Abstract

Recent scientific advances have demonstrated the existence of extensive RNA-based regulatory networks involved in orchestrating nearly every cellular process in health and various disease states. This previously hidden layer of functional RNAs is derived largely from non–protein-coding DNA sequences that constitute more than 98% of the genome in humans. These non–protein-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) include subclasses that are well known, such as transfer RNAs and ribosomal RNAs, as well as those that have more recently been characterized, such as microRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, and long ncRNAs. In this review, we examine the role of these novel ncRNAs in the nervous system and highlight emerging evidence that implicates RNA-based networks in the molecular pathogenesis of stroke. We also describe RNA editing, a related epigenetic mechanism that is partly responsible for generating the exquisite degrees of environmental responsiveness and molecular diversity that characterize ncRNAs. In addition, we discuss the development of future therapeutic strategies for locus-specific and genome-wide regulation of genes and functional gene networks through the modulation of RNA transcription, posttranscriptional RNA processing (eg, RNA modifications, quality control, intracellular trafficking, and local and long-distance intercellular transport), and RNA translation. These novel approaches for neural cell- and tissue-selective reprogramming of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms are likely to promote more effective neuroprotective and neural regenerative responses for safeguarding and even restoring central nervous system function.

Mutations in mitochondrial DNA are responsible for a spectrum of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies, including mitochondrial encephalopathy with lactic acidosis and strokelike episodes.1 Although the DNA sequences that harbor these mutations generally do not code for proteins, many of them encode transfer (tRNAs) and ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs). The array of clinical symptoms seen in mitochondrial disorders highlights the functional importance of non–protein-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) such as tRNAs and rRNAs that are transcribed from non–protein-coding DNA sequences. In fact, the pathogenesis of a spectrum of neurodevelopmental, neurodegenerative, and neuropsychiatric diseases is increasingly being associated with mutations of ncRNAs (Table).2

Table.

RNA-Based Epigenetic Regulatory Mechanisms in Stroke

| Epigenetic Mechanism | Description | Relevance to Stroke |

|---|---|---|

| ncRNAs and RNA regulatory networks | Refer to RNAs transcribed from non–protein-coding DNA sequences that constitute >98% of the human genome | Mutations in mitochondrial ncRNAs are responsible for a spectrum of mitochondrial encephalopathies, including MELAS |

| Include well-known classes (eg, tRNAs and rRNAs) and recently characterized classes (eg, miRNAs, snoRNAs, and lncRNAs) | Differential expression of ncRNAs in ischemic brain tissue and can be detected in peripheral blood | |

| More efficiently couple bioenergetic requirements within the CNS with information storage and processing compared with DNA or protein | ANRIL is an lncRNA for which differential expression is associated with atherosclerosis, diabetes, and aneurysms | |

| Implicated in orchestration of neural development, homeostasis, and plasticity | An SNP associated with the GOMAFU lncRNA locus is a susceptibility factor for cardiovascular disease | |

| RNA editing and DNA recoding | Refer to mechanisms for altering nucleotides in RNA (RNA editing) and DNA molecules (DNA recoding) | Defective glutamate receptor subunit RNA editing influences vulnerability of hippocampal neurons to ischemia-associated cell death |

| Mediated by families of enzymes called ADARs (RNA editing) and APOBECs (RNA editing and DNA recoding) | Disruption of gene encoding an RNA-editing enzyme in Drosophila species results in very prolonged recovery time from anoxic stupor, vulnerability to heat shock, and increased oxygen demands | |

| Promote genomic diversity and plasticity in highly environmentally responsive manner | One of the substrates for APOBEC enzymes is the APOB mRNA, which encodes an apolipoprotein found in chylomicrons and LDLs | |

| May also allow transmission of productive alterations back into neural genome | Genetic variants of APOBEC1 and APOBEC2 are associated with high levels of serum LDL and increased atherosclerosis |

Abbreviations: ADARs, adenosine deaminases that act on RNA; APOB, apolipoprotein B; APOBECs, APOB-editing catalytic subunits; CNS, central nervous system; LDLs, low-density lipoproteins; lncRNAs, long ncRNAs; MELAS, mitochondrial encephalopathy with lactic acidosis and strokelike episodes; miRNAs, microRNAs; mRNA, messenger RNA; ncRNAs, non–protein-coding RNAs; rRNAs, ribosomal RNAs; snoRNAs, small nucleolar RNAs; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; tRNAs, transfer RNAs.

