Abstract

Context

Myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) is the single medical test with the highest radiation burden to the US population. While many patients undergoing MPI receive repeat MPI testing, or additional procedures involving ionizing radiation, no data are available characterizing their total longitudinal radiation burden and relating radiation burden with reasons for testing.

Objective

To characterize procedure counts, cumulative estimated effective doses of radiation, and clinical indications, for patients undergoing MPI.

Design, Setting, Patients

Retrospective cohort study evaluating, for 1097 consecutive patients undergoing index MPI during the first 100 days of 2006 at Columbia University Medical Center, all preceding medical imaging procedures involving ionizing radiation undergone beginning October 1988, and all subsequent procedures through June 2008, at that center.

Main Outcome Measures

Cumulative estimated effective dose of radiation, number of procedures involving radiation, and indications for testing.

Results

Patients underwent a median (interquartile range, mean) of 15 (6–32, 23.9) procedures involving radiation exposure; 4 (2–8, 6.5) were high-dose (≥3 mSv, i.e. one year's background radiation), including 1 (1–2, 1.8) MPI studies per patient. 31% of patients received cumulative estimated effective dose from all medical sources >100mSv. Multiple MPIs were performed in 39% of patients, for whom cumulative estimated effective dose was 121 (81–189, 149) mSv. Men and whites had higher cumulative estimated effective doses, and there was a trend towards men being more likely to undergo multiple MPIs than women (40.8% vs. 36.6%, Odds ratio 1.29, 95% confidence interval 0.98–1.69). Over 80% of initial and 90% of repeat MPI exams were performed in patients with known cardiac disease or symptoms consistent with it.

Conclusion

In this institution, multiple testing with MPI was very common, and in many patients associated with very high cumulative estimated doses of radiation.

Utilization of medical imaging has grown rapidly in recent years.1 Along with the benefits patients have received from medical imaging has come an increase in the burden of ionizing radiation associated with many such tests, and the attendant potential risks of cancer. The National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements has estimated that the per capita dose of medical radiation in the United States increased nearly sixfold from the early 1980s to 2006.2 This increased medical radiation burden has raised public health concerns, leading to a Food and Drug Administration initiative to reduce unnecessary radiation exposure from medical imaging3, with one of its focuses being nuclear imaging, and discussion in Congress of new legislation to regulate medical radiation.4

While much attention has been paid to radiation from computed tomography (CT),5, 6 a recent study demonstrated that the single test with the highest radiation burden, accounting for 22% of cumulative effective dose from medical sources, is myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI).7 Volume of MPI increased from under 3 million procedures in the United States in 1990 to 9.3 million in 20028, and it is now estimated to account for >10% of the entire cumulative effective dose to the American population from all sources, excluding radiotherapy.2

Estimates of the effective dose of radiation received by a patient undergoing a single standard MPI protocol have been previously reported, ranging from the equivalent of a few hundred to two thousand chest x-rays9–11, although there are numerous sources of uncertainty in such estimates.11 However, few data are available to characterize the total radiation burden received over an extended period of time by patients undergoing MPI, many of whom present with symptoms, such as chest pain or dyspnea, which would predispose them to receive multiple tests involving ionizing radiation. We analyzed procedures involving ionizing radiation received by a cohort of patients presenting for MPI, to evaluate the total numbers of MPI exams, other tests involving radiation, cumulative effective doses of radiation, and clinical indications for and appropriateness of testing and repeat testing.

METHODS

Study Design

This retrospective cohort study evaluates procedure counts, cumulative estimated effective doses of radiation, clinical indications, and appropriateness, in a cohort of patients undergoing MPI within a single institutional system, Columbia University Medical Center/New York-Presbyterian Hospital (CUMC/NYPH), whose institutional review board approved the study.

Patient Population

All inpatients and outpatients undergoing SPECT MPI at CUMC/NYPH during the first 100 days of 2006 (January 1 through April 10, 2006) were included in the analysis. This MPI is identified here as the index procedure for each patient; no patient had >1 index procedure.

Identification of tests performed

Two electronic health record systems were manually queried by a single reader (A.B.) to identify all imaging and intervention procedures involving radiation at CUMC/NYPH and affiliated facilities that preceded the index exam, dating back to October 1988, and all subsequent tests though June 2008. This enabled identification of examinations performed over a nearly two decade period prior to the index exam, as well as providing over two years for downstream testing resulting from the findings of the index MPI. Radiotherapy procedures were excluded. Procedures were classified using 328 procedure codes. Data was entered into a spreadsheet (Excel, Microsoft, Redmond, WA), and checked for accuracy and edited by a second reader (A.J.E.).

Demographic data

Patient demographic data, including age at index procedure, sex, marital status, race/ethnicity, insurance coverage, and zip code, were obtained from the CUMC/NYPH Clinical Data Warehouse. Socioeconomic status was estimated by median annual household income in the patient's zip code, from 1999 United States Census Bureau data.12

Radiation dose estimates

Effective dose was estimated for each procedure. For MPI and nuclear medicine tests, the radiopharmaceutical(s) used and corresponding administered activities (millicuries) were generally recorded; effective dose was estimated by multiplying administered activity by a radiopharmaceutical-specific conversion factor, as specified in International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) Publications 8013 and 10614, Radiation Dose Assessment Resource tables15, and manufacturers' package inserts. In a few cases where activity was not recorded, a standard protocol was assumed. For cardiac fluoroscopic procedures such as invasive angiography and interventions, when available, recorded kerma-area product was multiplied by a standard conversion factor (0.2 mSv·mGy−1·cm−2).16 For most other procedures, effective dose was estimated using a standard value for the procedure code. The values were determined for each code, prior to the analysis, by consensus of two investigators (A.J.E., S.Ba.) based on review of the literature relating to the procedure's dosimetry and of standard imaging and intervention protocols at CUMC/NYPH. These values were in general agreement with estimates found in recent reviews,9, 17 although they are approximations which do not reflect secular trends in the dosimetry of individual procedures, e.g. improvement in mammography equipment. Cumulative estimated effective dose was determined for each patient as the sum of the estimated effective doses for each procedure undergone by that patient.

