA level in Mtg16−/− colons (figure 2D). Total colonic IFN-γ was not significantly increased in the Mtg16−/− mice, suggesting that Mtg16 specifically regulates CD4;IFN-γ production (online supplementary figure 1B).

Figure 2.

Immunophenotyping of Mtg16−/− colons reveals increased innate and adaptive immunity. (A) Immunophenotyping using flow cytometry of WT or Mtg16−/− colons (WT (n=6) or Mtg16−/− (n=6) colons). (B) Representative density plots for CD4 IFN-γ-producing cells are shown (cell percentages displayed in corners). (C) Increased IFN-γ production by CD4 cells in Mtg16−/− colons. (D) mRNA expression from Mtg16−/− colons presented as fold change from WT (dashed line, SD shown, ***p<0.001). (E) Multi-analyte profiling using the Luminex platform demonstrating increased IL-17, IL-4 and MIP-1β in Mtg16−/− colons (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

Tissue-specific chemokine and cytokine production contributes to inflammatory cell recruitment. We next evaluated chemokine and cytokine production in Mtg16−/− colons using multi-analyte bead arrays. There was increased IL-17, IL-4 and MIP-1β protein (figure 2E) and no significant difference in IFN-γ, IL-12p40, MCP-1, TNFα, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-18, IL-10, MIP-1α and KC (online supplementary figure 1B) in Mtg16−/− colons. Collectively these observations suggest that Mtg16−/− colons are primed for a robust inflammatory response, and increased IFN-γ-producing CD4 cells indicates that the baseline inflammatory environment is biased towards a Th1 response.

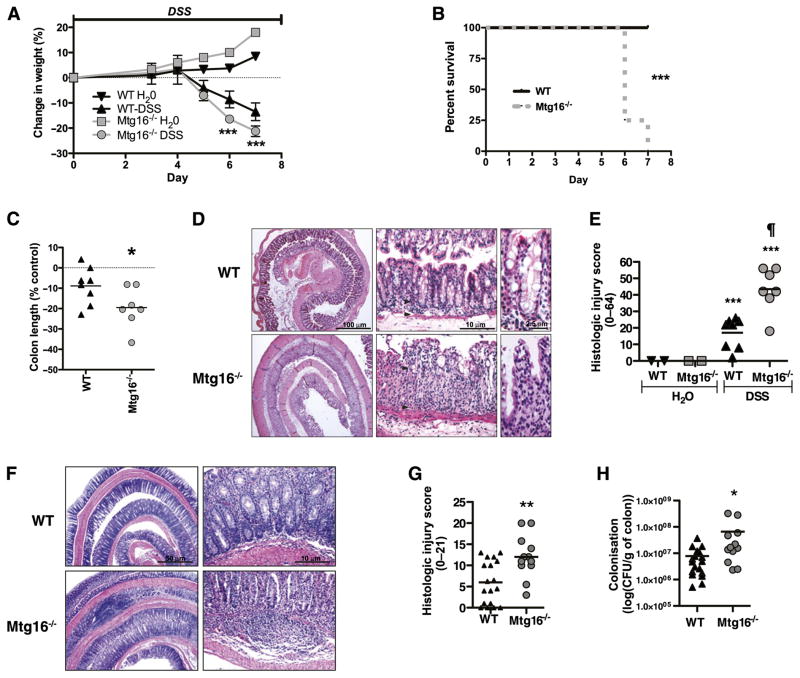

MTG16 protects from DSS induced colonic injury

Colonic Mtg16 expression is significantly reduced after either DSS or C rodentium-induced colonic injury (online supplementary figure 2). We therefore induced colitis using DSS to determine the contribution of Mtg16 to colonic injury and repair responses after stress. To maximise our ability to detect an injury phenotype in the Mtg16−/− mice, we started treatment with 4% DSS. Both WT and Mtg16−/− mice lost weight with DSS treatment; however, by day 6, the Mtg16−/− mice exhibited accelerated weight loss. By day 7, 75% of null mice exhibited hunched posture and had 20% weight loss and required euthanasia (figure 3A,B, p<0.001). At necropsy, both genotypes had malformed stool and oedematous appearing colons; however, Mtg16−/− colons were shorter, a reflection of more severe injury (figure 3C, p<0.01). Histological review of H&E-stained Swiss-rolled colons showed predominantly distal injury characterised by epithelial ulceration, inflammatory infiltrate, submucosal oedema and impaired regeneration—all indicating more severe injury in Mtg16−/− mice (Mtg16−/− 43.4, SD 5.0 vs WT 17.1, SD 3.3, p<0.001, figure 3D,E). Mtg16−/− mice also had increased colitis in the C rodentium model (figure 3F,G). This infectious colitis model encompasses both epithelial injury and immune responses. These results suggest that the role of MTG16 in epithelial integrity may be generalisable. Furthermore, culturing of colonic mucosa indicated increased bacterial colonisation, suggesting a barrier defect or increased epithelial adhesion associated with C rodentium induced injury/inflammation in the Mtg16−/− colon (figure 3H).

