Abstract

Genetic variation influences the response of an individual to drug treatments. Understanding this variation has the potential to make therapy safer and more effective by determining selection and dosing of drugs for an individual patient. In the context of cancer, tumours may have specific disease-defining mutations, but a patient’s germline genetic variation will also affect drug response (both efficacy and toxicity), and here we focus on how to study this variation. Advances in sequencing technologies, statistical genetics analysis methods and clinical trial designs have shown promise for the discovery of variants associated with drug response. We discuss the application of germline genetics analysis methods to cancer pharmacogenomics with a focus on the special considerations for study design.

Pharmacogenomics aims at understanding how genetic variants influence drug efficacy and toxicity. Such studies can reveal how genetic variation across individuals affects a drug’s pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. If the associations of genotypes with drug-induced phenotypes are reproducible and have large effect sizes, clinical use of such information can be implemented for patient benefit. This is particularly important in oncology because cancer is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in industrialized nations, and failed treatment is often life-threatening. The ability to predict how a cancer patient will respond to a particular treatment regimen is the ambitious goal of personalized oncology.

Although some somatic mutations in a tumour can define a patient’s disease and thus the treatment choice (BOX 1), the study of germline genetic variation is the focus of this Review. This germline variation, which is present in the patient’s normal tissues, will affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a cancer drug independently of the disease type. Whatever germline variation affects development of disease may also contribute to individualized responses to anticancer agents.

Box 1. Somatic mutations in cancer pharmacogenomics.

Somatic mutations may be the drivers that define the cancer subtype, or they may simply be passengers. Tumour samples are a mixture of cancer and normal cells, and this must be accounted for when calling somatic mutations in DNA-sequencing studies96. Tumour samples are often small biopsies that are formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE), and thus DNA is partially degraded, so extra care must be taken to determine whether a sample is amenable to genomic analysis96. The mutations within the cancer cells may also be heterogeneous: that is, different sections of the tumour may be derived from different clonal expansions97–99. The branched nature of tumour evolution is just beginning to be studied in detail, but the current recommendation for dealing with this heterogeneity in terms of treatment is to target ubiquitous alterations in the trunk of the phylogenetic tree if such targeted drugs are available98. Targeted therapies have been developed against some of the proteins (often tyrosine kinases) that are activated by somatic mutations.

Pathway considerations are important when examining somatic mutations to identify an appropriate targeted therapy. For instance, activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signalling in lung cancer can occur through mutations in multiple different genes within the pathway in addition to mutations in EGFR itself100. The International Cancer Genome Consortium and the Cancer Genome Atlas are conducting large-scale genome studies in thousands of tumours from more than 50 cancer types at the genome, transcriptome and epigenome levels to define somatic driver mutations101–103. In addition to defining somatic mutations, integrative studies of global mRNA and methylation patterns may reveal new clinically relevant disease subtypes for prognosis and therapeutic management. These large-scale sequencing projects plan to make the genomic data publicly available, and data have already been used to identify possible therapeutic inhibitors of genes that are amplified in ovarian cancer103. For some targeted therapies, specific somatic mutations are predictive of treatment efficacy104–111, and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) notes these associations in the drug labels, as summarized in the table. Data in the table are taken from the FDA website.

| Drug | Drug target | Cancer type (or types) | Somatic markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cetuximab | EGFR | Colorectal, head and neck | EGFR and KRAS |

| Erlotinib | EGFR | Lung, pancreatic | EGFR |

| Exemestane | Aromatase | Breast | ESR1, ESR2 and PGR |

| Gefitinib | EGFR | Lung | EGFR |

| Imatinib | BCR–ABL, KIT and PDGFRa tyrosine kinases | Chronic myeloid leukaemia, gastrointestinal | Philadelphia chromosome, KIT and PDGFRA |

| Lapatinib | ERBB2 receptor | Breast | ERBB2 |

| Letrozole | Aromatase | Breast | ESR1, ESR2 and PGR |

| Panitumumab | EGFR | Colorectal | EGFR and KRAS |

| Tamoxifen | Oestrogen receptor | Breast | ESR1, ESR2 and PGR |

| Trastuzumab | ERBB2 receptor | Breast, stomach | ERBB2 |

Because somatic mutations can sometimes define disease subtypes, they may be important covariates if different tumour types are combined in a germline pharmacogenomic analysis. In addition, germline DNA variation may control which somatic mutations a tumour is likely to acquire. One study found that squamous cell carcinomas that independently arose were more similar within than among individuals, demonstrating that germline genetic background probably affects patterns of somatic change112. Therefore, somatic mutations have been used as endophenotypes to test for germline genetic variants that confer risk for obtaining specific somatic mutations113–117. For example, functional germline variants in EGFR may be associated with EGFR somatic mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer117. BCR–ABL, oncogenic fusion gene; ERBB2, also known as HER2 or NEU; ESR1, oestrogen receptor 1; PDGFRα, platelet-derived growth factor subunit-α.

The current treatment for most cancers includes using cytotoxic chemotherapy, which is not precisely targeted to the somatic mutations that drive malignant transformation as such driver mutations are unknown for most patients. Studies of cell line pedigrees treated with various chemotherapeutic agents have shown that some cytotoxic effects are probably heritable1–3. Variations in the toxicities and responses experienced by cancer patients have led researchers to search for germline genetic variants associated with chemotherapy-induced phenotypes. One well-described example is that the standard dose of mercaptopurine (which is a treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)) results in life-threatening toxicity for individuals with certain variant alleles of thiopurine S-methyltransferase (TPMT)4–6. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now recommends genotyping of TPMT, and individuals with inactive alleles are often successfully treated with reduced doses of mercaptopurine4,7,8. Additional key germline genetic variants that are associated with cancer-drug-induced phenotypes are shown in TABLE 1.

Table 1.

Examples of germline genetic variants associated with cancer-drug-induced phenotypes

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Cancer type (or types) | Genes | Variants | Phenotype | Type of study | Evidence | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercaptopurine | Antimetabolite that inhibits purine nucleotide synthesis (involved in DNA replication) | Paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | TPMT | rs1142345 rs1800460 rs1800462 rs1800584 |

Myelosuppression | Candidate gene | FDA label recommends genotyping | 5–7 |

| Irinotecan | Inhibits topoisomerase I (involved in DNA replication and transcription) | Colorectal, lung | UGT1A1 | rs8175347 | Neutropoenia, diarrhoea | Candidate gene | FDA label recommends genotyping | 9,32,123 |

| Tamoxifen | Inhibits the oestrogen receptor | Hormone-receptor-positive breast | CYP2D6 | rs16947 rs1065852 rs28371706 rs28371725 rs35742686 rs3892097 rs5030655 rs5030656 rs59421388 rs61736512 |

Tamoxifen metabolism, progression-free and overall survival | Candidate gene | Conflicting results may be due to study design and quality control; studies are ongoing | 10,16–19, 46–48 |

| Methotrexate | Antimetabolite that inhibits folic acid metabolism (involved in DNA replication) | Paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia | SLCO1B1 | rs11045879 | Methotrexate clearance, gastrointestinal toxicity | GWAS | Association was genome-wide-significant; replicated in multiple cohorts; in vitro functional evidence | 15,60,76 |

The table shows key germline genetic variants associated with cancer drug-induced phenotypes with replication in multiple cohorts and strong functional evidence. CYP2D6, CYP2D6 cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily D polypeptide; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration; GWAS, genome-wide association study; SLCO1B1, solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1B1; TMPT, thiopurine S-methyltransferase; UGT1A1, UDP glucuronosyltransferase 1 family, polypeptide A1.

