Abstract

Serine hydrolases play critical roles in many biological processes, and several are targets of approved drugs for indications such as type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and infectious disease. Despite this, most of the 200+ human serine hydrolases remain poorly characterized with respect to their physiological substrates and functions, and the vast majority lack selective, in vivo-active inhibitors. Here, we review the current state of pharmacology for mammalian serine hydrolases, including marketed drugs, compounds under clinical investigation, and selective inhibitors emerging from academic probe development efforts. We also highlight recent methodological advances that have accelerated the rate of inhibitor discovery and optimization for serine hydrolases, which we anticipate will aid in their biological characterization and, in some cases, therapeutic validation.

Introduction

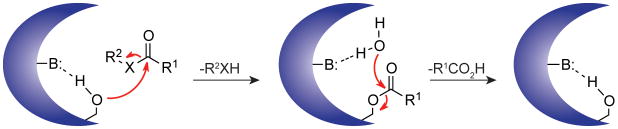

Serine hydrolases are one of the largest and most diverse classes of enzymes found in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. These enzymes, which include lipases, (thio)esterases, amidases, peptidases, and proteases, all utilize a base-activated serine nucleophile to cleave amide or (thio)ester bonds in substrates via a covalent acyl-enzyme intermediate (Fig. 1). In mammals, serine hydrolases represent ~1% of all proteins and play vital roles in many (patho)physiological processes, including blood clotting1, digestion2, nervous system signaling3, inflammation4, and cancer5–7. Serine hydrolases also perform critical functions in bacteria and viruses, where they contribute to pathogen life cycle8, virulence9, and drug resistance10.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the serine hydrolase catalytic cycle.

A base-activated serine nucleophile attacks the carbonyl carbon of the scissile bond, forming a covalent intermediate and releasing the first reaction product. A water molecule then hydrolyzes the covalent intermediate to release the second reaction product and regenerate the active enzyme. X= N, O, or S.

The widespread biological significance of serine hydrolases has motivated many academic and industrial groups to develop inhibitors for enzymes from this class, both for use as chemical probes to study enzyme function and as potentially new therapeutic agents. Four general strategies have been successfully employed: 1) mining natural products (proteins, polysaccharides, and small-molecules), 2) converting endogenous substrates into inhibitors, 3) screening large compound libraries and optimizing lead scaffolds, and 4) tailoring compounds containing mechanism-based electrophiles, including carbamates11, 12, ureas 13, 14, activated ketones15, and lactones/lactams16, 17, that covalently react with the active-site serine nucleophile. Although the last approach overlaps with the other strategies—e.g., electrophiles are intrinsic in some natural product scaffolds18, 19 and have been extensively employed as “warheads” on enzyme substrates and/or products to convert them into inhibitors20, 21—screening of “hydrolase-directed” electrophile libraries broadly against serine hydrolases has emerged as a particularly fruitful independent approach for the identification of inhibitors11, 14. Together, these efforts have yielded a diverse array of pharmacological tools, including proteins, peptides, polysaccharides, and small-molecules, that inhibit serine hydrolases with good selectivity, and several of these agents have been approved for clinical use to treat diseases such a type 2 diabetes, obesity, blood-clotting disorders, Alzheimer’s disease, and bacterial and viral infections [Table 1 and Supplementary information S1 (table)].

Table 1.

Human serine hydrolase inhibitors approved for clinical use.

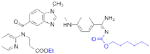

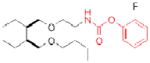

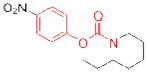

| Target | Compound | Structure | Company | Ref(s) | Indication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

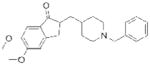

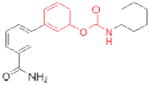

| ACHE | Rivastigmine (Exelon) |

|

Novartis | 29 | Alzheimer’s - associated dementia |

| Donepezil (Aricept) |

|

Eisai | 69 | ||

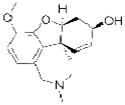

| Galantamine (Razadyne) |

|

Ortho-McNeil Janssen | 72 | ||

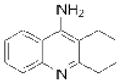

| Tacrine (Cognex) |

|

Shionogi | 66 | ||

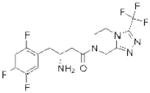

| DPP4 | Sitagliptin (Januvia) |

|

Merck | 93 | Type II diabetes |

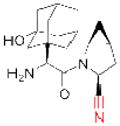

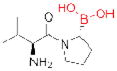

| Saxagliptin (Onglyza) |

|

Bristol Myers Squibb | 92 | ||

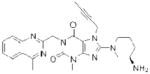

| Linagliptin (Tradjenta) |

|

Boehringer Ingelheim | 94 | ||

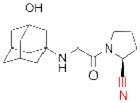

| Vildagliptin* (Zomelis) |

|

Novartis | 31 | ||

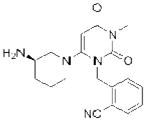

| Alogliptin* (Nesina) |

|

Takeda | 86 | ||

| Pancreatic/ gastric lipases | Orlistat (Xenical;Alli) |

|

Roche; GlaxoSmithKline | 19, 32 | Obesity |

| Thrombin | Dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) |

|

Boehringer Ingelheim | 46, 47 | Thrombosis |

| Argatroban (Novastan) |

|

GlaxoSmithKline Mitsubishi Pharma | 42 | ||

| Factor Xa | Rivaroxaban (Xarelto) |

|

Bayer | 54, 59 | Thrombosis |

| Human neutrophil elastase | Sivelestat* (Elaspol) |

|

Ono | 33 | Respiratory disease |

The electrophilic moieties of each compound, if applicable, are colored red. The prodrug portions of dabigatran etexilate are colored blue.

Not yet approved in the United States.

Despite these advances, the vast majority of eukaryotic and prokaryotic serine hydrolases still lack selective inhibitors. Further, many serine hydrolases, including some that have been genetically linked to human disease, remain uncharacterized with respect to their physiologic substrates and functions. In this Review, we survey the current pharmacological toolkit and therapeutic potential for human serine hydrolases, giving special attention to modern chemoproteomic methods that have quickened the pace of inhibitor discovery and optimization. We also discuss the challenges that must be overcome to create selective inhibitors for the vast majority, if not all mammalian serine hydrolases, and highlight how they are being met by advances in screening and the development of classes of compounds that show preferential capacity to inactivate serine hydrolases.

The human serine hydrolases

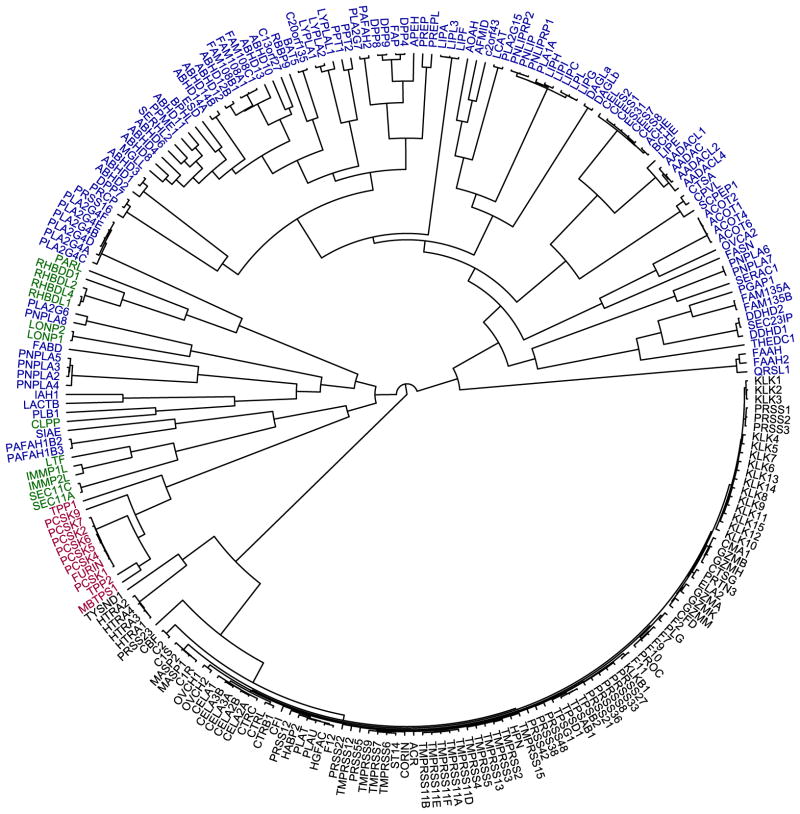

There are ~240 human serine hydrolases, which can be divided into two near-equal-sized subgroups – the serine proteases (~125 members) and the ‘metabolic’ serine hydrolases (~115 members) (Fig. 2).6 The vast majority of serine proteases, which primarily cleave peptide bonds in proteins, have chymotrypsin-like or subtilisin-like folds (Fig. 2, black and red enzymes, respectively), with a catalytic serine nucleophile activated by participation in a catalytic triad with conserved histidine and aspartic acid residues.22 Serine proteases typically exist as inactive precursors (i.e., zymogens), which are activated by limited proteolysis upon specific biological stimuli and subsequently inactivated by endogenous protein inhibitors.22, 23 These enzymes include the well studied digestive protease trypsin and the critical blood clotting mediators thrombin and activated factor Xa (FXa).