Figure 3.

MTG16 is involved in the regulation of colonic injury. (A) WT (n=8) or Mtg16−/− (n=7) mice were treated with 4% dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) (w/v) ad lib for 7 days. Animals were sacrificed upon achieving 20% weight loss. Body weights (mean body weight ± SD) are shown at days 0, 4 and 7 as per cent change from baseline (day 0 weight). (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves. (C) Per cent difference in colon length. (D) ‘Swiss-rolled’ colons stained with H&E. (E) Histological injury score using a multi-point scale as described in the Methods section. (F) Citrobacter rodentium-colitis model H&E stained sections. (G) Histological injury scores as described in the Methods section. (H) Colonic bacterial colonisation (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001).

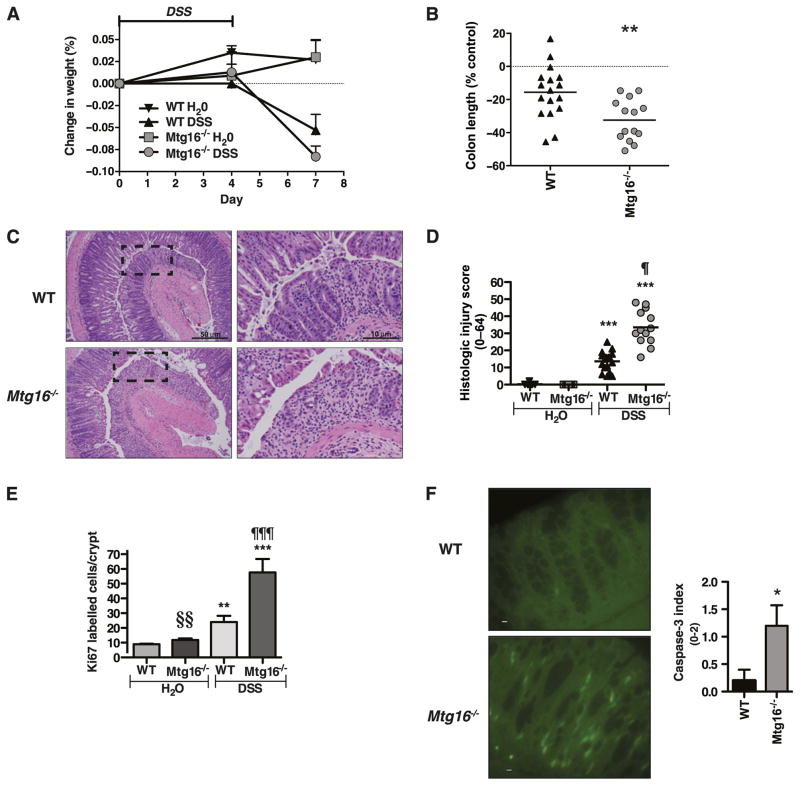

To determine whether these effects continue in the recovery phase we treated one group of Mtg16−/− or WT mice with 3% DSS for 4 days followed by immediate sacrifice and allowed another group to recover three additional days. There were no differences in weights, colon lengths or histological injury scores in the cohort of mice treated for 4 days (data not shown). In contrast, in the recovery phase group, Mtg16−/− mice exhibited accelerated weight loss (figure 4A), shorter colons (figure 4B) and more severe histological injury in the recovery phase (figure 4C, D). In response to injury, robust epithelial proliferation must occur to reconstitute epithelial barrier properties.8,18–20 Epithelial proliferation was augmented in the null epithelium (figure 4E); of note, this high rate likely was secondary to the severity of injury and the biological necessity of recapitulation of the epithelium to maintain homeostasis. In support of this, analysis for apoptosis at day 4 of DSS injury using caspase-3 indicated that apoptosis was increased in the Mtg16−/− colons (figure 4F). Collectively, these observations indicate that Mtg16 contributes to epithelial integrity after injury.