Reasons for and Appropriateness of MPI Exams

A clinical cardiologist (S.D.W.) reviewed the electronic medical record of each patient, containing the MPI report (including an indication(s) and history listed by the reporting physician) as well as in general clinical, imaging, and procedural notes and diagnostic codes. A single best reason for each test having been performed was identified, an MPI appropriate use classification was assigned based on current multisocietal guidelines,18 and MPI results were recorded. To assess reproducibility of appropriate use classification, a second cardiologist (A.J.E.), blinded to the first reader's classification, assigned an appropriate use classification using the same methodology in 200 randomly-selected cases. Due to the reviewers' need to access the entire patient electronic medical record so as to best assess testing indications and appropriateness, this review was performed without blinding as to the number or type of procedures involving ionizing radiation.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between groups were compared using Mann-Whitney, Kruskal-Wallis, or chi-square tests, as appropriate. Correlation was measured using Spearman's rho. Two-tailed p values <0.05 were considered significant. Agreement between readers was assessed using percent agreement and weighted kappa (κ). A logistic regression model was developed for prediction of repeat MPI testing. Initially, all demographic variables with p<0.2 on univariate analysis were included as independent variables in a preliminary model.19 Variables for which at least one level had p>0.25 in the preliminary multivariate model were considered for removal, and likelihood ratio tests were performed to assess whether the variable(s) significantly added to model fit, thereby warranting retention. Odds ratios (ORs) were estimated using the final logistic regression model, and are reported as adjusted OR [95% confidence interval]. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 10.1 and 11.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The cohort included 1,097 patients, including 565 women (51.5%). Mean age was 62.2±13.1 (range 11.6–96.8). 424 patients (38.7%) were Hispanic, 314 (28.6%) white, 228 black (20.8%), and 131 (11.9%) other race. Mean income for zip code was $39.3±23.0 (range 14.4–147) thousand. All but 78 patients (7.4%) had ≥1 health insurance plan.

Procedure Counts

Patients underwent a median (interquartile range [IQR], mean) of 15 (6–32, 23.9) procedures involving radiation exposure, of which 4 (2–8, 6.5) were high-dose procedures, defined here as effective dose ≥3 mSv, the equivalent of one year's natural background radiation2 (Table 1). These included 1 (1–2, 1.8) MPI studies per patient, of which 66% were dual-isotope, 28% thallium, 4% single-injection technetium-99m, 1% dual-injection technetium, and <1% positron emission tomography (PET) perfusion studies. 18.2% of patients had ≥3 MPI and 4.9% had ≥5 MPI exams. Administered activity was available for 99% of MPI exams. Previous procedures were identified for 996 (90.8%) patients, dating back a median of 7.9 (2.0–13.4, 7.8) years prior to the index procedure.

Table 1.

Numbers of Procedures involving Ionizing Radiation by Procedure Type, and Their Effective Doses

| Procedure | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | High dose | MPI | X-ray | Mammogram | CT | Fluoroa | Cardiac Cathb | PCI | Other Nuclear | |

| Procedure Numbers | ||||||||||

| Median | 15 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interquartile Range | 6–32 | 2–8 | 1–2 | 2–18 | 0–3 | 0–5 | 0–2 | 0–1 | 0-0 | 0–1 |

| 5th–95th % | 2–81 | 1–22 | 1–4 | 0–53 | 0–12 | 0–18 | 0–7 | 0–3 | 0–2 | 0–3 |

| Range | 1–193 | 1–48 | 1–17 | 0–162 | 0–20 | 0–42 | 0–36 | 0–36 | 0–6 | 0–13 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.9 (27) | 6.5 (7.6) | 1.8 (1.4) | 13.9 (18) | 2.1 (4) | 4.0 (6.3) | 1.6 (3.3) | 0.7 (2.4) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.6 (1.4) |

|

| ||||||||||

| Effective Dose (mSv) | ||||||||||

| Median | 64 | 59.7 | 28.9 | 0.7 | 0 | 8.0 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Interquartile Range | 34.5–123.3 | 30.3–116.5 | 27.9–55.6 | 0.1–2.8 | 0–0.8 | 0–32.0 | 0–20.0 | 0–7.0 | 0-0 | 0–1.8 |

| 5th–95th% | 22.6–297.5 | 20.0–278.6 | 18.2–109.6 | 0–9.3 | 0–4.3 | 0–123.0 | 0–85.2 | 0–47.0 | 0–40.0 | 0–16.3 |

| Range | 6.5–917.9 | 6.5–907.7 | 6.5–406.9 | 0–34 | 0–7.2 | 0–430.0 | 0–797.0 | 0–145.8 | 0–137.6 | 0–101.4 |

| Mean (SD) | 96.5 (93.1) | 91.1 (89.7) | 44.6 (34.4) | 2.4 (4.2) | 0.8 (1.5) | 27.4 (48.6) | 18.4 (45.0) | 8.3 (18.8) | 5.5 (15.9) | 3.0 (8.5) |

| % of Mean Dose for All Procedures | 100 | 94.3 | 46.2 | 2.4 | 0.8 | 28.4 | 19.1 | 8.6 | 5.7 | 3.1 |

Abbreviations: MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Fluoro denotes all fluoroscopic procedures, including cardiac catheterization, electrophysiology studies, and peripheral vascular studies.

Cardiac cath includes PCIs.