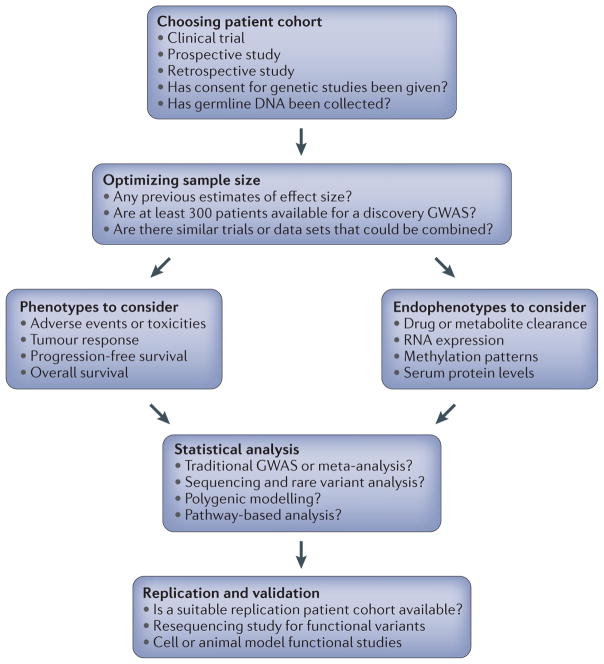

Cancer pharmacogenomic studies have challenges in addition to those common to other pharmacogenomic studies. Optimizing the design at the outset of a cancer pharmacogenomics study will increase confidence in the findings, and the aim of this article is to provide information about study design and analytical options. FIGURE 1 summarizes the steps that will be discussed. Briefly, we look at commonly used designs, including those incorporated into oncology clinical trials, potential confounders and examples of pharmacogenomic findings that have stemmed from such trials. We discuss factors affecting the consistency of cancer pharmacogenomic studies and summarize key phenotypes and endophenotypes to consider. We also summarize recent findings from preclinical models that can potentially address some of the limitations of clinical pharmacogenomic studies. We end with a discussion of how integration of new genomic technologies and statistical analysis methods into anticancer agent clinical trials may aid in pharmacogenomic marker discovery.

Figure 1. Steps in cancer pharmacogenomic study design.

This flow diagram outlines the main steps in a cancer pharmacogenomic study design. In addition to making these key decisions, potential covariate data should be collected, as discussed in BOX 2. GWAS, genome-wide association study.

Overview of design options and challenges

Designs

The candidate gene approach has often been used in cancer pharmacogenomics6,9,10; variants in known drug-metabolizing enzymes and drug targets are tested for association with phenotypes of interest. Genotyping arrays containing hundreds of SNPs in known drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination (ADME) genes — such as the Affymetrix DMET chip and the Illumina VeraCode ADME Core Panel — can be useful in pharmacogenomic candidate gene studies11,12. Of course, the candidate gene approach requires a priori biological knowledge and will miss unknown regions of association, but the candidate gene approach may still have merit in cancer pharmacogenomics when patient sample sizes are limited, particularly if pharmacokinetic data are also available. However, as genotyping and sequencing costs continue to decline, every effort should be made to carry out comprehensive genome-wide analyses to make the best use of available patient samples.

Clinical trials offer the ideal infrastructure for pharmacogenomic studies because of their consistent drug dosing and phenotype collection. Phase I trials are designed to determine the maximum tolerable dose of a new drug, and Phase II trials estimate the effectiveness of the drug to determine whether it should proceed to Phase III. The sample sizes of Phase I and II trials in oncology are often less than 100 individuals and thus are seldom amenable to genome-wide pharmacogenomic discovery studies, but they may be useful in candidate gene studies. Comparative Phase III trials often involve hundreds to thousands of patients and are thus useful sources of data for genome-wide association studies (GWASs). Prospective cancer pharmaco genomic studies can also be designed separately from clinical trials, but care should be taken to ensure that consistent dosing regimens and phenotype and covariate collection procedures are followed. Retrospective studies are possible and may allow a larger sample size, but inconsistent treatments and data collection may confound results.

Challenges

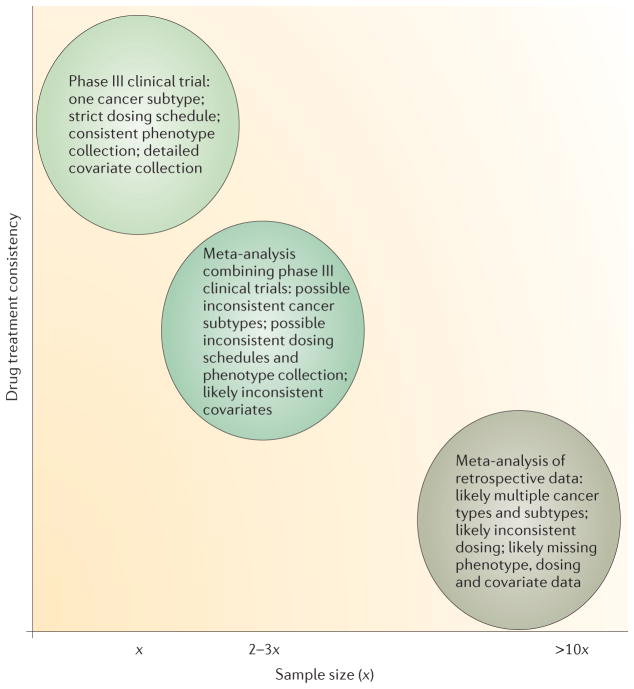

Challenges in cancer pharmacogenomic studies abound. Cancer patients are often treated with combinations of drugs, so large samples of patients treated with a single agent are rare. In addition, the dosage of the drug may vary by regimen or indication, further complicating efforts to study the pharmacogenomics of a specific drug of interest. Furthermore, replication of discovery findings made in a GWAS from a large randomized clinical trial is often difficult, because high costs and ethical considerations may mean that a second identical trial is not feasible. Furthermore, when data from multiple studies are combined, the potential for confounding variables increases (FIG. 2). Negative results in cancer pharmacogenomic studies are abundant, and reasons may include inadequate sample size, genotyping error, lack of inclusion of the causal genetic variation, phenotypic error or true absence of an effect. The following sections discuss optimizing the design of cancer pharmacogenomic studies to detect true associations (FIG. 1).

Figure 2. Negative relationship between sample size and drug treatment consistency in cancer pharmacogenomics.

To test for replication of findings from preliminary genome-wide association studies (GWASs), it is necessary to combine data sets from multiple trials and retrospective patient collections. Therefore, the phenotype and covariate data become less consistent, increasing the potential for confounding variables. The sample size (x) will vary depending on the prevalence of the type of cancer under study and the prevalence of the drug’s use when collecting retrospective data, but often x is ~1,000.

Planning a study

Choosing a patient cohort

Ideally, patients in both candidate gene studies and GWASs will have been treated with a single oncology drug so that phenotypic effects can be attributed to the drug of interest. In addition, standardized dosing and scheduling of administration are important, as variation in dose affects any drug-related phenotype. Specific drug-dosing schedules are used in prospective clinical trials, providing consistent and well-maintained drug data for pharmacogenomic studies. However, treatment arms on such trials may include multiple therapies, which may or may not be of the same drug class.