The proportion of non–protein-coding DNA in the genomes of higher organisms increases dramatically as a function of developmental complexity and constitutes more than 98% of the human genome. Recent studies have established that these non–protein-coding DNA sequences are pervasively transcribed, forming numerous species of ncRNAs.3 Characterization of these ncRNAs has demonstrated the existence of extensive RNA-based networks that are involved in orchestrating nearly every cellular process.4 These epigenetic networks also modulate mechanisms implicated in mediating neural injury such as excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. These diverse functions are transacted by the distinct temporal and spatial expression and function of specific ncRNAs, including those from well-known subclasses such as tRNAs and rRNAs, as well as those from recently characterized subclasses such as microRNAs (miRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs, and long ncRNAs (lncRNAs; ie, longer than 200 nucleotides). These ncRNAs form regulatory and functional networks with a broad range of effects on DNA methylation, chromatin architecture, transcriptional regulation, alternative splicing and other forms of posttranscriptional RNA processing (eg, RNA modifications, quality control, and transport), and translation.5

Non-coding RNA transcription is most active in the central nervous system (CNS), where RNA-based networks regulate a broad range of neural developmental and adult homeostatic and plasticity programs with exquisite degrees of environmental responsiveness.2,6–8 Molecules of RNA are thought to more efficiently couple bioenergetic requirements with information storage and processing compared with DNA or protein. Therefore, the advent of RNA-based networks is thought to be responsible for fueling the explosive evolutionary innovations that characterize human brain form and function.4–6,8,9 The brain is a conspicuous consumer of energy resources, and a major consequence of cerebral ischemia is the disruption of energy metabolism and exhaustion of adenosine triphosphate.10 Because RNA can rapidly be activated, modified, transported, and degraded, it serves as a highly flexible, high-fidelity, information encoding and functional molecule. The ability of RNA molecules to dynamically store, transform, and transmit both “digital” and “analog” information is a key feature of RNA-based systems.4,5,11 Conventional Watson and Crick base pairing represents digital information that uses energetically favored molecular conformations to determine canonical nucleotide hybridization rules. In addition to this digital information, RNA molecules also encode analog data captured by secondary and tertiary RNA structures, which are important for mediating interactions between RNA and protein molecules. This analog information is highly sensitive to the cellular microenvironment, which can dynamically modify the flexible structure and charge characteristics of RNA molecules influencing the geometry, stability, and stereochemistry of RNA-protein interactions. Thus, RNA can integrate both the digital lexicon of DNA and the analog language of proteins and dynamically participate with DNA and protein molecules in performing cellular activities.

RNA-BASED EPIGENETIC MECHANISMS IMPLICATED IN STROKE

ncRNAs and RNA Regulatory Networks

MicroRNAs represent the best-characterized subclass of ncRNAs. MicroRNAs regulate developmental and homeostatic gene expression programs in a highly environmentally responsive manner and are implicated in neural differentiation, maintenance, and plasticity.12 MicroRNAs are first transcribed as longer primary miRNA transcripts that can have multiple functional miRNAs embedded within a single transcript. These primary miRNAs are processed to form mature molecules of approximately 22 nucleotides that regulate the expression of large numbers of target genes through sequence-specific interactions with messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules. MicroRNAs bind to the 3′ regulatory regions and to particular coding regions of their cognate mRNAs, leading to sequestration for storage or degradation and to translational repression. Cerebral ischemia in animal models is associated with highly selective and temporally regulated profiles of miRNAs in the postischemic brain.13,14 Differential expression of miRNAs in the postischemic brain correlates with differential expression of their target mRNAs, including many implicated in transcriptional regulation, ionic flux, inflammation, and other stress responses. These results suggest that miRNA networks regulate a spectrum of processes in the postischemic brain. MicroRNA-140 is one of the miRNAs that was rapidly upregulated in the brain 3 hours after middle cerebral artery occlusion and sustained for 72 hours. One of the validated target mRNAs for miRNA-140 encodes stromal cell–derived factor 1, which plays an important role in the CNS by mediating neural progenitor cell proliferation and migration and tissue repair after cerebral ischemia.15 This observation suggests that miRNA-140 may be responsible, in part, for mitigating the regenerative response in the postischemic brain. Furthermore, some miRNAs that are highly differentially expressed in brain tissue can similarly be detected in peripheral blood,13 suggesting not only that these may serve as novel clinical biomarkers but also that these miRNAs may be involved in mediating systemic responses to cerebral ischemia.