Cumulative Estimated Effective Doses

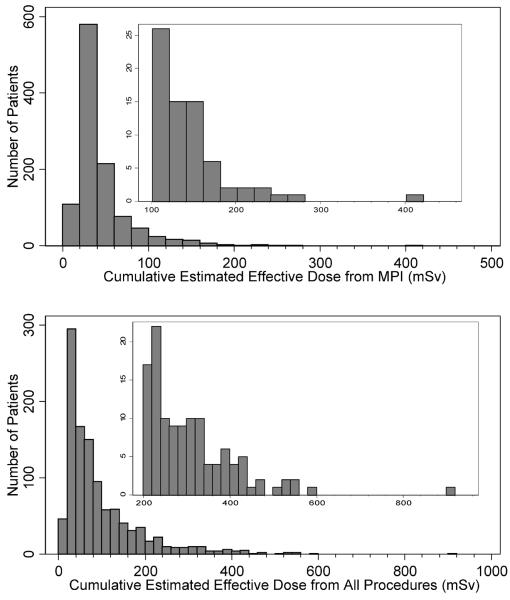

Median cumulative estimated effective dose from MPI alone was 28.9 mSv (IQR 27.9–55.6, range 6.5–407, mean 44.6 mSv). For all medical testing, median cumulative estimated effective dose was 64.0 mSv (IQR 34.5–123, range 6.5–918, mean 96.5 mSv). 71 (6.5%) patients received cumulative doses >100 mSv due to MPI alone. 344 (31.4%) patients received cumulative estimated effective dose for all medical sources of >100 mSv, including 120 (10.9%) patients who received cumulative dose >200 mSv. The distributions of cumulative estimated effective doses for MPI and for all procedures are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Cumulative estimated effective doses. Inset: Expanded y-axis. All bins are of width 20 mSv.

Differences Between Groups

Women underwent significantly more procedures involving exposure to ionizing radiation than did men, even excluding mammograms (Table 2). Nevertheless, cumulative effective dose was higher to men, reflecting primarily greater utilization of fluoroscopic procedures, including cardiac catheterization.

Table 2.

Gender and Racial Differences in Procedure Counts and Cumulative Radiation Doses. Entries represent Median (Interquartile range, Range).

| Procedure Counts | Effective Dose (mSv) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Women | Men | pa | Women | Men | pa | |

|

|

|

|||||

| All procedures | 18 (7–37, 1–193) | 12 (4–26, 1–158) | <0.001 | 61 (34–118, 8.5–546) | 69 (35–128, 6.5–918) | 0.10 |

| All except mammography | 14 (5–30, 1–193) | 12 (4–26, 1–158) | 0.04 | 60 (32–116, 8.3–540) | 69 (35–128, 6.5–918) | 0.03 |

| High dose (<3 mSv) | 4 (1–8, 1–46) | 4 (2–8, 1–48) | 0.35 | 55 (29–108, 8.3–502) | 65 (34–123, 6.5–908) | 0.01 |

| MPI | 1 (1–2, 1–11) | 1 (1–2, 1–17) | 0.11 | 29 (28–54, 6.9–254) | 29 (28–56, 6.5–407) | 0.01 |

| Other nuclear medicine | 0 (0–1, 0–11) | 0 (0–1, 0–13) | 0.58 | 0 (0–1.8, 0–74) | 0 (0–1.7, 0–101) | 0.81 |

| X-ray | 8 (3–19, 0–162) | 6 (2–16, 0–113) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.2–3.6, 0–46) | 0.5 (0.1–2.1, 0–34) | <0.001 |

| Mammography | 2 (0–7, 0–20) | 0 (0-0, 0–2) | <0.001 | 0.8 (0–2.5, 0–7.2) | 0 (0-0, 0–0.5) | <0.001 |

| CT | 2 (0–5, 0–40) | 1 (0–4, 0–42) | 0.02 | 14 (0–37, 0–430) | 7 (0–29, 0–398) | 0.04 |

| Fluoroscopy | 0 (0–2, 0–22) | 1 (0–2, 0–36) | <0.001 | 0 (0–12, 0–211) | 4.7 (0–24, 0–797) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac catheterization | 0 (0-0, 0–7) | 0 (0–1, 0–36) | <0.001 | 0 (0-0, 0–143) | 0 (0–13, 0–146) | <0.001 |

| PCI | 0 (0-0, 0–4) | 0 (0-0, 0–6) | 0.01 | 0 (0-0, 0–138) | 0 (0-0, 0–132) | 0.01 |

| Black | Hispanic | White | pb | Black | Hispanic | White | pb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||

| All procedures | 15 (7–34.5, 1–175) | 18 (8–35, 1–175) | 16 (6–33, 1–193) | 0.30 | 64 (33–113, 8.7–508) | 65 (35–123, 8.0–546) | 82 (48–159,6.5–918) | <0.001 |

| All except mammography | 12.5 (6–31, 1–166) | 16 (6–30, 1–159) | 15 (6–29, 1–193) | 0.74 | 63 (32–112, 8.3–508) | 65 (35–121, 8.0–540) | 82 (47–157, 6.5–918) | <0.001 |

| High dose (>3 mSv) | 4 (2–7, 1–43) | 4 (2–8, 1–48) | 5 (3–11, 1–46) | <0.001 | 58 (29–100, 8.3–504) | 59 (32–115, 7.9–521) | 78 (43–150, 6.5–908) | <0.001 |

| MPI | 1 (1–2, 1–10) | 1 (1–2, 1–7) | 1 (1–2, 1–17) | 0.03 | 29 (28–54, 7.6–264) | 29 (28–56, 7.9–181) | 29 (28–57, 6.5–407) | 0.003 |

| Other nuclear medicine | 0 (0–1, 0–9) | 0 (0–1, 0–8) | 0 (0–1, 0–13) | 0.16 | 0 (0–0.1, 0–84) | 0 (0–2.2, 0–51) | 0 (0–5.2, 0–101) | 0.10 |