Figure 2. The human serine hydrolases.

A dendrogram showing the ~240 predicted human serine hydrolases with branch length depicting sequence relatedness. The metabolic serine hydrolases are colored blue. The remaining enzymes are serine proteases, with chymotrypsin-like enzymes colored black, subtilisin-like enzymes colored red, and other, smaller serine protease clans colored green.

The ‘metabolic’ serine hydrolases (Fig. 2) are comprised of a wide range of lipases, peptidases, esterases, thioesterases, and amidases that hydrolyze small-molecules, peptides, or post-translational (thio)ester protein modifications.6 Consistent with their diverse substrate repertoire, the metabolic serine hydrolases are comprised of a much more structurally diverse group of enzymes than the serine proteases (Fig. 2, note branch length). The majority (>60%) of metabolic serine hydrolases have an α/β-hydrolase fold and Ser-His-Asp catalytic triad, but this sub-family also includes several structurally and mechanistically distinct enzyme clades such as the patatin domain-containing lipases24 and the amidase signature enzymes25, 26, which use Ser-Asp dyads and Ser-Ser-Lys triads for catalysis, respectively. Although several members of the metabolic serine hydrolase family have been extensively characterized, including acetylcholinesterase (ACHE), fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH), and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4), the majority are still unannotated with respect to their physiological substrates and functions.6

Clinically approved inhibitors of human serine hydrolases

Small-molecule inhibitors have been clinically approved for six distinct human serine hydrolase targets, four of which are described below (Table 1). As several of these compounds are not perfectly selective for a single enzyme, and at least one, orlistat, is thought to derive therapeutic benefit from inhibiting several related enzymes27, the actual number of human serine hydrolases targeted by commercial drugs is likely higher than six. Interestingly, despite the pharmaceutical industry’s perceived aversion to developing therapeutics that form covalent bonds with protein targets28, five of these drugs, rivastigmine29, saxagliptin30, vildagliptin31, orlistat32, and sivelestat33, 34, contain electrophilic chemical groups that interact covalently with their target’s active-site serine nucleophile. Additional examples of electrophilic drugs that target serine hydrolases include the β-lactam antibiotics35, which inhibit bacterial transpeptidase and β-lactamase enzymes, and the recently approved hepatitis C virus (HCV) drugs boceprevir and telaprevir36, which are α-keto amides that inhibit the HCV NS3 protease [Supplementary information S1 (table)]. In addition to these small-molecule inhibitors, several large biomolecules and their derivatives (proteins, peptides, polysaccharides) that target serine hydrolases, such as thrombin, are either in clinical development or have been approved for clinical use37. However, due to space limitations, we will focus on small-molecule inhibitors of human serine hydrolases in this Review.

Inhibitors of serine proteases involved in coagulation

Venous and arterial thromboembolic diseases, which are characterized by occlusion of blood vessels by thrombi (i.e., aggregations of platelets, fibrin, and cells), are a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide37. Several serine proteases play central roles in the blood coagulation pathway, where sequential activation of protease zymogens results in the rapid formation of insoluble fibrin blood clots1, 38, and have long been the main targets of anticoagulant drug development efforts. For the past half-century, heparins and vitamin K antagonists (e.g. warfarin), both of which indirectly inactivate several proteases in the cascade, have been the two major anticoagulant drug classes. However, these agents have important clinical drawbacks; heparins require parenteral administration due to their large size, and warfarin, although orally available, has a narrow therapeutic window, many food-drug interactions, and requires frequent monitoring37. More recent research efforts have focused on the development of selective and orally available small-molecules that directly block one of two key coagulation proteases, thrombin (also known as factor IIa) and activated factor Xa (FXa).

Thrombin, the final protease in the clotting cascade, cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, potently activates platelets, and indirectly activates itself through a feedback loop39. Injectable direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) have been known for many years; the leech salivary peptide hirudin40, the hirudin-derivative bivalirudin41, and the small-molecule argatroban42 (Table 1) are all clinically approved DTI anticoagulants43. The first orally available small-molecule DTI, ximelagatran (Exanta; AstraZeneca) was developed starting from a peptide scaffold that mimicked the thrombin substrate fibrinogen39. Ximelagatran, however, exhibited serious liver toxicity, and consequently was not approved in the United States and was withdrawn in Europe in 200644. The next attempt to develop an orally available DTI originated from an X-ray crystal structure of the peptide-like inhibitor NAPAP in complex with bovine thrombin45. Replacement of the central NAPAP glycine residue with a more rigid isostere and subsequent optimization resulted in the reversible inhibitor dabigatran, which exhibited excellent anticoagulant activity in human blood with good selectivity for thrombin over related serine proteases46. However, dabigatran was not orally bioavailable, likely due to a highly basic amidine residue that was included to mimic the fibrinogen substrate. In order to achieve oral bioavailability, dabigatran was masked as a double prodrug (Table 1) (Dabigatran etexilate; Pradaxa; Boehringer Ingelheim), which is hydrolyzed to release dabigatran in vivo47. Importantly, dabigatran etexilate did not show any evidence of liver toxicity48, and has recently gained regulatory approval worldwide.

FXa, the other major protease target for anticoagulant development, cleaves prothrombin into active thrombin49. Potent parenteral FXa inhibitors have been known for decades, including the polypeptides antistasin50, 51 and the tick anticoagulant peptide (TAP)52. These agents, together with more recently introduced pentasaccharide fondaparinux (Arixtra; GlaxoSmithKline)53, an analog of the heparin core that selectively inhibits FXa but not thrombin, were critical in elucidating the role of FXa in thrombosis and validating selective FXa inhibition as a therapeutic strategy54. Initial small-molecule FXa inhibitors all contained amidine residues that served as prothrombin mimetics55, 56. As was observed with dabigatran, this highly basic group, although critical for potency, contributed to poor oral bioavailability57, 58. Bayer opted instead to screen a large (~200,000) library of compounds to identify a novel inhibitor scaffold59. From a lead with modest micromolar potency and structure-activity knowledge emanating from previous efforts, this team developed the highly potent, reversible FXa inhibitor rivaroxaban (Xarelto; Bayer HealthCare)54, 59. Rivaroxaban became the first selective small-molecule inhibitor of FXa approved for clinical use in 200854. Several additional small-molecule inhibitors of both thrombin and FXa are currently in clinical development and have been recently reviewed60.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors to treat Alzheimer’s associated dementia

Acetylcholinesterase (ACHE) is a metabolic serine hydrolase that cleaves and inactivates the neurotransmitter acetylcholine61. More than 30 years ago, a decrease in cholinergic signaling was first observed in patients with Alzheimer’s disease62–64, leading to the hypothesis that a loss in cholinergic neurotransmission contributed to the decline in cognitive function in these patients65. Consequently, it was proposed that increasing acetylcholine levels by inhibiting ACHE could alleviate symptoms of this disease. This premise has been validated clinically, and three ACHE inhibitors are currently used for the treatment of Alzheimer’s associated dementia (Table 1). A fourth inhibitor, tacrine (Cognex; Shionogi), is approved but not recommended for use due to poor bioavailability and toxicity66. Essential to the successful use of these drugs is a graduated dosing regimen that avoids overt cholinergic toxicity67, such as that observed with large doses of organophosphorus nerve agents and insecticides that potently, but nonselectively inhibit ACHE68.

The three ACHE inhibitors in clinical use have notably different origins. Only one of these compounds, donepezil (Aricept; Eisai), is entirely synthetic, a result of derivatization of a scaffold identified from “blind” compound screening69. Donepezil reversibly inhibits ACHE, and has the highest selectivity (>1,000 fold) of the approved compounds for ACHE over the related serine hydrolase butyrylcholinesterase (BCHE)70, 71. Galantamine (Razadyne; Ortho-McNeil Janssen) is a natural product alkaloid first isolated in 1952 from the bulbs of the Caucasian snowdrop Galanthus woronowi 72. Like donepezil, galantamine is a reversible inhibitor, but has a more modest 50-fold selectivity for ACHE over BCHE73, 74. The third approved compound, rivastigmine (Exelon; Novartis), is an optimized version of physostigmine, a natural product alkaloid with cholinergic activity75, with improved selectivity for the brain isoform of ACHE over peripheral ACHE and BCHE76. Rivastigmine, like physostigmine, contains an aryl carbamate group that acts as a slowly turned over ACHE substrate, effectively leading to the irreversible inactivation of the enzyme29. Following on the success of rivastigmine, carbamates have emerged as a versatile chemotype for serine hydrolase inhibitors, as embedding this tempered reactive group into various structural scaffolds has generated selective inhibitors for a diverse number of serine hydrolases11, 77, 78, as described in more detail below.