Figure 4.

MTG16 contributes to epithelial restitution after injury. Mtg16−/− (n=14) or WT (n=17) mice were treated with 3% dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) (w/v) or water ad lib for 4 days followed by recovery on water for 3 days prior to euthanising. (A) Body weights (mean body weight ± SD) are shown at days 0, 4 and 7 as per cent change from baseline (day 0 weight). (B) Per cent difference in colon length. (C) H&E stained representative sections of Mtg16−/− or WT Swiss-rolled colons. Images at right represent boxed area from 40× images at left. (D) Quantification of colonic injury represented as an aggregate histological injury score. (E) Ki67 immunohistochemistry. (F) Representative activated caspase-3 immunohistochemistry (left) after 4 days of 3% DSS treatment (Bar denotes 10 μM). Quantification of activated caspase-3 staining (right) (n=5 per genotype) (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001: DSS-treated compared with control (H20) mice, ¶p<0.05, ¶¶¶p<0.001: Mtg16−/− vs WT DSS, §§p<0.01: Mtg16−/− compared with WT control mice).

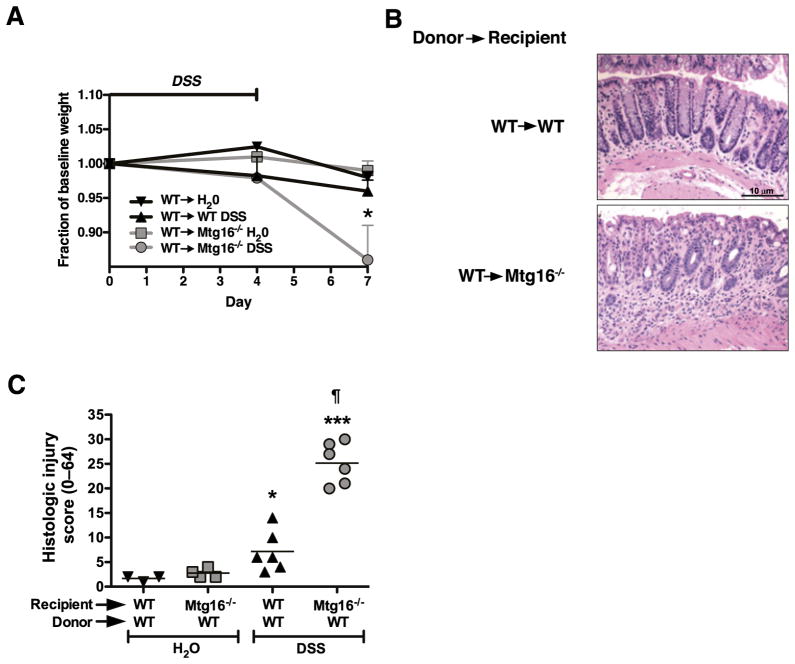

Adoptive transfer of WT marrow into Mtg16−/− mice fails to rescue the Mtg16−/− colonic injury phenotype

Because the Mtg16−/− mice have evidence for systemic haematological abnormalities (mild anaemia, shunting of erythroid lineages) and augmented immune activity in the unchallenged colon, we postulated that Mtg16 may function in a cell-autonomous fashion in the haematopoietic compartment in regulating immune responses to injury. To test this possibility, we replaced the marrow in lethally irradiated Mtg16−/− mice with WT marrow, allowed the animals to recover for 8 weeks and then subjected the mice to 4 days of 3% DSS followed by 3 days of recovery prior to sacrifice. Control animals, receiving similar doses of radiation, but without marrow transplantation, did not survive, ensuring that we had marrow sterilisation. Of note, the reciprocal transplant was not possible due to the inability of Mtg16−/− marrow to reconstitute haematopoiesis (data not shown).

Although Mtg16−/− mice have impaired haematopoiesis, WT marrow transplantation did not rescue Mtg16−/− mice from the DSS sensitive phenotype. Mtg16−/−/WTchimeras still exhibited more severe DSS induced injury in comparison with WT/WT mice having a histological injury index of 25.2 SD 1.7 versus 7.2 SD 1.7 (figure 5B,C p<0.001). In fact, the levels of injury and distribution pattern were comparable with non-transplanted Mtg16−/− mice treated with DSS, suggesting that Mtg16 is not acting in a haematopoietic cell-autonomous fashion in this model and implicates the lack of MTG16 in the epithelial or stromal elements as contributing to the injury phenotype.