Long ncRNAs represent another important and emerging subclass of ncRNAs that may also play a role in stroke. Long ncRNAs have roles in local and long-range chromatin remodeling, transcriptional regulation, and alternative splicing and other forms of posttranscriptional RNA processing.16 They are implicated in the development of axonal and dendritic connections and synaptic modulation associated with neural network plasticity. Long ncRNAs may also participate in the generation of the long-term potentiation that underlies learning and memory.9 An lncRNA can bind to the cyclin D1 gene, a critical mediator of ischemic neuronal cell death,17 and recruit the TLS (translocated in sarcoma) RNA-binding protein that represses transcription of the gene.18ANRIL (NCBI Entrez Gene 100048912) is an lncRNA with an unknown function that is associated with the development of atherosclerosis, diabetes, and aneurysms, possibly through effects on vascular smooth-muscle proliferation and migration.19–25GOMAFU (NCBI Entrez Gene 440823) is another lncRNA that is expressed in the nucleus of developing neural cells.26 Although the function of GOMAFU is unknown, a case-control association study identified a single-nucleotide polymorphism associated with the GOMAFU locus as a susceptibility factor for cardiovascular disease.27 In addition to miRNAs and lncRNAs, other ncRNA transcripts, such as those resembling the virus-like 30 family of interspersed, repeated, mobile genetic elements (ie, retrotransposons), are also increased in mouse brain after cerebral ischemia.28 These virus-like 30 ncRNAs are induced by ischemia and paradoxically bound to polyribosomes, although they are not translated. The distribution of these virus 30–like ncRNAs in ribosomal fractions is distinct from the distribution of mRNAs that are translated or translationally repressed and suggests a novel structural or catalytic role for these ncRNAs. Together, these observations imply that the expression and function of several newly identified subclasses of ncRNAs may be associated with the pathogenesis of stroke.

RNA Editing and DNA Recoding

Intimately linked with ncRNA expression is another epigenetic process, RNA editing, a mechanism for altering nucleotides in RNA molecules that allows the generation of significant diversity of transcripts in a highly environmental-responsive manner.8 Abnormalities in RNA editing have been implicated in a spectrum of CNS disorders, including stroke and neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases.8 Disruption of the gene encoding an RNA-editing enzyme in Drosophila melanogaster results in flies that have a very prolonged recovery time from anoxic stupor, a vulnerability to heat shock, and increased oxygen demands.29 Furthermore, in transient global cerebral ischemia models, the death of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons is mediated by selective downregulation of an RNA-editing enzyme leading to defective editing of the ionotropic glutamatergic α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionic acid GluR2 receptor subunit, which influences the vulnerability of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons to ischemia-associated cell death.30,31

By alteration of RNA nucleotides, not only does editing have the capacity to change amino acids and modulate splice-site choice in protein-coding transcripts, but it also has roles in ncRNA-related processes such as miRNA localization, target diversification, and function.32 Although RNA editing was initially studied in protein-coding transcripts, computational analyses have established that editing occurs far more frequently than previously appreciated, with most of the editing occurring in ncRNA transcripts and in untranslated regions of protein-coding transcripts.33–35 Editing of adenosine to inosine in RNA is catalyzed by a family of enzymes called adenosine deaminases that act on RNA (ADARs). These enzymes are highly active in the brain and target transcripts encoding factors involved in a broad array of neuronal processes, such as voltage-gated ion channels, ligand-gated receptors, signal transduction molecules, and apoptosis and cell-cycle regulatory proteins.8 The ADARs are differentially expressed during development, with ADAR3 restricted to brain and ADAR1 and ADAR2 preferentially expressed in the nervous system. Editing of RNA also exhibits CNS regional specificity and essential regulatory roles during neuronal maturation. Mutations in ADARs cause complex behavioral defects in Caenorhabditis elegans, D melanogaster, and mice.8