| X-ray | 8 (3–21, 0–126) | 10 (4–19, 0–105) | 7 (2–18, 0–162) | 0.13 | 0.9 (0.2–3.3, 0–24) | 1.3 (0.3–3.2, 0–46) | 0.7 (0.2–2.6, 0–34) | 0.02 |

| Mammography | 0 (0–3, 0–19) | 0 (0–4, 0–20) | 0 (0-0, 0–19) | <0.001 | 0 (0–1.2, 0–6.4) | 0 (0–1.6, 0–7.2) | 0 (0-0, 0–7) | <0.001 |

| CT | 2 (0–5, 0–24) | 2 (0–5, 0–41) | 2 (0–6, 0–42) | 0.46 | 8 (0–36, 0–235) | 12 (0–35, 0–398) | 14 (0–36, 0–430) | 0.75 |

| Fluoroscopy | 0 (0–2, 0–16) | 1 (0–2, 0–18) | 1 (0–2, 0–36) | <0.001 | 0 (0–20, 0–284) | 1.5 (0–17, 0–406) | 7.0 (0–27, 0–797) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac catheterization | 0 (0–1, 0–7) | 0 (0–1, 0–18) | 0 (0–1, 0–36) | 0.006 | 0 (0–7, 0–113) | 0 (0–7, 0–143) | 0 (0–11, 0–122) | 0.01 |

| PCI | 0 (0-0, 0–4) | 0 (0-0, 0–4) | 0 (0-0, 0–5) | 0.50 | 0 (0-0, 0–106) | 0 (0-0, 0–138) | 0 (0-0, 0–103) | 0.55 |

Abbreviations: MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; CT, computed tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention

P values for gender are for comparison of medians between women and men, using Mann-Whitney test.

P values for race are for comparison of medians between all three groups, using Kruskal-Wallis test with chi-squared adjusted for ties.

No significant differences in total number of procedures involving radiation were observed between black, Hispanic, and white patients (Table 2). However, whites underwent more MPI and fluoroscopy/catheterization procedures, and correspondingly, higher cumulative effective dose. There was no strong correlation between socioeconomic status (median income for zip code) and number of MPI exams, number of ionizing radiation procedures, or cumulative effective dose (absolute value of rho <0.1 for each). Nevertheless, patients without health insurance underwent fewer tests involving radiation (median [IQR] of 5.5 [3–19] vs. 16 [7–34], p<0.001; mean 13.1 vs. 25.7) and correspondingly lower cumulative effective dose (median [IQR] of 37.4 [28.8–76.8] vs. 68.5 [36.7–131.8] mSv, p<0.001; mean of 66.3 vs. 101.2 mSv) than patients with any health insurance.

Reasons and Appropriateness

Reasons for testing and appropriateness classifications are summarized in Table 3. Inappropriate exams were less likely to demonstrate ischemia or scar than appropriate or uncertain exams (12.6% vs. 45.5%, p<0.001). However, undergoing an inappropriate exam was not significantly associated with cumulative dose >100 mSv or multiple testing. There was moderate agreement between readers in AUC classification (74% agreement, 90% within one classification, κ=0.41, 95% confidence interval 0.24–0.57).

Table 3.

Characteristics, Appropriateness, and Reasons for Myocardial Perfusion Imaging

| All | No Repeat MPI | Repeat MPI | Repeat MPI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| Interval between Repeat MPI Studies |

||||||||||

| ≤1 month | 1–3 months | 3–6 months | 6–12 months | 1–2 years | 2–5 years | >5 years | ||||

| Patients and Exams | ||||||||||

| Patients with repeat study in designated interval or shorter interval | ||||||||||

| Number of patients | 1097 | 673 | 424 | 7 | 23 | 55 | 117 | 236 | 359 | 424 |

| Median (IQR) number of MPI studies | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1) | 2 (2–3)a | 3 (2–5)a | 5 (3–6)a | 4 (3–6)a | 4 (3–6)a | 3 (2–4)a | 3 (2–4)a | 2 (2–3)a |

| Median (IQR) number of studies involving ionizing radiation | 15 (6–32) | 10 (4–20) | 27 (13.5–48)a | 35 (16–46)b | 45 (20–75)a | 36 (15–46)a | 26 (12–50)a | 26 (12.5–49.5)a | 27 (13–48)a | 27 (13.5–48)a |

| Median (IQR) cumulative effective dose (mSv) | 64 (34–123) | 40 (29–66) | 121 (81–189)a | 110 (73–186)c | 188 (110–329)a | 187 (116–262)a | 167 (105–243)a | 142 (90–215)a | 127 (82–198)a | 121 (81–189)a |

| Patients with repeat study in designated interval | 1097 | 673 | 424 | 7 | 18 | 37 | 86 | 171 | 223 | 121 |

| Patients with minimal interval as designated interval | 1097 | 673 | 424 | 7 | 16 | 32 | 62 | 119 | 123 | 65 |

| Total number of exams in designated interval | 1941 | 1097 | 844 | 7 | 21 | 40 | 120 | 239 | 289 | 128 |

| Appropriateness of MPI Exam | ||||||||||

| All Exams | ||||||||||

| Appropriate, No. (%) | 1480 (76.2) | 791 (72.1) | 689 (81.6) | 5 (71.4) | 18 (85.7) | 31 (77.5) | 108 (90.0) | 191 (79.9) | 227 (78.5) | 109 (85.2) |

| Uncertain, No. (%) | 116 (6) | 43 (3.9) | 73 (8.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (10.0) | 5 (4.2) | 30 (12.6) | 28 (9.7) | 4 (3.1) |

| Inappropriate, No. (%) | 293 (15.1) | 223 (20.3) | 70 (8.3) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (10.0) | 7 (5.8) | 15 (6.3) | 26 (9) | 15 (11.7) |

| Could not be classified, No. (%) | 52 (2.7) | 40 (3.6) | 12 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.3) | 8 (2.8) | 0 (0) |