Figure 5.

Adoptive transfer of WT marrow into Mtg16−/− mice is incapable of rescuing the Mtg16−/− colonic injury phenotype. Mtg16−/− (n=6) or WT (n=6) mice were lethally irradiated and rescued with isogenic WT marrow. Three months post-transplantation mice were treated with 3% dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) ad lib for 4 days followed by 3 days of recovery on water. Weights are shown in (A). H&E stained Swiss-rolled sections are shown in (B). Histological injury score was tallied using a multipoint scale21 and is presented in (C) (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001: DSS compared with Control, ¶ p<0.05: Mtg16−/− DSS compared with WT DSS).

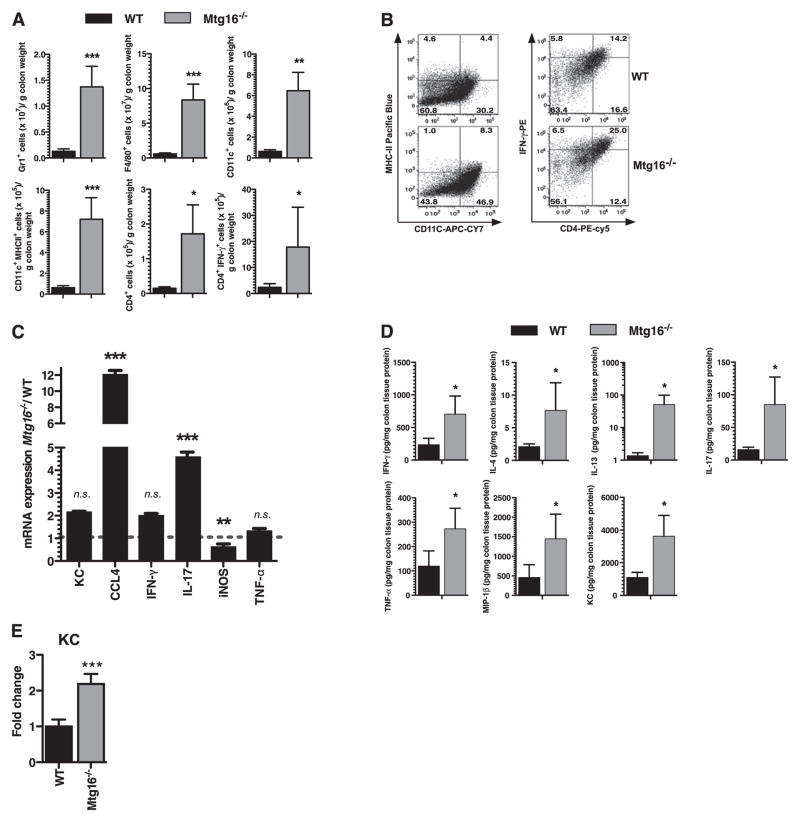

Hyperactive innate and adaptive immune responses in Mtg16−/− following DSS injury

Mtg16−/− mice at baseline have increased innate and adaptive immune signatures skewed towards Th1 responses. We next determined the composition of the immune cell infiltrate after epithelial injury in the mice treated with the DSS 4+3 injury/repair model (figure 6). Not surprisingly, there were marked increases in all inflammatory subsets in both WT and null mice after DSS injury. Of note, in comparison with WT infiltrates, the Mtg16−/− infiltrates were composed of significantly more Gr-1+ granulocytes (10.7-fold, p<0.001), F4/80+ macrophages (14.6-fold, p<0.001) and CD11c+ DCs (14.6-fold, p<0.01) as well as CD11c+;MHCII+ activated DCs (11.6-fold, p<0.001, figure 6A,B). Increases in adaptive immune responses were also seen with increased CD4 T cells and increased IFN-γ-producing CD4 cells with a further augmentation of IFN-γ production in CD4 cells. No differences were seen with the monocyte marker (CD11b) or in total T lymphocytes (CD3) or B lymphocytes (CD19, online supplementary figure 3A). Cytokine and chemokine characterisation using a multi-analyte bead array indicated significant increases in IFN-γ (threefold, p<0.05), IL-4 (3.7-fold, p<0.05), IL-13 (36.5-fold p<0.05), IL-17 (5.4-fold, p<0.05) and TNFα (2.3-fold, p<0.05), and the chemokines MIP-1β (3.2-fold, p<0.05) and KC (3.3-fold, p<0.05, figure 6D) indicating that Mtg16−/− mice have a broadly exacerbated adaptive immune response that include Th1, Th17 and Th2 alterations. No significant differences were seen in IL-12p40, IL-12p70, IL-1β, IL-6 or IL-10 (online supplementary figure 3B).

