Abstract

Objective

To characterize prevalence and quality of life (QoL) impact of urinary incontinence (UI), fecal incontinence (FI), and pelvic organ prolapse (POP) symptoms in women of Liberia.

Methods

A questionnaire addressing symptoms and QoL impact of UI, FI and POP was administered to women in a community setting in Ganta, Liberia. Questionnaires were analyzed to determine prevalence rates, QoL impact, and risk factors for these conditions.

Results

424 participants were surveyed; 1.7% reported UI, 0.10% reported any form of FI, and 3.3% reported some degree of POP symptoms. QoL responses varied among symptom groups. Previous hysterectomy, cesarean delivery, vaginal deliveries, and body mass index had no significant association with UI, FI, or POP. Participants with UI symptoms were more likely to report FI symptoms (p=0.002).

Conclusion

Prevalence rates for UI, FI and POP in this population are low; there was a significant association of FI symptoms in subjects with UI.

Keywords: Africa, Incontinence, Prevalence, Prolapse, Quality of Life

Introduction

Urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse are common conditions of women in the United States. Prevalence rates have been characterized by large, diverse population-based studies [1] [2] [3]; however, there is little robust data characterizing the prevalence and quality of life (QoL) impact of pelvic floor disorders in women of West Africa where parity is usually, on average, higher than in the United States. [4] Fewer than 10 previous studies have been published regarding pelvic floor disorders in African countries. [5–13] While there are numerous studies relating to urinary incontinence (UI) as a result of vesico-vaginal fistula (VVF), there is little information available [13] [14] [15] on pelvic floor disorder prevalence rates and QoL impact on community dwelling women in West Africa. [16] Additionally, no studies related to pelvic organ prolapse (POP), UI or fecal incontinence (FI) are specific to Liberia, a country of nearly three and a half million people.

There are some studies that have reported that pelvic floor symptoms such as UI and POP may be not as prevalent in African American women as compared to Caucasian women. [2] [3] [17] [18] This has been attributed to factors such as physiologic or anatomic differences [17] [19] or even just lack of reporting of these symptoms. Thus, it was thought that surveying a large number of community-dwelling West African women without VVF might provide some insight regarding these reports.

The purpose of this study was to determine the prevalence and quality of life impact of urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, as well as pelvic organ prolapse symptoms in women living in Northeastern Liberia.

Materials and Methods

A questionnaire addressing symptoms of UI, FI and POP as well as the impact on quality of life was administered to reproductive-age, community-dwelling women in Ganta, Liberia, Africa during 2, two-week surgical service trips in May, 2008 and January, 2009. The purpose of the questionnaire was to assess the prevalence of urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse, as well as their potential impact on quality of life (QoL). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to collecting data.

Centralized training was performed to educate the local investigators regarding the content of the questionnaires, including lectures describing the conditions in an interactive environment prior to collecting data. Teams of individuals consisting of experienced physicians, nurses, nursing students and authors CBB, OM, KAG, HER, AMN and RT went out into villages surrounding the community of Ganta, Liberia [Figure 1] to verbally administer questionnaires.