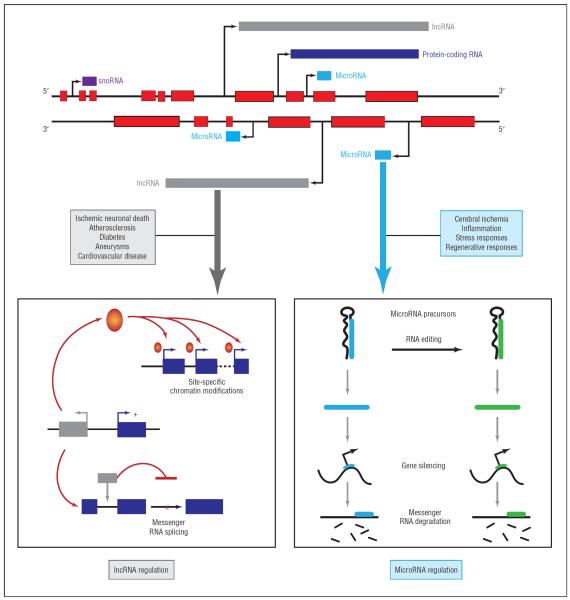

The complexity of epigenetic regulatory networks is enhanced by RNA editing, which can affect miRNA biogenesis, processing, and stability and alter mRNAs that are targeted by miRNAs.36,37 MicroRNA regulatory network dynamics mediated by RNA editing may be implicated in stroke. For example, miRNA-151 is found in neurons and upregulated after middle cerebral artery occlusion, and the immature form of miRNA-151 (primary miRNA-151) is subject to RNA editing that influences processing of the primary miRNA into mature miRNA within the CNS.38 Intriguingly, miRNA-151 is thought to target various cell-cycle regulators as well as protein tyrosine kinase 2 (focal adhesion kinase), a nonreceptor tyrosine kinase involved in integrin and growth factor signaling pathways that is differentially regulated after middle cerebral artery occlusion and implicated in modulating neurite outgrowth, neuronal plasticity, and restoration of neural network integrity within the ischemic penumbra.39–41 These observations imply that multiple layers of interleaved epigenetic controls that include RNA editing and miRNA regulatory networks are involved in stroke (Figure).

Figure.

Non–protein-coding RNA (ncRNA) transcription and ncRNA-based epigenetic regulatory processes associated with the pathogenesis of stroke. The diagram illustrates multiple interleaved and overlapping RNAs embedded within the genome, epigenetic regulatory processes mediated by ncRNAs, and stroke-associated clinical and pathological phenomena. lncRNA indicates long ncRNA; snoRNA, small nucleolar RNA.

In addition to the ADARs, the apolipoprotein B (ApoB)–editing catalytic subunit (APOBEC) family of RNA editing and DNA recoding enzymes may also play a role in stroke. These enzymes are cytidine deaminases that edit (deoxy)cytidine to (deoxy)uridine and act on RNA and DNA molecules.42 One of the substrates for these enzymes is APOB (NCBI Entrez Gene 338) mRNA, which encodes an important apolipoprotein found in chylomicrons and low-density lipoproteins. Mutations of the APOB gene and its regulatory region cause dyslipidemias (eg, hypobetalipoproteinemia and hypercholesterolemia), and genetic variants of APOBEC1 and APOBEC2 are associated with high levels of serum low-density lipoproteins and increased atherosclerosis.43 The APOBECs may affect stroke risk through effects on APOB mRNA editing; however, APOBECs may play additional roles within the brain. APOBEC-mediated DNA recoding protects the stability of the genome and also enhances its diversity and plasticity.42 Although these functions have largely been characterized within the immune system, it is intriguing that the APOBEC3 enzyme subfamily has significantly expanded in primates and that certain members (ie, APOBEC3G) are expressed in postmitotic neurons.44 Furthermore, accumulating evidence suggests that RNA editing and DNA recoding may be functionally linked through specific classes of reverse transcriptases within the CNS that can mediate RNA-directed DNA modifications.6 Also, like the immune system, the CNS exhibits exquisite degrees of functional plasticity by modulating cell identity and connectivity. Because of these observations, we have previously suggested that DNA recoding in the brain might represent a novel mechanism for transmitting productive RNA editing events back into the postmitotic neuronal genome.6 This suggests a possible evolutionary mechanism to account for the multigenerational inheritance of complex cognitive and behavioral traits and risk profiles for stroke in response to both productive and adverse environmental events.

THE ERA OF EPIGENOMIC MEDICINE

For treatment of stroke, RNA-based therapies and additional epigenetic strategies are extremely promising. Indeed, approaches for gene silencing that use short regulatory ncRNAs, including miRNAs and related short interfering RNAs (RNA interference) have already been used to identify new molecular targets for treating stroke, such as Bcl-2 and 19-kDa interacting protein 345 and carboxyterminal modulator protein46; however, RNA interference–based gene silencing for treating stroke has yet to advance beyond preliminary studies. Therapeutic approaches using other customized oligonucleotides are also being developed for modulation of endogenous RNA transcripts. For example, novel antisense oligonucleotides have now been constructed with the capacity to repair and reprogram aberrant disease-associated RNAs. The mechanism of action of these agents includes alteration of pre-mRNA processing (eg, alternative splicing) and promotion of transsplicing, which results in the creation of a composite mRNA from 2 separate pre-mRNAs.47 Although RNA-based approaches such as these are still in their infancy, they offer the potential for dynamic and highly selective reprogramming of gene expression and function.