Figure 6.

Exacerbated innate and adaptive immune responses in Mtg16−/− mice following dextran sodium sulphate (DSS) injury. Mtg16−/− (n=8) or WT (n=8) mice treated with water or 3% DSS (w/v) according to our injury-repair model (4 days 3% DSS ad lib followed by 3 days of water recovery). (A) Flow cytometric analysis using haematopoietic lineage-specific antibodies from WT (n=8) or Mtg16−/− (n=8) colons. An unpaired two-tailed t test indicated that there was a significant increase in Gr1+, F4/80+, CD11c+, MHCII expressing CD11c+, CD4+ and IFN-γ expressing CD4+ cells in Mtg16−/− colons. (B) Representative cell plot histograms of MHCII expressing CD11c and IFN-γ expressing CD4 populations. (C) RNA expression levels measured by qRT-PCR on Mtg16−/− colons presented as fold change from WT (dashed line). Error bars represent SD, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001. (D) Multi-analyte profiling using the Luminex platform revealed increased INF-γ, IL-17, TNFα, IL-4, and IL-13 and chemokines MIP-1β and KC in Mtg16−/− colons. (E) Epithelial-specific KC mRNA expression levels (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; unidimensional ANOVA).

Since we observed increased IL-17, and IL-17 increases KC production via augmenting KC mRNA stability,22,23 we measured KC mRNA expression from isolated colonic epithelium and found it to be increased 2.1-fold (p<0.001, figure 6E). Hence increased recruitment of Gr-1+, F4/80+ and CD11c cells in Mtg16−/− colons could be attributed to increased epithelial production of chemokines such as KC. Collectively, these data indicate that Mtg16 modulates innate and adaptive immune responses. We postulate that the epithelial cells in Mtg16−/− mice release excessive chemokines in response to injury, leading to recruitment of innate and adaptive effector cells resulting in exacerbation of tissue injury.

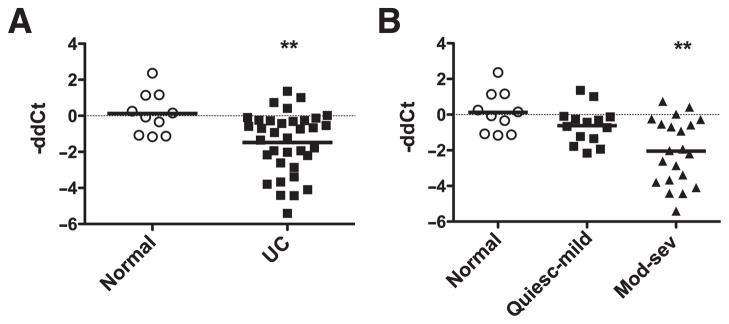

MTG16 levels are decreased in ulcerative colitis

Based on the above observations, we predicted that patients with ulcerative colitis would have decreased Mtg16 mRNA levels. We extracted RNA from colonic biopsies collected prospectively from normal controls or ulcerative colitis patients with varying degrees of disease activity based on histological analysis. There was no difference in use of 5-ASA, corticosteroids, immunomodulators or biologics between the colitis groups (data not shown). qRT-PCR was performed and ddCt calculations between normal and disease samples revealed a 2.8-fold reduction of Mtg16 mRNA levels in ulcerative colitis samples (figure 7A, p=0.01 187). Subset analysis indicated that this was mainly due to reduction in Mtg16 mRNA expression in patients with moderate and severe ulcerative colitis, in which we observed a 4.2-fold decrease in gene expression compared with control samples (figure 7B, p=0.00 537).

Figure 7.

MTG16 is underexpressed in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis (UC). Mtg16 mRNA levels were determined using qRT-PCR on UC biopsy specimens. (A) Mtg16 mRNA levels expressed as negative ddCt in normal (n=10) versus UC (n=35) samples. This represents a 2.8-fold decrease in expression. (B) Subset analysis of Mtg16 expression in UC (normal n=10, quiescent-mild n=14, moderate-severe n=21). This represents a 4.2-fold decrease in Mtg16 mRNA levels in moderate-severe UC samples. **p=0.005, Wilcoxon rank sum, in comparison with control samples (normal).