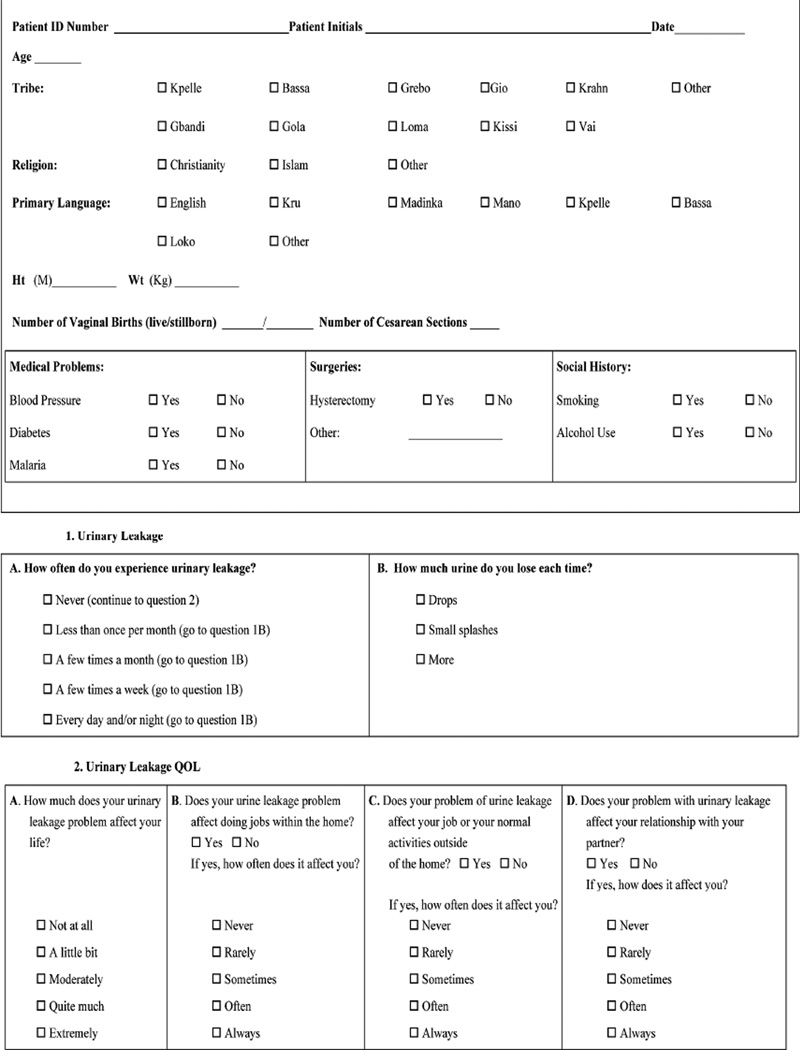

Figure 1.

Questionnaire utilized to determine prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in Northeastern Liberia

Patient demographics such as age, height, weight, number of previous live births or stillbirths, as well as the number of prior cesarean deliveries (CD) were collected. They were also asked if they had ever seen a doctor and were asked to rate their overall health, subjectively, on a scale of 1–15. In addition, the participant’s medical history (mainly consisting of diabetes, hypertension or malaria), surgical history (hysterectomy, cesarean, or prolapse repairs) and social history (alcohol and tobacco use) was obtained. Pelvic floor symptom prevalence and QoL characteristics were obtained with a questionnaire designed by combining components of the Sandvik severity questionnaire, the PFIQ-7, the PISQ-12, the PFDI-20 and the Modified Manchester questionnaires. [Figure 2] The presence of urinary incontinence was defined as an answer of “less than once a month” or more. The presence of bowel incontinence was defined as an answer of “1 to 3 times a month” or more and the presence of POP symptoms was defined as an answer of yes to the question “Do you usually have a bulge or something falling out that you can see or feel in your vaginal area”.

Figure 2.

Questionnaire utilized to determine prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in Northeastern Liberia

In addition to reviewing prevalence of pelvic floor symptoms and QoL responses, data was analyzed to determine if a relationship existed between prior hysterectomy, cesarean delivery, number of vaginal births, and body mass index (BMI) on the prevalence of UI, FI, and POP symptoms. Each characteristic was tested individually, with Fisher’s exact test for hysterectomy and cesarean delivery history, and logistic regression for vaginal births and BMI. The Bonferroni correction was used to adjust an overall 0.05 level of significance for multiple comparisons, with a p-value ≤ 0.004, considered significant. The relationships between UI, FI, and POP were also examined with Fisher’s exact test. Data was analyzed utilizing SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC).

Results

A total of 424 patients were surveyed; select characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1. Of the 424 patients surveyed, 9.7% reported a history of hypertension, 2.4% reported a history of diabetes, and 59.9% reported infection with malaria. Hysterectomy was reported in 3.5% of the population while 14.2% reported a previous cesarean. Less than 1% reported tobacco use, but 40.6% reported regular alcohol intake.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Population

| Characteristic | Distribution mean (SD) unless otherwise noted |

|---|---|

| Age (n = 413) | 36.5 (15.5) |

| Religion (n = 241) | |

| Christian | 195 (81%) |

| Islam | 1 (0.4%) |

| Other | 45 (19%) |

| Language (n = 396) | |

| English | 6 (1.5%) |

| Kru | 0 (0.0%) |

| Madinka | 0 (0.0%) |

| Mano | 303 (76.5%) |

| Kpelle | 2 (0.5%) |

| Bassa | 0 (0.0%) |

| Loko | 0 (0.0%) |

| Other | 2 (0.5%) |

| English & Mano | 79 (20.0%) |

| Multiple Languages | 4 (1.0%) |

| Health Score* (n = 400) | 11.9 (3.1) |

| Live Births (n = 365) | 4.4 (3.4) |

| Prior Cesarean Delivery (n = 232) | 60 (25.9%) |

| Stillborn (n = 180) | 1.9 (2.2) |

| BMI (n = 217) | 22.7 (5.0) |

Respondents were asked to rate their overall health on a scale of 1–15

Seven subjects (1.7%) reported urinary incontinence with less than half of these (N=3) reporting daily leakage. QoL responses revealed that of these 7 individuals suffering from UI, greater than 85% (N=6) reported a major impact on their QoL, meaning their response to the 5-point Likert scale QoL impact question was either “quite much” or “extremely” bothered. In fact, 5 of these individuals reported an impact so severe that it affected their ability to do their daily work, even inside the home. In addition, 71.4% of individuals suffering from UI reported that incontinent episodes were affecting their relationship with their partner.