To increase the sample size for a particular phenotype, it may be useful to combine data from treatment arms of a clinical trial and then to control for potential confounding owing to treatment differences in the statistical analysis. This strategy has been successful in a GWAS of musculoskeletal toxicity induced by aromatase inhibitors used to treat breast cancer13 and a GWAS of overall survival of pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine14 (TABLE 2). The clinical trial comparing the two aromatase inhibitors is an example of a drug A versus drug B trial design. To account for potential differences in outcome between the two drugs, each musculoskeletal toxicity case was matched to two controls on the basis of treatment arm and other variables in a nested case–control design13. The pancreatic cancer trial is an example of a drug A versus drug A + B trial design. In this type of trial, a new agent is often added to the current standard of care. Here, patients with advanced pancreatic cancer were treated with gemcitabine plus either bevacizumab or a placebo. Testing a treatment arm covariate in the statistical model was used to control for potential differences in outcome when the data were combined in a GWAS for overall survival14. In this case, the top variant may have a prognostic effect for pancreatic cancer because stratification by treatment arm does not negatively affect the variant’s association with overall survival14.

Table 2.

Clinical studies discussed in this Review

| DNA source | Clinical trial format | Number of patients (n) | Phenotypes tested | Top SNPs and P values | Replication? | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood after ALL remission | Three standard methotrexate plus 6-mercaptopurine (both of which are antimetabolites) paediatric ALL treatment regimens were followed; GWAS | Discovery n = 434; initial study replication n = 206; additional study replication n = 115 | Methotrexate clearance | rs11045879 in SLCO1B1 (P = 1.7 × 10−10) | rs11045879 in SLCO1B1 (P = 0.018 initial study; P = 0.030 additional study) | 15,60 |

| Blood | Drug A versus drug B; patients with breast cancer treated with one of two aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole versus exemestane); GWAS | Cases n = 293; controls matched to treatment arm and other covariates n = 585 | Musculoskeletal toxicity | rs11849538 near 3′ end of TCL1A (P = 6.7 × 10−7) | No replication in patients, but the risk allele creates an oestrogen response element, and extensive in vitro functional evidence implicates the locus | 13,61 |

| Blood | Drug A versus drug A + B; patients with pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine (an antimetabolite) alone or in combination with bevacizumab (a VEGF inhibitor); GWAS | n = 351 (combined treatment arms because no difference in overall survival was observed) | Overall survival | rs7771466 in IL17F (P = 2.6 × 10−8) | None | 14 |

| CML samples | Not a clinical trial: compared patient CML samples that were sensitive or resistant to imatinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) using paired-end whole-genome sequencing to identify structural variants | Initial sequencing study: sensitive n = 2 and resistant n = 3; CML replication cohort n = 203; NSCLC replication cohort n = 141 | Resitance to TKIs; progression- free survival in NSCLC patients treated with TKIs | A deletion in BIM was common to the resistant samples and not present in the sensitive samples; found to be a germline polymorphism after screening 2,597 healthy individuals (12.3% carrier frequency in East Asians) | BIM deletion associates with TKI resistance in CML patients (P = 0.02) and shorter progression-free survival in NSCLC patients (P = 0.03); extensive in vitro functional evidence implicates the locus | 62 |

| Blood after ALL remission | Follow-up to the study described in REF. 15; deep resequencing of SLCO1B1 | n = 699 | Methotrexate clearance | Nonsynonymous SNPs, including common and rare variants, that were predicted to be functionally damaging were more likely to be found in patients with lower methotrexate clearance | None | 76 |

| Blood | Drug A versus drug B; patients with breast cancer treated with either cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin or paclitaxel; GWAS of the paclitaxel treatment arm only | European discovery n = 855; European replication n = 154; African–American replication n = 117 | Paclitaxel- induced sensory peripheral neuropathy | rs10771973 in FGD4 (P = 2.6 × 10−6) | rs10771973 in FGD4 (P = 0.013 European replication; P = 6.7 × 10−3 African–American replication) | 22 |

ALL, acute lymphoid leukaemia; BIM, also known as BCL2L11; CML, chronic myeloid leukaemia; FGD4, FYVE, RhoGEF and PH domain containing 4; GWAS, genome-wide association study; IL17F, interleukin 17F; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; SLCO1B1, solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1B1; TCL1A, T cell leukaemia/lymphoma 1A; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Depending on the drug and phenotypes of interest, it may be possible to include a heterogeneous population (for example, including multiple diseases or doses). For example, a successfully replicated GWAS of methotrexate clearance combined data from ALL patients on three different dosing regimens that included different drug combinations; these differences were accounted for by using treatment regimen as a categorical covariate in the statistical analysis15 (TABLE 2). The success of this study is probably due to the use of the endophenotype of drug clearance, which is likely to be less affected by concomitant drugs than some other phenotypes would be.

DNA source

For germline cancer pharmacogenomic studies, normal DNA is easy to obtain from blood or, in the case of patients with blood cancers, saliva. Because tumour samples are a mixture of cancer and normal cells, formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsy samples should generally be avoided as a source of DNA for germline studies. In one recent large study that attempted to replicate the associations between variants in CYP2D6 (which encodes a cytochrome P450 enzyme) and tamoxifen-related phenotypes10,16,17, DNA was extracted from tumour tissue in FFPE blocks18, and SNPs in CYP2D6 showed massive departures from the Hardy– Weinberg equilibrium (HWE)19. In this case, the deviation from HWE was consistent with a large proportion of hemizygous deletions of CYP2D6 in the tumour tissue from which the DNA was extracted19. Thus, the tumour tissue did not reliably reflect the germline genotype, greatly limiting interpretation of this data set.

Although the use of FFPE DNA for assessment of germline genotype is fraught with hazard, there are many well-phenotyped cancer patient data sets for which only FFPE DNA is available20. Therefore, just as phenotyping stringency may be relaxed to increase sample size, researchers may choose to relax genotyping stringency and to use FFPE-derived genotypes. Using FFPE genotypes is only feasible if the DNA quality is high, if the percentage of failed variant calls is extremely low (that is, on a level comparable with blood-derived genotypes) and if there is strong reason to believe that the region of interest does not contain point mutations, deletions (that is, loss of heterozygosity, as was the case in the CYP2D6 study18,19) or amplifications. Importantly, the source of DNA should always be noted in publications so that readers are aware of potentially inaccurate genotypes that may confound results. The CYP2D6 study18,19 highlights the need for close collaboration among statistical geneticists, genotyping laboratories and clinical investigators to ensure appropriate quality control and genetic analysis in cancer pharmacogenomic studies.

Optimizing sample size

The appropriate sample size will depend on the expected effect sizes of the genetic variants as well as the number of variants to be tested (that is, whether a candidate gene study or a GWAS is being carried out). In discovery GWASs, expected effect sizes are unknown, and thus large sample sizes (for example, thousands of individuals in a treatment group) are necessary to detect common variants with small effect (odds ratios from 1.1 to 2), as are often observed in disease-susceptibility GWASs21. Whereas technological advances in genotyping technologies have decreased costs and allowed larger sample sizes, pharmacogenomic GWAS sample sizes have typically ranged in the hundreds13–15,22. Efforts to increase the size of clinical trials would help to detect small effect size associations, but this is not always possible if the frequency of use of a particular drug is low. In addition, current clinical trials are powered to detect differences in outcome among treatments, not genetic associations. However, several pharmacogenomic GWASs involving ~100 cases have detected statistically significant associations, suggesting that the effect sizes for some drug-induced phenotypes are much larger and involve fewer genes than those detected in GWASs for complex disease susceptibility23. For example, genome-wide-significant associations of genetic variants in solute carrier organic anion transporter family, member 1B1 (SLCO1B1) with myopathy induced by the cholesterol-lowering drug simvastatin were identified in a discovery GWAS cohort of 85 cases and 90 controls owing to the large effect size (odds ratio = 4.5) of the risk allele24. This association has since been replicated in additional cohorts24,25. Cancer pharmacogenomic GWASs have shown promising results with samples sizes in the hundreds (TABLE 2), but replication is still an issue for many studies. Currently, there simply are not enough well-phenotyped patient data sets for most cancer drugs under investigation to make replication studies feasible, especially when effect sizes are small. Alternative approaches are discussed in later sections.