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors for type 2 diabetes

Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) is a serine peptidase that cleaves N-terminal dipeptides from a variety of polypeptides that contain a proline or an alanine residue at the penultimate position79. Prominent among DPP-4 substrates are the incretins glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), which are released from the gut after food intake to promote insulin secretion and improve pancreatic β cell function80–84. Inhibition of DPP-4 prolongs the beneficial actions of GLP-1 and GIP, designating this enzyme as a therapeutic target for the treatment type 2 diabetes85.

Since 2007, five DPP-4 inhibitors have been approved for clinical use (Table 1), although vildagliptin31 (Zomelis; Novartis) and alogliptin86 (Nesina; Takeda) have not been approved in the United States. The earliest reported DPP-4 inhibitors were proline (or alanine)-based dipeptides (i.e., analogs of DPP-4 cleavage products) bearing chemical warheads, including boronic acids21, diphenyl phosphonates87, and nitriles20. Appropriately positioned nitrile groups, in particular, which form covalent reversible bonds with the serine nucleophile of DPP-4 to give high affinity binding30, 88, 89, resulted in selective and orally bioavailable compounds. These lead compounds were ultimately optimized to give vildagliptin31, 90 and saxagliptin 91, 92 (Onglyza; Bristol Myers Squibb). Sitagliptin93 (Januvia; Merck) and linagliptin94 (Tradjenta; Boehringer Ingelheim), in contrast, were both optimized from novel structures—a β-amino acid scaffold95 and xanthene-based scaffold94, respectively—identified from screening compound libraries. Finally, alogliptin emerged from medicinal chemistry efforts around a quinazolinone scaffold predicted to inhibit the active-site of DPP-4 by structure-based design86. Sitagliptin, linagliptin, and alogliptin inhibit DPP-4 through non-covalent, reversible mechanisms.

Human serine hydrolases with emerging therapeutic potential

Many additional members of the serine hydrolase class have been implicated in disease, and inhibitors for several of these targets are in clinical development (Table 2). For example, fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) inactivates a large class of amidated lipid transmitters, including the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide96. Genetic deletion or chemical inactivation of FAAH in rodents increases the levels of anandamide and related fatty acid amides to produce analgesia, anti-inflammation, anxiolysis, and anti-depression without the psychotropic side effects typically observed with direct cannabinoid receptor (CB1) agonists77, 97, 98. Recently, a high-throughput screen of the Pfizer chemical library uncovered a novel urea-containing FAAH inhibitor, which irreversibly inactivates the enzyme by covalently modifying FAAH’s active-site serine99. The subsequent optimization of this scaffold resulted in the discovery of PF-04457845 (Table 2)13, a urea with exceptional selectivity for FAAH over other serine hydrolases and excellent pharmacokinetic properties in rats and dogs. The oral administration of PF-04457845 at 0.1 mg/kg exhibited similar antihyperalgesic effects as naproxen at 10 mg/kg in a rat model of inflammatory pain, and has since entered clinical trials.

Table 2.

Examples of serine hydrolase targets and lead inhibitors with potential therapeutic value.

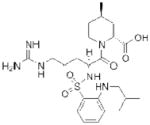

| Target | Compound (Company, if applicable) | Structure | Ref(s) | Potential Indication | Developmen t Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

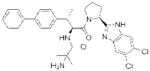

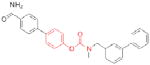

| FAAH | OL-135 |

|

184 | inflammatory pain; nervous system disorders | preclinical |

| URB597 (Kadmus Pharmaceuticals) |

|

77 | preclinical | ||

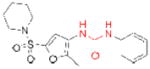

| PF-04457845 (Pfizer) |

|

13 | Phase II | ||

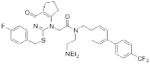

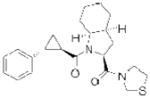

| FAP/ dipeptidyl peptidases | PT-100 (Point Therapeutics) |

|

143, 144 | cancer | Phase III (on hold) |

| LIPG | ‘Sulfonylfuran urea 1’ (GlaxoSmithKline) |

|

121 | cardiovascular disease | preclinical |

| PLA2G7 | Darapladib (GlaxoSmithKline) |

|

104 | atherosclerosis | Phase III |

| PRCP | ‘Compound 8o’ (Merck) |

|

109 | obesity | preclinical |

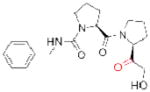

| PREP | S 17092 |

|

127 | cognitive deficits | preclinical |

| JTP-4819 (Japan Tobacco) |

|

126 | preclinical | ||

| TGH | GR148672X (GlaxoSmithKline) |

|

115 | hypertriglycerid- emia | preclinical |

The electrophilic moieties of each compound, if applicable, are colored red.

A second example of an emerging drug target in the serine hydrolase class is PLA2G7 (or Lp-PLA2), a calcium-independent phospholipase A2 principally secreted by leukocytes and associated with circulating low density lipoprotein (LDL)100. Elevated levels of PLA2G7 were discovered to strongly correlate with an increased risk of coronary heart disease, suggesting a potential role for this enzyme in atherogenesis101. PLA2G7 can hydrolyze polar phospholipids in oxidized LDL to generate two key pro-inflammatory mediators, lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC) and oxidized nonesterified fatty acids (NEFAs)102, 103. LPC and oxidized NEFAs have been implicated in the development of atherosclerosis through several mechanisms, including homing of inflammatory cells and induction of apoptosis100. To investigate the biology and therapeutic potential of PLA2G7, GlaxoSmithKline optimized a selective, picomolar PLA2G7 inhibitor, darapladib (Table 2)104, from an initial micromolar HTS screening hit105. Darapladib blocked LPC and NEFA production in oxidized LDL103 and significantly decreased coronary atherosclerotic plaque development in a diabetic and hyperchloesterolemic swine model through an anti-inflammatory mechanism independent of cholesterol106. Darapladib is currently being evaluated in Phase III clinical trials.

More preliminary studies using gene knockouts, lead chemical inhibitors, and protein and gene expression profiling have implicated other serine hydrolases as being of potential therapeutic importance. For example, mice lacking prolylcarboxypeptidase (PRCP), which cleaves C-terminal amino acids after proline in bioactive peptides, including angiotensin II and III107, have reduced body weight, food intake, and fat mass, designating PRCP as a potential target for obesity108. Merck has reported initial attempts to develop PRCP inhibitors109, 110, the first of which, ‘compound 8o’(Table 2), reversibly blocked PRCP activity with nanomolar potency and high selectivity over a panel of related serine peptidases109. Encouragingly, ‘compound 8o’ significantly reduced food intake, body weight, and fat mass of wild-type mice compared with PRCP−/− mice. However, a recently reported second generation PRCP inhibitor reduced body weight and food intake similarly in wild-type and PRCP–/– mice110, indicating the effects, at least in this case, were independent of PRCP. The authors speculate that ‘compound 8o’ may achieve higher levels of peripheral and/or central PRCP engagement than the second generation compound, and are currently pursuing more structurally diverse inhibitors with improved bioavailability to further evaluate this premise.

In addition, murine knockouts of three serine triglyceride (TG) hydrolases, triacylglycerol hydrolase (TGH), adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), and endothelial lipase (LIPG or EL), have implicated these enzymes as possible therapeutic targets for hypertriglyceridemia, cancer-associated cachexia, and cardiovascular disease, respectively. TGH, also referred to as carboxylesterase 3 (CES3) in mice and carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) in humans, can cleave TG stores in hepatocytes, which, after lipolysis, can serve as substrates for the assembly of apolipoprotein B (apoB)-containing very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) particles111–113. Excitingly, TGH–/– mice have significantly decreased plasma triacylglycerol and apoB levels accompanied by improved insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance114. GlaxoSmithKline has introduced the TGH inhibitor GR148672X (Table 2)115, but the selectivity, bioavailability, and molecular interactions of this compound with TGH have not been disclosed. ATGL, which can also mediate the lipolysis of stored TGs116, was recently evaluated for its role in an animal model of cancer-associated cachexia (CAC)117, a wasting syndrome characterized by the uncontrolled loss of muscle and adipose tissue. In this model, ATGL–/– mice resisted the loss of white adipose tissue and muscle mass observed in wild-type mice, suggesting ATGL inhibition could slow or stop CAC progression. However, to our knowledge ATGL inhibitors have not yet been reported. LIPG is an extracellular TG lipase that also possesses significant phospholipase activity118. LIPG–/– mice have increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels compared to wild-type mice119, 120, whereas mice with transgenic overexpression of LIPG have significantly reduced HDL levels120. As HDL levels are inversely correlated with risk of cardiovascular disease, these genetic models strongly suggest that LIPG is a potential therapeutic target for this indication. GlaxoSmithKline has reported initial sulfonylfuran urea-based LIPG inhibitors (Table 2), but these compounds also inhibit the related enzyme lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and have not yet been evaluated in vivo121.