| Classifiable Exams | ||||||||||

| Appropriate, No. (%) | 1480 (78.3) | 791 (74.8) | 689 (82.8) | 5 (71.4) | 18 (85.7) | 31 (79.5) | 108 (90.0) | 191 (80.9) | 227 (80.8) | 109 (85.2) |

| Uncertain, No. (%) | 116 (6.1) | 43 (4.1) | 73 (8.8) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (10.3) | 5 (4.2) | 30 (12.7) | 28 (10) | 4 (3.1) |

| Inappropriate, No. (%) | 293 (15.5) | 223 (21.1) | 70 (8.4) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (10.3) | 7 (5.8) | 15 (6.4) | 26 (9.3) | 15 (11.7) |

| Reason for MPI Exam, No. (%) | ||||||||||

| Chest pain and/or dyspnea | 1296 (67) | 776 (71) | 520 (62) | 2 (29) | 12 (57) | 21 (53) | 78 (65) | 141 (59) | 178 (62) | 91 (71) |

| New, no known CAD or prior intervention | 595 (31) | 558 (51) | 37 (4.4) | 2 (1.7) | 10 (4.2) | 12 (4.2) | 13 (10) | |||

| Recurrent, no known CAD or prior intervention | 219 (11) | 58 (5.3) | 161 (19) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (5.0) | 13 (11) | 35 (15) | 70 (24) | 40 (31) | |

| Recurrent, known obstructive CAD or prior intervention | 433 (22) | 131 (12) | 302 (36) | 2 (29) | 11 (52) | 17 (43) | 58 (48) | 91 (38) | 90 (31) | 36 (28) |

| Post-ACS risk stratification | 18 (0.9) | 15 (1.4) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.8) | |||||

| Angiogram documented CAD, evaluate ischemia | 21 (1.1) | 13 (1.2) | 8 (0.9) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) | 3 (1.0) | ||||

| Recurrent, nonobstructive CAD on angiogram between tests | 10 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 9 (1.1) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | ||

| Arrhythmia | 19 (1.0) | 13 (1.2) | 6 (0.7) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.4) | |||||

| Atrial fibrillation, new onset | 10 (0.5) | 8 (0.7) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.7) | ||||||

| Ventricular tachycardia | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) | ||||||

| Other | 7 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | |||||

| Syncope | 20 (1.0) | 15 (1.4) | 5 (0.6) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | |||

| Asymptomatic | 583 (30) | 282 (26) | 301 (36) | 2 (29) | 7 (33) | 17 (43) | 43 (36) | 94 (39) | 101 (35) | 37 (29) |

| Prior CABG (<5 years after CABG) | 55 (2.8) | 21 (1.9) | 34 (4.0) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (10) | 3 (2.5) | 12 (5.0) | 12 (4.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Prior CABG (>5 years after CABG) | 42 (2.2) | 12 (1.1) | 30 (3.6) | 1 (2.5) | 6 (5.0) | 12 (5.0) | 8 (2.8) | 3 (2.3) | ||

| Prior PCI, residual ischemia, no intervention between tests | 11 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 10 (1.2) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (2.5) | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.8) | |||

| Prior PCI, no residual ischemia, no intervention between tests | 41 (2.1) | 3 (0.3) | 38 (4.5) | 1 (4.8) | 4 (10) | 4 (3.3) | 16 (6.7) | 12 (4.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| PCI between tests, evaluate residual ischemia | 56 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 56 (6.6) | 4 (19) | 7 (17.5) | 15 (12.5) | 13 (5.4) | 13 (4.5) | 4 (3.1) | |

| New ECG findings of MI or elevated cardiac enzymes | 5 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | |||||

| New LV dysfunction, systolic | 19 (1.0) | 18 (1.6) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | ||||||

| CAD on prior angiogram or MPI, evaluate ischemia | 87 (4.5) | 23 (2.1) | 64 (7.6) | 1 (14) | 1 (2.5) | 10 (8.3) | 20 (8.4) | 26 (9.0) | 6 (4.7) | |

| No CAD history, low CAD Framingham risk | 61 (3.1) | 53 (4.8) | 8 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (3.9) | ||||

| No CAD history, low CAD Framingham risk but family history | 36 (1.9) | 26 (2.4) | 10 (1.2) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 3 (1.0) | 4 (3.1) | |||

| No CAD history, moderate CAD Framingham risk | 42 (2.2) | 29 (2.6) | 13 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.3) | 6 (2.1) | 3 (2.3) | |||

| No CAD history, high CAD Framingham risk | 21 (1.1) | 14 (1.3) | 7 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (3.1) | ||||

| Pre-operative assessment, low risk surgery | 31 (1.6) | 25 (2.3) | 6 (0.7) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.4) | ||||

| Pre-operative assessment, intermediate risk surgery | 32 (1.6) | 21 (1.9) | 11 (1.3) | 1 (14) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.7) | 4 (3.1) | |||

| Pre-operative assessment, high risk surgery | 41 (2.1) | 32 (2.9) | 9 (1.1) | 4 (1.7) | 4 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | ||||

| Prior calcium score | 3 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) | ||||||

| Technical | 9 (0.5) | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.7) | 3 (43) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) | |||

| First test submaximal or stress not completed | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.2) | 2 (29) | ||||||

| Viability and ischemia evaluations performed separately | 7 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (14) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (0.8) | |||

| Other | 14 (0.7) | 8 (0.7) | 6 (0.7) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.4) | ||||

Abbreviations: MPI, myocardial perfusion imaging; IQR, interquartile range; CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; ECG, electrocardiogram; MI, myocardial infarction; LV, left ventricular

p<0.001 by Mann-Whitney test, in comparison to patients without repeat studies in ≤ designated interval.

p=0.07 by Mann-Whitney test, in comparison to patients without repeat studies in ≤ designated interval.

p=0.04 by Mann-Whitney test, in comparison to patients without repeat studies in ≤ designated interval.