Key cancer phenotypes

Our definition of phenotype in cancer pharmacogenomic studies refers to overt clinical phenotypes, such as adverse events and measures of efficacy. Selection of phenotypes is a crucial step in the execution of a strong pharmacogenomic study. For cancer studies, especially in retrospective analysis of large trials, selection of phenotypes has been a fundamental challenge. Here we describe the phenotypes that are typically available from clinical trials and the development of tools that may allow more effective and efficient studies of cancer pharmacogenomics.

For patients in cancer trials, clinicians typically rate the severity of treatment toxicities according to standardized ordinal scales such as the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) developed by the US National Cancer Institute and used in most international studies. CTCAE has been useful for managing the safety of new anticancer agents in clinical trials and provides investigators and clinicians with a generally uniform reference for the relative toxicity of different agents and treatment regimens. However, clinicians vary in the rigour and expertise with which they rate the severity of adverse events among their patients, and the recording of graded toxicity is infrequent outside clinical trials. For some adverse events, quantitative information is compressed into ordinal categories; for others, the rating is dependent on the action the physician chooses to take rather than the intrinsic severity of the event, and for others, well-validated scales of symptom rating26 that work better than the CTCAE scales are available. Therefore, although CTCAE data may be a phenotype of convenience, efforts to find germline genetic associations can yield results that are not reproducible, possibly owing to differences in the phenotyping. Thus, accessing primary quantitative data (for example, blood pressure measurements instead of the CTCAE hypertension rating) or prospectively incorporating validated symptom-reporting scales26 is preferred.

Despite their limitations, CTCAE ratings have successfully been used as phenotypes to identify germline genetic predictors of toxicities in patients13,22. As was done in these studies, investigators should familiarize themselves with the empiric observations and actions of the clinicians who have conducted the phenotyping to identify robust pharmacogenomic markers of adverse events. Frequently, investigators can identify a clinically relevant threshold level for defining adverse events on the CTCAE scale. Collaborations among the geneticists, pharmacologists and clinicians involved in the study with some familiarity with the cross-disciplinary analytical principles can be essential to cancer pharmacogenomic toxicity studies.

Clinical investigators usually rely on another categorical system to evaluate effects of treatment on disease: the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST). RECIST was developed to standardize assessment of tumour response in patients enrolled in clinical trials27. Typically, computed tomography (CT or ‘CAT scan’) images are used, and the single longest dimension of each of several tumour masses is measured before and at intervals after the initiation of treatment. The change in tumour size at each interval is categorized as complete response, partial response, stable disease or progressive disease27. Progression-free survival is quantified as the time on treatment until there is an increase in tumour burden. The drawbacks of this approach towards assessing tumour burden have been described elsewhere28–30. Given the complexity of this efficacy phenotype, most efforts to detect associations will be underpowered and difficult to replicate. Furthermore, the most important clinical endpoint — overall survival — is confounded by many other factors, such as superimposed illness, disease heterogeneity and prior therapies. Adoption of quantitative models that estimate the effect of a drug on the typical growth rate of a particular tumour over time should provide a more sensitive outcome phenotype for future pharmacogenomic studies28,29,31.

Key cancer endophenotypes

Endophenotypes are the more quantitative, intermediate phenotypes between genetic variants and the clinical phenotypes discussed above. Therefore, using these may lead to pharmacogenomic associations that might be missed with less precise measurements. Endophenotypes such as peripheral blood enzyme function measurements6 and plasma drug concentrations15,32 have been the primary means by which cancer pharmacogenetic markers have been first identified. Additional useful endophenotypes to test for association with germline genetic variants include changes in serum protein concentrations and clinical measures such as blood pressure after treatment33. In vitro endophenotyping (for example, global gene expression and methylation patterns34–36) is another discovery strategy. Several recent studies have used expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) discovered in cell lines to find associations with cancer patient phenotypes37–39. Perhaps most importantly, endophenotyping offers the opportunity to optimize measurement techniques, to discriminate among candidate phenotypes for further investigation and to incorporate knowledge derived from other populations and studies of related endophenotypes.

Statistical analyses

The statistical approaches for detecting associations between germline genetic variation and pharmacogenomic phenotypes are largely the same as those for complex disease susceptibility40–42. Here we highlight some particular considerations for working with data from cancer studies.

Correlated phenotypes

In oncology trials, multiple correlated phenotypes (for example, tumour response, progression-free survival and overall survival) are available for pharmacogenomic analysis. If GWAS analyses are carried out on multiple phenotypes, the temptation to report just the ‘winner’ phenotypes (that is, those with significant P values) without correcting for multiple testing should be avoided43. Methods that combine correlated phenotypes in GWASs have shown increased power to detect SNP associations44,45. Thus, combining the multiple phenotypes available may lead to additional associations that were not discovered when phenotypes were singly analysed.

Heterogeneity and meta-analysis

Sources of heterogeneity specific to cancer pharmacogenomics may include the drug dose administered, drug combination received, cancer type and cancer stage (which is a categorization of the extent of disease). For cancer drugs, it is important to incorporate potential treatment heterogeneity into analyses. For instance, when tamoxifen is given as monotherapy, a significant association between germline CYP2D6 genotype and disease outcome has been shown in multiple studies (especially those not using tumour DNA)10,16,17,46. However, in studies in which tamoxifen was given as a part of a combination chemotherapy regimen, most failed to replicate the CYP2D6 association16,47,48, demonstrating that concomitant medications can confound pharmacogenomic relationships. Conflicting results in the CYP2D6–tamoxifen studies can occur for additional reasons, which have not been as thoroughly examined, including statistical power, dosage and duration of tamoxifen administration and classification of the CYP2D6 genotype groups16.

Efforts among consortia to reduce heterogeneity between studies from the beginning would allow more cancer pharmacogenomics studies to be combined in meta-analyses. As in any meta-analysis, consistent phenotyping allows effect sizes to be combined in either fixed effects models or random effects models, which are statistically more powerful than methods that combine P values or Z scores40. In addition to these classic frequentist approaches, Bayesian models for meta-analysis may be particularly useful in cancer pharmacogenomics because they allow sequential incorporation of new data as it becomes available, perhaps even before a clinical trial ends49. Previous analyses form the prior belief and estimates of association are updated with each new data set to generate a posterior belief43,50,51. This approach has been used to identify risk markers for prostate cancer and colorectal cancer52,53.

The incorporation of cancer-specific and other potential covariates in cancer pharmacogenomic studies is discussed in BOX 2. If GWASs are combined in a metaanalysis and if some studies contain certain covariates, whereas others do not, the results must be interpreted carefully. The top SNPs from such a meta-analysis are most likely to be those with associations that are largely independent of the covariates41. Another source of heterogeneity among studies in a meta-analysis may be population differences; SNPs that are associated with a phenotype in all populations are prioritized over those associated in only one of the populations. Random effects models handle the possibility of heterogeneity among studies better than fixed effects models: the trade-off is that the standard errors are larger41. Tests of heterogeneity can assist researchers in deciding which model to choose41,43,54.

Box 2. Covariates in cancer pharmacogenomics.