Another potential serine hydrolase drug target is prolyl endopeptidase (PREP), which is also referred to as prolyl oligopeptidase (POP). PREP is a post-proline cleaving enzyme that is highly expressed in the brain, kidney, and muscle, and testes122, and can degrade a variety of neuroactive peptides, including arginine-vasopressin (AVP), substance P, and thyrotropin-releasing hormone, among others123. As several of these substrates are involved in learning and memory, the inhibition of PREP has been suggested as a strategy for the treatment of cognitive defects associated with Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and aging124. The majority of PREP inhibitor discovery efforts have centered around the modification of Z-prolyl-prolinal (ZPP), a peptide-based transition-state analog that competitively inhibits PREP125. Two compounds that emerged from this approach, JTP-4819126 and the S 17092127 (Table 2), inhibit PREP selectively over related peptidases and elevate the levels of several PREP peptide substrates in the brains of compound treated-animals126, 128–130. Encouragingly, the inhibition of PREP has been shown to produce gains in cognitive function in aging rats131 and in a chemically-induced model of early Parkinsonism in monkeys132. In humans, S 17092 showed preliminary evidence of eliciting improvements in a delayed memory task and in mood stabilization133, 134. Current work focused on the continued development of inhibitors with improved bioavailability and potency, combined with detailed mechanistic studies to molecularly understand the cognition enhancing effects of these compounds, should clarify the therapeutic potential of this target135.

Multiple serine hydrolases, such as fatty acid synthase (FASN)5, protein methylesterase-1 (PME-1)136, and the urokinase-type (uPA) and tissue-type (tPA) plasminogen activators137, have also been implicated in cancer138. Especially intriguing among potential cancer targets is fibroblast activation protein (FAP), the serine peptidase most homologous to DPP-4 (Fig. 2), which is highly expressed by stromal fibroblasts in most epithelial cancers139–141. Transfection of FAP in cancer cells promotes tumor growth in animals142. The nonselective dipeptide boronic acid FAP inhibitor PT-100 (Table 2) (Talabostat; Point Therapeutics) slowed tumor growth in mice, but PT-100’s lack of specificity precludes assignment of the precise role of FAP inhibition in this model143, 144. A recent study demonstrated that removing the FAP+ subpopulation of tumor stromal cells arrests the growth of solid tumors by inducing an immune response145. The pursuit of selective FAP inhibitors should further elucidate the role that this enzyme plays in tumorigenesis146, 147.

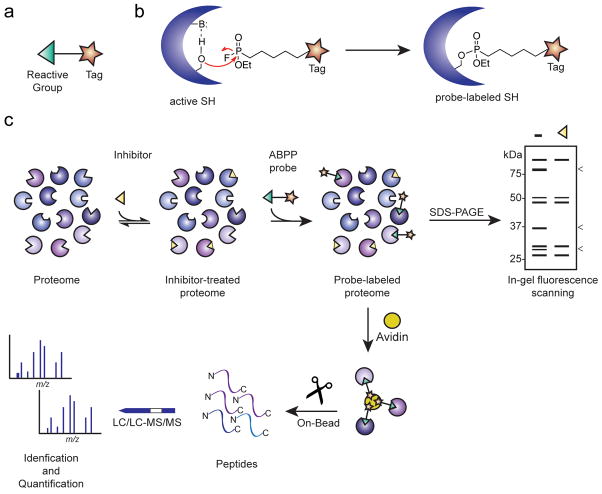

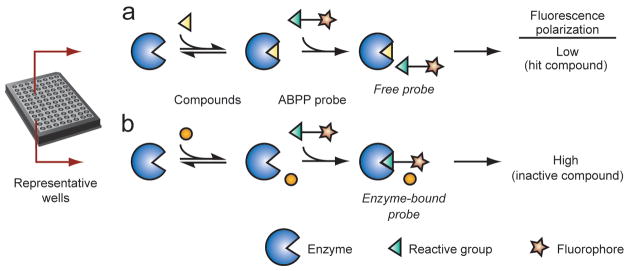

Activity-based protein profiling for target discovery

As noted above, many serine hydrolases are regulated by post-translational mechanisms, which means that changes in their activity may not correlate well with their expression levels as measured by conventional proteomic148–151 or genomic152, 153 methods. This problem has been addressed by the development of a chemoproteomic technology termed activity-based protein profiling (ABPP)154, 155, which utilizes small-molecule probes to record changes in enzyme activity directly in native biological systems. An activity-based chemical probe typically contains at least two key features: 1) a reactive group that binds and covalently modifies the active sites of a large number of enzymes that share conserved mechanistic and/or structural features, and 2) a reporter tag (e.g., a fluorophore or biotin) to enable detection, enrichment, and identification of probe-labeled enzymes (Fig. 3a). Activity-based probes have been developed for numerous enzyme classes, including serine hydrolases156, cysteine-dependent enzymes157–159, kinases160, and histone deacetylases (HDACs)161, 162. Importantly, ABPP can be applied to any biological sample (cell line, tissue, or fluid) and coupled with either gel- or mass spectrometry (MS)-based readouts to characterize numerous enzyme activities in parallel155. The most commonly employed activity-based probes for serine hydrolases contain a fluorophosphonate (FP) reactive group that covalently reacts with the conserved serine nucleophile of these enzymes (Fig. 3b). A recent global analysis of tissue and cell line proteomes demonstrated that > 80% of mammalian metabolic serine hydrolases react with FP probes11. Although it is considerably more challenging to perform an equivalent survey of the serine proteases, which typically exist endogenously in their inactive zymogen or inhibitor-bound forms, many of these proteases have also been demonstrated react with FP-probes163–166.

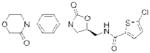

Figure 3. Overview of the current pharmacological toolkit for serine hydrolases.

The electrophilic moieties of each compound, if applicable, are colored red.

ABPP has been applied to discover serine hydrolases that are involved a wide range of biological processes, including cancer138, nervous system signaling167, immune cell function168, obesity169, 170, and infectious disease171. For example, ABPP studies first identified AADACL1 as highly elevated in aggressive cancer cells172, where it functions as a 2-acetyl monoalkylglycerol ether (MAGE) hydrolase that controls the levels of the MAGE class of neutral ether lipids (NELs)173. Stable knockdown or chemical inhibition (with the carbamate inhibitors AS115 or JW480, Table 3) of AADACL1 in cancer cells reduces the levels of MAGEs and downstream bioactive lysophospholipids, ultimately impairing cancer cell migration and invasion and in vivo tumor growth173, 174. In addition, monoacylglycerol lipase (MGLL), which can cleave a variety of monoglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol, was similarly discovered to be highly elevated in aggressive cancer cells and primary tumors7, where it controls a free fatty acid (FFA) network that includes many oncogenic signaling lipids. Overexpression of MGLL in nonaggressive cancer cells promotes their pathogenicity, whereas knockdown or inhibition of MGLL with the selective inhibitor JZL18478 (Table 3) impairs of tumor growth7, 175. In addition to its potential role in cancer, MGLL is responsible for the hydrolysis and inactivation of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2AG), an endogenous ligand for the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2. Acute MGLL inhibition with JZL184 results in CB1-dependent hypomotility and antinociception176, 177, suggesting MGLL inhibition could also be a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of pain. It should be noted that ABPP not only played an important role in discovery of AADACL1 and MGLL as therapeutic targets, but also that a competitive version of ABPP, described below, was instrumental in the development of AADACL1 and MGLL inhibitors. Moreover, ABPP analysis has recently shown that the retinoblastoma-binding protein 9 (RBBP9), which was initially discovered as a protein that could override TGF-β-mediated antiproliferative signaling178, exhibits elevated activity in tumors and promotes anchorage-independent growth and pancreatic carcinogenesis179. Preliminary lead inhibitors for RBBP9 have been recently discovered using the high-throughput competitive ABPP strategies described below180, 181. Further research into other enzymes identified in ABPP studies, many of which remain poorly characterized, should yield insights into their basic biological functions and reveal whether they possess clinical relevance.

Table 3.