Four participants (<1%) reported flatal incontinence, with one of these participants also reporting both incontinence of solid and liquid stool at least one time per week. QoL responses revealed that, of the 4 individuals reporting flatal incontinence, half reported no affect on their daily lives. When subjects were asked if they had a bulge or something falling out that they could see or feel in the vaginal area, a total of 14 respondents (3.3%) reported some symptom of pelvic organ prolapse. Responses for this question were not further characterized to label the degree or type of prolapse. QoL responses revealed that 42.8% (N=6) of these 14 respondents quoted moderate to severe QoL impact with regard to their pelvic organ prolapse.

Despite the low prevalence rates, we wished to explore potential factors associated with the presence of UI, FI and POP symptoms. These included previous hysterectomy, number of vaginal deliveries, presence or absence of previous CD, BMI as well as concomitant complaints (FI, POP). Logistic regression determined that neither BMI nor the number of prior births had a significant association with UI, FI, or POP. Analysis using Fisher’s exact test revealed that neither previous hysterectomy nor previous CD was associated with the prevalence of our outcomes. Of the 7 women with UI, 2 also reported FI, indicating a strong relationship between these two outcomes (p = 0.002). However, this association should be interpreted cautiously because of the low prevalence of these outcomes.

Discussion

Urinary and fecal incontinence are reasonably prevalent conditions in women in the industrialized world and have been well characterized by well-designed, large, population-based studies of diverse patient populations. [1] [2] [3] However, these studies have not determined the impact of these symptoms on quality of life. The prevalence and impact on quality of life of urinary and fecal incontinence as well as pelvic organ prolapse are not well described in the developing world, specifically Northeast Liberia. The prevalence rates for UI, FI and POP in this parous population in Liberia were quite low. Of those subjects with symptoms, 85% of those with UI reported major QoL issues, while only 50% of those with FI and 43% of those with POP reported QoL impact. Factors such as previous hysterectomy, previous CD, number of prior vaginal deliveries, and BMI did not appear to affect the risk of developing pelvic floor symptoms in this population. However, because of the low prevalence of UI, FI, and POP reported, this study is underpowered to detect these relationships if they truly exist. A larger study is recommended to further explore these effects.

This report suggests that the prevalence of these pelvic floor disorders is low relative to prevalence figures for the United States, where UI prevalence rates range from 5–75% [1] [20] [21], FI prevalence rates range from 2.2–24.0% [1] [22] [23] [24] and POP symptom prevalence rates can approach 75%. [1] [25] [26] However, the subjects of this report were also younger (in a country where the lifespan is not as long) and less obese than those population-based studies in the United States. Multiple studies have demonstrated lower prevalence rates for POP, UI and FI in African-Americans compared to Caucasian counter-parts. [2] [3] [17] [18] [27] As noted in these reports, factors such as physiologic or anatomic differences or even a lack of reporting of these symptoms may be the cause for this finding. The subjects of this report carry large amounts of weight on the heads or on their backs from an early age, perhaps leading to a more robust pelvic floor muscle complex. Additionally, the overall lack of reporting noted as a possible cause of decreased prevalence rates in other studies [17] may be disproportionately increased in this African population, where women may find themselves even less likely to respond to such intimate questions with outsiders. This is certainly a potential weakness in our study.

Another weakness of the study includes a potential communication barrier. Although English is the official language of the country, there are many participants that spoke local languages, the most popular being Mano. Although native Liberian citizens administered the questionnaires, some of the terms and ideas may have been foreign to the participants. To lessen this possibility the survey underwent several revisions prior to administration to be as simple, culturally appropriate and straight forward as possible. Participants may have been embarrassed or afraid to respond honestly; however, we do not believe this to be the case as the questionnaires were administered in private, usually within the participant’s home with no other observers.

This study finds strength in moderately large numbers, being drawn from a group of local, community-dwelling women. It serves as a novel report on an understudied subject and population. Another strength is the use of a modified questionnaire based on validated questionnaires to investigate QoL impact in this population in addition to reporting the overall prevalence. Quality of life impact is an important field of research in women’s health, and women in more impoverished areas should not be excluded. The culture of this region may or may not have an influence on how these symptoms are interpreted as compared to industrialized countries where they were validated. It is not ideal to lift single questions or modify them from a validated questionnaire, but in the interest of time constraints with these subjects, this was performed. Also as alluded to above, although the questions were obtained from or based on validated instruments, they were validated with responses from women in the United States, not Liberia, which may not translate into the same understanding and impact of these conditions.

In reflecting on the cultural differences and prevalence rates between Liberian women, compared to American women, it may be that questionnaires used to characterize these conditions in the United States may not accurately reflect the condition in Liberia. Further studies with questionnaires validated specifically for this population could potentially yield different findings.