As in any genome-wide association study (GWAS), important covariates to consider in cancer pharmacogenomics studies include age, sex and genetic ancestry, which is often estimated by principal components analysis118. In addition, several potential confounders specific to cancer drug studies should be collected when possible and tested for association with phenotypes of interest. If an association with phenotype is detected, then the variable should be included as a covariate in the regression models testing for SNP associations. Covariates to consider for inclusion in cancer pharmacogenomics studies are listed.

| Covariate | Variable type |

|---|---|

| Treatment arm or regimen | Discrete |

| Cancer subtype | Discrete |

| Cancer stage | Discrete |

| Cumulative drug dose | Continuous |

| Somatic mutations | Discrete (present or absent) |

| Additional medications | Discrete or continuous (if dose information) |

| Body surface area | Continuous |

| Age | Continuous |

| Sex | Discrete |

| Ancestry | Continuous (principal components) |

An alternative approach is to incorporate the cumulative dose of a drug each patient has received into a phenotype of interest. This approach is similar to survival analysis, and this accounts for censoring in the data. Although survival analysis models ‘time to event’, this approach models ‘dose to event’. The event could be an adverse event, tumour progression or death. Dose-to-event analysis has been successfully used to identify genetic variants associated with paclitaxel-induced sensory peripheral neuropathy22 (TABLE 2). In this example, the phenotype tested was the cumulative dose of paclitaxel that either triggered the first grade 2 or greater sensory peripheral neuropathy episode or the total dose of paclitaxel that the patient received if no neuropathy was experienced22. Patients without neuropathy are effectively ‘right-censored’ at the cumulative dose level because the dose that would cause neuropathy in these patients is greater than (that is, ‘to the right of’) the dose received.

Replication and validation

After putative associations have been discovered in genome-wide or candidate studies, follow-up studies in patients can test the variants of interest in an attempt to replicate the initial findings. The effect sizes and allele frequencies from the discovery study can be used to estimate the appropriately powered sample size for the replication study. Importantly, the effect sizes are often overestimated in discovery GWASs owing to the winner’s curse phenomenon55–57. The inadequate sample sizes that are often used in cancer pharmacogenomics contribute to upwardly biased effect sizes with large standard errors, especially among SNPs with low minor allele frequencies56. Thus, most putatively positive genetic associations are probably false positives, and replication is crucial58,59. Methods that account for such biased estimates when designing replication studies have been developed55,57.

Replication attempts for cancer pharmacogenomics are often hindered by the lack of an appropriate patient replication cohort. An example is an association (found in a GWAS) between a functional nonsynonymous variant in interleukin 17F (IL17F) and survival in pancreatic cancer. This has not yet been replicated owing to the lack of an existing trial with the same eligibility criteria and drug treatment as the discovery study (which used gemcitabine with or without bevacizumab)14 (TABLE 2). Although the perfect replication trial may never exist, unreplicated associations from pharmacogenomic GWASs should be reported in the literature so that groups with related patient data can test for replication. For instance, the finding of an association of a SNP with methotrexate clearance15 has now been replicated in an additional ALL patient cohort by an independent group of investigators60 (TABLE 2).

Although testing for replication in independent patient cohorts is ideal, if such a cohort is unavailable, follow-up functional studies in model systems can be carried out to strengthen confidence in the initial findings. For example, in the case of the top SNP associated with musculoskeletal toxicity in patients with breast cancer who are receiving aromatase inhibitors, the risk allele was predicted to create an oestrogen response element at the T cell leukaemia/lymphoma 1A (TCL1A) locus13 (TABLE 2). Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments in lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) of known genotype transfected with oestrogen receptor-α (ERα) confirmed that ERα could bind to the risk allele sequence but not to the major allele13. An additional follow-up study showed that oestrogen-induced, SNP-dependent TCL1A expression altered the expression of multiple cytokines and nuclear factor κB (NFκB) in LCLs and an osteosarcoma cell line, providing further evidence for the involvement of TCL1A in aromatase-inhibitor-induced musculoskeletal pain61. Positive functional studies such as these might encourage the collection of replication cohorts in the future.

Alternatives to clinical GWASs

Even without a large enough patient cohort to attempt a GWAS, pairing patient germline variant association data with extensive functional work may implicate genes in drug responses. For example, a recent study used whole-genome structural variant data from just five chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) patients to identify a common deletion in BCL2-like 11 (BCL2L11; also known as BIM) in the three of these patients who were resistant to tyrosine kinase inhibitors62 (TABLE 2). The deletion altered splicing, resulting in BIM isoforms lacking a pro-apoptotic domain. Extensive functional studies in CML and lung cancer cell lines showed that the polymorphism was sufficient to confer resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors by decreased activation of apoptosis. After demonstrating this functional mechanism for the deletion, the authors showed that patients with CML or lung cancer who carry the germline deletion experienced significantly inferior responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitors62 (TABLE 2).

Cell lines

In addition to their use in functionally validating findings from GWASs and sequencing studies in patients, cell line models can be used in discovery studies to generate hypotheses that can eventually be tested in patients. A major limitation of all cell line models is that most drug-induced effects involve the interaction of different cell types and organs; thus, a single model system cannot represent the complexity of drug effects in the human body. However, the advantages of cell line models are numerous, including the ease of experimental manipulation and a lack of the in vivo confounders present in clinical samples.

The availability of extensive genotype data for many panels of LCLs derived from individuals of diverse ancestry, including those from the HapMap63,64 and 1000 Genomes65 projects, facilitates the study of genetic variants predicting drug susceptibility. Most often in such studies, LCLs are treated with increasing concentrations of a drug, and individual cellular sensitivity to the drug is measured by cell growth inhibition or apoptosis assays followed by GWASs that often incorporate genome-wide gene expression35,66,67.

For example, a cytotoxicity-associated SNP discovered in carboplatin-treated LCLs is also associated with progression-free survival and overall survival in 377 ovarian cancer patients treated with carboplatin and paclitaxel37. Several additional discovery associations made in LCLs have been replicated in patient cohorts38,39,68,69. Because a subset of SNPs from the initial LCL GWAS analyses are tested in patients in these types of studies, the multiple testing penalty is not as severe, and a smaller clinical sample size can be used. However, it is unclear how effect sizes translate between LCL and patient cohorts, especially because the phenotypes measured in each usually differ.

To investigate further the relevance of a SNP in tumour response to a drug, functional studies are often carried out in cancer cell lines from the appropriate tumour type for the drug of interest67,70. For instance, follow-up functional experiments using RNAi in a lung cancer cell line were used to test the top hits from a genome-wide analysis in LCLs and confirmed the involvement of two genes in response to pemetrexed71. In another recent study, a systems-biology approach was used to compare the cell growth inhibition caused by 77 therapeutic compounds across 50 breast cancer cell lines of various subtypes72. Using integrative analysis of gene expression and copy number data, the authors showed that some of the observed breast cancer subtypeassociated responses can be explained by specific gene pathway activities; these findings may lead to additional drug targets72.

Resequencing to detect rare variants

GWASs have successfully identified common risk variants for many complex diseases, and such methods have begun to be applied to cancer drug clinical trial data sets13,14,22. As has been proposed for complex disease susceptibility73–75, cancer pharmacogenomic traits are likely to have multiple common and rare variants that, when combined, predict response to therapy.

In a follow-up study to the previously discussed methotrexate clearance GWAS15, deep resequencing of the SLCO1B1 locus in 699 paediatric ALL patients was carried out76 (TABLE 2). SLCO1B1 variants accounted for 10.7% of the population variability in clearance. Rare nonsynonymous variants comprised 17.8% of the SLCO1B1 variation and had larger effect sizes than did the common nonsynonymous variants76. Such studies have much less power to detect the effects of rare alleles than common alleles do; thus, when rare variant associations are found, the effect sizes are probably larger than those of common variants. These results support the hypothesis that a combination of common and rare variants is likely to be important for pharmacogenomic phenotypes.