DISCUSSION

In the current report we show that Mtg16 is required for epithelial integrity after DSS-mediated injury. At baseline, Mtg16−/− mice have increased epithelial proliferation and permeability with more DCs and higher IFN-γ levels due to increased numbers of CD4;IFN-γ-producing cells. This suggested that both innate and adaptive immunity were primed, perhaps because of altered permeability in Mtg16−/− colons. In response to DSS injury there was a marked increase in innate and adaptive immune cells with an associated elevation in a broad number of cytokine and chemokines, suggesting that in the absence of Mtg16 there is a global loss of immunoregulation after injury. This was not due to haematopoietic cell defects as transplanting WT bone marrow into Mtg16−/− recipients was unable to rescue the colonic injury phenotype. The defect is likely multifactorial, but at least partially due to de-repression of cytokines and chemokines derived from the epithelium and/or stroma in the Mtg16−/− colon, thus magnifying recruitment in response to injury.

C rodentium induces an infectious colitis which is characterised by crypt hyperplasia, mucosal injury and production of TNFα, IL-12 and IFN-γ indicating a Th1 response.24 More recent work indicates that C rodentium also induces Th17 type responses.25,26 Not surprisingly, given the skewing of baseline cytokine production towards a Th1 phenotype, Mtg16−/− mice displayed more severe colitis and increased bacterial colonisation when this model was employed.

Mtgr1−/− mice also exhibit an increase in colitis in the DSS model. This effect is likely due to the progressive depletion of the secretory lineage (goblet cells, paneth cells and enteroendocrine cells) coupled with an impact on colonocyte survival.9 In contrast, Mtg16−/− mice have normal secretory lineage allocation and the defect is likely due to a fundamental defect in epithelial integrity as a result of increased apoptosis after DSS injury and to a predisposition to an increased immune cell response. Specifically, there is an increase in DCs and CD4;IFN-γ expressing T cells at baseline, and a broad increase in both innate and adaptive immune responses in mice exposed to DSS.

All three mammalian MTG family members share sequence homology clustering within four highly conserved regions termed nervy homology regions (NHR).3 Of note, these domains have up to 98% homology between the three mammalian family members, and mapping a particular function to a domain in one family member often can be translated to all family members.3 Thus, the lack of compensation for the inactivation of Mtg16 by higher Mtgr1 or Mtg8 expression is striking given that all three family members are expressed in the gut epithelium.8 These results suggest that each family member has individual activities within the epithelium. Given the similarity within the NHR domains, the individual responses probably are derived from the inter-NHR regions. While the possibility exists that the Mtgr1−/− injury phenotype was secondary to secretory lineage depletion,9 the Mtg16−/− mice have normal secretory lineage allocations, suggesting that the DSS sensitivity observed in both knockouts is not necessarily dependent on the loss of the secretory lineage.

It has been proposed that DSS induces colitis via increasing epithelial permeability.27,28 Tight junction protein zona-occludens-1 levels are reduced within 1 day of initiating treatment with reduced permeability following on day 3, and finally inflammation developing at day 5.29 We note that in the unperturbed state Mtg16−/− mice have increased epithelial permeability and pronounced immune infiltrates. This is likely another alteration contributing towards the injury phenotype. We speculate that the ‘leaky’ epithelium results in inappropriate submucosal–luminal interactions producing primed submucosal immunity and, after epithelial injury, results in an exaggerated immune response. In support of this, we noted increased IFN-γ levels at baseline and, after injury, increase in a broad spectrum of chemokines and cytokines (figure 6A,D).

We also observed increased colonic DC and CD4 cells both at baseline and after injury, potentially in response to luminal microbial translocation due to epithelial incompetency. Mucosal DCs program T cell reactivity and DCs can initiate innate or adaptive immune responses.30 There are conflicting data regarding DCs in inflammatory bowel disease, with likely model dependencies. Chronic colitis in IL10-null mice is improved by depletion of both macrophages and DCs31 and anti-CD11b treatment blocks DC emigration into the colon protecting rats from both TNBS induced colitis and mice with T cell transfer induced colitis. In contrast, resident DCs can suppress DSS induced colitis that may be mediated via regulated production of IL-6.32 Nevertheless, elevated numbers of DCs in Mtg16−/− colons indicate imbalances in innate immunity, potentially priming the intestine for abnormal immune responses to injury. Indeed, while the total number of CD4 cells is similar between genotypes, the fraction of IFN-γ-producing CD4 cells was increased 17-fold in the Mtg16−/− mice. In support of this, IFN-γ expression levels in CD4 cells were also increased threefold (figure 2B,C).