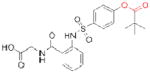

Selective inhibitors recently discovered by competitive ABPP

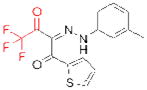

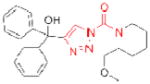

| Target | Compound | Structure | Ref. | Potential Indication(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AADACL1 | AS115 |

|

173 | cancer |

| JW480 |

|

174 | ||

| ABHD6 | WWL123 |

|

11 | unknown |

| ABHD11 | AA44-2 |

|

14 | unknown |

| WWL222 |

|

11 | ||

| APEH | AA74-1 |

|

14 | unknown |

| MGLL | JZL184 |

|

78 | cancer, pain |

| PAFAH2 | AA39-2 |

|

14 | unknown |

| PME-1 | ABL127 |

|

189 | cancer, Alzheimer’s disease |

The electrophilic moieties of each compound are colored red.

Promising new strategies for inhibitor discovery

Main challenges

Selective chemical inhibitors are notably lacking for the vast majority of human serine hydrolases, hindering investigations of their physiological roles and relationships to human disease. The dearth of inhibitors is likely due to at least three reasons: 1) many enzymes, in particular for those that are poorly characterized, lack suitable activity assays to enable compound screening, 2) achieving inhibitor selectivity for one enzyme is difficult amongst such a large, related protein family, and 3) compound libraries often do not contain tractable starting points for inhibitor optimization. Below, we discuss recently introduced approaches to address these challenges.

Gel-based competitive ABPP

When applied in a competitive format that assays the ability of compounds to block probe labeling of enzymes, ABPP enables inhibitor discovery for enzymes independent of their degree of functional annotation15, 182, 183. Competitive ABPP traditionally involves incubation of a native proteome with a small-molecule, followed by labeling with a fluorescent activity-based probe, separation of proteins by SDS-PAGE, and quantification of the fluorescence intensity of probe-labeled enzymes relative to a control proteome (Fig. 3c; “gel-based competitive ABPP”).12, 15 A complementary MS-based platform termed competitive ABPP-MudPIT has been introduced to further enhance the total protein coverage of these experiments12, 78 (Fig. 3c). ABPP-MudPIT experiments require larger quantities of sample and more time than gel-based ABPP and are therefore typically reserved for more in-depth analysis of interesting lead inhibitors. In either gel or MS formats, a key advantage of competitive ABPP is that it permits simultaneous optimization of both the potency and selectivity of inhibitors against numerous related enzymes without requiring protein purification.

Gel-based competitive ABPP screening has enabled the discovery of selective inhibitors for many serine hydrolases (Table 3), including MGLL78, ABHD611, 12, and FAAH15, 184 (Table 2, OL-135). Key to the success of these efforts was the iterative optimization of compounds containing mechanism-based electrophiles, including carbamates, ureas, and activated ketones. Recently, to expand the number of enzyme-inhibitor interactions evaluated by competitive ABPP, a library of ~150 carbamates was screened against a representative 72-member panel of metabolic serine hydrolases11. Lead compounds were identified for numerous serine hydrolases, including currently pursued drug targets (e.g., PLA2G7, FAAH) and uncharacterized enzymes (e.g., ABHD11). Two compounds were subsequently optimized to create the first potent, selective, and in vivo-active inhibitors for the poorly characterized enzymes ABHD1111 and AADACL111, 174. Interestingly, this global analysis also identified several unanticipated pharmacological crosspoints within the serine hydrolase class, where two enzymes distantly related by sequence were found to share inhibitor sensitivity profiles. Such findings underscore the value of chemoproteomic methods like competitive ABPP that can assess compound selectivity broadly across an entire enzyme class. Some clades of enzymes (e.g., the dipeptidyl peptidases), however, were not inhibited by any of the tested carbamates, indicating that additional chemotypes may be necessary to successfully target most/all subsets of serine hydrolases. Consistent with this premise, competitive ABPP analysis of a library of triazole ureas recently identified selective inhibitors for enzymes that were insensitive to carbamates, including platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase-2 (PAFAH2) and acyl-peptide hydrolase (APEH) (Table 3)14.

Competitive ABPP was also employed to assess the selectivity of the urea FAAH inhibitor PF-04457845 before this compound entered clinical trials13. PF-04457845, as well as other urea inhibitors of FAAH185, irreversibly inactivate this enzyme by carbamylating its serine nucleophile. Even though there are many irreversibly acting drugs on the market today, the pharmaceutical industry tends to prefer non-covalent, reversible inhibitors in large part due to concerns that irreversible inhibitors will lack specificity for a single protein target28. This concern, however, can be directly addressed by competitive ABPP and related chemoproteomic methods186, and when these approaches were applied to urea inhibitors of FAAH, such as PF-04457845, the compounds were found to be extremely selective for FAAH relative to serine hydrolases (and the rest of the proteome)13, 185. Once such a high degree of selectivity has been established for irreversible inhibitors, their distinctive advantages over reversibly acting compounds can be highlighted, namely that they can often inactivate their protein targets at very low doses (and with suboptimal pharmacokinetic properties) in vivo28, 186, 187. Moreover, the enzyme itself serves as a biomarker for compound activity in that in vivo inhibition can be experimentally verified by ABPP of cell, tissue, or fluid proteomes from compound-treated animals78.

High-throughput screening by competitive ABPP

Competitive ABPP has traditionally been limited by throughput, as only a few hundred compounds can be reasonably screened by gel-based methods. To overcome this barrier, a high-throughput version of competitive ABPP has recently been introduced where the interaction between an activity-based probe and an enzyme is monitored by fluorescence polarization (fluopol-ABPP)180 (Fig. 4). Fluopol-ABPP has been successfully applied to numerous enzymes from multiple mechanistic classes181, 188, 189, including several serine hydrolases. In one example, protein methylesterase-1 (PME-1), a serine hydrolase that removes an unusual post-translational carboxymethylation from the C-terminus of PP2A190 and has been implicated in Alzheimer’s disease191 and cancer136, was screened against the NIH-300,000+ small-molecule library189, 192. This effort uncovered an aza-β-lactam inhibitor (ABL127; Table 3) that selectively and covalently inhibits PME-1 with nanomolar potency. ABL127, without any medicinal chemistry optimization, showed excellent activity in living cells and mice, where it selectively inhibited PME-1 relative other serine hydrolases and decreased the levels of demethylated PP2A. Interestingly, ABL127 originated from an academic contribution to the NIH library from a synthetic chemistry laboratory exploring the substrate scope of a chiral catalyst193. That ABL127 was contributed to the NIH library without any specific protein target in mind underscores the potential of academic chemistry, when paired with high-throughput screening, to serve as a driving force for the discovery of new bioactive chemotypes and chemical probes.

Figure 4. Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) for enzyme and inhibitor discovery.

(a) Schematic representation of an activity-based probe. (b) A fluorophosphonate (FP) reactive group can be coupled to a tag (e.g., rhodamine, biotin, or alkyne) to covalently label and then detect, enrich, and identify active serine hydrolases. (c) In a typical competitive ABPP experiment, a cell or animal model is treated with an inhibitor (or vehicle control), after which proteomes are prepared and incubated with an activity-based probe. SDS-PAGE separation for fluorophore-tagged probes or mass spectrometry analysis of affinity-enriched biotin-tagged probes enables detection and identification, respectively, of the active enzymes in a biological sample. Note that an enzyme that is the target of an inhibitor will show reduced signals in the inhibitor-treated samples relative to vehicle controls (“<”).

Substrate activity screening

Even though competitive ABPP platforms address several critical challenges in serine hydrolase inhibitor discovery, many enzymes still do not have lead inhibitors, perhaps due to the absence of suitable lead compounds in chemical libraries. This deficiency should be met, at least in part, by the introduction and exploration of new hydrolase-directed chemotypes, as described above. In a complementary strategy, Ellman and coworkers introduced a technique called ‘substrate activity screening’ (SAS). This method involves the screening of a diverse library of N-acyl aminocoumarins, which fluoresce when cleaved, to identify initial, weak-binding enzyme substrates194. After a substrate is optimized for improved binding, the cleaved bond can then be replaced with a mechanism-based pharmacophore to covert it directly into an inhibitor. Although SAS has been successfully applied to select cysteine194, 195 and serine (chymotrypsin)196 proteases, it requires some intrinsic activity on at least one member N-acyl aminocoumarin library, which not all serine hydrolases will likely possess. One potential future direction could involve the creation of an even more diverse N-acyl aminocoumarin compound library for initial substrate screening. Alternatively, poor enzyme substrates, including those without any intrinsic fluorescence, can also be identified by other methods, for example by appearing as weak inhibitors in competitive ABPP experiments181. These substrates could potentially be converted into effective inhibitors via the introduction of appropriate chemical warheads in a similar manner.