Footnotes

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Synopsis: Prevalence and symptomatology of urinary and fecal incontinence and prolapse are not well described in Liberia. The prevalence of these conditions appears low in this population.

References

- 1.Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of Symptomatic Pelvic Floor Disorders in US Women. JAMA. 2008;300:1311–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.11.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the women's health initiative: Gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1160–1166. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.123819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grodstein F, Fretts R, Lifford K, Resnick N, Curhan G. Association of age, race, and obstetric history with urinary symptoms among women in the Nurses' Health Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(2):428–434. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00361-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kollehlon KT. Religious Affiliation and Fertility in Liberia. J Biosoc Sci. 1994;26(4):493–507. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000021623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mawajdeh SM, Al-Qutob RJ, Farag AM. Prevalence and risk factors of genital prolapse. A multicenter study. Saudi Med J. 2003;24(2):161–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lukman Y. Utero-vaginal prolapse: a rural disability of the young. East Afr Med J. 1995;72:2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ojwang SB. Genital prolapse as a problem in rural community. East Afr Med J. 1995;72:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Younis N, Khattab H, Zurayk H, el-Mouelhy M, Amin MF, Farag AM. A community study of gynecological and related morbidities in rural Egypt. Stud Fam Plann. 1993;24(3):175–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goman HM, Fetohy EM, Nosseir SA, Kholeif AE. Perception of genital prolapse: a hospital-based study in Alexandria (Parts I and II) J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2001;76:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okonkwo JE, Obiechina NJ, Obionu CN. Incidence of pelvic organ prolapse in Nigerian women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2003;95:132–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wusu-Ansah OK, Opare-Addo HS. Pelvic organ prolapse in rural Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103:121–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ugboma HA, Okpani AO, Anya SE. Genital prolapse in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2004;13(2):124–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okonkwo JE, Obionu CO, Obiechina NJ. Factors contributing to urinary incontinence and pelvic prolapse in Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;74(3):301–303. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(01)00378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Azab AS, Mohamed EM, Sabra HI. The prevalence and risk factors of urinary incontinence and its influence on the quality of life among Egyptian women. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:783–788. doi: 10.1002/nau.20412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Muijsenbergh ME, Lagro-Janssen TA. Urinary incontinence in Moroccan and Turkish women: a qualitative study on impact and preferences for treatment. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:945–949. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okonkwo JE, Obionu CN, Okonkwo CV, Obiechina NJ. Anal incontinence among Igbo (Nigerian) women. Int J Clin Pract. 2002;56:178–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rortveit G, Brown JS, Thom DH, Van Den Eden SK, Creasman JM, Subak LL. Sypmtomatic Pelvic Organ Prolapse: Prevalence and Risk Factors in a Population-Based, Racially Diverse Cohort. Obstet & Gynecol. 2007;109:1396–1403. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000263469.68106.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelan S, Kanaya AM, Subak LL, Hogan PE, Espeland MA, Wing RR, Burgio KL, Dilillo V, Gorin AA, West DS, Brown JS. Prevalence and risk factors for urinary incontinence in overweight and obese diabetic women: action for health in diabetes (Look Ahead) study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1391–1397. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howard D, Delancey JOL, Tunn R, Ashton-Miller JA. Racial Differences in the Structure and Function of the Stress Urinary Continence Mechanism. Obstet & Gynecol. 2000;95:713–717. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00786-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melville JL, Delaney K, Newton K, Katon W. Incontinence severity and major depression in incontinent women. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:585–592. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000173985.39533.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swithinbank LV, Abrams P. The impact of urinary incontinence on the quality of life of women. World J Urol. 1999;17:225–229. doi: 10.1007/s003450050137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson R, Norton N, Cautley E, Furner S. Community-based prevalence of anal incontinence. JAMA. 1995;274:559–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Halli AD, Jones RW, Richter HE, Redden DT, Baker PS, Allman RM. Prevalence and Correlates of Fecal Incontinence in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. JAGS. 2005;53:629–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varma MG, Brown JS, Creasman JM, Thom DH, Van Den Eden SK, Beattie MS, Subak LL. Fecal Incontinence in Females Older Than Aged 40 Years: Who is at Risk? Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:841–851. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0535-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swift S, Woodman P, O’Boyle A. Pelvic Organ Support Study (POSST): the distribution, clinical definition, and epidemiologic condition of pelvic organ support defects. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:795–806. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samulesson EC, Victor FT, Tibblin G, Svardsudd KF. Signs of genital prolapse in a Swedish population of women 20 to 59 years of age and possible related factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:299–305. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70203-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fultz NH, Herzog AR, Raghunathan TE, Wallace RB, Diokno AC. Prevalence and Severity of Urinary Incontinence in Older African American and Caucasian Women. Journal of Gerontology. 1999;54:299–303. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.6.m299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]