Next-generation sequencing methods have made the discovery of rare genetic variants throughout the genome fast and affordable. Because sample sizes in cancer pharmacogenomics are often in the hundreds rather than thousands, methods for combining multiple rare variants (minor allele frequency <0.01) within a gene or region into a single association test will be needed, and several have been proposed77–79. One method of testing for gene-level associations in discovery studies assumes that genes with a preponderance of low-frequency alleles in individuals with extreme phenotypes are more likely to modulate that phenotype79. This method was applied to a warfarin-dosing GWAS data set of 181 patients and identified both vitamin K epoxide reductase complex, subunit 1 (VKORC1) and cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily C, polypeptide 9 (CYP2C9), whereas the original GWAS identified only VKORC1 (REFS 79,80). Both genes were implicated in warfarin dosing in a follow-up traditional GWAS of 1,053 patients81. Thus, allele aggregation methods may implicate genes in cancer pharmacogenomic data sets that were not found in traditional GWASs, even without increasing sample size. Of course, the alleles cannot be so rare that they are not detected in the patient cohort.

In terms of cancer pharmacogenomics, these rare variant methods are likely to be tested in cell line models first, as genome sequencing through the 1000 Genomes Project has been carried out for many LCLs for which chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity data are available65,82. A recent exploratory study sequenced 202 drug target genes in 14,002 individuals and found that rare variants (with a minor allele frequency <0.5%) are abundant (with a frequency of 1 every 17 bases)75. The cohort included individuals from case–control studies of 12 different complex diseases. Many of these rare variants are predicted to be deleterious (~56% of the nonsynonymous variants) and are likely to be relevant to understanding pharmacogenomic variation. As costs continue to decrease, patients in clinical trials will probably undergo whole-genome (or exome) sequencing rather than genotyping on SNP arrays. It has recently been shown that extremely low-coverage sequencing (0.1–0.5×) combined with imputation captures almost as much of the common variation (>5%) and low-frequency variation (1–5%) across the genome as SNP arrays at a reduced cost83, and so this approach might be used for future GWASs.

Under the extreme phenotype hypothesis, one approach to reduce the amount of sequencing required is to sequence only individuals in the upper and lower tails of a phenotypic distribution84–86. For example, the therapeutic dose of a particular drug may vary tenfold between the 5% of patients that are most sensitive and the 5% of patients that are most resistant: both of these sets of patients may be enriched for the genetic variants that contribute to differences in drug sensitivity87. Exome sequencing of extreme phenotypes in 91 patients was recently successful in the discovery of a gene involved in chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis, demonstrating the potential use of the approach88. Reducing phenotypic variance by taking as many measurements as possible under such an approach is crucial for ensuring that the individuals sequenced are truly those with the extreme phenotypes.

Conclusions and future directions

Successful GWASs of cancer pharmacogenomic phenotypes are possible (TABLE 2), but replication of germline variant associations has been difficult, often because of challenges associated with large, clinical trials and a lack of well-defined replication populations in oncology. Germline DNA collection and consent for genetic studies from as many participants in future cancer drug clinical trials as possible will allow genome-wide pharmacogenomic association studies of cohorts with standardized dosing and phenotype collection. Another approach that can be considered is pathway-based analysis (BOX 3); like methods that combine rare variants within a gene into a single association test, variants within a pathway can also be combined. Pathway-based approaches provide a more powerful analysis of GWAS data sets41,89 than do analyses of single variants or genes. Such approaches may be particularly useful for pharmacogenomic analysis of oncology clinical trials, which are often underpowered to uncover variants with small effect sizes.

Box 3. Pathway-based association approaches in cancer pharmacogenomics.

Pathway-based association analysis combines variants in genes in a known molecular pathway to test whether the pathway is associated with the phenotype. Genes do not work in isolation; instead, complex molecular networks and pathways are often involved in biological processes. Thus, it is feasible that variation in different genes from the same pathway may lead to similar phenotypic outcomes. The pathway-based approach is useful because an implicated pathway is readily biologically interpretable. For example, the interleukin 12 (IL-12)–IL-23 cytokine pathway has been found to associate with susceptibility to the autoimmune disorder Crohn’s disease in multiple populations119, and this is plausible given the role of cytokines in immune responses. It may not be possible to uncover variants conferring modest phenotypic risk in multiple underpowered genome-wide association studies (GWASs), but these variants can sometimes be readily identified by a pathway-based approach in a single study119. Therefore, such approaches may be particularly useful in cancer pharmacogenomics. Importantly, as the most associated gene in a pathway might not be the best candidate for therapeutic intervention, knowledge of potential targets within a pathway may have clinical implications for finding new drugs that either decrease toxicity or increase tumour response.

Multiple statistical methods have been developed to combine variants within a pathway into an association test and have been reviewed elsewhere41,89. Key considerations are which pathways to test and how to assign variants to genes. Genome-wide approaches often define pathways according to the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)120 and the Gene Ontology121. Variants can be assigned to genes on the basis of either a predefined base pair distance or putative variant function (for example, amino acid change or regulatory activity). Candidate pathway approaches may also be useful in cancer pharmacogenomics. The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB)122 manually curates pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic pathways for well-studied drugs, including many anticancer agents. The pathway for a particular drug could be used to determine whether variation in included genes associates with the variation in response to that drug. Additionally, in the case of a lesser-studied drug, multiple PharmGKB pathways could be tested to determine whether any known pathways also associate with phenotypes induced by the lesser-studied drug. Such an analysis could reveal related mechanisms of action between drugs.

Cancer pharmacogenomic studies have demonstrated the potential to make therapy safer and more effective for patients. Although most current recommendations are for somatic variants (BOX 1), the FDA has included information in the labels of at least seven cancer drugs for which germline variants predict toxicity90. Because of phenotypic heterogeneity (for example, some heterozygotes for reduced TPMT activity tolerate full mercaptopurine doses, but others do not), the FDA will often recommend rather than require a particular pharmacogenetic test (for example, see these FDA summary minutes). The Pharmacogenomics Research Network routinely publishes gene-based drug-dosing guidelines for well-established associations, such as TPMT and mercaptopurine, through the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC)7,91. For these guidelines to improve patient care, full clinical implementation will require widespread physician education, acceptance and automated decision support.

As studies move beyond known drug targets and drug metabolism enzymes, the common variants associated with cancer pharmacogenomic traits may have smaller effect sizes so that they are able to predict a response only when combined. Until discoveries are made and validated to high confidence, clinical utility cannot be assessed. Recently, two polygenic modelling methods have been developed to detect the contribution of larger numbers of common SNPs to complex phenotypes in GWAS data: polygenic risk score analysis92 and mixed linear modelling93,94. In polygenic risk score analysis, an additive polygenic risk score based on SNPs below a predetermined P value threshold in a discovery set of samples is then tested in an independent set of samples. The mixed linear modelling method estimates additive genetic variance under a mixed linear model with a random effect representing the polygenic component of trait variation. Applying similar models to the analysis of cancer pharmacogenomics may implicate new biological factors that influence such traits and inform the types of genetic variants that should be examined in future studies.

Clinical translation will be more challenging when results move beyond individual genes of strong effect and into such polygenic models. However, advances in sequencing technologies, statistical genetics analysis methods and clinical trial designs have shown promise for additional cancer pharmacogenomic discovery. In the future, every patient’s catalogue of drug-related germline variants may be readily available, and algorithms that combine well-validated genetic variants of small effect to explain a large proportion of the variance in treatment toxicity or response could be applied to a patient’s data to provide clinicians with immediate treatment recommendations95. Until then, with the goal of reducing toxicity and improving patient outcomes in mind, the next wave of cancer pharmacogenomic discovery will inform researchers about the underlying genetic architecture of variable drug response and may potentially reveal genes and pathways that can be used as targets for new drugs.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the following US National Institutes of Health grants: U01GM61393, R01CA136765, K23CA124802, T32CA009594 and F32CA165823. In addition, M.J.R. is a recipient of a Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO Translational Research Professorship, In Memory of Merrill J. Egorin, MD. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the American Society of Clinical Oncology or the Conquer Cancer Foundation.