Serine traps as ‘tethers’ for starting point discovery

Electrophilic traps, regardless of their inherent capacity for enzyme selectivity and/or bioavailability, can also be employed as ‘tethers’ to enable the initial identification and optimization of lead compound scaffolds that would otherwise be too weak-binding to detect. For example, Merck researchers screened a library of α-keto heterocyles, a chemotype well known to inhibit serine hydrolases15, 197, to achieve a starting point for the development of PRCP inhibitors109. After some compound optimization, the α-keto heterocyle group was replaced with an isostere to improve the selectivity for PRCP over related enzymes, avoid potential bioavailability liabilities due to the ketone moiety, and facilitate derivative synthesis. Similarly, an electrophilic ketone was used in the early stages in the development of ximeligatran39. We should note that a conceptually analogous strategy, called “tethering”, which involves the engineering of a cysteine residue into a protein (or utilizing a native cysteine, if one exists) that can capture weak-binding, disulfide-containing compounds, has shown promise for the identification of starting points for ligand development for several protein classes198, 199, and could also prove useful for the discovery of serine hydrolase inhibitors.

Engineering of biologics

While the inhibition of intracellular serine hydrolases is still the exclusive domain of small-molecules, some extracellular serine hydrolases may also be targeted by large macromolecules (e.g., hirudin and TAP). Encouragingly, the engineering of such macromolecular protease inhibitors has already been successful in improving existing and uncovering novel pharmacological tools41, 200. For example, Craik and coworkers used phage display to optimize the E. coli protein ecotin, which naturally inhibits several trypsin-fold proteases, for selective inhibition of plasma kallikrein201. Similarly, Kunitz domain-containing proteins have been modified for selective blockade of plasma kallikrein200 and tissue factor-factor VIIa (TF-FVIIa)202. In addition to natural protein scaffolds with intrinsic protease inhibitor activity, antibodies have been elicited to selectively block the activity of certain serine proteases203–205. One advantage such protein scaffolds offer is the ability to inhibit regions of the protein outside of the enzyme active-site, which are traditionally challenging to bind with small-molecules205.

Conclusions

Serine hydrolases have already yielded numerous targets of marketed drugs to treat a wide array of human diseases. Given this precedent, it is tantalizing to extrapolate that many additional drug targets may be found among the numerous enzymes from this class that remain poorly characterized. Achieving this goal, however, will require much more extensive efforts to elucidate the biochemical and physiological roles, as well as disease-relevance for serine hydrolases. Here, we believe that the development of selective and in vivo-active inhibitors is critical. Indeed, many serine hydrolases play complex roles in mammalian physiology that cannot easily be modeled in cell culture experiments. Consider, for instance, the regulation of the GLP-1 incretin by DPP-4 or the termination of cholingeric and endocannabinoid signaling in the nervous system by ACHE and FAAH, respectively. These pathways, and likely many others regulated by serine hydrolases, require the integrated physiology of an intact animal for their characterization.

So far, in vivo-active inhibitors are available for only a handful of serine hydrolases. While it might be tempting to prioritize, based on current biological knowledge, enzymes from the class for future inhibitor development efforts, we would urge against this inclination. As has been nicely delineated in a recent Perspective by Edwards and colleagues, there appears to be a strong correlation between the volume of research activity (and biological understanding) on a particular protein and the availability of high-quality chemical tools to probe this protein’s function206. This type of meta-analysis suggests that the creation of inhibitors often precedes and drives our biological understanding of enzymes, rather than the other way around, and argues for the development of inhibitors for all enzymes, regardless of their current perceived biological and/or therapeutic importance.

Encouragingly, inhibitors emerging from competitive ABPP span the full range of serine hydrolases to include enzymes that are biologically characterized and those that are devoid of functional annotation. Continued efforts following the inhibitor discovery strategies described in this Review, in particular, high-throughput screening of compound libraries and diversification of mechanism-based electrophiles, show particular promise, in our mind, to deliver new chemical probes for serine hydrolases. We also believe that further expansion of the NIH small-molecule library with structurally diverse compounds, like the aza-β-lactams, should provide useful new starting points for drug development, as well as an exciting opportunity for academic synthetic chemists. While achieving the ultimate goal of developing a selective and in vivo-active inhibitor for every mammalian serine hydrolase (as well as critical serine hydrolases in important human pathogens) may seem far away, we believe that it can be accomplished. The resulting pharmacopeia would not only power biological discovery, but also serve as a starting point for next-generation therapeutics for the betterment of human health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Cravatt laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DA025285, GM090294, CA132630, DA017259, DA009789, and CA087660), the National Science Foundation (predoctoral fellowship to D.A.B.), the California Breast Cancer Research Program (predoctoral fellowship to D.A.B.), and The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology.