Characteristics of Patients Undergoing Multiple MPI Studies

Of 1,097 patients undergoing index MPI, 424 underwent additional MPI studies. Median time (IQR) between repeated MPI exams was 23.7 (13.0–42.3) months. 56% of patients undergoing multiple MPI exams had two exams within 2 years of each other, and 28% had two MPI exams within 1 year of each other. Repeat tests were more likely to demonstrate ischemia (36% vs. 24%, p<0.001) or scar (25% vs. 14%, p<0.001) than initial tests, and were less likely to be inappropriate (8.4% vs. 21.1%, p<0.001). Indications for repeat testing, summarized in Table 3, varied depending on interval between repeat exams. In multivariate analysis, patients undergoing multiple MPI exams were significantly or borderline significantly more likely to be older (OR 1.31 [1.17–1.46] for 10 years increase in age), male (OR 1.29 [0.98–1.69]), of higher socioeconomic status (OR 1.05 [0.99–1.12] for $10,000 increase in median household income), and insured (OR 2.11 [1.15–3.87]). Ethnicity, religion, and marital status were not significantly associated with undergoing multiple MPI exams.

COMMENT

This study reveals very high cumulative effective doses to many patients undergoing MPI, and especially to patients undergoing repeat MPI testing. Over 30% of patients received a cumulative effective dose >100 mSv, a level at which there is little controversy over the potential for increased cancer risks.20 The median cumulative estimated effective dose for the 39% of patients undergoing more than one MPI exam was 121 mSv, higher than that in the exposed (≥5 mSv) cohort in the Life Span Study of Japanese atomic bomb survivors.21

Nevertheless, while effective dose reflects cancer risk from radiation, it is a population-averaged metric that does not account for individual characteristics such as age and health status. The population of patients undergoing MPI is fundamentally very different in several respects from both the Life Span Study cohort and, more importantly, the general American population. These differences favorably shift the balance of benefit versus risk of the ionizing radiation associated with MPI. Patients undergoing MPI are older than the general population, averaging 62 years here, and based on primary indications for testing—over 80% of initial MPIs and 90% of repeat exams were performed in patients with known cardiac disease or symptoms consistent with it—would be expected to have lower life expectancy than that predicted by age, noteworthy since solid tumors typically develop only after a lag period of at least 5–10 years following radiation exposure.22 The clear majority of MPI exams were performed for reasons presently regarded as appropriate18, and with the potential to effect therapeutic management. Our appropriateness data is consistent with findings in other studies, e.g. Hendel et al23 noted only 14.4% of classifiable MPIs to be inappropriate, we found 15.5%, and Gibbons et al24 found 15.9%.

Thus, while the high cumulative doses observed are certainly a matter of concern and an important target for improvement, these doses should not be viewed in isolation but rather within the clinical context where radiation risk for a specific patient is balanced against potential benefits. In particular, MPI plays a critical role in risk stratification of patients with established coronary disease.25

Few studies have evaluated cumulative effective doses of radiation to patients undergoing multiple tests. In a series of 50 consecutive patients admitted to a cardiology service in Pisa, Italy, Bedeti et al noted median cumulative estimated effective dose from procedures performed during hospitalizations from 1970 to January 2006 of 61 mSv26, similar to the median dose in our study. Two studies have examined cumulative dose from CT alone. One observed patients receiving CT underwent a median of 3 scans over a 22 year period, with median cumulative effective dose 24 mSv.27 The second, limited to patients with ≥3 emergency department visits in a year during which they received certain types of CT scans, found median cumulative estimated effective dose of 91 mSv over an 8 year period.28 The largest study investigating cumulative estimated effective dose considered doses from 2005 through 2007 for nearly a million individuals covered by a single healthcare benefits organization. Median estimated effective dose was 0.1 mSv per enrollee per year, although 21% of individuals received cumulative estimated effective doses >9 mSv over the three years, and 2% received >60 mSv.7 Nearly 10% of these patients underwent at least one cardiac imaging procedure using radiation. Among this subset, the mean cumulative estimated effective dose from cardiac procedures was 23.1 mSv, with 74% of this accounted for by MPI.29 This lower cumulative dose noted in the healthcare benefits organization cohort than in the CUMC/NYPH cohort can be accounted for by multiple factors, including the former's limitation to cardiac procedures, the 3 vs. 20 year period over which procedures were observed, and the lower estimated mean dose for an MPI exam.

The findings of these studies, together with our findings here, suggest that while most individuals receive little radiation from medical procedures, there exist certain groups of patients who receive high cumulative doses of radiation. Patients undergoing MPI, particularly those undergoing repeated MPI, are one such group. Efforts to reduce cumulative radiation dose should be especially targeted towards such groups.

Two cornerstones of radiological protection are justification (ensuring expected benefit exceeds harm for each exposure) and optimization (keeping the likelihood of incurring exposure and magnitude of individual exposures as low as reasonably achievable).30 Even if an individual MPI study is justified based on appropriateness criteria, the cumulative radiation burden from all medical imaging and intervention procedures may not be optimized. Here, the index MPI exam accounted for only 26% of cumulative radiation dose on average. While current appropriate use criteria provide guidance for MPI utilization in terms of an individual test, we observed only moderate interobserver agreement in their application, although somewhat better agreement has been reported elsewhere.24, 31 Moreover, these criteria do not yet simultaneously consider the appropriateness of other modalities which involve no ionizing radiation exposure, and only superficially address longitudinal management strategies, which have clear implications for both radiation dose and healthcare costs.