Because of their unique properties, functional RNA molecules may be ideal candidates for a number of future therapeutic strategies. For example, through sequence-specific digital interactions with DNA, RNA-based therapeutic molecules may serve as guideposts for a certain genomic sequence. Through analog interactions with proteins, RNAs may also act as molecular beacons for recruitment of DNA methylation and histone-modifying enzyme complexes to a given genomic locus. Thus, multifunctional RNA molecules with binding domains for DNA and for these enzyme complexes may be used for targeting epigenetic modifications to a single gene locus or to multiple gene loci that harbor a shared genomic sequence. Furthermore, because RNA molecules can interact with DNA, RNAs, proteins, and small molecules, RNA-based therapeutics may also provide the flexibility and specificity necessary to selectively manipulate intricate profiles of gene transcription, posttranscriptional RNA processing, and translation by targeting epigenetic effectors such as nucleosome- and chromatin-remodeling complexes, multiple ncRNAs (eg, miRNAs and lncRNAs), and RNA editing and DNA recoding enzymes. Although these approaches have yet to be validated, the evolution of CNS drug delivery methods and rapid advances in RNA-based therapeutics, including the advent of RNA aptamers (RNA molecules engineered to bind with high affinity to specific molecular targets such as small molecules, proteins, and nucleic acids), suggest that such strategies are now possible.48

Future therapies may also be designed to target factors that serve as key modulators of CNS-specific epigenetic events and thereby promote neural cell- and tissue-selective epigenetic reprogramming. For example, these strategies may use novel agents that activate or inhibit special AT-rich sequence-binding protein 2 (SATB2), the repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor/neuron-restrictive silencing factor (REST/NRSF), and the corepressor for element-1–silencing transcription factor (CoREST). As an environmentally sensitive regulator of neuronal cell fate decisions during development,49 SATB2 modulates neuronal gene expression by promoting coordinate regulation of multiple genes on different chromosomes involved in functionally integrated gene networks. These molecular processes involve dynamic reorganization of the nuclear architecture to allow a seamless link between transcriptional and posttranscriptional processing events and associated RNA quality control mechanisms. SATB2 is also associated with a regulatory lncRNA that is coexpressed with SATB2.50 These observations suggest that therapeutic agents targeting SATB2 or its associated lncRNA could lead to dynamic reprogramming of neuronal gene expression and even neural cell identity and patterns of neural connectivity that is essential for neural regeneration. REST and CoREST are critical epigenetic factors that mediate predominantly site-specific gene repression, gene activation, and long-term gene silencing for a large spectrum of genes involved in neural development, homeostasis, and plasticity, including but not limited to those that encode growth factors, axon guidance cues, ion channels, neurotransmitter receptors, synaptic vesicle proteins, components of the cytoskeleton, and elements of the extracellular matrix.51 In addition, REST and CoREST modulate the expression of several classes of ncRNAs, including miRNAs and lncRNAs. These molecules act as dynamic modular platforms for the recruitment of a broad array of epigenetic factors to neural gene loci in which they orchestrate site-specific and genome-wide chromatin remodeling. One of the molecular mechanisms that underlie cell death after transient global ischemia is REST-dependent repression of the GluR2 subunit and μ opioid receptor 1.52,53 REST also regulates the expression of a significant number of the miRNAs that are differentially expressed after cerebral ischemia.14 These observations suggest that therapeutic targeting of REST and CoREST may have significant effects on highly integrated epigenetic regulatory mechanisms that could promote reprogramming of neural cells to enhance neural regeneration in stroke by recapitulating developmental events responsible for establishing and remodeling neural cell identity and neural network connectivity.

Additional treatment strategies may also be developed to fine-tune epigenetic mechanisms that mediate RNA modifications and trafficking within cells. Among the more salient molecular targets may be regulatory ncRNAs (eg, miRNAs and lncRNAs), RNA binding proteins, and cyto-skeletal proteins (eg, dyneins and kinesins) that have prominent roles in a diverse array of processes that are under epigenetic regulation, including alternative splicing; editing; nuclear export; stabilization; temporal, spatial, and activity-dependent localization; and translation of RNAs. For example, rationally designed small molecules that bind to miRNAs and modulate their activity are now under early-stage development, and these agents may specifically be designed to target miRNAs that are deregulated in stroke.54 Furthermore, novel therapies may act by selectively influencing the composition of complexes that carry mRNAs, ncRNAs, proteins, and other functionally related factors. These structures, referred to as RNA operons, play key roles in axodendritic transport and mediate local mRNA translation and synaptic plasticity.55 Higher-order regulatory mechanisms coordinate the dynamics of interrelated RNA operons by modulating their individual components, the kinetics of anterograde and retrograde axodendritic transport and activity-dependent deployment and function of neuronal RNAs. These mechanisms are termed RNA regulons. In postischemic neurons, vulnerability to cell death is associated with pathological alterations in RNA operon and regulon dynamics and stress responses that lead to translational arrest.56 These observations imply that manipulating RNA posttranscriptional processing may be useful in postischemic neurons to promote cellular reprogramming and to selectively activate responses that favor neuronal survival and the maintenance of neural network integrity. Furthermore, RNA operons and regulons are implicated in bidirectional axodendritic transport responsible for relaying RNA editing events from the synapse to the nucleus for DNA recoding within postmitotic neurons. Because these processes are implicated in multigenerational inheritance, therapeutic interventions targeting RNA editing events and associated recoding of the neuronal genome may be implemented to directly alter stroke risk even in future generations.