References

- 1.Davie EW, Ratnoff OD. Waterfall Sequence for Intrinsic Blood Clotting. Science. 1964;145:1310–2. doi: 10.1126/science.145.3638.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitcomb DC, Lowe ME. Human pancreatic digestive enzymes. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52 :1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lane RM, Potkin SG, Enz A. Targeting acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in dementia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006;9:101–24. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonventre JV, et al. Reduced fertility and postischaemic brain injury in mice deficient in cytosolic phospholipase A2. Nature. 1997;390:622–5. doi: 10.1038/37635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menendez JA, Lupu R. Fatty acid synthase and the lipogenic phenotype in cancer pathogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:763–77. doi: 10.1038/nrc2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Activity-based proteomics of enzyme superfamilies: serine hydrolases as a case study. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285:11051–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.097600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nomura DK, et al. Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates a fatty acid network that promotes cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2010;140:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steuber H, Hilgenfeld R. Recent advances in targeting viral proteases for the discovery of novel antivirals. Curr Top Med Chem. 10:323–45. doi: 10.2174/156802610790725470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White MJ, et al. The HtrA-like serine protease PepD interacts with and modulates the Mycobacterium tuberculosis 35-kDa antigen outer envelope protein. PLoS One. 6:e18175. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damblon C, et al. The catalytic mechanism of beta-lactamases: NMR titration of an active-site lysine residue of the TEM-1 enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1747–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachovchin DA, et al. Superfamily-wide portrait of serine hydrolase inhibition achieved by library-versus-library screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:20941–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011663107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W, Blankman JL, Cravatt BF. A functional proteomic strategy to discover inhibitors for uncharacterized hydrolases. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9594–5. doi: 10.1021/ja073650c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson DS, et al. Discovery of PF-04457845: A Highly Potent, Orally Bioavailable, and Selective Urea FAAH Inhibitor. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2011;2:91–96. doi: 10.1021/ml100190t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adibekian A, et al. Click-generated triazole ureas as ultrapotent in vivo-active serine hydrolase inhibitors. Nat Chem Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nchembio.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leung D, Hardouin C, Boger DL, Cravatt BF. Discovering potent and selective reversible inhibitors of enzymes in complex proteomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:687–91. doi: 10.1038/nbt826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoover HS, Blankman JL, Niessen S, Cravatt BF. Selectivity of inhibitors of endocannabinoid biosynthesis evaluated by activity-based protein profiling. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5838–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.06.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tew DG, Boyd HF, Ashman S, Theobald C, Leach CA. Mechanism of inhibition of LDL phospholipase A2 by monocyclic-beta-lactams. Burst kinetics and the effect of stereochemistry. Biochemistry. 1998;37:10087–93. doi: 10.1021/bi9801412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stedman E, Barger GJ. Physostigmine (eserine). Part III. J Chem Soc. 1925;127:247–258. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weibel EK, Hadvary P, Hochuli E, Kupfer E, Lengsfeld H. Lipstatin, an inhibitor of pancreatic lipase, produced by Streptomyces toxytricini. I. Producing organism, fermentation, isolation and biological activity. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1987;40:1081–5. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li J, Wilk E, Wilk S. Aminoacylpyrrolidine-2-nitriles: potent and stable inhibitors of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV (CD 26) Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;323:148–54. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flentke GR, et al. Inhibition of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV (DP-IV) by Xaa-boroPro dipeptides and use of these inhibitors to examine the role of DP-IV in T-cell function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1556–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perona JJ, Craik CS. Structural basis of substrate specificity in the serine proteases. Protein Sci. 1995;4:337–60. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yousef GM, Kopolovic AD, Elliott MB, Diamandis EP. Genomic overview of serine proteases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:28–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kienesberger PC, Oberer M, Lass A, Zechner R. Mammalian patatin domain containing proteins: a family with diverse lipolytic activities involved in multiple biological functions. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 (Suppl):S63–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800082-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin S, et al. Structure of malonamidase E2 reveals a novel Ser-cisSer-Lys catalytic triad in a new serine hydrolase fold that is prevalent in nature. EMBO J. 2002;21:2509–16. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bracey MH, Hanson MA, Masuda KR, Stevens RC, Cravatt BF. Structural adaptations in a membrane enzyme that terminates endocannabinoid signaling. Science. 2002;298:1793–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1076535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, Burn P. Lipid metabolic enzymes: emerging drug targets for the treatment of obesity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:695–710. doi: 10.1038/nrd1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh J, Petter RC, Baillie TA, Whitty A. The resurgence of covalent drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 10:307–17. doi: 10.1038/nrd3410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bar-On P, et al. Kinetic and structural studies on the interaction of cholinesterases with the anti-Alzheimer drug rivastigmine. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3555–64. doi: 10.1021/bi020016x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Metzler WJ, et al. Involvement of DPP-IV catalytic residues in enzyme-saxagliptin complex formation. Protein Sci. 2008;17:240–50. doi: 10.1110/ps.073253208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villhauer EB, et al. 1-[[(3-hydroxy-1-adamantyl)amino]acetyl]-2-cyano-(S)-pyrrolidine: a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor with antihyperglycemic properties. J Med Chem. 2003;46:2774–89. doi: 10.1021/jm030091l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hadvary P, Sidler W, Meister W, Vetter W, Wolfer H. The lipase inhibitor tetrahydrolipstatin binds covalently to the putative active site serine of pancreatic lipase. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2021–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawabata K, et al. ONO-5046, a novel inhibitor of human neutrophil elastase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;177:814–20. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakayama Y, et al. Clarification of mechanism of human sputum elastase inhibition by a new inhibitor, ONO-5046, using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:2349–53. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Silver LL. Multi-targeting by monotherapeutic antibacterials. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:41–55. doi: 10.1038/nrd2202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flores MV, Strawbridge J, Ciaramella G, Corbau R. HCV-NS3 inhibitors: determination of their kinetic parameters and mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794:1441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mackman N. Triggers, targets and treatments for thrombosis. Nature. 2008;451:914–8. doi: 10.1038/nature06797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macfarlane RG. An Enzyme Cascade in the Blood Clotting Mechanism, and Its Function as a Biochemical Amplifier. Nature. 1964;202:498–9. doi: 10.1038/202498a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gustafsson D, et al. A new oral anticoagulant: the 50-year challenge. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:649–59. doi: 10.1038/nrd1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Markwardt F. The development of hirudin as an antithrombotic drug. Thromb Res. 1994;74:1–23. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White HD, Chew DP. Bivalirudin: an anticoagulant for acute coronary syndromes and coronary interventions. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002;3:777–88. doi: 10.1517/14656566.3.6.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okamoto S. A synthetic thrombin inhibitor taking extremely active stereostructure. Thromb Haemost. 1979;42:A205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walenga JM. An overview of the direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2002;32 (Suppl 3):9–14. doi: 10.1159/000069103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boudes PF. The challenges of new drugs benefits and risks analysis: lessons from the ximelagatran FDA Cardiovascular Advisory Committee. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006;27 :432–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brandstetter H, et al. Refined 2.3 A X-ray crystal structure of bovine thrombin complexes formed with the benzamidine and arginine-based thrombin inhibitors NAPAP, 4-TAPAP and MQPA. A starting point for improving antithrombotics. J Mol Biol. 1992;226:1085–99. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91054-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hauel NH, et al. Structure-based design of novel potent nonpeptide thrombin inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1757–66. doi: 10.1021/jm0109513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisert WG, et al. Dabigatran: an oral novel potent reversible nonpeptide inhibitor of thrombin. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1885–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.203604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schulman S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2342–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujikawa K, Legaz ME, Kato H, Davie EW. The mechanism of activation of bovine factor IX (Christmas factor) by bovine factor XIa (activated plasma thromboplastin antecedent) Biochemistry. 1974;13:4508–16. doi: 10.1021/bi00719a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nutt E, et al. The amino acid sequence of antistasin. A potent inhibitor of factor Xa reveals a repeated internal structure. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10162–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tuszynski GP, Gasic TB, Gasic GJ. Isolation and characterization of antistasin. An inhibitor of metastasis and coagulation. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9718–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waxman L, Smith DE, Arcuri KE, Vlasuk GP. Tick anticoagulant peptide (TAP) is a novel inhibitor of blood coagulation factor Xa. Science. 1990;248:593–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2333510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bauer KA, et al. Fondaparinux, a synthetic pentasaccharide: the first in a new class of antithrombotic agents - the selective factor Xa inhibitors. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2002;20 :37–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2002.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Perzborn E, Roehrig S, Straub A, Kubitza D, Misselwitz F. The discovery and development of rivaroxaban, an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10 :61–75. doi: 10.1038/nrd3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Becker RC, Alexander J, Dyke CK, Harrington RA. Development of DX-9065a, a novel direct factor Xa antagonist, in cardiovascular disease. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92 :1182–93. doi: 10.1160/TH04-05-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sato K, et al. YM-60828, a novel factor Xa inhibitor: separation of its antithrombotic effects from its prolongation of bleeding time. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;339:141–6. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lam PY, et al. Structure-based design of novel guanidine/benzamidine mimics: potent and orally bioavailable factor Xa inhibitors as novel anticoagulants. J Med Chem. 2003;46 :4405–18. doi: 10.1021/jm020578e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pinto DJ, et al. Discovery of 1-[3-(aminomethyl)phenyl]-N-3-fluoro-2'-(methylsulfonyl)-[1,1'-biphenyl]-4 -yl]-3-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazole-5-carboxamide (DPC423), a highly potent, selective, and orally bioavailable inhibitor of blood coagulation factor Xa. J Med Chem. 2001;44:566–78. doi: 10.1021/jm000409z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roehrig S, et al. Discovery of the novel antithrombotic agent 5-chloro-N-({(5S)-2-oxo-3- [4-(3-oxomorpholin-4-yl)phenyl]-1,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}methyl)thiophene- 2-carboxamide (BAY 59-7939): an oral, direct factor Xa inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5900–8. doi: 10.1021/jm050101d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Eriksson BI, Quinlan DJ, Eikelboom JW. Novel oral factor Xa and thrombin inhibitors in the management of thromboembolism. Annu Rev Med. 62:41–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062209-095159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Giacobini E. Cholinesterases: New roles in brain function and in Alzheimer's disease. Neurochemical Research. 2003;28:515–522. doi: 10.1023/a:1022869222652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bowen DM, Smith CB, White P, Davison AN. Neurotransmitter-related enzymes and indices of hypoxia in senile dementia and other abiotrophies. Brain. 1976;99:459–96. doi: 10.1093/brain/99.3.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davies P, Maloney AJ. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1976;2:1403. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)91936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Perry EK, Gibson PH, Blessed G, Perry RH, Tomlinson BE. Neurotransmitter enzyme abnormalities in senile dementia. Choline acetyltransferase and glutamic acid decarboxylase activities in necropsy brain tissue. J Neurol Sci. 1977;34:247–65. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(77)90073-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartus RT, Dean RL, 3rd, Beer B, Lippa AS. The cholinergic hypothesis of geriatric memory dysfunction. Science. 