For example, for patients with prior MPI presenting with new chest pain, current criteria view repeat MPI as “appropriate” if a prior MPI or angiogram was abnormal and “uncertain” if the prior test was normal. No distinction is made as to the number of prior tests performed, the interval between tests, the nature of any abnormal findings, and whether any were inconclusive. Several studies support existence of a “warranty period” for normal MPI, during which coronary events are unlikely to occur.32–34 Consistent with this, we observed normal myocardial perfusion for all 16 patients undergoing repeat MPI within one year for recurrent chest pain without prior evidence of ischemia or scarring. Future efforts need to focus not just on individual test justification but on optimizing and validating longitudinal imaging strategies, to lower cumulative doses while ensuring performance of imaging needed for therapeutic decision-making. Such strategies should incorporate tests without radiation, including stress echocardiography, stress magnetic resonance imaging, and exercise electrocardiography, and consider CT or invasive coronary angiography to “close the book” on cardiac sources of persistent, atypical symptoms.

Several approaches exist to decrease effective dose of an individual MPI examination. Two thirds of MPI exams in the 20-year period studied here were performed using a dual-isotope protocol, with rest imaging using thallium-201 followed by stress with technetium-99m. Dual-isotope imaging, while facilitating laboratory workflow, is associated with considerably higher radiation dose than other protocols9, and our laboratory has subsequently moved away from its routine use, thereby decreasing the average effective dose of MPI, although avoidance of thallium-201 has been challenged by worldwide shortages of technetium-99m.35 Utilization of protocols limited to technetium-99m typically reduces radiation dose by over 50% in comparison to dual-isotope imaging. This is especially the case for stress-only protocols, which often can be performed with low administered activity.36 PET MPI9 and low-dose protocols using newer camera37 and image reconstruction38 technologies offer the potential to decrease dose even further.

An interesting finding here is the existence of several differences between groups. Men, whites, and insured patients had higher odds of undergoing multiple MPI studies, and received more MPI exams, fluoroscopic procedures, and higher cumulative dose. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating lower utilization of stress imaging tests, cardiac catheterization, and coronary revascularization in women and nonwhite patients.39–41 Whether this disparity in radiation doses represents an advantage or disadvantage is dependent on whether increase in utilization results in improved cardiovascular outcomes, and requires further study.

One limitation of this study is the retrospective application of appropriate use criteria. While retrospective assessment has been used in several previous studies of appropriateness, risk stratification and appropriateness classification is best performed prospectively and with complete information.23 Another limitation is that radiation dose records are limited to tests performed within a single hospital system. This restriction could potentially underestimate the problem of multiple testing, by missing procedures and radiation doses received by patients at other facilities. While CUMC/NYPH has a large pool of referring physicians, the findings of frequent repeat testing and high cumulative doses should be confirmed in regions of the country for which practice patterns differ.42 A third limitation is the use of median income from zip code as an area-based socioeconomic measure. While zip-code level data can minimize incomplete matching during geocoding43, in some settings it may be less accurate than block group- or census tract-level data as a surrogate for patient-level socioeconomic data.44

In summary, in this single-center study, we observed multiple testing with MPI to be common, and in many patients to be associated with very high cumulative estimated doses of radiation. Efforts are needed to decrease this high cumulative dose and its attendant risks.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Sponsor: No sponsor had any role in design or conduct of the study, collection or analysis of the data, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding/Support: Dr Einstein was supported by an NIH K12 institutional career development award (KL2 RR024157), by the Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. Scholars Program, and by the Lewis Katz Cardiovascular Research Prize for a Young Investigator.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Einstein had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Einstein, Balter.

Acquisition of data: Einstein, Weiner, Bernheim, Kulon, Balter.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Einstein, Weiner, Bernheim, Kulon, Bokhari, Johnson, Moses, Balter.

Drafting of the manuscript: Einstein.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Einstein, Weiner, Bernheim, Kulon, Bokhari, Johnson, Moses, Balter.

Statistical analysis: Einstein.

Obtained funding: Einstein.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Bokhari, Johnson, Moses.

Study supervision: Einstein, Balter.

Financial Disclosures: Dr Einstein reports having served as a consultant for the International Atomic Energy Agency and for GE Healthcare, having received support for other research from Spectrum Dynamics and from a Nuclear Cardiology Foundation grant funded by Covidien, and having received travel funding from GE Healthcare, INVIA, Philips Medical Systems, and Toshiba America Medical Systems. Dr Moses reports having served as a consultant for GE Healthcare. Dr Balter reports having served as a consultant for the International Atomic Energy Agency and for Siemens. All other authors reported no disclosures.

References

- 1.Iglehart JK. The new era of medical imaging--progress and pitfalls. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(26):2822–2828. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr061219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements . Report No. 160, Ionizing Radiation Exposure of the Population of the United States. Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Accessed April 20, 2010];FDA unveils initiative to reduce unnecessary radiation exposure from medical imaging. FDA News Release of February 9, 2010. http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm200085.htm.

- 4.House of Representatives. Subcommittee on Health. Committee on Energy and Commerce [Accessed April 20, 2010];Hearing on “Medical radiation: an overview of the issues”. http://energycommerce.house.gov/Press_111/20100226/transcript.02.26.2010.he.pdf.

- 5.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography--an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(22):2277–2284. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Einstein AJ, Henzlova MJ, Rajagopalan S. Estimating risk of cancer associated with radiation exposure from 64-slice computed tomography coronary angiography. JAMA. 2007;298(3):317–323. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fazel R, Krumholz HM, Wang Y, et al. Exposure to low-dose ionizing radiation from medical imaging procedures. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(9):849–857. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.2003 Nuclear Medicine Census Market Summary Report. IMV Medical Information Division; Des Plaines, IL: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Einstein AJ, Moser KW, Thompson RC, Cerqueira MD, Henzlova MJ. Radiation dose to patients from cardiac diagnostic imaging. Circulation. 2007;116(11):1290–1305. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.688101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stabin MG. Radiopharmaceuticals for nuclear cardiology: radiation dosimetry, uncertainties, and risk. J Nucl Med. 2008;49(9):1555–1563. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.052241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber TC, Carr JJ, Arai AE, et al. Ionizing radiation in cardiac imaging: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiac Imaging of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention of the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Circulation. 2009;119(7):1056–1065. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.U. S. Census Bureau [Last Accessed: July 1, 2009];Download Center: American FactFinder. http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/DownloadDatasetServlet?_lang=en.