In conclusion, our data suggest that Mtg16 plays multiple roles in the gut, appearing to regulate colonic permeability, potentially directly contributing to or exacerbating the adaptive and innate immune abnormalities seen in these mice, which, upon epithelial compromise, result in augmented colonic injury. Our data suggest that MTG16 regulates inflammatory recruitment in response to injury. Last, patients with ulcerative colitis have decreased MTG16 expression, suggesting that the observations made in our animal model may be translatable to patients with inflammatory bowel disease, as the impaired expression may represent a contributing factor to the aetiopathogenesis of ulcerative colitis.

Supplementary Material

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Myeloid translocation gene-16 (MTG16) is a transcriptional corepressor originally identified in chromosomal translocations in acute myeloid leukaemia and controls haematopoietic stem cell fate programmes.

Mtg16−/− mice have altered haematopoietic lineage allocation with a skewing towards granulocyte/macrophage lineages.

Epithelial wound healing and repair abnormalities contribute to inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis.

What are the new findings?

Mtg16−/− mice display increased colonic proliferation, intestinal permeability and colonic Gr1+, and CD4+;IFN-γ+ secreting T cells. The latter indicates skewing towards Th1 responses.

Mtg16−/− mice develop more severe colitis after intestinal injury induced by dextran sodium sulphate or after Citrobacter rodentium infection.

Ulcerative colitis patients have lower levels of Mtg16 expression, which correlate with severity of histological injury.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The data form the basis for a clinical understanding that MTG16 contributes to epithelial injury responses in the colon. The MTG16 axis may represent a novel therapeutic target for intervention in inflammatory bowel disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Williams, Wilson, Hiebert and Zinkel laboratories for thoughtful discussions regarding this research project. We also thank Frank Revetta for histological support.

Funding Supported by the National Institutes of Health grants DK080221 (CSW), CA64140 (SWH), HL088494 (SWH), P50CA095103 (MKW), AT004821 (KTW), AT004821-S1 (KTW), DK053620 (KTW), a Merit Review Grant from the Office of Medical Research, Department of Veterans Affairs (KTW and CSW) and ACS-RSG 116552 (CSW). Core Services performed through Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Digestive Disease Research Center supported by NIH grant P30DK058404 (RMP) and the Vanderbilt Ingram Cancer Center shared resources P30CA068485 as well as the National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1 RR024975-01, and is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, Grant 2 UL1 TR000445-06.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Contributors CSW, SSZ, KTW, RMP and SWH: Study concept design, funding, data interpretation, drafting of manuscript and critical revision. AMB, RC, XC, EM, MKW, ADW, MAF, CTB, MMA, LAC, KS, MBP, YAC and SNH: Data acquisition and analysis. DAS and DBB: Material support.

Disclosure DAS: Abbott: grant support, consultant; UCB: grant support, consultant; BrainTree Labs: consultant.