1982;217:408–14. doi: 10.1126/science.7046051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Kaufer DJ, Lohr KN, Carey T. Drug class review on Alzheimer's drugs: final report. Drug Class Reviews. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ellis JM. Cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of dementia. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2005;105:145–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Casida JE, Quistad GB. Serine hydrolase targets of organophosphorus toxicants. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;157–158:277–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kawakami Y, et al. The rationale for E2020 as a potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. Bioorg Med Chem. 1996;4:1429–46. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nochi S, Asakawa N, Sato T. Kinetic-Study on the Inhibition of Acetylcholinesterase by 1-Benzyl-4-[(5,6-Dimethoxy-L-Indanon)-2-Yl]Methylpiperidine Hydrochloride (E2020) Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 1995;18:1145–1147. doi: 10.1248/bpb.18.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sugimoto H, Iimura Y, Yamanishi Y, Yamatsu K. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: 1-benzyl-4-[(5,6-dimethoxy-1-oxoindan-2-yl)methyl]piperidine hydrochloride and related compounds. J Med Chem. 1995;38:4821–9. doi: 10.1021/jm00024a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harvey AL. The pharmacology of galanthamine and its analogues. Pharmacol Ther. 1995;68:113–28. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(95)02002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thomsen T, Kewitz H. Selective inhibition of human acetylcholinesterase by galanthamine in vitro and in vivo. Life Sci. 1990;46:1553–8. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90429-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomsen T, Bickel U, Fischer JP, Kewitz H. Stereoselectivity of cholinesterase inhibition by galanthamine and tolerance in humans. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;39:603–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00316106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hemsworth BA, West GB. The anticholinesterase activity of physostigmine. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1968;20:406–7. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1968.tb09774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kennedy JS, et al. Preferential cerebrospinal fluid acetylcholinesterase inhibition by rivastigmine in humans. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19:513–21. doi: 10.1097/00004714-199912000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kathuria S, et al. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9:76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Long JZ, et al. Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:37–44. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bongers J, Lambros T, Ahmad M, Heimer EP. Kinetics of dipeptidyl peptidase IV proteolysis of growth hormone-releasing factor and analogs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1122:147–53. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(92)90317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosenblum JS, Kozarich JW. Prolyl peptidases: a serine protease subfamily with high potential for drug discovery. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:496–504. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(03)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Murphy KG, Dhillo WS, Bloom SR. Gut peptides in the regulation of food intake and energy homeostasis. Endocr Rev. 2006;27:719–27. doi: 10.1210/er.2006-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thorens B. Glucagon-like peptide-1 and control of insulin secretion. Diabete Metab. 1995;21:311–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Meier JJ, Nauck MA, Schmidt WE, Gallwitz B. Gastric inhibitory polypeptide: the neglected incretin revisited. Regul Pept. 2002;107:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Drucker DJ. Biological actions and therapeutic potential of the glucagon-like peptides. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:531–44. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.31068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Holst JJ, Deacon CF. Inhibition of the activity of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV as a treatment for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1663–70. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.11.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Feng J, et al. Discovery of alogliptin: a potent, selective, bioavailable, and efficacious inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2297–300. doi: 10.1021/jm070104l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lambeir AM, et al. Dipeptide-derived diphenyl phosphonate esters: mechanism-based inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1290:76–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(96)00012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hughes TE, Mone MD, Russell ME, Weldon SC, Villhauer EB. NVP-DPP728 (1-[[[2-[(5-cyanopyridin-2-yl)amino]ethyl]amino]acetyl]-2-cyano-(S)-pyrrolidine), a slow-binding inhibitor of dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11597–603. doi: 10.1021/bi990852f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oefner C, et al. High-resolution structure of human apo dipeptidyl peptidase IV/CD26 and its complex with 1-[([2-[(5-iodopyridin-2-yl)amino]-ethyl]amino)-acetyl]-2-cyano-(S)-pyrrol idine. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2003;59:1206–12. doi: 10.1107/s0907444903010059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Villhauer EB, et al. 1-[2-[(5-Cyanopyridin-2-yl)amino]ethylamino]acetyl-2-(S)-pyrrolidinecarbon itrile: a potent, selective, and orally bioavailable dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor with antihyperglycemic properties. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2362–5. doi: 10.1021/jm025522z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Magnin DR, et al. Synthesis of novel potent dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors with enhanced chemical stability: interplay between the N-terminal amino acid alkyl side chain and the cyclopropyl group of alpha-aminoacyl-l-cis-4,5-methanoprolinenitrile-based inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2004;47:2587–98. doi: 10.1021/jm049924d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Augeri DJ, et al. Discovery and preclinical profile of Saxagliptin (BMS-477118): a highly potent, long-acting, orally active dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Chem. 2005;48:5025–37. doi: 10.1021/jm050261p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim D, et al. (2R)-4-oxo-4-[3-(trifluoromethyl)-5,6-dihydro[1,2,4]triazolo[4,3-a]pyrazin -7(8H)-yl]-1-(2,4,5-trifluorophenyl)butan-2-amine: a potent, orally active dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Chem. 2005;48:141–51. doi: 10.1021/jm0493156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eckhardt M, et al. 8-(3-(R)-aminopiperidin-1-yl)-7-but-2-ynyl-3-methyl-1-(4-methyl-quinazolin -2-ylmethyl)-3,7-dihydropurine-2,6-dione (BI 1356), a highly potent, selective, long-acting, and orally bioavailable DPP-4 inhibitor for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Med Chem. 2007;50:6450–3. doi: 10.1021/jm701280z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xu J, et al. Discovery of potent and selective beta-homophenylalanine based dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:4759–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.06.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cravatt BF, et al. Molecular characterization of an enzyme that degrades neuromodulatory fatty-acid amides. Nature. 1996;384:83–7. doi: 10.1038/384083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Naidu PS, et al. Evaluation of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibition in murine models of emotionality. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:61–70. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0689-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cravatt BF, et al. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:9371–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161191698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ahn K, et al. Novel mechanistic class of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitors with remarkable selectivity. Biochemistry. 2007;46:13019–30. doi: 10.1021/bi701378g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zalewski A, Macphee C, Nelson JJ. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2: a potential therapeutic target for atherosclerosis. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2005;5:527–32. doi: 10.2174/156800605774962103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Packard CJ, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 as an independent predictor of coronary heart disease. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1148–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.MacPhee CH, et al. Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2, platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase, generates two bioactive products during the oxidation of low-density lipoprotein: use of a novel inhibitor. Biochem J. 1999;338 ( Pt 2):479–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Davis B, et al. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry identifies substrates and products of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 in oxidized human low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6428–37. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709970200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Blackie JA, et al. The identification of clinical candidate SB-480848: a potent inhibitor of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:1067–70. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Boyd HF, et al. 2-(Alkylthio)pyrimidin-4-ones as novel, reversible inhibitors of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:395–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wilensky RL, et al. Inhibition of lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 reduces complex coronary atherosclerotic plaque development. Nat Med. 2008;14:1059–66. doi: 10.1038/nm.1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mallela J, Yang J, Shariat-Madar Z. Prolylcarboxypeptidase: a cardioprotective enzyme. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:477–81. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wallingford N, et al. Prolylcarboxypeptidase regulates food intake by inactivating alpha-MSH in rodents. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2291–303. doi: 10.1172/JCI37209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Zhou C, et al. Design and synthesis of prolylcarboxypeptidase (PrCP) inhibitors to validate PrCP as a potential target for obesity. J Med Chem. 2010;53:7251–63. doi: 10.1021/jm101013m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shen HC, et al. Discovery of benzimidazole pyrrolidinyl amides as prolylcarboxypeptidase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:1299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.01.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lehner R, Verger R. Purification and characterization of a porcine liver microsomal triacylglycerol hydrolase. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1861–8. doi: 10.1021/bi962186d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lehner R, Vance DE. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding a hepatic microsomal lipase that mobilizes stored triacylglycerol. Biochem J. 1999;343(Pt 1):1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Dolinsky VW, Gilham D, Alam M, Vance DE, Lehner R. Triacylglycerol hydrolase: role in intracellular lipid metabolism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:1633–51. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3426-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wei E, et al. Loss of TGH/Ces3 in mice decreases blood lipids, improves glucose tolerance, and increases energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2010;11:183–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Gilham D, et al. Inhibitors of hepatic microsomal triacylglycerol hydrolase decrease very low density lipoprotein secretion. FASEB J. 2003;17:1685–7. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0728fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zechner R, Kienesberger PC, Haemmerle G, Zimmermann R, Lass A. Adipose triglyceride lipase and the lipolytic catabolism of cellular fat stores. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 :3–21. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800031-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Das SK, et al. Adipose triglyceride lipase contributes to cancer-associated cachexia. Science. 2011;333:233–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1198973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.McCoy MG, et al. Characterization of the lipolytic activity of endothelial lipase. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:921–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ma K, et al. Endothelial lipase is a major genetic determinant for high-density lipoprotein concentration, structure, and metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2748–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438039100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ishida T, et al. Endothelial lipase is a major determinant of HDL level. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:347–55. doi: 10.1172/JCI16306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Goodman KB, et al. Discovery of potent, selective sulfonylfuran urea endothelial lipase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kato T, Okada M, Nagatsu T. Distribution of post-proline cleaving enzyme in human brain and the peripheral tissues. Mol Cell Biochem. 1980;32:117–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00227437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wilk S. Prolyl endopeptidase. Life Sci. 1983;33:2149–57. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lopez A, Tarrago T, Giralt E. Low molecular weight inhibitors of Prolyl Oligopeptidase: a review of compounds patented from 2003 to 2010. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 21:1023–44. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2011.577416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Bakker AV, Jung S, Spencer RW, Vinick FJ, Faraci WS. Slow tight-binding inhibition of prolyl endopeptidase by benzyloxycarbonyl-prolyl-prolinal. Biochem J. 1990;271:559–62. doi: 10.1042/bj2710559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Toide K, Iwamoto Y, Fujiwara T, Abe H. JTP-4819: a novel prolyl endopeptidase inhibitor with potential as a cognitive enhancer. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;274:1370–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Barelli H, et al. S 17092–1, a highly potent, specific and cell permeant inhibitor of human proline endopeptidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;257:657–61. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]