- 13.Radiation dose to patients from radiopharmaceuticals. Addendum 2 to ICRP publication 53. ICRP Publication 80. Ann ICRP. 1998;28(3):1–126. doi: 10.1016/s0146-6453(99)00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radiation dose to patients from radiopharmaceuticals. Addendum 3 to ICRP publication 53. ICRP Publication 106. Ann ICRP. 2008;38(1–2):1–197. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stabin M, Siegel J, Hunt J, Sparks R, Lipsztein J, Eckerman K. RADAR: the radiation dose assessment resource—an online source of dose information for nuclear medicine and occupational radiation safety [abstract] J Nucl Med. 2001;42(suppl):243P. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efstathopoulos EP, Brountzos EN, Alexopoulou E, et al. Patient radiation exposure measurements during interventional procedures: a prospective study. Health Phys. 2006;91(1):36–40. doi: 10.1097/01.HP.0000198783.10855.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mettler FA, Jr, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M. Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology. 2008;248(1):254–263. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2481071451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendel RC, Berman DS, Di Carli MF, et al. ACCF/ASNC/ACR/AHA/ASE/SCCT/SCMR/SNM 2009 appropriate use criteria for cardiac radionuclide imaging: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, the American College of Radiology, the American Heart Association, the American Society of Echocardiography, the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Nuclear Medicine. Circulation. 2009;119(22):e561–587. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(1):125–137. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charles MW. LNT--an apparent rather than a real controversy? J Radiol Prot. 2006;26(3):325–329. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/26/3/N02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Preston DL, Shimizu Y, Pierce DA, Suyama A, Mabuchi K. Studies of mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 13: Solid cancer and noncancer disease mortality: 1950–1997. Radiat Res. 2003;160(4):381–407. doi: 10.1667/rr3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Committee to Assess Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation. Nuclear Radiation Studies Board. Division on Earth Life Studies. National Research Council of the National Academies . Health Risks From Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation: BEIR VII Phase 2. The National Academies Press; Washington: 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendel RC, Cerqueira M, Douglas PS, et al. A multicenter assessment of the use of single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion imaging with appropriateness criteria. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(2):156–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gibbons RJ, Miller TD, Hodge D, et al. Application of appropriateness criteria to stress single-photon emission computed tomography sestamibi studies and stress echocardiograms in an academic medical center. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(13):1283–1289. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117(10):1283–1291. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bedetti G, Botto N, Andreassi MG, Traino C, Vano E, Picano E. Cumulative patient effective dose in cardiology. Br J Radiol. 2008;81(969):699–705. doi: 10.1259/bjr/29507259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sodickson A, Baeyens PF, Andriole KP, et al. Recurrent CT, cumulative radiation exposure, and associated radiation-induced cancer risks from CT of adults. Radiology. 2009;251(1):175–184. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511081296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffey RT, Sodickson A. Cumulative radiation exposure and cancer risk estimates in emergency department patients undergoing repeat or multiple CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192(4):887–892. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Einstein AJ, Fazel R, et al. Cumulative exposure to ionizing radiation from cardiac imaging procedures: a population-based analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. Ann ICRP. 2007;37(2–4):1–332. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibbons RJ, Askew JW, Hodge D, Miller TD. Temporal trends in compliance with appropriateness criteria for stress single-photon emission computed tomography sestamibi studies in an academic medical center. Am Heart J. 2010;159(3):484–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hachamovitch R, Hayes S, Friedman JD, et al. Determinants of risk and its temporal variation in patients with normal stress myocardial perfusion scans: what is the warranty period of a normal scan? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(8):1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schinkel AF, Elhendy A, Bax JJ, et al. Prognostic implications of a normal stress technetium-99m-tetrofosmin myocardial perfusion study in patients with a healed myocardial infarct and/or previous coronary revascularization. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metz LD, Beattie M, Hom R, Redberg RF, Grady D, Fleischmann KE. The prognostic value of normal exercise myocardial perfusion imaging and exercise echocardiography: a meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(2):227–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Einstein AJ. Breaking America's dependence on imported molybdenum. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(3):369–371. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang SM, Nabi F, Xu J, Raza U, Mahmarian JJ. Normal stress-only versus standard stress/rest myocardial perfusion imaging: similar patient mortality with reduced radiation exposure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(3):221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berman DS, Kang X, Tamarappoo B, et al. Stress thallium-201/rest technetium-99m sequential dual isotope high-speed myocardial perfusion imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(3):273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.DePuey G, Bommireddipalli S. Half-dose myocardial perfusion SPECT with wide beam reconstruction. Circulation. 2009;120:S334. doi: 10.1007/s12350-011-9340-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lucas FL, DeLorenzo MA, Siewers AE, Wennberg DE. Temporal trends in the utilization of diagnostic testing and treatments for cardiovascular disease in the United States, 1993–2001. Circulation. 2006;113(3):374–379. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.560433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lucas FL, Siewers AE, DeLorenzo MA, Wennberg DE. Differences in cardiac stress testing by sex and race among Medicare beneficiaries. Am Heart J. 2007;154(3):502–509. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson ED, Shaw LK, DeLong ER, Pryor DB, Califf RM, Mark DB. Racial variation in the use of coronary-revascularization procedures. Are the differences real? Do they matter? N Engl J Med. 1997;336(7):480–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702133360706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional variations in diagnostic practices. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):45–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0910881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiscella K, Franks P. Impact of patient socioeconomic status on physician profiles: a comparison of census-derived and individual measures. Med Care. 2001;39(1):8–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200101000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures--the public health disparities geocoding project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655–1671. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]