Glossary

- Efficacy

In oncology, this term refers to measures such as tumour response, progression-free survival and overall survival

- Pharmacokinetics

The effect of the body on the drug: that is, the process by which a drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized and eliminated by the body

- Pharmacodynamics

The effect of the drug on the body: that is, drug targets and mechanisms of action

- Nested case–control design

A case–control study in which only a subset of controls is compared to the cases by matching controls to the cases on known covariates that associate with the phenotype of interest. It increases efficiency and may reduce genotyping costs

- Adverse events

Toxicities or side effects attributed to the use of a particular drug

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE)

Organizes adverse events by body system and rates each specific event according to a 1–5 scale: 1, mild but not warranting intervention: 2, moderate with medical intervention or temporary cessation of treatment warranted: 3, severe requiring intensive medical intervention or hospitalization: 4, life-threatening: and 5, death

- Tumour response

How a tumour changes or does not change in size after a particular treatment regimen

- Fixed effects models

A type of meta-analysis that combines the effect sizes (estimates) across studies that each have the same phenotype measured on the same scale and assumes the genetic effects are the same across the different studies

- Random effects models

A type of meta-analysis that combines the effect sizes (estimates) across studies with the same phenotypic measurement, allows the genetic effects to be different across the different studies and provides a measure of heterogeneity across the studies

- Z scores

A statistical measure that quantifies the number of standard deviations that an observed data point is from the expected value under no association

- Bayesian models

A statistical framework that incorporates uncertainty in prior beliefs about parameters such as between-study variance, effect size and genetic model (that is, additive and dominant) into association testing

- Winner’s curse phenomenon

Refers to the overestimation of the effect size of a newly identified genetic association because many genome-wide association studies are underpowered for detecting small genetic effects at a stringent genome-wide significance level. It implies that the sample size required for a confirmatory study will be underestimated, resulting in failure to replicate the association

- Censoring

A type of missing data problem that occurs when the value of a measurement is only partially known (for example, in survival analysis, it might be known only that the date of death is sometime after the date of last patient contact)

- Extreme phenotype hypothesis

The assumption that individuals with the most severe drug response phenotypes are more likely to carry alleles that associate with the phenotypes

Footnotes

FURTHER INFORMATION

1000 Genomes Project: http://www.1000genomes.org

ClinicalTrials.gov: http://clinicaltrials.gov

CPIC: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation

Consortium: http://www.pharmgkb.org/page/cpic

Gene Ontology: http://www.geneontology.org

Genomics > Table of Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Labels: http://www.fda.gov/drugs/scienceresearch/researchareas/pharmacogenetics/ucm083378.htm

HapMap Homepage: http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Imaging Response Criteria — Cancer Imaging Program: http://imaging.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials/imaging

KEGG PATHWAY database: http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html

Nature Reviews Genetics Series on Study designs: http://www.nature.com/nrg/series/studydesigns/index.html

Nature Reviews Genetics Series on Translational genetics: http://www.nature.com/nrg/series/translational/index.html

Pharmacogenomics of Anticancer Agents Research Group: http://paarpharmacogenomics.org

The Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase (PharmGKB): http://www.pharmgkb.org

Protocol Development (Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events): http://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm

Summary Minutes of the Pediatric Oncology Subcommittee of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee July 15, 2003: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/03/minutes/3971m1.doc

ALL LINKS ARE ACTIVE IN THE ONLINE PDF

Competing interests statement

The authors declare competing financial interests: see Web version for details.