Epigenetic mechanisms are also involved in regulating cell-cell communication, including the active transport of RNAs between adjacent nerve cells through multiple signaling pathways, to more distant sites within the same tissue, to other organ systems through blood-borne routes, and even back to the germline; these processes may represent novel targets for future therapeutic initiatives.11 Specific transmembrane proteins required for the systemic spread of RNA interference are expressed in the adult brain preferentially in areas associated with learning and memory.11,57 Moreover, microvesicles (ie, exosomes) containing mRNAs and ncRNAs are produced by neural cells and secreted locally and into the peripheral circulation.58 These microvesicles may be responsible for cell-cell communication through local and more long-distance intercellular RNA transfer because they express cell recognition molecules on their surfaces for selective targeting and uptake into recipient cells, in which mRNAs may be translated and ncRNAs may exert their regulatory effects. Modulation of microvesicle composition and transport pathways may serve as novel targets for regulating anterograde and retrograde signaling across synapses, reinforcing local and long-range neural network connectivity, and signaling to other organ systems (ie, the immune system) that may play seminal roles in the pathogenesis and evolution of stroke syndromes and associated comorbidities.

As epigenetic processes begin to reveal the many previously hidden layers of functional information embedded within the genome, many future strategies can be envisioned that exploit these processes to develop novel therapies. In fact, the epigenome provides multiple layers of contextual controls that are intricately interlaced and potentially modifiable, and a single epigenetic intervention may even have a cascade of effects on many interrelated processes, including those that may be important for circumventing the pathogenesis and sequelae of stroke. For example, the DNA double helix itself has the potential to form alternative structural conformations with unique epi-genetic properties that can be harnessed for the treatment of stroke. Indeed, when the neuroprotective cytokine, colony-stimulating factor 1, is activated by the BRG1 chromatin-remodeling enzyme, a left-handed DNA stereoisomer referred to as a Z-DNA structure can be found in the region actively being transcribed.59 The formation of Z-DNA stereoisomers can, in turn, modulate a range of processes responsible for fine-tuning transcriptional events, regulating chromatin architecture, and promoting specific forms of RNA editing.60 Thus, understanding complex epigenetic mechanisms and their complementary roles in mediating CNS functions, both in health and in disease, is important for developing next-generation technologies to dynamically reprogram neural cells for treatment of complex neurological disease states, including stroke.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants NS38902 and MH66290 from the National Institutes of Health (Dr Mehler); and by the Roslyn and Leslie Goldstein, the Mildred and Bernard H. Kayden, the F. M. Kirby, and the Alpern Family Foundations.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Qureshi and Mehler. Acquisition of data: Qureshi and Mehler. Analysis and interpretation of data: Qureshi and Mehler. Drafting of the manuscript: Qureshi and Mehler. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Qureshi and Mehler. Obtained funding: Mehler. Administrative, technical, and material support: Qureshi and Mehler. Study supervision: Qureshi and Mehler.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sproule DM, Kaufmann P. Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1142:133–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1444.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehler MF. Epigenetic principles and mechanisms underlying nervous system functions in health and disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86(4):305–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, et al. ENCODE Project Consortium. NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center. Washington University Genome Sequencing Center. Broad Institute. Children's Hospital Oakland Research Institute Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447(7146):799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mattick JS. The eukaryotic genome as an RNA machine. Science. 2008;319(5871):1787–1789. doi: 10.1126/science.1155472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mehler MF. RNA regulation of epigenetic processes. Bioessays. 2009;31(1):51–59. doi: 10.1002/bies.080099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattick JS, Mehler MF. RNA editing, DNA recoding and the evolution of human cognition. Trends Neurosci. 2008;31(5):227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Non-coding RNAs in the nervous system. J Physiol. 2006;575(pt 2):333–341. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Noncoding RNAs and RNA editing in brain development, functional diversification, and neurological disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):799–823. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00036.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mariani J, Kosik KS, Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Noncoding RNAs in long-term memory formation. Neuroscientist. 2008;14(5):434–445. doi: 10.1177/1073858408319187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertz L. Bioenergetics of cerebral ischemia: a cellular perspective. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55(3):289–309. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dinger ME, Mercer TR, Mattick JS. RNAs as extracellular signaling molecules. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;40(4):151–159. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schratt G. Fine-tuning neural gene expression with microRNAs. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19(2):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeyaseelan K, Lim KY, Armugam A. MicroRNA expression in the blood and brain of rats subjected to transient focal ischemia by middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2008;39(3):959–966. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dharap A, Bowen K, Place R, Li LC, Vemuganti R. Transient focal ischemia induces extensive temporal changes in rat cerebral microRNAome. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(4):675–687. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicolas FE, Pais H, Schwach F, et al. Experimental identification of microRNA-140 targets by silencing and overexpressing miR-140. RNA. 2008;14(12):2513–2520. doi: 10.1261/rna.1221108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Mattick JS. Long non-coding RNAs: insights into functions. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10(3):155–159. doi: 10.1038/nrg2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rashidian J, Iyirhiaro G, Aleyasin H, et al. Multiple cyclin-dependent kinases signals are critical mediators of ischemia/hypoxic neuronal death in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(39):14080–14085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500099102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Arai S, Song X, et al. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454(7200):126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarinova O, Stewart AF, Roberts R, et al. Functional analysis of the chromosome 9p21.3 coronary artery disease risk locus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29(10):1671–1677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Y, Sanoff HK, Cho H, et al. INK4/ARF transcript expression is associated with chromosome 9p21 variants linked to atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2009;4(4):e5027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005027. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schaefer AS, Richter GM, Groessner-Schreiber B, et al. Identification of a shared genetic susceptibility locus for coronary heart disease and periodontitis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(2):e1000378. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000378. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broadbent HM, Peden JF, Lorkowski S, et al. PROCARDIS Consortium Susceptibility to coronary artery disease and diabetes is encoded by distinct, tightly linked SNPs in the ANRIL locus on chromosome 9p. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(6):806–814. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasmant E, Laurendeau I, Héron D, Vidaud M, Vidaud D, Bièche I. Characterization of a germ-line deletion, including the entire INK4/ARF locus, in a melanoma-neural system tumor family. Cancer Res. 2007;67(8):3963–3969. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holdt LM, Beutner F, Scholz M, et al. ANRIL expression is associated with atherosclerosis risk at chromosome 9p21. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(3):620–627. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Visel A, Zhu Y, May D, et al. Targeted deletion of the 9p21 non-coding coronary artery disease risk interval in mice. Nature. 2010;464(7287):409–412. doi: 10.1038/nature08801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sone M, Hayashi T, Tarui H, Agata K, Takeichi M, Nakagawa S. The mRNA-like noncoding RNA Gomafu constitutes a novel nuclear domain in a subset of neurons. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(pt 15):2498–2506. doi: 10.1242/jcs.009357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ishii N, Ozaki K, Sato H, et al. Identification of a novel non-coding RNA, MIAT, that confers risk of myocardial infarction. J Hum Genet. 2006;51(12):1087–1099. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costain WJ, Rasquinha I, Graber T, et al. Cerebral ischemia induces neuronal expression of novel VL30 mouse retrotransposons bound to polyribosomes. Brain Res. 2006;1094(1):24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma E, Gu XQ, Wu X, Xu T, Haddad GG. Mutation in pre-mRNA adenosine deaminase markedly attenuates neuronal tolerance to O2 deprivation in Drosophila melanogaster [published correction appears in J Clin Invest. 2001;107(9):1203] J Clin Invest. 2001;107(6):685–693. doi: 10.1172/JCI11625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peng PL, Zhong X, Tu W, et al. ADAR2-dependent RNA editing of AMPA receptor subunit GluR2 determines vulnerability of neurons in forebrain ischemia. Neuron. 2006;49(5):719–733. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tanaka H, Grooms SY, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. The AMPAR subunit GluR2: still front and center-stage. Brain Res. 2000;886(1–2):190–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02951-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blow MJ, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, et al. RNA editing of human microRNAs. Genome Biol. 2006;7(4):R27. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r27. doi:10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-r27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blow M, Futreal PA, Wooster R, Stratton MR. A survey of RNA editing in human brain. Genome Res. 2004;14(12):2379–2387. doi: 10.1101/gr.2951204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li JB, Levanon EY, Yoon JK, et al. Genome-wide identification of human RNA editing sites by parallel DNA capturing and sequencing. Science. 2009;324(5931):1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1170995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Athanasiadis A, Rich A, Maas S. Widespread A-to-I RNA editing of Alu-containing mRNAs in the human transcriptome. PLoS Biol. 2004;2(12):e391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020391. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawahara Y, Megraw M, Kreider E, et al. Frequency and fate of microRNA editing in human brain. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(16):5270–5280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang W, Chendrimada TP, Wang Q, et al. Modulation of microRNA processing and expression through RNA editing by ADAR deaminases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13(1):13–21. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kawahara Y, Zinshteyn B, Chendrimada TP, Shiekhattar R, Nishikura K. RNA editing of the microRNA-151 precursor blocks cleavage by the Dicer-TRBP complex. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(8):763–769. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim JB, Piao CS, Lee KW, et al. Delayed genomic responses to transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat. J Neurochem. 2004;89(5):1271–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimamura N, Matchett G, Yatsushige H, Calvert JW, Ohkuma H, Zhang J. Inhibition of integrin αvβ3 ameliorates focal cerebral ischemic damage in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model. Stroke. 2006;37(7):1902–1909. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226991.27540.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shani V, Bromberg Y, Sperling O, Zoref-Shani E. Involvement of Src tyrosine kinases (SFKs) and of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) in the injurious mechanism in rat primary neuronal cultures exposed to chemical ischemia. J Mol Neurosci. 2009;37(1):50–59. doi: 10.1007/s12031-008-9113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conticello SG. The AID/APOBEC family of nucleic acid mutators. Genome Biol. 2008;9(6):229. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-6-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silander K, Alanne M, Kristiansson K, et al. Gender differences in genetic risk profiles for cardiovascular disease. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3615. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003615. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang YJ, Wang X, Zhang H, et al. Expression and regulation of antiviral protein APOBEC3G in human neuronal cells. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;206(1–2):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z, Yang X, Zhang S, Ma X, Kong J. BNIP3 upregulation and EndoG translocation in delayed neuronal death in stroke and in hypoxia. Stroke. 2007;38(5):1606–1613. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.475129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miyawaki T, Ofengeim D, Noh KM, et al. The endogenous inhibitor of Akt, CTMP, is critical to ischemia-induced neuronal death. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(5):618–626. doi: 10.1038/nn.2299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wood M, Yin H, McClorey G. Modulating the expression of disease genes with RNA-based therapy. PLoS Genet. 2007;3(6):e109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030109. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan AC, Levy M. Aptamers and aptamer targeted delivery. RNA Biol. 2009;6(3):316–320. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.3.8808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gyorgy AB, Szemes M, de Juan Romero C, Tarabykin V, Agoston DV. SATB2 interacts with chromatin-remodeling molecules in differentiating cortical neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;27(4):865–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mercer TR, Dinger ME, Sunkin SM, Mehler MF, Mattick JS. Specific expression of long noncoding RNAs in the mouse brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(2):716–721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706729105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Regulation of non-coding RNA networks in the nervous system: what's the REST of the story? Neurosci Lett. 2009;466(2):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.07.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calderone A, Jover T, Noh KM, et al. Ischemic insults derepress the gene silencer REST in neurons destined to die. J Neurosci. 2003;23(6):2112–2121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02112.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Formisano L, Noh KM, Miyawaki T, Mashiko T, Bennett MV, Zukin RS. Ischemic insults promote epigenetic reprogramming of μ opioid receptor expression in hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(10):4170–4175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611704104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shan G, Li Y, Zhang J, et al. A small molecule enhances RNA interference and promotes microRNA processing. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26(8):933–940. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mansfield KD, Keene JD. The ribonome. Biol Cell. 2009;101(3):169–181. doi: 10.1042/BC20080055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeGracia DJ, Jamison JT, Szymanski JJ, Lewis MK. Translation arrest and ribonomics in post-ischemic brain. J Neurochem. 2008;106(6):2288–2301. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Feinberg EH, Hunter CP. Transport of dsRNA into cells by the transmembrane protein SID-1. Science. 2003;301(5639):1545–1547. doi: 10.1126/science.1087117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smalheiser NR. Exosomal transfer of proteins and RNAs at synapses in the nervous system. Biol Direct. 2007;2:35. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu H, Mulholland N, Fu H, Zhao K. Cooperative activity of BRG1 and Z-DNA formation in chromatin remodeling. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(7):2550–2559. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2550-2559.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang G, Vasquez KM. Z-DNA, an active element in the genome. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4424–4438. doi: 10.2741/2399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]