References

- 1.Davis JN, Williams BJ, Herron JT, et al. ETO-2, a new member of the ETO-family of nuclear proteins. Oncogene. 1999;18:1375–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kitabayashi I, Ida K, Morohoshi F, et al. The AML1-MTG8 leukemic fusion protein forms a complex with a novel member of the MTG8(ETO/CDR) family, MTGR1. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:846–58. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis JN, McGhee L, Meyers S, et al. The ETO (MTG8) gene family. Gene. 2003;303:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(02)01172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calabi F, Cilli V. CBFA2T1, a gene rearranged in human leukemia, is a member of a multigene family. Genomics. 1998;52:332–41. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamagata T, Maki K, Mitani K. Runx1/AML1 in normal and abnormal hematopoiesis. Int J Hematol. 2005;82:1–8. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.05075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amann JM, Nip J, Strom DK, et al. ETO, a target of t(8;21) in acute leukemia, makes distinct contacts with multiple histone deacetylases and binds mSin3A through its oligomerization domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:6470–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.19.6470-6483.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moore AC, Amann JM, Williams CS, et al. Myeloid translocation gene family members associate with T-cell factors (TCFs) and influence TCF-dependent transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:977–87. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01242-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinez JA, Williams CS, Amann JM, et al. Deletion of Mtgr1 sensitizes the colonic epithelium to dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:579–88. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amann JM, Chyla BJ, Ellis TC, et al. Mtgr1 is a transcriptional corepressor that is required for maintenance of the secretory cell lineage in the small intestine. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9576–85. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9576-9585.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calabi F, Pannell R, Pavloska G. Gene targeting reveals a crucial role for MTG8 in the gut. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5658–66. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.16.5658-5666.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chyla BJ, Moreno-Miralles I, Steapleton MA, et al. Deletion of Mtg16, a target of the t(16;21), alters hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation and lineage allocation. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6234–47. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00404-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh K, Chaturvedi R, Barry DP, et al. The apolipoprotein E-mimetic peptide COG112 inhibits NF-kappaB signaling, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and disease activity in murine models of colitis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3839–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.176719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizoguchi E, Xavier RJ, Reinecker HC, et al. Colonic epithelial functional phenotype varies with type and phase of experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:148–61. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00665-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furuta GT, Turner JR, Taylor CT, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-dependent induction of intestinal trefoil factor protects barrier function during hypoxia. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1027–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mashimo H, Wu DC, Podolsky DK, et al. Impaired defense of intestinal mucosa in mice lacking intestinal trefoil factor. Science. 1996;274:262–5. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5285.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson DL, Ma C, Bergstrom KS, et al. MyD88 signalling plays a critical role in host defence by controlling pathogen burden and promoting epithelial cell homeostasis during Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:618–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee AS, Gibson DL, Zhang Y, et al. Gut barrier disruption by an enteric bacterial pathogen accelerates insulitis in NOD mice. Diabetologia. 2010;53:741–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1626-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukata M, Chen A, Klepper A, et al. Cox-2 is regulated by toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4) signaling: role in proliferation and apoptosis in the intestine. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:862–77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukata M, Michelsen KS, Eri R, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 is required for intestinal response to epithelial injury and limiting bacterial translocation in a murine model of acute colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G1055–65. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00328.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelblum KL, Washington MK, Koyama T, et al. Raf protects against colitis by promoting mouse colon epithelial cell survival through NF-kappaB. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:539–51. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dieleman LA, Palmen MJ, Akol H, et al. Chronic experimental colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium (DSS) is characterized by Th1 and Th2 cytokines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1998;114:385–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1998.00728.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Datta S, Novotny M, Pavicic PG, Jr, et al. IL-17 regulates CXCL1 mRNA stability via an AUUUA/tristetraprolin-independent sequence. J Immunol. 2010;184:1484–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hartupee J, Liu C, Novotny M, et al. IL-17 enhances chemokine gene expression through mRNA stabilization. J Immunol. 2007;179:4135–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins LM, Frankel G, Douce G, et al. Citrobacter rodentium infection in mice elicits a mucosal Th1 cytokine response and lesions similar to those in murine inflammatory bowel disease. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3031–9. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3031-3039.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–32. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mangan PR, Harrington LE, O’Quinn DB, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta induces development of the T(H)17 lineage. Nature. 2006;441:231–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitajima S, Takuma S, Morimoto M. Changes in colonic mucosal permeability in mouse colitis induced with dextran sulfate sodium. Exp Anim. 1999;48:137–43. doi: 10.1538/expanim.48.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitajima S, Takuma S, Morimoto M. Tissue distribution of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in the acute phase of murine DSS-induced colitis. J Vet Med Sci. 1999;61:67–70. doi: 10.1292/jvms.61.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poritz LS, Garver KI, Green C, et al. Loss of the tight junction protein ZO-1 in dextran sulfate sodium induced colitis. J Surg Res. 2007;140:12–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elson CO, Cong Y, McCracken VJ, et al. Experimental models of inflammatory bowel disease reveal innate, adaptive, and regulatory mechanisms of host dialogue with the microbiota. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:260–76. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watanabe N, Ikuta K, Okazaki K, et al. Elimination of local macrophages in intestine prevents chronic colitis in interleukin-10-deficient mice. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:408–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1021960401290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qualls JE, Tuna H, Kaplan AM, et al. Suppression of experimental colitis in mice by CD11c+ dendritic cells. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:236–47. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.