References

- 1.Peters EJ, et al. Pharmacogenomic characterization of US FDA-approved cytotoxic drugs. Pharmacogenomics. 2011;12:1407–1415. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolan ME, et al. Heritability and linkage analysis of sensitivity to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4353–4356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watters JW, Kraja A, Meucci MA, Province MA, McLeod HL. Genome-wide discovery of loci influencing chemotherapy cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11809–11814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404580101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paugh SW, et al. Cancer pharmacogenomics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;90:461–466. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Relling MV, et al. Mercaptopurine therapy intolerance and heterozygosity at the thiopurine S-methyltransferase gene locus. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:2001–2008. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.23.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinshilboum RM, Sladek SL. Mercaptopurine pharmacogenetics: monogenic inheritance of erythrocyte thiopurine methyltransferase activity. Am J Hum Genet. 1980;32:651–662. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Relling MV, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium guidelines for thiopurine methyltransferase genotype and thiopurine dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:387–391. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stocco G, et al. Genetic polymorphism of inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase is a determinant of mercaptopurine metabolism and toxicity during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85:164–172. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Innocenti F, et al. Genetic variants in the UDPglucuronosyltransferase 1A1 gene predict the risk of severe neutropenia of irinotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1382–1388. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroth W, et al. Breast cancer treatment outcome with adjuvant tamoxifen relative to patient CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotypes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5187–5193. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deeken J. The Affymetrix DMET platform and pharmacogenetics in drug development. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2009;11:260–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grady BJ, Ritchie MD. Statistical optimization of pharmacogenomics association studies: key considerations from study design to analysis. Curr Pharmacogenom Person Med. 2011;9:41–66. doi: 10.2174/187569211794728805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ingle JN, et al. Genome-wide associations and functional genomic studies of musculoskeletal adverse events in women receiving aromatase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4674–4682. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.5064. This cancer pharmacogenomics GWAS of toxicity in a clinical trial demonstrates how cell models can functionally validate patient findings. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Innocenti F, et al. A genome-wide association study of overall survival in pancreatic cancer patients treated with gemcitabine in CALGB 80303. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:577–584. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1387. This GWAS demonstrates a potential prognostic rather than drug effect, an important distinction to make in cancer studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trevino LR, et al. Germline genetic variation in an organic anion transporter polypeptide associated with methotrexate pharmacokinetics and clinical effects. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5972–5978. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.4156. This successful cancer pharmacogenomics GWAS highlights the use of drug clearance as an endophenotype. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiyotani K, et al. Lessons for pharmacogenomics studies: association study between CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response. Pharmacogenet Genom. 2010;20:565–568. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32833af231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schroth W, et al. Association between CYP2D6 polymorphisms and outcomes among women with early stage breast cancer treated with tamoxifen. JAMA. 2009;302:1429–1436. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Regan MM, et al. CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer: The Breast International Group 1–98 Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:441–451. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamura Y, et al. Re: CYP2D6 genotype and tamoxifen response in postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive breast cancer: The Breast International Group 1–98 Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1264. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klopfleisch R, Weiss AT, Gruber AD. Excavation of a buried treasure—DNA, mRNA, miRNA and protein analysis in formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissues. Histol Histopathol. 2011;26:797–810. doi: 10.14670/HH-26.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spencer CC, Su Z, Donnelly P, Marchini J. Designing genome-wide association studies: sample size, power, imputation, and the choice of genotyping chip. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000477. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin RM, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel loci for paclitaxel-induced sensory peripheral neuropathy in CALGB 40101. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:5099–5109. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1590. This cancer pharmacogenomics GWAS demonstrates the use of dose to toxicity event as a phenotype. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daly AK. Genome-wide association studies in pharmacogenomics. Nature Rev Genet. 2010;11:241–246. doi: 10.1038/nrg2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Link E, et al. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:789–799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilke RA, et al. The Clinical Pharmacogenomics Implementation Consortium: CPIC guideline for SLCO1B1 and simvastatin-induced myopathy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:112–117. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang HQ, Brady MF, Cella D, Fleming G. Validation and reduction of FACT/GOG-Ntx subscale for platinum/paclitaxel-induced neurologic symptoms: a gynecologic oncology group study. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2007;17:387–393. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.00794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenhauer EA, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karrison TG, Maitland ML, Stadler WM, Ratain MJ. Design of Phase II cancer trials using a continuous endpoint of change in tumor size: application to a study of sorafenib and erlotinib in non small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1455–1461. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maitland ML, Bies RR, Barrett JS. A time to keep and a time to cast away categories of tumor response. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3109–3111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma MR, et al. Resampling Phase III data to assess. Phase II trial designs and endpoints. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:2309–2315. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Claret L, et al. Model-based prediction of Phase III overall survival in colorectal cancer on the basis of phase II tumor dynamics. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4103–4108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.0807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iyer L, et al. UGT1A1*28 polymorphism as a determinant of irinotecan disposition and toxicity. Pharmacogenom J. 2002;2:43–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eechoute K, et al. Polymorphisms in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) predict sunitinib-induced hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:503–510. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gamazon ER, Huang RS, Cox NJ, Dolan ME. Chemotherapeutic drug susceptibility associated SNPs are enriched in expression quantitative trait loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9287–9292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001827107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wheeler HE, Dolan ME. Lymphoblastoid cell lines in pharmacogenomic discovery and clinical translation. Pharmacogenomics. 2012;13:55–70. doi: 10.2217/pgs.11.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W, Huang RS, Dolan ME. Integrating epigenomics into pharmacogenomic studies. Pharmgenom Pers Med. 2008;2008:7–14. doi: 10.2147/pgpm.s4341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang RS, et al. Platinum sensitivity-related germline polymorphism discovered via a cell-based approach and analysis of its association with outcome in ovarian cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5490–5500. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan XL, et al. Genetic variation predicting cisplatin cytotoxicity associated with overall survival in lung cancer patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5801–5811. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ziliak D, et al. Germline polymorphisms discovered via a cell-based, genome-wide approach predict platinum response in head and neck cancers. Transl Res. 2011;157:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Begum F, Ghosh D, Tseng GC, Feingold E. Comprehensive literature review and statistical considerations for GWAS meta-analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:3777–3784. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cantor RM, Lange K, Sinsheimer JS. Prioritizing GWAS results: a review of statistical methods and recommendations for their application. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:6–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manolio TA. Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:166–176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zeggini E, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis in genome-wide association studies. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:191–201. doi: 10.2217/14622416.10.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim S, Xing EP. Statistical estimation of correlated genome associations to a quantitative trait network. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Korte A, et al. A mixed-model approach for genomewide association studies of correlated traits in structured populations. Nature Genet. 2012;44:1066–1071. doi: 10.1038/ng.2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goetz MP, et al. Evaluation of CYP2D6 and efficacy of tamoxifen and raloxifene in women treated for breast cancer chemoprevention: results from the NSABP P1 and P2 clinical trials. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:6944–6951. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nowell SA, et al. Association of genetic variation in tamoxifen-metabolizing enzymes with overall survival and recurrence of disease in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;91:249–258. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-7751-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okishiro M, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of CYP2D6 10 and CYP2C19 2, 3 are not associated with prognosis, endometrial thickness, or bone mineral density in Japanese breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant tamoxifen. Cancer. 2009;115:952–961. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berry DA. Bayesian clinical trials. Nature Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:27–36. doi: 10.1038/nrd1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salanti G, Higgins JP, Trikalinos TA, Ioannidis JP. Bayesian meta-analysis and meta-regression for gene-disease associations and deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Stat Med. 2007;26:553–567. doi: 10.1002/sim.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stephens M, Balding DJ. Bayesian statistical methods for genetic association studies. Nature Rev Genet. 2009;10:681–690. doi: 10.1038/nrg2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Newcombe PJ, et al. A comparison of Bayesian and frequentist approaches to incorporating external information for the prediction of prostate cancer risk. Genet Epidemiol. 2012;36:71–83. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fridley BL, et al. Bayesian mixture models for the incorporation of prior knowledge to inform genetic association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:418–426. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in metaanalyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Faye LL, Bull SB. Two-stage study designs combining genome-wide association studies, tag single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and exome sequencing: accuracy of genetic effect estimates. BMC Proceedings. 2011;5 (Suppl 9):S64. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-5-S9-S64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Garner C. Upward bias in odds ratio estimates from genome-wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31:288–295. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun L, et al. BR-squared: a practical solution to the winner’s curse in genome-wide scans. Hum Genet. 2011;129:545–552. doi: 10.1007/s00439-011-0948-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ioannidis JP. Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology. 2008;19:640–648. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818131e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lopez-Lopez E, et al. Polymorphisms of the SLCO1B1 gene predict methotrexate-related toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:612–619. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu M, et al. Aromatase inhibitors, estrogens and musculoskeletal pain: estrogen-dependent T-cell leukemia 1A (TCL1A) gene-mediated regulation of cytokine expression. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R41. doi: 10.1186/bcr3137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ng KP, et al. A common BIM deletion polymorphism mediates intrinsic resistance and inferior responses to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer. Nature Med. 2012;18:521–528. doi: 10.1038/nm.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Altshuler DM, et al. Integrating common and rare genetic variation in diverse human populations. Nature. 2010;467:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature09298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frazer KA, et al. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861. doi: 10.1038/nature06258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang RS, et al. A genome-wide approach to identify genetic variants that contribute to etoposide-induced cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:9758–9763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703736104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Niu N, et al. Radiation pharmacogenomics: a genome-wide association approach to identify radiation response biomarkers using human lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genome Res. 2010;20:1482–1492. doi: 10.1101/gr.107672.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen SH, et al. A genome-wide approach identifies that the aspartate metabolism pathway contributes to asparaginase sensitivity. Leukemia. 2011;25:66–74. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mitra AK, et al. Impact of genetic variation in FKBP5 on clinical response in pediatric acute myeloid leukemia patients: a pilot study. Leukemia. 2011;25:1354–1356. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li L, et al. Gemcitabine and cytosine arabinoside cytotoxicity: association with lymphoblastoid cell expression. Cancer Res. 2008;68:7050–7058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wen Y, et al. An eQTL-based method identifies CTTN and ZMAT3 as pemetrexed susceptibility markers. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:1470–1480. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heiser LM, et al. Subtype and pathway specific responses to anticancer compounds in breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2724–2729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018854108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gibson G. Rare and common variants: twenty arguments. Nature Rev Genet. 2011;13:135–145. doi: 10.1038/nrg3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Manolio TA, et al. Finding the missing heritability of complex diseases. Nature. 2009;461:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nature08494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nelson MR, et al. An abundance of rare functional variants in 202 drug target genes sequenced in 14,002 people. Science. 2012;337:100–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1217876. This preliminary survey highlights the need for studying rare variants in pharmacogenomics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ramsey LB, et al. Rare versus common variants in pharmacogenetics: SLCO1B1 variation and methotrexate disposition. Genome Res. 2012;22:1–8. doi: 10.1101/gr.129668.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bansal V, Libiger O, Torkamani A, Schork NJ. Statistical analysis strategies for association studies involving rare variants. Nature Rev Genet. 2010;11:773–785. doi: 10.1038/nrg2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu JZ, et al. A versatile gene-based test for genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tatonetti NP, Dudley JT, Sagreiya H, Butte AJ, Altman RB. An integrative method for scoring candidate genes from association studies: application to warfarin dosing. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11 (Suppl 9):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S9-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cooper GM, et al. A genome-wide scan for common genetic variants with a large influence on warfarin maintenance dose. Blood. 2008;112:1022–1027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]